Abstract

Purpose

To build on results of a cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a combined patient-oncologist intervention to improve communication in advanced cancer, we conducted a post hoc analysis of the patient intervention component, a previsit patient coaching session that used a question prompt list (QPL). We hypothesized that intervention-group participants would bring up more QPL-related topics, particularly prognosis-related topics, during the subsequent oncologist visit.

Patients and Methods

This cluster RCT with 170 patients who had advanced nonhematologic cancer (and their caregivers) recruited from practices of 24 participating oncologists in western New York. Intervention-group oncologists (n = 12) received individualized communication training; up to 10 of their patients (n = 84) received a previsit individualized communication coaching session that incorporated a QPL. Control-group oncologists (n = 12) and patients (n = 86) received no interventions. Topics of interest identified by patients during the coaching session were summarized from coaching notes; one office visit after the coaching session was audio recorded, transcribed, and analyzed by using linear regression modeling for group differences.

Results

Compared with controls, more than twice as many intervention-group participants brought up QPL-related topics during their office visits (70.2% v 32.6%; P < .001). Patients in the intervention group were nearly three times more likely to ask about prognosis (16.7% v 5.8%; P =.03). Of 262 topics of interest identified during coaching, 158 (60.3%) were QPL related; 20 (12.7%) addressed prognosis. Overall, patients in the intervention group brought up 82.4% of topics of interest during the office visit.

Conclusion

A combined coaching and QPL intervention was effective to help patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers identify and bring up topics of concern, including prognosis, during their subsequent oncologist visits. Considering that most patients are misinformed about prognosis, more intensive steps are needed to better promote such discussions.

INTRODUCTION

Most patients with advanced cancer say they want honest, sensitive communication about end-of-life issues.1,2 These conversations help patients and their families prepare, make informed decisions, and avoid potentially burdensome aggressive medical treatments near death.3-6 Yet, patients are often misinformed about cancer survival and curability, and those with over-optimistic prognosis estimates are more likely to die in a hospital and receive burdensome aggressive care.7,8 Patients often do not disclose their concerns and vary in the amount of information they want about the disease, prognosis, and treatment options,9-11 whereas physicians often do not know or enact patient preferences about end-of-life issues.12

Interventions to promote communication in cancer settings have targeted patients and physicians. Randomized controlled trials in early cancer and palliative care13-16 have shown that question prompt lists (QPLs) —structured lists of questions given to patients before consultations—help patients with cancer and their caregivers ask more questions, particularly if the physician also encourages and endorses the QPL. In addition, a tailored previsit educational coaching intervention (that did not involve QPLs) helped patients with cancer communicate concerns about pain.17 Meanwhile, an oncologist intervention that used audio recordings with tailored feedback positively influenced patient trust and oncologist responsiveness to patient emotions.18 Yet, no randomized trials have evaluated interventions directed toward both oncologists and their patients with advanced cancer who are not yet receiving palliative or hospice care. This phase in the disease is a crucial time to initiate discussions about prognosis and end-of-life issues, because it is still early enough to influence the clinical course of the patient.19,20

Our group recently reported the results of a cluster randomized controlled trial that used brief, individualized, skill-based training for oncologists combined with individualized communication coaching for outpatients with advanced cancer and their caregivers, when available. The coaching incorporated a QPL with suggested topics that related to current and future cancer care and end-of-life issues. The combined intervention improved communication between patients and their oncologists, which resulted in greater patient active engagement, increased physician responsiveness to patient emotions, and more discussions of prognosis and treatment choices.21,22

This secondary analysis investigates how the intervention affected the number and nature of topics brought up during an oncology office visit. We hypothesized that the intervention would result in more topics related to QPL items and more topics about the future (eg, prognosis, curability, future quality of life) brought up and subsequently discussed during the office visit. Also, we reviewed field notes from the previsit coaching session to assess which topics were identified by patients as being of interest and which topics were brought up during the subsequent oncology visit.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data for this post hoc analysis are from the intervention phase of a National Cancer Institute–sponsored multisite cluster randomized controlled trial designed to test a combined intervention to facilitate communication and decision making among oncologists, patients with advanced cancer, and their caregivers. Details of this randomized controlled trial are described elsewhere.22,23 All protocols were approved by the University of Rochester research subjects review board.

Participants

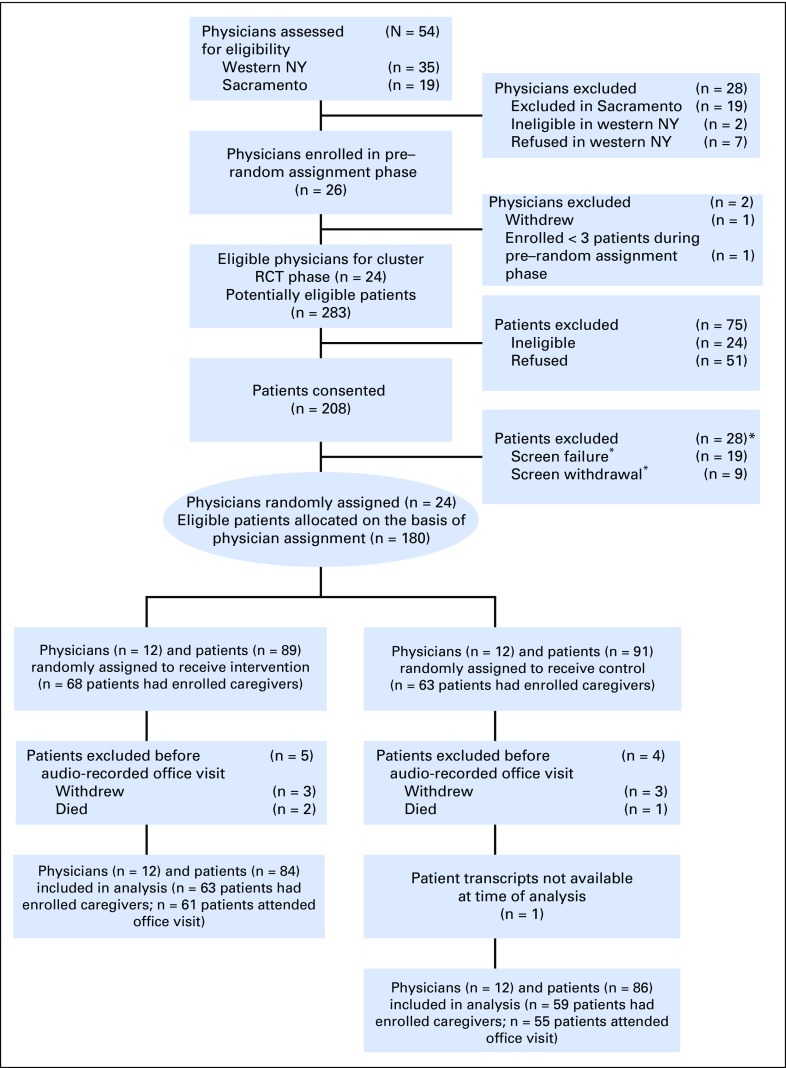

Medical oncologists caring for patients with nonhematologic cancers were recruited at practice meetings from outpatient oncology practices in western New York and Sacramento, CA. With clinic staff, research assistants reviewed clinic rosters of enrolled physicians to contact potentially eligible patients. Patients were eligible to participate if they were at least 21 years old, were able to understand spoken English and provide consent, had either stage IV nonhematologic cancer or stage III nonhematologic cancer, and had an oncologist who “would not be surprised” if the patient died within 12 months. During the intervention phase, up to a maximum of 10 patients per physician was recruited sequentially between August 2012 and June 2014 until the target sample size of 265 patients was reached. Patients were asked to identify a caregiver age 21 years or older. Patients were blinded to study arm assignment until completion of baseline measures. All participants had one audio-recorded office visit with their oncologist. Given that notes by the coaches were consistently retained only in western New York, this analysis is restricted to that site, which included nine practices that encompassed urban, suburban, and rural settings. Informed consent was obtained from all participants (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram. *Screen failure is defined as a patient who becomes ineligible after consent but before completion of the baseline survey (eg, if the patient entered hospice care); screen withdrawal is defined as a patient who gave consent but withdrew before completion of the baseline survey.

Intervention Overview

Stratified random assignment occurred at the level of the oncologist to balance assignment by study site (western NY v Sacramento) and cancer focus (> 50% breast cancer patients v other). Within strata, physicians were randomly assigned 1:1 to intervention or control. Patient assignment to intervention or control was identical to that of their oncologist. Oncologists randomly assigned to the intervention arm participated in a tailored educational intervention that involved standardized patient instructors.23 Their patients (and the informal family caregivers of each patient, if available) received individualized communication coaching with a QPL to help them identify questions and concerns to share during an upcoming oncologist visit. Both interventions were directed toward the same four key communication domains of patient-centered communication23 that are based on six core communication functions identified by the National Cancer Institute.6

Coaching and QPL Intervention

Two social workers with health care backgrounds were trained to coach intervention patients. They participated in a 3-day intensive training; their subsequent coaching sessions were audio recorded and reviewed for fidelity. Patients and caregivers in the intervention arm met face to face with a coach during a 1-hour session, during which time they were each given a QPL booklet. After the patients were asked about their backgrounds and experiences with their oncologists, coaches reviewed the QPL and then helped patients and caregivers identify and prioritize their two to three most immediate topics of interest. They also coached patients about how to ask questions or express concerns during the next office visit. For 77.4% of patients, the office visit occurred the same day as the coaching session; for 90.5%, it occurred within 3 days. Coaches wrote notes that detailed each patient’s topics of interest.

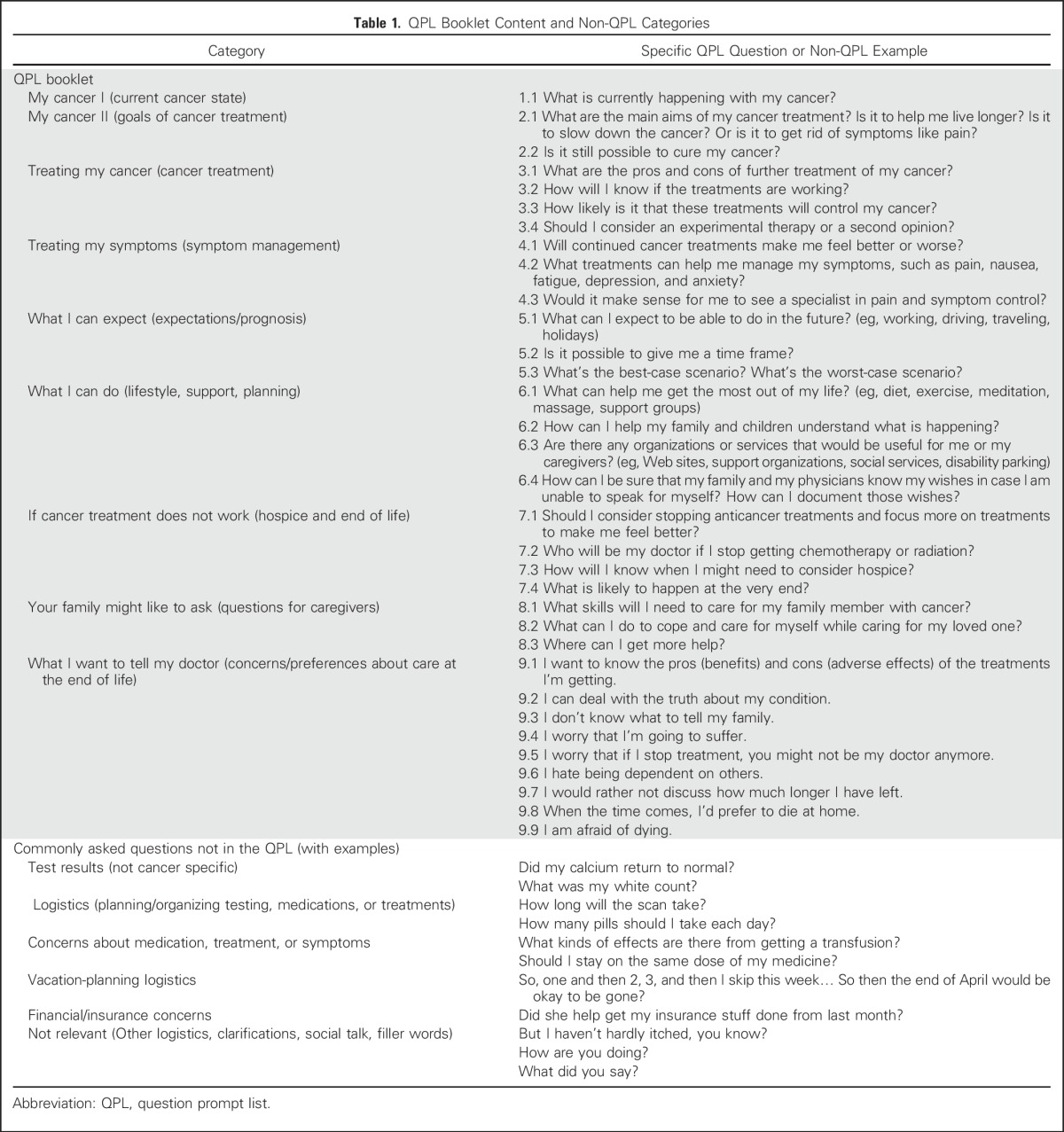

The QPL used in the study was adapted from a QPL developed in Australia for patients with cancer who were in palliative care.24,25 The QPL was subsequently refined on the basis of a focus group (n = 8) and 11 individual semistructured interviews with demographically diverse patients who had advanced cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

QPL Booklet Content and Non-QPL Categories

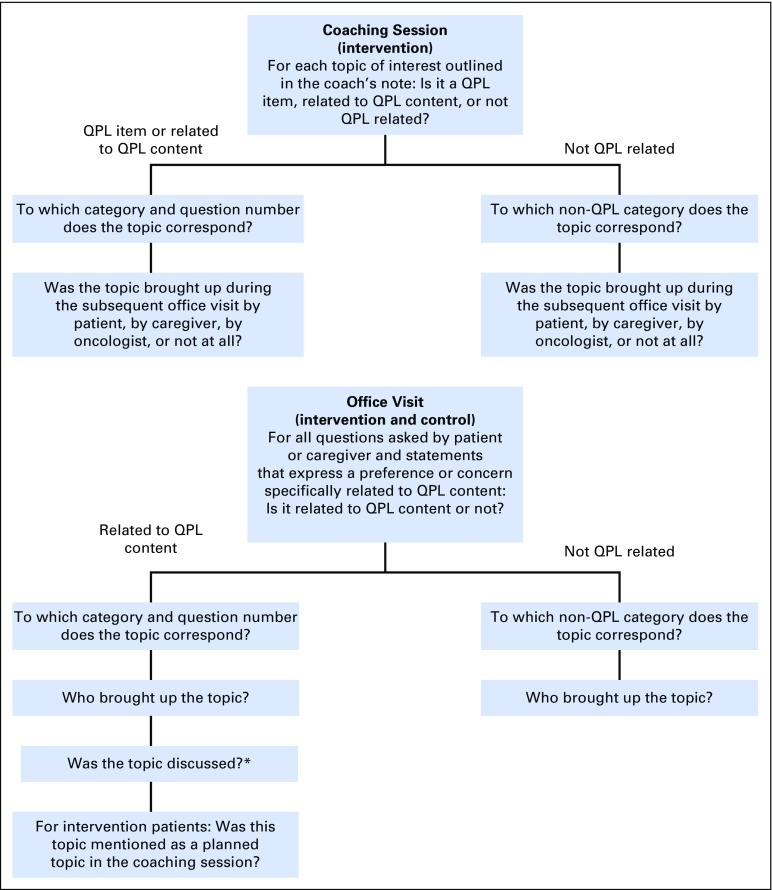

Coding

A coding manual was developed to categorize topics of interest identified during the coaching session and topics brought up during the office visit (Fig 2). These topics were coded as QPL related (either verbatim or carrying a similar intent and meaning to questions and statements contained in the QPL) or not QPL related (clearly not addressing any of the topics in the QPL).

Fig 2.

Coding algorithm to categorize topics of interest identified during the coaching session (intervention) and to categorize topics brought up during the office visit (intervention and control). *A topic was coded as discussed if the oncologist responded to the topic; the topic was coded as not discussed when the oncologist did not respond or changed the subject and did not return to the topic later in the visit.

Two researchers (R.A.R. and K.B.) each listened to five audio-recorded coaching sessions and read transcripts of five corresponding intervention oncology office visits and five control oncology office visits, from which a preliminary coding manual was developed. This coding manual was applied to data from an additional five intervention-group and five control-group patients. Differences were resolved by consensus. The coding manual was continually refined for application to both the coaching sessions and the office visit transcripts. Data from a total of 30 patients were double coded, and differences were resolved by consensus. Kappa was 0.85. The notes from coaches that concisely listed the topics of interest of each patient were validated by comparing them to audio-recorded data of the coaching session from 20 intervention-group patients; only the notes were used for final coding of the coaching sessions. The remaining data were singly coded by R.A.R. (n = 99 patients) and K.B. (n = 41 patients); questions that occurred during coding were discussed on a case-by-case basis with R.M.E.

Statistical Analysis

We compared intervention-group and control-group patients on the total number of questions asked during the office visit, the number of QPL-related topics brought up, the number of topics brought up about the future (including prognosis, likelihood of cure, end of life, and expressions of fear/avoidance), and symptoms/quality of life.

We performed descriptive analyses for the intervention group on the topics of interest identified during the coaching session and the topics subsequently brought up during the office visit. We coded them according to whether the topic was QPL related or not.

Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS (Version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Mixed-effects linear regression models were used to compare continuous outcomes between intervention and control groups, and generalized estimating equations were used for binary outcomes comparisons. The models were specified to account for the nesting of patients (the units of analysis) within physicians (the units of random assignment). Regression models included a covariable to account for the stratified randomized design (an indicator for oncologist subspecialty: breast cancer v not) and a covariable to statistically adjust for aggressive cancer (aggressive v not) in a patient.22

RESULTS

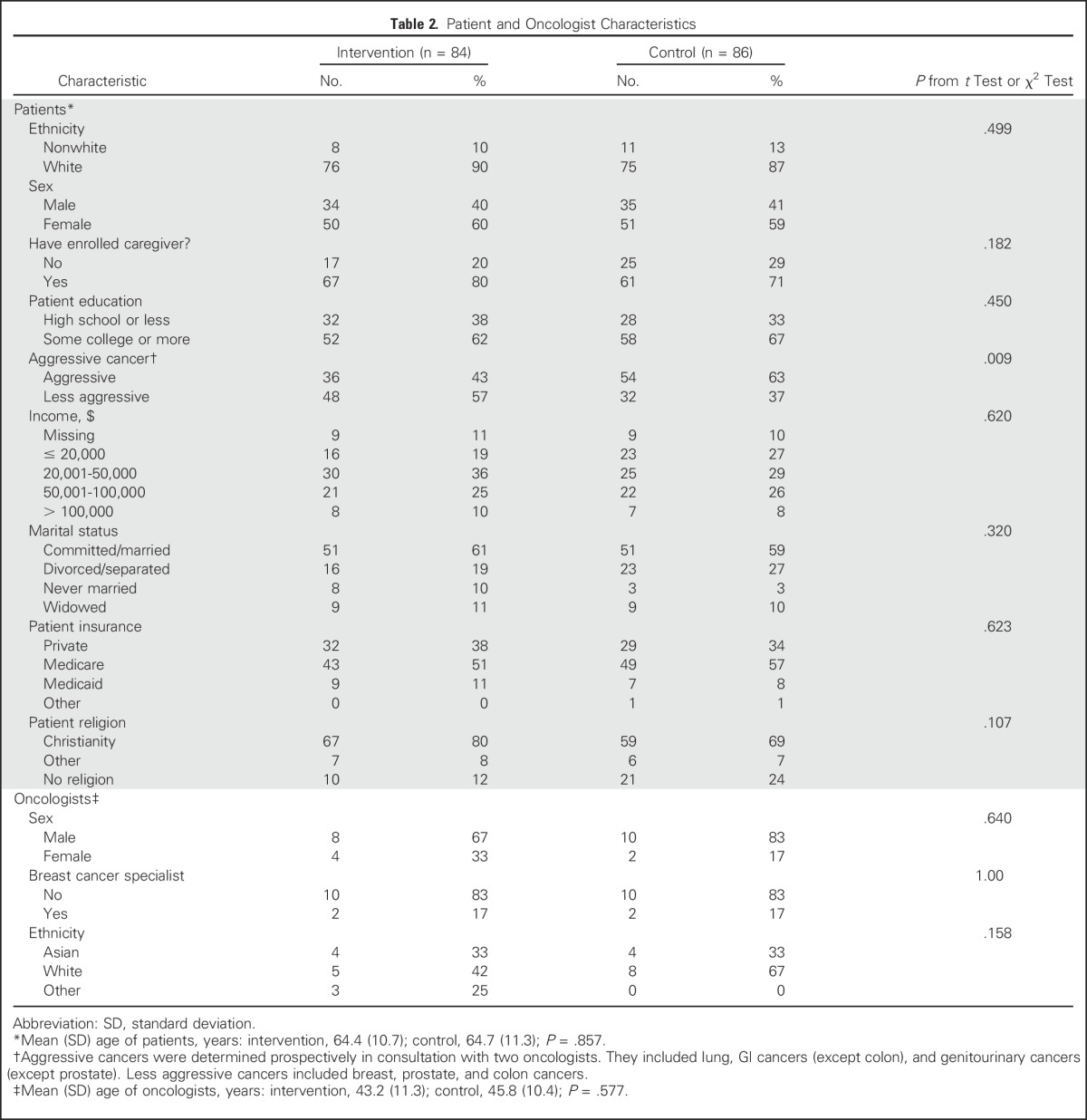

Table 2 lists characteristics of the 24 oncologists (n = 12 each in the intervention and control groups) and 170 patients (n = 84 in the intervention group; n = 86 in the control group). Caregivers were present in 72.6% and 64.0% of office visits with patients in the intervention and control groups, respectively. The transcript for one office visit of a control-group patient was not available at the time of analysis and the patient was excluded.

Table 2.

Patient and Oncologist Characteristics

Effects of Intervention on Topics Brought Up

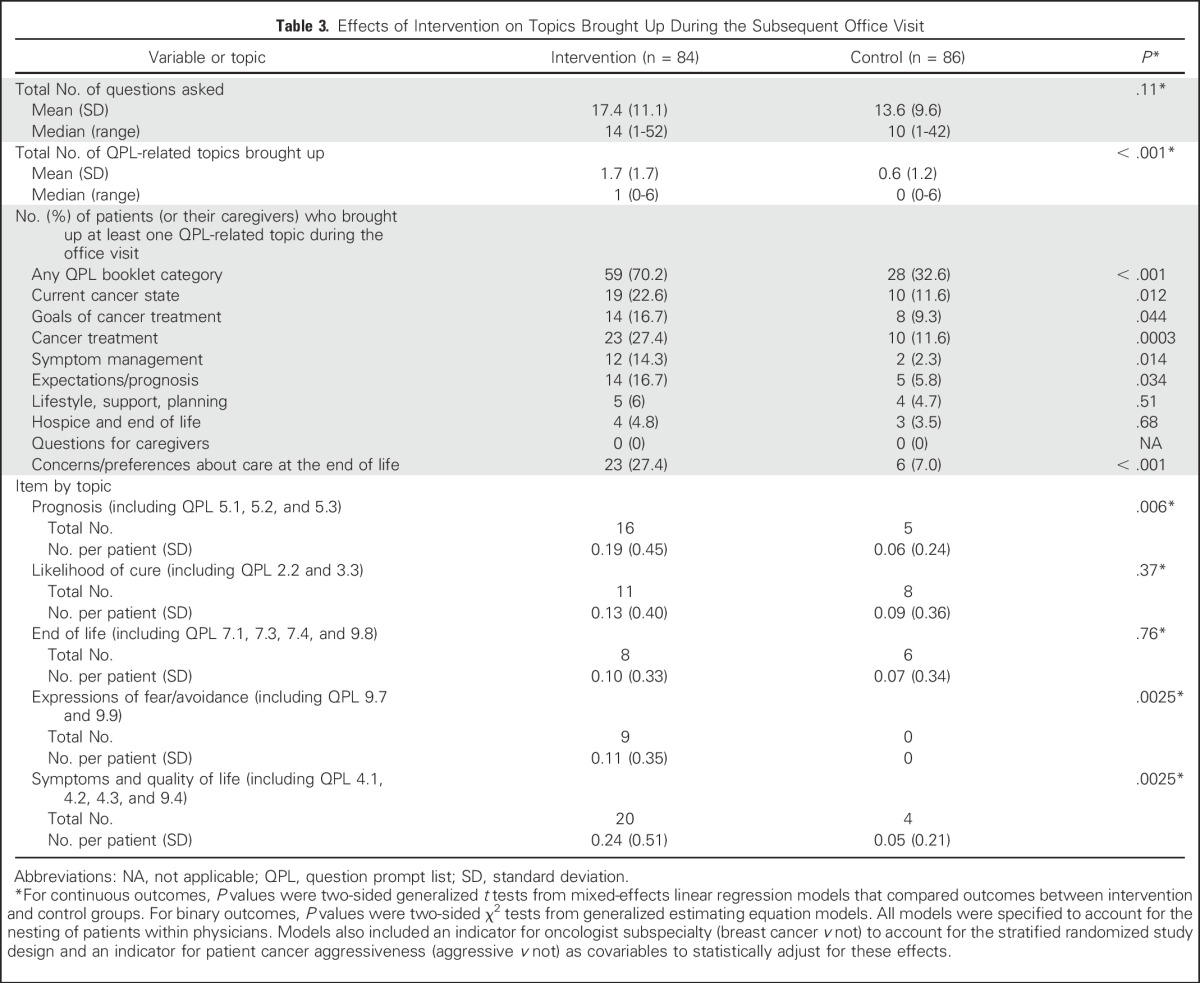

More than twice as many patients and caregivers in the intervention group as in the control group brought up QPL-related topics during their audio-recorded oncology visit (70.2% v 32.6%; P < .001; Table 3). Intervention-group patients and caregivers brought up topics that spanned the entire QPL booklet, whereas approximately one third of QPL-related topics were never broached by control-group patients and caregivers (Appendix Table A1, online only). Topics related to expectations/prognosis, current cancer state, goals of treatment, cancer treatment, symptom management, and preferences/concerns about care at the end of life were more commonly brought up during the office visit of intervention-group patients. Overall, intervention-group patients brought up significantly more topics related to expectations/prognosis than control-group patients did (P = .02). Prognosis-related discussions brought up by patients or caregivers were more frequent in the intervention group than in the control group (16.7% v 5.8%, P = .03). Of the 140 topics brought up by intervention-group patients and 55 topics brought up by control-group patients, 99.3% and 100%, respectively, were discussed with the oncologist. Representative quotations are listed in Table 4.

Table 3.

Effects of Intervention on Topics Brought Up During the Subsequent Office Visit

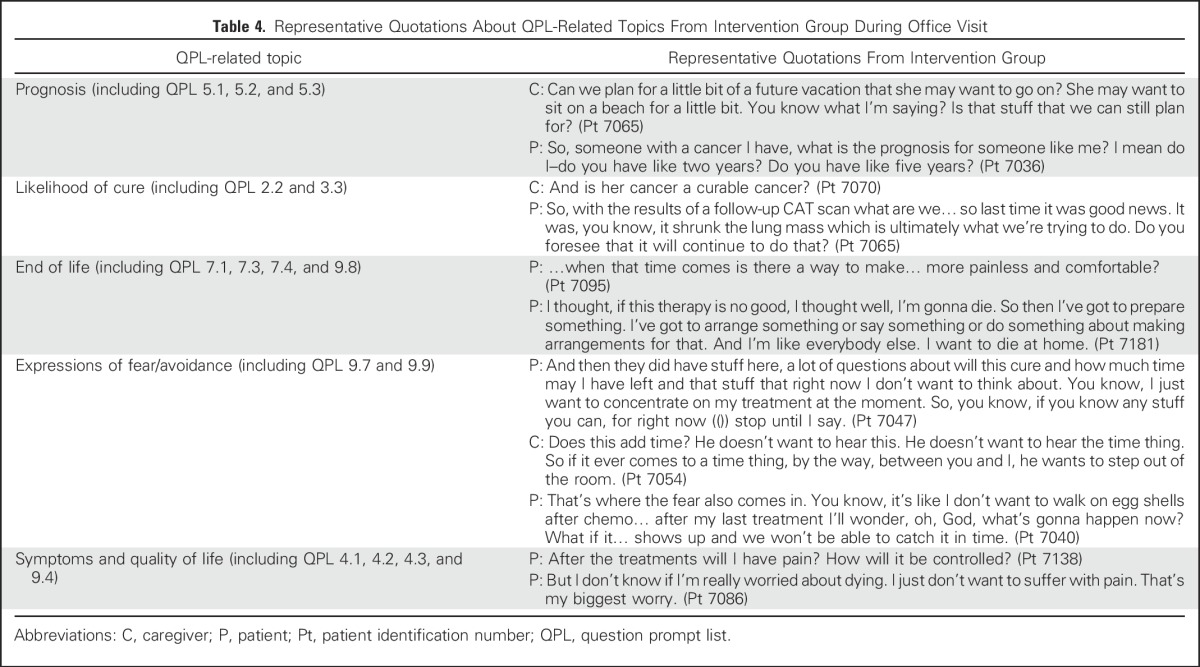

Table 4.

Representative Quotations About QPL-Related Topics From Intervention Group During Office Visit

Topics of Interest Identified During Coaching Session

Overall, the 84 intervention-group patients and their caregivers identified 262 topics of interest during their coaching session (mean, 3.1; standard deviation [SD], 1.6; range, 0 to 8); 158 (60.3%) were QPL related (mean, 1.9; SD, 1.5; range, 0 to 5; Table 5). In aggregate, almost all items from the QPL booklet were selected by at least one patient (Appendix Table A2, online only). The most commonly-selected QPL-related topics were about cancer treatment, current cancer state, and concerns/preferences about care at the end of life. Expectations/prognosis topics were selected a total of 20 times, nine of which (5.7%) were explicit requests for a time frame or prognosis, and another 11 (7.0%) were indirect, such as questions about what to expect in the future and best-case/worst-case scenarios. In addition, six patients selected explicit questions about whether the cancer was curable (3.8%), and four patients (2.5%) selected “I would rather not discuss how much longer I have left.”

Table 5.

QPL-Related Topics of Interest Identified During the Coaching Session and Subsequently Brought Up by Patient, Caregiver, or Oncologist During The Next Office Visit

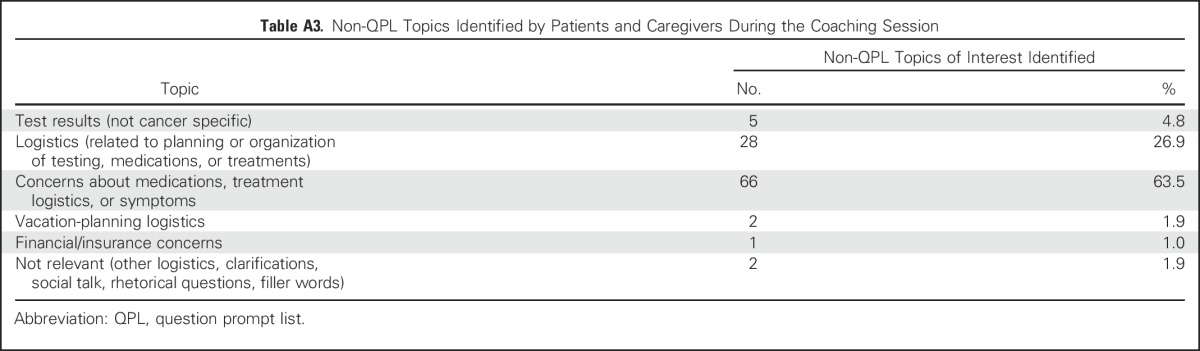

Of the 104 topics of interest identified by patients and caregivers that were not QPL related, the most common topics were about medications, treatment logistics or symptoms (63.5%), and other logistics (26.9%; Appendix Table A3, online only).

Topics of Interest From Coaching Session Brought Up During Office Visit

During the subsequent office visit, 82.4% of all topics of interest and 78.5% of QPL-related topics of interest identified during the coaching session were brought up. The patient brought up the topic most often (56.1%), followed by the physician (16.8%) or caregiver (9.5%; Table 5). For QPL-related topics, the results were similar (50.6%, 7.0%, and 20.9% initiated by patient, physician, or caregiver, respectively). Of the topics of interest related to prognosis, 80.0% were brought up during the office visit, most often by patients (Table 5; Appendix Table A2).

DISCUSSION

This cluster randomized clinical trial, which combined an oncologist communication training intervention with a previsit patient intervention that used communication coaching and a QPL, was effective to help patients with advanced cancer actively seek information and express preferences about their care. We found that patients and caregivers who received the QPL and were coached, and whose oncologists were trained to be receptive to patient questions and concerns, brought up more topics relevant to their illness and more future-oriented topics compared with control-group patient and caregivers. In particular, intervention-group patients brought up topics about prognosis three times as frequently as control-group patients. In addition, most topics of interest that patients and caregivers identified during the coaching session were brought up during the subsequent oncologist visit, including those about prognosis. Taken together, the link observed in this study between patient intentions (as revealed by topics prioritized through use of a QPL and coaching) and actions (as demonstrated through what was brought up during their subsequent office visit) suggests a possible mechanism whereby the intervention was effective. The finding that most topics of interest were brought up by patients and caregivers (rather than clinicians), coupled with the finding that oncologists nearly always responded to topics raised by patients regardless of whether they received training, suggests that discussion of topics important to patients was more a result of the patient/caregiver-targeted component of the intervention than of oncologist communication training.

Patients in this study were at a more advanced illness phase than those in previous QPL studies in oncology settings, yet they still were not in palliative care or hospice.13,26 This phase represents a time when information about disease status and prognosis is critical to decision making about future care and when it is particularly important for oncologists to understand their patients' desire for information as well as their care needs.27 Because discussion of end-of-life topics has been associated with better quality of life, lower use of potentially burdensome aggressive treatments, and lower likelihood of a hospital death,4,7 our results may be seen as a promising first step to help patients realize their treatment preferences and end-of-life goals.

Our intervention improved the likelihood of discussion of prognosis-related topics nearly threefold, from 5.8% to 16.7% of office visits. Although this finding represents an important advance in the promotion of discussions that have an effect on future treatment decisions, prognosis discussions remain infrequent. Most patients continue to have much more optimistic prognosis estimates and more unrealistic treatment expectations than their oncologists,7,8,28,29 and our intervention had no effect on these discrepancies.21 In addition, despite skilled previsit coaching that used a QPL that listed explicit and indirect ways of asking about prognosis, most patients with advanced cancer did not prioritize prognostic information, and a few expressed preferences not to discuss prognosis. The intervention also had no effect on discussions of hospice and end-of-life topics. Although one might assume that patients want prognostic information, and that oncologists represent a major stumbling block,30,31 our findings support a more nuanced explanation: In addition to physician-based factors, patient factors, including avoidance of such discussions and lack of awareness that they remain misinformed, play a role.8 Other studies have suggested that many patients are not emotionally ready to hear bad news, consider physician prognostic estimates unreliable, believe they understand their prognosis on the basis of prior discussions or internet searches, wait for their doctors to make the first move, think their doctors are unwilling to provide an estimate, or view prognostic information as irrelevant because of their unique situation or coping style.23,32 Taken altogether, a pattern in current research on communication in advanced cancer is emerging—that patients often say that they want to be well informed about their disease and prognosis1,33,34 but frequently say (not now) when offered the opportunity,28 as we observed here. This, combined with oncologists' reluctance to provide realistic prognosis estimates,30 creates a tension throughout the course of the patient’s illness. Our intervention, which comprised only a single face-to-face coaching session with a QPL in addition to oncologist training, likely was insufficiently intensive or tailored to alleviate the understandable reluctance of patients to receive prognostic information. Patients often chose to focus on smaller, immediate, or logistical issues, which possibly crowded out concerns of a bigger picture and plans for the future.35 Although this might be psychologically adaptive in the short term and reflect a sometimes healthy attitude of “one day at a time” by patients, it can hamper end-of-life planning and deprive those who want to participate actively in their care of the opportunity of doing so. Perhaps the advantages and disadvantages of receiving prognostic information need to be more explicitly explored, so patients can make a truly informed decision about requesting such information. Alternatively, psychologically based approaches to prognosis-discussion readiness may be needed to address patient-level barriers.

This study has several limitations. The intentionally integrated intervention prevented us from distinguishing among the effects of the QPL alone, the QPL plus coaching, and the training of physicians, though past research supports greater effectiveness of QPLs when endorsed by clinicians.13-16 Because we were actively looking for correspondences between the coaching session and the office visit, and because the coaching session was often referred to during the subsequent office visit by the patient and/or oncologist, it was impossible to blind coders to treatment assignments. It is also possible that topics of interest identified by intervention-group patients in the coaching session were asked in visits other than the one that we audio recorded, which potentially underestimates the effect of the study. Previous studies36 suggest that patients with advanced cancer often defer prognosis questions until very close to the time of death. We do not know if patients in this study did so. In addition, we did not attempt to assess the quality of discussions, only whether a discussion occurred. Finally, we did not prospectively identify just those office visits most likely to involve treatment decisions and prognosis discussions, such as during initial consultation or when disease progression, treatment toxicity, or decline in quality of life occurred, for which the patient intervention may have had a more powerful effect.

In a context in which patients are known to have misconceptions about their illness and prognosis, we found that patients with advanced cancer who participated in a combined QPL and coaching intervention identified key topics of interest relevant to the status of their disease, including prognosis, and that they brought up topics relevant to disease status and prognosis more often than control-group patients did. In this sense, our intervention appears to have been effective in giving a voice to patients and their caregivers during office visits with their oncologists. These findings are critical, because many patients may choose to make different decisions about their care when they are fully informed.7

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Mahala Ruppel for her help with manuscript preparation and submission and Daniel J. Tancredi for his contributions to data analysis.

Appendix

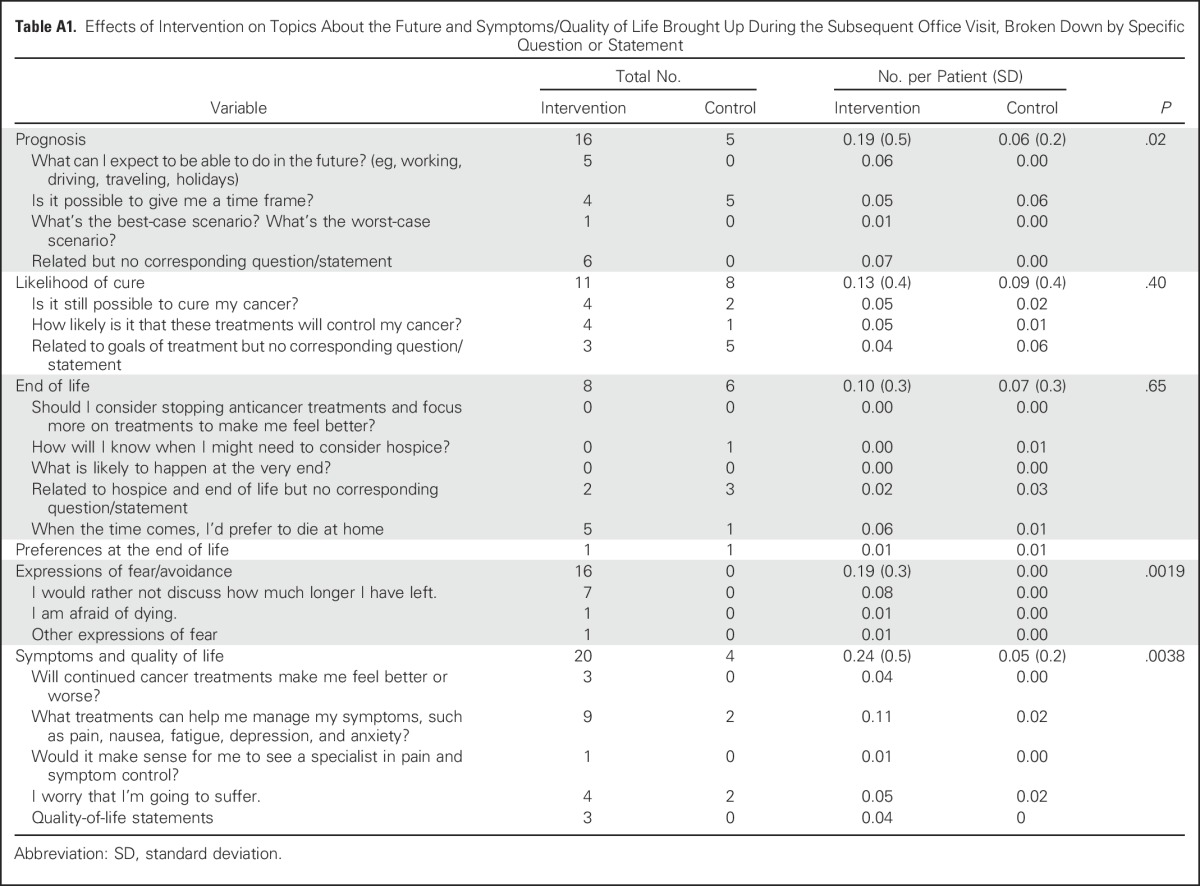

Table A1.

Effects of Intervention on Topics About the Future and Symptoms/Quality of Life Brought Up During the Subsequent Office Visit, Broken Down by Specific Question or Statement

Table A2.

QPL-Related Topics Identified During the Coaching Session and Subsequently Brought Up During the Next Office Visit, Broken Down by Specific Question or Statement

Table A3.

Non-QPL Topics Identified by Patients and Caregivers During the Coaching Session

Footnotes

Supported by grant No. R01 CA140419-05 from the National Cancer Institute (to co-principal investigators R.M.E. and R.L.K.); by a fellowship from the University of Rochester Offices for Medical Education (to R.A.R.); and by grant No. R01 CA168387 from the National Cancer Institute (to P.R.D.).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Rachel A. Rodenbach, Kim Brandes, Kevin Fiscella, Richard L. Kravitz, Phyllis N. Butow, Adam Walczak, Paul R. Duberstein, Peter Sullivan, Beth Hoh, Sandy Plumb, Ronald M. Epstein

Financial Support: Richard L. Kravitz

Collection and assembly of data: Rachel A. Rodenbach, Paul R. Duberstein, Peter Sullivan, Beth Hoh, Sandy Plumb, Ronald M. Epstein

Data analysis and interpretation: Rachel A. Rodenbach, Kim Brandes, Kevin Fiscella, Richard L. Kravitz, Phyllis N. Butow, Paul R. Duberstein, Peter Sullivan, Guibo Xing, Ronald M. Epstein

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Promoting End-of-Life Discussions in Advanced Cancer: Effects of Patient Coaching and Question Prompt Lists

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Rachel A. Rodenbach

No relationship to disclose

Kim Brandes

No relationship to disclose

Kevin Fiscella

No relationship to disclose

Richard L. Kravitz

No relationship to disclose

Phyllis N. Butow

No relationship to disclose

Adam Walczak

No relationship to disclose

Paul R. Duberstein

No relationship to disclose

Peter Sullivan

No relationship to disclose

Beth Hoh

No relationship to disclose

Guibo Xing

No relationship to disclose

Sandy Plumb

No relationship to disclose

Ronald M. Epstein

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: Patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, et al. Communicating with realism and hope: Incurable cancer patients’ views on the disclosure of prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1278–1288. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quill TE. Perspectives on care at the close of life: Initiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients—Addressing the “elephant in the room.”. JAMA. 2000;284:2502–2507. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge HA. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: Communication in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002;16:297–303. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm575oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein RM, Street RL Jr: Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD, National Cancer Institute, NIH, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279:1709–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butow PN, Maclean M, Dunn SM, et al. The dynamics of change: cancer patients’ preferences for information, involvement and support. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:857–863. doi: 10.1023/a:1008284006045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heaven CM, Maguire P. Disclosure of concerns by hospice patients and their identification by nurses. Palliat Med. 1997;11:283–290. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leydon GM, Boulton M, Moynihan C, et al. Cancer patients’ information needs and information seeking behaviour: In depth interview study. BMJ. 2000;320:909–913. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7239.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DesHarnais S, Carter RE, Hennessy W, et al. Lack of concordance between physician and patient: Reports on end-of-life care discussions. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:728–740. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown RF, Butow PN, Dunn SM, et al. Promoting patient participation and shortening cancer consultations: A randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1273–1279. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:715–723. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimoska A, Tattersall MH, Butow PN, et al. Can a “prompt list” empower cancer patients to ask relevant questions? Cancer. 2008;113:225–237. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandes K, Linn AJ, Butow PN, et al. The characteristics and effectiveness of Question Prompt List interventions in oncology: A systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2015;24:245–252. doi: 10.1002/pon.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Street RL, Jr, Slee C, Kalauokalani DK, et al. Improving physician-patient communication about cancer pain with a tailored education-coaching intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, et al. Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:593–601. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-155-9-201111010-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field MJ, Cassel CK. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schickedanz A. Assessing and Improving Value in Cancer Care: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G, et al: Differences of opinion or inadequate communication? Determinants of patient-oncologist prognostic discordance in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 2:1421-1426, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, et al: A cluster randomized trial of a patient-centered communication intervention in advanced cancer: The Values and Options in Cancer Care (VOICE) study. JAMA Oncol 3:92-100, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Hoerger M, Epstein RM, Winters PC, et al. Values and options in cancer care (VOICE): Study design and rationale for a patient-centered communication and decision-making intervention for physicians, patients with advanced cancer, and their caregivers BMC Cancer 13188, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walczak A, Mazer B, Butow PN, et al. A question prompt list for patients with advanced cancer in the final year of life: Development and cross-cultural evaluation. Palliat Med. 2013;27:779–788. doi: 10.1177/0269216313483659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walczak A, Butow PN, Clayton JM, et al: Discussing prognosis and end-of-life care in the final year of life: A randomised controlled trial of a nurse-led communication support programme for patients and caregivers. BMJ Open 4:e005745-2014-005745, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Butow PN, Dunn SM, Tattersall MH, et al. Patient participation in the cancer consultation: Evaluation of a question prompt sheet. Ann Oncol. 1994;5:199–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Street RL, Jr, Haidet P. How well do doctors know their patients? Factors affecting physician understanding of patients’ health beliefs. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:21–27. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1453-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kutner JS, Steiner JF, Corbett KK, et al. Information needs in terminal illness. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1341–1352. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu PH, Landrum MB, Weeks JC, et al. Physicians’ propensity to discuss prognosis is associated with patients’ awareness of prognosis for metastatic cancers. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:673–682. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Prognostic disclosure to patients with cancer near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1096–1105. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedrichsen M, Milberg A. Concerns about losing control when breaking bad news to terminally ill patients with cancer: Physicians’ perspective. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:673–682. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walczak A, Henselmans I, Tattersall MH, et al. A qualitative analysis of responses to a question prompt list and prognosis and end-of-life care discussion prompts delivered in a communication support program. Psychooncology. 2015;24:287–293. doi: 10.1002/pon.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fallowfield L, Ford S, Lewis S. No news is not good news: Information preferences of patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 1995;4:197–202. doi: 10.1002/pon.2960040305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirk P, Kirk I, Kristjanson LJ.What do patients receiving palliative care for cancer and their families want to be told? A Canadian and Australian qualitative study BMJ 3281343, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The AM, Hak T, Koëter G, et al. Collusion in doctor-patient communication about imminent death: An ethnographic study. BMJ. 2000;321:1376–1381. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7273.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–2326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]