Abstract

Objective:

This systematic review examined whether radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a safe treatment modality for benign thyroid nodules (BTNs).

Data Sources:

PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library database were searched for articles that (a) targeted human beings and (b) had a study population with BTNs that were confirmed by fine-needle aspiration cytology and/or core needle biopsy.

Study Selection:

Thirty-two studies relating to 3409 patients were included in this systematic review.

Results:

Based on literatures, no deaths were associated with the procedure, serious complications were rare, and RFA appears to be a safe and well-tolerated treatment modality. However, a broad spectrum of complications offers insights into some undesirable complications, such as track needle seeding and Horner syndrome.

Conclusions:

RFA appears to be a safe and well-tolerated treatment modality for BTNs. More research is needed to characterize the complications of RFA for thyroid nodules.

Keywords: Benign Nodules, Complications, Radiofrequency Ablation, Thyroid

Introduction

Thyroid nodules are extremely common in the general population.[1] Some patients with benign thyroid nodules (BTNs) may require treatment due to nodule-related clinical problems.[2,3,4] With respect to the common treatment methods for BTNs, surgery has some drawbacks, and levothyroxine suppressive therapy has the potential to cause harm that outweighs the benefit for most patients[2,3,5,6,7] Since the first report of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for the treatment of BTNs in 2006,[8] this minimally invasive technique has been considered to be a safe and effective alternative to surgery. Studies available in literature reported that the nodule volume reduction after RFA ranged from 47.7% to 96.9% and that the symptom grading score improvement ranged from 2.1–6.1 to 0.2–2.5 (10-cm visual analog scale).[9,10,11,12,13] Technically, an ultrasound (US)-guided RF electrode is usually inserted from the thyroid isthmus to the lateral aspect of a targeted nodule, and the heat generated from high-frequency alternating electric current leads to irreversible damage of the tumor tissue around the electrode. In contrast to the fixed electrode that is used to treat liver tumors, the moving shot technique that was proposed by Baek et al. is a core technique that was designed to optimize thyroid ablation and avoid damage to the surrounding critical structures.[14]

Nevertheless, RFA is technically challenging and requires extensive experience. It is extremely important for the operator to understand all possible complications and related preventive measures. However, a systematic record of these factors does not exist. Therefore, we aimed to collect and summarize all reported postablation adverse events. In this review, the likelihood, severity, clinical features, and prognosis of various adverse events are presented. Possible causes and measures used for prevention and treatment are discussed. This systematic review, while subject to some biases, has the advantage of representing experiences from large centers as well as individual cases from small centers, including centers in under-resourced countries.

Methods

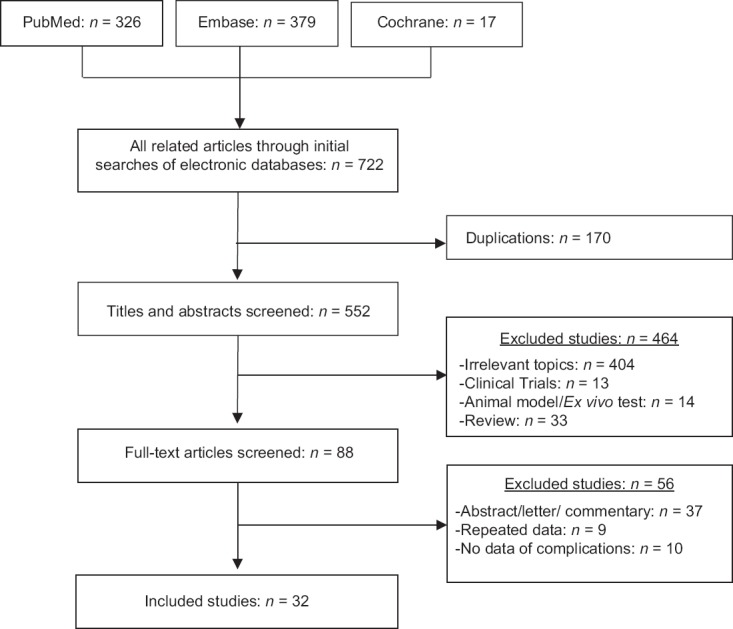

A literature search of the electronic databases of PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library was performed in December 2016, without restricting the region, publication type, or language. The following keywords were used to search for articles: radiofrequency, ablation/radio-frequency, ablation/radiofrequency, catheter ablation, and thyroid nodule/thyroid. A search for a relevant meta-analysis or systematic review in both electronic databases retrieved no results. After, we supplemented the search with manual searches of the reference lists of all retrieved studies, review articles, and conference abstracts. Upon retrieval of potentially eligible studies, the full-texts were evaluated for eligibility. Except for animal experiments and literature reviews, this article included all studies that described the complications of RFA for BTNs. Only those patients whose diagnosis was confirmed by fine-needle aspiration (FNA), cytology, and/or core needle biopsy were recruited. When multiple reports describing the same population were published, the most recent or most complete report was used. A total of 32 studies relating to 3409 patients were included in the study. The literature search and screening process for this systematic review are summarized in Figure 1 and Supplementary 1 (134.8KB, pdf) , respectively.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of studies identified, included, and excluded.

Search Strategy

All of the 32 included studies in which complications were reported are represented in Table 1. The likelihood and severity, related preventive measures, and therapy reported for each complication are presented in Table 2. A synopsis of the relevant patient preparation, procedures, and follow-up RFA is provided in Supplementary 2 (134.5KB, pdf) .

Table 1.

Studies reviewed between 2008 and 2016

| Author/year | Study design | Patients (number of BTNs) | Baseline volume (ml) | Follow-up (months) | Complications (n)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deandrea et al., 2008[10] | Prospective | 31 (33) | 27.7 | 6 | Pain (few); a sensation of heat; edema |

| Spiezia et al., 2009[15] | Retrospective | 94 (94) | 24.5 | 24 | A sensation of heat; pain (13); fever (5) |

| Baek et al., 2009[14] | Retrospective | 9 (9) | 14.98 | 6–17 | Pain and/or a sensation of heat; Subclinical hypothyroidism (1) |

| Shin et al., 2011[16] | Case report | 6 (1) | 22.53 | NA | Nodule rupture (6) |

| Kim, 2012[17] | Retrospective | 18 (18) | 4.2 | 6–12 | Pain (3); diffuse glandular hemorrhage (1) |

| Faggiano et al., 2012[18] | Prospective | 20 (20) | 13.3 | 12 | A sensation of heat; |

| Baek et al., 2012[19] | Retrospective | 1459 (1543) | NA | NA | Pain (38); hematoma (15); vomiting (9); skin burn (3); voice change (15); vasovagal reaction (5); nodule rupture (3); hypothyroidism (1); brachial plexus nerve injury (1) |

| Sung et al., 2013[20] | RCT | 25 (25) | 9.3 | 6 | Pain (21) |

| Sui et al., 2013[21] | Retrospective | 78 (108) | 1.17 | 18 | Voice change (2); pain (8) |

| Bernardi et al., 2014[22] | Retrospective | 37 (37) | 12.4 | 12 | Pain (2); late-onset, painless thyroiditis with transient thyrotoxicosis (1); voice change (1) |

| Yoon et al., 2014[23]† | Retrospective | 11 (11) | 17.1 | 11.4 (6–24) | Pain and a sensation of heat |

| Turtulici et al., 2014[24] | Retrospective | 45 (45) | 13.5 | 6 | Skin burn (1) |

| Lee et al., 2014[25] | Case report | 1 (1) | 13.6 | 48 | Needle track seeding |

| Baek et al., 2015[13] | RCT | 25 (25) | 8.6 | 6 | Pain (22) |

| Cesareo et al., 2015[26] | RCT | 42 (42) | 24.5 | 6 | Pain (9); voice change (3) |

| Valcavi et al.,2015[27] | Prospective | 40 (40) | 30 | 24 | Pain (7); bleeding (4); vasovagal reaction (1); cough (2); swelling (4); bruise (1); fever (1); nodule rupture (1); pseudocystic transformation (1) |

| Deandrea et al., 2015[28]† | RCT | 40 (40) | 13.9 versus 16.4 | 6 | A sensation of heat; pain (13); fever (5) |

| Che et al., 2015[29] | Retrospective | 200 (375) | 5.4 | 12 | Nodule rupture (1); hoarseness (1) |

| Sung et al., 2015[30] | Retrospective | 44 (44) | 18.5 | 19.9 (6–59) | Pain and/or a sensation of heat |

| Ugurlu et al., 2015[31] | Prospective | 33 (65) | 7.3 | 6 | Pain |

| Kohlhase et al., 2016[32] | Retrospective | 18 (20) | 8 | 3 | Latent hypothyroid functional state (1) |

| Korkusuz et al., 2016[33] | Prospective | 23 (24) | 18 | NA | Pain (23); hematoma (4) |

| Ahn et al., 2016[34] | Retrospective | 19 (22) | 14.3 | 3–6 | Pain and a sensation of heat |

| Aysan et al., 2016[35] | Retrospective | 100 (100) | 16.8 | 6–24 | Edema (1); hoarseness (1) |

| Li XL et al., 2016[36] | Prospective | 35 (35) | 8.81 | 6 | Pain and a sensation of heat |

| Oddo et al., 2017[37] | Case report | 1 (1) | 32.25 | 30 | Needle track seeding |

| Bernardi et al., 2016[38] | Case report | 1 (1) | 20.23 | NA | Skin burn (1) |

| Kim et al., 2016[39] | Retrospective | 746 | 18.5 | 45.7 (1–78) | Pain (5); vomiting (3); cough (8) voice change (6); edema (24); hypertension (10); muscle twitching (1); nodule rupture (3); Horner syndrome (1); hematoma (6); vasovagal reaction (6); transient hypothyroidism (1) |

| Zhao et al., 2016[40] | Retrospective | 54 (69) | 6.35 | 6 | Pain (2); hematoma (1) |

| Bernardi et al., 2016[41] | Prospective | 25 | 17.12 | 12 | Pain (1); voice change (1) |

| Yue et al., 2017[42] | Retrospective | 102 | 5.7 | 10.7 | Pain (102); hoarseness (2) |

| Zhang et al., 2016[43] | Retrospective | 27 (33) | 3.0 | 6–12 | Pain; hoarseness (1); hematoma |

*Complications of RFA were reported from different studies in detail; † Combination therapy consisting of ethanol and radiofrequency ablation. RFA: Radiofrequency ablation; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; NA: Not applicable.

Table 2.

Likelihood, severity, measures of prevention and treatment of complications of RFA for BTNs

| Complications (likelihood*, severity†) | Clinical features/prognosis | Preventive measures | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voice change/hoarseness (0.5–4.7%/2) Dysphonia (1/3) | Occurring during or immediately after ablation/recovering spontaneously within 3 months, except for two who were lost to follow-up[19,39] | Good knowledge of neck anatomy Through the “trans-isthmic” approach and the “moving- shot” technique Undertreating the part near the danger triangle US-guided monitoring of the electrode tip Communication with patients during the procedure[44] | No need treatment for most patient Steroids, if necessary (i.e., prednisone)[22] |

| Brachial plexus nerve injury (1/2) | Numbness and decreased sensation in the fourth and fifth fingers/gradual recovery[8,19] | Good knowledge of neck anatomy; enough US-guidance invention practice Monitoring the electrode tip[19] | |

| Horner syndrome (1/3) | Ocular discomfort and redness of conjunctiva, ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis of the face/improved slightly, continued to persist[39] | Careful preoperative evaluation Monitoring the active needle tips[39] | Without further treatment |

| Nodule rupture (2/2) | Abrupt neck swelling and pain at the RFA site after the procedure/the breakdown of the anterior thyroid capsule and the communication between intra- and extra-thyroidal lesions at the RF site (US or CT)/recovery well without sequelae[16] | Warning patients the symptoms about nodule rupture | Conservative therapy firstly Antibiotics and/or analgesics Incision and drainage Surgery[16] |

| Needle track seeding (1/3) | No reduction or increased volume of the thyroid nodule following RFA, a newly hypoechoic mass surrounded track of the site of RFA (US)[25,37] | Small needle size At least two separate biopsies Regular follow-up | Surgery |

| Hypothyroidism (1/2–3) | Asymptomatic[19] | Thyroid function test, giving more notice for patients with elevated serum thyroid antibodies | Levothyroxine replacement therapy |

| Transient thyrotoxicosis (1/2) | Asymptomatic/transient, recovery spontaneously | ||

| Pseudocystic transformation (colliquation) (1/1) | Pain and sudden swelling[27] | Corticosteroids (i.e., oral methylprednisolone)[27] | |

| Pain/a sensation of heat (up to 100%/1) | Mild to moderate pain and a sense of heat in the neck or at the ablated site, radiating to the head, gonial angle, ear, shoulder, jaw, or teeth/self-limited[23,31,45] | Local anesthesia[10,15,18] Reducing RF power or transient or stopping ablation during the procedure Sedatives is not recommended[44] | No treatment in most cases and Oral analgesics if necessary (i.e., acetaminophen, paracetamol)[10,17,31] |

| Hematoma (0.9–17.0%/1) | Asymptomatic in general/expanding hypo/anechoic signal surrounding the thyroid lobe or intrathyroid in US/disappearing spontaneously within 1 month[19,33,46] | Medical history about hemorrhaging risk and diseases affecting coagulation (i.e., end-aged liver and renal diseases) pre-RFA; Stop taking drugs associated with a bleeding tendency pre-RFA; Small needle size; Shift needle-electrode insertion and heat administration[27,44] | Manual compression at the site of puncture No need special treatment for most hematoma |

| Vomiting (1/1) | Occurring after ablation | Antiemetics | |

| Diffuse granular hemorrhage (1/2) | Severe pain and anterior neck swelling during the procedure/no sequelae | Oral analgesics for 3 days[17] | |

| Skin burn (1/1–2) | Skin color change, mild pain, and discomfort at the puncture site/resolution without management in five cases[8,19,38] | Trans-isthmic approach Monitoring the active needle tips Application of an ice bag | Application of an ice bag Seek help of plastic surgeon, if necessary[38] |

| Fever (0.27–6.00%/1) | Mild to moderate fever up to 38.5°C after the ablation/recovering spontaneously within 3 days | No additional therapy | |

| Edema/swelling (1/1) | Swelling with pressure symptoms due to increase in nodule and parathyroid tissue/self-limited[19,27] | Steroids (i.e., betamethasone)[10] or oral anti-inflammatory treatment if necessary[35] | |

| Cough (1/1) | Last 10–40 seconds during the procedure[19,39] | Keep appropriate distance between the electrode needle and the trachea | No additional treatment |

| Vasovagal reaction (0.34–2.50%/2) | Bradycardia, hypotension, vomiting, and defecation, sweating, difficulty breathing during the procedure>[19,39] | Pain prevention | Elevation of the patient’s legs and stopping the ablation Calming the patient down |

| Hypertension (2/2) | Increases in blood pressure during the procedure | Monitor blood pressure during the procedure[39] | |

| Muscle twitching (1/1) | Transient[39] | No additional treatment | |

| Muscle twitching (1/1) | Transient[39] | No additional treatment |

*Likelihood is presented in percentage if epidemiologic data exists in literature; if without epidemiologic data, it is presented in numerical scale as follows, 1: Extremely rare (<5 reported cases); 2: rare (≥5 or ≤10 reported cases); † Severity was assessed, 1: Negligible morbidity; 2: Moderate morbidity; 3: Severe morbidity; US: Ultrasound; BTNs: Benign thyroid nodules; RFA: Radiofrequency ablation; CT: Computed tomography.

General Conditions for Best Outcomes: a Synopsis

Results

Voice change/hoarseness

As a serious complication of RFA, voice change/hoarseness can be found during the procedure or immediately after ablation. Voice change is usually transient, and most patients recover spontaneously within 3 months without special treatments.[8,19,21,26,41,42,43,46] Prednisone may be useful for reducing the recovery period.[22] One patient experienced permanent right paramedian vocal cord palsy with inspiratory stridor but without dysphonia.[26] Another patient who complained of dysphonia postablation demonstrated ipsilateral vocal cord palsy upon laryngoscopic evaluation, and this symptom lasted for approximately 1 month. However, this patient was then lost to follow-up.[8] Despite the rarity of permanent voice changes following RFA for BTNs, a higher incidence has been reported in patients with recurrent thyroid cancers after RFA.[39]

Four patients with voice changes were diagnosed with recurrent laryngeal nerve injury by laryngoscopic evaluation.[10,12] The proposed mechanisms included RFA-induced thermal injury of the recurrent laryngeal nerve or vagus nerve, lidocaine injection leading to transient voice change, stretching of the nerve over a hematoma, posthemorrhage inflammation, and fibrosis around the nerve.[19,39]

It is crucial for surgeons to understand complicated neck anatomy and assess the location and variation of the relevant nerves (recurrent laryngeal nerve and vagus nerve) before RFA. In general, the recurrent laryngeal nerve is located in the tracheoesophageal grooves, and the vagus nerve is located between the carotid artery and internal jugular vein, but variations of the vagus nerve and a bulging large thyroid nodule may change the location of the vagus nerve, positioning it closer to the thyroid nodule.[44,48,49] To avoid nerve injury, several methods are recommended, including the “transisthmic approach method,” the “moving-shot technique,” hydrodissection between the nodule and dangerous triangle, the maintenance of a minimal distance of more than 3 mm between the RF electrode and nerves, and undertreating the ablation units adjacent to the recurrent laryngeal nerve.[29,44,47] Meanwhile, the patient should be encouraged to communicate with the surgeon intermittently throughout the procedure to assess whether any voice changes or hoarseness occur.[44]

Brachial plexus nerve injury

Although puncture of the brachial plexus nerve is an unlikely complication post-RFA given the deep location of the nerve, direct evidence for this complication was reported in one case.[8,19] The patient complained of numbness and decreased sensation in the fourth and fifth fingers of the left hand and gradually recovered over the next 2 months. Penetration of the electrode outside the thyroid gland during RFA due to visual disturbance caused by echogenic bubbles may be the cause of this complication. Thus, the entire electrode should always be visualized by real-time US images during the RFA procedure.

Horner syndrome

Horner syndrome has been reported immediately following RFA, with ocular discomfort and redness of the conjunctiva as symptoms. The patient subsequently developed clinical features of Horner syndrome, such as ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis of the face. Without further management, the patient improved slightly after 6 months, but the syndrome persisted.[39]

In the patient who developed Horner syndrome, the nodule that was treated with RFA was close to the middle cervical sympathetic ganglion (mCSG). Thermal injury or hematoma compression of the mCSG may explain this complication. The location of the mCSG is usually at the lower level of the thyroid gland and lateral to the common carotid artery, which is visible in 41% of US images.[49] However, the authors emphasized that caution should be used when differentiating between the mCSG and various surrounding structures, such as the lymph nodes, longus capitis muscle, and thyroid incidentaloma, on US examination.[50]

Nodule rupture

Although post-RFA nodule rupture is rare as a serious complication, 14 cases were reported in the included articles.[16,27,29,39] The definition of nodule rupture post-RFA of the thyroid gland is the breakdown of the thyroid capsule and a leak of the fluid from intrathyroidal lesions toward extrathyroidal lesions.

The patients usually reported sudden neck swelling and pain at the RFA site between 9 days and 5 months after RFA.[16,19,27] Sonography and/or computed tomography (CT) could help diagnose this complication, which is visualized as the breakdown of the thyroid capsule and the formation of a new mass located between intra- and extra-thyroidal lesions at the RF site.[16] The lesions ultimately disappeared in seven patients without medication or invasive procedures. Two patients were treated with antibiotics, and the lesions gradually regressed. However, three patients ultimately underwent incision and drainage due to worsening clinical signs.[16] One patient with nodule rupture who underwent unilateral lobectomy was also described. That patient presented aggravated pain with neck skin redness several days after the diagnosis of the rupture due to cellulitis of the anterior neck and abscess formation.[16]

The main proposed mechanism of nodule rupture may be delayed bleeding caused by microvessel leakage within the nodule, leading to delayed volume expansion and rupture. This mechanism was proposed because some patients demonstrated new hyperechoic or high-attenuation portions on sonography or CT, which suggested intratumoral bleeding, and semisolid bloody material without bacterial growth was aspirated. Other causes of nodule rupture may include tearing of the tumor wall and thyroid capsule at a weak point, post-RFA massage, or strong movement of the neck.[39,16]

No specific nodule characteristics were predictive of nodule rupture. However, the following risk factors have been proposed: BTNs near the anterior thyroid capsule, in which the neck space on the anterior surface of the thyroid may not be as tight as on the other sides; large and mixed component nodules consisting of highly heterogenetic tissue, which may require more RF power through the use of multiple ablations, a higher maximum RFA power, and a longer ablation time.[16]

There is no established management protocol for nodule rupture of BTNs post-RFA. Conservative treatment rather than additional invasive procedures is recommended as the first step, as the absence of bacterial growth within the lesion has been confirmed in several cases. Anti-inflammatory and analgesics drugs can be used carefully if necessary. However, invasive management, such as drainage, excision, or even surgery, should be suggested if the symptoms are aggravated, particularly if the symptoms suggest delayed abscess formation.[16]

Needle track seeding

Needle track seeding is a severe complication. However, this complication is rare after RFA of all types of organs, even after RFA and FNA of thyroid carcinoma.[51,52,53,54] Two cases of needle track seeding were described after RFA for thyroid nodules that were proven to be BTNs by FNA.[25,37]

In one patient with a thyroid nodule that was revealed to be nodular hyperplasia versus a follicular neoplasm by FNA before the procedure, multiple new masses were found in the anterior muscle and both thyroid lobes in 2 years post-second RFA. The pathological result of the RFA-treated nodule was papillary thyroid carcinoma with central lymph node metastasis after total thyroidectomy.[25] In another case with a colloid nodular hyperplasia revealed by FNA before ablation, a new extrathyroid suprafascial mass was found on US 30-month post-RFA; surgery and pathology showed a follicular carcinoma with a minority component of papillary carcinoma.[37]

Lee et al.[25] summarized three possibilities: incidental malignant potential of the BTN, transformation of new malignant cells by RFA, and sampling error of FNA. BTNs confirmed through FNA have been described in approximately 2.5% of cases with an actual risk of malignancy in surgically excised nodules.

At least two separate US-guided FNA or core needle biopsy procedures are crucial before RFA to characterize BTNs. Caution should be used with thyroid nodules with malignant US features, even if cytology yields benign results.[22,44] During follow-up, increased or stable nodule volume should be reassessed carefully to avoid unsatisfactory treatment results, and yearly follow-up is recommended for 5 years.[22,44]

Hypothyroidism

In general, RFA has a minimal influence on thyroid function. Three cases of post-RFA hypothyroidism have been described.[14,19,32] One case with transient hypothyroidism presented an increased serum thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) concentration without any symptoms immediately post-RFA and then recovered spontaneously by the 1-year follow-up visit.[39] Another patient with elevated anti-thyroglobulin antibody (TGAb) levels before ablation developed subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH 5.6 mU/ml) by the 12-month follow-up and aggravated hypothyroidism by the 15-month follow-up (TSH 36.7 mU/ml).[14] Moreover, permanent hypothyroidism was detected 6-month post-RFA, manifesting as gradual neck bulging and diffuse enlarged thyroid without nodules upon US examination, as well as a reduced serum-free thyroxine (FT4) concentration and an increased serum TSH concentration. It is interesting that the last patient also showed persistent elevation of serum anti- thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) before and after RFA.[19]

The cause of hypothyroidism after RFA of thyroid nodules is unclear, but it is worth noting that two cases of post-RFA hypothyroidism showed increased serum thyroid antibodies (anti-TPOAb and anti-TGAb) before the procedure. Patients who developed hypothyroidism after ethanol ablation and laser ablation also showed persistent elevation of serum thyroid antibodies before and after RFA.[55,56] Although some authors have suggested that the probable cause of hypothyroidism is a progression of autoimmune thyroiditis associated with preexisting thyroid antibodies,[57,58] thyroid antibodies should be monitored in all patients during follow-up to study thyroid autoimmunity after ablation techniques that expose thyroid antigens.

Although the risk of hypothyroidism is very low, it is necessary to inform patients with elevated serum thyroid antibodies before ablation about the possibility of hypothyroidism after the procedure.

Transient thyrotoxicosis

Thyrotoxicosis was indicated by a thyroid hormone increase and a TSH decrease. In all studies, one case of late-onset, painless thyroiditis with transient thyrotoxicosis occurred 3 months post-RFA.[22] The patient recovered spontaneously within 30 days without developing hypothyroidism.

As reported by Kobayashi et al.,[55] thyroiditis with thyrotoxicosis after needle aspiration of a thyroid cyst is regarded to be an inflammatory process. The procedure triggers the release of thyroid hormones. The complication may be caused post-RFA through a mechanism similar to that reported for postaspiration thyrotoxicosis. Postoperative transient abnormal thyroid function tests should be considered a normal response to the procedure.

Pseudocystic transformation (colliquation)

One case of pseudocystic transformation (colliquation) occurred 3 weeks after the RFA procedure, manifesting as pain and sudden swelling, which is similar to nodule rupture. An additional course of corticosteroids (oral methyl prednisone: 16 mg for the 1st week, 8 mg for the 2nd week, and 4 mg for the 3rd week) was administered, but the outcome of the patient was not mentioned in the article.[27]

US could be useful for diagnosing pseudocystic transformation, but we should note that the normal sonographic appearance of thyroid nodules post-PFA, such as marked hypoechogenicity, heterogeneity, and irregular margins, may be misleading.

Pain/sensation of heat

Pain, with an incidence rate ranging from 2.6% to 17.5%, is the most common complaint during the procedure and is generally accompanied by a sensation of heat.[20,23,30,31,33,34,35,45]

The general location of pain was the neck, occasionally radiating around toward the head, gonial angle, ear, shoulder, or teeth.[18,36,59] Most patients experienced sustainably mild–to-moderate pain, while a few patients suffered intense intraoperative pain (visual analog score >5 or requiring medication).[13,27] Overall, only one patient was reported to be incompletely treated due to severe chest pain in all studies.[26]

The most probable reason for pain is parenchymal edema and thyroid capsule thermal damage.[27] Other factors associated with the probability and severity of pain include monopolar RFA, location of the BTNs (especially adjacent to vulnerable vital structures), needle size, lack of expertise, and vigorous handing of the needle.

Although this complication is frequently reported during RFA, it is usually self-limited, decreasing or disappearing rapidly when the RF power output is reduced or RFA is stopped. Local anesthesia is routinely recommended for pain prevention during needle insertion and electrode positioning.[15,44,60] If the pain lasts days or cannot be tolerated, oral analgesics (acetaminophen or paracetamol) can be used to control this symptom easily for no more than 3 days.[17,19,22,31] An ice pack can be used at the puncture site to relieve local post-RFA pain and discomfort, despite the absence of direct evidence. Painkillers and sedatives for pain relief during the ablation should not be recommended because such medications affect the early detection of complications.[10]

Hemorrhage/hematoma

The reported incidence of hematoma in the included studies was relatively low. These studies reported perithyroidal, subcapsular, and intranodular hemorrhage.[12,19,27,33,40,46]

Small hemorrhages/hematomas are usually asymptomatic. Most hematomas can be detected by real-time US. Intranodular hemorrhage during needle insertion appeared as a rapidly expanding hypo/anechoic signal within the nodular tissue, resulting in gradual enlargement. Perithyroidal hemorrhage was found immediately after the procedure as a hypoechoic thin layer surrounding the thyroid lobe or intrathyroid. Extensive neck bruising may appear 5–10 days after RFA, but this symptom will disappear in approximately 3–4 weeks.[27]

For solid BTNs, the rich blood supply of the BTN contributes to the susceptibility to post-RFA hemorrhage. The intranodular arteriovenous shunts in these BTNs, which divert blood to the weakened veins under high pressure, may also be associated with hemorrhage. For cystic or complex nodules, an additional mechanism for hemorrhage soon after fluid aspiration is the sudden reduction of intranodular pressure due to fluid evacuation.[61]

Most hematomas can be prevented or controlled. Patients should be informed to stop taking drugs associated with hemorrhage risk for a period before RFA.[44] During RFA, hemorrhage is prevented by swift needle-electrode insertion and heat administration, such as avoiding large blood vessels and blocking the supplying artery. When a hematoma is found by US, mild pressure should be applied to the neck for several minutes. In most cases, this complication completely disappeared within 1 month.[19,27,62] Although no patients with hemorrhage/hematoma needed further hospital or surgical treatment in any study,[63,64] uncontrolled hemorrhage and massive hematoma can induce acute upper airway obstruction and may develop rapidly.[65,66,67] Therefore, close examination and follow-up are necessary during and after the procedure.

Vomiting/nausea

Twelve patients experienced vomiting/nausea post-RFA, but no patients complained of vomiting or nausea during ablation.[12,19] Postoperative nausea and vomiting is a common complication after thyroidectomy, which can reach 70–80% when no prophylactic antiemetic therapy is administered.[68,69,70] The most possible cause is excessive extension of the neck, which can cause an imbalance of cerebral blood flow, resulting in central nausea and vomiting.[71] Vagus nerve stimulation during the neck surgery may be responsible.[70,72] In addition, the following factors may play an important role: female gender, age, nonsmoker, and history of nausea and vomiting.[73] Treatment with antiemetics can improve this symptom within 1–2 days.[19] In addition, a supplement with sufficient energy is needed for patients with severe vomiting post-RFA.

Skin burn

Six cases of skin burn at the puncture site post-RFA were reported. Five of these cases involved first-grade skin burns, which presented with skin color changes and mild pain and discomfort. The patients recovered within 10 days without specific management.[8,19,24] However, another case of serious full-thickness burn post-RFA was caused by the use of an active needle tip in proximity to the skin.[38] The patient received topical gentamicin sulfate and hyaluronic acid on the skin burn for the 1st week, activated charcoal cloth with silver for the 2nd week, and a collagen wound dressing for another 2 weeks after surgical debridement of the wound. The skin burn recovered one month later.

Minimally invasive ablative therapy requires a good appearance; therefore, more attention should be paid to this complication. The physician must be careful when the active needle tips move close to the skin. Injecting cold water into the subcutaneous layers under the puncture site may be helpful for increasing the distance between the skin and nodule. It is also helpful to use an ice bag during the procedure to prevent skin burns.

Fever

Post-RFA fever has not been adequately studied, and only a few cases have been reported.[15,19,27,28] Post-RFA acute reaction of the ablation zone may play a role in the pathogenesis of this complication. Mild–to-moderate fevers of up to 38.0°C or 38.5°C were recorded. The fever regressed spontaneously within 3 days post-RFA and did not require any additional therapy.

Edema/swelling

There is inconsistency in the reported incidence of swelling during or after RFA in different studies due to the use of different definitions.[10,19,27,35,39]

Some authors have suggested that a minimal amount of acute transient swelling of the thyroid nodules and the surrounding thyroid parenchyma immediately after RFA, with no symptoms and no additional treatment, are inevitable. Those authors considered such swelling to be neither a complication nor a side effect.[39] However, swelling with pressure symptoms but without airway obstruction due to an increase in nodule volume and the surrounding thyroid parenchyma was also reported in seven patients.[10,27] Three of these seven patients required a single administration of 1.5 mg of betamethasone to control edema, and the remaining cases resolved spontaneously within 1–7 days.[10,27]

Beyond edema of the thyroid nodule, one case of painful swelling of the skin tissue was reported postablation. This complication disappeared completely in 12 days with oral anti-inflammatory treatment.[35]

Acute swelling may sound frightening, but because this symptom is self-limiting and transient, awareness helps avoid unnecessary interventions.

Diffuse glandular hemorrhage

Only one case of diffuse glandular hemorrhage during RFA of a solid BTN was reported, with the symptoms of severe pain and anterior neck swelling, leading to discontinuation of the procedure.[17] This patient took oral analgesics for 3 days, and the diffuse glandular hemorrhage disappeared on follow-up US at 1-month post-RFA. The author made no comment about the pathogenesis of this case.

Cough

Due to its anatomic location, injury of the trachea could be a complication post-RFA, but no relevant reports were found. Only a few cases with cough have been reported.[19,27,39] Coughing is induced by the movement of the electrode needle close to the trachea and can be managed by pulling back and stopping the RFA procedure. Coughing usually lasted 10–40 s, without any symptoms associated with heat injury to the trachea detected during follow-up.

Vasovagal reaction

Vasovagal reactions occurred with bradycardia, hypotension, vomiting, difficulty breathing, and defecation. Nineteen cases have been reported.[19,27,39] These reactions may be caused by vagus nerve stimulation if the nodule is adjacent to the common carotid and the internal jugular vein. The symptoms usually last a few minutes, but they may make patients nervous. Calming the patient down, elevating the patient's legs, and stopping the ablation until spontaneous recovery is achieved are advised. This type of management will not influence the subsequent RFA.[27]

Hypertension

Increases in blood pressure were detected during the procedure in twelve patients. Four patients were treated with medication due to large blood pressure increases (more than 40 mmHg), while the remaining eight patients were observed and treated without medication.[39] Although all patients who received medication for hypertension during RFA had underlying hypertension, possible causes of blood pressure elevation are pain or the release of thyroid hormone during the ablation. Thus, to rapidly identify abnormal changes, it is important to monitor the patient's blood pressure during the ablation.

Muscle twitching

Only one patient suffered from transient muscle twitching during the ablation procedure, which was presumably caused by lidocaine toxicity.[39] The permitted maximal dose of lidocaine is 4.5 mg/kg, up to a total of 300 mg (15 ml). The symptoms of lidocaine toxicity include mental changes, muscle twitching, tremors, and seizures.[74] Thus, the surgical team should prevent lidocaine overdose and consider the possibility of lidocaine toxicity.

Discussion

There are four limitations to this study that are worth addressing. First, the criteria used to define complications and the time sequences were different as the patients came from different centers with their own criteria. Only one retrospective study defined these terms according to the standardized terminology for image-guided tumor ablation from the Society of Interventional Radiology.[39] Second, post-RFA thyroid complications are rarely recorded systematically. Even in large thyroid RFA series, complications were either not reported or were mentioned to be limited. Such results could reflect the inconsistent definitions of complications, and teams who perform RFA with undesirable consequences may be unwilling to publish their results. Moreover, case reports or case series of minor or previously reported complications are not typically accepted by journals. Third, the absence of randomized controlled trials and the availability of only two retrospective studies designed to record thyroid RFA complications as the primary aim prevented a meta-analysis from being performed. Moreover, a majority of the articles had an observational design, which precluded the ability to comment on the precise risks and causes of complications.

Although the conclusions of this review cannot serve as conclusive answers, we believe that this review of the available data could contribute to the knowledge of all reported complications of RFA, even rare or challenging complications, such as needle track seeding.

Conclusions

As a minimally invasive treatment modality for BTNs, RFA is safe and extremely well tolerated. None of the reported patients experienced any life-threatening complications related to RFA, and the rate of serious complications was low. However, this broad spectrum of complications offers insights into the essential nature of neck anatomy, physicians’ experiences with US-guided interventional procedures, preprocedural evaluations, and preventive measures.

Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Chinese Medical Journal website.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was funded by grant Sun Yat-Sen University Clinical Research 5010 Program (No. 2016016).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Li-Min Chen

References

- 1.Sharen G, Zhang B, Zhao R, Sun J, Gai X, Lou H. Retrospective epidemiological study of thyroid nodules by ultrasound in asymptomatic subjects. Chin Med J. 2014;127:1661–5. doi: 10.3760cma.j.issn.0366-6999.20132469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gharib H, Papini E, Garber JR, Duick DS, Harrell RM, Hegedüs L, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Associazione Medicai Endocrinologi Medical Guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules-2016 update. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:622–39. doi: 10.4158/EP161208.GL. doi: 10.4158/ep161208.gl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: The American Thyroid Association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26:1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huan Q, Wang K, Lou F, Zhang L, Huang Q, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of thyroid nodules and risk factors for malignant nodules: A retrospective study from 6,304 surgical cases. Chin Med J. 2014;127:2286–92. doi: 10.3760cma.j.issn.0366-6999.20132469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gharib H. Changing trends in thyroid practice: Understanding nodular thyroid disease. Endocr Pract. 2004;10:31–9. doi: 10.4158/EP.10.1.31. doi: 10.4158/ep.10.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeannon JP, Orabi AA, Bruch GA, Abdalsalam HA, Simo R. Diagnosis of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after thyroidectomy: A systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:624–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01875.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linos D, Economopoulos KP, Kiriakopoulos A, Linos E, Petralias A. Scar perceptions after thyroid and parathyroid surgery: Comparison of minimal and conventional approaches. Surgery. 2013;153:400–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.08.008. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim YS, Rhim H, Tae K, Park DW, Kim ST. Radiofrequency ablation of benign cold thyroid nodules: Initial clinical experience. Thyroid. 2006;16:361–7. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.361. doi: 16:361-7.10.1089/thy.2006.16.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH, Kim YS, Lee D, Choi H, Yoo H, Baek JH. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of benign thyroid nodules in patients with incompletely resolved clinical problems after ethanol ablation (EA) World J Surg. 2010;34:1488–93. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0565-6. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0565-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deandrea M, Limone P, Basso E, Mormile A, Ragazzoni F, Gamarra E, et al. US-guided percutaneous radiofrequency thermal ablation for the treatment of solid benign hyperfunctioning or compressive thyroid nodules. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:784–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.10.018. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung JY, Kim YS, Choi H, Lee JH, Baek JH. Optimum first-line treatment technique for benign cystic thyroid nodules: Ethanol ablation or radiofrequency ablation? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W210–4. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5172. doi: 10.2214/ajr.10.5172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim HK, Lee JH, Ha EJ, Sung JY, Kim JK, Baek JH. Radiofrequency ablation of benign non-functioning thyroid nodules: 4-year follow-up results for 111 patients. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:1044–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2671-3. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2671-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baek JH, Ha EJ, Choi YJ, Sung JY, Kim JK, Shong YK. Radiofrequency versus ethanol ablation for treating predominantly cystic thyroid nodules: A randomized clinical trial. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16:1332–40. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.6.1332. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.6.1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baek JH, Moon WJ, Kim YS, Lee JH, Lee D. Radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of autonomously functioning thyroid nodules. World J Surg. 2009;33:1971–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0130-3. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spiezia S, Garberoglio R, Milone F, Ramundo V, Caiazzo C, Assanti AP, et al. Thyroid nodules and related symptoms are stably controlled two years after radiofrequency thermal ablation. Thyroid. 2009;19:219–25. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0202. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin JH, Jung SL, Baek JH, Kim JH. Rupture of benign thyroid tumors after radio-frequency ablation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:2165–9. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2661. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim DW. Sonography-guided ethanol ablation of a remnant solid component after radio-frequency ablation of benign solid thyroid nodules: A preliminary study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:1139–43. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2904. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faggiano A, Ramundo V, Assanti AP, Fonderico F, Macchia PE, Misso C, et al. Thyroid nodules treated with percutaneous radiofrequency thermal ablation: A comparative study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:4439–45. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2251. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baek JH, Lee JH, Sung JY, Bae JI, Kim KT, Sim J, et al. Complications encountered in the treatment of benign thyroid nodules with US-guided radiofrequency ablation: A multicenter study. Radiology. 2012;262:335–42. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110416. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sung JY, Baek JH, Kim KS, Lee D, Yoo H, Kim JK, et al. Single-session treatment of benign cystic thyroid nodules with ethanol versus radiofrequency ablation: A prospective randomized study. Radiology. 2013;269:293–300. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122134. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sui Y, Wu FL, Hu J, Liu LY. Method and short term efficacy of ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation of thyroid benign nodules. Chin J Med Imaging Technol. 2013;29:706–9. doi: 10.13929/j.1003-3289.2013.05.027. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernardi S, Dobrinja C, Fabris B, Bazzocchi G, Sabato N, Ulcigrai V, et al. Radiofrequency ablation compared to surgery for the treatment of benign thyroid nodules. Int J Endocrinol 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/934595. 934595. doi: 10.1155/2014/934595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon HM, Baek JH, Lee JH, Ha EJ, Kim JK, Yoon JH, et al. Combination therapy consisting of ethanol and radiofrequency ablation for predominantly cystic thyroid nodules. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:582–6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3701. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turtulici G, Orlandi D, Corazza A, Sartoris R, Derchi LE, Silvestri E, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of benign thyroid nodules assisted by a virtual needle tracking system. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2014;40:1447–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.02.017. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee CU, Kim SJ, Sung JY, Park SH, Chong S, Baek JH. Needle track tumor seeding after radiofrequency ablation of a thyroid tumor. Jpn J Radiol. 2014;32:661–3. doi: 10.1007/s11604-014-0350-9. doi: 10.1007/s11604-014-0350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cesareo R, Pasqualini V, Simeoni C, Sacchi M, Saralli E, Campagna G, et al. Prospective study of effectiveness of ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation versus control group in patients affected by benign thyroid nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:460–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2186. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valcavi R, Tsamatropoulos P. Health-related quality of life after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of cold, solid, benign thyroid nodules: A 2-year follow-up study in 40 patients. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:887–96. doi: 10.4158/EP15676.OR. doi: 10.4158/ep15676.or. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deandrea M, Sung JY, Limone P, Mormile A, Garino F, Ragazzoni F, et al. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency ablation versus observation for nonfunctioning benign thyroid nodules: A randomized controlled international collaborative trial. Thyroid. 2015;25:890–6. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Che Y, Jin S, Shi C, Wang L, Zhang X, Li Y, et al. Treatment of benign thyroid nodules: Comparison of surgery with radiofrequency ablation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:1321–5. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4276. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sung JY, Baek JH, Jung SL, Kim JH, Kim KS, Lee D, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for autonomously functioning thyroid nodules: A multicenter study. Thyroid. 2015;25:112–7. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0100. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ugurlu MU, Uprak K, Akpinar IN, Attaallah W, Yegen C, Gulluoglu BM. Radiofrequency ablation of benign symptomatic thyroid nodules: Prospective safety and efficacy study. World J Surg. 2015;39:961–8. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2896-1. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2896-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kohlhase KD, Korkusuz Y, Gröner D, Erbelding C, Happel C, Luboldt W, et al. Bipolar radiofrequency ablation of benign thyroid nodules using a multiple overlapping shot technique in a 3-month follow-up. Int J Hyperthermia. 2016;32:511–6. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2016.1149234. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2016.1149234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korkusuz Y, Erbelding C, Kohlhase K, Luboldt W, Happel C, Grünwald F. Bipolar radiofrequency ablation of benign symptomatic thyroid nodules: Initial experience. Rofo. 2016;188:671–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-110137. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-110137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahn HS, Kim SJ, Park SH, Seo M. Radiofrequency ablation of benign thyroid nodules: Evaluation of the treatment efficacy using ultrasonography. Ultrasonography. 2016;35:244–52. doi: 10.14366/usg.15083. doi: 10.14366/usg.15083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aysan E, Idiz UO, Akbulut H, Elmas L. Single-session radiofrequency ablation on benign thyroid nodules: A prospective single center study: Radiofrequency ablation on thyroid. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2016;401:357–63. doi: 10.1007/s00423-016-1408-1. doi: 10.1007/s00423-016-1408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li XL, Xu HX, Lu F, Yue WW, Sun LP, Bo XW, et al. Treatment efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided percutaneous bipolar radiofrequency ablation for benign thyroid nodules. Br J Radiol. 2016;89:20150858. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150858. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oddo S, Spina B, Vellone VG, Giusti M. A case of thyroid cancer on the track of the radiofrequency electrode 30 months after percutaneous ablation. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40:101–2. doi: 10.1007/s40618-016-0527-4. doi: 10.1007/s40618-016-0527-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernardi S, Lanzilotti V, Papa G, Panizzo N, Dobrinja C, Fabris B, et al. Full-thickness skin burn caused by radiofrequency ablation of a benign thyroid nodule. Thyroid. 2016;26:183–4. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0453. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim C, Lee JH, Choi YJ, Kim WB, Sung TY, Baek JH, et al. Complications encountered in ultrasonography-guided radiofrequency ablation of benign thyroid nodules and recurrent thyroid cancers. Eur Radiol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4690-y. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4690-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao CK, Xu HX, Lu F, Sun LP, He YP, Guo LH, et al. Factors associated with initial incomplete ablation for benign thyroid nodules after radiofrequency ablation: First results of CEUS evaluation. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2017;65:393–405. doi: 10.3233/CH-16208. doi: 10.3233/ch-16208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernardi S, Stacul F, Michelli A, Giudici F, Zuolo G, de Manzini N, et al. 12-month efficacy of a single radiofrequency ablation on autonomously functioning thyroid nodules. Endocrine. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1174-4. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yue WW, Wang SR, Lu F, Sun LP, Guo LH, Zhang YL, et al. Radiofrequency ablation vs. microwave ablation for patients with benign thyroid nodules: A propensity score matching study. Endocrine. 2017;55:485–95. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1173-5. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Zhang MW, Fan XX. Ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of benign thyroid nodules: Preliminary results in 27 cases (in Chinese) J Intervent Radiol. 2016;25:136–40. doi: 10.3969j.issn.1008-794X.2016.02.011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Na DG, Lee JH, Jung SL, Kim JH, Sung JY, Shin JH, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of benign thyroid nodules and recurrent thyroid cancers: Consensus statement and recommendations. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13:117–25. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2012.13.2.117. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2012.13.2.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spiezia S, Garberoglio R, Di Somma C, Deandrea M, Basso E, Limone PP, et al. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency thermal ablation in the treatment of thyroid nodules with pressure symptoms in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1478–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01306.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jeong WK, Baek JH, Rhim H, Kim YS, Kwak MS, Jeong HJ, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of benign thyroid nodules: Safety and imaging follow-up in 236 patients. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:1244–50. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0880-6. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0880-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ha EJ, Baek JH, Lee JH. Moving-shot versus fixed electrode techniques for radiofrequency ablation: Comparison in an ex-vivo bovine liver tissue model. Korean J Radiol. 2014;15:836–43. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2014.15.6.836. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2014.15.6.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ha EJ, Baek JH, Lee JH, Kim JK, Shong YK. Clinical significance of vagus nerve variation in radiofrequency ablation of thyroid nodules. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:2151–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2167-6. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ha EJ, Baek JH, Lee JH. Ultrasonography-based thyroidal and perithyroidal anatomy and its clinical significance. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16:749–66. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.4.749. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shin JE, Baek JH, Ha EJ, Choi YJ, Choi WJ, Lee JH. Ultrasound features of middle cervical sympathetic ganglion. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:909–13. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000184. doi: 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Howenstein MJ, Sato KT. Complications of radiofrequency ablation of hepatic, pulmonary, and renal neoplasms. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2010;27:285–95. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1261787. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1261787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ito Y, Tomoda C, Uruno T, Takamura Y, Miya A, Kobayashi K, et al. Needle tract implantation of papillary thyroid carcinoma after fine-needle aspiration biopsy. World J Surg. 2005;29:1544–9. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0086-x. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Polyzos SA, Anastasilakis AD. A systematic review of cases reporting needle tract seeding following thyroid fine needle biopsy. World J Surg. 2010;34:844–51. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0362-2. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suh CH, Baek JH, Choi YJ, Lee JH. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency and ethanol ablation for treating locally recurrent thyroid cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2016;26:420–8. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0545. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kobayashi A, Kuma K, Matsuzuka F, Hirai K, Fukata S, Sugawara M. Thyrotoxicosis after needle aspiration of thyroid cyst. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:21–4. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.1.1619011. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.1.1619011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ha EJ, Baek JH, Lee JH, Sung JY, Lee D, Kim JK, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of benign thyroid nodules does not affect thyroid function in patients with previous lobectomy. Thyroid. 2013;23:289–93. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0171. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brkljacic B, Sucic M, Bozikov V, Hauser M, Hebrang A. Treatment of autonomous and toxic thyroid adenomas by percutaneous ultrasound-guided ethanol injection. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:477–81. doi: 10.1080/028418501127347205. doi: 10.1034j.1600-0455.2001.420508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shin JH, Baek JH, Ha EJ, Lee JH. Radiofrequency ablation of thyroid nodules: Basic principles and clinical application. Int J Endocrinol 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/919650. 919650. doi: 10.1155/2012/919650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garberoglio R, Aliberti C, Appetecchia M, Attard M, Boccuzzi G, Boraso F, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for thyroid nodules: Which indications?. The first Italian opinion statement. J Ultrasound. 2015;18:423–30. doi: 10.1007/s40477-015-0169-y. doi: 10.1007/s40477-015-0169-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baek JH, Jeong HJ, Kim YS, Kwak MS, Lee D. Radiofrequency ablation for an autonomously functioning thyroid nodule. Thyroid. 2008;18:675–6. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0274. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller JM, Zafar SU, Karo JJ. The cystic thyroid nodule. Recognition and management. Radiology. 1974;110:257–61. doi: 10.1148/110.2.257. doi: 10.1148/110.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jang SW, Baek JH, Kim JK, Sung JY, Choi H, Lim HK, et al. How to manage the patients with unsatisfactory results after ethanol ablation for thyroid nodules: Role of radiofrequency ablation. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:905–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.02.039. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baek JH, Lee JH, Valcavi R, Pacella CM, Rhim H, Na DG. Thermal ablation for benign thyroid nodules: Radiofrequency and laser. Korean J Radiol. 2011;12:525–40. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2011.12.5.525. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2011.12.5.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen F, Tian G, Kong D, Zhong L, Jiang T. Radiofrequency ablation for treatment of benign thyroid nodules: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4659. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004659. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ranta A, Salmi J, Sand J. Fatal cervical edema following diagnostic fine needle aspiration. Duodecim. 1996;112:2024–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roh JL. Intrathyroid hemorrhage and acute upper airway obstruction after fine needle aspiration of the thyroid gland. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:154–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000187396.18016.d0. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000187396.18016.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hor T, Lahiri SW. Bilateral thyroid hematomas after fine-needle aspiration causing acute airway obstruction. Thyroid. 2008;18:567–9. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0363. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Apfel CC, Läärä E, Koivuranta M, Greim CA, Roewer N. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: Conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:693–700. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199909000-00022. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fujii Y, Saitoh Y, Tanaka H, Toyooka H. Prophylactic antiemetic therapy with granisetron in women undergoing thyroidectomy. Br J Anaesth. 1998;81:526–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/81.4.526. doi: 10.1093/bja/81.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sonner JM, Hynson JM, Clark O, Katz JA. Nausea and vomiting following thyroid and parathyroid surgery. J Clin Anesth. 1997;9:398–402. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(97)00069-x. doi: 10.1016/S0952-8180(97)00069-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tominaga K, Nakahara T. The twenty-degree reverse-Trendelenburg position decreases the incidence and severity of postoperative nausea and vomiting after thyroid surgery. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:1260–3. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000240872.08802.f0. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000240872.08802.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Friedrich C, Ulmer C, Rieber F, Kern E, Kohler A, Schymik K, et al. Safety analysis of vagal nerve stimulation for continuous nerve monitoring during thyroid surgery. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1979–87. doi: 10.1002/lary.23411. doi: 10.1002/lary.23411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Apfel CC, Roewer N, Korttila K. How to study postoperative nausea and vomiting. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:921–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460801.x. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pelter MA, Vollmer TA, Blum RL. Seizure-like reaction associated with subcutaneous lidocaine injection. Clin Pharm. 1989;8:767–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search Strategy

General Conditions for Best Outcomes: a Synopsis