Abstract

Introduction:

Gutkha contains harmful and carcinogenic chemicals and oral cancer caused by tobacco usage has been reported as a major preventable cause of death worldwide by the World Health Organization. The Telangana state government implemented a ban on gutkha usage starting in 2013 but how effective this ban has been remains unclear.

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to determine the actual impact of the gutkha ban on users and vendors.

Methodology:

A cross-sectional study was conducted among gutkha users and tobacco vendors in Ranga Reddy district, Telangana. Based on a pilot study the sample size was determined as 368 and 384 for users and vendors respectively. Two separate questionnaires were administered to these groups. The parameters studied mainly included knowledge regarding the ban, and its impact.

Results:

About 49.1% of the users were aware of the ban on gutkha. Newspapers were the main source of information regarding the ban as reported by 45.3% of users. After the ban, 29.8% of gutkha users switched to other tobacco products. Awareness of health hazards and non-availability of gutkha was the most important reason stated for quitting or reducing consumption.

Conclusion:

The perspective of ban when visualized from the users point of view depicted a negative impact while the vendors portrayed a positive impact. Considering the addictive potential of the ingredients of gutkha, recording the effects of the ban on regular consumers and determining whether they can still obtain the products by illicit trade, would be noteworthy for implementation of strict rules.

Keywords: Tobacco ban, gutkha, tobacco use

Introduction

Human beings have been using tobacco since 600 A.D. Harmful effects of tobacco have been recognized over the last 1,000 years (Chadda et al., 2002). Tobacco is used in both smoking and smokeless forms, e.g. bidi, gutkha, khaini, paan masala, hookah, cigarettes, cigars, chillum, chutta, gul, mawa, misri, etc all over the world. In order to facilitate the implementation of the tobacco control laws, which bring about greater awareness regarding harmful effects of tobacco and fulfill obligation(s) under the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC), the Government of India launched the National Tobacco Control Programme (NTCP) in the country (Sreeramreddy et al., 2008).

The world health organization reports it to be the preventable cause of death worldwide, and estimates that it currently causes 6 million deaths per year (WHO, 2015). According to global adult tobacco survey (GATS), the consumer base of tobacco in India stands at 34.6% of all adults while 75% of Indian tobacco consumers use non-smoking tobacco products such as gutkha (WHO, 2010). Gutkha is a powdery, granular light brownish to white substance which is a dry mixture of crushed areca nut, tobacco, catechu, nut products lime (calcium hydroxide), aromas and flavourings along with other added additives. They are blended according to a composition essential to formulate the mixture and is an industrially manufactured product. Gutkha is consumed by placing a pinch of it between gum and cheek and gently sucked on chewing, which turns deep red in color as it dissolves. Due to its flavored taste, easy availability and being socially acceptable, it is popular among poor children who exhibit precancerous lesions at an early age (Edelweiss, 2012).

The usage of gutkha causes oral submucous fibrosis, leukoplakia, erythroplakia and other debilitating conditions named as “gutkha syndrome” by Chaturvedi (Chaturvedi, 2009; Agarwal et al., 2015; Rekha et al., 2012). Many states of India have banned the sale, manufacture, distribution and storage of gutkha and all its variants. The federal Food safety and regulation (Prohibition) Act 2011 allows harmful products such as gutkha to be banned for a year. The state government has implemented a ban on gutkha usage from 2013. The ban is enforced by the state public health ministry, the state Food and Drug Administration, and the local police. The law has provisions of imposing fines up to rupees 25,000 on selling of products that are injurious to health.

Even after the ban was implemented dealers managed to sell gutkha through illegal trade. The traces of gutkha being used have been evident in the form of empty gutkha packets thrown on the streets and lanes. So how effective is this ban?

Considering the addictive potential of the ingredients of gutkha, recording the effect of this ban on regular users, i.e., are they still getting the products by illicit trade or hove they shifted to other tobacco products, would be noteworthy. If regular users discontinue consumption of gutkha because of ban, it would be an efficient indication supporting the legal ban for better maintenance of public health. Thus, the response of gutkha users to the ban needs to be studied.

Understanding the awareness and the reactions of the tobacco vendors about the ban is also important for the further development of public health strategy to sustain the gutkha ban. So the aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of gutkha ban among gutkha users and vendors.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among gutkha users and vendors in Ranga Reddy district of Telangana for a period of one month. A pilot study was conducted among 30 users and vendors from which the sample size was estimated. The sample size determined was 384 for vendors and 368 for users. Ranga Reddy district has three revenue divisions which consists of 37 mandals. A mandal is a city or town that serves a administrative centre, with possible towns, and a number of villages under it. Three mandals from each division were selected randomly and in turn three villages from each mandal was selected. All the vendors who were selling gutkha among the selected villages, present on the day of the study and willing to participate were included using cluster sampling method, whereas users of gutkha were identified by convenience sampling method. Informed consent was taken verbally prior to the study from every individual. Two separate questionnaires prepared in the vernacular language were used for vendors and users which were developed based on previous literature. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was checked after the pilot study by dichotomizing the responses as yes or no. Reliability of the questionnaires was checked Cronbach’s alpha obtained was equal to 0.9. The questionnaire consisted of closed ended questions and obtained information regarding the socio-demographic details, and the effects of the ban on change in tobacco habit and various factors responsible for the same. The questionnaires were collected back on the same day, after giving them sufficient time to fill. Individuals who were illiterate were interviewed by the researcher.

Results

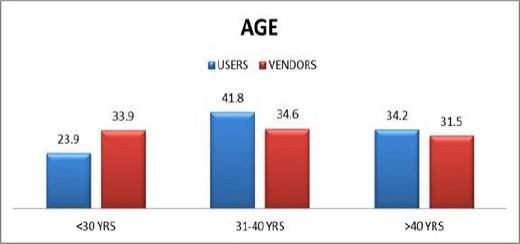

A cross-sectional study was conducted on gutkha users and vendors to know the impact of ban. The demographic details of the gutkha users and vendors are shown in figure 1 and 2. Table 1 shows only half (49.2%) of the users were aware of the ban and major source of information regarding the ban was newspapers (45.8%). There was a significant difference seen among the age, occupation and education groups with respect to awareness regarding the ban. An important highlight of this study was that 62.2% of the users replied that gutkha was still available in the market and 98.6% have reported that it was available in the form of two separate sachets. There were about 29.9% of the users who shifted to other forms of tobacco use and among them mawa 51.8% was most commonly used. Among the participants 24.2% felt that creating awareness on health hazards of gutkha can reduce the usage of gutkha by the consumers.

Figure 1.

Age of Gutkha Users and Vendors

Figure 2.

Education Status of Gutkha Users and Vendors

Table 1.

Gutkha Users

| N | % | Association with age | Association with occupation | Association with education | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chewing gutkha can cause health hazards like cancer | Strongly agree | 125 | 34.0% | |||

| Agree | 177 | 48.1% | ||||

| Disagree | 52 | 14.1% | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 14 | 3.8% | ||||

| Awareness on ban | Aware | 181 | 49.2% | 0.004* | <0.001* | 0.016* |

| Unaware | 187 | 50.8% | ||||

| Source of information about the ban | Tobacco vendors | 25 | 13.8% | 0.008* | <0.001* | 0.056* |

| Newspapers | 83 | 45.8% | ||||

| Friends | 23 | 12.8% | ||||

| Electronic media | 43 | 23.8% | ||||

| Don’t know | 7 | 3.8% | ||||

| Availability of gutkha at shops | Available | 229 | 62.2% | |||

| Not available | 139 | 37.8% | ||||

| Switched to other tobacco products | Yes | 110 | 29.9% | 0.002* | <0.001* | 0.002* |

| No | 258 | 70.1% | ||||

| Other tobacco products | Pan | 17 | 15.4% | 0.022* | <0.001* | 0.067 |

| Mawa | 57 | 51.8% | ||||

| Khaini | 22 | 20.0% | ||||

| Others | 14 | 12.8% | ||||

| Availability in separate sachets | Available | 363 | 98.6% | |||

| Not available | 5 | 1.4% | ||||

| Is it feel the same | Yes | 28 | 7.6% | |||

| No | 340 | 92.4% | ||||

| Tried to quit gutkha | Yes | 300 | 81.5% | 0.01* | 0.01* | 0.018* |

| No | 68 | 18.5% | ||||

| Reasons which stopped users from quitting | Addiction | 99 | 33.0% | 0.005* | <0.001* | 0.018* |

| Friends | 79 | 26.4% | ||||

| Pleasure | 81 | 27.0% | ||||

| Others | 41 | 13.6% | ||||

| reasons which can make users quit gutkha | Non availability | 84 | 22.8% | 0.077 | 0.021* | 0.48 |

| Increased cost | 70 | 19.0% | ||||

| increased awareness about ban | 69 | 18.8% | ||||

| Awareness of health hazards | 89 | 24.2% | ||||

| Must know by themselves | 56 | 15.2% |

p-value <0.005

Table 2 shows that majority of the gutkha vendors 89.6% knew about the ban imposed on gutkha, with newspapers 52.8% as the main source of information about the ban. There was significant difference between age and awareness regarding ban whereas no difference was seen between education status of gutkha vendors and awareness regarding the ban. 24% of the vendors felt that the ban was not effective in reducing gutkha consumption.

Table 2.

Gutkha Vendors

| n | % | association with age | association with education | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chewing gutkha can cause health hazards like cancer | agree | 183 | 47.7% | ||

| strongly agree | 177 | 46.1% | |||

| disagree | 21 | 5.5% | |||

| strongly disagree | 3 | 0.8% | |||

| Awareness on ban | aware | 344 | 89.6% | 0.008* | 0.175 |

| unaware | 40 | 10.4% | |||

| Source of information on ban | customers | 14 | 4.0% | ||

| newspapers | 175 | 52.8% | |||

| other vendors | 67 | 19.6% | |||

| electronic media | 77 | 22.4% | |||

| authority | 11 | 3.2% | |||

| Loss of business | yes | 307 | 79.9% | <0.001* | 0.904 |

| no | 77 | 20.1% | |||

| Are their less customers after the ban | yes | 260 | 67.7% | ||

| no | 124 | 32.3% | |||

| Did customers switch to other tobacco products | yes | 352 | 91.7% | ||

| no | 32 | 8.3% | |||

| Are people asking for gutkha available in sachets | yes | 359 | 93.5% | ||

| no | 25 | 6.5% | |||

| Aware of punishment | yes | 333 | 86.7% | 0.012* | 0.003* |

| no | 51 | 13.3% | |||

| Is ban effective in reducing gutkha consumption | agree | 112 | 29.2% | 0.001* | <0.001* |

| strongly agree | 180 | 46.9% | |||

| disagree | 66 | 17.2% | |||

| strongly disagree | 26 | 6.8% |

p-value <0.005

Discussion

The present study was conducted on the gutkha users and vendors from the selected villages of Ranga Reddy district Telangana. As the concept of gutkha ban is new, there are very few studies assessing its effect. Hence, the findings of this study are discussed in comparison to other studies assessing the effects of the ban on various types of tobacco products.

Nearly 50% of the users were aware of the ban on gutkha in our study which was in contrast with the study done by Mishra et al., (2014) where almost every user was aware of the ban. Newspapers followed by electronic media were the most common sources of information regarding the ban as quoted by the respondents. Newspapers play a major role in delivering the information to most of the population as it is inexpensive and easily available informative source. As the literacy rate in the present study was high, newspaper imparted its major role in spreading the information about ban on gutkha. Giving wide publicity to the gutkha ban through newspapers and television advertisements and putting visible banners at prominent places detailing the ban might have served the purpose. This is evident by a study done by Wakefield et al., (2011). Few users also came to know about the ban only after visiting the vendors, which is indicative of some fear of law enforcing authorities in the mind of tobacco vendors.

A major cause of concern is the availability of gutkha even after the legal ban, although at an increased cost in the black market, as reported by many users. Availability of tobacco products in market even after the ban has been reported by other researchers also. Ban on gutkha however showed an impact on reduction in gutkha consumption, as switching to other tobacco products due to the lack of availability of gutkha was seen. But switching users to other smokeless forms of tobacco products cannot be considered as an achievement of the law. Users have brand preferences, but they do switch type depending on cost, availability, and level of addiction. Various types of tobacco products other than gutkha preferred in the study were Mawa, Khaini and Pan which was found to be similar with the study conducted by Nair (2012).

New gutkha replacement products which consist of scented supari mix with a flavor similar to gutkha along with packets of loose tobacco are available in the market and almost all the users knew about it but they felt that the mixture did not give the same taste as that of original gutkha. If the same product changes the name, shape keeping the same composition and enters the market is that not considered as a mockery of the law?

The usage of gutkha causes oral sub mucous fibrosis, leukoplakia, erythroplakia and other debilitating conditions which most of the users are unaware. Many users have reported that awareness on health hazards along with non-availability can make the ban more affluent in reducing the gutkha consumption. The ban did not include a prohibition against using gutkha. So prohibition against usage completely and efficiently though available in market can also decrease its consumption. Increase in cost has also led to decrease in use, which was also supported in the studies conducted by Townsend (1996) and Gallus et al., (2006). This nature of very useful, expected implication of the tobacco ban is reported by various authors globally as well (Martin et al., 2012; Nair et al., 2012; Buonanno et al., 2013). The decrease in the use of tobacco products after the ban along with spreading the information is also evident from the literature (Lunze et al., 2013).

The ban has set in motion a number of processes that have shifted the patterns of stocking, selling, and using tobacco products. Vendors cannot obtain new supplies of gutkha, and, for the most part, do not sell it; thus, the ban has reduced supply, demand, and actual consumption.

Almost all the vendors knew about the ban and the punishment for violation of the law. Ambiguity about who is conducting surveillance and where and when it will be targeted coupled with a small number of examples of fines, both large and small, and the stigma associated with fines and imprisonment is reducing vendors in selling the product. However, the decrease of sales as reported by vendors is encouraging which was found in a similar study by Mishra et al (Bhaumik et al., 2013; Mishra et al., 2014).

Although gutkha is much less available, it can be purchased at higher cost and is still being used, as evidenced by empty gutkha packets thrown on the streets and lanes. New products resembling gutkha in packaging and taste/smell has become available and are being promoted. Most of the vendors think that the ban which is imposed is not effective in reducing gutkha consumption and strict measures in implementing this law must be taken to achieve its goal.

The law must include a prohibition against consuming gutkha along with manufacture and storage. Nationwide health awareness regarding hazards on consuming gutkha by the health providers and food agencies, need to be conducted.

The perspective of ban when visualized from the users point of view depicted a negative impact of ban while the vendors portrayed a positive impact of the ban. Whether the ban has a long term effect on cancer prevention and reduction of risk which is the main reason for the ban remains to be seen.

References

- Agarwal A, Tijare M, Saxena A, Rubens M, Ahuja R. Exploratory study to evaluate changes in serum lipid levels as early diagnostic and/or prognostic Indicators for oral submucous fibrosis and cancer among gutkha consumers in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:6439–44. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.15.6439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaumik S. Ban on smoking in workplaces in India has led to more smoke free homes. BMJ. 2013;346:f2186. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonanno P, Ranzani M. Thank you for not smoking: Evidence from the Italian smoking ban. Health Policy. 2013;109:192–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi P. Gutka or areca nut Chewer’s syndrome. Ind J Cancer. 2009;46:170–2. doi: 10.4103/0019-509x.49158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadda RK, Sengupta SN. Tobacco use by Indian adolescents. Tob Induc Dis. 2002;1:111–9. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-1-2-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelweiss Gutkha ban. Edelweiss securities limited. 2012. Available at http://www.edelresearch.com/rpt/showpdf.aspx?id=21445&reportname=/Consumer_Goods_-_sector_update-Sep-12EDEL.pdf&lgt=656vfdg&type=ynaj9XvqmJoptbYzJzovtA .

- Gallus S, Schiaffino A, La Vecchia C, Townsend J, Fernandez E. Price and cigarette consumption in Europe. Tob Control. 2006;15:114–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán A, Walsh MC, Smith SS, Malecki KC, Nieto FJ. Evaluating effects of statewide smoking regulations on smoking behaviors among participants in the survey of the health of Wisconsin. WMJ. 2012;111:166–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunze K, Migliorini L. Tobacco control in the Russian federation –A policy analysis. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SA, Celli BR, DiFranza JR, et al. Health effects of the federal bureau of prisons tobacco ban. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra GA, Gunjal SS, Pimple SA, et al. Impact of gutkha and pan masala ban in the state of Maharashtra on users and vendors. Ind J Cancer. 2014;51:129–32. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.138182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair S, Schensul JJ, Bilgi S, et al. Local responses to the Maharashtra gutka and pan masala ban: A report from Mumbai. Ind J Cancer. 2012;49:443–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.107754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekha B, Anjum Effectiveness of pictorial warnings on tobacco packs : hospital based study findings from Vikarabad. J Int Soc Prevent Communit Dent. 2012;2:13–9. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.103449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreeramreddy CT, Kishore PV, Paudel J, Menezes RG. Prevalence and correlates of tobacco use amongst junior collegiates in twin cities of western Nepal: A cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey. BMC. 2008;14:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend J. Price and consumption of tobacco. Br Med Bull. 1996;52:132–42. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield MA, Spittal MJ, Yong HH, Durkin SJ, Borland R. Effects of mass media campaign exposure intensity and durability on quit attempts in a population-based cohort study. Health Educ Res. 2011;26:988–97. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Prevalence of tobacco use [Online] 2015 [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) [Online] Ministry of Health & Family Welfare; 2010. [Google Scholar]