The nonlinear response of layer 5 mouse pyramidal dendrites was isolated with a novel systems-based approach. In response to dendritic current injections, the nonlinear component contained mostly fast, variable-amplitude, Na+ spikes. A functional model accounted for the timing and amplitude of the dendritic spikes and revealed that dendritic spikes are selective to a preferred input dynamic, which was verified experimentally. Thus, fast dendritic nonlinearities behave as high-frequency feature detectors that influence somatic action potentials.

Keywords: computational model, dendrite, electrophysiology, mouse, pyramidal neuron

Abstract

What do dendritic nonlinearities tell a neuron about signals injected into the dendrite? Linear and nonlinear dendritic components affect how time-varying inputs are transformed into action potentials (APs), but the relative contribution of each component is unclear. We developed a novel systems-identification approach to isolate the nonlinear response of layer 5 pyramidal neuron dendrites in mouse prefrontal cortex in response to dendritic current injections. We then quantified the nonlinear component and its effect on the soma, using functional models composed of linear filters and static nonlinearities. Both noise and waveform current injections revealed linear and nonlinear components in the dendritic response. The nonlinear component consisted of fast Na+ spikes that varied in amplitude 10-fold in a single neuron. A functional model reproduced the timing and amplitude of the dendritic spikes and revealed that they were selective to a preferred input dynamic (~4.5 ms rise time). The selectivity of the dendritic spikes became wider in the presence of additive noise, which was also predicted by the functional model. A second functional model revealed that the dendritic spikes were weakly boosted before being linearly integrated at the soma. For both our noise and waveform dendritic input, somatic APs were dependent on the somatic integration of the stimulus, followed a subset of large dendritic spikes, and were selective to the same input dynamics preferred by the dendrites. Our results suggest that the amplitude of fast dendritic spikes conveys information about high-frequency features in the dendritic input, which is then combined with low-frequency somatic integration.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The nonlinear response of layer 5 mouse pyramidal dendrites was isolated with a novel systems-based approach. In response to dendritic current injections, the nonlinear component contained mostly fast, variable-amplitude, Na+ spikes. A functional model accounted for the timing and amplitude of the dendritic spikes and revealed that dendritic spikes are selective to a preferred input dynamic, which was verified experimentally. Thus, fast dendritic nonlinearities behave as high-frequency feature detectors that influence somatic action potentials.

what do dendritic nonlinearities tell a cortical neuron about injected signals, and how do they contribute to the action potential (AP)? The answer to this fundamental question is not as straightforward as it might seem despite many years of pioneering work (Stuart and Spruston 2015). The transformation from dendritic input to somatic AP is performed largely by the dendrites. While a component of the dendritic processing can be described by linear and frequency-dependent models (Cook et al. 2007; Hu et al. 2009; Nettleton and Spain 2000; Watanabe et al. 2014), local dendritic nonlinearities play an important role in the form of Na+-, Ca2+-, and NMDA-mediated regenerative events (Harnett et al. 2013; Larkum et al. 2009; Oviedo and Reyes 2002; Schiller et al. 1997, 2000; Smith et al. 2013; Stuart et al. 1997). In this study, we ask: what is the optimal injected input that dendrites prefer, and how does it affect AP production?

In vivo inputs arriving throughout the dendrites combine to create a time-varying signal containing multiple frequency components (Destexhe et al. 2003). This input signal is filtered by the dendrites and produces in some neurons a theta resonance (~4–12 Hz) due to the contribution of voltage-dependent channels (Cook et al. 2007; Dembrow et al. 2015; Hu et al. 2009; Kalmbach et al. 2013; Narayanan and Johnston 2007; Ulrich 2002; Vaidya and Johnston 2013). Similarly, voltage-dependent channels allow certain input patterns to more efficiently generate nonlinear dendritic spikes (Gasparini et al. 2004; Gasparini and Magee 2006; Golding and Spruston 1998; Polsky et al. 2004; Sivyer and Williams 2013; Smith et al. 2013; Stuart et al. 1997). These results suggest that dendrites extract a preferred input feature, such as a particular frequency band or temporal input structure. Thus, understanding the transformation from dendritic input to somatic output requires identifying the feature of the input to which dendritic nonlinearities are selective.

To address this, we applied a systems-based framework (Sakai 1992; Wu et al. 2006) rather than the synapse-specific and channel-based models of previous studies. We demonstrate a novel deconvolution method for isolating dendritic nonlinearities in response to arbitrary dendritic inputs. The benefit of this approach is that the contribution of complex voltage-dependent currents is reduced to a series of simple linear and nonlinear functional components. These functional components, in turn, identify the optimal input parameters that the dendritic nonlinearities prefer.

White-noise and waveform current injections into the dendrites of mouse L5 pyramidal neurons in prefrontal cortex (PFC) revealed both linear and nonlinear components in the dendritic membrane potential. The nonlinear component consisted mainly of Na+ spikes that varied in amplitude in single neurons by over a factor of 10, with a firing rate much higher than that of the somatic APs. These dendritic spikes were selective to a specific input dynamic (rise time of ~4.5 ms), with shorter or longer rise times producing a graded reduction in spike amplitude. Importantly, a simple functional model predicted dendritic spike timing and amplitude and reproduced the temporal selectivity of the dendritic spikes. We also observed that dendritic spikes preceded most APs and that a second functional model that linearly combined boosted dendritic spikes with the stimulus accounted for the somatic membrane potential.

This functional framework suggests that dendritic nonlinearities ensure that APs can be elicited by preferred input patterns that a linear dendrite would otherwise not detect. Thus, L5 neurons function as a two-layer neural network, with dendritic nonlinearities extracting a feature of the input and the output of this computation integrated at the soma (Das and Narayanan 2014; Larkum et al. 2009; Poirazi et al. 2003a, 2003b). These data reconcile an apparent inconsistency in the literature, that high-frequency inputs can entrain AP firing despite low-pass filtering by the dendrite-to-soma transfer function (Colgin et al. 2009; Fries 2009).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Slice preparation.

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male C57BL/6 mice, 8–16 wk old, were anesthetized with a ketamine (100 mg/kg)-xylazine (10 mg/kg) cocktail and were perfused through the heart with ice-cold saline consisting of (in mM) 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2, 7 dextrose, 205 sucrose, 1.3 ascorbate, and 3 sodium pyruvate (bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2 to maintain pH at ~7.4). A vibrating tissue slicer (Vibratome 3000, Vibratome) was used to make 300-μm-thick coronal sections. Slices were held for 30 min at 35°C in a chamber filled with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) consisting of (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 dextrose, and 3 sodium pyruvate (bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2) and then at room temperature until the time of recording.

Whole cell recordings.

Recordings were made from pyramidal tract-projecting (PT) L5 pyramidal neurons in the dorsal medial PFC ~1–2 mm anterior to bregma. The presence of membrane resonance was used to discriminate PT neurons from intratelencephalic projecting neurons (Dembrow et al. 2010, 2015; Kalmbach et al. 2013, 2015). Neurons that displayed a peak in the frequency-response curve in response to white noise > 2 Hz were classified as PT neurons. Slices were placed in a submerged, heated (32–34°C) recording chamber that was continually perfused (1−2 ml/min) with bubbled aCSF containing (in mM) 125 NaCl, 3.0 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 dextrose, 3 sodium pyruvate, 0.025 d-(−)2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid, 0.002 gabazine, and 0.02 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione. Slices were viewed with a Zeiss Axioskop microscope and differential interference contrast optics. Alexa 594-filled neurons were visualized with a mercury lamp and a 540-/605-nm filter set. Patch pipettes (4−8 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass and wrapped with Parafilm to reduce capacitance. The pipette solution contained (in mM) 120 K gluconate, 16 KCl, 10 HEPES, 8 NaCl, 7 K2 phosphocreatine, 0.3 Na-GTP, and 4 Mg-ATP (pH 7.3 with KOH). Neurobiotin (Vector Laboratories; 0.1%) was also included for histological processing. Alexa 594 (16 μM; Invitrogen) was included in the internal recording solution to determine the distance from the soma of the recording location upon termination of the experiment.

Data were acquired with Dagan BVC-700 (Dagan) amplifiers and custom data acquisition software written with IGOR Pro (WaveMetrics). Data were acquired at 10 kHz, filtered at 3 kHz, and digitized by an ITC-18 (InstruTech) interface. Pipette capacitance was compensated, and the bridge was balanced during each recording. Series resistance was monitored throughout each experiment and was 10–30 MΩ for somatic recordings and 15–35 MΩ for dendritic recordings. Voltages are not corrected for the liquid junction potential (estimated as ~12 mV). We verified that there was no appreciable frequency-dependent filtering of the white-noise current stimulus by the electrode.

A total of 29 dendritic recordings were made from the apical trunk and, with the exception of 2, were within 70 μm of the nexus of the apical tuft, near the L1-L2/3 border. Figure 1A illustrates the dendritic recording locations overlaid on a typical L5 pyramidal cell and highlights that most recordings were just proximal of the nexus, with three recordings distal to the nexus. Simultaneous soma recordings were performed in 16 of the 29 experiments.

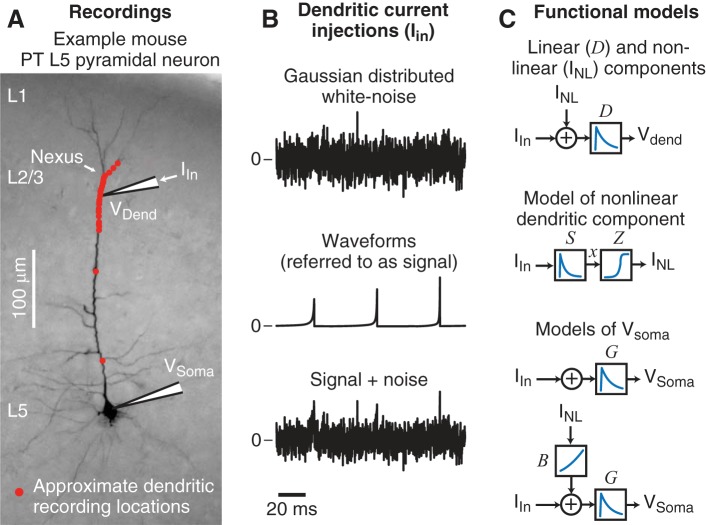

Fig. 1.

Summary of recording locations, dendritic stimuli and functional models. A: typical mouse pyramidal tract-projecting (PT) L5 neuron that is representative of the neurons recorded in these experiments. Current stimuli (Iin) were injected through the dendritic electrode while the dendritic potential (Vdend) was measured. In 16 of 29 experiments the somatic potential (Vsoma) was also simultaneously recorded. The approximate recording location (red dots) of each experiment is overlaid. Most dendritic recordings were just proximal to the nexus of the main apical dendrite, with 3 recordings distal to the nexus. B: short examples of the 3 types of current stimuli injected into the dendrites. Top: Gaussian-distributed white noise. Middle: a randomized sequence of 9 different waveforms (referred to as signals) at 50-ms intervals, whose shapes were based on the initial characterization of the dendritic nonlinearities. Bottom: a combination of 50%-amplitude white noise and the waveforms (referred to as signal+noise). Stimulus injections lasted 1–2 min. See materials and methods for details regarding stimulus generation. C: summary of the functional models used to analyze the data. Top: the dendritic potential was described by a linear filter (D) convolved with the current stimulus (Iin) plus a current that represented the contribution of the dendritic nonlinearities (INL). Middle: the dendritic nonlinearity (INL) was modeled as the convolution of the dendritic input (Iin) with a linear spike filter (S), with the output of the filter (x) passed through a static, sigmoidal-shaped, nonlinearity (Z). Bottom: a linear filter (G) convolved with the dendritic input described the somatic potential. A second model added in the dendritic nonlinearity (INL) that was first slightly boosted by a quadratic function (B). See materials and methods for details of the functional models.

General analysis.

We used a combination of noise and waveform dendritic current injections (Fig. 1B) to develop four functional models of the dendritic and somatic membrane responses (Fig. 1C). Although the mathematical details of each functional model are described below in materials and methods, for clarity we also include each model’s structure in results. The analysis and modeling were performed in MATLAB R2014b. Error bars and variability are reported as SE unless otherwise noted. Statistical analyses were performed with the MATLAB ttest and corr (Pearson’s correlation, R) functions.

Stimulus and TTX conditions.

All 29 dendritic recordings were performed with a stimulus current injected (referred to as Iin) through the dendritic recording pipette for 1–2 min. Every experiment included a large, zero-mean, Gaussian-distributed white-noise input condition (Fig. 1B, top). For the large noise the variance was set to be above the threshold that produced somatic APs. In 15 experiments we included the small-noise input condition, which was subthreshold with no somatic APs. A different random seed was used for each experiment, but for a given neuron the large- and small-amplitude noise injections had the same seed and only the variance was different.

In 14 experiments we also included two other dendritic current injections. First, a sequence of waveforms was injected (Fig. 1B, middle), which we refer to as signal. For this stimulus different signal waveforms were injected every 50 ms, where the shape of each waveform was determined by our initial set of experiments using the noise stimulus (see below). Second, a signal+noise input condition (Fig. 1B, bottom) was also used in which the same waveforms were added to the 50% amplitude large-noise condition.

For the 16 of the 29 experiments in which we simultaneously recorded the soma potential, 11 soma recordings were performed during the small-noise conditions and 5 soma recordings were performed during the waveforms (signal only and signal+noise). Details of how the signal-only and signal+noise waveforms were constructed are described below in materials and methods. In four experiments, TTX was either bath applied or puffed on the dendritic recording site after recordings were performed in the normal external solution. Before and during local TTX application at the dendritic recording site, somatic APs were elicited by 3-ms step current injections delivered through the somatic recoding electrode.

Preprocessing of electrophysiological recordings.

Except for a single experiment, the same input conditions were alternately presented for multiple sweeps (range 2–6, median = 5 sweeps per condition). Individual sweeps of the dendritic and soma membrane potential were detrended by using a second-order polynomial to remove small DC drifts during the long 1- to 2-min recording. Individual sweeps were then averaged together for most analyses in order to reduce experimental noise. However, single sweeps were analyzed individually when examining the repeatability of nonlinear current INL and the relationship between individual dendritic spikes and individual somatic APs.

Estimation of linear component of dendritic response.

As shown in Fig. 1C, top, we first estimated the impulse response function of the linear filter (D) that best accounted for the recorded dendritic potential, Vdend, with

| (1) |

where Iin is the current injected at the dendritic electrode, k is a constant, and * is the convolution operator. Preliminary analysis showed that most of the power in Vdend was below 1 kHz; thus we downsampled at 2 kHz, resulting in 120,000 data points for a 1-min recording sweep (or 240,000 data points for a 2-min recording sweep). Filter D was assumed to have an impulse response function < 250 ms (or 500 elements at the 2 kHz sample rate). We represented the convolution in Eq. 1 as the matrix multiplication

| (2) |

where A is an N × LD + 1 design matrix, LD is the length of filter D (500 samples), and D and Vdend are column vectors of length LD + 1 and N, respectively. Note that D includes the constant term k and that N is the number of data points = 120,000 (or 240,000). Equation 2 is an overdetermined system of linear equations and was solved for D with MATLAB’s linear regression function. The estimated dendritic potential, V̂dend, was then computed with Eq. 1.

The goodness of fit of V̂dend was quantified with the R2 metric (referred to here as variance accounted for or VAF). Because the number of data points was much larger than the number of free parameters in D, the bias in our reported VAF was estimated with an adjusted R2 (Zar 1999) and found to be ~0.1%. Linear filters (D) were estimated separately for each cell and input condition and, on average, were found to be very similar across conditions. For display purposes, V̂dend was upsampled back to the original 10 kHz sampling rate with Fourier interpolation.

Estimation of the nonlinear (INL) component of the dendritic response.

The error in the linear fit of the dendritic membrane potential

| (3) |

was assumed to be due to a nonlinearity in the dendritic response that was not captured by the linear filter (D). We observed that Verror was near zero most of the time. When errors occurred, however, they were mostly transient, positive, deflections that decayed with a timescale similar to the shape of the filter (D). This suggested that the nonlinearity in the dendritic response could be modeled as current impulses located at the input to the linear filter (D). Thus, we deconvolved Verror in Eq. 3 back across the linear filter (D), which transformed Verror into the nonlinear current INL (Fig. 1C, top), such that

| (4) |

If INL is computable, which is not always guaranteed and can depend on the amount of experimental noise present in the dendritic recording Vdend, then from Eqs. 1, 3, and 4, the dendritic potential is fully described by

| (5) |

To estimate INL, we expressed the convolution in Eq. 4 in matrix form as

| (6) |

where B is a M × M + LD design matrix constructed from D and INL and Verror are column vectors of length M + LD and M, respectively. Equation 6 represents an underdetermined system of linear equations, and we solved for INL with the MATLAB function mldivide. Because of the computational limits for inverting the large matrix B, we solved for INL in overlapping 6-s blocks (M = 12,000). Note that using the 2 kHz sampling rate had the beneficial effect of reducing high-frequency noise, which could adversely affect the deconvolution process. However, this tended to smooth the nonlinear spikes contained in INL.

Estimating INL using deconvolution worked well with our dendritic recordings and only failed on ~2% of individual recording sweeps. Inspection showed that these recording sweeps contained large amounts of experimental noise and were eliminated from further analysis. We verified all estimates of INL by recomputing Vdend with Eq. 5 and showing that it matched the recorded dendritic potential. Finally, for display purposes INL was upsampled back to the original 10 kHz time base with Fourier interpolation.

Reliability of INL to repeated stimulus sweeps.

Because the deconvolution of Verror enhanced high-frequency experimental noise in our dendritic recordings, we examined the reliability of INL to repeated presentation of identical large-noise stimulus sweeps. We hypothesized that if INL was driven by the stimulus and not the experimental noise, then it would be similar for every identical stimulus sweep. We quantified this reproducibility by computing the Pearson’s correlation between individual sweeps of INL that were first convolved by a Gaussian. The standard deviation of the Gaussian represented the temporal resolution under which the correlation was computed. For example, as the temporal resolution becomes larger, the correlation becomes less dependent on the exact timing of spikes in INL. At a temporal resolution of ~0.5 ms, the average correlation between INL sweeps plateaued at a relatively high value (~0.9).

Noise floor and identifying individual current spikes in INL.

We identified individual current spikes contained in INL based primarily on amplitude. Thus, we first set a criterion for the minimum spike amplitude (referred to as the noise floor, dashed line in most plots of INL). For each experiment, we estimated the noise floor as the three-standard deviation level (99.7%) of the negative amplitude distribution of INL. As shown by the population amplitude distribution (see Fig. 3B below), INL was positively skewed above the average noise floor. In addition to the minimum spike amplitude (i.e., noise floor), spikes were also isolated based on a width at half-height < 2.5 ms.

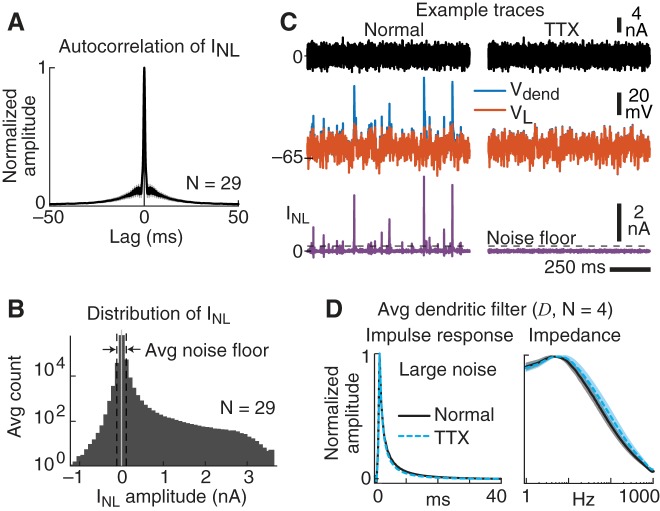

Fig. 3.

Properties of the nonlinear current (INL). A: the average autocorrelation function of the nonlinear current (INL) shows a weak correlation within a ~25-ms window. B: amplitude histogram of INL averaged across all recordings. All neurons contributed to each bin. The average noise floor refers to the three-sigma distribution around zero (see materials and methods). C: example traces to the same noise pattern before and after application of TTX. Errors in the linear component (Vdend vs. VL) and nonlinear current spikes in INL were completely eliminated by application of TTX. Similar effects were observed in all 4 TTX experiments. Two experiments bath applied TTX, and two had local application of TTX to the dendrites (see Fig. 7, F–I). D: the average linear dendritic filter (D) was relatively unaffected by the application of TTX. Left: normalized impulse response functions. Right: normalized impedance amplitude profiles. Shading is SE.

Spike-triggered average of INL.

To compute the spike-triggered averages (STAs) of INL, we selected well-isolated spikes that had amplitudes > 1.5 × noise floor and that did not occur within 10 ms of a preceding dendritic spike or somatic AP. This selection process resulted in 23,820 identified dendrite spikes used to compute the STAs and ensured that all spikes were well isolated, unlikely to be due to noise, and not linked to a dendritic burst or back-propagating somatic APs.

Estimation of the cascade model of INL.

We modeled INL as a function of the stimulus, using a standard cascade model of a linear filter followed by a static nonlinearity (Fig. 1C, middle). This type of functional model (usually referred to as an LN model) and its many variants have a long track record of modeling the spike activity of neurons (Hunter and Korenberg 1986; Sakai 1992; Wu et al. 2006).

In this model, INL was modeled as a linear “spike” filter (S) convolved with the stimulus, Iin. The output of the spike filter (x) was then mapped onto a static nonlinearity (Z) that transformed how well the stimulus matched the spike filter into a graded nonlinear current spike. Based on the shape of the stimulus STA of INL, the spike filter’s impulse response function was set be 200 ms long and parametrically modeled with Gaussian and exponential functions. The Gaussian part, H, was used to model the rise of the filter S (first 0.5 ms), and the exponential part, E, described the decay of the filter such that

| (7) |

where

| (8) |

| (9) |

Thus, the spike filter (S) had 10 free parameters.

The static nonlinearity (Z) was modeled as two generalized sigmoidal functions based on our inspection of the relationship between the output (x) of the spike filter (S) and the actual spike amplitudes. Thus, we used two general sigmoid functions to describe the initial slow amplitude rise (Q1) and faster amplitude saturation (Q2) of the dendritic spikes:

| (10) |

where

| (11) |

with 5 free parameters in the static nonlinearity (Z).

The most important aspect of the optimization was accounting for the temporal jitter between actual and model INL spikes. Careful inspection of the relative alignment of the stimulus and INL spike STAs revealed that the actual spike peaks varied in latency depending on their amplitude. Small dendritic current spikes in INL peaked immediately after the stimulus, while large dendritic spikes required an additional 0.5 ms to reach their peak amplitudes. Thus, we allowed the model spikes to vary in their alignment with the data, within a range of 0.7 ms before to 0.2 ms after an actual dendritic spike. This was accomplished by sliding a 1-ms-wide “max filter” across the output of the static nonlinearity (Z) such that

| (12) |

where W is the 1-ms max window. As this produced model spikes resembling 1-ms square pulses, for display purposes model spikes greater than or equal to the noise floor were replaced with a 1-ms-wide Hann window centered on the square spike, while model INL values less than the noise floor were set to zero.

We optimized the model (Eq. 12) separately for each cell. To speed up the optimization, we only fit the model to the isolated dendritic spike times and peak amplitudes that were greater than or equal to the noise floor. We used the MATLAB function lsqcurvefit to optimize the model parameters. Note that since β in Eq. 11 is linear within the parameters, it was solved for with linear regression on every optimization step. Initial starting values for the parameters were based on the stimulus STA of INL. Because the amplitude of the model’s dendritic spikes was an important feature of the model, the saturating nonlinearity (Z) precluded the use of a more efficient optimization approach (Paninski 2004).

The number of spikes typically available in a single experiment was relatively small (~1,500 on average); thus we used twofold cross-validation to assess the goodness of fit of the model. The validated VAF of the model was based on fitting the model to half the data and testing the goodness of fit on the other half. Overall, the model did relatively well, capturing the spike timing and amplitude with a median cross-validated VAF = 85%. Note that we also validated the model using the ~98% of the data where INL was below the noise floor and not used for the optimization. In this case, the model false alarm rate was very low (reported in results). Although we do not claim that our model of the dendritic nonlinearity (INL) represents a global best fit, it was remarkably good at mimicking the dendritic spike timing and amplitude in the data, as well as predicting the selectivity profile in response to waveform stimuli injected into the dendrite.

Temporal selectivity of INL.

To measure the temporal selectivity of INL, we injected the signal-only and signal+noise waveforms (Fig. 1B) into the dendrites. Each stimulus contained a series of 9 stretched or compressed versions of the average dendritic STA of INL estimated from the first 10 large-noise experiments. Signal waveforms were presented every 50 ms in a random order. All signal waveforms were normalized to their sum of squared values in order for each signal to have equal energy (Lathi and Ding 2010). For the signal+noise condition, the same signals were added to the 50%-reduced large white-noise input. The amplitude of the injected signals was set to be at threshold in order to produce the occasional somatic AP for the preferred signal rise time.

To construct selectivity curves, we computed the peak of the average INL that followed each of the nine signal waveforms and plotted this average peak current vs. the log of the 10–90% rise time of the signal waveforms. The selectivity profile was then described by fitting a Gaussian function to this data with

| (13) |

where r is 10–90% rise time of the input signal, C is a constant, and the selectivity parameters of interest are the preferred rise time (μ) and selectivity width (σ).

We fit the same cascade model described above to the model INL in response to the signal-only and signal+noise dendritic inputs. The model used the same spike filter (S) estimated from the large-noise condition, but we refit the static nonlinearity (Z). This was because during the signal-only and signal+noise conditions the amplitudes of INL spikes were ~50 and 75% smaller, respectively, compared with spikes in the large-noise condition. Using the model INL response to the signal-only and signal+noise conditions, we fit the same Gaussian (Eq. 13) to extract the model’s selectivity and compared these to the selectivity parameters observed for each cell.

Somatic integration of dendritic spikes.

To measure the effect that the dendritic spikes contained in INL had on the response at the soma, we performed 16 experiments with simultaneous dendritic and soma electrodes. Large-amplitude white noise was injected through the dendritic electrode, and INL was computed as described above. For all analysis involving somatic responses we only used single recording sweeps, in order to precisely capture the relative timing between the dendritic spike and somatic AP.

As shown in Fig. 1C, bottom, we modeled the response at the soma, Vsoma, using two functional models. In the first, we estimated a soma linear filter, G, such that

| (14) |

We estimated the soma linear filter (G) with the same methods as those for estimating the dendritic linear filter (D).

To investigate the contribution of INL to the soma response, we added a boosted version of INL to the noise stimulus such that

| (15) |

where B(x) = ax + bx2 and accounted for additional nonlinear contributions to the somatic potential. Thus, the boosting of the nonlinear current in Eq. 15 captured the additional nonlinearities in the neuron not measured at the dendritic electrode. Note, however, that the boost did not change the dynamics of the dendritic nonlinearity but only scaled its amplitude. The linear filter G was essentially the same whether it was estimated using only the noise stimulus (Eq. 14) or also included INL (Eq. 15).

Latency of individual somatic APs.

We isolated 3,241 individual somatic APs. The latency of the soma AP was measured from the start of the nearest dendritic spike to the start of the AP. Because of the noise floor, it was difficult to estimate the start of the dendritic spike from a threshold applied to the derivative of INL. Therefore, we estimated the start of the dendritic spike by projecting a line down from the maximal slope of its rising phase. This line had the same slope as the maximal slope, and where it crossed zero was recorded as the start of the dendritic spike. Inspection of individual dendritic spikes suggested that this method did a good job of identifying the start of the dendritic spike to within about one sample (~0.1 ms). Because of the low amount of recording noise, the start of the AP was computed as where the slope of the rising phase of the AP intersected a 40 mV/ms threshold (measured to within 0.01 ms with linear interpolation).

Because of the variability in our estimate of the start of the dendritic spike, we applied a conservative latency criterion of at least 0.2 ms to classify a somatic AP as following the dendritic spike. This resulted in 64 APs with latencies < 0.2 ms. Most recordings had mean AP latencies > 1 ms, which was much greater than our potential latency measurement error.

Temporal selectivity of soma APs.

In five experiments, we recorded from both the dendrite and soma while the signal-only and signal+noise stimuli were injected. To measure the selectivity of soma APs, we estimated the probability of observing a soma AP following a particular signal. Because we set the amplitude of the injected waveforms to threshold, the probability of observing a soma AP was low, even for the preferred 10–90% rise times. We then plotted the peak soma AP probability vs. signal rise time and fit with a Gaussian (Eq. 13).

RESULTS

We made whole cell recordings from the distal apical trunk and primary tuft branches of mouse PT L5 pyramidal dendrites (Dembrow et al. 2010, 2015; Kalmbach et al. 2013, 2015) (median location 280, range 50–380 μm, N = 29). L5 PT neurons in mouse PFC are located ~450–600 μm from the pial surface, with the apical tuft starting at the L1-L2/3 border (Fig. 1A). Our recording locations spanned the entire extent of the main apical trunk and the proximal part of the apical tuft. However, all recordings from the apical trunk, with the exception of two, were within 70 μm of the nexus of the apical tuft, near the L1-L2/3 border, and three recordings were slightly distal to the nexus (red dots, Fig. 1A). Thus, our results mainly address dendritic integration near the nexus of the apical tuft in L5 pyramidal neurons of PFC.

We applied a systems approach to study how the dendrites integrated arbitrary current injections. The dendritic stimuli were long periods (1–2 min) of noise, waveforms, or a combination of the two (examples shown in Fig. 1B). Functional models (summarized in Fig. 1C) were used to describe the dendritic membrane potential (Vdend), dendritic nonlinearity (INL), and somatic potential (Vsoma) in response to our dendritic stimuli. Our results below systematically develop the structure and rationale for each model as we characterize the dendritic nonlinearities.

Although dendritic current injections do not reproduce the conductance changes associated with in vivo synaptic input, a noise input has several advantages for characterizing dendritic signal processing: 1) Bypassing the synaptic contributions allowed the dendritic component to be isolated and described with functional components. 2) The noise stimulus contained a wide constellation of frequency components that dendrites may experience in vivo, thus mimicking the fast fluctuations caused by the background activity of the thousands of synapses on cortical dendrites. 3) It facilitated the application of systems-identification techniques to construct and test functional models (Hunter and Korenberg 1986; Sakai 1992; Wu et al. 2006).

Linear component of dendritic response.

In the first 15 experiments, the variance of the injected current was set to produce either sub- or suprathreshold responses on alternating stimulus presentations (referred to as small and large noise; Fig. 2A). Figure 2B shows examples of the injected current stimulus (black) and dendritic membrane potential (Vdend, blue) for a recording 275 μm from the soma. Across the population, the small-noise condition produced depolarizations from rest of only a few millivolts (mean 1.7 ± 0.1, max 11.5 ± 2.3 mV), while the large noise resulted in substantial dendritic depolarizations (mean 7.8 ± 0.4, max 80.3 ± 2.1 mV) and somatic APs (addressed below).

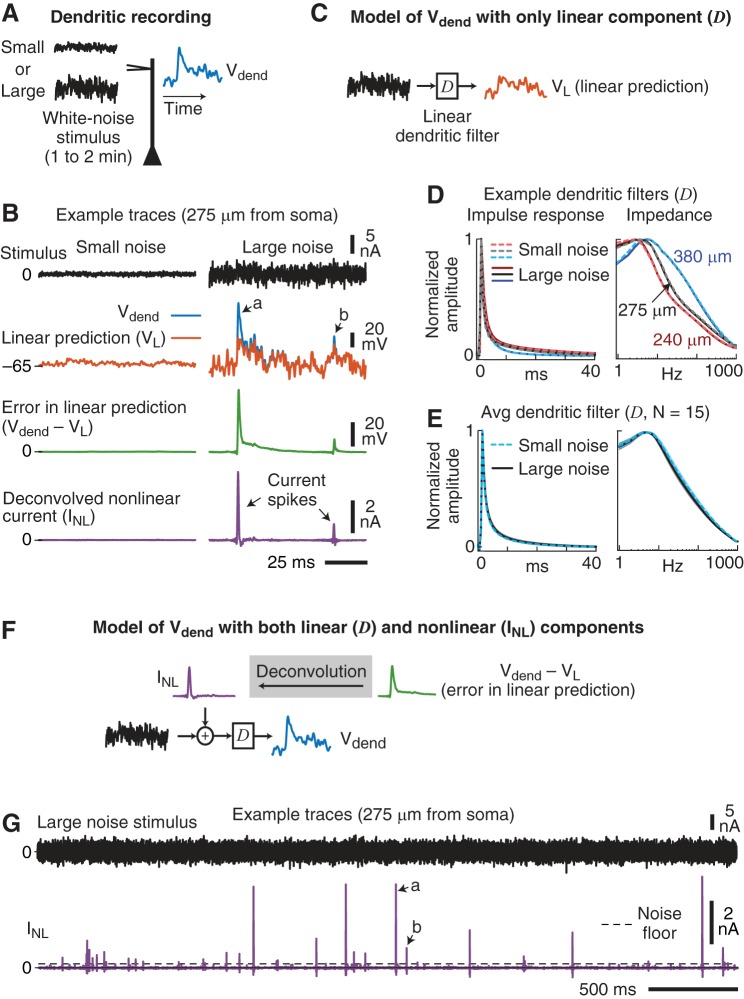

Fig. 2.

Isolating the linear and nonlinear components of the dendritic membrane potential. A: the membrane potential in the dendrite was recorded (Vdend) in response to small- and large-amplitude Gaussian-distributed white-noise current injections. B: example traces from a dendritic recording 275 μm from the soma for the small (left)- and large (right)- amplitude white-noise stimuli. Traces show the recorded membrane potential (blue), linear prediction (VL, orange), and nonlinear component (INL, purple) of the dendritic membrane response. For the small-noise stimulus, the linear prediction overlapped the measured dendritic potential. Arrows a and b denote large and small errors (green), respectively, in the linear prediction (VL) during the large-noise stimulus. C: the linear component of the dendritic response was modeled as a linear filter (D). Convolving the linear dendritic filter with the white-noise stimulus produced the linear prediction (VL, orange) of the dendritic potential. D: example linear dendritic filters (D) from 3 dendritic recording locations for the small (dashed)- and large (solid)-noise stimuli. Left: normalized impulse response functions. Right: normalized impedance amplitude profiles. The distance of the dendritic recording electrode from the soma is labeled. E: average linear dendritic filters for the small- and large-noise stimuli. Shading is SE. F: the nonlinear component of the dendrites was modeled as a current (INL, purple) added to the stimulus. INL was estimated from the voltage errors in the linear prediction (green) by deconvolution. By mathematical definition, when the injected stimulus + INL was convolved with the dendritic filter, this model reproduced the measured dendritic potential (blue). Thus, INL represented the contribution the dendrites made to the dendritic stimulus current. G: extended example trace of the nonlinear component (INL) in response to the large-noise stimulus. INL was composed of mostly inward depolarizing current spikes of varying amplitudes. Arrows a and b correspond to the same nonlinear dendritic current spikes in B. Dashed line (noise floor) is the minimal INL amplitude used for the identification of individual dendritic spikes (see materials and methods).

We first isolated the linear component of the dendritic signal processing by fitting a linear filter (D) to each input condition (Fig. 2C). The linear filter was optimized (see materials and methods) such that when it was convolved with the noise current injection it produced a linear prediction of the dendritic potential (VL; orange, Fig. 2C). Example dendritic filters for three cells are shown in both the time and frequency domains in Fig. 2D. The filters had relatively broad frequency responses with a peak at ~8 Hz, and their impulse response function had 10–90% decay times that differed by <1 ms between small and large noise (P < 0.001, paired t-test, N = 15). As illustrated in Fig. 2D, filters systematically decayed faster as dendritic location increased (R = –0.82, P < 0.001).

The average dendritic filters (Fig. 2E) show that across the population filters were very similar between the small- and large-noise stimuli. Thus, the linear component of the dendritic membrane potential (D) was relatively invariant to stimulus amplitude.

We next compared the linear prediction of the dendritic membrane potential (VL), obtained by convolving the dendritic filter with the noise stimulus, to the actual recorded dendritic potential (Vdend). As illustrated in Fig. 2B, for the small-noise condition VL (orange) completely overlapped the measured Vdend (blue) and thus perfectly reproduced the dendritic potential. Across the population, the variance accounted for (VAF) by the dendritic filter in the small-noise condition was on average 99.8 ± 0.1% (N = 15). Thus, the dendritic potential was fully described by the linear filter (D) during small random inputs.

The linear filter was comparatively less able to predict the dendritic potential during the large-amplitude noise (VAF = 96.2 ± 0.7%). Inspection of the linear prediction (VL vs. Vdend; Fig. 2B) revealed that the dendritic response also contained a nonlinear component that produced additional depolarizations during the large noise (arrows a and b). Although the linear component (D) did not change as the stimulus became larger, it accounted for less of the dendritic membrane potential.

Isolating nonlinear component of dendritic response.

Inspection of the errors in the linear fit (green, Fig. 2B) revealed stable periods of linearity (i.e., error near 0) interspersed with voltage errors of different amplitudes. Importantly, the errors were typically positive and exhibited a fast rise time followed by a slow decay that approximated the shape of the dendritic filter. This suggested that the voltage errors could be modeled as current impulses located at the input to the dendritic filter (Fig. 2F).

We used deconvolution to transform the voltage error (green) into a nonlinear current (INL, purple) that was added to the dendritic stimulus (Fig. 2F). In all figures, a positive INL represents depolarizing current injected into the dendrite. By definition, convolving the dendritic filter with INL + the noise stimulus reproduced 100% of the dendritic membrane potential.

Relationship of model to passive and active properties of dendrites.

Transforming the nonlinear component of the dendritic response from a voltage error into a current (INL) was a novel step in our analysis. INL represents a model of the net current produced by ion channels that are known to contribute to the generation of dendritic nonlinearities (including Na+ and Ca2+ channels). Importantly, INL provides a precise description of the dendritic nonlinearity in response to arbitrary stimulus patterns, which cannot be gleaned from a casual observation of the dendritic membrane potential alone.

Our model in Fig. 2F is closely related to the passive and active properties that have been traditionally been used to quantify the dendritic response. The linear component of the model (D) captures the linear passive membrane response plus any contributions by voltage-gated channels that behave in a linear fashion. Thus, the nonlinear component, INL, represents the contribution of active properties that cannot be captured by a linear model. Separating the contribution of voltage-gated channels into their linear and nonlinear components allows us to focus only on the nonlinear active properties.

Properties of nonlinear component (INL).

As shown by the example trace on a longer timescale (Fig. 2G), INL consisted of mainly brief, inward, current spikes of varied amplitude. We next quantified the properties of these dendritic current spikes. First, we wanted to know whether the amplitude of a dendritic spike depended on the amplitude of previous dendritic spikes. Across all 29 experiments that used the large-noise stimulus, the average autocorrelation function of INL was relatively flat, exhibiting only a weak positive correlation within ~25 ms (Fig. 3A). Thus, dendritic spike timing and amplitude were largely independent, with a slight tendency of spikes to cluster within 25-ms bursts.

Because deconvolution can enhance experimental noise, we next examined the reliability of INL. The timing and amplitude of dendritic spikes were nearly identical between presentations of the same stimulus (data not shown; see materials and methods), suggesting that INL was directly linked to the stimulus pattern injected into the dendrites, with minimal effects of experimental noise.

To isolate individual dendritic spikes we needed to first quantify the noise levels in INL. The average amplitude distribution of INL was positively skewed, reflecting a range of inward current spike amplitudes that produced membrane depolarization (Fig. 3B). Large negative portions of INL presumably reflected active conductances involved in membrane repolarization. Small amplitude variations around zero likely represented the experimental noise in INL. The three-sigma noise level (equivalent to 99.7% of the noise) was estimated separately for each cell (referred to as the noise floor, vertical dashed lines in Fig. 3B; see materials and methods). Individual INL spikes with amplitudes above the noise floor were classified as dendritic current spikes. As illustrated by the example INL trace in Fig. 2G, isolated dendritic spike amplitudes above the noise floor varied by over a factor of 10 in single neurons.

Across the population (N = 29), isolated dendritic current spikes occurred at a mean rate = 25 ± 12 (SD) spikes/s and had an average width at half-height = 0.7 ± 0.05 (SD) ms. Small dendritic spikes tended to have a symmetrical shape, possibly due to the 2 kHz sampling rate used in our analysis (see materials and methods). As we show below, however, many large dendritic spikes, especially those preceding somatic APs, had nonsymmetrical features. In addition, application of 1 μM TTX completely eliminated all INL spikes (N = 4, example traces shown in Fig. 3C) but had no appreciable effect on the linear component of the dendrite (filter D; Fig. 3D).

In summary, the properties of INL suggest that during the random noise input the nonlinear component of the dendritic signal processing was composed of mainly Na+ channel-mediated current spikes that were tightly linked to the stimulus, occurred at a relatively fast rate, and were highly variable in amplitude.

Dendritic current spike amplitude was correlated with stimulus rise time.

What do the amplitude and timing of a dendritic current spike tell the neuron about the injected stimulus? In other words, why did the dendrite sometimes produce small-amplitude spikes while at other times it produced large spikes? As illustrated by the two example dendritic current spikes in Fig. 4A (1 large at 5.2 × noise floor and 1 small at 1.1 × noise floor), the largest stimulus fluctuations (arrows) did not coincide with the occurrence of a spike, while a steady rise of the stimulus seemed to precede each spike, especially the larger spike.

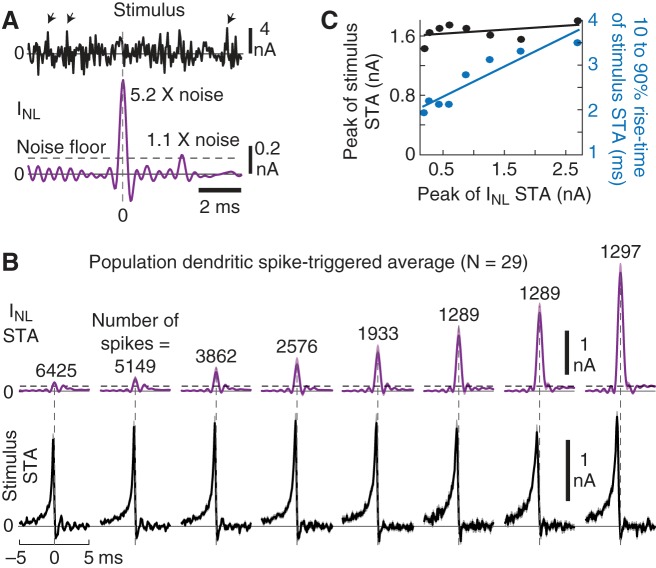

Fig. 4.

Spike-triggered averages (STAs) reveal the link between dendritic current spikes and the input stimulus. A: example trace of INL (purple) showing 2 dendritic current spikes (one 5.2 × and the other 1.1 × noise floor). The stimulus (black) highlights that fast, large, stimulus fluctuations (arrows) were not followed by a dendritic spike. B: STAs of the dendritic current spikes (purple) and stimulus (black), grouped by dendritic current spike amplitude and aligned to the peak of the spike (0 ms). STAs were computed based on 23,820 dendritic current spikes isolated from INL (see materials and methods) and show the average across all 29 experiments. Note that the peak of the current spike STA increased, while the peak of the stimulus STA was relatively flat. Because of the nonuniform distribution profile of INL (see Fig. 3B), more spikes contributed to the smaller-amplitude STA bins. Dashed line is the noise floor, and shading is SE. C: the 10–90% rise time (blue), but not the peak amplitude (black), of the stimulus STA increased as a function of dendritic current spike size.

To quantify what a dendritic current spike tells the neuron about the stimulus, we applied the STA theorem. This theorem states that in response to white noise the stimulus STA is the input feature that best predicts when a spike occurs (Bryant and Segundo 1976; de Boer and Kuyper 1968). Thus, we binned well-isolated dendritic current spikes by amplitude and averaged the noise stimulus centered on each spike (Fig. 4B; see materials and methods).

Across the population, 23,820 isolated dendritic INL spikes were grouped into eight amplitude bins, with every cell contributing to each bin. The stimulus STA (Fig. 4B, black) revealed that dendritic spikes, regardless of amplitude, were on average preceded by similar fast-rising current injection waveforms. It should be noted that while the large-noise stimulus contained amplitudes exceeding 5 nA, the STA amplitude preceding a dendrite spike was far less (~1.5 nA). This is also seen in the example trace in Fig. 4A, where large instantaneous current injections (arrows) did not produce dendritic spikes. Thus, the STA results reveal that nonlinear dendritic spikes tend to follow a particular shape (or feature) in the dendritic input.

What stimulus feature determined the amplitude of the dendritic spike? Although the peak amplitude of the average current spike increased by over a factor of 10 (Fig. 4B, purple), the peak of the stimulus STA was surprisingly flat over the wide range of spike amplitudes (R = 0.41, P = 0.31; Fig. 4C, black). In comparison, the 10–90% rise time of the stimulus STA steadily increased as a function of spike amplitude (R = 0.93, P = 0.001; Fig. 4C, blue). Thus, small differences in the rise time of the stimulus STA, but not necessarily the amplitude, were correlated with dendritic current spike amplitude.

The STA results are important because they suggest that the amplitude of the dendritic spike informs the neuron about the shape of the injected dendritic input. A 10–90% stimulus rise time of ~4 ms tended to produce the largest dendritic spikes, while faster rise times produced smaller dendritic spikes. Thus, the nonlinear component of the dendritic signal processing is selective to a particular input feature.

Simple cascade model predicted dendritic spike timing and amplitude.

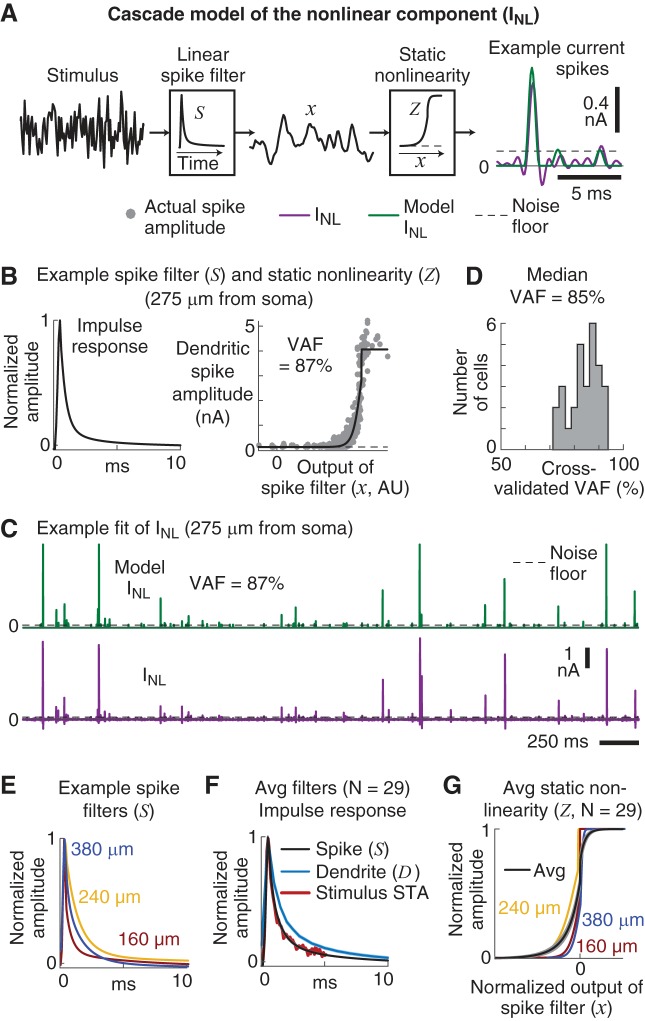

Although the stimulus STAs in Fig. 4B represent the shape of the stimulus waveform that best predicts the amplitude of a dendritic current spike, it does not reveal how good such a model would be. Thus, we constructed a common two-stage cascade model (Hunter and Korenberg 1986) of the dendritic nonlinear component to reproduce INL as a function of the stimulus input (Fig. 5A; see materials and methods).

Fig. 5.

Dendritic current spikes are described by a linear-nonlinear cascade model. A: the nonlinear dendritic current (INL, purple) was modeled as a linear filter (S, referred to as a spike filter) that was convolved with the stimulus, followed by a sigmoidal-shaped static nonlinearity (Z). See materials and methods for details. Shown is an example model current spike (green) that overlaps the actual current spike (purple). B: example impulse response function of the spike filter and static nonlinearity for a single neuron. For each neuron, the model was fit to isolated spikes with amplitudes ≥ the noise floor (gray points). The error in the fit is the difference between the actual spike amplitude and the static nonlinearity. For this neuron, the 2-fold cross-validated variance accounted for (VAF) by the model was 87%. C: extended example traces of the nonlinear dendritic current (INL) highlight the ability of the model (green) to reproduce the observed dendritic current spike times and amplitudes (purple). D: distribution of the 2-fold cross-validated VAF by the model of INL for all cells. E: example impulse response functions for spike filters from 3 dendritic locations. F: average impulse response function for the spike filter (S, black) and dendritic filter (D, blue) across all 29 recordings. Note that the average spike filter is the same as the average time-reversed STA of the stimulus for the largest dendritic spikes (red, replotted from Fig. 4B). G: average static nonlinearity (Z, black). To show the average shape of the static nonlinearity, for each neuron Z was normalized to its maximum amplitude and shifted so that its midpoint (x0 in Eq. 11) was aligned at 0 on the x-axis. Three example static nonlinearities are shown in color and correspond to the same dendritic locations shown in E. Shading is SE (no visible shading indicates SEs smaller than line widths).

The first stage of the model convolved the stimulus with a linear “spike” filter (S). The output of the spike filter (x) was then passed through a static nonlinearity (Z) that produced current spikes of variable amplitude. We optimized the model separately for each cell, using isolated dendritic spikes that were greater than or equal to the noise floor. Figure 5A shows a short example trace of the optimized model INL output (green) vs. the actual INL (purple).

A neuron’s optimized spike filter and static nonlinearity are shown in Fig. 5B, and the model INL output is shown in Fig. 5C on a longer timescale. For this dendritic recording, the model reproduced the spike amplitudes reasonably well (cross-validated VAF = 87%), which can be observed by how close the true dendritic spike amplitudes (gray points, Fig. 5B) are to the fitted static nonlinearity (Z, black sigmoid-shaped curve). Across all 29 recordings, the cascade model accounted for dendritic current spike time and amplitude with a median cross-validated VAF = 85% (Fig. 5D).

As illustrated by the example model fit in Fig. 5C, ~98% of the time INL was below the noise floor, and these data were not used to optimize the model. Thus, we used these nonspiking periods to further validate the model and found that “false-alarm” model current spikes (i.e., model spikes with no corresponding real dendritic spikes) were highly unlikely. For example, across all cells, the average rate of model false-alarm spikes with amplitudes at least 3 × noise floor was a negligible 0.01 ± 0.003 spikes/s. The high VAF and the low false-alarm spike rate of the model suggest that a functional cascade was reasonably good at capturing the nonlinear component of the dendritic signal processing.

The spike filter shape was fairly similar for different dendrite locations (impulse response functions for 3 example filters are shown in Fig. 5E). Across the population, the decay time of the spike filter’s impulse response function was not strongly linked to dendritic location (R = –0.36, P = 0.06, N = 29). The average spike filter (S; Fig. 5F, black) was slightly faster than the average dendritic filter (D; blue), with a 10–90% decay = 4.2 ± 0.3 ms (S) vs. 6.9 ± 0.4 ms (D) (P < 0.001, paired t-test). As predicted by the STA theorem, the shape of the average spike filter was identical to the stimulus STA of the largest spikes shown in Fig. 4B (replotted in Fig. 5F, red). The average static nonlinearity (Z; black, Fig. 5G) had a relatively consistent shape across cells in the form of a sigmoid that increased in slope as it approached the maximum spike amplitude. From visual inspection, the static nonlinearity did not appear to be dependent on dendritic location (3 examples are shown in color in Fig. 5G).

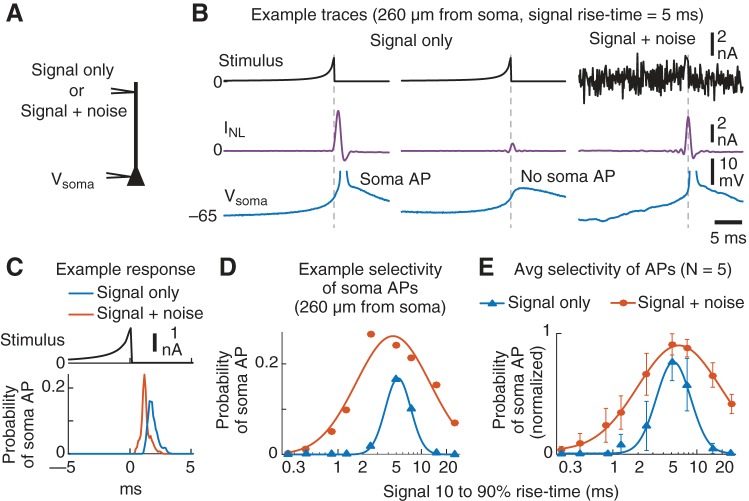

Dendritic current spikes were selective to rise time of stimulus.

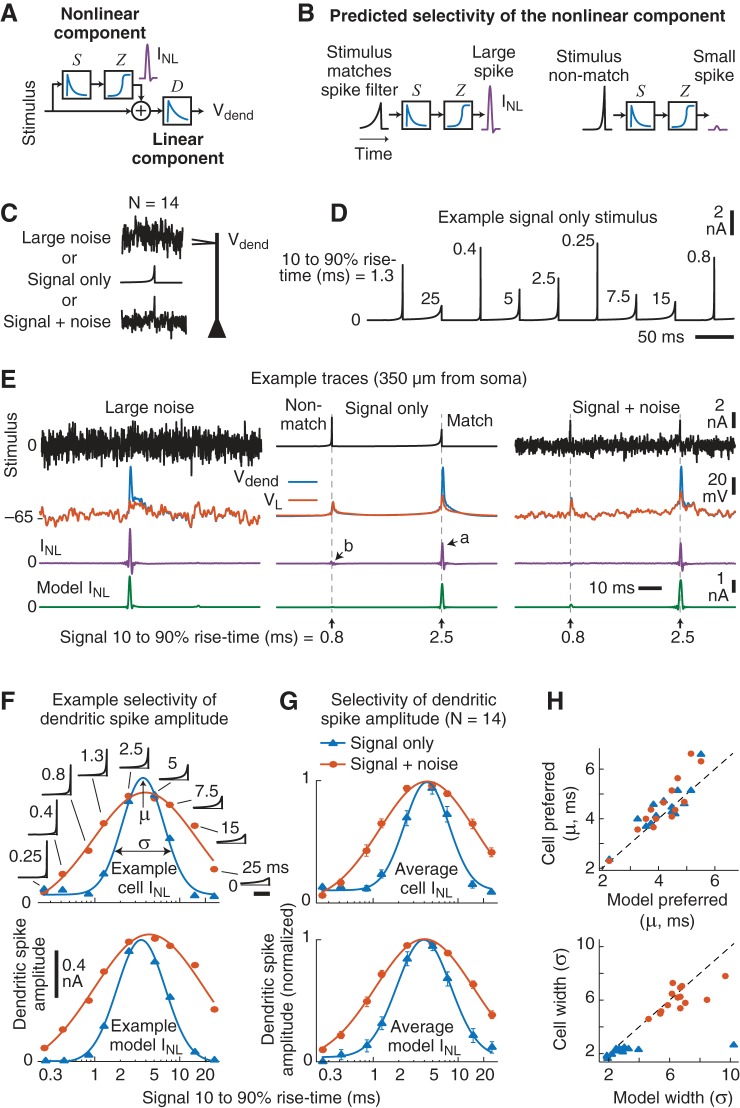

The results so far suggest a model of the dendritic membrane potential that is based on linear and nonlinear components (Fig. 6A). This model makes specific predictions that can be experimentally tested. For example, the cascade model of the nonlinear component (INL) predicts that dendritic current spike amplitudes will be selective to the shape of the input waveforms (Fig. 6B). Dendritic inputs that match the time-reversed shape of the spike filter (S), even in the presence of noise, will produce the largest-amplitude current spikes (Fig. 6B, left). Smaller dendritic spikes will correspond to inputs that are less similar to S (i.e., a nonmatched stimulus; Fig. 6B, right). Thus, we tested this hypothesis by experimentally measuring the selectivity of the dendritic nonlinearity using waveform stimuli that were very different from the white noise used to develop the cascade model of INL. We then compared the actual selectivity of the dendrite’s nonlinearity to that predicted by the model.

Fig. 6.

Dendritic current spike amplitude is selective for temporal features of the input. A: summary of the model for the linear and nonlinear components of the dendritic membrane potential. B: this model predicts that for equal-energy input signals arriving at the dendrite the linear spike filter (S) will produce a maximum response to a signal that is matched to its time-reversed shape (i.e., the impulse response function). This is usually referred to as the matched-filter theorem. C: 14 new experiments were performed using 3 dendritic current injections: 1) large white noise; 2) signal only—a random series of 9 different signals, presented every 50 ms, that were the time compressed (or stretched) versions of the time-reversed impulse response function of the spike filter (S; Fig. 5E); 3) signal+noise—the same “signal-only” pattern + half-amplitude white noise. D: example trace of the signal-only stimulus. The 10–90% rise time (ms) is shown next to each signal waveform. E: example responses of a neuron and model are shown for each stimulus condition. Note that dendritic current spikes (purple) are largest for the matched stimulus, even in the presence of noise. See text for references to arrows. F and G: example (F; same cell as E) and average (G) selectivity for the neuron (top) and model (bottom) dendritic current spikes. The peak of the average INL that occurred after each signal waveform was plotted as a function of the signal’s 10–90% rise time for the signal-only (blue) and signal+noise (orange) conditions. Note that the x-axis is a log scale and the solid lines are Gaussian fits. Insets in F show the signal waveforms injected into the dendrites (scale bar, 5 ms). Error bars are SE. H: the cell-by-cell preferred rise time (µ) and width (σ), as determined by the Gaussian fits, were well accounted for by the model, with the exception of a single outlier in the signal-only condition. As predicted by the cascade model of INL, the addition of noise increased the width of the selectivity but did not change the dendritic nonlinearity’s preferred rise time.

We alternated between three 1-min-long stimulus conditions (Fig. 6C). In the first condition we injected the same large-amplitude white noise as above. The second, “signal-only,” condition consisted of a randomized series of nine different equal-energy signals that were either time compressed or stretched versions of the average time-reversed spike filter (S) derived from the cascade model fits. A short example trace of the “signal-only” input is shown in Fig. 6D. For the third, “signal+noise,” condition, we presented the same equal-energy signals embedded in half-amplitude white noise. A prediction of the cascade model of INL is that additive noise should broaden the selectivity but not change the dendrite’s preferred input waveform. It should be noted that the waveforms were normalized to have equal energy so that only the rise time, and not the signal strength, varied between each of the nine waveforms (see materials and methods).

As highlighted by the example traces in Fig. 6E, center, a large dendritic current spike (purple, arrow a) occurred in response to a matched signal waveform with a rise time of 2.5 ms but not to a faster, nonmatched, input of 0.8 ms (arrow b). The same preferred signal also produced a large dendritic spike in the signal+noise condition (Fig. 6E, right). Note that dendritic spike amplitudes for the two signal conditions (Fig. 6E, center and right) tended to be smaller than spikes produced during the large noise (Fig. 6E, left). This was likely due to moderate Na+-channel inactivation, as the two “signal conditions” were no longer zero-mean stimuli.

To measure the selectivity of the dendritic nonlinearity, we plotted the average peak amplitude of the dendritic current spikes (INL) vs. the 10–90% rise time of the input stimulus (an example cell is shown in Fig. 6F, top). Across our 14 cells, the amplitude of the dendritic spike that followed each signal presentation was selective to the stimulus rise time. On average, the largest dendritic spikes occurred in response to signals with rise times between 4 and 5 ms (Fig. 6G, top).

The selectivity of the INL was approximately Gaussian as a function of the log rise time (solid lines in Fig. 6, F and G, are Gaussian fits). We used the mean (µ) and standard deviation (σ) of the fitted Gaussians to characterize the selectivity. There was a substantial broadening of the selectivity (σ) for the signal+noise (orange) vs. signal-only (blue) conditions (mean = 6.1 vs. 2.2, P < 0.0001, paired t-test, N = 14). In comparison, the preferred rise time (µ) was the same between the two conditions (mean = 4.5 and 4.4 ms, P = 0.64). Thus, the addition of noise broadened the selectivity of the dendritic nonlinearity, with no change in the preferred stimulus feature. Neither µ or σ was correlated with dendritic recording location (Pearson’s, P > 0.24 for both parameters and conditions).

The cascade model of INL reproduced the dendritic spikes observed in the two signal conditions (an example model trace is shown in Fig. 6E, green). The INL model used the same spike filter (S) estimated from the large-noise condition, but we refit the static nonlinearity (Z) to accommodate the reduced spike amplitude for the two signal conditions (see materials and methods). Comparison of the cascade model and cell selectivity curves (Fig. 6, F and G, bottom) revealed that the model captured much of the stimulus selectivity of the dendritic spikes and predicted the much wider selectivity in the presence of noise (orange vs. blue). A cell-by-cell comparison of the center (µ) and width (σ) of the selectivity curves further highlights the model’s good performance but also reveals a slight shift in both parameters (Fig. 6H). Model INL selectivity tended to be a little wider and centered on slightly faster rise times.

In summary, the nonlinear mechanism that generates dendritic Na+ spikes (INL) in mouse PT L5 neurons is selective to the input dynamics as predicted by the functional model (Fig. 6, A and B). Although the linear spike filter (S) captured the selectivity of the dendritic nonlinearity, changes in the static nonlinearity (Z) across conditions revealed an input-dependent reduction of the dendritic spike amplitude. Importantly, the injected waveforms further validated the cascade model of INL using stimuli that were dramatically different from the white noise originally used to derive the model’s spike filter (S). This is especially evident from the fact that the model accurately predicted how the addition of noise (signal+noise condition) would widen the selectivity without affecting the preferred input dynamics.

Most somatic APs followed dendritic current spikes.

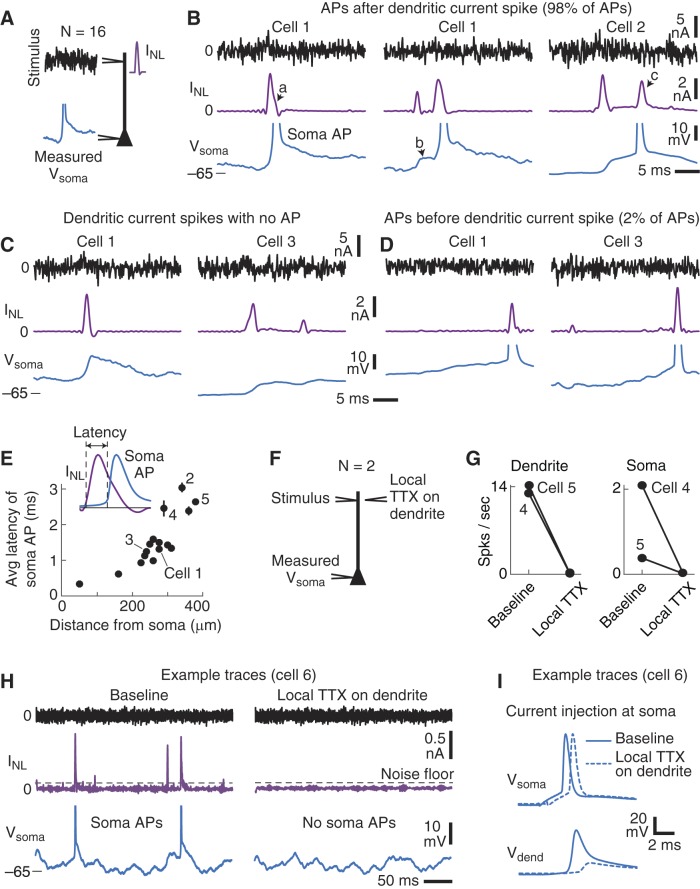

Thus far we have focused only on the dendritic nonlinearity (INL) and found that it was selective to a particular input shape as predicted by the functional model of INL. How does the dendritic nonlinear component contribute to the neuron’s ability to produce a somatic AP? Although it has been shown that dendritic Na+ spikes exert a strong influence on somatic APs (Gasparini and Magee 2006; Golding and Spruston 1998; Sivyer and Williams 2013; Smith et al. 2013; Stuart et al. 1997), our novel approach for isolating dendritic spikes using a noise stimulus and deconvolution warranted that we also examine this question in detail. In 16 experiments, we simultaneously recorded the somatic and dendritic membrane potential, using the large white-noise stimulus (Fig. 7A). In these recordings, the dendritic electrode location ranged from 50 to 380 μm from the soma (median 268 μm), with the majority of recordings centered on the nexus of the apical tuft (see Fig. 1A).

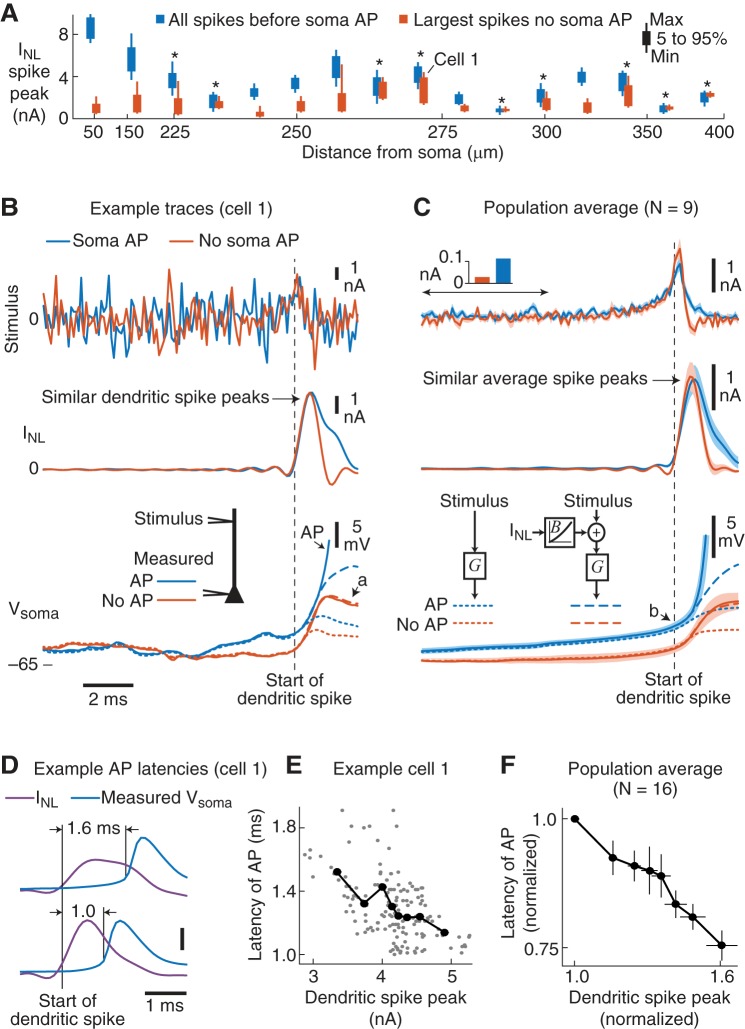

Fig. 7.

Dendritic spikes were linked to most somatic APs. A: simultaneous dendritic and soma recordings were performed with the large-noise stimulus. B: example traces (cells identified in E) of the stimulus (black), measured Vsoma (blue), and INL (purple). Left: a somatic AP that followed a large dendritic current spike. In some cases, the back-propagating APs tended to produce a slight bump that widened the dendritic spike (arrow a). Center: 2 smaller dendritic current spikes. The first current spike depolarized the somatic potential (arrow b), and the second spike was followed by the somatic AP. Right: a large dendritic current spike preceded the AP, which was then followed by a second, smaller, dendritic spike (arrow c). Across all experiments, ~98% of somatic APs followed a large dendritic current spike. C: examples of large dendritic spikes with no somatic AP. D: example traces of somatic APs that occurred before large dendritic current spikes. Presumably, these current spikes were the result of back-propagating APs. Only 2% of somatic APs did not follow a dendritic current spike. E: the average AP latency (measured from the start of the largest nearby dendritic current spike to the start of the somatic AP; see materials and methods) increased with the dendritic electrode distance from the soma. Cell numbers correspond to the example traces in other panels. Errors bars are SE. F: 2 experiments were performed while TTX was locally applied to the dendritic electrode and large-amplitude noise was injected at the dendrite. G: local application of TTX eliminated all dendritic current spikes and somatic APs in response to the noise stimulus injected at the dendrite. H: example traces before (left) and during (right) local TTX application at the dendritic electrode only. I: example somatic APs and dendritic potentials in response to current injections at the soma before (solid lines) and during (dashed lines) local TTX application to the dendritic electrode.

For each simultaneous somatic and dendritic recording, we extracted the dendritic nonlinear current (INL) from the dendritic membrane potential as described above. Across all cells, in response to the white-noise stimulus somatic APs occurred at a mean rate of 1.0 ± 0.9 (SD) spikes/s, much less than the ~25 spikes/s of the dendritic spikes. Note that the term “somatic AP” referrers to the somatic recording location and not the site of AP initiation, which has been shown to be in the axon (reviewed in Bean 2007; Kress and Mennerick 2009).

The higher rate of dendritic spikes vs. somatic APs agrees with previous in vitro observations that not all dendritic spikes are followed by APs (Gasparini and Magee 2006; Golding and Spruston 1998; Stuart et al. 1997) and that small dendritic spikes can occur at higher firing rates compared with somatic APs during in vivo or intact-circuit recordings (Sivyer and Williams 2013; Smith et al. 2013). However, our ratio of dendritic spike to AP firing rate was greater than that previously observed. Two potential reasons for this are that 1) the high variance in our noise stimulus produced more dendritic spikes and 2) the deconvolution method was able to resolve smaller dendritic spikes (just above the noise floor).

As illustrated in the example traces in Fig. 7B, dendritic current spikes (INL, purple) almost always preceded somatic APs (blue). Note that sometimes a small bump in the falling phase of the dendritic spike was observed, presumably due to AP back-propagation (Fig. 7B, left, arrow a). Somatic APs occasionally followed bursts of two or more smaller dendritic current spikes, where the first spike had a subthreshold depolarizing effect on the soma (Fig. 7B, center, arrow b). When the latency between the dendritic current spike and somatic AP was long, we typically observed isolated back-propagating spikes in the form of a second smaller INL spike immediately following the AP (Fig. 7B, right, arrow c). Of the 3,241 individual somatic APs recorded in our 16 experiments, ~98% followed a large dendritic current spike (see materials and methods). Many large dendritic current spikes, however, were not followed by somatic APs (Fig. 7C), and we focus our analyses on these spikes below.

Although our AP firing rates were lower than typically observed in vivo, ~15% of somatic APs were part of a burst containing two or more APs within a 25-ms window (data not shown). During these AP bursts, INL typically contained dendritic spikes riding on top of a small, sustained, inward current. This weak bursting in our data was revealed above by the small positive autocorrelation in INL (see Fig. 3A).

About 2% of the somatic APs (64 of 3,241 total APs recorded) were not preceded by a large dendritic spike (observed in 9 of 16 experiments). As shown by the example traces in Fig. 7D, large dendritic current spikes occasionally occurred just after the somatic AP. Presumably a large dendritic spike just after the AP reflected the back-propagation of the somatic AP into the dendrites.

Considering only dendritic spikes that immediately preceded somatic APs, we found that the average latency of the somatic AP increased as a function of dendritic location (Fig. 7E), which agrees with previous observations with nonnoise current injections (Stuart et al. 1997). To further confirm that somatic APs were causally linked to the dendritic nonlinearities, in two experiments we applied TTX locally at the dendrite while recording the somatic and dendritic responses (Fig. 7F). Locally blocking Na+ channels at the dendrite eliminated all dendritic spikes and somatic APs in response to the dendritic noise input (Fig. 7G). The example traces show that TTX reduced INL below the noise floor threshold for a dendritic spike (Fig. 7H). For both experiments, however, a brief somatic current injection still produced a somatic AP in the presence of the local TTX on the dendrites but attenuated the back-propagation of the AP into the dendrites (Fig. 7I). Note that the somatic AP threshold in response to somatic current injection was unchanged by the TTX puff in the dendrite (cell 1 threshold went from −52.6 mV to –51.3 mV and cell 2 threshold went from –52.7 mV to –52.5 mV, baseline vs. TTX, respectively).

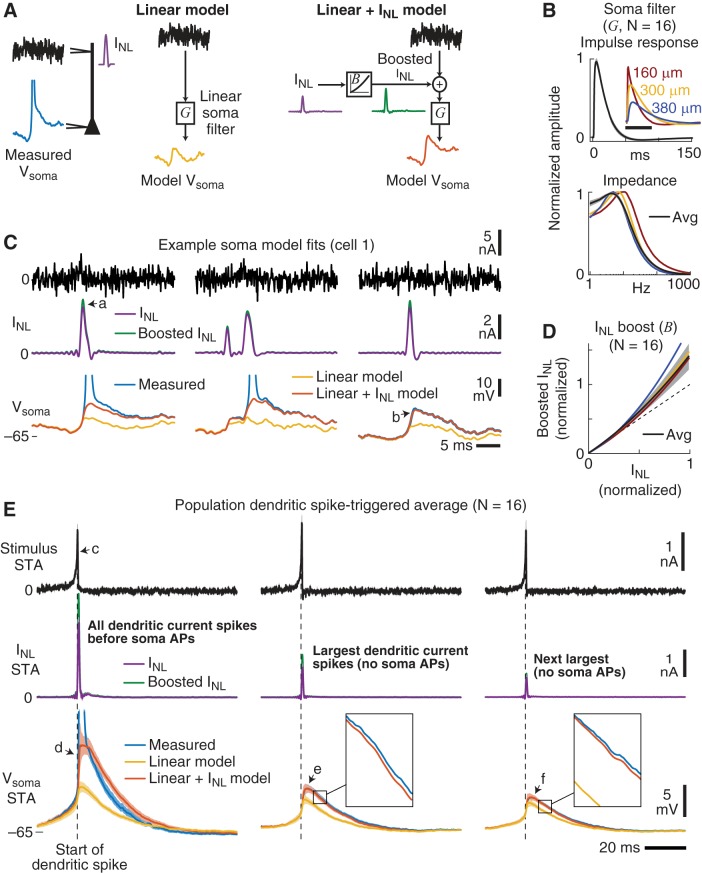

Functional model revealed that soma linearly integrated boosted dendritic spikes.

In response to the noise stimulus, a vast majority of the nonlinear dendritic current spikes (~25 spikes/s) were not associated with somatic APs (~1 spike/s). What was the relationship between the dendritic spike and the soma membrane potential when there was no somatic AP? For example, were dendritic spikes integrated at the soma in the same way as the stimulus? Or was the soma potential affected by additional nonlinearities not captured by the dendritic INL?

To answer these questions, we constructed two functional models of the subthreshold somatic potential (Fig. 8A): 1) a linear model that only used the stimulus as the input and 2) a linear model that also included the nonlinear dendritic current INL. The first model convolved the stimulus with a linear soma filter (G) to reproduce the somatic potential (yellow). The second model convolved the stimulus + a boosted version of INL (green) with G to produce Vsoma (orange).

Fig. 8.

A functional model reveals that dendritic spikes were linearly integrated by the soma. A: 2 functional models were constructed to describe the somatic membrane response (Vsoma) to the injection of white-noise current at the dendrite. In the first “linear model” a linear filter (G, referred to as a soma filter) was convolved with the stimulus current to produce Vsoma (yellow). For the second “linear + INL model” the stimulus + a boosted INL (green) was convolved with the same linear filter (G) to produce Vsoma (orange). The boost to INL was modeled with a static nonlinearity (B) that simply scaled the INL amplitude. Note that these models were designed to reproduce the subthreshold fluctuations in Vsoma (not somatic APs). B: average and 3 example linear somatic filters (G). Top: mean normalized impulse response function (black). Inset: 3 example filters for different dendritic input locations (to compare individual filters, the amplitudes were not normalized; scale bar is 50 ms). Bottom: mean normalized impedance amplitude profile (black) and example filters. Soma filters (G) were the same for both soma models shown in A. C: example traces showing the model fits (same cell 1 from Fig. 7). For this particular neuron, INL was only weakly boosted (green vs. purple) before arriving at the soma (arrow a). Before a dendritic spike occurred, Vsoma was well described by the linear filter model (G) convolved with the stimulus (yellow vs. blue). In the presence of dendritic spikes, convolving G with the stimulus + boosted INL (green) accounted for Vsoma (orange vs. blue, arrow b), except during a somatic AP. D: the boosting of INL arriving at the soma (B) was modeled as a quadratic function. The amount of boosting depended on the dendritic spike amplitude and was on average 40% for the largest dendritic spikes (black). Dashed line is unity slope, and the red, yellow, and blue curves are the single-cell examples corresponding to the recording locations shown in B. E: population average dendritic spike-triggered averages (STAs) of the stimulus (black), INL (purple), boosted INL arriving at the soma (green), and the measured somatic membrane potentials (blue). Also shown are the STAs of the 2 model fits of the somatic membrane potential (yellow and orange). Left: STAs using dendritic current spikes that were followed by a somatic AP. Center: STAs using the largest dendritic current spikes not associated with a soma AP. Right: STAs using the next largest current dendritic spikes not associated with a soma AP. The same total number of dendritic current spikes contributed to each of the 3 STA groups. Insets show the average linear + INL model fit (orange) on a zoomed scale (box is 5 ms × 2 mV). Shading is SE. See main text for arrow references.

Because INL is a measure of the local nonlinearity in the dendrite, the boost function (B) allowed the effect of INL on the soma to vary. For example, nonlinearities activated in other parts of the dendrites, during the propagation of the dendritic spike, or in the soma itself, could boost the effect that dendritic spikes had on the soma membrane potential. Thus, the boost function captured the fact that somatic depolarization due to a dendritic current spike was larger than that predicted by the spike size at the dendrites. It is important to emphasize, however, that the boost function (B) did not change the dynamics of INL but only scaled its magnitude as illustrated in Fig. 8A (green vs. purple spikes).

We optimized the soma filter (G) and found that it was essentially identical between the two models. The average soma filter (black) was more low pass compared with the dendritic (D) and spike filters (S) but had a similar peak in its frequency response ~8 Hz (Fig. 8B). As shown by the three example filters in Fig. 8B, the soma filters became more attenuating, both for amplitude and frequency, as a function of dendritic location. For the linear model of the somatic membrane potential, convolving the somatic filter (G) with the stimulus did a good job of accounting for Vsoma (yellow, Fig. 8C), except for periods after a dendritic current spike.

Including INL improved the model’s ability to mimic the subthreshold soma potential after a dendritic spike. Optimizing the boost function revealed an average increase in the effect that INL had on the soma potential (Fig. 8D). This increase was greater for larger-amplitude dendritic spikes, with an average maximum boost to the dendritic spikes of 40 ± 18% (P < 0.0001, N = 16, 1-sided t-test). The maximal boosting was not strongly related to dendritic location (Pearson’s R = 0.39, P = 0.13). Example traces of the boosted INL arriving at the soma filter (G) are shown in Fig. 8C (green, arrow a), which were smaller than average for this particular neuron.

Importantly, convolving the soma filter (G) with the stimulus + boosted INL yielded a model Vsoma (orange traces, Fig. 8C) that reproduced the measured somatic membrane potential before and after dendritic spikes (arrow b) but not during somatic APs. For example, excluding the 20 ms following the start of a somatic AP (which was ~2% of the data), the linear + INL model predicted Vsoma with a median VAF = 99% (range 96–100%, N = 16).

To further quantify the interplay between the stimulus, dendritic spikes, and somatic response, we computed population STAs aligned to the start of the dendritic spikes (Fig. 8E). We binned dendritic current spikes into three groups: 1) dendritic spikes that preceded a somatic AP (Fig. 8E, left), 2) the largest dendritic spikes with no somatic APs (Fig. 8E, center), and 3) the next largest dendritic spikes with no soma AP (Fig. 8E, right). All three STAs were computed with the same number of dendritic current spikes.

Across 16 experiments, the stimulus STA before a somatic AP (arrow c, Fig. 8E) revealed the same preferred input dynamics (compare to the STAs in Fig. 4B). At the start of an AP, large dendritic current spikes produced a substantial increase in Vsoma for the linear + INL model (Fig. 8E, orange, arrow d), but the model tended to overestimate the somatic depolarization immediately after the AP. This overestimation was likely due to the repolarization of the somatic potential by somatic nonlinearities not captured in the dendritic nonlinearity INL. In comparison, when there was no somatic AP, the STA of the linear + INL model of Vsoma (Fig. 8E, orange) overlapped the STA of the measured somatic potential (Fig. 8E, arrows e and f; insets show expanded fits). Before the start of the dendritic spike, both models of Vsoma predicted the somatic membrane potential equally well.

When no somatic AP occurred, the functional model of Vsoma showed that slightly boosted dendritic spikes were linearly integrated by the soma in a similar manner as the stimulus. The modeling of the somatic potential, however, does not reveal the mechanism by which dendritic spikes were linked to somatic APs. We addressed this next by examining why some large dendritic current spikes did not produce somatic APs, while other large dendritic spikes did produce APs.

Link between dendritic spike and somatic AP depended on stimulus history.

Why did some large dendritic current spikes result in somatic APs, while other similarly sized dendritic spikes did not? Previous studies have demonstrated that somatic APs do not always follow dendritic spikes (Gasparini and Magee 2006; Golding and Spruston 1998; Palmer et al. 2014; Sivyer and Williams 2013; Smith et al. 2013; Stuart et al. 1997). We took advantage of the fact that our dendritic spikes varied in amplitude to quantify this link with our functional models of Vsoma. Figure 9A shows the 5–95% range of the dendritic current spike amplitude for our 16 paired recordings as a function of distance from the soma; two groups of spike amplitudes are shown, those that were followed by soma APs (blue) and the largest current spikes not followed by a soma AP (orange). Note that these are the same data used to construct the STAs in Fig. 8E, left and center, and for many experiments there was a substantial overlap in the spike amplitudes between APs and no APs.

Fig. 9.