Abstract

Magnetosomes are nanosized iron oxide particles surrounded by lipid membrane synthesized by magnetotactic bacteria (MTB). Magnetosomes have been exploited for a broad range of biomedical and biotechnological applications. Due to their enormous potential in the biomedical field, its safety assessment is necessary. Detailed research on the toxicity of the magnetosomes was not studied so far. This study focuses on the toxicity assessment of magnetosomes in various models such as Human RBC’s, WBC’s, mouse macrophage cell line (J774), Onion root tip and fish (Oreochromis mossambicus). The toxicity in RBC models revealed that the RBC’s are unaltered up to a concentration of 150 µg/ml, and its morphology was not affected. The genotoxicity studies on WBC’s showed that there were no detectable chromosomal aberrations up to a concentration of 100 µg/ml. Similarly, there were no detectable morphological changes observed on the magnetosome-treated J774 cells, and the viability of the cells was above 90% at all the tested concentrations. Furthermore, the magnetosomes are not toxic to the fish (O. mossambicus), as no mortality or behavioural changes were observed in the magnetosome-treated groups. Histopathological analysis of the same reveals no damage in the muscle and gill sections. Overall, the results suggest that the magnetosomes are safe at lower concentration and does not pose any potential risk to the ecosystem.

Keywords: Magnetosomes, Toxicity, Oreochromis mossambicus, RBC’s, WBC, Mouse macrophage cell line (J774)

Introduction

Chemically synthesized nanomaterials possess special properties such as high surface area, higher mechanical, electrical and imaging properties (Colvin 2003). Due to these characteristics, they are being used for various applications. Certain metal particles such as zinc, cadmium, cobalt, nickel, and silver are reported to be toxic and not recommended to use for biomedical applications, whereas iron oxide and titanium are less toxic to cells (Berry and Curtis 2003; Hofmann et al. 2010). Among various nanoparticles, iron oxide particles such as magnetite and haematite gained much importance due to their superparamagnetic property (Huber 2005). The applications of magnetic nanoparticles include magnetic resonance imaging, hyperthermia, drug delivery, macromolecular labelling and removal of heavy metals, etc. (Pankhurst et al. 2003; Salata 2004; Huang and Hu 2008; Zhang et al. 2010; Grover et al. 2012). Although the magnetic nanoparticles are considered to be safer compared to other particles, reports say that they can be adsorbed, translocated, accumulate and exhibit toxicity in plant tissues and aquatic animals (Zhu et al. 2008; Nations et al. 2011). The toxicity of magnetic particles depends on several factors such as structure, dosage, chemical composition and modification (Noori et al. 2011; Khadka et al. 2014).

Magnetosomes are the unique membrane-bound magnetic iron-bearing inorganic crystals synthesized by magnetotactic bacteria (MTB). It consists of either magnetite or greigite crystals enveloped by a lipid bilayer membrane derived from cytoplasmic membrane. The magnetosome membrane consists of phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylglycerol as the major lipids (Bazylinski and Frankel 2004) and numerous other proteins (Grünberg et al. 2004). The size of magnetosomes varies from 35 to 120 nm; possessing superparamagnetic nature and the synthesis is completely under genetic control (Ullrich et al. 2005). In contrast, the chemically synthesized magnetic nanoparticles are not biocompatible and need to be coated with polymer/lipids to use in biomedical applications (Ruys and Mai 1999). Since magnetosomes are synthesized with a lipid membrane, they are recognized to be more biocompatible and less toxic (Tartaj et al. 2003). Magnetosomes have been reported for their numerous applications, but the toxicity evaluations of magnetosomes have not been studied in detail so far. This prompted us to carry out the genotoxicity, cytotoxicity and phytotoxicity of magnetosomes in different models such as Human RBC’s, WBC’s, mouse macrophage cell line (J774), Onion root tip and in Fish (Oreochromis mossambicus).

Materials and methods

Magnetotactic bacteria and cultivation

Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense (MSR1) strain was purchased from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ), Germany. Hungate anaerobic technique was used as a standard procedure for bacterial culturing and maintenance (Hungate 1969). MSR-1 was cultured microaerobically in standard Magnetospirillum growth medium (MSGM) as described by Blakemore et al. (1979). After dispensing 300 ml volume of medium in 500-ml serum bottles, sterile nitrogen was flushed to remove the dissolved oxygen. The culture bottles were sealed with butyl rubber stoppers and sterilized by autoclaving. The medium flasks were inoculated with 10% (v/v) cells growing in exponential phase from the inoculum. The magnetic moment of the culture was manually analysed by placing the culture bottles on a magnetic stirrer and observing the scattering of light.

Magnetosome extraction and characterization

Magnetosomes were extracted as reported earlier by Alphandéry et al. (2012) with minor modifications. After 48 h of incubation in MSGM media, the MTB cells were separated from the culture medium by centrifugation at 4000×g for 20 min. The pellet was re-suspended in deionised water and centrifuged again at 4000×g for 20 min and re-suspended in Tris HCl buffer (pH 7.0). Then the suspension was sonicated at 30 W for 2 h to lyse the cells. The magnetosomes mixture was further purified by suspending in 1% SDS solution at 90 °C for 5 h. Magnetosomes and residual contaminants were separated by placing the south pole of a bar magnet adjacent to the tubes. The extracted magnetosomes were freeze dried (Lark, Penguin Classic Plus, India) and stored for further use.

Bacterial magnetosomes were characterized by various analytical techniques. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, ZEISS EV018, Germany) operating at 10 kV and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM, JEOL JEM2100, Japan) operating at 200 kV was used for the size and morphology. For electron microscopy, aqueous suspension of magnetosome was dropped onto sample holder and placed in vacuum oven for 2 h to dry. Dried samples were loaded, and micrographs were taken. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of magnetosome were measured between 400 and 4000/cm using (Shimadzu, Japan). The morphology and size of the magnetosomes were analysed in AFM (Nanosurf Easy Scan 2, SPM Electronics, Liestal, Switzerland). For AFM imaging, magnetosomes were dispersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4 and spotted onto OTS-coated slides, incubated for 5 min, washed with PBS and then imaged (Oestreicher et al. 2012). Phase composition of the powdered magnetosomes was determined by X-ray diffraction method using Bruker D8 Advance (Bruker AXS, Germany). The freeze dried magnetosomes under Cu Ka radiation, 25 mA, 35 kV, and 5 s per step with a step size of 0.02°. The mineral composition of magnetosome was determined by comparing sample diffraction patterns to mineral standards provided by the JCPDS files.

In vitro haemolytic assay

Haemolytic activity was performed as reported by Suthindhiran and Kannabiran (2009). Human blood (O+ve) from healthy volunteers were collected and washed with 0.9% saline solution. The cells were centrifuged at 150×g for 5 min, and then the supernatant was discarded. The pellet obtained was diluted in 0.9% saline (1:9) followed by dilution in PBS (1: 24) containing boric acid (0.5 mM) and calcium chloride (1 mM). The assay was performed in 96-well plates. To each well about 100 µl of 0.85% saline containing CaCl2 (10 mM). Water was used as a negative control. 100 µl of different concentrations of the magnetosomes (0, 10, 50, 100, 150 µg/ml) were added to the wells, and 0.1% of TritonX is used as a positive control. 100 µl of 2% erythrocytes in 0.85% saline with CaCl2 (10 mM) and incubated for 30 min. After incubation, the contents were centrifuged, and the supernatant was taken, and absorbance was measured at 540 nm. The morphological changes in the erythrocytes were determined as reported by Kondo and Tomizawa (1968). Blood sample (O+ve) was collected from the healthy human donor was centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. About 1 ml of the erythrocyte suspension containing buffer was taken in a microcentrifuge tube and different concentration of magnetosomes was added and incubated for 30 min. Then the cells were observed under light microscope (Labomed, CA, USA).

Genotoxicity in WBC’s

The methodology was adopted from Fenech (2000). Briefly, about 5 ml of Hikaryo XL RPMI ready mix media (contains Phytohaemagglutinin) was added to a fresh tube, and 0.5 ml of heparinized blood (50 drops) was inoculated. The cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, the magnetosomes (10–150 µg/ml) and one µg/ml mitomycin C (positive control) were added and incubated for 24 h. The content of the tube was mixed gently by shaking and kept for 72 h in standing position. CO2 was released after every 24 h by slightly rotating the screw cap of the tube. At the end of 72 h of incubation, 60 µl of colchicine was added to each tube and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. After incubation, the contents were centrifuged at 238×g for 10 min. The supernatant was carefully removed, and 6 ml of prewarmed hypotonic solution (0.075 M) was added. The contents were mixed with Pasteur pipette and incubated at 37 °C for 6 min. 1–2 drops of cell button mix were dropped over the slides (chilled) using glass pasture pipette and dried immediately on a hot plate (40 °C) and then incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The slides were placed in a Coplin jar containing Giemsa stain for 4 min and destained with double distilled water. The slides are then viewed under 100X oil immersion objective of the microscope to confirm for the chromosome aberration (Weswox, India).

MTT cell proliferation assay

Mouse macrophage cell line (J774) was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA), maintained in a culture medium consisting of RPMI 1640 medium (Himedia, India), heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (10%), penicillin (0.1 unit/ml) and streptomycin (100 pug/ml) (Gibco). The cytotoxic activity of the magnetosomes was evaluated on the cell lines using EZcount MTT Cell Assay kit (Himedia, India) as per the user manual. About 5 × 105cells/ml were cultured in 96-well plates till the cells reach confluency. The magnetosomes (0–150 µg/ml) were added to the cells and incubated in the CO2 incubator. After incubation, the MTT reagent was added to each well and incubated for about 4 h at 37 °C. The solubilization buffer was added to the each well and incubated for 1 h. The OD was measured at 570 nm using 96-well plate reader (Bio-Tek, USA). The experiment was carried out in triplicates. The culture medium dissolved in DMSO was used as a control. The number of viable cells was calculated using the formula

The cell lines treated with different concentrations of magnetosomes were also checked for the morphological alterations under inverted microscope (Magnification: ×40).

Phytotoxicity on onion root tip

Healthy onion (Allium cepa) was purchased from the local market. The dry scales were removed from the onion. The healthy onions were grown in the dark in a glass beaker with water supply for every 24 h at a temperature of 28 ± 2 °C. When the root length reached about 2–3 cm, they were treated with different concentrations of magnetosomes (0, 10, 50, 100, 150 µg/ml) for about 4 h. For each concentration, triplicates were made for statistical analysis. The onion root tips exposed to magnetosomes were collected. The slides were prepared by treating the root tips with acetocarmine (Squash technique) (Borboa and De la Torre 1996). Briefly, the onion root tips were treated with 1 N HCl for 5 min, rinsed with distilled water and then attained with 1% acetocarmine. The staining procedure was continued for about 5–10 min. Then the root tips were squashed with the cover slips and viewed under a microscope. The cytological changes were observed, and the mitotic index was calculated as reported by Fiskesjo (1997).

Toxicity assessment on fishes

Collection and maintenance of fishes

Oreochromis mossambicus (Tilapia) was used for the study. The specimens were collected from aquaculture fish farm (Walajah, Tamilnadu). Tilapia were kept in 40-l tanks and supplied with aerated tap water continuously. The weight of the fishes was 5 g approximately. The fishes were fasted prior to the test.

Acute toxicity tests

The fish tilapia was treated with different concentrations of magnetosomes (0, 50, 100, 150 µg/l) in 100 ml of water for about 1 h then the entire setup was transferred to 1-l fish tank. The fish were divided into five treatment groups with five fish in each group. These treatments were as follows: Group1: control, group 2: fishes treated with 50 µg/l of magnetosomes, group 3: fishes treated with 100 µg/l of magnetosomes, group 4: fishes treated with 150 µg/l of magnetosomes. The mortality and swimming behaviour was checked for a period of 48 h. After the test period, the fishes were killed by transferring the fish to cold water. The organs such as gills and muscles were collected and stored in 10% formalin for histopathology analysis. The tissue sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin stain and viewed in a microscope under ×40 magnification (Weswox, India).

Results and discussion

Extraction and characterisation of magnetosomes

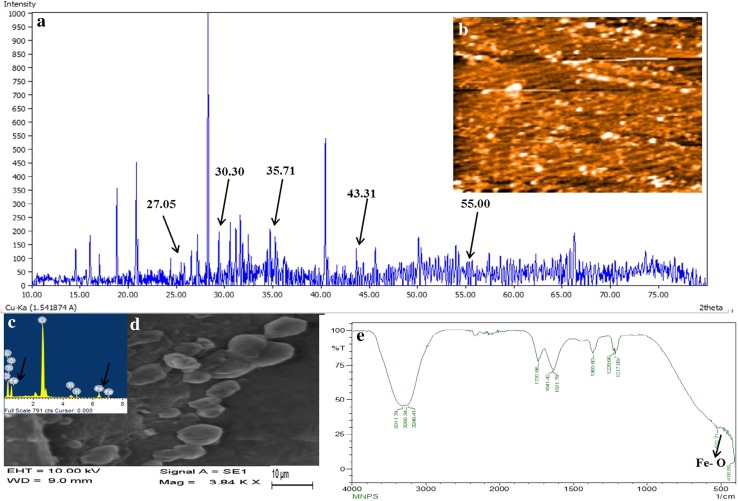

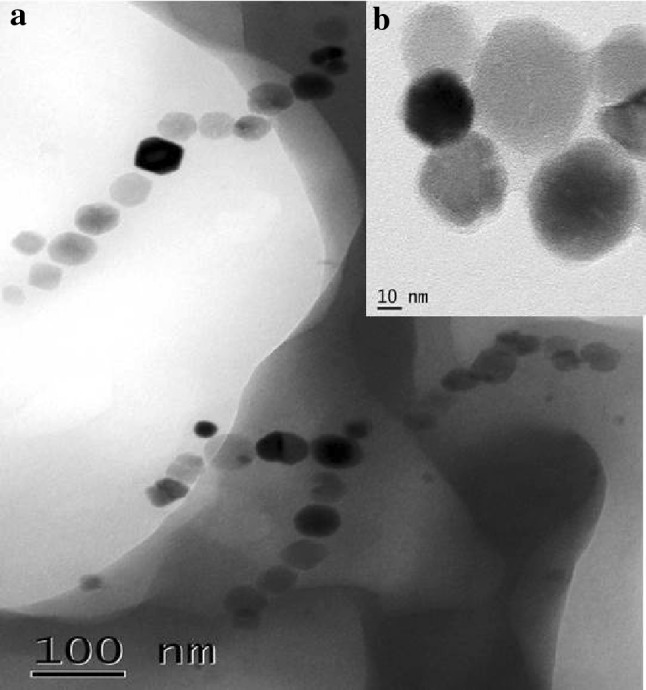

Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense (MSR-1) was grown in MSGM media, and an average of 10 mg of magnetosome was obtained from 1 l of culture. XRD result of extracted magnetosome was presented in Fig. 1a. The peaks at 27.05, 30.30, 35.71, 43.31, 55, corresponds to the Fe3O4. EDX (Fig. 1c) analysis showed the presence of high amount of chlorine and low amount of Fe and Ti in magnetosomes. The presence of chlorine ion might have detected from the Tris–HCl buffer used for magnetosome extraction. The FTIR spectrum showed in Fig. 1e exhibits two peaks, in 418 and 522/cm that are due to the stretching vibration mode associated with the metal–oxygen absorption band (Fe–O bonds in the crystalline lattice of Fe3O4). The cubo-octahedral shape of the magnetosome is also evident from the SEM and HRTEM micrograph (Figs. 1d, 2).

Fig. 1.

Characterisation of extracted magnetosomes a XRD analysis b AFM analysis c EDX analysis d SEM analysis e FTIR analysis

Fig. 2.

Transmission electron microscopy image a TEM image of bacterial magnetosome arranged in a chain. b Individual magnetosome extracted after treatment with 1% SDS shows the cubo-octahedral shape

Toxicity assessment in RBC’s

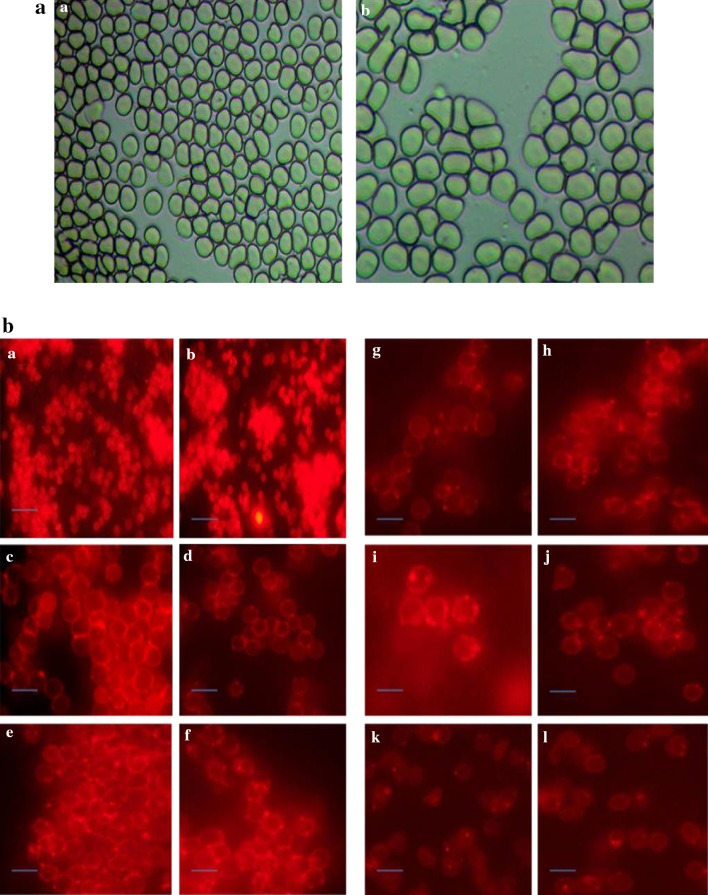

The effect of various concentrations of magnetosomes (10, 20, 50, 100, 150 µg/ml) against RBC’s were evaluated by haemolytic assay and morphological alterations. The in vitro haemolytic assay revealed that the magnetosomes are non-toxic to RBC’s (Fig. 3b). The maximum haemolysis observed was 3.5% at a concentration of 150 µg/ml of magnetosome. Microscopic examination revealed that the RBC’s treated with magnetosomes retained its normal biconcave shape which is evident in the Fig. 3a. There were no detectable morphological changes observed between the control and treated RBC’s. Knizocytosis (cells with more than two concavities), spherostomatocytes (cells with cupped profiles) and echinocytes (spiny formation on the surface of the cells) were not observed even at higher (150 µg/ml) concentration.

Fig. 3.

a Morphological changes in human erythrocytes treated with magnetosomes (a) Human erythrocytes treated with PBS as control (b) Human erythrocytes treated with magnetosomes (150 µg/ml). b Effect of different concentrations of magnetosomes on human erythrocytes morphology. Microscopic images of RBC’s (a and b) erythrocytes treated with PBS as control (c and d) RBC’s treated with 10 µg/ml magnetosomes, (e and f) RBC’s treated with 20 µg/ml magnetosomes, (g and h) RBC’s treated with 50 µg/ml magnetosomes, (i and j) RBC’s treated with 100 µg/ml magnetosomes, (k and l) RBC’s treated with 150 µg/ml magnetosomes. (Magnification: ×40)

Nanoparticles, when used for biomedical applications, will be injected into blood streams will adhere to the surface of RBC’s and even they can enter the cell and cause severe damage. The erythrocytes are considered as good models to study toxicity as most of the major functions like active and transport mechanism takes place (Ballas and Krasnow 1980). Under normal conditions, RBC’s are biconcave in shape, but when some foreign species is being introduced the outer and inner membrane is affected (Iglic et al. 1998). In our study, the magnetosomes have been found to settle on the surface of the RBC’s, but no severe structural changes have been detected (Fig. 3a, b). The maximum haemolysis was found to be 3.5% which is within the range of below 5% the critical safe hemolytic ratio for biomaterials according to ISO/TR. 7406. This indicates that magnetosome possesses good blood compatibility.

In some cases, magnetic nanoparticles could interfere with the biological function of the cell when internalized to the cell (Solanki et al. 2008; Barakat 2009). In other cases, however, SPIONs attached to the cell surface may interfere with cell surface interaction (Solanki et al. 2008). Another study by Rotherham and El Haj (2015) proved that functionalised MNP could affect the cell signalling pathways by stimulating the surface receptors (Rotherham and El Haj 2015). Morphological changes such as echinocyte formation were not detected in this study. The hemolysis of RBC’s was not detected using iron oxide nanoparticles in a study carried out previously by Moersdorf et al. (2010), but in contrary the hemolysis of magnetic nanoparticles stabilized with citric acid in animal RBC’s have been reported (Creangă et al. 2009).

Genotoxicity in WBC’s

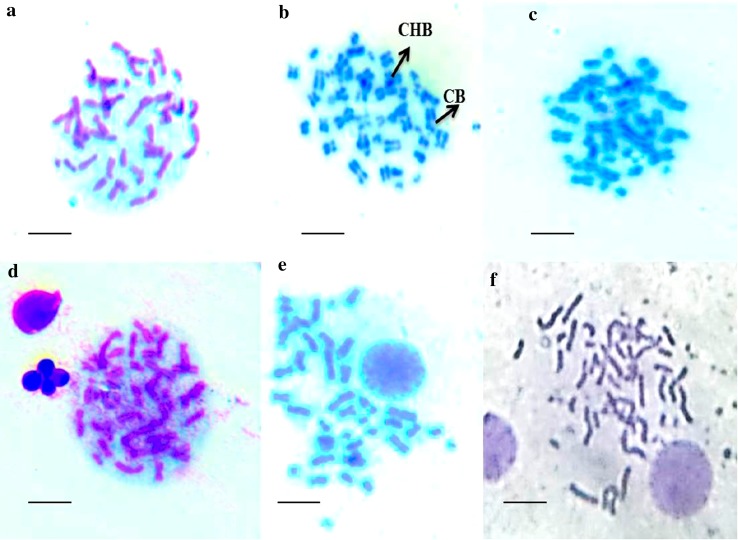

Genotoxicity evaluation of magnetosomes (10, 50, 100, 150 µg/ml) was carried out on human WBC’s. The samples treated with positive control mitomycin C (1 µg/ml) showed chromosomal Gaps, chromosome break and chromatid break. Whereas the samples treated with magnetosomes does not exhibit any changes in the chromosomes (Fig. 4). The samples treated with a magnetosome concentration of 150 µg/ml displayed a single chromosome break and chromatid break out of 50 observed metaphases (Table 1). Similarly, in the other lesser concentrations, single chromosome break was observed among 50 metaphases.

Fig. 4.

Genotoxicity evaluation of magnetosomes on human WBC’s. a Chromosomes with Giemsa stain at metaphase stage in Control sample. b Chromosomes with Giemsa stain at metaphase stage in sample treated with mitomycin (1 µg/ml). c Chromosomes with Giemsa stain at metaphase stage in sample treated with magnetosomes (10 µg/ml). d Chromosomes with Giemsa stain at metaphase stage in sample treated with magnetosomes (50 µg/ml). e Chromosomes with Giemsa stain at metaphase stage in the sample treated with magnetosomes (100 µg/ml). e and f Chromosomes with Giemsa stain at metaphase stage in sample treated with magnetosomes (150 µg/ml) CB chromatid break, Ch.B chromosome break

Table 1.

Results of frequencies of chromosome aberrations tests

| Treatment | Concentration (μg/ml) | Total number of metaphase | Number of chromosome aberration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | CB | PL | CH.B | Others | |||

| Control | – | 50 | – | – | 1 | 1 | – |

| Positive control (Mitomycin) | 1 | 50 | 20 | 2 | – | 5 | – |

| Magnetosome | 10 | 50 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| 50 | 50 | 1 | – | – | – | – | |

| 100 | 50 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | – | |

| 150 | 50 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | – | |

G gap, CB chromatid break, PL pulverizations, CH.B chromosome break. Others include dicentric chromosome

The genotoxicity assessment with WBC’s reveals that among the 50 metaphases, only a single gap and single chromatid break in the highest concentration (150 µg/ml) where in about 20 gaps were found in the positive control (Fig. 4). The presence of lipid bilayer membrane around the iron mineral may result in less genotoxicity with great potential for biocompatibility (Qi et al. 2016). The presence of carboxyl and amide group enhances the hydrophobicity of magnetosome when compared with magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) and thereby reduce the toxicity (Yan et al. 2012). Previous reports demonstrate that nanoparticles coated with lipid monolayer are less toxic than free nanoparticles (Sharma et al. 2012).

Cytotoxicity on mouse macrophage cell line (J774)

The results of MTT assay confirmed that the cells exposed to magnetosomes resulted in no or less toxicity. At 10 μg/ml of concentration, the viability of cells decreased from 100 to 98.5%. With the increase in the concentration of magnetosomes (0–150 μg/ml), the percentage of viability decreased from 100 to 92.5% (Fig. 5a). The morphology of the macrophage cells treated with magnetosomes is given in the Fig. 5b. Differences in cellular morphology were not detected. Accumulation of granular material, cytoplasmic protrusions and vacuolisation were not observed (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

a Cytotoxic activity of magnetosomes on toxicity assessment in murine macrophage cell line J774. Macrophages were treated with different concentrations of magnetosome for 24 h cell viability was determined by MTT assay. b: Morphology of J774 cell line before and after treatment with magnetosomes. (a) Cells treated with PBS (control) No detectable morphological changes were observed. (b) Cells treated with magnetosome (10 µg/ml) (c), cells treated with magnetosome (100 µg/ml) (d) Cells treated with magnetosome (150 µg/ml)

Magnetic particles have been found to be taken up by cell types such as lung cells, liver cells, stem cells, kidney cells, macrophages, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, epithelial cells and cancer cells (Mahmoudi et al. 2011). Nanoparticles when introduced into the body for various applications, they are phagocytosed by macrophages (Mahajan et al. 2010). Macrophages are unique as they have the ability to enter tissues and reside there. Thus, we studied the toxicity of magnetosomes in J774 cells, and the results state that they are non-toxic at a concentration of 10–150 µg/ml (Fig. 5a). A similar study was carried out using SPIONS (superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles) wherein no toxicity was detected up to 100 µg/ml concentrations (Naqvi et al. 2010), but when their exposure time is increased to 6 h the viability was reduced from 95 to 55%.

Toxicity assessment in onion root tip

The mitotic index of the control and treated samples are given in the Table 2. The mitotic index was found to be (62 ± 0.2%) at 150 µg/ml concentration, whereas the MI of Allium cepa treated with 10–150 µg concentration was found to be similar as that of control. The microscopic analysis revealed the differences in the mitotic index after exposure to magnetosomes. The abnormalities such as chromosome breaks, laggard chromosome, clumped chromosomes and stickiness in the chromosome were not observed in control and treated groups (Fig. 6). Dose-dependent toxicity was observed as an increase in the concentration resulted in changes in the mitotic index (MI). From the study, it is clear that at the lower concentrations, phytotoxicity was not detected.

Table 2.

Mitotic abberations in the root tip cells of A. cepa treated different magnetosome concentration

| Mitotic phases | MI | PI | A% | T% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metaphase | 62 ± 0.2 (control = 64) | 12 | 1.6 | 3.4 |

| Anaphase | 10 ± 5 | 13.5 | 2.0 | 2.3 |

| Telophase | 12 ± 3 | 15.8 | 1.8 | 4.5 |

| Prophase | 15 ± 2.2 | 5 | 3.3 | 7 |

| Interphase | 4 ± 3 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 2.2 |

MI, PI, A and T refers to mitotic index, phase index, anaphase and telophase index. About 100 cells were scored per test sample

Fig. 6.

Various stages of mitosis in the meristematic cells of Allium cepa treated with 150 µg/ml concentration, a anaphase, b early prophase and metaphase, c prophase, d telophase. No notable changes were observed. The scale bar represents 2 µm

Toxicity studies in Allium cepa, revealed the non-toxic nature of magnetosomes at different (150 µg/ml) concentrations (Fig. 6). There are no reports on the toxicity of the iron oxide nanoparticles in A. cepa. Zhu et al. (2008) reported the accumulation of iron oxide nanoparticles in plants when the plants were grown in the presence of iron oxide particles. In contrary, studies by García et al. 2011 on the phytotoxicity and aquatic toxicity showed a low or no toxicity of iron oxide nanoparticles in plant seeds, but D. magna exhibited sensitivity towards iron oxide nanoparticles. Our study indicates that the magnetosomes does not induce phytotoxicity in onion root tip even at higher concentration.

Toxicity assessment in fishes

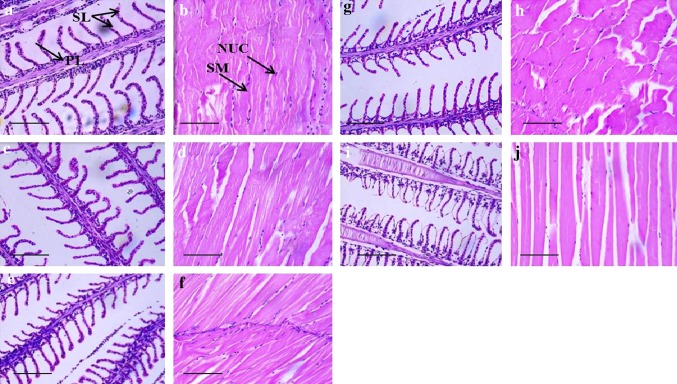

Relatively very less/no reports are available on the toxicity of magnetic particles in fish models. Five groups of the fish were used for this (10, 50, 100, 150 µg/ml). The treatment period is for about 48 h. No mortality among fishes was observed in control group and also in treated group (10, 50, 100, 150 µg/l). Similarly, no notable behavioural changes and mortality were observed after 48 h of treatment with magnetosomes. Mucous secretion was not observed in the tanks. However, decrease in the respiration and movement was observed at 150 µg/l concentration.

Toxicity studies in the fish model (Oreochromis mossambicus) revealed that there were no detectable changes in the histopathology of gills and muscles of fishes treated with magnetosomes (Fig. 7). Histopathology analysis revealed gill injury at a higher concentration as reports state that nanoparticles in the liquid phase could present either a respiratory or dietary exposure risk. Due to the larger surface area of gills, it can accumulate nanoparticles (Smith et al. 2007). This study serves as the basis for further studies on the understanding of the toxicity of the magnetosomes on different models.

Fig. 7.

Microphotographs of histopathological changes by different concentrations of magnetosomes in the gills and muscle of Oreochromis mossambicus a Gill section of control group Tilapia exposed to tap water showing normal structure of primary lamella (PL) and secondary lamella (SL). b Muscle section of control group Tilapia exposed to tap water showing SM skeletal muscle cytoplasm, NUC nucleus. c and d Gills and muscle sections of Tilapia treated with 10 µg of magnetosomes. e and f Gills and muscle sections of Tilapia treated with 50 µg/ml of magnetosomes. g and h Gills and muscle sections of Tilapia treated with 100 µg/ml of magnetosomes. i and j Gills and muscle sections of Tilapia treated with 150 µg/ml of magnetosomes. No abnormality is seen within the gills and muscles. The scale bar represents 50 µm

Magnetosomes did not induce malformations in the fish body. No aggressive behaviour or changes in the colour of the body was observed at lower concentrations (10, 50 and 100 µg/l). Histopathological studies revealed the structural organisation of the lamella in the control group and also in the treated group (lower concentration) are unaltered. Whereas at 150 µg/l, histopathological analysis of the gills revealed damage in the epithelial cells and increased in the interlamellar space (Fig. 7).

Conclusion

In this paper, we have investigated the toxicity assessment of magnetosomes using both in vivo and in vitro assays. Our study shows that the magnetosomes are not toxic. However, a detailed study of the toxicity of magnetosomes on long term exposure will reveal their possibility of use in various applications.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Department of Science and Technology (Science and Engineering Board), Govt. of India via Grant #SR/FT/LS-11/2012. The authors wish to thank the management of VIT University for providing necessary facilities for the research. The authors acknowledge the powder XRD and FTIR facility at SAS, VIT University, and Vellore. We would like to thank sophisticated test and instrumentation Centre (STIC), CUSAT, Cochin, India for assistance with acquisition of TEM images.

Abbreviations

- MTB

Magnetotactic bacteria

- RBC

Red blood cells

- WBC

White blood cells

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

- HRTEM

High-resolution transition electron microscope

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- XRD

X-ray powder diffraction

- AFM

Atomic-force microscopy

- EDX

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

- DSMZ

Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen

- MSGM

Magnetospirillum growth medium

- PBS

Phosphate buffer saline

- RPMI

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

- MI

Mitotic index

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Further, there is no conflict of interest to any of the authors, and there are no financial implications in publishing this work.

Contributor Information

T. Revathy, Phone: 9994718189, Email: gr.revathy@gmail.com

M. A. Jayasri, Phone: 9944024206, Email: jayari.ma@vit.ac.in

K. Suthindhiran, Phone: 919944367090, Email: ksuthindhiran@vit.ac.in, Email: sudhindhira@gmail.com

References

- Alphandéry E, Guyot F, Chebbi I. Preparation of chains of magnetosomes, isolated from Magnetospirillum magneticum strain AMB-1 magnetotactic bacteria, yielding efficient treatment of tumors using magnetic hyperthermia. Int J Pharm. 2012;434:444–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballas SK, Krasnow SH. Structure of erythrocyte membrane and its transport functions. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1980;10:209–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat NS. Magnetically modulated nanosystems: a unique drug-delivery platform. Nanomedicine. 2009;4:799–812. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazylinski DA, Frankel RB. Magnetosome formation in prokaryotes. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:217–230. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry CC, Curtis AS. Functionalisation of magnetic nanoparticles for applications in biomedicine. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2003;36:R198. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/36/13/203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore RP, Maratea D, Wolfe RS. Isolation and pure culture of a freshwater magnetic spirillum in chemically defined medium. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:720–729. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.2.720-729.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borboa L, De la Torre C. The genotoxicity of Zn (II) and Cd (II) in Allium cepa root meristematic cells. N Phytol. 1996;134:481–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1996.tb04365.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin VL. The potential environmental impact of engineered nanomaterials. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1166–1170. doi: 10.1038/nbt875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creangă DE, Culea M, Nădejde C, Oancea S, Curecheriu L, Racuciu M. Magnetic nanoparticle effects on the red blood cells. J Phys Conf Ser. 2009;170:012–019. [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M. The in vitro micronucleus technique. Mutat Res Fund Mol Mech Mut. 2000;455:81–95. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(00)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiskesjo G. Assessment of a chemical's genotoxic potential by recording aberration in chromosomes and cell divisions in root tips of Allium cepa. Environ Toxicol Water Qual. 1997;9:235–241. doi: 10.1002/tox.2530090311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García A, Espinosa R, Delgado L, Casals E, González E, Puntes V, Barata C, Font X, Sánchez A. Acute toxicity of cerium oxide, titanium oxide and iron oxide nanoparticles using standardized tests. Desalination. 2011;269:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2010.10.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grover VA, Hu J, Engates KE, Shipley HJ. Adsorption and desorption of bivalent metals to hematite nanoparticles. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2012;31:86–92. doi: 10.1002/etc.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünberg K, Müller EC, Otto A, Reszka R, Linder D, Kube M, Schüler D. Biochemical and proteomic analysis of the magnetosome membrane in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:1040–1050. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.2.1040-1050.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann A, Thierbach S, Semisch A, Hartwig A, Taupitz M, Rühl E, Graf C. Highly monodisperse water-dispersable iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J Mater Chem A. 2010;20:7842–7853. doi: 10.1039/c0jm01169j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Hu B. Silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles modified with γ-mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane for fast and selective solid phase extraction of trace amounts of Cd, Cu, Hg, and Pb in environmental and biological samples prior to their determination by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Spectrochim Acta B. 2008;63:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.sab.2007.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huber DL. Synthesis, properties, and applications of iron nanoparticles. Small. 2005;1:482–501. doi: 10.1002/smll.200500006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hungate RE. A roll tube method for cultivation of strict anaerobes. Method Microbiol. 1969;3B:117–132. doi: 10.1016/S0580-9517(08)70503-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iglič A, Kralj-Iglič V, Hägerstrand H. Amphiphile induced echinocyte-spheroechinocyte transformation of red blood cell shape. Eur Biophys J. 1998;27:335–339. doi: 10.1007/s002490050140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadka P, Ro J, Kim H, Kim I, Kim JT, Kim H, Lee J. Pharmaceutical particle technologies: An approach to improve drug solubility, dissolution and bioavailability. Asian J Pharmacol. 2014;9:304–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Tomizawa M. Hemolysis by nonionic surface-active agents. J Pharm Sci. 1968;57:1246–1248. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600570740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan S, Prashant CK, Koul V, Choudhary VK, Dinda A. Receptor specific macrophage targeting by mannose-conjugated gelatin nanoparticles-an in vitro and in vivo study. Curr Nanosci. 2010;6:413–421. doi: 10.2174/157341310791658928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi M, Azadmanesh K, Shokrgozar MA, Journeay WS, Laurent S. Effect of nanoparticles on the cell life cycle. Chem Rev. 2011;111:3407–3432. doi: 10.1021/cr1003166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moersdorf D, Hugounenq P, Phuoc LT, Mamlouk-Chaouachi H, Felder-Flesch D, Begin-Colin S, Pourroy G, Bernhardt I. Influence of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles on red blood cells and Caco-2 cells. Adv Biosci Biotechnol. 2010;1:439–443. doi: 10.4236/abb.2010.15057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi S, Samim M, Abdin M, Ahmed FJ, Maitra A, Prashant C, Dinda AK. Concentration-dependent toxicity of iron oxide nanoparticles mediated by increased oxidative stress. Int J Nanomed. 2010;5:983–989. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S13244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Nations S, Wages M, Cañas JE, Maul J, Theodorakis C, Cobb GP. Acute effects of Fe2O3, TiO2, ZnO and CuO nanomaterials on Xenopus laevis. Chemosphere. 2011;83:1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noori A, Parivar K, Modaresi M, Messripour M, Yousefi MH, Amiri GR. Effect of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles on pregnancy and testicular development of mice. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10:1221–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Oestreicher Z, Valverde-Tercedor C, Chen L, Jimenez-Lopez C, Bazylinski DA, Casillas-Ituarte NN, Lower BH. Magnetosomes and magnetite crystals produced by magnetotactic bacteria as resolved by atomic force microscopy and transmission electron microscopy. Micron. 2012;43:1331–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankhurst QA, Connolly J, Jones SK, Dobson JJ. Applications of magnetic nanoparticles in biomedicine. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2003;36:R167. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/36/13/201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L, Lv X, Zhang T, Jia P, Yan R, Li S, Zou R, Xue Y, Dai L. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of bacterial magnetosomes against human retinal pigment epithelium cells. Sci Rep. 2003;6:26961. doi: 10.1038/srep26961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotherham M, El Haj AJ. Remote activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway using functionalised magnetic particles. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruys AJ, Mai YW. The nanoparticle-coating process: a potential sol-gel route to homogeneous nanocomposites. Mater Sci Eng R Rep A. 1999;265:202–207. doi: 10.1016/S0921-5093(98)01126-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salata OV. Applications of nanoparticles in biology and medicine. J Nanobiotechnol. 2004;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Madhunapantula SV, Robertson GP. Toxicological considerations when creating nanoparticle-based drugs and drug delivery systems. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012;8:47–69. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2012.637916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJ, Shaw BJ, Handy RD. Toxicity of single walled carbon nanotubes on rainbow trout, (Oncorhynchus mykiss): respiratory toxicity, organ pathologies, and other physiological effects. Aquat Toxicol. 2007;82:94–109. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanki A, Kim JD, Lee KB. Nanotechnology for regenerative medicine: nanomaterials for stem cell imaging. Nanomed Uk. 2008;3:567–578. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.4.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthindhiran K, Kannabiran K. Cytotoxic and antimicrobial potential of actinomycete species Saccharopolyspora salina VITSDK4 isolated from the Bay of Bengal Coast of India. Am J Infect Dis. 2009;5:90–98. doi: 10.3844/ajidsp.2009.90.98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tartaj P, del Morales Puerto Mo, Veintemillas-Verdaguer S, González-Carreño T, Serna CJ. The preparation of magnetic nanoparticles for applications in biomedicine. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2003;36:R182. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/36/13/202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich S, Kube M, Schübbe S, Reinhardt R, Schüler D. A hypervariable 130-kilobase genomic region of Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense comprises a magnetosome island which undergoes frequent rearrangements during stationary growth. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7176–7184. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7176-7184.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Yue X, Zhang S, Chen P, Xu Z, Li Y, Li H. Biocompatibility evaluation of magnetosomes formed by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Mater Sci Eng C. 2012;32:1802–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2012.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Liu T, Gao J, Su Y, Shi C. Recent development and application of magnetic nanoparticles for cell labeling and imaging. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2010;10:193–202. doi: 10.2174/138955710791185073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu MT, Feng WY, Wang B, Wang TC, Gu YQ, Wang M, Wang Y, Ouyang H, Zhao YL, Chai ZF. Comparative study of pulmonary responses to nano- and submicron-sized ferric oxide in rats. Toxicology. 2008;247:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]