Highlights

-

•

A very rare case of paraganglioma of filum terminale is described.

-

•

Clinical and radiological features of spinal paraganglioma are listed.

-

•

Surgical management of paraganglioma of filum terminale is discussed.

Abbreviations: MRI, Magnetic Resonance Imaging; FrFSE, Fast Relaxation Fast Spin Echo; WHO, World Health Organization

Keywords: Paraganglioma, Filum terminale, Cauda equina, Spinal tumor, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Paragangliomas of filum terminale are rare benign tumors, arising from the adrenal medulla or extra-adrenal paraganglia. These lesions usually present with chronic back pain and radiculopathy and only two cases of acute neurological deficit have been reported in literature.

Presentation of case

A case with an acute paraplegia and cauda equina syndrome due to an hemorrhagic paraganglioma of the filum terminale is described. Magnetic resonance imaging showed an intradural tumor extending from L1 to L2 compressing the cauda equina, with an intralesional and intradural bleed. An emergent laminectomy with total removal of the tumor was performed allowing a post-operative partial sensory recovery. Histopathological examination diagnosed paraganglioma.

Discussion

Paragangliomas are solid, slow growing tumors arising from specialized neural crest cells, mostly occurring in the head and neck and rarely in cauda equina or filum terminale. MRI is gold standard radiological for diagnosis and follow-up of these lesions. They have no pathognomonic radiological and clinical features and are frequently misdiagnosed as other spinal lesions. No significant correlation was observed between the duration of symptoms and tumor dimension. Acute presentation is unusual and emergent surgical treatment is fondamental. The outcome is very good after complete excision and radiotherapical treatment is recommended after an incomplete resection. Conclusion: Early radiological assessment and timely surgery are mandatory to avoid progressive neurological deficits in case of acute clinical manifestation of paraganglioma of filum terminale.

1. Introduction

Paragangliomas of filum terminale are rare benign neuroendocrine tumors, arising from the adrenal medulla or extra-adrenal paraganglia, representing approximately 3% of cauda equina tumors [1]. The mean age of presentation is approximately 40–60 years with a slight male predominance [2]. Clinically and radiologically these lesions can be misdiagnosed as schwannomas or ependymomas and they often present insidiously with chronic back pain and radiculopathy. Reviewing the pertinent literature, only two cases of acute manifestation are described. We describe a case with an acute paraplegia and cauda equina syndrome because of an hemorrhagic paraganglioma of the filum terminale. We analyse the clinical, histopathological and radiological findings of these tumors, and discuss surgical treatment in line with the SCARE criteria [3].

2. Presentation of case

A 56-year-old man with a 10 years history of progressive low back pain and bilateral radicular leg pain without evidence of bowel or bladder incontinence or myelopathy, presented with a 4-day history of the acute-onset of a flaccid paraplegia with urinary retention, accompanied by complete sensory loss below L1. Emergent MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) demonstrated a large intradural well encapsulated tumor extending from L1 to L2 compressing the cauda equine, measured about 4 cm in cranio-caudal diameter, heterogeneously enhancing after gadolinium injection with serpentine flow-voids in the subarachnoid space cranial to the tumor and with FrFSE (Fast Relaxation Fast Spin Echo) MR images showing uniform hyperintensity suggestive of an intralesional and intradural bleed (Figs. 1 and 2a–c ). An emergent D12-L3 laminectomy was performed. Intraoperatively, prior to dural opening, the dural sac was noted to be dark blue in color and tense, because of underlying hematoma. The dura was initially opened above the tumor to prevent downward herniation of the mass, observing the egress of bloody cerebrospinal fluid under pressure and a large, well-encapsulated, dark red in color, mass pushing the dorsal nerve roots out of the dural opening. Caudally extending the midline durotomy, a shape dissection plane, retracting the nerve roots, was carefully performed around the tumor, that originated from the filum terminale, identified by the large, tortuous vein running along its length. After coagulation and cutting of this vein, the tumor was freed from its superior attachment and then removed en bloc (Fig. 2d). Histopathological examination showed paraganglioma, positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin and S-100 protein. By two months from surgery, only partial sensory returned below L2, but the patient still has no perineal sensation and has not regained bowel or bladder function. At one year post-operative MRI showed no evidence of tumor recurrence (Fig. 2e).

Fig 1.

Sagittal (B) T1-weighted (A), T2-weighted FrFSE (B) and T2-weighted FrFSE fat sat (C) magnetic resonance images revealing a large omogeneously hyperintense intradural lesion (yellow arrow) extending from L1 to L2, with enhancement after gadolinium and flow voids cranial to the mass indicative of venous congestion or high vascularity of the tumor.

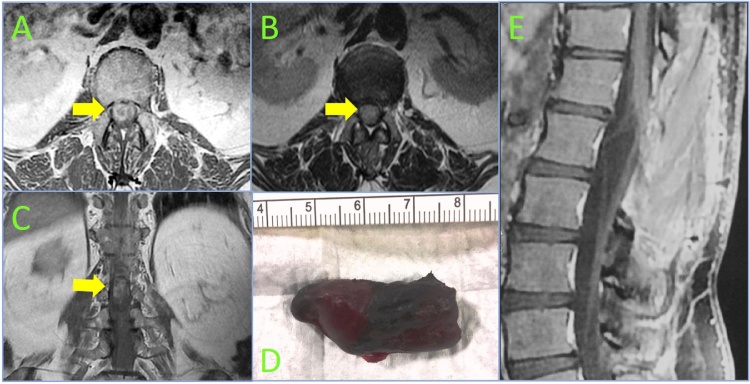

Fig. 2.

Axial T1 (A) and T2-weighted (B) and coronal T1-weighted (C) images showing a large lesion (yellow arrow) taking up the vast majority of the cross-sectional area at L1-L2 level, obscuring the visibility of the cauda equina. Photograph of the hemorrhagic paraganglioma (4 × 2 cm) after excision en bloc (D). One year post-operative, sagittal T1-weighted image after gadolinim (E) demonstring no residual or recurrent contrast enhancing tumor.

3. Discussion

Paragangliomas are solid, well‐encapsulated, highly vascular, slow‐growing neuroendocrine tumors arising from specialized neural crest cells [4]. Paraganglionic cells and the neural crest have a common origin, and during embryogenesis, they migrate along the neural tube. Paragangliomass result from dysfunction of embryonic paraganglia cell migration or non-regression. They can be found in adrenal and extra-adrenal tissues, and the extra-adrenal paragangliomas can be divided into sympathetic and parasympathetic types [1]. The sympathetic paragangliomas are usually secretory and produce catecholamines while parasympathetic paragangliomas tend to be non-secretory [5]. In the central nervous system nearly 80–90% paragangliomas (predominantly parasympathetic) occur in the head and neck and typically arise in the carotid body or the glomus jugularis but other sites may are sella turcica, cavernous sinus, pineal gland, pituitary gland, cerebellopontine angle, and petrous ridge. At level of cauda equina or filum terminale they are very rare accounting for 2.5–3.8% of cases [6]. The first documented description of a paraganglioma in the cauda equina region was performed by Lernan in 1972 [4]. The diffusion in the central nervous system and distant metastases is rare [7]. These lesions are commonly encountered in the fifth and fourth decades of life with male predominance as reported by Gutenberg [2], and they are sporadic neoplasms, but approximately 1% of cases are autosomal dominant [5]. MRI is the gold standard radiological exam for the diagnosis and follow-up of paragangliomas of cauda equina or filum terminale, that may appear isotense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on post-contrast T2-weighted sequences with homogenenous or heterogeneous enhancement [8]. However, these spinal tumors have no pathognomonic features and are frequently misdiagnosed as schwannomas, ependymomas, meningioma, teratoma, and hemangioma [9]. A serpiginous flow void from vessels associated with the upper pole of the tumor and a T2-weighted images revealing a hypointense tumor rim (cap sign) due to presence of hemosiderin, caused by a prior hemorrhage, can be present. Optional spinal angiography can reveal the highly vascularized pedicle [10]. Yang et al. reported intratumoral hemorrhagic cyst fluid [11], Miliaras et al. concluded chronic hemorrhage can occur in these tumours [12], whereas Li et al. reported the first case of spinal paraganglioma exhibiting subarachnoid hemorrhage [13]. Histologically paragangliomas are slow-growing benign tumors (WHO Grade I), comprised of two cell types, chief cells and spindle shaped sustentacular cells, which are classically described as “Zellballen” or nesting pattern. S100 staining is positive in sustentacular cells and can also be positive in tumor cells of ependymomas. Ependymal cells are GFAP positive whereas GFAP staining is negative in neoplastic cells of paragangliomas [1]. Nearly half of paragangliomas of cauda equina contain mature ganglion cells, but origin of this variation remains unclear [14]. The most common symptom is the low back pain with or without radiculopathy (50%), motor or sensory deficits can be present in less than 10% of patients and bowel or bladder incontinence is quite rare (3%) though some authors reported a higher frequency of sphincter and genital disturbance, compared to other tumors of cauda [12], [14]. Paraplegia and sympathetic secretory symptoms related to catecholamine are uncommon [15]. No significant correlation was observed between the duration of symptoms and tumor dimension. In literature, only two cases with an acute flaccid paraparesis/cauda equina syndrome attributed to an intratumoral hemorrhagic paraganglioma, (Table 1) have previously documented [15], [16]. Because the relatively benign natural history, observation can be a reasonable option in asymptomatic cases. Jansen et al. estimated the growth rate of head and neck paragangliomas with doubling time of >10 years with an average of 4.2 years [17]. Intra-operatively paraganglioma are most often located in the intradural-extramedullary compartment and they appear well encapsulated. purple, friable and hemorrhagic. The outcome is excellent after complete excision of the mass and the main technical problem is dense adhesion to nerve roots [18]. In the case of a total removal, however some authors recommend a long-term follow-up due to a possibility of recurrence, which is rare about 1–4% [7], [11]. With subtotal resection, 10% paraganglioma of cauda equina recurred within one year following surgery, though Landi et al. reported a relapse 30 years after incomplete resection [19]. Radiotherapy is recommended after a subtotal resection [20].

Table 1.

Review of acute onset of paraganglioma of filum terminale/cauda equina.

| Author | Age (years) | Sex | Symptoms | Location | Surgery (Emergent) | Post-operative outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nagarjun et al. [15] | 36 | F | Paraplegia, Cauda equina Syndrome |

T12-L2 | GTR | Partial motor-sensitive recovery, partial bladder incontinence |

| Ma et al. [16] | 51 | M | Paraparesis, Cauda equina Syndrome |

L1-L5 | GTR | Partial motor-sensitive recovery |

| Present case | 56 | M | Paraplegia, Cauda equina Syndrome |

L1-L2 | GTR | Partial sensory recovery |

Legend: GTR: Gross Total Resection.

4. Conclusion

Paragangliomas of the filum terminale are solid, well‐encapsulated, highly vascular, rare benign lesions, which very infrequently present with acute manifestations. We report a case of acute flaccid paraplegia and cauda equine syndrome from an hemorrhagic paraganglioma, treated via emergent surgery with partial neurological recovery. Due to the lack of pathognomonic radiological findings, histopathological examination is the gold standard for diagnosis of these lesions. In case of acute presentation early recognition and timely surgical treatment are mandatory to avoid progressive neurological deficits while adiuvant radiotherapical treatment is important if an incomplete resection is performed.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest.

Funding sources

No funding has been used for this research.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval has been applied for this case report study, only the written and oral consent by the patient.

Consent

A written consent has been obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images and is available for review on request.

Author contribution

All the authors has contributed equally to the paper.

Guarantor

Aldo Ierard.

Bruno Romanelli.

Contributor Information

Domenico Murrone, Email: doflamingo82@gmail.com.

Bruno Romanelli, Email: brunoromanelli@alice.it.

Giuseppe Vella, Email: gvrad@libero.it.

Aldo Ierardi, Email: aldo.ierardi@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Dillard-Cannon E., Atsina K.B., Ghobrial G., Gnass E., Curtis M.T., Heller J. Lumbar paraganglioma. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2016;30:149–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutenberg A., Wegner C., Pilgram-Pastor S.M., Gunawan B., Rohde V., Giese A. Paraganglioma of the filum terminale: review and report of the first case analyzed by CGH. Clin. Neuropathol. 2010;29:227–232. doi: 10.5414/npp29227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., Group S. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerman R.I., Kaplan E.S., Daman L. Ganglioneuroma-paraganglioma of the intradural filum terminale. Case report. J. Neurosurg. 1972;36:652–658. doi: 10.3171/jns.1972.36.5.0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masuoka J., Brandner S., Paulus W., Soffer D., Vital A., Chimelli L., Jouvet A., Yonekawa Y., Kleihues P., Ohgaki H. Germline SDHD mutation in paraganglioma of the spinal cord. Oncogene. 2001;20:5084–5086. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wager M., Lapierre F., Blanc J.L., Listrat A., Bataille B. Cauda equina tumors: a French multicenter retrospective review of 231 adult cases and review of the literature. Neurosurg. Rev. 2000;23:119–129. doi: 10.1007/pl00011940. discussion 130–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strommer K.N., Brandner S., Sarioglu A.C., Sure U., Yonekawa Y. Symptomatic cerebellar metastasis and late local recurrence of a cauda equina paraganglioma. Case report. J. Neurosurg. 1995;83:166–169. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.1.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen W.L., Dillon W.P., Kelly W.M., Norman D., Brant-Zawadzki M., Newton T.H. MR imaging of paragangliomas. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1987;148:201–204. doi: 10.2214/ajr.148.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilmani S., Ngamasata T., Karkouri M., Elazahri A. Paraganglioma of the filum terminale mimicking neurinoma: case report. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2016;7:S153–155. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.177892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamourian A.C. MR of superficial siderosis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1993;14:1445–1448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang C., Li G., Fang J., Wu L., Yang T., Deng X., Xu Y. Clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes of primary spinal paragangliomas. J. Neurooncol. 2015;122:539–547. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1742-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miliaras G.C., Kyritsis A.P., Polyzoidis K.S. Cauda equina paraganglioma: a review. J. Neurooncol. 2003;65:177–190. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000003753.27452.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li P., James S.L., Evans N., Davies A.M., Herron B., Sumathi V.P. Paraganglioma of the cauda equina with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Clin. Radiol. 2007;62:277–280. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akbik O.S., Floruta C., Chohan M.O., SantaCruz K.S., Carlson A.P. A unique case of an aggressive gangliocytic paraganglioma of the filum terminale. Case Rep. Surg. 2016;2016:1232594. doi: 10.1155/2016/1232594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagarjun M.N., Savardekar A.R., Kishore K., Rao S., Pruthi N., Rao M.B. Apoplectic presentation of a cauda equina paraganglioma. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2016;7:37. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.180093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma T., Rubin B., Grobelny B., ZagZag D., Koslow M., Mikolaenki I., Wlliott R. Acute paraplegia from hemorrhagic paraganglioma of filum terminale: case report and review of literature. Internet J. Neurosurg. 2012;8 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jansen J.C., van den Berg R., Kuiper A., van der Mey A.G., Zwinderman A.H. Estimation of growth rate in patients with head and neck paragangliomas influences the treatment proposal. Cancer. 2000;88:2811–2816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liccardo G., Pastore F.S., Sherkat S., Signoretti S., Cavazzana A., Fraioli B. Paraganglioma of the cauda equina. Case report with 33-month recurrence free follow-up and review of the literature. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 1999;43:169–173. discussion 173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landi A., Tarantino R., Marotta N., Rocco P., Antonelli M., Salvati M., Delfini R. Paraganglioma of the filum terminale: case report. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2009;7:95. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suarez C., Rodrigo J.P., Mendenhall W.M., Hamoir M., Silver C.E., Gregoire V., Strojan P., Neumann H.P., Obholzer R., Offergeld C. Carotid body paragangliomas: a systematic study on management with surgery and radiotherapy. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:23–34. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]