Abstract

GlnD is a bifunctional uridylyltransferase/uridylyl-removing enzyme and is thought to be the primary sensor of nitrogen status in the cell. It plays an important role in nitrogen assimilation and metabolism by reversibly regulating the modification of PII proteins, which in turn regulate a variety of other proteins. We report here the characterization of glnD mutants from the photosynthetic, nitrogen-fixing bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum and the analysis of the roles of GlnD in the regulation of nitrogen fixation. Unlike glnD mutations in Azotobacter vinelandii and some other bacteria, glnD deletion mutations are not lethal in R. rubrum. Such mutants grew well in minimal medium with glutamate as the sole nitrogen source, although they grew slowly with ammonium as the sole nitrogen source (MN medium) and were unable to fix N2. The slow growth in MN medium is apparently due to low glutamine synthetase activity, because a ΔglnD strain with an altered glutamine synthetase that cannot be adenylylated can grow well in MN medium. Various mutation and complementation studies were used to show that the critical uridylyltransferase activity of GlnD is localized to the N-terminal region. Mutants with intermediate levels of uridylyltransferase activity are differentially defective in nif gene expression, the posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase, and NtrB/NtrC function, indicating the complexity of the physiological role of GlnD. These results have implications for the interpretation of results obtained with GlnD in many other organisms.

Nitrogen is the one of the most important nutrients for the living cell, and its availability is often the growth-limiting factor. All organisms have evolved highly effective but complicated regulatory systems for nitrogen acquisition and utilization. For most bacteria, this system is termed the general nitrogen regulation (Ntr) system. The Ntr system has been most intensively studied in Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and the nitrogen-fixing bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae, where it controls the transcription of many genes involved in nitrogen fixation and assimilation, such as glnA (encoding glutamine synthetase [GS]), amtB (encoding a putative ammonium transporter), glnK (a PII signal transduction protein), and nifA (encoding the transcriptional activator for the other genes involved in nitrogen fixation) (1, 3, 40, 45, 46).

The Ntr system involves a number of proteins, including GlnD, NtrB, NtrC, and PII. GlnD is a bifunctional uridylyltransferase/uridylyl-removing enzyme (UTase/UR, gene product of glnD) that regulates PII proteins by uridylylation or deuridylylation. GlnD is thought to be a primary sensor of intracellular nitrogen status, determined by the level of glutamine in the cell (22, 25, 26). PII proteins have been characterized in some detail in E. coli and K. pneumoniae, in which two PII homologs, GlnB and GlnK, have been identified (23, 56). Both PII proteins can interact with NtrB to regulate NtrC activity (4). NtrB and NtrC (the gene products of ntrB and ntrC) are two-component regulators. NtrB is a histidine kinase that phosphorylates NtrC under nitrogen-limiting conditions and also can act as a phosphatase to dephosphorylate NtrC under nitrogen-excess conditions (41). Under nitrogen-excess conditions, both GlnB and GlnK are deuridylylated by GlnD, so that they can interact with NtrB to stimulate its phosphatase activity, resulting in the dephosphorylation of NtrC. However, under nitrogen-limiting conditions, both PII proteins become uridylylated, and this uridylylation prevents their interaction with NtrB, so that NtrB is dominated by its kinase activity to phosphorylate NtrC (24). The kinase and phosphatase activities of NtrB are also regulated by PII in response to the level of α-ketoglutarate in the cell (30). The phosphorylated form of NtrC acts as a transcriptional activator of nifA, glnA, and other operons involved in nitrogen fixation and assimilation. PII, together with adenylyltransferase (encoded by glnE), also controls GS activity by reversible adenylylation (26, 53).

The PII proteins also affect a variety of other physiological processes with some general relationship to central nitrogen metabolism. Often the precise role of the PII homolog depends on its modification state and is therefore a function of GlnD activity. Some of the specific processes that are addressed in this report are briefly introduced below.

Besides the transcriptional regulation of nifA expression by the ntr system, NifA activity is regulated in K. pneumoniae and Azotobacter vinelandii (6, 37). Another nif-specific protein NifL, which is cotranscribed with NifA, interacts with NifA directly to inhibit its activity in response to NH4+ and oxygen (6, 18, 35, 38, 39). GlnK, but not GlnB, is involved in the relief of NifL inhibition of NifA in K. pneumoniae under N2-fixing conditions (17, 23).

In the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum, the transcriptional regulation of nif expression is less well studied. Three PII homologs, named GlnB, GlnK, and GlnJ, have been identified in R. rubrum (28, 61). Although the amino acid sequences of these three homologs are very similar, they showed both distinct and overlapping functions in the cell, including NifA activation, modulation of posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase, GS modification, and cell growth (61).

Previous studies showed that NtrBC are not essential for nif expression in R. rubrum, indicating that R. rubrum has a different regulatory mechanism for nif expression from that seen in K. pneumoniae (59). In R. rubrum, transcription of nifA is not regulated but NifA activity is tightly controlled in response to NH4+ (62). That regulation probably occurs through the direct interaction between NifA and the uridylylated form of GlnB, which is required for the activation of NifA activity under NH4+-limiting conditions (61, 62, 64). Neither GlnK nor GlnJ can replace GlnB to activate NifA (61, 64).

The nitrogenase activity of R. rubrum is also regulated in response to exogenous NH4+ or to energy limitation through the activities of the Ntr products. This process involves reversible mono-ADP-ribosylation of dinitrogenase reductase and is catalyzed by two different enzymes (36, 63). Under NH4+ excess or energy-limiting conditions, dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyltransferase (referred to as DRAT, the gene product of draT) carries out the transfer of the ADP-ribose from NAD to the Arg-101 residue of dinitrogenase reductase, resulting in inactivation of that enzyme. The ADP-ribose group attached to dinitrogenase reductase can be removed by another enzyme, dinitrogenase reductase-activating glycohydrolase (referred to as DRAG, the gene product of draG), thus restoring nitrogenase activity. The regulation of the ADP-ribosylation of dinitrogenase reductase is effected through the posttranslational regulation of both DRAT and DRAG activities, apparently through interaction with GlnB and GlnJ (61). Under N2-fixing conditions, DRAG is active and DRAT is inactive, but after addition of NH4+ excess or removal of an energy source, DRAG becomes inactive and DRAT becomes transiently active (63). The presence of either GlnB or GlnJ provides approximately normal posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase activity (61).

To better understand the role of the uridylylation of the PII proteins in the Ntr regulatory system and specifically on nitrogen fixation, we have constructed insertion and deletion mutations in glnD and characterized the roles of GlnD in the regulation of NifA activity, the regulation of NtrB- and NtrC-controlled gene expression, and the regulation of DRAT and DRAG activities. Surprisingly, different levels of UTase activity are required for proper regulation of these three different regulatory systems, which suggests that the analysis of the roles of GlnD in other organisms might be rather more difficult to analyze than has been generally appreciated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The various media have been defined elsewhere; SMN is a rich medium, MN is a minimal medium with NH4 as the sole nitrogen source, MG is similar except that glutamate serves as a relatively poor sole nitrogen source, and MN− lacks all added nitrogen sources (13, 33, 61). Antibiotics were used as necessary at the levels described previously (62).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype and description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| R. rubrum | ||

| UR2 | Wild type; Smr | 31 |

| UR381 | ΔntrBC1::Kan mutant, Smr Kmr | 59 |

| UR687 | glnA2 (GS-Y398F) mutant; Smr Kmr | 62 |

| UR717 | ΔglnB3 (in-frame deletion) mutant, Smr | 62 |

| UR757 | ΔglnB3 ΔglnK1::aacC1 double mutant, Smr Gmr | 61 |

| UR806 | ΔglnJ1::Kan mutant, Smr Kmr | 61 |

| UR810 | ΔglnK1::aacC1 ΔglnJ1::Kan double mutant, Smr Gmr Kmr | 61 |

| UR816 | ΔglnB3 ΔglnJ1::Kan double mutant, with an unknown suppressor mutation conferring fast growth, Smr Kmr | 61 |

| UR902 | Transconjugant of UR757 (glnBK mutant) with pUX510; Smr Gmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1111 | glnD1::aacC1 (opposite orientation); Smr Gmr | This report |

| UR1119 | glnD2::aacC1 (same orientation); Smr Gmr | This report |

| UR1120 | Transconjugant of UR1111 with pCK3; Smr Gmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1144 | Transconjugant of UR1111 with pUX1097; Smr Gmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1155 | Transconjugant of UR1111 with pUX1102; Smr Gmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1156 | Transconjugant of UR1111 with pUX1103; Smr Gmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1157 | Transconjugant of UR1111 with pUX1105; Smr Gmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1242 | Transconjugant of UR1111 with pUX1224; Smr Gmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1325 | ΔglnD3::aacC1 (opposite orientation); Smr Gmr | This report |

| UR1326 | ΔglnD4::aacC1 (same orientation); Smr Gmr | This report |

| UR1330 | Transconjugant of UR1325 with pCK3; Smr Gmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1331 | Transconjugant of UR1326 with pCK3; Smr Gmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1332 | Transconjugant of UR1325 with pUX1224; Smr Gmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1333 | Transconjugant of UR1326 with pUX1224; Smr Gmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1377 | Transconjugant of UR2 with pUX510; Smr Tcr | This report |

| UR1379 | Transconjugant of UR1325 with pUX510; Smr Gmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1387 | pUX1385 was integrated into the chromosome of UR1325, Smr Gmr Kmr | This report |

| UR1388 | pUX1236 was integrated into the chromosome of UR1325, Smr Gmr Kmr | This report |

| UR1389 | pUX1385 was integrated into the chromosome of UR1326, Smr Gmr Kmr | This report |

| UR1390 | pUX1236 was integrated into the chromosome of UR1326, Smr Gmr Kmr | This report |

| UR1391 | ΔglnD3::aacC1 draG4::Kan mutant, Smr Gmr Kmr | This report |

| UR1392 | ΔglnD4::aacC1 draG4::Kan mutant, Smr Gmr Kmr | This report |

| UR1393 | Transconjugant of UR1387 with pUX510; Smr Gmr Kmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1394 | Transconjugant of UR1388 with pUX510; Smr Gmr Kmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1395 | Transconjugant of UR1389 with pUX510; Smr Gmr Kmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1396 | Transconjugant of UR1390 with pUX510; Smr Gmr Kmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1401 | Transconjugant of UR1391 with pCK3; Smr Gmr Kmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1402 | Transconjugant of UR1392 with pCK3; Smr Gmr Kmr Tcr | This report |

| UR1422 | ΔglnD3::aacC1 glnA2 (GS-Y398F) mutant; Smr Kmr | This report |

| UR1423 | ΔglnD4::aacC1 glnA2 (GS-Y398F) mutant; Smr Kmr | This report |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUX19 | Suicide vector for R. rubrum; Kmr | D. P. Lies and G. P. Robertsa |

| pUCGM | pUC19 derivative containing aacC1 (encoding Gmr gene), Apr Gmr | 50 |

| pMAL-c2 | A cloning vector for recombinant protein expression and purification that creates fusions to the maltose-binding protein | New England Biolabs |

| pSUP202 | Suicide vector for R. rubrum; Apr Cmr Tcr | 52 |

| pRK404 | Broad-host-range plasmid for R. rubrum; Tcr | 11 |

| pCK3 | pRK290 derivative containing K. pneumoniae nifA; Tcr | 32 |

| pJHL201 | pSUP202 derivative containing draG4::Kan; Apr Cmr Kmr | 34 |

| pYPZ148 | 3.3-kb fragment containing R. rubrum nifH′ and draTGB was cloned in pUC19; Apr | 60 |

| pUX280 | 6.6-kb fragment containing R. rubrum glnJ amtB1 cloned into pBSKS(−); Apr | This report |

| pUX430 | malE-glnJ fusion; glnJ was cloned into pMAL-c2; Apr | This report |

| pUX431 | PnifH-glnJ fusion cloned into pRK404; Tcr | This report |

| pUX510 | Kp nifA (4-kb HindIII fragment) from pCK3 was inserted into pUX431; Tcr | This report |

| pUX1000 | 3-kb R. rubrum glnD (BamHI-HindIII) cloned into pUX19; Kmr | This report |

| pUX1001 | glnD1::aacC1; aacC1(Gmr) from pUCGM inserted at NruI site of glnD in pUX1000, with aacC1 transcribed opposite to glnD; Kmr Gmr | This report |

| pUX1047 | glnD2::aacC1; aacC1(Gmr) from pUCGM inserted at NruI site of glnD in pUX1000, with aacC1 transcribed in the same direction as glnD; Kmr Gmr | This report |

| pUX1097 | R. rubrum glnD (BamHI-HindIII) from pUX1000 cloned into pRK404; Tcr | This report |

| pUX1098 | In-frame deletion of the 5′ region of glnD (glnD5) from pUX1000; Kmr | This report |

| pUX1102 | glnD1::aacC1 from pUX1001 cloned into pRK404; Tcr | This report |

| pUX1103 | glnD2::aacC1 from pUX1047 cloned into pRK404; Tcr | This report |

| pUX1105 | In-frame deletion of the 5′ region of glnD (glnD5) cloned into pRK404; Tcr | This report |

| pUX1224 | 5′ region of glnD′ (glnD6) cloned into pRK404; Tcr | This report |

| pUX1235 | 5 kb of R. rubrum glnD (BamHI-HindIII) was cloned in pSUP202; Apr Cmr | This report |

| pUX1236 | 5 kb of R. rubrum glnD (BamHI-HindIII) was cloned in pUX19; Kmr | This report |

| pUX1237 | About 1.2 kb upstream region of glnD was cloned in to pUX1235 and replaced about 2.5 kb of R. rubrum glnD (BamHI-BglII deletion); Apr Cmr | This report |

| pUX1295 | ΔglnD3::aacC1; aacC1 (Gmr) inserted into BglII site of glnD in pUX1237, with aacC1 transcribed opposite to glnD; Apr Cmr Gmr | This report |

| pUX1299 | ΔglnD4::aacC1; aacC1 (Gmr) inserted into BglII site of glnD in pUX1237, with aacC1 transcribed in the same direction as glnD; Apr Cmr Gmr | This report |

| pUX1385 | 2.1 kb of the 5′ region of glnD (glnD7) cloned into pUX19; Kmr | This report |

Unpublished data.

Cloning of glnD from R. rubrum.

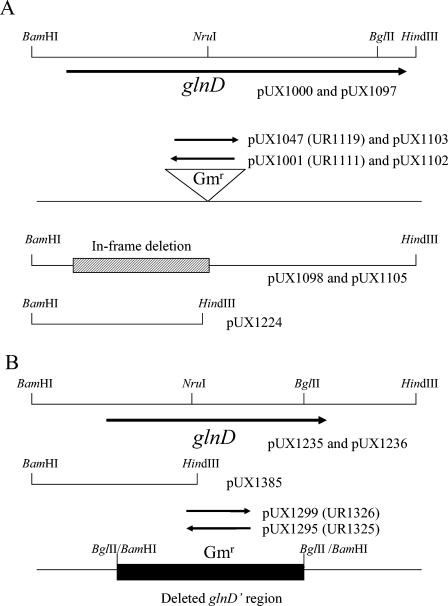

The sequence of the glnD homolog from R. rubrum has been determined by genomic sequencing and is available from the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute web site (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/draft_microbes/rhoru/rhoru.home.html). R. rubrum glnD was cloned from genomic DNA of UR2 (wild type) with amplification by Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and oligonucleotide primers that also created BamHI and HindIII sites at the ends of a 3-kb fragment. After digestion with BamHI and HindIII, the amplified DNA fragment was cloned into pUX19, yielding pUX1000 (Fig. 1A), which was confirmed by sequencing. pUX19 is a derivative of pUK21 (57) with a pMB1-derived replicon, oriV (the origin of replication) and oriT (the origin of conjugative transfer), as well as kan (Kmr) as a selection marker (D. P. Lies and G. P. Roberts, unpublished data). It is a mobilizable and suicide plasmid for R. rubrum.

FIG. 1.

Physical map of plasmids to construct glnD insertion mutants (A) and glnD deletion mutants (B), as well as for complementation experiments. R. rubrum strains are listed in parentheses. The orientation of accC1 (Gmr) is indicated by arrows. As explained in the text, the plasmids in panels A and B have different extents of flanking chromosomal material, although similar BamHI and HindIII linkers were cloned at the ends. For the BglII/-BamHI sites at the ends of the glnD deletion with Gmr insertion, the right-hand site represents the original BglII in glnD while the left-hand BglII site was created near the 5′ end of the gene, as described in Materials and Methods.

Construction of R. rubrum glnD mutants.

To construct the glnD insertion mutants, pUX1000 was digested with NruI, which cuts glnD at codon 393, and a Gmr cartridge from pUCGM (50) was inserted in either orientation, yielding pUX1001 and pUX1047 (Fig. 1A). These plasmids were transformed into E. coli S17-1 (52) and then conjugated into R. rubrum by a method described previously (34). Smr Gmr R. rubrum colonies were selected and replica-printed to identify Kms colonies resulting from a double-crossover recombination event. In UR1111 (glnD1::aacC1), glnD and aacC1 are transcribed in opposite directions, while in UR1119 (glnD2::aacC1), they are transcribed in the same direction (Fig. 1A).

To construct the glnD deletion mutants, a longer chromosomal fragment (∼5 kb) was amplified with another pair of oligonucleotides with BamHI and HindIII at the ends, digested with these enzymes, and then cloned into pSUP202 (52), yielding pUX1235 (Fig. 1B). pUX1235 was digested with BamHI and BglII, so that only 200 bp of the 3′ region of glnD remained. To amplify the region 5′ of glnD, a primer with a BglII site and a small portion of the 5′ region of glnD was used together with another primer with a BamHI site noted above, which allowed the amplification of a 1.1-kb fragment with pUX1235 as the template. The fragment was digested with BamHI and BglII and ligated with pUX1235 (digested with BamHI and BglII as noted above), yielding pUX1237, which has a 2.5-kb internal region of glnD deleted. A Gmr cartridge was inserted into the BglII site of pUX1237, yielding pUX1295 and pUX1299, depending on the orientation of the cartridge (Fig. 1B). These plasmids were transformed into E. coli S17-1 and then conjugated into R. rubrum UR2. Smr Gmr R. rubrum colonies were selected and replica-printed to identify Cms colonies. Two glnD deletion mutants, designated UR1325 and UR1326, were obtained (Fig. 1B).

Construction of ΔglnD draG mutants.

A draG4::Kan insertion mutation on a mobilizable suicide plasmid was constructed previously and termed pJHL201 (34). This plasmid was conjugated into R. rubrum ΔglnD mutants (UR1325 and UR1326), and Nxr Gmr Kmr colonies were selected. Cms colonies (Cmr is encoded by pSUP202), resulting from double-crossover recombination events, were screened. Two ΔglnD draG mutants, designated UR1391 (from UR1325) and UR1392 (from UR1326), were obtained.

Construction of ΔglnD glnA2 (GS-Y398) mutants.

Similar to the construction of ΔglnD mutants, pUX1295 and pUX1299 (ΔglnD3::accC1 and ΔglnD4::accC1, with different orientations of the Gmr cartridge) were transferred into R. rubrum UR687 (glnA2, GS-Y398F) (62). Nxr Kmr Gmr R. rubrum colonies were selected and replica-printed to identify Cms colonies. Two ΔglnD glnA2 mutants, designated UR1422 and UR1423, were obtained.

Construction of truncated glnD alleles for complementation experiments.

To construct a plasmid encoding only the C-terminal domain of GlnD, two primers were chosen that amplified the 5′ region to the initial Met codon and the 3′ region from Met-442 of glnD. These two primers had complementary sequences to each other, such that amplification with pUX1000 as the template yielded a 5.5-kb product that could be self-ligated and then transformed into E. coli DH-5α, yielding pUX1098. This plasmid contained an in-frame deletion of glnD from residues 2 to 442 (Fig. 1A). A BamHI-HindIII fragment containing the deletion was subcloned into pRK404 (11), yielding pUX1105, and the allele was termed glnD5.

A plasmid carrying only the N terminus of GlnD was constructed by amplification with a primer that positioned a stop codon near the NruI site and added a HindIII site. With another primer at an upstream region of glnD with the BamHI site noted above, a truncated glnD fragment was amplified with pUX1000 as the template. After PCR, a 1.4-kb BamHI-HindIII fragment was created by digestion and cloned into pRK404, yielding pUX1224. This plasmid contains about 1.17 kb of glnD, and the allele was termed glnD6 (Fig. 1A).

As a control, the entire glnD region from pUX1000 was also cloned into pRK404, yielding pUX1097. Two truncated glnD alleles, with the Gmr cassette in either orientation, were produced from pUX1001 and pUX1047 by digestion with BamHI and HindIII and then subcloned into pRK404, yielding pUX1102 and pUX1103, respectively (Fig. 1A). These plasmids were transferred into R. rubrum glnD mutants by the triparental mating method described previously (16).

To integrate a single-copy wild-type or truncated glnD allele into the R. rubrum chromosome, a BamHI-HindIII fragment containing wild-type glnD from pUX1235 was cloned into pUX19, yielding pUX1236. Similarly, glnD' with only the N-terminal region was amplified by PCR and cloned into pUX19, yielding pUX1385 (Fig. 1B). These plasmids were transformed into E. coli S17-1 and then conjugated with R. rubrum glnD mutants (UR1325 and UR1326). Smr Kmr Gmr R. rubrum colonies were selected in which the entire plasmid had integrated into the chromosome through a single-crossover recombination event.

Construction of plasmids to overexpress R. rubrum glnJ from the R. rubrum nifH promoter.

To generate a PnifH-glnJ fusion, one set of primers was used to amplify the R. rubrum nifH promoter region with pYPZ148 (60) as the template. Another set of primers was used to amplify glnJ with pUX280 as the template. The two PCR products were recovered from agarose gels with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.). Because the primers were designed to have a 34-base complementary sequence, these two PCR products were annealed to generate a full-length of PnifH-glnJ fusion by another PCR amplification with primers at the two ends with either a BamHI or HindIII site. A 1-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment was created by digestion and cloned into pRK404, yielding pUX431, which was confirmed by sequencing.

To overexpress GlnJ in a glnD background, a 4-kb HindIII fragment of K. pneumoniae nifA from pCK3 (32) was inserted into pUX431, yielding pUX510. Unlike NifA from R. rubrum, K. pneumoniae NifA does not require GlnB-UMP for its activation (62), so that it allows the overexpression of R. rubrum glnJ from the nifH promoter in a glnD mutant background. This plasmid was transferred into different R. rubrum backgrounds by triparental mating (16).

In vivo nitrogenase activity assay.

R. rubrum was grown in rich SMN medium and then inoculated into MG or N-free MN− medium for derepression of nitrogenase activity under illumination. The whole-cell nitrogenase activity assay and darkness/NH4Cl treatments have been described previously (58).

Generate of GlnJ antiserum and immunoblotting procedures.

To construct the MalE-GlnJ fusion protein, primers were used to PCR amplify R. rubrum glnJ with pUX280 as the template. After digestion with EcoRI and HindIII, a 0.5-kb fragment was cloned into pMAL-C2 (New England Biolabs Inc., Beverly, Mass.), which was digested with the same restriction enzymes, yielding pUX430. All of GlnJ except the first two amino acids were fused with MalE.

For generation of R. rubrum GlnJ antiserum, the E. coli strain carrying pUX430 was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyraneside (IPTG), harvested, and broken by sonication. The fusion protein was purified on a 10-ml amylose resin column as specified by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs Inc.). A rabbit was immunized by intradermal injection of 1 mg of MalE-GlnJ fusion protein with complete Freund's adjuvant followed by two boosts. The serum was collected at 6 weeks after the final boost.

A trichloroacetic acid precipitation method was used to extract protein, and a low-cross-linker (ratio of acrylamide to bisacrylamide, 172:1) Tricine gel was used to separate modified and unmodified GlnJ (48). Proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) were electrophoretically transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, immunoblotted with polyclonal antibody against GlnJ, and visualized with horseradish peroxidase color detection reagents (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). The modification of GS was monitored with a polyclonal antibody against R. rubrum GS.

Other DNA techniques.

DNA manipulations were performed by standard methods. DNA sequences were determined with the Big Dye Terminator v. 3.1 cycle-sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and analyzed with software from DNASTAR (Madison, Wis.). A MasterPure genomic DNA purification kit from Epicentre (Madison, Wis.) was used for total-DNA isolation from R. rubrum, with a few minor modifications as described previously (62).

RESULTS

Some glnD insertion mutants have a non-null phenotype.

As described in Materials and Methods, a 3-kb PCR product containing R. rubrum glnD was cloned into pUX19 and sequenced. The predicted R. rubrum GlnD has 936 amino acids with a molecular mass of about 150 kDa and shows high similarity to GlnD from Azospirillum brasilense (55% identity) and Sinorhizobium meliloti (45% identity).

Two glnD insertion mutants, designated UR1111 and UR1119, were constructed by replacement of the wild-type chromosomal allele. UR1111 has glnD1::aacC1 (Gmr), where aacC1 is transcribed in the opposite orientation from glnD, while UR1119 (glnD2::aacC1) has both transcribed in the same orientation (Fig. 1A). The two strains were examined for nitrogenase activity under depressing conditions, since GlnB-UMP is necessary for activation of NifA, the positive activator of nif expression, and GlnD is necessary for that uridylylation (62). UR1111 showed negligible nitrogenase activity, consistent with an absence of the UTase activity that is necessary for the activation of NifA. Surprisingly UR1119 had nitrogenase activity similar to that seen in the wild type (UR2) (Table 2), indicating the presence of significant amounts of UTase activity in that strain.

TABLE 2.

Nitrogenase activity in R. rubrum glnD mutants

| Strain | Chromosomal genotype | Plasmids and genes | Nitrogenase activitya (units) |

|---|---|---|---|

| UR2 | Wild type | None | 800 |

| UR1111 | glnD1::aacC1 (opposite orientation) | None | <20 |

| UR1119 | glnD2::aacC1 (same orientation) | None | 750 |

| UR1120 | glnD1::aacC1 (opposite) | pCK3 (K. pneumoniae nifA) | 800 |

| UR1144 | glnD1::aacC1 (opposite) | pUX1097 (glnD+) | 600 |

| UR1155 | glnD1::aacC1 (opposite) | pUX1102 (glnD1::aacC1) | 400 |

| UR1156 | glnD1::aacC1 (opposite) | pUX1103 (glnD2::aacC1) | 420 |

| UR1157 | glnD1::aacC1 (opposite) | pUX1105 (3′ region of glnD′) | <20 |

| UR1242 | glnD1::aacC1 (opposite) | pUX1224 (5′ region of glnD′) | 800 |

| UR1325 | ΔglnD3::aacC1 (opposite orientation) | None | <20 |

| UR1326 | ΔglnD4::aacC1 (same orientation) | None | <20 |

| UR1330 | ΔglnD3::aacC1 (opposite) | pCK3 (K. pneumoniae nifA) | 620 |

| UR1331 | ΔglnD4::aacC1 (same) | pCK3 (K. pneumoniae nifA) | 650 |

| UR1332 | ΔglnD3::aacC1 (opposite) | pUX1224 (5′ region of glnD) | 700 |

| UR1333 | ΔglnD4::aacC1 (same) | pUX1224 (5′ region of glnD) | 670 |

Nitrogenase activity was derepressed in MG under illumination. Each unit of nitrogenase activity is expressed as nanomoles of ethylene produced per hour per milliliter of cells at an optical density at 600 nm of 1. Each activity value is from at least 10 replicate assays from different individually grown cultures. The standard deviation is about 10 to 15%.

To verify that the presence or absence of nitrogenase activity reflected uridylylation of GlnB, we introduced K. pneumoniae NifA into the UR1111 background and examined nitrogenase activity. We have previously shown that the K. pneumoniae NifA activity does not depend on uridylylation of GlnB in R. rubrum (62). The presence of nitrogenase activity in this strain (UR1120) indicated that the effect of the glnD mutation in UR1111 was to eliminate the UTase activity (Table 2). This result became easier to understand when we realized that a Pfam search (http://pfam.wustl.edu/index.html) (5) had predicted that E. coli GlnD would have UTase activity in its N-terminal portion. By analogy, R. rubrum GlnD appears to have its nucleotidyltransferase domain in the vicinity of residues 105 to 184, which probably represents the UTase activity (20). There is also an HD domain, suggested to encode phosphohydrolase activity, located at residues 488 to 610, possibly representing the UR activity (2). The glnD insertion mutants mentioned above have aacC1 (Gmr) inserted at codon 393.

Given that the predicted function of UTase is located in the N-terminal region of GlnD, the different phenotypes seen in these glD insertion mutants were probably due to differential accumulation of the protein with UTase activity. The difference in detected function might be due either to interference by opposite transcription of inserted aacC1 or to differential protein stability resulting from the different C-terminal ends. To confirm the location of UTase activity, three plasmids were constructed as described in Materials and Methods for complementation experiments. In pUX1105, the region encoding residues 2 to 442 was deleted, so that only the C-terminal region of GlnD (residues 443 to 936) was produced from its normal promoter. Plasmid pUX1224 produces only the N-terminal region (resides 1 to 393) of GlnD, and a control plasmid (pUX1097) produces the wild-type protein (Fig. 1A). All of these plasmids were transferred into UR1111 (glnD1::aacC1, opposite), yielding UR1144, UR1157, and UR1242, respectively. All plasmids have a broad host range and are stable in R. rubrum at about 10 copies per cell.

As expected, pUX1097 (glnD+, UR1144) restored nitrogenase activity, as did the strain producing the N-terminal region of GlnD (UR1242), but UR1157 (producing the C-terminal region of GlnD) did not (Table 2). This indicates that UTase activity is located in the N-terminal region and is sufficient for NifA activation when expressed from a multicopy plasmid. The two orientations of glnD insertions, which gave the initial conflicting results, were also examined on plasmids. Somewhat surprisingly, both strains (UR1155 and UR1156) had moderate levels of nitrogenase activity regardless of the orientation of the accC1 insertion, suggesting that the multicopy expression of these truncated GlnD fragments allows sufficient UTase activity for the phenotype. This result and others noted below suggest that modest differences in GlnD activity can have dramatic and differential effects on different regulatory processes, apparently depending on the precise requirements of the uridylylated substrate protein for a wild-type phenotype.

Construction and characterization of mutants with complete deletions of glnD.

As a critical control, we created glnD deletions lacking virtually the entire coding region (residues 23 to 864) and with an aacC1 insertion in either orientation (UR1325 and UR1326 in Fig. 1B). Unlike the case for A. vinelandii and some other bacteria, the R. rubrum glnD deletion mutations are not lethal, and the strains grow reasonably well in both rich medium (SMN) and minimal malate-glutamate medium (MG, where glutamate is the sole nitrogen source). However, there were growth defects on minimal medium with no added nitrogen source (MN−) and with NH4+ as the sole nitrogen source (MN). As discussed below, we think that these defects might be caused by decreased GS activity.

Both deletion strains lacked nitrogenase activity, but activity was restored by the presence of the N-terminal region of GlnD (UR1332 and UR1333) or the presence of the GlnD-independent NifA of K. pneumoniae (UR1330 and UR1331) (Tables 2). These results reinforce the concept that GlnD is essential for R. rubrum NifA activity and that the N-terminal region of GlnD is sufficient for this function.

Darkness and NH4+ response in glnD mutants.

In R. rubrum, nitrogenase activity is tightly regulated by the DRAT-DRAG regulatory system in response to exogenous NH4+ or to energy limitation due to a shift to darkness (31). Several lines of evidence have shown that GlnB and GlnJ are involved in this regulation (61), and we wished to determine the impact of the glnD mutation, which would prevent the uridylylation of both GlnB and GlnJ. As shown in Table 3, UR2 (wild type) lost about 90% of its activity 60 min after a shift to darkness, and the activity recovered completely 10 min after a return to light. To assay the posttranslational effects of DRAT and DRAG on nitrogenase activity, nif gene expression is necessary, therefore, ΔglnD mutants carrying K. pneumoniae nifA (UR1330 and UR1331) were used. These strains had a fairly normal loss of nitrogenase activity in response to darkness, which implies that DRAT is properly regulated. However, these strains failed to recover nitrogenase activity after a return to light, which indicates that DRAG is unable to become activated normally. This suggests that DRAG activation requires the uridylylated form of either GlnB or GlnJ, since these are lacking in the glnD mutant.

TABLE 3.

Darkness response in R. rubrum wild-type and glnD mutant strains

| Strain | Chromosomal genotype and gene on plasmid | Nitrogenase activity (units) before and after dark-light shiftsa

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 60 min dark | 10 min light | ||

| UR2 | Wild type | 800 | 90 (11%) | 720 (90%) |

| UR1120 | glnD1::aacC1 mutant with Kp nifA (pCK3) | 800 | 140 (18%) | 720 (90%) |

| UR1330 | ΔglnD3::aacC1 mutant with Kp nifA (pCK3) | 620c | 120 (20%) | 170 (28%) |

| UR1331 | ΔglnD4::aacC1 mutant with Kp nifA (pCK3) | 650c | 120 (18%) | 160 (25%) |

| UR1332 | ΔglnD3::aacC1 with 5′ region of glnD (pUX1224) | 700 | 175 (25%) | 770 (110%) |

| UR1333 | ΔglnD4::aacC1 with 5′ region of glnD (pUX1224) | 670 | 160 (24%) | 710 (106%) |

| UR1387 | ΔglnD4::aacC1 with integration of 5′ region of glnD | 360 | 65 (18%) | 365 (101%) |

| UR1388 | ΔglnD4::aacC1 with integration of glnD+ | 700 | 65 (9%) | 665 (95%) |

| UR1389 | ΔglnD3::aacC1 with integration of 5′ region of glnD | 350 | 65 (19%) | 370 (106%) |

| UR1390 | ΔglnD3::aacC1 with integration of glnD+ | 720 | 60 (8%) | 770 (107%) |

| UR1401 | ΔglnD3::aacC1 draG4 with Kp nifA (pCK3) | 140 | 30 (21%) | 55 (39%) |

| UR1402 | ΔglnD4::aacC1 draG4 with Kp nifA (pCK3) | 150 | 35 (23%) | 55 (37%) |

Nitrogenase activity was derepressed in MG medium under illumination and assayed before the shift to the dark (initial), 60 min after cells were shifted to the dark, and 10 min after cells were returned to light. Each unit of nitrogenase activity is expressed as nanomoles of ethylene produced per hour per milliliter of cells at an optical density at 600 nm of 1. Each activity value is from at least 10 replicate assays from different individually grown cultures. The standard deviation is about 10 to 15%. The values in parentheses are the percentages of the initial nitrogenase activity remaining after the shift to darkness or reillumination. UR1330 and UR1331 grew significantly more slowly than did other strains in MG, so that they had lower total nitrogenase activity, even though the initial specific activity was very similar to that of wild-type and other strains.

To determine if the level of GlnD activity required for DRAT and DRAG regulation is similar to that for NifA regulation, the darkness-light response in glnD deletion mutants producing the truncated N-terminal GlnD (glnD5) either from a multicopy plasmid (UR1332 and UR1333) or from the chromosome (UR1387 and UR1389) was also monitored. A lower nitrogenase activity was seen in UR1387 and UR1389 (with a single copy of glnD5) than in UR1332 and UR1333 (with multicopy glnD5) (Table 3). All of these strains showed a normal response to darkness and light shifts, but a slightly higher residual nitrogenase activity was seen in these strains in darkness than that seen in the wild type and glnD deletion mutants with glnD+ integrated into the chromosome (UR1388 and UR1390) (Table 3). These results indicate that this truncated N-terminal GlnD can support both NifA activation and normal DRAT-DRAG regulation. Interestingly, the glnD1::aacC1 insertion (opposite orientation), which failed to allow nif expression in the original analysis, was able to support a normal response to darkness and light shifts when nifA of K. pneumoniae was supplied to allow nif expression (UR1120 in Table 3). The fact that a single copy of glnD1::aacC1 had sufficient UTase activity for DRAG activation, but not for NifA activation, implies a hierarchy of effects of the levels of GlnD on the different regulatory systems, as discussed below.

Darkness response in glnD draG double mutants.

The failure of a glnD mutant to recover nitrogenase activity might reflect a failure to properly activate DRAG or to properly inactivate DRAT. To distinguish between these possibilities, glnD draG double mutants were constructed and K. pneumoniae nifA was transferred into them to support nitrogenase activity. We were able to study DRAT regulation in these strains without interference by DRAG. As shown in Table 3, UR1401 and UR1402 showed a low initial nitrogenase activity but responded normally to darkness, indicating normal activation of DRAT. Because they lack DRAG, these strains failed to recover nitrogenase activity after a return to light. The relatively low nitrogenase activity in these mutants before the shift to darkness indicates that there is a very low level of DRAT activity even under nitrogen starvation conditions. This low level of DRAT activity demonstrates an effect of the glnD mutation on the regulation of DRAT, since DRAT activity is completely absent in the wild type under the same conditions. However, this trace DRAT activity is detectable only because of the absence of DRAG activity in these strains, and we doubt that this DRAT activity would be detected otherwise. We therefore think that the main effect of glnD alleles on the DRAT-DRAG system must be due to altered DRAG activation.

NH4+ response and the GS modification in glnD deletion mutants.

Unlike the case for A. vinelandii and some other organisms, R. rubrum glnD mutations are not lethal and the strains grow well in rich SMN and nitrogen-limiting MG. However, when we tried to grow UR1330 and UR1331 (ΔglnD mutants with K. pneumoniae nifA) in medium completely lacking fixed nitrogen (MN−), they were unable to grow. This is surprising, because these strains had substantial nitrogenase activity when derepressed in MG medium, where glutamate serves as a poor nitrogen source (Table 2). We assume this failure to grow in MN− is due to a defect in NH4+ assimilation and is consistent with the observation that these mutants also grew poorly in MN, where NH4+ is the sole nitrogen source. Although UR1332 and UR1333 (ΔglnD mutants with the N terminus of GlnD) had low nitrogenase activity, they were able to grow in MN−, albeit slowly, suggesting that a low level of UTase activity is sufficient. These strains were able to respond to NH4+ rapidly, similar to the response of UR2 (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

NH4+ response in R. rubrum glnD mutants

| Strain | Chromosomal genotype | Plasmid | Nitrogenase activity (units) before and after NH4Cl additiona

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 10 min after | 40 min after | |||

| UR2 | Wild type | None | 300 | <10 | <10 |

| UR1332 | ΔglnD3::aacC1 (opposite) | pUX1224 (5′ region of glnD) | 130 | <10 | <10 |

| UR1333 | ΔglnD4::aacC1 (same) | pUX1224 | 160 | <10 | <10 |

Nitrogenase activity was derepressed in MN− under illumination and assayed before NH4Cl addition (initial) and 10 min and 40 min after NH4Cl (10 mM) addition. Each unit of nitrogenase activity is expressed as nanomoles of ethylene produced per hour per milliliter of cells at an optical density at 600 nm of 1. Each activity value is from at least 10 replicate assays from different individually grown cultures. The standard deviation is about 10 to 15%.

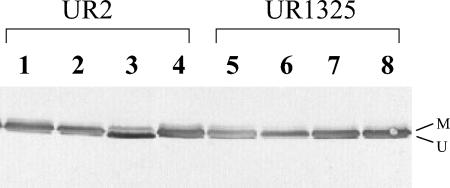

In E. coli, GS activity is reversibly regulated by adenylylation in response to NH4+ (51). This regulation is itself performed by ATase, which is in turn regulated by the action of GlnD on the different forms of PII in the cell (26, 53). In R. rubrum, PII proteins can be modified and unmodified in response to nitrogen status and unmodified PII can stimulate the adenylylation of GS (27, 29). The centrality of GS activity in nitrogen utilization made it a reasonable hypothesis that effects of perturbation of GlnD activity might simply reflect the indirect role of that enzyme in regulating GS activity. In this case, GS activity might be expected to correlate with cell growth, and so we examined the effect of glnD mutations on the GS modification. Both the wild type and glnD deletion mutants were grown in SMN, MN, and MG, and GS modification was monitored by Western immunoblotting with GS antibody. As seen previously in the wild type, most GS accumulated in the modified form when cells were grown in NH4+-rich media (SMN and MN) and accumulated in the unmodified form when the cells were grown in MG. GS also became modified after addition of NH4+ to the culture (Fig. 2) (62). However, most GS was modified in UR1325 (ΔglnD) under all conditions, even in MG medium. This is consistent with the expected role of GlnD in GS regulation, but there was always a small amount of unmodified GS in the glnD mutant, even in cells grown in MN medium (Fig. 2, lane 6). This suggests that for some unknown reason, GS modification is not complete in R. rubrum glnD mutants, which might be the reason for their nonlethality. As shown in Fig. 2, substantially more unmodified GS was found in the glnD mutant when it was grown in either SMN or MG, and this might be the reason why poor growth was seen only in MN.

FIG. 2.

Western immunoblot of GS in UR2 (wild type) and UR1325 (ΔglnD). UR2 (lanes 1 to 4) and UR1325 (lanes 5 to 8) were grown in SMN (lanes 1 and 5), MN (lanes 2 and 6), or MG (lanes 3 and 7). Lanes 4 and 8 contain samples from MG cultures treated with 10 mM NH4Cl for 90 min. Samples were loaded on low-crosslinker SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibody against R. rubrum GS.

To test if the modification of GS (i.e., low GS activity) might be the reason for the poor growth of glnD mutants in MN, two ΔglnD glnA2 (GS-Y398F) double mutants (UR1422 and UR1423) were constructed. The Y398F substitution alters the site for adenylylation, so that this GS variant remains unmodified and active even in the absence of GlnD. The altered GS did restore the normal growth rate in MN. Unlike the parental glnD mutants, both UR1422 and UR1423 grew well in MN, with a doubling time of approximately 6 h, similar to that seen in the wild type, while doubling times of UR1325 and UR1326 (ΔglnD) in MN are about 10 h. These results strongly suggest that poor growth of glnD mutants correlates with their low levels of GS activity.

GlnJ expression is regulated by NH4+ under the control of the NtrB-NtrC regulatory system and GlnD.

The NtrB-NtrC regulatory system is tightly controlled by the status of PII modification in E. coli (40). However, the NtrB-NtrC system is less well characterized in R. rubrum, although an ntrBC mutant has been examined (59). It was expected that some NtrB-NtrC-regulated gene expression should be altered in R. rubrum glnD mutants.

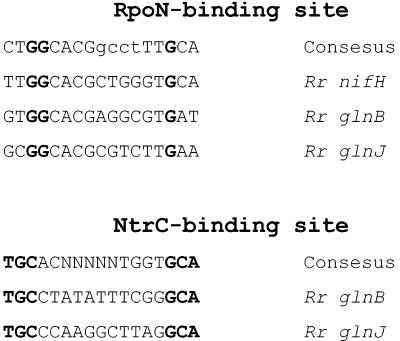

Previous studies indicated that expression of the glnBA operon is probably regulated by the NtrB-NtrC system in R. rubrum (28). An RpoN-dependent promoter and putative NtrC-binding site was found in the region upstream of glnBA, and the expression of glnB is greatly enhanced in the absence of NH4+ (8, 28). However, another σ70-dependent promoter was also found 5′ of glnBA, so that the expression of GlnB and GS is not completely dependent on NtrC (8, 28) and results in some GS accumulation in the presence of NH4+ as seen previously (8, 62).

As shown in Fig. 3, an RpoN-dependent promoter and putative NtrC-binding site exist 5′ of glnJ, suggesting that the expression of glnJ is probably regulated by NtrB and NtrC as well. To investigate the regulation of GlnJ expression, the accumulation of PII proteins was monitored in glnB, glnJ, and glnK mutants under different growth conditions, with antiserum against R. rubrum GlnJ. As shown in Fig. 4, neither GlnB nor GlnK was detected with the GlnJ antibody in glnJ (UR806), glnJK (UR810), or glnBJ (UR816) mutants under these conditions. GlnB does not react well with the GlnJ antibody (data not shown), but the failure to detect GlnK is due its low level in the cell, since it reacts well with GlnJ antibody when GlnK was overexpressed from the glnB promoter (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Sequence alignment of RpoN- and NtrC-binding sites from the promoter regions of nifH, glnB, and glnJ. Consensus bases, thought to be essential for these binding sites, are shown in bold type.

FIG. 4.

Western immunoblots of GlnJ in various PII mutants. Wild-type (UR2), glnB (UR717), glnBK (UR757), glnJ (UR806), glnJK (UR810), and glnBJ (UR816) mutant strains were grown in SMN (lanes 1, 4, 7, 11, 14, and 17), MN (lanes 2, 5, 8, 12, 15, and 18) or MG (lane 3, 6, 9, 13, 16, 19). Lanes 10 and 20 contain GlnJ from crude extract of the overexpression strain (UR902, PnifH-glnJ) as a positive control. Proteins from crude extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibody against R. rubrum GlnJ.

While a large amount of GlnJ accumulated in the wild type (UR2) when it was grown in MG (NH4+-limiting conditions), little GlnJ was detected when it was grown in SMN and MN (NH4+-excess conditions) (Fig. 4). This indicated that the expression of glnJ is tightly regulated by NH4+. It is interesting that the regulation of GlnJ appears to be altered in glnB and glnBK mutants (UR717 and UR757) and that a significant amount of GlnJ was accumulated in the presence of NH4+ (in SMN and MN). This is probably due to the inability of NtrC to be dephosphorylated under NH4+-excess conditions when cells lack GlnB.

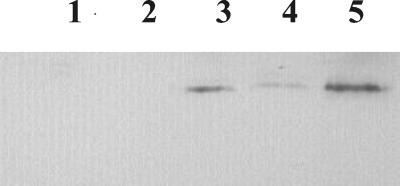

To confirm the regulation of transcription of glnJ by the NtrB-NtrC system, the accumulation of GlnJ was analyzed by Western blots in ntrBC and glnD deletion mutants. As shown in Fig. 5, no GlnJ was detected in either the ntrBC mutant (UR381) or the ΔglnD mutant (UR1325), consistent with the hypothesis that activation of NtrC is required for glnJ transcription and that GlnD is required for that activation. Interestingly, a dramatic decrease of GlnJ accumulation was found in UR1332 (producing the N terminus of GlnD from a multicopy plasmid) and UR1387 (producing the same GlnD fragment from a single-copy allele). In contrast, a normal level of GlnJ was detected in a glnD mutant with single copy of wild-type glnD (UR1388). These results indicate that the full function of the NtrB-NtrC system at this promoter requires a higher level of UTase activity than that needed for NifA activation and DRAT-DRAG regulation.

FIG. 5.

Western immunoblots of GlnJ in ntrBC and glnD mutants. UR381 (ΔntrBC, lane 1), UR1325 (ΔglnD) (lane 2), UR1332 (ΔglnD with the N-terminal region GlnD expressed from a multicopy plasmid) (lane 3), UR1387 (ΔglnD with the N-terminal region GlnD expressed from the chromosome) (lane 4), and UR1388 (expressing glnD+ from the chromosome) (lane 5) were grown in MG. Proteins from crude extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibody against R. rubrum GlnJ.

Uridylylation of GlnJ in glnD mutants.

The poor accumulation of GlnJ in glnD mutants made it impossible to study the uridylylation of GlnJ in these mutants. We therefore constructed a GlnJ overexpression plasmid (pUX510) in which R. rubrum glnJ was expressed from the R. rubrum nifH promoter, which is activated by K. pneumoniae nifA. This plasmid was transferred into wild-type and different mutant backgrounds, and the modification of GlnJ was monitored before and after the addition of NH4Cl. As shown in Fig. 6, UR1377 (wild type) had GlnJ in the modified form before NH4+ addition and in the unmodified form after NH4+ addition. A similar pattern was seen in UR1394 and UR1396 (glnD+ integrated into the chromosome). Because of the loss of GlnD function, GlnJ is always accumulated in the unmodified form in UR1379 (ΔglnD mutant). Surprisingly, UR1393 and UR1395 (expressing the N-truncated glnD from the chromosome) also had unmodified GlnJ, even without NH4+ treatment. This indicates that the UTase activity detected by NifA activation and DRAT-DRAG regulation in these mutants actually represents a rather low level of activity, at least as measured by the modification of GlnJ.

FIG. 6.

Uridylylation of GlnJ in various strains. Crude extracts were prepared from MG cultures before NH4Cl additions (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11) and 90 min after 10 mM NH4Cl additions (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12). Strains include UR1377 (glnD+), UR1379 (ΔglnD), UR1393 and UR1395 (ΔglnD with N-terminal region GlnD integrated in the chromosome), and UR1394 and UR1396 (ΔglnD with glnD+ on the chromosome). All strains contain pUX510, which overproduces GlnJ from the nifH promoter. Proteins were separated on low-crosslinker Tricine gels and immunoblotted with antibody against R. rubrum GlnJ.

DISCUSSION

What explains the range of phenotypes of glnD mutations in different organisms?

In many bacteria, GlnD is a key regulator in the Ntr regulatory system that controls many metabolic pathways involved in nitrogen fixation and assimilation. In E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Klebsiella aerogenes, A. brasilense, and other bacteria, glnD mutants have phenotypes such as failure to grow on nitrate, NH4+, or amino acids as the sole nitrogen source or, in diazotrophs, the inability to fix N2 and highly adenylylated GS (7, 12, 14, 55). In A. vinelandii, Gluconoacetobacter diazotrophicus, Sinorhizobium meliloti, and Rhizobium leguminosarum, some glnD mutants appear to be lethal (10, 44, 47, 49), although there are complications reminiscent of the results we report. In R. leguminosarum bv. viciae, for example, a mutant with an aph insertion at codon 473 is viable but a deletion of codons 230 to 577 is lethal (49). In G. diazotrophicus, gusA::Kan insertions in either orientation at codon 355 are lethal but an aphII interposon insertion at codon 822 is viable (44).

The previously reported results and those presented here suggest that there are several independent issues that must be invoked to explain the differing phenotypes. First, it appears that UTase activity is typically the critical activity and is localized in the N-terminal portion of the protein. The phenotype apparently depends in part on the nature of the mutation and whether the UTase activity is significantly affected, presumably including effects on the stability of the N-terminal fragment. In many of the previous studies, the precise nature of the mutations and their location with respect to the region coding for the UTase activity are unknown. Second, depending on the specific nature of the conditions examined, and therefore the specific level of modified PII required, different levels of UTase activity should be required. This is discussed in greater detail in the following section. Finally, it seems likely that the critical issue in many organisms is the precise level of GS activity that exists in the mutants.

The notion of GS activity being the critical issue in the viability of glnD mutants is consistent with results reported in the literature. For example, although a glnD deletion is lethal in A. vinelandii, a glnA-Y407F glnD double mutant is viable (10). Because the Y407F substitution alters the site of adenylylation, this strongly suggests that inactivation of GS by modification is the key defect in the glnD mutant. Similarly, viable glnD mutants of A. vinelandii were found when the strains bore a second mutation, gln-71, that is probably located in glnE (encoding ATase) (10). This again suggests that modification of GS and its activity might be related to lethality. In R. rubrum, the modification of GS is altered in a glnD mutant, especially under N-limiting conditions. However, there is a detectable level of unmodified GS even under N-excess conditions in the glnD mutant, suggesting that the viability of R. rubrum glnD mutants might reflect an inability to completely inactivate GS for unknown reasons. Consistent with this model, a glnA allele causing a nonmodifiable GS allows a strain with a deletion of glnD to grow normally on MN. Lastly, our inability and that of another group to construct a glnA knockout mutant suggest that such a mutation is lethal in R. rubrum (28, 62). Taken together, these results suggest that the lethality or viability of glnD alleles in many organisms might depend on precise levels of active GS. Given the broad-range function of GlnD and PII, we cannot rule out other direct or indirect effects on other enzymes involved in the NH4+ assimilation, such as GOGAT.

In Streptomyces coelicolor and Corynebacterium glutamicum, PII (GlnK) is modified by adenylylation by GlnD and the adenylyltransferase activity is also located in the N-terminal region of GlnD (19, 54). This is consistent with the observation that GlnE (ATase), responsible for the adenylylation of GS, shares some residues in this region with GlnD and other nucleotidyltransferases (20).

Different levels of GlnD activity are required for NifA activation, DRAT-DRAG regulation, and NtrB-NtrC regulation.

We have demonstrated that a low level of UTase in UR1120 (glnD::aacC1, opposite orientation) is sufficient to support apparently normal regulation of the DRAT-DRAG system (Table 3) but that this level of UTase is unable to support substantial activation of NifA for nif expression (UR1111 in Table 2). For NtrB-NtrC regulation, a higher level of UTase is required, since UR1332 and UR1387 with normal or moderate nitrogenase activity (NifA activation) and normal response to dark and light (DRAT-DRAG regulation) were defective in the normal accumulation of GlnJ (NtrC activation) (Table 3; Fig. 5).

Based on all accumulated information, we assume that the effects of GlnD on all of these regulatory systems are indirect and are actually mediated by its effects on PII. It is well known that NtrC activity is regulated by NtrB through direct interaction with PII in E. coli (24). It is likely that in R. rubrum the NifA activation by GlnB-UMP also occurs through direct protein-protein interaction. Similarly, both GlnB and GlnJ are directly involved in DRAT-DRAG regulation (61). We have also detected the direct interaction between R. rubrum NifA and GlnB and between DRAT and all three PII homologs in the yeast two-hybrid system (Y. Zhang et al., unpublished data). The direct interaction of DRAT and both GlnB and GlnK has also been reported for Rhodobacter capsulatus (43). Why should these processes show very different impacts of altered levels of GlnD and therefore of different PII-UMP species?

The different amounts of PII-UMP required for the proper regulation of different regulatory systems in R. rubrum and other bacteria can be rationalized in several ways. First, GlnD might display a differential preference for some PII species over others for either modification or demodification. If a specific cellular process requires the interaction of a target protein with a specific PII homolog, as we have shown in R. rubrum for NifA activation (64), then the absolute level of only that PII-UMP species would be critical, although other physiological targets might have completely different requirements. Thus, a mutant with altered GlnD activity or accumulation might affect differential PII modification in a physiologically significant way. This is further complicated by the fact that the three PII homologs accumulate to different levels in R. rubrum; GlnJ is the most abundant and GlnK is the least abundant in the cell under nitrogen-limiting conditions (Zhang et al., unpublished).

Second, any single PII-UMP species might have differential affinity for different target proteins. In our case, DRAG may have a higher affinity for GlnB-UMP than does NifA. This is again complicated by the presence of multiple PII species, which might exhibit a differential spectrum of affinities for specific target proteins.

Third, different target proteins might require differential degrees of interaction with PII-UMP for a normal response. For example, proper activation of nif expression by NifA might require only that several NifA proteins be activated by interaction with GlnB-UMP but proper NtrB regulation might require almost complete occupation of the population of NtrB molecules by PII for the normal regulation of NtrC.

Fourth, some target proteins might interact only with PII-UMP while others might interact with both PII-UMP and PII but be activated only by the former. In other words, some receptors might allow a competition between the two forms for binding. In this case, that receptor would be testing the average degree of uridylylation of the particular PII species and not the absolute level of the modified form as proposed above. While this specific situation has not been reported, it is clear that certain receptors are activated by both PII-UMP and PII while others respond only to PII-UMP, which makes this possible competition a real possibility.

This report has largely ignored the location and functionality of the UR activity that is expected in the middle of the protein, but there are two other domains that have been proposed that also might be relevant. ACT domains have been found in functionally diverse proteins and may serve as amino acid-binding sites in some metabolic enzymes (9, 21). Two putative ACT domains have been identified in the extreme C-terminal residues of GlnD of R. rubrum and other organisms (residues 727 to 797 and 839 to 917 of R. rubrum). Given the role of GlnD in sensing glutamine and 2-ketoglutarate, one supposes that these domains might be relevant to that sensing, although this has not been experimentally tested.

A final complication in understanding the broad biological roles of GlnD, and therefore PII, in prokaryotes is that they appear to affect processes other than “simply” the carbon-nitrogen balance. The glnD homolog in Rhizobium tropici appears to be involved in the induction of chlorosis on plants (42). In Vibrio fischeri, a mutant with a glnD transposon insertion displayed defects in iron sequestration, colonization of the light-producing organ of the squid Euprymna scolopes, and nitrogen utilization (15). The fact that GlnB and GlnJ appear to be involved in the light-dark regulation of the DRAT-DRAG system of R. rubrum also falls into this category. As a consequence, it is possible that there might be currently unknown metabolic signals that affect the system, perhaps through effects on GlnD itself. It is conceivable that an ACT domain might play a role in such sensing as well.

In summary, R. rubrum strains with glnD deleted are viable, but the presence of reduced levels of UTase activity had a differential effect on NifA activation, DRAG regulation, and NtrC activation. A hypothesis that lethality of glnD alleles is a direct result of the level of GS activity is proposed, consistent with observations in other organisms. The differential effect of intermediate levels of UTase activity is also rationalized in a model that should be broadly applicable to the analysis of other organisms. The results also show that it is simplistic to think of the role of GlnD as an “all-or-nothing” modulator of different regulated functions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Wisconsin—Madison, Department of Agriculture grant 2001-35318-11014, and NIGMS grant GM65891 to G.P.R.

We thank Stefan Nordlund for generously providing the antiserum against R. rubrum GlnB.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albright, L. M., E. Huala, and F. M. Ausubel. 1989. Prokaryotic signal transduction mediated by sensor and regulator protein pairs. Annu. Rev. Genet. 23:311-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind, L., and E. V. Koonin. 1998. The HD domain defines a new superfamily of metal-dependent phosphohydrolases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:469-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arcondéguy, T., R. Jack, and M. Merrick. 2001. PII signal transduction proteins privotal players in microbial nitrogen control. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:80-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson, M. R., and A. J. Ninfa. 1999. Characterization of the GlnK protein of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 32:301-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bateman, A., E. Birney, L. Cerruti, R. Durbin, L. Etwiller, S. R. Eddy, S. Griffiths-Jones, K. L. Howe, M. Marshall, and E. L. Sonnhammer. 2002. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:276-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger, D. K., F. Narberhaus, and S. Kustu. 1994. The isolated catalytic domain of NIFA, a bacterial enhancer-binding protein, activates transcription in vitro: activation is inhibited by NIFL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:103-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloom, F. R., M. S. Levin, F. Foor, and B. Tyler. 1978. Regulation of glutamine synthetase formation in Escherichia coli: characterization of mutants lacking the uridylyltransferase. J. Bacteriol. 134:569-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng, J., M. Johansson, and S. Nordlund. 1999. Expression of PII and glutamine synthetase is regulated by PII, the ntrBC products, and processing of the glnBA mRNA in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 181:6530-6534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chipman, D. M., and B. Shaanan. 2001. The ACT domain family. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11:694-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colnaghi, R., P. Rudnick, L. He, A. Green, D. Yan, E. Larson, and C. Kennedy. 2001. Lethality of glnD null mutations in Azotobacter vinelandii is suppressible by prevention of glutamine synthetase adenylylation. Microbiology 147:1267-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ditta, G., T. Schmidhauser, E. Yakobson, P. Lu, X.-W. Liang, D. R. Finlay, D. Guiney, and D. R. Helinski. 1985. Plasmids related to the broad host range vector, pRK290, useful for gene cloning and for monitoring gene expression. Plasmid 13:149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards, R., and M. Merrick. 1995. The role of uridylyltransferase in the control of Klebsiella pneumoniae nif gene regulation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 247:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzmaurice, W. P., L. L. Saari, R. G. Lowery, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 1989. Genes coding for the reversible ADP-ribosylation system of dinitrogenase reductase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Mol. Gen. Genet. 218:340-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foor, F., R. J. Cedergren, S. L. Streicher, S. G. Rhee, and B. Magasanik. 1978. Glutamine synthetase of Klebsiella aerogenes: properties of glnD mutants lacking uridylyltransferase. J. Bacteriol. 134:562-568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graf, J., and E. G. Ruby. 2000. Novel effects of a transposon insertion in the Vibrio fischeri glnD gene: defects in iron uptake and symbiotic persistence in addition to nitrogen utilization. Mol. Microbiol. 37:168-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunwald, S. K., D. P. Lies, G. P. Roberts, and P. W. Ludden. 1995. Posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase in Rhodospirillum rubrum strains overexpressing the regulatory enzymes dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyltransferase and dinitrogenase reductase activating glycohydrolase. J. Bacteriol. 177:628-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He, L., E. Soupene, A. Ninfa, and S. Kustu. 1998. Physiological role for the GlnK protein of enteric bacteria: relief of NifL inhibition under nitrogen-limiting conditions. J. Bacteriol. 180:6661-6667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson, N., S. Austin, and R. Dixon. 1989. Role of metal ions in negative regulation of nitrogen fixation by the nifL gene product from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 216:484-491. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hesketh, A., D. Fink, B. Gust, H. U. Rexer, B. Scheel, K. Chater, W. Wohlleben, and A. Engels. 2002. The GlnD and GlnK homologues of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) are functionally dissimilar to their nitrogen regulatory system counterparts from enteric bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 46:319-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holm, L., and C. Sander. 1995. DNA polymerase beta belongs to an ancient nucleotidyltransferase superfamily. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20:345-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh, M. H., and H. M. Goodman. 2002. Molecular characterization of a novel gene family encoding ACT domain repeat proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 130:1797-1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda, T. P., A. E. Shauger, and S. Kustu. 1996. Salmonella typhimurium apparently perceives external nitrogen limitation as internal glutamine limitation. J. Mol. Biol. 259:589-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jack, R., M. De Zamaroczy, and M. Merrick. 1999. The signal transduction protein GlnK is required for NifL-dependent nitrogen control of nif gene expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 181:1156-1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang, P., and A. J. Ninfa. 1999. Regulation of autophosphorylation of Escherichia coli nitrogen regulator II by the PII signal transduction protein. J. Bacteriol. 181:1906-1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang, P., J. A. Peliska, and A. J. Ninfa. 1998. Enzymological characterization of the signal-transducing uridylyltransferase/uridylyl-removing enzyme (EC 2.7.7.59) of Escherichia coli and its interaction with the PII protein. Biochemistry 37:12782-12794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang, P., J. A. Peliska, and A. J. Ninfa. 1998. The regulation of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase revisited: role of 2-ketoglutarate in the regulation of glutamine synthetase adenylylation state. Biochemistry 37:12802-12810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johansson, M., and S. Nordlund. 1999. Purification of PII and PII-UMP and in vitro studies of regulation of glutamine synthetase in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 181:6524-6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johansson, M., and S. Nordlund. 1996. Transcription of the glnB and glnA genes in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. Microbiology 142:1265-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansson, M., and S. Nordlund. 1997. Uridylylation of the PII protein in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 179:4190-4194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamberov, E. S., M. R. Atkinson, and A. J. Ninfa. 1995. The Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein is activated upon binding 2-ketoglutarate and ATP. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17797-17807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanemoto, R. H., and P. W. Ludden. 1984. Effect of ammonia, darkness, and phenazine methosulfate on whole-cell nitrogenase activity and Fe protein modification in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 158:713-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy, C., and M. H. Drummond. 1985. The use of cloned nif regulatory elements from Klebsiella pneumoniae to examine nif regulation in Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Gen. Microbiol. 131:1787-1795. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehman, L. J., and G. P. Roberts. 1991. Identification of an alternative nitrogenase system in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 173:5705-5711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang, J. H., G. M. Nielsen, D. P. Lies, R. H. Burris, G. P. Roberts, and P. W. Ludden. 1991. Mutations in the draT and draG genes of Rhodospirillum rubrum result in loss of regulation of nitrogenase by reversible ADP-ribosylation. J. Bacteriol. 173:6903-6909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Little, R., F. Reyes-Ramirez, Y. Zhang, W. C. van Heeswijk, and R. Dixon. 2000. Signal transduction to the Azotobacter vinelandii NIFL-NIFA regulatory system is influenced directly by interaction with 2-oxoglutarate and the PII regulatory protein. EMBO J. 19:6041-6050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ludden, P. W. 1994. Reversible ADP-ribosylation as a mechanism of enzyme regulation in procaryotes. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 138:123-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez-Argudo, I., R. Little, N. Shearer, P. Johnson, and R. Dixon. 2004. The NifL-NifA system: a multidomain transcriptional regulatory complex that integrates environmental signals. J. Bacteriol. 186:601-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Money, T., J. Barrett, R. Dixon, and S. Austin. 2001. Protein-protein interactions in the complex between the enhancer binding protein NIFA and the sensor NIFL from Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Bacteriol. 183:1359-1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Money, T., T. Jones, R. Dixon, and S. Austin. 1999. Isolation and properties of the complex between the enhancer binding protein NIFA and the sensor NIFL. J. Bacteriol. 181:4461-4468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ninfa, A. J., and M. R. Atkinson. 2000. PII signal transduction proteins. Trends Microbiol. 8:172-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ninfa, A. J., M. R. Atkinson, E. S. Kamberov, J. Feng, and E. G. Ninfa. 1995. Control of nitrogen assimilation by the NRI-NRII two-component system of enteric bacteria, p. 67-88. In J. A. Hoch and T. J. Silhavy (ed.), Two-component signal transduction. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 42.O'Connell, K. P., S. J. Raffel, B. J. Saville, and J. Handelsman. 1998. Mutants of Rhizobium tropici strain CIAT899 that do not induce chlorosis in plants. Microbiology 144:2607-2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pawlowski, A., K. U. Riedel, W. Klipp, P. Dreiskemper, S. Groß, H. Bierhoff, T. Drepper, and B. Masepohl. 2003. Yeast two-hybrid studies on interaction of proteins involved in regulation of nitrogen fixation in the phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 185:5240-5247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perlova, O., R. Nawroth, E. M. Zellermann, and D. Meletzus. 2002. Isolation and characterization of the glnD gene of Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus, encoding a putative uridylyltransferase/uridylyl-removing enzyme. Gene 297:159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porter, S. C., A. K. North, and S. Kustu. 1995. Mechanism of transcriptional activation by NtrC, p. 147-158. In J. A. Hoch and T. J. Silhavy (ed.), Two-component signal transduction. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 46.Reitzer, L. 2003. Nitrogen assimilation and global regulation in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:155-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rudnick, P. A., T. Arcondeguy, C. K. Kennedy, and D. Kahn. 2001. glnD and mviN are genes of an essential operon in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 183:2682-2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schägger, H., and G. von Jagow. 1987. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166:368-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schlüter, A., M. Nöhlen, M. Krämer, R. Defez, and U. B. Priefer. 2000. The Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae glnD gene, encoding a uridylyltransferase/uridylyl-removing enzyme, is expressed in the root nodule but is not essential for nitrogen fixation. Microbiology 146:2987-2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schweizer, H. P. 1993. Small broad-host-range gentamycin resistance gene cassetts for site-specific inserrtion and deletion mutagenesis. BioTechniques 15:831-834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shapiro, B. M., H. S. Kingdon, and E. R. Stadtman. 1967. Regulation of glutamine synthetase. VII. Adenylyl glutamine synthetase: a new form of the enzyme with altered regulatory and kinetic properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 58:642-649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simon, R., U. B. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: tranposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stadtman, E. R. 2001. The story of glutamine synthetase regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44357-44364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strösser, J., A. Lüdke, S. Schaffer, R. Krämer, and A. Burkovski. 2004. Regulation of GlnK activity: modification, membrane sequestration and proteolysis as regulatory principles in the network of nitrogen control in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Mol. Microbiol. 54:132-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Dommelen, A., V. Keijers, E. Somers, and J. Vanderleyden. 2002. Cloning and characterisation of the Azospirillum brasilense glnD gene and analysis of a glnD mutant. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:813-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Heeswijk, W. C., S. Hoving, D. Molenaar, B. Stegeman, D. Kahn, and H. V. Westerhoff. 1996. An alternative PII protein in the regulation of glutamine synthetase in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 21:133-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1991. New pUC-derived cloning vectors with different selectable markers and DNA replication origins. Gene 100:189-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang, Y., R. H. Burris, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 1995. Comparison studies of dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyl transferase/dinitrogenase reductase activating glycohydrolase regulatory systems in Rhodospirillum rubrum and Azospirillum brasilense. J. Bacteriol. 177:2354-2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang, Y., A. D. Cummings, R. H. Burris, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 1995. Effect of an ntrBC mutation on the posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase activity in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 177:5322-5326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang, Y., K. Kim, P. Ludden, and G. Roberts. 2001. Isolation and characterization of draT mutants that have altered regulatory properties of dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyltransferase in Rhodospirillum rubrum. Microbiology 147:193-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang, Y., E. L. Pohlmann, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 2001. Functional characterization of three GlnB homologs in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum: roles in sensing ammonium and energy status. J. Bacteriol. 183:6159-6168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang, Y., E. L. Pohlmann, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 2000. Mutagenesis and functional characterization of the glnB, glnA, and nifA genes from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 182:983-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang, Y., E. L. Pohlmann, P. W. Ludden, and G. P. Roberts. 2003. Regulation of nitrogen fixation by multiple PII homologs in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. Symbiosis 35:85-100. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang, Y., E. L. Pohlmann, and G. P. Roberts. 2004. Identification of critical residues in GlnB for its activation of NifA activity in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:2782-2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]