Abstract

Context:

Nutritional risk assessment must be done on all critically ill patients. Malnutrition in intensive care unit (ICU) patients is associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Traditional scoring systems cannot be used for screening in mechanically ventilated (MV) patients because these patients are unable to provide information on their history of food intake and weight loss. The Nutrition Risk in Critically ill (NUTRIC) score is the appropriate nutritional assessment tool in MV patients.

Aims:

This prospective observational study was conducted to identify the nutritional risk in MV patients using modified NUTRIC (mNUTRIC) score (with the exception of interleukin-6).

Patients and Methods:

All adult patients admitted to the ICU and required MV for more than 48 h were included in the study. Data were collected on variables required to calculate mNUTRIC score. Patients with mNUTRIC score ≥5 are considered at nutritional risk. Outcome data were collected on ICU length of stay, ventilator-free days, and mortality.

Results:

A total of 678 MV patients fit into the inclusion criteria. Majority of the patients were male (67%). Mean age of the patients was 55 years. About 288 (42.5%) patients were at high nutritional risk (mNUTRIC score ≥5). Patients with high mNUTRIC score ≥5 had longer mean ICU average length of stay of 9.0 (±4.2) versus 7.8 (±5.8) mean (± standard deviation) days (P < 0.01) and higher mortality 41.4% versus 26.1% (P < 0.0) compared to patients with low NUTRIC score (≤4). High mNUTRIC score (≥5) predicted mortality with area under the curve of 0.582 (95% confidence interval 0.535-0.628).

Conclusions:

Nearly 42.5% of MV patients admitted to ICU were at nutritional risk, and high mNUTRIC score was associated with increased ICU length of stay and higher mortality.

Keywords: Mechanically ventilated patients, Nutrition Risk in Critically ill score, nutritional assessment

INTRODUCTION

Nutritional support is an essential component of patient care in critically ill patients. Prevalence of malnutrition in intensive care unit (ICU) patients varies between 39% and 50%; it depends on the screening tool employed and the population studied.[1,2,3] Malnutrition in critically ill patients is associated with an increased occurrence of nosocomial infections, prolonged hospitalization, and higher mortality.[3,4] Acutely ill patients are under stress, this initiates a variety of metabolic responses such as stress hyperglycemia and skeletal muscle wasting, these patients need to be started on early nutritional support to attenuate the metabolic response to stress and prevent oxidative cellular injury.[5]

Nutritional assessment is the cornerstone in identifying patients at risk of malnutrition and it has to be done within 48 h of hospital admission. A number of nutritional assessment tools are available for screening patients and they use various criteria to identify patients at nutritional risk including anthropometric data, physical examination, history of weight loss, dietary intake, and clinical diagnosis.[6,7,8] Most of the nutritional screening tools available are validated in hospitalized patients; no specific tool is available for ICU patients.[9] Nutritional screening in ICU patients is challenging because many of the parameters such as accurate history of dietary intake and weight loss may be difficult to obtain, as most of the patients are on mechanical ventilation and sedation. Changes in weight can be influenced by the edema due to underlying disease and large volume fluid resuscitation required to maintain hemodynamic stability, consequently muscle and fat-wasting evaluation becomes more difficult. Many of the nutritional tools available do not include inflammatory process and hypermetabolic status in ICU patients. Heyland et al. introduced the Nutrition Risk in Critically ill (NUTRIC) score, which identifies patients who will be benefited from aggressive nutrition by linking starvation, inflammation, and outcomes.[10]

Nutritional assessment in mechanically ventilated (MV) patients is a difficult task; the reasons being communication barrier in obtaining dietary history and evaluation of muscle wasting can be misleading due to the associated swelling and edema in these patients. Data on nutritional assessment in MV patients using NUTRIC score are limited.[11] This study was conducted to identify the prevalence of nutritional risk in MV ICU patients with modified NUTRIC (mNUTRIC) score.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This was a prospective observational study conducted in a multidisciplinary ICU for 2 years (January 2014 – December 2015). Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained for the study. All adult patients admitted to the ICU and required MV for more than 48 h were included in the study. Patients readmitted to the ICU during the same hospital admission and patients transferred to other ICU/hospitals were excluded from the analysis. mNUTRIC score (without using interleukin-6 values) was used to identify patients at nutritional risk with the following variables: age, number of comorbidities, days from hospital to ICU admission, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores at admission. Patients were classified as having a high mNUTRIC score if the sum was ≥5 and these patients were classified as having a higher risk of malnutrition and low score if the mNUTRIC score is ≤4. ICU physicians did the NUTRIC score for all MV patients. Data collection was done on demography, parameters required to calculate NUTRIC scores, ICU average length of stay (ALOS), ventilator-free days, and mortality.

The collected data were analyzed with IBM, SPSS (IBM Corp., Statistics for Windows, version 23.0, Armonk, NY). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables were expressed as percentage. To find the significant difference between the bivariate samples in independent groups, unpaired sample t-test was used and Chi-square test was used to find the significance in categorical data. The receiver operator characteristic curve analysis was used to find the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) on comparison of outcome and NUTRIC score. In all the above statistical tools, P = 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

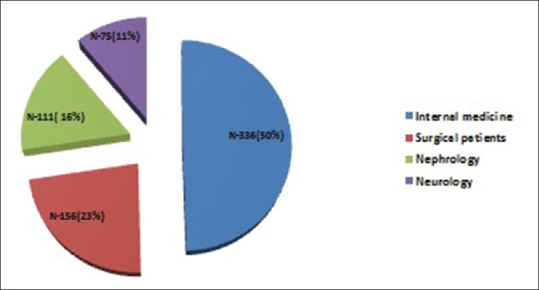

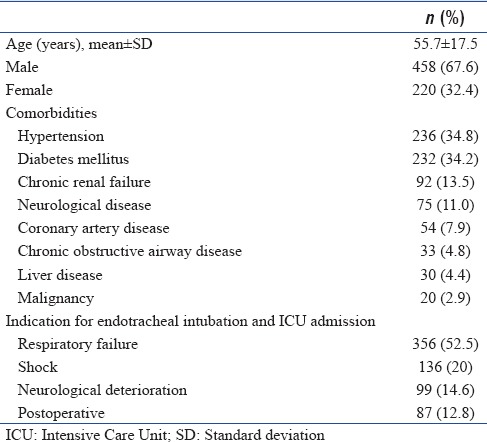

A total of 784 MV (>48 h) patients were admitted to the ICU during the study period. One hundred and six patients were excluded from the study; thirty patients were readmitted during the same hospital stay and 76 patients were transferred to other ICUs. Data of 678 patients were analyzed. Mean age of patients was 55.7 years (±17.5) (± SD). Most of the patients were male, i.e., 458 (67.6%). Majority of patients were medical cases and 23% of patients were surgical admissions [Figure 1]. Diabetes mellitus (34.8%), hypertension (34.2%), and chronic renal failure (13.5%) were the most common comorbid illnesses [Table 1]. The most common reasons for mechanical ventilation and ICU admissions were respiratory failure (52.5%) followed by shock (20%), neurological deterioration (14.6%), and surgical postoperative patients (12.8%).

Figure 1.

Case mix of patients

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n=678)

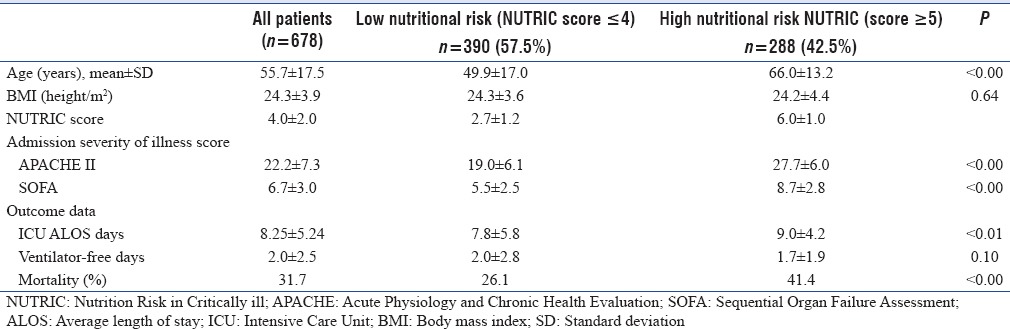

Mean APACHE II and SOFA scores of these patients were 22.2 (±7.3) (± SD) and 6.7 (±3.0) (± SD), respectively [Table 2]. Mean ICU length of stay and ventilator-free days were 8.2 (±5.2) (± SD) and 2.0 (±2.5) (± SD) days, respectively. Overall mortality was 31.5%. A total of 288 (42.5%) patients were at high nutritional risk (mNUTRIC score ≥5). Patients with high mNUTRIC score ≥5 had longer mean ICU ALOS of 9.0 (±4.2) versus 7.8 (±5.8) mean (± SD) days (P < 0.01) and higher mortality of 41.4% versus 26.1% (P < 0.0) compared to patients with low NUTRIC score (≤4) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of outcomes of patients with low Nutrition Risk in Critically ill score and high Nutrition Risk in Critically ill score

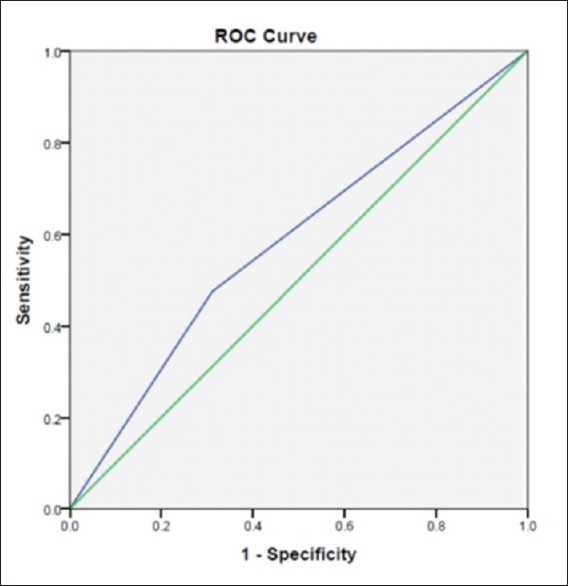

High mNUTRIC score (≥5) predicted mortality with area under the curve (AUC) of 0.582 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.535-0.628) [Figure 2]. The PPV and the NPV of NUTRIC score to predict mortality were 47.4% and 68.9%, respectively, with a sensitivity and specificity of 41.5% and 73.8%. mNUTRIC score on a full scale (0-9) predicted mortality with AUC of 0.642 (CI 0.689-0.593).

Figure 2.

Performance of the high Nutrition Risk in Critically ill score on a scale of 5–9 to predict intensive care unit mortality in mechanically ventilated patients admitted to intensive care unit

DISCUSSION

Nutritional screening in MV patients is a cumbersome task, many of the traditionally used nutritional screening tools such as Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool, Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS 2002), and Subjective Global Assessment use patients’ anthropometric measurements and history of dietary intake/weight loss to identify patients at nutritional risk.[6,7,8] Anthropometric measurements can be unreliable in MV-ICU patients because of the underlying edema and a reliable history of dietary intake/weight loss is difficult to obtain in MV because these patients are often sedated. The NUTRIC score was designed to identify nutritional risk in critically ill patients; hence in this study, we used NUTRIC score to identify nutritional risk in MV patients.[10]

In this study, 42.5% of MV patients admitted to ICU are at nutritional risk (NUTRIC score ≥5). Similarly, Mendes et al.[3] reported that 48.6% of patients were at high nutritional risk from Portuguese ICU using NUTRIC scores. The prevalence of malnutrition in ICU patients varies from 38% to 78% and it depends on the nutritional screening tools employed.[12] Mean NUTRIC score in this study was 4.0, which was less than the original validation study of NUTRIC score (4.7), this might be due to lower age of study patients (55.7 vs. 65.0 years) compared to original study by Heyland et al.[10] APACHE II (22.2 vs. 23) and SOFA (6.7 vs. 7) scores in our study were similar to that of the original validation study.[10]

Mortality in our study was 31.4%, which was almost similar to the second validation study of NUTRIC score (29%) as reported by Rahman et al.[13] In contrast, Moretti et al.[11] in a similar study on MV patients using NUTRIC scores reported higher ICU mortality (53%) in their patients. Patients with high NUTRIC score had higher mortality and increased ICU length of stay, similar results were reported by Mendes et al.[3] using NUTRIC score in their ICU population.

The major limitation of our study was we did not calculate the nutritional support provided to the patients as this was not the main aim of the study. This study was conducted primarily to identify the prevalence of nutritional risk among MV patients using NUTRIC score.

CONCLUSIONS

The prevalence of nutritional risk in MV patients using mNUTRIC score was 42.5%. High mNUTRIC score was associated with increased ICU length of stay and higher mortality.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chakravarty C, Hazarika B, Goswami L, Ramasubban S. Prevalence of malnutrition in a tertiary care hospital in India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2013;17:170–3. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.117058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheean PM, Peterson SJ, Gurka DP, Braunschweig CA. Nutrition assessment: The reproducibility of subjective global assessment in patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:1358–64. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendes R, Policarpo S, Fortuna P, Alves M, Virella D, Heyland DK. Portuguese NUTRIC Study Group. Nutritional risk assessment and cultural validation of the modified NUTRIC score in critically ill patients – A multicenter prospective cohort study. J Crit Care. 2017;37:249. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correia MI, Waitzberg DL. The impact of malnutrition on morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay and costs evaluated through a multivariate model analysis. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:235–9. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(02)00215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, Connolly B, Ratnayake G, Chan P, et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. JAMA. 2013;310:1591–600. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Detsky AS, McLaughlin JR, Baker JP, Johnston N, Whittaker S, Mendelson RA, et al. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1987;11:8–13. doi: 10.1177/014860718701100108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondrup J, Rasmussen HH, Hamberg O, Stanga Z. Ad Hoc ESPEN Working Group. Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): A new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:321–36. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(02)00214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elia M. The ‘MUST’report: Nutritional screening of adults: A multidisciplinary responsibility. A report by the Malnutrition Advisory Group of the British Association for Patenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN) Marinos Elia, British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, Guaitoli PR, Jansma EP, de Vet HC. Nutrition screening tools: Does one size fit all? A systematic review of screening tools for the hospital setting. Clin Nutr. 2014;33:39–58. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Jiang X, Day AG. Identifying critically ill patients who benefit the most from nutrition therapy: The development and initial validation of a novel risk assessment tool. Crit Care. 2011;15:R268. doi: 10.1186/cc10546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moretti D, Bagilet DH, Buncuga M, Settecase CJ, Quaglino MB, Quintana R. Study of two variants of nutritional risk score “NUTRIC” in ventilated critical patients. Nutr Hosp. 2014;29:166–72. doi: 10.3305/nh.2014.29.1.7001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lew CC, Yandell R, Fraser RJ, Chua AP, Chong MF, Miller M. Association between malnutrition and clinical outcomes in the Intensive Care Unit: A systematic review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016:pii: 0148607115625638. doi: 10.1177/0148607115625638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahman A, Hasan RM, Agarwala R, Martin C, Day AG, Heyland DK. Identifying critically-ill patients who will benefit most from nutritional therapy: Further validation of the “modified NUTRIC” nutritional risk assessment tool. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:158–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]