Abstract

This article describes the care processes for a 64-year-old man with newly diagnosed advanced non–small-cell lung cancer who was enrolled in a first-line clinical trial of a new immunotherapy regimen. The case highlights the concept of multiteam systems in cancer clinical research and clinical care. Because clinical research represents a highly dynamic entity—with studies frequently opening, closing, and undergoing modifications—concerted efforts of multiple teams are needed to respond to these changes while continuing to provide consistent, high-level care and timely, accurate clinical data. The case illustrates typical challenges of multiteam care processes. Compared with clinical tasks that are routinely performed by single teams, multiple-team care greatly increases the demands for communication, collaboration, cohesion, and coordination among team members. As the case illustrates, the described research team and clinical team are separated, resulting in suboptimal function. Individual team members interact predominantly with members of their own team. A considerable number of team members lack regular interaction with anyone outside their team. Accompanying this separation, the teams enact rivalries that impede collaboration. The teams have misaligned goals and competing priorities that create competition. Collective identity and cohesion across the two teams are low. Research team and clinical team members have limited knowledge of the roles and work of individuals outside their team. Recommendations to increase trust and collaboration are provided. Clinical providers and researchers may incorporate these themes into development and evaluation of multiteam systems, multidisciplinary teams, and cross-functional teams within their own institutions.

CASE SUMMARY

A 64-year-old man who works full time as an accountant and is a former smoker was recently diagnosed with stage 4 squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. At his initial clinic visit, the treating medical oncologist discusses the possibility of participating in a randomized trial of chemotherapy with or without a new immunotherapeutic agent. By the time the study coordinator is available, there are no available consultation or clinic rooms, so she gets approval from a charge nurse to speak to the patient in an unused infusion room. During the conversation, multiple infusion nurses, in a reportedly accusatory tone, enter the room asking whether the room was planned for treatment use. The patient signs a consent form during that meeting. Two days later, after a repeated brain magnetic resonance imaging scan, ECG, and blood work, the patient is found to qualify for the study and is randomly assigned to the experimental arm. According to study protocol, treatment must be initiated within 72 hours of registration. The research coordinator attempts to schedule the infusion, but there are no slots available. She contacts the infusion charge nurse, who is able to reschedule several other patients to fit the patient in, but is not happy with the last-minute appointment changes. Because of institutional policy (developed in 2015 for compliance with meaningful use requirements), the research coordinator—who does not have nursing training—is unable to sign orders for pretreatment laboratory tests. She therefore must ask the clinic nurse to do so. Later that afternoon, the research coordinator reviews all eligibility criteria with the treating physician, who is also the institutional principal investigator of the trial. They are also required to determine and document baseline tumor measurements. Because of other obligations, the physician defers this task until later in the day and complains to the research coordinator that the task will disrupt the physician’s schedule. The following day, the patient returns for treatment. The infusion nurses find that he has not received the standard chemotherapy teaching session, which results in a substantial backup in the infusion center. When the patient next returns to clinic, he comments on how disorganized the entire process seems to be. His perception is relayed to the treating physician’s team, and he proceeds with treatment.

Enrollment of patients with cancer in clinical trials remains a major goal of numerous national and global organizations.1 Clinical trials answer key clinical questions, lead to therapeutic clinical advances, provide patients with access to promising treatments, and are intended to deliver the highest level of cancer care available.2,3 Despite these goals, fewer than 5% of adult patients with cancer are enrolled in clinical trials.4-7 Several factors have been cited as contributing to limited participation, including stringent eligibility criteria, patient misunderstanding, lack of available protocols, physician preferences, and lack of knowledge of protocol content.6,8-11

The complexities of clinical research also have an impact on the care of patients once they initiate study therapy and procedures. Sponsor and regulatory directives have led to an increasing number of safety assessments, such as serial ECGs and frequent blood draws. The drive to maximize the scientific knowledge available from clinical trials has also led to a growing number of additional procedures, such as tests for blood- and tissue-based predictive and pharmacodynamic biomarkers.12,13 At the same time, standard clinical care of patients with cancer has also intensified. There are a growing number of available therapies with which clinic staff must be familiar. Financial pressures are resulting in demands to see more patients in clinic and infusion facilities. Electronic documentation and communication requirements have become more numerous and cumbersome.14,15

Given these developments, it comes as no surprise that the care of patients on clinical research protocols requires careful and continuous coordination between clinic teams and research teams. Yet, the increasing complexity and demands of both clinical care and research may make it difficult to combine the two.16 These considerations are highlighted in the case described in this article. How clinic and research teams divide tasks, maintain open lines of communication, and respond to unforeseen developments is critical to optimizing patient experience and safety, as well as generating high-quality clinical data. The resulting pressures have clear potential to strain these interactions.

Further complicating the interactions between clinic and research teams is the dynamic nature of clinical research. Unlike standard clinical procedures, which may remain unchanged for months or even years, clinical research procedures are constantly in flux. At a given institution, the clinical trial portfolio may change frequently. New trials open, older trials close, and ongoing trials undergo modifications to study design and procedures. As a result, staff may not have the opportunity to formally develop, evaluate, and disseminate operating processes for clinical trials to the extent they might for standard clinical care. Instead, clinic and research teams must maintain high levels of flexibility, adaptation, and cooperation.

Achieving these goals requires establishment of multiteam systems. Multiteam systems can be defined as two or more teams that interface directly and interdependently in response to environmental contingencies toward the accomplishment of collective goals.17 Multiteam system boundaries are defined by virtue of the fact that all teams within the system, while pursuing different proximal goals, share at least one common distal goal. As a consequence, teams within a multiteam system exhibit input, process, and outcome interdependence with each other. However, not all multiteam systems function effectively. Multiteam systems increase the demand for coordination and communication. Establishing an effective multiteam system involves building mutual trust and a collective identity. The way in which multiteam systems are formed influences their effectiveness. Collaboration among teams may be particularly challenging in situations in which the involved teams have strong identities and have previously worked independently.

In this report, we describe the case of a patient with newly diagnosed advanced lung cancer who participated in a clinical trial (Appendix: Clinical Case Research Study, Fig A1, and Table A1, online only). The delivered care was far from optimal—the case illustrates typical hurdles in the care delivery within clinical trials and tensions between research and clinic teams. We analyze the case by introducing the concepts of multiteam systems, multidisciplinary teams, and cross-functional teams. As the case illustrates, compared with clinical tasks that are routinely performed by single teams, multiple-team care greatly increases the demands for communication, collaboration, and coordination among team members. To provide effective care and useful study results, research and clinic teams must align their goals, overcome potential rivalries, increase collaboration and cohesion, and adapt their behaviors to frequently shifting study requirements. In our case, however, the teams were missing several of these critical elements. Drawing from experience in the medical and other professional fields, we conclude with recommendations—such as shadowing, cross-training, and mutual goal coordination—for integration and coordination of efforts across teams and also provide suggestions for future research.

COLLABORATIONS WITHIN AND ACROSS TEAMS: CHARACTERISTICS OF MULTITEAM SYSTEMS

Rapid advances in medicine and health care require personnel with highly specialized knowledge. This holds particularly true for the treatment of complex diseases such as cancer. Consequently, decisions about regimens as well as the implementation of treatment plans are often team based.18-20 Because of the complexity of the modern health care system, health care teams are typically highly diverse and consist of specialized members that greatly vary in their expertise, education, qualifications, and roles.21,22

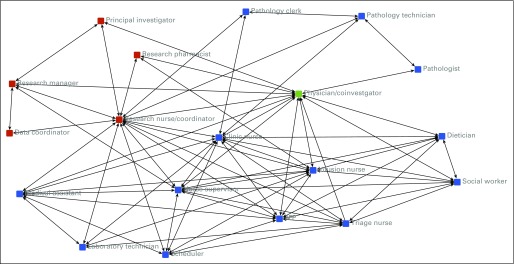

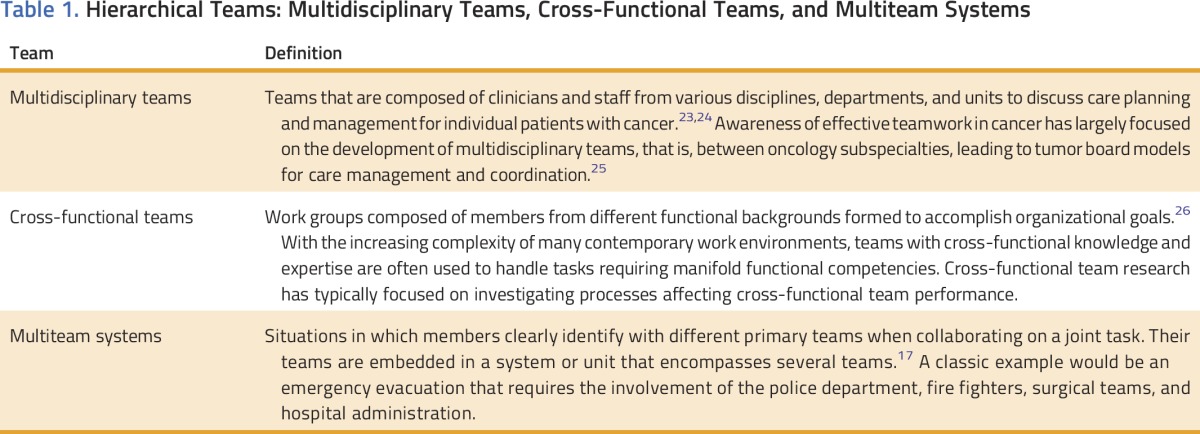

In many cases, medical teams are highly diverse, not only in terms of member demographics but also because they are composed of individuals representing a variety of disciplines and functional units within a health care organization. Moreover, complex tasks require the concerted effort of several teams. Many tasks in health care organizations are performed by multidisciplinary teams, cross-functional teams, and units that consist of multiple teams (Table 1). The three conceptualizations are not mutually exclusive. To the extent that members of a multiteam system directly work together and form a temporary new group, they are part of a cross-functional team. In the case described, the clinic and research teams strongly depend on each other and form a multiteam system (Fig 1). At the same time, team members represent different backgrounds and disciplines (eg, health v technical staff) and serve a variety of specific functions (see Appendix Table A1 for detailed functional descriptions of each position). A number of variables are important to successful functioning of multiteam systems. Chiefly, it is critical that members share collective goals and have shared mental models. An effective system is built on mutual trust and members’ willingness to communicate relevant information, coordinate actions, and collaborate to achieve overarching goals.

Table 1.

Hierarchical Teams: Multidisciplinary Teams, Cross-Functional Teams, and Multiteam Systems

FIG 1.

Social network demonstrating ties within and between the clinical research team and the clinic team. A connection between two individuals in the network indicates regular (at least once per week) interaction. Investigators aggregated team member self-report of interpersonal interactions by staff role. Red, clinic team. Blue, research team. Green, both clinic team and research team. APP, advanced practice provider.

Multiteam systems are defined as two or more teams that interface directly and interdependently in response to environmental contingencies toward the accomplishment of collective goals.17 Multiteam systems exhibit input, outcome, and process interdependence. Input interdependence refers to the extent to which teams share inputs such as people, facilities, equipment, and information. Outcome interdependence refers to the extent to which outcomes depend on the performance of other teams. Process interdependence refers to the amount of interteam interaction required for goal accomplishment. These interdependencies are present to some extent in all teams among individual team members. In multiteam systems, these interdependencies are more complex, as multiple teams’ tasks, goals, and outcomes interact.23

Shared understanding of goals and interdependencies across teams is crucial to allowing individual teams in multiteam systems to anticipate one another’s actions, adjust their own behavior accordingly, and communicate these adaptions efficiently.23,24 Lack of shared understanding about the demands of coordination often results in misunderstandings, inefficiencies, or delayed and ineffective communication among and between groups.23,24

Multiteam systems are characterized by a hierarchy of goals. On the basis of their interdependence, the involved teams share collective goals. Simultaneously, each team typically also has to fulfill its own specific goals, as do the individual members in each team. It is paramount that these goals are aligned and that members have a shared understanding of the overarching goals as well as the specific goals that each team seeks to accomplish. Teams must also communicate task-relevant information.27 High team performance in multiteam systems requires shared understanding of the task, the individual members’ goals, members’ expertise and roles, and teamwork. Complex tasks necessitate development of shared cognition, including shared understanding of how the team processes information. The sharedness of team members’ cognition refers to both agreement on and sharing of this information. Through communication, team members can arrive at shared understanding of team goals and roles, thereby enabling members to anticipate and coordinate team member actions.

Multiteam systems can work well when the involved teams have well-aligned goals, build mutual trust, and develop a shared understanding of their tasks, teams, and environments. In the current case, however, two interdependent teams that do not have a common agreement on their distal or proximal goals, but instead form different priorities, are required to interact.

APPLICATION TO CASE

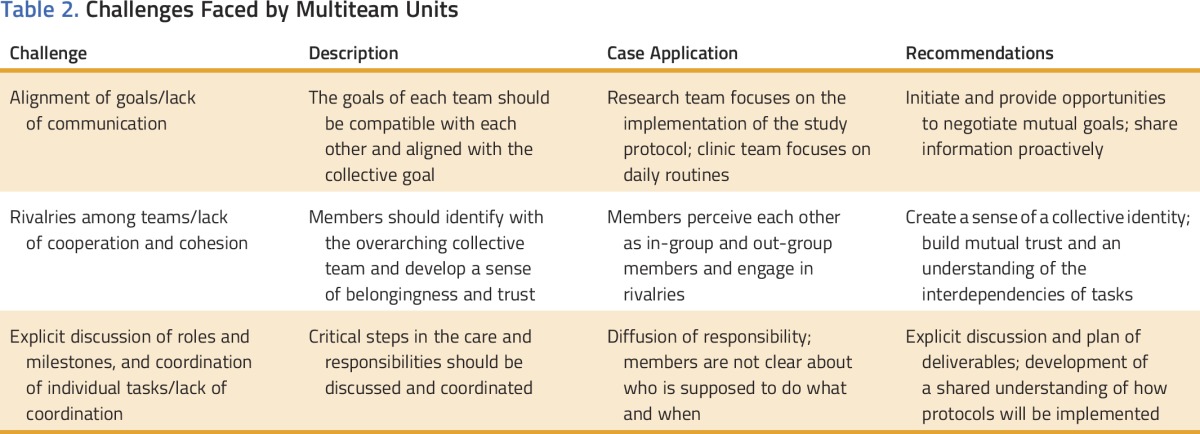

As our case illustrates, the described research team and clinic team are highly dependent on each other (high input, process, and outcome interdependency). Consequently, there are high demands for collaboration and high risk for coordination losses. However, the case also suggests problems and challenges: (1) lack of goal alignment, (2) rivalries among teams, (3) coordination and communication issues, and (4) trust issues (Table 2).

Table 2.

Challenges Faced by Multiteam Units

Clinical trials are generally considered the highest level of care available, not only because they provide access to new and promising treatments, but also because patients receive attention from additional staff. However, in addition to the overall goal to provide the best possible care for their patients, clinic staff and research staff also have their own local goals and agendas, which may conflict with each other. How care should be coordinated is not always clear. The division of labor can be arbitrary and difficult to interpret.28,29 In most cancer clinical trials, treatment and assessments largely resemble conventional treatment, with perhaps slight modification to a standard therapeutic regimen. Thus, where the scope of the clinic team ends and that of the research team begins may not be clear. In this case, this lack of clarity resulted in the patient not receiving a chemotherapy teaching session before his initial treatment.

Clinical trials place greater demands on all staff. Compared with nonprotocol care, clinical trials are relatively inflexible, as is evident in this case by the need to shuffle appointments on short notice to accommodate trial therapy. Clinical trials also frequently require extra diagnostic tests, safety assessments (eg, frequent ECGs), and additional documentation. These added requirements may be viewed by clinic team members as inconvenient and consuming resources that could otherwise be devoted to providing standard treatment to more patients.30 In our case, the principal investigator’s negative response to the requirement that she perform tumor measurements by a specified time point illustrates that even staunch advocates of the research mission may find protocol demands inconvenient. Consequently, research staff find themselves the inadvertent target of frustration related to issues of protocol design, with which they had no involvement. Indeed, between the demands of protocol requirements and the potential for stressful interactions in the workplace, over 40% of clinical research coordinators have reported burnout.31

Further complicating these considerations—or perhaps arising because of them—are clinic and research teams’ perceptions of themselves and one another. Clinic staff may view research staff as less hardworking because they follow fewer patients and are less frequently in clinic. This impression may reflect the clinic staff’s lack of awareness of coordinators’ numerous responsibilities (such as subject screening, data entry, and biospecimen processing) that occur outside clinic settings. Clinic staff may resent situations in which they are asked to take direction from someone who is not their supervisor and who may have less overall training and experience. For instance, junior clinical research coordinators may need to instruct senior infusion nurses on study drug administration, timing of vital sign assessments, and data collection.

Clinic and research teams may also appear to have opposing goals and misaligned expectations. Clinic staff and management may be focused on optimizing clinic efficiency and flow to accommodate the greatest patient volume while preserving care quality and safety. Conversely, research staff is primarily focused on protocol adherence and limiting deviations. Enrollment of patients on clinical trials may directly benefit research staff by increasing revenue for salary support. However, if patients on clinical trials require more intensive and less flexible care in the clinic, they could theoretically decrease revenue for clinic teams. Misaligned expectations may manifest as clinic staff anticipate that research staff will handle all aspects of a patient’s visit; conversely, research staff may expect infusion staff to know the specific details of each trial and to look up protocol details in depth.32

Organizational and facility structure may also contribute to a lack of interteam cohesion. Although clinic staff and research staff may contribute to the care of a similar group of patients, clinic staff and research staff may be housed in separate areas and have separate managerial structures. This departmental separation can lead to communication gaps. As a downstream result, a research coordinator on a lung cancer team is likely to feel a closer tie to a research coordinator on a breast cancer team than he or she might feel to a lung cancer clinic nurse.

Ultimately, these factors may have an impact on delivery of care, as in the case described here. Additionally, if specific roles of individual team members seem confusing to institutional staff, they can only be more confusing to patients. As patients progress through initial clinical evaluation to clinical trial screening, enrollment, and treatment, they may encounter nurses, advanced practice providers (nurse practitioners, physician assistants), research coordinators, research nurses, and research managers. Patients cannot be expected to understand each staff member’s role and background. Who the patient should contact with which question or concern becomes a complex consideration.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL CARE

Medical teams often face complex tasks that require teams to share task-relevant information to coordinate actions and collectively accomplish their goals.33,34 Teams that collaborate under conditions of high interdependence overcome rivalries and increase across-group cohesion. Some misalignment between goals and expectations (ie, organizational friction) is to be expected in the overlap of different functions, as when the clinic team and research team interact to achieve the mutual goal of quality care of shared patients.35 This friction may manifest as conflicting interactions or lack of communication about actions not completed or services not provided because of insufficient resources or delays resulting from interruptions to schedules and other process disturbances.36 Shared or externalized performance metrics may facilitate goal alignment and transparency.37

Studies of new team member integration suggest that standardized personnel scope of practice, common priorities, and shared performance metrics facilitate care team redesign.38 If done correctly, coaching and cross-training help improve cohesion and increase mutual understanding of tasks and roles, which has been found to decrease burnout.37,39 Studies of practice change and facilitation in oncology are emerging mostly in oncology nursing,40-43 with recent attention in community medical oncology.44,45 This may include asking research team members and clinic team members to shadow one another. With cross-training, research team members may formally train clinic staff on new protocols, whereas clinic team members orient research team members to clinic processes and flow.

Involving clinic staff early on, giving them meaningful roles, and providing them with opportunities to share in positive feedback resulting from successful completion of research projects may increase willingness to participate. It may also lead to research being viewed as a means of professional advancement and improvement of care quality.46 Key strategies for successful implementation and conduct of clinical research projects have been categorized as the following: generating support, engaging staff in the research process, assuring compliance with study protocol, energizing staff through the course of the project, resolving problems, and bringing the project to closure.47,48 Mentorship, collective support, and professional recognition and status have also been identified as key needs among staff involved in clinical research.49 To facilitate development of a research culture in community hospitals, the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program recommends engagement of institution leadership; utilization of collaborative learning structures where best practices, successes, and challenges can be shared; promotion of site-to-site mentoring; increased identification and use of metrics; and encouragement of research team engagement across hospital departments rather than the traditionally siloed approach to clinical trials.50 Finally, as a member of both the research team and the clinical team, the physician investigator is uniquely positioned to provide leadership and promote collaboration for this multiteam system.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH

Research is needed to examine permeable group membership—how individuals identify with their respective team or the larger multiteam system—specifically, how differences in perceived group status affect both intergroup and intragroup cohesion.51 Relevant psychological work on identity fusion has examined processes whereby relational ties grow in work teams among individuals who have personal relationships, motivating progroup behaviors.52 Studies are needed to understand the role of individuals who are members of more than one group. Efforts to understand the role of perceived status differentials between groups will be important as mandates to increase clinical trial participation alter organizational priorities. The effects of those shifting priorities on such perceptions will be important to employee satisfaction and morale.

A gap in the science of cancer care delivery lies in understanding and testing models of leadership in a multiteam system context.53-55 For example, can we test alternatives of leadership redundancy to understand how leadership roles contribute to coordination? Self-management competencies identified in other fields need to be adapted to understand their impact on multiteam systems in clinical oncology. Evidence-based management research, especially drawing from nursing and other clinical specialties, offers innovations to teamwork training and system redesign that need to be tested and disseminated in different oncology multiteam system settings.56-60 Key measures exist for change capacity (eg, adaptive reserve),61 team member morale,62,63 team functioning, and changes in responsibilities,64-66 but these have rarely been tested in the context of multiteam systems of oncology care.67 Furthermore, despite the centrality of teamwork to goals of patient-centered care, little work has been done to understand the evolving role of the patient and caregiver as contributing members of the oncology care team.68,69

In conclusion, a focus on interactions, perceptions, and attitudes between research staff and clinic staff is essential because clinical research changes too frequently and has too much variability to foresee all possible scenarios and proactively develop protocols. These concepts are not unique to lung cancer or even to oncology, but broadly applicable to the conduct of clinical research in any field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The production of this manuscript was funded by the Conquer Cancer Foundation Mission Endowment. This work was supported by a National Cancer Institute Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research, No. K24CA201543-01 (D.E.G.); the University of Texas Southwestern Center for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, No. AHRQ 1R24HS022418-01 (S.J.C.L.); and the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, which is supported in part by a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant, No. 1P30 CA142543-03. D.E.G. and T.R. contributed equally to this work. We thank Dru Gray for assistance with manuscript preparation and Helen Mayo, MLS, from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Library, for assistance with literature searches.

Appendix

Clinical Research Case Study

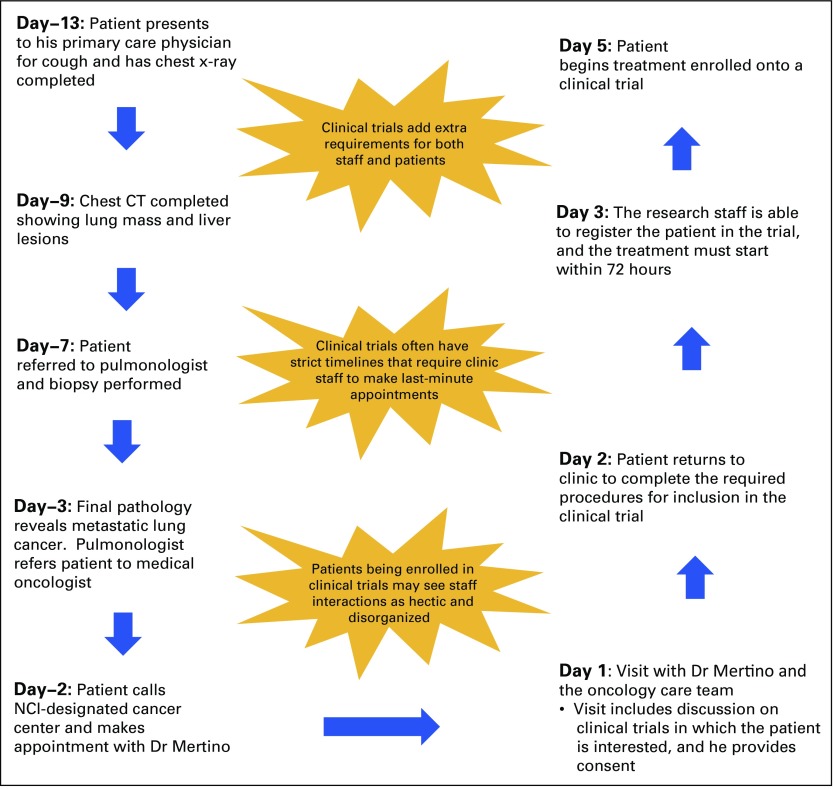

The patient is a 64-year-old, full-time accountant with a 20 pack-year smoking history (smoking his last cigarette approximately 10 years ago), dyslipidemia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He schedules a visit with his longstanding primary care physician for evaluation of a persistent cough (day −13). He receives a course of oral antibiotics and oral corticosteroids, and undergoes chest radiography. The chest x-ray shows a central left lung opacification suggestive of malignancy. A subsequent computed tomography (CT) scan (day −11) of the chest and abdomen performed 2 days later shows a 5-cm left suprahilar mass, bilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and three hypodense lesions in the liver. The following week, he is referred to an interventional pulmonologist for bronchoscopic evaluation. Instead, the pulmonologist orders a CT-guided percutaneous biopsy of a peripheral liver lesion (day −7). The final pathology report, available 4 days later (day −3), describes a cytokeratin 5/6–positive squamous cell carcinoma. The pulmonologist calls the patient that afternoon, informs him that he appears to have metastatic lung cancer, and refers him to a medical oncologist in the same multispecialty practice.

That evening, the patient speaks with a cousin whose father was treated for lung cancer at a National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center 2 years before. The cousin encourages the patient to schedule an appointment at the National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center in his community. After the call, the patient looks up the cancer center on the Internet. He is impressed by the extent and variety of services and the multiple references to experimental therapies. He also views several lung cancer Web sites, including those of two patient advocacy organizations. He notes several mentions of immunotherapy, a class of treatment he recalls reading about in a business magazine months before. The next day (day −2), the patient calls the cancer center and requests an appointment with one of the dedicated lung cancer medical oncologists.

Two days later (day 1; approximately 2 weeks after the first indication of cancer on the chest x-ray), the patient has an appointment with Dr Mertino, the head of the clinical lung cancer program. The patient comes prepared for the visit, bringing a chronology of his entire medical history; a typed list of his current medications; a three-ring binder with separate sections for laboratory, pathology, and radiology reports; and a disc with images from his recent radiology studies. In the waiting area, he notices numerous signs and pamphlets encouraging patients to inquire about the possibility of clinical trials.

During the 50-minute clinic visit, Dr Mertino reviews the patient’s medical history in depth, examines him, and reviews his CT images with him on the computer terminal in the clinic room. She describes the cancer as incurable but potentially treatable with systemic therapies, including standard chemotherapy and a clinical trial combining standard chemotherapy with immunotherapy. Having recently seen his relative experience substantial toxicities and little benefit from chemotherapy, the patient expresses interest in the clinical trial. Dr Mertino orders routine blood work and a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Over the next 15 minutes, the patient is visited by Dr Mertino’s clinic nurse, Raymond, who gives the patient a new patient packet with general information on lung cancer and chemotherapy, recommends that he receive a mediport for ease of treatment administration and future phlebotomy, and schedules the brain MRI for the next day. He is also seen by one of the cancer center social workers, who describes the supportive care program at the cancer center.

Dr Mertino’s clinical research coordinator, Jasmin, is contacted by Raymond while the patient is being seen by the social worker. Jasmin is processing research blood samples at the time, but tells Raymond that she will come by as soon as she finishes the work and returns to her desk to print out a study consent form. Because of the heavy clinic schedule that day, the patient is asked to return to the waiting area until Jasmin is available. By the time Jasmin arrives, there are no clinic or consultation rooms available. Raymond suggests that she speak with the clinic charge nurse, who tells Jasmin she will see whether there is an empty clinic room in which she can speak to the patient. The charge nurse finds a room in the infusion area, but tells Jasmin that she will be able to use it for only 15 minutes. Jasmin finds the patient in the waiting area and brings him to the infusion room. She starts to review the 26-page consent form with the patient, but on three separate occasions, they are interrupted by infusion nurses asking Jasmin whether she really has permission to use their room and when she will be finished. Apparently, another patient has arrived in the infusion area who needs intravenous fluids and antiemetics. Jasmin completes her review of the consent form and answers the patient’s questions, and the patient signs the consent form.

By the time Jasmin has finished, it is too late for her to follow up on additional enrollment and screening tasks. The next day (day 2), she reviews the chart and sees that the study-required brain MRI scan has already been ordered as standard of care by Dr Mertino’s clinic nurse, Raymond, as have most of the required laboratory tests. However, additional laboratory tests, such as coagulation parameters, amylase level, lipase level, thyroid function tests, and cortisol level have not been ordered. Because of institutional policy recently implemented to meet compliance with meaningful-use requirements, and as a research coordinator with no formal clinical training, Jasmin is not able to sign these orders on her own. She enters the orders in the electronic medical record. She then walks to the clinic, finds Raymond in between patient visits, and asks him to sign the orders. That afternoon, after undergoing the brain MRI, the patient returns to the clinic for a series of screening ECGs required for study enrollment. The next morning (day 3), Jasmin reviews all patient data and eligibility criteria with Dr Mertino. The patient is found to be eligible, is registered, and is randomly assigned to the experimental arm of chemotherapy plus immunotherapy. Jasmin reminds Dr Mertino that, following institutional protocol, baseline tumor measurements must be determined and documented before initiation of study therapy. Dr Mertino tells her that because of her busy schedule, they will need to meet again later in the afternoon after tumor board to perform this task. Jasmin arrives in the office suite at 3 pm as planned but is told by Dr Mertino’s administrative assistant that Dr Mertino is on a phone call with the department chair. Not wanting to miss the opportunity to catch Dr Mertino, Jasmin waits outside Dr Mertino’s office until the call ends. At 3:20 pm, she goes in and is told by Dr Mertino that their task is throwing a wrench in her schedule. Nevertheless, they complete the tumor measurements, which Jasmin places in the patient’s study binder.

According to study protocol, study treatment must be initiated within 72 hours of registration. Jasmin attempts to schedule the infusion, but there are no slots available. She contacts the infusion charge nurse. She is able to reschedule several other patients to fit the patient in but is somewhat frustrated by needing to make last-minute appointment changes. The patient returns 2 days later (day 5) for treatment. The infusion nurses find that he has not received the standard chemotherapy teaching session, which is typically performed in clinic before the first treatment day. One of the senior infusion nurses is pulled from her assigned bay to review chemotherapy premedications, the schedule, toxicities, and supportive care with the patient. These events result in a substantial backup in the infusion center. When the patient next returns to clinic (day 12), he comments to Raymond on how disorganized the entire process seems to be. Raymond conveys this to Dr Mertino. During the visit, Dr Mertino and Jasmin apologize to the patient for the hectic events of the initial days of study screening and treatment. They assure him that the schedule will become more predictable with subsequent treatment. The patient continues study treatment over the next 8 months, at which time he is found to have disease progression, discontinues study treatment, and initiates standard-of-care chemotherapy.

FIG A1.

Schematic of the events leading to treatment in the clinical trial. CT, computed tomography scan; NCI, National Cancer Institute.

Table A1.

Members of Clinic and Clinical Research Teams

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: David E. Gerber, Torsten Reimer, Joan H. Schiller, Simon J. Craddock Lee

Administrative support: David E. Gerber

Collection and assembly of data: David E. Gerber, Torsten Reimer, Erin L. Williams, Mary Gill, Laurin Loudat Priddy, Simon J. Craddock Lee

Data analysis and interpretation: David E. Gerber, Torsten Reimer, Laurin Loudat Priddy, Deidi Bergestuen, Haskell Kirkpatrick, Simon J. Craddock Lee

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Resolving Rivalries and Realigning Goals: Challenges of Clinical and Research Multiteam Systems

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jop.ascopubs.org/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

David E. Gerber

Stock or Other Ownership: Gilead Sciences

Research Funding: ImmunoGen (Inst), ArQule (Inst), Synta Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Celgene (Inst), ImClone Systems (Inst), BerGenBio (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Royalties from Oxford University Press from two books, royalties from Decision Support in Medicine from the Clinical Decision Support–Oncology online program

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Eli Lilly, ArQule

Torsten Reimer

No relationship to disclose

Erin L. Williams

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Eli Lilly

Mary Gill

No relationship to disclose

Laurin Loudat Priddy

No relationship to disclose

Deidi Bergestuen

Honoraria: Novartis, Novartis (I)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Novartis, Novartis (I)

Joan H. Schiller

Consulting or Advisory Role: Biodesix, AVEO Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Genentech, Synta Pharmaceuticals, Clovis Oncology, Genentech, Abbvie, Eli Lilly, Merck, EMD Serono, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, OncoGeneX

Research Funding: Synta Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Astex Pharmaceuticals (Inst), EMD Serono (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Clovis Oncology (Inst), Johnson & Johnson (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Puma Biotechnology (Inst), Abbvie (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Biodesix

Other Relationship: Free to Breathe

Haskell Kirkpatrick

No relationship to disclose

Simon J. Craddock Lee

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine: A national cancer clinical trials system for the 21st century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemieux J, Goodwin PJ, Pritchard KI, et al. Identification of cancer care and protocol characteristics associated with recruitment in breast cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4458–4465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filion M, Forget G, Brochu O, et al. Eligibility criteria in randomized phase II and III adjuvant and neoadjuvant breast cancer trials: Not a significant barrier to enrollment. Clin Trials. 2012;9:652–659. doi: 10.1177/1740774512456453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howerton MW, Gibbons MC, Baffi CR, et al. Provider roles in the recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2007;109:465–476. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman MA, Cain DF. National Cancer Institute sponsored cooperative clinical trials. Cancer. 1990;65(suppl):2376–2382. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900515)65:10+<2376::aid-cncr2820651504>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: Race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291:2720–2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lara PN, Jr, Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: Identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1728–1733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tournoux C, Katsahian S, Chevret S, et al. Factors influencing inclusion of patients with malignancies in clinical trials. Cancer. 2006;106:258–270. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerber DE, Laccetti AL, Xuan L, et al. Impact of prior cancer on eligibility for lung cancer clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju302. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerber DE, Rasco DW, Skinner CS, et al. Consent timing and experience: Modifiable factors that may influence interest in clinical research. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:91–96. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, et al. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: A systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1143–1156. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ledford H. Translational research: 4 ways to fix the clinical trial. Nature. 2011;477:526–528. doi: 10.1038/477526a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerber DE, Lakoduk AM, Priddy LL, et al. Temporal trends and predictors for cancer clinical trial availability for medically underserved populations. Oncologist. 2015;20:674–682. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill RG, Jr, Sears LM, Melanson SW. 4000 clicks: A productivity analysis of electronic medical records in a community hospital ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:1591–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerber DE, Laccetti AL, Chen B, et al. Predictors and intensity of online access to electronic medical records among patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e307–e312. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hange D, Björkelund C, Svenningsson I, et al. Experiences of staff members participating in primary care research activities: A qualitative study. Int J Gen Med. 2015;8:143–148. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S78847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathieu JE, Marks MA, Zaccaro SJ: Multi-team systems, in Anderson N, Ones DS, Sinangil HK, et al (eds): Handbook of Industrial, Work & Organizational Psychology: Vol 2: Organizational Psychology. London, United Kingdom, Sage, 2001, pp 289-313 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemieux-Charles L, McGuire WL. What do we know about health care team effectiveness? A review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63:263–300. doi: 10.1177/1077558706287003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reimer T, Russell T, Roland C: Decision making in medical teams, in Harrison TR, Williams EA (eds): Organizations, Health, and Communication. New York, NY, Routledge, 2015, pp 65-81 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mannix E, Neale MA. What differences make a difference? The promise and reality of diverse teams in organizations. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2005;6:31–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2005.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Der Vegt GS, Bunderson JS. Learning and performance in multidisciplinary teams: The importance of collective team identification. Acad Manage J. 2005;48:532–547. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larson JR, Jr, Christensen C, Franz TM, et al. Diagnosing groups: The pooling, management, and impact of shared and unshared case information in team-based medical decision making. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:93–108. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taplin SH, Weaver S, Chollette V, et al. Teams and teamwork during a cancer diagnosis: Interdependency within and between teams. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:231–238. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.003376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taplin SH, Weaver S, Salas E, et al. Reviewing cancer care team effectiveness. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:239–246. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.003350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al: Tumor boards and the quality of cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst 105:113-121, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Hüettermann H, Boerner S. Fostering innovation in functionally diverse teams: The two faces of transformational leadership. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2011;20:833–854. [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacMillan J, Entin EE, Serfaty D: Communication overhead: The hidden cost of team cognition, in Salas E, Fiore SM (eds): Team Cognition: Understanding the Factors That Drive Process and Performance. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2004, pp 61-82 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raja-Jones H. Role boundaries - research nurse or clinical nurse specialist? A literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11:415–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkes L, Cert R, Beale B. Role conflict: Appropriateness of a nurse researcher’s actions in the clinical field. Nurse Res. 2005;12:57–70. doi: 10.7748/nr2005.04.12.4.57.c5959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spilsbury K, Petherick E, Cullum N, et al. The role and potential contribution of clinical research nurses to clinical trials. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:549–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gwede CK, Johnsson DJ, Roberts C, et al. Burnout in clinical research coordinators in the United States. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:1123–1130. doi: 10.1188/05.onf.1123-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fitzgerald M, Milberger P, Tomlinson PS, et al. Clinical nurse specialist participation on a collaborative research project. Barriers and benefits. Clin Nurse Spec. 2003;17:44–49. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200301000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tschan F, Semmer NK, Hinziker S, et al: Decisive action vs. joint deliberation: Different medical tasks imply different coordination requirements, in Duffy VG (ed): Advances in human factors and ergonomics in healthcare. Boca Raton, FL, Taylor & Francis, 2011, pp 191-200 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salas E, Cooke NJ, Rosen MA. On teams, teamwork, and team performance: Discoveries and developments. Hum Factors. 2008;50:540–547. doi: 10.1518/001872008X288457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rochlin GI: Essential friction: Error-control in organizational behavior, in Akerman N (ed): The Necessity of Friction. Heidelberg, Germany, Physica-Verlag, 1993, pp 196-232 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koopmanschap MA, Rutten FF, van Ineveld BM, et al. The friction cost method for measuring indirect costs of disease. J Health Econ. 1995;14:171–189. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(94)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gwede C, Daniels S, Johnson D: Organization of clinical research services at investigative sites: Implications for workload management. Drug Inf J 35:695-705, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grace SM, Rich J, Chin W, et al. Flexible implementation and integration of new team members to support patient-centered care. Healthc (Amst) 2014;2:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ehrenberger HE, Lillington L. Development of a measure to delineate the clinical trials nursing role. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31:E64–E68. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.E64-E68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gosselin TK, Ireland AM, Newton S, et al. Practice innovations, change management, and resilience in oncology care settings. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42:683–687. doi: 10.1188/15.ONF.683-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irwin MM, Bergman RM, Richards R. The experience of implementing evidence-based practice change: A qualitative analysis. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:544–549. doi: 10.1188/13.CJON.544-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palos GR, Tortorella FR, Stepen K, et al. A multidisciplinary team approach to improving psychosocial care in patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:556–558. doi: 10.1188/13.CJON.556-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Portz D, Johnston MP. Implementation of an evidence-based education practice change for patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(suppl):36–40. doi: 10.1188/14.CJON.S2.36-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kent EE, Mitchell SA, Castro KM, et al. Cancer care delivery research: Building the evidence base to support practice change in community oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2705–2711. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.6210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kedia SK, Ward KD, Digney SA, et al. ‘One-stop shop’: Lung cancer patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions of multidisciplinary care in a community healthcare setting. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:456–464. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.07.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kemp MG, Keithley JK, Morreale B. Coordinating clinical research. A collaborative approach for perioperative nurses. AORN J. 1991;53:104–109. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(07)66117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner BS, Weiss M. How to make research happen: Working with staff. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1994;23:345–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1994.tb01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kenneth HY, Stiesmeyer JK. Strategies for involving staff in nursing research. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 1991;10:103–107. doi: 10.1097/00003465-199103000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rickard CM, Williams G, Ray-Barruel G, et al. Towards improved organisational support for nurses working in research roles in the clinical setting: A mixed method investigation. Collegian. 2011;18:165–176. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dimond EP, St Germain D, Nacpil LM, et al. Creating a “culture of research” in a community hospital: Strategies and tools from the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program. Clin Trials. 2015;12:246–256. doi: 10.1177/1740774515571141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ellemers N, van Knippenberg A, Wilke H. The influence of permeability of group boundaries and stability of group status on strategies of individual mobility and social change. Br J Soc Psychol. 1990;29:233–246. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1990.tb00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swann WB, Jetten J, Gómez A, et al. When group membership gets personal: A theory of identity fusion. Psychol Rev. 2012;119:441–456. doi: 10.1037/a0028589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jonassen JR. Effects of multi-team leadership on collaboration and integration in subsea operations. Int J Leadersh Stud. 2015;9:89–114. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johannessen IA, McArthur PW, Jonassen JR: Leadership redundancy in a multiteam system, in Frick J, Laugen BT (eds): Advances in Production Management Systems: IFIP AICT. Heidelberg, Germany, Springer, 2012, pp 549-556 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Millikin JP, Hom PW, Manz CC. Self-management competencies in self-managing teams: Their impact on multi-team system productivity. Leadersh Q. 2010;21:687–702. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bunnell CA, Gross AH, Weingart SN, et al. High performance teamwork training and systems redesign in outpatient oncology. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:405–413. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neily J, Mills PD, Young-Xu Y, et al. Association between implementation of a medical team training program and surgical mortality. JAMA. 2010;304:1693–1700. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spiva L, Robertson B, Delk ML, et al. Effectiveness of team training on fall prevention. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014;29:164–173. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3182a98247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Young-Xu Y, Neily J, Mills PD, et al. Association between implementation of a medical team training program and surgical morbidity. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1368–1373. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salas E, Rosen MA, Weaver SJ: Best practices for measuring team performance in healthcare, in McGahie WC (ed): International Best Practices for Evaluation in the Health Professions. London, UK, Radcliffe, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goldman RE, Parker DR, Brown J, et al. Recommendations for a mixed methods approach to evaluating the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:168–175. doi: 10.1370/afm.1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maslach C, Leiter M, Schaufeli W: Measuring burnout, in Cooper C, Cartright S (eds): The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Well-Being. Oxford, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 2009, pp 89-108 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M: Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual (ed 3). Mountain View, CA, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Partin MR, Burgess DJ, Burgess JF, Jr, et al. Organizational predictors of colonoscopy follow-up for positive fecal occult blood test results: An observational study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:422–434. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Castner J. Validity and reliability of the Brief TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Perceptions Questionnaire. J Nurs Meas. 2012;20:186–198. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.20.3.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guimond ME, Sole ML, Salas E. TeamSTEPPS. Am J Nurs. 2009;109:66–68. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000363359.84377.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Valentine MA, Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Measuring teamwork in health care settings: A review of survey instruments. Med Care. 2015;53:e16–e30. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827feef6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Frosch DL. The patient is the most important member of the team. BMJ. 2015;350:g7767. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tirodkar MA, Acciavatti N, Roth LM, et al. Lessons from early implementation of a patient-centered care model in oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:456–461. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.006072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]