Abstract

Purpose

To determine the long-term prognosis in each phenotypic subset of breast cancer related to residual cancer burden (RCB) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone, or with concurrent human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–targeted treatment.

Methods

We conducted a pathologic review to measure the continuous RCB index (wherein pathologic complete response has RCB = 0; residual disease is categorized into three predefined classes of RCB index [RCB-I, RCB-II, and RCB-III]), and yp-stage of residual disease. Patients were prospectively observed for survival. Three patient cohorts received paclitaxel (T) followed by fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (T/FAC): original development cohort (T/FAC-1), validation cohort (T/FAC-2), and independent validation cohort (T/FAC-3). Another validation cohort received FAC chemotherapy only, and a fifth cohort received concurrent trastuzumab (H) with sequential paclitaxel and fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC; H+T/FEC). Phenotypic subsets were defined by hormone receptor (HR) and HER2 status at diagnosis, classified as HR-positive/HER2-negative, HER2-positive (HR-negative/HER2-positive or HR-positive/HER2-positive), or triple receptor–negative. Relapse-free survival estimates were determined from Kaplan-Meier analysis and compared using the log-rank test.

Results

Five cohorts (T/FAC-1 [n = 219], T/FAC-2 [n = 262], T/FAC-3 [n = 342], FAC [n = 132], and H+T/FEC [n = 203]) had median event-free follow-up of 13.5, 9.1, 6.8, 16.4, and 7.1 years, respectively. Continuous RCB index was prognostic within each phenotypic subset, independent of other clinical-pathologic variables. RCB classes stratified prognostic risk overall, within each phenotypic subset, and within yp-stage categories. Estimates of 10-year relapse-free survival rates in the four RCB classes (pathologic complete response, RCB-I, RCB-II, and RCB-III) were 86%, 81%, 55%, and 23% for triple receptor–negative; 83%, 97%, 74%, and 52% for HR-positive/HER2-negative in the combined T/FAC cohorts; and 95%, 77%, 47%, and 21% in the H+T/FEC cohort.

Conclusion

RCB was prognostic for long-term survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in all three phenotypic subsets of breast cancer. Our institutional findings should be externally validated.

INTRODUCTION

The US Food and Drug Administration’s mechanism for accelerated approval of chemotherapy treatments for high-risk, early breast cancer is on the basis of improved pathologic complete response (pCR) rate after neoadjuvant treatment in a randomized trial.1-3 But although this demonstrates confidence in the prognostic importance of pCR, it is still not clear what magnitude of prognostic difference could be expected from an improvement in pCR rate.4-6 Prognostic difference might also depend on the distribution of the extent of residual disease in each treatment arm, if that relates to longer-term prognosis within each phenotypic subset of breast cancer.

The two main measures of residual disease in a pathologic resection specimen are yp-stage (American Joint Commission on Cancer stage) and residual cancer burden (RCB). The RCB method uses the principles of pathologic sampling and reporting that are also necessary to accurately determine the presence and yp-stage of any residual disease after neoadjuvant treatment.7-9 Hence, it provides a standardized operating procedure for the prospective evaluation of postneoadjuvant specimens, requiring only standard pathology materials, minimal time from the pathologist, and no additional cost.2,7-9 A public Web site provides educational videos and materials for pathologists, including an online calculator for RCB index score and RCB class.7,10 The index score is derived from the largest area and cellularity of residual invasive primary cancer and the number of involved lymph nodes and size of largest metastasis.7 pCR (stage yp-T0/is, ypN0) has RCB = 0; and RCB class is minimal (RCB-I), moderate (RCB-II), or extensive (RCB-III), on the basis of predefined cut points of 1.36 and 3.28 index scores.7

In this study, we used five prospective breast cancer cohorts to test the long-term prognostic relevance of the measurement of RCB index and class after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, within each phenotypic subset of breast cancer.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a cohort study with prospective follow-up of patients to test the long-term prognostic performance of RCB after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (protocol MDACC-LAB98-240). RCB was determined by retrospective pathology review in three cohorts treated with neoadjuvant paclitaxel (T) followed by combined fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (T/FAC). T/FAC-1 was the original development cohort for RCB, treated during 1994 to 2002, pathology reviewed during 2003 to 2005, and prospectively observed for an additional 7 years.7 T/FAC-2 was a validation cohort for RCB, treated during 1999 to 2006, pathology reviewed during 2007 to 2009, and prospectively observed for an additional 5 years. T/FAC-3 was an independent validation cohort for RCB (enriched for residual disease), treated during 2005 to 2011, with independent pathology review during 2013 to 2015. The original RCB validation cohort was treated with FAC chemotherapy (without paclitaxel) during 1989 to 2001, pathology reviewed during 2005 to 2006, and prospectively observed for an additional 7 years.7 Finally, a fifth cohort had human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive cancer and received neoadjuvant trastuzumab (H) with sequential paclitaxel and fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (H+T/FEC), treated during 2002 to 2011 and pathology reviewed during 2012 to 2015. The prognostic value of RCB was assessed according to type of treatment, yp-stage, and phenotype of breast cancer (defined by hormone receptor [HR] and HER2 status), and adjusted for pretreatment clinical and pathologic characteristics (see Pathology Review and Clinical Review).

Eligibility

We excluded patients with any of the following: previous invasive breast cancer; surgical biopsy of the primary tumor or a positive lymph node before neoadjuvant treatment; treatment discontinuation before completion of at least 75% of the prescribed cycles of chemotherapy; inclusion of additional treatments; or adjuvant systemic therapy other than hormonal or HER2-targeted systemic therapy (Appendix Table A1).

Pathology Review

We used the published method to evaluate the pathology materials and the associated Web site to calculate RCB.7,10 Briefly, the gross description (including radiographs, diagrams, or photographs) and all corresponding slides underwent a retrospective review by a pathologist to determine the RCB index and class, and yp-stage. Patients with documented clinical progression or inoperability, precluding surgical resection upon completion of the prescribed neoadjuvant chemotherapy, were classified as RCB-III.7 HR status was defined as positive if ≥ 10% of tumor nuclei stained positively. HER2 status was defined as positive if the protein had a strong (3+) membrane staining pattern in ≥ 30% of tumor cells or gene amplification relative to a centromere probe by fluorescent in situ hybridization (ratio of ERBB2/cep17 > 2.2). Of note, HER2 status was not available for most of the patients in the older FAC cohort because HER2 testing was not clinically required during that time and pretreatment tumor blocks were not available for testing.

Clinical Review

Electronic medical records were reviewed to document each patient’s age, height and weight, diabetic status, clinical stage of breast cancer before treatment (c-stage), clinical and radiologic characteristics of the primary cancer, and follow-up for relapse or death. Diabetic status (yes or no) was classified as yes if a patient had a diagnosis of diabetes in the clinical record or received treatment for diabetes at any time from initial presentation until the completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The primary cancer was classified as multifocal at the time of initial diagnostic work-up if the radiologist or surgeon described two or more tumors separated by ≥ 1 cm of normal-appearing parenchyma. The data were stored in a secure database, de-identified, and exported for statistical analyses.

Statistical Methods

Survival end points of relapse-free survival (RFS), distant RFS, and overall survival were defined from the date of diagnosis using published standardized criteria.11 Survival probability within RCB class was determined using the Kaplan-Meier estimator, with 95% CIs estimated using the Greenwood formula with log-log transformation. Kaplan-Meier curves were truncated when the smallest subgroup had < 10% of patients remaining at risk.12 Survival times were compared among RCB classes using the log-rank test. Hazard ratios for RCB index were adjusted for age (continuous), c-stage (III v I to II), and nuclear grade (3 v 1 to 2) at initial diagnosis. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models for each phenotypic subtype included the same variables as well as pretreatment multifocal primary tumor (v solitary) and pCR (v residual disease). Model discrimination was evaluated on the basis of Harrell’s concordance index, or c-index.13 Comparison of RCB with yp-stage excluded patients where surgery was delayed or denied as a result of progression and/or additional treatments. Cohort T/FAC-3 was not included in the analyses of the proportion of RCB classes within phenotypic subsets (because the T/FAC-3 cohort was enriched for patients with residual disease), but it was included with the other T/FAC cohorts in the survival analyses.

RESULTS

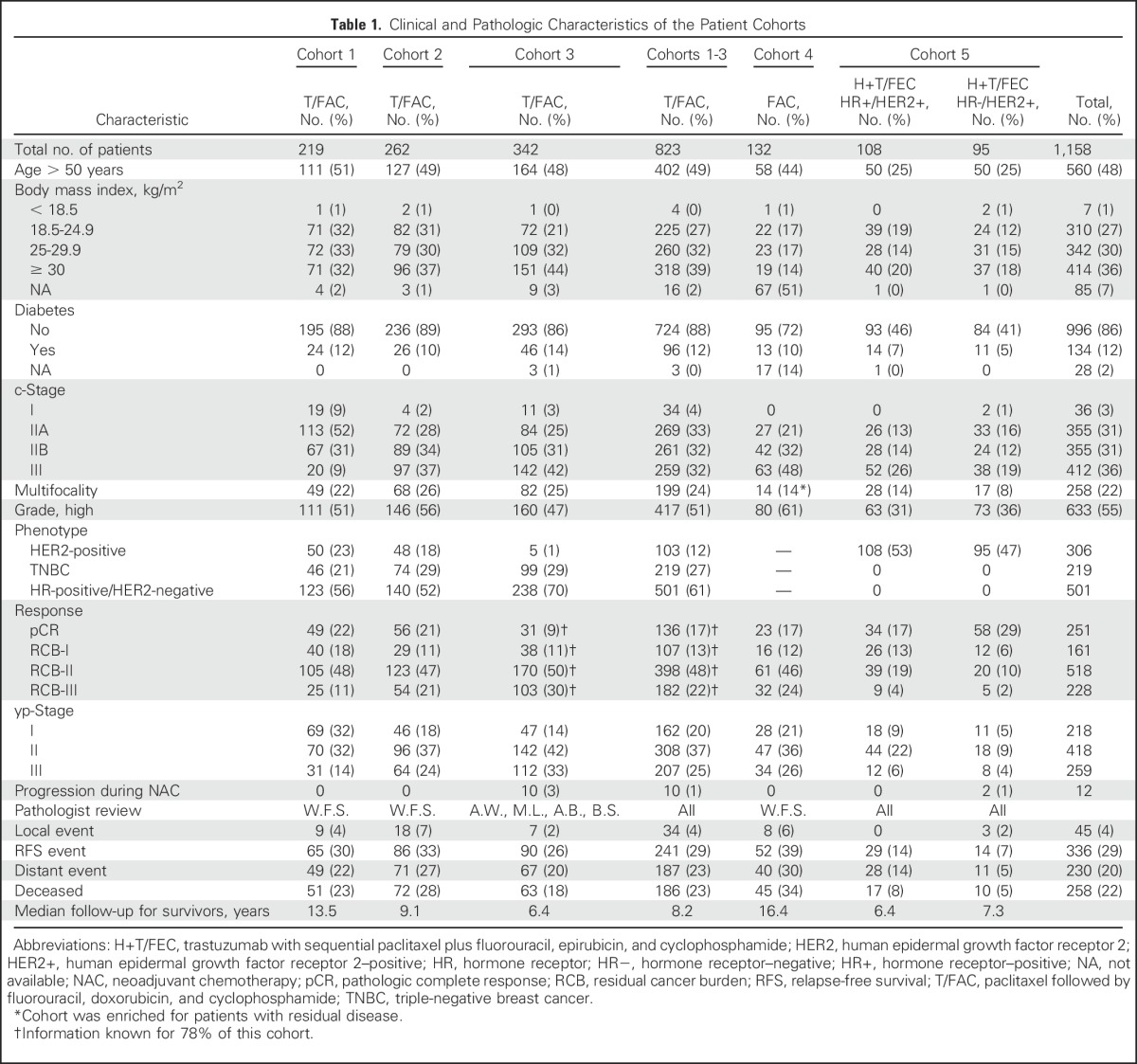

Pretreatment characteristics, response, and follow-up information are summarized for each treatment cohort in Table 1. Eligibility and reasons for exclusion are summarized in Appendix Table A1 (online only).

Table 1.

Clinical and Pathologic Characteristics of the Patient Cohorts

Long-Term Prognostic Performance of RCB

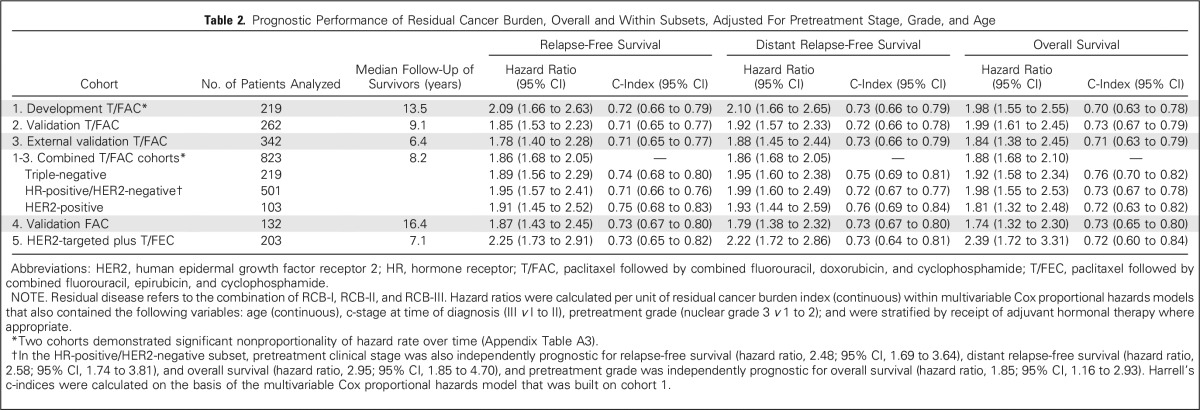

The continuous RCB index was associated with risk of relapse or death, and the hazard ratios per unit of RCB index were significant in all five cohorts, adjusted for age at diagnosis, c-stage, and tumor grade (Table 2). Body mass index and diabetic status were not prognostic in any cohort; thus these factors were excluded from multivariable models.

Table 2.

Prognostic Performance of Residual Cancer Burden, Overall and Within Subsets, Adjusted For Pretreatment Stage, Grade, and Age

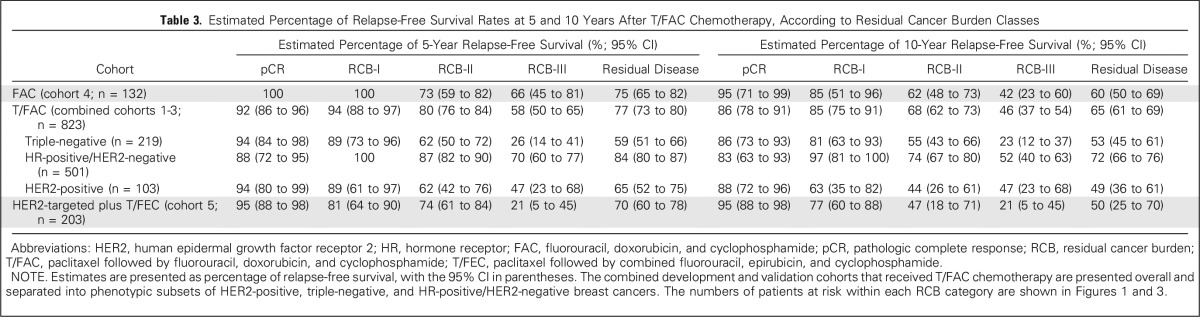

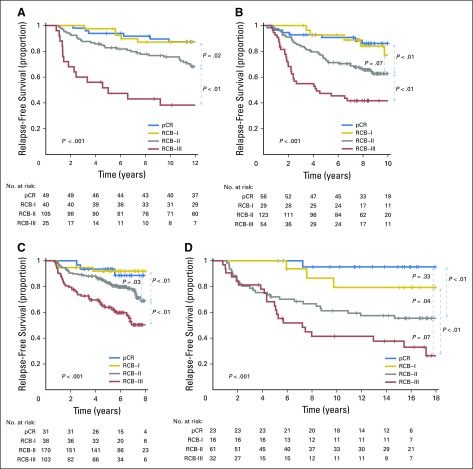

The predefined RCB classes were prognostic for RFS in all five cohorts (Table 3). Although the RCB index was originally developed from cohort T/FAC-1,7 we observed similar long-term prognostic results with other cohorts (Appendix Fig A1 and Appendix Table A2 [online only]), without significant difference between the T/FAC cohorts in a multivariable Cox regression model with RCB index (hazard ratio, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.76 to 2.21), HR status (hazard ratio, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.45), and HER2 status (not significant).

Table 3.

Estimated Percentage of Relapse-Free Survival Rates at 5 and 10 Years After T/FAC Chemotherapy, According to Residual Cancer Burden Classes

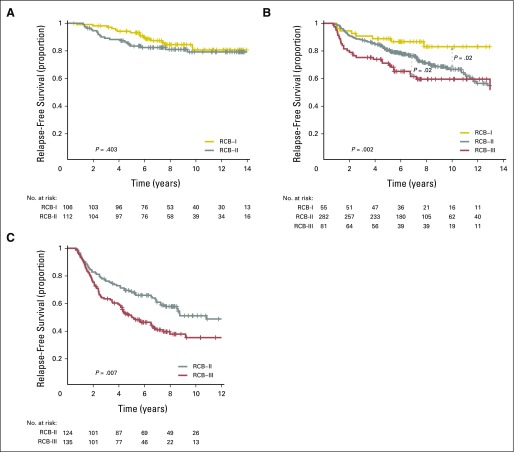

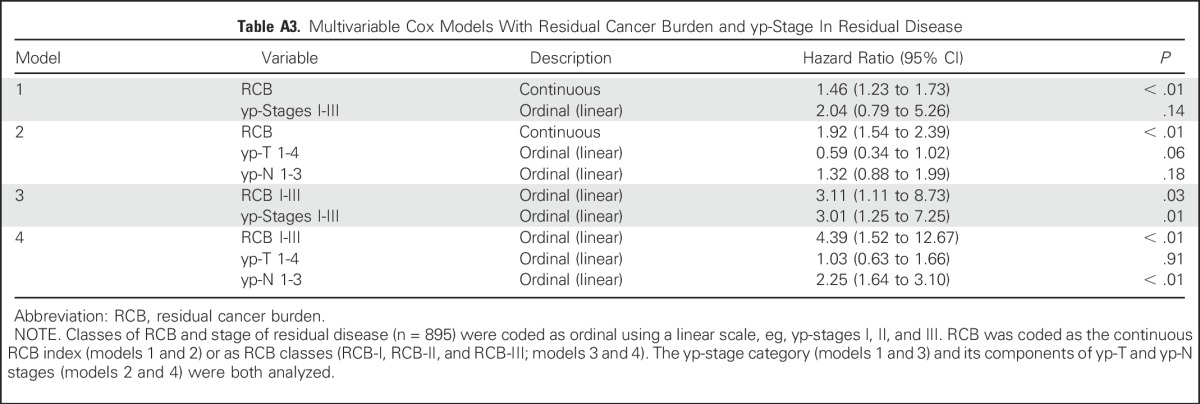

RCB classes were prognostic within yp-stage II and yp-stage III, but not significantly different in yp-stage I (Fig 1). RCB index and class added independent prognostic information to yp-stage within multivariable models, and yp-N stage was independently prognostic with RCB class (Appendix Table A3, online only). Also, rare relapses after pCR had no obvious association with surgical procedure, specimen radiography, or tumor phenotype (Appendix Fig A4, online only).

Fig 1.

Kaplan-Meier plots of relapse-free survival for residual cancer burden (RCB) categories within the yp-stage categories from pooled analysis of the patients with residual disease from the five cohorts (N = 895): (A) yp-stage I (n = 218); (B) yp-stage II (n = 418); and (C) yp-stage III (n = 259). This analysis excluded 12 patients who did not undergo surgery immediately after neoadjuvant treatment (as a result of progression). Note that the original development cohort (cohort 1, Table 1) was included in these analyses. The length of each x-axis is proportional to the duration of follow-up of survivors, truncated when < 10% of the smallest group remained at risk. Response categories are shown as RCB-I (gold), RCB-II (gray), and RCB-III (red).

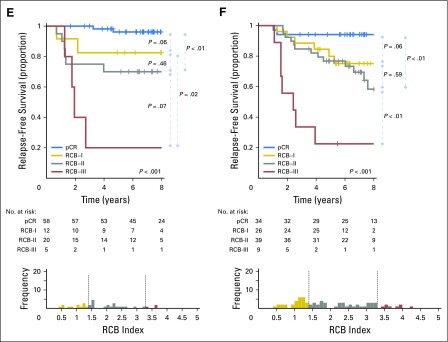

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: T/FAC Chemotherapy

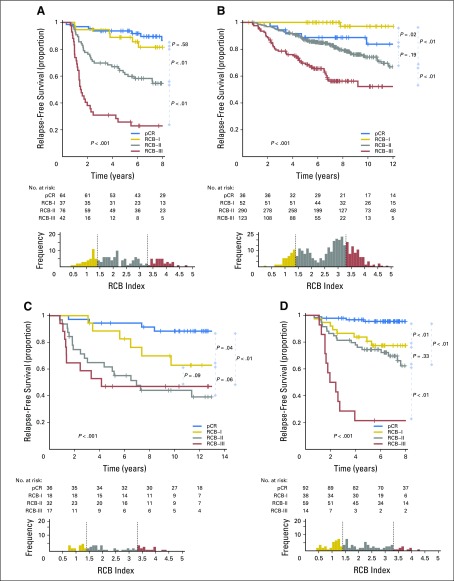

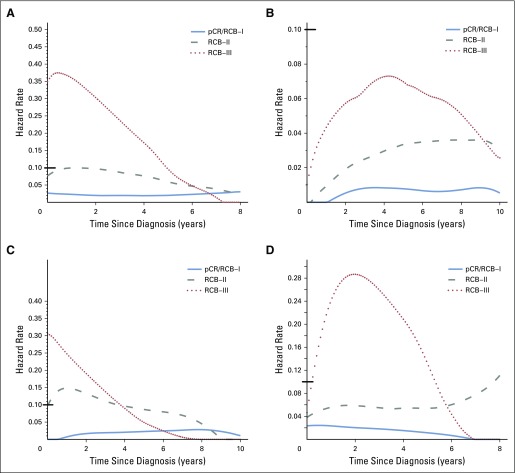

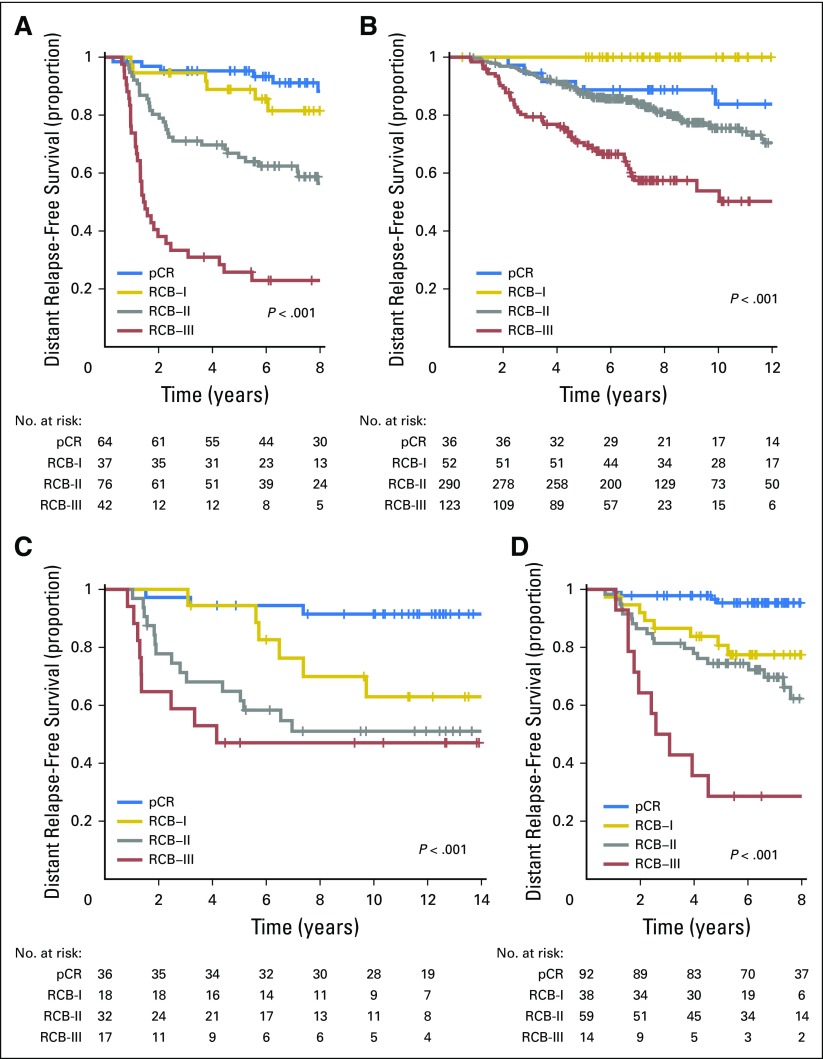

The proportion of patients within each RCB class was as follows: 35% pCR, 15% RCB-I, 33% RCB-II, and 17% RCB-III. Good prognoses were observed for patients who achieved pCR (estimated RFS of 94% at 5 years and 86% at 10 years) or RCB-I (estimated RFS of 89% at 5 years and 81% at 10 years; Table 3 and Fig 2A [online only]). Prognoses were inferior for patients with RCB-II (estimated RFS of 62% at 5 years and 55% at 10 years) or RCB-III (estimated RFS of 26% at 5 years and 23% at 10 years). Prognoses were similar for both distant RFS and overall survival (Appendix Figs A2A-A3A [online only]). A kernel-based hazard function plot showed residual risk that ended before 7 years (Fig 3A).14 In a multivariable model for RFS, only RCB index was independently prognostic (hazard ratio, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.49 to 2.46), whereas age, c-stage, grade, multifocality, and pCR were not.

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots of relapse-free survival according to residual cancer burden (RCB) categories for phenotypic subsets of breast cancer: (A) triple-negative (n = 219); (B) HR-positive/HER2-negative (n = 501); (C) HER2-positive (n = 103) after paclitaxel (T) followed by fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (T/FAC) chemotherapy; (D) all HER2-positive (n = 203); (E) HR-negative/HER2-positive subset (n = 95); and (F) HR-positive/HER2-positive subset (n = 108) after HER2-targeted therapy with trastuzumab (H) and sequential paclitaxel followed by fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy (H+T/FEC). Patients in the HER2-positive T/FAC cohort (C) did not receive any HER2-targeted therapy (trastuzumab) as neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment. On the other hand, all patients in the H+T/FEC cohort (D to F) received neoadjuvant and adjuvant HER2-targeted therapy (trastuzumab). Note that the original development cohort (cohort 1, Table 1) was included in the analysis for plots A to C. The length of each x-axis is proportional to the duration of follow-up of survivors, truncated when < 10% of the smallest group remained at risk. Below each survival plot is a corresponding histogram to show the relative frequency distribution of RCB index. Response categories are shown as pathologic complete response (pCR; blue), RCB-I (gold), RCB-II (gray), and RCB-III (red). HR, hormone receptors; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Fig 3.

Hazard function plots illustrating the estimated rate of relapse-free survival events at each time of follow-up (rate per patient per year). (A) Triple-negative, (B) HR-positive/HER2-negative, (C) HER2-positive breast cancer treated with paclitaxel followed by fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (T/FAC) chemotherapy, and (D) HER2-positive breast cancer treated with HER2-targeted therapy (trastuzumab) and sequential paclitaxel followed by fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (H+T/FEC) chemotherapy. Response categories are shown as pathologic complete response (pCR) or residual cancer burden (RCB)-I (blue), RCB-II (gray), and RCB-III (red). Y-axes use different scales; therefore, a black bar at hazard rate 0.10 was placed for reference. HR, hormone receptors; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

HR-Positive/HER2-Negative Breast Cancer: T/FAC Chemotherapy

The proportion of patients within each RCB class was as follows: 10% pCR, 13% RCB-I, 60% RCB-II, and 17% RCB-III. There were good prognoses for patients who achieved pCR (estimated RFS of 88% at 5 years and 83% at 10 years) or RCB-I (estimated RFS of 100% at 5 years and 97% at 10 years; Fig 2B and Table 3). Patients with RCB-II had estimated RFS of 87% at 5 years and 74% at 10 years (Table 3). However, extensive residual disease (RCB-III) imparted significantly worse prognoses, with estimated RFS of 70% at 5 years and 52% at 10 years (Fig 2B and Table 3). Prognoses were similar for both distant RFS and overall survival (Appendix Figs A2B-A3B). A hazard function plot for RCB classes showed extended residual risk over a decade (Fig 3B).14 In the multivariable model for RFS, RCB index (hazard ratio, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.76 to 2.96), pretreatment clinical stage III (hazard ratio, 2.51; 95% CI, 1.71 to 3.69), and (paradoxically) pCR (hazard ratio, 5.03; 95% CI, 1.60 to 15.78) were independently prognostic, whereas age, grade, and multifocality were not.

The distribution of RCB index was bimodal in HR-positive/HER2-negative cancers, with nadir at 2.25 (Fig 2B). This bimodality did represent residual nodal status (Appendix Fig A5C, online only), but RCB class remained prognostic in ypN-positive disease (Appendix Fig A6A, online only). Also, the nadir at RCB index of 2.25, although significant, was not a clinically meaningful prognostic cut point for patients with RCB-II (Appendix Fig A6B).

HER2-Positive Breast Cancer: T/FAC Chemotherapy Alone

The proportion of patients within each RCB class was as follows: 37% pCR, 17% RCB-I, 31% RCB-II, and 15% RCB-III. The observed prognoses for RCB-I (estimated RFS of 89% at 5 years and 63% at 10 years) were significantly different from pCR (estimated RFS of 94% at 5 years and 88% at 10 years; Table 3 and Fig 2C). The long-term prognoses for RCB-II (estimated RFS of 62% at 5 years and 44% at 10 years) and RCB-III (estimated RFS of 47% at 5 years and at 10 years) seemed to be similar. Prognoses were similar for both distant RFS and overall survival (Appendix Figs A2C-A3C). In the multivariable model for RFS (stratified by use of hormonal therapy), nuclear grade 3 (hazard ratio, 2.67; 95% CI, 1.17 to 6.11), pCR (hazard ratio, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06 to 0.90), and multifocality (hazard ratio, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.00 to 4.11) were independently significant variables, whereas age, c-stage, and RCB index were not.

HER2-Positive Breast Cancer: T/FEC Chemotherapy With Trastuzumab

The proportion of patients within each RCB class was as follows: 45% pCR, 19% RCB-I, 29% RCB-II, and 7% RCB-III. RCB classes were prognostic (Fig 2D), even within the subsets of HR-negative/HER2-positive (Fig 2E) and HR-positive/HER2-positive (Fig 2F). Overall, patients who achieved pCR had excellent long-term prognoses (estimated RFS of 95% at 5 years and at 10 years), significantly better than other RCB classes (Table 3 and Fig 2D). The prognoses for RCB-I (estimated RFS of 81% at 5 years and 77% at 10 years) and RCB-II (estimated RFS of 74% at 5 years and 47% at 10 years) seemed to be similar. Few patients had RCB-III, with significant risk of early relapse (estimated RFS of 21% at 5 years and at 10 years). Prognoses were similar for both distant RFS and overall survival (Appendix Figs A2D-A3D). In the multivariable model for RFS (stratified by use of hormonal therapy), only RCB index was independently prognostic (hazard ratio, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.26 to 2.59), whereas age, c-stage, grade, multifocality, and pCR were not. The subsets of RCB class within HR-positive/HER2-positive or HR-negative/HER2-positive subsets were too small to present 5-year and 10-year estimates of RFS.

DISCUSSION

RCB index and classes were prognostic in all treatment cohorts and phenotypic subsets. In high-risk phenotypes of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC; treated with T/FAC) and HER2-positive disease (treated with H+T/FEC), RCB index was the only prognostic variable in multivariable models that included age, pretreatment c-stage, grade, multifocality, and pCR. In the HR-positive/HER2-negative phenotype, RCB index and pretreatment c-stage were both independently prognostic.

RCB and yp-stage both summarize the extent of residual disease in the breast and regional lymph nodes, but define size differently. RCB index and class of residual disease were independently prognostic in multivariable analyses with yp-stage, yp-T, and yp-N; and yp-stage and yp-N remained prognostic with RCB class (Appendix Table A3). RCB classes refined the prognostic utility of yp-stage II and yp-stage III, adding information to this standard assessment (Fig 1), and suggesting that both RCB and yp-stage (yp-T and yp-N) should be recorded with residual disease.

The main limitations of this study can be summarized as follows: generalizability of our results from a single institutional experience, or from our inclusion of the original RCB development cohort (T/FAC-1)7 in the overall analysis of phenotypic subsets; lack of comparability between RCB and systems that add pretreatment information (eg, Neo-Bioscore); and insufficient sample size to detect modest differences in prognosis between classes of RCB within each phenotypic subset, or within low-risk subsets (eg, within yp-stage I or comparing pCR with RCB-I).

Two groups have reported strong concordance of RCB index measurements and related prognoses between different pathologists who independently learned this method from published and Web-based teaching materials,15,16 and independent pathologists evaluated the T/FAC-3 cohort in this study. Also, the long-term prognostic performance of RCB was similar in all treatment cohorts (Appendix Figs A1-A3) without statistical difference attributable to the original development cohort (T/FAC-1).7 Others have reported that RCB was prognostic in their hands.17-20 Thus RCB methodology seems to be reproducible and generalizable, according to institutional cohort studies, although results from multicenter trials are still pending. Note that educational videos on the RCB Web site illustrate how the method can standardize and focus the specimen evaluation, decrease the number of tissue blocks, and support efficient correlation of macroscopic and microscopic findings, and accurate assessment of pCR versus residual disease, RCB, and yp-stage.2,8,9

RCB does not incorporate additional pretreatment information, unlike the CPS+EG system (c-stage and yp-stage, estrogen receptor, and histologic grade). Also, Neo-Bioscore is a modification of CPS+EG (to add HER2 status)21 that is generally prognostic in breast cancer,22 and could augment yp-stage as a prognostic tool for breast cancer in general and in the HR-positive/HER2-negative subset.23 However, RCB was prognostic within each phenotypic subset, wherein different treatments are becoming the norm. Indeed, future improvements to RCB could be phenotype specific, including rebalanced RCB index and cut points, and judicious combination with pretreatment and biomarker information.19

In TNBC, response to adjuvant chemotherapy was the most important determinant of survival. Approximately half of the TNBC population achieved pCR or RCB-I, with good prognoses, although this study lacks statistical power to determine whether the prognosis of RCB-I is similar to pCR. On the other hand, prognoses were inferior for RCB-II and RCB-III (Fig 2A).

In HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer, pathologic response to chemotherapy (RCB index) was prognostic, seemingly similar to other phenotypic subtypes (Table 2). So although dichotomous distinction between pCR and residual disease seems to be a suboptimal prognostic surrogate for HR-positive/HER2-negative cancers,1,24 the extent of RCB was significantly prognostic (Fig 2B). Furthermore, the residual hazard for patients with RCB-II and RCB-III was still elevated a decade later (Fig 3B); thus insufficient chemotherapy response might have long-term prognostic consequences for these patients (despite adjuvant endocrine therapy).

The group with RCB-II poses an important challenge for improved prognostic stratification, because they comprised approximately 60% of HR-positive/HER2-negative cancers and had estimated RFS of 74% at 10 years (Table 3). Residual HR-positive/HER2-negative disease had a bimodal distribution of RCB (Fig 2B), strongly influenced by yp-N status (Appendix Fig A5C). Nevertheless, RCB was prognostic if node positive (yp-N > 0; Appendix Fig A6A). But although the threshold of 2.25 was also prognostic in patients with RCB-II, this difference was not clinically meaningful (Appendix Fig A6B).

More effective chemotherapy treatment can improve survival in HR-positive/HER2-negative disease, even when the rate of pCR is unchanged.25,26 Also, a lesser burden of residual disease seems to synergize with likely benefit from adjuvant endocrine therapy.27 Thus the distribution of RCB index might be informative within randomized clinical trials. Nevertheless, for patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative disease and RCB-II, there seems to be a complex prognostic relationship involving (at least) the disease burden at diagnosis, innate biology, sensitivity to chemotherapy, and sensitivity to adjuvant endocrine therapy.19 Understanding this complexity could lead to cures for more patients who present with c-stages II to III disease.

In HER2-positive disease, RCB index was prognostic after chemotherapy alone, and when combined with trastuzumab. There was outstanding 10-year prognosis for pCR in the H+T/FEC cohort, raising speculation of outright cure from the sequence of trastuzumab with chemotherapy, postoperative trastuzumab, and possibly immunologic surveillance. This supports pCR as an important surrogate end point for chemotherapy trials in HER2-positive cancer, even though our result in HR-positive/HER2-positive cancer differs from a previous report.24 RCB-I in HR-positive/HER2-positive cancers had prognoses that seemed to be inferior to pCR and similar to RCB-II, but sample size was limited.28 In HR-negative/HER2-positive cancer, there were too few patients with RCB-I or RCB-II to interpret, but we anticipate that larger clinical trials will provide further insight.

Pathologic response in lymph nodes is strongly prognostic,29 supporting use of sentinel lymph-node biopsy (SLNB) after neoadjuvant treatment. We excluded patients with excision of a positive node before treatment, and SLNB after treatment was performed if cN-negative, versus axillary dissection if cN-positive (ultrasound and/or biopsy), before treatment. In the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z1071 trial, the false-negative rate of post-treatment SLNB was 12.6% in patients with documented nodal metastasis before treatment.30 But additional radiologic localization of proven nodal metastasis improves targeting, with a reported false-negative rate < 2%, to enable accurate assessment of RCB and yp-N stage.30,31

Overall, findings from our retrospective institutional cohorts support the notion that pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy is prognostic in all phenotypic subsets of breast cancer. Evaluation of RCB index and class could be useful because it appears to provide relevant, long-term prognostic data, which add meaningful information to pretreatment clinical and pathologic information and post-treatment yp-stage. Our findings should be externally validated.

Appendix

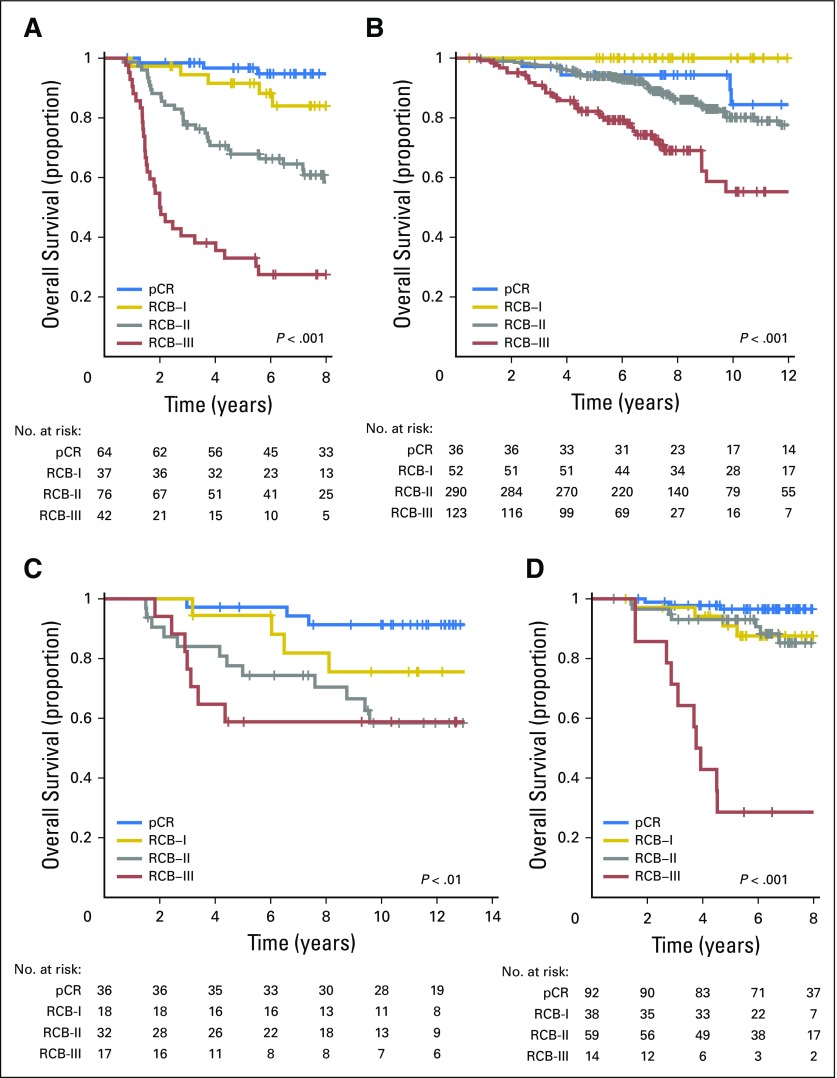

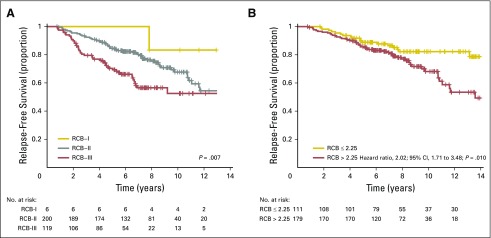

Fig A1.

Kaplan-Meier plots of relapse-free survival for residual cancer burden (RCB) categories in four cohorts who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy: (A) paclitaxel (T) followed by fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (T/FAC) treatment in the original development cohort for RCB7 (T/FAC cohort 1, n = 219); (B) T/FAC cohort 2 (validation cohort; n = 262); (C) T/FAC cohort 3 (independent validation cohort [other pathologists]; n = 342); and (D) fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FAC) treatment in the originally published validation cohort (n = 124). Note that the original development cohort (cohort 1, Table 1) was included in these analyses. Response categories are shown as pathologic complete response (pCR; blue), RCB-I (gold), RCB-II (gray), and RCB-III (red). The length of each x-axis is proportional to the duration of follow-up of survivors, truncated when < 10% of the smallest group remained at risk.

Fig A2.

Distant relapse-free survival according to residual cancer burden (RCB) categories for phenotypic subsets of breast cancer after paclitaxel (T) followed by fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (T/FAC) chemotherapy: (A) triple-negative breast cancer; (B) HR-positive/HER2-negative; (C) HER2-positive breast cancer treated with T/FAC chemotherapy; and (D) HER2-positive breast cancer treated with HER2-targeted therapy (trastuzumab) plus sequential paclitaxel and fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (T/FEC) chemotherapy. Note that the original development cohort (cohort 1, Table 1) was included in these analyses. Response categories are shown as pathologic complete response (pCR; blue), RCB-I (gold), RCB-II (gray), and RCB-III (red). The length of each x-axis is proportional to the duration of follow-up of survivors, truncated when < 10% of the smallest group remained at risk. HR, hormone receptors; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Fig A3.

Overall survival according to residual cancer burden (RCB) categories for phenotypic subsets of breast cancer after paclitaxel (T) followed by fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (T/FAC) chemotherapy: (A) triple-negative breast cancer; (B) HR-positive/HER2-negative; (C) HER2-positive breast cancer treated with T/FAC chemotherapy; and (D) HER2-positive breast cancer treated with HER2-targeted therapy (trastuzumab) plus sequential paclitaxel and fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (T/FEC) chemotherapy. Note that the original development cohort (cohort 1, Table 1) was included in these analyses. Response categories are shown as pathologic complete response (pCR; blue), RCB-I (gold), RCB-II (gray), and RCB-III (red). The length of each x-axis is proportional to the duration of follow-up of survivors, truncated when < 10% of the smallest group remained at risk. HR, hormone receptors; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

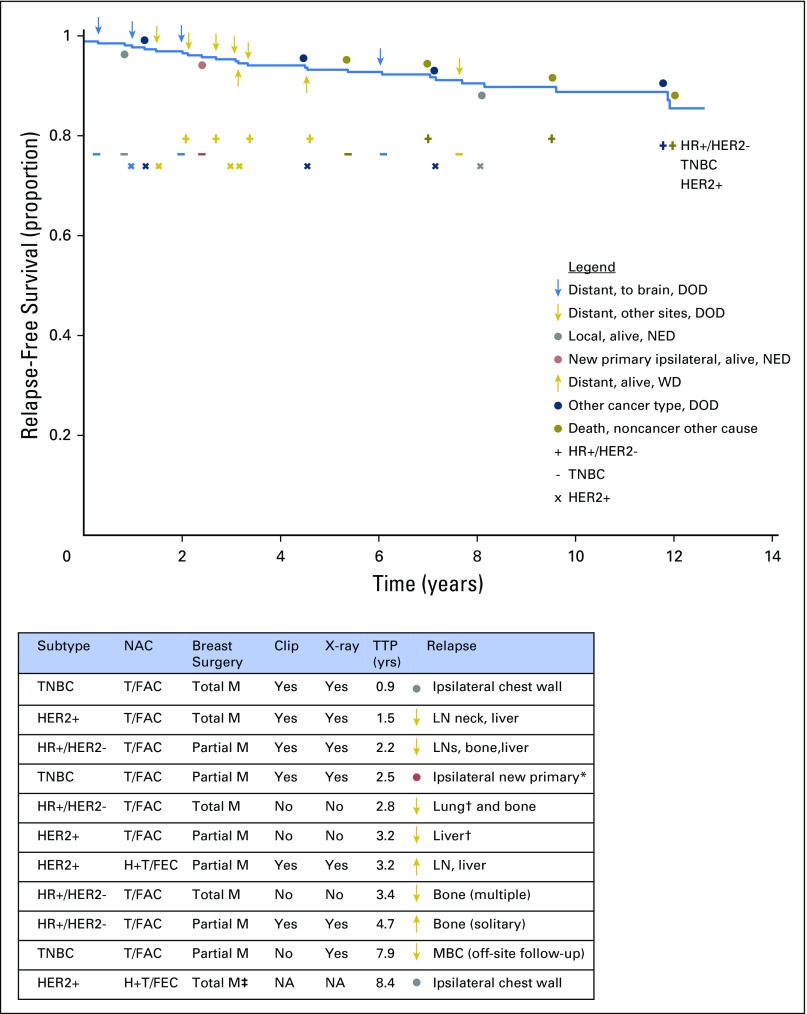

Fig A4.

Relapse-free survival for patients who achieved pathologic complete response from any neoadjuvant treatment (across all five cohorts) to illustrate whether the first relapse was distant to the brain (blue arrow) or other site (gold arrow), local relapse (gray circle), new primary (red circle), the result of a second type of cancer (blue circle), or death unrelated to cancer (dark gold circle). Symbols above the survival curve indicate events in patients who died. Symbols below the survival curve indicate events that did not lead to death during subsequent follow-up. Four relapse events were to the brain (a chemotherapy sanctuary site that is not surveyed during staging work-up) and were from triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC; 3 events) or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive (HER2+) cancer after paclitaxel (T) followed by fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (T/FAC) chemotherapy. The table lists the subtype of cancer and the surgical and pathology methods for the patients whose subsequent relapse could potentially relate to the adequacy of pathologic evaluation. There is no clear pattern among those who relapsed and whether pathologic sampling was from a total or partial mastectomy or absence of a metal clip that was radiographed in the specimen to identify the primary tumor bed. DOD, dead of disease; HER2−, HER2-negative; HR+, hormone receptor–positive; H+T/FEC, trastuzumab plus sequential paclitaxel and fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide; ipsilat, ipsilateral; LN, lymph node; M, mastectomy; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; NA, information not available; NED, no evidence of disease; TTP, time to progression; WD, with disease. (*) Adjacent to scar from previous partial mastectomy; (†) a pretreatment computed tomography scan showed an indeterminate abnormality not conclusive for malignancy; (‡) surgery was performed in another center and details from surgical pathology were not available from the health record.

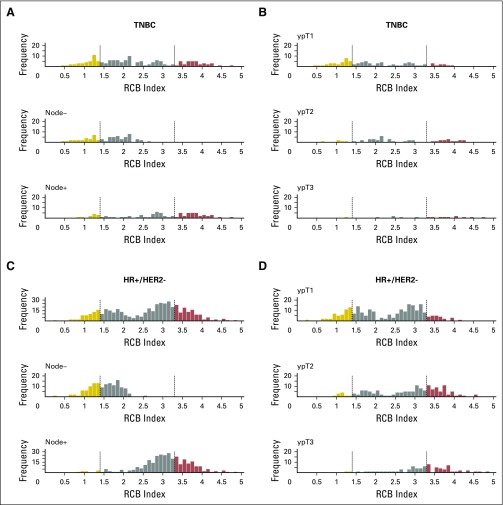

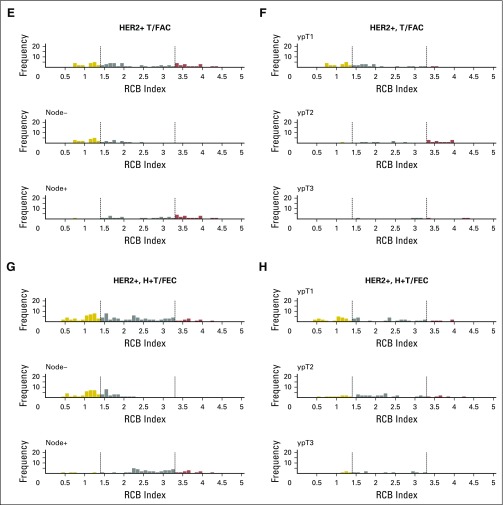

Fig A5.

Histograms of the distribution of residual cancer burden (RCB) index in the patients who had residual disease (not pathologic complete response) at surgery immediately following neoadjuvant taxane-anthracycline chemotherapy (excluding those patients whose disease progressed), according to phenotype of disease defined as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC; A and B), HR-positive/HER2-negative (HR+/HER2-; C and D), or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive (HER2+) who did not (E and F) or did (G and H) also receive neoadjuvant trastuzumab. Panels A, C, E, and G show the distributions of RCB in all patients and in the subsets with pathologic node–negative (ypN−) or pathologic node–positive (ypN+) status. Panels B, D, F, and H show the distributions of RCB in patients defined by pathologic tumor stage (ypT1, ypT2, ypT3). H+T/FEC, trastuzumab plus sequential paclitaxel and fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide; T/FAC, paclitaxel followed by fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide. HR, hormone receptors; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Fig A6.

Relapse-free survival for the subsets of patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative cancer according to residual cancer burden (RCB) after neoadjuvant paclitaxel (T) followed by fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (T/FAC) chemotherapy: (A) comparison of RCB classes in patients who had at least one involved regional lymph node (ypN ≥ 1); and (B) comparison of RCB index value > 2.25 versus ≤ 2.25 (the trough in the bimodal distribution of RCB in Figure 2B) only in those patients who had RCB-II. HR, hormone receptors; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

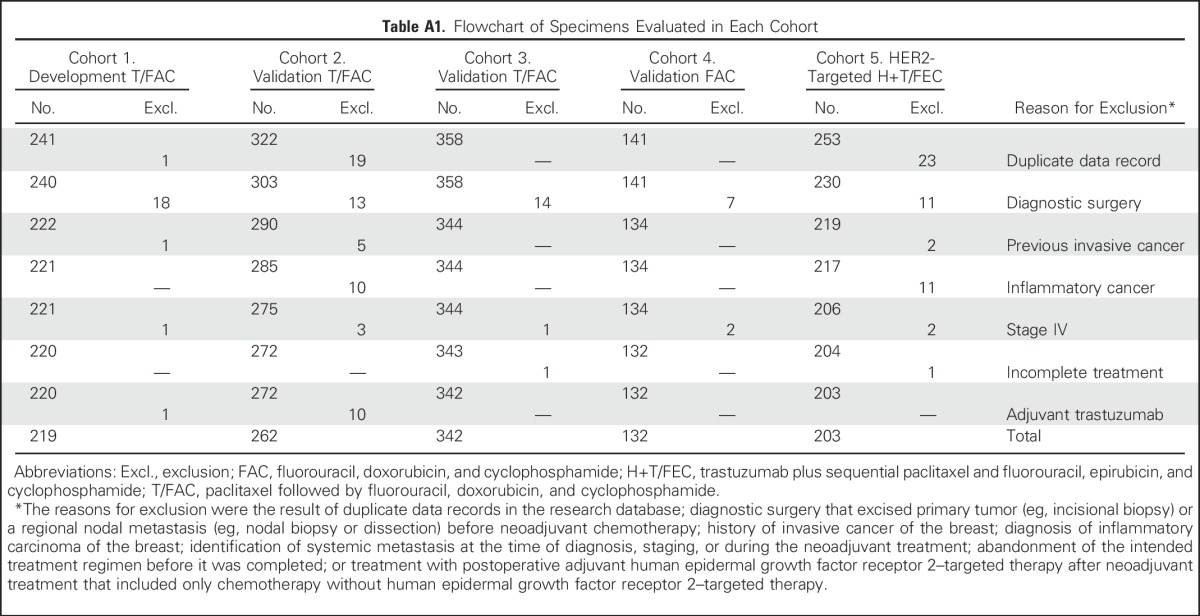

Table A1.

Flowchart of Specimens Evaluated in Each Cohort

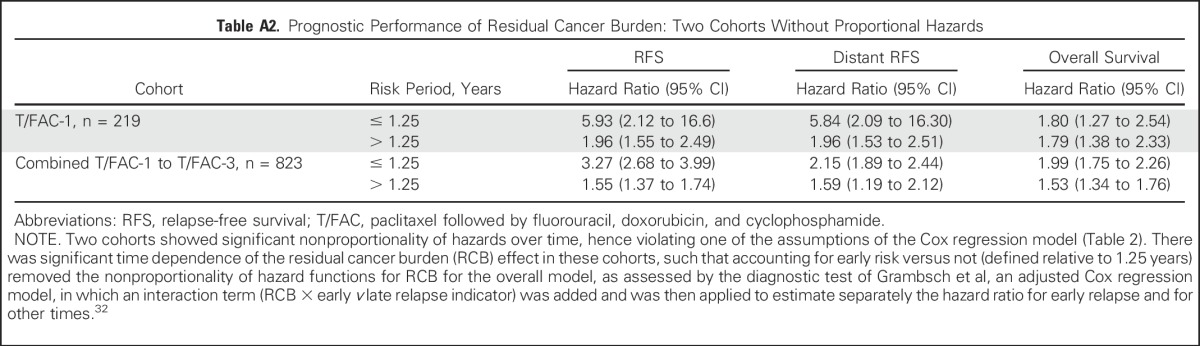

Table A2.

Prognostic Performance of Residual Cancer Burden: Two Cohorts Without Proportional Hazards

Table A3.

Multivariable Cox Models With Residual Cancer Burden and yp-Stage In Residual Disease

Footnotes

Supported in part by The Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Funds for Breast Cancer Research (W.F.S.), The Breast Cancer Research Foundation (W.F.S.), Susan G. Komen for The Cure (W.F.S.), and the Nellie B. Connally Breast Center at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

See accompanying Editorial on page 1029

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: W. Fraser Symmans, Christos Hatzis

Financial support: W. Fraser Symmans

Administrative support: W. Fraser Symmans, Gabriel N. Hortobagyi

Provision of study materials or patients: W. Fraser Symmans, Rebekah Gould, Kelly Hunt, Thomas A. Buchholz, Vicente Valero, Aman U. Buzdar, Wei Yang, Abenaa M. Brewster, Stacy Moulder, Lajos Pusztai, Gabriel N. Hortobagyi

Collection and assembly of data: W. Fraser Symmans, Rebekah Gould, Ya Zhang, Mei Liu, Andrew Walls, Alex Bousamra, Maheshwari Ramineni, Bruno Sinn, Kelly Hunt, Thomas A. Buchholz, Vicente Valero, Aman U. Buzdar, Wei Yang, Abenaa M. Brewster, Stacy Moulder, Lajos Pusztai, Gabriel N. Hortobagyi

Data analysis and interpretation: W. Fraser Symmans, Caimiao Wei, Xian Yu, Christos Hatzis

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Long-Term Prognostic Risk After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Associated With Residual Cancer Burden and Breast Cancer Subtype

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

W. Fraser Symmans

Stock or Other Ownership: ISIS Pharmaceuticals, Nuvera Biosciences

Honoraria: Australasian Society for Breast Disease, Affymetrix, Celgene

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent co-inventor. Patent rights are co-owned by Nuvera Biosciences and University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Inst).

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AbbVie

Caimiao Wei

No relationship to disclose

Rebekah Gould

No relationship to disclose

Xian Yu

No relationship to disclose

Ya Zhang

No relationship to disclose

Mei Liu

No relationship to disclose

Andrew Walls

No relationship to disclose

Alex Bousamra

No relationship to disclose

Maheshwari Ramineni

No relationship to disclose

Bruno Sinn

No relationship to disclose

Kelly Hunt

Research Funding: Endomagnetics (Inst)

Thomas A. Buchholz

No relationship to disclose

Vicente Valero

No relationship to disclose

Aman U. Buzdar

No relationship to disclose

Wei Yang

Consulting or Advisory Role: GE Healthcare, Seno Medical Instruments

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Royalty from textbook published by Elsevier

Abenaa M. Brewster

No relationship to disclose

Stacy Moulder

Research Funding: Oncothyreon (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Bayer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Novartis

Lajos Pusztai

Honoraria: BioTheranostics, Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Clovis Oncology, Celgene

Research Funding: Foundation Medicine, Merck, Genentech

Christos Hatzis

Stock or Other Ownership: Nuvera Biosciences

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent co-inventor. Patent rights are co-owned by Nuvera Biosciences and University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Inst).

Gabriel N. Hortobagyi

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Novartis, Peregrine Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Metastat, Merck, Eli Lilly, Celgene, F. Hoffman-La Roche, Ltd. (Roche), Agendia

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Novartis

REFERENCES

- 1.Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M, et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: The CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet. 2014;384:164–172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Food and Drug Administration, HHS Pathologic complete response in neoadjuvant treatment of high-risk early-stage breast cancer: Use as an endpoint to support accelerated approval; guidance for industry; availability. Fed Regist. 2014;79:60476–60477. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gianni L, Eiermann W, Semiglazov V, et al. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant trastuzumab in patients with HER2-positive locally advanced breast cancer (NOAH): Follow-up of a randomised controlled superiority trial with a parallel HER2-negative cohort. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:640–647. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry DA, Hudis CA. Neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancer as a basis for drug approval. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:875–876. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatzis C, Symmans WF, Zhang Y, et al. Relationship between complete pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and survival in triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:26–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeMichele A, Yee D, Paoloni M, et al. Neoadjuvant as future for drug development in breast cancer—Response. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:269. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Symmans WF, Peintinger F, Hatzis C, et al. Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4414–4422. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bossuyt V, Provenzano E, Symmans WF, et al. Recommendations for standardized pathological characterization of residual disease for neoadjuvant clinical trials of breast cancer by the BIG-NABCG collaboration. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1280–1291. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Provenzano E, Bossuyt V, Viale G, et al. Standardization of pathologic evaluation and reporting of postneoadjuvant specimens in clinical trials of breast cancer: Recommendations from an international working group. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:1185–1201. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2015.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The University of Texas, MD Anderson Cancer Center Residual Cancer Burden Calculator. www.mdanderson.org/breastcancer_RCB

- 11.Hudis CA, Barlow WE, Costantino JP, et al. Proposal for standardized definitions for efficacy end points in adjuvant breast cancer trials: The STEEP system. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2127–2132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pocock SJ, Clayton TC, Altman DG. Survival plots of time-to-event outcomes in clinical trials: Good practice and pitfalls. Lancet. 2002;359:1686–1689. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08594-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrell FE., Jr . Regression modelling strategies: With applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hess KR, Levin VA. Getting more out of survival data by using the hazard function. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1404–1409. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peintinger F, Sinn B, Hatzis C, et al. Reproducibility of residual cancer burden for prognostic assessment of breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:913–920. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2015.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naidoo K, Parham DM, Pinder SE: An audit of residual cancer burden reproducibility in a UK context. Histopathology 70:217-222, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corben AD, Abi-Raad R, Popa I, et al. Pathologic response and long-term follow-up in breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A comparison between classifications and their practical application. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1074–1082. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0290-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romero A, García-Sáenz JA, Fuentes-Ferrer M, et al. Correlation between response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and survival in locally advanced breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:655–661. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheri A, Smith IE, Johnston SR, et al. Residual proliferative cancer burden to predict long-term outcome following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:75–80. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee HJ, Park IA, Song IH, et al. Comparison of pathologic response evaluation systems after anthracycline with/without taxane-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy among different subtypes of breast cancers. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mittendorf EA, Jeruss JS, Tucker SL, et al. Validation of a novel staging system for disease-specific survival in patients with breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1956–1962. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.8469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mittendorf EA, Vila J, Tucker SL, et al. The Neo-Bioscore update for staging breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: Incorporation of prognostic biologic factors into staging after treatment. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:929–936. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marmé F, Lederer B, Blohmer JU, et al. Utility of the CPS+EG staging system in hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2016;53:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Minckwitz G, Untch M, Blohmer JU, et al. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1796–1804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Minckwitz G, Untch M, Nüesch E, et al. Impact of treatment characteristics on response of different breast cancer phenotypes: Pooled analysis of the German neo-adjuvant chemotherapy trials. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125:145–156. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Minckwitz G, Blohmer JU, Costa SD, et al. Response-guided neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3623–3630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Symmans WF, Hatzis C, Sotiriou C, et al. Genomic index of sensitivity to endocrine therapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4111–4119. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peintinger F, Buzdar AU, Kuerer HM, et al. Hormone receptor status and pathologic response of HER2-positive breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and trastuzumab. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:2020–2025. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mougalian SS, Hernandez M, Lei X, et al. Ten-year outcomes of patients with breast cancer with cytologically confirmed axillary lymph node metastases and pathologic complete response after primary systemic chemotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:508–516. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boughey JC, Suman VJ, Mittendorf EA, et al. Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: The ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:1455–1461. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caudle AS, Yang WT, Krishnamurthy S, et al. Improved axillary evaluation following neoadjuvant therapy for patients with node-positive breast cancer using selective evaluation of clipped nodes: Implementation of targeted axillary dissection. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1072–1078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residual. Biometrika. 1994:515–526. 81. [Google Scholar]