Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of treatment summaries and survivorship care plans coupled with a nurse counseling session, primarily on physician implementation of and secondarily on patient adherence to recommended survivorship care, among a low-income population of breast cancer survivors (survivors).

Methods

We recruited 212 low-income, predominantly Latina (72.6%) survivors with stage 0 to III breast cancer, with an average age of 53 years, from two Los Angeles County public hospitals into an RCT of a survivorship care nurse counseling session coupled with the provision of individualized treatment summaries and survivorship care plans to patients and their health care providers from December 2012 to July 2014. One hundred seven survivors received the experimental intervention, and 105 survivors received usual care. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to assess intervention effects on physician implementation of and patient adherence to recommended survivorship care. Scales that served as covariables were Knowledge of Survivorship Issues, Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions, and Satisfaction With Care and Information.

Results

Survivors in the intervention group reported greater physician implementation of recommended breast cancer survivorship care, for example, treatment of depression or hot flashes, than did those in the control group (adjusted difference, 16 ± 5.3; P = .003). Baseline Satisfaction With Care and Information was positively associated with physician implementation (coefficient, 5.2 ± 2.2; P = .02). Being married/partnered (−11.8 ± 4.0; P = .004) and age (−0.5 ± 0.2; P = .028) were negatively associated with patient adherence.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first RCT of survivorship care plans to show benefits in clinical outcomes, in this case, showing increased physician implementation of recommended breast cancer survivorship care in the intervention group, compared with the control group.

INTRODUCTION

There are over 15.5 million cancer survivors in the United States,1 with breast cancer, accounting for 22% (approximately 3.2 million)1,2 of the survivor population. The Institute of Medicine has recommended the use of treatment summaries and survivorship care plans (TSSPs) to promote improved coordination of post-treatment care in cancer survivors.3 Patients with breast cancer can expect long-term survival4; however, the complex, multimodal treatments that achieve these outcomes need to be summarized to provide better long-term follow-up care. TSSPs are strongly advocated by ASCO,5 and patients endorse the need for written follow-up plans after treatment is ended.6

The Institute of Medicine also recommended conducting research on the implementation of TSSPs.3 Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) performed to date have shown little or no impact on patient outcomes. An RCT conducted in the Canadian health system among breast cancer survivors found no differences in cancer-related distress, quality of life, patient satisfaction, continuity/coordination of care, and health service measures.7 Another RCT of TSSPs after breast cancer adjuvant therapy found only decreased health worry and no differences in impact of cancer, patient satisfaction, and all other measures of survivorship concerns.8 An RCT among gynecologic cancer survivors noted no significant differences in patient-reported outcomes of health services, helpfulness of materials, or perceptions of care.9 To our knowledge, no RCTs of TSSPs have been conducted among medically underserved breast cancer survivors, in whom we hypothesized there would be more care needs with greater likelihood of benefit from TSSPs. To test this hypothesis, we designed and evaluated an intervention specifically tailored to the needs of this vulnerable population.

METHODS

Overall Study Design

Figure 1 shows the overall study design. We performed qualitative research to create a culturally and educationally tailored computerized TSSP builder adapted for Spanish- and English-speaking populations. After a baseline telephone interview, eligible participants were randomly assigned to intervention or usual care groups. The primary outcome was physician implementation of TSSP care recommendations over the course of 12 months, assessed by quarterly participant interviews.

Fig 1.

Overall study design. TSSP, treatment summary and survivorship care plan.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were recruited from breast clinics at two public institutions in Los Angeles County, Harbor-University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center (n = 104) and Los Angeles County plus University of Southern California Medical Center (n = 108). Patients were eligible if they were female; were ≥ 21 years old; were diagnosed with stage 0, I, II, or III breast cancer 10 to 24 months earlier; had their last definitive treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiation) at least 1 month earlier; and were English or Spanish speaking. Patients were excluded if they had a previous cancer, except nonmelanomatous skin cancers or in situ (nonbreast) cancers; were pregnant or lactating; were currently receiving trastuzumab or other parenteral anticancer therapy; had metastatic disease; had clinically apparent cognitive or psychiatric impairment; were participating in another research study; or were receiving treatment of another cancer. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of both county hospitals and UCLA.

Eligibility/exclusion criteria were used to identify potential participants from clinic databases. We mailed invitation letters to 824 potential participants, including a response form to indicate interest in participation (Fig 2). At least 439 patients were ineligible or eligibility could not be confirmed. The research team received contact information for interested respondents and for those who did not respond to the recruitment letter within 2 weeks. Research staff telephoned potential participants to explain details of the study. Women who agreed to participate were mailed study consent and medical record release forms. Medical records were obtained for all participants. We offered a $40 incentive for completion of baseline and 12-month follow-up telephone interviews. Participant accrual was from December 2012 to July 2014.

Fig 2.

Study flow diagram. TSSP, treatment summary and survivorship care plan.

Baseline Interview

Predictor variables included (1) knowledge about survivorship issues: the first part of the Preparing for Life as a (New) Survivor (PLANS) Scale adapted from Palmer et al9a, consisting of 11 items that assess knowledge about survivorship; (2) patient-perceived self-efficacy in patient-physician communication: measured using the validated five-item Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions (PEPPI) questionnaire,10 whose summary scale ranges from 0 to 50 (higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy); and (3) Satisfaction With Care and Information Scale: a 23-item scale11 that asks about patient satisfaction, with information received regarding breast cancer diagnosis, treatment, and post-treatment–related issues. We used the mean score of these questions (1 = very dissatisfied and 5 = very satisfied).

Other measures included general health status (poor/fair v good/excellent) and information about usual source of care. Participant characteristics included age, race/ethnicity, education, and employment status. Comorbidity was measured using the Katz et al12 adaptation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index for patient self-report and was dichotomized into any comorbidity versus none.

Randomization

Randomization occurred after the baseline interview, stratified by ethnicity (Latina v non-Latina), with a one-to-one allocation to intervention or control within each study site, using a permuted block design with a block size of 4 or 6.

Intervention

The intervention focused on the development and receipt of an individually tailored TSSP and one in-person counseling session with a trained, bilingual, bicultural nurse to review the contents. The essential elements of TSSPs have been well delineated.13,14 TSSPs were generated by a computerized program that was based on the Journey Forward survivorship care plan builder,15 but adapted for low-literacy and Spanish-speaking populations (details provided in Table 1; Appendix 1, online only).

Table 1.

Treatment Summary and Survivorship Care Plan Components and Contents

One month after the baseline interview, the nurse scheduled a 1-hour session with each intervention participant in a research office at UCLA to review the TSSP. Participants were coached to write down their three most important questions as a means of increasing empowerment in communication with their physicians.16-19 They practiced role playing these discussions, as well as asking for implementation of the survivorship care recommendations. Each woman was encouraged to make an appointment with the physician most involved with her cancer care to discuss the TSSP and the question list, and to take a copy of her TSSP to future visits with other providers. A cover letter and two copies of the TSSP were mailed to the chiefs of the breast clinics at the two study sites to be scanned into or attached to the patients’ medical records. Patients were given extra copies to take to future visits with providers. Appendix 2 (online only) provides more details on the counseling intervention and its process assessment. Usual care was provided to the control-group participants who received their personalized TSSPs after the final study data collection.

Outcomes

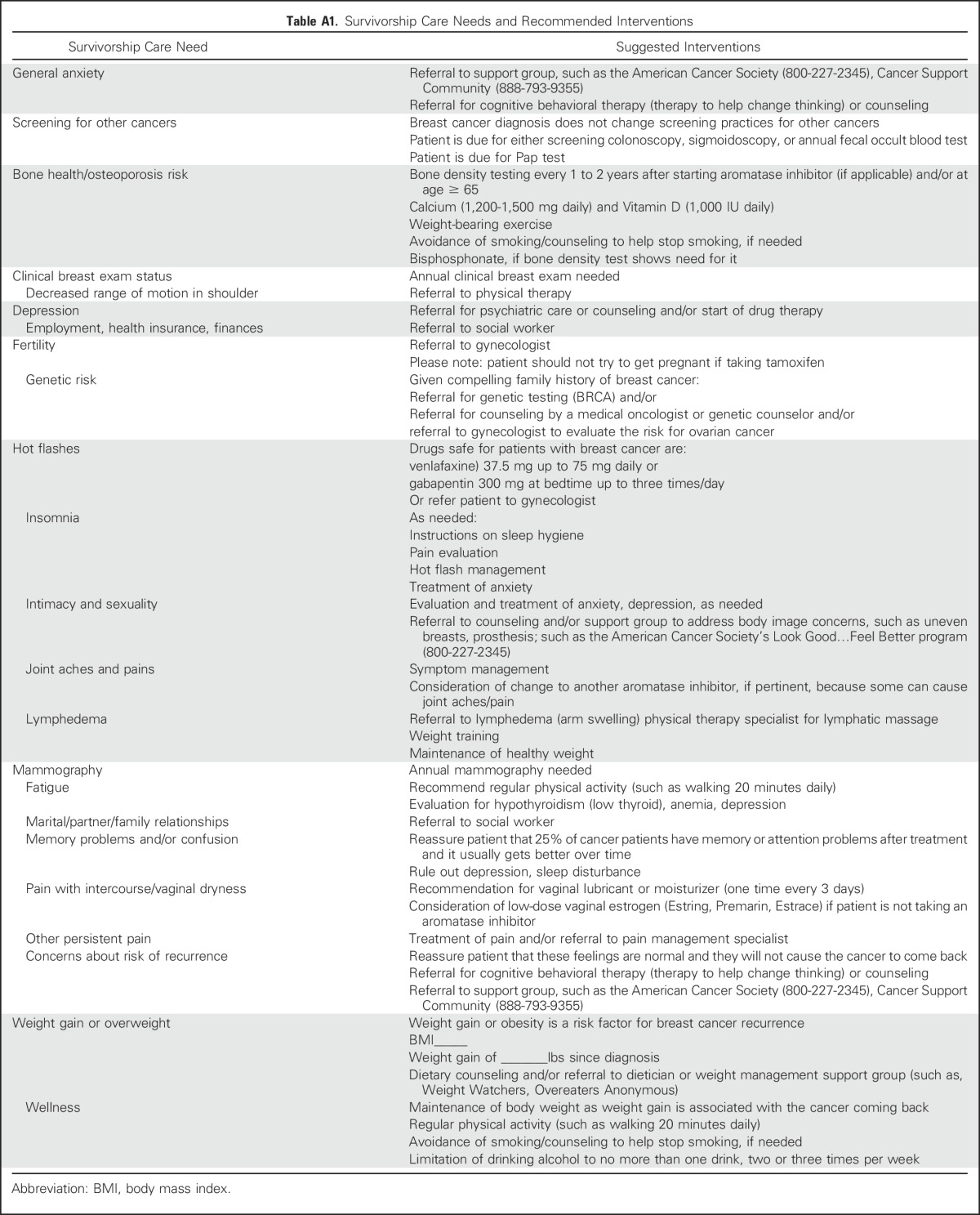

The primary outcome was physician implementation of specific recommendations for each survivorship care need identified for each participant at the baseline interview by patient report. Implementation was cummulatively assessed across 12 months of follow-up. Survivorship care needs were categorized into 23 areas (Table 1), and the total number for each participant was calculated by summing all the baseline needs. Appendix Table A1 (online only) lists the recommendations made to physicians to address specific care needs.

All study participants were interviewed by telephone quarterly to determine whether any of their physicians had implemented a recommendation for a previously identified need (eg, management of hot flashes with a medication) and whether the patient had followed/taken action for these recommendations. We assigned 1 point for each need addressed by the physician(s), with an implementation score constructed for each woman by first summing the number of needs addressed, then dividing by the number of total survivorship care needs, then multiplying by 100. The physician implementation score ranged from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating greater physician implementation of recommended care.

Secondary outcomes were patient adherence to recommended survivorship care up to the 12-month interview and scores on the Short Form (SF-12) Health Survey,20 at baseline and 12 months, to assess physical and mental health change during the study. Calculation of the patient adherence score was similar to the physician implementation score described previously.

In the intervention group only, at 12 months, we asked whether participants followed through with any of the recommended care, whether the TSSP provided more information than their own providers or more information than they found on their own, and whether the TSSPs improved communication with their providers.

Data Analyses

Analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive summary statistics were prepared for demographic and clinical characteristics and scores on the SF-12. We used χ2 (or Fisher exact) tests and t tests to compare baseline differences between the intervention and control groups.

An intention-to-treat approach was used for the primary analysis comparing the two groups. A two-group t test was used to compare the difference in the primary outcome, physician implementation of recommended survivorship care, measured at the end of the study (unadjusted analysis). None of the participants had missing values in the primary outcome. An adjusted multiple linear regression was conducted to assess whether there was still a significant intervention effect on the primary outcome when we adjusted for the prespecified factors of interest (eg, demographic and clinical characteristics) and to evaluate other potential factors that were associated with physician implementation and patient adherence. Model covariables included group indicator (intervention and control); demographic characteristics (age, ethnicity, education, and marital status); comorbidity (any v none); stage (invasive v noninvasive); having a usual source of care (yes v no); and three baseline preselected scales: Knowledge of Survivorship Issues, PEPPI, and Satisfaction With Care and Information. Other covariables (fixed-effects) included total number of care needs at baseline (because of imbalance between the two groups), type of care needed (indicators of the top 10 care needs), and study site (to account for the clustering structure). The same regression model was used to assess the intervention effect on patient adherence to recommended survivorship care at the end of study.

Linear mixed-effects regression models were used to assess whether the improvement in SF-12 scores and PEPPI were significantly different between the intervention and control groups at the end of the study. Models also included age as a fixed effect and a participant-level random effect to account for correlation among repeated observations per participant. The percentage of participants with missing SF-12 scores (8.7% v 3.8% for control v intervention) or PEPPI (9.5% v 5.6%, respectively) were similar between two groups. Subgroup analyses assessed ethnic group differences in the following binary perception measures among the participants receiving TSSP using χ2 (Fisher exact) tests: whether the participants followed through with any recommended care, whether the TSSP provided more information than their providers or more information than they found on their own, and whether the TSSP improved communication with their providers.

The sample size and power calculation were based on the primary outcome, physician recommendation implementation. The study protocol assumed an evaluable sample of least 350 subjects (175 per group) to provide 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.3 (ie, mean difference, 9.9; SD, 33), using a two-group t test with a .05 two-sided significance. However, we were not able to achieve the target enrollment because of unanticipated delays. The final sample size consisted of an evaluable sample of 212 patients (107 in the intervention group and 105 in the control group). The observed effect size of the primary outcome was 0.395, which was larger than planned. Differences in the primary analysis from the original study protocol are described in Appendix 3 (online only).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics and Baseline Findings

Figure 2 shows the study recruitment, enrollment, randomization, and follow-up flow. Table 2 describes the 212 eligible randomly assigned women by study group. No statistically significant differences in sample characteristics were found between the intervention and control groups, with both groups being an average of 53 years old, having similar educational backgrounds, and being 72% Latina. Fewer than one third in both groups were employed, and more than 70% of women in both groups reported poor/fair health status, with no differences in comorbidity, stage, or self-reported well-being. The mean SF-12 scores were well below the national norms of 50 in both groups. The average number of survivorship care needs was 5.4 (median, 5; range, 1-17), with significantly more survivorship care needs in the control group on average than the intervention group (6.5 v 4.3; P < .001). There were comparable levels of knowledge of survivorship issues, PEPPI, and satisfaction with care and information.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of the TSSP Baseline Sample (N = 212)

Table 3 lists the top 10 survivorship care needs identified. Weight gain or being overweight was first, with 82% of the sample endorsing this concern. Approximately half the sample reported concerns about risk of recurrence. Depression and insomnia were reported among approximately 40% of the sample. Weight gain or overweight and concern about recurrence were the top two needs for both groups.

Table 3.

Top 10 Patients’ Survivorship Care Needs Identified in TSSPs

Study Outcomes

The mean physician implementation score for TSSP recommendations was significantly greater for the intervention group (60.8 ± 32.6; median, 66.7; interquartile range, 50-85.7) than for the control group (48.6 ± 29.1; median, 50; interquartile range, 26.8-66.7; unadjusted P = .005). The mean patient adherence score was greater for the intervention group (55.7 ± 29.2) than for the control group (48.7 ± 26.8), but was not statistically significant (P = .07). Results from the adjusted multiple linear regressions for physician implementation and patient adherence to recommended survivorship care (Table 4) showed a significant intervention effect on physician implementation (estimated difference, 16.0 ± 5.34; P = .003), but not on patient adherence. Physicians were more likely to implement recommended survivorship care when participants were more satisfied with care and information (coefficient, 5.22 ± 2.22; P = .02). Being married or partnered (−11.8 ± 4.04; P = .004) or older age (−0.52 ± 0.24; P = .028) was negatively associated with patient adherence to recommended survivorship care. Type of care need, specifically, weight gain/overweight, was significantly associated with greater patient adherence (22.3 ± 5.02; P < .001), but hot flashes were inversely associated with greater patient adherence (−12.7 ± 4.70; P = .008). Similar results were found using a logit transformation of the primary outcome. Adjusted analyses revealed no significant differences in improvement of SF-12 scores and PEPPI from baseline to 12 months between groups (data not shown).

Table 4.

Regressions for Physician Implementation and Patient Adherence

In a subset analysis within the intervention group, Latinas were more likely to report following recommended care than non-Latinas (80.6% v 45.8%, respectively; P = .001) and to agree that the care plan provided more information than their provider (96.0% v 72.0%; P = .002), provided new information they had not previously found on their own (97.3% v 68.0%; P = .001), and improved communication with their doctors (97.1% v 73.7%; P = .005).

DISCUSSION

We believe that this is the first RCT of TSSPs to show a significant positive impact of their use on an important clinical outcome, that is, physician implementation of recommended breast cancer survivorship care. The study intervention differed from those in previous RCTs in that it was coupled with a nurse counseling session, outside the health care setting, and included patient empowerment, which may have been particularly effective in this low-income Latina population. The TSSPs were provided in Spanish when appropriate, and this may have enhanced an effect. Latinos have been shown to have poorer communication with their providers,21 and we hypothesized that Latinas within the intervention group were more likely to have benefited through their increased perception that the TSSP improved communication with their doctors.

The intervention did not have an impact on PEPPI, suggesting that our intervention was inadequate in that regard. However, this finding may be explained by the fact that the intervention was specifically aimed at the patient’s next encounter with her primary cancer provider (Appendix 2), whereas PEPPI measures self-efficacy with physicians in general. Furthermore, PEPPI was measured 1 year after the intervention, and a 1-hour-long intervention may be insufficient to sustain a long-term impact.

Interestingly, being married or partnered had a negative effect on patient adherence to survivorship care recommendations. The findings about the relationship between adherence and marital status have been inconsistent in previous research, at least with respect to adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy.22-24 If this negative relationship is replicated by others, then further investigation of the mechanism is warranted so that relevant interventions for partnered women can be developed. Future interventions may need to target patient-family dyads.

Satisfaction With Care and Information was positively related to physician implementation of recommendations, perhaps reflecting the direct impact of a more positive relationship with physicians. Lastly, the total number of survivorship care needs did not deter physicians from implementing recommended survivorship care, nor did the total number of care needs affect patient adherence in the adjusted regression models.

Limitations of this study include participant recruitment from two Los Angeles County public hospitals, thereby limiting external generalizability to low-income breast cancer survivors as a whole. Furthermore, the Latina population in Los Angeles County is primarily Mexican American and may not be generalizable to other US Latinas. Another limitation is the use of a specialized research nurse, with intervention delivery at a remote site outside of the patients’ treatment setting, which was implemented as proof of principle and may not be feasible in the clinical setting. Also, the measure of physician implementation was by patient report, which could bias the results to the null, because physicians may have implemented survivorship care, of which the patient was not aware. In addition, all 23 survivorship care needs were equally weighted, and this may be a limitation because they do not all relate equally to quality of life, recurrence, or survivorship outcomes. Finally, the interviewers were not blinded to treatment group after the baseline interview (relevant for the 12-month interview only) because the intervention group participants were asked additional intervention-specific questions. However, the interviewers used standardized questions with closed-ended responses to which they were trained to strictly adhere. Of note, provision of TSSPs is becoming the standard of care and future trials should compare receipt of TSSPs to receipt of TSSPs plus a counseling intervention.

In conclusion, this is the first RCT of TSSPs to show a significant clinical benefit, that is, increased physician implementation of recommended survivorship care. Whether these findings are unique to this vulnerable population and their physicians or whether this type of intervention would be more generalizable, warrants further investigation in other cancer survivor samples and settings. In addition, because quality of life scores (SF-12 mental and physical health) were below population norms, and no change in these scores was detected as a result of the intervention, future TSSP intervention designs should focus on quality of life more intensely. Finally, future studies should include the impact of such interventions on breast cancer symptoms and examine whether greater benefits would accrue if the interventions were delivered at the point of transitioning off active treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors express their appreciation to Christine Dauphine at Harbor-University of California at Los Angeles Medical Center and Debu Tripathy, then at Los Angeles County and University of Southern California Medical Center, now at University of Texas Anderson Cancer Center, for their invaluable help in identifying potential participants for this study. We also thank Judith Galvan, our Research Nurse, and Jeanette L. Gibbon, our Project Director, for their outstanding work in implementing this study, and Shannon Jason for her help with preparation of the manuscript.

Appendix

Appendix 1

Treatment Summary and Survivorship Care Plan Development and Construction.

The adaptation of the treatment summary and survivorship care plans (TSSPs) was a result of six focus groups of breast cancer survivors recruited from Harbor-University of California at Los Angeles Medical Center, three Spanish-speaking groups, and three English-speaking groups consisting of eight women each. These low-income breast cancer survivors were shown and reviewed mock-ups of TSSPs with graphics and provided input ono the design and understandability of the TSSPs.

The TSSPs for this study had three sections: (1) a survivorship care plan with individualized and general recommendations for follow-up breast cancer care for both the patient and all physicians involved in the patient’s care, (2) the breast cancer treatment summary, including surgery type, chemotherapy received, and radiation therapy received, and (3) a list of local and national patient resources. Table 1 shows the components and contents of the first two sections of the TSSP. A nurse developed the TSSP from information abstracted from three sources—medical records (for the treatment summary), information collected from a brief pre-TSSP development telephone call with each participant in the intervention group to help identify chief patient needs and concerns, and the baseline interview that comprehensively solicited individual survivorship needs and concerns.

Appendix 2

Nurse Counseling Session and Process Assessment.

One month after the baseline interview, the nurse scheduled a 1-hour session with each intervention participant at the University of California at Los Angeles to review the treatment summary and survivorship care plan (TSSP). The nurse conducted a brief precounseling call with each intervention group participant, during which time she reviewed the patient’s list of needs and concerns on the basis of the baseline questionnaire. The patient was asked to name the three needs and concerns that were more bothersome and rank them from 1 to 3. These were the needs and concerns that the nurse focused on during the counseling session. During the counseling session, the nurse explained to the patient the contents and sections of the TSSP and stopped after each section to answer any questions the patient had. The nurse emphasized the section containing recommendations for follow-up with the patient’s physicians. She included dates of service if the patient had a colonoscopy, Pap smears, and a pelvic exam, and/or mammogram; if these had not be done at the appropriate intervals, the nurse coached the patient to point this out to her physicians and flagged the pertinent page of the TSSP recommendations. To increase patients’ empowerment in communicating with their physicians, an important predictor of many outcomes for low-income breast cancer patients,16,17,18,19 participants were coached in writing down their three most important questions, and role playing discussing them with their physicians, as well as role playing asking that the survivorship care recommendations be implemented. Of note, the nurse often found patients to be anxious, stressed, and dubious about the counseling session; therefore, she focused on making them feel comfortable and at ease, using humor as appropriate, before even attempting to explain the contents of the TSSP. Most patients left the session pleased and much more comfortable with their breast cancer–related information all put together in the TSSP. The participant was encouraged to make an appointment with the physician most involved with her cancer care to discuss the TSSP and her question list, and to take a copy of her TSSP to future visits with other providers. A cover letter and two copies of the TSSP were mailed to the chiefs of the breast clinics at the two study sites, to be scanned into or attached to the patient's medical records. Patients were given extra copies to take to future visits with providers.

There was a process assessment of the nurse counseling component of the intervention. Our survivorship care nurse was trained by an oncologist (our senior author, P.A.G.) and her nurse practitioner specializing in survivorship care at the University of California at Los Angeles. The nurse practitioner conducted two of the sessions with our participants with our study nurse present to demonstrate appropriate techniques and then the nurse practitioner supervised a third counseling session with our study nurse. Five subsequent counseling sessions by our study nurse were recorded and sent to the nurse practitioner for review and feedback about the content and fidelity with which the materials were delivered. Initial care plans were sent to P.A.G and her nurse practitioner for feedback and review, as well.

Appendix 3

Differences in the Primary Analysis From the Study Protocol.

Differences in the primary analyses between the original protocol and the article are summarized. First, the primary end point in the article is defined as physician implementation of recommendations for 23 different survivorship care needs determined at the baseline visit, whereas the end point in the protocol was defined as implementation of recommendations for six different survivorship care needs. Second, the primary analysis in the article is a multiple regression model for physician implementation with site of care as fixed effects (to account for site-level clustering structure), whereas that in the original study protocol analysis plan, a linear mixed-effects model with site-level and provider-level random effects for physician implementation was used. Third, the ethnicity-stratified randomization (Latina v non-Latina) was not originally planned in the study protocol because we did not anticipate such a large majority of Latina participants (72.6%).

Table A1.

Survivorship Care Needs and Recommended Interventions

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute Grant No. 1R01CA140481-01A1.

Presented at the ASCO Cancer Survivorship Symposium: Advancing Care and Research, A Primary Care and Oncology Collaboration, San Francisco, CA, January 15-16, 2016.

Clinical trial information: NCT01627366.

Listen to the podcast by Dr Bickell at ascopubs.org/jco/podcasts

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Rose C. Maly, Patricia A. Ganz

Collection and assembly of data: Rose C. Maly, Li-Jung Liang, Yihang Liu

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Randomized Controlled Trial of Survivorship Care Plans Among Low-Income, Predominantly Latina Breast Cancer Survivors

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Rose C. Maly

No relationship to disclose

Li-Jung Liang

No relationship to disclose

Yihang Liu

Employment: Optum

Jennifer J. Griggs

No relationship to disclose

Patricia A. Ganz

Leadership: Intrinsic LifeSciences (I)

Stock or Other Ownership: Xenon Pharma (I), Intrinsic LifeSciences (I), Silarus Therapeutics (I), Merganser Biotech (I), Teva, Novartis, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Abbott Laboratories

Honoraria: Vifor Pharma (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Keryx (I), Merganser Biotech (I), Silarus Therapeutics (I), InformedDNA, Eli Lilly

Research Funding: Keryx (I)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Related to iron metabolism and the anemia of chronic disease (I), Up-to-Date royalties for section editor on survivorship

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Intrinsic LifeSciences (I), Keryx (I)

REFERENCES

- 1.Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: Prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:1029–1036. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:252–271. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. (NIH NCI reference) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al (eds): SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2005. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2005/

- 5.Mayer DK, Shapiro CL, Jacobson P, et al. Assuring quality cancer survivorship care: We’ve only just begun. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2015:e583–e591. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2015.35.e583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewitt M, Ganz PA: Rapporteurs. Implementing Cancer Survivorship Care Planning: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G, et al. Evaluating survivorship care plans: Results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4755–4762. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hershman DL, Greenlee H, Awad D, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a clinic-based survivorship intervention following adjuvant therapy in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:795–806. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2486-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brothers BM, Easley A, Salani R, et al. Do survivorship care plans impact patients’ evaluations of care? A randomized evaluation with gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129:554–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Palmer SC, Stricker CT, DeMichele AM, et al. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3646-3. The use of a patient-reported outcome questionnaire to assess cancer survivorship concerns and psychosocial outcomes among recent survivors. Support Care Cancer [epub ahead of print on February 23, 2017] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maly RC, Frank JC, Marshall GN, et al. Perceived efficacy in patient-physician interactions (PEPPI): Validation of an instrument in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:889–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griggs JJ, Sorbero MES, Mallinger JB, et al. Vitality, mental health, and satisfaction with information after breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, et al. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34:73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganz PA, Hahn EE. Implementing a survivorship care plan for patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:759–767. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earle CC. Failing to plan is planning to fail: Improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5112–5116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Journey Forward: Cancer Care Plan Builder. http://www.journeyforward.org/professionals/survivorship-care-plan-builder

- 16.Maly RC, Stein JA, Umezawa Y, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in breast cancer outcomes among older patients: Effects of physician communication and patient empowerment. Health Psychol. 2008;27:728–736. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maly RC, Liu Y, Leake B, et al. Treatment-related symptoms among underserved women with breast cancer: The impact of physician-patient communication. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:707–716. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0418-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maly RC, Umezawa Y, Leake B, et al. Determinants of participation in treatment decision-making by older breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;85:201–209. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000025408.46234.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maly RC, Leake B, Silliman RA. Breast cancer treatment in older women: Impact of the patient-physician interaction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1138–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aseltine RH, Jr., Sabina A, Barclay G, et al. Variation in patient-provider communication by patient’s race and ethnicity, provider type, and continuity in and site of care: An analysis of data from the Connecticut Health Care Survey. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:2050312115625162. doi: 10.1177/2050312115625162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brito C, Portela MC, de Vasconcellos MTL. Adherence to hormone therapy among women with breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:397. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tinari N, Fanizza C, Romero M, et al. Identification of subgroups of early breast cancer patients at high risk of nonadherence to adjuvant hormone therapy: Results of an Italian survey. Clin Breast Cancer. 2015;15:e131–e137. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Malin JL, Diamant AL, et al. Adherence to adjuvant hormone therapy in low-income women with breast cancer: The role of provider-patient communication. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:829–836. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2387-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]