Abstract

Purpose

This study used population-based data to estimate the percentage of cancer survivors in the United States reporting current medication use for anxiety and depression and to characterize the survivors taking this type of medication. Rates of medication use in cancer survivors were compared with rates in the general population.

Methods

We analyzed data from the National Health Interview Survey, years 2010 to 2013, identifying cancer survivors (n = 3,184) and adults with no history of cancer (n = 44,997) who completed both the Sample Adult Core Questionnaire and the Adult Functioning and Disability Supplement.

Results

Compared with adults with no history of cancer, cancer survivors were significantly more likely to report taking medication for anxiety (16.8% v 8.6%, P < .001), depression (14.1% v 7.8%, P < .001), and one or both of these conditions combined (19.1% v 10.4%, P < .001), indicating that an estimated 2.5 million cancer survivors were taking medication for anxiety or depression in the United States at that time. Survivor characteristics associated with higher rates of medication use for anxiety included being younger than 65 years old, female, and non-Hispanic white, and having public insurance, a usual source of medical care, and multiple chronic health conditions. Survivor characteristics associated with medication use for depression were largely consistent with those for anxiety, with the exceptions that insurance status was not significant, whereas being widowed/divorced/separated was associated with more use.

Conclusion

Cancer survivors in the United States reported medication use for anxiety and depression at rates nearly two times those reported by the general public, likely a reflection of greater emotional and physical burdens from cancer or its treatment.

INTRODUCTION

At some point after a cancer diagnosis, many people experience psychosocial distress including feelings of sadness, fear, anxiety, and depression.1-4 A multitude of factors can arise to cause this distress, from fears of death and suffering, to changes in social roles and the physical pain caused by cancer or its treatments, to having a personal history of depression or anxiety disorders.5-6 Although some survivors might be affected minimally or temporarily, others might experience overwhelming anxiety, depression, or both, for significant periods of time,4,7,8 causing disruption and a reduced quality of life.9 If left unaddressed and untreated, anxiety and depression in cancer survivors have been found to negatively affect health behaviors, the body’s inflammatory response, and even survival.5,10-13

In recognition of the adverse consequences that psychosocial distress can have on the health and well-being of cancer survivors, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network,14 ASCO,15 and the Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons16 have all issued statements advocating for widespread distress screening and treatment of cancer survivors. In 2012, the CoC instituted this recommendation by requiring that all patients with cancer treated in CoC-accredited facilities be screened for distress as a standard part of cancer care.16 When survivors experience significant or persistent distress, a variety of psychosocial interventions or psychopharmacologic therapies can be recommended.

There is evidence that pharmacologic therapies can be safe and effective in reducing the symptoms of emotional distress in cancer survivors.17,18 There is also some indication that the use of pharmacologic therapies for treating anxiety and depression is prevalent and on the rise in cancer survivors.19,20 However, we do not know how many cancer survivors are currently using medication to treat anxiety and/or depression in the United States. A recent study in Sweden found that cancer survivors used psychiatric medications at higher rates than did cancer-free individuals,4 but comparative rates have not been investigated in the cancer survivor population in the Unites States, and we know little about the sociodemographic characteristics associated with medication use. To increase our understanding of psychotropic medication use by cancer survivors in the United States and to inform future research, this study aimed to provide population-based prevalence estimates of cancer survivors in the United States reporting medication use for anxiety and depression, to identify the characteristics of survivors most likely to be taking medication for anxiety and depression, and to compare these findings with findings in the general population.

METHODS

Data Source

This study analyzed data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS),21 combining data years 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013. The NHIS is a nation-wide, in-person, cross-sectional survey administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that gathers information on the health status of the civilian noninstitutionalized population in the United States to track progress toward achieving national health objectives. NHIS uses a multistage area probability sampling strategy and oversamples for minority race/ethnicity to achieve representative sampling of households across the United States. From each participating household, one adult is randomly selected to complete the Sample Adult Core questionnaire, which contains questions on demographics, health services, health status, and any previous cancer diagnoses.

The Adult Functioning and Disability Supplement (called the Quality of Life Supplement in 2010) is sponsored by the Washington Group on Disability Statistics and has been included in NHIS since 2010. Its purpose is to develop and test measures of adult disability and functioning, including physical and emotional health, in various domains. In alternating survey years, either 25% or 50% of participants completing the Sample Adult Core questionnaire are randomly selected to also complete the Adult Functioning and Disability Supplement. For this analysis, we selected respondents who completed both the Sample Adult Core questionnaire and the Adult Functioning and Disability Supplement in a given year of NHIS participation.

Measures

Medication use.

As part of the Adult Functioning and Disability Supplement, participants were asked whether they currently took medication “for depression” (yes/no). A separate question asked whether they currently took medication “for feeling worried, nervous, or anxious” (yes/no). We looked at two separate outcomes: (1) taking medication for anxiety, whether for anxiety alone or also for depression, and (2) taking medication for depression, whether for depression alone or also for anxiety.

Sociodemographic and health-related characteristics.

Sociodemographic characteristics used in this study included age, sex, race and ethnicity, marital status, and education. Health-related characteristics included insurance status and type (ie, private, public only, or none/single service only) and having a usual source for medical care (yes/no). Noncancer comorbidity burden was defined by the number of chronic health conditions reported (eg, hypertension, stroke, diabetes, arthritis), consistent with previous research.22,23

Cancer history.

Cancer survivor status was assessed through the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had cancer or a malignancy of any kind?” A positive response was followed by an opportunity to specify up to three different cancer diagnoses. Respondents were asked their age at the time of each cancer diagnosis. All cancer survivors were postdiagnosis, but some could have been receiving cancer treatment at the time of the survey.

Data Analysis

Our analysis excluded participants who reported only a diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer or an unknown type of skin cancer. Among cancer survivors, if more than one cancer was reported, we chose the cancer type corresponding to the most recent cancer diagnosis in our analysis. Consistent with previous research, cancers with a relative 5-year survival of < 25% (ie, esophagus, liver, gall bladder, lung, pancreas, and stomach) were combined as “short survival cancers.”23 Time since most recent cancer diagnosis (in years) was calculated by subtracting age at most recent diagnosis from age at time of survey. Insurance categories “none” and “private” were combined in the multivariable regression analyses because their relationships with medication use were similar and because not doing so would necessitate the suppression of some estimates for the “none” category because of small numbers and unstable estimates.

Taking medication for anxiety and taking medication for depression were examined as two separate outcomes. All analyses were performed using SAS/SUDAAN to weight survey estimates and take into account the complex sampling design of NHIS. Descriptive analyses included comparing cancer survivors and adults without cancer on sociodemographic and health-related characteristics. We provide unadjusted weighted percentages of medication use by cancer survivorship status stratified by demographic and health-related characteristics. Age-adjusted weighted percentages were used to examine medication use by cancer survivorship status and to provide estimates of the number of adults in the United States taking medication. In addition, a test of trend was performed using logistic regression to determine if medication use varied by survey year. Four separate multivariable logistic regression models provided adjusted odds ratios of medication use by participant characteristics; the four models were run for each medication use by survivorship status. We also computed weighted adjusted percentages (predicted marginals) to examine how anxiety and depression medication use varied by cancer site and time since cancer diagnosis. The predicted marginals adjusted the weighted percentages, controlling for the factors identified in the multivariable logistic regression models.

RESULTS

Analytic Sample

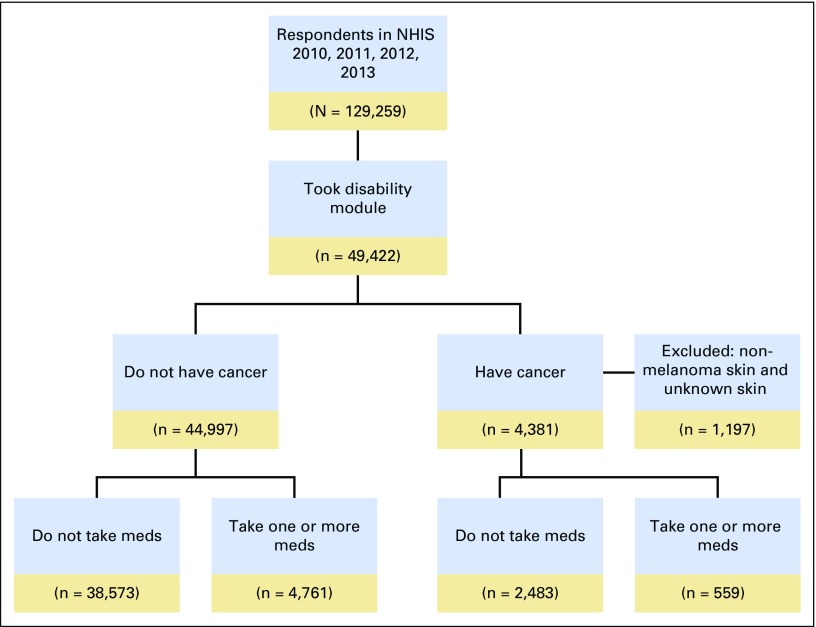

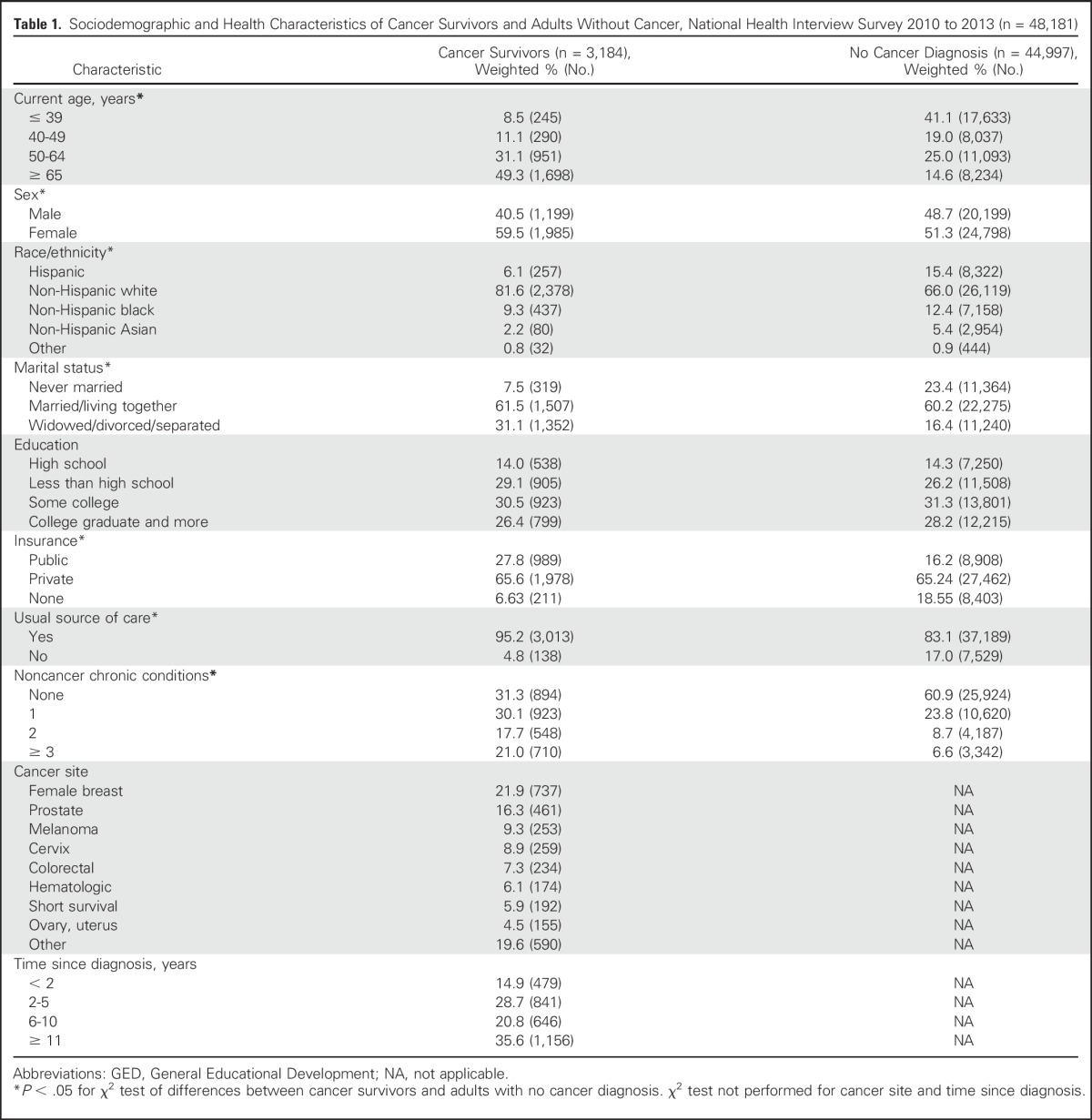

No significant differences were observed in medication use by survey year (cancer survivors: anxiety meds, P = .46, depression meds, P = .73; adults without cancer: anxiety meds, P = .79, depression meds, P = .28; data not shown); therefore, we combined NHIS data for years 2010 through 2013 for our analysis. Applying our exclusion criteria resulted in an analytic sample size of 48,181, consisting of 3,184 cancer survivors and 44,997 adults without cancer. Figure 1 indicates the steps taken to identify and select the study’s final analytic sample. Sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of cancer survivors and adults without cancer are presented in Table 1. Comparing cancer survivors with adults without cancer, χ2 tests revealed significant differences in age (χ2 = 201.41; P < .001), sex (χ2 = 26.27; P < .001), race/ethnicity (χ2 = 58.23; P < .001), marital status (χ2 = 145.02; P < .001), insurance (χ2 = 101.81; P < .001), usual source of care (χ2 = 264.86; P < .001), and noncancer chronic conditions (χ2 = 151.93; P < .001).Among cancer survivors, the most common cancer sites were female breast (21.9%) and prostate (16.3%).

Fig 1.

National Health Interview Survey sample flow diagram. Note that figure excludes participants for whom cancer history or current anxiety or depression medication use information was missing. Meds, medications for anxiety or depression.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics of Cancer Survivors and Adults Without Cancer, National Health Interview Survey 2010 to 2013 (n = 48,181)

Medication Use

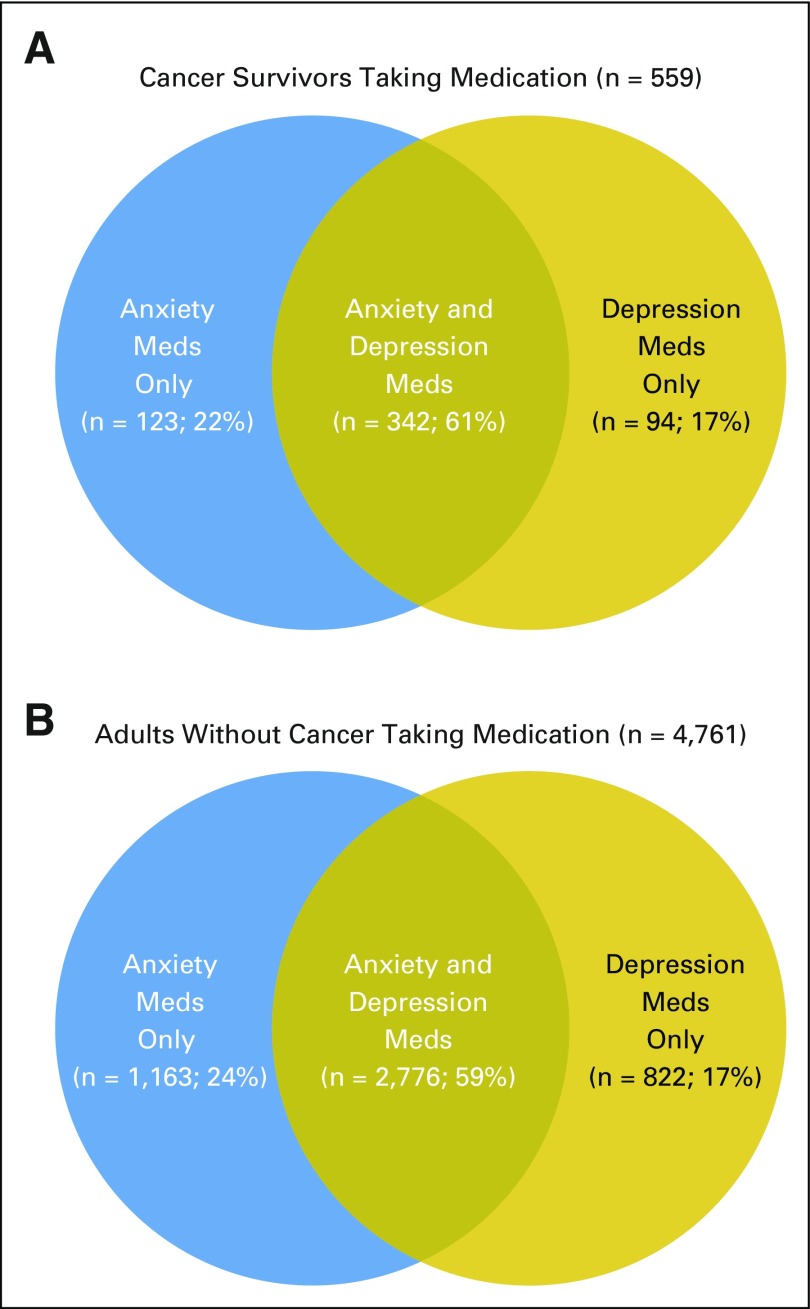

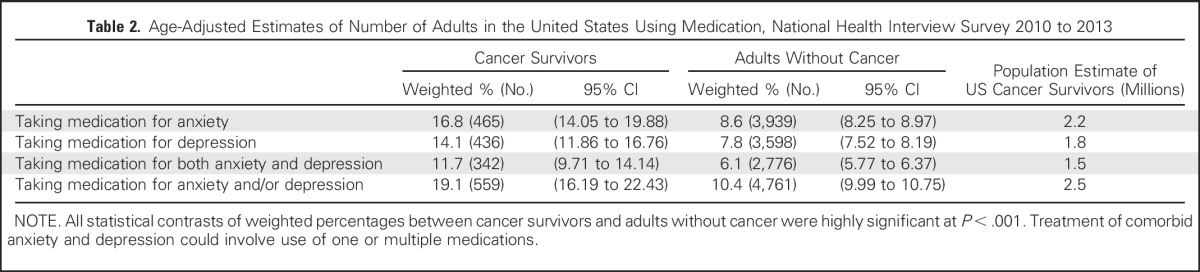

Age-adjusted, weighted percentages depicting medication use for anxiety and depression by cancer survivor status are displayed in Table 2. Compared with adults without cancer, cancer survivors were significantly more likely to report taking medication for anxiety (16.8% v 8.6%, P < .001), depression (14.1% v 7.8%, P < .001), both anxiety and depression (11.8% v 6.1%, P < .001), and one or both of these conditions (19.1% v 10.3%, P < .001). An estimated 2.5 million cancer survivors in the United States were taking medication for anxiety or depression. The overlap of medication use for depression and anxiety is illustrated in Venn diagrams in Figures 2A and 2B. Sixty-one percent of cancer survivors taking medication for either depression or anxiety report taking medication for both, and this overlap is 59% in adults without cancer.

Table 2.

Age-Adjusted Estimates of Number of Adults in the United States Using Medication, National Health Interview Survey 2010 to 2013

Fig 2.

Venn diagram depicting overlap of medication use for anxiety and depression in (A) cancer survivors who report taking medication(s) and (B) adults without cancer who report taking medication(s). National Health Interview Survey 2010 to 2013. Meds, medications.

Predictors of Taking Medication for Anxiety

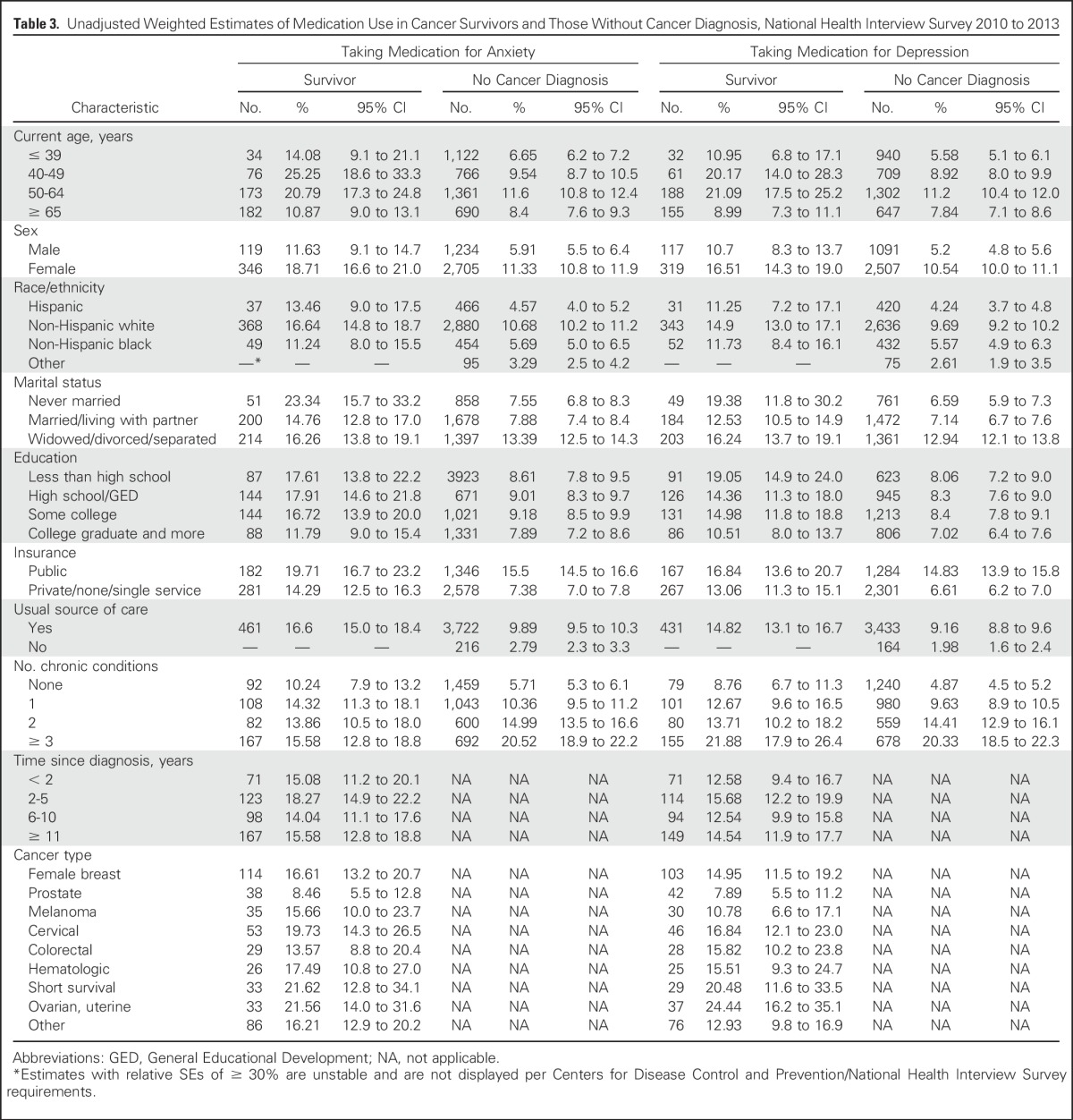

Unadjusted estimates of anxiety medication use by demographic and health-related characteristics in cancer survivors and adults without cancer are found in Table 3. Among cancer survivors, the lowest percentages of medication use for anxiety (ie, < 10%) were seen in those with a history of prostate cancer, whereas the highest rates (ie, > 20%) were seen in survivors who were 40 to 64 years old, those who were never married, and those who had a history of ovarian, uterine, or short survival cancers.

Table 3.

Unadjusted Weighted Estimates of Medication Use in Cancer Survivors and Those Without Cancer Diagnosis, National Health Interview Survey 2010 to 2013

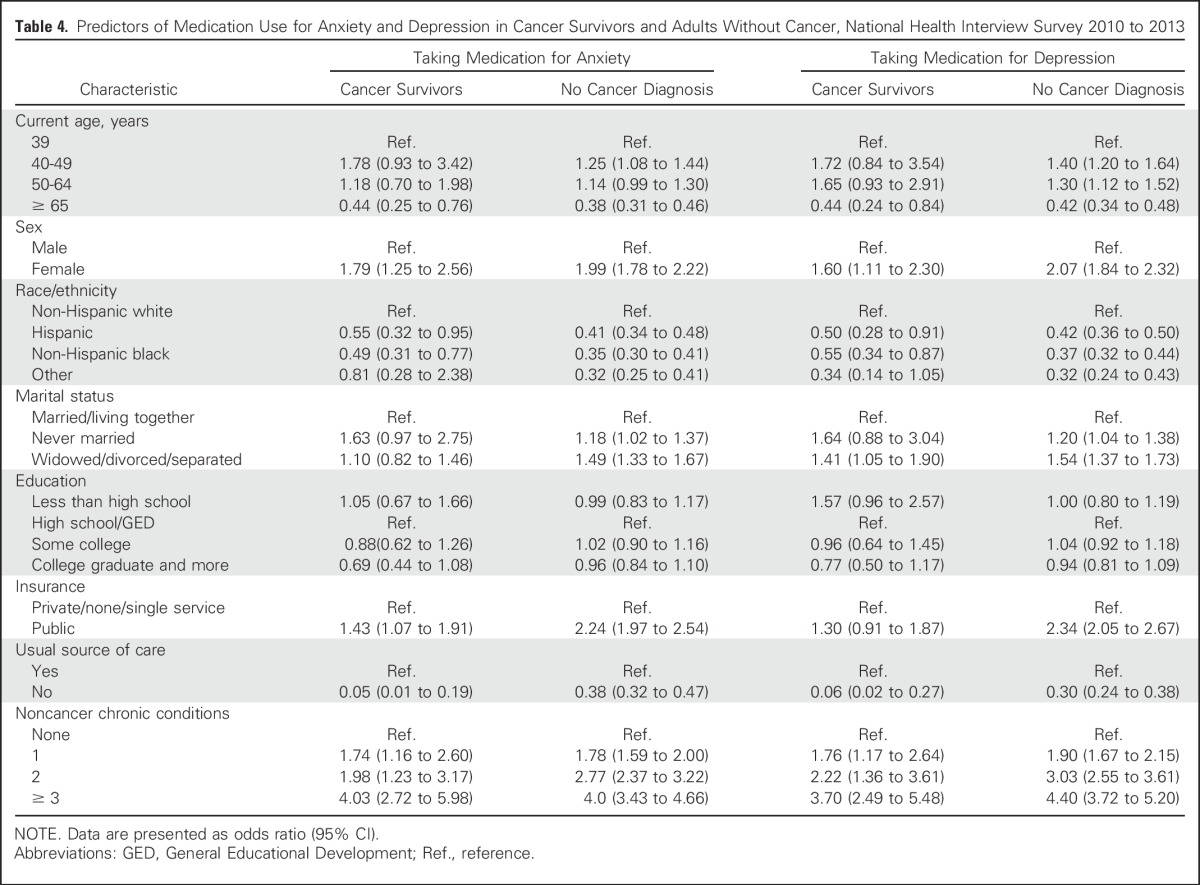

Results of the logistic regression modeling of medication use for anxiety by participant characteristics are found in Table 4. Among cancer survivors, medication use for anxiety was more likely in women, those with public insurance, and those with one or more noncancer chronic conditions, compared with those with none. In contrast, medication use for anxiety was less likely in non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic whites, in those without a usual source of care, and in those 65 years of age and older.

Table 4.

Predictors of Medication Use for Anxiety and Depression in Cancer Survivors and Adults Without Cancer, National Health Interview Survey 2010 to 2013

Among adults without cancer, medication use for anxiety was more likely in those 40 to 49 years of age and less likely in those 65 years of age and older, compared with those 39 years of age or younger; it was more likely in women, non-Hispanic whites, those never married or widowed/divorced/separated, those with public insurance, and those with a usual source of care. Use also increased with increases in the number of chronic health conditions reported.

Predictors of Taking Medication for Depression

Unadjusted estimates of depression medication use by demographic and health-related characteristics in cancer survivors and adults without cancer are found in Table 3. Among cancer survivors, the lowest percentages of medication use for depression (ie, < 10%) were seen in those 65 years of age and older, those with no additional chronic conditions, and those with a history of prostate cancer, whereas the highest rates (ie, > 20%) were seen in survivors who were 40 to 64 years old, those who had three or more chronic conditions, and those with a history of ovarian, uterine, or short survival cancers.

Results of the logistic regression modeling revealed that in cancer survivors, increased odds of taking medication for depression were seen in those who were female, non-Hispanic white, widowed/divorced/separated; those with a usual source of medical care, and those with a higher number of noncancer chronic health conditions. Use was less likely in those 65 years of age and older.

Among adults without cancer, medication use for depression was most likely in those 40 to 64 years of age, and least likely in those 65 years of age and older; it was more likely in those who were female, those who were non-Hispanic white, those who were never married or widowed/divorced/separated, those with public insurance, those with a usual source of care, and those with a greater number of chronic health conditions.

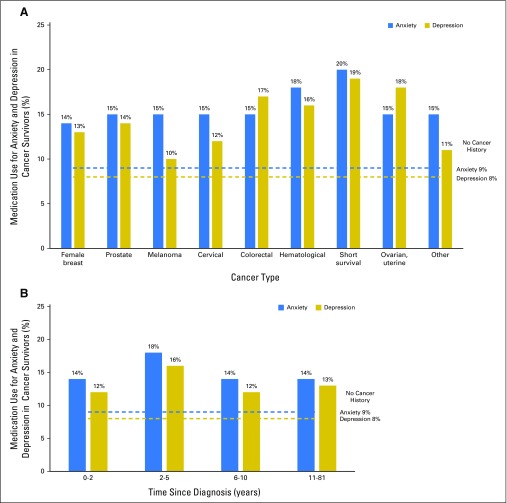

Appendix Figure A1 (online only) represents estimates from the logistic regression models, highlighting the prevalence of medication use for anxiety and depression, by cancer site and time since diagnosis, as compared with findings in adults without a history of cancer.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis indicates that cancer survivors are taking medication for anxiety and depression at rates nearly double that of the general population. Between 2010 and 2013, an estimated 2.5 million cancer survivors were using medication to treat anxiety, depression, or both conditions in the United States. Of survivors who reported taking medication for either depression or anxiety, the majority reported taking medication for both conditions. This pattern of treating comorbid anxiety and depression was also observed in adults without cancer.

Several survivor characteristics associated with the greatest use of medication for anxiety and depression, including being female, non-Hispanic white, and under the age of 65 years, and having chronic health conditions, closely mirror the characteristics found previously to correlate with higher rates of anxiety disorder and depression after cancer24 and with lower quality of life in cancer survivors.25,26 Interestingly, medication use did not vary significantly by time since cancer diagnosis, which is consistent with recent research that has shown elevated rates of depression and mental disorders for cancer survivors as much as 10 years after diagnosis.4 Characteristics associated with medication use in cancer survivors were similar to those observed in adults without cancer. Having a usual source of medical care was predictive of medication use in both groups, which likely reflects having easier access to providers, and thus, prescription medications of all types. It is worth noting that a greater proportion of cancer survivors reported having a usual source of care than did adults without cancer, which could play a role in their comparatively higher rates of medication use.

Among cancer survivors, the highest rates of medication use (ie, > 20%) were observed in those who were in middle age (ie, 40 to 64 years of age); reported never being married (anxiety medication only); had three or more chronic health conditions (depression only); and reported short survival cancers, ovarian cancer, or uterine cancer. However, survivors of all cancer types reported higher rates of medication use for anxiety and depression than did adults without a history of cancer.

Although this study provides novel, population-based estimates of the number of cancer survivors taking medications for anxiety and depression in the United States, several limitations should be noted. First, data are self-reported, and information about the onset or duration of medication use is not available in NHIS. Thus, we could not verify medication use, determine when survivors began taking medications, nor determine whether medications were initiated before or after a cancer diagnosis. It is possible that there could be error in our estimates of antidepressant and anxiolytic drug use, because these medications are often prescribed for purposes other than anxiety and depression (eg, hot flashes, sleep disturbances). We also do not know whether participants who reported taking medication were ever diagnosed with an anxiety disorder or clinically significant depression. Furthermore, we do not have information on which medications were being taken, whether the medications were prescribed by a physician, or whether they were being taken according to guidelines. For respondents who reported taking medication for anxiety and depression, we do not know whether these comorbid conditions were treated with multiple medications or one single medication. Although some previous research has benefitted from access to survivors’ prescription records to determine the type and precise amount of medications prescribed,27 the current method offers the benefit of obtaining respondents’ direct reports of medications that they are currently taking. In the creation of age groups for the analysis, because of the small sample size, adults 65 years of age and older were grouped together, and we were unable to further differentiate medication use in this wide age group. However, data indicate that the use of antidepressant and antianxiety medication decreased with increasing age. Finally, we have no information on whether survivors who were taking medication for anxiety or depression were receiving other types of psychosocial care in addition to pharmacologic treatment. Guidelines from ASCO and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network stress the importance and efficacy of using both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions (ie, dual treatment) to treat anxiety, depression, and other symptoms of emotional distress, because dual treatment has been shown to be more effective than using one treatment method only.28,29

In conclusion, our findings indicate that in adult cancer survivors in the United States, 19.1% (approximately 2.5 million survivors) are taking medication for anxiety or depression, a rate nearly double that found in the general noncancer public. Placed in the context of previous research, which found that 31% of cancer survivors in the United Sates sought help for psychosocial concerns by discussing them with their medical provider,22 our estimate of medication use is more modest and could suggest that even more survivors might benefit from pharmacologic treatment than were receiving treatment at the time of this study. Nevertheless, the observed rate of medication use in cancer survivors likely reflects a combination of factors that could include survivors’ increased likelihood of having a usual source of care (and access to prescription medications) and an elevated number of physical and emotional burdens after cancer, which seem to follow survivors for many years after diagnosis. Although our estimates provide benchmarks for the rates of psychotropic medication use in survivors, they can also inform future research seeking to assess the connections among cancer, medication use, and mental health. Future work could determine whether survivors taking these medications are also receiving other forms of psychosocial treatment and support and whether cancer survivors are monitored adequately or screened over time to assess their changing psychosocial needs. Efforts to improve the psychosocial care of cancer survivors will be aided by continued tracking of the treatment received for mental health. Good medical care requires systematic evaluation, screening for new problems, and making adjustments to the prescribed therapies as needed, and survivors’ mental health deserves the same detailed, evidence-based, and ongoing attention.

Appendix

Fig A1.

(A) Adjusted estimates from logistic regression models of medication use for anxiety and depression in cancer survivors by cancer type, as compared with adults without cancer, National Health Interview Survey 2010 to 2013. Blue dashed line represents the percentage of adults without cancer taking medication for anxiety. Gold dashed line represents the percentage of adults without cancer taking medication for depression. (B) Adjusted estimates of medication use for anxiety and depression in cancer survivors by time since diagnosis, as compared with adults without cancer, National Health Interview Survey 2010 to 2013. Blue dashed line represents the percentage of adults without cancer taking medication for anxiety. Gold dashed line represents the percentage of adults without cancer taking medication for depression.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Nikki A. Hawkins, Ashwini Soman, Natasha Buchanan Lunsford, Juan L. Rodriguez

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Use of Medications for Treating Anxiety and Depression in Cancer Survivors in the United States

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Nikki A. Hawkins

No relationship to disclose

Ashwini Soman

No relationship to disclose

Natasha Buchanan Lunsford

No relationship to disclose

Steven Leadbetter

No relationship to disclose

Juan L. Rodriguez

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Jones SM, LaCroix AZ, Li W, et al. Depression and quality of life before and after breast cancer diagnosis in older women from the Women’s Health Initiative. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9:620–629. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0438-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman KE, McCarthy EP, Recklitis CJ, et al. Psychological distress in long-term survivors of adult-onset cancer: Results from a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1274–1281. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004:57–71. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu D, Andersson TM, Fall K, et al. Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders immediately before and after cancer diagnosis: A nationwide matched cohort study in Sweden. JAMA Oncol. 2:1188–1196. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0483. Epub ahead of print, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fann JR, Thomas-Rich AM, Katon WJ, et al. Major depression after breast cancer: A review of epidemiology and treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:112–126. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Syrjala KL, Jensen MP, Mendoza ME, et al. Psychological and behavioral approaches to cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1703–1711. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao G, Okoro CA, Li J, et al. Current depression among adult cancer survivors: Findings from the 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, et al. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:721–732. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70244-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu HS, Harden JK. Symptom burden and quality of life in survivorship: A review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38:E29–E54. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: A meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:171–186. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stark D, Kiely M, Smith A, et al. Anxiety disorders in cancer patients: Their nature, associations, and relation to quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3137–3148. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1797–1810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, et al. Distress management. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:190–209. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen BL, DeRubeis RJ, Berman BS, et al. Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1605–1619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Surgeons . Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker J, Sawhney A, Hansen CH, et al. Treatment of depression in adults with cancer: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Psychol Med. 2014;44:897–907. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grassi L, Caruso R, Hammelef K, et al. Efficacy and safety of pharmacotherapy in cancer-related psychiatric disorders across the trajectory of cancer care: A review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26:44–62. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2013.842542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisch MJ, Zhao F, Manola J, et al. Patterns and predictors of antidepressant use in ambulatory cancer patients with common solid tumors. Psychooncology. 2015;24:523–532. doi: 10.1002/pon.3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones SM, Rosenberg D, Ludman E, et al. Medical comorbidity and psychotropic medication fills in older adults with breast or prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:3005–3009. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2668-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Atlanta, GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forsythe LP, Kent EE, Weaver KE, et al. Receipt of psychosocial care among cancer survivors in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1961–1969. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, et al. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: Findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1322–1330. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, et al. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weaver KE, Forsythe LP, Reeve BB, et al. Mental and physical health-related quality of life among U.S. cancer survivors: Population estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:2108–2117. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith AW, Reeve BB, Bellizzi KM, et al. Cancer, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life of older adults. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;29:41–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desplenter F, Bond C, Watson M, et al. Incidence and drug treatment of emotional distress after cancer diagnosis: A matched primary care case-control study. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1644–1651. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulberg HC, Katon W, Simon GE, et al. Treating major depression in primary care practice: An update of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:1121–1127. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1462–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]