Abstract

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a bioactive lipid that is characterized by a peculiar mechanism of action. In fact, S1P, which is produced inside the cell, can act as an intracellular mediator, whereas after its export outside the cell, it can act as ligand of specific G-protein coupled receptors, which were initially named endothelial differentiation gene (Edg) and eventually renamed sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors (S1PRs). Among the five S1PR subtypes, S1PR1, S1PR2 and S1PR3 isoforms show broad tissue gene expression, while S1PR4 is primarily expressed in immune system cells, and S1PR5 is expressed in the central nervous system. There is accumulating evidence for the important role of S1P as a mediator of many processes, such as angiogenesis, carcinogenesis and immunity, and, ultimately, fibrosis. After a tissue injury, the imbalance between the production of extracellular matrix (ECM) and its degradation, which occurs due to chronic inflammatory conditions, leads to an accumulation of ECM and, consequential, organ dysfunction. In these pathological conditions, many factors have been described to act as pro- and anti-fibrotic agents, including S1P. This bioactive lipid exhibits both pro- and anti-fibrotic effects, depending on its site of action. In this review, after a brief description of sphingolipid metabolism and signaling, we emphasize the involvement of the S1P/S1PR axis and the downstream signaling pathways in the development of fibrosis. The current knowledge of the therapeutic potential of S1PR subtype modulators in the treatment of the cardiac functions and fibrinogenesis are also examined.

Keywords: sphingosine 1-phosphate, sphingolipids, matrix metalloproteinases, cardiomyocytes, collagen accumulation, G-coupled receptor, cardiac fibrosis

Intracellular and Extracellular Actions of S1P

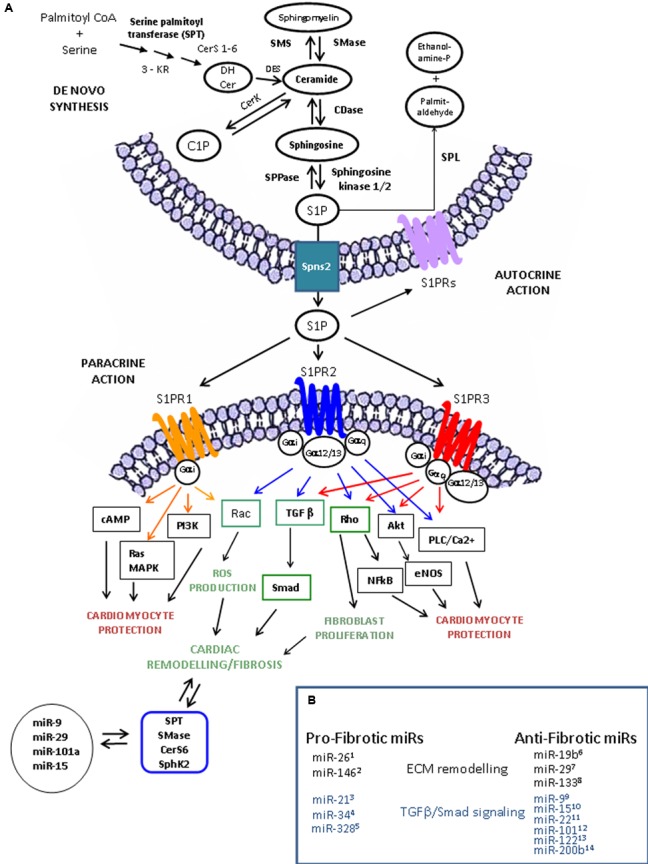

Sphingosine 1-phosphate is the intermediate breakdown product of the catabolism of complex SLs (Figure 1), a class of lipids characterized by a C8 carboamide alcohol backbone that was discovered in the brain in 1870 (Thudichum, 1884). S1P is present in the plasma, where it binds to ApoM on HDL particles, and serum albumin (Christoffersen et al., 2011). This bioactive lipid is in all types of mammalian cells (Hannun and Obeid, 2008) and, systemic and local gradients of S1P are essential for immune cell homing (Olivera et al., 2013; Nishi et al., 2014). S1P is formed from Sph by two differently localized and regulated enzyme isoforms, SphK 1 and SphK2 (Maceyka et al., 2012). Although SphK1 and SphK2 catalyze the same reaction, SphK1 inhibition/gene ablation decreases blood S1P, while SphK2 inhibition/gene ablation increases blood S1P. At the cellular level, studies have shown the involvement of SphK1 in cell survival and cell growth, whereas SphK2 is rather associated with growth arrest and apoptosis (Liu et al., 2003).

FIGURE 1.

Sphingolipid metabolism, S1P receptor-activated pathways and miR involved in cardiac remodeling and functions. (A) S1P is synthesized from sphingosine (Sph) by the sphingosine kinases, SphK1 and SphK2 and irreversible cleaved by S1P lyase (SPL), which generates hexadecenal and phosphoethanolamine. S1P is also a substrate of specific S1P phosphatases (SPPase). Ceramide derives via the sphingomyelin cycle or de novo sphingolipid synthesis involving serine palmitoyl transferase (SPT), 3-keto reductase (3KR), ceramide synthase (CerS), and desaturase (DeS), and converted reversibly to sphingosine (Sph) by ceramidase (CDase), or phosphorylated to ceramide-1-phosphate (C1P) by ceramide kinase (CerK) activity. S1P produced inside the cell can be transported in the intercellular space by an ATP-binding cassette transporter named spinster homolog 2 (Spns2). As ligand, S1P acts as autocrine and paracrine factor triggering specific signaling pathways by interacting with S1P specific heterotrimeric GTP binding protein-coupled receptors (GPCR), named S1PR. Three among five subtypes of S1PRs, S1PR-1 (orange), -2 (blue), and -3 (red), are expressed in cardiomocytes, cardiac fibroblasts and procursor cardiac cells. In heart, S1PR activation leads to different cardiac effects (profibrotic, green; antifibrotic and cardioprotective, black/red). The scheme exemplifies, in accordance with the current literature, the main pathways triggered by S1PR activation leading to cardiac cell protection and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling. Interestingly, the expression of the key enzymes involved in sphingolipid metabolism can be regulated by microRNAs (miRs) and some of them (i.e., miR-99, miR-19b6, miR-1510, and miR-297) also regulate the fibrotic process by affecting extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling through the modulation of metalloprotease (MMPs), TGF-β/TGFR and Smad protein expression. (B) miRNA in fibrosis. Several miRs have been described as regulators of cardiac fibrosis acting as pro-fibrotic or anti-fibrotic factors on ECM remodeling (black) and on TGFβ /Smad signaling (blue).1Wei et al. (2013). 2Wang et al. (2015). 3Thum et al. (2008); Roy et al. (2009), Liang et al. (2012); Dong et al. (2014), He et al. (2016). 4Bernardo et al. (2012); Huang et al. (2014). 5Du et al. (2016). 6Zou et al. (2016). 7van Rooij et al. (2008), Abonnenc et al. (2013), Zhang et al. (2014). 8Duisters et al. (2009), Castoldi et al. (2012), Chen et al. (2014), Muraoka et al. (2014), Wang et al. (2016). 9Li et al. (2016). 10Tijsen et al. (2014). 11Hong et al. (2016). 12Pan et al. (2012). 13Beaumont et al. (2014).

Sphingosine 1-phosphate acts inside cells as a signaling molecule that regulates specific targets (Maceyka et al., 2012), such as PHB2, a highly conserved protein that regulates mitochondrial assembly and function, TRAF-2, which is upregulated in fibroblasts, and NF-κB, which is crucially involved in inflammatory gene regulation (Xia et al., 2002; Alvarez et al., 2010).

However, in response to only partially known stimuli, S1P can be transported outside the cells by a specific S1P transporter, named Spns2, and upon binding to one or more of the five subtypes of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), named S1PR1-5, it triggers many downstream signaling pathways (Zu Heringdorf et al., 2013; Kihara et al., 2014; Nishi et al., 2014) (Table 1). Hla and Maciag (1990), by a differential display method, discovered the orphan GPCR Edg-1, and successively identified as a S1PR1 receptor based on the sequence homology with LPA1/Vzg-1/Edg-2. Later, other receptors, including Edg-5 and Edg-3, followed by Edg-6 and Edg-8 (now termed S1PR2, S1PR3, S1PR4 and S1PR5), were described (An et al., 1997, 2000; Goetzl et al., 1999).

Table 1.

Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors and their intracellular signaling pathways and functions.

| S1PR | Knock out phenotype | Intracellular mediators | Biological effects | Cardiac function | Agonists | Antagonists | Indications | Clinical trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S1PR1 (Edg1) Most tissues Kd (nM) (8–20) Coupled to: Gαi |

Normal until E11.5 then lethal, Liu et al., 2000 abnormal yolk sacs, defective blood and smooth muscle, vessels maturation | (-) AC (+) ERK,Rac, PI3K, Akt |

Angiogenesis Lymphocytes migration Cardiomyocytes survival |

S1PR1 agonist: Improves cardiac function following myocardial infarction S1PR1 antagonists Stroke and ischaemic pre- and post-conditioning cardioprotection |

SEW2871 FTY720-P KRP203 BAF312 ACT-128800 ONO-4641 |

VPC23019 VPC44116 W416 |

Multiple Sclerosis Crohn’s disease Polymyosites and Dermatomyosites Lupus erythematosus |

FTY720-P FDA approved ACT-12880 Phase II ONO-4641 phase II CS-0777 Phase I CYM-5442 Phase III BAF-312 Phase II KRP-203 Phase III |

|

S1PR2 (Edg5) Most tissues Kd (nM) 16–27 Coupled to: Gαi, Gαq et Gα12/13 |

Normal until 3–5 weeks, Kono et al., 2004 Excitability at cortical neurons, severe inner ear defects heart development |

(-)AC (+) AC, PLC p38MAPK Rho |

Vestibular funtion Vascular tone (contraction) Neuronal excitability Cardiomyocyte survival |

Not identified | JTE013 | |||

|

S1PR3 (Edg3) Heart Lung Spleen Kidney Intestine Kd (nM) 23–26 Coupled to: Gαi/o, Gαq, and Gα12/13 |

Normal Smaller litter size, Ishii et al., 2001 |

(-)AC (+) ERK, Rac, eNOS, PLC, Akt |

Cardiac rytm regulation Vascular tone (relaxation) Cardiomyocytes survival |

S1PR3 antagonists Inhibits the S1P-mediated reduction in coronary flow in perfused rat hearts Partially inhibits FTY720-induced bradycardia in rats in vivo |

FTY720-P KRP203 |

VPC23019 CAY1044 |

||

|

S1PR4 (Edg6) Lymphoid tissues Blood cells Lung smooth muscle Kd (nM) 12–63 Coupled to: Gαi and G1α2/13 |

Normal, Gräler et al., 1998; Schulze et al., 2011 |

(+) AC, ERK, PLC, Rho | Megakaryocyte Differentiation Vascular tone (contraction) |

FTY720-P KRP203 |

Not identified | |||

|

S1PR5 (Edg8) Brain Skin natural killer cells Kd (nM) 2–6 Coupled to: Gαi and Gα12/13 |

Normal Aberrant natural killer cells, Im et al., 2001 |

(-) AC, ERK, (+)JNK |

Oligodendrocytes survival Mielinization process |

FTY720-P KRP203 BAF312 |

Not identified | Polymyosites and Dermatomyosites | BAF-312 Phase II |

S1P binds to their specific GPCRs, which activate heterotrimeric G-proteins (defined here by their α subunits) to initiate signaling cascades leading to specific biological effects and functions in cardiac tissue. Agonists and antagonists for each specific S1PR subtypes are reported together with the clinical trials in which the drug have been successfully used. AC, adenylate cyclase; Akt, serine/threonine-specific protein kinase 1; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; JNK, c-jun N-terminal kinase; PI3K, Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase; PLC, Phospholipase C; p38MAPK, p38 Mitogen activated protein kinase; Rac, Ras related monomeric GTP hydrolase; Rho GTPase, Ras homolog GTP hydrolase; Kd, dissociation constant; (+) activation; (-) inhibition; Clinical trial: FTY720 (Gilenya, Fingolimod) NCT00662649 and NCT01436643; ACT-128800 (Actelion, Ponesimod) NCT01006265; ONO-4641 (Merck/Ono paharmaceuticals, Ceralifimod) NCT01081782; CS-0777 (Daiichi Sankyo Inc.) NCT00616733; CYM-5442 (Celgene, Ozanimod) NCT02531113; BAF-312 (Novartis, Siponimod) NCT01665144 and NCT00879658; KRP-203 (Novartis) NCT01294774 US National Library of Medicine. https://clinicaltrials.gov.

Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors are widely expressed and specifically coupled to distinct G-proteins as reported in Table 1 (Blaho and Hla, 2014; Kihara et al., 2014; Pyne et al., 2015). Recently, studies on the crystal structure of S1PR1 (Hanson et al., 2012) have indicated that the ligand likely binds the receptor by lateral access (Rosen et al., 2013). Substantial evidence has demonstrated that S1PR-mediated signaling regulates many biological processes, such as cell growth and survival, migration, and adhesion (Maceyka et al., 2012; Kunkel et al., 2013; Proia and Hla, 2015); thus, the impairment of the SphK/S1P/S1PR axis leads to many disorders, including inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer (Schwalm et al., 2013, 2015; Newton et al., 2015; Pyne et al., 2015).

Cardiac Fibrosis

Cardiac fibrosis is a multistep disorder, which arises due to several circumstances, such as inflammation, ischaemia and senescence. Myocardial integrity is assured throughout life by fibrotic remodeling of cardiac tissue that becomes decisive in the progression of cardiac disease, thus contributing to the high risk of mortality for this disease (Cohn et al., 2000; Kong et al., 2014; Gyöngyösi et al., 2017).

Fibroblasts, the major producers of cardiac ECM (Krenning et al., 2010), provide the initial structural support in the neonatal heart, respond electrically to mechanical stretch and participate in the synchronization of cardiac tissue (Tomasek et al., 2002). In chronic conditions of ischaemia or altered oxygen tension, angiotensin-aldosterone mediated oxidative/redox stress, pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic factors activate circulating bone marrow-derived fibrocytes, epithelial cells and resident fibroblasts that adopt an hypersecretory myofibroblast phenotype (Porter and Turner, 2009; van den Borne et al., 2010; Lajiness and Conway, 2014). Myofibroblasts, by acting in an autocrine/paracrine manner, start to overproduce ECM. Accumulation of abundant type I/III fibrillar collagen and a variety of bioactive substances causes stiffening of the heart and decreased cardiac function (Gyöngyösi et al., 2017). Among the factors involved in the initiation and progression of cardiac fibrosis, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and the local renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system together with other cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and endothelin-1 (Davis and Molkentin, 2014; Bomb et al., 2016), trigger many signaling pathways, such as Smad protein and GTP hydrolase (GTPase) activation (Rosenkranz, 2004; Wynn, 2008; Porter and Turner, 2009; Leask, 2010; Creemers and Pinto, 2011; Wynn and Ramalingam, 2012). In cardiac matrix remodeling, other key players include the zinc-dependent matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) (Tyagi et al., 1993; Nagase et al., 2006; Spinale, 2007; Mishra et al., 2013). Aberrant levels of different MMPs and TIMPs are highly correlated with cardiac fibrosis (Moshal et al., 2005; Ahmed et al., 2006; Spinale et al., 2013). MMP-2 and MMP-9 have distinct spatial and temporal actions in cardiovascular remodeling; MMP-2 is constitutively expressed, whereas MMP-9 is inducible (Mishra et al., 2013). In addition to their role in ECM degradation, MMPs also act on non-matrix molecules, such as growth factors, allowing local induction-activation of signaling pathways which has been demonstrated after MMP-9 ablation (Mishra et al., 2010). Among the TIMP isoforms (TIMP1-4) implicated in cardiac fibrosis (Vanhoutte and Heymans, 2010), the level of TIMP1 increases in diseased hearts (Heymans et al., 2005) and high levels of TIMP4 are found in parallel to inhibition of MMP-9. Modulation of ECM turnover and activation of MMPs and TIMPs are controlled by many factors, including TNF-α, TGF-β and ILs (Parker and Schneider, 1991; Tsuruda et al., 2004; Wynn and Ramalingam, 2012; Gyöngyösi et al., 2017). Among these factors, the hormone peptide relaxin (RLX) is a key regulator of ECM remodeling in reproductive and non-reproductive tissues (Samuel et al., 2007; Du et al., 2010; Nistri et al., 2012). Particularly, RLX inhibits pro-fibrotic cytokines (i.e., TGF-β1) and modulates the accumulation and degradation of ECM that acts on MMPs and TIMPs (Samuel et al., 2007; Bani et al., 2009; Du et al., 2010; Frati et al., 2015). Moreover, recent research has found that epigenetic factors, such as miRs play an important role in tissue remodeling by controlling MMPs and TGF-β/Smad signaling (Figure 1) (Care et al., 2007; Roy et al., 2009; Creemers and van Rooij, 2016; Biglino et al., 2017). Notably, miR expression can also be regulated by MMP-9 (Mishra et al., 2010). Therefore, this class of small non-coding RNAs, which inhibits gene expression by binding the 3′ UTRs of target mRNAs, can be crucial for the fibrotic process, acting as either pro-fibrotic or anti-fibrotic factors. Since dysregulation in miR expression has been reported in myocardial fibrosis (Gurha, 2016), miRs may represent a novel therapeutic strategy to counteract the fibrotic changes that occur in cardiac diseases (Wijnen et al., 2013).

Role for the SphK/S1P Axis And S1PR in Cardiac Fibrosis

Many studies performed in cultured cells as well as in animal models have proposed that S1P possesses cardioprotective effects (Kupperman et al., 2000; Jin et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2007; Karliner, 2013; Maceyka and Spiegel, 2014). In fact, S1P protects cultured rat neonatal cardiomyocytes from ischaemia-induced cell death (Karliner et al., 2001; Jin et al., 2002). Moreover, mice lacking the enzyme SPL that degrades S1P show reduced sensitivity to ischaemia/reperfusion injury and increased S1P level in both plasma and cardiac tissue (Jin et al., 2011) (Figure 1).

Regarding cardiac fibrosis, SphK1 appears to play a relevant role. SphK1 is induced by TGF-β and mediates TIMP-1 upregulation, and siRNA against SphK1 inhibited TGF-β-stimulated collagen production (Yamanaka et al., 2004; Gellings Lowe et al., 2009). Importantly, the neutralization of extracellular S1P with a specific anti-S1P antibody significantly reduced TGF-β-stimulated collagen production, indicating the involvement of an “inside-out” signaling of S1P after SphK1 activation in the pro-fibrotic action (Gellings Lowe et al., 2009). Moreover, apelin, an adipocyte-derived factor, inhibits TGF-β-stimulated activation of cardiac fibroblasts by reducing SphK1 activity (Pchejetski et al., 2011).

Notably, high S1P production/accumulation in cells is deleterious. In fact, transgenic mice that overexpressed SphK1 at high level develop spontaneous cardiomyocyte degeneration and fibrosis (Tao et al., 2007; Takuwa et al., 2010) and are characterized by increased levels of Rho GTPases and phospho-Smad3, suggesting that these pathways are downstream of SphK1/S1P.

Recently, we have reported that SL metabolism can be activated by RLX at concentrations similar to those previously reported to elicit specific responses in cardiac muscle cells (van der Westhuizen et al., 2008). In both neonatal cardiac cells and H9C2 cells, RLX induces the activation of SphK1 and S1P production. The silencing and pharmacological inhibition of SphK1 alters the ratio MMPs/TIMPs, and CTGF expression elicited by RLX indicates that hormone peptides promote an ECM-remodeling phenotype through the activation of endogenous S1P production and SM metabolism (Frati et al., 2015).

The role of SphK2 in heart tissue is less clear. Previous research has shown that maternal-zygotic SphK2 is fundamental for cardiac development in zebrafish (Hisano et al., 2015). Moreover, SphK2 knockout sensitizes mouse myocardium to ischaemia/reoxygenation injury (Vessey et al., 2011), and mitochondria obtained from Sphk2 knockout mice exhibit decreased oxidative phosphorylation and increased susceptibility to permeability transition, suggesting a role as protective agent (Gomez et al., 2011). SphK2 appears to be less involved in tissue fibrosis than SphK1 (Schwalm et al., 2015). For example, protein expression of SphK1, but not SphK2, was significantly elevated in lung tissues from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (Huang et al., 2013). Presently, the role of SphK2 in cardiac fibrosis is still unclear. Interestingly, Hait et al. (2009) have found that SphK2 is associated with histone H3, and endogenous S1P that is formed in the nucleus via SphK2 inhibits the action of HDACs (Hait et al., 2009; Ihlefeld et al., 2012). Since HDAC activity is increased in patients with cardiac fibrosis (Liu et al., 2008; Pang and Zhuang, 2010), there is a potential link between SphK2, nuclear S1P and the epigenetic regulation of gene expression that is involved in cardiac fibrosis.

Very recently, a strict correlation between the levels of miRs involved in cardiac fibrosis and SL metabolism has been demonstrated. In fact, SphK, SPT, acid SMase and ceramide synthase 6 (CerS6) can be regulated by several miRs (Figure 1). miR-613 and miR-124 inhibit SphK1 (Yu et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2017). miR-137, miR-181c, miR-9, and miR-29 regulate SPT (Geekiyanage and Chan, 2011). miR-15a modulates acidic SMase (Wang et al., 2015), and miR-101a targets Cer6 (Suzuki et al., 2016) (Figure 1). Interestingly, miR release into exosome particles depends on the ceramide-dependent pathway (Kosaka et al., 2010).

Although the importance of SphK/S1P system has been thoroughly reported, very little is known about the S1P/S1PR axis in the context of cardiac fibrosis. Given that specific anti-S1P antibodies significantly reduce TGF-β-stimulated collagen production by interfering with the binding of exogenous S1P to its specific receptors, a few years ago, the role of “inside-out” S1P signaling in the fibrotic process was proposed (Gellings Lowe et al., 2009). Three of the five S1PRs (S1PR-1, -2, -3) are the major subtypes expressed in the heart (Peters and Alewijnse, 2007; Means and Brown, 2009). Major candidates for the exogenous S1P-mediated control of the fibrotic process are S1PR2 and S1PR3 (Takuwa et al., 2008, 2010, 2013) that preferentially mediate the two following parallel signaling pathways crucially involved in the fibrotic process: Ras homolog GTPase/Rho-associated-protein kinase (Rho/ROCK) and Smad proteins. Particularly, S1PR3 promotes the activation of Rho signaling and the transactivation of TGF-β (Theilmeier et al., 2006; Takuwa et al., 2010). Under chronic activation of SphK1/S1P signaling, S1PR3 mediates pathological cardiac remodeling through ROS production (Takuwa et al., 2010). Moreover, S1PR3-mediated Akt activation protects against in vivo myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion (Means et al., 2007). Characterization of S1PR3-deficient mice also indicates that HDL and S1P promote cardiac protection through nitric oxide/S1PR3 signaling, and exogenous S1P induces intracellular calcium increase through the S1PR3/PLC axis (Theilmeier et al., 2006; Fujii et al., 2014).

Furthermore, S1PR3 can mediate cardioprotection in Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts against ischaemia/reperfusion injury via Rho/NFkB signaling (Yung et al., 2017). Although, S1PR3 is the most prevalent subtype in cardiac fibroblasts (Takuwa et al., 2013), myofibroblast differentiation and collagen production are mainly mediated by S1PR2 signaling (Schwalm et al., 2013). In fact, the silencing of S1PR2, but not of S1PR1 or S1PR3, can block S1P-mediated α-SMA induction (Gellings Lowe et al., 2009), and S1PR2 knock out mice show reduced fibrosis markers expression (Ikeda et al., 2009).

In the heart, the signaling pathways downstream of S1PR1 inhibit cAMP formation and antagonize adrenergic-mediated contractility activation (Means and Brown, 2009). Through S1PR1, S1P induces hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes in vitro (Robert et al., 2001) and decreases vascular permeability (Camerer et al., 2009). In bleomycin-induced injury, S1PR1 functional antagonists increase the pro-fibrotic response (Shea et al., 2010), suggesting an antifibrotic action of S1PR1 in the lung tissue.

There is evidence showing that S1P exhibits cross-talk with pro-fibrotic signaling pathways, such as TGF-β (Xin et al., 2004) and PDGF (Alderton et al., 2001). The involvement of S1PRs in the pro-fibrotic effects that are mediated by the cross-talk between S1P and TGF-β has been demonstrated by inhibition of this effect in primary cardiac fibroblasts by the murine anti-S1P antibody, Sphingomab (Gellings Lowe et al., 2009). Specifically, the role of S1PR3 has been reported in the transactivation of the TGF-β/small GTPases system (Takuwa, 2002; Brown et al., 2006). Evidence has also been provided by a study in which the S1PR1 agonists FTY720 mimicked TGF-β action by promoting the differentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, but failed to act on S1PR3-/- fibroblasts (Keller et al., 2007). Differently from TGF-β, S1P and FTY720-P do not promote Smad signaling to induce ECM synthesis but rather activate PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 (Sobel et al., 2013). Moreover, TGF-β2 stimulates the transactivation of S1PR2 in cardiac fibroblasts, and the silencing of TGF-β receptor II or co-Smad4 reduces the upregulation of CTGF expression induced by FTY720-P in mesangial cells (Xin et al., 2006).

Recently, our group has demonstrated that extracellular S1P inhibits the effects of RLX on MMP-9 release and potentiates hormone action on CTGF expression and TIMP-1 expression through a S1PR subtype-mediated signaling (Frati et al., 2015). Although the action of RLX on S1PRs expression is unknown, a transactivation between S1PRs and the RLX-specific receptor RXFP1 is worthy of investigation (Bathgate et al., 2013).

MicroRNAs can regulate S1PRs in several pathological conditions; for example, S1PR1 expression is upregulated by the deregulation of miR-148a, leading to TGF-β-dependent epithelial-mesenchymal transition (Heo et al., 2014). TNF-α significantly increases S1PR2 expression in human endothelial cells by reducing miR-130a level (Fan et al., 2016). No data are currently available on the role of miRs that are involved in cardiac fibrosis and S1PR expression.

S1PR Modulators in Cardiac Functions

S1PR1 Agonists

Fingolimod (FTY729), synthesized from myriocin, is an immunosuppressive product isolated from Isaria sinclairii and has received approval from the Food and Drug Administration and from the European Medicines Agency as a drug for the treatment of MS (Gilenya, Novartis) (Chun and Hartung, 2010; Chun and Brinkmann, 2011; Cohen and Chun, 2011). The phosphorylated form, phospho-FTY720 (FTY720-P) that is formed by SphK2 in vivo (Brinkmann et al., 2010), is a structural analog of S1P that binds and activates S1PR1-3-4-5, but not S1PR2. Notably, the long-term activation of S1PR1 by FTY720-P determines receptor internalization and degradation, thus acting as a S1PR1 antagonist (Graeler and Goetzl, 2002; Matloubian et al., 2004; Brinkmann et al., 2010; Gonzalez-Cabrera et al., 2012). Due to the binding to various S1PRs, FTY720-P is responsible for several collateral effects on MS patients, such as cardiac effects (bradycardia and atrioventricular block) (Sanna et al., 2004; Camm et al., 2014; Gold et al., 2014). Such effects have been attributed to the activation of S1PR3, and in some cases, to S1PR1. Long-term S1PR1 down-regulation contributes to the disruption of Ca2+ homeostasis and attenuation of ischaemic preconditioning (Keul et al., 2016).

The phosphorylated form of Fingolimod takes part in cardioprotection in heart transplantation related ischaemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury (Santos-Gallego et al., 2016) and acting as potent anti-inflammatory (Aytan et al., 2016) and anti-oxidant agents may lead to reduce myocardial damage as a consequence of reduced cardiomyocytes death.

A new selective S1PR modulator, ceralifimod (ONO-4641), has been recently designed and tested for its ability to limit the cardiovascular complications of Fingolimod (Krösser et al., 2015). Similarly, Amiselimod (MT-1303), a second-generation S1PR modulator, has potent selectivity for S1PR1 and S1PR5 and has almost fivefold weaker GIRK activation (G-protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channel) than FTY720-P (Sugahara et al., 2017). Other interesting compounds that can act on cardiac functions have been reviewed elsewhere (Vachal et al., 2006; Guerrero et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2016) (Table 1). SEW2871 is structurally unrelated to S1P, and its phosphorylation is not required for binding to S1PR1. SEW2871 promotes lymphopenia by reducing inflammatory cells, especially CD4+ T cells (Lien et al., 2006), attenuates kidney ischaemia/reperfusion injury (Lai et al., 2007), and improves cardiac functions following myocardial infarction (Yeh et al., 2009). However, some evidence has indicated that SEW2871 can exacerbate reperfusion arrhythmias (Tsukada et al., 2007). SEW2871 and AUY954, an aminocarboxylate analog of FTY720 (Zhang et al., 2009), directly prevent allograft rejection in rat cardiac transplantation through the regulation of lymphocyte trafficking (Pan et al., 2006). Moreover, AUY954 significantly inhibited expressions of IL-17 and MMP-9 in rat sciatic nerves (Zhang et al., 2009). Repeated AUY954 administration enhanced pulmonary fibrosis by inducing vascular leak (Shea et al., 2010), suggesting caution in the use of this drug. CYM-5442, which binds to S1PR1 in a structural hydrophobic pocket different from Fingolimod (Gonzalez-Cabrera et al., 2008), induces lymphopenia and promotes eNOS activation in endothelial cells, thus playing a role in vascular homeostasis (Tölle et al., 2016). Compound 6d lacks S1PR3 agonism and induces lymphopenia with reduced collateral effects on the heart (Hamada et al., 2010). BAF-312 is a next-generation S1PR modulator, which is selective for S1PR1 and S1PR5 (Fryer et al., 2012), and has species-specific effects on the heart. BAF-312 induces rapid and transient bradycardia in humans through GIRK activation (Gergely et al., 2012). Notably, different doses may be used to limit cardiac effects (Legangneux et al., 2013). KRP-203 reduced chronic rejection and graft vasculopathy in rat skin and heart allografts (Takahashi et al., 2005), and in an experimental autoimmune myocarditis model, it significantly inhibited the infiltration of immune cells into the myocardium, reducing the area of inflammation (Ogawa et al., 2007). Currently, KRP-203 is undergoing a clinical trial for subacute lupus erythaematosus and in patients undergoing stem cell transplantation for hematological malignancies.

S1PR1 antagonists were reported to have therapeutic potential, but their use requires attention. VPC23019, acting as S1PR1 and S1PR3 antagonist, has been used in ischaemic pre- and post-conditioning cardioprotection that is promoted by endogenous S1P in ex vivo rat hearts (Vessey et al., 2009). W-146, which was initially reported to increase the basal leakage of the pulmonary endothelium (Sanna et al., 2006), has been used to demonstrate the role of the S1P pathway in TGF-β1-induced expression of α-SMA in human fetal lung fibroblasts (Kawashima et al., 2012).

S1PR2 Agonists

S1PR2 agonists are mainly used in the treatment of hearing loss (Table 1). A study has shown that CYM-5478 has vascular effects, which is indicated by enhanced ischaemia-reperfusion injury in vivo (Satsu et al., 2013).

S1PR2 Antagonists

JTE-013 was initially reported to affect coronary artery contraction (Ohmori et al., 2003). At long-term S1PR2 antagonism induces several collateral effects, such as a high incidence of B cell lymphoma (Cattoretti et al., 2009).

S1PR3 Antagonists

Selectively blocking S1PR3 is very difficult. For example, VPC25239 antagonizes both S1PR3 and S1PR1, affecting smooth muscle cell functions, whereas VPC01091 leads to neointimal hyperplasia by preferentially blocking S1PR3 (Wamhoff et al., 2008). Other antagonists for S1PR3 are as follows: CAY10444 (or BML-241) (Koide et al., 2002) that can inhibit the prosurvival effect of HDLs after hypoxia-reoxygenation and TY-52156 that suppresses the bradycardia induced by FTY-720 in vivo and promotes vascular contraction (Murakami et al., 2010).

The therapeutic use of monoclonal antibodies can be a valid alternative to synthetic compounds. A monoclonal antibody, 7H9, functionally blocks S1PR3 activation both in vitro and in vivo (Herr, 2012), reduces the growth of breast cancer tumors and prevents systemic inflammation, representing an effective approach against the morbidity of sepsis (Harris et al., 2012). To date, no specific antagonists for S1PR4 and S1PR5 are available, although (S)-FTY720-vinylphosphonate acts as a pan-antagonist that fully antagonizes S1PR1, S1PR3 and S1PR4 and partially antagonizes S1PR2 and S1PR5 (Valentine et al., 2010).

Conclusion

Targeting S1P signaling might be an intriguing new strategy for the treatment of cardiac fibrosis. However, the double face of the “sphinx” should be carefully considered, and the potential of the multiple collateral effects of S1PR modulators should be evaluated with caution.

Author Contributions

EM and LM have partecipated in design the main structure of the minireview and in the revision of literature and in the preparation of the text. AV, FP, and AF have participated in reviewing the literature and writing the manuscript and prepare the figure.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Maria Rita Calabrese for the support in drawing the figure and table.

Abbreviations

- 3KR

3-keto reductase

- AC

adenylate cyclase

- Akt

serine/threonine-specific protein kinase 1

- ApoM

apolipoprotein M

- C1P

ceramide-1-phosphate

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CDase

ceramidase

- Cer

ceramide

- CerK

ceramide kinase

- CerS

ceramide synthase

- CTGF

connective tissue growth factor

- DeS

desaturase

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- Edg-1

endothelial differentiation gene-1

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2

- GIRK

G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptors

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- HDL

high density lipoproteins

- IL

interleukin

- LPA1

lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1

- miR

microRNA

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cell

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PHB2

prohibitin 2

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase

- PLC

phospholipase C

- Rho GTPase

Ras homolog GTP hydrolase

- RLX

relaxin

- ROCK

Rho associated-protein kinase

- RXFP1

relaxin/insulin like family peptide receptor 1

- S1P

sphingosine 1-phosphate

- S1PR

S1P receptor

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

- SL

sphingolipid

- SM

sphingomyelin

- SMA

smooth muscle actin

- Smad

small mother aganist decapentaplegic

- SMase

sphingomyelinase

- SMS

sphingomyelin synthase

- Sph

sphingosine

- SphK

sphingosine kinase

- SPL

S1P lyase

- Spns2

Spinster 2 (S1P transporter)

- SPPase

S1P phosphatases

- SPT

serine palmitoyl transferase

- TGFBR

TGF receptor

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor β

- TIMP

tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TRAF-2

TNF receptor-associated factor 2

- UTR

untranslated region

- Vzg-1

ventricular zone gene-1.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by grants from Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze to EM and MIUR (ex 60% Ateneo 2015) to EM.

References

- Abonnenc M., Nabeebaccus A. A., Mayr U., Barallobre-Barreiro J., Dong X., Cuello F., et al. (2013). Extracellular matrix secretion by cardiac fibroblasts: Role of microRNA-29b and microRNA-30c. Circ. Res. 113 1138-47. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.302400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S. H., Clark L. L., Pennington W. R., Webb C. S., Bonnema D. D., Leonardi A. H., et al. (2006). Matrix metalloproteinases/tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: relationship between changes in proteolytic determinants of matrix composition and structural, functional, and clinical manifestations of hypertensive heart disease. Circulation 113 2089–2096. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.573865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderton F., Rakhit S., Kong K. C., Palmer T., Sambi B., Pyne S., et al. (2001). Tethering of the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor to G-protein-coupled receptors. A novel platform for integrative signaling by these receptor classes in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276 28578–28585. 10.1074/jbc.M102771200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez S. E., Harikumar K. B., Hait N. C., Allegood J., Strub G. M., Kim E. Y., et al. (2010). Sphingosine-1-phosphate is a missing cofactor for the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF2. Nature 465 1084–1088. 10.1038/nature09128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An S., Bleu T., Huang W., Hallmark O. G., Coughlin S. R., Goetzl E. J. (1997). Identification of cDNAs encoding two G protein-coupled receptors for lysosphingolipids. FEBS Lett. 417 279–282. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01301-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An S., Zheng Y., Bleu T. (2000). Sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced cell proliferation, survival, and related signaling events mediated by G protein-coupled receptors Edg3 and Edg5. J. Biol. Chem. 275 288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aytan N., Choi J. K., Carreras I., Brinkmann V., Kowall N. W., Jenkins B. G., et al. (2016). Fingolimod modulates multiple neuroinflammatory markers in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 6:24939 10.1038/srep24939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bani D., Nistri S., Formigli L., Meacci E., Francini F., Zecchi-Orlandini S. (2009). Prominent role of relaxin in improving post infarction heart remodeling. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1160 269–277. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathgate R. A., Halls M. L., van der Westhuizen E. T., Callander G. E., Kocan M., Summers R. J. (2013). Relaxin family peptides and their receptors. Physiol. Rev. 93 405–480. 10.1152/physrev.00001.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont J., López B., Hermida N., Schroen B., San José G., Heymans S., et al. (2014). microRNA-122 down-regulation may play a role in severe myocardial fibrosis in human aortic stenosis through TGF-ß1 up-regulation. Clin. Sci. 126 497-506. 10.1042/CS20130538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo B. C., Gao X. M., Winbanks C. E., Boey E. J., Tham Y. K., Kiriazis H., et al. (2012). Therapeutic inhibition of the miR-34 family attenuates pathological cardiac remodeling and improves heart function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 17615–17620. 10.1073/pnas.1206432109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglino G., Caputo M., Rajakaruna C., Angelini G., van Rooij E., Emanueli C. (2017). Modulating microRNAs in cardiac surgery patients: novel therapeutic opportunities? Pharmacol. Ther. 170 192–204. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaho V. A., Hla T. (2014). An update on the biology of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J. Lipid Res. 55 1596–1608. 10.1194/jlr.R046300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomb R., Heckle M. R., Sun Y., Mancarella S., Guntaka R. V., Gerling I. C., et al. (2016). Myofibroblast secretome and its auto-/paracrine signaling. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 14 591–598. 10.1586/14779072.2016.1147348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V., Billich A., Baumruker T., Heining P., Schmouder R., Francis G., et al. (2010). Fingolimod (FTY720): discovery and development of an oral drug to treat multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9 883–897. 10.1038/nrd3248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. H., Del Re D. P., Sussman M. A. (2006). The Rac and Rho hall of fame: a decade of hypertrophic signaling hits. Circ. Res. 98 730–742. 10.1161/01.RES.0000216039.75913.9e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camerer E., Regard J. B., Cornelissen I., Srinivasan Y., Duong D. N., Palmer D., et al. (2009). Sphingosine-1-phosphate in the plasma compartment regulates basal and inflammation-induced vascular leak in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119 1871–1879. 10.1172/JCI38575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camm J., Hla T., Bakshi R., Brinkmann V. (2014). Cardiac and vascular effects offingolimod: mechanistic basis and clinical implications. Am. Heart J. 168 632–644. 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Care A., Catalucci D., Felicetti F., Bonci D., Addario A., Gallo P., et al. (2007). MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nature Med. 13 613–618. 10.1038/nm1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castoldi G., Di Gioia C. R., Bombardi C., Catalucci D., Corradi B., Gualazzi M. G., et al. (2012). MiR-133a regulates collagen 1A1: potential role of miR-133a in myocardial fibrosis in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. J. Cell. Physiol. 227 850–856. 10.1002/jcp.22939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattoretti G., Mandelbaum J., Lee N., Chaves A. H., Mahler A. M., Chadburn A., et al. (2009). Targeted disruption of the S1P2 sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor gene leads to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma formation. Cancer Res. 69 8686–8692. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Puthanveetil P., Feng B., Matkovich S. J., Dorn G. W., II, Chakrabarti S. (2014). Cardiac miR-133a overexpression prevents early cardiac fibrosis in diabetes. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 18 415–421. 10.1111/jcmm.12218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen C., Obinata H., Kumaraswamy S. B., Galvani S., Ahnström J., Sevvana M., et al. (2011). Endothelium-protective sphingosine-1-phosphate provided by HDL-associated apolipoprotein M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 9613–9618. 10.1073/pnas.1103187108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J., Brinkmann V. (2011). A mechanistically novel, first oral therapy for multiple sclerosis: the development of fingolimod (FTY720, Gilenya). Discov. Med. 12 213–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J., Hartung H. P. (2010). Mechanism of action of oral fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 33 91–101. 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181cbf825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A., Chun J. (2011). Mechanisms of fingolimod’s efficacy and adverse effects in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 69 759–777. 10.1002/ana.22426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn J. N., Ferrari R., Sharpe N. (2000). Cardiac remodeling-concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an international forum on cardiac remodeling. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 35 569–582. 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00630-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creemers E. E., Pinto Y. M. (2011). Molecular mechanisms that control interstitial fibrosis in the pressure-overloaded heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 89 265–272. 10.1093/cvr/cvq308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creemers E. E., van Rooij E. (2016). Function and therapeutic potential of noncoding RNAs in cardiac fibrosis. Circ. Res. 118 108–118. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.305242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J., Molkentin J. D. (2014). Myofibroblasts: trust your heart and let fate decide. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 70 9–18. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S., Ma W., Hao B., Hu F., Yan L., Yan X., et al. (2014). MicroRNA-21 promotes cardiac fibrosis and development of heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction by up-regulating Bcl-2. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 7 565–574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X. J., Bathgate R. A., Samuel C. S., Dart A. M., Summers R. J. (2010). Cardiovascular effects of relaxin: from basic science to clinical therapy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 7 48–58. 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W., Liang H., Gao X., Li X., Zhang Y., Pan Z., et al. (2016). MicroRNA-328, a potential anti-fibrotic target in cardiac interstitial fibrosis. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 39 827–836. 10.1159/000447793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duisters R. F., Tijsen A. J., Schroen B., Leenders J. J., Lentink V., van der Made I., et al. (2009). miR-133 and miR-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: implications for a role of microRNAs in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ. Res. 104 170–178. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan A., Wang Q., Yuan Y., Cheng J., Chen L., Guo X., et al. (2016). Liver X receptor-α and miR-130a-3p regulate expression of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 2 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 310 C216–C226. 10.1152/ajpcell.00102.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B., Cao Y., Chen S., Chu X., Chu Y., Chakrabarti S. (2016). miR-200b mediates endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 65 768–779. 10.2337/db15-1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frati A., Ricci B., Pierucci F., Nistri S., Bani D., Meacci E. (2015). Role of sphingosine kinase/S1P axis in ECM remodeling of cardiac cells elicited by relaxin. Mol. Endocrinol. 29 53–67. 10.1210/me.2014-1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer R. M., Muthukumarana A., Harrison P. C., Nodop Mazurek S., Chen R. R., Harrington K. E., et al. (2012). The clinically-tested S1P receptor agonists, FTY720 and BAF312, demonstrate subtype-specific bradycardia (S1P1) and hypertension (S1P3) in rat. PLoS ONE 7:e52985 10.1371/journal.pone.0052985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii K., Machida T., Iizuka K., Hirafuji M. (2014). Sphingosine 1-phosphate increases an intracellular Ca2+ concentration via S1P3 receptor in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 66 802–810. 10.1111/jphp.12214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geekiyanage H., Chan C. (2011). MicroRNA-137/181c regulates serine palmitoyltransferase and in turn amyloid beta, novel targets in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 31 14820–14830. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3883-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellings Lowe N. G., Swaney J. S., Moreno K. M., Sabbadini R. A. (2009). Sphingosine-1-phosphate and sphingosine kinase are critical for TGF-β-stimulated collagen production by cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc. Res. 82 303–312. 10.1093/cvr/cvp056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergely P., Nuesslein-Hildesheim B., Guerini D., Brinkmann V., Traebert M., Bruns C., et al. (2012). The selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator BAF312 redirects lymphocyte distribution and has species-specific effects on heart rate. Br. J. Pharmacol. 167 1035–1047. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02061.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzl E. J., Dolezalova H., Kong Y., Hu Y. L., Jaffe R. B., Kalli K. R., et al. (1999). Distinctive expression and functions of the type 4 endothelial differentiation gene-encoded G protein-coupled receptor for lysophosphatidic acid in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 59 5370–5375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold R., Comi G., Palace J., Siever A., Gottschalk R., Bijarnia M., et al. (2014). Assessment of cardiac safety during fingolimod treatment initiation in a real-world relapsing multiple sclerosis population: a phase 3b, open-label study. J. Neurol. 261 267–276. 10.1007/s00415-013-7115-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez L., Paillard M., Price M., Chen Q., Teixeira G., Spiegel S., et al. (2011). A novel role for mitochondrial sphingosine-1-phosphate produced by, sphingosine kinase-2, in PTP-mediated cell survival during cardioprotection. Basic Res. Cardiol. 106 1341–1353. 10.1007/s00395-011-0223-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Cabrera P. J., Cahalan S. M., Nguyen N., Sarkisyan G., Leaf N. B., Cameron M. D., et al. (2012). S1P(1) receptor modulation with cyclical recovery from lymphopenia ameliorates mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Mol. Pharmacol. 81 166–174. 10.1124/mol.111.076109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Cabrera P. J., Jo E., Sanna M. G., Brown S., Leaf N., Marsolais D., et al. (2008). Full pharmacological efficacy of a novel S1P1 agonist that does not require S1P-like headgroup interactions. Mol. Pharmacol. 74 1308–1318. 10.1124/mol.108.049783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeler M., Goetzl E. J. (2002). Activation-regulated expression and chemotactic function of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors in mouse splenic T cells. FASEB J. 16 1874–1878. 10.1096/fj.02-0548com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gräler M. H., Bernhardt G., Lipp M. (1998). EDG6, a novel G-protein-coupled receptor related to receptors for bioactive lysophospholipids, is specifically expressed in lymphoid tissue. Genomics 53 164–169. 10.1006/geno.1998.5491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero M., Urbano M., Roberts E. (2016). Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 agonists: a patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 26 455–470. 10.1517/13543776.2016.1157165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurha P. (2016). MicroRNAs in cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 31 249–254. 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyöngyösi M., Winkler J., Ramos I., Do Q. T., Firat H., McDonald K., et al. (2017). Myocardial fibrosis: biomedical research from bench to bedside. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 19 177–191. 10.1002/ejhf.696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hait N. C., Allegood J., Maceyka M., Strub G. M., Harikumar K. B., Singh S. K., et al. (2009). Regulation of histone acetylation in the nucleus by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Science 325 1254–1257. 10.1126/science.1176709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada M., Nakamura M., Kiuchi M., Marukawa K., Tomatsu A., Shimano K., et al. (2010). Removal of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-3 (S1P3) agonism is essential, but inadequate to obtain immunomodulating 2-aminopropane-1,3-diol S1P1 agonists with reduced effect on heart rate. J. Med. Chem. 53 3154–3168. 10.1021/jm901776q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannun Y. A., Obeid L. M. (2008). Principles of bioactive lipid signaling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9 139–150. 10.1038/nrm2329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson M. A., Roth C. B., Jo E., Griffith M. T., Scott F. L., Reinhart G., et al. (2012). Crystal structure of a lipid G protein-coupled receptor. Science 335 851–855. 10.1126/science.1215904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris G. L., Creason M. B., Brulte G. B., Herr D. R. (2012). In vitro and in vivo antagonism of a G protein-coupled receptor (S1P3) with a novel blocking monoclonal antibody. PLoS ONE 7:e35129 10.1371/journal.pone.0035129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Zhang K., Gao X., Li L., Tan H., Chen J., et al. (2016). Rapid atrial pacing induces myocardial fibrosis by down-regulating Smad7 via microRNA-21 in rabbit. Heart Vessels 31 1696–1708. 10.1007/s00380-016-0808-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo M. J., Kim Y. M., Koo J. H., Yang Y. M., An J., Lee S. K., et al. (2014). microRNA-148a dysregulation discriminates poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in association with USP4 overexpression. Oncotarget 5 2792–2806. 10.18632/oncotarget.1920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr D. R. (2012). Potential use of G protein-coupled receptor-blocking monoclonal antibodies as therapeutic agents for cancers. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 297 45–81. 10.1016/B978-0-12-394308-8.00002-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymans S., Schroen B., Vermeersch P., Milting H., Gao F., Kassner A., et al. (2005). Increased cardiac expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 is related to cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction in the chronic pressure-overloaded human heart. Circulation 112 1136–1144. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.516963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisano Y., Inoue A., Okudaira M., Taimatsu K., Matsumoto H., Kotani H., et al. (2015). Maternal and zygotic sphingosine kinase 2 are indispensable for cardiac development in zebrafish. J. Biol. Chem. 290 14841–14851. 10.1074/jbc.M114.634717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hla T., Maciag T. (1990). An abundant transcript induced in differentiating human endothelial cells encodes a polypeptide with structural similarities to G-protein-coupled receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 265 9308–9313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y., Cao H., Wang Q., Ye J., Sui L., Feng J., et al. (2016). MiR-22 may suppress fibrogenesis by targeting TGFβR I in cardiac fibroblasts. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 40 1345–1353. 10.1159/000453187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L. S., Berdyshev E., Mathew B., Fu P., Gorshkova I. A., He D., et al. (2013). Targeting sphingosine kinase 1 attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. FASEB J. 27 1749–1760. 10.1096/fj.12-219634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Qi Y., Du J. Q., Zhang D. F. (2014). MicroRNA-34a regulates cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction by targeting Smad4. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 18 1355–1365. 10.1517/14728222.2014.961424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihlefeld K., Claas R. F., Koch A., Pfeilschifter J. M., Zu Heringdorf D. M. (2012). Evidence for a link between histone deacetylation and Ca2+ homoeostasis in sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase-deficient fibroblasts. Biochem. J. 447 457–464. 10.1042/BJ20120811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H., Watanabe N., Ishii I., Shimosawa T., Kume Y., Tomiya T., et al. (2009). Sphingosine 1-phosphate regulates regeneration and fibrosis after liver injury via sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 2. J. Lipid Res. 50 556–564. 10.1194/jlr.M800496-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im D. S., Clemens J., Macdonald T. L., Lynch K. R. (2001). Characterization of the human and mouse sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor, S1P5 (Edg-8): structure-activity relationship of sphingosine1-phosphate receptors. Biochemistry 40 14053–14060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii I., Friedman B., Ye X., Kawamura S., McGiffert C., Contos J. J., et al. (2001). Selective loss of sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling with no obvious phenotypic abnormality in mice lacking its G protein-coupled receptor, LP(B3)/EDG-3. J. Biol. Chem. 276 33697–33704. 10.1074/jbc.M104441200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z. Q., Fyrst H., Zhang M., Borowsky A. D., Dillard L., Karliner J. S., et al. (2011). S1P lyase: a novel therapeutic target for ischemia-reperfusion injury of the heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 300 H1753–H1761. 10.1152/ajpheart.00946.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z. Q., Zhou H. Z., Zhu P., Honbo N., Mochly-Rosen D., Messing R. O., et al. (2002). Cardioprotection mediated by sphingosine-1-phosphate and ganglioside GM-1 in wild-type and PKC epsilon knockout mouse hearts. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 282 H1970–H1977. 10.1152/ajpheart.01029.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karliner J. S. (2013). Sphingosine kinase and sphingosine 1-phosphate in the heart: a decade of progress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1831 203–212. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karliner S., Honbo N., Summers K., Gray M. O., Goetzl E. J. (2001). The lysophospholipids sphingosine-1-phosphate and lysophosphatidic acid enhance survival during hypoxia in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 33 1713–1717. 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima T., Yamazaki R., Matsuzawa Y., Yamaura E., Takabatake M., Otake S., et al. (2012). Contrary effects of sphingosine-1-phosphate on expression of α-smooth muscle actin in transforming growth factor β1-stimulated lung fibroblasts. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 696 120–129. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C. D., Rivera Gil P., Tölle M., van der Giet M., Chun J., Radeke H. H., et al. (2007). Immunomodulator FTY720 induces myofibroblast differentiation via the lysophospholipid receptor S1P3 and Smad3 signaling. Am. J. Pathol. 170 281–229. 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keul P., van Borren M. M., Ghanem A., Muller F. U., Baartscheer A., Verkerk A. O., et al. (2016). Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 regulates cardiacfunction by modulating Ca2+ sensitivity and Na+/H+ exchange and mediates protection by ischemic preconditioning. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 5:e003393 10.1161/JAHA.116.003393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara Y., Maceyka M., Spiegel S., Chun J. (2014). Lysophospholipid receptor nomenclature review: IUPHAR review 8. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171 3575–3594. 10.1111/bph.12678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide Y., Hasegawa T., Takahashi A., Endo A., Mochizuki N., Nakagawa M., et al. (2002). Development of novel EDG3 antagonists using a 3D database search and their structure-activity relationships. J. Med. Chem. 45 4629–4638. 10.1021/jm020080c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong P., Christia P., Frangogiannis N. (2014). The pathogenesis of cardiac Fibrosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71 549–574. 10.1007/s00018-013-1349-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono M., Mi Y., Liu Y., Sasaki T., Allende M. L., Wu Y. P., et al. (2004). The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors S1P1, S1P2, and S1P3 function coordinately during embryonic angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279 29367–29373. 10.1074/jbc.M403937200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka N., Iguchi H., Yoshioka Y., Takeshita F., Matsuki Y., Ochiya T. (2010). Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285 17442–17452. 10.1074/jbc.M110.107821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenning G., Zeisberg E. M., Kalluri R. (2010). The origin of fibroblasts and mechanism of cardiac fibrosis. J. Cell. Physiol. 225 631–637. 10.1002/jcp.22322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krösser S., Wolna P., Fischer T. Z., Boschert U., Stoltz R., Zhou M., et al. (2015). Effect of ceralifimod (ONO-4641) on lymphocytes and cardiac function: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with an open-label fingolimod arm. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 55 1051–1060. 10.1002/jcph.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel G. T., Maceyka M., Milstien S., Spiegel S. (2013). Targeting the sphingosine-1-phosphate axis in cancer, inflammation and beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12 688–702. 10.1038/nrd4099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupperman E., An S., Osborne N., Waldron S., Stainier D. Y. (2000). A sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor regulates cell migration during vertebrate heart development. Nature 406 192–195. 10.1038/35018092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L. W., Yong K. C., Igarashi S., Lien Y. H. (2007). A sphingosine-1-phosphate type 1 receptor agonist inhibits the early T-cell transient following renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 71 1223–1231. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajiness J. D., Conway S. J. (2014). Origin, development, and differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 70 2–8. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A. (2010). Potential therapeutic targets for cardiac fibrosis: TGFbeta, angiotensin, endothelin, CCN2, and PDGF, partners in fibroblast activation. Circ. Res. 106 1675–1680. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legangneux E., Gardin A., Johns D. (2013). Dose titration of BAF312 attenuates the initial heart rate reducing effect in healthy subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 75 831–841. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04400.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Dai Y., Su Z., Wei G. (2016). MicroRNA-9 inhibits high glucose-induced proliferation, differentiation and collagen accumulation of cardiac fibroblasts by down-regulation of TGFBR2. Biosci. Rep. 36 e00417 10.1042/BSR20160346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Liang H., Zhang C., Ban T., Liu Y., Mei L., Piao X., et al. (2012). A novel reciprocal loop between microRNA-21 and TGFbetaRIII is involved in cardiac fibrosis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 44 2152–2160. 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lien Y. H., Yong K. C., Cho C., Igarashi S., Lai L. W. (2006). S1P(1)-selective agonist, SEW2871, ameliorates ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 69 1601–1608. 10.1038/sj.ki.5000360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Levin M. D., Petrenko N. B., Lu M. M., Wang T., Yuan L. J., et al. (2008). Histone-deacetylase inhibition reverses atrial arrhythmia inducibility and fibrosis in cardiac hypertrophy independent of angiotensin. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 45 715–723. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Toman R. E., Goparaju S. K., Maceyka M., Nava V. E., Sankala H., et al. (2003). Sphingosine kinase type 2 is a putative BH3-only protein that induces apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 278 40330–40336. 10.1074/jbc.M304455200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wada R., Yamashita T., Mi Y., Deng C. X., Hobson J. P., et al. (2000). Edg-1, the G protein-coupled receptor for sphingosine-1-phosphate, is essential for vascular maturation. J. Clin. Invest. 106 951–961. 10.1172/JCI10905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maceyka M., Harikumar K. B., Milstien S., Spiegel S. (2012). Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling and its role in disease. Trends Cell Biol. 22 50–60. 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maceyka M., Spiegel S. (2014). Sphingolipid metabolites in inflammatory disease. Nature 510 58–67. 10.1038/nature13475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloubian M., Lo C. G., Cinamon G., Lesneski M. J., Xu Y., Brinkmann V., et al. (2004). Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature 427 355–356. 10.1038/nature02284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means C. K., Brown J. H. (2009). Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor signaling in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 82 193–200. 10.1093/cvr/cvp086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means C. K., Xiao C. Y., Li Z., Zhang T., Omens J. H., Ishii I., et al. (2007). Sphingosine 1-phosphate S1P2 and S1P3 receptor-mediated Akt activation protects against in vivo myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292 H2944–H2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra P. K., Givvimani S., Chavali V., Tyagi S. C. (2013). Cardiac matrix: a clue for future therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1832 2271–2276. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra P. K., Metreveli N., Tyagi S. C. (2010). MMP-9 gene ablation and TIMP-4 mitigate PAR-1-mediated cardiomyocyte dysfunction: a plausible role of dicer and miRNA. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 57 67–76. 10.1007/s12013-010-9084-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshal K. S., Tyagi N., Moss V., Henderson B., Steed M., Ovechkin A., et al. (2005). Early induction of matrix metalloproteinase-9 transduces signaling in human heart end stage failure. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 9 704–713. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00501.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami A., Takasugi H., Ohnuma S., Koide Y., Sakurai A., Takeda S., et al. (2010). Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) regulates vascular contraction via S1P3 receptor: investigation based on a new S1P3 receptor antagonist. Mol. Pharmacol. 77 704–713. 10.1124/mol.109.061481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraoka N., Yamakawa H., Miyamoto K., Sadahiro T., Umei T., Isomi M., et al. (2014). MiR-133 promotes cardiac reprogramming by directly repressing Snai1 and silencing fibroblast signatures. EMBO J. 33 1565–1581. 10.15252/embj.201387605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H., Visse R., Murphy G. (2006). Structure and function of matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs. Cardiovasc. Res. 69 562–573. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton J., Lima S., Maceyka M., Spiegel S. (2015). Revisiting the sphingolipid rheostat: evolving concepts in cancer therapy. Exp. Cell Res. 333 195–200. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi T., Kobayashi N., Hisano Y., Kawahara A., Yamaguchi A. (2014). Molecular and physiological functions of sphingosine 1-phosphate transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1841 759–765. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nistri S., Pini A., Sassoli C., Squecco R., Francini F., Formigli L., et al. (2012). Relaxin promotes growth and maturation of mouse neonatal cardiomyocytes in vitro: clues for cardiac regeneration. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 16 507–519. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01328.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa R., Takahashi M., Hirose S., Morimoto H., Ise H., Murakami T., et al. (2007). A novel sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist KRP-203 attenuates rat autoimmune myocarditis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 361 621–628. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmori T., Yatomi Y., Osada M., Kazama F., Takafuta T., Ikeda H., et al. (2003). Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces contraction of coronary artery smooth muscle cells via S1P2. Cardiovasc. Res. 58 170–177. 10.1016/S0008-6363(03)00260-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera A., Allende M. L., Proia R. L. (2013). Shaping the landscape: metabolic regulation of S1P gradients. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1831 193–202. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S., Mi Y., Pally C., Beerli C., Chen A., Guerini D., et al. (2006). A monoselective sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1 agonist prevents allograft rejection in a stringent rat heart transplantation model. Chem. Biol. 13 1227–1234. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z., Sun X., Shan H., Wang N., Wang J., Ren J., et al. (2012). MicroRNA-101 inhibited postinfarct cardiac fibrosis and improved left ventricular compliance via the FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene/transforming growth factor-beta1 pathway. Circulation 126 840–850. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.094524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang M., Zhuang S. (2010). Histone deacetylase: a potential therapeutic target for fibrotic disorders. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 335 266–272. 10.1124/jpet.110.168385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker T. G., Schneider M. D. (1991). Growth factors, proto-oncogenes, and plasticity of the cardiac phenotype. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 53 179–200. 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.001143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pchejetski D., Foussal C., Alfarano C., Lairez O., Calise D., Guilbeau-Frugier C., et al. (2011). Apelin prevents cardiac fibroblast activation and collagen production through inhibition of sphingosine kinase 1. Eur. Heart J. 33 2360–2369. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters S. L., Alewijnse A. E. (2007). Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling in the cardiovascular system. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 7 186–192. 10.1016/j.coph.2006.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter K. E., Turner N. A. (2009). Cardiac fibroblasts: at the heart of myocardial remodeling. Pharmacol. Ther. 123 255–278. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proia R. L., Hla T. (2015). Emerging biology of sphingosine-1-phosphate: its role in pathogenesis and therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 125 1379–1387. 10.1172/JCI76369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne N. J., McNaughton M., Boomkamp S., MacRitchie N., Evangelisti C., Martelli A. M., et al. (2015). Role of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors, sphingosine kinases and sphingosine in cancer and inflammation. Adv. Biol. Regul. 60 151–159. 10.1016/j.jbior.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert P., Tsui P., Laville M. P., Livi G. P., Sarau H. M., Bril A., et al. (2001). EDG1 receptor stimulation leads to cardiac hypertrophy in rat neonatal myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 33 1589–1606. 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H., Stevens R. C., Hanson M., Roberts E., Oldstone M. B. (2013). Sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptors: structure, signaling, and influence. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82 637–662. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062411-130916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz S. (2004). TGF-β1 and angiotensin networking in cardiac remodelling. Cardiovasc. Res. 63 423–432. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S., Khanna S., Hussain S. R., Biswas S., Azad A., Rink C., et al. (2009). MicroRNA expression in response to murine myocardial infarction: miR-21 regulates fibroblast metalloprotease-2 via phosphatase and tensin homologue. Cardiovasc. Res. 82 21–29. 10.1093/cvr/cvp015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel C. S., Lekgabe E. D., Mookerjee I. (2007). The effects of relaxin on extracellular matrix remodeling in health and fibrotic disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 612 8–103. 10.1007/978-0-387-74672-2_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna M. G., Liao J., Jo E., Alfonso C., Ahn M. Y., Peterson M. S., et al. (2004). Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor subtypes S1P1 and S1P3, respectively, regulate lymphocyte recirculation and heart rate. J. Biol. Chem. 279 13839–13848. 10.1074/jbc.M311743200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna M. G., Wang S. K., Gonzalez-Cabrera P. J., Don A., Marsolais D., Matheu M. P., et al. (2006). Enhancement of capillary leakage and restoration of lymphocyte egress by a chiral S1P1 antagonist in vivo. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2 434–441. 10.1038/nchembio804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Gallego C. G., Vahl T. P., Goliasch G., Picatoste B., Arias T., Ishikawa K., et al. (2016). Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist fingolimod increases myocardial salvage, and decreases adverse postinfarction left ventricular remodeling in a porcine model of ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation 133 954–966. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.012427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satsu H., Schaeffer M. T., Guerrero M., Saldana A., Eberhart C., Hodder P., et al. (2013). A sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 2 selective allosteric agonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21 5373–5382. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze T., Golfier S., Tabeling C., Räbel K., Gräler M. H., Witzenrath, et al. (2011). Sphingosine-1-phospate receptor 4 (S1P4) deficiency profoundly affects dendritic cell function and TH17-cell differentiation in a murine model. FASEB J. 25 4024–4036. 10.1096/fj.10-179028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalm S., Pfeilschifter J., Huwiler A. (2013). Sphingosine-1-phosphate: a Janus-faced mediator of fibrotic diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1831 239–250. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalm S., Timcheva T. M., Filipenko I., Ebadi M., Hofmann L. P., Zangemeister-Wittke U., et al. (2015). Sphingosine kinase 2 deficiency increases proliferation and migration of renal mouse mesangial cells and fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 396 813–825. 10.1515/hsz-2014-0289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea B. S., Brooks S. F., Fontaine B. A., Chun J., Luster A. D., Tager A. M. (2010). Prolonged exposure to sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 agonists exacerbates vascular leak, fibrosis, and mortality after lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 43 662–673. 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0345OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel K., Menyhart K., Killer N., Renault B., Bauer Y., Studer R., et al. (2013). Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor agonists mediate pro-fibrotic responses in normal human lung fibroblasts via S1P2 and S1P3 receptors and smad-independent signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 288 14839–14851. 10.1074/jbc.M112.426726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinale F. G. (2007). Myocardial matrix remodeling and the matrix metalloproteinases: influence on cardiac form and function. Physiol. Rev. 87 1285–1342. 10.1152/physrev.00012.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinale F. G., Janicki J. S., Zile M. R. (2013). Membrane-associated matrix proteolysis and heart failure. Circ. Res. 112 195–208. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.266882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugahara K., Maeda Y., Shimano K., Mogami A., Kataoka H., Ogawa K., et al. (2017). Amiselimod, a novel sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 modulator, has potent therapeutic efficacy for autoimmune diseases, with low bradycardia risk. Br. J. Pharmacol. 174 15–27. 10.1111/bph.13641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M., Cao K., Kato S., Komizu Y., Mizutani N., Tanaka K., et al. (2016). Targeting ceramide synthase 6 dependent metastasis-prone phenotype in lung cancer cells. J. Clin. Invest. 126 254–265. 10.1172/JCI79775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Takahashi M., Shimizu H., Murakami T., Enosawa S., Suzuki C., Takeno Y., et al. (2005). A novel immunomodulator KRP-203 combined with cyclosporine prolonged graft survival and abrogated transplant vasculopathy in rat heart allografts. Transplant. Proc. 37 143–145. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.12.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuwa N., Ohkura S., Takashima S., Ohtani K., Okamoto Y., Tanaka T., et al. (2010). S1P3-mediated cardiac fibrosis in sphingosine kinase 1 transgenic mice involves reactive oxygen species. Cardiovasc. Res. 85 484–493. 10.1093/cvr/cvp312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuwa Y. (2002). Subtype-specific differential regulation of Rho family G proteins and cell migration by the Edg family, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1582 112–120. 10.1016/S1388-1981(02)00145-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuwa Y., Ikeda H., Okamoto Y., Takuwa N., Yoshioka K. (2013). Sphingosine-1-phosphate as a mediator involved in development of fibrotic diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1831 185–192. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuwa Y., Okamoto Y., Yoshioka K., Takuwa N. (2008). Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling and biological activities in the cardiovascular system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1781 483–488. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.04.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R., Zhang J., Vessey D. A., Honbo N., Karliner J. S. (2007). Deletion of the sphingosine kinase-1 gene influences cell fate during hypoxia and glucose deprivation in adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 74 56–63. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theilmeier G., Schmidt C., Herrmann J., Keul P., Schäfers M., Herrgott I., et al. (2006). High-density lipoproteins and their constituent, sphingosine-1-phosphate, directly protect the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo via the S1P3 lysophospholipid receptor. Circulation 114 1403–1409. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thudichum J. L. W. (1884). A Treatise on the Chemical Constitution of Brain. London: Bailliere, Tindall and Cox, 338. [Google Scholar]

- Thum T., Gross C., Fiedler J., Fischer T., Kissler S., Bussen M., et al. (2008). MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signaling in fibroblasts. Nature 456 980–984. 10.1038/nature07511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijsen A. J., van der Made I., van den Hoogenhof M. M., Wijnen W. J., van Deel E. D., de Groot N. E., et al. (2014). The microRNA-15 family inhibits the TGFβ-pathway in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 104 61–71. 10.1093/cvr/cvu184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tölle M., Klöckl L., Wiedon A., Zidek W., van der Giet M., Schuchardt M. (2016). Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation in endothelial cells by S1P1 and S1P3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 476 627–634. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasek J. J., Gabbiani G., Hinz B., Chaponnier C., Brown R. A. (2002). Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3 349–363. 10.1038/nrm809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada Y. T., Sanna M. G., Rosen H., Gottlieb R. A. (2007). S1P1-selective agonist SEW2871 exacerbates reperfusion arrhythmias. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 50 660–669. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.01.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruda T., Costello-Boerrigter L. C., Burnett J. C., Jr. (2004). Matrix metalloproteinases: pathways of induction by bioactive molecules. Heart Fail. Rev. 9 53–61. 10.1023/B:HREV.0000011394.34355.bb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi S. C., Ratajska A., Weber K. T. (1993). Myocardial matrix metalloproteinase(s): localization and activation. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 126 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachal P., Toth L. M., Hale J. J., Yan L., Mills S. G., Chrebet G. L., et al. (2006). Highly selective and potent agonists of sphingosine-1-phosphate 1 (S1P1) receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16 3684–3687. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine W. J., Kiss G. N., Liu J. E. S., Gotoh M., Murakami-Murofushi K., Pham T. C., et al. (2010). (S)-FTY720-vinylphosphonate, an analogue of the immunosuppressive agent FTY720 is a pan-antagonist of sphingosine 1-phosphate GPCR signaling and inhibits autotaxin activity. Cell. Signal. 22 1543–1553. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Borne S. W., Diez J., Blankesteijn W. M., Verjans J., Hofstra L., Narula J. (2010). Remodeling after infarction: the role of myofibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 7 30–37. 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Westhuizen E. T., Halls M. L., Samuel C. S., Bathgate R. A., Unemori E. N., Sutton S. W., et al. (2008). Relaxin family peptide receptors–from orphans to therapeutic targets. Drug Discov. Today 13 640–651. 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rooij E., Sutherland L. B., Thatcher J. E., DiMaio J. M., Naseem R. H., Marshall W. S., et al. (2008). Dysregulation of microRNAs after myocardial infarction reveals a role of miR-29 in cardiac fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 13027–13032. 10.1073/pnas.0805038105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte D., Heymans S. (2010). TIMPs and cardiac remodeling: ‘embracing the MMP-independent-side of the family’. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 48 445–453. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessey D. A., Li L., Honbo N., Karliner J. S. (2009). Sphingosine 1-phosphate is an important endogenous cardioprotectant released by ischemic pre- and postconditioning. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297 H1429–H1435. 10.1152/ajpheart.00358.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]