Abstract

Background: Heart failure (HF) is a chronic progressive illness associated with physical and psychological burdens, high morbidity, mortality, and healthcare utilization. Palliative care is interdisciplinary care that aims to relieve suffering and improve quality of life for persons with serious illness and their families. It is offered simultaneously with disease-oriented care, unlike hospice or end-of-life care. Despite the demonstrated benefits of palliative care in other populations, evidence for palliative care in the HF population is limited.

Objective: The objective of this article is to describe the current evidence and the gaps in the evidence that will need to be improved to demonstrate the benefits of integrating palliative care into the care of patients with advanced HF and their family caregivers.

Methods: We reviewed the literature to examine the state of the science and to identify gaps in palliative care integration for persons with HF and their families. We then convened an interdisciplinary working group at an NIH/NPCRC sponsored workshop to review the evidence base and develop a research agenda to address these gaps.

Results: We identified four key research priorities to improve palliative care for patients with HF and their families: (1) to better understand patients' uncontrolled symptoms, (2) to better characterize and address the needs of the caregivers of advanced HF patients, (3) to improve patient and family understanding of HF disease trajectory and the importance of advance care planning, and (4) to determine the best models of palliative care, including models for those who want to continue life-prolonging therapies.

Conclusions: The goal of this research agenda is to motivate patient, provider, policy, and payor stakeholders, including funders, to identify the key research topics that have the potential to improve the quality of care for patients with HF and their families.

Keywords: : heart failure, health services, palliative care in heart failure, quality and outcomes, uncontrolled symptoms

Scope of the Problem

Heart failure (HF) is a disease of older adults; nearly 80% of inpatients with advanced HF are older than 65 years.1–6 HF is a chronic progressive illness marked by acute potentially life-threatening deteriorations superimposed on gradual functional decline.7 Deterioration is associated with hospital admissions and intensive treatment8–11; for patients with advanced HF, the 1-year freedom from hospitalization or death is only 33%.12,13 Approximately 80% of HF patients are hospitalized in the last 6 months of life.14 In addition, the care for these patients is costly. Medicare costs for HF patients exceed all other diagnoses at $32 billion per year.1–6 By 2030, the total cost of HF care is projected to reach $69.7 billion.15 For patients with HF, the prevalence of poor quality of life (QOL), the untreated HF symptom burden (dyspnea, pain, anxiety, and depression),16 and the high rate of acute care services use in the 30 days before death (emergency department [ED] visits: 64% vs. 39%, hospitalizations: 60% vs. 45%, and ICU admissions: 19% vs. 7%)17 exceeds that of cancer.16,18–21

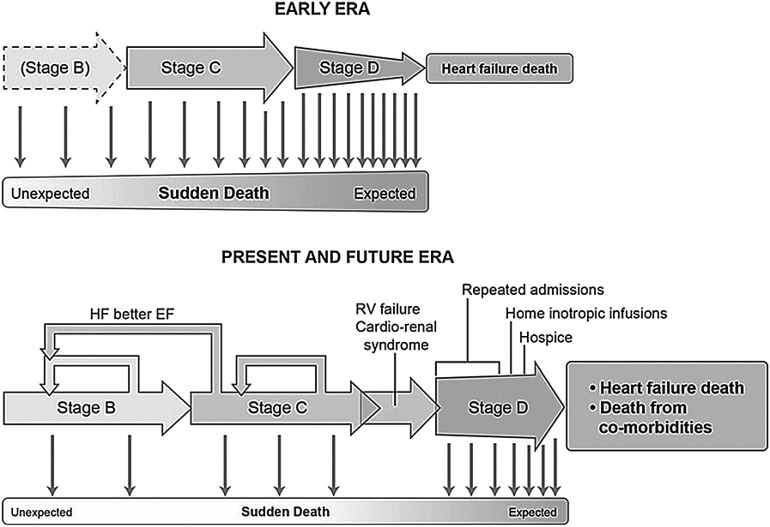

Optimal treatment for HF can vary greatly based on whether patients have preserved or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. The prevalence and complexity of late-stage HF is, in part, the result of the effectiveness of HF therapies for reduced ejection fraction—in the past, death previously prevented progression to right-sided HF and cardiorenal syndrome. Effective neurohormonal antagonist therapies and implantable defibrillators have decreased sudden death, and, in turn, these therapies have made disease progression more complicated and less predictable (Fig. 1).22 Unlike many advanced illnesses, the HF interventions that most effectively treat many symptoms are the same therapies that prolong life.12,23–28 The best treatment for common HF symptoms is the treatment of HF itself. In late-stage disease, diuretics and in some cases vasodilators are commonly used to reduce symptoms of congestion. For some patients, relief of congestion is facilitated by improving cardiac output, for which our only current therapy is ongoing intravenous inotropic therapy, which requires an indwelling venous catheter and high daily costs. Most patients are not eligible for advanced therapies like mechanical circulatory support devices or heart transplantation.

FIG. 1.

Changing journeys with heart failure (HF) reduced ejection fraction (EF).22 This diagram contrasts the HF disease stages between the early days of heart transplantation and the current era. Because our modern therapies can prevent or delay disease progression, many patients in stage B and stage C HF may remain stable for many years. Although these patients are living longer, these modern therapies may also allow for a prolongation of these patients' inevitable deaths, which may include suffering.

Persons with serious illnesses such as HF and their families are eligible for palliative care, a form of interdisciplinary care that aims to relieve suffering and improve QOL. Unlike hospice or end-of-life care, palliative care is offered simultaneously with disease-oriented medical treatments. Despite the demonstrated benefits of palliative care in cancer, evidence for HF is sparse.29–31 Unlike cancer, the unpredictable nature of HF exacerbations, the increasing availability of expensive advanced therapies, the limited number of heart donors, the uncertainty of outcomes from invasive and intensive therapies, and a bias toward full cure versus focusing on improving QOL make the integration of palliative care more challenging in HF.12,23–28 Improving integration of palliative care into HF care will require discovery, clinical dissemination, advanced study designs, instruments, analytics, education, and dedicated research funding.

With a goal of delineating research, practice, and policy priorities, a working group of palliative care and HF experts gathered in Birmingham, Alabama, for a symposium entitled: Improving Palliative Care for Patients with Heart Failure and Family Caregivers: Creating an Agenda for Research and Clinical Priorities. The symposium was supported by The John A. Hartford Foundation, the National Palliative Care Research Center, Mount Sinai's Claude Pepper Older American Independence Center, and University of Alabama at Birmingham Centers for Comprehensive Cardiovascular Care and Palliative and Supportive Care. Using a nominal group technique (NGT),32 a structured ranking process of important issues, we conducted three conference calls to create a ranked list of priorities (Table 1). Ten cardiology and six palliative medicine experts participated.

Table 1.

Nominal Group Technique Ranked Responses About Integration of Palliative Care and Heart Failure

| What are the challenges that you face in the care of your patients with HF? How can palliative care help? | Symptom management |

| Goals of care | |

| Improved cross-training (HF training for palliative care clinicians and palliative care training for HF clinicians) | |

| Prognostic uncertainty | |

| Myths about palliative care (only end-of-life care) | |

| Optimal timing for palliative care | |

| Caregiver burden | |

| What evidence would influence you and your colleagues about the role of palliative care in caring for your patients with HF? | Translation of guidelines to practice |

| Recognize patient medical complexity | |

| Mandated guidelines | |

| Better symptom evidence | |

| Consensus on care model | |

| What models have been successful in integrating palliative care into the care of patients with HF? | Triggered consults |

| Palliative care embedded clinic model | |

| Primary palliative care models of training nurse practitioners within the HF clinic | |

| Palliative home care | |

| Trust and relationship building between palliative care and HF clinicians |

This table represents the results (ranked in order of priority) from a nominal group technique exercise that used a series of questions asked to an interdisciplinary group of key stakeholders representing national leaders in the fields of HF and palliative care.

HF, heart failure.

The highest ranked responses from the NGT calls were used to set the two-day symposium agenda. The agenda for the symposium in Alabama centered around a series of trigger talks and working groups on four distinct topics as follows: (1) Current Research Examining the Integration of Palliative Care and HF, (2) Clinical Models Integrating Palliative Care into the Care of Patients with HF, (3) Guidelines, Quality Metrics, and Policy, and (4) Development of an Action Plan and Commitment to Next Steps. From the symposium, the IMPACT-HF2 (Improve Palliative Care Therapies for Patients with Heart Failure and Their Families) working group was developed; this group continues to work to advance the research, clinical models, and policy priorities at the intersection of palliative care and HF.

The symposium results were presented at the two-day National Institutes of Health/National Palliative Care Research Center (NIH/NPCRC) workshop, “Advancing and Extending a Palliative Care Research Agenda in the Specialties” in Bethesda, Maryland, in August 2016. This conference brought together thought leaders from chronic disease and palliative care specialties to outline the current research base and knowledge gaps and to create a consensus on the research priorities that were disease specific and crosscutting. The purpose of this article is to summarize the current research gaps and priorities at the intersection of palliative care and HF care that were brought forth from these two meetings.

Mandates for integrating palliative care in HF outpace the research base

The American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF),10 American Heart Association (AHA),33 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT),34 Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA),35 and Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS)36 encourage the incorporation of palliative care into the HF care (Table 2). The Joint Commission (TJC)37 and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)38 also require palliative care to be part of the team caring for patients with a ventricular assist device (VAD) as destination therapy (DT). Despite these multiple guidelines, there is little NIH funding support for HF-related palliative care research. A recent review of HF literature, conferences, and funding found that less than 1% of publications and less than 2% of conference sessions relate to palliative care. Furthermore, of the $45 billion NIH budget directed to HF research, only $14 million (0.03%) were related to palliative care.39

Table 2.

Summary of Key Heart Failure Guidelines Advocating for the Integration of Palliative Care

| Guideline title | Sponsoring society/organization | Key palliative care domains covered in document | Notable specific mentions of palliative care |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 CCS HF Management Guidelines Update36 | The CCS | The provision of palliative care to patients with HF should be based on a thorough assessment of needs and symptoms, rather than on individual estimate of remaining life expectancy | CCS adapted WHO definition of palliative care: “Palliative care is a patient-centered and family-centered approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual. It is applicable early, as well as later, in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, including but not limited to in the setting of heart failure, oral pharmacotherapy, surgery, implantable device therapy, hemofiltration or dialysis, the use of intravenous inotropic agents, and ventricular assist devices.” |

| Clinicians looking after HF patients should initiate and facilitate regular discussions with patients and family regarding advance care planning | |||

| In the presence of persistent advanced HF symptoms (NYHA III–IV) despite optimal therapy be confirmed, offer palliative care ideally by an interdisciplinary team with expertise in HF management, to ensure appropriate HF management strategies have been considered and optimized, in the context of patient goals and comorbidities. | |||

| 2012 AHA Scientific Statement “Decision Making in Advanced HF”33 | American Heart Association | Recommend referral to palliative care for assistance with difficult decision making, symptom management in advanced disease, and caregiver support even as patients continue to receive disease-modifying therapies | “…[I]t is important to integrate palliative care into the care of patients with HF before they enter stage D. Even as patients are being considered for transplantation, mechanical circulatory support, or trials of novel therapeutics and pharmacological agents, palliative care can be increasingly integrated to ensure that patients' symptoms are appropriately controlled and that patients understand the nature of these interventions, as well as the full complement of alternative therapies.” |

| The use of palliative care services should not be considered equivalent to the withdrawal of disease-modifying therapies | |||

| Highly skilled communication is essential to shared decision making | |||

| 2013 Guidelines for the Management of HF10 | American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines | Comprehensive palliative care for HF delivered by clinicians should include expert symptom assessment and management | “Throughout the hospitalization as appropriate, before hospital discharge, at the first postdischarge visit, and in subsequent follow-up visits, the following should be addressed…consideration for palliative care or hospice care in selected patients.” |

| 2013 ISHLT Guidelines for Mechanical Circulatory Support34 | International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation | Palliative care consultation should be a component of the treatment of end-stage HF during the evaluation phase for mechanical circulatory support | “Palliative care consultation should be a component of the treatment of end-stage heart failure during the evaluation phase for MCS. In addition to symptom management, goals and preferences for end of life should be discussed with patients receiving MCS as DT.” |

| Goals and preferences for end-of-life care should be discussed with patients receiving mechanical circulatory support as destination therapy | “A multidisciplinary team led cooperatively by cardiac surgeons and cardiologists and composed of subspecialists (i.e., palliative care, psychiatry, and others as needed) …is indicated for the in-hospital management of MCS patients.” | ||

| The 2015 Statement from the HFSA Guidelines Committee on Advanced (Stage D) HF35 | Heart Failure Society of America | Incorporation of palliative care and hospice care into the care plans for patients with advanced HF | “The optimal approach [to advance care planning] involves shared decision making, where options for medical care are discussed with acknowledgment and legitimization of the complex trade-offs behind each choice…Involving palliative care specialists can facilitate the [advance care planning] conversation and, for patients who prioritize comfort over longevity, help to ensure access to necessary resources for enactment of a less aggressive path. Ideally, such conversations should be initiated before the transition to terminal stages of HF…” |

| Specifying that decision making should involve incorporating the patient's wishes for survival versus quality of life. | |||

| 2015 HF Management in Skilled Nursing Facilities87 | American Heart Association and Heart Failure Society of America | Advance care planning | “Decisions to balance palliative and disease-directed treatments may include withholding treatments of marginal potential efficacy, withdrawal decisions after treatments have been started, hospice referral for palliation, and determining whether end-of-life care will occur in the SNF or elsewhere. End-of-life care plan quality measures may be very important considerations for HF patients and potentially of value for improving patterns of care… These measures should be strongly considered for application in HF patients in SNFs.” |

| Symptom management | |||

| End-of-life care | |||

| Hospice | |||

| Transitions | |||

| Care management | |||

| Device management | |||

| Caregiver support | |||

| JCAHO Advanced Certification Program for VAD for Destination Therapy37 | Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Hospital Organizations | Revised requirements for the DSC advanced certification program for VAD for Destination Therapy | “The Joint Commission announced revisions to requirements for the DSC advanced certification program for VAD for Destination Therapy… to add a palliative care representative to the core interdisciplinary team.” |

| Specifically added a requirement to have a palliative care representative to the core interdisciplinary team. | |||

| CMS Memorandum for VADs for Bridge-to-Transplant and Destination Therapy38 | Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services | Mandated the inclusion of palliative care specialists in the multidisciplinary team of medical professionals caring for beneficiaries receiving VADs for DT. | “Beneficiaries receiving VADs for DT must be managed by an explicitly identified cohesive multidisciplinary team of medical professionals with the appropriate qualifications, training, and experience. The team embodies collaboration and dedication across medical specialties to offer optimal patient-centered care. Collectively, the team must ensure that patients and caregivers have the knowledge and support necessary to participate in shared decision-making and to provide appropriate informed consent. The team members must be based at the facility and must include individuals with experience working with patients before and after placement of a VAD.” |

| “The team must include a palliative care specialist.” |

AHA, American Heart Association; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; DSC, disease-specific care; DT, destination therapy; HFSA, Heart Failure Society of America; ISHLT, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; VAD, ventricular assist device; WHO, World Health Organization.

Summary of Current Evidence

The current state of the science for palliative care in HF is limited, although the evidence that does exist demonstrates that further research is required to:

1. Better understand advanced HF patients' limiting symptoms and focus treatment on their relief. Patients with HF experience burdensome HF symptoms,40 including pain, breathlessness, anxiety, fatigue, and depression,41 which can last for weeks to months42 with a prevalence16 exceeding that of many types of cancer.18–21 However, evidence for best practices in advanced HF symptom management is limited.

2. Better characterize and address the needs of the caregivers of advanced HF patients. HF patients' informal caregivers43–45 (e.g., spouse, children, other family members, and close friends) bear a large responsibility for HF caregiving hours and cost46 and are at high risk of anxiety, depression, poor QOL, complicated grief, and great financial burden. The various responsibilities managed by the informal caregivers of HF patients43–45 amount to significant number of caregiving hours and cost.46

3. Improve patient and family understanding of HF disease trajectory and importance of advance care planning: Although HF is a progressive disease, few patients actively participate in treatment decisions, advance care planning, or complete advance directives, and those that do, do so close to death.47–50 For example, decision making around initiation of many life-prolonging cardiac devices, like implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and mechanical circulatory support devices, rarely includes consideration of device deactivation.10,51–54 Despite benefits of goals of care discussions across a broad range of diseases, physicians are less likely to have these types of discussions with HF patients than those with other advanced illnesses.55–66 Patients are often unaware that their illness is life limiting,67 and clinicians are unaware of patients' treatment preferences.9,48 Multiple models for improving advance care planning and preparedness planning exist;68,69 however, few are tailored to patients with HF and their families.

4. Determine the best models of palliative care, including models for those who want to continue life-prolonging therapies: The models that exist for specialist palliative care for HF focus on triggers that indicate patients have unmet needs through the use of specific clinical criteria are expanding nationally. For example, at the University of North Carolina, all patients who are being evaluated for destination therapy-left ventricular assist devices (DT-LVADs) are seen by palliative care consultation services. At St. Luke's Mid America Heart Institute, all candidates for LVAD are automatically seen by palliative care specialists, and all HF inpatients have at least one palliative care consult per year. At Brigham and Women's Hospital, all patients with DT-LVAD receive a palliative care consult, referred to as “supportive cardiology.” In addition to consulting on all patients evaluated for LVAD, the University of Colorado palliative care team members participate in HF rounds on a weekly basis. At the University of Alabama, Birmingham, the ENABLE-HF70–72 (Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life Ends) randomized clinical trial is using a concurrent telehealth approach to reach rural and underserved minorities, through in-person palliative care consultation and patient and family caregiver phone coaching to encourage activation and communication and decision-making skill building.30

Currently, there are efforts to develop comanagement models for patients with advanced HF in the outpatient setting. One model that existed at the University of Washington Medical Center was a dedicated cardiology outpatient palliative care clinic providing initial evaluation and longitudinal follow-up for the VAD population. The model at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai includes a palliative care physician, embedded in the outpatient advanced HF practice, who sees patients longitudinally who are undergoing DT-LVAD evaluation and those with palliative care needs. When these patients are admitted to the hospital, the inpatient palliative care consultation team will follow them as needed. The University of Pittsburgh has a particularly innovative model that had its origins in an inpatient team that originally used triggers for consultation. These initial triggers resulted in a 20% increase of the overall palliative care consult volume for patients with HF. Based on the success of this trigger program, the team developed an outpatient HF-palliative care clinic in 2005. The hiring of a dedicated nurse practitioner allowed the palliative care team to bridge the gap between outpatient and inpatient palliative care services, and ultimately, helped several complex patients to avoid serial readmissions and die peacefully at home. Given the prevalence of HF, more research is needed about models of telehealth and telemonitoring to meet palliative care needs.73–76 Despite the growing evidence for specialist palliative care for patients with HF, there are little data on developing primary palliative care models77 tailored for HF. Finally, although more HF patients utilize hospice,14 patients with advanced HF enroll in hospice at lower rates and closer to death than those with cancer.17,78–80

Research Gaps and Priorities

Table 3 outlines the key research gaps, as well as the potential research topics and objectives that would help to advance the science of palliative care research for patients with advanced HF. The priorities are as follows:

Table 3.

Proposed Research Priorities and Sample Trial Designs for Improving the Science of Palliative Care for Patients with Advanced Heart Failure

| No. | Research priority | Study objective | Study setting | Sample | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | To better understand advanced HF patients' limiting symptoms and focus treatment on their relief | To better understand treatments (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) for symptoms of patients with advanced HF (pain, fatigue, anxiety, depression)—assess both improvement in symptoms but also tolerability of side effects and relationship to HF exacerbations | Academic and community/inpatient and outpatient | Stage C and D HF Patients | RCT of medications/treatments for symptoms, with detailed assessment of medication side effects (as applicable) |

| 2 | To better characterize and address the needs of the caregivers of advanced HF patients | To create interventions to improve caregiver burden and distress | Academic and community/inpatient and outpatient | Caregivers of patients with advanced HF | Cohort study to better elucidate needs and then interventions to improve burdens and increase caregiver activation |

| 3 | To improve patient and family understand of disease trajectory and importance of advance care planning | To create effective and timely communication techniques focused on advance care planning for patients with HF and their caregivers | Academic medical centers may be the place to begin this work | Stage C and D HF patients | Innovative RCTs of interventions to improve advance care planning, as well as determine effect of interventions on patient-centered outcomes |

| 4 | To determine the best models of palliative care, including models for those who want to continue life-prolonging therapies | To better understand the individual elements of a specialist palliative care intervention and determine the impact of each of these elements on outcomes important to clinicians, patients, and family caregivers. (i.e., what's in the palliative care syringe?) | Needed in both inpatient and outpatient settings, as the syringe might be different | Stage C and D HF patients | Cohort study or adaptive trial design with data collection designed to determine exposure to each of the individual elements conveyed in the delivery of specialty level palliative care |

| To determine effective models to empower and teach primary cardiology staff to better apply principles of palliative care in the domains of symptom management, communication, and psychosocial support | Outpatient academic and community settings | Clinicians caring for patients with HF: Physicians (HF specialists, general cardiologists, primary care); nurses (NP and RN); physician assistants, social work | Pre–post education intervention or RCT of intervention delivery | ||

| To determine the best models to deliver care to patients who may not want advanced therapies but also are not ready for hospice | Academic medical centers may be the place to begin this work | Patients with Stage D HF | Adaptive trial design using predetermined patient and family centered outcomes |

Studies should account for differences in terms of patients who may or may not be candidates for advanced therapies.

NP, nurse practioner; RCT, randomized control trial; RN, registered nurse.

1. Gap: To better understand advanced HF patients' limiting symptoms and focus treatment on their relief. Symptoms of HF, which are ameliorated by HF therapies (dyspnea, severe edema, and hepatic congestion), are distinct from symptoms common to many advanced diseases, such as pain, anxiety, and insomnia. This distinction in symptoms is common to HF and end-stage lung disease, but less applicable in cancer. In addition, fatigue, a prevalent symptom for patients with HF, has little evidence on targeted therapies. Priority: (1) To better understand treatments (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) for symptoms of patients with advanced HF (pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression) and (2) to assess both improvement in symptoms and function and also tolerability of side effects and relationship to HF exacerbations.

2. Gap: To better characterize and address the needs of the caregivers of advanced HF patients. Informal caregivers suffer greatly with this disease; care-taking responsibilities include assessing symptoms, administrating medications, assisting with managing advanced HF therapies and devices (e.g., mechanical circulatory support), partnering in complex health and medical decisions, and providing emotional support. Priority: (1) To better characterize the burdens of caregivers of patients with HF and (2) to test interventions to address these caregiver needs.

3. Gap: To improve patient and family understanding of the HF disease trajectory and the importance of advance care planning. Multiple models for improving advance care planning and preparedness planning exist; however, few are tailored to patients with HF and their families. In addition, there are a limited number of clinical models of how palliative care can be combined with other medical care for HF, and even those that have demonstrated effectiveness and improvements in patient care have not been able to demonstrate exactly which of the elements of palliative care are directly related to better outcomes.81 Without a more nuanced understanding of the impact of different aspects of palliative care, it will be difficult to export these models to other settings where the entire breadth of palliative care expertise may not be readily available. Priority: To create effective and timely communication techniques focused on advance care planning for patients with HF and their caregivers.

4. Gap: To determine the best models of palliative care, including models for those who want to continue life-prolonging therapies. Unfortunately, the limited number of clinical models in HF has not been well tested and even those that have demonstrated effectiveness and improvements in patient care have not been able to demonstrate exactly which of the elements of palliative care are directly related to better outcomes.82 Without a more nuanced understanding of the impact of different aspects of palliative care, it will be difficult to export these models to other settings where the entire breadth of palliative care expertise may not be readily available. In addition, no information exists to characterize how often patients classified objectively as facing imminent mortality seek to retain the option for life-sustaining interventions, because even advanced HF stages often associated with interludes of relative comfort and activity.

Furthermore, overcoming HF and palliative care integration research gaps is compounded by palliative care workforce deficits.82,83 There are no realistic estimates of the shortages of nurse practitioners specializing in palliative care. Therefore, it is unrealistic to provide full interdisciplinary specialist palliative care team consultations for all HF patients. Future research is needed to delineate how palliative care specialist and generalist physicians, nurses, social workers, and others who care for patients with HF can work together to provide high-quality palliative care to patients and family caregivers in need.

Care models must be tailored to patients' specific needs and disease stage. For example, the care models for patients wishing to pursue all life-prolonging treatments solely focused on comfort and those in an “in-between” or transitional stage will likely require different approaches. For example, patients in a transitional phase may wish to receive antibiotics for pneumonia, but decline craniotomy for intracranial hemorrhage or surgery to resect ischemic bowel. This transitional stage is the most complex because goals of care may be in flux due to periods of acceptable QOL that are interspersed with exacerbations and hospitalizations that may call into question if and when to begin to limit life-prolonging therapies. Evidence about patterns of hospice use to the HF population remains limited.84,85 Likewise, there are no interventions in the literature that are known to increase hospice utilization among patients with advanced HF. Priority: (1) To better understand the individual elements of a specialist palliative care intervention and determine the impact of each of these elements on outcomes important to clinicians, patients, and family caregivers. (i.e. what's in the palliative care syringe?); (2) to determine effective models to empower and teach primary cardiology staff to better apply principles of palliative care in the domains of symptom management, communication, and psychosocial support; (3) to determine the best models to deliver care to patients who may not want advanced therapies but also are not ready for hospice.

Conclusions

Solving these problems will involve innovative research studies across a variety of settings that incorporate new and novel methodologies. Study designs for interventions and education should engage patient and family caregiver stakeholders and clinicians representing the related specialties and disciplines. It is critical that research to fill these gaps account for and examine the disparities that exist for patients with HF and their families. First, research needs to account for the fact that these disparities are present on multiple levels.86 For patient and caregiver, disparities involve sociodemographics, illness severity, acculturation, health literacy, cultural beliefs, values, and preferences; for providers, they include knowledge, attitudes, bias, and communication; and for health systems, they include the context in which palliative care is provided, models of care, financials of palliative care services, and organizational culture. Next, interventions need to be developed to eliminate the disparities so that patients can access resources that support palliative care delivery. To date, little data exist to describe how disparities limit access to palliative care for those patients with HF and their families.

In conclusion, there is clearly an unmet need for palliative care in patients with HF. However, there is a dearth of evidence from which to establish the best symptom management, caregiver support, advance care planning, and palliative care models. The goals of palliative care research should be to design and integrate palliative care with recommended HF treatments to maximize the quality and length of survival in accordance with the patients' goals and preferences.

Funding Sources

Dr. Gelfman has received support from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) (1K23AG049930), the Mount Sinai's Older American Independence Center (1P30AG28741-01). Drs. Gelfman and Bakitas received funding from the John A. Hartford Foundation and the American Federation on Aging Research. Dr. Bakitas has received support from the John A. Hartford Foundation and the American Federation on Aging Research National Palliative Care Research Center and the National Institute for Nursing Research (1 R01 NR013665-01A1). Dr. Goldstein received funding from Mount Sinai's Older American Independence Center (1P30AG28741-01). The symposium was supported by the John A. Hartford/AFAR Center of Excellence Collaborative Pilot Project, National Palliative Care Research Center, UAB Centers for Comprehensive Cardiovascular Care and Palliative and Supportive Care, UAB School of Nursing, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and Mount Sinai's Claude Pepper Older American Independence Center.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: the Improving Palliative Care for Patients with Heart Failure and Their Families (IMPACT-HF2) Working Group

Acknowledgments

This article is submitted on behalf of the members of the IMPACT-HF2 Working Group: Sangeeta Ahluwalia, Larry Allen, Kristen Allen, Bob Arnold, Marie Bakitas, David Bekelman, Harleah Buck, J. Nicholas Dionne-Odom, Cynthia Dougherty, Sandra Dunbar, Lorraine Evangelista, Beth Fahlberg, Timothy Fendler, Laura Gelfman, Nathan Goldstein, Laura Hanson, Paul Hauptman, Mohana Karlekar, Dio Kavalieratos, James Kirkpatrick, Peggy Kirkwood, Alan Kono, Harlan Krumholz, Jean Kutner, Anu Lala, Joanne Lindenfeld, Gisella Mancarella, Daniel Matlock, Marianne Matzo, Matthew Maurer, Sean Morrison, Arden O'Donnell, Salpy Pamboukian, Sean Pinney, Sita Prince, Barbara Reigel, Christine Ritchie, Joseph Rogers, John Spertus, Karen Steinhauser, Lynne Stevenson, Anna Strömberg, Rebecca Sudore, Keith Swetz, Winifred Teuteberg, Jeffrey Teuteberg, Rodney Tucker, James Tulsky, and Debra Wiegand.

The authors express their gratitude to R. Sean Morrison, MD, Susan Zieman, MD-PhD, and Basil Eldadah, MD-PhD, as well as all of the participants of the two-day National Institutes of Health/National Palliative Care Research Center workshop, “Advancing and Extending a Palliative Care Research Agenda in the Specialties” in Bethesda, Maryland, in August 2016.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. : Executive summary: Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013;127:143–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. : ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): Developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2005;112:e154–e235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. : Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011;123:933–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Writing Group Members; Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al.: Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010;121:e46–e215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu L: Changes in cardiovascular hospitalization and comorbidity of heart failure in the United States: Findings from the National Hospital Discharge Surveys 1980–2006. Int J Cardiol 2011;149:39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. : Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA 2004;292:344–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solano JP, Gomes B, Higginson IJ: A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;31:58–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A: Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007–1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krumholz HM, Phillips RS, Hamel MB, et al. : Resuscitation preferences among patients with severe congestive heart failure: Results from the SUPPORT project. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Circulation 1998;98:648–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. : 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:e147–e239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. : Executive summary: Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;133:447–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costanzo MR, Mills RM, Wynne J: Characteristics of “Stage D” heart failure: Insights from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry Longitudinal Module (ADHERE LM). Am Heart J 2008;155:339–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding R, Beynon T, Hodson F, et al. : Provision of palliative care for chronic heart failure inpatients: How much do we need? BMC Palliat Care 2009;8:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Hernandez AF, et al. : Resource use in the last 6 months of life among medicare beneficiaries with heart failure, 2000–2007. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:196–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. : Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:606–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodlin SJ: Palliative care in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:386–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Setoguchi S, Glynn RJ, Stedman M, et al. : Hospice, opiates, and acute care service use among the elderly before death from heart failure or cancer. Am Heart J 2010;160:139–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakas T, Pressler SJ, Johnson EA, et al. : Family caregiving in heart failure. Nurs Res 2006;55:180–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodlin SJ, Hauptman PJ, Arnold R, et al. : Consensus statement: Palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. J Card Fail 2004;10:200–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Wouters EF, Schols JM: Daily symptom burden in end-stage chronic organ failure: A systematic review. Palliat Med 2008;22:938–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodlin SJ: End-of-life care in heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rep 2009;11:184–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Udelson JE, Stevenson LW: The future of heart failure diagnosis, therapy, and management. Circulation 2016;133:2671–2686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support. INTERMACS Quarterly Statistical Summary Report, Implant Dates: 6/23/06–9/30/13. www.uab.edu/medicine/intermacs/images/Federal_Quarterly_Report/Federal_Partners_Report_2013_Q3.pdf 2013. (Last accessed January22, 2014.)

- 24.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Proposed Decision Memo for Ventricular Assist Devices for Bridge-to-Transplant and Destination Therapy (CAG-00432R). www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-proposed-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=268 2013. (Last accessed January22, 2014, 2014)

- 25.Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support. Quarterly Statistical Report—Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services—2013 1st Quarter. www.uab.edu/medicine/intermacs/images/CMS/CMS_Report_2013_Q1.pdf 2013. (Last accessed January22, 2014, 2013)

- 26.Baran DA, Jaiswal A: Management of the ACC/AHA stage D patient: Mechanical circulatory support. Cardiol Clin 2014;32:113–124, viii–ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunlay SM, Foxen JL, Cole T, et al. : A survey of clinician attitudes and self-reported practices regarding end-of-life care in heart failure. Palliat Med 2015;29:260–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cosgriff JA, Pisani M, Bradley EH, et al. : The association between treatment preferences and trajectories of care at the end-of-life. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1566–1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bakitas M, Macmartin M, Trzepkowski K, et al. : Palliative care consultations for heart failure patients: How many, when, and why? J Card Fail 2013;19:193–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dionne-Odom JN, Kono A, Frost J, et al. : Translating and testing the ENABLE: CHF-PC concurrent palliative care model for older adults with heart failure and their family caregivers. J Palliat Med 2014;17:995–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mentz RJ, Tulsky JA, Granger BB, et al. : The palliative care in heart failure trial: Rationale and design. Am Heart J 2014;168:645–651.e641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safford MM, Shewchuk R, Qu H, et al. : Reasons for not intensifying medications: Differentiating “clinical inertia” from appropriate care. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1648–1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, et al. : Decision making in advanced heart failure: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012;125:1928–1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feldman D, Pamboukian SV, Teuteberg JJ, et al. : The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for mechanical circulatory support: Executive summary. J Heart Lung Transplant 2013;32:157–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang JC, Ewald GA, Allen LA, et al. : Advanced (stage D) heart failure: A statement from the Heart Failure Society of America Guidelines Committee. J Card Fail 2015;21:519–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKelvie RS, Moe GW, Cheung A, et al. : The 2011 Canadian Cardiovascular Society heart failure management guidelines update: Focus on sleep apnea, renal dysfunction, mechanical circulatory support, and palliative care. Can J Cardiol 2011;27:319–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Modified: Ventricular assist device destination therapy requirements. Jt Comm Perspect 2014;34:6–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Proposed Decision Memo for Ventricular Assist Devices for Bridge-to-Transplant and Destination Therapy (CAG-00432R). https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-proposed-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=268 2013. (Last accessed May12, 2016)

- 39.Xie K, Gelfman L, Horton JR, Goldstein NE: State of Research on Palliative Care in Heart Failure as Evidenced by Published Literature, Conference Proceedings, and NIH Funding. J Card Fail 2017;23:197–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alpert CM, Smith MA, Hummel SL, Hummel EK: Symptom burden in heart failure: Assessment, impact on outcomes, and management. Heart Fail Rev 2017;22:25–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bekelman DB, Nowels CT, Allen LA, et al. : Outpatient palliative care for chronic heart failure: A case series. J Palliat Med 2011;14:815–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan RF, Feder S, Goldstein NE, Chaudhry SI: Symptom burden among patients who were hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1713–1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirkpatrick JN, Kellom K, Hull SC, et al. : Caregivers and left ventricular assist devices as a destination, not a journey. J Card Fail 2015;21:806–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcuccilli L, Casida JJ, Bakas T, Pagani FD: Family caregivers' inside perspectives: Caring for an adult with a left ventricular assist device as a destination therapy. Prog Transplant 2014;24:332–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McIlvennan CK, Jones J, Allen LA, et al. : Bereaved caregiver perspectives on the end-of-life experience of patients with a left ventricular assist device. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:534–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joo H, Fang J, Losby JL, Wang G: Cost of informal caregiving for patients with heart failure. Am Heart J 2015;169:142–148.e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunlay SM, Swetz KM, Mueller PS, Roger VL: Advance directives in community patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:283–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Butler J, Binney Z, Kalogeropoulos A, et al. : Advance directives among hospitalized patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:112–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stevenson LW, O'Donnell A: Advanced care planning: Care to plan in advance. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:122–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dunlay SM, Swetz KM, Redfield MM, et al. : Resuscitation preferences in community patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014;7:353–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kramer DB, Matlock DD, Buxton AE, et al. : Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator use in older adults: Proceedings of a Hartford Change AGEnts Symposium. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2015;8:437–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dodson JA, Fried TR, Van Ness PH, et al. : Patient preferences for deactivation of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:377–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goldstein NE, Mehta D, Siddiqui S, et al. : “That's like an act of suicide” patients' attitudes toward deactivation of implantable defibrillators. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23 Suppl 1:7–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldstein NE, Mehta D, Teitelbaum E, et al. : “It's like crossing a bridge” complexities preventing physicians from discussing deactivation of implantable defibrillators at the end of life. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23 Suppl 1:2–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boothroyd LJ, Lambert LJ, Ducharme A, et al. : Challenge of informing patient decision making: What can we tell patients considering long-term mechanical circulatory support about outcomes, daily life, and end-of-life issues? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014;7:179–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murray SA, Boyd K, Kendall M, et al. : Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: Prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ 2002;325:929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rogers AE, Addington-Hall JM, Abery AJ, et al. : Knowledge and communication difficulties for patients with chronic heart failure: Qualitative study. BMJ 2000;321:605–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al. : Place of death: Correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers' mental health. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4457–4464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. : Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665–1673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang B, Nilsson ME, Prigerson HG: Factors important to patients' quality of life at the end of life. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1133–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. : Health care costs in the last week of life: Associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:480–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mack JW, Block SD, Nilsson M, et al. : Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer: The Human Connection Scale. Cancer 2009;115:3302–3311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, et al. : In search of a good death: Observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:825–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. : Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 2000;284:2476–2482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quill TE: Perspectives on care at the close of life. Initiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients: Addressing the “elephant in the room”. JAMA 2000;284:2502–2507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wachter RM, Luce JM, Hearst N, Lo B: Decisions about resuscitation: Inequities among patients with different diseases but similar prognoses. Ann Intern Med 1989;111:525–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Remme WJ, McMurray JJ, Rauch B, et al. : Public awareness of heart failure in Europe: First results from SHAPE. Eur Heart J 2005;26:2413–2421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sudore RL, Knight SJ, McMahan RD, et al. : A novel website to prepare diverse older adults for decision making and advance care planning: A pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:674–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Steinhauser KE, Alexander SC, Byock IR, et al. : Do preparation and life completion discussions improve functioning and quality of life in seriously ill patients? Pilot randomized control trial. J Palliat Med 2008;11:1234–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bakitas M, Stevens M, Ahles T, et al. : Project ENABLE: A palliative care demonstration project for advanced cancer patients in three settings. J Palliat Med 2004;7:363–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. : Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. : The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: Baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Support Care 2009;7:75–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen CY, Thorsteinsdottir B, Cha SS, et al. : Health care outcomes and advance care planning in older adults who receive home-based palliative care: A pilot cohort study. J Palliat Med 2015;18:38–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.O'Connor M, Asdornwised U, Dempsey ML, et al. : Using telehealth to reduce all-cause 30-day hospital readmissions among heart failure patients receiving skilled home health services. Appl Clin Inform 2016;7:238–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kao DP, Lindenfeld J, Macaulay D, et al. : Impact of a telehealth and care management program on all-cause mortality and healthcare utilization in patients with heart failure. Telemed J E Health 2016;22:2–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ritchie CS, Houston TK, Richman JS, et al. : The E-Coach technology-assisted care transition system: A pragmatic randomized trial. Transl Behav Med 2016;6:428–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Quill TE, Abernethy AP: Generalist plus specialist palliative care—Creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bain KT, Maxwell TL, Strassels SA, Whellan DJ: Hospice use among patients with heart failure. Am Heart J 2009;158:118–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kheirbek RE, Fletcher RD, Bakitas MA, et al. : Discharge hospice referral and lower 30-day all-cause readmission in medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:733–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheung WY, Schaefer K, May CW, et al. : Enrollment and events of hospice patients with heart failure vs. cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:552–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stevenson LW, Davis RB: Model building as an educational hobby. Circ Heart Fail 2016;9:pii: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.A Call to Action: Policy Initiatives to Support Palliative Care. https://reportcard.capc.org/recommendations (Last accessed May12, 2016)

- 83.Kamal AH, Bull JH, Swetz KM, et al. : Future of the palliative care workforce: Preview to an impending crisis. Am J Med 2017;130:113–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aldridge MD, Canavan M, Cherlin E, Bradley EH: Has hospice use changed? 2000–2010 utilization patterns. Med Care 2015;53:95–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Khand A, Gemmel I, Clark A, Cleland J: Is the prognosis of heart failure improving? J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:2284–2286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Johnson KS: Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1329–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jurgens CY, Goodlin S, Dolansky M, et al. : Heart failure management in skilled nursing facilities: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:655–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]