Abstract

Objective:

Brain tumors cause great mortality and morbidity worldwide, and success rates with surgical treatment remain very low. Several recent studies have focused on introduction of novel effective medical therapeutic approaches. Genistein is a member of the isoflavonoid family which has proved to exert anticancer effects. Here we assessed the effects of genistein on the expression of MMP-2 and VEGF in low and high grade gliomas in vitro.

Materials and Methods:

High and low grade glioma tumor tissue samples were obtained from a total of 16 patients, washed with PBS, cut into small pieces, digested with collagenase type I and cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS. When cells reached passage 3, they were exposed to genistein and MMP-2 and VEGF gene transcripts were determined by quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR).

Results:

Expression of MMP-2 demonstrated 580-fold reduction in expression in low grade glioma cells post treatment with genistein compared to untreated cells (P value= 0.05). In cells derived from high grade lesions, expression of MMP-2 was 2-fold lower than in controls (P value> 0.05). Genistein caused a 4.7-fold reduction in VEGF transcript in high grade glioma cells (P value> 0.05) but no effects were evident in low grade glioma cells.

Conclusion:

Based on the data of the present study, low grade glioma cells appear much more sensitive to genistein and this isoflavone might offer an appropriate therapeutic intervention in these patients. Further investigation of this possibility is clearly warranted.

Keywords: Glioma, genistein, matrix metalloproteinase 2, vascular endothelial growth factor

Introduction

Brain cancer is a heterogonous group of brain neoplasia originating in intracranial tissue and meninges and display multiple levels of malignancy (Abdullah et al., 2014). Glial cancers, also known as glioma, are brain neoplasm derived from mutated glial cells accounting for around 50% of CNS tumors (Le et al., 2003; Abdullah et al., 2014). High morbidity and mortality is reported in more malignant forms such as high-grade glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) that might be able to invade throughout the CNS (Le et al., 2003). Despite standard therapy of glioblastoma, debulking of the tumor, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the median survival is approximately 12–15 months for patients with glioblastomas and 2–5 years for patients with anaplastic gliomas (Stupp et al., 2005; Munson et al., 2013). Therefore, new treatment modalities are essentially needed in order to significantly improve the prognosis of patients with brain cancer.

Invasion is a process in which tumor cells migrate from the tumor mass and infiltrate into the adjacent normal brain tissue by degrading the extracellular matrix (ECM) using various matrix degrading enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (Brooks et al., 1996; Puli et al., 2006). MMPs have key roles in angiogenesis and tumor progression and a link between deregulated MMPs and invasiveness in human cancers has been documented (Le et al., 2003). High expression of MMP-2 or gelatinase-A is reported in different types of tumors such as glioma and invasiveness of glioma cell lines can be reduced by inhibiting metalloproteinases (Forsyth et al., 1999; Le et al., 2003)

Recently, there has been heightened interest into the alternative therapeutic approaches using anticancer agents. Previous reports have led to a great deal of attention into the anti-cancer effects of genistein as a soybean-derived isoflavone (Nakamura et al., 2009)through different mechanisms including inhibition of Topoisomerase II and protein tyrosine kinase activity, inhibition of angiogenesis, and prevention of cancer progression and invasion (Shao et al., 1998; Myoung et al., 2003). Another important characteristic of genistein. is its less toxicity and side effects even at high concentrations compared to the other anti-cancer agents (Myoung et al., 2003).

Genistein enhanced growth inhibition and apoptosis of nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines when combined with the EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (Gadgeel et al., 2009). In PC3 prostate cancer cells treated with genistein, the expression of angiogenesis and tumor invasion related genes such as neuropilin, MMP-9, VEGF and TGF-β2 showed the greatest down regulation (Li and Sarkar, 2002). Controversially, this isoflavone up regulates epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor signaling and contributes to tumor development in advanced prostate cancer (Nakamura et al., 2011). The motivation behind this study was to assess the effect of genistein on survival of brain tumor derived cells. This study further indicates the angiogenesis target of genistein focusing on the expression of MMP-2 and VEGF in low grade versus high grade gliomas.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and culture of mesenchymal stem cell like cells

Brain tumor tissues were transferred to Stem Cell Laboratory, Shiraz Institute for Cancer Research in sterile condition. As explained before (Razmkhah et al., 2013)tissues were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), chopped and digested by 0.2% collagenase type I at 37ºC for getting single cells. Afterward, the resulted soup was transferred on Ficoll-Paque (Biosera, UK) and subsequently the cell ring was cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Merelbeke, Belgium) and 1% penicillin streptomycin (Invitrogen, Merelbeke, Belgium). After 72 hours unattached cells were removed and cells were harvested in the third passage.

Flow cytometric characterization of the cells

Isolated cells were harvested using dissociation solution (Sigma, USA), washed twice with PBS and then stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated mouse anti-human CD45, CD34 and CD14 (BD Biosciences, USA) and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated mouse anti-human CD44 and CD166 (BD Biosciences, USA) and APC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD73. Isotype-matched irrelevant monoclonal antibodies (BD-Pharmingen, USA) were used as negative controls. After 30 minutes incubation at room temperature and washing with PBS, approximately 10,000 events were collected on a FACS Calibur machine (BD Biosciences, USA) using the Cell quest as data acquisition software and analyzed using FlowJo7.6 software for the graphical presentation of data.

MTT assay

In passage 3, cells were seated in 96 well plates and treated with variety concentrations of genestein (Sigma, UK) (0, 0.01, 0.004, 0.002 and 0.001M) and incubated for 24, 48 and 72 hours. After incubation times 5mg/ml MTT (Dimethylthiazolyldiphenyltetrazolium Bromide) was added to the cells and incubated for 4-5 hours at 37ºC in humidified CO2 incubator. Afterwards, MTT liquid was completely removed and kept up in the dark place and then DMSO (Merck, Germany) was added to each well, incubated for 24 hours and the absorbance of the plate was read at 495 nm.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Whole RNA was extracted from treated and untreated cells by using TRizol reagent (Invitrogen, Germany) and phenol chloroform (Merck, Germany) method. cDNA was synthesized from the extracted RNAs using the cDNA synthesis kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Fermentas, Lithuania).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

The amounts of MMP-2, VEGF and 18srRNA (housekeeping gene) were evaluated by an ABI thermal cycler (ABI, USA) using qRT-PCR. Each PCR reaction was carried out in a final volume of 20 μl containing 2μl cDNA, 10μl of 2X SYBR Green Master Mix (Fermentas, Canada), 0.3 μl of each 10 pmol forward and reverse primers and 7.4 μl DEPC treated water. Thermal cycling for all the genes was initiated with a denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 50 cycles with the subsequent program for each cycle: 95 °C for 20 s, 56°C for 20 s and 60 °C for 1 minute.

Statistical analysis

The relative amounts of MMP-2 transcripts were determined using 2−ΔΔCt formula and were compared between different groups using nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test by SPSS software version 15. Relative expression was plotted and evaluated by means of GraphPad Prism 5 software (Inc; San Diego CA, USA, 2003). P value<0.05 was regarded as significant in all statistical analyses.

Results

Morphological and flow cytometric characterization of cultured tumor cells

Brain tumor derived cells were emerged with plastic adherent properties in culture with mesenchymal like appearance (Figure 1) and good expansion ability up to 11 passages.

Figure 1.

Cells Appeared with Spindle Shape in Culture. A. Low Grade Glioma Derived Cells. B. High Grade Glioma Derived Cells

Besides, the isolated cells expressed mesenchymal specific surface markers such as CD44, CD73, CD166 while they had no expression of CD34, CD45, and CD14 markers. Figure 2 demonstrates typical staining profile of the cells.

Figure 2.

The Schematic Representation of One of Brain Tumor Derived Cells for the Expression of CD44, CD166, CD73, CD14, CD34 and CD45 by Flow Cytomety.

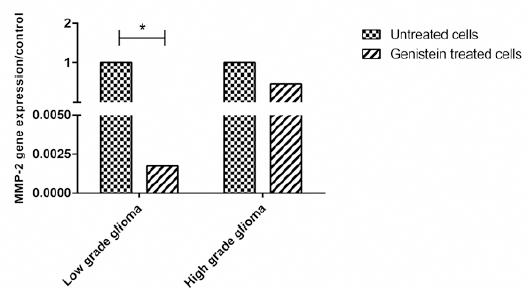

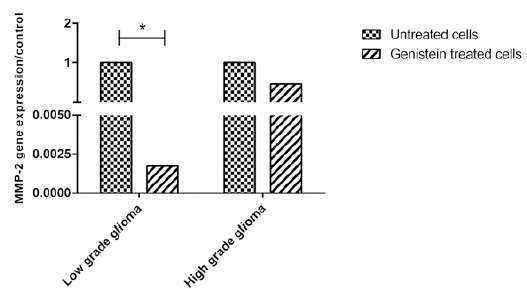

Figure 3.

Gene Expression of MMP-2 in Low and High Grade Glioma Cells before and after Treatment with Genistein. Data is Presented as the Median of 2-ΔΔCt

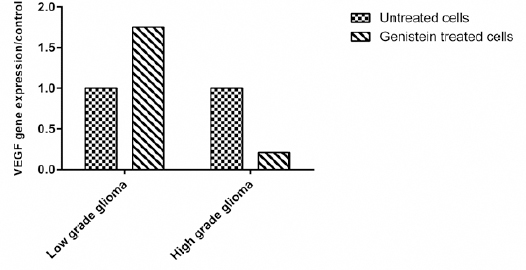

Figure 4.

VEGF mRNA Expression in Untreated and Genistein Treated Low and High Grade Glioma Cells. Data is Presented as the Median of 2-ΔΔCt

Survival of the cells before and after treating with genistein using MTT assay

To show the survival of the cells in vitro, MTT assay was performed on these cells before and after treating with genistein. As a result, high grade and low grade gliomas showed approximately 2-fold decrease in viability after treating with genistein (P value< 0.05).

Expression of MMP-2 gene transcript in Low versus high grade glioma derived cells post treatment with genistein

mRNA expression of MMP-2 in low grade glioma was approximately 12.6-fold higher than its expression in high grade glioma but this difference was not statistically significant (P value> 0.05).

After treatment with genistein, expression of MMP-2 reduced in both high and low grade derived cells. It showed 580-fold significant lower expression in low grade glioma post treatment with genistein compared to untreated cells (P value= 0.05). In genistein-treated high grade derived cells expression of MMP-2 was 2-fold lower than its expression in untreated cells (P value> 0.05).

Expression of VEGF gene transcript in low versus high grade glioma derived cells treated with genistein

VEGF mRNA showed 8.6-fold non-significant higher expression in high grade glioma compared to low grade patients.

Treatment the cells with genistein caused no reduction in VEGF in low grade glioma cells but led to a 4.7-fold non-significant reduction in VEGF transcript in high grade glioma cells (P value> 0.05).

Discussion

Brain tumor is still a fatal disease with significant impact on quality of life (Plaisier et al., 2016). Even after receiving numerous treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery, recurrence of this cancer is almost inevitable (Maule et al., 2016). Although great advances have been made in brain surgical treatment, it is still unable to totally cure malignant tumors because complete removal of tumor cells is somewhat impossible (Weinstein, 2002). In recent years, several genetic and molecular methods have been introduced to provide effective medical treatments in order to cure such malignant tumors. Recent molecular studies have been successful in finding the most important alterations in intra and extracellular molecules. Over expression or under expression of special genes may lead to deregulation of apoptosis, angiogenesis, and proliferation and increase in invasive features of tumoral cells. Angiogenic factors such as MMPs and VEGF seem to be the most important mediators enhancing extracellular matrix dissociation, angiogenesis and invasion of malignant cells (Weber et al., 2011; Gomes et al., 2013). Recent studies have succeeded to show that MMP-2 and MMP-9 play great roles in tumor cell invasion and adhesion which may be inhibited by tissue inhibitor of MMP (TIMP) (Bourboulia and Stetler-Stevenson, 2010). Genistein as a member of isoflavonoids has been reported with antineoplastic characteristic through inhibiting tyrosine kinase and MMP-13 activity in tumoral cells thus tapering malignant behavior of tumor cells (Spagnuolo et al., 2015). There is a wealth of evidence for the effect of genistein on inducing the apoptosis of pancreatic tumor cells and regulating molecules involved in cell cycle, invasion and metastasis (Han et al., 2012).

Here we isolated mesenchymal stem cell like cells from patients with high grade and low grade gliomas and, for the first time, compared the effect of genistein on the survival of these cells, separately. Expression of two important angiogenic mediators, MMP-2 and VEGF, were then assessed in these cells.

Based on the results both low grade and high grade glioma cells were found as spindle shaped mesenchymal stem cell like cells while exhibiting mesenchymal specific markers; both cells were negative for CD14, CD34 and CD45 and more than 90% of the brain derived cells were positive for the expression of CD44, CD73, CD166. These results are in line with our previous report showing the mesenchymal specific characteristics of brain derived cells with great attitude for growing in high passages (Razmkhah et al., 2013). It has been demonstrated that the activity and phenotype characteristics of human GBM cell line, U87MG, is resemblance to mesenchymal stem cells since it expresses MSC specific markers, has differentiation capability and shows immunomodulatory features (Nakahata et al., 2010). Similarly, in a study by Brewer (2007), cells from glioblastoma were cultured and appeared with mesenchymal morphology (Brewer and LeRoux, 2007).

Furthermore, we detected MMP-2 and VEGF mRNA in brain derived cells. mRNA expression of MMP-2 was higher in low vs. high grade glioma cells. In contrast, VEGF mRNA showed higher expression in high grade glioma cells. The differential expression of these two important angiogenic factors may be crucial for deciding on unique treatment challenges for low grade and high grade glioma tumors especially that other key mediators such as RANTES, CCR5 and MCP-1 showed no significant difference between low and high grade glioma cells (Razmkhah et al., 2013).

Additionally, genistein decreased the viability of our high grade and low grade glioma cells. The molecular targets of genistein was reported in various types of tumors including breast, prostate, colon, liver, ovarian, bladder, gastric, brain cancers, neuroblastoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Russo et al., 2016). Khaw (2012) determined the increased expression of p21 and decreased expression of cyclin B1and CDK1 resulting in cell cycle arrest in radio sensitive brain tumor cell lines after treating with genistein.

Exposure of the expanded cells to genistein caused reduction in MMP-2 mRNA in both low and high grade derived cells which was significant in the former. Also a non-significant decrease was found in VEGF but only in high grade glioma cells. Consequently, angiogenic factors seem to be the targets of genistein especially in low grade glioma.

Yu and coworkers (2012) imputed an anti-angiogenic effect to genistein as treatment of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)caused endothelial apoptosis by inhibiting MMPs and down regulating VEGF mediated activation of JNK and p38. In another study angiogenesis inhibitors such as endostatin and angiostatin has been introduced as molecular targets for genistein (Su et al., 2005). Remarkably, soy food consumption has been proved to be notably associated with decreased risk of death and recurrence in women with breast cancer (Shu et al., 2009).

Collectively, our findings suggested that genistein is not different in its impact on the survival of low compared to high grade glioma cells. This isoflavone is capable to target angiogenic pathways more significantly in low grade glioma patients, which thereby may represent a mechanism that further clarify the anti-angiogenesis and anti-cancer effect of genistein in this group of patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank patients and all participants for their kind contribution in this project. This work was supported by grants from Shiraz University of Medical Sciences [Grant No. 92-01-01-6075] and Shiraz Institute for Cancer Research [ICR-100-504]. This research was done as a requirement for the Medical thesis defended by Dr. Yasaman Yazdani.

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there is no conflict of interest

References

- Abdullah JM, Mustafa Z, Ideris A. Newcastle disease virus interaction in targeted therapy against proliferation and invasion pathways of glioblastoma multiforme. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:386470. doi: 10.1155/2014/386470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourboulia D, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs): Positive and negative regulators in tumor cell adhesion. Sem Cancer Biol. 2010;20:161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, LeRoux PD. Human primary brain tumor cell growth inhibition in serum-free medium optimized for neuron survival. Brain Res. 2007;1157:156–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks PC, Strömblad S, Sanders LC, et al. Localization of matrix metalloproteinase MMP-2 to the surface of invasive cells by interaction with integrin αvβ3. Cell. 1996;85:683–93. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth P, Wong H, Laing T, et al. Gelatinase-A (MMP-2), gelatinase-B (MMP-9) and membrane type matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MT1-MMP) are involved in different aspects of the pathophysiology of malignant gliomas. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1828. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6990291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadgeel SM, Ali S, Philip PA, Wozniak A, Sarkar FH. Genistein enhances the effect of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors and inhibits nuclear factor kappa B in nonsmall cell lung cancer cell lines. Cancer. 2009;115:2165–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes FG, Nedel F, Alves AM, Nör JE, Tarquinio SBC. Tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis: tumor/endothelial crosstalk and cellular/microenvironmental signaling mechanisms. Life Sci. 2013;92:101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L, Zhang H, Zhou W, Chen G, Guo K. The effects of genistein on transforming growth factor-β1-induced invasion and metastasis in human pancreatic cancer cell line Panc-1 in vitro. Chin Med J. 2012;125:2032–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaw AK, Yong JWY, Kalthur G, Hande MP. Genistein induces growth arrest and suppresses telomerase activity in brain tumor cells. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:961–74. doi: 10.1002/gcc.21979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le DM, Besson A, Fogg DK, et al. Exploitation of astrocytes by glioma cells to facilitate invasiveness: a mechanism involving matrix metalloproteinase-2 and the urokinase-type plasminogen activator–plasmin cascade. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4034–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04034.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Sarkar FH. Down-regulation of invasion and angiogenesis-related genes identified by cDNA microarray analysis of PC3 prostate cancer cells treated with genistein. Cancer Lett. 2002;186:157–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maule F, Bresolin S, Rampazzo E, et al. Annexin 2A sustains glioblastoma cell dissemination and proliferation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:54632. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson J, Bonner M, Fried L, et al. Identifying new small molecule anti-invasive compounds for glioma treatment. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:2200–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.25334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myoung H, Hong SP, Yun PY, Lee JH, Kim MJ. Anti-cancer effect of genistein in oral squamous cell carcinoma with respect to angiogenesis and in vitro invasion. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:215–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01422.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahata AM, Suzuki DE, Rodini CO, et al. Human glioblastoma cells display mesenchymal stem cell features and form intracranial tumors in immunocompetent rats. World J Stem Cells. 2010;5:103–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H, Wang Y, Kurita T, et al. Genistein increases epidermal growth factor receptor signaling and promotes tumor progression in advanced human prostate cancer. PloS One. 2011;6:e20034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Yogosawa S, Izutani Y, et al. A combination of indole-3-carbinol and genistein synergistically induces apoptosis in human colon cancer HT-29 cells by inhibiting Akt phosphorylation and progression of autophagy. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaisier CL, O’Brien S, Bernard B, et al. Causal mechanistic regulatory network for glioblastoma deciphered using systems genetics network analysis. Cell Systems. 2016;3:172–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puli S, Lai JC, Bhushan A. Inhibition of matrix degrading enzymes and invasion in human glioblastoma (U87MG) cells by isoflavones. J Neurooncol. 2006;79:135–42. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razmkhah M, Arabpour F, Taghipour M, et al. Expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors in brain tumor tissue derived cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;15:7201–5. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.17.7201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo M, Russo GL, Daglia M, et al. Understanding genistein in cancer: The “good” and the “bad” effects: A review. Food Chem. 2016;196:589–600. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z-M, Wu J, Shen Z-Z, Barsky SH. Genistein exerts multiple suppressive effects on human breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4851–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu XO, Zheng Y, Cai H, et al. Soy food intake and breast cancer survival. JAMA. 2009;302:2437–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spagnuolo C, Russo GL, Orhan IE, et al. Genistein and cancer: current status, challenges, and future directions. Advances in Nutrition. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:408–19. doi: 10.3945/an.114.008052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupp R, Mason WP, Van Den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S-J, Yeh T-M, Chuang W-J, et al. The novel targets for anti-angiogenesis of genistein on human cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:307–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber GF, Bjerke MA, DeSimone DW. Integrins and cadherins join forces to form adhesive networks. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1183–93. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein IB. Addiction to oncogenes-the Achilles heal of cancer. Science. 2002;297:63–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1073096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Zhu J, Mi M, et al. Anti-angiogenic genistein inhibits VEGF-induced endothelial cell activation by decreasing PTK activity and MAPK activation. Med Oncol. 2012;29:349–57. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9770-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]