Abstract

We present the case of a 92-year-old man, MH, who was given a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. His primary care physician, surgeon, geriatric oncologist, and family members all played important roles in his care. MH’s case is an example of a lack of explicit shared goal setting by the health care providers with the patient and family members and how that impeded care planning and health. This case demonstrates the importance of explicitly discussing and establishing shared goals in team-based cancer care delivery early on and throughout the care process, especially for older adults. Each individual member’s goals should be understood as they fit within the overarching shared team goals. We emphasize that shared goal setting and alignment of individual goals is a dynamic process that must occur several times at critical decision points throughout a patient’s care continuum. Providers and researchers can use this illustrative case to consider their own work and contemplate how shared goal setting can improve patient-centered care and health outcomes in various team-based care settings. Shared goal setting among team members has been demonstrated to improve outcomes in other contexts. However, we stress, that little investigation into the impact of shared goal setting on team-based cancer care delivery has been conducted. We list immediate research goals within team-based cancer care delivery that can provide a foundation for the understanding of the process and outcomes of shared goal setting.

INTRODUCTION

Patients, caregivers, physicians, and other health care providers all have individual goals as they embark on a cancer care journey. These individual goals, however, may not always be stated explicitly or result in a common shared goal among all team members (eg, patients, family/caregivers, physicians). Lack of explicit, dynamic shared team goals impedes teamwork and inhibits progress toward the health care team’s overarching care goals.

A goal is the objective or aim of an action, usually to be reached within a specific time frame.1 Goal setting is the act of determining a conscious goal or set of goals that influences action. Within the current context of oncology care, goals can be medical (eg, goal of treatment is curative versus palliative), functional (eg, goal for patient is to maintain independence during and after treatment), psychosocial (eg, goal for patient is to stay involved with social activities during treatment), or others.2 Several studies have examined the impact of setting specific goals on behavior and achievement.1,3-11 The common paradigm of such studies involves a comparison between individuals with specific goals and individuals who have been told to “do your best.” Overwhelmingly, goal specificity, especially for difficult goals, is superior for goal attainment,3 which indicates the importance of goal setting for achievement in various contexts, including health care.

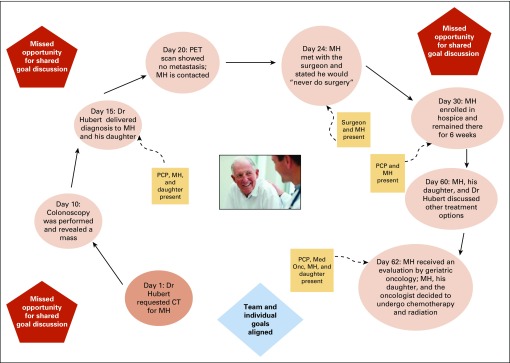

The case study summarized in Box 1 (the full version is presented in the Appendix, online only) and Figure 1 examines the principle of shared goal setting in team-based cancer care delivery and demonstrates that shared goal setting is critical for efficient team-based patient-centered care. We examine this case study through the lens of goal setting theory and the body of literature that has grown from it. We pay specific attention to work that has examined individual goals and shared team goals and the (negative) consequences when individual and team goals are inconsistent. We also emphasize that individual and shared team goals can change across a patient’s care continuum, and we review how to address inconsistent and changing goals at critical decision points. We then describe the implications of shared goal setting for patient care and for future research.

Box 1. Condensed Case Summary

MH is a 92-year-old male who presented to his primary care physician (PCP), Dr Hubert, with pelvic aching and a 3-month history of intermittent bright-red blood per rectum. At baseline, MH is functionally independent and generally fit, with mild limitations in physical activities caused by his arthritic knees. MH has known Dr Hubert for 2 years and has seen him for three office visits during this time. He does not feel the same connection he did with his prior PCP, Dr Smith, who he saw for > 30 years before Dr Smith’s retirement.

Upon hearing MH’s symptoms, Dr Hubert proceeded with referrals for imaging and colonoscopy, and a diagnosis of rectal cancer was promptly made. Dr Hubert met with MH and his daughter and disclosed the diagnosis and plans for additional imaging with a positron emission tomography scan. The goals of the patient and caregiver about treatment options were not elicited. A subsequent positron emission tomography scan confirmed localized disease, and MH was referred for colorectal surgery. Dr Hubert did not refer MH to medical oncology or radiation oncology because he was concerned about potential adverse effects on the basis of previous experiences with older patients who received chemotherapy and experienced significant adverse effects.

MH was evaluated by a colorectal surgeon who discussed potential surgical management options, including the potential for colostomy. MH stated that he would “never do surgery,” and he returned to Dr Hubert. Because MH declined surgery, he was placed in hospice care, with Dr Hubert serving as his hospice provider. After 3 weeks, MH’s daughter contacted Dr Hubert to inquire whether other options for treatment existed due to ongoing symptoms caused by the cancer. Because of MH’s advanced age and his prior experiences with other patients, Dr Hubert continued to act on his personal goal of minimal treatment-related adverse effects for MH, and he remained reluctant to consider chemotherapy or radiation therapy. After a discussion, the patient and his daughter asked to explore all treatment options to understand what therapies might help with symptom control. At this point Dr Hubert recommended an evaluation by geriatric oncology. The geriatric oncologist performed a comprehensive geriatric assessment, including evaluation of health status and potential risks of treatment, and MH was deemed to be a candidate for treatment. A conversation was held with the patient and daughter about the anticipated progression of locally advanced rectal cancer and likely symptoms to follow. MH stated that his goal was to minimize symptoms related to the cancer and to prolong life, if possible. MH was willing to accept moderate adverse effects of cancer treatment in exchange for improved control of his cancer symptoms. His daughter was included in this discussion and supported this decision. MH consented to definitive concurrent chemotherapy and radiation, and tolerated the treatment well. He remains free of measurable cancer 2 years after completion of therapy.

FIG 1.

Patient MH’s care path and its challenges. CT, computed tomography; Med Onc, medical oncologist; PCP, primary care physician; PET, positron emission tomography.

THE KEY PRINCIPLE: SHARED GOAL SETTING

Goal setting theory is a well-established theory of motivation.4,5 This theory has received considerable research attention, and its principles are widely applied to organizational practice in various industries. Goal setting initiates goal striving through three mechanisms6: directive function, which maintains attention toward goal-relevant activities and away from goal-irrelevant activities; energizing of function and persistence, which stipulate that difficult goals lead to greater effort compared with easy goals; and encouragement of the development and use of task strategies, which affects action indirectly by leading to the arousal, discovery, and/or use of task-relevant knowledge and strategies. The current case study allows us to analyze these mechanisms as they apply to individual goal setting in cancer care. First, some of those involved in this example (eg, the patient, primary care physician [PCP]) demonstrate directive function by focusing their attention on treating the patient’s cancer. Second, most individuals would consider treating cancer a difficult goal that requires considerable effort from all members of the health care team. Those involved in this case certainly demonstrate persistence because they treat MH, the patient, through various treatment strategies. Third, given the complexity of MH’s case and the delay in his treatment, the providers involved had to consider and implement other treatment strategies that were not immediately apparent. Unfortunately, although all three goal-striving mechanisms were operating in the current case, they were operating independently at the individual level and not at the shared team level. Clear shared goals are critical for team-based cancer care delivery because they ensure that individual action is directed toward a unified goal. Effective shared goal setting involves all care team members. Ideally, the patient, providers, and any caregivers would meet face to face early on and then throughout the care process to explicitly determine the shared goals of care, identify individual goals, and create mutual understanding of how individual goals fit within the shared team goals. Effective shared goal setting is a dynamic process of regular team meetings to establish shared and individual goals and to allow for the adjustment of goals as treatment circumstances evolve.

Research on goal setting within a team context is relevant both for our current case study and for team-based oncology care delivery in general.7,8 A meta-analysis of the effect of goal setting on group performance concluded that setting specific difficult goals increases group performance just as it does at the individual level. Moreover, group-centric individual goals (ie, goals focused on maximizing individual contributions to the group) improve group performance more than egocentric individual goals (ie, goals focused on maximizing individual performance).9 Similarly, high personal goals compatible with the group’s goal are beneficial for group performance, whereas personal goals incompatible with the group’s goal have a detrimental effect on group performance.10 Thus, the goals of every team member must contribute to the team’s shared goal. The establishment of cooperative and shared team goals that promote interdependence and collaboration will facilitate teamwork and increase the likelihood of achieving the team goal.1,11

Studies of goal setting in the health care team delivery context remain limited.12 Exceptions to this include investigations of goal setting in geriatric oncology. One study examined the concordance of goals among older patients, their family members, and providers. Types of goals were medical (eg, medications), functional (eg, walking), psychosocial (eg, coping), spiritual (eg, spiritual need), and future planning (eg, returning home). On average, patients and family members agreed on goals about half the time, and family members were likely to have more goals than patients. Agreement on goals among providers, patients, and families generally was poor. Overall, family members and providers identified more medical goals than did patients. Family members identified more functional, spiritual, and future planning goals than patients, who identified more of these goals than providers.2 Two recent studies investigated patient goals (in the domains of leisure, social, achievement, physical, and psychological) and goal strategies throughout the course of cancer treatment. Both articles reported a change in patient goals as the goals were achieved and in goal strategies, such as a move from shorter-term goals during treatment to longer-term goals after treatment and into survivorship.13,14 Therefore, shared team goals and individual goals must be established explicitly; otherwise, a collection of individual goals that are likely to change and unlikely to coalesce will emerge. Furthermore, these studies, coupled with findings from management literature on the importance of shared team-level goal setting for goal achievement, highlight the need to increase our understanding of shared goal setting in team-based cancer care delivery. Research from other fields has indicated that if goal setting is explicitly collaborative, everyone involved, including the patient, family members, and all providers, should know what the shared team goal is and where their individual goals fit within the team goal. This understanding should increase the likelihood of achieving the ultimate care goal. Further research should assess the impact of shared goal setting on the efficiency and quality of cancer care delivery.

UNDERSTANDING SHARED GOAL SETTING IN TEAM-BASED CANCER CARE DELIVERY: CASE CONSIDERATIONS

Organizations often use teamwork to address complex tasks. Cancer care delivery is a complex task that comprises several phases, including screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship. Each phase requires the expertise of various individuals whose joint cooperation is required for the achievement of the main goal (eg, high-quality patient-centered care).15 With a focus on treatment delivery, several team members help to develop treatment goals and guide planning. The current case included the patient MH; his daughter; and his PCP, surgical oncologist, radiation oncologist, and geriatric oncologist. Each member had some pre-existing values and beliefs that influenced how the care unfolded. For example, MH was unwilling to consider surgical intervention and colostomy placement, whereas the PCP was excluding chemotherapy as a potential treatment option. Recognition that prior experiences and pre-existing preferences influence goal setting is important in developing a cohesive team goal. In the current case, goal alignment among MH, his daughter, and his physicians was necessary, but MH’s goals and preferences were not explored. Not until he visited with the surgical oncologist did the other team members learn that MH was unwilling to consider surgical intervention. Lack of shared goal setting early on was likely because of an assumption that individual goals were already aligned and a discussion was unnecessary. The patient’s goals were ultimately elicited after he received information about the risks and benefits of the various treatment options. Later, the geriatric oncologist performed a comprehensive geriatric assessment, which allowed the physicians to better understand MH’s overall health status and to develop a treatment plan that was within the scope of what he could tolerate, thus better matching the goals of the treating providers with MH and his daughter.

Initially, MH’s goals seemed to be to retain his independence, relieve his symptoms, and live for as long as possible. The PCP’s goals were to minimize toxicity, and the surgeon may not have wanted to put an older person through the risks of a major surgical procedure. MH’s daughter wanted to keep her father comfortable and safe. Goal alignment among all team members could have been better established initially by eliciting goals and preferences. This process could have involved an early geriatric assessment to better understand the patient’s overall health status and allow physicians to identify feasible treatment options. Then an extensive discussion about each treatment option (eg, surgery, concurrent chemoradiation, radiation alone, best supportive care) could have occurred with MH and his daughter. This discussion would have allowed the physicians to offer therapeutic options that were consistent with pre-established goals (ie, safe cancer therapy) and to help MH to make an informed decision about treatment options on the basis of his goals and preferences. This approach requires the team to coordinate patient assessments, elicit patient values and goals, coordinate physician assessments and goals, and work with the patient to weigh the benefits and risks of each option within his or her value set.

In this situation, MH’s daughter was not included in relevant discussions about decision making, and her goals were not elicited early on. Older patients often have especially complex medical and social issues,16 and inclusion of the family and caregivers often is critical to successful goal setting. Older individuals with cancer have higher rates of comorbidity17 and polypharmacy18 compared with their younger counterparts, which may complicate cancer therapy. Impaired physical and cognitive function also is common, and cancer treatments can exacerbate these vulnerabilities.19-22 Older patients with cognitive impairment may have difficulty understanding care complexities and may struggle with goal setting. Caregiver involvement may be necessary in these cases to guide patient goal setting and ensure that team goals are aligned with patient goals.23 As noted, in the geriatric context, agreement on goals among providers, patients, and families is generally poor.2

IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL CANCER CARE

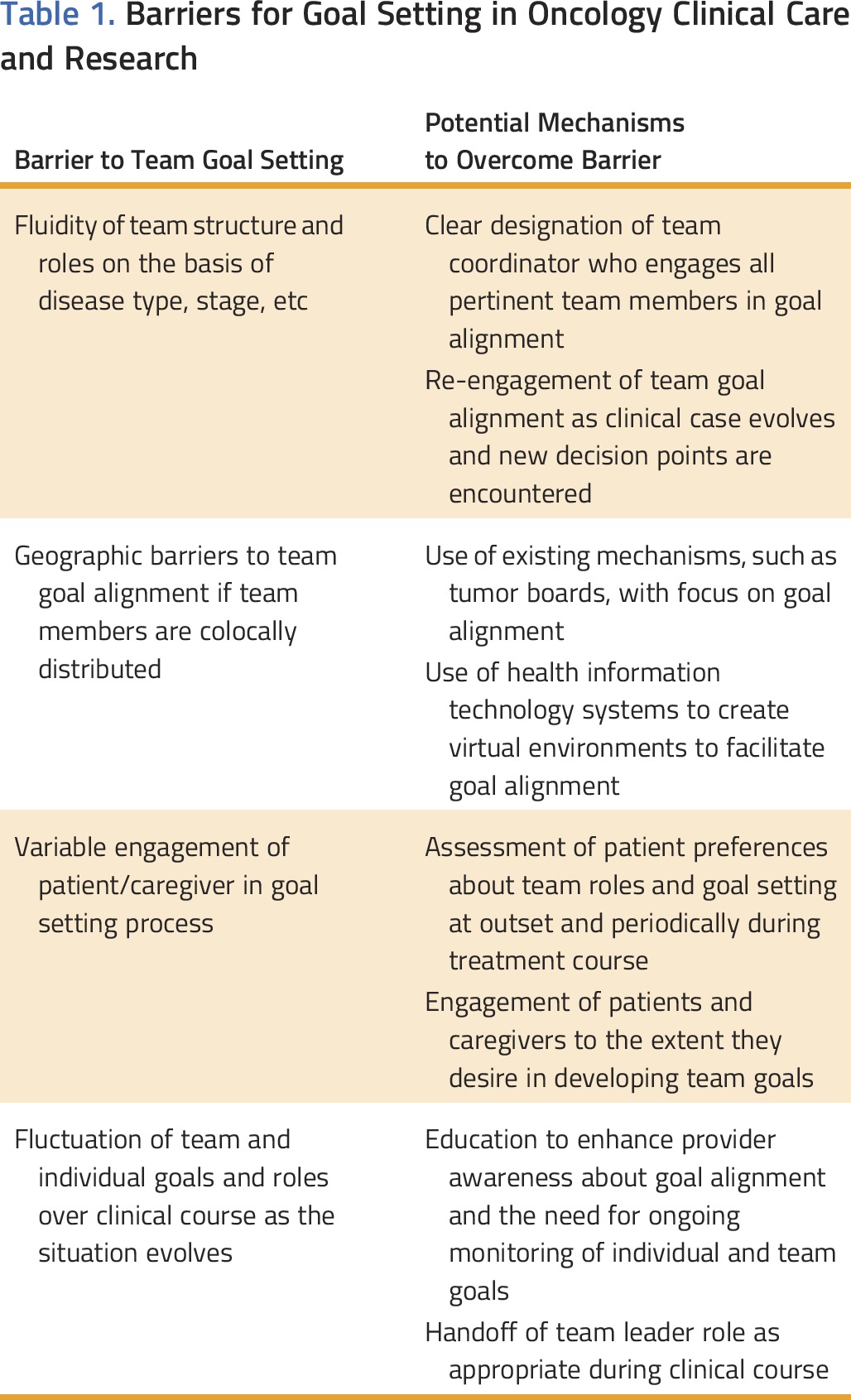

This case study took place within a geriatric oncology context, but its implications for shared goal setting in team-based oncology care are widely applicable (Table 1). Shared goal setting is a critical step toward establishing a cancer treatment plan that all team members can support and work toward for any patient. The patient and PCP remain central to this team model, but the involvement of additional members (eg, subspecialty providers, social workers, patient advocates, family members/caregivers) and the specific personal goals of individual team members will vary from case to case. The type and stage of cancer will also influence the selection of team members as well as shared and individual goal setting. Just as goals may fluctuate across the care continuum, the involvement of certain team members may also shift, and goal alignment must be readdressed frequently. For example, when disease status changes (ie, disease recurrence) or treatment-related toxicity is encountered, the team should reassess goal alignment.

Table 1.

Barriers for Goal Setting in Oncology Clinical Care and Research

Each clinical scenario also elicits different inherent values among team members and influences their individual goal setting. For example, in this case, the PCP had previously witnessed older patients experience difficulty with chemotherapy; therefore, he was reluctant to refer older patients to medical oncology because they might incur similar hardships. Ageism is a potential bias that may affect the care older patients receive.24 It is possible that the PCP was influenced by ageism when he developed his care recommendations for MH. Research in oncology and primary care has shown that a physician’s implicit racial bias can influence interactions with patients as well as the patients’ perceptions of the physician.25-27 Ageism (and other types of bias) may operate similarly. Furthermore, older adults are under-represented in oncology clinical trials. Therefore, a relative lack of data is available to guide cancer treatment decisions and goal setting in this population.21 In summary, a variety of factors may have played a role in the care decisions and sequence of events that may have impeded shared goal setting. All these factors warrant further investigation.

Although the patient is at the center of the team, the coordinator of the cancer care team may vary from case to case. This variation emphasizes the importance of role definition as a key component of the goal setting process because the coordinator of the treatment team is responsible for goal alignment among team members. Within a multidisciplinary cancer care team, some patients may be managed primarily by one team member over another, depending on the type and/or stage of cancer. The coordinator of the team may also change at different points on the cancer care continuum. For example, in patients with localized, early-stage breast cancer, surgical oncology may initially fill the role of coordinator during evaluation and surgical management of the disease. The role of coordinator would then transfer to medical oncology and/or radiation oncology for consideration and delivery of adjuvant therapy. If metastatic disease develops in the patient, medical oncology likely would serve as coordinator during this care period. A palliative care or hospice provider may serve as coordinator at the end of life. Therefore, to ensure that goals are aligned effectively, explicit role definition of all team members must be established at the outset and renegotiated at time points when disease status changes. The handoff of the team coordinator role along with the realignment of shared team goals should be clearly defined to enhance teamwork and optimize alignment of goals and care coordination. An understanding one’s role within the team and the shared team goals is essential for team effectiveness.28 Even when team members share the desire to establish a collaborative and cooperative practice with aligned goals, misunderstandings and conflicts around roles are frequent and can be detrimental to the achievement of the shared team goal.29

The mechanism for alignment of individual goals varies among clinical practices. In many medical centers, a tumor board system convenes to allow members of the cancer treatment team to discuss shared cases. This setting offers an ideal opportunity to review specific cases, set individual goals for several team members, and align goals effectively. However, not every institution has an established tumor board system, and often, not all team members are present for the discussion. In addition, patients are rarely invited, and PCPs typically do not attend. Another difficulty is that all team members may not be geographically colocated. For example, one team member may be part of another health system or may practice at an offsite location. The creation of other opportunities for discussion among team members and alignment of goals may require a virtual discussion. Electronic medical records may make these discussions more feasible, but information on the effectiveness of this type of distributed team coordination and shared goal setting is limited.

Another variable in goal setting is the involvement of the patient and informal caregivers. The level of patient engagement and the degree to which they help to drive their care and influence team goals can vary from case to case. Some patients are motivated to serve as a vital team member with regard to goal setting; others prefer to have health care providers lead the development of the care plan.30 The determination of a patient’s preferences with regard to decision making and autonomy is important in establishing shared goal setting. Caregiver involvement and goal alignment with patient goals also are variable from case to case. Caregiver involvement often is crucial, especially for older patients, and involvement of caregivers in goal setting is critical to the development of a successful cancer treatment plan.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH

Explicit and collaborative development of a shared team goal that aligns individual goals is readily recognized as important for achieving a common team goal. However, a dearth of empirical data exists on the development of shared team goals and the influence of shared goal setting on health outcomes in team-based cancer care delivery. Specifically, there is a lack of understanding about how team coordinators are identified in a clinical situation, the process of creating team-level and individual-level goals, how team coordinators align individual goals dynamically throughout the care delivery process, and whether shared goal setting affects care delivery and outcomes in cancer care. The literature review used to assess this case study demonstrates a pressing need to examine goal setting in the oncology context specifically. Moreover, an examination of geographically distributed and multidisciplinary cancer care delivery teams is needed because these teams possess unique aspects not addressed in the current health care delivery literature (eg, anonymity).1 Major knowledge gaps exist, and we propose the following questions for future targeted research on this topic:

How do oncology providers recognize their inherent biases, and how do these biases influence their individual goal setting in clinical situations?

How are the patient and, if applicable, the family members/caregivers promoted as team members within the shared and individual goal setting process?

How should oncology professionals be educated about the need to establish role definition and alignment of individual goals with a shared team goal at the outset of each clinical case and throughout the care continuum?

How are team coordinators identified, and how does this role shift over the clinical course?

How are role definition, shared goals, and aligned individual goals promoted in cancer care delivery at the organization and/or system level?

How can electronic medical records be used to facilitate shared goal setting and alignment of individual goals among colocated and distributed team members?

How does shared goal setting affect coordination and outcomes of care?

In summary, shared goal setting is a critical component for delivering an optimal team-based cancer care plan, especially for older adults. An understanding of all team members’ goals, including those of the patient, family members, caregivers, and involved care providers, is essential to the development of a cohesive treatment plan. The establishment of shared team goals, alignment of individual goals early on, and realignment of goals across the care continuum are key to realizing patient-centered team-based cancer care delivery and optimizing health outcomes. Several knowledge gaps still exist, including how shared goal setting and individual goal alignment currently occur in cancer care, how to enhance team goal setting in this area, and how goal setting influences outcomes, and must be addressed with further research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The production of this manuscript was funded by the Conquer Cancer Foundation Mission Endowment. The work was funded by the Wilmot Research Fellowship Award (A.M.) and with support from National Cancer Institute R25CA102618. This work was also funded in part by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Program contract (4634). All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors, do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Appendix

Case Summary

MH is a 92-year-old robust male with moderate knee and hip osteoarthritis, hypertension, and remote history of cerebrovascular accident (with mild residual left-sided vision loss) who presented to his primary care physician (PCP), Dr Hubert, with increased dull pelvic aching and a 3-month history of intermittent bright-red blood per rectum without a history of hemorrhoids. Colorectal cancer screening was last performed by colonoscopy at age 80 years and was normal. At baseline, MH is functionally independent with activities of daily living but limited in physical exercise activities because of his arthritic knees. He had two mechanical falls in the past 6 months. MH is assisted with financial management, shopping, and cleaning by his involved daughter with whom he lives.

MH has known Dr Hubert for 2 years. He has seen him for only three office visits during this time. MH does not feel the same connection he did with his prior PCP, Dr Smith, who he saw for > 30 years before Dr Smith’s retirement. Dr Hubert is a member of a primary care group with 18 physicians in two large offices and accepts reimbursement from Medicare and Medicaid. He refers to two hospitals and several independent groups of subspecialists within a city population of nearly 3 million.

Upon hearing MH’s history of pelvic pain and bright-red blood per rectum, Dr Hubert requested computed tomography imaging of the abdomen and pelvis without intravenous contrast (day 1), which was readily scheduled and performed on day 3. Imaging revealed asymmetric wall thickening of the right anterior rectal wall and right external iliac lymph node enlargement (1.8 cm). Carcinoembryonic antigen was not elevated (1.6). Dr Hubert referred MH to a gastroenterologist, and colonoscopy was performed in a timely manner (day 10). Colonoscopy revealed a 6-cm nonobstructive rectal mass; a biopsy specimen was taken. On day 14, pathology results returned as moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, and the diagnosis was disclosed to the patient and his daughter during an office visit with Dr Hubert on day 15. During this visit, the diagnosis was reviewed, but the goals and preferences of the patient, daughter, and Dr Hubert were not explicitly discussed. MH was then referred for positron emission tomography (PET) examination to complete staging. PET scanning was performed on day 20 and showed no avidity in the external iliac lymph node. The radiologist contacted Dr Hubert about the lack of measurable metastatic disease, and Dr Hubert referred MH to a colorectal surgeon. This referral was made directly after results of the PET scan, and no appointment with the patient was held in the interim. Dr Hubert did not make a referral to medical oncology or radiation oncology because he was reluctant, on the basis of his personal experience and goals, for the patient to experience any adverse effects from treatment. He had previously referred older patients who received chemotherapy and experienced significant adverse effects and thus did not refer MH for consideration of this type of treatment.

MH was referred to colorectal surgery for evaluation on day 21, and he was seen on day 24. The surgeon and MH (his daughter was not in attendance) talked about surgical management options and. They also discussed the potential for colostomy, and MH stated that he would “never do surgery.” The surgeon contacted Dr Hubert to relay the results of this conversation. The patient returned to Dr Hubert on day 28, and he was placed in hospice care, with Dr Hubert serving as his hospice provider. MH’s daughter was not present for this visit or involved in the discussion or decision. Given MH’s advanced age, Dr Hubert continued to set a personal goal of minimal treatment-related adverse effects for MH, and he remained reluctant to consider chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

After 3 weeks, MH continued to experience symptoms related to the malignancy, and his daughter contacted Dr Hubert to inquire whether other options for treatment existed. MH and his daughter requested an office visit to discuss alternative options, which occurred on day 53. MH and his daughter expressed a desire to explore all treatment options and to understand what therapies might help with symptom control. Given the patient’s advanced age, Dr Hubert recommended an evaluation by geriatric oncology, which occurred on day 55. The geriatric oncologist performed a comprehensive geriatric assessment, including an evaluation of health status and potential risks of treatment, and MH was identified as a candidate for treatment. MH, his daughter, and Dr Hubert discussed the anticipated progression of locally advanced rectal cancer and the resulting symptoms before the end of life. This visit also included a discussion about the MH’s goals and preferences. MH stated that his goal was to minimize symptoms related to the cancer and to prolong life, if possible. He was willing to accept moderate adverse effects of cancer treatment in exchange for improved control of his cancer symptoms. Ultimately, with an understanding of the risks of treatment as well as the potential benefits with regard to controlling cancer-related symptoms, MH agreed to explore treatments other than surgery. His daughter was included in the conversation and supportive of this decision. MH was evaluated by radiation oncology and consented to definitive concurrent chemotherapy and radiation. His treatment was supported with home physical therapy for fall prevention, information and support about delirium risk given mild cognitive impairment, and financial assistance for oral chemotherapy medications. MH tolerated the treatment well with mild diarrhea and mucositis, and he remains free of measurable cancer 2 years after completion of therapy.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Allison Magnuson, James Wallace, Beverly Canin, William Dale, Lauren M. Hamel

Collection and assembly of data: Allison Magnuson, Supriya G. Mohile, Lauren M. Hamel

Data analysis and interpretation: Allison Magnuson, Selina Chow, Supriya G. Mohile, Lauren M. Hamel

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Shared Goal Setting in Team-Based Geriatric Oncology

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jop.ascopubs.org/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Allison Magnuson

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: ASCO

James Wallace

Consulting or Advisory Role: Eli Lilly

Speakers’ Bureau: Astellas, Medivation

Beverly Canin

No relationship to disclose

Selina Chow

No relationship to disclose

William Dale

No relationship to disclose

Supriya G. Mohile

Consulting or Advisory Role: Seattle Genetics

Lauren M. Hamel

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1. Kramer WS, Thayer AL, Salas E: Goal setting in teams, in Locke EA, Latham GP (eds): New Developments in Goal Setting and Task Performance. East Sussex, UK, Routledge, 2013, pp 287-310. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glazier SR, Schuman J, Keltz E, et al. Taking the next steps in goal ascertainment: A prospective study of patient, team, and family perspectives using a comprehensive standardized menu in a geriatric assessment and treatment unit. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:284–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Locke EA, Shaw KS, Saari LM, et al: Goal setting and task performance: 1969-1980. Psychol Bull 90:125-152, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latham GP, Locke EA. New developments in and directions for goal-setting research. Eur Psychol. 2007;12:290–300. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Locke EA, Latham GP: Goal-setting theory, in O’Neil HF Jr, Drillings M (eds): Motivation: Theory and Research. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1994, pp 13-30. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. A 35-year odyssey. Am Psychol. 2002;57:705–717. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Locke EA, Latham GP: A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance. New York, NY, Prentice-Hall, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Leary-Kelly AM, Martocchio JJ, Frink DD. A review of the influence of group goals on group-performance. Acad Manage J. 1994;37:1285–1301. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleingeld A, van Mierlo H, Arends L. The effect of goal setting on group performance: A meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96:1289–1304. doi: 10.1037/a0024315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seijts GH, Latham GP. The effects of goal setting and group size on performance in a social dilemma. Can J Behav Sci. 2000;32:104–116. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Mierlo H, Kleingeld A. Goals, strategies, and group performance: Some limits of goal setting in groups. Small Group Res. 2010;41:524–555. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levack WMM, Dean SG, Siegert RJ, et al. Navigating patient-centered goal setting in inpatient stroke rehabilitation: How clinicians control the process to meet perceived professional responsibilities. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janse M, Ranchor AV, Smink A, et al. People with cancer use goal adjustment strategies in the first 6 months after diagnosis and tell us how. Br J Health Psychol. 2016;21:268–284. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janse M, Fleer J, Smink A, et al. Which goal adjustment strategies do cancer patients use? A longitudinal study. Psychooncology. 2016;25:332–338. doi: 10.1002/pon.3924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wegge J, Van Dick R, von Bernstorff C. Emotional dissonance in call centre work. J Manag Psychol. 2010;25:596–619. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balducci L, Aapro M. Complicated and complex: Helping the older patient with cancer to exit the labyrinth. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5:116–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soubeyran P, Fonck M, Blanc-Bisson C, et al. Predictors of early death risk in older patients treated with first-line chemotherapy for cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1829–1834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prithviraj GK, Koroukian S, Margevicius S, et al. Patient characteristics associated with polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing of medications among older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lange M, Rigal O, Clarisse B, et al. Cognitive dysfunctions in elderly cancer patients: A new challenge for oncologists. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2595–2603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, et al. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:2061–2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3457–3465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Extermann M. Older patients, cognitive impairment, and cancer: an increasingly frequent triad. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2005;3:593–596. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2005.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson TD. Ageism: Prejudice against our feared future self. J Soc Issues. 2005;61:207–221. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penner LA, Dovidio JF, West TV, et al. Aversive racism and medical interactions with black patients: A field study. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46:436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:979–987. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blair IV, Steiner JF, Fairclough DL, et al. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among black and Latino patients. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:43–52. doi: 10.1370/afm.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu J, Liden RC. Antecedents of team potency and team effectiveness: An examination of goal and process clarity and servant leadership. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96:851–862. doi: 10.1037/a0022465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Contandriopoulos D, Brousselle A, Dubois CA, et al. A process-based framework to guide nurse practitioners integration into primary healthcare teams: Results from a logic analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:78. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0731-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sainio C, Lauri S, Eriksson E. Cancer patients’ views and experiences of participation in care and decision making. Nurs Ethics. 2001;8:97–113. doi: 10.1177/096973300100800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]