Abstract

Background:

Critical care services are essential for the subset of obstetric patients suffering from severe maternal morbidity. Studies on obstetric critical care are important for benchmarking the issues which need to be addressed while managing critically ill obstetric patients. Although there are several published studies on obstetric critical care from India and abroad, studies from Eastern India are limited. The present study was conducted to fill in this lacuna and to audit the obstetric critical care admissions over a 5 years’ period.

Settings and Design:

Retrospective cohort study conducted in the general critical care unit (CCU) of a government teaching hospital.

Materials and Methods:

The records of all obstetric patients managed in the CCU over a span of 5 years (January 2011-December 2015) were analyzed.

Results:

During the study, 205 obstetric patients were admitted with a CCU admission rate of 2.1 per 1000 deliveries. Obstetric hemorrhage (34.64%) was the most common primary diagnosis among them followed by pregnancy-induced hypertension (26.83%). Severe hemorrhage leading to organ failure (40.48%) was the main direct indication of admission. Invasive ventilation was needed in 75.61% patients, and overall obstetric mortality rate was 33.66%. The median duration (in days) of invasive ventilation was 2 (interquartile range [IQR] 1-7), and the median length of CCU stay (in days) was 5 (IQR 3-9).

Conclusions:

Adequate number of critical care beds, a dedicated obstetric high dependency unit, and effective coordination between critical care and maternity services may prove helpful in high volume obstetric centers.

Keywords: Critical care, hemorrhage, obstetric, pregnancy-induced hypertension, ventilation

INTRODUCTION

Maternal mortality is an important health indicator for any country and maternal, and child health is a subject of national focus. Although good perinatal outcome depends on socioeconomic factors and orchestrated functioning of various levels of population and hospital based care, the importance of obstetric critical care services to manage the severely sick pregnant or postpartum patients cannot be undermined.

“Maternal obstetric morbidity” has been defined as morbidity from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.[1] “Severe maternal morbidity,” a phrase coined by Mantel et al.[2] and preferred to the often used attractive phrase “near-miss,” is defined as “a very ill pregnant or recently delivered woman who would have died had it not been but luck and good care was on her side.” The incidence of severe maternal morbidity has been shown to relate to maternal mortality. Although the objective criteria for defining severe maternal morbidity vary between studies, its prevalence ranges from 0.05%-1.7% in developed countries[3,4] and 0.6%-8.5% in resource-limited countries.[5,6] Critical care services are important for this subset of obstetric patients and critical care unit (CCU) admission may be considered as an objective marker of severe maternal morbidity.[7,8]

Managing critically ill obstetric patients is a challenge to intensivists, anesthesiologists, and obstetricians because of the complicated interactions of pathological processes with the physiological changes of pregnancy. Studies on obstetric critical care are important to identify the critical care issues which need to be promptly addressed while managing severe maternal morbidity cases. In 1998, Scarpinato[9] pointed out the paucity of published data on obstetric critical care and suggested for an increase in reporting. Although over the last decade, many studies on obstetric critical care have been published from several countries[10,11,12,13,14,15,16] and from various parts of India,[17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] reports from Eastern India[25] are scarce. The present study was conducted to fill in this lacuna. It is noteworthy that the terms CCU and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) used in this report are synonymous.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study is a retrospective cohort study analyzing all obstetric critical care admissions in a five-bedded general CCU of a 1400-bedded government teaching hospital over a span of 5 years (January 2011-December 2015). The CCU is a mixed medical and surgical ICU under the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, where obstetric patients are managed jointly by an intensivist, anesthesiologists, and obstetricians. The hospital is a high volume obstetric center. However, in the absence of a dedicated obstetric high dependency unit (HDU), the general CCU takes the main responsibility of catering to the severely sick obstetric patients.

Data collection

The medical records of all obstetric patients (pregnant or within to 6 weeks postpartum) admitted to the CCU during the study were analyzed along with simultaneous analysis of CCU databases. The following data were recorded and analyzed for each patient: age, parity, primary diagnosis (obstetric or nonobstetric disease process identified to be responsible for the patient's critical illness), indication of CCU admission, obstetric interventions performed, critical care interventions performed during CCU stay (mechanical ventilation, central venous catheterization, invasive arterial pressure monitoring, hemodialysis), duration of mechanical ventilation, length of CCU stay and outcome.

Statistical analysis

All categorical data were expressed as proportions or percentages. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 20.0, IBM Corporation, New York, USA). The categorical data analysis was done either by Fischer's exact test or Chi-square test, as applicable. The numerical data were analyzed by unpaired t-test or ANOVA for normal distribution and by Mann-Whitney U-test or Kruskal-Wallis H-test if it was not distributed normally. The statistical significance implies P < 0.05.

The Institutional Ethics Committee approved the study.

RESULTS

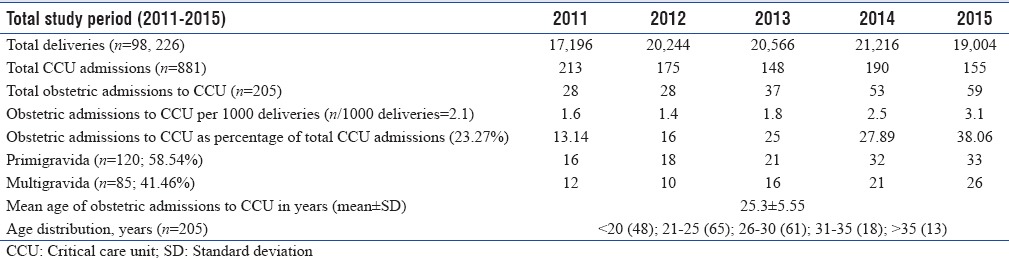

During the study, 205 obstetric patients were admitted to the CCU (23.27% of total CCU admissions). There were 98,226 deliveries in this period, and the CCU admission rate was 2.1 per 1000 deliveries. The mean maternal age (in years) was 25.3 ± 5.55 (mean ± standard deviation). All but one were postpartum patients, and 58.54% (120/205) patients were primigravida. The total and yearly data are shown in Table 1. The distribution of primary diagnosis and indications for CCU admission is shown in Table 2a and b; obstetric and critical care interventions and outcome data are shown in Table 3a–c.

Table 1.

Year-wise distribution of total deliveries, total and obstetric admissions to critical care unit, age, and parity

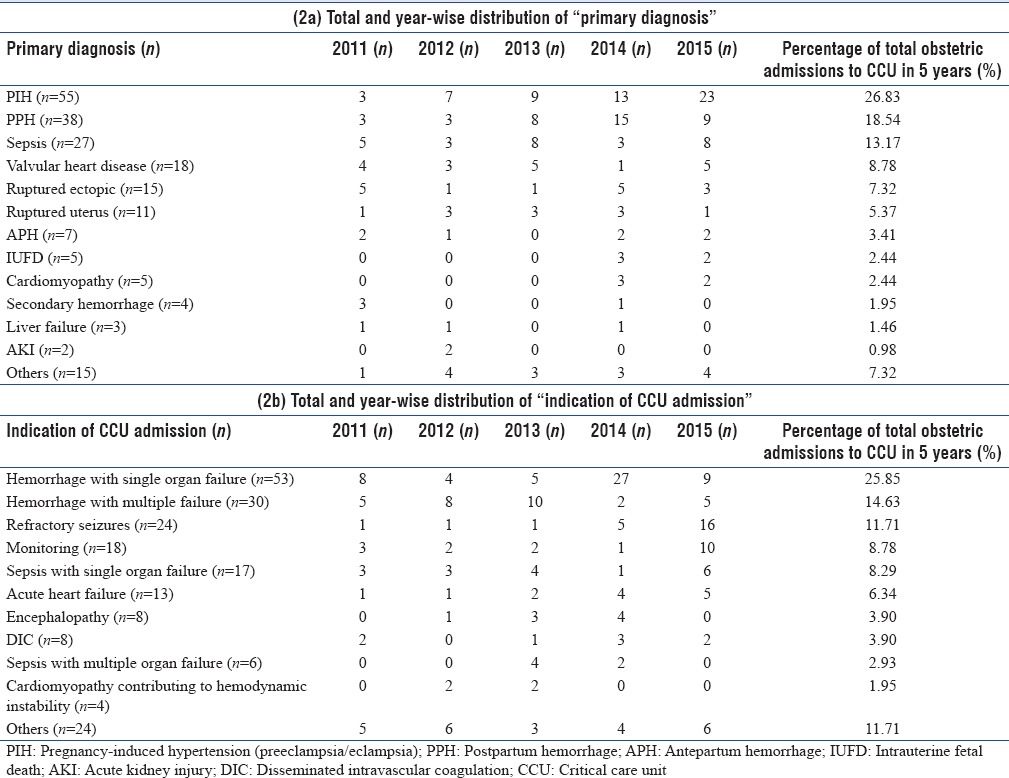

Table 2.

Total and year-wise distribution of “primary diagnosis” (2a) and “indication of critical care unit admission” (2b)

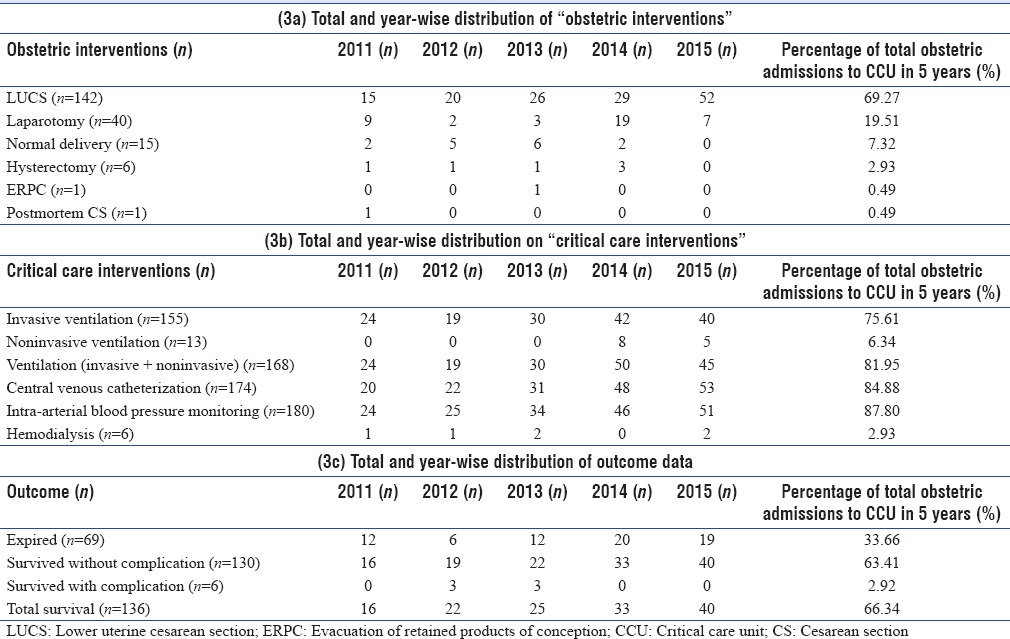

Table 3.

Total and year-wise distribution of obstetric interventions (3a), critical care interventions (3b), and outcome (3c)

Obstetric hemorrhage (71/205; 34.64%) in totality (postpartum hemorrhage [PPH] 18.54%, ruptured ectopic 7.32%, ruptured uterus 5.37%, and antepartum hemorrhage 3.4%) was the most common primary diagnosis in the present study followed by pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) including preeclampsia and eclampsia (55/205; 26.83%). Hemorrhage causing single or multiple organ failure (83/205; 40.48%) was the main direct indication of CCU admission. Mechanical ventilation was needed in 168 patients (81.95%), majority of whom received invasive ventilation (155/205; 75.61%). The median duration (in days) of invasive ventilation was 2 (interquartile range [IQR] 1-7). The obstetric mortality rate was 33.66% (69/205). Median stay (in days) in the CCU was 5 (IQR 3-9).

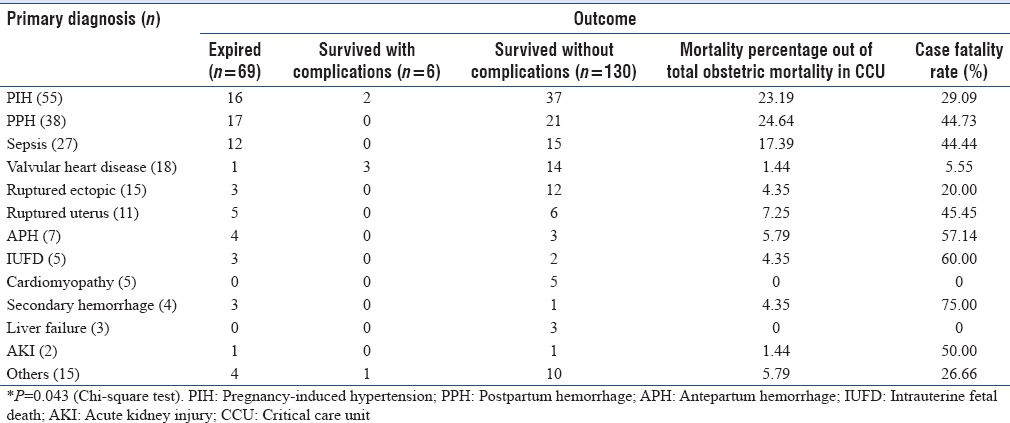

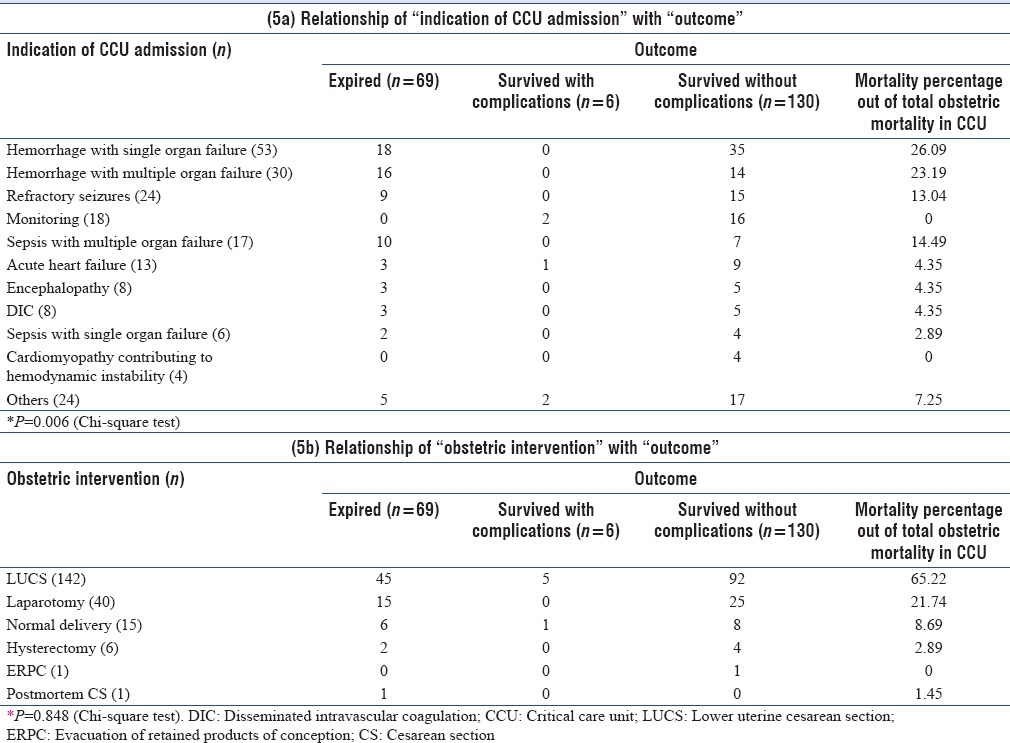

Both primary diagnosis and indication of CCU admission were associated with outcome (P = 0.043 and P = 0.006, respectively; Chi-square test) [Tables 4 and 5a]. Major obstetric hemorrhage with organ failure was the major cause of mortality (34/69; 49.27%) followed by sepsis with multiple organ failure (10/69; 14.47%). No association was found between obstetric intervention performed and outcome (P = 0.848; Chi-square test) [Table 5b].

Table 4.

Relationship of “primary diagnosis” with “outcome”

Table 5.

Relationship of “indication of critical care unit admission” with “outcome” (5a) and “obstetric intervention” with “outcome” (5b)

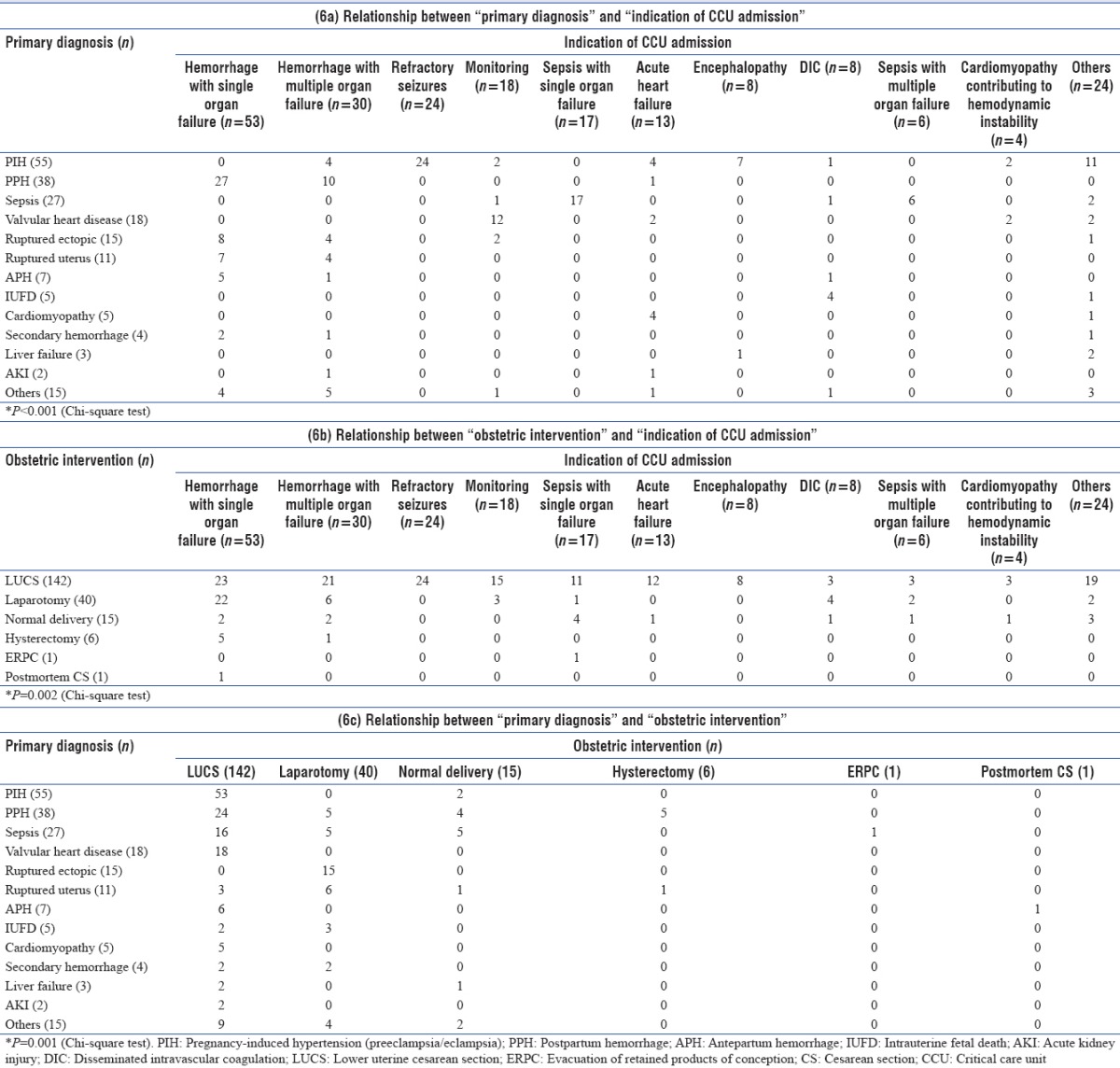

The primary diagnosis was found to have an association with indication of CCU admission (P < 0.001; Chi-square test) [Table 6a]. Patients with PIH were mostly admitted for refractory seizures (24/55; 43.64%) and PPH for severe hemorrhage with single (27/38; 71.05%) or multiple (10/38; 26.31%) organ failure. Septic patients were also mainly admitted with single (17/27; 62.96%) or multiple organ failure (6/27; 22.22%) and patients with valvular heart diseases for postoperative monitoring (12/18; 54.54%). Although patients with primary diagnosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy were mostly admitted for acute heart failure (4/5; 80%), coexistent cardiomyopathy causing hemodynamic instability was the indication for CCU admission in two PIH patients and two patients with valvular heart disease. Disseminated intravascular coagulation was the main indication of admission in patients with intrauterine fetal death. Both indication of CCU admission and primary diagnosis were found to be associated with obstetric interventions performed (P = 0.002 and P = 0.001 respectively, Chi-square test) [Table 6b and c], lower uterine cesarean section (LUCS) being the most common intervention. One patient with a primary diagnosis of ruptured uterus based on scar dehiscence in a postcesarean section pregnancy was managed conservatively when no continuous vaginal bleeding was noticed after vaginal delivery.

Table 6.

Relationship between “primary diagnosis” and “indication of critical care unit admission” (6a), “obstetric intervention” and “indication of critical care unit admission” (6b), “primary diagnosis” and “obstetric intervention” (6c)

DISCUSSION

The mean age and the age distribution of the critically ill obstetric patients in the present study correlate with other contemporary Indian studies,[17,20,21,22,23,24] but studies from abroad report a higher maternal age.[11,13,14,15] Although advanced maternal age has not been shown to be uniformly associated with CCU admissions and a median age of 30 years is consistent with birth age patterns in developed countries,[27] the noteworthy point in Indian studies is the need of critical care in the patients well under thirty. Socioeconomic factors, early age of marriage, poor access to antenatal services, and suboptimal obstetric care in certain remote parts of the country may all contribute to this.

Unlike studies reporting a higher percentage of multiparous admissions,[14,20,23,25] our study reports a higher percentage of primigravida. This probably correlates with a high percentage of patients being admitted with complications of PIH in our CCU, primiparity being a recognized risk factor of PIH. Although our study had an unusually high representation of postpartum patients, postpartum predominance is almost uniform among all studies from India and abroad.[11,13,15,19,20,22,24,25] Bhadade et al.[18] reported a very high antepartum admission percentage of 66.39%, but their report is from an exclusively medical ICU, where most admissions were for indirect obstetric indications with hepatitis E in pregnancy being the most common (36.8%).

Pollock et al.,[27] in their systematic review, showed that there was no difference in ICU admission per 1000 deliveries between developed (median 3 [IQR 0.7-8.8]) and developing (median 2.7 [IQR 1.3-3.5]) countries. The CCU utilization rate of 2.1 per 1000 deliveries in our study, albeit low, is more or less in keeping with the values from developing countries studied in the review[27] and other recent Indian studies, which mostly reported a rate below 10 per 1000 deliveries.[17,19,20,21,22,25,26] However, differences in case mix, obstetric and critical care protocols, facilities and bed strengths may be responsible for a very high ICU utilization rate of 28 and 54 per 1000 deliveries reported in two Indian studies.[23,24] Considering the well-recognized differences in access to health-care facilities, severity of illness at the time of seeking medical help, and adequacy of ICU beds between developed and resource-limited countries, the similarity between our CCU admission rate and those from developed countries[12,15,16] may appear paradoxical. However, this may be explained by the shortage of beds in our unit, compelling us to sometimes manage patients not needing very aggressive supports in other intensive care areas of the hospital on emergent basis (e.g., surgical ICU, trauma ICU, and respiratory care unit) and in the absence of a dedicated obstetric HDU, even in the labor room recovery with coordinated efforts of obstetric, anesthesiology, and critical care teams. This subset of patients was not included in the analysis, and it might be a limitation of our study.

The most common primary diagnosis leading to critical care admission has hovered between obstetric hemorrhage[11,12,13,15,17,20,21,23,25] and PIH[14,16,18,19,22,24] in almost all the studies from India and abroad. Our CCU patients had obstetric hemorrhage as the most common primary diagnosis followed by PIH. Hemorrhage with single or multiple organ failure was the main direct indication of CCU admission, cardiovascular and respiratory failure being the most common organ systems failing. In the study by Togal et al.,[14] although the main primary diagnosis for ICU admission was PIH, the main cause of death was hemorrhage. In our study, although the main indication of CCU admission among PIH patients was refractory seizures in eclamptics (25/55; 43.64%), four PIH patients (4/55; 7.27%) were admitted for severe hemorrhage. Sepsis, obstetric or nonobstetric, is increasingly being responsible for CCU admissions in obstetric patients worldwide. Even in studies from developed countries, significant percentages of obstetric critical care admissions (5%;[10,11] 6.6%;[12] 10%;[15] 7.1%[16]) were due to sepsis. Although two Indian studies report a very low rate of sepsis (2.45%[18]; 1.6%[23]), the overall trend among other studies[17,20,21,24,25] is a percentage of around 10%. Gombar et al.[22] even reports a sepsis admission rate as high as 27.15%. The finding of sepsis admissions of 13.17% in our study correlates with the general Indian scenario.

The 69.27% LUCS rate among obstetric patients admitted to our CCU is almost equal to the LUCS rate of 70% reported by Pollock et al.[27] in their systematic review and similar to studies by Sriram and Robertson[11] and Leung et al.[13] Although our study has revealed an association of LUCS with the primary diagnosis and indication of CCU admission, but no association with mortality, the influence of cesarean section on maternal illness is unclear.[27] In some patients, critical illness might have necessitated an LUCS while in others, critical illness might have resulted from complications of LUCS.

A high rate of invasive ventilation (75.61%) in the present study reflects the severity of illness of patients admitted in our CCU. The tertiary referral center status of our hospital and prioritization of obstetric patients needing organ support for admission to our general CCU might also have contributed to the high ventilation rate. Overall, the ventilation rate among obstetric patients is variable in studies from outside India with Zwart et al.[12] reporting a rate of 34.8%, Crozier and Wallace 45%,[15] Leung et al. 58%,[13] Sriram and Robertson 61%,[11] and the team of Togal et al.[14] a rate as high as 85%. Our high ventilation rate nearly matches the Indian reports by Ashraf et al. (85%)[21] and Jain et al. (94.4%),[26] but is higher than that reported in many other Indian studies.[18,19,23,24] The median duration (in days) of ventilation of 2 (IQR 1-7) in our study closely correlates most Indian studies.[17,21,22] The high central venous catherization rate (84.88%) in our study, although similar to an Indian study headed by Bhadade et al. (82.8%),[18] is much higher than that in studies from abroad.[11,12,13,15] This high rate was mainly for taking advantage of multiple venous accesses for unstable patients. A high rate of arterial cannulations, similar to other studies[11,13,15] from abroad, reflects our practice of invasive blood pressure monitoring in most of the CCU patients. The low percentage of patients needing hemodialysis (2.93%) in our study is probably explained by the finding of cardiovascular and respiratory failures as the most common organ failures. Interestingly, our hemodialysis rate was very similar to studies from abroad.[12,13,14,15] In general, the Indian studies report a hemodialysis rate of <10%, with some reporting slightly higher percentages than ours (7.7%;[20] 7.4%[25]) while some similar to ours (2.5%[24]). Only, Bhadade et al.[18] reported an exceptionally high percentage of 38.88% from an exclusively medical ICU where antepartum patients with medical diseases were the main admissions.

It has been recognized that the maternal mortality among critically ill obstetric patients in developing countries is higher than developed nations. Multiple socioeconomic and healthcare-related factors are responsible for this disparity. Studies by Sriram and Robertson[11] and Crozier and Wallace[15] did not report even a single maternal death, and the mortality rate was consistently below 5% in other reports from ICUs of developed countries.[10,12,16] The CCU obstetric mortality rate of 33.66% in our study matches with most of the contemporary Indian studies.[17,18,19,20,22,26] A low mortality rate of 6.5% reported by Harde et al.[23] from a postanesthesia ICU may not be a representation of maternal mortality in a general CCU and a study by Bhadade et al.[18] from the medical ICU of the same institute reports a high maternal mortality rate of 30.3%. Like many studies from India and abroad,[12,14,20,21,25,26] obstetric hemorrhage with organ failure was the major cause of mortality in our study, being responsible for 49.18% of maternal deaths in CCU and PPH (24.64%) comprised most of these hemorrhage fatalities. Other major causes of mortality in our study were complicated PIH (23.19%) and sepsis with organ failure (17.39%). Complications of PIH have been reported as the major direct obstetric cause of death in some Indian studies[18,24] while some report a quite high percentage of sepsis-related deaths.[22,25] Out of the 136 patients who survived in our study, six survived with complications in the form of functional and physical disabilities. Two of these patients were eclamptics who had cognitive deficits at CCU discharge, one patient had persistent hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy after cardiac arrest, and three patients with acute kidney injury remained dialysis dependent. Similar residual disabilities have been reported by Sriram and Robertson[11] in their eight years’ Australian audit. Due to the quick reversibility of illness in most of the young obstetric patients, the average length of ICU stay is in general short in this patient group. The median length of CCU stay (in days) of 5 (IQR 3-9) in the present study nearly matches many other studies from around the world and India.[12,13,14,22,23,26] However, an even shorter length of ICU stay of below 2 days has also been reported both from India[17] and abroad.[10,11,15]

A general limitation of studies on obstetric critical care is the controversy regarding applicability of the most commonly used ICU severity scoring systems, for example, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation or Simplified Acute Physiology Score among critically ill obstetric patients[28,29] and hence, like a recently published study,[20] we also did not use any scoring system to assess severity of illness or predict mortality. However, the present study has some other limitations. Cases identified by retrospective audit of medical records might have been skewed toward direct obstetric diagnoses due to flagged predilection, thereby missing some cases admitted with indirect obstetric problems.[27] Being a single center study, our results cannot be extrapolated to a larger and diverse base of obstetric patients. Multicentre Indian studies on obstetric critical care may be helpful. Finally, perinatal care is a holistic management which involves well-coordinated functioning of various levels of health-care delivery systems. Our study, being a snapshot of obstetric patients managed in the CCU, is not representative of overall perinatal service delivery.

CONCLUSIONS

Although obstetric patients needing critical care constitute a small fraction of pregnant patients, maternal health is a priority domain for any nation, and hence, strengthening of critical care services to save high-risk obstetric patients is of paramount importance. Adequate number of general critical care beds and dedicated obstetric HDUs are essential necessities in high volume obstetric centers. A structured general critical care training for obstetric residents, and regular interdisciplinary meetings with critical care, obstetric and other relevant specialities may raise the standards of obstetric critical care delivery.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Paruk F, Moodley J. Severe obstetric morbidity. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2001;13:563–8. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200112000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mantel GD, Buchmann E, Rees H, Pattinson RC. Severe acute maternal morbidity: A pilot study of a definition for a near-miss. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:985–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzpatrick C, Halligan A, McKenna P, Coughlan BM, Darling MR, Phelan D. Near miss maternal mortality (NMM) Ir Med J. 1992;85:37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeeman GG, Wendel GD, Jr, Cunningham FG. A blueprint for obstetric critical care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:532–6. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mjahed K, Hamoudi D, Salmi S, Barrou L. Obstetric patients in a surgical Intensive Care Unit: Prognostic factors and outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26:418–23. doi: 10.1080/01443610600720188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filippi V, Ronsmans C, Gohou V, Goufodji S, Lardi M, Sahel A, et al. Maternity wards or emergency obstetric rooms? Incidence of near-miss events in African hospitals. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:11–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouvier-Colle MH, Varnoux N, Salanave B, Ancel PY, Bréart G. Case-control study of risk factors for obstetric patients’ admission to Intensive Care Units. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;74:173–7. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(97)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert TT, Smulian JC, Martin AA, Ananth CV, Scorza W, Scardella AT. Critical Care Obstetric Team. Obstetric admissions to the Intensive Care Unit: Outcomes and severity of illness. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 Pt 1):897–903. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00767-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scarpinato L. Obstetric critical care. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:433. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199803000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison DA, Penny JA, Yentis SM, Fayek S, Brady AR. Case mix, outcome and activity for obstetric admissions to adult, general critical care units: A secondary analysis of the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. Crit Care. 2005;9:S25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sriram S, Robertson MS. Critically ill obstetric patients in Australia: A retrospective audit of 8 years’ experience in a tertiary Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Resusc. 2008;10:124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zwart JJ, Dupuis JR, Richters A, Ory F, van Roosmalen J. Obstetric Intensive Care Unit admission: A 2-year nationwide population-based cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:256–63. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1707-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leung NY, Lau AC, Chan KK, Yan WW. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of obstetric patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: A 10-year retrospective review. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Togal T, Yucel N, Gedik E, Gulhas N, Toprak HI, Ersoy MO. Obstetric admissions to the Intensive Care Unit in a tertiary referral hospital. J Crit Care. 2010;25:628–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crozier TM, Wallace EM. Obstetric admissions to an integrated general Intensive Care Unit in a quaternary maternity facility. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;51:233–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wanderer JP, Leffert LR, Mhyre JM, Kuklina EV, Callaghan WM, Bateman BT. Epidemiology of obstetric-related ICU admissions in Maryland: 1999-2008*. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1844–52. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a3e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta S, Naithani U, Doshi V, Bhargava V, Vijay BS. Obstetric critical care: A prospective analysis of clinical characteristics, predictability, and fetomaternal outcome in a new dedicated obstetric Intensive Care Unit. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:146–53. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.79895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhadade R, De’Souza R, More A, Harde M. Maternal outcomes in critically ill obstetrics patients: A unique challenge. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2012;16:8–16. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.94416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chawla S, Nakra M, Mohan S, Nambiar BC, Agarwal R, Marwaha A. Why do obstetric patients go to the ICU? A 3-year-study. Med J Armed Forces India. 2013;69:134–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2012.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramachandra Bhat PB, Navada MH, Rao SV, Nagarathna G. Evaluation of obstetric admissions to Intensive Care Unit of a tertiary referral center in coastal India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2013;17:34–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.112156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashraf N, Mishra SK, Kundra P, Veena P, Soundaraghavan S, Habeebullah S. Obstetric patients requiring intensive care: A one year retrospective study in a tertiary care institute in India. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2014;2014:789450. doi: 10.1155/2014/789450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gombar S, Ahuja V, Jafra A. A retrospective analysis of obstetric patient's outcome in Intensive Care Unit of a tertiary care center. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014;30:502–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.142843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harde M, Dave S, Wagh S, Gujjar P, Bhadade R, Bapat A. Prospective evaluation of maternal morbidity and mortality in post-cesarean section patients admitted to postanesthesia Intensive Care Unit. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014;30:508–13. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.142844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain M, Modi JN. An audit of obstetric admissions to Intensive Care Unit in a medical college hospital of central India: Lessons in preventing maternal morbidity and mortality. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2015;4:140–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pattnaik T, Samal S, Behuria S. Obstetric admissions to the Intensive Care Unit: A five year review. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2015;4:1914–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain S, Guleria K, Vaid NB, Suneja A, Ahuja S. Predictors and outcome of obstetric admissions to Intensive Care Unit: A comparative study. Indian J Public Health. 2016;60:159–63. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.184575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pollock W, Rose L, Dennis CL. Pregnant and postpartum admissions to the Intensive Care Unit: A systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1465–74. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1951-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karnad DR, Lapsia V, Krishnan A, Salvi VS. Prognostic factors in obstetric patients admitted to an Indian Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1294–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000128549.72276.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.el-Solh AA, Grant BJ. A comparison of severity of illness scoring systems for critically ill obstetric patients. Chest. 1996;110:1299–304. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.5.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]