Abstract

Objective:

Regulation of sale of tobacco has given sufficient attention in India and little information exists about the impact of bans near schools. Our study aim was to check the levels of tobacco promotion, advertising and sales in school neighborhoods’ of Central Delhi.

Methods:

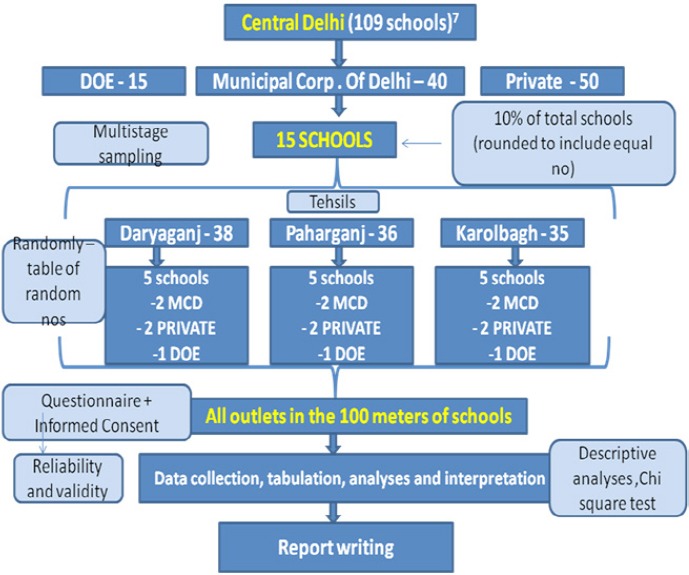

Using multistage random sampling 15 schools were selected in Central Delhi. Areas 100 meters around each were mapped using a map tool and screened using a self designed questionnaire consisting of 26 questions, both closed and open ended, to determine the details of outlets, sales of tobacco and tobacco products, advertising, promotions, school roles, and children seeking tobacco. The data were subjected to statistical analysis.

Results:

The response rate was 65%. Outlet licenses were present in only 6 (3.47%). The point sale of tobacco was most frequently in tea stalls and a total of 173 (41.2%) outlets had some form of tobacco sale. The brands of smokeless tobacco sold more were shikar (50%) and classic citrus (30%). Advertisement or promotion of sales was mainly in the form of signs and displays (53%). Major schools did not have any no tobacco boards displayed.

Conclusion:

Sale of tobacco continues in central Delhi with a lack of compliance with the rules of COPTA. The implications of this non compliance in the Capital region is of major significance for the rest of the country.

Keywords: COPTA, tobacco, tobacco sale and advertisement, tobacco outlets, tobacco free schools

Introduction

Tobacco use (smoked and smokeless) in youth in both low and high income countries is a public health concern. India is the world’s second largest producer of tobacco and also the second largest consumer of unmanufactured tobacco (Schensul et al., 2013). Studies show that environmental, social and psychological factors create a major impact on adolescent tobacco use (Conrad et al., 1992). The availability, accessibility and affordability of tobacco products are key contributors to the level of adolescent tobacco use (Bhojani et al., 2009).

Tobacco companies spend more money on the retail outlet than any other advertising venue. Retail outlet or point-of-purchase (POP) spending includes slotting fees, promotional allowances, and other POP marketing programmes (Ellen et al., 2001). Recent efforts to restrict tobacco product advertising have focused largely on more traditional venues, such as magazines and billboards, while the retail outlet virtually has been ignored. Anon (1999) and Point of Purchase Advertising Institute (1992) emphasized that the ads and displays have been found to boost average tobacco sales by 12% to 28%. Warner (1986) report clarified that the retail outlet advertising, like other forms of advertising, may also entice children and young adults to begin smoking. Cigarette advertising has been related to increased uptake and maintenance of smoking among adolescents (Aitken and Eadie, 1990; Pierce et al., 1991; Gilpin and Pierce, 1997).

In India the National tobacco control cell, Resource center for tobacco free India and the campaign for tobacco free kids have mentioned the restriction of the sale of tobacco products within 100 meters of schools under the Control of Tobacco Products Act (COTPA). Unfortunately, this strategy has not been widely implemented in the India. A US study correlated data from the Monitoring the Future school surveys with the prevalence of tobacco advertising in convenience stores near the surveyed schools (Meich et al., 2014). A national survey of students (aged 14–15) in New Zealand by Lisa et al., (2010) observed a graded, cross-sectional relationship between the frequency of visiting stores that sell cigarettes and the odds of experimenting with smoking. Reducing teenage smoking is one of the targets identified in the Health of the Nation, but progress towards the target so far has been marginal. Complete ban in sale would be an effective way to reduce the prevalence of smoking in India.

Tobacco use among adolescents has declined since 2000, but 21% of eighth-graders and 45% of high school seniors still report experimenting with smoking.15 Because this behavior increases the risk for adult smoking (Redmond, 1999; Jackson and Dickinson, 2009), it is important for professionals to be aware of environmental factors that promote smoking experimentation and initiation in childhood and adolescence. According to Global youth tobacco survey (2003-2009) among 13- 15 year olds in India, 14.6% of students currently use any form of tobacco; 4.4% currently smoke cigarettes; 12.5% currently use some other form of tobacco. 8.1% students were offered free cigarettes by a tobacco company representative.

Accumulating evidence suggests that widespread advertising for cigarettes at the point of sale encourages adolescents to smoke (Molly et al., 2008; Paul et al., 2008; Bhojani etal.,2009; Lisa et al., 2010; April et al., 2010). Despite the vast amount of spending at retail outlets and its strategic importance to the tobacco companies, few studies (Sushma, 2005; Deepa et al., 2012) have examined tobacco advertising in retail outlets in India and none in Delhi. The impact of tobacco advertising and availability near schools on adolescent tobacco use in India has yet to be explored and especially in Delhi which is the capital of Nation, where in the rules and regulations should have strict emphasis and act as role model to the whole country.

Hence, a study was done with the aim to check the density of tobacco promotions, advertising and sales in school neighborhoods’ of Central Delhi. The objectives were to identify tobacco selling outlets within 100 meters of school premises and tobacco products (smoked and smokeless) sold in the outlets, type of tobacco selling outlets, to count and describe the tobacco product ads within 100 meters of school premises and in the outlets, no. of children visiting these tobacco selling outlets and type of schools with no tobacco signs.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross sectional descriptive survey done to assess the density of tobacco promotions, advertising and sales in school neighbourhoods of Central Delhi. Ethical clearance was obtained from ethical committee of Maulana Azad Institute of Dental Sciences, New Delhi, India. Informed consent was obtained from the subjects prior to the study. The outlets in the 100 meters of these schools who gave informed consent were included for the study procedure and for those who did not give consent only the details of outlet and sale were recorded by observation. The outlets with the potential and scope for tobacco sale were included in the study.

Sampling and Sample size estimation

A multistage random sampling was done. Central Delhi has 3 tehsils – Daryaganj, Pahar Ganj and Karol Bagh (Government of NCT of Delhi). There are a total of 109 schools in Central Delhi out of which 15 are Director of education (DoE) run and 40 by Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) and 54 are private schools. 15% of the total schools were included for the study which accounted to 13.7 schools which was rounded off to 15 schools. There are 35 schools in Karolbagh, 36 in Paharganj and 38 in Daryaganj. 5 total schools were selected randomly (Random of table nos.) from each tehsil – 2 Private and 2 MCD and 1 DoE school.

Study Setting

Central Delhi is an administrative district of the National Capital Territory of Delhi in India. Central Delhi has a population of 644,005 (2001 census), and an area of 25 square kilometres (9.7 sq mi), with a population density of 25,759 persons per km2. Central Delhi houses the main government offices, central business district and highrises.

Study Instrument

The Feighery et al., (2001) 4 questionnaire for types and definition of advertising material was used but modified to suit Indian scenario according to COPTA act 2013 (http://www.searo.who.int/india/tobacco/guidelines_law_enforcers_implementation_tobacco_control_law.pdf?ua=1) (Table 1). Rest of the questions were self designed. A total of 24 questions were present in which 9 were closed ended questions and rest open ended and filled by the investigator which assessed the tobacco-related activities in each outlet.

Table 1.

Types and Definition of Advertising Materials Collected at Stores

| Criteria | Measure | Definition | Modified for our study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of material | Signs | No.of signs that are posters, banners or lighted signs made by a cigarette manufacturer that are not part of other existing items such as displays or overhead bins. Categorized by size including < or≥14 square feet to determine compliance with master settlement agreement provisions to limit size to 14 square feet | No.of signs that are posters, banners or lighted signs made by a cigarette manufacturer that are not part of other existing items such as displays or overhead bins. Categorized by size not more than ninety centimetre by fourth-five centimeters centimetre and number of such boards shall not exceed two. Each such board shall contain in the Indian language as applicable, one of the following warning occupying twenty-five percent, of top area of the board, namely: - |

| (i) Tobacco Causes Cancer/r | |||

| (ii) Tobacco Kills | |||

| The health warning referred to must be prominent, legible and in black colour with a white background. | |||

| Prohibition of sale to minors. (1) a board of minimum size of sixty centimetre by thirty centimetre at conspicuous place(s) containing the warning “Sales of tobacco products to a person under the age of eighteen years is a punishable offence”, in Indian language(s) applicable. | |||

| Displays | No.of diplays with brand specific advertising including free standing racks provided by the manufacturer for display of cigarette products and plexi glass enclosed packs of cigarettes that are visible but inaccessible to consumers and clerks. | The brand of tobacco sachets and tobacco packs displayed on table and outside the outlets. The packs hanging outside or inside the outlet. | |

| Functional items | No.of brand specific items that have utility (for example branded shopping baskets, clocks and overhead bins etc). | No.of brand specific items that have utility (for example branded shopping baskets, clocks and overhead bins etc). | |

| Location | Exterior | No.of materials located outside the store including windows, doors, the building and side walk, or in the parking lot. Signs posted inside the store but facing outside were counted as exterior. | No.of materials located outside the store including windows, doors, the building and side walk, or in the parking lot. Signs posted inside the store but facing outside were counted as exterior. |

| Interior | No.of materials located inside the store including those attached to window or door excluding those facing outside. Recorded as near if on, behind or within 4 feet of the counter/ check out area, or far if more than 4 feet away from counter or check out area. | No.of materials located inside the store including those attached to window or door excluding those facing outside. | |

| Placement | Below 3 feet | Presence or absence of advertising materials at or below 3 feet from the floor. | Presence or absence of advertising materials at or below 3 feet from the floor. |

| Next to candy | Presence or absence of displays within 6 inches of candy (sweets) | Presence or absence of displays within 6 inches of candy (sweets) | |

| Above 3 feet | Presence or absence of advertising materials at or below 3 feet from the floor |

A pilot study was conducted on 10 outlets were tobacco was sold to assess the reliability and validity of questionnaire. The questionnaire was modified to include 2 more questions related to child visiting the outlet for tobacco and frequency of visit. The pilot results are merged with main study results. The reliability of questionnaire was assessed using the Cronbach Alpha coefficient which was found to be >0.581.

The validity of questionnaire was assessed by asking the sales person whether the questions were clear, understandable, and in a logical order (face validity). Moreover, the same sales person and 5 oral health professionals who had long experience in working with tobacco cessation activities were asked to criticize the content of the questionnaire (content validity). More specifically, they were asked to express their views on whether they consider the questions to be representative of the aim and topic of study or if some additional statements need to be added. The statistical analysis was not used to evaluate the construct validity of the questionnaire as it did not have many subscales for assessment. The criterion validity of the questionnaire was not checked, as a gold standard tool for assessment of the sales and advertisement of tobacco has not been proposed yet.

The modified questionnaire had 26 questions in which 16 were open ended and 10 closed ended. 7 questions assessed the details of outlet, 4 questions related to sale and brand of tobacco sold more, 11 questions assessed the promotion as well as advertisement of the tobacco, school type and school no tobacco sign or board was assessed by 2 questions and 2 questions checked for the visit of children to tobacco outlets and their frequency of visit.

The section of outlet details were included in the questions about the outlet licence, type, location, size, and name of outlet (confidentiality maintained). The other section investigated the promotion of tobacco use within 100 meters of each school, including advertisements of tobacco products located at outlets, on billboards and public walls. A question about the offer of free samples was asked. The presence of “No Smoking” and “Age Restriction” signage and the smoked and smokeless tobacco products sold, the location and type of advertisements were also found out. All cigarette advertisements were counted and categorized.

School type categories were primary, middle and high school. Any signs or boards of No tobacco outside the premises of school was assessed. The outlets were categorized as: convenience with or without gas, gas station (only), liquor, small market, supermarket, pharmacy/drug store, general stores, vendors, tea stalls, pan bhandaars, movable stalls and other. To optimize anonymity neither school was identified in the reporting of results. Investigator will be priorly trained.

Display of Board by the educational institutions was also checked. The display and board exhibit should be at a conspicuous place(s) outside the premises, prominently stating that sale of cigarettes and other tobacco products in an area within a radius of one hundred yards of the educational institution is strictly prohibited and that it is an offence punishable with the fine which may extend to two hundred rupees.

Methodology

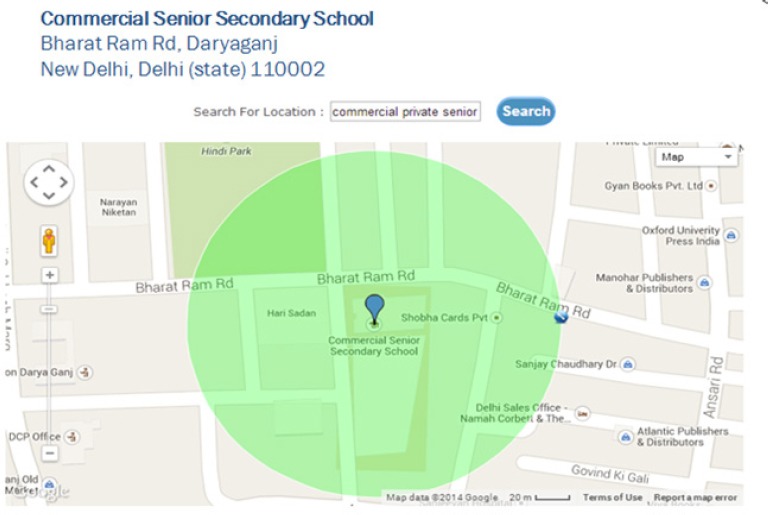

A free map tool was used to draw radius of 100 meters around each randomly selected school (Figure 1). The landmarks were used from this map to locate in all directions the 100 meter range. Help of local rickshaw person was used in the vicinity of the school and asked to takes in all the areas in the 100 meter radius of the school. The areas and lanes were also checked in google maps and satellites. The GPRS was used to locate major land marks in the 100 meter radius. All the outlets which have scope for selling tobacco were screened and the one which sold tobacco were interviewed. The investigator interviewed the salesperson and another observer recorded the details related to the outlet and advertisements.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart Of Study

Figure 2.

Mapping of the 100 Meter Radius Around School

The online map tool was used to locate the 100 meter radius around the schools and the major locations or landmarks in the marked radius. The school name in the above picture was not selected for our study

Statistical analyses of the data was carried out using a computer software programme (SPSS version 17, Chicago, USA). Data was presented as Descriptive analyses, Chi square test used for categorical data and ANOVA for quantitative data. The significance was set at 0.05 and confidence of 95%.

Results

The response rate was 65%. Where there was no response the observation was done and noted for outlet details and ads. All the outlets having scope for sale of tobacco were screened in 100 meters of each of the school. Total of 5 schools were screened in each tehsil.

Out let

Outlet license was present with only 6 (3.47%) outlets which they denied to show on asking. The outlet size ranged from 2ftX2ft to 14ft X 10 ft, with the mean of 10±2 ft x 4 ±4 ft. The point sale of tobacco was more in Tea stalls (30%), followed by vendors (24%), Pan bhandaars (22%), Grocery shops (13%) andjuice stalls (11%). 30% of the outlet was mobile type and where not present at one place. All the outlets were having urban location.

The point sale of tobacco was more in Pahrganj followed by Daryaganj and Karolbagh as shown in Table 2 and when compared showed a statistical significance. Over all sale in central Delhi around 100 meters of selected schools was 41.19%. The highest sale was recorded near MCD schools followed by private and government run schools in all these areas (Table 2). When the different schools were compared for no.of potential outlets it was significantly different in Daryaganj (Chi = 10.595, df=1, p= 0.001, S) and Karolbagh (Chi = 22.557, df=2, p=0.000013, S) and non significant for Paharganj (Chi = 2.306, df=4, 0.679, NS). The same was observed for point sale of tobacco when compared with different schools. Highest being near MCD schools which was significant in Daryaganj (Chi = 8.297, df=4, p= 0.0813, S) and Karolbagh (Chi = 7.34, df=2, p= 0.0255, S) and non significant for Paharganj (Chi = 1.535, df=4, 0.8204, NS).

Table 2.

Distribution of Point Sale of Tobacco in Outlets within 100 Meter of Each School in Central Delhi

| Area | Schools | No.of potential outlets | Point sale of tobacco | Chi square test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | N | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Daryaganj | MCD | 2 | 72 (100) | 30 (41.7) | p= 0.679, NS |

| DOE | 1 | 51 (100) | 23 (45.1) | p= 0.001, S | |

| Private | 2 | 54 (100) | 21 (38.9) | p= 0.742, NS | |

| Total | 5 | 177 (100) | 74 (41.8) | p= 0, S | |

| Paharganj | MCD | 2 | 41(100) | 17 (41.5) | p=0.718, NS |

| DOE | 1 | 16 (100) | 07 (43.8) | p=0.06, NS | |

| Private | 2 | 41(100) | 19 (46.3) | P= 0.96, NS | |

| Total | 5 | 98 (100) | 43 (43.88) | p= 0.0000036, S | |

| Karolbagh | MCD | 2 | 65 (100) | 24 (36.9) | p=1, NS |

| DOE | 1 | 26 (100) | 11 (42.3) | p= 0.554, NS | |

| Private | 2 | 54 (100) | 21 (38.9) | p= 0.014, NS | |

| Total | 5 | 145 (100) | 56 (38.62) | p= 0, S | |

| Total | 420 (100) | 173 (41.19) |

Tobacco

The combined (smoke and smokeless) form of tobacco sale was very high (57%) followed by smokeless form (29%) and smoke form (14%). The brand of smoke form of tobacco so sold more was classic citrus (30%), class plain (25%), gold flake (23%) followed by bidis (21%) and wills (15%). The filter type is not commonly used (30%). The shikar brand (50%) was sold more followed by dilbagh (41%), rajanigandha (33%) and panparag (28%) among smokeless tobacco. No sale of E- Cigarettes were observed.

Advertisement and promotion-

100% absence of any public advertisement was observed. The advertisement or promotion of sales was done mainly in the form of both signs and displays (53%), signs (14%), displays (15%) and only few functional items (2.5%). There were a category of outlets which did not use any form of advertisements (15%). When compared this showed a significant difference (Chi square= 73.2, df=4, p=0, S). The promotion of sales was not present (100%) in these outlets in any form. The average no.of signs and displays seen were 4±2 in all the areas.

The ads were distributed more in both outside and inside of outlet (n= 77.85, 45%) when compared to the exterior (20%) or interior (35%) which when compared showed a significant difference with Chi square= 9.5, df=2, p= 0.0087, S. 58% of the ads were placed above 3 feet followed by below 3 feet (37%) and 5% next to candy which when compared was found to be significant (Chi square= 42.74, df=2, p= 0.000, S). 100% of MCD schools were having No tobacco board and but not complying with the specifications. One private school and DOE school had the board is or signs for the no tobacco.

Over all 40% children were visiting these outlets for tobacco among which more were in Karolbagh area (40%) followed by Paharganj (36%) and Karolbagh (24%) which when compared showed no statistical significance (Chi square= 3.174, df=2, p= 0.15, NS). The total mean no.of students seeking tobacco at these point sale outlets were 15±3.7 students per day. In Karolbagh 6±0.7 students purchased tobacco in one or the other form when compared to Paharganj (5±0.5) and Karolbagh (4±2.5) [ F= 22.060, df= 2, p=0.000, S].

The total signs seen were 67% among which the hoardings (60%) were more commonly observed than boards (40%). The display (68%) of smokeless packets (72%) was far more than the smoke form packets (28%). 3% of displayed items for sale were observed. Cloth printed with brand name (40%) was more commonly seen when compared to engraved pens and boxes (30% each).

Discussion

Tobacco industry marketing encompasses planned efforts to convince people to desire, buy or support tobacco company interests using methods that include paid advertising, price promotions, public relations and distribution of tobacco products and promotional items (William et al., 2009; Cruz, 2009). According to Lovato et al., (2003) these marketing strategies are an important factor affecting individual uptake, maintenance of tobacco use, and they impact the success of comprehensive tobacco control programmes in ways that extend beyond its effect on individual tobacco users. Exposure to point-of sale tobacco promotions influences susceptibility to smoking, smoking initiation, impulse tobacco purchases and undermines quitting (National Cancer Institute. 2008; Paynter and Edwards, 2009).

Hence, this study was done to assess the density of tobacco promotions, advertising and sales in school neighbourhoods of Central Delhi. This was a cross sectional study were coding was done for schools. Central Delhi was chosen for the study as these areas have many government offices, its administrative district, effective law enforcements and famous places of shopping were clustering of many shops and people can be observed. This study is the first to report the impact of tobacco product availability, advertising and other tobacco-outlet related activity within 100 metres of a school in Central Delhi and 3rd of its type in India.

The response rate was 65% in this study and among these 65% sales persons, 25% were not reluctant to respond and were giving vague answers and asking for whether we are authorities to shut down the outlet. In the rest 25%, only observation was done to assess the details related to outlet and advertisements of tobacco and no interview was recorded.

Comparison of our study results with other studies could not be made as there are only two Indian studies (Schensul et al., 2012; Deepal et al.,2012) but with different objectives and a few international data (Ellen et al., 2001; Molly et al., 2008; William et al., 2009; Lisa et al., 2010; April et al., 2010). But these studies showed a different recording criteria as the rules and regulations in these countries differed from our country. The one Indian study was done in Gujarat by Deepal et al., (2012) in rural area and the main aim was to compare the sales nearby two schools and the tobacco consumption rate and pattern of students in these schools. Another study was done in Mumbai by Schensul et al., (2012) but was generalized to all the population and not specific to school areas. Both the studies were done in low income areas. Our study was done in urban set up.

Within the limitations of the study, it was observed that 41.19% of the total potential outlets sold tobacco in central Delhi and was maximum in Paharganj in 100 meters of school. The factors related to maximum sale with minimum no.of outlets may be its location just west of the New Delhi Railway Station. Hence, the flow of population is more. Over the years, Paharganj has become the biggest hotel hub for low-budget foreign tourists in Delhi, though with rising congestion, proliferation of illegal bars and illegal activities like, drug peddling (Bhim and Shardha, 1988). Louisiana study showed 25% of tobacco outlets and ads near 500 meters of school play ground which was very less than our study (Molly et al., 2008)

The more no. of tobacco outlets were observed near MCD schools and Govt schools in Daryaganj. In Paharganj, both the private schools followed by govt school and 1 MCD school had more sale. In Karolbagh highest sale was near a private school and govt school. This shows that the MCD schools having anti tobacco signs did not make much difference for sale in the areas around the school in Daryaganj and Paharganj. However, in Karolbagh area it clearly made a difference in sale. The Sign boards present outside the school was not clear when seen from road and were not according to specifications.

Our study showed most common shops for tobacco sale being tea stalls and vendors which was different from that reported by Deepa et al., (2012) in which paan shops and general stores had maximum availability. In a California study (April et al., 2010) the liquor stores followed by small stores and convenience stores sold more tobacco. In our study licence was seen recorded among 6 outlets, where in 15 claimed to be licensed in another study. The license was not shown in either of the study. Deepa et al., (2012) showed that two outlets displayed both “No Smoking” and “Age Restriction” signage whilst in our study none had these signs. Whereas, two pan shops had displayed and sold kwick nic chewing gums (NRT therapy). Three smokeless tobacco types (gutkha, zarda and khaini) and two smoked tobacco types (cigarette and bidi) were identified in the same study. In our study packets of tobacco with different brand names were identified.

Ads in some or the other form were seen in 70% of the outlets, which is less than the April et al., (2010) (90.1%).21 Both signs and displays were more common and present in exterior and interior areas of outlet as well as 11% had exterior ads which are less compared to our study (20%). Poster or flyers/flags/banners were common (98.8%) in Los angeles, and 71.4% in louisana (Molly, 2008). To measure children’s potential exposure to cigarette advertising, the existence of any advertising materials at or below 3 feet (1 m) from the floor and placement of displays near the candy was noted. 37% of outlet had ads below or equal to 3 feet in our study which was more than the California study (12%).

Placement of ads near candy was seen in 5% of outlets which is more than others studies which reported 1.1% (April Roeseler et al). there were no ads in public places in all the areas screened. This may be due to the guidelines for implementing Article 13 of FCTC. This act describes comprehensive TAPS ban to apply to all form of commercial communication, recommendation or action and all forms of contribution to any event, activity or individual with the aim, effect or likely effect of promoting a tobacco product or tobacco use either directly or indirectly (Monika and Gaurang, 2013; Bhaumik, 2013).

Reviews of tobacco advertising have established that tobacco advertising and promotional activities are important catalysts in the smoking initiation process and impulse buying (Biener et al., 2000; Croucher and Choudhury, 2007; Lovato, 2008; Burton et al., 2012). A previous Indian study by Deepa et al., (2012) established that exposure to tobacco advertisements and receptivity to tobacco marketing was significantly related to increased tobacco use among students. The only advertising venue now allowed in India for the tobacco industry is ‘on boards’ and ‘on-pack’ advertising which was also confirmed by our study with displays and signs of ads. Tobacco packs are important means of advertising for the industry and they employ attractive imagery such as logos, brand names, colours, etc. on the pack for the same.

The theme for the World No Tobacco Day in 2013 (World Health Organization, 2013) was ‘Ban Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship’, the objective being to encourage the Parties to impose a comprehensive TAPS ban and to strengthen efforts to reduce tobacco industry interference in introducing and enforcing such comprehensive bans.

The cross sectional study design precludes inferring causality between the outcomes investigated and independent variables. Larger, more representative sample size may impact on the strength of the results. Self reported tobacco sale to minors is an inherent bias in this study. Though randomly the schools were selected few of the schools were sharing some outlets in 100 meter range. A national study of stores is needed to identify regional or state differences among all types of tobacco products including cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and cigars. In addition, the effects of exposure to tobacco advertising on children and adults should be investigated in order to assess what retail outlet advertising actually “buys” tobacco companies. A committee has to be set up with schools, locals, law enforcers, local political party representatives and parents to taken a combined action to curb this menace of not implementing the laws related to tobacco.

In conclusion, all the screened areas had tobacco outlets with sale of tobacco with signs and displays which were against the rules of COPTA. The boards were major method of signs and packets for display in advertising tobacco at these outlets. Only MCD schools had anti tobacco board and no outlets had any form of anti tobacco board. Children do visited these outlets seeking tobacco but the reporting by outlet sales person may be under reported.

References

- Aitken PP, Eadie DR. Reinforcing effects of cigarette advertising on underage smoking. Br J Addiction. 1990;85:399–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anon . Overland Park. Kansas: Intertec Publishing; 1999. The 1999 annual report of the promotion industry, a PROMO magazine special report; pp. 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- April R, Ellen CF, Tess BC. Tobacco marketing in California and implications for the future. Tobacco Control. 2010;19:21–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaumik S. Private member’s bill proposes plain packaging of tobacco products in India. BMJ. 2013;346:953. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhim S, Sharada P. Drug danger and social behaviour: new challenges ISBN 81-85320-00-4. 1988:138. [Google Scholar]

- Bhojani UM, Chander SJ, Devadasan N. Tobacco use and related factors among pre-university students in a college in Bangalore, India. Natl Med J India. 2009;22:294–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campaign for Tobacco free kids. Tobacco control laws. Country details for India. International legal consortium Attorneys. [accessed 22/2/2012]. http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/legislation/country/India/summary/

- Conrad KM, Flay BR, Hill D. Why children start smoking cigarettes: predictors of onset. Br J Addict. 1992;87:1711–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz TB. Monitoring the tobacco use epidemic IV. Tobacco industry data sources and recommendations for research and evaluation. Prev Med. 2009;48:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deepa P, Saba K, Ray C. Tobacco promotion and availability in school neighborhoods in India: a cross-sectional study of their impact on adolescent tobacco use. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:4173–6. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.8.4173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellen CF, Kurt MRl, Nina S, et al. Cigarette advertising and promotional strategies in retail outlets: results of a statewide survey in California. Tobacco Control. 2001;10:184–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Free map tool. http://www.Freemaptools.com/radius-around-point.htm .

- Gilpin EA, Pierce JP. Trends in adolescent smoking initiation in the United States: is tobacco marketing an influence? Tobacco Control. 1997;6:122–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.2.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global youth tobacco survey. Findings from the global youth tobacco survey (GYTS) and global school personnel survey (GSPS) India 2003-2009. Tobacco use among students and teachers. WHO, Ministry of health and welfare of India; http://www.searo.who.int/india/tobacco/GYTS_India_report_2003-09.pdf?ua=1 . [Google Scholar]

- Government of NCT of Delhi. [Accessed 20/02/2012]. http://www.delhi.gov.in/wps/wcm/connect/doit_revenue/Revenue/Home/Organization+Setup/List+of+villages(11+District+Wise)/

- Jackson C, Dickinson DM. Developing parenting programs to prevent child health risk behaviors: a practice model. Health Educ Res. 2009;24:1029–42. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisa H, Nina C, Schleicher E, et al. A longitudinal study of exposure to retail cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2010;126:232–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovato C, Linn G, Stead LF, et al. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviors. [accessed 4 Apr 2009];Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 4:CD003439. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003439. http://mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD003439/pdf_fs.html . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2014: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for social research, The university of Michigan; 2015. available at http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs.html#monograp hs . [Google Scholar]

- Molly MS, Deborah AC, Matthias S. Alcohol and tobacco marketing: An evaluation of compliance with restrictions on outdoor ads. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monika A, Gaurang P, Nazar D. Prohibiting tobacco advertising, promotions & sponsorships: Tobacco control best buy. Indian J Med Res. 2013;137:867–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National tobacco control cell. Operational guidelines, national tobacco control programme. Ministry of health and family welfare government of India. 2012. http://mohfw.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/2945310979Operational%20Guidelines.pdf .

- National Cancer Institute. The role of media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. Tobacco control monograph No. 19. Bethesda, MD: US department of health and human Services, national Institutes of Health, national cancer institute. NIH Pub No. 07-y6242; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Blizzard L, Patton G, et al. Parental smoking and smoking experimentation in childhood increase the risk of being a smoker 20 years later: the Childhood determinants of adult health study. Addiction. 2008;103:846–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;1:25–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Gilpin E, Burns DM, et al. Does tobacco advertising target young people to start smoking?. Evidence from California. JAMA. 1991;266:3154–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Point of purchase advertising institute. The point-of purchase advertising industry fact book. Englewood, New Jersey: The point of purchase advertising institute; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Redmond WH. Effects of sales promotion on smoking among U.S. ninth graders. Prev Med. 1999;28:243–50. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resource centre for tobacco free India. Voluntary health association of India. http://www.rctfi.org/goi_notification_new.htm .

- Schensul JJ, Nair S, Bilgi S, et al. Availability, accessibility and promotion of smokeless tobacco in a low-income area of Mumbai. Tob Control. 2013;22:324–30. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sushma C, Sharang Pan masala advertisements are surrogate for tobacco products. Indian J Cancer. 2005;42:94–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-509x.16699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner KE. Selling smoke: cigarette advertising and public health. Washington, DC: American public health association; 1986. pp. 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- William JM, Ritesh M, Yao L, et al. Density of tobacco retailers near schools: Effects on tobacco use among students. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:2006–13. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.145128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for implementation of article 13 of the WHO framework convention on tobacco control tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship. 2013. [accessed on April 6, 2013]. Available from: http:/www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/article_13.pdf .