Abstract

A gene in Legionella pneumophila that has significant homology to published hfq genes demonstrated regulation by RpoS and the transcriptional regulator LetA. Additionally, Hfq has a positive effect on the presence of transcripts of the genes for CsrA and the ferric uptake regulator Fur. Mutants lacking hfq demonstrate defects in growth and pigmentation and slight defects in virulence in both amoeba and macrophage infection models. Hfq appears to play a major role in exponential-phase regulatory cascades of L. pneumophila.

The pleiotropic regulator Hfq (host factor 1, Qβ phage replication) was first characterized in Escherichia coli as necessary for replication of the Qβ phage (33). Hfq has been shown to contribute to virulence in Yersinia enterocolitica, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Vibrio cholerae (7, 23, 31); to adaptation to the intracellular milieu in Brucella species; and to stress response in Listeria monocytogenes (6, 26). Many of the defects seen in the hfq mutants concern efficient translation of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS through interaction with various small RNAs (sRNAs) (5, 6, 16, 25, 38). One functional mechanism is that the interaction with Hfq leads to posttranscriptional gene expression modulation through complementary base pairing of the sRNA with rpoS mRNA (4). The interaction of Hfq with sRNA in the regulation of rpoS mRNA is apparently essential for stress responses in E. coli and P. aeruginosa (31, 33). In L. monocytogenes, Hfq is transcriptionally regulated through the functional homolog to RpoS, the alternative stress sigma factor σB (6), while in V. cholerae, the sigma factor RpoE and not RpoS interacts with Hfq (7). Additionally, Hfq binds directly to other mRNAs, affecting stability (20, 34) and stimulating elongation of poly(A) tails (11). Hfq is capable of stabilizing RNA molecules through protection of the molecule from RNase E degradation (9, 18, 21) or stimulating decay of the mRNA (36).

Legionellae are intracellular pathogens that require a host cell in order to replicate. When Legionella bacteria enter a host cell, it becomes essential to switch off survival and transmission genes and turn on those for replication. In Legionella pneumophila, the species responsible for most cases of Legionnaires' disease, RpoS regulation and function have been shown to diverge from the characteristic RpoS stationary-phase trait induction as found in the enterobacteria (1, 12). Recently it was reported that RpoS transcripts in legionellae appear mainly during exponential-phase growth, disappearing as the bacteria enter stationary phase (2). RpoS functions within a network of regulatory genes, including those encoding the two-component system LetA/S and the global regulatory protein CsrA. All four of these genes have been shown to be important for growth phase-dependent cellular processes (8, 14, 17, 22). The global regulator CsrA is essential for replication in macrophages and for repressing stationary-phase traits, such as flagellar expression, during replication (8, 10, 22). As nutrients are depleted, external signals call for the relief of CsrA repression, accomplished by LetA, allowing transmission and survival trait expression (13, 14). Both CsrA and LetA also affect RpoS expression (10, 17). In an attempt to further elucidate the regulatory system in legionellae, we identified a gene with significant homology to the well-described gene hfq. By using an hfq deletion mutant, we characterized the relationship of Hfq with the regulatory proteins CsrA, LetA, and RpoS, as well as the effects of this deletion on the growth and infectivity of the bacteria.

Transcription and expression of the Legionella Hfq homolog.

The Legionella homolog of Hfq lies in open reading frame (ORF) lpg0009 of the Legionella Genome Project (http://legionella.cu-genome.org/; last accessed November 2004). The Legionella Hfq protein is 64% identical to that in E. coli and 67% identical to that found in P. aeruginosa. Further analysis of the amino acid sequence revealed conservation of the amino acids at positions 8 (Gln), 42 (Tyr), 56 (Lys), and 57 (His), which have been proposed to be necessary for RNA binding (28, 32). However, the conserved chromosomal gene arrangement found in E. coli, V. cholerae, and other organisms is only partially found in L. pneumophila. In E. coli, the hfq gene is part of a multigene operon in which hfq is preceded by the gene miaA and followed by hflX, hflK, and hflC. The Legionella hfq gene is followed by an ORF with homology to the hflX gene, as seen in E. coli; however, these are the only two genes from the operon that are present in this region of the Legionella genome. Upstream of the L. pneumophila hfq gene is an ORF, running in the transverse direction, with homology to a pspA gene. Downstream of the hflX homolog ORF are two ORFs, again with transverse orientation, the first being a thioredoxin homolog and the further one being a putative phospholipase C protein. With the QIAGEN One-Step reverse transcription-PCR kit, experiments with JR32 wild-type exponential-phase cultures grown at 37 and 30°C determined that the hfq-hflX genes are cotranscribed (data not shown). In the hfq mutant background, no signal was obtained from the primers spanning the region of the hfq gene into the hflX gene (RT F2 and RT R2). Experiments with a primer 168 nucleotides upstream of the hfq gene (Hfq ORF F2) and a primer near the end of the hfq gene (RT R1) resulted in no product. Northern blot analysis, conducted as previously described (10), of hfq transcript expression in wild-type strain JR32, a serogroup 1 isolate, demonstrated strong expression during exponential-phase growth (optical density [OD] = 1.2 and 1.5) at 30 and 37°C. No transcripts were detected in stationary-phase bacteria (OD = 1.8) (data not shown). All primers used in this work are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

PCR Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Hfq M F1 | 5′-ACATGCATGCCTCCTGAACGATCTTGAGCAGGA-3′ | This study |

| Hfq M R1 | 5′-GGGGTACCCAGGTACCTTTTCCTTGCGC-3′ | This study |

| Hfq M F2 | 5′-GGGGTACCCAGTTGTTCCTTCTCGAATGGTC-3′ | This study |

| Hfq M R2 | 5′-CGCGGATCCCAAGGTTGCAAACAATTGATCAGC-3′ | This study |

| Hfq ORF Fb,c | 5′-GGGGTACCCTCCTGAACGATCTTGAGCAG-3′ | This study |

| Hfq ORF F2a | 5′-CATCAGTAGCCTGATTCTAGATGTC-3′ | This study |

| Hfq ORF Ra,c | 5′-AAACTGCAGCACCGCCTTGTGGACGTT-3′ | This study |

| RT F2b | 5′-TCAGTGTTCCTGGTCAATGGT-3′ | This study |

| RT R1b | 5′-GTCTGCCACAGTTCCTTCT-3′ | This study |

| RT R2b | 5′-CCGTTTTCATCTACAGACTC-3′ | This study |

| csrA unia | 5′-TTGATTTTGACTCGGCGTATAG-3′ | 10 |

| csrA reva | 5′-GATTCTTTTTCTTGTTGTATGCGTA-3′ | 10 |

| fliA U3a | 5′-TTAGCTGTACTCTGTTTG-3′ | 17 |

| fliA R5a | 5′-TTTATTCCGGTAATCTTGATC-3′ | 17 |

| flaA unia | 5′-GTAATCAACACTAATGTGGC-3′ | 17 |

| flaA reva | 5′-GTTGCAGAATTTGGTTTTTGGTC-3′ | 17 |

| rpoS Fa | 5′-AAAACGTCTTGCGATAACCTG-3′ | 4 |

| rpoS Ra | 5′-CCAAGCGAGGATTCCGTTTTTC-3′ | 4 |

| Fur Luc F | 5′-CGCGGATCCCCAGGTTACCTTTGCCTCG-3′ | This study |

| Fur Luc R | 5′-CCCAAGCTTCTGTAACGAATTTCGAGC-3′ | This study |

| Fur N Fa | 5′-CACATTACCTCGTATCAAGG-3′ | This study |

| Fur N Ra | 5′-GTCATGATGTTCGCCTTGAG-3′ | This study |

Used for single-stranded DNA probe synthesis.

Used for reverse transcription-PCR.

Used for complementation.

Hfq interaction with exponential-phase genes csrA and fur.

An hfq mutant was constructed through homologous recombination in wild-type strain JR32 and verified by standard Southern blot analysis. Cultures for determination of growth and pigmentation kinetics were grown in either standard Legionella BCYE (buffered charcoal-yeast extract) medium or chemically defined medium (24). Experiments were conducted as previously described (10). The hfq mutant revealed defects in growth at both 37°C (Fig. 1a) and 30°C (Fig. 1b) in standard BYE growth medium, as well as in chemically defined minimal medium (Fig. 1c). Pigmentation, a virulence-associated trait, was reduced only when bacteria were grown at 30°C (Fig. 1d). Interestingly, the growth and pigmentation defects seen in the hfq mutant were similar to defects seen in the JR32 csrA mutant at 30°C (10). Under all conditions, the growth deficit appeared to be a delayed lag phase rather than a deficit in replication ability. Growth and pigmentation defects could be complemented by introduction of plasmid pBCKS carrying the hfq gene under the control of its own promoter region (pBC-hfq).

FIG. 1.

Growth curves of the wild-type (♦), hfq mutant (▪), and hfq/pBC-hfq (▴) strains in BYE medium at 37°C (a), BYE medium at 30°C (b), with additional curves for hfq pMMB2002csrA (•) and CDM at 37°C (c), demonstrate growth defects of the hfq mutant. (d) Pigment production by wild-type strain JR32 (▪), the hfq mutant (□), and the hfq/C strain (░⃞) at 37°C in BYE and CDM and 30°C in BYE medium (with pigment production from hfq/pMMB2002csrA (▥).

As hfq expression appeared to be growth phase dependent and mutants exhibited growth and pigmentation defects similar to those seen in the csrA mutant, we examined the relationship of hfq with the global regulatory protein CsrA. We examined csrA transcript expression in the hfq mutant in comparison with wild-type expression through standard Northern blot analysis. CsrA is normally expressed in replicative-phase cells during early and mid-exponential-phase growth and is necessary for replication in amoebae and macrophages (10, 22). In comparison with those in JR32 wild-type cells, csrA transcripts were present but reduced in the hfq mutant (Fig. 2a). Complementation of the mutant with pBC-hfq resulted in a wild-type level of csrA transcript expression. Experiments carried out at 30 and 37°C revealed the same expression pattern among the wild type, the mutant, and the complemented strain (hfq/C).

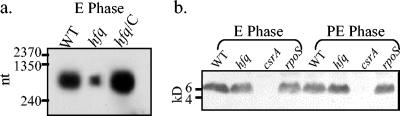

FIG. 2.

(a) Determination of csrA transcription by RNA Northern blot assay. Total RNA (10 μg) isolated from the wild-type (WT), hfq mutant, and hfq/C strains at an OD at 578 nm of 1.2 was applied to a membrane and hybridized with a csrA-specific probe. Strains were grown at 30°C. (b) CsrA protein levels determined by Western blot assay. Ten-microgram samples of protein from exponential (E)- and postexponential (PE)-phase cultures of the wild-type, hfq mutant, csrA mutant, and rpoS mutant strains were analyzed. Experiments were performed four times with independent RNA and protein samples. nt, nucleotides; kD, kilodaltons.

A csrA deletion mutant is characterized by premature expression of transmission and stationary-phase traits. fliA and flaA transcript expression at mid-exponential phase, as well as production of the flagellar protein FlaA, is seen in the csrA deletion mutant (10, 22). Analysis of these traits revealed no defects in the hfq mutant compared to the wild type (data not shown) at either 30 or 37°C. Western blot analysis with a Legionella-specific FlaA antibody (15) provided by K. Heuner (Würzburg University) also revealed no differences from wild-type expression. Because of this flagellar phenotypic difference in the hfq and csrA mutants, CsrA protein levels were examined in the hfq mutant. Western blot assays with an E. coli CsrA-specific antibody (provided by T. Romeo, Emory University) revealed no significant difference in CsrA protein levels between the wild type and the hfq mutant (Fig. 2b). In both strains, as well as an rpoS mutant strain, CsrA protein was present during exponential-phase growth and at the beginning of the stationary phase. For comparison, our regulatory csrA mutant, which still contained minute amounts of csrA mRNA, did not produce detectable amounts of the corresponding protein. Therefore, although csrA mRNA levels were reduced in the hfq mutant, the amount present was capable of being translated to produce levels of CsrA protein necessary for repression of stationary-phase traits. We therefore tested if we could complement the growth and pigmentation defects of the hfq mutant by expressing csrA from a plasmid. With the expression of csrA from plasmid pMMB2002 (27), we were able to restore normal growth and pigment production to the hfq mutant at 30°C, demonstrating that these defects are at least in part due to the interaction of Hfq with csrA RNA (Fig. 1b).

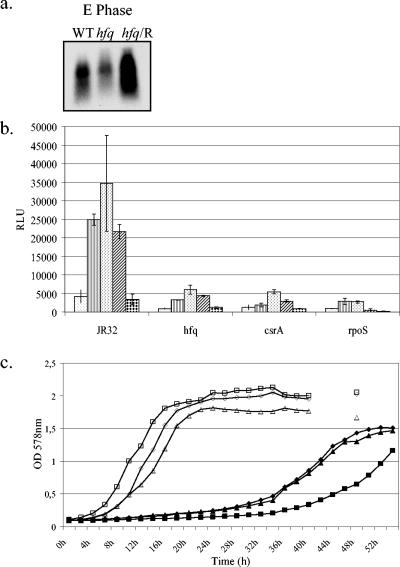

In the process of identifying genes whose expression is affected by loss of the Hfq protein, we also examined the transcription kinetics of the fur gene and the translation efficiency of the fur promoter region in an hfq mutant background. The interaction of the Hfq protein with the ferric uptake regulator has been described in E. coli, functioning through the rhyB sRNA (35). Although not as prominent as the reduction of csrA, the amount of fur transcript was reduced in the L. pneumophila hfq mutant and clearly complemented to more than wild-type levels with the introduction of the hfq gene in trans on multicopy plasmid pBCKS (Fig. 3a). Further analysis at 30 and 37°C with a luciferase reporter gene fusion to the fur promoter region revealed high activity of the fur promoter in wild-type cells during exponential-phase growth, as expected. Luciferase assays were conducted as previously described (17). In comparison, the same pattern of expression was present but clearly reduced in the hfq mutant background. Interestingly, this same reduction in expression was also seen in the csrA and rpoS mutants (Fig. 3b).

FIG. 3.

(a) Determination of fur transcription by RNA Northern blot assay. Total RNA (30 μg) isolated from the wild-type (WT), hfq mutant, and hfq/C strains at an OD at 578 nm of 1.2 was applied to a membrane and hybridized with a fur-specific probe. Bacteria were grown at 30°C. Experiments were performed three times with independent RNA isolates. E, exponential. (b) Luciferase production (relative light units [RLU]) of the JR32, hfq mutant, csrA mutant, and rpoS mutant strains containing a fur-luciferase fusion. Bacteria were grown in BYE medium at 30°C, and samples were taken every 2 h for determination of OD at 578 nm and luciferase activity. Shown are luciferase activities at ODs of 0.5 ( ), 1.2 (▥), 1.5 (

), 1.2 (▥), 1.5 ( ), and 1.8 (▨) and in the late postexponential phase (

), and 1.8 (▨) and in the late postexponential phase ( ). Averages of two experiments with the standard deviations are presented. (c) Growth kinetics of the JR32 (♦), hfq (▪), and hfq/C (▴) strains at 30°C in BYE with excess iron (open symbols) and in chemically defined medium with no iron supplement (closed symbols).

). Averages of two experiments with the standard deviations are presented. (c) Growth kinetics of the JR32 (♦), hfq (▪), and hfq/C (▴) strains at 30°C in BYE with excess iron (open symbols) and in chemically defined medium with no iron supplement (closed symbols).

In order to determine if the defect in Fur expression was a cause for the growth defect, we examined the growth kinetics of the wild type, the mutant, and the complemented strain in BYE medium with twice the normal amount of iron supplement (120 μg) added, as well as in CDM without iron. Experiments were conducted at 30°C, as this is the temperature at which the greatest variation between the wild type and mutant exists. Interestingly, in medium without an iron source the JR32 and hfq/C strains were able to reach OD levels seen in complete CDM but took longer to reach this level. The hfq mutant, however, grew poorly in this medium (Fig. 3c). In medium containing excess iron, the hfq mutant was able to grow at wild-type rates; however, pigment production remained lower than that of the wild type (data not shown). These data point to a role for Hfq in the iron uptake and storage system of L. pneumophila.

Regulation of hfq by RpoS and LetA.

LetA has been well characterized as a activator of stationary-phase phenotypes through relief of CsrA repression (3, 14). We therefore examined the relationship of hfq and letA. hfq expression levels of letA mutant cultures grown at 30°C to the early exponential, mid-exponential, and early stationary phases were compared to wild-type expression levels. At mid-exponential phase, when hfq transcripts were at their highest in wild-type cells, practically no transcripts were found in the letA mutant (Fig. 4a). This defect could be complemented when the letA gene was introduced into the mutant on plasmid pMMB-letA (17). Interestingly, at stationary phase, when hfq transcripts are no longer detectable in wild-type cells, we could detect more hfq transcripts in the letA mutant than seen during the exponential phase (Fig. 4b). It has been previously shown that RpoS is reduced in a letA mutant background (17). Therefore, we were interested in determining if the reduction in hfq transcripts in the letA mutant was due solely to the loss of LetA or perhaps to the reduction of RpoS. Investigations of transcript expression in an rpoS mutant (generously provided by H. Shuman, Columbia University) showed a very low or no signal of hfq transcripts at both 30 and 37°C (Fig. 4c). The increase in hfq transcripts seen in the letA mutant at stationary phase was not seen in the rpoS mutant at that time point. Therefore, hfq transcription appears to be negatively regulated by the LetA protein in the stationary phase but positively regulated in the exponential phase by the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS.

FIG. 4.

Determination of hfq transcription by RNA Northern blot assay. Total RNA (10 μg) isolated from the wild-type (WT), letA mutant, and letA/pMMB-letA strains at an OD at 578 nm of 1.5 (a) or 1.8 (b) was applied to a membrane and hybridized with an hfq-specific probe. Bacteria were grown at 30°C. Experiments were performed three times with independent RNA isolates. The experiment shown in panel c was performed with total RNA from the wild type and the rpoS mutant at an OD at 578 nm of 1.2 or 1.5. (d) Determination of rpoS transcription by Northern blot assay. Total RNA (10 μg) from the wild type, the hfq mutant, and the hfq/C strain were probed with an rpoS-specific probe. Strains were grown at 30°C, and the experiment was repeated twice with independent RNA samples. E, exponential; PE, postexponential. The values on the left are RNA sizes in nucleotides.

Since Hfq has been shown to be necessary for RpoS translation in various other bacterial species (5, 29, 38), we wanted to determine if that was the case for L. pneumophila. We examined rpoS RNA and protein expression in the hfq mutant background in comparison to that in wild-type cells at 30 and 37°C. rpoS mRNA in L. pneumophila strain LP02 has been reported to be expressed during exponential-phase growth but not during stationary phase (2). We confirmed this expression pattern to also be the case in L. pneumophila JR32 (Fig. 4d). Additionally, comparison of rpoS transcripts of the hfq mutant to those of our wild type showed no significant differences in the expression pattern. Further analysis of the translation of RpoS with luciferase assays (17) also demonstrated no differences between the wild type and the hfq mutant (data not shown). This was not caused by a necessary secondary structure of the rpoS mRNA for Hfq function, as a reporter gene fusion vector that included the first 20 nucleotides of the coding region also led to no difference in luciferase expression levels between the wild type and the hfq mutant. In L. pneumophila, hfq is apparently regulated by RpoS and is not, under these growth conditions, necessary for RpoS expression. Thus, the regulation is similar to the regulation of hfq found in L. monocytogenes, where hfq expression is regulated by the RpoS functional homolog σB (6). In gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli and P. aeruginosa, an inverse direction of regulation has been observed (29, 30). Along with this difference in Hfq function in comparison with the E. coli hfq gene, the Legionella hfq gene is also not able to complement an E. coli mutant for Qβ phage replication (30), demonstrating further functional differences in this protein for the two species (data not shown).

Hfq has been shown to be capable of stabilizing mRNA transcripts by protecting the transcripts from RNase E degradation (21). Most likely, the interaction of Hfq with csrA and fur is necessary for stability during the replicative cycle. Analyses of both the csrA and fur gene sequences demonstrate the presence of AU-rich areas that are possible targets for both RNase E and Hfq binding. From the growth curves we could see that the hfq mutant demonstrated more of a prolonged lag phase but, once replication began, was capable of replication at a similar rate and reached the same levels as the wild type. Perhaps this prolonged lag phase is due to degradation of csrA transcripts where at the beginning of the replication cycle the first transcripts are immediately degraded. However, over time a threshold level of csrA transcripts can be reached where more transcripts are produced than can be simultaneously degraded. The excess of transcripts would then allow translation of the CsrA protein, which is then sufficient for replication and repression of stationary-phase traits. The growth and pigmentation defects found in the hfq mutant could then be due at least in part to the reduction in csrA or by other CsrA-independent functions. This theory is supported by the ability of plasmid-expressed csrA to cure the growth and pigment defects of the hfq mutant, as well as by the growth kinetics of hfq and hfq/C in medium with excess iron or without iron.

A proposed scheme of hfq regulation is that in exponential phase RpoS induces the expression of Hfq, which contributes to the stability of exponential-phase RNA, allowing the bacteria to quickly adapt to and efficiently use the replicative environment. Then, when cells respond to signals of nutrient deprivation and must transcend to an infectious, virulent form, LetA, in its role as an inducer of stationary-phase traits (2, 3), either directly or indirectly turns off hfq transcription. This turning off of transcription occurs through an RpoS-independent pathway, as hfq transcripts are not found in rpoS mutants at stationary phase.

Although much about the function of the RNA binding Hfq protein has been published, only few studies have examined its regulation. Our studies open a new area for Hfq research in examining the regulation by the LetA transcriptional activator, as well as the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. Additionally, Hfq is well known to be essential for several regulatory mechanisms through binding with sRNAs. To date, no sRNAs have been identified in legionellae. BLAST searches for homology to the known sRNAs from E. coli, salmonellae, or yersiniae have produced no hits in the Legionella genome (data not shown). Through the use of Hfq, it may now be possible to identify these molecules and determine what role they may play in regulating the biphasic life cycle of legionellae. Further studies should also concentrate on determining the mechanism behind the proposed stabilization of csrA and fur mRNA by Hfq.

Infection assays for virulence in A. castellanii und MH-S macrophages.

Because of the pleiotropic effects of a deletion of hfq, we were interested to see if this also translates into defects in multiplication in living cells. Therefore, Acanthamoeba castellanii host cells were infected with the JR32, hfq, and hfq/C strains at a multiplicity of infection of 10 in accordance with previously published protocols (17). Although no significant differences were found between the wild type and the hfq mutant, the trend demonstrated that the hfq mutant invaded with slightly less efficiency than the wild type (Fig. 5a) at both 30 and 37°C. Replication in the amoebae was not affected at 37°C, but at 30°C it demonstrated a lag in replication reminiscent of that seen in the in vitro growth curves (Fig. 5b). The host cells responsible for supporting human infection are alveolar macrophages. The MH-S mouse alveolar macrophage cell line has been demonstrated to be a competent model for Legionella infection of the lung (19, 37). Infection assays were conducted by standard protocols. Briefly, MH-S cells (106) in six-well plates were infected in duplicate at a multiplicity of infection of 10 with either the JR32, hfq, or hfq/C strain. Bacterial suspensions were plated on BCYE to determine accurate bacterial counts. Plates were centrifuged briefly in order to ensure Legionella contact with the macrophages and then incubated for 2 h. Cells were then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated for a further 60 min in culture medium with gentamicin (200 μg/ml). Cells were then again washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline and incubated until the appropriate time point for analysis. To determine invasion ability, the first set of cells was immediately lysed and bacteria were plated on BCYE agar to determine CFU. The percentage of bacteria capable of invading was calculated as the number of CFU at 2 h divided by the number of CFU in the initial bacterial suspension. Replication ability was calculated as the log of the number of CFU at each time point divided by the number of CFU at 2 h. Each experiment was done with duplicate wells for each time point, and the experiment was conducted three times. The macrophage infection assays again showed no significant differences in invasion between the wild type and the mutant (Fig. 5a) but revealed the same trend seen in the amoeba infections. (Fig. 5b). After 72 h of intracellular growth in macrophages, the hfq mutant had a significant decrease in number compared to the JR32 and hfq/C strains.

FIG. 5.

(a) Invasion capabilities of the hfq mutant ( ) are slightly less than those of the JR32 (

) are slightly less than those of the JR32 ( ) and hfq/C (

) and hfq/C ( ) strains in both A. castellanii amoebae and macrophage cell line MH-S. The invasion capability of all of the strains was less in host amoebae when they were grown at 37°C. (b) No significant differences exist between the replication ability of the JR32 (

) strains in both A. castellanii amoebae and macrophage cell line MH-S. The invasion capability of all of the strains was less in host amoebae when they were grown at 37°C. (b) No significant differences exist between the replication ability of the JR32 ( ), hfq (

), hfq ( ), and hfq/C (

), and hfq/C ( ) strains in amoebae infected at either 30 or 37°C. In infected macrophages, after 72 h the hfq mutant has a slight defect in comparison to wild-type replication ability.

) strains in amoebae infected at either 30 or 37°C. In infected macrophages, after 72 h the hfq mutant has a slight defect in comparison to wild-type replication ability.

We therefore conclude that hfq plays a crucial role in the regulatory network of legionellae that is different from that in other gram-negative bacteria. Despite this, hfq deletions only slightly affect the ability of legionellae to invade cells and multiply intracellularly. It remains to be examined if the defect results in alterations in virulence in an in vivo animal model.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Mueller and A. Flossdorf for excellent technical assistance, B. Yang for performance of the fur luciferase assays, A. Flieger for advice and critical review of the manuscript, T. Romeo and K. Heuner for providing antibodies, N. Cianciotto for the pMMB2002 vector, and I. Moll for the Qβ phage, bacterial strains, and technical advice.

This work was supported by the BMBF Community Acquired Pneumonia Network (CAPNETZ) program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachman, M. A., and M. S. Swanson. 2001. RpoS co-operates with other factors to induce Legionella pneumophila virulence in the stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1201-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachman, M. A., and M. S. Swanson. 2004. Genetic evidence that Legionella pneumophila RpoS modulates expression of the transmission phenotype in both the exponential phase and the stationary phase. Infect. Immun. 72:2468-2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachman, M. A., and M. S. Swanson. 2004. The LetE protein enhances expression of multiple LetA/LetS-dependent transmission traits by Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 72:3284-3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brescia, C. C., P. J. Mikulecky, A. L. Feig, and D. D. Sledjeski. 2003. Identification of the Hfq-binding site on DsrA RNA: Hfq binds without altering DsrA secondary structure. RNA 9:33-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, L., and T. Elliott. 1996. Efficient translation of the RpoS sigma factor in Salmonella typhimurium requires host factor I, an RNA-binding protein encoded by the hfq gene. J. Bacteriol. 178:3763-3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christiansen, J. K., M. H. Larsen, H. Ingmer, L. Sogaard-Andersen, and B. H. Kallipolitis. 2004. The RNA-binding protein Hfq of Listeria monocytogenes: role in stress tolerance and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 186:3355-3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding, Y., B. M. Davis, and M. K. Waldor. 2004. Hfq is essential for Vibrio cholerae virulence and downregulates sigma expression. Mol. Microbiol. 53:345-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fettes, P. S., V. Forsbach-Birk, D. Lynch, and R. Marre. 2001. Overexpression of a Legionella pneumophila homologue of the E. coli regulator csrA affects cell size, flagellation, and pigmentation. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:353-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folichon, M., V. Arluison, O. Pellegrini, E. Huntzinger, P. Regnier, and E. Hajnsdorf. 2003. The poly(A) binding protein Hfq protects RNA from RNase E and exoribonucleolytic degradation. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:7302-7310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsbach-Birk, V., T. McNealy, C. Shi, D. Lynch, and R. Marre. 2004. Reduced expression of the global regulator CsrA in Legionella pneumophila affects virulence-associated regulators and growth in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 294:15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hajnsdorf, E., and P. Regnier. 2000. Host factor Hfq of Escherichia coli stimulates elongation of poly(A) tails by poly(A) polymerase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1501-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hales, L. M., and H. A. Shuman. 1999. The Legionella pneumophila rpoS gene is required for growth within Acanthamoeba castellanii. J. Bacteriol. 181:4879-4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammer, B. K., and M. S. Swanson. 1999. Co-ordination of Legionella pneumophila virulence with entry into stationary phase by ppGpp. Mol. Microbiol. 33:721-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammer, B. K., E. S. Tateda, and M. S. Swanson. 2002. A two-component regulator induces the transmission phenotype of stationary-phase Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 44:107-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heuner, K., L. Bender-Beck, B. C. Brand, P. C. Luck, K. H. Mann, R. Marre, M. Ott, and J. Hacker. 1995. Cloning and genetic characterization of the flagellum subunit gene (flaA) of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. Infect. Immun. 63:2499-2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lease, R., and M. Belfort. 2000. A trans-acting RNA as a control switch in E. coli: DsrA modulates function by forming alternative structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:9919-9924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynch, D., N. Fieser, K. Gloggler, V. Forsbach-Birk, and R. Marre. 2003. The response regulator LetA regulates the stationary-phase stress response in Legionella pneumophila and is required for efficient infection of Acanthamoeba castellanii. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 219:241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masse, E., F. E. Escorcia, and S. Gottesman. 2003. Coupled degradation of a small regulatory RNA and its mRNA targets in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 17:2374-2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsunaga, K., T. W. Klein, H. Friedman, and Y. Yamamoto. 2001. Alveolar macrophage cell line MH-S is valuable as an in vitro model for Legionella pneumophila infection. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 24:326-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moll, I., D. Leitsch, T. Steinhauser, and U. Blasi. 2003. RNA chaperone activity of the Sm-like Hfq protein. EMBO Rep. 4:284-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moll, I., T. Afonyushkin, O. Vytvytska, V. R. Kaberdin, and U. Blasi. 2003. Coincident Hfq binding and RNase E cleavage sites on mRNA and small regulatory RNAs. RNA 9:1308-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molofsky, A. B., and M. S. Swanson. 2003. Legionella pneumophila CsrA is a pivotal repressor of transmission traits and activator of replication. Mol. Microbiol. 50:445-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakao, H., H. Watanabe, S. Nakayama, and T. Takeda. 1995. yst gene expression in Yersinia enterocolitica is positively regulated by a chromosomal region that is highly homologous to Escherichia coli host factor 1 gene (hfq). Mol. Microbiol. 18:859-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reeves, M. W., L. Pine, J. B. Neilands, and A. Balows. 1983. Absence of siderophore activity in Legionella species grown in iron-deficient media. J. Bacteriol. 154:324-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson, G. T. and R. M. Roop, Jr. 1999. The Brucella abortus host factor I (HF-I) protein contributes to stress resistance during stationary phase and is a major determinant of virulence in mice. Mol. Microbiol. 34:690-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roop, R. M., G. T. Robertson, G. P. Ferguson, L. E. Milford, M. E. Winkler, and G. C. Walker. 2002. Seeking a niche: putative contributions of the hfq and bacA gene products to the successful adaptation of the brucellae to their intracellular home. Vet. Microbiol. 90:349-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossier, O., S. Starkenburg, and N. P. Cianciotto. 2004. Legionella pneumophila type II protein secretion system promotes virulence in the A/J mouse model of Legionnaires' disease. Infect. Immun. 72:310-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schumacher, M. A., R. F. Pearson, T. Moller, P. Valentin-Hansen, and R. G. Brennan. 2002. Structures of the pleiotropic translational regulator Hfq and an Hfq-RNA complex: a bacterial Sm-like protein. EMBO J. 21:3546-3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sledjeski, D. D., A. Gupta, and S. Gottesman. 1996. The small RNA, DsrA, is essential for the low temperature expression of RpoS during exponential growth in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 15:3993-4000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sonnleitner, E., I. Moll, and U. Blasi. 2002. Functional replacement of the Escherichia coli hfq gene by the homologue of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 148:883-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonnleitner, E., S. Hagens, F. Rosenau, S. Wilhelm, A. Habel, K. E. Jager, and U. Blasi. 2003. Reduced virulence of a hfq mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa O1. Microb. Pathog. 35:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun, X., I. Zhulin, and R. M. Wartell. 2002. Predicted structure and phyletic distribution of the RNA-binding protein Hfq. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:3662-3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsui, H. C., H. C. Leung, and M. E. Winkler. 1994. Characterization of broadly pleiotropic phenotypes caused by an hfq insertion mutation in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 13:35-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsui, H. C., G. Feng, and M. E. Winkler. 1997. Negative regulation of mutS and mutH repair gene expression by the Hfq and RpoS global regulators of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 179:7476-7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vecerek, B., I. Moll, T. Afonyushkin, V. Kaberdin, and U. Blasi. 2003. Interaction of the RNA chaperone Hfq with mRNAs: direct and indirect roles of Hfq in iron metabolism of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 50:897-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vytvytska, O., I. Moll, V. R. Kaberdin, A. von Gabain, and U. Blasi. 2000. Hfq (HF1) stimulates ompA mRNA decay by interfering with ribosome binding. Genes Dev. 14:1109-1118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan, L., and J. D. Cirillo. 2004. Infection of murine macrophage cell lines by Legionella pneumophila. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 230:147-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, A., S. Altuvia, A. Tiwari, L. Argaman, R. Hengge-Aronis, and G. Storz. 1998. The OxyS regulatory RNA represses RpoS translation and binds the Hfq (HF-I) protein. EMBO J. 17:6061-6068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]