Abstract

Aberrant wound healing responses to lung injury are believed to contribute to fibrotic lung diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). The lysophospholipids lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P), by virtue of their ability to mediate many basic cellular functions, including survival, proliferation, migration, and contraction, can influence many of the biological processes involved in wound healing. Accordingly, recent investigations indicate that LPA and S1P may play critical roles in regulating the development of lung fibrosis. Here we review the evidence indicating that LPA and S1P regulate pulmonary fibrosis and the potential mechanisms through which these lysophospholipids may influence fibrogenesis induced by lung injury.

Keywords: lysophospholipids, lysophosphatidic acid, sphingosine 1-phosphate, lung fibrosis

The response to lung injury involves a complex series of biological responses which, if appropriate in timing, magnitude, and balance, lead to resolution of injury and restoration of normal lung structure and function. When dysregulated or overexuberant, however, these responses can result in excessive scar formation, or fibrosis, characterized by the pathological accumulation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts and the extracellular matrix that they synthesize. Such dysregulated wound healing responses to injury have been implicated in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and the fibroproliferative phase of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Notably in IPF, the replacement of normal tissue with fibrosis is progressive and eventually leads to end-stage organ dysfunction and death (1). Because lung fibrosis may be difficult to reverse once established, strategies aimed at preventing fibrosis by interrupting the upstream biological processes that contribute to fibrogenesis are likely to have the greatest therapeutic impact.

The biological responses to injury that may contribute to the development of lung fibrosis include: (1) epithelial cell death/apoptosis; (2) increased vascular permeability; (3) inflammatory cell recruitment; (4) extravascular coagulation; (5) activation of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and other profibrotic mediators; (6) fibroblast recruitment, proliferation, persistence, and activation to myofibroblasts; and (7) synthesis of collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins (2–5). In individuals in whom these processes are dysregulated or overexuberant, devastating diseases such as IPF may result from commonly occurring injurious insults to the lung, such as inhaled particulates, viral infections, or aspiration of refluxed gastric acid (6–8). Better understanding of the molecular mediators and pathways that regulate these wound-healing responses should therefore lead to novel therapeutic targets for fibrotic diseases. In support of this approach, multiple investigations in animal models of lung fibrosis have demonstrated that targeting one or more of these wound-healing responses can prevent the development of fibrosis and in some cases reverse established fibrosis (9–15).

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) are bioactive lysophospholipids that signal through distinct G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), LPA1–5 and S1P1–5 (16). Both of these lysophospholipids mediate many basic cellular functions, including cell migration, survival, contraction, proliferation, gene expression, and cell–cell interactions (17, 18). Particularly relevant to wound healing responses to lung injury, LPA and S1P have been shown to regulate epithelial cell and fibroblast apoptosis, fibroblast migration and myofibroblast differentiation, vascular permeability, and TGF-β signaling in vitro (19–26). Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated important roles for LPA and S1P in regulating the development of lung fibrosis in vivo. Targeting the LPA and S1P pathways therefore may represent effective therapeutic strategies for fibrotic diseases such as IPF. Here we review the relevant literature demonstrating important roles for LPA and S1P in lung fibrosis, focusing on animal models of this disease and on the cellular mechanisms through which these two lysophospholipids regulate its development.

LPA and S1P Structure, Metabolism, and Receptors

LPA and S1P Chemical Structure

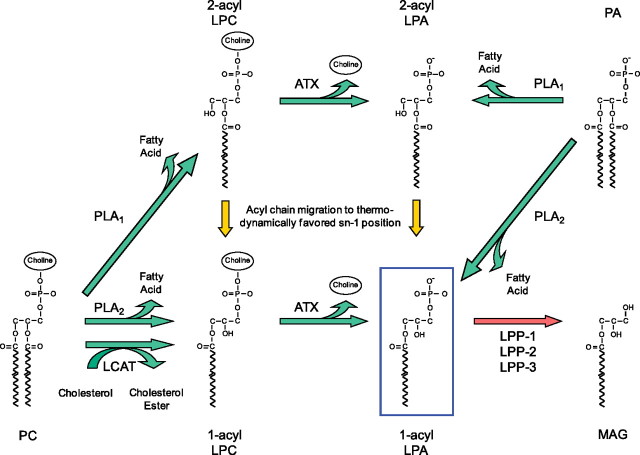

LPA is the common name for 1-acyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphates, which consist of a glycerol phosphate backbone esterified with a single fatty acid (27). Various species of LPA differ only in the identity of the fatty acid moiety. S1P is the phosphorylation product of sphingosine (2-amino-4-octadecene-1,3-diol), a long-chain, unsaturated amino alcohol, which is a backbone component of membrane sphingolipids (28). The chemical structures of LPA species and S1P are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P).

LPA and S1P Metabolism

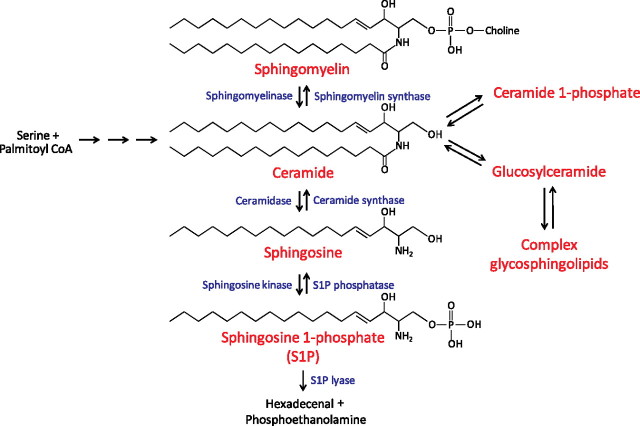

LPA has been demonstrated to be produced in response to injury and to promote wound healing in multiple tissues, including the skin, the gastrointestinal tract, and the cornea (14, 29–34). LPA can be produced from membrane phospholipids of cells or platelets, and from surfactant phospholipids in the lung, by at least three pathways (Figure 2) (35). Of these, conversion of lysophosphatidylcholine to LPA by the enzyme autotaxin appears to account for the majority of extracellular LPA in vivo (36, 37). LPA can also be degraded in several ways (38). Of these, hydrolysis of LPA by the lipid phosphate phosphatases is likely the major pathway for clearance of LPA in vivo (39).

Figure 2.

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) metabolism. LPA can be produced by several different pathways. Phospholipids such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) can be converted to lysophospholipids such as lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) by members of the phospholipase A1 (PLA1) and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) families of enzymes. These lysophospholipids can be converted to LPA by the lysophospholipase D activity of autotaxin (ATX). Alternatively, LPA can be generated from phospholipids by the sequential actions of lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) and ATX. Last, PLA1 and PLA2 enzymes can produce LPA directly by hydrolysis of phosphatidic acid (PA). Several PLA1 and PLA2 enzymes have been implicated in extracellular LPA production, including mPA-PLA1α/Lipase H (LIPH), mPA-PLA1β, PS-PLA1, and sPLA2-IIA. LPA can also be degraded in several ways. Of these, hydrolysis of LPA to monoacylglycerol (MAG) by lipid phosphate phosphatases (LPP-1, LPP-2, and LPP-3) is likely the major pathway for clearance of LPA in vivo.

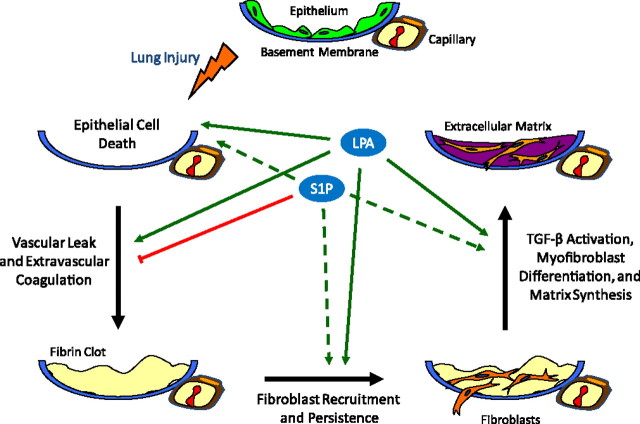

S1P is a bioactive sphingolipid derived from sphingosine. There are hundreds of known sphingolipid species; the metabolism of some of the more commonly studied sphingolipids is depicted in Figure 3. Phosphorylation of sphingosine by sphingosine kinases results in the synthesis of S1P, which can either be converted back to sphingosine by the action of S1P phosphatase or the lipid phosphate phosphatases, or it can be degraded by S1P lyase (40, 41). Given the pleiotropic effects of LPA and S1P, altering their levels by targeting the enzymes involved in their metabolism holds great therapeutic potential for human diseases.

Figure 3.

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) metabolism. Ceramide is considered to be the central molecule in sphingolipid metabolism. It can be generated de novo from serine and palmitoyl-CoA through several intermediate steps, or it can be formed from the catabolism of sphingomyelin and complex glycosphingolipids. Ceramide can be metabolized via several different pathways, one of which is the conversion by ceramidases to sphingosine, which can in turn be phosphorylated by sphingosine kinases (Sphk) to synthesize S1P. S1P can either be converted back to sphingosine by the action of S1P phosphatase or the lipid phosphate phosphatases, or it can be degraded by S1P lyase.

LPA and S1P Receptors

Although LPA and S1P were initially identified as phospholipid precursors and metabolites in cell membrane biosynthesis, their subsequently appreciated ability to regulate diverse biological processes stems from their ability to activate specific GPCRs (42, 43). Currently, five accepted LPA receptors (LPA1-LPA5) and five accepted S1P receptors (S1P1-S1P5) have been identified (16). Eight of these receptors, LPA1–3 and S1P1–5, share substantial sequence homology. Other GPCRs with less homology have also been identified as LPA receptors, including the accepted LPA receptors LPA4 and LPA5, as well as P2Y5, a lower-affinity receptor that is likely to join the LPA receptor family as LPA6 (16), indicating that LPA receptors have evolved through two distinct lineages in the GPCR family (16).

LPA and Lung Fibrosis

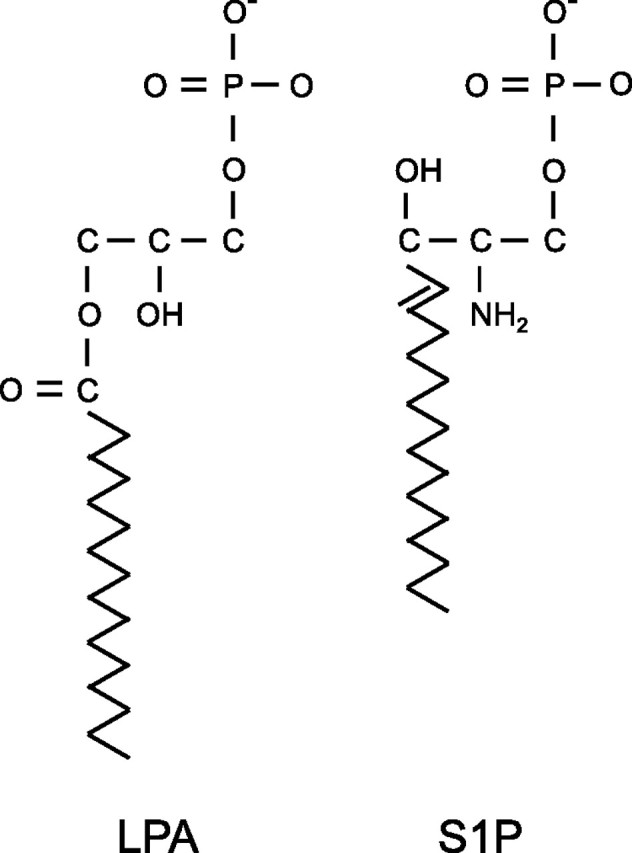

The role of LPA as a potent mediator of lung fibrosis was recently demonstrated. LPA signaling through the LPA1 receptor was found to be critically required for the development of pulmonary fibrosis induced in mice by bleomycin lung injury: LPA levels increased in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid after bleomycin challenge, and mice deficient for LPA1 (LPA1 knockout [KO] mice) were found to be dramatically protected from lung fibrosis and mortality in this model (14). Similarly, treatment with a specific LPA1 antagonist protected mice from the development of fibrosis induced by bleomycin (44). Studies in patients with IPF have implicated LPA-LPA1 signaling in the development of lung fibrosis in humans as well. LPA levels were increased in BAL samples from patients with IPF, LPA1 was highly expressed by fibroblasts recovered from these samples, and inhibition of LPA1 markedly reduced fibroblast responses to the chemotactic activity of those BAL samples (14). These data suggest that LPA signaling through LPA1 contributes to the excessive accumulation of fibroblasts in the lungs of patients with IPF. The LPA-LPA1 pathway appears to mediate numerous wound-healing responses which may contribute to the development of lung fibrosis, including epithelial cell apoptosis, increased vascular permeability, and fibroblast migration and persistence (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) regulation of lung fibrosis. Schematic representation of the biological processes implicated in lung fibrosis that appear to be regulated by LPA and S1P. Evidence reviewed in this article indicates that LPA contributes to the development of fibrosis after lung injury through multiple mechanisms (solid green arrows), including the induction of: (1) epithelial cell apoptosis; (2) increased vascular permeability, resulting in increased intraalveolar coagulation; (3) fibroblast recruitment into the injured airspaces and their resistance to apoptosis; and (4) activation of latent TGF-β. Mechanisms 1 to 3 appear to be mediated by LPA signaling through LPA1, whereas mechanism 4 appears to be mediated by LPA signaling through LPA2. S1P may have both anti- and profibrotic effects in the lung. Evidence reviewed in this article indicates that S1P inhibits the development of pulmonary fibrosis through attenuation of lung vascular leak (red line). This mechanism appears to be mediated by S1P signaling through S1P1 expressed on endothelial cells. Potential profibrotic activities of S1P, which have not yet been investigated in the lung (dashed green arrows), include the induction of: (1) epithelial cell apoptosis, (2) fibroblast recruitment, and (3) myofibroblast differentiation.

LPA-LPA1 Signaling Promotes Epithelial Cell Apoptosis

Increased lung epithelial cell apoptosis in response to injury is now believed to play a central role in pulmonary fibrogenesis, and LPA-LPA1 signaling appears to contribute to this process. Increased numbers of apoptotic cells have been observed in both the alveolar and bronchial epithelia of patients with IPF (45, 46), and induction of pulmonary epithelial cell apoptosis in mice is sufficient to result in the development of fibrosis (47–50). Epithelial cell apoptosis is also prominent in the bleomycin model of pulmonary fibrosis, in which intratracheal bleomycin challenge leads to the rapid appearance of apoptosis in alveolar and bronchial epithelial cells (48, 49, 51). The number of apoptotic cells present in both the alveolar and bronchial epithelia of LPA1 KO mice was significantly reduced compared with wild-type mice early post-bleomycin challenge, suggesting that LPA-LPA1 signaling promotes epithelial apoptosis after lung injury (52). Consistent with these in vivo results, we found that LPA signaling through LPA1 induced apoptosis in culture of both primary human bronchial epithelial cells and a rat alveolar epithelial cell line (52). In these in vitro studies, LPA-LPA1 signaling appeared to specifically mediate anoikis, the apoptosis of anchorage-dependent cells induced by their detachment (53).

LPA-LPA1 Signaling Promotes Increased Vascular Permeability

Vascular leak is another hallmark of tissue injury (54, 55). Increased alveolar-capillary permeability has been demonstrated to be present in the lungs of patients with pulmonary fibrosis and to predict worse outcomes (56, 57). Tissue injury can directly disrupt blood vessels, but beyond the immediate effects of vascular disruption, tissue injury also results in the elaboration of bioactive mediators that cause an increase in vascular permeability that persists throughout the early phases of tissue repair (58). In the lung, LPA appears to be one of these mediators contributing to persistent vascular leak after injury.

Increased transport of fluid and macromolecules across the endothelium under pathologic conditions primarily occurs through paracellular gaps formed by the disruption of endothelial intercellular junctions (59). LPA is known to disrupt endothelial monolayers in vitro through activation of RhoA/Rho kinase within endothelial cells, which results in the formation of intracellular actin stress fibers and the opening up of paracellular gaps (60). This process also appears to be mediated by LPA1, as we have found that LPA-induced endothelial barrier disruption in vitro is inhibited by AM095 (unpublished data), a specific LPA1 receptor antagonist (61). LPA1 KO mice exhibit decreased vascular leak after bleomycin lung injury, indicating that LPA-LPA1 signaling participates in endothelial barrier dysfunction induced by lung injury in vivo (14). The LPA-LPA1 pathway therefore may also contribute to lung fibrosis by increasing vascular permeability in the lung after injury.

Persistent vascular leak appears to contribute to the development of fibrosis after lung injury through the promotion of intraalveolar coagulation (62, 63). Increased vascular permeability results in extravasation of coagulation cascade proteins into the airspaces, where they are activated by tissue procoagulants. Intraalveolar coagulation can, in turn, promote lung fibrosis via at least two potential mechanisms: (1) promotion of fibroblast accumulation in response to the presence of fibrin clot in the airspaces, and (2) direct profibrotic effects of the coagulation proteinases. Fibrin in the airspaces may contribute to fibroblast accumulation by providing a provisional matrix into which fibroblasts migrate during tissue repair and by promoting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (54, 64, 65). Intraalveolar fibrin deposition does not appear to be absolutely required for fibrosis to occur, however, as fibrinogen-null mice are capable of developing lung fibrosis after bleomycin lung injury despite being unable to form fibrin clots (66, 67). Thrombin and other coagulation proteinases have now been shown to have profibrotic effects that are independent of their ability to generate fibrin, through activation of the proteinase-activated receptors on epithelial cells and fibroblasts. Activation of these receptors can promote fibrosis through the induction of mediators such as platelet-derived growth factor and CCL2, and/or through the activation of latent TGF-β (12, 63, 68). LPA–LPA1-mediated endothelial barrier disruption therefore could contribute to the development of fibrosis after lung injury by augmenting activation of the coagulation cascade and its proteases in the airspaces. Consistent with this hypothesis, LPA1 KO mice exhibited decreased intraalveolar coagulation in addition to decreased vascular leak after bleomycin lung injury (14). Based on the data linking intraalveolar coagulation to fibrosis, the decreased intraalveolar coagulation observed in LPA1 KO mice would therefore be predicted to contribute to their protection from pulmonary fibrosis.

LPA-LPA1 Signaling Promotes Fibroblast Migration

The pathologic accumulation of fibroblasts in the lung is another hallmark of pulmonary fibrosis and may result from a combination of increased fibroblast recruitment and proliferation and decreased fibroblast apoptosis. After cutaneous injury, fibroblast migration into the provisional fibrin matrix of the wound clot is a central step in granulation tissue formation (54, 55). Fibroblasts analogously migrate into the fibrin-rich exudates that develop in the airspaces after lung injury in IPF (69). Several lines of evidence suggest that this fibroblast migration is a critical step in the development of lung fibrosis. Fibroblast chemoattractant activity is generated in the airspaces in IPF, and the extent of this activity correlates with disease severity (70). Genes related to cell migration are up-regulated in the lungs of patients with an accelerated variant of IPF, and BAL samples from these “rapid progressors” induce significantly greater fibroblast migration than BAL from “slow progressors” (71). Last, several studies in animal models have found that the inhibition of fibroblast migration can attenuate the development of pulmonary fibrosis, whereas the promotion of fibroblast migration can exaggerate fibrosis (13, 72–75).

LPA is a potent inducer of migration of multiple cell types, including fibroblasts (20). As noted above, LPA levels increased in BAL fluid recovered from mice after bleomycin challenge. LPA1 is highly expressed on mouse lung fibroblasts, and chemotaxis induced by BAL from bleomycin-challenged mice was attenuated by greater than 50% when the responding cells were lung fibroblasts isolated from LPA1 KO mice (14), suggesting that LPA-LPA1 signaling is predominantly responsible for fibroblast recruitment to sites of lung injury in the bleomycin model of lung fibrosis. Consistent with this hypothesis, LPA1 KO mice exhibited diminished fibroblast accumulation in the lungs after bleomycin injury, suggesting that diminished fibroblast migration may contribute to the attenuated lung fibrosis seen in bleomycin-challenged LPA1 KO mice. Furthermore, analysis of the fibroblast chemoattractant activity in BAL fluid obtained from patients with IPF indicated that LPA-LPA1 signaling also directs fibroblast migration into the injured airspaces in IPF, as described above (14).

LPA-LPA1 Signaling Promotes Fibroblast Persistence

The LPA-LPA1 pathway also promotes fibroblast resistance to apoptosis, which has been hypothesized to also contribute to the pathologic accumulation of fibroblasts in lung fibrosis (76). Compared with lung fibroblasts from control subjects, lung fibroblasts isolated from patients with IPF have been demonstrated to be resistant to apoptosis induced ex vivo (77). LPA has been reported to prevent apoptosis in various fibroblast cell lines (78). Our laboratory has found that LPA signaling specifically through LPA1 can completely suppress the apoptosis of primary mouse lung fibroblasts induced by serum deprivation (52), suggesting that suppression of fibroblast apoptosis is another mechanism through which LPA-LPA1 signaling may promote pulmonary fibrosis.

LPA-LPA1 signaling therefore appears have divergent effects on the apoptotic behaviors of epithelial cells and fibroblasts, promoting apoptosis in the former but suppressing apoptosis in the latter. Consistent with these findings, LPA’s effects on apoptosis have previously been demonstrated to be cell-specific, promoting apoptosis of certain cell types but inhibiting apoptosis of others (19). Increased epithelial cell apoptosis coupled with fibroblast resistance to apoptosis has been referred to as an “apoptosis paradox” in IPF (76). The molecular pathways responsible for the divergent susceptibilities of epithelial cells and fibroblasts to apoptosis in IPF have yet to be fully identified, but our data suggest that LPA signaling through LPA1 may contribute (52). There is precedent for both epithelial cell apoptosis and fibroblast resistance to apoptosis being induced by the same mediator. As we found with LPA, TGF-β induces apoptosis of lung epithelial cells (79, 80) but induces resistance to apoptosis in lung fibroblasts (81, 82). Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) has also been shown to mediate divergent effects on cell survival, although its effects appear to oppose those of LPA and TGF-β: PGE2 was found to protect lung epithelial cells against apoptosis while promoting the apoptosis of lung fibroblasts (83). Therefore, increased LPA levels, increased TGF-β activity, and decreased PGE2 levels in the lung may each contribute to the increased epithelial cell but reduced fibroblast apoptosis observed in IPF.

LPA-LPA2 Signaling Promotes TGF-β Activation

In addition to the mechanisms described above by which LPA-LPA1 signaling may contribute to lung fibrosis, LPA signaling though another one of its receptors, LPA2, may contribute to fibrosis by activating the central profibrotic cytokine TGF-β. Through interaction with its cell-surface receptors, TGF-β influences a wide variety of cellular behaviors, many of which are directly involved in tissue remodeling and repair (84). TGF-β overexpression in mice has been shown to be sufficient to cause pulmonary fibrosis, and numerous studies have shown that inhibition of TGF-β activation and/or signaling is protective in mouse models of pulmonary fibrosis (10, 85–87).

TGF-β activity is primarily regulated by the post-translational conversion of latent TGF-β complexes to active TGF-β (88), and LPA-LPA2 signaling may contribute to this conversion. TGF-β is synthesized as part of a larger precursor molecule, which is cleaved post-translationally into mature TGF-β and a latency-associated peptide (LAP). LAP remains noncovalently bound to TGF-β on secretion and prevents TGF-β from binding to its receptors (89). TGF-β must therefore dissociate from, or alter its interactions with, LAP to exert its biological effects. Several processes can mediate this required activation of TGF-β, including conformational changes in LAP induced by interaction with one of four αv-containing integrins, αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, or αvβ8 (90). Activation of TGF-β specifically by the αvβ6 integrin has been shown to be crucial for the development of lung fibrosis in several animal models, including the bleomycin model of pulmonary fibrosis (10). Activation of TGF-β by αv-containing integrins requires that these integrins themselves become activated (91), and thrombin signaling through proteinase-activated receptor-1 has been demonstrated to produce active TGF-β by activating αvβ6 (68). More recently, LPA signaling through LPA2 has similarly been demonstrated to induce αvβ6-dependent activation of latent TGF-β by normal human bronchial epithelial cells (21), indicating that TGF-β activation may be another important mechanism through which LPA promotes pulmonary fibrosis. Activation of TGF-β by LPA may be a conserved profibrotic pathway in the lung: LPA has recently been demonstrated to also induce αvβ5-dependent activation of latent TGF-β by human airway smooth muscle cells, which may contribute to the peribronchial fibrosis of asthmatic airway remodeling (92).

S1P and Lung Fibrosis

Like LPA, S1P has been shown to play important roles in many basic cellular functions, including processes implicated in the development of lung fibrosis, such as cellular apoptosis, fibroblast migration and myofibroblast differentiation, vascular permeability, and TGF-β signaling (Figure 4). Furthermore, it has recently been shown that S1P signaling through the S1P1 receptor limits development of pulmonary fibrosis in the bleomycin mouse model. This protective effect of S1P is likely mediated by its ability to limit vascular leak during the early, exudative response to lung injury.

S1P Signaling Limits Increased Vascular Permeability

S1P has been established as a key regulator of the increased vascular permeability characteristic of the early, exudative response to lung injury. S1P’s ability to regulate vascular permeability in the lung appears to be attributable to signaling through S1P1. Activation of S1P1 on endothelial cells by S1P or S1P1 agonists induces cytoskeletal rearrangements that promote formation of intercellular adherens and tight junctions, resulting in enhancement of endothelial monolayer barrier function (23, 93–97). Mice that are genetically deficient for the S1P-producing enzyme sphingosine kinase 1 (Sphk1) develop exaggerated vascular leak after lung injury (98, 99). Genetic deletion of both sphingosine kinases (Sphk1 and Sphk2) results in a complete lack of circulating S1P and increased vascular permeability in multiple organ systems, even in the absence of tissue injury (100). Interrupting S1P-S1P1 signaling with S1P1 receptor antagonists similarly increases vascular leak (101). Conversely, short-term treatment with S1P or S1P1 receptor agonists has been shown to prevent vascular leak in numerous animal models of acute lung injury as well as models of renal and cutaneous injury (95, 97, 101–107).

As described above, excessive or excessively persistent vascular leak is one of the aberrant wound-healing responses to lung injury believed to contribute to the development of pulmonary fibrosis. Attenuation of the early, exudative responses to lung injury by S1P-S1P1 signaling may therefore also limit the subsequent development of fibrosis. In support of the ability of S1P-S1P1 signaling to limit injury-induced lung fibrosis, S1P1 inhibition has recently been shown to increase both pulmonary vascular leak and fibrosis after bleomycin-induced lung injury in mice (108). Given the evidence implicating extravascular coagulation in the development of lung fibrosis discussed above, the increase in lung fibrosis caused by S1P1 inhibition was likely attributable to the increases in pulmonary vascular leak and intraalveolar coagulation observed in these mice (108). S1P1 inhibition also altered leukocyte accumulation in the airspaces after bleomycin challenge, reducing T-cell but increasing neutrophil accumulation (108), which may have contributed to the exaggerated fibrotic response. Whether or not inflammatory leukocytes play a central role in the development of lung fibrosis after injury is unclear, however, as the fibrotic and inflammatory responses to bleomycin have been dissociated from each other in multiple studies (10, 14, 109–114).

S1P Signaling and Other Profibrotic Processes

In vitro studies have shown that S1P is capable of mediating other processes that may contribute to the development of lung fibrosis, although some of these studies have produced conflicting data. For example, S1P has been shown to potentiate fibroblast chemotaxis in some investigations but inhibit fibroblast chemotaxis in others (24, 115–117). S1P has also been shown to have cell-specific effects on apoptosis, either inducing apoptosis or promoting survival in different cell types (26, 118, 119). Similar to LPA, S1P could therefore potentially contribute to the divergent apoptotic behaviors of lung epithelial cells and fibroblasts observed in lung fibrosis. Last, also like LPA, S1P has been shown to play a role in TGF-β–induced differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts in vitro, another critical process in fibrogenesis (25, 120, 121).

Conclusions

LPA and S1P influence a wide array of basic cellular functions, including survival, proliferation, migration, and contraction. Many of the cellular processes regulated by LPA and S1P are fundamentally involved in wound-healing responses to lung injury. Recent studies indicate that LPA and S1P may be centrally involved when these wound-healing responses become aberrant and result in the development of lung fibrosis. LPA has been shown to have mostly profibrotic effects in the lung, by promoting such processes as epithelial cell apoptosis, increased vascular permeability, fibroblast migration and resistance to apoptosis, and activation of latent TGF-β. S1P-S1P1 signaling appears to protect against the development of lung fibrosis, likely through its ability to limit vascular leak during the early, exudative response to lung injury. Conversely, S1P acting on cells in vitro has also been shown to mediate processes that could promote lung fibrosis, but the contribution of S1P signaling to these processes in the lung in vivo has not yet been fully investigated.

Given the similarities between these two lipid mediators in terms of their chemical structures and metabolism, receptors and signaling pathways, and effects on cellular behavior, LPA and S1P likely exert overlapping effects on the myriad biological processes involved in fibrogenesis in vivo. In the case of vascular leak, they oppose each other, with LPA-LPA1 signaling disrupting endothelial barrier function and S1P-S1P1 signaling restoring barrier function. For processes such as vascular leak, it may be the balance of LPA-LPA1 and S1P-S1P1 signaling that is critical for regulating fibrotic responses to lung injury. Conversely, because both LPA and S1P have been shown to mediate cellular apoptosis and fibroblast migration, they may exert additive or even synergistic effects on these or other fibrosis-modulating pathways. Further study is needed to clarify the mechanisms and specific receptors involved in the pro- and antifibrotic effects of LPA and S1P and the potential interactions between these two lipids and their respective signaling pathways. What we believe has already become clear, however, is that targeting these lysophospholipids and their receptors, either to inhibit or enhance their signaling, holds great promise for the development of novel therapies for fibrotic lung diseases.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01HL095732 and R01HL108975 (A.M.T.) and K08HL105656 (B.S.S.) and grants from the American Thoracic Society (A.M.T. and B.S.S.) and the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation, the Coalition for Pulmonary Fibrosis, the Scleroderma Research Foundation, the Nirenberg Center for Advanced Lung Disease and Amira Pharmaceuticals (A.M.T.).

References

- 1.Ley B, Collard HR, King TE. Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;183:431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selman M, Pardo A. Role of epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: from innocent targets to serial killers. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:364–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gharaee-Kermani M, Hu B, Phan SH, Gyetko MR. Recent advances in molecular targets and treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: focus on TGFbeta signaling and the myofibroblast. Curr Med Chem 2009;16:1400–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antoniou KM, Pataka A, Bouros D, Siafakas NM. Pathogenetic pathways and novel pharmacotherapeutic targets in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2007;20:453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coward WR, Saini G, Jenkins G. The pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2010;4:367–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selman M, King TE, Pardo A. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:136–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross TJ, Hunninghake GW. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2001;345:517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunninghake GW, Schwarz MI. Does current knowledge explain the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? A perspective. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2007;4:449–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eitzman DT, McCoy RD, Zheng X, Fay WP, Shen T, Ginsburg D, Simon RH. Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in transgenic mice that either lack or overexpress the murine plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene. J Clin Invest 1996;97:232–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munger JS, Huang X, Kawakatsu H, Griffiths MJ, Dalton SL, Wu J, Pittet JF, Kaminski N, Garat C, Matthay MA, et al. The integrin alpha v beta 6 binds and activates latent TGF beta 1: a mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell 1999;96:319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunther A, Lubke N, Ermert M, Schermuly RT, Weissmann N, Breithecker A, Markart P, Ruppert C, Quanz K, Ermert L, et al. Prevention of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis by aerosolization of heparin or urokinase in rabbits. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:1358–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howell DC, Johns RH, Lasky JA, Shan B, Scotton CJ, Laurent GJ, Chambers RC. Absence of proteinase-activated receptor-1 signaling affords protection from bleomycin-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2005;166:1353–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tager AM, Kradin RL, LaCamera P, Bercury SD, Campanella GS, Leary CP, Polosukhin V, Zhao LH, Sakamoto H, Blackwell TS, et al. Inhibition of pulmonary fibrosis by the chemokine IP-10/CXCL10. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;31:395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tager AM, Lacamera P, Shea BS, Campanella GS, Selman M, Zhao Z, Polosukhin V, Wain J, Karimi-Shah BA, Kim ND, et al. The lysophosphatidic acid receptor LPA(1) links pulmonary fibrosis to lung injury by mediating fibroblast recruitment and vascular leak. Nat Med 2008;14:45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oga T, Matsuoka T, Yao C, Nonomura K, Kitaoka S, Sakata D, Kita Y, Tanizawa K, Taguchi Y, Chin K, et al. Prostaglandin F(2alpha) receptor signaling facilitates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis independently of transforming growth factor-beta. Nat Med 2009;15:1426–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chun J, Hla T, Lynch KR, Spiegel S, Moolenaar WH. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXVIII. Lysophospholipid receptor nomenclature. Pharmacol Rev 2010;62:579–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishii I, Fukushima N, Ye X, Chun J. Lysophospholipid receptors: signaling and biology. Annu Rev Biochem 2004;73:321–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivera R, Chun J. Biological effects of lysophospholipids. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 2008;160:25–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye X, Ishii I, Kingsbury MA, Chun J. Lysophosphatidic acid as a novel cell survival/apoptotic factor. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002;1585:108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakai T, Peyruchaud O, Fassler R, Mosher DF. Restoration of beta1a integrins is required for lysophosphatidic acid-induced migration of beta1-null mouse fibroblastic cells. J Biol Chem 1998;273:19378–19382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu MY, Porte J, Knox AJ, Weinreb PH, Maher TM, Violette SM, McAnulty RJ, Sheppard D, Jenkins G. Lysophosphatidic acid induces alphavbeta6 integrin-mediated TGF-beta activation via the LPA2 receptor and the small G protein G alpha(q). Am J Pathol 2009;174:1264–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi JW, Herr DR, Noguchi K, Yung YC, Lee CW, Mutoh T, Lin ME, Teo ST, Park KE, Mosley AN, et al. LPA receptors: subtypes and biological actions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2010;50:157–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia JG, Liu F, Verin AD, Birukova A, Dechert MA, Gerthoffer WT, Bamberg JR, English D. Sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes endothelial cell barrier integrity by EDG-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangement. J Clin Invest 2001;108:689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goparaju SK, Jolly PS, Watterson KR, Bektas M, Alvarez S, Sarkar S, Mel L, Ishii I, Chun J, Milstien S, et al. The S1P2 receptor negatively regulates platelet-derived growth factor-induced motility and proliferation. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25:4237–4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keller CD, Rivera Gil P, Tolle M, van der Giet M, Chun J, Radeke HH, Schafer-Korting M, Kleuser B. Immunomodulator FTY720 induces myofibroblast differentiation via the lysophospholipid receptor S1P3 and Smad3 signaling. Am J Pathol 2007;170:281–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagen N, Van Veldhoven PP, Proia RL, Park H, Merrill AH, van Echten-Deckert G. Subcellular origin of sphingosine 1-phosphate is essential for its toxic effect in lyase-deficient neurons. J Biol Chem 2009;284:11346–11353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry and International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature and Nomenclature Commission of IUBMB. Biochemical nomenclature and related documents. London: Portland Press; 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pruett ST, Bushnev A, Hagedorn K, Adiga M, Haynes CA, Sullards MC, Liotta DC, Merrill AH. Biodiversity of sphingoid bases (“Sphingosines”) and related amino alcohols. J Lipid Res 2008;49:1621–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazereeuw-Hautier J, Gres S, Fanguin M, Cariven C, Fauvel J, Perret B, Chap H, Salles JP, Saulnier-Blache JS. Production of lysophosphatidic acid in blister fluid: involvement of a lysophospholipase D activity. J Invest Dermatol 2005;125:421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liliom K, Guan Z, Tseng JL, Desiderio DM, Tigyi G, Watsky MA. Growth factor-like phospholipids generated after corneal injury. Am J Physiol 1998;274:C1065–C1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demoyer JS, Skalak TC, Durieux ME. Lysophosphatidic acid enhances healing of acute cutaneous wounds in the mouse. Wound Repair Regen 2000;8:530–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balazs L, Okolicany J, Ferrebee M, Tolley B, Tigyi G. Topical application of the phospholipid growth factor lysophosphatidic acid promotes wound healing in vivo. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2001;280:R466–R472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu KP, Yin J, Yu FS. Lysophosphatidic acid promoting corneal epithelial wound healing by transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007;48:636–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sturm A, Sudermann T, Schulte KM, Goebell H, Dignass AU. Modulation of intestinal epithelial wound healing in vitro and in vivo by lysophosphatidic acid. Gastroenterology 1999;117:368–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aoki J. Mechanisms of lysophosphatidic acid production. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2004;15:477–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Meeteren LA, Ruurs P, Stortelers C, Bouwman P, van Rooijen MA, Pradere JP, Pettit TR, Wakelam MJO, Saulnier-Blache JS, Mummery CL, et al. Autotaxin, a secreted lysophospholipase D, is essential for blood vessel formation during development. Mol Cell Biol 2006;26:5015–5022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albers HM, Dong A, van Meeteren LA, Egan DA, Sunkara M, van Tilburg EW, Schuurman K, van Tellingen O, Morris AJ, Smyth SS, et al. Boronic acid-based inhibitor of autotaxin reveals rapid turnover of LPA in the circulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:7257–7262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Umezu-Goto M, Tanyi J, Lahad J, Liu S, Yu S, Lapushin R, Hasegawa Y, Lu Y, Trost R, Bevers T, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid production and action: validated targets in cancer? J Cell Biochem 2004;92:1115–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imai A, Furui T, Tamaya T, Mills GB. A gonadotropin-releasing hormone-responsive phosphatase hydrolyses lysophosphatidic acid within the plasma membrane of ovarian cancer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:3370–3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brindley DN. Lipid phosphate phosphatases and related proteins: signaling functions in development, cell division, and cancer. J Cell Biochem 2004;92:900–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Natl Rev 2008;9:139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moolenaar WH, van Meeteren LA, Giepmans BN. The ins and outs of lysophosphatidic acid signaling. Bioessays 2004;26:870–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gardell SE, Dubin AE, Chun J. Emerging medicinal roles for lysophospholipid signaling. Trends Mol Med 2006;12:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swaney JS, Chapman C, Correa LD, Stebbins KJ, Bundey RA, Prodanovich PC, Fagan P, Baccei CS, Santini AM, Hutchinson JH, et al. A novel, orally active LPA(1) receptor antagonist inhibits lung fibrosis in the mouse bleomycin model. Br J Pharmacol 2010;160:1699–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuwano K, Kunitake R, Kawasaki M, Nomoto Y, Hagimoto N, Nakanishi Y, Hara N. P21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 and p53 expression in association with DNA strand breaks in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plataki M, Koutsopoulos AV, Darivianaki K, Delides G, Siafakas NM, Bouros D. Expression of apoptotic and antiapoptotic markers in epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2005;127:266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hagimoto N, Kuwano K, Miyazaki H, Kunitake R, Fujita M, Kawasaki M, Kaneko Y, Hara N. Induction of apoptosis and pulmonary fibrosis in mice in response to ligation of Fas antigen. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1997;17:272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matute-Bello G, Wurfel MM, Lee JS, Park DR, Frevert CW, Madtes DK, Shapiro SD, Martin TR. Essential role of MMP-12 in Fas-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2007;37:210–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee CG, Cho SJ, Kang MJ, Chapoval SP, Lee PJ, Noble PW, Yehualaeshet T, Lu B, Flavell RA, Milbrandt J, et al. Early growth response gene 1-mediated apoptosis is essential for transforming growth factor beta1-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med 2004;200:377–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sisson TH, Mendez M, Choi K, Subbotina N, Courey A, Cunningham A, Dave A, Engelhardt JF, Liu X, White ES, et al. Targeted injury of type II alveolar epithelial cells induces pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;181:254–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hagimoto N, Kuwano K, Nomoto Y, Kunitake R, Hara N. Apoptosis and expression of Fas/Fas ligand mRNA in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1997;16:91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Funke M, Xhao Z, Xu Y, Chun J, Tager AM. The lysophosphatidic acid receptor LPA1 promotes epithelial cell apoptosis following lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2012;46:355–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frisch SM, Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. J Cell Biol 1994;124:619–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin P. Wound healing–aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science 1997;276:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med 1999;341:738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mogulkoc N, Brutsche MH, Bishop PW, Murby B, Greaves MS, Horrocks AW, Wilson M, McCullough C, Prescott M, Egan JJ. Pulmonary (99m)Tc-DTPA aerosol clearance and survival in usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). Thorax 2001;56:916–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McKeown S, Richter AG, O’Kane C, McAuley DF, Thickett DR. MMP expression and abnormal lung permeability are important determinants of outcome in IPF. Eur Respir J 2009;33:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N Engl J Med 1986;315:1650–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dudek SM, Garcia JG. Cytoskeletal regulation of pulmonary vascular permeability. J Appl Physiol 2001;91:1487–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Vermeer MA, van Hinsbergh VW. Role of RhoA and Rho kinase in lysophosphatidic acid-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000;20:E127–E133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Swaney JS, Chapman C, Correa LD, Stebbins KJ, Broadhead AR, Bain G, Santini AM, Darlington J, King CD, Baccei CS, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characterization of an oral lysophosphatidic acid type 1 receptor-selective antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2010;336:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Idell S. Coagulation, fibrinolysis, and fibrin deposition in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2003; 31(4, Suppl)S213–S220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chambers RC, Laurent GJ. Coagulation cascade proteases and tissue fibrosis. Biochem Soc Trans 2002;30:194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim KK, Kugler MC, Wolters PJ, Robillard L, Galvez MG, Brumwell AN, Sheppard D, Chapman HA. Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:13180–13185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Loskutoff DJ, Quigley JP. PAI-1, fibrosis, and the elusive provisional fibrin matrix. J Clin Invest 2000;106:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hattori N, Degen JL, Sisson TH, Liu H, Moore BB, Pandrangi RG, Simon RH, Drew AF. Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in fibrinogen-null mice. J Clin Invest 2000;106:1341–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ploplis VA, Wilberding J, McLennan L, Liang Z, Cornelissen I, DeFord ME, Rosen ED, Castellino FJ. A total fibrinogen deficiency is compatible with the development of pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Pathol 2000;157:703–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jenkins RG, Su X, Su G, Scotton CJ, Camerer E, Laurent GJ, Davis GE, Chambers RC, Matthay MA, Sheppard D. Ligation of protease-activated receptor 1 enhances alpha(v)beta6 integrin-dependent TGF-beta activation and promotes acute lung injury. J Clin Invest 2006;116:1606–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kuhn C, Boldt J, King TE, Crouch E, Vartio T, McDonald JA. An immunohistochemical study of architectural remodeling and connective tissue synthesis in pulmonary fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;140:1693–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Behr J, Adelmann-Grill BC, Krombach F, Beinert T, Schwaiblmair M, Fruhmann G. Fibroblast chemotactic response elicited by native bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with fibrosing alveolitis. Thorax 1993;48:736–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Selman M, Carrillo G, Estrada A, Mejia M, Becerril C, Cisneros J, Gaxiola M, Perez-Padilla R, Navarro C, Richards T, et al. Accelerated variant of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: clinical behavior and gene expression pattern. PLoS ONE 2007;2:e482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Hong K, Lutz MA, Murray LA, Xue YY, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Strieter RM. Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to CXCL12 and mediate fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2004;114:438–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moore BB, Murray L, Das A, Wilke CA, Herrygers AB, Toews GB. The role of CCL12 in the recruitment of fibrocytes and lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;35:175–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jiang D, Liang J, Campanella GS, Guo R, Yu S, Xie T, Liu N, Jung Y, Homer R, Meltzer EB, et al. Inhibition of pulmonary fibrosis in mice by CXCL10 requires glycosaminoglycan binding and syndecan-4. J Clin Invest 2010;120:2049–2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lovgren AK, Kovacs JJ, Xie T, Potts EN, Li Y, Foster WM, Liang J, Meltzer EB, Jiang D, Lefkowitz RJ, et al. β-arrestin deficiency protects against pulmonary fibrosis in mice and prevents fibroblast invasion of extracellular matrix. Sci Transl Med 2011;3:74ra23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thannickal VJ, Horowitz JC. Evolving concepts of apoptosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:350–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang W, Wei K, Jacobs SS, Upadhyay D, Weill D, Rosen GD. SPARC suppresses apoptosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis fibroblasts through constitutive activation of beta-catenin. J Biol Chem 2010;285:8196–8206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fang X, Yu S, LaPushin R, Lu Y, Furui T, Penn LZ, Stokoe D, Erickson JR, Bast RC, Mills GB. Lysophosphatidic acid prevents apoptosis in fibroblasts via G(i)-protein-mediated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. Biochem J 2000;352:43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hagimoto N, Kuwano K, Inoshima I, Yoshimi M, Nakamura N, Fujita M, Maeyama T, Hara N. TGF-beta 1 as an enhancer of Fas-mediated apoptosis of lung epithelial cells. J Immunol 2002;168:6470–6478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Solovyan VT, Keski-Oja J. Proteolytic activation of latent TGF-beta precedes caspase-3 activation and enhances apoptotic death of lung epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol 2006;207:445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang HY, Phan SH. Inhibition of myofibroblast apoptosis by transforming growth factor beta(1). Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1999;21:658–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Horowitz JC, Rogers DS, Sharma V, Vittal R, White ES, Cui Z, Thannickal VJ. Combinatorial activation of FAK and AKT by transforming growth factor-beta1 confers an anoikis-resistant phenotype to myofibroblasts. Cell Signal 2007;19:761–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maher TM, Evans IC, Bottoms SE, Mercer PF, Thorley AJ, Nicholson AG, Laurent GJ, Tetley TD, Chambers RC, McAnulty RJ. Diminished prostaglandin E2 contributes to the apoptosis paradox in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB J 2004;18:816–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sime PJ, Xing Z, Graham FL, Csaky KG, Gauldie J. Adenovector-mediated gene transfer of active transforming growth factor-beta1 induces prolonged severe fibrosis in rat lung. J Clin Invest 1997;100:768–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Giri SN, Hyde DM, Hollinger MA. Effect of antibody to transforming growth factor beta on bleomycin induced accumulation of lung collagen in mice. Thorax 1993;48:959–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li M, Krishnaveni MS, Li C, Zhou B, Xing Y, Banfalvi A, Li A, Lombardi V, Akbari O, Borok Z, et al. Epithelium-specific deletion of TGF-beta receptor type II protects mice from bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2010;121:277–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Munger JS, Harpel JG, Gleizes PE, Mazzieri R, Nunes I, Rifkin DB. Latent transforming growth factor-beta: structural features and mechanisms of activation. Kidney Int 1997;51:1376–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sheppard D. Transforming growth factor beta: a central modulator of pulmonary and airway inflammation and fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:413–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goodwin A, Jenkins G. Role of integrin-mediated TGFbeta activation in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Biochem Soc Trans 2009;37:849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huang X, Wu J, Zhu W, Pytela R, Sheppard D. Expression of the human integrin beta6 subunit in alveolar type II cells and bronchiolar epithelial cells reverses lung inflammation in beta6 knockout mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1998;19:636–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tatler AL, John AE, Jolly L, Habgood A, Porte J, Brightling C, Knox AJ, Pang L, Sheppard D, Huang X, et al. Integrin alphavbeta5-mediated TGF-beta activation by airway smooth muscle cells in asthma. J Immunol 2011;187:6094–6107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee MJ, Thangada S, Claffey KP, Ancellin N, Liu CH, Kluk M, Volpi M, Sha'afi RI, Hla T. Vascular endothelial cell adherens junction assembly and morphogenesis induced by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Cell 1999;99:301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Argraves KM, Gazzolo PJ, Groh EM, Wilkerson BA, Matsuura BS, Twal WO, Hammad SM, Argraves WS. High density lipoprotein-associated sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes endothelial barrier function. J Biol Chem 2008;283:25074–25081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sanchez T, Estrada-Hernandez T, Paik JH, Wu MT, Venkataraman K, Brinkmann V, Claffey K, Hla T. Phosphorylation and action of the immunomodulator FTY720 inhibits vascular endothelial cell growth factor-induced vascular permeability. J Biol Chem 2003;278:47281–47290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dudek SM, Camp SM, Chiang ET, Singleton PA, Usatyuk PV, Zhao Y, Natarajan V, Garcia JG. Pulmonary endothelial cell barrier enhancement by FTY720 does not require the S1P1 receptor. Cell Signal 2007;19:1754–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Camp SM, Bittman R, Chiang ET, Moreno-Vinasco L, Mirzapoiazova T, Sammani S, Lu X, Sun C, Harbeck M, Roe M, et al. Synthetic analogues of FTY720 differentially regulate pulmonary vascular permeability in vivo and in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2009;331:54–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tauseef M, Kini V, Knezevic N, Brannan M, Ramchandaran R, Fyrst H, Saba J, Vogel SM, Malik AB, Mehta D. Activation of sphingosine kinase-1 reverses the increase in lung vascular permeability through sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor signaling in endothelial cells. Circ Res 2008;103:1164–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wadgaonkar R, Patel V, Grinkina N, Romano C, Liu J, Zhao Y, Sammani S, Garcia JG, Natarajan V. Differential regulation of sphingosine kinases 1 and 2 in lung injury. Am J Physiol 2009;296:L603–L613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Camerer E, Regard JB, Cornelissen I, Srinivasan Y, Duong DN, Palmer D, Pham TH, Wong JS, Pappu R, Coughlin SR. Sphingosine-1-phosphate in the plasma compartment regulates basal and inflammation-induced vascular leak in mice. J Clin Invest 2009;119:1871–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sanna MG, Wang SK, Gonzalez-Cabrera PJ, Don A, Marsolais D, Matheu MP, Wei SH, Parker I, Jo E, Cheng WC, et al. Enhancement of capillary leakage and restoration of lymphocyte egress by a chiral S1P1 antagonist in vivo. Nat Chem Biol 2006;2:434–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peng X, Hassoun PM, Sammani S, McVerry BJ, Burne MJ, Rabb H, Pearse D, Tuder RM, Garcia JG. Protective effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate in murine endotoxin-induced inflammatory lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;169:1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.McVerry BJ, Peng X, Hassoun PM, Sammani S, Simon BA, Garcia JG. Sphingosine 1-phosphate reduces vascular leak in murine and canine models of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:987–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Awad AS, Ye H, Huang L, Li L, Foss FW, Macdonald TL, Lynch KR, Okusa MD. Selective sphingosine 1-phosphate 1 receptor activation reduces ischemia-reperfusion injury in mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2006;290:F1516–F1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Okazaki M, Kreisel F, Richardson SB, Kreisel D, Krupnick AS, Patterson GA, Gelman AE. Sphingosine 1-phosphate inhibits ischemia reperfusion injury following experimental lung transplantation. Am J Transplant 2007;7:751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Szczepaniak WS, Zhang Y, Hagerty S, Crow MT, Kesari P, Garcia JG, Choi AM, Simon BA, McVerry BJ. Sphingosine 1-phosphate rescues canine lps-induced acute lung injury and alters systemic inflammatory cytokine production in vivo. Transl Res 2008;152:213–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu HB, Cui NQ, Wang Q, Li DH, Xue XP. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and its analogue FTY720 diminish acute pulmonary injury in rats with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreas 2008;36:e10–e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shea BS, Brooks SF, Fontaine BA, Chun J, Luster AD, Tager AM. Prolonged exposure to sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 agonists exacerbates vascular leak, fibrosis, and mortality after lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2010;43:662–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Keane MP, Belperio JA, Moore TA, Moore BB, Arenberg DA, Smith RE, Burdick MD, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM. Neutralization of the CXC chemokine, macrophage inflammatory protein-2, attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol 1999;162:5511–5518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li Q, Park PW, Wilson CL, Parks WC. Matrilysin shedding of syndecan-1 regulates chemokine mobilization and transepithelial efflux of neutrophils in acute lung injury. Cell 2002;111:635–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Manoury B, Nenan S, Guenon I, Lagente V, Boichot E. Influence of early neutrophil depletion on MMPs/TIMP-1 balance in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Int Immunopharmacol 2007;7:900–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Russo RC, Guabiraba R, Garcia CC, Barcelos LS, Roffe E, Souza AL, Amaral FA, Cisalpino D, Cassali GD, Doni A, et al. Role of the chemokine receptor CXCR2 in bleomycin-induced pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;40:410–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Szapiel SV, Elson NA, Fulmer JD, Hunninghake GW, Crystal RG. Bleomycin-induced interstitial pulmonary disease in the nude, athymic mouse. Am Rev Respir Dis 1979;120:893–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Helene M, Lake-Bullock V, Zhu J, Hao H, Cohen DA, Kaplan AM. T cell independence of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Leukoc Biol 1999;65:187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sanchez T, Thangada S, Wu MT, Kontos CD, Wu D, Wu H, Hla T. PTEN as an effector in the signaling of antimigratory G protein-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:4312–4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Long JS, Natarajan V, Tigyi G, Pyne S, Pyne NJ. The functional PDGFbeta receptor-S1P1 receptor signaling complex is involved in regulating migration of mouse embryonic fibroblasts in response to platelet derived growth factor. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 2006;80:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hashimoto M, Wang X, Mao L, Kobayashi T, Kawasaki S, Mori N, Toews ML, Kim HJ, Cerutis DR, Liu X, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate potentiates human lung fibroblast chemotaxis through the S1P2 receptor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;39:356–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Donati C, Cencetti F, Nincheri P, Bernacchioni C, Brunelli S, Clementi E, Cossu G, Bruni P. Sphingosine 1-phosphate mediates proliferation and survival of mesoangioblasts. Stem Cells 2007;25:1713–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schnitzer SE, Weigert A, Zhou J, Brune B. Hypoxia enhances sphingosine kinase 2 activity and provokes sphingosine-1-phosphate-mediated chemoresistance in a549 lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res 2009;7:393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kono Y, Nishiuma T, Nishimura Y, Kotani Y, Okada T, Nakamura S, Yokoyama M. Sphingosine kinase 1 regulates differentiation of human and mouse lung fibroblasts mediated by TGF-beta1. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2007;37:395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gellings Lowe N, Swaney JS, Moreno KM, Sabbadini RA. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and sphingosine kinase are critical for transforming growth factor-beta-stimulated collagen production by cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res 2009;82:303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]