Abstract

Cholesterol-protein interactions are essential for the architectural organization of cell membranes and for lipid metabolism. While cholesterol-sensing motifs in transmembrane proteins have been identified, little is known about cholesterol recognition by soluble proteins. We reviewed the structural characteristics of binding sites for cholesterol and cholesterol sulfate from crystallographic structures available in the Protein Data Bank. This analysis unveiled key features of cholesterol-binding sites that are present in either all or the majority of sites: i) the cholesterol molecule is generally positioned between protein domains that have an organized secondary structure; ii) the cholesterol hydroxyl/sulfo group is often partnered by Asn, Gln, and/or Tyr, while the hydrophobic part of cholesterol interacts with Leu, Ile, Val, and/or Phe; iii) cholesterol hydrogen-bonding partners are often found on α-helices, while amino acids that interact with cholesterol’s hydrophobic core have a slight preference for β-strands and secondary structure-lacking protein areas; iv) the steroid’s C21 and C26 constitute the “hot spots” most often seen for steroid-protein hydrophobic interactions; v) common “cold spots” are C8–C10, C13, and C17, at which contacts with the proteins were not detected. Several common features we identified for soluble protein-steroid interaction appear evolutionarily conserved.

Keywords: lipids, receptors, sterols, X-ray crystallography, cholesterol binding site, cholesterol-protein interaction

Cholesterol is a key structural component of membranes in animal cells (1). Indeed, cholesterol maintains the basic architecture of plasma membranes; in the general bulky phospholipid bilayer, the insertion of cholesterol molecules introduces the lipid order phase, which is essential for membrane organization and proper protein function (2, 3). Moreover, cholesterol molecules usually arrange in vertical domains that span the whole bilayer leading to the formation of lipid “rafts,” which are critical for cell signaling and protein sorting and trafficking (4). Cholesterol also serves as a metabolic precursor of other physiologically relevant steroids, such as steroid hormones and bile acids (5, 6).

The key structural and functional roles of cholesterol are underscored by the wide variety of defects that result from abnormal levels of cholesterol in the body. Cholesterol availability to the central nervous system is critical for myelin formation, brain maturation, and synapse formation and function (7, 8). Thus, the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, characterized by a marked reduction in tissue cholesterol, includes a wide variety of developmental abnormalities that range from physical malformations to developmental delay and mental retardation (9). In adult humans, low total cholesterol levels positively correlate with increased mortality due to respiratory, digestive disease, or traumatic events (10). In the hospital setting, hypocholesterolemia is frequently seen after major surgery or during serious trauma, severe infections or prolonged hypovolemic shock, with very low cholesterol levels being predictors of mortality in critically ill patients (11–14). In turn, excessive cholesterol levels, such as in familial or acquired hypercholesterolemia, lead to atherosclerosis and to a dramatically increased incidence of stroke and cardiovascular mortality (15–17). High cholesterol levels also correlate with progression of Alzheimer’s disease and contribute to development of ocular disorders (18, 19).

The multitude of pathophysiological conditions triggered by, or coincidental with, abnormal cholesterol levels fueled scientific studies on cholesterol modulation of protein function. This modulation includes control of cell motility and organization of the actin cytoskeleton (20), regulation of interactions between bacterial or viral (such as HIV) pathogens and mammalian cells (21, 22), and modulation of receptor and ion channel function (23–26), even drastic modification of ion channel’s pharmacology (27–29). While the mechanisms underlying cholesterol modulation of protein function are still under debate, two major theories have been recognized. The first is based on the ability of cholesterol to modify the physical properties of biological membranes, leading to the formation of the lipid order phase. Indeed, plasma membranes of mammalian cells contain large amounts of cholesterol (up to 50 mol%), which allows cholesterol to play a major role as a structural lipid (1). Thus, cholesterol may interact with membrane phospholipids and promote tight packing of the phospholipid acyl chains (so called “condensing effect” of cholesterol) (30–32). As a result, the presence of cholesterol increases lateral pressure within the membrane and introduces “packing stress” (33). The increase in lateral pressure upon cholesterol incorporation into the phospholipid bilayer has been proposed as a major mechanism for cholesterol to modulate protein function (33–35). The second theory, however, proposes that cholesterol modifies protein function by direct steroid binding to the protein target. Therefore, a large body of work has been dedicated to identifying protein motifs that could bind cholesterol molecules.

The chemical structure of cholesterol presents several key elements. First, the core of the molecule is formed by a tetracyclic (rings A–D) ring system (Fig. 1A). A double bond in ring B between carbon atoms 5 and 6 confers rigidity to the molecule. The hydrophobic tetracyclic ring system is complemented by a rather flexible iso-octyl chain. Thus, the only hydrophilic feature of cholesterol is a β-hydroxyl group at C3. Noteworthy, cholesterol is an asymmetric molecule: its α-face corresponds to a smooth, rather planar, surface, while the β-face is a surface with rough edges (methyl groups) (36).

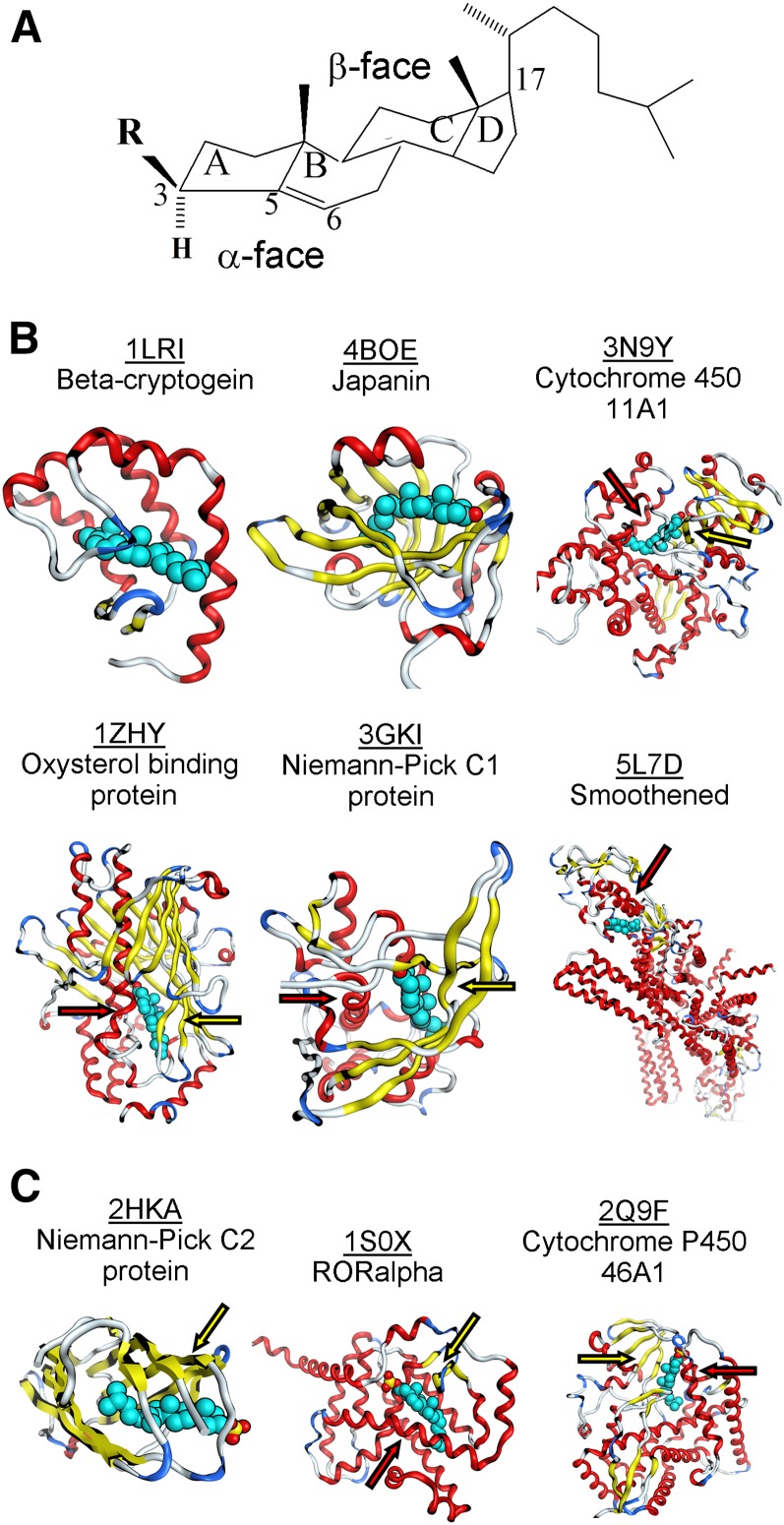

Fig. 1.

Cholesterol binding sites in crystallized proteins. A: Molecular structure of cholesterol (R: hydroxyl) and cholesterol sulfate (R: sulfate). B: Overview of crystallized cholesterol-protein complexes. C: Overview of crystallized cholesterol sulfate-protein complexes. In all cases, the cholesterol molecule is in teal blue; hydrogen atoms are not shown. In (B, C), arrows that point at β-strands flanking the cholesterol β-face are in yellow whereas arrows that point at α-helixes flanking the cholesterol α-face are in red.

In transmembrane protein segments, the cholesterol recognition amino acid consensus (CRAC) motif has been identified (37, 38). CRAC is a relatively short, linear motif with the sequence (Leu/Val)-X1–5-(Tyr)-X1–5-(Lys/Arg), where X represents any amino acid. Lys or Arg, or even Tyr, are expected to hydrogen bond with cholesterol; the Tyr aromatic ring structure stabilizes cholesterol’s polycyclic core by “stacking” against it, while Leu and Val interact with the steroid’s hydrophobic iso-octyl chain. Thus, the CRAC motif represents an oriented binding site for cholesterol, with nonpolar amino acids residing at the N terminus of the motif and a polar residue(s) at the C terminus. Cholesterol binding by CRAC motifs within protein transmembrane areas and in juxta-membrane segments has been well-documented (39, 40). However, the cholesterol-sequestering ability of CRAC motifs that are present in the sequence of nontransmembrane protein segments has been questioned repeatedly (38, 40, 41).

More recently, “reversed” CRAC motifs, in which amino acids appear in a sequence that is directionally opposite to that in CRACs, have been described and termed “CARCs” (40). In addition, several other cholesterol binding areas on protein transmembrane segments have been reported. In particular, a systematic NMR study utilizing Ala-scanning mutagenesis has revealed cholesterol-binding properties for the GXXXG motif in the C99 protein (42). The geometry of cholesterol-binding to GXXXG and flanking areas remains speculative. However, mutations of thirteen amino acids scattered along GXXXG itself or its vicinity either totally ablate or significantly abolish cholesterol binding (42).

A more precise picture of cholesterol binding to a transmembrane protein arises from an X-ray structure of the human β2-adrenergic receptor bound to cholesterol (43): although the binding area does not contain conventional cholesterol-recognition motifs, it does include basic Arg, aromatic Trp, and aliphatic Leu/Val, a structural triad that is found in CRAC motifs. Thus, although CRAC (and CARC) motifs per se might actually have low predictive value for identifying cholesterol-binding sites, such motifs embody a general idea on the chemical forces that enable cholesterol binding to transmembrane sections of the proteins, e.g., hydrogen bonding with the cholesterol hydroxyl group and hydrophobic interactions with the cholesterol hydrophobic core (40).

While there is some consensus on the structural basis of cholesterol interactions with transmembrane proteins, common structural features characteristic of cholesterol binding to soluble proteins remain largely undetermined. Collectively, cholesterol-binding areas in soluble proteins are usually represented by protein hydrophobic cavities that shield the steroid from an aqueous environment and also enable cholesterol release to the membrane or a partner protein (38). An example is the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein, which includes the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein-related lipid transfer (StART) domain (44). This domain results from an evolutionarily conserved sequence of >200 aminoacids that form an ensemble of α-helixes and β-sheets to accommodate a variety of lipid species. Two StAR protein isoforms that are most specific for cholesterol (StAR-D1 and StAR-D3) do contain CRACs, yet the role of these CRAC domains in cholesterol binding/transport is unclear. In synthesis, common protein secondary structural elements and amino acids that partner with the cholesterol molecule in soluble proteins remain largely unknown. Thus, the goal of our work is to contribute to cover this gap in knowledge.

ANALYSIS OF CRYSTALLOGRAPHIC PROTEIN-CHOLESTEROL STRUCTURES

We performed searches of the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database (pdb.org) for protein structures that contained cholesterol as a bound ligand. Our search yielded a total of nine structures, which had resolution and isothermic B-factor ranging from 1.45 to 3.2 Å (all structures) and from 19.5 to 76.23 Å2 (six structures), respectively. PDB files were downloaded into Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software (Chemical Computing Group, Canada) and visualized using a built-in function in MOE. The Protein Contacts algorithm in MOE was used to define ligand-binding pockets with cut-off distances of 4.5 Å for both hydrophobic and ionic interactions. Histidine was treated as a basic amino acid while methionine was treated as hydrophobic. Five PDB entries describing cholesterol-protein complexes were analyzed (Fig. 1B). The shape of cholesterol-binding sites can be generally described as a pocket (invagination). In some instances, this description can be extended to either a more secluded and rather straight tunnel (i.e., the binding site is almost fully covered around its long axis by the protein structure) or as a bean-like cavity. The latter suits the flexibility of the steroid lateral chain. In general, cholesterol-binding sites are solvent-accessible (45), with water molecules reported in the vicinity and/or inside cholesterol-binding sites in several crystal structures (46, 47). Using distance measurement routine based on the receptor surface map in MOE, we estimated averaged length of the cholesterol-binding pocket along steroid axis being approximately 23 Å with the diameter of the pocket averaging 11–12 Å. The key amino acid contact partners of the cholesterol molecule are summarized in Table 1.

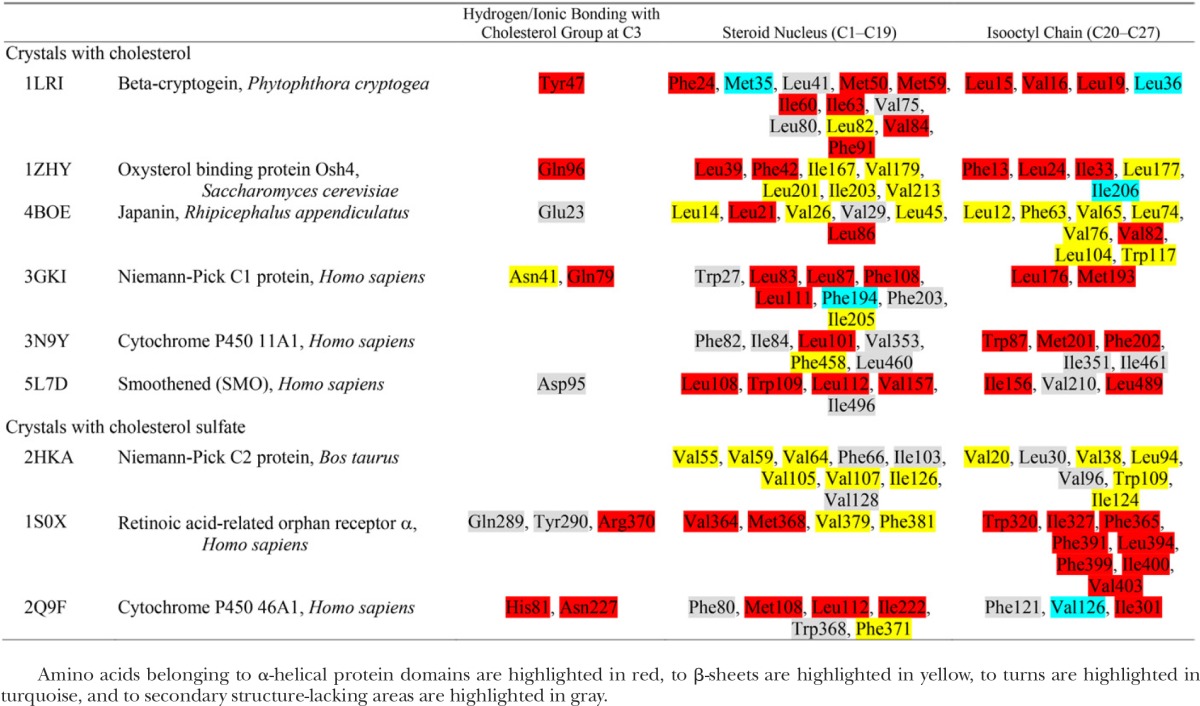

TABLE 1.

Amino acid contacts for cholesterol/cholesterol sulfate in binding sites on crystallized proteins

Amino acids belonging to α-helical protein domains are highlighted in red, to β-sheets are highlighted in yellow, to turns are highlighted in turquoise, and to secondary structure-lacking areas are highlighted in gray.

Beta-cryptogein belongs to the elicitin family and constitutes a small, extracellular, highly toxic protein that is secreted by pathogenic microorganisms and promotes leaf necrosis of the host plant (48). Cryptogeins have been reported to have steroid-shuttling ability (49). The crystal structure of β-cryptogein from Phytophtora cryptogea in complex with cholesterol (PDB entry 1LRI) reveals cholesterol’s position inside a lax, hydrophobic, and elongated tunnel that is almost fully covered around the long axis by several α-helices and a small fraction of β-strands. The cholesterol-binding tunnel is rather nonspecific, as it can accommodate a large variety of 3β-hydroxy sterols (49). Cholesterol is positioned inside the tunnel with its α-face oriented toward the β-strands and its β-face facing the α-helical structure. Cholesterol binding involves hydrogen bonding with a Tyr located in the α-helical protein domain and with water. Cholesterol tetracyclic nucleus and its iso-octyl chain are flanked by a multitude of amino acids (several Leu, Ile, Val, Met, and Phe). In addition to cholesterol, this β-cryptogein site binds ergosterol and fatty acids (50, 51).

Oxysterol binding protein, Osh4, is a soluble cytosolic protein. Osh4 and related proteins are highly conserved from yeast to humans. The crystallographic structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Osh4 bound to cholesterol (PDB entry 1ZHY) is one of many that depict steroid/oxysterol binding to this protein (46). In complex with cholesterol, Osh4 provides a hydrophobic pocket (i.e., invagination) flanked by a system of β-strands at one side, and two α-helical structures at the other. Cholesterol is positioned inside the pocket with its β-face oriented toward the β-strands and its α-face facing α-helical structures. The 3β-hydroxyl of cholesterol forms hydrogen bonds with a Gln located in the α-helical domain and with water. The tetracyclic ring system and the iso-octyl tail of cholesterol are partnered with several Leu, Ile, Val, and Phe residues. Besides cholesterol, the site can also accommodate ergosterol, 7- and 25-hydroxycholesterols (46). The ability to accommodate cholesterol derivatives oxygenated whether at the steroid nucleus or at the lateral chain documents the pocket’s flexibility, which may be explained by its topology: it contains a wide lateral opening that very likely reduces overall rigidity.

The tick protein, japanin, was first described in salivary glands of Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. It belongs to the lipocalin family of the hydrophobic molecule transporters. This soluble protein exerts an immunomodulatory role by targeting and selectively reprogramming human dendritic cells (52). The crystal structure of japanin-cholesterol complex (PDB entry 4BOE) shows a hydrophobic bean-shaped cleft that is mostly formed by β-strands, with short α-helical segments flanking the cholesterol molecule (53). Cholesterol is positioned inside the cleft with its α-face oriented toward β-strands and its β-face facing the α-helical structure. Cholesterol’s 3β-hydroxyl forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone amide N provided by Glu. The hydrophobic partners of cholesterol tetracyclic rings and iso-octyl chain are several Leu and Val residues, with a single Trp or Phe also contributing.

Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1) protein is present in lysosomal membranes and represents one of the key molecules in cholesterol exit from the lysosome. NPC1 protein has 13 transmembrane helices, with a soluble N terminus protruding into the lysosome lumen (54–56). The N-terminal domain contains a cholesterol-binding site, which is responsible for capturing cholesterol from NPC2, an NPC1 partner, for further shuttling cholesterol out of the lysosome by partitioning it into the lysosome membrane (55). The crystal of the NPC1 N-terminal domain bound to cholesterol (PDB entry 3GKI) shows cholesterol positioned inside a hydrophobic bean-shaped cleft that is flanked by α-helices at one side and β-strands at the other. Cholesterol is positioned inside the cleft with its β-face oriented toward β-strands and its α-face facing α-helical structures. Cholesterol’s 3β-hydroxyl forms hydrogen bonds with Asn and Gln located in the β-strand and α-helix, respectively. In turn, the tetracyclic region of cholesterol is tightly held by hydrophobic amino acids, which include Leu, Phe, Trp, and Met. Additional amino acids help to form the cholesterol-binding cleft. The binding cleft is surrounding the cholesterol iso-octyl chain, however, loses its tight contour and opens into the solvent. The site enables accommodation of 25-hydroxycholesterol while prevents cholesterol derivatives with modifications at C3 (cholesterol sulfate and epicholesterol) from binding (55).

Cytochrome P450 (P450scc or CYP11A1) is found only in vertebrates and serves as a key enzyme in steroidogenesis by metabolizing cholesterol and a wide array of other sterols and their derivatives (57). Mitochondrial CYP11A1 is bound to an inner mitochondrial membrane with the large soluble protein core protruding into the mitochondrial matrix (PDB entry 3N9Y) (47). The cholesterol molecule is buried inside a hydrophobic elongated pocket that is formed by several β-strands and α-helices that shield the steroid from the aqueous medium. Cholesterol is positioned inside the pocket with its β-face oriented toward β-strands and its α-face facing the α-helical structure. The 3β-hydroxyl of cholesterol does not interact directly with CYP11A1 amino acids but binds to two water molecules that are part of a hydrogen-bond network formed by additional water molecules and the polar residues Tyr, Asn and Gln. Many amino acids (Leu, Ile, Val, Phe, and Trp) conform a tightly fitted pocket to accommodate the hydrophobic part of cholesterol. The site does not discriminate between cholesterol and 20- or 22-hydroxycholesterol, with their binding mode being strikingly similar to that of cholesterol (47).

The smoothened receptor (SMO) mediates signal transduction in the hedgehog pathway (58). The SMO structure includes a hepta-helical transmembrane domain and an extracellular cysteine-rich domain that are connected by the juxtamembrane linker domain (PDB entry 5L7D) (45). The cysteine-rich domain contains the cholesterol-binding site, which contributes to SMO-mediated signaling (45). Within this site, the cholesterol molecule is positioned inside an elongated pocket between α-helices while the cholesterol iso-octyl chain is flanked by a β-sheet (45). Notably, the order of the cholesterol molecule (as measured by the lower B-factor) is higher than that of the protein backbone, an expected result considering that cholesterol’s steroid nucleus is rather rigid (45). The 3β-hydroxyl of cholesterol forms a hydrogen bond with Asp, this bond being part of a larger hydrogen bond network formed by Asp, Tyr and Trp (45). The steroid hydrogen-bonding Asp seems to be located within a protein region that lacks a defined secondary structure. In contrast, the hydrophobic partners of cholesterol preferentially reside in α-helices (Table 1). With the exception of Trp, all these partners are Leu, Val, and Ile. SMO’s cholesterol-binding site can also accommodate 20(S)-hydroxycholesterol (59).

ANALYSIS OF CRYSTALLOGRAPHIC STRUCTURES CONTAINING CHOLESTEROL SULFATE-PROTEIN COMPLEXES

The analysis of the few available crystal structures of cholesterol may not be enough to define common features of cholesterol sites in soluble proteins. Thus, we also studied cholesterol sulfate. This is a cholesterol derivative in which the 3β-hydroxyl is substituted by a sulfate group. Although this substitution diminishes the overall hydrophobicity of the molecule, the remaining structural features are identical to those of cholesterol. From a biological standpoint, cholesterol sulfate has been extensively recognized as one of the most important sulfonated steroids. Higher levels of cholesterol sulfate were found in the plasma of patients with liver cirrhosis and hypercholesterolemia (60) while atherosclerosis has been linked to cholesterol sulfate deficiency (61). Under normal physiology, cholesterol sulfate plays a critical role in platelet adhesion and keratinocyte differentiation. At the molecular level, this steroid regulates the activity of serine proteases and, in a rather selective manner, of protein kinase C isoforms. Several PDB entries describe cholesterol sulfate-protein complexes. We analyzed three complexes found in the PDB database, their topology being depicted in Fig. 1C. Averaged volume of the site was estimated at 2,745 ± 256 Å3. The key features of cholesterol sulfate binding sites are summarized in Table 1.

NPC2 is a soluble lysosomal protein that plays a major role in cholesterol intracellular trafficking. NPC2 deficiency is characterized by a life-threatening accumulation of cholesterol in lysosomes (62). The crystal structure of the NPC2 complex with cholesterol sulfate (PDB entry 2HKA) reveals that the steroid molecule is positioned inside a hydrophobic tunnel that is deeply buried between protein β-strands (63). The sulfo-group of the sterol does not form hydrogen bond(s) with NPC2. This is a unique case, as polar groups at C3 of the steroid are expected to have a hydrogen-binding amino acid partner (Table 1). The cholesterol sulfo-group, however, protrudes into the aqueous medium which substitutes for polar partners usually provided by a protein. As in crystal structures that contained cholesterol, the cholesterol sulfate tetracyclic ring system is partnered by Val, Phe, Leu, Ile and Trp. Interestingly, this site can also accommodate cholesterol, the latter having lower affinity when compared with cholesterol sulfate (63). Besides cholesterol and cholesterol sulfate, the NPC2 site binds a wide variety of animal and plant sterols. Binding of fatty acids, bile acids or glycosphingolipids, however, could not be observed (64). The lack of hydrogen-bonding protein partners for the steroid may contribute to the relatively lax specificity of the site toward cholesterol derivatives at C3: indeed, cholesteryl acetate and 5α-cholestan-3-one bind to the site (63). Unexpectedly, thiocholesterol, cholesteryl bromide and long chain cholesteryl esters cannot bind (63). It has been proposed that the failure of binding studies was a consequence of the differential solubility of different lipid species in a given solvent, and to their differential ability to form multimers in hydrophilic media (63).

The retinoic acid-related orphan receptor α (RORalpha) is an orphan member of the subfamily one of nuclear hormone receptors. ROR proteins serve as critical regulators of many physiological processes that occur during embryonic development and in adulthood, including regulation of circadian rhythms (65, 66). Cholesterol and cholesterol sulfate were proposed as RORalpha ligands, with cholesterol sulfate having an affinity for this receptor higher than that of cholesterol (67). Conceivably, the stronger hydrogen-bonding ability of cholesterol sulfate leads to its higher affinity to cholesterol-binding sites, as observed for both ROR and NPC2 (see above). In the crystal structure of steroid-RORalpha complex (PDB entry 1S0X), cholesterol sulfate is positioned inside a bean-shaped hydrophobic cleft formed mostly by α-helices, yet a few short β-strand domains are also present. Cholesterol sulfate is positioned inside the cleft with the steroid β-face oriented toward the β-strands and the α-face facing the α-helical structure. Positioning of cholesterol sulfate inside the cleft is very similar to cholesterol; however, cholesterol sulfate is pulled out a little toward the more hydrophilic side of the pocket. The 3-sulfo group hydrogen bonds with the backbone amide N of Tyr and Gln and with a sidechain N of Arg. The hydrophobic part of the molecule is partnered by Ile, Phe, Val, Trp, and Met.

Cytochrome P450 46A1 initiates the major pathway for cholesterol removal from the brain via conversion of cholesterol to 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol (68). The protein has a short N-terminal transmembrane region, with the protein core being soluble. Cytochrome P450 46A1’s crystallographic structure in complex with cholesterol (PDB entry 2Q9F) shows cholesterol inside a bean-shaped protein cavity that shields the steroid from an aqueous medium by layers of α-helices and β-strands (69). Cholesterol is positioned inside the cavity with its β-face oriented toward β-strands and its α-face facing the α-helical structure. As presented for RORalpha (see above), cholesterol’s 3β-hydroxyl forms hydrogen bonds with backbone amide N atoms, the latter provided by His and Asn. The hydrophobic part of the cholesterol molecule is partnered by Leu, Ile, Phe and other amino acids (Table 1). Besides cholesterol, the protein site is expected to bind 7-dehydrocholesterol and desmosterol, as oxidation of these steroids by P450 46A1 has been documented (70).

COMPARISON OF STEROID-PROTEIN CONTACT MAPS FOR CHOLESTEROL VERSUS CHOLESTEROL SULFATE

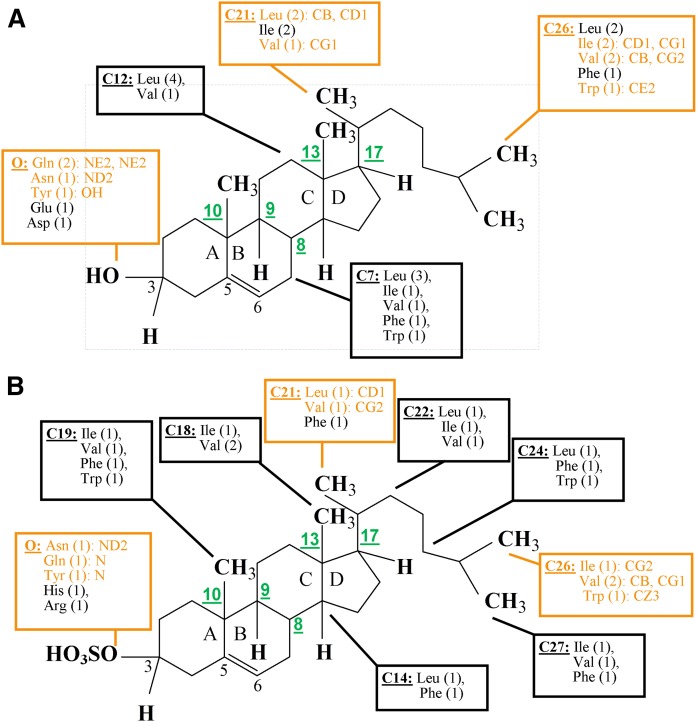

Substitution of the hydroxyl at C3 with a sulfate does not disrupt the general topology of the steroid molecule. Thus, cholesterol-sulfate binding sites follow the general layout of cholesterol’s binding sites (Fig. 1B, C) (67). The sulfate, however, carries a much larger charge than the hydroxyl, which results in differences in sterol-protein interactions at ring A between the two steroids. Based on computationally assessed steroid-protein contacts for each crystallographic structure, we created steroid-protein interaction maps for cholesterol and cholesterol sulfate. Several “hot spots,” i.e., C atoms that represent contact points with proteins in the majority of crystals, were identified (Fig. 2): C7, C12, C21, and C26 for cholesterol, and C14, C18, C19, C21, C22, C24, C26, and C27 for cholesterol sulfate. The larger number of hot spots for cholesterol sulfate is likely explained by the smaller number of crystallographic structures analyzed (three for cholesterol sulfate vs. six for cholesterol). Despite the larger number of hot spots in the cholesterol sulfate structures, the contact maps of cholesterol and cholesterol sulfate are rather similar, with C21 and C26 constituting hot spots for both steroids. In addition, maps for both steroids show that hydrophobic steroid-protein contacts are formed almost exclusively by Leu, Val and Ile, with occasional appearance of Phe or Trp. As expected, there are more diverse and dense ionic interactions at the sulfo-group of cholesterol sulfate when compared with those at the hydroxyl of cholesterol. Nevertheless, the steroid-interacting amino acids Asn, Gln, and Tyr are common. Although steroid hydroxyl and sulfate groups have preference toward N atoms of the amino acids to form hydrogen bonding, steroid C21 and C26 do not show strong preference for a particular atom even when steroid molecules form contacts with the same amino acid (Fig. 2). Finally, cold spots were also detected: neither cholesterol nor cholesterol sulfate formed contacts with the proteins at steroid C atoms C8–C10, C13, or C17. Overall, the protein contact maps of cholesterol sulfate are similar to those of cholesterol.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the contact maps for cholesterol (A) and cholesterol sulfate (B) interactions with soluble proteins. Contact maps for each crystal structure were created using the “Protein Contacts” function in MOE software with cut-off distances for the hydrophobic and ionic interactions set at 4.5 Å. A total of six crystal structures for cholesterol and three for cholesterol sulfate with proteins were analyzed. Schemes reflect contacts that were detected in at least four structures for cholesterol and at least two structures for cholesterol sulfate. Amino acid residues that form contacts at each carbon atom of the steroid are listed within boxes. The frequency of appearance is indicated in parenthesis. For example, “C7: Leu (3)” means that Leu formed contact with C7 on three occasions. Within a given structure, several amino acids may form contact with the same carbon atom of the steroid. Thus, the sum of frequencies at which amino acids that appear at a particular contact point may exceed the total number of complexes in which a contact between protein and steroid was detected. Contact points (i.e., hot spots) that are common for protein interactions with both cholesterol and cholesterol sulfate are shown in orange; amino acid atoms that form contact with the steroid are listed; carbon atoms that represent common cold spots (see text) are numbered in green.

COMMON STRUCTURAL FEATURES OF CHOLESTEROL/CHOLESTEROL SULFATE BINDING SITES IN SOLUBLE PROTEINS

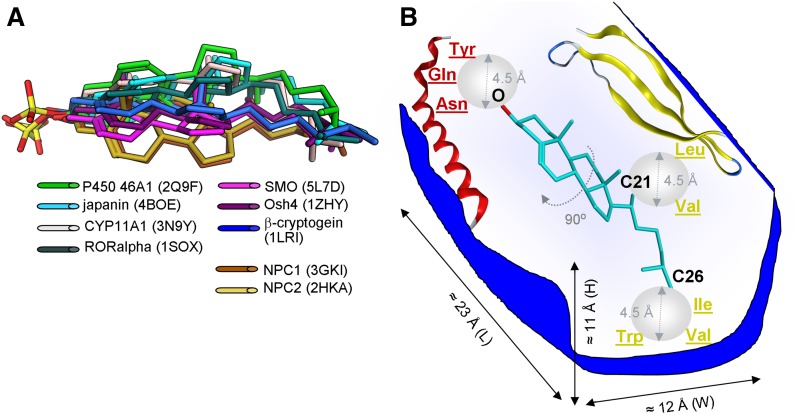

Superposition of cholesterol and cholesterol sulfate bound to crystallized proteins based on the three hot spots identified in Fig. 2 showed the clustering of steroid molecules into three conformational groups, which differed in the rotation angle of the steroid nucleus along the C3–C17 axis (Fig. 3A). Although the rotation of the molecule may reach 90°, data still show a fairly consistent conformational profile of steroid ligands bound to the crystallized proteins.

Fig. 3.

Common design of cholesterol-binding sites in soluble proteins. A: Superposition of cholesterol and cholesterol sulfate bound to crystallized proteins is based on the three hot spots identified in Fig. 2 (e.g., oxygen at steroid C3, and carbon atoms C21 and C26). B: Proposed design for the cholesterol-binding site in crystallized soluble proteins, which includes common structural features that define cholesterol and cholesterol sulfate binding. Spheres in light gray emphasize the cut-off distance at which steroid-binding amino acids where determined.

Based on the visualization of the crystal structures of soluble proteins in complexes with cholesterol/cholesterol sulfate, we were able to detect the steroid binding site’s general features, which were present in the majority of the structures (Table 2). First, the steroid molecule is always positioned inside a protein cavity/pocket to minimize the exposure of the hydrophobic steroid molecule to the aqueous environment (Fig. 3B). This finding is key to understanding steroid interaction with soluble proteins. While maintenance of a large hydrophobic cavity in an aqueous environment would be energetically unfavorable, it is conceivable that some rearrangement of protein structure occurs in presence of steroid ligand. Indeed, the evidence favors the “induced fit” mode of cholesterol and cholesterol sulfate binding to soluble proteins. In particular, rearrangement of protein domains upon cholesterol binding has been reported for β-cryptogein and SMO protein (45, 51). In NPC2, the sterol-accommodating hydrophobic cleft is small in the absence of cholesterol. However, significant reorientation of several amino acid side chains is observed upon sterol binding, with the entire site being thus molded around the hydrocarbon portion of the sterol to enable efficient binding (63). The malleability of these sites may account for their accommodation of various ligands, such as steroid derivatives, and even fatty acids (50). Yet, malleability is limited, and accommodation of ligands other than that of steroid family is not always possible (63).

TABLE 2.

Frequency of appearance of the proposed common structural features among cholesterol/cholesterol sulfate binding sites on crystallized soluble proteins

| Feature of Steroid-Binding Protein Site | PDB Entry | Frequency of Appearance | ||||||||

| 1LRI | 1ZHY | 4BOE | 3GKI | 3N9Y | 5L7D | 2HKA | 1S0X | 2Q9F | ||

| Protein pocket | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9/9 |

| Avoidance of secondary structure-lacking areas | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9/9 |

| Steroid α-face facing an α-helix | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6/9 | |||

| Steroid β-face facing a β-strand | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6/9 | |||

| Hydrogen-bonding with Asn, Gln, or Tyr | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5/9 | ||||

| Hydrogen bonding amino acid is on an α-helix | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5/9 | ||||

| Hydrophobic interactions with Leu, Ile, Val, or Phe | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9/9 |

| Steroid-protein contacts at C21 and C26 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5/9 | ||||

| Hydrogen bonding with O at C3 moiety | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/9 | ||

| Lack of contacts with the protein at steroid C8–C10, C13, and C17 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9/9 |

Second, the steroid-accommodating pocket is often formed by ordered domains (whether α-helices or β-strands). Thus, the steroid avoids binding to protein areas that lack a secondary structure. Secondary structure-lacking areas have a high degree of flexibility (71). Thus, it is conceivable that these areas: i) are unable to provide a lasting, concerted group of amino acids to capture and retain the bound steroid; and/or ii) present the risk of “exposing” the steroid molecule to the aqueous solvent. Interestingly, in the majority of structures (with the exception of NPC2 and smoothened proteins) the steroid is positioned inside the hydrophobic protein pocket that is flanked by α-helices on one side and β-strands on the other (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, the rough β-face of the steroid is preferentially facing β-strands while the smoother α-face prefers α-helices. The basis of this phenomenon remains unclear. However, it has to be taken into account that polar hydroxyl or sulfate groups are oriented toward the β-face of the steroid. Having the β-face of cholesterol oriented toward β-strands may help to avoid electrostatic repulsion between the steroid polar group and the dipole of the α-helix. Consistent with this, the more polar sulfo group (in cholesterol sulfate) always faces a β-strand structure while the less polar hydroxyl (in cholesterol) faces this structure in most cases, yet is still able to face α-helices (e.g., β-cryptogenin and japanin).

Third, Tyr, Gln, Asn, Glu, Arg, and His were all identified as possible partners for accommodating steroid polar groups at C3 (Table 1). However, only five out of nine protein-steroid complexes included hydrogen bonding, whether directly with Asn, Gln and Tyr or via coordination through water molecules. Asn, Gln and Tyr have polar side chains and share neutrality on the scale of side chain acidity/basicity. Remarkably, only three other amino acids (Cys, Ser and Thr) meet this combination. These amino acids differ from Asn, Gln, and Tyr by having a much higher hydropathy index, i.e., a parameter indicative of the prevalence of hydrophobic versus hydrophilic properties of the amino acids (72). Thus, the scale of hydropathy indexes [Cys (2.5) > Thr (−0.7) > Ser (−0.8) > Tyr (−1.3) Gln (−3.5) = Asn (−3.5)] inversely reflects the frequency at which these amino acids have been reported to interact with the steroid polar group at C3 in crystallized soluble proteins: Cys, Thr and Ser are never seen; Tyr is occasionally reported; Asn and Gln are often reported. Overall, it appears that the physicochemical properties of amino acid partners of the steroid group at C3 are similar to those of the cholesterol molecule as a whole: neutral and polar. Remarkably, when either a ligand (in the case of cholesterol sulfate) or a receptor (in the case of Glu serving as a hydrogen bond partner in japanin) becomes acidic, the ligand hydrogen bonds with the backbone amide N atoms rather than with the side chain of the amino acid. However, Asn and Gln are also found among these hydrogen-bonding amino acids (e.g., RORalpha and CYP46A1). Interestingly, in five out of nine structures, amino acids that provide hydrogen bonding at the moiety of C3 are found on the α-helical domains (Table 1). Although the polar α-face of cholesterol points away from the α-helices, the latter are still able to provide amino acids that satisfy geometric criteria (distance and angle) for hydrogen bonding with cholesterol.

Fourth, Ile, Val, Leu, and Phe are consistently found partners of the hydrophobic part of steroid molecules (Table 1). This pattern is not surprising, considering that the four amino acids are at the top of the hydropathy scale, with hydropathy indexes of 4.5, 4.2, 3.8, and 2.8, respectively (72). In contrast to the hydrogen bond partners, there is no pattern regarding the location of hydrophobic residues that interact with the hydrophobic core of the steroid: α-helices, β-strands, and even secondary structure-lacking protein areas provide hydrophobic amino acids with similar frequency of appearance. Overall, there is a slight predominance of β-strands combined with secondary structure-lacking areas (Table 1).

Finally, we detected both “hot” and “cold” spots for proteins to contact the steroid: C21 and C26 constitute the most often hot spots for steroid-protein hydrophobic interactions while O atoms at the C3 moiety often provide bonding partners for steroid-protein hydrogen bonding (Fig. 3B). In turn, common cold spots are presented by the steroid C8–C10, C13, and C17, at which contacts with the protein were not detected. The rather lax design of cholesterol-binding sites, with only one hot spot for possible hydrogen bonding complemented by hydrophobic interactions within a malleable protein pocket, allows binding of a diverse group of cholesterol derivatives into the sites within soluble proteins.

CHOLESTEROL/CHOLESTEROL SULFATE BINDING SITES IN SOLUBLE PROTEINS: FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS

A strategy similar to that followed here to identify steroid binding sites in soluble proteins (computational modeling based on crystallographic data) has also been successful in identifying ion channel protein binding by ethanol and related n-alkanols. Ethanol is a promiscuous, low-affinity ligand that interacts with both soluble and membrane proteins at aqueous concentrations in the millimolar range (73, 74). With these characteristics, many conventional methodologies, such as radioligand binding or spectroscopy, are of little use to identify ethanol-binding sites. However, computational visualization and analysis of four crystal structures of alcohol-recognition proteins that were available at the time unveiled critical common features to alcohol-sensing sites in proteins (75). These common features were used by us as a template for the discovery of an ethanol-sensing site in the calcium/voltage-gated potassium channel of large conductance (BK), an ionotropic receptor that controls numerous physiological functions and constitutes a major target of alcohol actions in the body (74, 76).

From a ligand perspective, cholesterol offers challenges similar to those posed by ethanol. Although the cholesterol molecule is more complex, cholesterol modulation of protein function is, as ethanol’s, rather promiscuous: hundreds of cholesterol-sensing proteins that participate in cholesterol modulation of cell biology have been discovered (40, 77). Moreover, for some of these proteins, cholesterol effective concentrations are in the millimolar range (78, 79), this affinity being similar to that of ethanol. As found for ethanol, cholesterol-binding sites are expected to reside in nontransmembrane regions of the protein (76, 80). A first attempt to identify a cholesterol-sensing motif succeeded when the CRAC motif was advanced. This motif includes amino acids that are common among previously known cholesterol-sensing proteins (81). Moreover, up to day, CRAC motifs are widely used as a fast-screen approach in the search for putative cholesterol-sensing regions within transmembrane proteins. Our current analysis reveals that, in contrast to the rather short, linear CRAC motifs, cholesterol-binding sites in soluble proteins are generally large structures, with complex 3D organization that requires the assembly of several structural elements (α-helices and β-strands), leading to the formation of cholesterol-binding cavities/tunnels. This complexity for cholesterol-peptide interaction in soluble proteins is somewhat predictable, as the steroid molecule has to be separated from direct contact with the aqueous medium by a hydrophobic protein shield.

A more detailed comparison of cholesterol-binding sites in soluble proteins with CRACs reveals further differences: our study identified residues in soluble proteins that conform a “signature” theme: Asn, Gln and Tyr form ionic/hydrogen bonds with the sterol in five out of nine crystal structures while Leu, Ile, Val and Phe constitute the majority of amino acid partners for the hydrophobic steroid nucleus and iso-octyl chain in all the crystal structures evaluated. Overall, our profiling of amino acids shows little resemblance (if any) with the CRAC “signature” motif, which always contains a central Tyr, in addition to Arg and Lys (39). The only overlapping amino acids between cholesterol-binding sites in soluble proteins and cholesterol-binding sites in protein transmembrane segments (i.e., CRACs) are aliphatic Leu and Val. As mentioned above, these amino acids have one of the highest hydropathy indexes (72). Thus, it is conceivable that they represent a “must have” hydrophobic element within sites that bind such a lipophilic molecule as cholesterol.

Finally, we found no correlation between CRAC number/distribution in soluble proteins and their ability to bind cholesterol. For instance, β-cryptogein does not have a CRAC motif whereas the CYP11A1 protein sequence contains six CRACs. This outcome buttresses the idea that the predictive value of CRAC domains for the presence of cholesterol-binding sites in soluble proteins has to be taken with caution. This conclusion is in agreement with previously reported difficulties in using the CRAC motif sequence as a predictor of cholesterol-binding ability by membrane proteins themselves and proteins in general (38, 40, 41). It has been shown that the genome of Streptococcus agalactiae (GenBank accession number NC 004368) encodes 2,094 proteins (41). The majority of these proteins have no relation to cholesterol homeostasis, yet it has been estimated that the CRAC motif appears as often as every 112 aminoaacids (41). Similar examples were shown for proteomes of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli (41). Therefore, the mere occurrence of CRAC domains is not indicative of a cholesterol-binding site. Furthermore, we also showed that lack of CRAC motifs does not preclude soluble proteins from binding cholesterol (Table 1). Whether our newly identified common structural features of cholesterol-binding sites in soluble proteins (Table 2) hold predictive value remains to be established.

CONCLUSIONS

We identified common structural features of cholesterol/cholesterol sulfate binding sites in soluble proteins. The proteins under analysis cover a large evolutionary span (from fungi to Homo sapiens), a wide array of functions (cytotoxicity, cholesterol-shuttling, catalysis, etc.), and exhibit varied topology (cytosolic, extracellular, lysosomal, etc.). Thus, the overall structural design of cholesterol-binding sites in soluble proteins is highly conserved. The common structural features herein identified can be used as a tool to narrow down the extensive pool of putative cholesterol-binding sites that usually results from computational analysis of protein structures. Thus, our findings should facilitate the discovery of cholesterol-sensing areas and a rational for drug design to target pathological conditions related to disruption of cholesterol homeostasis.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- CRAC

- cholesterol recognition amino acid consensus

- CYP11A1

- cytochrome P450 (P450scc)

- MOE

- Molecular Operating Environment

- NPC1

- Niemann-Pick C1

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- RORalpha

- retinoic acid-related orphan receptor α SMO, smoothened receptor

- StAR

- steroidogenic acute regulatory

- StART

- steroidogenic acute regulatory protein-related lipid transfer

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AA023764 (A.N.B.) and R01 HL104631 (A.M.D.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dopico A. M., and Tigyi G. J.. 2007. A glance at the structural and functional diversity of membrane lipids. Methods Mol. Biol. 400: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinn P. J., and Wolf C.. 2009. The liquid-ordered phase in membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1788: 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonnino S., and Prinetti A.. 2013. Membrane domains and the “lipid raft” concept. Curr. Med. Chem. 20: 4–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown D. A., and London E.. 1998. Functions of lipids rafts in biological membranes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 14: 111–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nes W. D. 2011. Biosynthesis of cholesterol and other sterols. Chem. Rev. 111: 6423–6451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiang J. Y. 2013. Bile acid metabolism and signaling. Compr. Physiol. 3: 1191–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfrieger F. W. 2003. Role of cholesterol in synapse formation and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1610: 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saher G., Brügger B., Lappe-Siefke C., Möbius W., Tozawa R., Wehr M. C., Wieland F., Ishibashi S., and Nave K. A.. 2005. High cholesterol level is essential for myelin membrane growth. Nat. Neurosci. 8: 468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowaczyk M. J., and Irons M. B.. 2012. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: phenotype, natural history, and epidemiology. Am. J. Med. Genet. C. Semin. Med. Genet. 160C: 250–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs D. 1992. Report of the conference on low blood cholesterol: mortality associations. Circulation. 86: 1046–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunham C. M., Fealk M. H., and Sever W. E. III. 2003. Following severe injury, hypocholesterolemia improves with convalescence but persists with organ failure or onset of infection. Crit. Care. 7: R145–R153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guimarães S. M., Lima E. Q., Cipullo J. P., Lobo S. M., and Burdmann E. A.. 2008. Low insulin-like growth factor-1 and hypocholesterolemia as mortality predictors in acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit. Crit. Care Med. 36: 3165–3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vyroubal P., Chiarla C., Giovannini I., Hyspler R., Ticha A., Hrnciarikova D., and Zadak Z.. 2008. Hypocholesterolemia in clinically serious conditions–review. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 152: 181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stachon A., Böning A., Weisser H., Laczkovics A., Skipka G., and Krieg M.. 2000. Prognostic significance of low serum cholesterol after cardiothoracic surgery. Clin. Chem. 46: 1114–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saini H. K., Arneja A. S., and Dhalla N. S.. 2004. Role of cholesterol in cardiovascular dysfunction. Can. J. Cardiol. 20: 333–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Navi B. B., and Segal A. Z.. 2009. The role of cholesterol and statins in stroke. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 11: 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouhairie V. E., and Goldberg A. C.. 2016. Familial hypercholesterolemia. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 45: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng X. F., Yu J. T., Wang H. F., Tan M. S., Wang C., Tan C. C., and Tan L.. 2014. Midlife vascular risk factors and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 42: 1295–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Sayyad H. I., Elmansi A. A., and Bakr E. H.. 2015. Hypercholesterolemia-induced ocular disorder: ameliorating role of phytotherapy. Nutrition. 31: 1307–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramprasad O. G., Srinivas G., Rao K. S., Joshi P., Thiery J. P., Dufour S., and Pande G.. 2007. Changes in cholesterol levels in the plasma membrane modulate cell signaling and regulate cell adhesion and migration on fibronectin. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 64: 199–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goluszko P., and Nowicki B.. 2005. Membrane cholesterol: a crucial molecule affecting interactions of microbial pathogens with mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 73: 7791–7796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroeder C. 2010. Cholesterol-binding viral proteins in virus entry and morphogenesis. Subcell. Biochem. 51: 77–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gimpl G., Burger K., and Fahrenholz F.. 1997. Cholesterol as modulator of receptor function. Biochemistry. 36: 10959–10974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Addona G. H., Sandermann H. Jr., Kloczewiak M. A., and Miller K. W.. 2003. Low chemical specificity of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor sterol activation site. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1609: 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levitan I., Fang Y., Rosenhouse-Dantsker A., and Romanenko V.. 2010. Cholesterol and ion channels. Subcell. Biochem. 51: 509–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dopico A. M., Bukiya A. N., and Singh A. K.. 2012. Large conductance, calcium- and voltage-gated potassium (BK) channels: regulation by cholesterol. Pharmacol. Ther. 135: 133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sooksawate T., and Simmonds M. A.. 2001. Influence of membrane cholesterol on modulation of the GABA(A) receptor by neuroactive steroids and other potentiators. Br. J. Pharmacol. 134: 1303–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crowley J.J., Treistman S.N., and Dopico A.M.. 2003. Cholesterol antagonizes ethanol potentiation of human brain BKCa channels reconstituted into phospholipid bilayers. Mol. Pharmacol. 64: 365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bukiya A. N., Vaithianathan T., Kuntamallappanavar G., Asuncion-Chin M., and Dopico A. M.. 2011. Smooth muscle cholesterol enables BK β1 subunit-mediated channel inhibition and subsequent vasoconstriction evoked by alcohol. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31: 2410–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohvo-Rekilä H., Ramstedt B., Leppimäki P., and Slotte J. P.. 2002. Cholesterol interactions with phospholipids in membranes. Prog. Lipid Res. 41: 66–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McConnell H. M., and Radhakrishnan A.. 2003. Condensed complexes of cholesterol and phospholipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1610: 159–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hung W. C., Lee M. T., Chen F. Y., and Huang H. W.. 2007. The condensing effect of cholesterol in lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 92: 3960–3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cantor R. S. 1997. The lateral pressure profile in membranes: a physical mechanism of general anesthesia. Biochemistry. 36: 2339–2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang H. M., Reitstetter R., Mason R. P., and Gruener R.. 1995. Attenuation of channel kinetics and conductance by cholesterol: an interpretation using structural stress as a unifying concept. J. Membr. Biol. 143: 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bezrukov S. 2000. Functional consequences of lipid packing stress. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 5: 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pine S. 1987. 5th edition Misler K. S. and Tenney S., editors. McGraw-Hill, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li H., Yao Z., Degenhardt B., Teper G., and Papadopoulos V.. 2001. Cholesterol binding at the cholesterol recognition/ interaction amino acid consensus (CRAC) of the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor and inhibition of steroidogenesis by an HIV TAT-CRAC peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98: 1267–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Epand R. M. 2006. Cholesterol and the interaction of proteins with membrane domains. Prog. Lipid Res. 45: 279–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Epand R. F., Thomas A., Brasseur R., Vishwanathan S. A., Hunter E., and Epand R. M.. 2006. Juxtamembrane protein segments that contribute to recruitment of cholesterol into domains. Biochemistry. 45: 6105–6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fantini J., and Barrantes F. J.. 2013. How cholesterol interacts with membrane proteins: an exploration of cholesterol-binding sites including CRAC, CARC, and tilted domains. Front. Physiol. 4: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer M. 2004. Cholesterol and the activity of bacterial toxins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 238: 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barrett P. J., Song Y., Van Horn W. D., Hustedt E. J., Schafer J. M., Hadziselimovic A., Beel A. J., and Sanders C. R.. 2012. The amyloid precursor protein has a flexible transmembrane domain and binds cholesterol. Science. 336: 1168–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanson M. A., Cherezov V., Griffith M. T., Roth C. B., Jaakola V. P., Chien E. Y., Velasquez J., Kuhn P., and Stevens R. C.. 2008. A specific cholesterol binding site is established by the 2.8 A structure of the human beta2-adrenergic receptor. Structure. 16: 897–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reitz J., Gehrig-Burger K., Strauss J. F. III, and Gimpl G.. 2008. Cholesterol interaction with the related steroidogenic acute regulatory lipid-transfer (START) domains of StAR (STARD1) and MLN64 (STARD3). FEBS J. 275: 1790–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Byrne E. F., Sircar R., Miller P. S., Hedger G., Luchetti G., Nachtergaele S., Tully M. D., Mydock-McGrane L., Covey D. F., Rambo R. P., et al. 2016. Structural basis of Smoothened regulation by its extracellular domains. Nature. 535: 517–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Im Y. J., Raychaudhuri S., Prinz W. A., and Hurley J. H.. 2005. Structural mechanism for sterol sensing and transport by OSBP-related proteins. Nature. 437: 154–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strushkevich N., MacKenzie F., Cherkesova T., Grabovec I., Usanov S., and Park H. W.. 2011. Structural basis for pregnenolone biosynthesis by the mitochondrial monooxygenase system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108: 10139–10143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu L. M. 1995. Elicitins from Phytophthora and basic resistance in tobacco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92: 4088–4094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lascombe M. B., Ponchet M., Venard P., Milat M. L., Blein J. P., and Prangé T.. 2002. The 1.45 Å resolution structure of the cryptogein-cholesterol complex: a close-up view of a sterol carrier protein (SCP) active site. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58: 1442–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boissy G., O’Donohue M., Gaudemer O., Perez V., Pernollet J. C., and Brunie S.. 1999. The 2.1 A structure of an elicitin-ergosterol complex: a recent addition to the sterol carrier protein family. Protein Sci. 8: 1191–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dobes P., Kmunícek J., Mikes V., and Damborský J.. 2004. Binding of fatty acids to beta-cryptogein: quantitative structure-activity relationships and design of selective protein mutants. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 44: 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Preston S. G., Majtán J., Kouremenou C., Rysnik O., Burger L. F., Cabezas Cruz A., Chiong Guzman M., Nunn M. A., Paesen G. C., Nuttall P. A., et al. 2013. Novel immunomodulators from hard ticks selectively reprogram human dendritic cell responses. PLoS Pathog. 9: e1003450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roversi P., Johnson S., Preston S., Austyn J. M., Nuttall P., and Lea S. M.. 2014. Cholesterol binding by the tick Lipocalin Japanin. PDB. DOI: 10.2210/pdb4boe/pdb. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davies J. P., and Ioannou Y. A.. 2000. Topological analysis of Niemann-Pick C1 protein reveals that the membrane orientation of the putative sterol-sensing domain is identical to those of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase and sterol regulatory element binding protein cleavage-activating protein. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 24367–24374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kwon H. J., Abi-Mosleh L., Wang M. L., Deisenhofer J., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S., and Infante R. E.. 2009. Structure of N-terminal domain of NPC1 reveals distinct subdomains for binding and transfer of cholesterol. Cell. 137: 1213–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gong X., Qian H., Zhou X., Wu J., Wan T., Cao P., Huang W., Zhao X., Wang X., Wang P., et al. 2016. Structural insights into the Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1)-mediated cholesterol transfer and Ebola infection. Cell. 165: 1467–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Slominski A. T., Li W., Kim T. K., Semak I., Wang J., Zjawiony J. K., and Tuckey R. C.. 2015. Novel activities of CYP11A1 and their potential physiological significance. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 151: 25–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCabe J. M., and Leahy D. J.. 2015. Smoothened goes molecular: new pieces in the hedgehog signaling puzzle. J. Biol. Chem. 290: 3500–3507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang P., Nedelcu D., Watanabe M., Jao C., Kim Y., Liu J., and Salic A.. 2016. Cellular cholesterol directly activates smoothened in hedgehog signaling. Cell. 166: 1176–1187.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tamasawa N., Tamasawa A., and Takebe K.. 1993. Higher levels of plasma cholesterol sulfate in patients with liver cirrhosis and hypercholesterolemia. Lipids. 28: 833–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seneff S., Davidson R. M., Lauritzen A., Samsel A., and Wainwright G.. 2015. A novel hypothesis for atherosclerosis as a cholesterol sulfate deficiency syndrome. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 12: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Storch J., and Xu Z.. 2009. Niemann–Pick C2 (NPC2) and intracellular cholesterol trafficking. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1791: 671–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu S., Benoff B., Liou H-L., Lobel P., and Stock A. M.. 2007. Structural basis of sterol binding by NPC2, a lysosomal protein deficient in Niemann-Pick type C2 disease. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 23525–23531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liou H. L., Dixit S. S., Xu S., Tint G. S., Stock A. M., and Lobel P.. 2006. NPC2, the protein deficient in Niemann-Pick C2 disease, consists of multiple glycoforms that bind a variety of sterols. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 36710–36723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jetten A. M., Kurebayashi S., and Ueda E.. 2001. The ROR nuclear orphan receptor subfamily: critical regulators of multiple biological processes. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 69: 205–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sundar I. K., Yao H., Sellix M. T., and Rahman I.. 2015. Circadian molecular clock in lung pathophysiology. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 309: L1056–L1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kallen J., Schlaeppi J. M., Bitsch F., Delhon I., and Fournier B.. 2004. Crystal structure of the human RORalpha Ligand binding domain in complex with cholesterol sulfate at 2.2 A. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 14033–14038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pikuleva I. A. 2008. Cholesterol-metabolizing cytochromes P450: implications for cholesterol lowering. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 4: 1403–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mast N., White M. A., Bjorkhem I., Johnson E. F., Stout C. D., and Pikuleva I. A.. 2008. Crystal structures of substrate-bound and substrate-free cytochrome P450 46A1, the principal cholesterol hydroxylase in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105: 9546–9551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goyal S., Xiao Y., Porter N. A., Xu L., and Guengerich F. P.. 2014. Oxidation of 7-dehydrocholesterol and desmosterol by human cytochrome P450 46A1. J. Lipid Res. 55: 1933–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Janin J., and Sternberg M. J.. 2013. Protein flexibility, not disorder, is intrinsic to molecular recognition. F1000 Biol. Rep. 5: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kyte J., and Doolittle R. F.. 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157: 105–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Howard R. J., Slesinger P. A., Davies D. L., Das J., Trudell J. R., and Harris R. A.. 2011. Alcohol-binding sites in distinct brain proteins: the quest for atomic level resolution. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 35: 1561–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dopico A. M., Bukiya A. N., and Martin G. E.. 2014. Ethanol modulation of mammalian BK channels in excitable tissues: molecular targets and their possible contribution to alcohol-induced altered behavior. Front. Physiol. 5: 466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dwyer D. S., and Bradley R. J.. 2000. Chemical properties of alcohols and their protein binding sites. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57: 265–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bukiya A. N., Kuntamallappanavar G., Edwards J., Singh A. K., Shivakumar B., and Dopico A. M.. 2014. An alcohol-sensing site in the calcium- and voltage-gated, large conductance potassium (BK) channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111: 9313–9318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang T. Y., Chang C. C., Ohgami N., and Yamauchi Y.. 2006. Cholesterol sensing, trafficking, and esterification. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22: 129–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bukiya A. N., Belani J. D., Rychnovsky S., and Dopico A. M.. 2011. Specificity of cholesterol and analogs to modulate BK channels points to direct sterol-channel protein interactions. J. Gen. Physiol. 137: 93–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Singh D. K., Shentu T. P., Enkvetchakul D., and Levitan I.. 2011. Cholesterol regulates prokaryotic Kir channel by direct binding to channel protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1808: 2527–2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Singh A. K., McMillan J., Bukiya A. N., Burton B., Parrill A. L., and Dopico A. M.. 2012. Multiple cholesterol recognition/interaction amino acid consensus (CRAC) motifs in cytosolic C tail of Slo1 subunit determine cholesterol sensitivity of Ca2+- and voltage-gated K+ (BK) channels. J. Biol. Chem. 287: 20509–20521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li H., and Papadopoulos V.. 1998. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor function in cholesterol transport. Identification of a putative cholesterol recognition/interaction amino acid sequence and consensus pattern. Endocrinology. 139: 4991–4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]