Abstract

Purpose:

The benefits of hospice for patients with end-stage disease are well established. Although hospice use is increasing, a growing number of patients are enrolled for ≤ 7 days, a marker of poor quality of care and patient and family dissatisfaction. In this study, we examined variations in referrals among individuals and groups of physicians to assess a potential source of suboptimal hospice use.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective chart review of 452 patients with advanced cancer referred to hospice from a comprehensive cancer center. We analyzed patient length of service (LOS) under hospice care, looking specifically at median LOS and percent of short enrollments (%LOS ≤ 7), to examine the variation between individual oncologists and divisions of oncologists.

Results:

Of 394 successfully referred patients, median LOS was 14.5 days and %LOS ≤ 7 was 32.5%, consistent with national data. There was significant interdivisional variation in LOS, both by overall distribution and %LOS ≤ 7 (P < .01). In addition, there was dramatic variation in median LOS by individual physician (range, 4 to 88 days for physicians with five or more patients), indicating differences in hospice referral practices between providers (coefficient of variation > 125%). As one example, median LOS of physicians in the Division of Thoracic Malignancies varied from 4 to 33 days, despite similarities in patient population.

Conclusion:

Nearly one in three patients with cancer who used hospice had LOS ≤ 7 days, a marker of poor quality. There was significant LOS variability among different divisions and different individual physicians, suggesting a need for increased education and training to meet recommended guidelines.

INTRODUCTION

For nearly 2 decades, hospice has been recommended by major cancer organizations in the United States, including ASCO, as the best way for patients with terminal cancer to live their fullest lives.1 Hospice care has been associated with better quality of care,2 better survival in patients3-5 and surviving spouses,6 better perceptions of care by physicians7 and family members,8 and care that is more congruent with patient wishes.8 In addition, hospice and palliative care usage is associated with reduced costs to patients, hospitals, and the health care system,9-11 saving as much as $8,697 for each Medicare patient in the last year of life.12 Given these widespread benefits, ASCO recommends a hospice information visit during the 6 months before death, as triggered by a change in treatment regimen or performance status.13

Hospice use in the United States has increased dramatically over the past decade.14,15 In the 2003 to 2005 Cancer Care Outcomes Research & Surveillance Consortium study on cancer care outcomes, only 37% of the patients with metastatic lung cancer used hospice at all, and only one half reported even discussing hospice with their physicians within 4 to 7 months of diagnosis.16 Using these same data, researchers17 found that 47% of the patients received aggressive end-of-life care, including chemotherapy within 14 days of death (16%) and acute hospitalizations within 30 days of death (40%). Notably, patients who discussed end-of-life care with their physicians had significantly less aggressive therapies at the end of life and were more likely to use hospice and for longer periods of service. In contrast, more recent data from 2008 to 2010 found that hospice use in patients with lung cancer from two North Carolina hospitals reached as high as 74% (145 of 195).4

However, despite these increases in use, the use of hospice services is still suboptimal. There has been both a declining median length of service (LOS)15 and an increase in short LOS, both for ≤ 3 days18 and for ≤ 7 days.19 This is a concerning trend, given that these short LOSs are associated with poorer outcomes, including higher rates of major depression,20,21 poorer pain management,22 and worse helpfulness ratings.23 These findings point to a need for providers to refer patients to hospice earlier in disease progression and care.

This study aimed to investigate the potential variation in hospice referrals of patients with terminal cancer at a comprehensive cancer center. Specifically, the purpose of the study was to elucidate the differences between divisions of medical oncologists, as well as between individual care providers who treat the same disease, as measured by the length of time that patients with end-stage disease are under hospice care. Although other studies have compared disparities in hospice referrals among different divisions of oncologists,24 our study is novel for two reasons: (1) we used LOS ≤ 7 days as an outcome, an established quality metric25 that has not been used in these studies; and (2) we investigated the variation among individual physicians within a division, which would indicate potential inconsistency among providers in offering quality end-of-life care. These findings will allow us to associate specific clinical decisions by individual physicians or divisions as one cause for suboptimal hospice referrals. In turn, we can then perform targeted education as needed to improve end-of-life and advanced-care planning discussions, an identified area of poor performance among physicians.26

METHODS

This was a retrospective chart review of patients with advanced cancer with end-stage disease from the Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center (SKCCC). Our system does not track patients from diagnosis to death, so we were able to collect data only on those patients referred to our largest hospice provider, Gilchrist Hospice. Gilchrist is a preferred provider serving the greater community directly surrounding SKCCC and it services more than one half of our referrals. After cross matching patients using data from both SKCCC and Gilchrist Hospice, we identified a primary diagnosis, a primary medical oncologist, an initial referral date to hospice, a hospice enrollment date, a hospice discharge date, and special circumstances surrounding the referral process: whether the patient declined hospice services, was deemed inappropriate for hospice, was admitted to the hospital while on hospice services, or died between referral and enrollment to hospice services (recorded as LOS = 0). Patients were referred to Gilchrist Hospice from July 1, 2013, to March 31, 2015.

Four hundred fifty-two patients were identified as having the following characteristics: (1) having a cancer diagnosis, (2) having an assigned primary medical oncologist, and (3) having not initially declined anticancer treatment. This final criterion served to rule out those with extreme end-stage disease on presentation with only hospice as a treatment option. LOS was defined as the time patients were on services of Gilchrist Hospice before death. We assumed interchangeability between date of hospice discharge and date of death; nationally, the proportion of patients who are disenrolled from hospice before death is approximately 10%,19 consistent with numbers from Gilchrist Hospice (data not shown). One patient was still living and under hospice service at the time of analysis; we censored this individual as having a discharge date of September 1, 2015.

Patients were categorized into eight divisions by oncologist subspecialty: hematologic malignances, neuro-oncology, breast malignancies, GI malignancies, thoracic malignancies, head and neck malignancies, melanomas and sarcomas, and genitourinary malignancies. LOS median and distribution were compared with national data provided by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization15 (for all hospice patients in the United States) and Medicare (for all hospice patients with primary end-stage cancer diagnoses in the United States; J. Teno, personal communication, August 2015).

Differences in LOS were analyzed among divisions and physicians, looking specifically at median and short LOS (≤ 7 days; referred to as %LOS ≤ 7). To compare among divisions and given the skewed nature of the LOS data, we used nonparametric tests (the Kruskal-Wallis rank test and the χ2 test), using α = 0.05. We further calculated the coefficient of variation for each division as a metric of variability among physicians within the same division, using physician median LOS in the following calculation: , representing the ratio of the sample SD (s) to the sample mean . This is an indicator of the degree of variation within a group, with typically considered high variance. The χ2 test was further used to analyze reasons for declining referrals among divisions. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA Version 12 (STATA, College Station, TX).

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine institutional review boards.

RESULTS

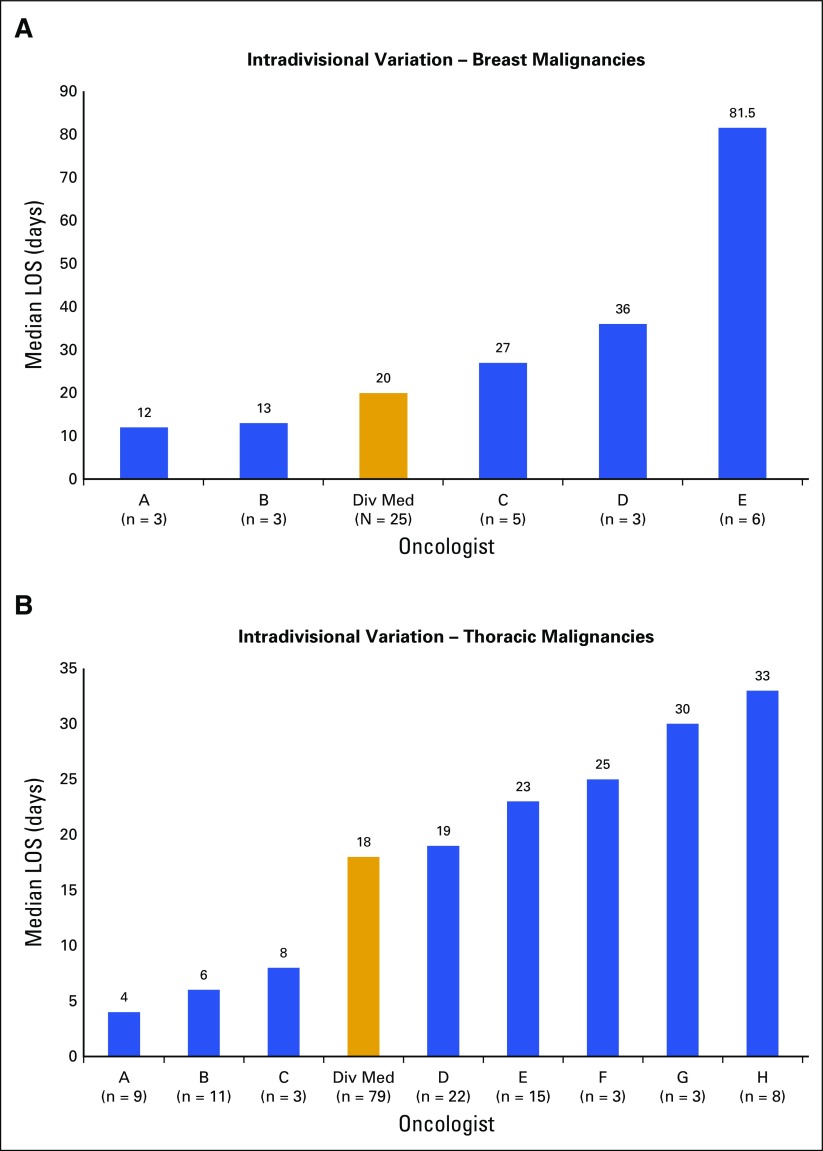

Overall data are summarized and are compared with national data in Table 1. From our original sample of 452 patients, 58 were not successfully referred to hospice, either because of patient or family declination of services or because the patient was ruled inappropriate for services, leaving 394 successfully referred patients. Median LOS of this remaining sample was 14.5 days (range, 0 to 473 days; interquartile range [IQR], 5 to 37 days), and LOS spread was roughly consistent with national distributions for all hospice patients.15 As expected, the distribution of LOS was highly skewed, with a large proportion of patients entering hospice services within the last few weeks of life. A total of 32.5% of patients (128 of 394) had LOS ≤ 7 days, including 5.1% (20 of 394) who died before reaching hospice services. This is roughly equivalent to the national rate of 35.5% among all hospice patients. In contrast, 7.6% of patients (30 of 394) had a long LOS (≥ 90 days), compared with a national rate of 19.0%.

Table 1.

Summary of Total Patient Data

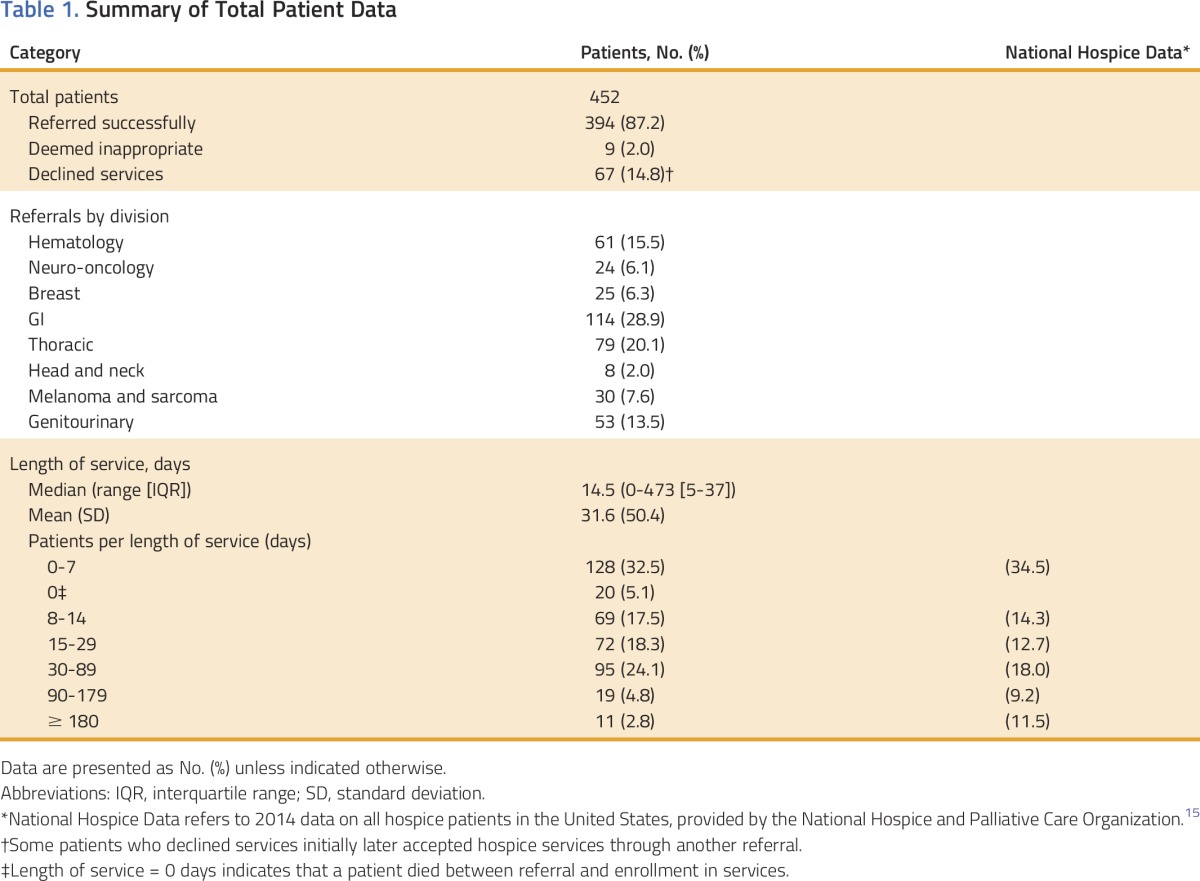

We compared LOS metrics among different divisions. Distributions of LOS, as measured by indicators of central tendency and listed in Table 2, varied widely, with head and neck malignancies having the longest LOS (median, 37.0 days; IQR, 7 to 72 days) and hematologic malignancies having the shortest LOS (median, 7 days; IQR, 3 to 16 days). Neuro-oncology had the lowest %LOS ≤ 7 (12.5%), whereas hematologic malignancies had the highest %LOS ≤ 7 (54.1%). These differences in LOS were statistically significant, both for LOS distribution (Kruskal-Wallis rank test on LOS, P < .01) and for short LOS (χ2 test on %LOS ≤ 7, P < .01). Of note, these analyses treated all patients independent from one another; that is, we assumed that there was no confounding on the basis of LOS groupings of patients treated by the same provider. We confirmed this assumption by performing a multilevel mixed-effects linear regression with a random intercept for physicians. This test revealed a near-zero intraclass correlation, thus showing little evidence of confounding, and validating our other analyses.

Table 2.

Comparisons Among Divisions

When comparing with 2012 Medicare data (J. Teno, personal communication, August 2015) regarding specific cancer diagnoses, most divisions performed comparably for median LOS, all within 4 days of national medians. GI malignancies performed least favorably (−4 days compared with national data); however, the selected national data comparison diagnosis (colorectal cancer, median LOS = 20 days) excludes pancreatic and hepatocellular cancer, each with lower LOS nationally (LOS = 16 and 13 days, respectively) and perhaps explains this gap. The divisions of neuro-oncology, head and neck malignancies, and melanomas and sarcomas did not have specific points of comparison from national data.

To assess interphysician variability, we coalesced patient data into median LOS and %LOS ≤ 7 by physician. There was a wide distribution in both metrics: median LOS by physician ranged from 0 to 157.5 days (4 to 88 days when restricted to physicians with five or more patients), and %LOS ≤ 7 by physician ranged from 0% to 100% (even when this sample was restricted to physicians with five or more patients). Our overall was 125.24%, indicating a high degree of variability (> 100%). Looking at individual divisions, all divisions surpassed 50% and many surpassed the 100% threshold (Table 2). Thus, there was significant variation in LOS among physicians, both overall and within specific divisions, despite sharing the same population of patients.

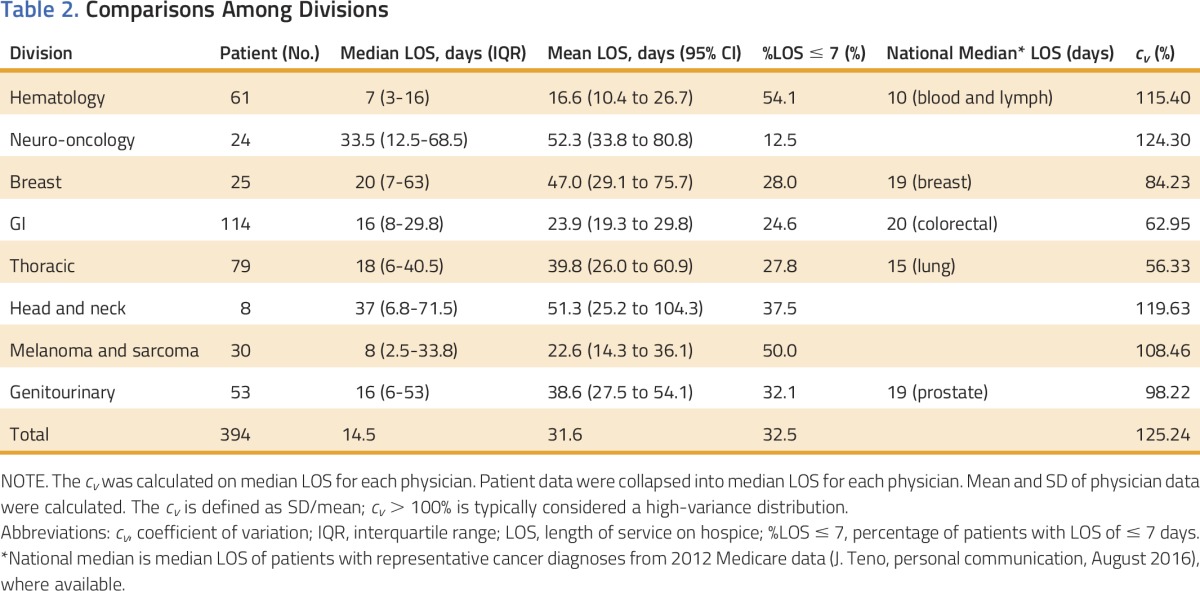

We identified two divisions with high diagnostic consistency: breast malignancies and thoracic malignancies; all patients with breast malignancy (25 of 25) had breast cancer, and most patients with thoracic malignancy (71 of 79; 89.9%) had lung cancer, increasing the similarities between these patients and perhaps highlighting physician variability more directly. Median LOS for those with three or more patients ranged from 12 to 81.5 days (breast) and from 4 to 33 days (thoracic), which still displayed a high degree of inconsistency among providers. The distributions by physician median LOS for these two divisions are displayed in Figure 1.

Fig 1.

Intradivision variation: median LOS by physician for the divisions of breast malignancies and thoracic malignancies (n = number of patients). Note that the Div Med includes all patients in the division, whereas only physicians with three or more patients are depicted in individual bars. Div Med, division median; LOS, length of service.

We further analyzed special circumstances surrounding hospice referrals. Sixty-seven patients (14.82% of the original set of 452 patients) had a least one instance of declined services after referral; interdivisional variation of this occurrence approached significance (χ2[7] = 13.6545, P = .058). Nine patients (2.0%) were deemed inappropriate for services after referral. Eleven patients (2.4%) had at least one hospital admission during hospice services. Neither metrics reached significance for variability among divisions (all P > .540). Twenty-one patients (4.7% of original set; 5.1% of included patients) died between referral and reaching hospice services. Variation was statistically significant (χ2[7] = 15.6228, P < .05), with melanoma and sarcoma having 15.8% of patients (6 of 38) in such a category, and neuro-oncology and breast malignancies having none.

DISCUSSION

We report several findings of interest to oncology practice. First, consistent with national data, approximately one third of patients were still regularly referred to hospice less than 1 week before death, despite consistent guidelines for early end-of-life care discussions for all patients with end-stage cancer.13,27-29 Available data indicate that these discussions are associated with earlier use of hospice and less intensive treatments at the end of life,8,30,31 especially when taking place earlier in a patient’s disease course.17,32 Furthermore, they are associated with better understanding of prognosis,33 better family satisfaction with care,8 and better quality of life.34-36 However, despite these findings, these discussions often take place late in a patient’s care, if at all.37

Although many factors are not under the control of the oncologist, research has identified physician decision making, including inadequate physician communication and not recognizing the patient as dying, as the most frequently identified cause of late hospice referrals by patients’ bereaved family members.38 Taken together, these data call for a need for increased awareness of physicians to discuss goals of care earlier in disease processes. Indeed, these practice guidelines are consistent with the care physicians would want for themselves.39

Second, we found significant variation in hospice referral patterns from division to division, as measured by (1) median LOS, (2) proportion of short LOS (%LOS ≤ 7), and (3) deaths before reaching hospice services, all among patients with end-stage cancer referred to hospice. Notably, this is despite similarities in the disease course of patients with terminal cancer in the last 6 months of life,40 suggesting that these variations reflect disparities in the use of hospice beyond those explained by medical differences. Furthermore, the variation in our data mirrored the variation in national hospice use for different cancer diagnoses as well,41 illustrating nationwide disparities in hospice referral times for different patients.

Certain individual divisions were identified as having more or less optimal hospice referral practices. Notably, the division of hematologic malignancies had the shortest LOS, with a majority of patients (54.1%) having LOS ≤ 7 days. The high proportion of patients in this division with short LOS explained much of the variation across all divisions in this metric. This finding is consistent with both national Medicare data and previous research, which has identified poorer hospice use for patients with hematologic malignancy, as compared with patients with solid tumors (J. Teno, personal communication, August 2015).41-45 This disparity is likely a result of several factors, but may be explained in part by the use of palliative chemotherapy and blood transfusions late in the disease course, a practice that is shown to be effective46 and desired,47 but also cost prohibitive for hospice facilities.48 Further work is required to identify cost-effective solutions to provide quality end-of-life care to these patients.

Third, and perhaps most notably, we found the presence of significant variation in hospice referral patterns from physician to physician, even among those within the same division. That is, among physicians treating the same patients (sharing diagnoses, patient demographics, and nonmedical factors), there were still sizeable differences in how these patients were referred to hospice. These disparities are likely indicative of variations in physician knowledge of, familiarity with, and perspectives regarding hospice. Consistent with this, there are well-documented, widespread variations in patients’ perceptions and usage of hospice,19,49-54 with recent work also identifying such disparities among physicians.55,56 Given the widely accepted benefits of hospice, our findings suggest significant discrepancies among physicians in providing quality end-of-life care to patients with advanced cancer. These data call for a need to review hospice referral practices and inconsistencies, as well as a need to further inform patients and physicians alike.

Our study has several limitations that warrant discussion. First, we restricted our analysis to patients at a single institution and a single hospice service. Gilchrist Services provides more than one half of the hospice care to our patients in the surrounding catchment area; we were unable to get similar data from the smaller hospices. However, given the similarities between our data and national data, as well as a reasonably large sample size, we feel confident in the applicability of our findings to the broader medical community. Second, by using only LOS as our outcome, we may have missed many individual factors of the patient experience; for example, a patient may have declined hospice until 7 days before death despite a high quality of care and timely discussion with the medical oncologist. Although this is a valid concern, previous literature has shown the strong relationship between LOS and quality of care, and it represents a more feasible way for institutions to measure hospice referral practices on a broad scale. Finally, the study does not account for changes and advances in cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment, such as targeted therapies that may keep patients on cancer treatment longer. To minimize this, we used the most recent cohort of patients and compared our data with national data from the same time period as well as the most recent literature on hospice use. Furthermore, although there were advances in targeted therapies during the period of our analysis, there were no new curative treatments or findings that changed the prognosis of patients with malignant effusions, carcinomatosis, hypercalcemia, decline in performance status, or other indicators of late-stage disease.

Thus, in conclusion, there was significant variation in LOS among both divisions and individual physicians, calling for better training for medical oncologists regarding discussions of hospice. To address this need, we have presented our data at division meetings, creating an individualized score card showing physicians how they compare with peers locally and nationally. This feedback has been well received, as we concurrently teach direct methods of making a hospice information visit for patients with late-stage disease, as suggested by ASCO.13 We also encourage palliative care referrals, which have been shown to increase eventual hospice referrals two- to 10-fold.57-61 Similar direct-feedback methods have been shown to improve quality of care through other metrics62,63; indeed, one large practice doubled hospice length of stay from 20 to 40 days by making earlier referrals a quality initiative.64 We plan to reaudit in 1 year.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by the Dean’s Summer Research Opportunity from The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (X.W.), NCI Core Grants P 30 006973, 1 R01 CA177562-01A1, and 1-R01 NR014050 01 (T.S.), and the Harry J. Duffey Family Endowment for Palliative Care. Presented at the High Value Care Symposium, the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety & Quality, Johns Hopkins Health System, Baltimore, MD, February 1, 2016; the Medical Student Research Symposium, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, February 5, 2016; the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, June 6, 2016; and the Academy of Health Annual Research Meeting, Baltimore, MD, June 26, 2016. We thank Joan Teno, MD, for providing Medicare hospice data.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Xiao Wang, Louise S. Knight, Thomas J. Smith

Financial support: Thomas J. Smith

Administrative support: Louise S. Knight, Thomas J. Smith

Provision of study materials or patients: Louise S. Knight, Anne Evans, Thomas J. Smith

Collection and assembly of data: Xiao Wang, Louise S. Knight, Anne Evans, Thomas J. Smith

Data analysis and interpretation: Xiao Wang, Louise S. Knight, Jiangxia Wang, Thomas J. Smith

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Variations Among Physicians in Hospice Referrals of Patients With Advanced Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jop/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Xiao Wang

No relationship to disclose

Louise S. Knight

No relationship to disclose

Anne Evans

No relationship to disclose

Jiangxia Wang

No relationship to disclose

Thomas J. Smith

Employment: UpToDate

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith TJ, Schnipper LJ. The American Society of Clinical Oncology program to improve end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 1998;1:221–230. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1998.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamagishi A, Sato K, Miyashita M, et al. Changes in quality of care and quality of life of outpatients with advanced cancer after a regional palliative care intervention program. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48:602–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connor SR, Pyenson B, Fitch K, et al. Comparing hospice and nonhospice patient survival among patients who die within a three-year window. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duggan KT, Hildebrand Duffus S, D’Agostino RB, Jr, et al. The impact of hospice services in the care of patients with advanced stage nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:29–34. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito AM, Landrum MB, Neville BA, et al. Hospice care and survival among elderly patients with lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:929–939. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. The health impact of health care on families: A matched cohort study of hospice use by decedents and mortality outcomes in surviving, widowed spouses. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:465–475. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickens DS. Comparing pediatric deaths with and without hospice support. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:746–750. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA. 2016;315:284–292. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley AS, Deb P, Du Q, et al. Hospice enrollment saves money for Medicare and improves care quality across a number of different lengths-of-stay. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:552–561. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pyenson B, Connor S, Fitch K, et al. Medicare cost in matched hospice and non-hospice cohorts. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith TJ, Cassel JB. Cost and non-clinical outcomes of palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:32–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, et al. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312:1888–1896. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connor SR. U.S. hospice benefits. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization: NHPCO's Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. Alexandria, VA, National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 2015

- 16.Huskamp HA, Keating NL, Malin JL, et al. Discussions with physicians about hospice among patients with metastatic lung cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:954–962. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: A prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4387–4395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA. 2013;309:470–477. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.207624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aldridge MD, Canavan M, Cherlin E, et al. Has hospice use changed? 2000-2010 utilization patterns. Med Care. 2015;53:95–101. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley EH, Prigerson H, Carlson MD, et al. Depression among surviving caregivers: Does length of hospice enrollment matter? Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2257–2262. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kris AE, Cherlin EJ, Prigerson H, et al. Length of hospice enrollment and subsequent depression in family caregivers: 13-month follow-up study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:264–269. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000194642.86116.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller SC, Mor V, Teno J. Hospice enrollment and pain assessment and management in nursing homes. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26:791–799. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rickerson E, Harrold J, Kapo J, et al. Timing of hospice referral and families’ perceptions of services: Are earlier hospice referrals better? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:819–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ledoux M, Rhondali W, Lafumas V, et al: Palliative care referral and associated outcomes among patients with cancer in the last 2 weeks of life. BMJ Support Palliat Care 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000791 [epub ahead of print on Sept 23, 2015] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Society of Clinical Oncology: Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI). Certification Measures 2016. http://www.instituteforquality.org/qopi/measures [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horne G, Payne S, Seymour J: Do patients with lung cancer recall physician-initiated discussions about planning for end-of-life care following disclosure of a terminal prognosis? BMJ Support Palliat Care 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001015 [epub ahead of print on February 3, 2016] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaye EC, Friebert S, Baker JN. Early integration of palliative care for children with high-risk cancer and their families. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:593–597. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hui D, Bruera E. Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:159–171. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy MH, Back A, Benedetti C, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:436–473. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar P, Temel JS. End-of-life care discussions in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3315–3319. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahluwalia SC, Tisnado DM, Walling AM, et al. Association of early patient-physician care planning discussions and end-of-life care intensity in advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:834–841. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu PH, Landrum MB, Weeks JC, et al. Physicians’ propensity to discuss prognosis is associated with patients’ awareness of prognosis for metastatic cancers. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:673–682. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox K, Wilson E, Jones L, et al. An exploratory, interview study of oncology patients’ and health-care staff experiences of discussing resuscitation. Psychooncology. 2007;16:985–993. doi: 10.1002/pon.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desai MJ, Kim A, Fall PC, et al. Optimizing quality of life through palliative care. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2007;107:ES9–ES14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Institute of Medicine . Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mack JW, Cronin A, Taback N, et al. End-of-life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:204–210. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teno JM, Casarett D, Spence C, et al. It is “too late” or is it? Bereaved family member perceptions of hospice referral when their family member was on hospice for seven days or less. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chinn GM, Liu PH, Klabunde CN, et al. Physicians’ preferences for hospice if they were terminally ill and the timing of hospice discussions with their patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:466–468. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salpeter SR, Malter DS, Luo EJ, et al. Systematic review of cancer presentations with a median survival of six months or less. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:175–185. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Connor NR, Hu R, Harris PS, et al. Hospice admissions for cancer in the final days of life: Independent predictors and implications for quality measures. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3184–3189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.8817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brock KE, Steineck A, Twist CJ. Trends in end-of-life care in pediatric hematology, oncology, and stem cell transplant patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:516–522. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LeBlanc TW, Abernethy AP, Casarett DJ. What is different about patients with hematologic malignancies? A retrospective cohort study of cancer patients referred to a hospice research network. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Earle CC, et al: Hospice use among patients with lymphoma: Impact of disease aggressiveness and curability. J Natl Cancer Inst 108:pii, 2015 (abstr) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sexauer A, Cheng MJ, Knight L, et al. Patterns of hospice use in patients dying from hematologic malignancies. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:195–199. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mercadante S, Ferrera P, Villari P, et al. Effects of red blood cell transfusion on anemia-related symptoms in patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:60–63. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meystre CJ, Burley NM, Ahmedzai S. What investigations and procedures do patients in hospices want? Interview based survey of patients and their nurses. BMJ. 1997;315:1202–1203. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7117.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wright AA, Katz IT. Letting go of the rope--aggressive treatment, hospice care, and open access. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:324–327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cagle JG, Van Dussen DJ, Culler KL, et al. Knowledge about hospice: Exploring misconceptions, attitudes, and preferences for care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33:27–33. doi: 10.1177/1049909114546885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Goldstein R. Ethnic differences in hospice enrollment following inpatient palliative care consultation. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:598–600. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hardy D, Chan W, Liu CC, et al. Racial disparities in the use of hospice services according to geographic residence and socioeconomic status in an elderly cohort with nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:1506–1515. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laguna J, Enguídanos S, Siciliano M, et al. Racial/ethnic minority access to end-of-life care: A conceptual framework. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2012;31:60–83. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2011.641922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwak J, Haley WE, Chiriboga DA. Racial differences in hospice use and in-hospital death among Medicare and Medicaid dual-eligible nursing home residents. Gerontologist. 2008;48:32–41. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramey SJ, Chin SH. Disparity in hospice utilization by African American patients with cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2012;29:346–354. doi: 10.1177/1049909111423804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cherny NI, Catane R, European Society of Medical Oncology Taskforce on Palliative and Supportive Care Attitudes of medical oncologists toward palliative care for patients with advanced and incurable cancer: Report on a survery by the European Society of Medical Oncology Taskforce on Palliative and Supportive Care. Cancer. 2003;98:2502–2510. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO, Jr, et al. Physician factors associated with discussions about end-of-life care. Cancer. 2010;116:998–1006. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Highet BH, Hsieh YH, Smith TJ. A Pilot trial to increase hospice enrollment in an inner city, academic emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2016;51:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:454–463. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tangeman JC, Rudra CB, Kerr CW, et al. A hospice-hospital partnership: Reducing hospitalization costs and 30-day readmissions among seriously ill adults. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:1005–1010. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brody AA, Ciemins E, Newman J, et al. The effects of an inpatient palliative care team on discharge disposition. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:541–548. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:1356–1361. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blayney DW, McNiff K, Hanauer D, et al. Implementation of the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative at a university comprehensive cancer center. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3802–3807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neuss MN, Malin JL, Chan S, et al. Measuring the improving quality of outpatient care in medical oncology practices in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1471–1477. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Von Gunten CF: A quality improvement approach to oncologist referrals for hospice care. J Clin Oncol 34, 2016 (suppl 26S; abstr 45) [Google Scholar]