Abstract

Introduction

Zoon’s balanitis, also referred to as balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis (BCP), is an idiopathic, benign inflammatory condition of the glans penis and foreskin most often seen in elderly uncircumcised men. A patient with a biopsy-confirmed diagnosis of BCP who was successfully treated with topical mupirocin ointment is described.

Methods

The PubMed database was searched with the key words: bactroban, balanitis, cell, circumscripta, mupirocin, plasma, plasmacellularis, tacrolimus, Zoon. The papers generated by the search and their references were reviewed.

Results

Treatments for BCP have previously included circumcision and topical calcineurin inhibitors. Our patient with BCP rapidly resolved after initiating treatment with mupirocin 2% ointment.

Conclusion

BCP is a benign dermatosis affecting the glans penis and foreskin. We confirm an earlier observation demonstrating successful management of this condition with topical mupirocin 2% ointment. Previously reported therapies include circumcision, topical calcineurin inhibitors, phototherapy, and laser therapy. However, based on our observations, topical mupirocin 2% ointment therapy may be considered for the initial management of patients with suspected BCP. Prompt response to mupirocin 2% ointment is highly suggestive of the diagnosis of BCP since morphologically similar skin conditions do not respond to this treatment.

Keywords: Bactroban, Balanitis, Cell, Circumscripta, Mupirocin, Plasma, Plasmacellularis, Tacrolimus, Zoon

Introduction

In 1952, Zoon described eight men with chronic balanitis who were initially diagnosed with erythroplasia of Querat [1]. Histological assessment of these lesions revealed extensive infiltration of plasma cells. However, the lesions lacked cytological atypia and dysplasia of the epidermis; thus, Zoon reported the condition as circumscribed plasma cell balanoposthitis. Subsequently, the condition has been referred to as Zoon’s balanitis, but is also known as balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis (BCP) [2].

BCP is not common. Indeed, it often provides a therapeutic challenge once the diagnosis is established. A man with biopsy-confirmed BCP is described whose condition rapidly improved after initiating topical therapy with mupirocin 2% ointment. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for being included in the study.

Case Report

A 51-year-old healthy, heterosexual, monogamous man presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic red lesion on his foreskin and glans penis. He had no history of sexually transmitted disease or HIV-associated risk factors. He presented with a 2-year history of intermittent pruritus at the site of the rash on his penis. He had been previously treated with clotrimazole 1% cream without improvement.

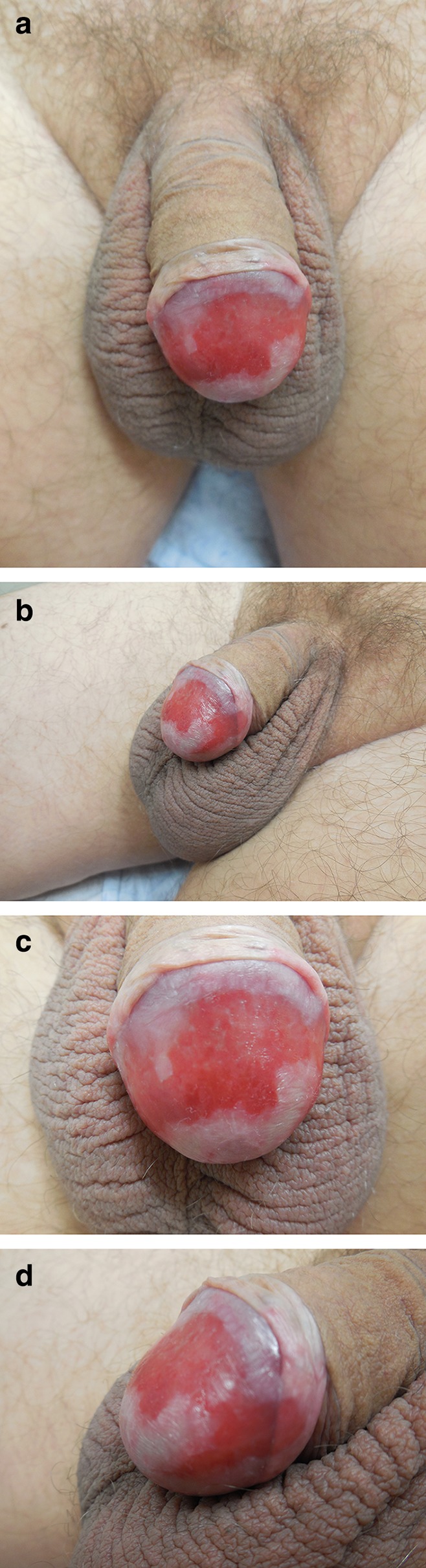

Clinical exam revealed an uncircumcised male. Retraction of the foreskin demonstrated a confluent, erythematous, erosive, mucosal plaque on the lateral and dorsal glans penis, extending to involve the coronal and adjacent prepuce (Fig. 1). The differential diagnosis included autoimmune bullous disease, BCP, candidiasis, dermatitis, erythroplasia of Querat, and lichen planus.

Fig. 1.

Distant (a, b) and closer (c, d) views of erythematous, shiny, confluent red plaque on the lateral and dorsal glans penis with extension to the adjacent foreskin

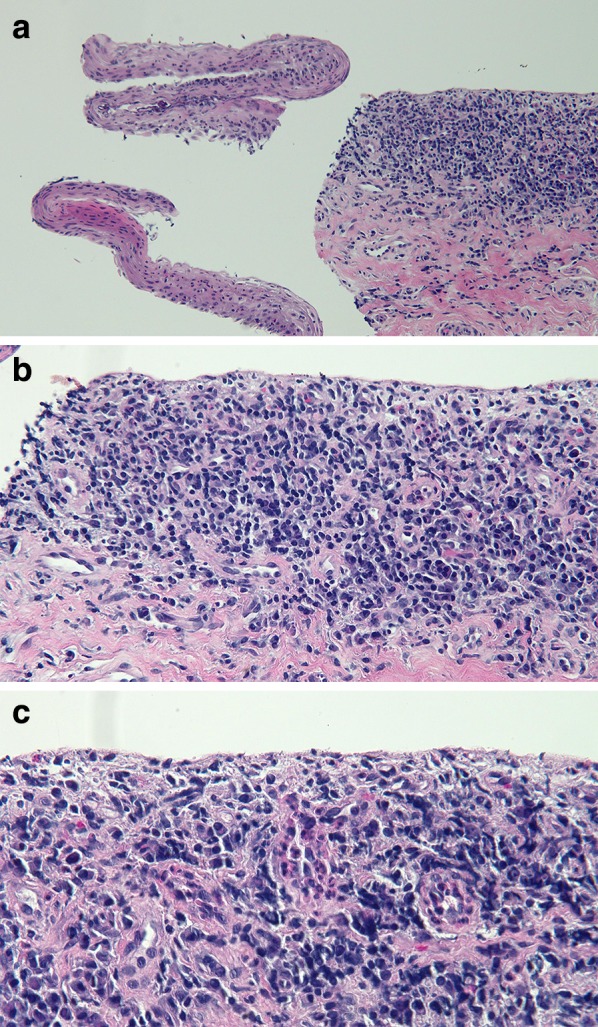

Microscopic examination of the biopsy from the glans penis revealed a submucosa with a band-like infiltrate composed of abundant lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig. 2). Parakeratosis and occasional neutrophils were also evident in the superficial epithelium. Correlation of the patient’s history, lesional morphology, and pathologic changes established a diagnosis of BCP.

Fig. 2.

Low (a), medium (b), and higher (c) magnification views of biopsy from glans penis. Focal loss of superficial mucosa from underlying submucosa is evident in the low-magnification view. The submucosa reveals an infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The superficial epithelium reveals parakeratosis and rare neutrophils (hematoxylin and eosin; a ×4; b ×20; c ×40)

After the biopsy was performed, but prior to receiving results, the biopsy site and surrounding affected mucosa were treated with mupirocin 2% ointment three times daily. In addition, although not previously effective, clotrimazole 1% was applied twice daily. When the patient was contacted by telephone with the biopsy results 12 days later, he commented that there had been a dramatic improvement of his dermatosis with the new topical therapy. He stopped the antifungal cream and continued with mupirocin ointment.

Treatment with topical mupirocin resulted in the lesion’s clearance within 6 weeks of use. When he subsequently discontinued therapy, the lesion began to reappear. At his return visit, 3 months later, there was near complete resolution with focal residual erythematous plaques (Fig. 3). The residual lesions promptly resolved within a month once treatment with mupirocin 2% ointment was reinitiated.

Fig. 3.

Distant (a) and closer (b, c) views of the previously affected glans penis and foreskin after mupirocin 2% ointment treatment. The large confluent plaque is almost completely resolved, with small remnants of erythema

Discussion

BCP is a benign inflammatory dermatosis affecting the penis and foreskin in uncircumcised men. The age of onset has been observed to range from 20 to 91 years, though BCP most often occurs in elderly men; previously, the mean age of 20 patients with BCP was found to be 64.8 years [2–5]. The lesions are chronic and typically present for 1–2 years prior to diagnosis [6]. Similar clinical features are observed in women with vulvitis circumscripta plasmacellularis [7].

BCP clinically presents as erythematous plaques involving the glans, prepuce, or both. Typically the condition is asymptomatic, though pruritus or tenderness may be present [2, 8]. The lesions may occur co-incident or independent of intercourse [9]. The differential diagnosis for long-lasting erythematous penile lesions is summarized in Table 1 [2, 9, 10].

Table 1.

| Candidiasis |

| Contact dermatitis |

| Fixed drug eruption |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Herpes simplex virus |

| Lichen planus |

| Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus |

| Pemphigus vulgaris |

| Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (erythroplasia of Queyrat) |

| Psoriasis |

| Reiter’s disease |

| Secondary syphilis |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

The histopathology in BCP reveals a band-like infiltrate of plasma cells in the submucosa [1]. Atrophy of the mucosa, loss of the rete ridges, spongiosis, dilated vessels, mild fibrosis, and hemosiderin deposition have also been reported [2, 9, 11]. Notably, there is no keratinocyte dysplasia or frank vesiculation [6]. Similar lesions in other mucosal sites, such as the vaginal, perianal, and oral regions, have been reported [7, 12, 13]. Reflectance confocal microscopy may help avoid penile biopsy by differentiating between balanitis and carcinoma in situ [14].

Several treatment modalities have been described to manage patients with BCP. A series of patients treated by a single provider are uncommon, as most reports of BCP are individual cases [15]. Previously, first-line therapy has been circumcision, since the absence of foreskin removes a nidus of chronic inflammation [16, 17].

Nonsurgical intervention has been reported, which is an important consideration since patients often reject procedures in this sensitive area [21]. Some cases have shown efficacy with griseofulvin, fusidic acid, or corticosteroids. However, established therapeutic efficacy of these agents has not been repeatedly confirmed in BCP [15, 22, 23]. Cryotherapy has also been used; however, this therapy is associated with little to no response [20].

More recently, other therapeutic modalities have been used, including photodynamic and laser therapy [3, 18–20]. Photodynamic therapy, which has been used in refractory lesions, involves the application of topical porphyrin precursors (5-aminolaevulinic acid or methyl aminolevulinate) and subsequent exposure to a light source whose wavelength is appropriate for exciting the photosensitizing chemical substance [20]. The mechanism of action has not been fully elucidated; it is thought that activated T-lymphocytes are sensitive to photodynamic therapy, which leads to inhibition of cytokines that attract plasma cells to the dermis [20]. To date, phototherapy has been well tolerated with no long-term adverse effects reported [20]. Carbon dioxide and erbium:YAG lasers have been shown to be viable treatment options which are less traumatic than circumcision; both lasers offer precise ablation and have been well tolerated by patients [20].

Recently, several reports of calcineurin inhibitors, tacrolimus 0.1 and 0.03% and pimecrolimus 0.1%, have been described in the literature. Kyriakou et al. published a case series along with a review of nine reports of calcineurin inhibitor use [21]; the 30 patients reviewed applied a calcineurin inhibitor and experienced improvement or complete resolution after 3–8 weeks of therapy onset. Response was maintained in 22 of 23 patients with follow-up data of 3 months or more [21]. One patient was treated with circumcision after 3 months of calcineurin inhibitor therapy [21].

In addition to our patient, we are aware of one other man whose BCP was successfully treated with mupirocin 2% ointment (Table 2) [11]. He was a 62-year-old healthy, heterosexual male with a red lesion on his foreskin and glans penis. His primary care physician initially treated him with clotrimazole 1% cream, which improved the rash on the glans penis but not on the foreskin. Tacrolimus 0.1% ointment was prescribed, but due to an unexpected delay in receiving the medication, he continued to use mupirocin three times a day similarly to how he treated his biopsy site prior to suture removal. Complete resolution of the lesion was seen following 3 months of mupirocin monotherapy.

Table 2.

Comparison of two cases of balanitis circumscripta plasmacelluaris treated with topical 2% mupirocin ointment [11]

| C | A R |

Cir | Dur | App | Sym | Loc | His | T | Comments | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

51 Ca |

– | 2 | Red pl | Int Pru | FS + GP | Con | 2 | Clotrimazole 1% cream failed to improve patient’s lesion. Patient was prescribed mupirocin 2% ointment for biopsy site on glans penis, which he applied while continuing clotrimazole 1% cream. Patient noted improvement with the addition of mupirocin 2% ointment, so he continued this medication while halting clotrimazole 1% cream | CR |

| 2a |

62 Ca |

– | NS | Red pl | As | FS + GP | Con | 12 | Clotrimizole 1% cream improved lesion on glans penis but not on foreskin. Prescribed mupirocin 2% ointment following glans penis biopsy and was offered tacrolimus 0.1% ointment. Patient noted improvement with mupirocin 2% ointment monotherapy and opted to remain on mupirocin 2% ointment only | [11] |

A age (in years), App appearance, As asymptomatic, C case, Ca Caucasian, Cir circumcised, Con histologic confirmation of BCP, CR case report, Dur duration of BCP (in years), FS + GP foreskin and glans penis, His histologic findings, Int Pru intermittent pruritus, Loc location of lesion, Pl plaque, R race, Ref Reference, Sym symptoms, T time to resolution of BCP (in weeks), + circumcised, − uncircumcised

aA 62-year-old healthy, heterosexual, uncircumcised male presented with a red plaque on his glans penis and foreskin that was noticed when the patient was being treated with ciprofloxacin for prostatitis. The patient had phimosis and difficulty retracting his foreskin during intercourse. He was treated with clotrimizole by his primary care physician, which improved the lesion on the glans penis only. After penile biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of BCP, the patient was asked to apply mupirocin 2% ointment to the biopsy site three times each day. Though tacrolimus 0.1% ointment was offered, mupirocin 2% ointment monotherapy was continued. At follow-up, the lesion was reduced in size, and the patient opted to continue mupirocin ointment. Complete resolution was evident following 3 months of mupirocin monotherapy

Our patient experienced prompt resolution of his rash after starting mupirocin 2% ointment similar to the previously reported patient. Topical antifungal medication had been used previously without success in our patient. Also, similar to the previous patient, our patient’s dermatosis recurred if mupirocin therapy was discontinued. Thus, he has been maintained on mupirocin 2% ointment with instructions to taper the frequency of application.

The pathogenesis of BCP remains to be established. Successful management with mupirocin, an antibiotic that blocks protein synthesis, raises the possibility that BCP may directly or indirectly be implicated with bacterial infection or super-antigen [11, 24]. Other postulated mechanisms of pathogenesis include: chronic irritant contact dermatitis due to chronic Mycobacterium smegmatis infection, foreskin inflammation, friction, heat, hypospadias, IgE-antibody-mediated hypersensitivity response, lack of hygiene, nonspecific polyclonal stimulation of B cells, penile trauma, pre-malignancy, and T cell-mediated damage [2, 11, 25–31].

Conclusions

BCP is an uncommon benign dermatosis affecting the glans penis, foreskin, or both. The condition predominantly occurs in uncircumcised elderly men. Although circumcision was the gold standard therapy, more recently topical calcineurin inhibitors have been shown to be efficacious. Our observation confirms a previous report of successful management of BCP with topical mupirocin 2% ointment. The rapid and dramatic response to this therapy might also be used as a diagnostic test since other similar-appearing dermatoses lack response to this agent. In conclusion, we suggest not only that mupirocin 2% ointment may be used to confirm a suspected diagnosis of BCP prior to biopsy but also that the drug can be used possibly as initial monotherapy for resolution with periodic maintenance therapy as needed to preserve clearance of this condition.

Acknowledgements

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. No editorial assistance was used in the preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Omar Bari and Philip R. Cohen have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/0708F06041FF6F12.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13555-017-0180-7.

Contributor Information

Omar Bari, Email: obari@ucsd.edu.

Philip R. Cohen, Email: mitehead@gmail.com

References

- 1.Zoon JJ. Chronic benign circumsript plasmocytic balanoposthitis. Dermatologica. 1952;105(1):1–7. doi: 10.1159/000256880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis DA, Cohen PR. Balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis. J Urol. 1995;153(2):424–426. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199502000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wollina U. Ablative erbium:YAG laser treatment of idiopathic chronic inflammatory non-cicatricial balanoposthitis (Zoon’s disease)—a series of 20 patients with long-term outcome. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:120–123. doi: 10.3109/14764171003706125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sehgal VN, Rege VL, Malik GB. Chronic plasma cell balanitis of Zoon. Report of two cases. Br J Vener Dis. 1973;49(1):86–88. doi: 10.1136/sti.49.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggarwal N, Parwani AV, Ho J, Cook JR, Swerdlow SH. Plasma cell (Zoon) balanitis: another inflammatory disorder that can be rich in IgG4+ plasma cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(10):1437–1443. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souteyrand P, Wong E, Macdonald DM. Zoon’s balanitis (balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis) Br J Dermatol. 1981;105(2):195–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1981.tb01205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein AT, Christopher K, Burros LJ. Plasma cell vulvitis: a rare cause of intractable vulvar pruritus. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:789–790. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern JK, Rosen T. Balanitis plasmacellularis circumscripta (Zoon’s balanitis plasmacellularis) Cutis. 1980;25(1):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alessi E, Coggi A, Gianotti R. Review of 120 biopsies performed on the balanopreputial sac. From zoon’s balanitis to the concept of a wider spectrum of inflammatory non-cicatricial balanoposthitis. Dermatology (Basel) 2004;208(2):120–124. doi: 10.1159/000076484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weyers W, Ende Y, Schalla W, Diaz-cascajo C. Balanitis of Zoon: a clinicopathologic study of 45 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24(6):459–467. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee MA, Cohen PR. Zoon Balanitis revisited: report of balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis resolving with topical mupirocin ointment monotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(3):611–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitkov M, Pimentel J, Bruce A. Beefy red plaques in the perianal region. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:447–448. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon LW, Wein RO, Rosenwald I, Laver N. Plasma cell mucositis of the oral cavity: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106(6):853–860. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arzberger E, Komericki P, Ahlgrimm-siess V, Massone C, Chubisov D, Hofmann-wellenhof R. Differentiation between balanitis and carcinoma in situ using reflectance confocal microscopy. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(4):440–445. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang A, David N, Horton LW. Plasma cell balanitis of Zoon: response to Trimovate cream. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(2):75–78. doi: 10.1258/0956462011916811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallon E, Hawkins D, Dinneen M, Francics N, Fearfield L, Newson R, Bunker C. Circumcision and genital dermatoses. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136(350–354):10724196. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrándiz C, Ribera M. Zoon’s balanitis treated by circumcision. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1984;10(8):622–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1984.tb01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinto-Almeida T, Vilaça S, Amorim I, Costa V, Alves R, Selores M. Complete resolution of Zoon balanitis with photodynamic therapy—a new therapeutic option? Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:540–541. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2012.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aynaud O, Vasanova JM, Tranbaloc P. CO2 laser for therapeutic circumcision in adults. Eur Urol. 1995;28:74–76. doi: 10.1159/000475024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dayal S, Sahu P. Zoon balanitis: a comprehensive review. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2016;37(2):129–138. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.192128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyriakou A, Patsatsi A, Patsialas C, Sotiriadis D. Therapeutic efficacy of topical calcineurin inhibitors in plasma cell balanitis: case series and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2014;228(1):18–23. doi: 10.1159/000357153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerbig AW, Hunziker T. Griseofulvin ineffective in balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 Pt 1):319. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen CS, Thomsen K. Fusidic acid cream in the treatment of plasma cell balanitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:633–634. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(08)80206-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes J, Mellows G. On the mode of action of pseudomonic acid: inhibition of protein synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. J Antibiot. 1978;31:330–335. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.31.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balato N, Scalvenzi M, La Bella S, Di Costanzo L. Zoon’s balanitis: benign or premalignant lesion? Case Rep Dermatol. 2009;26(1):7–10. doi: 10.1159/000210440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter WM, Hawkins DA, Dinneen M, Bunker CB. Zoon’s balanitis and carcinoma of the penis. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11(7):484–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishimura M, Matsuda T, Muto M, Hori Y. Balanitis of Zoon. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29(6):421–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb03826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jolly BB, Krishnamurty S, Vaidyanathan S. Zoon’s balanitis. Urol Int. 1993;50(3):182–184. doi: 10.1159/000282480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toonstra J, van Wichen DF. Immunohistochemical characterization of plasma cells in Zoon’s balanoposthitis and (pre)malignant skin lesions. Dermatologica. 1986;172(2):77–81. doi: 10.1159/000249302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mccreedy CA, Melski JW. Vulvar erythema. Vulvitis chronica plasmacellularis (Zoon’s vulvitis) Arch Dermatol. 1990;126(10):1352–1353. doi: 10.1001/archderm.126.10.1352b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hague J, Ilchyshyn A. Successful treatment of Zoon’s balanitis with topical tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(10):1251–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]