Abstract

An animal's decision to enter into a fight depends on the interaction between perceived resource value (V) and fighting costs (C). Both could be altered by predictable environmental fluctuations. For intertidal marine animals, such as the sea anemone Actinia equina, exposure to high flow during the tidal cycle may increase V by bringing more food. It may also increase C via energy expenditure needed to attach to the substrate. We asked whether simulated tidal cycles would alter decisions in fighting A. equina. We exposed some individuals to still water and others to simulated tidal cycles. To gain insights into V, we measured their startle responses before and after exposure to the treatments, before staging dyadic fights. Individuals exposed to flow present shorter startle responses, suggesting that flowing water indicates high V compared with still water. A higher probability of winning against no-flow individuals and longer contests between flow individuals suggests that increased V increases persistence. However, encounters between flow individuals were less likely to escalate, suggesting that C is not directly related to V. Therefore, predictable environmental cycles alter V and C, but in complex ways.

Keywords: animal contests, contest costs, environmental cues, predictable cycles

1. Introduction

The initial hawk–dove model [1] and its subsequent developments (e.g. [2,3]) use two key variables to explain why animals might choose to fight: the value placed on the contested resource (V) and the cost of fighting (C). Thus, there has been substantial empirical focus on the effects of V and C on strategic decisions during contests. Most tests of contest theory involve staged encounters under stable laboratory environments. By contrast, information on how environmental conditions might influence V and C is lacking [4]. Given that fighting behaviour has evolved in fluctuating natural environments, rather than under stable laboratory conditions, this is an important omission. Therefore, studies focusing on the effects of fluctuating abiotic features of the environment could give new insights into the functions of agonistic behaviour.

There are several routes through which environmental conditions could influence animal contests by altering V and C. Weather stability may affect V by constraining or relaxing the reproductive period, thus affecting the value of territories [5]. Weather may also play a role in aerial contests: wind velocity can increase C through drag or convective cooling effects [6], and sunlight may increase territory V [7]. Furthermore, lunar cycles are known to alter mammal activity, and may thus affect C by making fighting individuals more conspicuous to predators [8]. On heterogeneous rocky shores, structural features may alter the strength of currents across the same shore. Strong currents could increase the risk of dislodgement of sessile animals such that they would need to allocate more energy to tenacity. This could increase the relative C if more energy is needed to maintain attachment to the rocky surface, both during routine activity and during fights. If animals have to pay more to stay attached, then less energy will be available for aggressive behaviours and, equally, any energy expended on fighting will be lost to tenacity [9]. However, intertidal currents could also alter V. For sedentary animals, tidal currents bring food particles into their capture space. Fighting animals might, therefore, place greater value on territories that are associated with high flow and hence high rates of food supply. Thus, variation in tidal currents could influence both V and C, potentially in opposite directions.

The effects on V and C may alter motivational state [10] and contest dynamics [11,12]. If perceived V is higher for one opponent, this individual should have an increased chance of victory. When V is high for both opponents, we should see lengthier and more aggressive contests. By contrast, high costs should have the opposite effect: reducing the chance of victory for the individual with higher C, while also reducing contest duration and escalation. V and C might thus interact. To disentangle this interaction, we need to manipulate the environmental variable of interest independently for each individual in the contest. Beadlet sea anemones, Actinia equina, show startle responses, which can be used to probe V, and readily fight for territories on the rocky intertidal [13]. They use specialized fighting tentacles, the acrorhagi, to damage opponents during fights (increasing C [14]), but some fights are resolved without stinging. Thus, A. equina is an ideal system for studying the influence of environmental fluctuations on fighting.

Here, we use an orthogonal design to investigate contests between pairs of focal and opponent anemones that have been exposed to either still or flowing seawater (with flow pattern arranged to mimic the tidal cycle). We first use startle response duration to assess the effect of flow rate on V. If high flow increases the perceived value of territory, anemones held under this condition should show shorter startle responses (prior to staged fights) than those held in still water. In subsequent fights, if high flow only increases V, individuals that experienced this should then be more likely to defeat individuals held in still water, and contest duration and intensity should increase when both individuals have experienced flowing seawater. If high flow only increases C, individuals that experienced high flow should be less likely to defeat individuals held in still water, and contest duration and intensity should decrease when both individuals have experienced flowing seawater.

2. Material and methods

(a). Collection, experimental treatment and startle responses

We collected 140 A. equina on the upper shore of Portwrinkle beach, Cornwall, UK and transported them to the laboratory. We housed all anemones within a large circular aquarium (diameter = 100 cm) filled with aerated seawater. Within this aquarium, we kept anemones individually in rectangular enclosures (36 cm²) made with mesh (0.325 cm²) to allow water flow during the entire experiment. We subdivided the circular aquarium (electronic supplementary material, figure S1a) into two parts, an outer zone (N = 70) and an inner zone (N = 70), by a solid PVC wall. This wall ensured that flow in the outer zone would not affect the water in the inner zone. We acclimated the anemones for 3 days before we started the experiment. Feeding schedules can be seen in the electronic supplementary material, figure S1b.

We simulated tidal cycles for the individuals in the outer zone only. We attached five reef pumps to the side of the aquarium equidistantly (flow speed: 7.8 ± 1.4 cm s−1; electronic supplementary material, figure S1a). We left the water flowing for 5 h (incoming tide), turned the pumps off for 2 h (slack water), reversed the direction of the pumps and left the pumps on for 5 h (outgoing tide; electronic supplementary material, figure S1c). We repeated this process, simulating a full day of the tidal cycle. The individuals in the inner zone of the aquarium spent the same period in still water.

We then recorded the time the anemone took to recover from a startling stimulus as an index of perceived V [10]. These ‘startle response' durations should, on average, reflect underlying motivational states driven by variation in V (longer startle responses reflect lower V [10]). We thus elicited the startle responses of all individuals before (control, or startle response 1) and after exposure to flowing or still seawater (startle response 2; electronic supplementary material, figure S1b).

(b). Fighting and morphological measurements

We staged fights between pairs of anemones where one individual was designated the ‘focal' and the other the ‘opponent'. We used four treatments determined by the prior experiences of flowing or still seawater: flow versus flow (N-pairs = 20), no-flow versus no-flow (N-pairs = 20), flow versus no-flow (N-pair = 15) and no-flow versus flow (N-pairs = 15). We visually size-matched focals and opponents and we used a new rectangular aquarium (filled with seawater) for fights. After 1 h of acclimation, we moved the two anemones to the centre of the aquarium until they had contact with each other's tentacles (starting point of the fight). We considered the fight over when one anemone had moved one pedal disc diameter away (estimated visually) or retracted its tentacles for 10 min [14]. Following fights, we took samples from unused acrorhagi to measure nematocyst length (mm) and then measured the dry weight of anemones (g) [14].

(c). Statistical methods

To test if flow individuals perceive V higher than no-flow individuals, we used an ANCOVA with startle response 2 as a response variable, startle response 1 was a covariate and treatment was a category (flow or no-flow). As startle responses were not normal, we log-transformed them prior to analysis. Next, to test the effects of V and C on contest outcome and dynamics, first we used logistic regressions with (i) the outcome for focal individuals (win or lose) and (ii) whether fights escalated (stings or no stings) as our response variables, and treatment of focals and opponents as our categories. Startle responses, dry weight and nematocyst lengths are known to influence fighting ability in A. equina [14], and hence we used the absolute values of both focals and opponents as covariates in our model (supplementary material, Methods). As all continuous variables can scale exponentially with body size, we log10-transformed, centred and scaled them before adding to the model [15]. Second, we used a linear model to determine the effects of the predictors mentioned above on the contest duration (log10-transformed). We considered all p-values below 0.05 significant. All analyses were made in R v. 3.3.1 [16].

3. Results

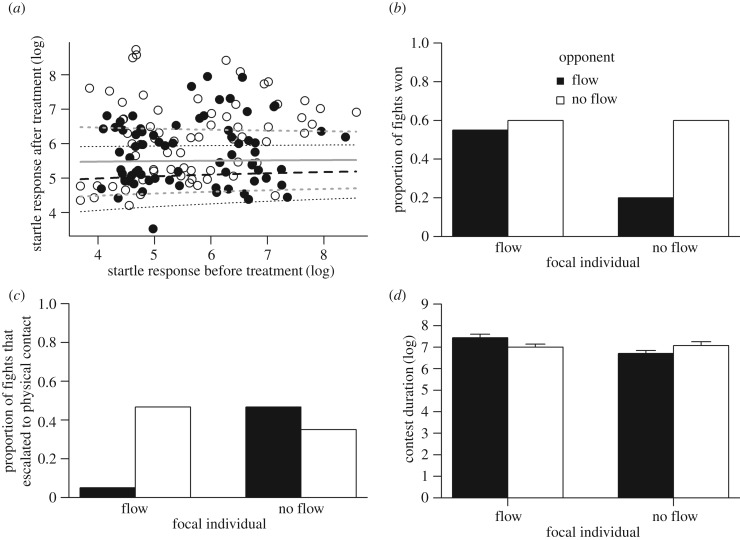

Anemones that were exposed to flow had shorter startle responses than individuals exposed to still water (F3,138 = 3.5, p = 0.017, R2 = 0.07; figure 1a). There was a non-significant trend for focals to be more likely to lose to opponents that had been exposed to flow ( , p = 0.058; figure 1b). An interaction between focal and opponent treatment indicates that escalation was more likely when each anemone had experienced different pre-fight conditions and least likely when both had been exposed to flowing seawater before fights, with no-flow versus no-flow in-between (

, p = 0.058; figure 1b). An interaction between focal and opponent treatment indicates that escalation was more likely when each anemone had experienced different pre-fight conditions and least likely when both had been exposed to flowing seawater before fights, with no-flow versus no-flow in-between ( , p = 0.012; figure 1c). Contests were longer when opponents had been exposed to flowing seawater (F1,60 = 4.3, p = 0.042). A near significant interaction effect indicates that the longest fights occurred when both opponents had been exposed to flowing seawater (F1,60 = 3.9, p = 0.053; figure 1d). For full details of the results including non-significant effects, see electronic supplementary material, tables S1–S4.

, p = 0.012; figure 1c). Contests were longer when opponents had been exposed to flowing seawater (F1,60 = 4.3, p = 0.042). A near significant interaction effect indicates that the longest fights occurred when both opponents had been exposed to flowing seawater (F1,60 = 3.9, p = 0.053; figure 1d). For full details of the results including non-significant effects, see electronic supplementary material, tables S1–S4.

Figure 1.

(a) Startle response duration of individuals that were exposed to a simulated tidal cycle (black solid line) were on average lower than the startle response duration of individuals that were not exposed to flow (grey solid line), even when we consider the startle response duration before treatment was applied (x-axis). However, confidence intervals overlap (black dotted lines, flow treatment; grey dashed lines, no flow treatment). (b) Proportion of fights won by a randomly chosen focal against its opponent following a 2 × 2 factorial experimental design. (c) Proportion of fights that escalated to highly aggressive and costly behaviours (i.e. stinging) regardless of who performed the behaviour. (d) Contest duration between focals and opponents of A. equina anemones (mean + s.e.); mean and s.e. values can be seen in Table S4.

4. Discussion

A small but significant difference in startle response durations between anemones held in simulated tidal flow and still water indicates that those held under a simulated tide were more motivated to return to their ongoing feeding behaviour, indicating that they perceived their territory as being of greater value (V). The chance of victory decreased when no-flow individuals fought opponents exposed to flow: flow individuals won 21 out of 30 fights against no-flow individuals (70%). Therefore, flow rate appears to influence persistence in a fight and hence the chance of victory.

Nevertheless, for anemones that were in flowing seawater, contests were less intense than contests involving individuals that were exposed to still water. Fewer than 10% of fights involved stinging when both opponents had been exposed to flowing water. Individuals may be less willing to escalate when opponents show a similar high V to avoid high levels of damage. Stinging results not only in damage to the opponent (e.g. skin necrosis, loss of feeding opportunities [14]), but also in self-inflicted damage. The acrorhagial epithelium is ‘peeled' away from the aggressor, and needs to be regenerated afterwards [17]. The focal individual with high V might thus be more cautious, and less likely to sting its opponent, because if the opponent also has high V it could significantly increase C. Thus, individuals with high V may just respond to stinging, rather than initiate stinging. If true, this would decrease the chances of stinging behaviour in the flow versus flow treatment. These results suggest that although more valuable resources might lead to greater persistence, high V does not necessarily lead to a high willingness to accept elevated chances of injury. Thus, V seems to be influencing decisions about persistence and injuries, both related to C, in different ways. In this case, longer fights between high V individuals are not unexpected. As both opponents avoid costly behaviours, contests take longer to resolve because C accumulates only with persistence, and not with injuries.

Flowing seawater influences the perceived value of the territories but anemones only seem to accept greater persistence costs, and not greater injury costs, because of increases in V. What is clear is that decisions to escalate can be altered by the abiotic environment. The costs and benefits of animal contests are typically investigated under stable conditions but aggression has evolved under natural conditions that show spatial and temporal variation. Thus, fighting behaviour may be considered a spatial–temporal mosaic in which the costs and benefits vary, sometimes due to predictable cycles (e.g. tidal, weather [6], stability [5]). Here, we have shown how fighting animals can adjust the strategic (whether to give up) and tactical (whether to escalate) decisions frequently modelled by evolutionary theory based on fluctuating environmental cues.

Supplementary Material

Ethics

This work was performed on invertebrates not covered by the Use of Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act. Thus, there is no requirement for ethical approval within the university that deals with animals used in this experiment. However, experiments were conducted following the ASAB/ABS guidelines on the use of animals in education and research.

Data accessibility

Data used can be found in Dryad: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.526g0 [18].

Authors' contributions

A.V.P. and M.B. designed the study. A.V.P. and M.V. performed the study. A.V.P., M.V., S.S. and M.B. performed the statistical analyses. A.V.P., M.B. and S.S. wrote the manuscript. M.V., S.S. and M.B. revised the manuscript. All authors approved the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the research.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

We thank Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superios (CAPES) for the Science without Borders scholarship to A.V.P. (99999.010227/2014-08) and M.V. Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the productivity grant to S.S. (311142/2014-1).

References

- 1.Maynard Smith J, Price GR. 1973. The logic of animal conflict. Nature 246, 15–18. ( 10.1038/246015a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enquist M, Leimar O. 1983. Evolution of fighting behaviour: decision rules and assessment of relative strength. J. Theor. Biol. 102, 387–410. ( 10.1016/0022-5193(83)90376-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payne RJ, Pagel M. 1997. Why do animals repeat displays? Anim. Behav. 54, 109–119. ( 10.1006/anbe.1996.0391) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy ICW, Briffa M. 2013. Animal contests. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peixoto PEC, Medina AM, Mendoza-Cuenca L. 2014. Do territorial butterflies show a macroecological fighting pattern in response to environmental stability? Behav. Process. 109, 14–20. ( 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.07.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elkins N. 2004. Weather and bird behaviour. London, UK: Poyser. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stutt AD, Willmer PAT. 1998. Territorial defence in speckled wood butterflies: do the hottest males always win? Anim. Behav. 55, 1341–1347. ( 10.1006/anbe.1998.0728) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prugh LR, Golden CD. 2014. Does moonlight increase predation risk? Meta-analysis reveals divergent responses of nocturnal mammals to lunar cycles. J. Anim. Ecol. 83, 504–514. ( 10.1111/1365-2656.12148) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briffa M, Sneddon LU. 2007. Physiological constraints on contest behaviour. Funct. Ecol. 21, 627–637. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01188.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briffa M, Elwood RW. 2001. Decision rules, energy metabolism and vigour of hermit-crab fights. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 268, 1841–1848. ( 10.1098/rspb.2001.1752) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnott G, Elwood RW. 2008. Information gathering and decision making about resource value in animal contests. Anim. Behav. 76, 529–542. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.04.019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elwood RW, Arnott G. 2012. Understanding how animals fight with Lloyd Morgan's canon. Anim. Behav. 84, 1095–1102. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.08.035) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ottaway JR. 1978. Population ecology of the intertidal anemone Actinia tenebrosa I. Pedal locomotion and intraspecific aggression. Mar. Freshwater Res. 29, 787–802. ( 10.1071/MF9780787) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudin FS, Briffa M. 2011. The logical polyp: assessments and decisions during contests in the beadlet anemone Actinia equina. Behav. Ecol. 22, 1278–1285. ( 10.1093/beheco/arr125) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schielzeth H. 2010. Simple means to improve the interpretability of regression coefficients. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1, 103–113. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00012.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.R Core Team. 2016. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lane SM, Briffa M. 2017. The price of attack: rethinking damage costs in animal contests. Anim. Behav. 126, 23–29. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2017.01.015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palaoro AV, Velasque M, Santos S, Briffa M. 2017. Data from: How does environment influence fighting? The effects of tidal flow on resource value and fighting costs in sea anemones. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.526g0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Palaoro AV, Velasque M, Santos S, Briffa M. 2017. Data from: How does environment influence fighting? The effects of tidal flow on resource value and fighting costs in sea anemones. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.526g0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data used can be found in Dryad: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.526g0 [18].