Abstract

Background: Obesity is a global epidemic that affects both developed and developing countries. According to World Health Organization (WHO), in 2014, over 1.9 billion adults were overweight. Burkina Faso, like other countries, faces the problem of obesity, with a prevalence of 7.3%. The main cause is excessive intake of caloric foods combined with low physical activity, although genetic, endocrine and environmental influences (pollution) can sometimes be predisposing factors. This metabolic imbalance often leads to multiple pathologies (heart failure, Type II diabetes, cancers, etc.). Drugs have been developed for the treatment of these diseases; but in addition to having many side effects, locally these products are not economically accessible to the majority of the population. Burkina Faso, like the other countries bordering the Sahara, has often been confronted in the past with periods of famine during which populations have generally used anorectic plants to regulate their food needs. This traditional ethnobotanical knowledge has not been previously investigated. An ethnobotanical survey was conducted in Burkina Faso in the provinces of Seno (North) and Nayala (Northwest) to list the plants used by local people as an anorectic and/or fort weight loss. Methods: The survey, conducted in the two provinces concerned traditional healers, herbalists, hunters, nomads and resourceful people with knowledge of plants. It was conducted over a period of two months and data were collected following a structured interview with the respondents. The approach was based on dialogue in the language of choice of the respondent and the use of a questionnaire. The data have been structured and then statistically analyzed. Results: The fifty-five (55) respondents of the survey were aged between 40 and 80 years. Sixty-one (61) plant species, belonging to thirty-one (31) families were listed as appetite suppressants and/or for their anti-obesity properties. The main families of plants are Mimosaceae, Rubiaceae, Asclepiadaceae and Cesalpiniaceae. Fruits are the most used part of the plant organs. Consumption in the raw state or as a decoction are the two main forms of preparation. Conclusion: The great diversity of plants cited by informants demonstrates the existence of rich local knowledge to address obesity in Burkina Faso. Evaluation of the biochemical activity of the extracts of the most cited species could allow the development of a phytomedicine economically accessible to the majority of the population. This could allow for the preservation of biodiversity in this region which is weakened by climate change because some of the species cited are in fragile state or are threatened with extinction.

Keywords: obesity, anorexigenic plant, Burkina Faso, metabolic disease, ethnobotany

1. Introduction

Obesity is a condition that concerns people of all ages in both developed and developing countries. According to the World Health organization (WHO), in 2014, over 1.9 billion adults were overweight in the world. Burkina Faso has faced a fast growing obesity problem in the last decade, and today more than 7.3% of its population is affected [1]. In addition to being a social handicap, this metabolic imbalance is often associated with diseases such as hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, type II diabetes, dyslipidemia and certain cancers [2]. Excessive weight gain is usually caused by increased consumption of high caloric foods and decreased physical activity. Genetic (familial predisposition), biological (endocrine disorders), environmental (pollution) [3] factors may also contribute to this problem.

In Burkina Faso as in most developing countries, urbanization and socio-economic development are accompanied by a change in diet towards more with a high energy density foods (more meat, fat, salt and sugary foods) as well as a reduction in physical activity (mechanized transport) [4] resulting in increased storage of the excess calories as fat in adipose tissue. An aggravating cause of the situation in Africa is the antiquated traditional African conception of affluence, according to which obesity of women is a positive indicator of the material abundance of the family and of a good reproductive health. One can find, in the pharmaceutical market, some synthesis of chemical drugs that are used against obesity: Sibutral, Rimonabant, Isomeride, Xenical, Lorcaserin, Ponderal, Alli, and Qsymia. But the cost of these products generally puts them out of reach of most people; and worse, many of these products have many side effects [5].

That is the reason for the withdrawal from the market of some older drugs such as Sibutral, Rimonabant, Isomeride, Ponderal and Xenical [5,6]. The development of new antiobesity molecules from natural products has become a necessity. This seems realizable because in phytotherapy, several types of plants are used against this disease. The plant bioactive extracts would act through their inhibitory activities for digestive lipases, adipocyte differentiation, or by increasing thermogenesis and anorexia [7]. Burkina Faso, like other Sahelian countries, has often been confronted in the past with periods of famine. During these times of food shortage, people have generally used plants with anorectic effects to regulate their food and drink intake. Burkina Faso is also a savannah country with many nomadic and hunter societies. During their displacements or hunting parties, these people could be facing period of lack of food or water. These populations survived thanks to a strong ethnobotanical knowledge able to help in the management of satiety. However, in Burkina Faso there are few data on these plant species used as anorectics or against obesity. An ethnobotanical survey was conducted in the province of Seno (nomadic area in Burkina Faso northern area) and the Nayala (traditional hunting area in northwest of Burkina Faso) in order to collect information on plants used by local people as anorectics and/or to manage weight. This study aimed to establish an inventory of appetite suppressant or antiobesity plant species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

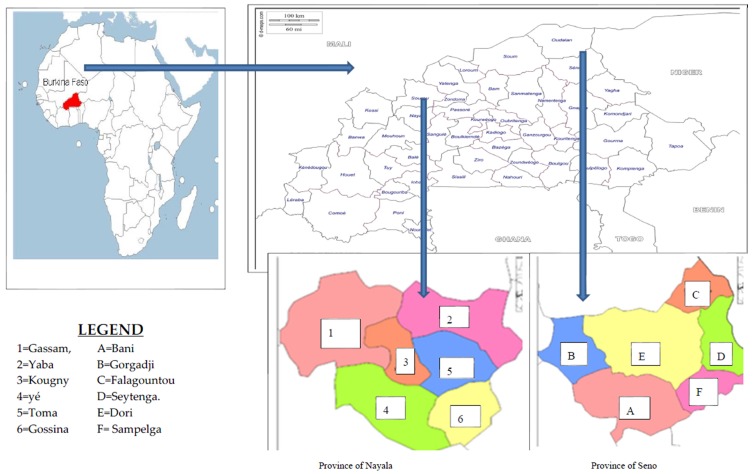

Burkina Faso (Figure 1) is a landlocked country located in the heart of West Africa and enclosed between six countries: Mali, Niger, Benin, Togo, Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire. It covers an area of approximately 274,000 km². It is located inside the loop of the Niger River between 10 ° and 15 ° north latitude and between 2° east and 5°30’ west longitude. Its capital city is Ouagadougou. The climate is characterized by a long dry season (from October to May) and an irregular rainy season (from June to September). Monthly average temperatures range between 22 °C and 42 °C. Except for the extreme north which consists of desert or semi-desert, Burkina Faso is a savannah country. The homogenous and seasonal-dependent vegetal landscape is constituted by Parkia biglobosa (Néré in French), Vitellaria paradoxa (Karité in French), Cassia sp and Andasonia digitata ecosystems. This country is divided into 45 provinces grouped into 13 regions.

Figure 1.

Maps of the survey area.

The surveys were conducted in the two north provinces where nomadic or hunting populations reside.

Seno Province, whose capital is Dori, is located in the north eastern area of Burkina Faso. It has 215 villages and an area of 6979 km2 with a population of 264,815 people [8]. This locality has a Sahelian climate, characterized by a long dry season (May to October) and a short rainy season (average rainfall of 400 mm), with varying temperatures (10–43 °C), low humidity, wind and a large amounts of sunshine, typical of the Sahel. The vegetation is characterized by wooded and shrubby steppe that is heavily damaged. However, there are a few gallery forests which are generally located along the rivers (like the swamp of Dori or the Yakouta River). The dominant types of vegetation are thorn trees [9].

Famine is recurrent in this province. The predominant population is the Fulani group, who are nomadic herders. They have survived drought in this region through their knowledge of appetite suppressing plants.

Located in the northwest of Burkina Faso, Nayala province (whose capital is Toma) has an area of 3919 km2 with a population of 156,861 and a northern Sudanian climate. The vegetation consists of shrub or herbaceous savannah with some groves near villages. Soils are clayey [10]. Many hunter groups live in this province. It often happens that these hunters lose themselves in the bush tracking a hunted animal. To survive these situations (temporary lack of water or food, which can take days), they have developed a rich ethnobotanical knowledge on plants possessing appetite suppressing or thirst quenching properties.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Data Collection

The ethnobotanical survey was conducted in the provinces of Seno and Nayala during the period from August to September 2013. Over 70 interviews were conducted in different localities of these provinces. Data were collected following a structured interview with traditional healers, herbalists and hunters. These groups are located in each of these areas, organized in associations. A preliminary meeting was held during which they were informed about the objectives of the study. After information was provided, the people who agreed to participate in the survey were individually interviewed. The approach was based on a dialogue using the language of choice of the respondent and the use of a questionnaire. A field trip was organized and plants mentioned in the interview were collected with the help of the respondent in order to make the herbal constitution. The intervention of interpreters was necessary in some cases. The cited and harvested plant specimens were identified by Professor Jeanne Millogo-Rasolodimby (Botanist, Department of Ecology/University of Ouagadougou).

2.2.2. Data Analysis

Survey data were first extracted manually then entered and processed by Excel software. The citation frequencies of all data obtained from this study was subjected to descriptive statistical analysis by calculating of frequency of plant citations, using the formula:

| (1) |

2.2.3. The Use Value Index (UVI)

The use value index (UVI) of a species for each use class is evaluated to show the importance that people attach to a given species in the localities [11]. It is obtained by calculating the following:

| UVI = U/N | (2) |

Where U is the number of times that species is cited for a category of use and N the total number of informants.

3. Results

3.1. Results

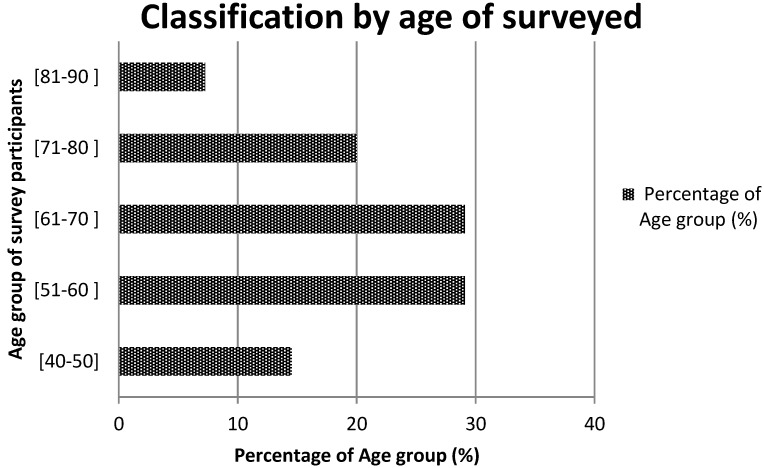

3.1.1. Traditional Knowledge: Age and Gender

During the survey 55 people have been interviewed including 34 in Nayala and 21 in Seno. The mean age varies between 40 and 81 years and over 50% were between 50 and 70 years old (Figure 2). The practice time (in years) varies between 7 and 35. Men represented 92.7% of the respondents versus 7.3% what were women. All were traditional healers, herbalists, hunters or elderly nomadic person with knowledge on plants. In total 62 plant species belonging to 32 families were listed as having anorectic and/or anti-obesity activity. Table 1 shows the list and ethno-botanic characteristics of these plant species.

Figure 2.

Age group of informants.

Table 1.

Plants listed after the survey in Seno and Nayala.

| Species and Family | Local Name | Frequency Citation (%) | Parts Used | Indication | Preparation and Use Methods | Posology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Acacia laeta Benth. (Fabaceae) | Gon sablega (mo) | 1.7 | bark | weight loss | decoction | ND |

| 2. Acacia nilotica(L.) Delile (Fabaceae) | 1.7 | bark | weight loss | decoction | ND | |

| 3. Acacia senegal (L.) Willd. (Fabaceae) | Gommier (Fran) | 3.4 | gum | appetite suppressant and thirst quencher | raw gum consumption | ND |

| 4. Acacia seyal Del. (Fabaceae) | Gon-miougou | 1.7 | bark | weight loss | decoction | ND |

| 5. Adansonia digitata L. (Bombacaceae) | Baobab (fran) | 3.4 | root and bark | thirst quencher | raw root and bark consumption | ND |

| 6. Afzelia africana Smith ex Pers. (Fabaceae) | Para (san) | 1.7 | leaves | weight loss | decoction of a mixture of afzelia africana leaves and roots of cochlospermum tinctorium is used as a drink | ND |

| 7. Annona senegalensis Pers. (Annonaceae) | Guinikou (san) | 3.4 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 8. Azadirachta indica A. Juss. (Meliaceae) | Kakki (ful) | 1.7 | leaves | weight loss | decoction of the bark and use as a drink before meal | ND |

| 9. Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile (Balanitaceae) | Tanèè (ful), sinbèlè (san) | 10.16 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 10. Bauhinia rufescens Lam. (Fabaceae) | Tipoiga (mo) | 3.4 | bark | weight loss | decoction | ND |

| 11. Boscia angustifolia A. Rich. (Capparaceae) | Haasu carè (sonrai) | 3.4 | young leaves | weight loss | reduce young dried leaves in powder and mix this powder with porridge and drink | ND |

| 12. Brachystelma bingeri A.Chev. (Asclepiadaceae) | Sensenega (mo), Daffio (tmac) | 15.25 | roots | appetite suppressant and thirst quencher | raw root consumption | ND |

| 13. Cadaba farinosa Forsk. (Capparidaceae) | Moussilèè (san) | 3.4 | leaves | appetite suppressant | raw leaves consumption | Causes fart |

| 14. Ceratotheca sesamoides Endl. (Pedaliaceae) | Dou (san) | 6.78 | leaves | appetite suppressant and thirst quencher | raw leaves consumption | ND |

| 15. Ceropegia senegalensis H. (Apocynaceae) | Kirimougoin (san) | 3.4 | roots | appetite suppressant | raw root consumption | ND |

| 16. Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. (Cucurbitaceae) | Dènè (ful) | 8.47 | fruits | appetite suppressant and thirst quencher | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 17. Citrus aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle (Rutaceae) | 3.4 | fruits | weight loss | decoction of the leaves of combretum micranthum then add fruit juice of citrus aurantifolia and use as a drink | 1 liter per day for 2 to 3 months | |

| 18. Cochlospermum planchonii Hook. f. ex Planch. (Cochlospermaceae) | Biripin (san) | 3.4 | roots | weight loss | decoction | ND |

| 19. Cochlospermum tinctorium Perrier ex A. Rich. (Cochlospermaceae) | Gotoro (san) | 1.7 | roots | weight loss | decoction of afzelia africana leaves and roots of cochlospermum tinctorium and use as a drink | ND |

| 20. Combretum micranthum G. Don. (Combretaceae) | Randega (mo) | 1.7 | leaves | weight loss | decoction of the leaves of combretum micranthum then add the fruit juice of citrus aurantifolia and use as a drink | 1 liter per day for 2 to 3 months |

| 21. Commiphora africana (A. Rich.) Endl. (Curceraceae) | Nbadadi (ful) | 11.86 | roots | appetite suppressant and thirst quencher | raw roots consumption | ND |

| 22. Cordia africana Lam. (Boraginaceae) | 1.7 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND | |

| 23. Detarium microcarpum Guill. et Perr. (Fabaceae) | Koro (san) | 3.4 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 24. Digitaria exilis (Kippist) Stapf (Poaceae) | Pii (san) | 1.7 | seeds | weight loss | cooking and eat | ND |

| 25. Dioscorea bulbifera L. (Dioscoreaceae) | Kou (san) | 1.7 | roots | appetite suppressant | raw root consumption | ND |

| 26. Diospyros mespiliformis Hochst. ex A.DC (Ebenaceae) | 1.7 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND | |

| 27. Entada africana Guill et Perr. (Fabaceae) | Séremanan (san) | 1.7 | leaves | weight loss | decoction | ND |

| 28. Fadogia agrestis Schweinf. ex Hiern (Rubiaceae) | 1.7 | roots | appetite suppressant | raw consumption | ND | |

| 29. Ficus sycomorus L. (Moraceae) | Goro (san) | 3.4 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 30. Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch (Rubiaceae) | Kowin (san) | 1.7 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 31. Gardenia erubescens Stapf & Hutch (Rubiaceae) | Kouin (san) | 20,34 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 32. Grewia bicolor Juss. (Tiliaceae) | Keli (ful) | 1.7 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 33. Grewia flavescens Juss. (Tiliaceae) | 1.7 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND | |

| 34. Grewia villosa Willd. (Tiliaceae) | Kiborlohi (ful) | 1.7 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | 1 glass of fruit has anorectic effects for a half day |

| 35. Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (Malvaceae) | Fouon (san) | 5.08 | seeds | appetite suppressant | decoction | ND |

| 36. Holarrhena floribunda (G.Don) T.Durand & Schinz var. florinbunda (Apocynaceae) | Ninogga (mo) | 1.7 | leaves | weight loss | decoction | ND |

| 37. Hyphaene thebaica (L.) Mart (Arecaceae) | Gelohi (ful) | 1.7 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 38. Khaya senegalensis (Desv.) A.Juss. (Meliaceae) | Kuka (mo) | 1.7 | bark | weight loss | decoction | ND |

| 39. Lannea microcarpa Engl. & K. Krause (Anacardiaceae) | Touo (san) | 1.7 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 40. Leptadenia hastata Vatke (Asclepiadaceae) | Toun (sa) Tatola (tmac) |

10.16 | leaves and fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 41. Mitragyna inermis (Willd.) Kuntze (Rubiaceae) | Kadioli (ful) | 1.7 | leaves and bark | weight loss | decoction of the bark or leaves and use as a drunk | ND |

| 42. Moringa oleifera Lam (Moringaceae) | Basankoé (san) | 1.7 | principal root | weight loss | make a decoction of the dried primary root and use as a drink | ND |

| 43. Ozoroa insignis Del. (Anacardiaceae) | Bouwélèbondan (san) | 5.08 | leaves | weight loss | decoction of the leaves and use for drinking and washing | ND |

| 44. Panicum laetum Kunth (Poaceae) | 1.7 | seeds | appetite suppressant | decoction | ND | |

| 45. Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.) G.Don (Fabaceae) | Koussi (san) | 3.4 | bark, root | weight loss | decoction of the roots of ximenia americana and bark of parkia biglobosa, drinking and wash with decoction | ND |

| 46. Phoenix dactylifera L. (Arecaceae) | Datte (fran) | 1.7 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruit consumption | ND |

| 47. Pseudocedrela kotschyi (Schweinf.) Harms (Meliaceae) | Siguédré (mo) | 1.7 | small branches | thirst quencher | raw small branches consumption | ND |

| 48. Raphionacme daronii Berhaut (Asclepiadaceae) | Goin (sa) | 25.42 | root | appetite suppressant and thirst quencher | raw root consumption | ND |

| 49. Saba senegalensis (A.DC.) Pichon var. senegalensis (Apocynaceae) | Mara (san) | 3.4 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 50. Sarcocephalus latifolius (Sm.) E.A.Bruce (Rubiaceae) | 3.4 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND | |

| 51. Sclerocarya birrea (A.Rich.) Hochst. (Anacardiaceae) | Nobga (Mo) | 3.4 | fruits | thirst quencher | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 52. Sterculia setigera Delile (Sterculiaceae) | 1.7 | gum | appetite suppressant | raw gum consumption | ND | |

| 53. Strychnos spinosa Lam. Lam (Loganiaceae) | Kartountoun (sa) | 3.4 | fruits | appetite suppressant and thirst quencher | raw fruits consumption | Excess fruit gives stomach bloating |

| 54. Tamarindus indica L. (Fabaceae) | Inguètabi (ful) | 5.08 | bark, fruits root | weight loss | 1. decoction of the bark powder and dried fruit and use as drink 2. decoction of the roots and use as a drink |

Take half glass of tea decoction in the morning and noon before meals |

| 55. Terminalia avicennioides Guill. & Perr. (Combretaceae) | Sounsoun (san) | 1.7 | root | thirst quencher | raw roots consumption | ND |

| 56. Terminalia macroptera Guill. & Perr. (Combretaceae) | Kouon (san) | 3.4 | young leaves | appetite suppressant | raw leaves consumption | ND |

| 57. Vernonia kotschyana Sch.Bip. ex Walp. (Astéraceae) | Yirimassa (diou) | 5.08 | root | appetite suppressant | raw root consumption (fresh or dried) | |

| 58. Vitellaria paradoxaC.F.Gaertn. (Sapotaceae) | Kouu (san) | 5.08 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 59. Vitex doniana Sweet (Verbenaceae) | Koutiin (san) | 3.4 | fruits | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption | ND |

| 60. Ximenia americana L. (Olacaceae) | Marafoo (san) | 1.7 | root | weight loss | decoction of the roots of ximenia americana and bark of parkia biglobosa, drink and wash with decoction | ND |

| 61. Xysmalobium heudelotianum Decne. (Asclepiadaceae) | Kirimougoin (san) | 1.7 | root | appetite suppressant | raw root consumption | ND |

| 62. Zizyphus mauritiana Lam. (Rhamnaceae) | Guiabè (ful), tomon (san) | 6.78 | fruits, root | appetite suppressant | raw fruits consumption, boil the roots and take the decoction beverage | Take ½ glass of decoction on morning and evening |

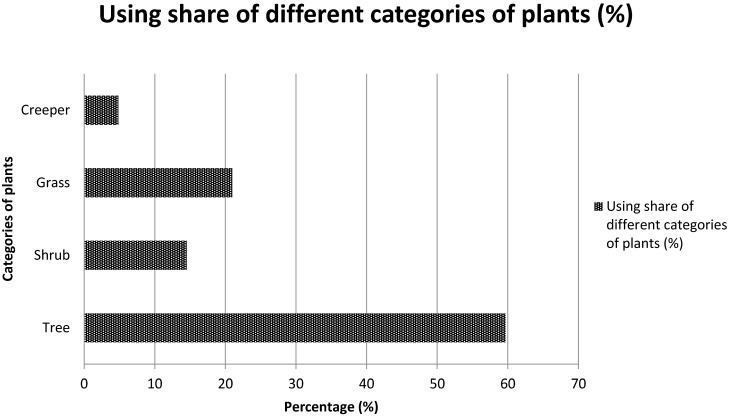

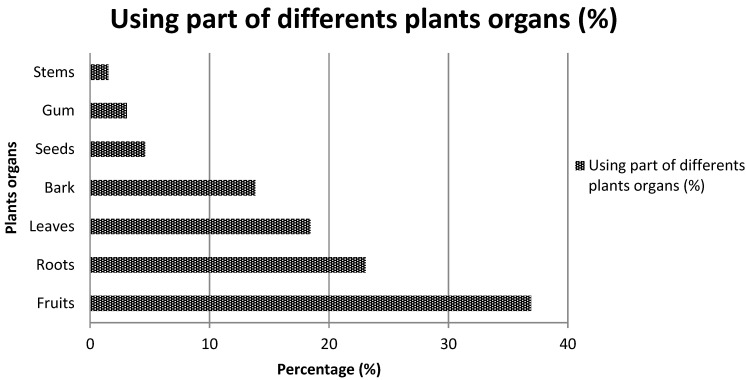

3.1.2. Part of Plant and Method of Preparation

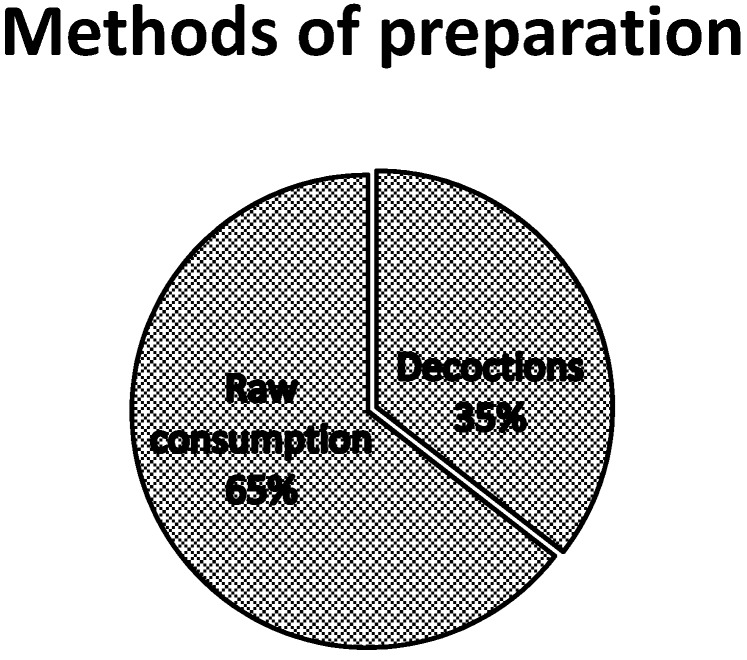

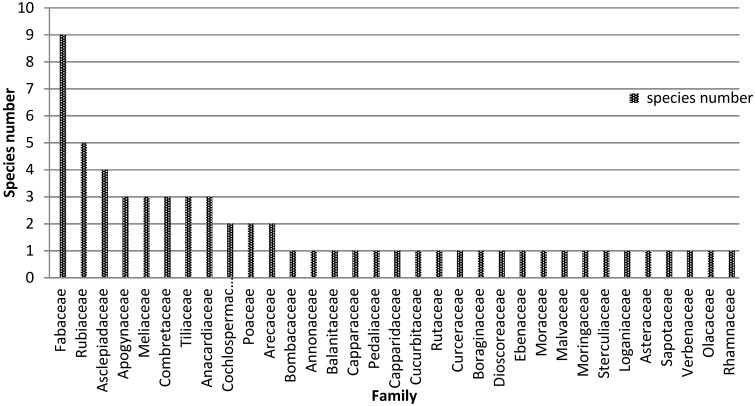

The analysis of the mode of use of the various listed plants revealed that 53.6% of plants are appetite suppressants, 30.4% are used to lose weight and 15.9% are used as a thirst quencher. Most of the species cited are trees (59.6%), followed by shrubs (20.9%), herbs (14.5%) and creeping plants (4.8%) (Figure 3). Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 present the species which are used as appetite suppressants, for weight reduction and as thirst quenchers; with the part used and the use value indexes. Raphionacme daronii Berhaut. (Asclepiadaceae) is the most commonly used species for appetite suppressant activity, with a use value index of 0.27; followed by Gardenia erubescens Stapf and Hutch. (Rubiaceae) with 0. 22 as its use value index. For slimming property, the species Tamarindus indica L. (Caesalpiniaceae) and Ozoroa insignis Del. (Anacardiaceae) are the most used with use value of 0.05. Raphhionacme daronii Berhaut. (Asclepiadaceae) and Brachystelma bingeri A. Chev. (Asclepiadaceae) with respective use value indexes of 0.27 and 0.16 are most commonly used as a thirst quencher. Concerning part of plants, fruits have the highest frequency of use (Figure 4). Decoctions (35.5%) and raw consumption (64.5%) (Figure 5) are the main forms of use. Oral ingestion is the main means of administration.

Figure 3.

Applied share of different categories of plants.

Table 2.

Species with supposed appetite suppressant activity, their use value index and the parts used.

| Species | Use value Index | Parts Used |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Annona senegalensis | 0.036 | Fruits |

| 2. Balanites aegyptiaca | 0.109 | Fruits |

| 3. Brachystelma bingeri | 0.163 | Tuber |

| 4. Cadaba farinosa | 0.036 | Leaves |

| 5. Ceratotheca seésamoiïdes | 0.072 | Leaves |

| 6. Ceropeogia senegalensis | 0.036 | Roots |

| 7. Citrullus colocynthis | 0.090 | Fruits |

| 8. Commiphora africana | 0.127 | Bark |

| 9. Cordia africana | 0.018 | Fruits |

| 10. Detarium microcarpum | 0.036 | Fruits |

| 11. Dioscorea bulbifera | 0.018 | Tuber |

| 12. Diospyros mespiliformis | 0.018 | Fruits |

| 13. Fadogia agrestis | 0.018 | Roots |

| 14. icus sycomorus | 0.036 | Fruits |

| 15. Gardenia aqualla | 0.018 | Fruits |

| 16. Gardenia erubescens | 0.218 | Fruits |

| 17. Grewia bicolor | 0.018 | Fruits |

| 18. Grewia flavescens | 0.018 | Fruits |

| 19. Grewia villosa | 0.018 | Fruits |

| 20. Hibiscus sabdariffa | 0.054 | Seeds |

| 21. Hyphaene thebaica | 0.018 | Fruits |

| 22. Lannea microcarpa | 0.018 | Fruits |

| 23. Leptadenia hastata | 0.109 | Leaves |

| 24. Panicum laetum | 0.018 | Seeds |

| 25. Phoenix dactylifera | 0.018 | Fruits |

| 26. Raphionacme daronii | 0.272 | Tuber |

| 27. Sarcocephalus latifolus | 0.036 | Fruits |

| 28. Sclerocarya birrea | 0.036 | Fruits |

| 29. Sterculia setigera | 0.036 | Gum |

| 30. Strychnos spinosa | 0.018 | Fruits |

| 31. Saba senegalensis | 0.018 | Fruits |

| 32. Terminalia macroptera | 0.036 | Leaves |

| 33. Tamarindus indica | 0.054 | Fruits |

| 34. Vernonia kotschyana | 0.054 | Roots |

| 35. Vitellaria paradoxa | 0.054 | Fruits |

| 36. Vitex doniana | 0.036 | Fruits |

| 37. Xysmalobuium heudelotianum | 0.018 | Tuber |

| 38. Zizyphus mauritiana | 0.072 | Fruits |

Table 3.

Plants having weight reduction potential, their use value index and the parts used.

| Species | Use Value Index | Parts Used |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Acacia laeta | 0.018 | Bark |

| 2. Acacia nilotica | 0.018 | Bark |

| 3. Acacia seyal | 0.018 | Bark |

| 4. Afzelia africana | 0.018 | Leaves |

| 5. Azadirachta indica | 0.018 | Leaves |

| 6. Bauhinia rufescens | 0.036 | Bark |

| 7. Boscia angustifolia | 0.036 | Young leaves |

| 8. Citrus aurantiifolia | 0.036 | Fruits |

| 9. Cochlospermum planchonii | 0.036 | Root |

| 10. Cochlospermum tinctorium | 0.018 | Root |

| 11. Combretum micranthum | 0.018 | Leaves |

| 12. Digitaria exilis | 0.018 | Seeds |

| 13. Entada africana | 0.018 | Leaves |

| 14. Holarrhena floribunda | 0.018 | Leaves |

| 15. Khaya senegalensis | 0.018 | Bark |

| 16. Mitragyna inermis | 0.018 | Leaves and bark |

| 17. Moringa oleracea | 0.018 | Root |

| 18. Ozoroa insignis | 0.054 | Leaves |

| 19. Parkia biglobosa | 0.036 | Bark and seeds |

| 20. Tamarindus indica | 0.054 | Bark and fruits |

| 21. Ximenia americana | 0.018 | Root |

Table 4.

Thirst quencher Species with supposed thirst quenching activity, their usual value an the parts used.

| Species | Use Value Index | Parts Used |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Acacia senegal | 0.036 | Gum |

| 2. Adansonia digitata | 0.036 | Bark |

| 3. Brachystelma bingeri | 0.163 | Tuber |

| 4. Ceratotheca sesamoides | 0.072 | Leaves |

| 5. Citrullus colocynthis | 0.090 | Fruits |

| 6. Commiphora africana | 0.127 | Bark |

| 7. Pseudocedrela kotschyi | 0.018 | Stem |

| 8. Raphionacme daronii | 0.272 | Tuber |

| 9. Sclerocarya birrea | 0.036 | Fruits |

| 10. Strychnos spinosa | 0.036 | Fruits |

| 11. Terminalia avicennioides | 0.018 | Seeds |

Figure 4.

Using part of different plant organs.

Figure 5.

Use of various preparation methods.

3.1.3. Families of Plants Used

The study indicates that Mimosaceae, Rubiaceae, Asclepiadaceae, Cesalpiniaceae, Anacardiaceae, Apogynaceae, Meliaceae, Combretaceae and Tiliaceae have been the most cited as appetite suppressant/anti-obesity plants (Figure 6). Raphionacme daronii (F = 25.4%), Gardenia erubescens (F = 20.3%), Brachystelma bingeri (F = 15.3%), Commiphora africana (F = 11.9%), Leptadenia hastata (F = 10. 2%), Balanites aegyptiaca (F = 10.2%) are the six species with the highest frequencies of use.

Figure 6.

Cited plant families.

3.2. Discussion

The survey has allowed identifying 62 species of plants which have anorectic and/or anti-obesity activity. Most interviewees were men; female healers or hunters are rare in these provinces. In Africa these activities are mainly the responsibility of men and the knowledge is transmitted very often from father to son. The 62 species listed have already been studied for some properties (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pytocemistry and pharmacoloy of plants cited.

| Species and family | Wild or Cultivated Status | Availability Information/Threat Status | Phytochemistry | Pharmacological properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Acacia laeta Benth. (Fabaceae) | wild | available species | carbohydrate [13] | anti microbial activity [14] |

| 2. Acacia nilotica(L.) Delile (Fabaceae) | wild | available species | alkaloids, glycosides, anthraquinones, cardiac glycosides [15] | antiplasmodial activity [16], antidiabetic activity [17] |

| 3. Acacia senegal (L.) Willd. (Fabaceae) | wild | available species | alkaloids, glycosides, flavonoids [18] | antidiabetic activity [19] hepatoprotective activity [20] |

| 4. Acacia seyal Del. (Fabaceae) | wild | available species | proteins, phenolics, flavonoids and anthocyanin [13] | antibacterial activities [21] |

| 5. Adansonia digitata L. (Bombacaceae) | wild | threatened species | protein, carbohydrate, fat, fibre, ash, vitamin C, A [22] | antidiarrhoeal activity [23],anti-tumor action [24] |

| 6. Afzelia africana Smith ex Pers. (Fabaceae) | wild | threatened species | lipide, carbohydrate [25] alkaloids [26] | antidiabetic and haematological effect [27] anthelmintic effect [26] |

| 7. Annona senegalensis Pers. (Annonaceae) | wild | available species | rutin, quercetin, quercetrin, anonaïne, tannin glycosides, proteins [27] | anticonvulsant properties [28] |

| 8. Azadirachta indica A. Juss. (Meliaceae) | wild/cultivated | available species | reducing sugar, glycosides, alkaloids, tannins, flavonoids, terpenoids, saponin [29] | antibacterial activity [29] |

| 9. Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile (Balanitaceae) | wild | available species | galactose, mannose, arabinose, xylose, rhamnose [30]; alkaloids, flavonoids [31]; saponoside steroidal [32] | anti-tumor activity [33] |

| 10. Bauhinia rufescens Lam. (Fabaceae) | wild | available species | carbohydrate, crude fibre, crude proteins cyanogenic glucoside [34] menisdaurin, oxepin [35] | antibacterial effects [34] |

| 11. Boscia angustifolia A. Rich. (Capparaceae) | wild | threatened species | alkaloids and saponins [36] | antibacterial activity [36] |

| 12. Brachystelma bingeri A.Chev. (Asclepiadaceae) | wild | threatened species | saponins, triterpens, sterols [37] | treatment of insufficient sperm, male sexual asthenia, as tonicorstimulant [37] |

| 13. Cadaba farinosa Forsk. (Capparidaceae) | wild | available species | cadabicine [38] | |

| 14. Ceratotheca sesamoides Endl. (Pedaliaceae) | wild/cultivated | available species | flavonolignans, triterpene saponins, isoflavones, triterpenoids [37] and phenylpropanoid lignan [39] | antiplasmodial activity [40] |

| 15. Ceropegia senegalensis H. (Apocynaceae) | wild | available species | ||

| 16. Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. (Cucurbitaceae) | wild/cultivated | available species | β-sitosterol [41] | antidiabetic effect [42] analgesic activities [43] |

| 17. Citrus aurantifolia (Christm.) Swingle (Rutaceae) | cultivated | available species | 5-geranyloxypsoralen; 5-geranyloxy-7-methoxycoumarin; 5,7-dimethoxycoumarin; 5-methoxypsoralen; and 5,8-dimethoxypsoralen [44] | anti-cancer activity [45], anti-mycobacterium tuberculosis activity [44] |

| 18. Cochlospermum planchonii Hook. f. ex Planch. (Cochlospermaceae) | wild | available species | cardiac glycosides, cardenolides and dienolides, alkaloids, steroids, and tannins, flavonoid, phlobatannins [46] | anti-ulcerogenic activity [47] |

| 19. Cochlospermum tinctorium Perrier ex A.Rich. (Cochlospermaceae) | wild | available species | alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins and cardiac glycoside [48] | antimicrobial activity [49], hepatoprotective activity [50] |

| 20. Combretum micranthum G. Don. (Combretaceae) | wild | threatened species | epicatechin and catechin as penta-acetates; epigallocatechin, gallocatechin and bartogenic acid 28-β-d-glucoside [51] | antihyperglycaemic activity [52], antibacterial [53] |

| 21. Commiphora africana (A. Rich.) Endl. (Curceraceae) | wild | threatened species | cardiac glycosides [54]; α-oxobisabolene [55] | antimicrobial activity [54] |

| 22. Cordia africana Lam. (Boraginaceae) | wild | available species | alkaloids, flavonoids, total phenols and tannins [56] | antibacterial activities [57]) |

| 23. Detarium microcarpum Guill. et Perr. (Fabaceae) | wild | threatened species | phenols, flavonoids, saponins, triterpenes/steroids and glycosides [58] | against hepatitis c virus [59] |

| 24. Digitaria exilis (Kippist) Stapf (Poaceae) | wild | available species | apigenin and luteolin [60] | postprandial hyperglycemia [61] |

| 25. Dioscorea bulbifera L. (Dioscoreaceae) | cultivated | available species | carbohydrates, proteins, amino acids, fats, oils, steroids, glycosides, alkaloids, tannins and phenolics [62] | antifungal actions [63] antibacterial activities [64] |

| 26. Diospyros mespiliformis Hochst. ex A.DC (Ebenaceae) | wild | threatened species | flavonoids [65] | antipyretic, analgesic and anti-inflammatory [66] |

| 27. Entada africana Guill et Perr. (Fabaceae) | wild | available species | alkaloids, saponins, flavonoids, glycosides, anthraquinone, terpenes, phenols, resins and saponins [67] | anti-angiogenic activity [68] anti-hepatitis C [69] |

| 28. Fadogia agrestis Schweinf. ex Hiern (Rubiaceae) | wild | available species | monoterpene glycosides [70] | analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects [71] antidiabetic [72] |

| 29. Ficus sycomorus L. (Moraceae) | wild | available species | tannins, alkaloids, reducing compounds, saponins, flavonoids, steroid, terpenoids and anthracenoside [73] | sedative and anticonvulsant effects [74] |

| 30. Gardenia aqualla Stapf & Hutch (Rubiaceae) | wild | available species | flavonoids, phytosterols, phenolics, carbohydrates, tannins, triterpenoids, antraquinone [75] | anticancer activities [76] antimicrobial activity [75] |

| 31. Gardenia erubescens Stapf & Hutch (Rubiaceae) | wild | threatened species | fibers [77] anthraquinons, tannins, sterols and triterpens. [78] | analgesic and diuretic activity. [79]. |

| 32. Grewia bicolor Juss. (Tiliaceae) | wild | available species | β-sitosterol, triterpene ester, triterpenes lupeol and betulin, beta-sitosterol glucoside, harmane, 6-methoxyharmane and 6-hydroxyharmane [80] | anticonvulsant and anxiolytic properties [81] |

| 33. Grewia flavescens Juss. (Tiliaceae) | wild | available species | flavonoids, phytosterols, phenolics, carbohydrates, tannins, triterpenoids [82] | anti-diabetic [82] |

| 34. Grewia villosa Willd. (Tiliaceae) | wild | triterpenoids, steroids, glycosides, flavones, lignanes, phenolics, alkaloids, lactones [83] | anti-bacterial and analgesic effect [83] | |

| 35. Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (Malvaceae) | cultivated | available species | alkaloids, tannins, saponnins, glycosides, phenols and flavonoids, glycosides [84] | diuretic activity [85] anti-obesity effects [86] |

| 36. Holarrhena floribunda (G.Don) T.Durand & Schinz var. florinbunda (Apocynaceae) | wild | available species | fat, fiber, protein, carbohydrates, alkaloid, saponin, tannin and cardiac glycosides [87] | hypoglycaemic activity [88] |

| 37. Hyphaene thebaica (L.) Mart (Arecaceae) | available species | tannins, steroids and moderate level of saponins, carbohydrates, cardiac glycosides, flavonoids, and terpinoids [89] | antimicrobial properties [90] hypoglycaemic properties [89] | |

| 38. Khaya senegalensis (Desv.) A.Juss. (Meliaceae) | wild | threatened species | alkaloids, saponins, tannins and flavonoids [91] | hepatoprotective activity [92] |

| 39. Lannea microcarpa Engl. & K. Krause (Anacardiaceae) | wild | threatened species | anthocyanosides [93] 4α-methoxy-myricetin 3-α-l-rhamnopyranoside, myricetin 3-α-l-rhamnopyranoside, myricetin 3-β-d-glucopyranoside, vitexin, isovitexin, gallic acid and epi-catechin [94] | anti-inflammatory activities [95] |

| 40. Leptadenia hastata Vatke (Asclepiadaceae) | wild | available species | d-cymarose and d-oleandrose [96]. tannins, glycosides, alkaloids, flavonoids. [97] | diabetes [96] antibacterial activity [98] anti-androgen property [99]. |

| 41. Mitragyna inermis (Willd.) Kuntze (Rubiaceae) | wild | available species | sterol, triterpene, polyphenol, flavonoïd, catechic tannin, saponoside and alkaloid [100] | anticonvulsant properties [101] hepatoprotective activity [102] |

| 42. Moringa oleifera Lam (Moringaceae) | cultivated | available species | glucose, fructose [103] | antiobesity and hypolipidemic activity [104] |

| 43. Ozoroa insignis Del. (Anacardiaceae) | wild | available species | methyl 3α,24S-dihydroxytirucalla-8,25-dien-21-oate; methyl 3α-hydroxy-24-oxotirucalla-8,25-dien-21-oate [105] | antimicrobial activity, cytoprotective effect [106] |

| 44. Panicum laetum Kunth (Poaceae) | wild | available species | proteins, carbohydrates [107] | |

| 45. Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.) G.Don (Fabaceae) | wild | threatened species | cardiac glycosides, steroids, tannins and alkaloids [108] | antiplasmodial activities [109] the antisnake venom activities [110] |

| 46. Phoenix dactylifera L. (Arecaceae) | wild | available species | carbohydrate, vitamins, proteins [111] | nephroprotective, antibacterial, antidiabetic activities [111] |

| 47. Pseudocedrela kotschyi (Schweinf.) Harms (Meliaceae) | wild | available species | tannins, saponins [112] | nephroprotective activities [113] |

| 48. Raphionacme daronii Berhaut (Asclepiadaceae) | wild | available species | sugars and starch [114]. | |

| 49. Saba senegalensis (A.DC.) Pichon var. senegalensis (Apocynaceae) | wild | threatened species | malic acid, protein, vitamin c [115], tannins, flavonoids, saponins, coumarins, anthocyanosides, triterpenes and sterols [116] | anti-inflammatory, analgesic effect [116] |

| 50. Sarcocephalus latifolius (Sm.) E.A.Bruce (Rubiaceae) | wild | available species | 21-O-ethylstrictosamide aglycone, strictosamide, angustine, nauclefine, angustidine, angustoline, 19-O-ethylangustoline, naucleidinale, 19-epi-naucleidinale [117] | anti-microbial activities [118] |

| 51. Sclerocarya birrea (A. Rich.) Hochst. (Anacardiaceae) | wild | available species | cellulose, proteins, [119] anthocyanins, flavonoids, tannins, saponins [120] | hypoglycemic activity [121] |

| 52. Sterculia setigera Delile (Sterculiaceae) | wild | threatened species | saponins, steroidal, sterols and flavonoids [122] | antiplasmodial, anti-inflammatory activity [123] |

| 53. Strychnos spinosa Lam. Lam (Loganiaceae) | wild | available species | saringosterol and 24-hydroperoxy-24-vinylcholesterol [124] | antitrypanosomal activity [125] |

| 54. Tamarindus indica L. (Fabaceae) | wild | threatened species | 9β, 19-Cyclo-4 β4, 4, 14, x-trimethyl-5α-cholestan-3β-ol, 24R-Ethyl cholest-5-ene [126] | antiobesity effect [127] |

| 55. Terminalia avicennioides Guill. & Perr. (Combretaceae) | wild | available species | steroids, glycosides, flavonoids, tannins, ellagic acids arjunolic acid, α-amyrin, 2,3,23-trihydroxylolean-12-ene [128] | antimycobacterial activty [128] |

| 56. Terminalia macroptera Guill. & Perr. (Combretaceae) | wild | threatened species | 3,3’di-O-methylellagic acid, 3,4,3’,4’-tetra-O-methylellagic acid, terflavine A [129] | anti-helicobacter pylori activity [130] |

| 57. Vernonia kotschyana Sch.Bip. ex Walp. (Astéraceae) | wild | threatened species | arabinogalactane pectin [131], vernoniosides D1, D2, D3, F1 and F2 and a new androst-8-ene glucoside [132] | antiulcer activity [133] |

| 58. Vitellaria paradoxa C.F.Gaertn. (Sapotaceae) | wild/cultivated | threatened species | anthocyanins, flavonoids, catechol tannins, saponins [134] | emmenagogue [134] |

| 59. Vitex doniana Sweet (Verbenaceae) | wild | threatened species | flavonoids, anthracene derivatives, essential oil, pigments, tannins, terpenes glycosides, triterpenes [135] | antimicrobial activities [136] |

| 60. Ximenia americana L. (Olacaceae) | wild | threatened species | triterpen (mediagenic acid; oleanen glucoside) and steroidal compounds (6–7 hydrositosteron;sitosteroside) [137] | antimicrobial, antitrypanosomal, molluscicide and analgesic [137] |

| 61. Xysmalobium heudelotianum Decne. (Asclepiadaceae) | wild | threatened species | ||

| 62. Zizyphus mauritiana Lam. (Rhamnaceae) | wild | threatened species | tannins, sterols and triterpenes, flavonoids, leucoanthocyanins [138] | anti hyperglycemic activities, antihypertensive, and diuretic activity [139] |

Eight species, namely Leptadenia hastata, Balanites aegyptiaca, Zizyphus mauritiana, Tamarindus indica, Khaya senegalensis, Brachystelma bingeri, Azadirachta indica, and Adansonia digitata have been cited both in Nayala and Seno. So, these plants grow well in a Sahelian or in a Sudanian climate. In this study Raphionacme daronii (F = 25.4%), Gardenia erubescens (F = 20.3%), Brachystelma bingeri (F = 15.3%), Commiphora africana (F = 11.9%) Leptadenia hastata (F = 10.2%) and Balanites aegyptiaca (F = 10.16%) are the six species which have presented the highest frequency of citation and greater use value indexes in the group of appetite suppressant plants species. This indicates the importance given to these plants by these populations in the treatment of obesity or as an anorectic.

Raw fresh material directly and decoctions are the two main forms of consumption. Anorectic or thirst quenching plants are usually eaten raw as they are most often used to immediately remedy a situation of hunger or thirst. The preparations generally involve a single plant material, but sometimes mixtures can also be used. In the latter, a synergistic effect may be supposed [12].

There are some differences in the methods of preparation and parts of plants used according to each locality. For example, the decoction of bark and fruits of Tamarindus indica is used in Seno while the decoction of roots is used in Nayala. Also, fruits of Zizuphus mauritiana are prescribed as an appetite suppressant in both localities but the roots are used for weight loss in Seno.

According to the literature, Zizyphus mauritiana, Tamarindus indica and Moringa oleifera have previously been tested for anti-obesity activity [140,141,142]. This could be linked to a widespread use of these species in many regions for the same indication.

The most cited plants have already been studied for various activities:

Balan ites aegyptiaca is mainly consumed in dearth times by the population [143], and it contains carbohydrates, steroidal saponines, fiber, gum [37] alkaloids and flavonoids [32]. It also contains galactose, mannose, arabinose, xylose, rhamnose and glucuronic acid [31]. Their fruits are used against diabetes [30,144] as well as the seeds [145]. The plant is also known having anti-tumor activity [33] and an anti-infertility property [146].

Leaves of Leptadenia hastata are rich in tannins, glycosides, alkaloids, carbohydrates and flavonoids. [98]. d-Cymarose and d-oleandrose were also isolated [97]. They are used against diabetes 97] and supposed havingantibacterial activity [98] and anti-androgen property [99].

Commiphora africana contains cardiac glycosides and reducing sugars [147]. It has antimicrobial activity and is traditionally used against diarrhea [54].

Fruit and young leaves of Gardenia erubescens are consumed during dearth periods [148]. These fruits contain carbohydrates and fibers [149] and they are also rich in anthraquinones, tannins, sterols and triterpenes [77]. The leaves contain tannins, triterpene saponins, other triterpenoids, iridoids and sterols. The bark is rich in triterpene saponins, triterpenoids and sterols [37]. The leaves are used for the treatment of digestive parasites in small ruminants [78] and the bark of the trunk has analgesic and diuretic activity [79].

Gardenia erubescens is traditionally used against hepatitis [150].

Raphionacme daronii is a plant used during times of famine; it is eaten raw [148,151]. The tuber contains sugars and starch [114].

The tuber of Brachystelma bingeri is used against insufficient sperm and male sexual asthenia, and it is very nutritious, stimulating and can act as a tonic [37]. It is consumed during famine periods [143] and is rich in carbohydrates, saponins, triterpenes and sterols [37].

The most cited plants listed during the survey have not been investigated for an anti-obesity study. So, there is a need to test their bioactivity and eventually study the phytochemistry and pharmacological profile of these plants in order to scientifically support traditional ethnobotanical and to secure their use.

4. Conclusions

The ethnobotanical survey revealed the presence of an enormous biodiversity of plants used in these two north provinces of Burkina Faso to modulate appetite and thirst. This rich ethnobotanical background indicates the high potential of traditional knowledge to serve for the development of natural product-derivates as affordable medicines. This may contribute to the preservation of traditional knowledge on anti-obesity herbs of these two provinces of Burkina Faso. Twenty-two species cited are in fragile state or are threatened with extinction. This requires taking safeguard measures. It is therefore useful to study the ecology of these species, evaluate the resources and the natural regeneration potential. Reforestation with these species requires the mastery of the production of seeds and planting in areas of high use. This is an important endeavour that could help to fight against the massive destruction of these plants, in the context of climate change and the unprecedented human pressure on the environment. Investigation into these six most cited and not yet studied species could lead to the discovery of new products to address the obesity epidemic.

Acknowledgments

the authors would liket to thank Dr. Willibald Schliemann for his assistance and advices for the paper language improvement.

Author Contributions

A.H. conceived and designed the project and D.P. performed the fieldwork survey. For data analysis D.P., A.H., S.G. and N.O. contributed. For the paper design D.P. and A.H. contributed. For the paper reading and improving D.P., A.H., S.G. and N.O. contributed.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zabsonre P., Sedogo B., Lankoande D., Dyemkouma F.X. Obésité et maladies chroniques en Afrique sub-saharienne. Méd. Afr. Noire. 2000;47:5–9. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lien D.N., Quynh N.T., Quang N.H., Phuc D.V., Thi N., Ngan T. Anti-obesity and body weight reducing effect of Fortunella japonica peel extract fractions in experimentally obese mice. KKU Sci. J. 2009;37:96–104. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wennert A.L. These de doctorat. Université de Lorraine; France: 2012. Hoodia gordonii (Masson) Sweet ex Decne : Une plante d’Afrique du Sud, de son utilisation traditionnelle vers un éventuel avenir thérapeutique. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jorge C., Zoltan P., Alain G. Comprendre l’obésité en Afrique: Poids du développement et des représentations. Rev. Med. Suisse. 2014:712–716. (In French) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claire C., Ludivine M., Alina R., Charles B., Marion B., Sébastien C. Traitement pharmacologique de l’obésité, Médecine. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabète. 2012;61:1–12. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu-Hao Z., Xiu-Qiang M., Cheng W., Jian L., Shan-Shan Z., Jia G., Shun-Quan W., Xiao-Fei Y., Jin-Fang X., Jia H. Effect of anti-obesity drug on cardiovascular risk factors: A Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kazemipoor M., Radzi C.J., Cordell G.A., Yaze I. Potential of traditional medicinal plants for treating obesity: A review. Int. Conf. Nutr. Food Sci. 2012;39:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.INSD . Annuaire Statistique 2007 de la Region du sahel. INSD; Sahel, Burkina Faso: 2008. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 9.MATD . Plan communal de developpement de. Dori 2009–2013, Rapport de la commune de Dori. MATD; Dori, Burkina Faso: 2013. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jean P.K. Les technologies appropriées en zone rurale: Cas du moulin à grains. Université catholique d'Afrique Centrale Yaoundé; Cameroun: 2000. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarr O., Bakhoum A., Diatta S., Akpo L. L’arbre en milieu soudano-sahélien dans le bassin arachidier (Centre-Sénégal) J. Appl. Biosci. 2013:4515–4529. doi: 10.4314/jab.v61i0.85598. (In French) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rainer W.B., Douglas S. Traditional medicinal plant use in Northern Peru: Tracking two thousand years of healing culture. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006;2:1–47. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdel-Farid I.B., Sheded M.G., Mohameda E.A. Metabolomic profiling and antioxidant activity of some Acacia species. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2014;21:400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahmoud F.M., Sulaiman Abdullah A., Abd El-Latif H. Biological activities of some Acacia spp. (Fabaceae) against new clinical isolates identified by ribosomal RNA gene-based phylogenetic analysis. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016;29:221–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deshpande S.N. Preliminary phytochemical analysis and in vitro investigation of antibacterial activity of acacia nilotica against clinical isolates. J. Pharm. Phytochem. 2013;1:23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farzana M.U.Z.N., al Tharique I., sultana A. A review of ethnomedicine, phytochemical and pharmacological activities of Acacia nilotica (Linn) willd. J. Pharm. Phytochem. 2014;3:84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mwangi J.M., Ngugi M.P., Njagi E.M., Njagi J.M., Agyirifo S.D., Gathumbi K.P., Muchugi N.A. Antidiabetic effects of aqueous leaf extracts of Acacia nilotica in alloxan induced diabetic mice. J. Diabetes Metab. 2015;6:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okoro S.O., Kawo A.H., Arzai A.H. Phytochemical screening, antibacterial and toxicological activities of Acacia senegal extracts. Bayero J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2012;5:163–170. doi: 10.4314/bajopas.v5i1.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rishi P., Hooda M.S., Bhandari A., Singh J. Antidiabetic activity of Acacia senegal pod extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Indig. Med. Plants. 2013;46:1400–1404. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rishi P., Mangal S.H., Chain S.B., Janardhan S. Hepatoprotective activity of Acacia senegal pod against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2014;26:165–168. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eldeen I.M.S., Van Staden J. In vitro pharmacological investigation of extracts from some trees used in Sudanese traditional medicine. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2007;73:435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2007.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eke M.O., Olaitan N.I., Sule H.I. Nutritional evaluation of yoghurt-like product from baobab (Adansonia digitata) fruit pulp emulsion and the micronutrient content of baobab leaves. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013;5:1266–1270. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdelrahim M.Y., Elamin B.M.A., Khalil D.J.K., el Badwi S.M.A. Antidiarrhoeal activity of ethanolic extract of Adansonia digitata fruit pulp in rats. J. Phys. Pharm. Adv. 2013;3:172–178. doi: 10.5455/jppa.20130624013026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fahmy G.E. The effect of seeds and fruit pulp of Adansonia digitata L. (Baobab) on Ehrlich ascites carcinoma. Food Nutr. Sci. 2013;4:38–46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Igwenyi I.O., Azoro B.N. Proximate and phytochemical compositions of four indigenous seeds used as soup thickeners in ebonyi state Nigeria. J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 2014;8:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon M.K., Nafanda W.D., Obeta S.S. In-vivo evaluation for anthelmintic effect of alkaloids extracted from the stem bark of afzelia africana in rats. J. Adv. Sci. Res. 2012;3:100–104. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oyedemi S.O., Adewusi E.A., Aiyegoro O.A., Akinpelu D.A. Antidiabetic and haematological effect of aqueous extract of stem bark of Afzelia africana (Smith) on streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats. Asian Pac. J Trop Biomed. 2011;1:353–358. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60079-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konate A., Sawadogo W.R., Dubruc F., Caillard O., Ouedraogo M., Guissou I.P. Phytochemical and Anticonvulsant Properties of Annona senegalensis Pers. (Annonaceae), plant used in Burkina folk medicine to treat epilepsy and convulsions. Br. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2012;3:245–250. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vinoth B., Manivasagaperumal R., Rajaravindran M. phytochemical analysis and antibacterial activity of azadirachta indica a juss. Int. J. Res. Plant Sci. 2012;2:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samir A.M.Z., Somaia Z.A.R., Mattar A.F. Anti—Diabetic properties of water and ethanolic extracts of Balanites aegyptiaca fruits flesh in senile diabetic rats. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2003;10:90–108. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bekaa R.G., Guiamaa V.D., Delmont A., Donna P., Slomiannyc M.C., Libougaa D.G., Mbofunga C.M., Guillochonb D., Vercaigne-Marko D. Glycosyl part identified within Balanites aegyptiaca fruit protease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011;49:397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daya L.C., Vaghasiya H.U. A review on Balanites aegyptiaca Del (desert date): Phytochemical constituents, traditional uses, and pharmacological activity. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2011;5:55–62. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.79100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-ghannam S.M., Ahmed H.H., Zein N., Zahran F. Antitumor activity of balanitoside extracted from Balanites aegyptiaca fruit. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2013;3:179–191. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Usman H., Abdulrahman F.I., Kaita A.H.A., Khan I.Z. Proximate and elemental composition of Bauhinia rufescens Lam (Leguminosae: Caesalpiniaceae) Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2011;5:1746–1753. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aminu M., Hasnah M.S. Cox-2 inhibitors from stem bark of bauhinia rufescens lam. (Fabaceae) EXCLI J. 2013;12:824–830. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassan S.W., Umar R.A., Lawal M., Bilbis L.S., Muhammad B.Y., Dabai Y.U. Evaluation of antibacterial activity and phytochemical analysis of root extracts of Boscia angustifolia. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2006;5:1602–1607. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nacoulma O.G. Plantes médicinales et Pratiques médicinales Traditionnelles au Burkina. Université de Ouagadougou; Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso: 1996. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmad V.U., Amber A.U.R. Cadabicine, an alkaloid from cadada farinosa. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:2709–2712. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)80700-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bedigian D., Adetula O.A. Ceratotheca Sesamoides Endl. [(accessed on 14 October 2015)]. Available online: http://www.prota4u.org/search.asp. (In French)

- 40.Benoit-Vical F., Soh P.N., Saléry M., Harguem L., Poupat C., Nongonierma R. Evaluation of Senegalese plants used in malaria treatment: Focus on Chrozophora senegalensis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008;116:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Namama S.T., Diary I.T. Citrullus colocynthis as a bioavailable source of beta-sitosterol, anti hyperlipidic effect of oil in rabbits. Int. J. Med. Arom. Plants. 2012;2:536–539. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jayaraman R., Shivakumar A., Anitha T., Joshi V.D., Palei N.N. Antidiabetic effect of petroleum ether extract of citrullus colocynthis fruits against streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemic rats. Rom. J. Biol. Plant Biol. 2009;54:127–134. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marzouka B., Marzoukb Z., FEninab N., Bouraouic A., Aounia M. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of Tunisian Citrullus colocynthis Schrad. Immature, fruit and seed organic extracts. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011;15:665–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sandoval-Montemayor N.E., García A., Elizondo-Treviño E., Garza-González E., Alvarez L., Camacho-Corona M.D.R. Chemical composition of hexane extract of Citrus aurantifolia and anti-mycobacterium tuberculosis activity of some of its constituents. Molecules. 2012;17:11173–11184. doi: 10.3390/molecules170911173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arias B.A., Ramon-Lacab L. Pharmacological properties of citrus and their ancient and medieval uses in the Mediterranean region. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olugbemiro M., Akanji, Adewumi M. Phytochemical and mineral constituents of Cochlospermum planchonii (Hook. f. ex Planch) Root. Biores. Bull. 2013;2:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ezeja M.I., Aruh O., Anaga A.O. Anti-ulcerogenic activity of the methanol root bark extract of Cochlospermum planchonii (Hook f) Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2013;10:394–400. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i5.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tijjani M.B., Bello I.A., Aliyu A.B., Olurishe T., Maidawa S.M., Habila J.D., Balogun E.O. Phytochemical and antibacterial studies of root extract of Cochlospermum tinctorium A. Rich. (Cochlospermaceae) Res. J. Med. Plants. 2009;3:16–22. doi: 10.3923/rjmp.2009.16.22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Magaji M.G., Shehu A., Sani M.B., Musa A.M., Yaro A.H., Ahmed T.S. Biological activities of aqueous methanol leaf extract cochlospermum tinctorium A. Rich. Niger. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;9:36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akinloye O.A., Ayankojo A.G., Olaniyi M.O. Hepatoprotective activity of cochlospermum tinctorium against carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity in rats. ROM. J. Biochem. 2012;49:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Umar H.D., Abdurahman E.M., Ilyas N., Agunu A. Phytochemical constituents of the root of Combretum micranthum G. Don (family: Combretaceae) Planta Med. 2011;77:1–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1282492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chika A., Bello S.O. Antihyperglycaemic activity of aqueous leaf extract of Combretum micranthum (Combretaceae) in normal and alloxan-induced diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;129:34–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Udoh I.P., Nworu C.S., Eleazar C.I., Onyemelukwe F.N., Esimone C.O. Antibacterial profile of extracts of Combretum micranthum G. Don against resistant and sensitive nosocomial isolates. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2012;2:142–146. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alexander W. Plantes médicinales et leur utilisation traditionnelle chez les paysans au Niger. Etudes flor. Veg. Burkina Faso. 2002;6:9–8. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marc A.A., Mansour M., Félix T., Joseph C. Identification par RMN du carbone-13 et par CPG/SM des principaux constituants des huiles essentielles des feuilles de xylopla aethloplca (dunal). richard et de commiphora africana (a. rich.) engl. du bénin. J. Soachim. 1997;29:1–35. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ganesan K., Letha N., Nair S.K.P., Gani S.B. Evaluation of phytochemical screening and in vitro antioxidant activity of Cordia africana Lam. (Family: Boraginaceae), a native african herb. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Sch. 2015;4:188–196. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tesfamaryam G., Tsegaye B., Eguale T., Wubete A. In vitro screening of antibacterial activities of selected athiopian medicinal plants. Int. J. Microbiol. Res. 2015;6:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ebi G.C., Afieroho O.E. Phytochemical and antimicrobial studies on Detarium microcarpum Guill and Sperr (Caesalpinioceae) seeds coat. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011;10:457–462. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olugbuyiro J.A.O., Moody J.O., Hamann M.T. Inhibitory activity of Detarium microcarpum extract against hepatitis C virus. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2009;12:150–151. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sartelet H., Serghat S., Lobstein A., Ingenbleek Y., Anton R., Petitfrkre E., Aguie-aguie G., Martiny L., Haye B. Flavonoids extracted from fonio millet (Digitaria exilis) reveal potent antithyroid properties. Nutrition. 1996;12:100–106. doi: 10.1016/0899-9007(96)90707-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okonji R.E., Akinwunmi K.F., Madu J.O., Bamidele F.S., Funmilola A. In Vitro study on α-amylase inhibitory activities of Digitaria exilis, Pentadiplandra brazzeana (Baill) and Monodora myristica. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2014;8:2306–2313. doi: 10.4314/ijbcs.v8i5.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malode U.G., Mohammad N., Quazi S.A., Mahajan D.T., Masand V. Phytochemical investigations of Dioscorea bulbifera linn. Indian J. Res. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2015;3:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eleazu C.O., Kolawole S., Awa E. Phytochemical composition and antifungal actions of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the peels of two yam varieties. Med. Aromat. Plants. 2013;2:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuete V., Betrandteponno R., Mbaveng A.T., Tapondjou L.A., Meyer J.J., Barboni L., Lall N. Antibacterial activities of the extracts, fractions and compounds from Dioscorea bulbifera. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lamien-Meda A., Lamien C.E., Compaoré M.M.Y., Meda R.N.T., Kiendrebeogo M., Zeba B., Millogo J.F., Nacoulma O. Polyphenol content and antioxidant activity of fourteen wild edible fruits from Burkina Faso. Molecules. 2008;3:581–594. doi: 10.3390/molecules13030581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adzu B., Amos S., Dzarma S., Muazzam I., Gamaniel K.S. Pharmacological evidence favouring the folkloric use of Diospyros mespiliformis Hochst in the relief of pain and fever. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002;82:191–195. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ifemeje J.C., Egbuna C., Udedi S.C., Iheukwumere H.I. Phytochemical and in vitro antibacterial evaluation of the ethanolic extract of the stem bark of Entada africana Guill. & Perr and Sarcocephalus latifolus. Int. J. Biochem. Res. Rev. 2014;4:584–592. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Germanò M.P., Certo G., D'Angeloa V., Sanogo R., Malafronted N., de Tommasid N., Rapisarda A. Anti-angiogenic activity of Entada africana root. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015;29:1551–1556. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2014.987773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Galani Tietcheu B.R., Sass G., Njayou N.F., Mkounga P., Tiegs G., Moundipa P.F. Anti-hepatitis C virus activity of crude extract and fractions of Entada africana in genotype 1b replicon systems. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2014;42:853–868. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X14500542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anero R., Dıaz-Lanza A., Ollivier E., Baghdikian B., Balansard G., Bernabe M. Monoterpene glycosides isolated from Fadogia agrestis. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:805–811. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oyekunle O.A., Okojie A.K., Udoh U.S. Analgesic and anti-Inflammatory effects of an extract of Fadogia agrestis in rats. Neurophysiology. 2010;42:147–152. doi: 10.1007/s11062-010-9140-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Musa T.Y., Olalekan B.O. Effects of aqueous extract of Fadogia agrestis stem in alloxaninduced diabetic rats. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2014;9:356–363. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zaku S.G., Abdulrahaman F.A., Onyeyili P.A., Aguzue O.C., Thomas S.A. Phytochemical constituents and effects of aqueous root-bark extract of Ficus sycomorus L. (Moraceae) on muscular relaxation, anaesthetic and sleeping time on laboratory animals. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009;8:6004–6006. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sandabe U.K., Onyeyili P.A., Chibuzo G.A. Sedative and anticonvulsant effects of aqueous extract of Ficus sycomorus L. (Moraceae) stembark in rats. Vet. Arhiv. 2003;73:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Njina N.S., Sale M.I., Pateh U.U., Hassan H.S., Usman M.A., Bilkisa A., Danja B.A., Ache R.N. Phytochemical and anti-microbial activity of stem-bark of Gardenia Aqualla Stapf et Hutch (Rubeaceae) J. Med. Plant Res. 2014;8:942–946. doi: 10.5897/JMPR2013.5207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tagne R.S., Telefo B.P., Nyemb J.N., Yemele D.M., Njina S.N., Goka S.M.C., Lienou L.L., Kamdje A.H.N., Moundipa P.F., Farooq A.D. Anticancer and antioxidant activities of methanol extracts and fractions of some Cameroonian medicinal plants. Asian Pac. J. Trop Med. 2014;7:442–447. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kini F., Saba A., Ouedraogo S., Tingueri B., Sanou G., Guissou I.P. Potentiel Nutritionnel Et Therapeutique De Quelques Especes Fruitieres Sauvages Du Burkina Faso. Pharm. Méd. Tradit Afr. 2008;15:32–35. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kabore A., Tamboura H.H., Adrien M.G.B., Traore A. Traitements ethno-vétérinaires des parasitoses digestives des petits ruminants dans le plateau central du Burkina Faso. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2007;1:297–304. doi: 10.4314/ijbcs.v1i3.39711. (In French) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hussain M.M., Sokomba E.N., Shok M. Pharmacological effects of Gardenia erubescens in mice, Rats and Cats. Pharm. Biol. 1991;29:94–100. doi: 10.3109/13880209109082857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jaspers M.W., Bashir A.K., Zwaving J.H., Malingré T.M. Investigation of Grewia bicolor Juss. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986;17:205–211. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shamoun M.I., Mohamed A.H., El-Hadiyah T.M. Anticonvulsant and anxiolytic properties of the roots of Grewia bicolor in rats. Sudan JMS. 2014;9:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rama M.R.M., Yanadaiah J.P., Ravindra R.K., Lakshman K.D., Balamuralidhar H. Assessment of antidiabetic activity of ethanol extract of grewia flavescens juss leaves against alloxan induced diabetes in rats. J. Glob. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2013;4:1086–1090. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Goyal P.K. Phytochemical and pharmacological properties of the genus grewia: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2012;4:72–78. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Okereke C.N., Iroka F.C., Chukwuma M.O. Phytochemical analysis and medicinal uses of Hibiscus sabdariffa. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2015;2:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alarcón-Alonso J., Zamilpa A., Aguilar F.A., Herrera-Ruiza M., Tortoriello J., Jimenez-Ferrera E. Pharmacological characterization of the diuretic effect of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn (Malvaceae) extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;139:751–756. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.To-Wei H., Chia-Ling C., Erl-Shyh K., Jenq-Horng L. Effect of Hibiscus sabdariffa extract on high fat diet-induced obesity and liver damage in hamsters. Food Nutr. Res. 2015;59 doi: 10.3402/fnr.v59.29018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Badmus J.A., Odunola O.A., Obuotor E.M., Oyedapo O.O. Phytochemicals and in vitro antioxidant potentials of defatted methanolic extract of Holarrhena floribunda leaves. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010;9:340–346. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gnangoran B.N., N’guessan B.B., Amoateng P., Dosso K., Yapo A.P., Ehile E.E. Hypoglycaemic activity of ethanolic leaf extract and fractions of Holarrhena floribunda (Apocynaceae) J. Med. Biomed. Sci. 2012;1:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Auwal M.S., Tijjani A., Lawan F.A., Mairiga I.A., Ibrahim A., Njobdi A.B., Shuaibu A., Sanda K.A., Wakil A.M., Thaluvwa A.B. The quantitative phytochemistry and hypoglycaemic properties of crude mesocarp extract of Hyphaene thebaica (doum palm) on normoglycemic wistar albino rats. J. Med. Sci. 2012;12:280–285. doi: 10.3923/jms.2012.280.285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dosumu O.O., Nwosu F.O., Nwogu C.D. Antimicrobial studies and phytochemical screening of extracts of Hyphaene thebaica (Linn) Mart fruits. Int. J. Trop. Med. 2006;1:186–189. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Falodun A., Obasuyi O. Phytochemical screening and evaluation of stem bark extract of khaya senegalensis (meliaceae) on methicillin resistant staphyloccocus areus. Can. J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2009;3:925–928. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ali S.A.M., ElBadwi S.M.A., Idris T.M., Osman K.M. Hepatoprotective activity of aqueous extract of Khaya senegalensis bark in rats. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011;5:5863–5866. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Palé E. PhD Thesis. université de Ouagadougou; Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso: 1998. Contribution à l’étude des composes anthocyaniques des plantes: cas de l’Hibiscus sabdariffa, Lannea microcarpa, Vigna subterranea et Sorghum caudatum du Burkina Faso. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 94.Picerno P., Mencherini T., Della Loggia R., Meloni M., Sanogo R., Aquino R.P. An extract of Lannea microcarpa: Composition, activity and evaluation of cutaneous irritation in cell cultures and reconstituted human epidermis. JPP. 2006;58:981–988. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.7.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bationo J.H., Hilou A., Compaore M., Coulibaly Y.A., Kiendrebeogo M., Nacoulma O.G. Anti-inflammatory activities of fruit and leaves extract of lannea microcarpa england K. Kraus (anacardiaceae) Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015;7:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bello A., Aliero A.A., Saidu Y., Muhammad S. Hypoglycaemic and hypolipidaemic effects of Leptadenia hastata (Pers.) Decne in alloxan induced diabetic rats. Niger. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011;19:187–192. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rita A., Cosimo P., Nunziatina D.T., Francesco D.S. New polyoxypregnane ester derivatives from Leptadenia hastata. J. Nat. Prod. 1995;58:672–679. doi: 10.1021/np50119a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Abubakar S., Usman A.B., Ismaila I.Z., Aruwa G., Azizat S.G., Ogbadu G.H., Onyenekwe P.C. Nutritional and pharmacological potentials of Leptadenia hastata (Pers.) Decne. ethanolic leaves extract. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2014;2:51–55. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bayala B., Rubio-pellicer M.T., Zongo M., Malpaux B., Sawadogo L. Activité anti-androgénique de Leptadenia hastata (Pers.) Decne : Effet compétitif des extraits aqueux de la plante et du propionate de testostérone sur des rats impubères castrés. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2011;15:223–229. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 100.Konkon N.G., Adjoungoua A.L., Manda P., Simaga D., N’Guessan K.E., Kone B.D. Toxicological and phytochemical screening study of Mitragyna Inermis (Willd.) O ktze (Rubiaceae), anti-diabetic plant. J. Med. Plants Res. 2008;2:279–284. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Uthman G.S., Gana G., Zakama S. Anticonvulsant screening of the ethanol leaf extract of Mitragyna inermis (Willd) in mice and chicks. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 2013;4:1354–1357. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tarig H.A.B., Idris O.F., Khalid H.E., Samia H.A. Hepatoprotective activity of petroleum ether extract of Mitragyna inermis against carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity in albino rats. IJPR. 2015;5:328–331. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Compaoré W.R., Nikièma P.A., Bassolé H.I.N., Savadogo A., Mouecoucou J., Hounhouigan D.J., Traoré S.A. Chemical composition and antioxidative properties of seeds of Moringa oleifera and pulps of Parkia biglobosa and Adansonia digitata commonly used in food fortification in Burkina Faso. Curr. Res. J. Biol. Sci. 2011;3:64–72. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Souravh B., Guru S.S., Ramica S. Antiobesity and Hypolipidemic Activity of Moringa oleifera leaves against high fat Diet-induced obesity in rats. Adv. Biol. 2014;9 doi: 10.1155/2014/162914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yonghong L., Pedro A. Tirucallane triterpenes from the roots of Ozoroa insignis. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:1309–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Haule E.E., Moshi M.J., Nondo R.S., Mwangomo D.T., Mahunnah R.L. A study of antimicrobial activity, acute toxicity and cytoprotective effect of a polyherbal extract in a rat ethanol-HCl gastric ulcer model. BMC Res. 2012;5 doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nordeide M.B., Holm H., Oshaug A. Nutrient composition and protein quality of wild gathered foods from Mali. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 1994;45:275–286. doi: 10.3109/09637489409166168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ajaiyeoba E. Phytochemical and antibacterial properties of parkia biglobosa and parkia bicolor leaf extracts. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2002;5:125–129. doi: 10.4314/ajbr.v5i3.54000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Builders M., Wannang N., Aguiyi J. Antiplasmodial activities of Parkia biglobosa leaves: In vivo and In vitro studies. Ann. Biol. Res. 2011;2:8–20. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Asuzua I.U., Harvey A.L. The antisnake venom activities of Parkia biglobosa (Mimosaceae) stem bark extract. Toxicon. 2003;42:763–768. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ateeq K.M., Sunil S.D., Varun S.K., Santosh M.K. Phoenix dactylifera Linn. (Pind Kharjura) Int. J. Res. 2013;4:447–451. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kerharo J., Adam J.G. La Pharmacopée Sénégalaise Traditionnelle. Vigot Frères; Paris, France: 1974. p. 1007. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ojewale A.O., Adekoya A.O., Faduyile F.A., Yemitan O.K., Odukanmi A.O. Nephroprotective activities of ethanolic roots extract of Pseudocedrela kotschyi against oxidative stress and nephrotoxicity in alloxan-induced diabetic albino rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014;5:26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Grubben G.J.H., Denton O.A. Ressouurce vegetales de l’afrique tropicale 2. Légumes. PROTA; Wageningen, The Netherlands: 2004. p. 737. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 115.Boamponsem G.A., Johnson F.S., Mahunu G.K., Awiniboya S.F. Determination of biochemical composition of Saba senegalensis (Saba fruit) Asian J. Plant Sci. Res. 2013;3:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yougbaré-Ziébrou M.N., Ouédraogo N., Lompo M., Bationo H., Yaro B., Gnoula C., Sawadogo W.R., Guissou I.P. Activités anti-inflammatoire, analgésique et antioxydante de l’extrait aqueux des tiges feuillées de Saba senegalensis Pichon (Apocynaceae) Phytothérapie. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10298-015-0992-5. (In French) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Abreu P., Pereira A. New indole alkaloids from Sarcocephalus latifolius. Nat. Prod. Lett. 2000;15:43–48. doi: 10.1080/10575630108041256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yinusa I., George N.I., Ayo R.G., Rufai Y. Evaluation of the pharmacological activities of beta sitosterol isolated from the bark of sarcocephalus latifolius. Glob. J. Pure Appl. Chem. Res. 2015;3:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Muhammad S., Hassan L.G., Dangoggo S.M., Hassan S.W., Umar K.J., Aliyu R.U. Acute and subchronic toxicity studies of kernel extract of Sclerocarya birrea in rats. Sci. World J. 2011;6:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Belemtougri R.G., Constantin B., Cognard C., Raymond G., Sawadogo L. Effect of Sclerocarya birrea (A. Rich) Hochst (Anacardiaceae) leaf extract on calcium signalling in cultured rat skeletal muscle cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001;76:247–252. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Keita A., Mariko E., Haidara T.K. Etude de l'activite hypoglycemiante des feuilles de sclerocarya birrea (A. Rich) Hochst. (Anacardiaceae) Pharm. Méd. Trad. Afr. 1998;10:16–25. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- 122.Eromosele C.O., Paschal N.H. Characterisation and antiviscosity paramètrers of seed oil from wild plants. Bioresour. Technol. 2003;86:203–205. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(02)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Babalola I.T., Adelakun E.A., Wang Y., Shode F.O. Anti-TB activity of Sterculia setigera Del., leaves (Sterculiaceae) J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2012;1:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hoet S., Pieters L., Muccioli G.G., Habib-Jiwan J.-L., Fred R., Opperdoes F.R., Quetin-Leclercq J. Antitrypanosomal activity of triterpenoids and sterols from the leaves of Strychnos spinosa and related compounds. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:1360–1363. doi: 10.1021/np070038q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hoet S., Stevigny C., Herent M., Quetin-Leclercq J. Antitrypanosomal compounds from the leaf essential oil of Strychnos spinosa. Planta Med. 2006;72:480–482. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Khanzada S.K., Shaikh W., Sofia S., Kazi T.G., Usmanghani K., Kabir A., Sheerazi T.H. Chemical constituents of tamarindus indica L. medicinal plant in Sindh. Pak. J. Bot. 2008;40:2553–2559. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Khairunnuur F.A., Zulkhairi A., Azrina A., Norhaizan M.E., Rasadah M.A., Zamree M.S., Khairul K.A.K. Antiobesity effect of Tamarindus indica L. pulp aqueous extract in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. J. Nat. Med. 2012;66:333–334. doi: 10.1007/s11418-011-0597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Abdullahi M., Kolo I., Adebayo O.O., Joseph O.A., Majekodumi O.F., Joseph I.O. Isolation and elucidation of three triterpenoids and its antimycobacterial activity of Terminalia avicennioides. Am. J. Org. Chem. 2012;2:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Silva O., Gomes E.T., Wolfender J.L., Marston A., Hostettmann K. Application of high performance liquid chromatography coupled with ultraviolet spectroscopy and electrospray mass spectrometry to the characterisation of ellagitannins from Terminalia Macroptera roots. Pharm. Res. 2000;17:1396–1401. doi: 10.1023/A:1007598922712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Silva O., Viegas S., Mello-Sampayo C., Costa M.J.P., Serrano R., Cabrita J., Gomes E.T. Anti-helicobacter pylori activity of Terminalia macroptera root. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:872–876. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Nergard C.S., Matsumoto T., Inngjerdingen M., Inngjerdingen K., Hokputsa S., Harding S.E., Michaelsen T.E., Diallo D., Kiyohara H., Paulsena B.S., et al. Structural and immunological studies of a pectin and a pectic arabinogalactan from Vernonia kotschyana Sch. Bip. ex Walp. (Asteraceae) Carbohydr. Res. 2005;340:115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sanogo R., Germano M.P., De-Tommasi N., Pizza C., Aquino R. Novel Vernoniosides and androstane glycosides from Vernonia kotschyana. Phytochemistry. 1998;47:73–78. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(97)00477-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Germano M.P., Pasqualea R., Iauk L., Galati E.M., Keita A., Sanogo R. Antiulcer activity of Vernonia kotschyana sch. bip. Phytomedicine. 1996;2:229–233. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(96)80047-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Koko I.K.E.D., Djego J., Gbenou J., Hounzangbe-adote S.M., Sinsin B. Etude phytochimique des principales plantes galactogènes et emménagogues utilisées dans les terroirs riverains de la Zone cynégétique de la Pendjari. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2011;5:618–633. doi: 10.4314/ijbcs.v5i2.72127. (In French) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Latifou L., Madjid A., Yann A., Ambaliou S. Antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant properties of Adansonia digitata and Vitex doniana from Bénin pharmacopeia. J. Pharmacogn. Phytother. 2012;4:44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ejikeme N., Henrietta O.U. Antimicrobial activities of leaf of vitex doniana and cajanus cajan on some bacteria. Researcher. 2010;2:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Francisco J.Q.M., Telma L.G., Monica R.S., Edilane S.G. Ximenia americana: Chemistry, pharmacology and biological properties, a review. Phytochemicals. 2010;20:430–450. [Google Scholar]