Abstract

Cigarette smoke (CS) exposure is known to induce proteostasis imbalance that can initiate accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins. Therefore, the primary goal of this study was to determine if first- and secondhand CS induces localization of ubiquitinated proteins in perinuclear spaces as aggresome bodies. Furthermore, we sought to determine the mechanism by which smoke-induced aggresome formation contributes to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)–emphysema pathogenesis. Hence, Beas2b cells were treated with CS extract (CSE) for in vitro experimental analysis of CS-induced aggresome formation by immunoblotting, microscopy, and reporter assays, whereas chronic CS–exposed murine model and human COPD–emphysema lung tissues were used for validation. In preliminary analysis, we observed a significant (P < 0.01) increase in ubiquitinated protein aggregation in the insoluble protein fraction of CSE-treated Beas2b cells. We verified that CS-induced ubiquitin aggregrates are localized in the perinuclear spaces as aggresome bodies. These CS-induced aggresomes (P < 0.001) colocalize with autophagy protein microtubule–associated protein 1 light chain-3B+ autophagy bodies, whereas U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved autophagy-inducing drug (carbamazepine) significantly (P < 0.01) decreases their colocalization and expression, suggesting CS-impaired autophagy. Moreover, CSE treatment significantly increases valosin-containing protein–p62 protein–protein interaction (P < 0.0005) and p62 expression (aberrant autophagy marker; P < 0.0001), verifying CS-impaired autophagy as an aggresome formation mechanism. We also found that inhibiting protein synthesis by cycloheximide does not deplete CS-induced ubiquitinated protein aggregates, suggesting the role of CS-induced protein synthesis in aggresome formation. Next, we used an emphysema murine model to verify that chronic CS significantly (P < 0.0005) induces aggresome formation. Moreover, we observed that autophagy induction by carbamazepine inhibits CS-induced aggresome formation and alveolar space enlargement (P < 0.001), confirming involvement of aggresome bodies in COPD–emphysema pathogenesis. Finally, significantly higher p62 accumulation in smokers and severe COPD–emphysema lungs (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Stage III/IV) as compared with normal nonsmokers (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Stage 0) substantiates the pathogenic role of autophagy impairment in aggresome formation and COPD–emphysema progression. In conclusion, CS-induced aggresome formation is a novel mechanism involved in COPD–emphysema pathogenesis.

Keywords: cigarette smoke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ubiquitin, aggresomes, autophagy

Clinical Relevance

We anticipate that these research findings will have a great impact on development of novel therapeutics for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease–emphysema and other diseases involving impaired proteostasis or autophagy. In addition to the therapeutic application, these findings are anticipated to have a significant impact on the prognosis of severe emphysema, as well as evaluation of effects of cigarette smoke exposure.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an obstructive lung condition in which inflammatory oxidative stress and apoptosis debilitate and destroy the lung alveoli, leading to emphysema (1, 2), and is expected to be the third-highest leading cause of death globally, by the year 2020 (3). First- and secondhand cigarette smoke (CS), and aging have been identified as the leading causes of COPD–emphysema pathogenesis, although it is unclear if they involve a common mechanism (4, 5). Furthermore, approximately one-third of adult nonsmokers have been exposed to CS, which contributes to the development of chronic obstructive lung diseases by inducing inflammation, apoptosis/senescence, and lung function decline (6–11). In fact, both CS and aging have been found to modulate protein homeostasis (proteostasis) (12–15), which leads to accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins, inflammatory-oxidative stress, and apoptosis, which are the hallmarks of COPD–emphysema pathogenesis (2, 16). Recent studies illustrate that chronic cigarette smoking promotes senescence and accelerated lung aging (4, 11, 13). In fact, the role of proteostasis imbalance in aging is relatively well described (13, 17–20). It is also important to note here that COPD–emphysema is not a monogenic disorder (except for a small percentage of subjects with α1-antitrypsin Z [ATZ] mutations) (15), and that all smokers do not develop COPD. Hence, it is highly likely that CS and aging modulate a common process, such as proteostasis, that can affect multiple cellular pathways to promote COPD–emphysema pathogenesis (15). In fact, CS and age-related proteostasis imbalance are known to modulate proteasomal degradation (13, 14, 21, 22), which can induce accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins as aggresome bodies. Aggresomes are insoluble clusters of ubiquitinated proteins that are formed as a cellular response mechanism to decreased proteasomal activity (23–27). Although this protective mechanism prevents immediate cell death, the buildup of aggresomes induces cytotoxicity, further contributing to disease pathogenesis. Hence, we hypothesized that CS-impaired proteostasis can similarly induce aggresome formation, which leads to COPD–emphysema pathogenesis. Although proteasome-mediated degradation is known to be inhibited by CS exposure, cellular machinery has checks and balances, such as autophagy, to clear off aggresomes bodies (22, 28–30). In fact, autophagy has been implicated in having a role in the pathogenesis of various lung diseases, including COPD, although the mechanism is not well understood (31, 32). Therefore, our goal here was to verify if CS translocates ubiquitinated proteins to aggresome bodies and identify the specific mechanism for aggresome formation. We anticipated that CS inhibits both proteasomal and autophagy activities to induce aggresome formation.

In summary, we verified the role and specific mechanism for CS-induced aggresome formation in COPD–emphysema. In contrast to previous studies (22, 33), we observed that CS not only modulates proteasomal activity, but also affects protein synthesis/translocation and autophagy to induce perinuclear accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins as aggresome bodies in COPD–emphysema.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of CS Extract

Fresh CS extract (CSE) was prepared by bubbling sidestream smoke from research-grade cigarettes (3R4F; University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY) into 10 ml of serum-free culture media at a rate of one cigarette per minute, immediately before use. Sidestream smoke, a major component of secondhand smoke (34), was directed at the smoke–media interface in a conical flask. The concentrated sidestream CSE was diluted in serum-free media, and was standardized to 10% CSE (optical density = 0.74 ± 0.05 [mean ± SEM]; pH ∼7.4) concentration by measuring absorbance at a wavelength of 340 nm (35, 36). These 10% CSE–containing media were used for cell culture experiments as an in vitro CS exposure model (37, 38).

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Autophagy Reporter Assays

Human bronchial epithelial cell line Beas2b and human embryonic kidney cell line HEK-293 cells were cultured at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagles medium/F12 media containing L-glutamine, 15 mM HEPES (Corning Cellgro, Manassas, VA), 10% fetal bovine serum (Corning Cellgro), and 1% penicillin, streptomycin, and amphotericin B (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). Cells were transfected with autophagy protein microtubule–associated protein 1 light chain-3B–green fluorescent protein (LC3-GFP) and/or ubiquitin–red fluorescent protein (Ub-RFP) for 24 or 48 hours using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), as previously described (14). For the final 6 hours of transfection, cells were treated with 10% CSE or 1 μM MG-132 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Total number of cells was controlled both during plating and after treatment by microscopy to capture any artifact or changes in cell proliferation/growth, et cetera. Images were captured by a Zeiss Invertscope fluorescence microscope (Thornwood, NY) using an Olympus camera and CellSens Olympus software (Waltham, MA) at room temperature with air (10×, 40×) as the imaging medium. Magnifications of the fluorescence microscope during image capturing were set at LD Plan–Achroplan (10×/0.40 Korr Phz) or LD Plan–Neo Fluar (40×/0.6× Phz Korr), with 1.6× optivar.

CS-Induced Emphysema Murine Model

All murine experiments were conducted as described in the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocols. We used age-, weight-, and sex-matched (1.5-mo-old + acute 5-d or chronic 28-wk room air/CS exposure) C57BL/6 mice (n = 3–5) for all experiments. Mice were housed in a pathogen-free environment at constant temperature and controlled day/night cycles for CS or room air exposure. Exposure procedure and treatments are further detailed in the online supplement.

Human Subject Experiments

Longitudinal lung tissue sections from both smokers and nonsmokers were acquired from the Lung Tissue Research Consortium (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Stages of COPD–emphysema are defined by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD 0, I–IV). Briefly, subjects were classified in to normal smoker (GOLD 0, n = 5), normal nonsmoker (GOLD 0, n = 10), COPD smoker (GOLD I–IV, n = 40), or COPD nonsmoker (GOLD I–IV, n = 5) groups. The human subject study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board as exempt 4, and lung function data on each subject was obtained from Lung Tissue Research Consortium centers without disclosing any identifying information. These human subject lung sections were analyzed by immunostaining and densitometry, as described in the supplemental Materials and Methods.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy and Staining

Immunofluorescence microscopy and staining procedures were performed as previously described (14, 39), and are further detailed in the online supplement.

Caspase-3/7 Activity Assay

Caspase-3/7 activity was measured using the Caspase-3/7 Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and following the manufacturer’s instructions, as described previously (40, 41).

Statistical Analysis

Data are represented as mean (±SEM), and statistical analysis was conducted using the standard Student’s t test to determine significance. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Densitometry and statistical analysis of immunoblotting results were similarly conducted using the data obtained from ImageJ software (version 1.48a; National Institutes of Health). Briefly, an equal-sized rectangle is drawn by the software and retained for each band or total Ub smear in a consistent manner to quantify density of each band/smear using this software. The densitometry analysis of immunostaining results was performed using Matlab R2009b software (Mathworks, Natick, MA) and ANOVA analysis.

Results

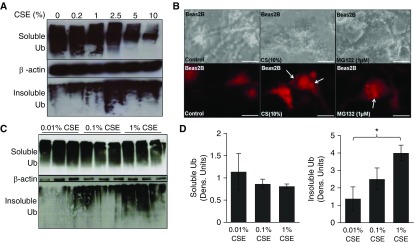

CSE Induces Perinuclear Accumulation of Ubiquitinated Proteins

Beas2b cells were treated with freshly prepared 10% CSE to identify specific mechanisms by which CS induces COPD–emphysema. CS is known to induce proteostasis imbalance, initiating accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins (14, 22). Hence, we biochemically fractioned ubiquitinated proteins to determine their cellular location, and found that CSE induces ubiquitinated protein aggregation in the insoluble protein fractions (Figure 1A, bottom panel). This increase inversely correlated with a dose-dependent decrease in the amount of ubiquitinated proteins in the soluble fractions (Figure 1A, top panel), suggesting that CS induces translocation of ubiquitinated proteins from soluble to insoluble protein fractions (aggresome bodies). The transition of ubiquitinated protein cellular localization is even more distinct when comparing low doses of CSE (Figure 1A, lanes 1–3), which accumulate ubiquitinated proteins primarily in the soluble fractions, to higher CSE doses (Figure 1A, lanes 4–6), which aggregate ubiquitinated proteins primarily in the insoluble fractions (Figure 1A). We also observed CSE-induced perinuclear localization of ubiquitinated proteins by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 1B, column 2), further confirming our hypothesis that CS potentially induces aggresome formation. MG-132, a proteasome inhibitor, was used as a positive control in this experiment to induce perinuclear Ub accumulation (Figure 1B, column 3) for comparison to CS treatment. Subsequently, we sought to determine the minimum CSE dose that can potentially induce aggresome formation to confirm application of our higher experimental dosage. We observed a significant (P < 0.05) increase in ubiquitinated protein aggregates (pellet, insoluble fraction) using 1% freshly prepared CSE (Figures 1C and 1D) as compared with 0.01% CSE, but a nonsignificant change in the soluble fraction confirmed that we appropriately choose 10% CSE as an experimental dose over lower doses. We also found that even shorter CSE treatment (10%, 3 h) shows a similar translocation of ubiquitinated proteins from soluble to insoluble fractions, although, at 6 hours of treatment, the decrease in the soluble fraction (P < 0.05) was more prominent (see Figure E1A in the online supplement). Next, we verified these results in a different cell line (HEK-293), where we observed even clearer differences (P < 0.01) in insoluble fractions of control versus CSE (10%, 6 h) treatment groups, substantiating CSE-induced aggresome formation (Figure E1B).

Figure 1.

Cigarette smoke (CS) extract (CSE) induces perinuclear ubiquitin accumulation in Beas2b cells. (A) Beas2b cells were treated with the indicated doses of freshly prepared CSE for 6 hours. Increasing CSE dose leads to greater aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins in the insoluble protein fraction (aggresome; ubiquitin [Ub] pellet, bottom panel) and decreased accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in the soluble protein fraction. More specifically, in cells treated with low doses of CSE (lanes 1–3), ubiquitinated protein is mainly in the soluble fraction (top panel; potentially in process of homeostatic proteasomal degradation), rather than in the insoluble fraction (pellet/aggresomes). In cells treated with high-dose CSE (lanes 4–6), we observed a decrease in accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in the soluble fraction (top panel), whereas aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins was elevated in the insoluble fraction (aggresome; bottom panel; lanes 4–6), suggesting translocation of ubiquitinated proteins from soluble to insoluble fractions. β-actin was used as a loading control for soluble fractions. Data suggest that, as CSE treatment strength increases, a distinct change in the localization and aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins is apparent. (B) Beas2b cells were transfected for 48 hours with Ub–red fluorescent protein (RFP) and treated with CSE (10%) or MG-132 (1 μM) for the final 6 hours of transfection. CSE treatment induced accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in perinuclear spaces (red perinuclear bodies; aggresomes, white arrows) similar to MG-132 (positive control), suggesting aggresome formation. Scale bars, 20 μm. (C) Beas2b cells were treated with indicated low doses of CSE for 6 hours. A significant (P < 0.05) translocation of ubiquitinated protein initiated at 0.1% CSE treatment. β-actin was used as a loading control for soluble fractions. (D) Densitometric analysis for C shows a trend toward a decrease in soluble ubiquitin. Even at small doses, 1% CSE shows a significant (P < 0.05) increase over 0.01% CSE of ubiquitin in the insoluble cellular fraction. CSE induces ubiquitination, translocation, and aggregation of proteins in aggresome bodies. Data are presented as mean (±SEM). *P < 0.05.

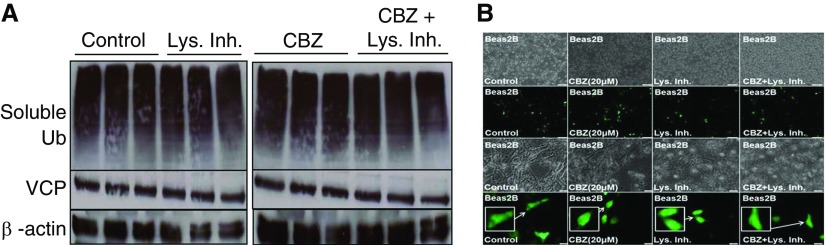

CSE Induces Aggresome Formation and Inflammation

CS has previously been shown to inhibit proteasomal activity (21, 22) as a potential mechanism for accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins (14, 22), although other degradation processes, such as autophagy, can clear off these Ub bodies (aggresomes). Hence, we suspected that CS may be inhibiting autophagy in addition to proteasomal activity to induce aggresome formation. Therefore, we used an autophagy-inducing drug, carbamazepine (CBZ), which is U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved for epilepsy and bipolar disorder (42, 43), as a tool to corroborate our hypothesis. After a short 6-hour treatment with freshly prepared 10% CSE, we observed a significant (∼11-fold; P < 0.001) increase in colocalization of LC3+ autophagy bodies with ubiquitinated proteins (Figure 2A, column 3, and Figure 2B), suggesting that CS-induced aggresome formation may involve autophagy impairment, as seen by lack of ubiquitinated protein clearance. However, we observed a mild decrease in LC3–green fluorescent protein expression with CSE treatment. Moreover, overall failure of autophagy mechanisms in clearing ubiquitinated proteins suggests that CSE impaired autophagy. In fact, we found that autophagy induction (CBZ) can significantly (P < 0.01) inhibit CSE-induced colocalization of LC3+ Ub bodies (Figure 2A, column 4, and Figure 2B), verifying our hypothesis on CS-induced aberrant autophagy. In addition, we further confirmed that CSE induces aggresome formation (Figure 2C, top and bottom panels). More specifically, we observed aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins in the insoluble fraction (pellet) after CSE treatment (Figure 2C, bottom panel) alongside reduced levels of ubiquitinated proteins in the soluble fraction (Figure 2C, top panel). This simultaneous observation suggests dose-dependent translocation of ubiquitinated proteins to the insoluble fraction. Minimal autophagy induction by CBZ (5/10 μM) during the course of 6-hour CSE treatment initiates inhibition of total ubiquitinated protein (soluble fraction) and NF-κB expression (Figure 2C), suggesting the potential of CBZ at higher doses to clear off ubiquitinated protein bodies and to control inflammation in COPD–emphysema. It has to be noted that, although short, 6-hour treatment shows some induction of NF-κB, it has no impact on NF-κB with longer overnight treatments at even higher doses (Figure 2D). We anticipate that this initial induction of NF-κB by CBZ is a homeostatic response to balance CBZ-induced autophagy, due to complex interplay between these pathways. However, CBZ can effectively override this homeostatic response at higher dose and/or longer treatment. Furthermore, after treatment with protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide (CHX), we observed similar amounts of aggregated ubiquitinated proteins in CSE- and CSE + CHX–treated cells (Figure 2C), contrary to our expectation. This result suggests the role of CSE in inducing protein synthesis, which offsets the inhibition of protein synthesis by CHX that potentially alleviates ubiquitinated protein accumulation, resulting in minimal overall difference in ubiquitinated protein levels (Figure 2C). Our results show that the potential of CBZ in rescuing CSE-treated cells is a proof of concept that warrants further evaluation and standardization. Moreover, we anticipate that further experimentation in the CS–emphysema murine model may provide clearer results on the ability of CBZ to rescue the overall disease pathophysiology. Nonetheless, the data here verify the role of CS-induced autophagy impairment in aggresome formation, as it can be rescued by an autophagy inducer, CBZ.

Figure 2.

CSE induces aggresome formation by interfering with proteostasis and autophagy processes. (A) An equal number of Beas2b cells were transfected for 24 hours with Ub-RFP and autophagy protein microtubule–associated protein 1 light chain-3B (LC3)–green fluorescent protein (GFP) to quantify autophagy-mediated Ub accumulation. Carbamazepine (CBZ; 20 μM) and freshly prepared CSE (10%) treatments were added for the final 6 hours before capturing images. Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Based on plating of an equal number of Beas2b cells (row 1 in A), the percentage of colocalized cells was calculated as displayed in the merged image (row 4 in A). CSE treatment significantly (∼11-fold; P < 0.001) induced Ub accumulation (red) in LC3+ (green; magnified inset provided) autophagy bodies (LC3 and Ub colocalization [yellow] merged images of same cellular field), indicating aggresome formation. Short, 6-hour treatment with CBZ shows a decrease in Ub-RFP puntas (red perinuclear bodies), Ub-LC3+ yellow autophagy bodies (∼1.2-fold; P < 0.01), and increased LC3-GFP (autophagy reporter) expression, suggesting that CSE-induced aggresome formation can be controlled by autophagy induction. (C) Beas2b cells were treated with freshly prepared CSE (5 or 10%), cycloheximide (CHX) (50 μg/ml), and/or CBZ (10 μM) for 6 hours. We observed greater accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in the insoluble protein fraction of CSE-treated Beas2b cells. Moreover, levels of ubiquitinated proteins in the soluble protein fraction were decreased in samples that had increased aggregation in the insoluble fraction, suggesting translocation and aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins as aggresome bodies. The magnitude of protein movement from the soluble fraction to the insoluble aggresomes tended to correlate to the CSE dose. In CSE samples treated with the low-dose autophagy–inducing drug, CBZ (lane 5 versus 6), soluble ubiquitinated and NF-κB protein levels were reduced, although the effect on accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in the insoluble fraction was insignificant with the selected dose (10 μM). Moreover, when protein synthesis was halted by CHX, similar effects were observed, suggesting that CSE induces protein synthesis to override the effect of CHX treatment to exacerbate CSE-induced aggresome formation. β-actin was used as a loading control for soluble fractions. (D) We used proteasome inhibitor (MG-132) treatment as a positive control to induce aggresome formation (ubiquitinated protein aggregation) in Beas2b cells, which were treated overnight with MG-132 (1 μM) and/or CBZ (5, 10, 20 μM). Overnight treatment of MG-132 (1 μM) caused accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in both the soluble and insoluble fractions, as anticipated. Multiple overnight treatment doses of CBZ were tested to investigate their effectiveness in reducing MG-132–induced aggresome bodies (Ub pellet, insoluble fraction) and total NF-κB protein levels. In MG-132–treated cells, even a low dose (10 μM) of CBZ was effective in decreasing NF-κB levels. As anticipated, CBZ (20 μM) was effective in inhibiting MG-132–induced aggresome bodies (Ub pellet, insoluble fraction). β-actin was used as a loading control for soluble fractions. CBZ has the potential to alleviate CSE-induced accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins by modulating autophagy and proteostasis mechanisms. Data are presented as mean (±SEM). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Because CS is also known to inhibit proteasomal activity (14, 22), we used an irreversible proteasome inhibitor (MG-132) known to induce aggresome formation to further verify the potential of autophagy induction (CBZ) in inhibiting aggresome bodies (Figure 2D). As expected, we observed significant accumulation and aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins in both the soluble and insoluble cellular protein fractions of 1 μM MG-132–treated cells (Figure 2D, top and bottom panels). We also observed that CBZ (20 μM) treatment trends toward reducing elevated NF-κB levels and aggresome formation in 1 μM MG-132 treatment (Figure 2D), suggesting the potential of autophagy induction (CBZ) in reducing NF-κB–mediated chronic inflammation induced by aggresome bodies. We anticipate that CBZ-induced autophagy induction is too mild to overcome potency of MG-132–mediated severe proteasomal inhibition. Furthermore, CBZ may also be modulating proteasomal mechanism(s), as suggested by earlier studies (45). Thus, we further investigated if the autophagy-inducing drug, CBZ (20 μM), modulates other protein processing pathways to understand its mechanism of action.

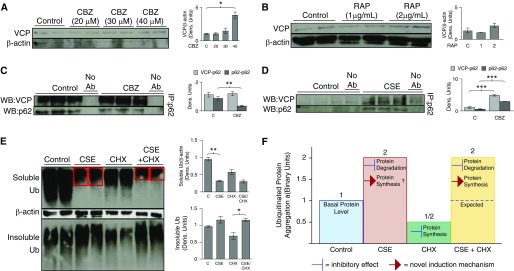

Autophagy Induction Modulates Valosin-Containing Protein Localization to the Aggresomes

We first verified if the CBZ dosage recently reported for autophagy induction (45) was appropriate for our experiments. Hence, we focused on evaluating whether this dose of CBZ modulates ubiquitination and protein aggregation via valosin-containing protein (VCP), as it is known to play a critical role in autophagy-mediated protein degradation (46–49). We observed that neither ubiquitinated nor total VCP protein levels were affected by short-term autophagy induction (CBZ) in the presence or absence of lysosome inhibitor (Figure 3A). Because VCP is known to mediate aggresome formation and autophagy, we anticipated that CBZ may change the localization of VCP to perinuclear spaces (aggresomes) to induce autophagy. Hence, we investigated the relationship between VCP and aggresome formation by fluorescence microscopy, and observed a significant increase in VCP localization to the perinuclear spaces (aggresomes; higher number are VCP+) after autophagy induction (CBZ) (Figure 3B, row 4), suggesting that VCP may be involved in autophagy-mediated aggresome clearance. The lysosome inhibitor does not significantly change this CBZ-induced VCP relocalization (Figure 3B, row 2), ruling out the involvement of autophagolysosomes. We further examined VCP localization by semiquantitative immunoblotting, and found that long-term CBZ treatment (24 h, 40 μM) induces (P < 0.05) VCP expression (Figure 4A), verifying the potential of CBZ to modulate VCP expression and activity, as well as relocalization to aggresome bodies. Moreover, we used rapamycin, another known autophagy inducer, as a positive control to verify the role of VCP in autophagy, and found a slight induction of VCP by rapamycin, as expected (Figure 4B). Our findings are further substantiated by a recent study demonstrating that activation of autophagy by Torin1 controls accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins (11).

Figure 3.

CBZ treatment induces valosin-containing protein (VCP) relocalization and expression to aggresome bodies. (A) Beas2b cells were treated with CBZ (20 μM, 48 h) and/or lysosome inhibitor ([Lys. Inh.] E64 and pepstatin A, 20 μg/ml each, final 6 h). Treatment with lysosome inhibitor in the presence of CBZ did not affect basal ubiquitin or VCP protein levels, suggesting that CBZ does not influence lysosomal degradation machinery to induce autophagy. β-actin was used as a loading control for soluble fractions. (B) Beas2b cells were transfected for 48 hours with VCP-GFP and treated with CBZ (20 μM, 36 h) and/or lysosome inhibitor (E64 and pepstatin A, 20 μg/ml each, final 6 h). CBZ treatment induced VCP-GFP relocalization (magnified inset included) to the perinuclear spaces and slightly modulated VCP-GFP expression, suggesting the involvement of VCP as a mechanism for autophagy induction and aggresome formation. Scale bars, 100 μm for rows 1 and 2 and 20 μm for rows 3 and 4. CBZ induced VCP relocalization to perinuclear spaces (aggresomes bodies), suggesting its participation in CBZ induced autophagy.

Figure 4.

The mechanism for CSE-induced aggresome formation and CBZ-mediated autophagy induction. (A) Beas2B cells were treated with CBZ, a known autophagy inducer, at indicated doses for 24 hours. Cells treated with a high dosage of CBZ (40 μM, lanes 7 and 8) showed significant (P < 0.05) induction of VCP as compared with untreated cells, verifying the ability of CBZ in modulating a VCP autophagy pathway, in addition to VCP relocalization to perinuclear spaces (Figure 3B), suggesting its role in elevating VCP-mediated autophagy to control aggresome bodies. (B) Beas2B cells were treated with indicated doses of another autophagy inducer, rapamycin (RAP) (24 h), as a positive control. As anticipated, autophagy induction by RAP induced VCP expression, suggesting its role in autophagy. (C) Beas2B cells were treated with CBZ for 6 hours, and equal amounts of total proteins were used to immunoprecipitate p62, a known autophagy marker, followed by immunoblotting for VCP and p62. Significant (P < 0.01) inhibition of p62 expression (immunoprecipitation [IP] and Western blot [WB]: p62) in CBZ-treated samples confirmed autophagy induction. Moreover, VCP–p62 protein–protein interaction (IP, p62; WB, VCP) during CBZ treatment remained constant, whereas p62 expression decreased, providing further evidence that CBZ induces VCP relocalization to autophagy bodies. (D) Beas2B cells were similarly treated with CSE for 6 hours, and equal amounts of total proteins were used to immunoprecipitate p62, followed by immunoblotting for VCP and p62. CSE-treated cells displayed a significant (P < 0.0001) increase in p62 expression, indicating CSE-induced aberrant autophagy. CSE treatment also significantly (P < 0.0005) induced VCP–p62 protein–protein interaction, confirming that VCP relocalizes to p62+ aggresome bodies as a cellular response to CSE-induced aberrant autophagy. (E) Beas2B cells were next treated with CHX for 24 hours and/or CSE for the last 6 hours. CSE treatment significantly (P < 0.01) inhibited accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in the soluble fraction, which corresponds to induction of ubiquitinated protein aggregation in the insoluble fraction (bottom panel, lanes 3 and 4). Treatment with a protein synthesis inhibitor, CHX, decreased accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in both the soluble and insoluble fractions. Halting protein synthesis by CHX treatment in the presence of CSE, however, did not inhibit aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins in the insoluble fraction (bottom panel, lanes 7 and 8), suggesting that CSE treatment induces protein synthesis to overcome the inhibitory effect of CHX. β-actin was used as a loading control for soluble fractions for A to E. (F) Statistical analysis of insoluble protein fractions in binary units used aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins in the insoluble protein fractions shown in (E). CSE is known to inhibit protein degradation, but CHX halts protein synthesis. Therefore, cotreatment with CHX should persuade inhibition of CSE-induced ubiquitinated protein aggregation. However, CSE+CHX–cotreated cells show approximately equal amounts of ubiquitinated proteins in the insoluble fraction, similar to cells treated with only CSE. Data suggest that CSE induces protein synthesis to overcome the inhibitory effect of CHX, thus retaining ubiquitinated protein levels in the insoluble fraction. CSE treatment induced protein synthesis and VCP expression/localization to aggravate aggresome formation, whereas CBZ could induce VCP-mediated autophagy for clearance of these aggresome bodies. Data are presented as mean (±SEM). Ab, antibody. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Next, we used immunoprecipitation of sequestosome-1/p62, an aberrant autophagy marker, to evaluate further the mechanism by which CBZ modulates VCP and/or autophagy. A significant (P < 0.01) decrease in p62 expression after CBZ treatment confirms autophagy induction (Figure 4C), as previously demonstrated (11, 30, 50). Furthermore, we observed relatively constant levels of p62–VCP protein–protein interaction during CBZ treatment (Western blot, VCP; immunoprecipitation, p62), whereas p62 levels decreased (Western blot, p62; immunoprecipitation, p62), suggesting a net increase in VCP protein levels or binding (Figure 4C), which corroborates our hypothesis that CBZ induces VCP localization to autophagy bodies (Figure 3B). We similarly evaluated the role of CSE in VCP-mediated autophagy, and observed a very significant (P < 0.0001) increase in accumulation of p62 (Figure 4D), confirming CS-induced aberrant autophagy (Figures 2 and E3B). We also found a significant (P < 0.0005) increase in p62–VCP protein–protein interaction (Figure 4D) in the presence of CSE, verifying that CS induces VCP localization to p62+ aggresome bodies as a response to autophagy impairment. We foresee that these preliminary experiments can serve as a foundation for a potential therapeutic strategy targeting a proposed mechanism to treat COPD–emphysema pathogenesis. In fact, we have previously observed that CS modulates early steps of protein processing to induce aggresome formation, which warrants further investigation (14).

CSE Modulates Protein Turnover Rates to Induce Aggresome Formation

Our current data suggest that CS mediates aggresome formation by impairing autophagy (discussed previously here) while inhibiting the proteasome (14, 22). We further investigated if CS also modulates protein synthesis, based on our previous preliminary findings suggesting its potential involvement (14). We found that treatment with protein synthesis inhibitor, CHX (24 h), significantly reduces aggresome formation (Ub pellet) as compared with the control cells (Figure 4E), verifying that inhibition of protein synthesis can decrease aggresome formation. On the other hand, short, 6-hour CSE treatment greatly increased aggresome formation (Figure 4E, bottom panel, insoluble fraction) as discussed previously here (14, 22). We also confirm here the transition of ubiquitinated proteins between the soluble and insoluble fractions (aggresome formation; Figure 4E, top and bottom panels) with CSE and/or CHX treatment(s). Most notably, we observe similar levels of ubiquitinated protein aggregation (pellet) in both CSE + CHX– and CSE-only–treated cells (Figure 4E, bottom panel), demonstrating that inhibition of protein synthesis by CHX was overridden or ineffective in the presence of CSE. Furthermore, the decreased levels of ubiquitinated proteins in the soluble fraction of CSE + CHX–treated cells (Figure 4E, top panel, red boxes) demonstrates that CSE starts promoting ubiquitination and aggregation of proteins (insoluble fraction; Figure 4E, bottom panel) as they are being synthesized. Theoretically, inhibition of protein synthesis by CHX and protein degradation by CSE should offset each other, resulting in aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins approximately equal to the basal levels (Figure 4F, expected value of CSE + CHX). This increase in aggresome formation over the expected value verifies that CSE treatment induces protein synthesis (Figures 4E and 4F). Therefore, our data suggest that CS-induced protein synthesis exacerbates aggresome formation in COPD–emphysema. However, in contrast to freshly prepared CSE treatments, commercial (C)-CSE procured from commercial vendors could not override protein synthesis inhibition (CHX; Figure E1C), verifying its lower potency as discussed previously here (Figure E1).

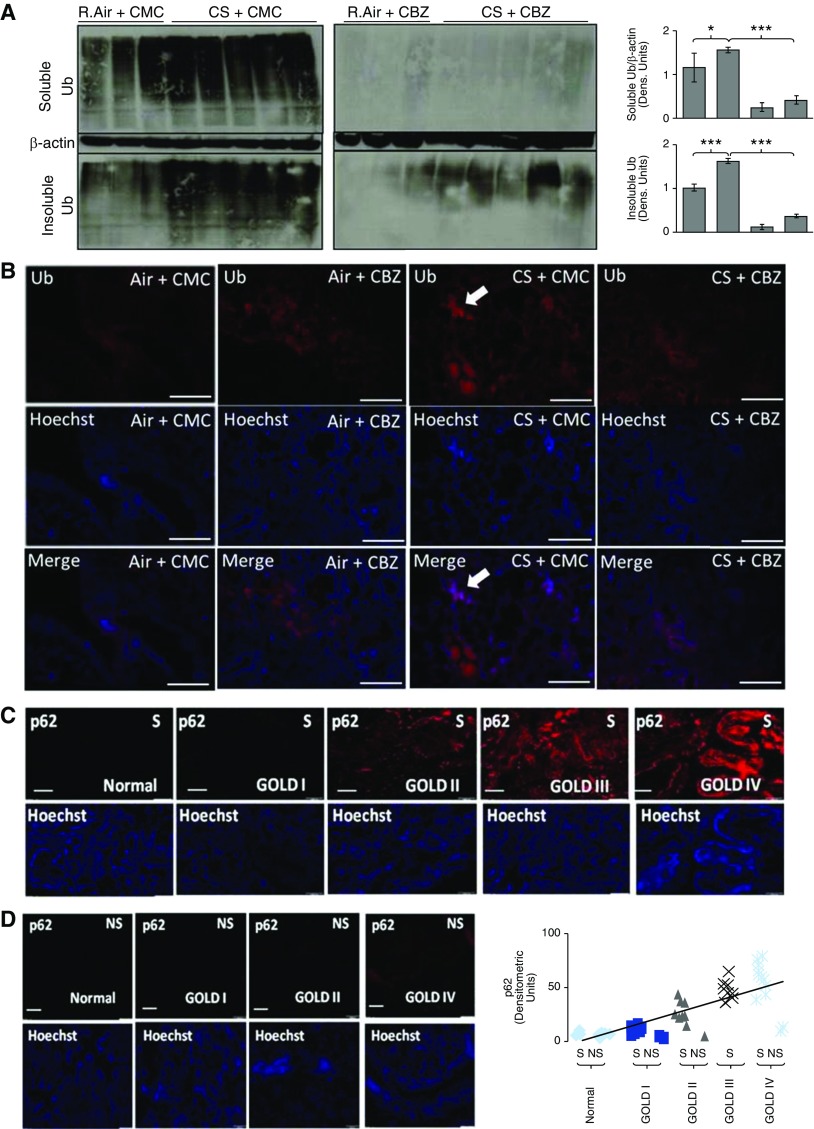

CS Exposure Induces Aggresome Formation in COPD–Emphysema

To confirm our in vitro findings, we used chronic CS–exposed (28 wk) C57BL/6 mice as an experimental model to evaluate CS-induced aggresome formation and aberrant autophagy in COPD–emphysema. We observed a significant increase in accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in both soluble (P < 0.01; Figure 5A, top left panel) and insoluble (aggresome formation, P < 0.0005; Figure 5A, bottom left panel) fractions of CS-exposed murine lungs as compared with room air lungs (Figure 5A, left panel), verifying chronic CS–induced aggresome formation (Figures 1 and 2C). Although we initially observed some CS-induced accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins, even in the soluble fractions (Figure 5A, top left panel) of lung protein extracts, resonication of these extracts moved aggregated proteins from the soluble (Figure E2A; equal levels in room air and chronic CS) to the insoluble fraction as a secondary pellet (visible), suggesting chronic CS induces severe protein aggregation that is difficult to separate using the standard method. Our preliminary acute CS exposure experiment also substantiates that CS induces aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins only in the insoluble fraction (Figure E2B). Next, we sought further confirmation of chronic CS–induced aggresome formation by immunofluorescence microscopy. We observed a significant increase in perinuclear Ub accumulation (aggresomes) in chronic CS–exposed murine lungs (Figure 5B, column 3) as compared with room air–treated controls (Figure 5B, column 1), confirming that chronic CS induces aggresome formation (Figures 1, 2C, and 5A). Moreover, CBZ treatment significantly decreased Ub aggregation (aggresomes) in chronic CS–exposed lungs (Figure 5A, right bottom panel, and Figure 5B, column 4), verifying the therapeutic potential of autophagy induction in controlling aggresome formation. Lung sections were further immunostained for NF-κB and p62 to investigate changes in inflammation and autophagy activity after chronic CS exposure. In accordance with our in vitro findings (Figures 2 and 4D), we observed that chronic CS induces NF-κB and p62 expression, corresponding to increased inflammation and aberrant autophagy, respectively (Figure E3). We found that subcutaneous CBZ treatment of chronic CS–exposed mice can control both inflammation (NF-κB) and aberrant autophagy (p62) in the lungs, suggesting that autophagy induction can control CS-induced COPD–emphysema (Figure E3). Moreover, human lung tissue sections from subjects with COPD–emphysema (GOLD I–IV) and nonemphysema control subjects (GOLD 0) (smokers versus nonsmokers) were used to quantify changes in aberrant autophagy marker, p62, by immunofluorescence microscopy. We found significant p62 accumulation with increasing severity of COPD–emphysema in smokers as compared with nonemphysematous smokers and nonsmokers (Figures 5C and 5D), verifying autophagy impairment. Several other previous studies have shown that CS exposure induces p62 protein levels and accumulation (11, 51, 52) in various models, although this is the first report verifying this in human lungs. Moreover, decreased autophagy activity (p62 accumulation) in severe COPD–emphysema correlates to ubiquitinated protein accumulation (aggresomes) (14, 15), verifying the mechanism and pathogenic role of aggresome bodies in COPD–emphysema progression.

Figure 5.

Chronic CS–induced aggresome bodies and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)–emphysema can be controlled by autophagy induction. (A) Total protein extracts from room air (R.Air)– and chronic CS–exposed C57BL/6 mouse lungs were sonicated and immunoblotted for Ub and β-actin. Chronic CS–exposed mice showed a significant (P < 0.01, soluble; P < 0.0005, insoluble) increase in aggresome bodies (ubiquitinated proteins), especially in the insoluble fractions, demonstrating CS-induced aggresome formation in murine COPD–emphysema lungs (left panel). Moreover, in CBZ-treated mice (right panel), CS-induced accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins (soluble/insoluble protein fractions) is significantly (P < 0.0001, soluble; P < 0.0001, insoluble) inhibited compared with levels seen in carrier, carboxymethylcellulose (CMC)-treated room air– and chronic CS–exposed mice, showing the potential of autophagy induction in controlling CS-induced aggresome bodies. β-actin was used as a loading control for soluble fractions. (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy of longitudinal lung tissue sections from chronic CS–exposed mice shows a significant accumulation of ubiquitinated protein (red; top panel), confirming aggresome formation (top row, third column, white arrow). In addition, CBZ inhibited CS-induced aggresome bodies (top row, fourth column). The middle row uses nuclear staining (Hoechst, blue) to show uniform lung tissue sections. Merged images of the same tissue section field are provided (bottom row) to indicate CS-induced perinuclear ubiquitin accumulation (white arrow). Scale bars, 20 μm. (C and D) Paraffin-embedded longitudinal human lung tissue sections from nonsmokers (NS) and smokers (S) classified as GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) I–IV emphysema (n = 40[S] + 5[NS] = 45) and GOLD 0 nonemphysema control (n = 5[S] + 10[NS] = 15) were immunostained for aberrant autophagy marker p62. Lung tissue sections from smokers with COPD exhibited significant p62 accumulation as lung function declined in subjects with severe emphysema–COPD (S, GOLD III–IV versus S and NS, GOLD 0–I), demonstrating increase in CS-induced autophagy impairment with COPD–emphysema progression. The bottom panel uses nuclear staining (Hoechst, blue) showing uniform lung tissue sections. Chronic CS–induced aggresome formation and aberrant autophagy in COPD–emphysema can be controlled by autophagy induction. Scale bars, 50 μM. Data are presented as mean (±SEM). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Inhibiting Chronic CS–Induced Aggresomes Controls COPD–Emphysema

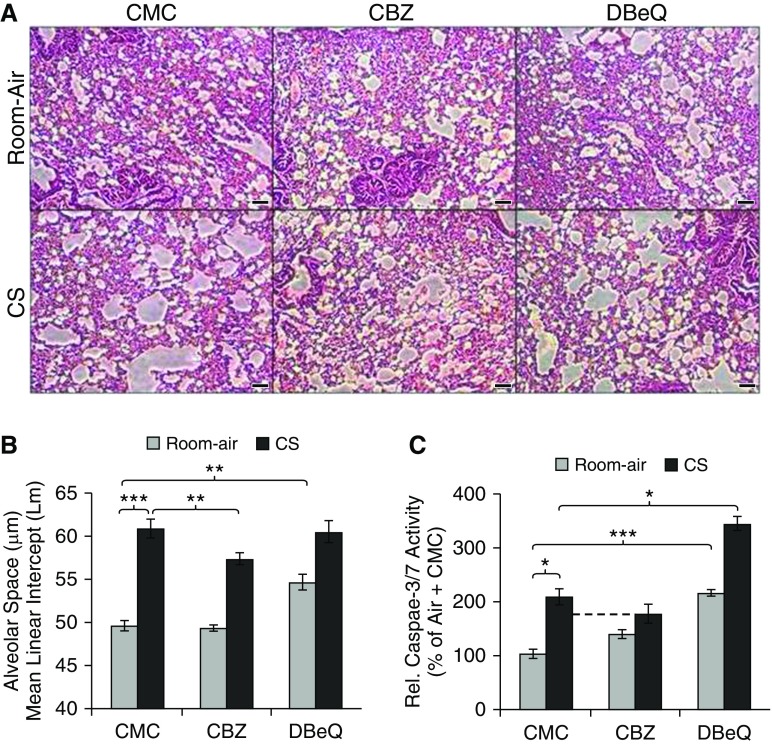

To verify the role of CS-induced aggresome bodies in COPD–emphysema, we conducted morphometric analysis of lung sections from room air– and chronic CS–exposed mice (Figures 6A and 6B) to quantify changes in alveolar spaces (mean linear intercept; diameter). We observed a significant (P < 0.001) increase in alveolar spaces of chronic CS–exposed mice (Figure 6A, bottom left panel, and Figure 6B), which corresponds to elevated Ub accumulation (Figure 5B), suggesting chronic CS–induced aggresome formation as a potential mechanism for alveolar space enlargement and COPD–emphysema pathogenesis. We subsequently treated chronic CS–exposed mice with CBZ to investigate the potential of autophagy induction in controlling aggresome formation and COPD–emphysema pathogenesis. We found that CBZ treatment significantly (P < 0.01) reduced CS-induced alveolar space enlargement (Figure 6A, bottom middle panel), suggesting that inhibition of aggresome bodies by autophagy induction can inhibit or revert CS-induced COPD–emphysema. In addition, chronic CS exposure is known to induce apoptosis as a mechanism to destroy alveoli in emphysema (11, 15, 52, 53). Hence, we examined if CBZ can control chronic CS–induced apoptosis by quantifying caspase-3/7 activity in murine lung extracts (Figure 6C). We observed a significant (P < 0.05) increase in caspase-3/7 activity in chronic CS–exposed murine lungs that can be inhibited by CBZ subcutaneous treatment (Figure 6C). Furthermore, we treated air- and chronic CS–exposed mice with autophagy inhibitor, N2,N4-dibenzylquinazoline-2,4-diamine (DBeQ), as a negative control in this experiment (Figure 6). Autophagy inhibition by DBeQ significantly (P < 0.01) induced alveolar space enlargement in room air–exposed mice (Figure 6A, top right panel, and Figure 6B), confirming that autophagy impairment can contribute to emphysema pathogenesis even in the absence of CS. Contrary to our expectation, the selected DBeQ dose did not synergistically induce CS-mediated alveolar space enlargement (Figure 6B), which suggests that CS impairs autophagy to a level that cannot be further inhibited by DBeQ (Figure 6B). Moreover, autophagy inhibition (DBeQ) significantly induced apoptosis in both room air– (P < 0.05) and chronic CS–exposed (P < 0.0005) murine lungs (Figure 6C), verifying that autophagy impairment can exacerbate COPD–emphysema progression by inducing apoptosis. We also observed a decrease in apoptotic activity in chronic CS–exposed mice treated with an autophagy inducer (CBZ; Figure 6C), substantiating our hypothesis that CS-mediated autophagy impairment induces pathogenic aggresome bodies (Figure 5B) and apoptosis (Figure 6C), resulting in emphysema (Figures 6A, 6B, and 7).

Figure 6.

CBZ controls CS-induced chronic emphysema in a murine model. (A and B) Chronic CS– or room air–exposed C57BL/6 (n = 3–5, 1.5-mo-old + 28-wk air/CS exposure) were used as a COPD–emphysema murine model to standardize and evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of CBZ in controlling autophagy and resulting emphysema. Control groups were subcutaneously injected with 0.5% CMC as the drug carrier, whereas the two other groups were subcutaneously injected with autophagy inducer CBZ (subcutaneous 20 mg/kg body weight/d for the last 10 d = 200 mg/kg body weight) and inhibitor N2,N4-dibenzylquinazoline-2,4-diamine (DBeQ; subcutaneous 5 mg/kg body weight/d for the last 10 d = 50 mg/kg body weight), the latter acting as a negative control. The longitudinal lung tissue sections were fixed in neutral buffer formalin (10%), stained (hematoxylin and eosin), and analyzed for changes in alveolar spaces (4 × 3 = 12 section measurements from n = 3–5 replicates) by microscopy. Autophagy induction (CBZ) significantly (P < 0.01) inhibited chronic CS–induced alveolar space enlargement (mean linear intercept [Lm]), whereas autophagy inhibition (DBeQ, P < 0.01) induced alveolar space enlargement similar to the CS exposure treatment groups, verifying the role of autophagy impairment in alveolar wall destruction and emphysema pathogenesis. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Quantification of caspase-3/7 activity in murine lung tissue extracts shows that autophagy induction by CBZ treatment decreases chronic CS–induced apoptosis. In addition, autophagy inhibition by DBeQ significantly increased caspase-3/7 activity (air, P < 0.0005; CS, P < 0.05) in murine lungs. Autophagy induction (CBZ) controls CS-induced chronic emphysema, whereas autophagy inhibition (DBeQ) induced apoptosis, which can exacerbate emphysema pathogenesis. Data are presented as mean (±SEM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

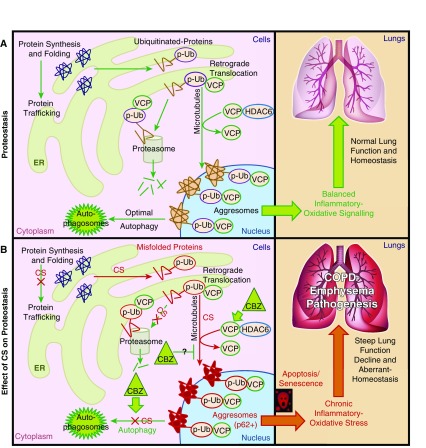

Figure 7.

Schematic showing cellular compartmentalization of CS-induced aggresome formation mechanisms in COPD–emphysema. (A) Functional cellular compartments showing the specific steps of homeostatic protein processing mechanism (proteostasis). The optimal autophagy and proteasomal degradation mechanisms can clear off aggresome bodies in a healthy cell, maintaining balanced inflammatory oxidative responses for normal lung function and homeostasis. (B) CS exposure induced protein synthesis, misfolding, and polyubiquitination (p-Ub), initiating microtubule-mediated translocation of ubiquitinated proteins to perinuclear spaces (aggresomes). Histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) and VCP facilitated this translocation and aggresome formation. The CS impaired autophagy to inhibit degradation of aggresome bodies, inducing chronic inflammatory apoptotic responses, leading to disordered alveolarization, steep lung function decline, and severe COPD–emphysema pathogenesis. Autophagy induction by CBZ induced VCP translocation and expression in p62+ aggresome bodies to assist with autophagy-mediated protein degradation, potentially by inducing its segregase/unfoldase activity to process and present aggregated proteins to autophagosomes. CS induced pathologic p62+ aggresome bodies by inducing protein synthesis, misfolding, ubiquitination, translocation, and aggregation, while restraining autophagy that activates chronic inflammatory oxidative–apoptotic responses and senescence to accelerate COPD–emphysema pathogenesis. ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

Discussion

First- and secondhand CS and aging are known to be the leading causes of COPD–emphysema pathogenesis (4, 5, 11). Recent studies have identified the role of aging in inhibiting proteasome-mediated degradation that induces perinuclear accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins (12–14) as aggresome bodies in neurological disorders (23–27). Therefore, we anticipated that CS-mediated proteasomal inhibition may similarly cause ubiquitinated protein aggregation as aggresome bodies in COPD–emphysema. Although CS has recently been shown to directly inhibit proteasomal activity in murine lungs (14, 21, 22), subjects with COPD have increased proteasomal activity in the diaphragm (53, 54). Nonetheless, our data on accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins support the former. We sought to verify further in this study if CS induces Ub protein accumulation in perinuclear spaces as aggresome bodies. We not only determined a dose-dependent spectrum of CSE-induced ubiquitinated protein aggregation (Figure 1A), but also identified, for the first time, the translocation of ubiquitinated proteins from soluble to insoluble fractions, clearly demonstrating CSE-induced aggresome formation (Figures 1A and 1C) at both high and low doses. We further investigated the cytoprotective translocation (23) of these Ub aggregates by microscopy (Figure 1B) to verify CS-induced aggresome formation. In the presence of CS/CSE, the cell sequesters Ub aggregates to the insoluble fraction for subsequent degradation by the autophagy machinery (Figures 1, 2C, 4D, 4E, and B5B), although a significant increase in aggresome bodies suggests that this process is compromised by CS exposure. Hence, we next examined why intracellular protective mechanisms, such as autophagy, cannot clear off CS-induced aggresome bodies contrary to expectation (23, 55–58). In fact, we found that autophagy induction by CBZ not only depletes these aggresome bodies (Figures 2A and 5B), but can also inhibit CS-induced inflammatory response (NF-κB; Figure 2C), apoptosis (Figure 6C), and emphysema pathogenesis (Figures 6A and 6B). Our study uniquely used Ub and p62/sequestosome-1 accumulation as a marker to investigate autophagy activity, which provides clear insight into the status of autophagy. We found that CS not only induces p62 accumulation (Figures 4D and 5C; Figure E3), a known marker for defective autophagy (11, 30, 59–61), but also accumulates ubiquitinated proteins as aggresome bodies, verifying autophagy impairment (Figures 1, 2, 4E, 5A, and 5B). We chose to use p62 as a marker for autophagy impairment rather than LC3 I/II to have consistent and clear analysis in both Western blots and microscopy, as p62 antibody does not lend itself to a dual-state marker such as LC3, allowing us specificity for microscopy studies. We also found that induction of autophagy by CBZ can control CSE- (Figures 2A, 2C, 5A, and 5B) or MG-132 (proteasome inhibitor; Figure 2D)–mediated aggresome formation (Figures 2 and 5B), further substantiating our conclusion that CS exposure induces aberrant autophagy.

Next, we investigated the mechanism of action by which CBZ alleviates aggresome formation by examining the expression, localization, and autophagy interaction of VCP (Figures 3 and 4A), a key mediator of both proteasomal and aggresomal protein processing pathways (47, 48, 59, 62–66). VCP is not only involved in translocating proteins to microtubule organizing centers (aggresomes) (23, 67), but is also responsible for segregation and unfolding of ubiquitinated proteins from aggresome bodies for presentation to the protein degradation machinery (49, 64). Consequently, we evaluated the association of VCP with p62, a critical component and marker of aggresome autophagy bodies (30, 68–72), to investigate the role of VCP in mediating aggresome formation and autophagy. We found that the ratio of VCP to p62 protein levels is increased, whereas their protein–protein interaction remains constant during autophagy induction by CBZ (Figure 4C), which not only confirms VCP localization to the aggresome/autophagy bodies, but also suggests its participation in CBZ-mediated autophagy induction. In addition, we observed that CSE treatment induces VCP–p62 protein–protein interaction (Figure 4D), verifying the localization of VCP to aggresome/autophagy bodies as a response to CS-induced aberrant autophagy. In fact, CS-induced colocalization of ubiquitinated proteins and VCP to aggresome bodies (Figures 3 and 4) suggest that, although VCP is present at elevated levels, its functional (segregase/unfoldase) activity may be inhibited by CS as a common mechanism for proteostasis and autophagy impairment. These results provide a proof of concept of the potential mechanism involving autophagy induction and VCP, which warrants further investigation in an in vivo COPD–emphysema murine model.

Furthermore, we found that CSE can override inhibition of protein synthesis (CHX) and contribute to protein overload, while inducing ubiquitination and aggregation of these newly synthesized proteins (Figure 4E), suggesting that CS induces misfolding of proteins during synthesis. By first halting protein synthesis with CHX, we uniquely designed our experiment to isolate the effect of CSE on the proteins as they are synthesized, and demonstrate a novel mechanism by which CS induces protein synthesis to promote aggresome formation. This is further supported by our previous studies using another protein synthesis inhibitor, salubrinal, to control Ub accumulation (14, 73). Salubrinal inhibits protein synthesis by preventing dephosphorylation to eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF) 2α to stabilize phospho-eIF2α (73, 74), which inhibits initiation of translation during protein synthesis. Furthermore, a previous study compared the relative effects of CHX and CSE treatments on protein synthesis, but lacked cotreatment (CSE + CHX) and quantification of protein aggregation (aggresomes) (33). Hence, it only demonstrated that CS exposure decreases total cellular protein levels, which further supports our conclusion on CS-induced translocation of ubiquitinated proteins from the soluble fraction to insoluble aggresome bodies. Therefore, we propose that CS induces protein synthesis and translocation activities, while inhibiting its degradation via proteasome and autophagy mechanisms. Further confirmation of these results by radiolabeled pulse analysis experiments as a part of our ongoing studies would provide insights into mechanisms by which CSE effects protein turnover.

This modulation of protein processing is further supported by previous studies showing accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in acute CS exposure murine model and human emphysematous lungs (14, 22). We demonstrate here, for the first time, that chronic CS induces translocation of aggregated proteins (insoluble fraction) to perinuclear spaces (aggresomes). Furthermore, homeostatic mechanisms, such as autophagy, are compromised by chronic CS exposure (Figures 4D and 5C; Figure E3B), inducing aggresome bodies (Figures 1, 2, 4E, 5A, and 5B; Figures E1A, E1B, and E2B) and COPD–emphysema pathology (Figures 6A and 6B). In addition to confirming the role of acute/chronic CS in aggresome formation, we verified its association with COPD–emphysema pathogenesis. Moreover, our primary observation about accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in COPD–emphysema (14) was recently verified by two other groups (11, 22). Here, we also demonstrate CS-induced aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins in the insoluble fraction (Figures 1, 2C, 4E, 5A, and 5B; Figures E1A, E1B, and E2B), in contrast to other studies where insoluble fraction was not even studied (11, 22). To further understand the mechanism of aggresome formation, we evaluated changes in aberrant autophagy marker, p62, in human COPD–emphysema lung tissues. We observed significant p62 accumulation with increasing severity of emphysema in smokers with COPD as compared with control subjects without emphysema (smokers and nonsmokers; Figures 5C and 5D), confirming the role of CS-induced autophagy impairment in COPD–emphysema progression. A previous preliminary study substantiates our conclusions about insufficient autophagy in subjects with CS–COPD, although that study had a smaller sample size (11). In this study, we focused on verifying that CS exposure induces p62 protein levels and accumulation (impaired autophagy marker) in COPD–emphysema murine and human lungs as an effort to establish the potential role of impaired autophagy in COPD–emphysema. We further verified this concept by using autophagy induction by CBZ as an experimental tool to inhibit CS-induced aggresome pathophysiology and currently verifying mechanism(s) by which it rescues CS-impaired autophagy (VCP/p62 levels and location). Moreover, using a murine model, we found that chronic CS induces alveolar space enlargement (Figures 6A and 6B) and apoptosis (Figure 6C) that can be controlled by depleting aggresome bodies (Figures 5A and 5B) via autophagy induction (CBZ). We further verified the role of autophagy impairment in COPD–emphysema pathogenesis with autophagy inhibitor, DBeQ (75) (Figure 6), and found that our selected dose of DBeQ induces both significant alveolar space enlargement (Figures 6A and 6B) and apoptosis in room air treatment groups (Figure 6C) in a manner similar to chronic CS. This supports our finding that autophagy induction can control CS-induced emphysema in subjects with COPD. The sequential investigation of the role of autophagy in CS-induced COPD–emphysema in this study clarifies that CS in fact impairs autophagy, in contrast to the findings of a previous report (44, 76). Moreover, a recent study demonstrated the efficacy of CBZ in controlling hepatic fibrosis caused by ATZ mutation (45), which is also known to develop emphysema in a small population (5%) of subjects with COPD, suggesting its potential to also control ATZ-related emphysema. In addition to our experiments using the Beas2B cell line, further investigation in primary human bronchial epithelial cells from subjects with COPD–emphysema could potentially reveal further mechanistic information that would help advance the knowledge of COPD–emphysema pathogenesis.

In conclusion, we report that CS induces protein synthesis and translocation, while inhibiting its degradation (autophagy and proteasome) to initiate aggresome formation that mediates COPD–emphysema pathogenesis (Figure 7). We also found that CS induces protein misfolding and aggregation during synthesis, potentially by modulating phospho-eIF2α (13, 14, 33). Moreover, because CS induces perinuclear accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins (aggresomes), we anticipated that it inhibits a common intermediate of proteasomal and autophagy degradation mechanisms. Hence, we looked into VCP, which mediates protein ubiquitination and translocation, followed by its unfolding for presentation to proteasomal and autophagy degradation machinery. We found that CS modulates VCP expression and localization to perinuclear aggresomes, but is incapable of clearing Ub aggregates. Hence, we anticipate that its segregase/unfoldase activity may be compromised as a common mechanism for defective autophagy and proteasomal activities. Furthermore, a known autophagy-inducing drug (CBZ) that induces VCP localization, expression, and activity can deplete aggresome bodies. Future investigation on the role of CBZ in reducing aggresome formation would greatly benefit from RNA interference knockdown of vital autophagy genes to identify specific mechanism(s) of action for CBZ. We anticipate that selective induction of VCP segregase/unfoldase activity will be relatively more effective as compared with CBZ in clearing aggresome bodies and associated COPD–emphysema, as it can unfold and present severely aggregated proteins to autophagy and proteasomal degradation machinery, which warrants further investigation. However, the potential application of CBZ in modulating aggresome formation through both autophagy and proteasomal pathways encourages its further evaluation as a potential therapeutic for controlling COPD–emphysema pathogenesis. Hence, further in-depth analysis of mechanisms by which CBZ modulates proteasomal pathways in addition to autophagy will substantiate its potential application in alleviating COPD–emphysema pathophysiology. In the current study, we simply used CBZ as an experimental tool (to induce autophagy) to verify our observation that CS, a major risk factor for COPD–emphysema and a leading cause of death globally, impairs autophagy. In summary, our studies have identified the specific effect of CS on proteasomal and autophagy pathways, which crucially influence the pathogenesis of COPD–emphysema. We have taken steps toward a more complete understanding of this mechanism, with a hope that our findings will help identify a treatment that can alleviate COPD–emphysema and its symptoms. We propose autophagy or VCP seggregase/unfoldase induction as a potential therapeutic strategy to control aggresome formation and resulting COPD–emphysema pathophysiology, as it can control both autophagy and proteasome-mediated ubiquitinated protein aggregation, which warrants further investigation.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Flight Attendant Medical Research Institutes Young Clinical Scientist Award (FAMRI-YCSA) to N.V. N.V. was also supported by NIH grants (U54CA141868 and R01HL59410-04) during this period.

Author Contributions: I.T., C.J., I.N., T.M., and D.T. performed the experiments; I.T., C.J., I.N., T.M., and N.V. analyzed the data; I.T., C.J., and N.V. wrote the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0107OC on December 9, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a growing but neglected global epidemic. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshida T, Tuder RM. Pathobiology of cigarette smoke–induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1047–1082. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00048.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, Mathers CD, Hansell AL, Held LS, Schmid V, Buist S. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:397–412. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00025805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito K, Barnes PJ. COPD as a disease of accelerated lung aging. Chest. 2009;135:173–180. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahman I, Adcock IM. Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:219–242. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00053805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houghton AM, Quintero PA, Perkins DL, Kobayashi DK, Kelley DG, Marconcini LA, Mecham RP, Senior RM, Shapiro SD. Elastin fragments drive disease progression in a murine model of emphysema. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:753–759. doi: 10.1172/JCI25617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leberl M, Kratzer A, Taraseviciene-Stewart L. Tobacco smoke induced COPD/emphysema in the animal model: are we all on the same page? Front Physiol. 2013;4:91. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldklang MP, Marks SM, D’Armiento JM. Second hand smoke and COPD: lessons from animal studies. Front Physiol. 2013;4:30. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slowik N, Ma S, He J, Lin YY, Soldin OP, Robbins RA, Turino GM. The effect of secondhand smoke exposure on markers of elastin degradation. Chest. 2011;140:946–953. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, Peruga A, Pruss-Ustun A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet. 2011;377:139–146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii S, Hara H, Araya J, Takasaka N, Kojima J, Ito S, Minagawa S, Yumino Y, Ishikawa T, Numata T, et al. Insufficient autophagy promotes bronchial epithelial cell senescence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. OncoImmunology. 2012;1:630–641. doi: 10.4161/onci.20297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodas M, Min T, Vij N. Early-age-related changes in proteostasis augment immunopathogenesis of sepsis and acute lung injury. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Min T, Bodas M, Mazur S, Vij N. Critical role of proteostasis-imbalance in pathogenesis of COPD and severe emphysema. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89:577–593. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0732-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodas M, Tran I, Vij N. Therapeutic strategies to correct proteostasis-imbalance in chronic obstructive lung diseases. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:807–814. doi: 10.2174/156652412801318809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirkham PA, Barnes PJ. Oxidative stress in COPD. Chest. 2013;144:266–273. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franz A, Ackermann L, Hoppe T. Create and preserve: proteostasis in development and aging is governed by Cdc48/p97/VCP. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben-Zvi A, Miller EA, Morimoto RI. Collapse of proteostasis represents an early molecular event in Caenorhabditis elegans aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14914–14919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902882106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cannizzo ES, Clement CC, Morozova K, Valdor R, Kaushik S, Almeida LN, Follo C, Sahu R, Cuervo AM, Macian F, Santambrogio L. Age-related oxidative stress compromises endosomal proteostasis. Cell Rep. 2012;2:136–149. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malhotra D, Thimmulappa R, Vij N, Navas-Acien A, Sussan T, Merali S, Zhang L, Kelsen SG, Myers A, Wise R, et al. Heightened endoplasmic reticulum stress in the lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the role of Nrf2-regulated proteasomal activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:1196–1207. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0324OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 22.van Rijt SH, Keller IE, John G, Kohse K, Yildirim AO, Eickelberg O, Meiners S. Acute cigarette smoke exposure impairs proteasome function in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303:L814–L823. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00128.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston JA, Ward CL, Kopito RR. Aggresomes: a cellular response to misfolded proteins. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1883–1898. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kopito RR. Aggresomes, inclusion bodies and protein aggregation. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:524–530. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takalo M, Salminen A, Soininen H, Hiltunen M, Haapasalo A. Protein aggregation and degradation mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2013;2:1–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong R, Siegel D, Ross D. The activation sequence of cellular protein handling systems after proteasomal inhibition in dopaminergic cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2013;204:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janen SB, Chaachouay H, Richter-Landsberg C. Autophagy is activated by proteasomal inhibition and involved in aggresome clearance in cultured astrocytes. Glia. 2010;58:1766–1774. doi: 10.1002/glia.21047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanida I, Minematsu-Ikeguchi N, Ueno T, Kominami E. Lysosomal turnover, but not a cellular level, of endogenous LC3 is a marker for autophagy. Autophagy. 2005;1:84–91. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.2.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H, Overvatn A, Bjorkoy G, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryter SW, Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Choi AM. Autophagy in pulmonary diseases. Annu Rev Physiol. 2012;74:377–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryter SW, Lam HC, Chen ZH, Choi AM. Deadly triplex: smoke, autophagy and apoptosis. Autophagy. 2011;7:436–437. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.4.14501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somborac-Bacura A, van der Toorn M, Franciosi L, Slebos DJ, Zanic-Grubisic T, Bischoff R, van Oosterhout AJ. Cigarette smoke induces endoplasmic reticulum stress response and proteasomal dysfunction in human alveolar epithelial cells. Exp Physiol. 2013;98:316–325. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.067249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Besaratinia A, Pfeifer GP. Second-hand smoke and human lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:657–666. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70172-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su Y, Han W, Giraldo C, De Li Y, Block ER. Effect of cigarette smoke extract on nitric oxide synthase in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:819–825. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.5.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kode A, Yang SR, Rahman I. Differential effects of cigarette smoke on oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokine release in primary human airway epithelial cells and in a variety of transformed alveolar epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2006;7:132. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Low B, Liang M, Fu J. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates sidestream cigarette smoke–induced endothelial permeability. J Pharmacol Sci. 2007;104:225–231. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0070385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sopori M. Effects of cigarette smoke on the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:372–377. doi: 10.1038/nri803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bodas M, Min T, Mazur S, Vij N. Critical modifier role of membrane–cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator–dependent ceramide signaling in lung injury and emphysema. J Immunol. 2011;186:602–613. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valle CW, Min T, Bodas M, Mazur S, Begum S, Tang D, Vij N. Critical role of VCP/p97 in the pathogenesis and progression of non–small cell lung carcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vij N, Roberts L, Joyce S, Chakravarti S. Lumican suppresses cell proliferation and aids Fas-Fas ligand mediated apoptosis: implications in the cornea. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:957–971. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brodie MJ, Richens A, Yuen AW. Double-blind comparison of lamotrigine and carbamazepine in newly diagnosed epilepsy: UK Lamotrigine/Carbamazepine Monotherapy Trial Group. Lancet. 1995;345:476–479. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Denicoff KD, Smith-Jackson EE, Disney ER, Ali SO, Leverich GS, Post RM. Comparative prophylactic efficacy of lithium, carbamazepine, and the combination in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:470–478. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi J, Yin N, Xuan LL, Yao CS, Meng AM, Hou Q. Vam3, a derivative of resveratrol, attenuates cigarette smoke–induced autophagy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33:888–896. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hidvegi T, Ewing M, Hale P, Dippold C, Beckett C, Kemp C, Maurice N, Mukherjee A, Goldbach C, Watkins S, et al. An autophagy-enhancing drug promotes degradation of mutant alpha1-antitrypsin Z and reduces hepatic fibrosis. Science. 2010;329:229–232. doi: 10.1126/science.1190354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dai RM, Li CC. Valosin-containing protein is a multi-ubiquitin chain–targeting factor required in ubiquitin-proteasome degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:740–744. doi: 10.1038/35087056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wojcik C, Yano M, DeMartino GN. RNA interference of valosin-containing protein (VCP/p97) reveals multiple cellular roles linked to ubiquitin/proteasome–dependent proteolysis. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:281–292. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song C, Xiao Z, Nagashima K, Li CC, Lockett SJ, Dai RM, Cho EH, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Colburn NH, et al. The heavy metal cadmium induces valosin-containing protein (VCP)–mediated aggresome formation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;228:351–363. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobayashi T, Manno A, Kakizuka A. Involvement of valosin-containing protein (VCP)/p97 in the formation and clearance of abnormal protein aggregates. Genes Cells. 2007;12:889–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bjorkoy G, Lamark T, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1: a missing link between protein aggregates and the autophagy machinery. Autophagy. 2006;2:138–139. doi: 10.4161/auto.2.2.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bodas M, Min T, Vij N. Critical role of CFTR-dependent lipid rafts in cigarette smoke–induced lung epithelial injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L811–L820. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00408.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monick MM, Powers LS, Walters K, Lovan N, Zhang M, Gerke A, Hansdottir S, Hunninghake GW. Identification of an autophagy defect in smokers’ alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 2010;185:5425–5435. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ottenheijm CA, Heunks LM, Sieck GC, Zhan WZ, Jansen SM, Degens H, de Boo T, Dekhuijzen PN. Diaphragm dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:200–205. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-262OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ottenheijm CA, Heunks LM, Li YP, Jin B, Minnaard R, van Hees HW, Dekhuijzen PN. Activation of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway in the diaphragm in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:997–1002. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-721OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olzmann JA, Chin LS. Parkin-mediated K63-linked polyubiquitination: a signal for targeting misfolded proteins to the aggresome–autophagy pathway. Autophagy. 2008;4:85–87. doi: 10.4161/auto.5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garcia-Mata R, Gao YS, Sztul E. Hassles with taking out the garbage: aggravating aggresomes. Traffic. 2002;3:388–396. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ryter SW, Choi AM. Autophagy: an integral component of the mammalian stress response. J Biochem Pharmacol Res. 2013;1:176–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakahira K, Choi AM. Autophagy: a potential therapeutic target in lung diseases. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305:L93–L107. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00072.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ju JS, Miller SE, Hanson PI, Weihl CC. Impaired protein aggregate handling and clearance underlie the pathogenesis of p97/VCP-associated disease. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30289–30299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805517200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richter-Landsberg C, Leyk J. Inclusion body formation, macroautophagy, and the role of HDAC6 in neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:793–807. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bartlett BJ, Isakson P, Lewerenz J, Sanchez H, Kotzebue RW, Cumming RC, Harris GL, Nezis IP, Schubert DR, Simonsen A, et al. p62, Ref(2)P and ubiquitinated proteins are conserved markers of neuronal aging, aggregate formation and progressive autophagic defects. Autophagy. 2011;7:572–583. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.6.14943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seigneurin-Berny D, Verdel A, Curtet S, Lemercier C, Garin J, Rousseaux S, Khochbin S. Identification of components of the murine histone deacetylase 6 complex: link between acetylation and ubiquitination signaling pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:8035–8044. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.23.8035-8044.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boyault C, Gilquin B, Zhang Y, Rybin V, Garman E, Meyer-Klaucke W, Matthias P, Muller CW, Khochbin S. HDAC6-p97/VCP controlled polyubiquitin chain turnover. EMBO J. 2006;25:3357–3366. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vij N. AAA ATPase p97/VCP: cellular functions, disease and therapeutic potential. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:2511–2518. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00462.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kitami MI, Kitami T, Nagahama M, Tagaya M, Hori S, Kakizuka A, Mizuno Y, Hattori N. Dominant-negative effect of mutant valosin-containing protein in aggresome formation. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:474–478. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ye Y. Diverse functions with a common regulator: ubiquitin takes command of an AAA ATPase. J Struct Biol. 2006;156:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johnston JA, Illing ME, Kopito RR. Cytoplasmic dynein/dynactin mediates the assembly of aggresomes. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2002;53:26–38. doi: 10.1002/cm.10057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yao TP. The role of ubiquitin in autophagy-dependent protein aggregate processing. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:779–786. doi: 10.1177/1947601910383277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bjorkoy G, Lamark T, Brech A, Outzen H, Perander M, Overvatn A, Stenmark H, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:603–614. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fusco C, Micale L, Egorov M, Monti M, D'Addetta EV, Augello B, Cozzolino F, Calcagni A, Fontana A, Polishchuk RS, et al. The E3-ubiquitin ligase TRIM50 interacts with HDAC6 and p62, and promotes the sequestration and clearance of ubiquitinated proteins into the aggresome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kirkin V, Lamark T, Sou YS, Bjorkoy G, Nunn JL, Bruun JA, Shvets E, McEwan DG, Clausen TH, Wild P, et al. A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Mol Cell. 2009;33:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lamark T, Johansen T. Aggrephagy: selective disposal of protein aggregates by macroautophagy. Int J Cell Biol. 2012:736905. doi: 10.1155/2012/736905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]