Abstract

Purpose

Mental health is critical to young adult health, as the onset of 75% of psychiatric disorders occurs by age 24 and psychiatric disorders early in life predict later behavioral health problems. Wealth may serve as a buffer against economic stressors. Family wealth may be particularly relevant for young adults by providing them with economic resources as they make educational decisions and move towards financial and social independence.

Methods

We used prospectively collected data from 2060 young adults aged 18–27 in 2005–2011 from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, a national cohort of US families. We examined associations between nonspecific psychological distress (measured with the K-6 scale) and childhood average household wealth during ages 0–18 years (net worth in 2010 dollars).

Results

In demographics-adjusted generalized estimating equation models, higher childhood wealth percentile was related to a lower prevalence of serious psychological distress: compared to lowest-quartile wealth, prevalence ratio (PR)=0.52 (0.32–0.85) for 3rd quartile and PR=0.41 (0.24–0.68) for 4th quartile. The associations were attenuated slightly by adjustment for parent education and more so by adjustment for childhood household income percentile.

Conclusions

Understanding the lifelong processes through which distinct aspects of socioeconomic status affect mental health can help us identify high-risk populations and take steps to minimize future disparities in mental illness.

Abbreviations: CDI, Children's Depression Inventory; CDS, Child Development Supplement; DALY, disability-adjusted life-year; GEE, generalized estimating equation; LOESS, locally weighted scatterplot smoothing; PSID, Panel Study of Income Dynamics; SES, socioeconomic status; TAS, Transition into Adulthood Study; US, United States of America

Keywords: USA, Mental health, Health disparities, Socioeconomic status, Young adults, Life course, Wealth, Multigenerational

Highlights

-

•

Less is known about wealth effects on health compared to other socioeconomic indicators.

-

•

Family wealth may help protect young adults’ mental health.

-

•

Greater family wealth was associated with better mental health among young adults.

Introduction

During young adulthood physical, cognitive, and emotional maturation combine with a transition in social roles to set the stage for life as an adult (Sawyer et al., 2012). Although the majority of adolescents and young adults are able to cope successfully with these transitions, others experience significant mood disruptions that result in disorder (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2002). Psychiatric disorders confer a substantial public health burden on young people (Patel, Flisher, Hetrick, & McGorry, 2007). The onset of three-fourths of psychiatric disorders occurs by the age of 24, and psychiatric disorders account for up to 30% of the disability-adjusted-life-years (DALYs) lost in adolescents and young adults (Kieling et al., 2011). In a nationally representative survey of over 10,000 adolescents and their caregivers, over 14% of US adolescents met criteria for a mood disorder, one third met criteria for an anxiety disorder, and over 11% met criteria for a substance abuse disorder (Merikangas et al., 2010). There are strong associations between adolescent mental health and indicators of well-being including educational achievement, substance use, violence and sexual health (Patel et al., 2007). Additionally, psychiatric disorders in youth predict mental illness during adulthood (Costello et al., 2006, Kessler et al., 2005).

Childhood socioeconomic status (SES) has been repeatedly identified as a risk factor for adolescent and young adult mental health (Pascoe et al., 2016). Low SES during childhood may increase children and adolescents’ exposure and vulnerability to stressors including daily hassles, traumatic events, violence and family conflict (Melchior et al., 2007, Pearlin, 1989). It may also increase young people's vulnerability to these stressors through pathways including dysregulation of the biological immune and stress-response systems, poorer nutrition, and a higher burden of chronic physical problems such as asthma and obesity (Pascoe et al., 2016, Pearlin, 1989). However, associations of SES and mental health have varied depending on the measure of SES, suggesting that different components of SES may influence mental health differently. For example, there is less evidence that childhood income influences adult mental health compared to parental education and occupation (Gilman et al., 2002, Poulton et al., 2002), suggesting that other aspects of parents’ finances may be influential on young adult mental health.

Family wealth may be one such important predictor of mental health during adolescence and young adulthood. Unlike income, which represents only monetary flow into a household, wealth represents both assets and debts accumulated over time (Keister & Moller, 2000). It may therefore serve as a better indicator of long-term financial circumstances than income, and also may be more sensitive to the broader economic context, age, job and health status (Keister and Moller, 2000). Many families earn enough income to remain above the Federal poverty level but may have large amounts of debt and few assets with which to buffer their family from economic stressors (Carter et al., 2009, Keister and Moller, 2000). Although measures of wealth are typically correlated with other SES measures, such as income, this correlation is far from perfect (Keister & Moller, 2000). Research on the effects of wealth on health is still evolving, and wealth remains understudied compared to other measures of SES. Wealth is an independent predictor of adult physical and mental health outcomes including mortality (Hajat, Kaufman, Rose, Siddiqi, & Thomas, 2010), stroke (Avendano & Glymour, 2008), metabolic syndrome (Perel et al., 2006), psychological distress (Carter et al., 2009), and mental health and life satisfaction (Headey & Wooden, 2004). No studies have yet addressed whether parental wealth is associated with mental health in young adults.

Family wealth is a promising predictor of young adult mental health compared to family income for several reasons. First, wealth may better capture socioeconomic inequality than income because disparities in wealth among American families are much greater than disparities in income (Allegreto, 2011). In 2012, families at or below the 90th percentile of the US wealth distribution earned about 70% of total national income but owned only about 30% of total national wealth (Saez & Zucman, 2016). Second, wealth may be less prone to health selection bias (i.e., reverse causation) than income because it is less immediately sensitive to short-term changes in earning capacity (Carter et al., 2009). Third, while associations of childhood income with mental health often diminish or disappear over time (Stansfeld, Clark, Rodgers, Caldwell, & Power, 2011), associations of childhood wealth and mental health may persist because wealth tends to be more stable and therefore represents a more consistent financial resource (Ostrove & Feldman, 1999). Finally, income and wealth are likely to represent different aspects of social status and social stratification. Although income is critical to purchasing power, wealth is an additional indicator of social and political power and prestige that creates opportunities for the future (Keister and Moller, 2000, Oliver and Shapiro, 2001). Family wealth may be particularly relevant for young adults’ mental health by providing them with both an economic resource and a source of social status on which they can draw as they make educational decisions and move towards financial and social independence.

More immediate factors may also be important mediators through which family wealth may influence young adult mental health. One possible mechanism is by facilitating higher educational attainment, which is strongly related to mental health in young adults (Adams, Knopf, & Park, 2014). Indeed, some studies have found that current SES fully accounted for associations between childhood SES and mental health during adolescence and adulthood (Headey and Wooden, 2004, Melchior et al., 2007, Poulton et al., 2002). Young adults’ financial circumstances may also mediate influence from family wealth on mental health. Young adults from wealthier families, for example, may have less debt than their peers from less wealthy families. Additionally, wealthy parents may contribute financially to help pay for their children's cost of living.

Using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), we examined whether greater family wealth during childhood is related to better mental health among 18–27-year-old participants in the supplemental Transition into Adulthood Study (TAS) of the PSID. We hypothesized that higher average family wealth during childhood, measured by household net worth, is associated with less psychological distress in young adulthood. We also hypothesized that associations of childhood average household wealth with psychological distress would persist after adjustment for other measures of family socioeconomic status (income and parent education). In a secondary exploratory analysis, we tested young adults' own education as a potential mediator and moderator. We hypothesized that associations of family wealth and psychological distress would be attenuated by (i.e., potentially mediated by) young adults’ own education. Finally, we hypothesized that associations between family wealth and better mental health would be largest among young adults with low education. Among these young adults, who are less able to draw on socioeconomic resources of their own, family wealth may be a particularly important resource.

Methods

Study population

The analysis sample included participants in the Transition into Adulthood Study (TAS), a supplemental study to the PSID. The PSID is a longitudinal study of a national sample of U.S. families started in 1968 (Institute for Social Research, 2016). In 1997 the Child Development Supplement (CDS), a supplemental cohort study of 3563 children living in PSID families, was started. All PSID families with a child aged 0–12 years in 1997 were eligible to participate, with up to two children included per family. Black and low-income families were oversampled in the PSID, and these sample characteristics are reflected in the CDS sample (Brown et al., 1996, Duffy and Sastry, 2012).

The TAS, which began in 2005, includes young people aged 18–28 who “aged out” of the CDS because they turned 18 or left high school (Institute for Social Research, 2008). Data are collected biennially, and newly eligible former CDS participants are incorporated into the sample at every wave. We pooled data from the 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2011 TAS study waves, resulting in a sample of 5321 observations corresponding to 2155 individual participants. After exclusion of observations with missing information for any analysis variables, the final analytic sample included N=4915 observations (2060 individuals) for primary analyses and N=4858 observations for secondary analyses investigating participant education as a mediator or moderator. The full analytic sample included 532 sibling pairs (i.e., 52% of the sample had a sibling in the sample).

Measures

The mental health outcome measure was the K-6 nonspecific psychological distress scale (range 0–24) (Kessler et al., 2002). The scale has been validated as a screening tool for clinically significant mental distress across different age groups (Kessler et al., 2003, Prochaska et al., 2012) and higher scores are related to poorer health behaviors, physical morbidity, emergency department use, and mortality (Pratt, 2009, Pratt et al., 2007, Stockbridge et al., 2014). We categorized the measure using previously defined clinically relevant cut-offs of 5–12 as moderate psychological distress and ≥13 as serious psychological distress (Kessler et al., 2003, Prochaska et al., 2012).

We linked participants to the PSID households in which they lived at each study wave from birth through age 18. Wealth information was collected as part of the main PSID interview in 1984, 1989, 1994, 1999, and in every (biennial) study wave since 1999. In each study wave, wealth was calculated as the household's net worth based on the head of household's report on eight categories: business equity (including farms); bank accounts, money market funds, certificates of deposit, government savings bonds, and treasury bills; real estate equity; equity in stock; equity in vehicles; equity in individual retirement accounts (IRAs); other assets (e.g., life insurance policy, rights in a trust or estate); and other debts. Except for the top 2–3 percentiles, estimates of net worth based on the PSID are similar to estimates from the Survey of Consumer Finances (Pfeffer, Schoeni, Kennickell, & Andreski, 2015), which is considered the gold standard for wealth measurement in the United States. We converted the wealth measure for each year to 2010 dollars using the Consumer Price Index (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014). We then created the childhood average household wealth measure by averaging all available year-specific wealth measures for each participant beginning with the year of his/her birth and ending with the year of his/her 18th birthday. We excluded observations with < 3 year-specific wealth measures from the analytic sample. Based on the extremely skewed distribution of childhood average household wealth (range was −$190,000 to $24,800,000 with median $19,900), as well as graphical representations of unadjusted associations between absolute and relative measures of wealth and the outcome, we opted for a measure of childhood average household wealth percentile (“childhood wealth percentile”), based on the sample distribution of wealth, as the main independent variable.

Potential confounders included gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, or multiracial or other race/ethnicity), age (centered at sample mean 20.83), region, and parent educational attainment information reported by the participants in the TAS. TAS participants also reported their own educational attainment (<high school, high school degree or GED, some college, current college student, college degree). Measures of nativity, low birth weight, home environment, and primary caregiver psychological distress (measured using the K-6 scale) had been previously reported by the participant's primary caregiver as part of the CDS in 1997 (2002 for caregiver psychological distress). As a measure of childhood mental health we used the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI) Short Form, (Institute for Social Research, 2010) administered as part of the CDS 2002 study wave to children aged ≥10 years. Household income information was collected in every study wave of the main PSID. We created a childhood average household income percentile (“childhood income percentile”) measure analogously to the average wealth measure, by averaging the year-specific income-to-poverty ratio for years in which the participant was aged 0–18 and converting the resulting average to a percentile (Grieger, Schoeni, & Danziger, 2008).

Analysis

All analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.2 (R Core Team, 2014). We first used locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) graphs to examine unadjusted associations of childhood wealth percentile, as well as the two other measures of childhood socioeconomic status (parent education and childhood income percentile), with psychological distress. Based on the LOESS graphs, we used a categorical measure of quartiles of childhood wealth percentile to model associations with psychological distress. We first used generalized estimating equations (GEE) multinomial logistic regression (Touloumis, 2014) to model associations of childhood wealth quartiles with moderate and serious psychological distress while accounting for correlated observations. We used the family identifier from the baseline 1997 CDS study wave as the clustering variable to account for correlations both within individuals and between siblings.

Because the multinomial logistic regression models showed no association between childhood wealth percentile and moderate psychological distress, for subsequent analyses we used GEE log-binomial regression (Hojsgaard, Halekoh, & Yan, 2006) to estimate prevalence ratios for childhood wealth percentile of serious psychological distress compared to low or moderate psychological distress (combined into a single reference category). After adjustment for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, additional adjustment for region, study wave, family income in the year of birth, nativity, caregiver psychological distress, father's education, or childhood mental health did not appreciably change estimates for childhood wealth percentile; therefore, we did not include these variables in final models. We estimated models additionally adjusted for mother's education and childhood income percentile in order to determine if associations between childhood wealth percentile and the outcome were robust to adjustment for these additional measures of childhood socioeconomic status. Finally, we tested models additionally adjusting for participant education as a mediator. We also tested interactions between childhood wealth percentile and participant education. Survey weights were not incorporated into analyses because our goal was to test etiologic hypotheses in our sample rather than to estimate national prevalences and our regression models adjust for the major sociodemographic characteristics included in PSID survey weights; interpretability would also be complicated by our pooled sample (Hajat et al., 2010).

Results

Just over half the sample was female, the majority were non-Hispanic and of white (46%) or black (40%) race, and median age was 20 (Table 1). Prevalences of moderate and serious psychological distress were 44% and 4%, respectively (not shown). There were no large differences in covariate distributions between observations with low and moderate psychological distress. Childhood wealth percentile, childhood income percentile, mother's education, and participant education all varied inversely with serious psychological distress. The three measures of childhood socioeconomic status were correlated but not perfectly so: Spearman rank correlations were 0.71 for childhood wealth percentile and childhood income percentile, 0.38 for childhood wealth percentile and mother's years of education, and 0.56 for childhood income percentile and mother's years of education. The Pearson correlation between absolute measures of childhood average wealth and childhood average income (often reported in comparisons of income and wealth) was 0.34.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics, by psychological distress level (N=4915).

| Total |

Psychological Distressa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Low | Moderate | Serious | |

| Total (N, %) | – | 2540 (52) | 2177 (44) | 198 (4) |

| Female (N, %) | 2540 (52) | 1282 (51) | 1182 (54) | 113 (57) |

| Race/ethnicity (N, %) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2275 (46) | 1200 (47) | 989 (45) | 86 (43) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1984 (40) | 1016 (40) | 888 (41) | 80 (40) |

| Hispanic | 472 (10) | 239 (9) | 214 (10) | 19 (10) |

| Other | 184 (4) | 85 (4) | 86 (4) | 13 (7) |

| Age (median [range]) | 20 (17–27) | 21 (17–27) | 20 (17–27) | 20 (17–27) |

| Region (N, %)b | ||||

| North Central | 1192 (24) | 326 (23) | 294 (25) | 23 (32) |

| Northeast | 643 (13) | 580 (13) | 548 (14) | 64 (12) |

| South | 2228 (46) | 1195 (47) | 956 (44) | 77 (39) |

| West | 833 (17) | 424 (17) | 375 (17) | 34 (17) |

| Childhood average household wealth (median [range])c | 19.9 (−190–24,850) | 21.4 (−190–24,850) | 19.4 (−190–24,850) | 12 (−155–5056) |

| Quartile 1d | 0 (−190–4.1) | 620 (24) | 546 (25) | 66 (33) |

| Quartile 2d | 10.1 (4.1–19.9) | 606 (24) | 556 (26) | 64 (32) |

| Quartile 3d | 43.1 (20–89.3) | 663 (26) | 531 (24) | 37 (19) |

| Quartile 4d | 209 (89.3–24,850) | 651 (26) | 544 (25) | 31 (16) |

| Childhood average household income-poverty ratio (median [range]) | 2.5 (0.2–50.7) | 2.6 (0.3–40.1) | 2.5 (0.2–50.7) | 2.1 (0.4–50.7) |

| Quartile 1d | 1.0 (0.2–1.5) | 592 (23) | 573 (26) | 64 (32) |

| Quartile 2d | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 644 (25) | 531 (24) | 54 (27) |

| Quartile 3d | 3.2 (2.5–3.9) | 625 (25) | 548 (25) | 57 (29) |

| Quartile 4d | 5.3 (3.9–50.7) | 679 (27) | 525 (24) | 23 (12) |

| Mother’s years education (N, %) | ||||

| < 12 | 593 (12) | 300 (12) | 266 (12) | 27 (14) |

| 12 | 1742 (35) | 886 (35) | 766 (35) | 90 (46) |

| 12–15 | 1422 (29) | 737 (29) | 635 (29) | 50 (25) |

| ≥ 16 | 1158 (24) | 617 (24) | 510 (23) | 31 (16) |

| Participant education (N, %)e | ||||

| No high school degree or GED | 456 (9) | 208 (8) | 212 (10) | 36 (19) |

| High school degree/GED | 1045 (22) | 506 (20) | 487 (23) | 52 (27) |

| Some college/2-year degree | 884 (18) | 458 (18) | 386 (18) | 40 (21) |

| Enrolled in college, no prior degree | 1921 (40) | 994 (40) | 871 (40) | 56 (29) |

| 4-year degree or higher | 552 (11) | 340 (14) | 202 (10) | 10 (5) |

Measured using K-6 nonspecific psychological distress scale. Low=0–4, Moderate=5–12, Serious=13–24.

Excludes 2 observations with missing region and 17 observations with location outside the US. West region includes 2 observations in Alaska or Hawaii.

In thousands of dollars.

Total column is median (range). Psychological distress columns are N (%).

N=4858 (i.e., missing for n=57).

In unadjusted multinomial logistic regression models, higher childhood wealth quartile was monotonically related to a lower prevalence of serious psychological distress but was not related to the prevalence of moderate psychological distress (Table 2, Model 1). Odds of serious psychological distress were very similar for quartiles 1 and 2 (odds ratio [OR] for quartile 2 vs. quartile 1=0.91 [(95% confidence interval) 0.59–1.40]) and for quartiles 3 and 4 (compared to quartile 1, OR=0.52 [0.31–0.87] and OR=0.45 [0.27–0.76], respectively). After adjustment for gender, race/ethnicity, and age, young adults in the highest quartile of childhood wealth had 0.42 (0.24–0.72) times the odds of serious psychological distress compared to those in the lowest quartile, but nearly the same odds of moderate psychological distress (OR=1.01 [0.80–1.28]).

Table 2.

Odds ratios from multinomial logistic regression of moderate (K6 5–12) and serious (K6 >= 13) psychological distress (N=4915).

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate distress (n=2177) |

Serious distress (n=198) |

Moderate distress (n=2177) |

Serious distress (n=198) |

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Childhood average household wealth percentile (vs. lowest quartile) | ||||||||

| Quartile 2 | 1.02 | (0.83, 1.26) | 0.91 | (0.59, 1.40) | 1.03 | (0.83, 1.26) | 0.89 | (0.58, 1.38) |

| Quartile 3 | 0.90 | (0.74, 1.10) | 0.52 | (0.31, 0.87) | 0.94 | (0.76, 1.15) | 0.51 | (0.30, 0.84) |

| Quartile 4 | 0.97 | (0.79, 1.19) | 0.45 | (0.27, 0.76) | 1.01 | (0.80, 1.28) | 0.42 | (0.24, 0.72) |

| Female (vs. Male) | 1.20 | (1.03, 1.39) | 1.31 | (0.92, 1.88) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity (vs. non-Hispanic White) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 1.07 | (0.81, 1.41) | 0.85 | (0.40, 1.80) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.09 | (0.91, 1.31) | 0.86 | (0.56, 1.32) | ||||

| Other race/ethnicity | 1.14 | (0.78, 1.68) | 1.54 | (0.69, 3.43) | ||||

| Age (per year)a | 0.95 | (0.92, 0.97) | 0.92 | (0.86, 0.98) | ||||

Age centered at sample mean of 20.83.

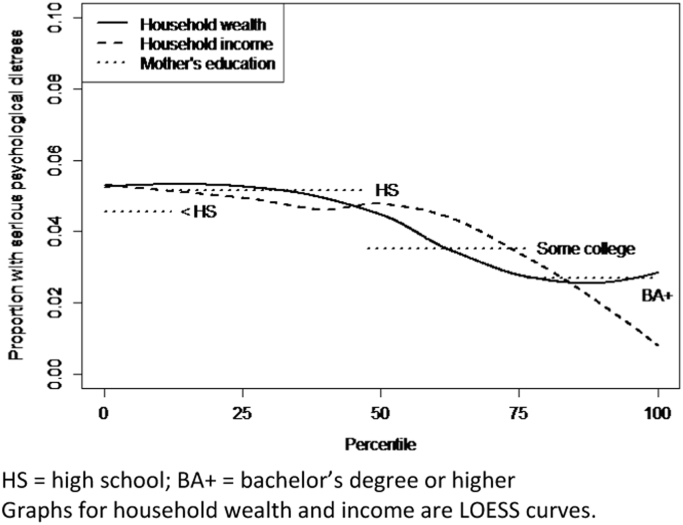

For all three measures of childhood SES (childhood wealth percentile, childhood income percentile, mother's education), there was little evidence in LOESS plots of an association between socioeconomic status and serious psychological distress below the 50th percentile of the socioeconomic status measure (Fig. 1), with roughly 5% of these low-SES-background young adults experiencing serious distress. Above the 50th percentile, all three measures of childhood SES were negatively associated with a lower prevalence of serious psychological distress. At the 85th percentile of the wealth and income distribution, and mother's education of at least a bachelor's degree, roughly 2.5% had serious psychological distress.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of serious psychological distress among young adults by childhood average household wealth percentile, childhood average household income percentile, and mother's education HS=high school; BA+=bachelor's degree or higher. Graphs for household wealth and income are LOESS curves.

Table 3 shows results from log-binomial regression models of serious psychological distress, with low and moderate distress combined into a single referent group. Similar to the multinomial logistic regression models in Table 2, childhood wealth in quartiles 3 and 4 were related to a lower prevalence of serious psychological distress compared to the lowest quartile (in demographics-adjusted models, PR=0.90 [0.60–1.34], PR=0.52 [0.32–0.85], and PR=0.41 [0.24–0.68] for quartiles 2, 3 and 4, respectively). The association between greater childhood wealth and lower serious psychological distress was not substantively attenuated by adjustment for mother's education (Table 3, model 3), but the association for quartile 4 was more substantially attenuated by adjustment for childhood income percentile (Table 3, model 4). After adjustment for both mother's education and childhood income, prevalence ratios for the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartiles of wealth were 0.90 (0.61, 1.34), 0.57 (0.34–0.97), and 0.60 (0.33–1.09), respectively. This suggests that childhood wealth above the median value may influence psychological distress even independent of these other measures of SES, although the quartile 4 result is not statistically significant at α=0.05. Because wealth and income influence each other over time, these mutually adjusted estimates are likely underestimates of the true total effects of both measures. However, we present them as conservative estimates of childhood household wealth independent of income.

Table 3.

Prevalence ratios from generalized estimating equation log-binomial regression models of serious psychological distress (N=4915; n=198 with serious psychological distress).

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 95% CI | pa | PR | 95% CI | pa | PR | 95% CI | pa | PR | 95% CI | pa | PR | 95% CI | pa | |

| Average family wealth percentile (vs. Quartile 1) | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.16 | 0.15 | ||||||||||

| Quartile 2 | 0.90 | (0.61, 1.34) | 0.90 | (0.60, 1.34) | 0.88 | (0.59, 1.31) | 0.91 | (0.62, 1.35) | 0.90 | (0.61, 1.34) | |||||

| Quartile 3 | 0.55 | (0.34, 0.88) | 0.52 | (0.32, 0.85) | 0.53 | (0.32, 0.86) | 0.59 | (0.35, 0.98) | 0.57 | (0.34, 0.97) | |||||

| Quartile 4 | 0.44 | (0.27, 0.72) | 0.41 | (0.24, 0.68) | 0.46 | (0.27, 0.77) | 0.60 | (0.33, 1.09) | 0.60 | (0.33, 1.09) | |||||

| Female (vs. Male) | 1.15 | (0.83, 1.60) | 1.15 | (0.83, 1.59) | 1.17 | (0.85, 1.63) | 1.17 | (0.84, 1.62) | |||||||

| Race/ethnicity (vs. non-Hispanic White) | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.11 | |||||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.80 | (0.42, 1.50) | 0.83 | (0.42, 1.64) | 0.74 | (0.38, 1.42) | 0.80 | (0.40, 1.59) | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.84 | (0.58, 1.22) | 0.83 | (0.57, 1.21) | 0.76 | (0.52, 1.11) | 0.76 | (0.52, 1.12) | |||||||

| Other race/ethnicity | 1.50 | (0.78, 2.91) | 1.59 | (0.82, 3.10) | 1.47 | (0.77, 2.81) | 1.57 | (0.82, 3.01) | |||||||

| Age (per year)b | 0.95 | (0.89, 1.01) | 0.95 | (0.89, 1.00) | 0.95 | (0.89, 1.00) | 0.95 | (0.89, 1.00) | |||||||

| Mother’s education (vs. < high school) | 0.31 | 0.51 | |||||||||||||

| High school | 1.32 | (0.78, 2.24) | 1.36 | (0.80, 2.30) | |||||||||||

| Some college | 1.07 | (0.62, 1.83) | 1.11 | (0.63, 1.95) | |||||||||||

| College degree | 0.86 | (0.45, 1.62) | 1.05 | (0.56, 1.97) | |||||||||||

| Average family income percentile (vs. Quartile 1) | 0.01 | 0.02 | |||||||||||||

| Quartile 2 | 0.82 | (0.54, 1.26) | 0.82 | (0.53, 1.27) | |||||||||||

| Quartile 3 | 1.02 | (0.63, 1.64) | 1.04 | (0.63, 1.72) | |||||||||||

| Quartile 4 | 0.41 | (0.21, 0.81) | 0.44 | (0.22, 0.88) | |||||||||||

p-Values are for joint tests of the categories of categorical variables.

Age centered at sample mean of 20.83.

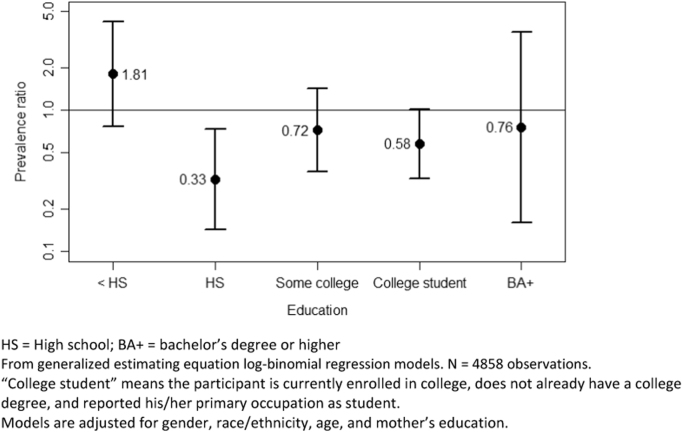

Because of sample size concerns, we ran more parsimonious models for the descriptive mediation analyses. Guided by the results from the models in Table 3, we included a single indicator for above-median childhood average household wealth. We adjusted for mother's education but not childhood income percentile because of the above-mentioned mutual influence of income and wealth on each other over time. Higher participant education level was strongly associated with lower serious psychological distress prevalence (Table 4, model 2), but its inclusion in the model only modestly attenuated the coefficient for childhood wealth: 0.56 (0.38–0.82) without participant education (Table 4, model 1) and 0.65 (0.44–0.95) including education (Table 4, model 2). There was evidence of interaction between childhood wealth and participant education (Table 4, model 3; interaction p=0.05), supporting the hypothesis that participant education moderates effects of childhood wealth on psychological distress. Prevalence ratios for above- vs. below-median wealth for each level of participant education are shown in Fig. 2. Confidence intervals were wide, reflecting the small sample sizes after stratification by participant education, but there was some suggestion that higher childhood average household wealth was related to a higher prevalence of serious psychological distress among participants without a high school degree (PR=1.81 [0.77–4.25]), but a lower prevalence of serious psychological distress among more highly educated participants. This inverse association among participants with at least a high school degree decreased in magnitude with higher participant education, ranging from PR=0.33 (0.14–0.74) among those with a high school degree to PR=0.76 (0.16–3.59) among those with a bachelor's degree or higher.

Table 4.

Adjusted prevalence ratios from generalized estimating equation log-binomial regression models of serious psychological distress (N=4858).

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | ||

| Above-median childhood average household wealth percentile (vs. ≤50th percentile) | 0.56 | (0.38, 0.82) | 0.65 | (0.44, 0.95) | 1.81 | (0.77, 4.25) | |

| Female (vs. Male) | 1.14 | (0.81, 1.58) | 1.21 | (0.87, 1.67) | 1.22 | (0.88, 1.70) | |

| Race/ethnicity (vs. non-Hispanic White) | |||||||

| Hispanic | 0.79 | (0.42, 1.46) | 0.83 | (0.45, 1.54) | 0.80 | (0.43, 1.49) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.83 | (0.57, 1.22) | 0.78 | (0.54, 1.13) | 0.77 | (0.53, 1.11) | |

| Other race/ethnicity | 1.56 | (0.81, 3.02) | 1.56 | (0.78, 3.09) | 1.58 | (0.82, 3.06) | |

| Age (per year)a | 0.96 | (0.90, 1.02) | 0.96 | (0.90, 1.02) | 0.96 | (0.90, 1.02) | |

| Mother’s education (vs. ≤ high school) | |||||||

| Some college | 0.86 | (0.61, 1.210 | 0.95 | (0.68, 1.33) | 0.95 | (0.68, 1.33) | |

| College degree | 0.65 | (0.40, 1.06) | 0.83 | (0.51, 1.35) | 0.84 | (0.52, 1.34) | |

| Education (vs. < High school)b | |||||||

| High school degree/GED | 0.71 | (0.44, 1.14) | 0.98 | (0.58, 1.64) | |||

| Some college/2-year degree | 0.69 | (0.41, 1.16) | 0.82 | (0.46, 1.46) | |||

| Enrolled in college, no prior degree | 0.42 | (0.25, 0.69) | 0.53 | (0.30, 0.95) | |||

| College degree | 0.36 | (0.16, 0.81) | 0.39 | (0.09, 1.61) | |||

| Average family wealth percentile×Educationc | |||||||

| Wealth×High school degree/GED | 0.18 | (0.06, 0.55) | |||||

| Wealth×Some college/2-year degree | 0.40 | (0.13, 1.20) | |||||

| Wealth×Enrolled in college, no prior degree | 0.32 | (0.11, 0.90) | |||||

| Wealth×College degree | 0.42 | (0.07, 2.49) | |||||

Age centered at sample mean of 20.83.

Joint p-value for participant education in Model 2=0.005.

Values are exponentiated interaction terms. Joint p-value for interaction terms in Model 3=0.05.

Fig. 2.

Adjusted prevalence ratios of serious psychological distress for above-median childhood average household wealth (vs. at or below median), by participant education level. HS=High school; BA+=bachelor's degree or higher. From generalized estimating equation log-binomial regression models. N=4858 observations. “College student” means the participant is currently enrolled in college, does not already have a college degree, and reported his/her primary occupation as student. Models are adjusted for gender, race/ethnicity, age, and mother's education.

Discussion

We found that young adults who grew up in families with greater household wealth had a lower prevalence of serious psychological distress compared to young adults from families with below-median wealth. This association was robust to adjustment for parent education but was attenuated by adjustment for childhood income. There was no evidence of an association between childhood wealth and moderate psychological distress in our sample. Our results provide evidence that childhood wealth may contribute to the burden of serious psychological distress in young adults, even independent of other measures of socioeconomic background. Because the various constituents of socioeconomic status influence each other over time (e.g., income can create future wealth, and wealth can create future income), causal interpretation of mutually adjusted socioeconomic measures is problematic. Yet our results suggest that further research in this area is warranted, given the large inequalities in wealth in the United States and plausible causal mechanisms specific to wealth.

Wealth–health associations remain understudied compared to studies of other socioeconomic measures despite calls over the last decade for research examining wealth's role in population health and health disparities (Baum, 2005, Pollack et al., 2007, Pollack et al., 2013). A 2007 systematic review of 29 US-based studies concluded that higher wealth was consistently associated with lower mortality, and generally with less chronic disease, better self-rated health, and better functional status (Pollack et al., 2007). Associations tended to be more robust in studies using more detailed measures of wealth. The review included 6 studies of mental health (4 examined depression or depressive symptoms; 1 mood disorder, anxiety disorders, and depression; and 1 cognitive ability), of which 5 found associations between higher wealth and better mental health in either the full sample or a subset of the sample. All of the studies used measures of concurrent wealth and none focused on young adults.

Since then, a handful of studies have examined wealth and mental or behavioral health. Results have been consistent with ours. A 2009 New Zealand study of adults aged ≥ 25 concluded that higher wealth during the previous year was associated with higher odds of moderate or serious psychological distress measured using the K-10 scale (of which the K-6 is an abbreviated version) (Carter et al., 2009). Using data from adult respondents in the main PSID, Yilmazer, Babiarz, and Liu (2015) found that loss of housing wealth during the Great Recession was associated with small increases in psychological distress after adjustment for other sources of wealth. Using 2005–2007 PSID-TAS data and a cumulative measure of family wealth similar to the one we used, Patrick et al. (2012) found that higher family wealth percentile was associated with less smoking among young adults, but higher alcohol and marijuana use.

In a secondary exploratory analysis, we found that after additionally adjusting for participants’ educational attainment, the magnitude of the association between childhood average household wealth and serious psychological distress was modestly (about 20%) attenuated. However, we found evidence suggestive of a qualitative interaction between young adults’ education and childhood wealth such that greater childhood wealth was associated with a higher prevalence of serious psychological distress among participants with low education but a lower prevalence of serious psychological distress among participants with more education. One possibility is that participants who grew up in wealthy families but failed to earn a high school degree represent a qualitatively distinct, downwardly mobile population. The unexpected association between higher family wealth and worse mental health in this group may therefore reflect distress associated with the large incongruity between their socioeconomic background and their socioeconomic achievement (i.e., status inconsistency), or specific unobserved life circumstances that resulted in both educational difficulties and psychological distress. Among participants with a high school degree, the lower-magnitude prevalence ratios at higher education levels are consistent with the hypothesis that family wealth provides a buffer that is less important for young adults who have themselves achieved higher levels of SES. That said, the results of these models should be interpreted with caution, as cell sizes were small after stratification by participant education and most confidence intervals included the null. Interestingly, a recent study of student loan debt and psychological functioning in young adults aged 25–31 found an interaction such that higher debt was related to poorer functioning among participants whose families had positive net worth but better functioning among those whose families had negative wealth (Walsemann, Gee, & Gentile, 2015). This result, along with ours, suggests that effects of parental wealth on mental health may vary widely by young adults’ own socioeconomic circumstances.

The associations we found between childhood wealth (as well as for childhood income and parent education) and serious psychological distress were limited to the upper 50% of the sample SES distribution. This result is seemingly at odds with previous research that has associated very low SES, along with attendant exposure to adverse experiences, with poor health (Kalmakis and Chandler, 2015, Pascoe et al., 2016). It is worth noting, however, that levels of wealth in our sample were low: median childhood wealth was $19,900 while median household wealth in the US in 2000 was close to $74,000 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). Therefore, the threshold for the associations we observed occurred at relatively low levels of wealth. It is also possible that our results are specific to the outcome of nonspecific psychological distress and life stage of our sample (young adulthood), which have not been previously examined. For example, the K-6 scale in this population may capture distress primarily related to stressors associated with the transition to social and economic independence. There may be a threshold of familial socioeconomic resources that is required in order for them to be used to prevent or alleviate this distress. Future research should investigate potential differences by age in SES effects on specific aspects of mental health.

Our analysis was subject to several limitations. Adjustment for childhood depressive symptoms in 2002 only slightly attenuated estimates for childhood wealth (data not shown), which provides some evidence that our results may not result from reverse causation. However, this measure of childhood mental health was available only on a subset of participants who were aged ≥ 10 years (n=3798; 77%), and who therefore had already experienced 10 years or more of the age span covered by our childhood wealth measure. Furthermore, the CDI-Short Form may not be the most relevant measure to capture childhood precursors to psychological distress as measured by the K-6 scale. Reverse causation may also have played a role in associations between participant education and the outcome. Our results may have been affected by measurement error, particularly because of the reliance on self-reported information. The K-6 scale, while validated and widely used, does not identify individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for specific mental illnesses. Future research using measures of incident mental illness can help strengthen the causal evidence for an effect of childhood wealth on mental health. Finally, our wealth measure did not distinguish between different longitudinal patterns of wealth that might result in the same cumulative average measure. Future research could consider how trajectories of SES, including wealth, throughout the lifespan influence mental health in young adulthood. Relatedly, household wealth shocks, such as those experienced by many American families during the 2007–2009 Great Recession (Pfeffer, Danziger, & Schoeni, 2013), may have implications for the future mental health of children growing up in these households. Strengths of our analysis include the use of in-depth, prospectively collected wealth information, the national scope and racial/ethnic and socioeconomic diversity of the sample, and the use of a validated mental health screening scale.

Another potentially fruitful area of research is the role of lack of childhood wealth as a source of underlying vulnerability, predisposing individuals to more serious mental health consequences of exposure to stressors. It may therefore be elucidative to investigate modification by childhood wealth of associations between stressors and mental health. Relatedly, family wealth may help explain or modify racial/ethnic health disparities (Pollack et al., 2013), given stark racial/ethnic inequalities in wealth and intergenerational wealth transfers (Keister and Moller, 2000, Oliver and Shapiro, 1995).

Mental illness is a leading cause of disability worldwide. Like other chronic illnesses, mental illness experienced in adulthood may have origins in life circumstances experienced years before. Understanding these lifelong processes can help us identify those at high risk as well as take steps to minimize future health disparities based on current inequalities. This may in turn help reduce future socioeconomic inequalities, as young adulthood is a critical time with respect to future educational and occupational achievement. Furthermore, policies and interventions aimed at reducing persistent wealth inequality across generations may play a role in reducing mental health disparities.

Funding

The collection of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics data used in this study was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant R01 HD069609) and the National Science Foundation (Award 1157698).

Appendix A

See Table A1.

Table A1.

Sample characteristics, by quartile of childhood average household wealth (N=4915).

| Childhood Average Household Wealth |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Quartile 1 ($−190,000 to $4,100) | Quartile 2 ($4,100 to $19,900) | Quartile 3 ($19,900 to $89,300) | Quartile 4 ($89,300 to $24,850,000) |

| Female (N, %) | 650 (53) | 676 (55) | 616 (50) | 635 (52) |

| Race/ethnicity (N, %) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 293 (24) | 391 (32) | 654 (53) | 937 (76) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 747 (61) | 635 (52) | 432 (35) | 170 (14) |

| Hispanic | 142 (11) | 155 (13) | 100 (8) | 75 (6) |

| Other | 50 (4) | 45 (4) | 45 (4) | 44 (4) |

| Age in years (median [range]) | 20 (17–27) | 20 (17–27) | 20 (17–27) | 20 (17–27) |

| Region (N, %)a | ||||

| North Central | 294 (24) | 242 (20) | 304 (25) | 352 (29) |

| Northeast | 149 (12) | 99 (8) | 176 (14) | 219 (18) |

| South | 643 (52) | 663 (54) | 546 (44) | 376 (31) |

| West | 142 (12) | 216 (18) | 203 (16) | 272 (22) |

| Childhood average household income-poverty ratio (N, %) | ||||

| Quartile 1 | 710 (58) | 408 (33) | 89 (7) | 22 (2) |

| Quartile 2 | 339 (28) | 498 (41) | 292 (24) | 100 (8) |

| Quartile 3 | 140 (11) | 268 (22) | 516 (42) | 306 (25) |

| Quartile 4 | 43 (3) | 52 (4) | 334 (27) | 798 (65) |

| Mother’s years education (N, %) | ||||

| <12 | 282 (23) | 212 (17) | 79 (6) | 20 (2) |

| 12 | 491 (40) | 538 (44) | 461 (37) | 252 (21) |

| 12–15 | 325 (26) | 354 (29) | 425 (35) | 318 (26) |

| ≥16 | 134 (11) | 122 (10) | 266 (22) | 636 (52) |

| Participant education (N, %)b | ||||

| No high school degree or GED | 237 (19) | 141 (12) | 51 (4) | 27 (2) |

| High school degree/GED | 377 (31) | 329 (27) | 240 (20) | 99 (8) |

| Some college/2-year degree | 209 (17) | 264 (22) | 236 (19) | 175 (14) |

| Enrolled in college, no prior degree | 329 (27) | 401 (33) | 526 (43) | 665 (55) |

| 4-year degree or higher | 66 (5) | 74 (6) | 161 (13) | 251 (22) |

Excludes 2 observations with missing region and 17 observations with location outside the US. West region includes 2 observations in Alaska or Hawaii.

N=4858 (i.e., missing for n=57).

References

- Adams S.H., Knopf D.K., Park M.J. Prevalence and treatment of mental health and substance use problems in the early emerging adult years in the United States: Findings from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Emerging Adulthood. 2014;2(3):163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Allegreto, S. (2011). The state of the working America’s wealth, 2011 (292). Retrieved from Washington, DC. 〈http://www.epi.org/publication/the_state_of_working_americas_wealth_2011/〉

- Avendano M., Glymour M.M. Stroke disparities in older Americans is wealth a more powerful indicator of risk than income and education? Stroke. 2008;39(5):1533–1540. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum F. Wealth and health: The need for more strategic public health research. Journal of Epidemiology Community Health. 2005;59(7):542–545. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.021147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C., Duncan G.J., Stafford F.P. Data watch – The Panel Study of Income Dynamics. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1996;10(2):155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2014). Databases, tables & calculators by subject. Retrieved from 〈http://www.bls.gov/data/〉

- Carter K.N., Blakely T., Collings S., Imlach Gunasekara F., Richardson K. What is the association between wealth and mental health? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2009;63(3):221–226. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.079483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D., Rogosch F.A. A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(1):6–20. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello E.J., Foley D.L., Angold A. 10-year research update review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: II. Developmental epidemiology. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(1):8–25. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000184929.41423.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, D., & Sastry, N. (2012). An assessment of the national representativeness of children in the 2007 Panel Study of Income Dynamics. Retrieved from Ann Arbor, MI. 〈https://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/publications/Papers/tsp/2012-01_National_Representativeness_Children_2007_psid.pdf#page=1〉

- Gilman S.E., Kawachi I., Fitzmaurice G.M., Buka S.L. Socioeconomic status in childhood and the lifetime risk of major depression. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31(2):359–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieger, L. D., Schoeni, R. F., & Danziger, S. (2008). Accurately measuring the trend in poverty in the United States using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. Retrieved from Ann Arbor, MI:

- Hajat A., Kaufman J.S., Rose K.M., Siddiqi A., Thomas J.C. Long-term effects of wealth on mortality and self-rated health status. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;173(2):192–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq348. (doi:kwq348 [pii)( 10.1093/aje/kwq348) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headey B., Wooden M. The Effects of Wealth and Income on Subjective Well-Being and Ill-Being*. Economic record. 2004;80(s1):S24–S33. [Google Scholar]

- Hojsgaard S., Halekoh U., Yan J. The R package geepack for general estimating equations. Journal of Statistical Software. 2006;15(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Social Research . Institute for Social Research; Ann Arbor, MI: 2008. Transition to adulthood study: Overview. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Social Research (2010). The panel study of income dynamics child development supplement: User guide for CDS-II. Retrieved from Ann Arbor, MI.

- Institute for Social Research (2016). The panel study of income dynamics. Retrieved from 〈http://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/〉

- Kalmakis K.A., Chandler G.E. Health consequences of adverse childhood experiences: A systematic review. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. 2015;27(8):457–465. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keister L.A., Moller S. Vol. 26. 2000. Wealth Inequality in the United States; pp. 63–81. (Annual Review of Sociology). [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Andrews G., Colpe L.J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D.K., Normand S.L., Zaslavsky A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Barker P.R., Colpe L.J., Epstein J.F., Gfroerer J.C., Hiripi E., Zaslavsky A.M. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. (doi:yoa20567 [pii) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Merikangas K.R., Walters E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieling C., Baker-Henningham H., Belfer M., Conti G., Ertem I., Omigbodun O., Rahman A. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1515–1525. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior M., Moffitt T.E., Milne B.J., Poulton R., Caspi A. Why do children from socioeconomically disadvantaged families suffer from poor health when they reach adulthood? A life-course study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;166(8):966–974. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K.R., He J.-p, Burstein M., Swanson S.A., Avenevoli S., Cui L., Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M.L., Shapiro T.M. Urbana: University of Illinois Press; 1995. Black wealth/white wealth. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M.L., Shapiro T.M. Wealth and racial stratification. In: Smelser N.J., Wilson W.J., Mitchell F., editors. Vol. II. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 222–251. (America becoming: Racial trends and their consequences). [Google Scholar]

- Ostrove J.M., Feldman P. Education, income, wealth, and health among Whites and African Americans. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;896(1):335–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe J.M., Wood D.L., Duffee J.H., Kuo A., Committee On Psychosocial Aspects Of, C., Family, H., & Council On Community, P Mediators and adverse effects of child poverty in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4) doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V., Flisher A.J., Hetrick S., McGorry P. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007;369(9569):1302–1313. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick M.E., Wightman P., Schoeni R.F., Schulenberg J.E. Socioeconomic status and substance use among young adults: A comparison across constructs and drugs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73(5):772–782. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30(3):241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perel P., Langenberg C., Ferrie J., Moser K., Brunner E., Marmot M. Household Wealth and the Metabolic Syndrome in the Whitehall II Study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(12):2694–2700. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer F.T., Danziger S., Schoeni R.F. Wealth disparities before and after the Great Recession. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2013;650(1):98–123. doi: 10.1177/0002716213497452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, F. T., Schoeni, R. F., Kennickell, A. B., & Andreski, P. M. (2015). Measuring wealth and wealth inequality: Comparing two US surveys. Retrieved from Ann Arbor, MI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pollack C.E., Chideya S., Cubbin C., Williams B., Dekker M., Braveman P. Should health studies measure wealth? A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33(3):250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack C.E., Cubbin C., Sania A., Hayward M., Vallone D., Flaherty B., Braveman P.A. Do wealth disparities contribute to health disparities within racial/ethnic groups? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2013;67(5):439–445. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-200999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulton R., Caspi A., Milne B.J., Thomson W.M., Taylor A., Sears M.R., Moffitt T.E. Association between children’s experience of socioeconomic disadvantage and adult health: A life-course study. Lancet. 2002;360(9346):1640–1645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11602-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt L.A. Serious psychological distress, as measured by the K6, and mortality. Annals of Epidemiology. 2009;19(3):202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt L.A., Dey A.N., Cohen A.J. Characteristics of adults with serious psychological distress as measured by the K6 scale: United States, 2001–04. Advanced Data. 2007;(382):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J.J., Sung H.Y., Max W., Shi Y., Ong M. Validity study of the K6 scale as a measure of moderate mental distress based on mental health treatment need and utilization. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2012;21(2):88–97. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from 〈http://www.R-project.org/〉

- Saez E., Zucman G. Wealth inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from capitalized income tax data. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2016;131(2):519–578. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer S.M., Afifi R.A., Bearinger L.H., Blakemore S.J., Dick B., Ezeh A.C., Patton G.C. Adolescence: A foundation for future health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1630–1640. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld S., Clark C., Rodgers B., Caldwell T., Power C. Repeated exposure to socioeconomic disadvantage and health selection as life course pathways to mid-life depressive and anxiety disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2011;46(7):549–558. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0221-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockbridge E.L., Wilson F.A., Pagan J.A. Psychological distress and emergency department utilization in the United States: Evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2014;21(5):510–519. doi: 10.1111/acem.12369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touloumis A. R package multgee: A generalized estimating equations solver for multinomial responses. Journal of Statistical Software. 2014;64(8) 〈http://www.jstatsoft.org/v64/i08〉 (Retrieved from) [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2014). Wealth and asset ownership. Retrieved from 〈https://www.census.gov/people/wealth/〉

- Walsemann K.M., Gee G.C., Gentile D. Sick of our loans: Student borrowing and the mental health of young adults in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;124:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmazer T., Babiarz P., Liu F. The impact of diminished housing wealth on health in the United States: Evidence from the Great Recession. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;130:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]