Abstract

Background: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by multiple organ involvement. Lupus nephritis (LN) is a common manifestation with a wide variety of histological appearances. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) 2 and 9 are gelatinases capable of degrading glomerular basement membrane type IV collagen, which have been associated with LN. We examine the expression of MMP2 and MMP9 in different classes of LN.

Methods: MMP2 and MMP9 expression was detected by immunohistochemistry in sections from renal biopsy specimens with class III, class IV and class V LN (total n = 31), crescentic immunoglobulin A nephropathy (n = 6), pauci-immune glomerulonephritis (n = 7), minimal change disease (n = 2), mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (n = 7), diabetic nephropathy (n = 12) and histologically normal controls (n = 8).

Results: MMP2 and MMP9 were not expressed in all classes of LN, but were observed in LN with cellular and fibrocellular crescents. MMP2/MMP9 was expressed in cellular and fibrocellular crescents regardless of glomerulonephritis but not observed in inactive fibrous crescents or with mesangial proliferation. This suggests that MMP2 and MMP9 are involved in the development of extracapillary proliferative lesions.

Conclusions: MMP2/MMP9 is expressed with active extracapillary proliferation. Further study is necessary to define whether the expression of MMP2/MMP9 reflects a role in glomerular repair after injury, a role in organ-level immune responses or a role as a marker of epithelialization.

Keywords: crescentic glomerulonephritis, glomerulonephritis, immunoglobulin A nephropathy, metalloproteinase, systemic lupus erythematosus

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by autoantibody production and multiple organ involvement. Lupus nephritis (LN) is a common manifestation, occurring in over half of patients [1, 2] and strongly associated with increased mortality and morbidity [3]. Several risk factors have been associated with predisposition towards LN such as the presence of autoantibodies including anti-Sm and anti-dsDNA [4, 5], epitopes within the kidneys inducing immune responses [6], and genetic predisposition [7]. The histopathologic presentations of LN are diverse, broadly manifesting in mesangial, endothelial or epithelial patterns [8]. This heterogeneous involvement of SLE is likely a consequence of the different pathogenic triggers in each individual [9, 10].

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are innate receptors that recognize invariate pattern motifs and are strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of both human SLE and its associated murine models. [11] One consequence of TLR stimulation is production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) [12], a family of enzymes that degrade connective tissues such as collagen, laminins and gelatin. MMP2 and MMP9 are gelatinases capable of degrading glomerular basement membrane (GBM) type IV collagen and are therefore particularly relevant to kidney diseases. These enzymes are active in the glomeruli of NZB × NZW mice during nephritis, but not in pre-nephritic glomeruli [13]. This finding has been strengthened by the observed upregulation of MMP production by F4/80hi-activated macrophages in active murine lupus nephritis but not quiescent disease [14]. Further, it has been proposed that MMPs regulate CD4 and CD8 activation, as well as CD8+ T cell migration [15], and this may be a mechanism through which MMPs contribute to the lupus phenotype. This is supported by the observation that ‘MMP9’ deficiency exaggerates murine SLE-like disease [16].

Despite a strong association, the role of MMP2 and MMP9 in LN requires elucidation. Both mRNA transcripts and protein expression of MMP2 and MMP9 are reported to be elevated in class-IV LN [17]. In contrast, it has been reported that MMP2 is not increased in LN and MMP9 is associated with mesangial proliferation in any type of glomerulonephritides [18]. Therefore, it is unclear whether MMP2 and MMP9 are elevated in glomerulonephritis or LN, and whether increased expression of MMP2 and MMP9 are specific to class-IV LN or other histopathological manifestations of LN. We therefore aim to determine the expression profile of MMP2 and MMP9 in different forms of LN.

Materials and methods

Cohort and scoring

Patients were identified from the ACT Health Department of Renal Medicine electronic medical record. Patient classification was based on clinical and histopathological report at time of biopsy. All biopsy sections were collected during routine clinical practice. The study was approved by the ACT Human Research and Ethics Committee (HREC). All reading of slides was performed independently by two pathologists.

Biopsies were classified according to the modified (1982) WHO classification of LN. Sections were recut from archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks at 3 μm and dried for 10 min at 60°C. Heat retrieval was performed for 36 min in CC1 buffer. The MMP2 antibody (Spring Bioscience, E18014) was used at a dilution of 1/100 and incubated for 36 min. The MMP9 antibody (Spring Bioscience, E3664) was used at a dilution of 1/200 and incubated for 40 min. The Ventana Ultraview Alkaline Phosphatase Red Detection Kit was used to amplify and visualize the signal. The tissue was counterstained with haematoxylin and a blueing agent to visualize cell nuclei.

Results

Patients were identified retrospectively from the ACT Health Electronic Medical Record system. Patients were classified according to the WHO class [19] reported at the time of diagnosis. Our cohort was largely female with modest renal impairment, as expected (Table 1). Extracapillary proliferation was confirmed by silver stain (Supplementary Figure S1A). Baseline epidemiology of the different histological subgroups roughly approximated those documented in the literature for both Australian [20, 21] and worldwide [22] data (Table 1). The exception was the immunoglobulin A (IgA) cohort, which differed in that it was uncharacteristically dominated by female patients. This difference likely reflects the relatively low numbers of patients from each histologic subgroup.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of cohort

| Total LN | Class-II LN | Class-III LN | Class-IV LN | Class-V LN | Inactive LN | PIGN | Crescentic IgAN | MCD | DN | MCGN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 31 | 1 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 7 |

| Median age (IQR) (years) | 31 (12.5) | 27 (0) | 32.5 (13) | 30 (13.5) | 31 (16) | 32 (1) | 63 (14) | 28.5 (6.75) | 77.5 (6.5) | 62 (16) | 46 (19.5) |

| Female (%) | 77.40 | 0 | 60 | 80 | 100 | 40 | 57 | 83.30 | 50 | 41.7 | 12.5 |

| Median serum creatinine (IQR) (μmol/L) | 88 (75) | 153 (0) | 80 (51.5) | 88 (226) | 84 (22) | 88 (71) | 268 (162.5) | 109 (103.75) | 116 (0) | 292 (188) | 188 (153) |

IQR, interquartile range; PIGN, pauci-immune glomerulonephritis; MCD, minimal change disease; DN, diabetic nephropathy; MCGN, mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis; IgAN, immunoglobulin A nephritis.

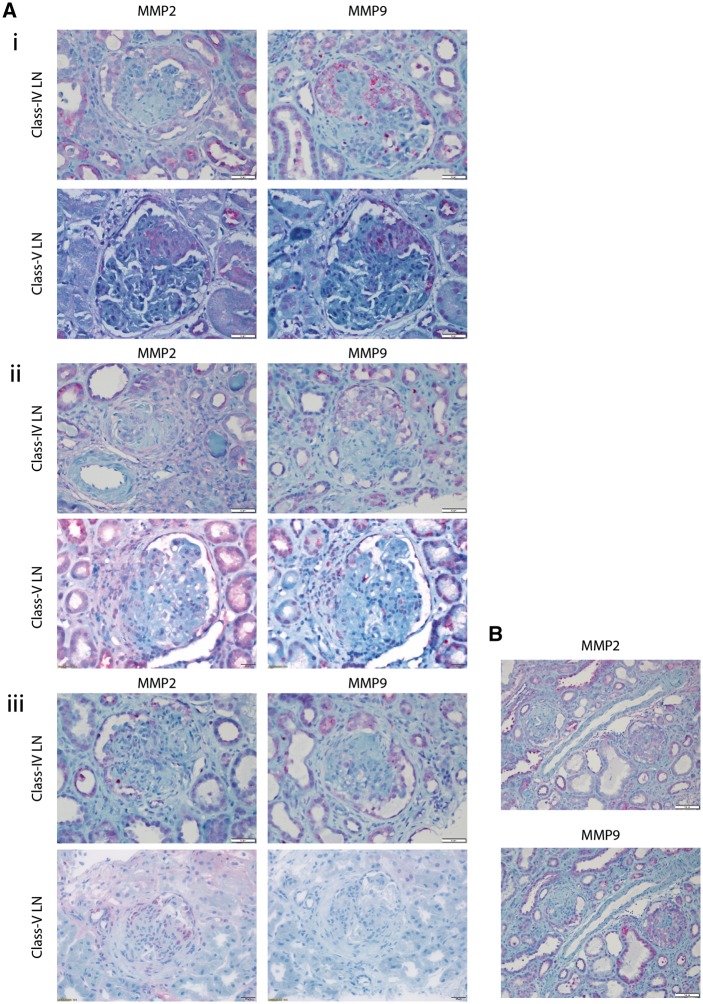

We first tested MMP2 and MMP9 expression in histopathologically normal biopsies. In biopsies (n = 8), expression of MMP2 and MMP9 was observed in proximal tubular epithelium, but not in glomerular tissue (Supplementary Figure S1B). Next, we tested for MMP2/MMP9 expression in biopsies of class-III, class-IV and class-V LN. Class-I and class-II LN were not examined due to insufficient biological samples. Of the class-III LN biopsies (n = 6), the average number of glomeruli per slide was 15 (range 7–25). Contrary to prior studies [18, 23], MMP2/MMP9 was not observed in glomerular or mesangial areas in the presence or absence of crescentic glomerulonephritis. Of the class-IV LN (n = 9), on average 17 glomeruli per slide were observed (range 10–34). MMP2 and MMP9 were not detected in the mesangium of any slide, but were present in cellular (n = 31) and fibrocellular (n = 12) crescents (Figure 1A). Neither MMP2 nor MMP9 was detected in fibrous crescents (n = 8) (Figure 1). Similarly, in all patients with class-V LN (n = 8) in which cellular (n = 18) and fibrocellular (n = 1) crescents were present in glomerular sections, MMP2 and MMP9 were positive (Figure 1A). Fibrous crescents did not stain for MMP2 or MMP9. These results are summarized in Table 2. Glomeruli from patients diagnosed with either class-III, class-IV or class-V LN did not express MMP2 or MMP9 in the absence of crescents (Figure 1B, Supplementary Figure S1B). Together, these results suggest that MMP2/MMP9 is expressed during active or resolving crescentic LN and not in LN in general.

Fig. 1.

(A) (i) MMP2 or MMP9 staining of cellular crescents in patients with LN, (ii) MMP2 or MMP9 staining of fibrocellular crescents in patients with lupus nephritis and (iii) MMP2 or MMP9 staining of fibrous crescents in patients with LN. (B) MMP staining of glomeruli with both fibrous and cellular demonstrating specificity of MMP expression to cellular crescents.

Table 2.

MMP2/MMP9 scores for LN crescentic glomerulonephritis

| WHO class (number) | Number of glomeruli per section (median and range) | MMP | Cellular crescent (positive/total) | Fibrocellular crescents (positive/total) | Fibrous crescents (positive/total) | Mesangium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class-III (n = 6) | 15 (7–25) | |||||

| MMP2 positive | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | Negative | ||

| MMP9 positive | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | Negative | ||

| Class-IV (n = 9) | 25 (10–34) | |||||

| MMP2 positive | 31/31 | 12/12 | 1/8 | Negative | ||

| MMP9 positive | 31/31 | 8/12 | 0/8 | Negative | ||

| Class-V (n=8) | 19 (4–31) | |||||

| MMP2 positive | 18/18 | 1/1 | 0/4 | Negative | ||

| MMP9 positive | 18/18 | 1/1 | 0/4 | Negative |

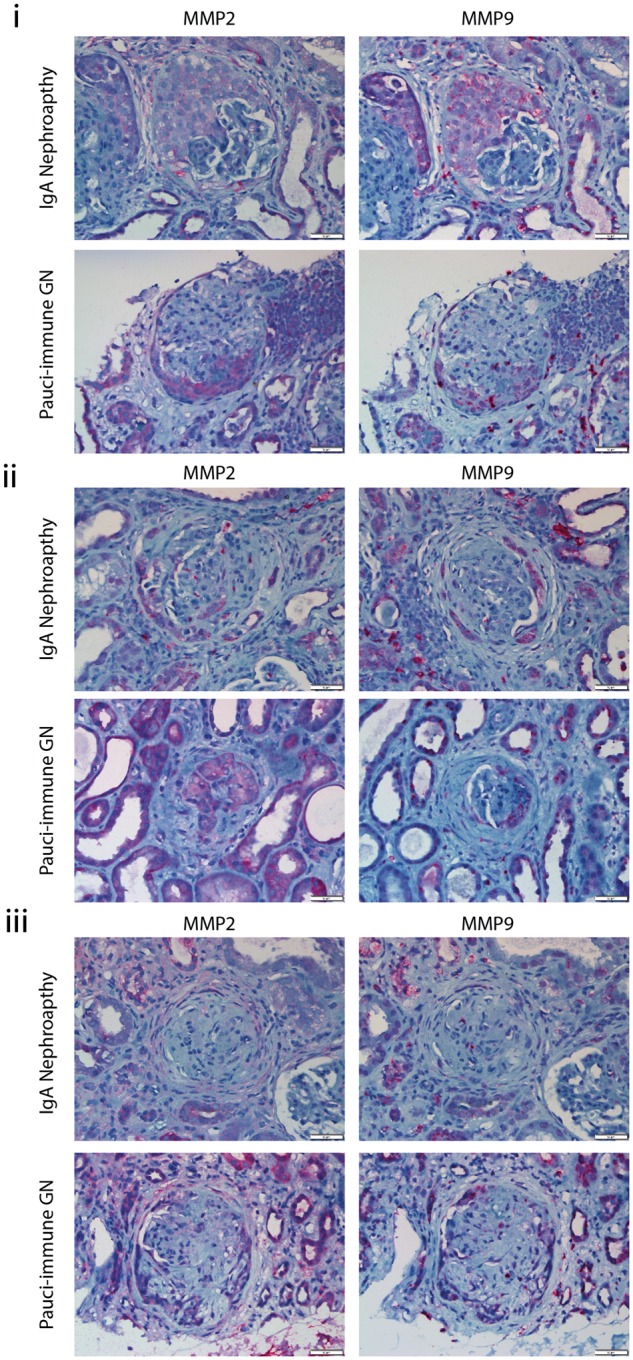

To test if MMP2 and MMP9 may be observed in crescentic and non-crescentic glomerulonephritis unrelated to LN, we then stained kidney sections with pauci-immune glomerulonephritis (PIGN) (n = 7), crescentic IgA (n = 6), diabetic nephropathy (n = 12) and mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (MCGN) (n = 7). Sections from biopsies with PIGN averaged 16 glomeruli per section (range 6–31) and similar to LN sections, all cellular (n = 33) and fibrocellular (n = 5) crescents were positive for both MMP2 and MMP9, whereas fibrous crescents (n = 5) did not stain for MMP2 and MMP9 (Figure 2). Sections from biopsies with crescentic IgA nephropathy had on average 10 glomeruli per section (range 4–17) and all sections with cellular crescents (n = 8) were positive for both MMP2 and MMP9. Diabetic nephropathy biopsies averaged 22 glomeruli per section (range 10–40) and did not demonstrate MMP2/MMP9 in the mesangium. Sections from MCGN averaged 17 glomeruli per section (range 1–35). Two sections had active crescents that were positive for both MMP2 and MMP9, and negative for both in the mesangium. These results are summarized in Table 3. This suggests that the expression of MMP2 and MMP9 is not specific to LN, but is important during development of extracapillary proliferative lesions.

Fig. 2.

(i) MMP2 or MMP9 staining of cellular crescents in patients with IgA nephropathy, PIGN, diabetic nephropathy or MCGN. (ii) MMP2 or MMP9 staining of fibrocellular crescents in patients with IgA nephropathy. (iii) MMP2 or MMP9 staining of fibrous crescents in patients with IgA nephropathy, PIGN, diabetic nephropathy or MCGN.

Table 3.

MMP2/MMP9 scores for non-LN crescentic and non-crescentic glomerulonephritis

| Diagnosis | Number of glomeruli per section (median and range) | MMP | Cellular crescent (positive/total) | Fibrocellular crescents (positive/total) | Fibrous crescents (positive/total) | Mesangium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIGN (n=7) | 14 (6–31) | |||||

| MMP2 positive | 33/33 | 5/5 | 0/5 | Negative | ||

| MMP9 positive | 33/33 | 5/5 | 0/5 | Negative | ||

| Crescentic IgA nephropathy (n=6) | 10 (4–17) | |||||

| MMP2 positive | 8/8 | 0/1 | 0/4 | Negative | ||

| MMP9 positive | 8/8 | 0/1 | 0/4 | Negative | ||

| Diabetic nephropathy (n=12) | 22 (10–40) | |||||

| MMP2 positive | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | Negative | ||

| MMP9 positive | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | Negative | ||

| MCGN (n=7) | 20 (7) | |||||

| MMP2 positive | 6/6 | 0/0 | 0/0 | Negative | ||

| MMP9 positive | 6/6 | 0/0 | 0/0 | Negative |

Discussion

In this study, we hypothesised that MMP2 and MMP9 may be expressed during active LN. We tested the expression patterns of MMP2 and MMP9 in multiple classes of LN. In contrast to previous reports, we observed that MMP2 and MMP9 occur only in crescentic LN and not in mesangioproliferative or membranoproliferative types. Therefore, we hypothesized that MMP2/MMP9 expression is a feature of crescentic glomerulonephritis in general, and not solely LN. Indeed, both IgA nephropathy and PIGN with active cellular or fibrocellular crescents expressed MMP2 and MMP9. In fibrous, or resolved, crescentic lesions MMP2 and MMP9 were not detected in either LN or any other crescentic glomerulonephritis.

The absence of significant mesangial MMP2/MMP9 expression reflects the contradictory reports in the literature. Urushihara et al. [18] observed that in non-crescentic glomerulonephritis, when detected by immunoflourescence, MMP9 is found in the mesangium of biopsies with IgA nephropathy, Henoch-Schönlein Purupura and class-II SLE. MMP9 is also weakly present in the mesangium in diabetic nephropathy and MMP2 was not observed in any glomerulonephritis. Sanders et al. [24] looked at crescentic PIGN and similar to this study, MMP2/MMP9 was observed by immunohistochemistry and immunoflourescence in active crescentic lesions. MMP2 was not only observed in interstitial and glomerular cells, but also in the mesangium of control biopsies. More recently, there was variable expression of MMP2 and MMP9 reported in non-crescentic immuoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) and Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (HSP) [23]. Several plausible explanations for differences in expression are likely. All studies were single-centre investigations with differences in case definition and biopsy practice. Each study also utilized diverse methods of identifying MMP2/MMP9. All studies exploring MMP2/MMP9 in the presence of crescentic glomerulonephritis report strong expression in active crescents.

It remains unclear what purpose MMP2/MMP9 has in crescentic glomerulonephritis. Like gelatinases, MMP2/MMP9 is secreted by inflammatory leucocyte infiltrates after TLR stimulation and may contribute to degradation of the GBM. It is likely that expression of MMP2 or MMP9 is part of the pathophysiological process of extracapillary proliferation and there are two major possibilities to explain this involvement. First, MMP2/MMP9 may contribute to repair and remodelling of the glomerulus during extracapillary proliferation. Alternatively, it is possible that these enzymes are highly expressed in the cytoplasm of epithelial cells and the presence of epithelial proliferation explains the MMP2/MMP9 pattern. There are several aspects that would strengthen this study. This is a single-centre study and it would be desirable to have reproduction of these findings in other centres. Similarly, increasing the size of the cohort and extending to class-II LN and other crescentic glomerulonephritides would allow a more accurate estimate of the prevalence of MMP2/MMP9 in the different types of crescent and across different proliferative glomerulonephritic diseases. Further studies of ‘MMP2’ or ‘MMP9’ mouse models with induced glomerular injury would complement these observations and delineate their role in crescentic glomerulonephritis.

This study implicates MMP2 and MMP9 in the process of extracapillary proliferation in crescentic glomerulonephritis. This is not exclusive to LN, but rather to the process of crescent formation. Further study is necessary to define whether the expression of MMP2/MMP9 reflects a role in glomerular repair after injury, a role in regulating organ-level immune responses or a role as a marker of epithelialization.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available online at http://ckj.oxfordjournals.org.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Seligman VA, Lum RF, Olson JL. et al. Demographic differences in the development of lupus nephritis: a retrospective analysis. Am J Med 2002; 112: 726–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patel M, Clarke AM, Bruce IN. et al. The prevalence and incidence of biopsy-proven lupus nephritis in the UK: evidence of an ethnic gradient. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54: 2963–2969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Donadio JV Jr, Hart GM, Bergstralh EJ. et al. Prognostic determinants in lupus nephritis: a long-term clinicopathologic study. Lupus 1995; 4: 109–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alba P, Bento L, Cuadrado MJ. et al. Anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm antibodies, and the lupus anticoagulant: significant factors associated with lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62: 556–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sinico RA, Rimoldi L, Radice A. et al. Anti-C1q autoantibodies in lupus nephritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009; 1173: 47–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mason LJ, Ravirajan CT, Rahman A. et al. Is alpha-actinin a target for pathogenic anti-DNA antibodies in lupus nephritis? Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50: 866–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salmon JE, Millard S, Schachter LA. et al. Fc gamma RIIA alleles are heritable risk factors for lupus nephritis in African Americans. J Clin Invest 1996; 97: 1348–1354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weening JJ, D'Agati VD, Schwartz MM. et al. The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15: 241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lech M, Anders HJ.. The pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 24: 1357–1366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hill GS, Delahousse M, Nochy D. et al. Class IV-S versus class IV-G lupus nephritis: clinical and morphologic differences suggesting different pathogenesis. Kidney Int 2005; 68: 2288–2297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rahman AH, Eisenberg RA.. The role of toll-like receptors in systemic lupus erythematosus. Springer Semin Immunopathol 2006; 28: 131–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agarwal S, Misra R, Aggarwal A.. Induction of metalloproteinases expression by TLR ligands in human fibroblast like synoviocytes from juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients. Indian J Med Res 2010; 131: 771–779 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tveita AA, Rekvig OP, Zykova SN.. Increased glomerular matrix metalloproteinase activity in murine lupus nephritis. Kidney Int 2008; 74: 1150–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bethunaickan R, Berthier CC, Ramanujam M. et al. A unique hybrid renal mononuclear phagocyte activation phenotype in murine systemic lupus erythematosus nephritis. J Immunol 2011; 186: 4994–5003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benson HL, Mobashery S, Chang M. et al. Endogenous matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 regulate activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Am J Res Cell Mol Biol 2011; 44: 700–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cauwe B, Martens E, Sagaert X. et al. Deficiency of gelatinase B/MMP-9 aggravates lpr-induced lymphoproliferation and lupus-like systemic autoimmune disease. J Autoimmun 2011; 36: 239–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thiyagarajan D, Fismen S, Seredkina N. et al. Silencing of renal DNaseI in murine lupus nephritis imposes exposure of large chromatin fragments and activation of Toll like receptors and the Clec4e. PloS One 2012; 7: e34080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Urushihara M, Kagami S, Kuhara T. et al. Glomerular distribution and gelatinolytic activity of matrix metalloproteinases in human glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17: 1189–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Churg J, Bernstein J, Glassock RJ.. Renal disease: classification and atlas of glomerular diseases. 2nd edn New York, NY: Igaku-Shoin, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Briganti EM, Russ GR, McNeil JJ. et al. Risk of renal allograft loss from recurrent glomerulonephritis. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 103–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jegatheesan D, Nath K, Reyaldeen R. et al. Epidemiology of biopsy-proven glomerulonephritis in Queensland adults. Nephrology 2016; 21: 28–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS.. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus 2006; 15: 308–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Danilewicz M, Wagrowska-Danilewicz M.. Differential glomerular immunoexpression of matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 in idiopathic IgA nephropathy and Schoenlein-Henoch nephritis. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 2010; 48: 63–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sanders JS, van Goor H, Hanemaaijer R. et al. Renal expression of matrix metalloproteinases in human ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19: 1412–1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.