Cancer is diagnosed at a higher rate (53%) and results in more deaths (68%) among individuals ≥ 65 years of age than among younger adults.1,2 The burden of cancer in our population is increasing along with the need for specialized programs to address the needs of those patients. Newer targeted drugs, improved supportive care, and less invasive surgical techniques have enabled the possibility of cancer treatments even to the most elderly. However, in this patient population, cancer is often only one of multiple coexisting health conditions.3 Age-related physiological changes and disease-related effects on organ function affect drug handling and response.4 Functional, cognitive, emotional, and financial issues add to the complexity of care. Quality of life plays a critical role in the determination of the treatments patients are willing to accept, and evidence suggests that the majority of ill older adults values the maintainence of function more than the prolongation of life.5 The natural history of the particular cancer has to be weighed against the remaining life expectancy of an individual to determine the benefits and risks of cancer treatment.6,7

Elderly frail patients suffer substantial loss of reserve that may become noticeable in response to physiologic or psychological stressors, such as cancer.8,9 Their vulnerabilities are not always apparent, and a thorough evaluation is needed to identify those at risk for increased treatment-related complications. The Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is a multiple-domain evaluation of comorbid medical conditions, medications, functional status, cognition, social support, and psychological and nutritional states. It predicts cancer treatment–related toxicity and influences cancer treatment decisions.10-12 Ideally, all older patients with cancer should undergo geriatric assessment before cancer treatment.10 Unfortunately, the increased number of these patients, the shortage of geriatricians, and the length of a multidisciplinary evaluation have made CGA impractical for the practicing oncologist. In response, screening tools that could determine who needs CGA have been published, but none has been shown to have adequate sensitivity and specificity.13 The need for collaboration between geriatrics and oncology has been recognized, but a uniform model to achieve it has not been established.14-16

This article describes the model of care for older adults with cancer that was developed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC); shares the lessons learned since its inception; and, more important, identifies barriers and tactics that were successful to overcome these barriers during its development.

DEVELOPMENT OF A GERIATRIC ONCOLOGY PROGRAM

MSKCC is an urban, academic, geographically extended institution based in Manhattan with several network sites. During the 1990s, MSKCC was involved in efforts led by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Aging, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology to develop programs at the interface of geriatrics and oncology. From that time until today, the development of services for the older patient with cancer has been addressed at different levels and has led to the current comprehensive program. Several questions had to be addressed before efforts and resources were allocated for this goal.

Should We Develop a Geriatric Oncology Program?

This simple question should be the first one asked by any organization that is considering a geriatric oncology program. If there is not a leadership consensus on this point, then an effort cannot be successful. At the turn of the 21st century, there was no overarching institutional approach to the care of the older patient with cancer. Because of the prevalence of cancer in the older patient, the growing population at risk, increasing recognition of the special management issues associated with its care, and the emerging literature on the importance of geriatrics in oncology, MSKCC recognized the need for a clinical program that included geriatrics as a clinical and research discipline. It was no longer acceptable not to have geriatric expertise involved in the care of the population of older patients with cancer.

How Large Is the Need for a Geriatric Oncology Program at MSKCC?

In 2003, patients age 65 years or older accounted for 38% of all visits and for 31% of new visits. Older patients remained at MSKCC— both at the Manhattan campus and at its regional sites—for evaluation (20%) and treatment (32%) at rates similar to those of patients younger than 65 years, and treatment modality did not vary with age. Over time, the increasing age of the MSKCC patient population has mirrored that of the US general cancer population. By 2015, of the total newly registered older patients, 56% came for consultation and/or second opinion, whereas 44% of the patients received treatment. It became clear that there was a growing need for the discipline of geriatrics in the institution.

What Research Was Ongoing, and How Could People With Expertise and Similar Interests in the Care of Older Adults Be Brought Together?

In 2003, MSKCC was awarded a P20 planning grant, which provided the seed funds for programmatic research. At the same time, the Department of Medicine (DOM) launched the 65+ team, an interprofessional initiative that encompassed experts from medical oncology, surgery, rehabilitation, psychiatry, social work, pharmacy, nutrition, nursing, palliative care, and integrative medicine. The 65+ team has been meeting monthly since 2003.17It has provided a forum for the discussion of new ideas and the development of educational programs, quality initiatives, and research projects specific for this population. Members of the MSKCC 65+ team have been instrumental in the development of the field of geriatric oncology18-21 and the promotion of collaborations across the institution.

What Model of Clinical Care Should Be Implemented?

It became clear that the 65+ team was dependent on the support of the various departments and had no authority to implement change. Once again, several questions needed to be answered: (1) How can the lack of geriatrics-trained oncologists be overcome? (2) How can this be done at an institution in which cancer care is so specialized? The appointment of dually trained geriatric oncologists (even if an adequate number existed) who work in a disease-specific service cannot be an institution-wide solution. (3) Is the center prepared to underwrite such services given that they would probably be not profitable? (4) What are the benefits of support of such services?

Development of a Geriatrics Service

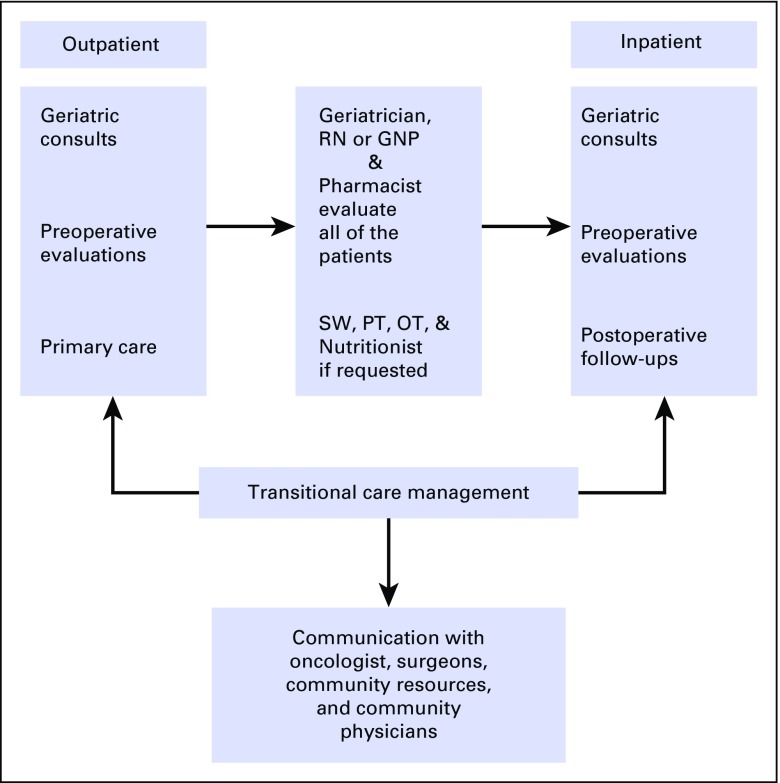

After strategic discussions of questions 1 through 4, the DOM proposed, and MSKCC accepted, the establishment of an independent geriatrics service (GS) dedicated to the medical needs of patients with cancer who suffered from geriatric syndromes. The model adopted by MSKCC (Fig 1) is based on the following: the large population of patients evaluated and treated; the subspecialization of the oncologists in a specific type of cancer, and the limited availability of clinicians (dually certified geriatric oncologists, board-certified geriatricians) who have expertise in the care of the complex problems faced by older patients with cancer. Models that have been successful in smaller institutions, like the primary provider model14 in which the older patients are evaluated and treated by a dually trained geriatric oncologist, have tight limits in the number of patients that can be seen. In centers such as MSKCC, which has greater than 3,000 new registrations of patients older than age 65 years annually (in its Manhattan location only), this model would limit the expertise to an extremely small percentage of patients.

FIG 1.

MSKCC Geriatric service: clinical activities. GNP, geriatric nurse practitioner; OT, occupational therapist; PT, physical therapist; RN, registered nurse; SW, social worker.

A GS within the DOM was established in April 2009. Geriatricians and oncologists work as partners who share the care of those patients who require dual care. The shared care allows a larger number of patients to undergo geriatric assessment. The GS is mostly a consulting service that provides comprehensive evaluation, management recommendations, and shared care for older patients with cancer. It conducts CGA while a patient’s treatment is being developed; it works closely with the primary oncologist to optimize the medical, nutritional, and functional statuses of the patient before and during cancer therapy; and it seeks to maintain the function of the patient. The main barrier to the development of such a service was the identification of geriatricians whose visions met the institutional needs and their professional goals.

A multidisciplinary approach is the basis for any comprehensive geriatric care, and this is true more so for older patients with cancer. At MSKCC, the core GS group is small, but its skills are leveraged to a much larger population of providers who identify themselves as champions for the care of the elderly and who transmit their skills to a broad range of nongeriatric physician and nonphysician providers.

Benefits for the institution are at the back end, not at the front end, of billing and collection. They include the following:

Better patient care, with screening for geriatric syndromes before cancer treatment and referral to appropriate services, that results in fewer complications because of increased awareness and early management

Shared care between medical and surgical oncology that would decrease the burden on the oncologist for care of multiple chronic comorbid conditions and geriatric syndromes

Decreased length of hospital stay, because geriatric syndromes would be addressed before treatment or early in a hospitalization

Improved transitions of care, which, in turn, could decrease rehospitalization, decrease the percentage of patients discharged to rehabilitation institutions, and improve quality of life

Development of institution-wide initiatives specific to the older population (eg, falls prevention, delirium prevention, and diagnosis guidelines and a physical therapy early-mobilization program)

Educational activities: the geriatrization of the community of MSKCC medical and nonmedical staff to leverage the skills of the GS for the benefit of a larger number of patients than could be treated by the GS members alone

Research activities, including obtainment of funding and promotion of collaborations inside and outside the institution

BARRIERS TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GERIATRIC SERVICE

The development of the GS encountered and continues to encounter multiple challenges. These include the following:

Recognition of need by colleagues: CGA has been slowly embraced by the oncology community, even though national and international societies have recommended that older patients with cancer undergo geriatric assessment.6,10,22 To improve acceptability, more and better evidence about the efficacy and toxicity of commonly used cancer therapies in the older patient, a better definition of who is fit for therapy, and improved integration of comorbidities and functional status into treatment decision making are necessary.23

Recruitment of additional faculty: The model adopted by MSKCC was based in part on the limited availability of clinicians (geriatric oncologists, geriatricians) who had expertise in the care of the complex problems faced by older patients with cancer. The recruitment and training of geriatricians is a nationwide challenge.24 The GS addressed this barrier by hiring geriatric nurse practitioners to participate in the clinical work and provide independent care under the supervision of the attending geriatricians. In addition, because the volume of older patients treated at MSKCC is significant, referrals are mostly limited to those ≥ 75 years of age, unless special circumstances are identified.

Identification of clear guidelines for consultation: Literature suggests that geriatric expertise should be considered for the patients who benefit most: any patient ≥ 85 years of age, or those younger than age 85 years who have a complex multimorbidity, frailty, or other geriatric conditions; disability; or dementia.25,26 In addition, to prevent functional decline and improve the care of older patients with geriatric syndromes, a proactive consultation service was implemented with follow-up of frail elderly patients postoperatively or during chemotherapy. The geriatrician and geriatric nurse practitioner address the patient holistically and emphasize early attention to discharge planning. When no primary care physician is identified, the GS provides assistance with postdischarge follow-up and continuity of care and attempts to arrange nononcologic care closer to home.

Alignment with the needs of the oncologists who lead the patient care team: It was recognized that the GS in the oncology environment cannot become the provider of primary care for a large number of older patients with cancer without jeopardizing the goals of the service as a consultant. The shortage of primary care physicians that accept Medicare is growing; MSKCC has no restriction for traditional Medicare. In addition, the fatigue and frailty of these older adults and the need to centralize care and avoid long, frequent commutes contributed to an increasing demand for primary geriatric care from our team. This challenge has been addressed by limiting longitudinal care only to those elderly who undergo active therapy.

Development of older patient–centered standards of care within the institution: The absence of benchmarks or standards of care specific to the older patient with cancer is an ongoing challenge. The availability of clearly defined outcomes that justify care delivery change is only slowly developing in the geriatric oncology literature. Nonetheless, several programs were successfully developed thanks to the participation of several disciplines, and they were based on the general geriatrics literature. Some of these standards include comprehensive medication review of all new consults, education about delirium and preventive measures to all patients/caregivers who screen positive for cognitive dysfunction,and a postsurgical early mobilization program for older adults.

Leverage of geriatrics in an oncology practice: As stated earlier, the skills of the GS are leveraged to a much larger population of providers by relying on the availability of allied health professionals who identified themselves as champions for the care of the elderly and transmitted their skills to a broad range of physician and nonphysician providers. The monthly 65+ team meetings serve as the foundation upon which these different professionals share their interests and learn from each other.

Management of outpatient space constraints: The challenge of outpatient space constraints is a concern of all services at MSKCC (and probably at all cancer centers and practices). Dedicated space was provided to the GS at one of the outpatient facilities of the center, but space for an interprofessional team is still needed. Patients are referred to separate practices, which is often a hardship for patients and caregivers. This difficulty has been partially overcome by provision of more phone consultations by several allied professionals (eg, pharmacy, nutrition, social work).

Evaluation of all patients by using CGA, in a timely fashion, despite lack of space and limited staff: Our approach to increasing the rate of performance of CGA in geriatric practices has been to develop an electronic assessment that is feasible, effective, and not burdensome for the provider. It can be completed online with an electronic tablet, either at home or in the waiting room, and the results are automatically collated and reported to the treating clinician.27 Patients expressed high levels of satisfaction with this instrument. The majority of patients, regardless of their age, have been able to complete it on their own or with assistance from their caregivers.

Development of research projects that would evaluate the influence of geriatric interventions in oncologic treatment outcomes: The absence of published research studies on the efficacy of geriatric interventions has been a significant limitation. Prospective and randomized trials are difficult to develop. Nonetheless, important outcomes, such as patient satisfaction, the oncologist experience with the collaboration, the impact of the GS on hospital readmissions or length of stay, and risk stratification for cancer treatment, are being studied currently at MSKCC and hold much promise for the improvement of care.

Provision of geriatric care to the entire population of older patients with cancer at MSKCC, including those cared for at our network sites: At its establishment, the GS was not able to provide services at MSKCC satellites, where a significant number of older patients are treated. This challenge is being addressed slowly. Multiple collaborations between MSKCC and local primary care provider groups are being developed, and remote access opportunities are being tested.

GENERALIZATION TO OTHER PRACTICES

Oncologists in all practice settings, big or small, urban or rural, encounter the same difficulties in the care of older adults with cancer. The presence of geriatric syndromes, which include multiple comorbidities, cognitive impairment, functional dependency, polypharmacy, and lack of social support, complicates cancer treatment. Patients with and survivors of cancer are frequently older than 65 years, and every oncologist will have a growing number of frail elderly who have complex needs in his or her practice. It is no longer reasonable to ignore the fact that this is a special group that requires specific interventions. Treatment decisions cannot be simply disease centered but must include age-related physiologic changes; disease-related changes in organ function; functional, cognitive, and/or emotional issues; and quality of life and patient preferences.

The model that we developed has the potential for generalization to other settings. One or more of our interventions28 can be applied by practicing oncologists according to the size of the practice. The interventions we use can be adapted in the context of each practice and its available resources. The need to identify and address geriatric syndromes before the development of a treatment plan is essential. It is possible to use a brief screening tool that will determine the need for CGA,29 incorporate one or two short instruments of the CGA (such as watching the patient walk 10 feet, the so-called timed get up and go30, or asking about the self-care ability of the patient) into daily practice, or use an electronic version of CGA in the office. Screening for cognitive impairment by performance of a Mini-Cog (which takes 2 to 3 minutes) could be the basis for the education of the patient and his or her family about the possibility of worsening cognition or functional dependency as a result of treatment and will allow them to make a more informed decision.

A registered nurse, physician assistant, or a nurse practitioner can be educated about these interventions and can become the champion of patient-centered care of the older adults. Any one of these interventions could be a major step forward in the care of the older patient with cancer in any oncology practice setting. Not all communities have allied health professionals to whom a patient can be referred if a geriatric syndrome is identified. However, awareness of the issues will lead to a search for local solutions, better decision making, better communication, and improved patient outcomes.

In conclusion, there are multiple approaches to the care of older adults with cancer. Understanding the function or cognition of the older patient who is treated for cancer is as important as understanding the blood pressure or heart rate of the patient, and any evaluation is better than no evaluation at all. Each practice will need to build a program unique to its resources and needs. All small steps will, in the end, benefit the care of this patient population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the Joachim Silbermann Family Program in Aging and Cancer and the Beatrice and Samuel A. Seaver Foundation for their commitment to the Program in Cancer and Aging.

Footnotes

Supported by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center core grant No. P30 CA008748.

Previously presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Cancer Survivorship Symposium: Advancing Care and Research, San Francisco, CA, January 15-16, 2016, and at the American Geriatric Society Annual Symposium, National Harbor, MD, May 11-14, 2011.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: Beatriz Korc-Grodzicki

Data analysis and interpretation: Beatriz Korc-Grodzicki

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Development of a Geriatric Service in a Cancer Center: Lessons Learned

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jop/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Beatriz Korc-Grodzicki

No relationship to disclose

William Tew

No relationship to disclose

Arti Hurria

Consulting or Advisory Role: GTx, Seattle Genentics, Boehringer Ingelheim, On Q Health, Sanofi, Optum Healthcare Solutions, Pieran Biosciences

Research Funding: GlaxoSmithKline, Celgene, Novartis

Heidi Yulico

No relationship to disclose

Stuart Lichtman

Consulting or Advisory Role: Magellan Health

Paul Hamlin

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Genentech/Roche,

Research Funding: Janssen, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Molecular Templates, Seattle Genetics

George Bosl

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine . Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurria A, Naylor M, Cohen HJ. Improving the quality of cancer care in an aging population: Recommendations from an IOM report. JAMA. 2013;310:1795–1796. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Extermann M, Overcash J, Lyman GH, et al. Comorbidity and functional status are independent in older cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1582–1587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korc-Grodzicki B, Boparai MK, Lichtman SM. Prescribing for older patients with cancer. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2014;12:309–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, et al. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1061–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp

- 7.Shahrokni A, Wu AJ, Carter J, et al. Long-term toxicity of cancer treatment in older patients. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:63–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fedarko NS. The biology of aging and frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balducci L. Frailty: A common pathway in aging and cancer. Interdiscip Top Gerontol. 2013;38:61–72. doi: 10.1159/000343586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2595–2603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenis C, Bron D, Libert Y, et al. Relevance of a systematic geriatric screening and assessment in older patients with cancer: Results of a prospective multicentric study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1306–1312. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puts MT, Santos B, Hardt J, et al. An update on a systematic review of the use of geriatric assessment for older adults in oncology. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:307–315. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamaker ME, Jonker JM, de Rooij SE, et al. Frailty screening methods for predicting outcome of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with cancer: A systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e437–e444. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dale W, Chow S, Sajid S. Socioeconomic considerations and shared-care models of cancer care for older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnuson A, Dale W, Mohile S. Models of care in geriatric oncology. Curr Geriatr Rep. 2014;3:182–189. doi: 10.1007/s13670-014-0095-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman AE, Swartz K, Schoppe J, et al. Development of a comprehensive multidisciplinary geriatric oncology center, the Thomas Jefferson University experience. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Help for Older Patients. https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/treatments/symptom-management/help-older-patients.

- 18.Zauderer MG, Sima CS, Korc-Grodzicki B, et al. Toxicity of initial chemotherapy in older patients with lung cancers. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shuman AG, Patel SG, Shah JP, et al. Optimizing perioperative management of geriatric patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2014;36:743–749. doi: 10.1002/hed.23347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tew WP, Fleming GF. Treatment of ovarian cancer in the older woman. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korc-Grodzicki B, Holmes HM, Shahrokni A. Geriatric assessment for oncologists. Cancer Biol Med. 2015;12:261–274. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2015.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chow WB, Rosenthal RA, Merkow RP, et al. Optimal preoperative assessment of the geriatric surgical patient: A best practices guideline from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:453–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moy B, Flaig TW, Muss HB, et al. Geriatric oncology for the 21st century: A call for action. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:241–243. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Besdine R, Boult C, Brangman S, et al: Caring for older Americans: The future of geriatric medicine. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:S245-S256, 2005 (suppl) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chun AK. When is it the right time to ask for a geriatrician? Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78:485–488. doi: 10.1002/msj.20268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sennour Y, Counsell SR, Jones J, et al. Development and implementation of a proactive geriatrics consultation model in collaboration with hospitalists. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2139–2145. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02496.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahrokni ATA, Downey RJ, Strong V, et al. Electronic rapid fitness assessment: A novel tool for preoperative evaluation of the geriatric oncology patient. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0018. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shahrokni A, Kim SJ, Bosl GJ, et al. How we care for an older patient with cancer. J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.017608. 13:95-102, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Decoster L, Van Puyvelde K, Mohile S, et al. Screening tools for multidimensional health problems warranting a geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: An update on SIOG recommendations. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:288–300. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed Up & Go: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]