Abstract

Purpose:

Financial toxicity negatively affects patients with cancer, especially racial/ethnic minorities. Patient-oncologist discussions about treatment-related costs may reduce financial toxicity by factoring costs into treatment decisions. This study investigated the frequency and nature of cost discussions during clinical interactions between African American patients and oncologists and examined whether cost discussions were affected by patient sociodemographic characteristics and social support, a known buffer to perceived financial stress.

Methods

Video recorded patient-oncologist clinical interactions (n = 103) from outpatient clinics of two urban cancer hospitals (including a National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer center) were analyzed. Coders studied the videos for the presence and duration of cost discussions and then determined the initiator, topic, oncologist response to the patient’s concerns, and the patient’s reaction to the oncologist’s response.

Results:

Cost discussions occurred in 45% of clinical interactions. Patients initiated 63% of discussions; oncologists initiated 36%. The most frequent topics were concern about time off from work for treatment (initiated by patients) and insurance (initiated by oncologists). Younger patients and patients with more perceived social support satisfaction were more likely to discuss cost. Patient age interacted with amount of social support to affect frequency of cost discussions within interactions. Younger patients with more social support had more cost discussions; older patients with more social support had fewer cost discussions.

Conclusion:

Cost discussions occurred in fewer than one half of the interactions and most commonly focused on the impact of the diagnosis on patients’ opportunity costs rather than treatment costs. Implications for ASCO’s Value Framework and design of interventions to improve cost discussions are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Financial toxicity, the increased financial burden from cancer treatment and its influence on patient well-being, treatment decisions, and health outcomes, negatively affects many patients with cancer.1-5 As the cost of cancer care escalates6 and the burden of cost shifts to the patient,7-10 more patients are incurring debt,11 filing for bankruptcy,12 deviating from cancer treatment plans,1 and forgoing treatment.13 Recent evidence also suggests that severe financial distress as a result of cancer treatment may itself be a mortality risk factor.14

The encouragement of patients and physicians to discuss treatment costs may help to alleviate financial toxicity and facilitate more-informed treatment decisions.5,15-20 Such discussions are an opportunity for patients to voice cost concerns and for physicians to provide information about costs (if available) and to allow cost to factor into treatment decisions.2,5,15,17 In fact, clinicians increasingly have been encouraged to discuss treatment costs with patients as economic concerns grow.5,17,21

The data on patient-physician treatment cost discussions are inconsistent. Some studies show that patients want to discuss treatment costs with their physicians,22 and most physicians report that they frequently discuss cost with their patients.23 However, other research has found that physicians often are hesitant about initiating cost discussions24-26 and rarely fully engage with patients to resolve their financial concerns.27 Several studies suggest that discussions of treatment costs in patient-physician clinical interactions are rare.15,24-26,28,29

Given the potential importance of cost-related discussions in cancer care, this study systematically assessed the extent and nature of actual cost discussions that occur between a sample of African American patients and their oncologists. This study focused on African Americans because, on average, African Americans are more likely than whites to have low annual household incomes30 and, thus, may be at greater risk to incur economic hardship as a result of a cancer diagnosis.31-35 In addition, most African American patients with cancer experience racially discordant clinical interactions (ie, non–African American physician with African American patient),36 and a significant body of research has found that relative to racially concordant interactions, patient-physician communication in racially discordant interactions is of poorer quality.37-43

A secondary purpose of this study was to explore how certain patient characteristics affect cost discussions. Research has found that financial toxicity is an emotional stressor.3,4 Thus, patient perceptions of social support were examined because social support has been found to be a buffer to financial stress.44,45 Patients reported the amount of social support they received and their satisfaction with that social support. These aspects of social support are distinct and often have a variety of effects on how people react to environmental stressors.46,47 Given the likely association of patient age, education, and annual household income with patient finances, the influence of these sociodemographic characteristics on cost discussions was also examined. To answer the questions of interest in this study, real-time video-recorded patient-oncologist clinical interactions were analyzed for frequency and content of cost discussions.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

Data were from a larger parent study that tested a communication intervention in the outpatient clinics of two urban cancer hospitals.48-50 The two hospitals provide the largest proportion of cancer care for the residents of Detroit, Michigan, a city with a majority African American population. Data were collected between March 2012 and December 2014. The current study was a secondary analysis conducted after the parent study was completed.

Participants were African American patients with cancer and their non–African American medical oncologists. The oncologists and patients were meeting for the first time to discuss treatment options for breast, lung, or colorectal cancer. One clinical interaction for each patient was video recorded. The parent study focused on patient-oncologist communication; thus, patients and physicians did not know that cost discussions would subsequently be assessed.

Procedure and Measures

Upon recruitment into the parent study, patients and oncologists completed a baseline questionnaire that assessed demographic characteristics and other personal attributes. Patients provided information on their sociodemographic characteristics and perceived social support.46 Patients were presented with five social support domains, including dependability (eg, Whom can you really count on to be dependable when you need help?), help with relaxing, unconditional acceptance, unconditional care, and consolation. Patients reported the number of persons who provided them with social support in each domain and their level of satisfaction with the support received (1 = very dissatisfied to 4 = very satisfied). Responses were summed across items for each type of support and then averaged across the five domains to yield two scores for each patient. Higher scores indicate more perceived social support and greater satisfaction. Oncologists provided information on their sex, race/ethnicity, age, and number of years in practice since their fellowship.

As part of the larger study, patients were randomly assigned to three study arms: control group (usual care); those who received a question prompt list that contained questions patients might ask their oncologist; and those who received the question prompt list and met with a coach who reviewed the questions with them. Approximately 1 week later, patients and their oncologist met to discuss treatment options.48 Patients from all arms were included in this study, and each study arm was controlled for in all analyses.

Each examination room was equipped with unobtrusive digital audio and video devices that recorded all occupants of the examination room during the clinical interaction. This recording system has been used by the study team for more than 15 years,51,52 and research has strongly suggested that video recording has little impact on participants’ verbal or nonverbal behaviors53 and provides enhanced validity compared with audio recording alone.54

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the affiliated university and both hospitals. All patients, companions (if present), and oncologists provided consent as participants, which included specific permission to be video recorded.

Oncologist and Patient Interaction Coding

The first and senior authors watched 10 video-recorded clinical interactions from the data for examples of cost discussions to develop a coding system that identified and described cost discussions. Cost discussions were defined broadly24 as verbal expressions of any perceived monetary expense for the patient for cancer treatment. Topic categories for cost included out-of-pocket expenses for treatment, insurance coverage, transportation and parking for treatment, time off from work for treatment and recovery, and loss of employment.

Two trained research assistant coders then observed all the video-recorded interactions, (including those used to develop the coding system). The coders assessed the frequency and duration of cost discussions according to the aforementioned topic categories for cost by using observational coding software (Studiocode [www.studiocodegroup.com]; Vosaic, Lincoln, NE). Cost discussions were marked as beginning with the first mention of cost and ending with the first mention of either a noncost topic or a new cost topic. Both individual cost discussions and total clinical interaction time (total time the oncologist and patient were in the examination room together) were assessed to the nearest second. For each cost discussion, coders identified the initiator, topic, oncologist’s response to the patient’s concern, and how the patient reacted to the oncologist’s response.

Interrater reliability was assessed in two stages. First, the coders were trained to assess the presence and duration of the cost discussion; reliability was assessed by percentage of agreement (presence, 88.3%; duration, 83.8%). Second, the coders were trained to label discussion elements (initiator, topic, oncologist response, and patient reaction). Reliability was determined by Cohen κ (κ = 0.84; an average κ was taken across the coded elements). Because the high κ value suggested high intercoder reliability, each coder independently coded approximately 40% of the interactions. The remaining interactions were coded by both coders to assess continued intercoder reliability, which remained high.

Data Analysis

Data included the video-recorded clinical interactions, patient and oncologist self-reported sociodemographics, and patient-reported amount of social support and social support satisfaction. Bivariate associations between the outcome variables and patient age, education, income, perceived amount of social support and satisfaction with social support, and interaction length were examined to identify possible predictors and covariates to be included in the regression analyses.

The primary analyses of the predictors for the outcome variables used generalized estimating equation (GEE)55,56 multiple regressions with robust standard error estimates to account for patients being clustered within oncologist. Patient attributes and other variables that correlated with the outcome variables were included in the GEEs.

The first GEE used absence or presence of a cost discussion as the outcome variable. For the clinical interactions that included cost discussions, two more GEEs were conducted, with frequency of cost discussions and total time spent in discussion about cost as the outcome variables. Study arm to which patients were assigned in the parent study was included as a covariate in all regression analyses. For all analyses, α was set at P < .05 (two-tailed).

RESULTS

Of the 273 patients invited to participate in the parent study, 137 (50%) accepted. Patients who declined to participate did so because of limited time or feeling burdened by their cancer. An analysis of zip codes of participants and nonparticipants suggested that they came from areas with similar sociodemographic characteristics.50 Twenty-three patients were excluded from this analysis because they were not video recorded as a result of issues with equipment availability. Eleven patients were excluded from this analysis because their diagnosis did not warrant a discussion of medical treatment (eg, ductal carcinoma in situ). Thus, the final sample was composed of 103 patients.

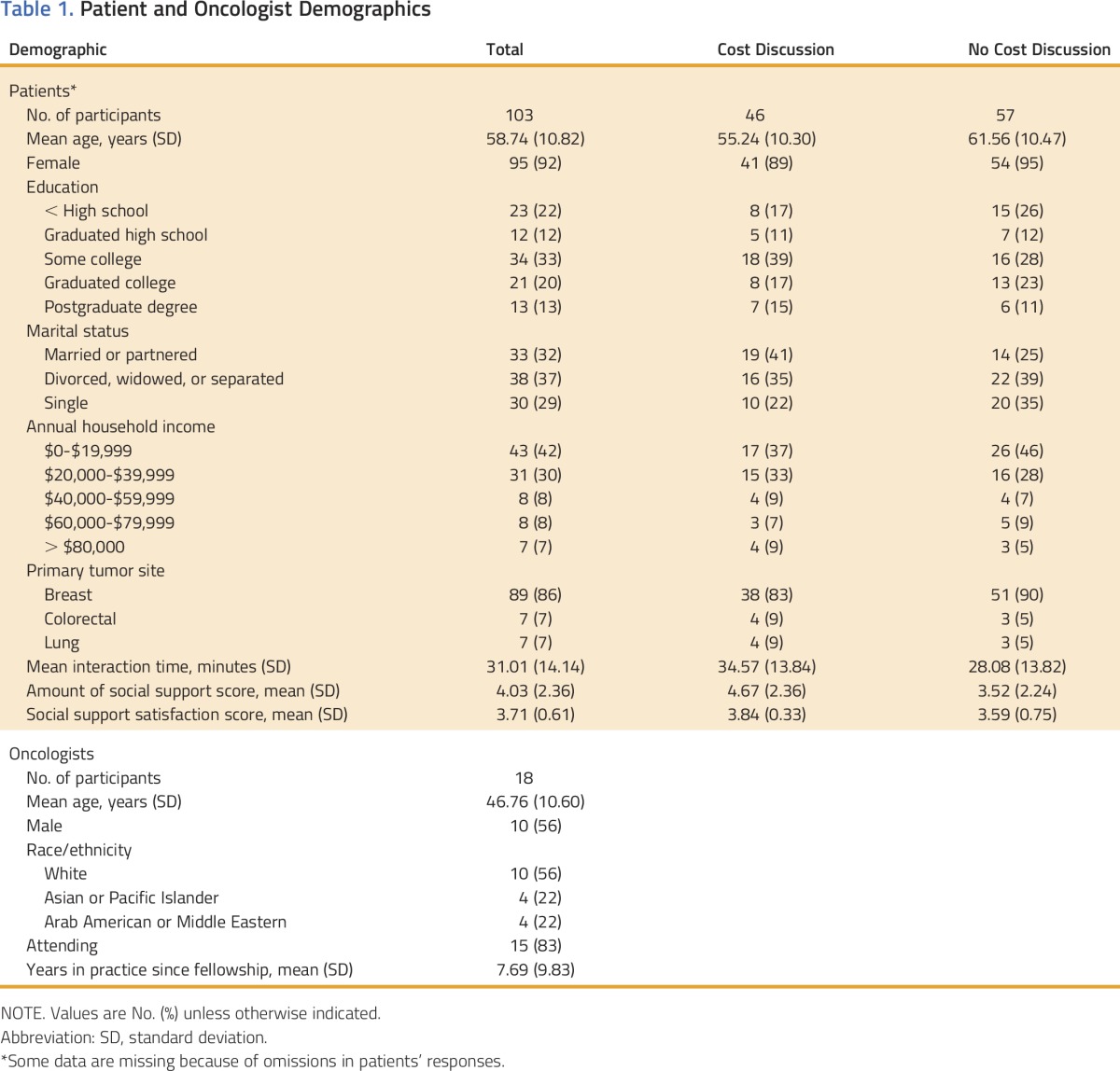

The sociodemographic characteristics of the 103 African American patients and their non–African American medical oncologists (n = 18) are listed in Table 1. All patients self-identified as African American, and most had breast cancer (87%). Most patients (73%) reported annual household incomes of < $40,000. Ten of the 18 oncologists were male, 56% reported their race as white, 22% reported being Asian or Pacific Islander, and 22% reported being Arab American or Middle Eastern. On average, each oncologist saw six patients (range, 1 to 25 patients).

Table 1.

Patient and Oncologist Demographics

Occurrence and Nature of Cost Discussions

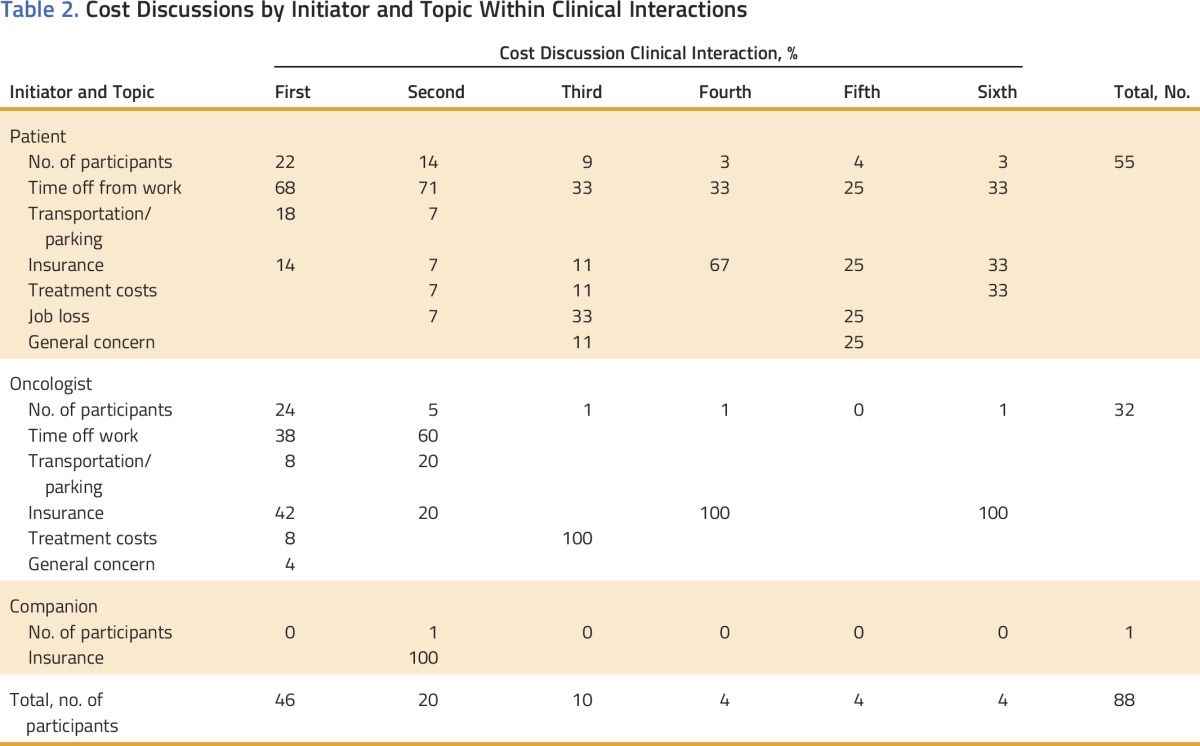

Cost discussions occurred in 46 (45%) of 103 patient-oncologist clinical interactions. One to six cost discussions occurred per interaction for a total of 88 (mean, 1.91; standard deviation [SD], 1.46). Individual cost discussions lasted an average of 35.72 seconds (SD, 34.85 seconds). Total average time spent in discussion about cost within the entire clinical interaction was 1.14 minutes (SD, 1.18 minutes), which comprised an average of 3.28% (SD, 0.03%) of the interaction length. Twenty-nine patients initiated 55 (63%) of the 88 cost discussions; 11 oncologists initiated 32 (36%) discussions. Companions were present in 59% of interactions, and one companion (1%) initiated one cost discussion (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cost Discussions by Initiator and Topic Within Clinical Interactions

Patient-initiated discussions

In the 55 patient-initiated cost discussions, concern about having to take time off from work for treatment or recovery was the most frequent topic (56%) followed by insurance questions or concerns (16%); transportation and parking costs (11%); concerns about loss of employment as a result of extended time off from work for treatment and recovery (7%); out-of-pocket costs for treatment, such as copayments (6%); and general financial concerns (4%). Oncologists’ responses to patient-initiated discussions were to address the issue directly (69%); to refer the patient to another health care provider, such as a social worker (20%); or to not address the issue (11%).

Most patients (78%) were observed to agree or be satisfied with the oncologist’s response to patient-initiated discussions (most frequently with a head nod or by saying okay or yes). Patients demonstrated disagreement or dissatisfaction in 6% of discussions (usually observed as a head shake or similar nonverbal behavior). The patient changed the topic in 7% of the discussions, and the oncologist changed topic in 9%. The switch to a cost topic occurred twice.

Oncologist-initiated discussions

In the 32 oncologist-initiated cost discussions, insurance was the most frequent topic (41%) followed by time off from work (38%), transportation and parking costs (9%), out-of-pocket costs for treatment (9%), and general financial concerns (3%). If an oncologist initiated a discussion, he or she always addressed the topic.

Coders judged the majority of patients (66%) to be either in agreement or satisfied with the oncologist’s response to oncologist-initiated discussions. Patients always provided answers to oncologist-posed questions in the remaining 34% of oncologist-initiated discussions.

Correlates of Cost Discussions

Bivariate associations between the outcome variables (ie, presence of a cost discussion, frequency of a cost discussion within a single clinical interaction, time spent in discussion about cost) and patient age, income, education, and interaction length identified patient demographic characteristics (ie, age, income, education) to be included in the GEE analyses of the cost discussions. The only characteristic associated with the outcome variables was patient age, which was significantly (P ≤ .05) and negatively correlated with presence of a cost discussion (r = −0.29), frequency of cost discussions (r = −0.26), and time spent in discussion about cost (r = −0.22).

Perceived amount of social support was significantly and positively correlated with the presence of a cost discussion (r = 0.24), frequency of cost discussions (r = 0.29), and time spent in discussion about cost (r = 0.26). Perceived satisfaction with social support was significantly and positively associated with presence of a cost discussion (r = 0.21) and time spent in discussion about cost (r = 0.26).

As would be expected, interaction length was significantly and positively correlated with the presence of a cost discussion (r = 0.23), frequency of cost discussions (r = 0.33), and time spent in discussion about cost (r = 0.35).

Thus, the following were included as predictors in the GEE analyses: patient age, amount of social support, and satisfaction with social support. Interaction length was included as a covariate. Although the outcome variables did not significantly differ by study arm, study arm was also included in the models as a covariate because other research50 has found that the parent study intervention affected the level of patient participation.

The GEE analysis of the predictors of the presence of a cost discussion revealed that patient age was negatively associated with the probability that cost was discussed (B = −0.15; standard error [SE], 0.07; P = .05; odds ratio [OR], 4.0; 95% CI, −0.3 to −0.003), and perceived satisfaction with social support was positively associated with the probability that cost was discussed (B = 0.08; SE, 0.03; P = .009; OR, 6.9; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.15). The perceived amount of social support was not associated with the probability that cost was discussed. There were no significant interactions.

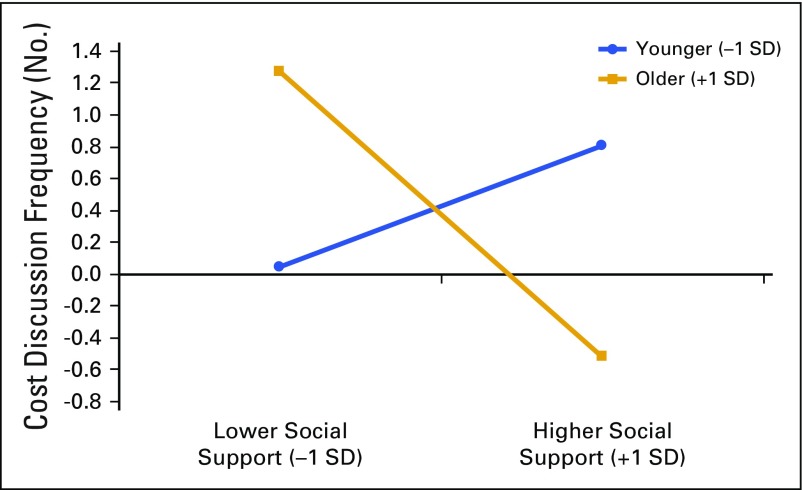

For clinical interactions that included a cost discussion, the GEE analysis with frequency of cost discussions as the outcome variable found no significant bivariate associations with age or the two aspects of social support. However, a significant interaction was found between patient age and perceived amount of social support that affected the frequency of cost discussions (B = −0.55; SE, 0.11; P < .001; OR, 26.8; 95% CI, −0.76 to −0.34; Fig 1). Among younger patients (−1 SD), a significant positive association was found between perceived amount of social support and frequency of cost discussions (ie, more perceived support, higher frequency of discussions). However, among older patients (+1 SD), a significant negative association was found between perceived amount of social support and frequency of cost discussions (ie, more perceived support, lower frequency of discussions).

FIG 1.

Simple slopes of amount of social support that predicted cost discussion frequency for 1 standard deviation (SD) below the mean age and 1 SD above the mean age.

The GEE analysis of the predictors of time spent in discussion about cost revealed neither age nor either aspect of social support to be significantly associated.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to use video-recorded patient-oncologist clinical interactions to identify and code treatment cost discussions. The discussion of cancer treatment costs with patients is purported to be a key component of high-quality care18 and may alleviate financial toxicity.5,15-20 Most physicians report that they discuss cost with patients,23 but a cost discussion occurred in fewer than one half of the clinical interactions observed in this study. Most cost discussions were patient initiated and focused on indirect or opportunity costs of cancer care rather than on the direct costs of treatment. Thus, the treatment-related cost topics that patients discussed were not those considered in the common definition of treatment costs used by the academic and medical communities.1,5,17,21

The Influence of Age and Social Support on Cost Discussions

The reason for the negative association between age and cost discussions is not immediately clear but may involve employment and insurance. The most frequent patient-initiated cost topic was time off from work. Older patients were more likely to be retired and less likely to raise the issue of work in treatment discussions. Furthermore, in the United States, a person is eligible for Medicare at the age of 65 years. Perhaps cost was discussed less in clinical interactions with older patients because of an assumption by the patient or the oncologist that Medicare would cover treatment costs.

Patient-perceived social environment also influenced cost discussions with oncologists. Supportive relationships appear to matter to patients who have limited financial resources and influence their mind-sets when they face the realities of cancer treatment. The majority of patients (73%) reported an annual household income of less than $40,000; hence, social environment may have created a basis for the salience of treatment-related costs. Perhaps patients were more likely to discuss costs because their family and friends urged them to do so. More research would help to clarify this situation.

For older patients, less perceived amount of social support was associated with more cost discussions, whereas more perceived amount of social support was associated with fewer cost discussions. Perhaps for older patients, a lack of satisfaction with social support prompted them to look to their physician for support with cost issues. Further research will help to elucidate this finding.

Implications for ASCO’s Value of Cancer Treatment Options Framework

The topics of discussions observed in this study should be considered in the context of the ASCO Value of Cancer Treatment Options Framework.17,18,21 ASCO’s Value Framework weighs clinical benefit and toxicity against cost of treatment and prompts oncologist-patient discussions of treatment value. However, the definition of cost in the framework is limited to a patient’s direct expenses (eg, copayments).57 Thus many of the cost issues observed in this study would not be taken into account within the framework. This is a particular concern for minority patients who are especially vulnerable to financial toxicity caused by direct11,31,33 and indirect financial demands of a cancer diagnosis.32

Limitations and Future Research

These data and conclusions must be considered within the limitations of the study, which was a secondary analysis of larger study of patient-oncologist communication that was not specifically focused on cost discussions. All the patients were African American and more than 90% were female, which limits the generalizability of the findings. However, we believe that information about cost discussions among this understudied population, which is especially vulnerable to financial toxicity, is important. Future research should assess what patients want to know about treatment cost before the interaction, determine which questions were answered, and assess the patient’s level of understanding of cost discussions after the interaction. In addition, cost discussion outcomes were solely based on the coders’ observations because corroborative patient self-report data were unavailable. Finally, patient insurance status may play a role in cost discussions, but because of national-level insurance changes during data collection (ie, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act), insurance data that could be meaningfully mapped onto the cost outcomes could not be collected.

In conclusion, cost discussions occurred in fewer than one half of cancer treatment clinical interactions with African American patients; they often were patient initiated and focused mainly on taking time off from work. The discussions were not focused on cost per ASCO’s Value Framework definition. The findings highlight that African American patients are not a homogenous group58,59 because patient age and perceived amount of and satisfaction with social support played a role in the presence and frequency of cost discussions. Interventions to educate patients to ask questions about cost and train providers to sensitively and appropriately initiate cost discussions with all patients are critical steps toward more-informed patients, more-informed treatment decisions, and the potential for less financial toxicity.2,17,18,60

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation Investigator Initiated Award 2063.ii (L.H., principal investigator); National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant U54CA153606 (T.A., principal investigator; R.C., co-principal investigator); and National Cancer Institute Center grant P30CA22453 (G.B., principal investigator). Presented at the ASCO Quality Care Symposium, Phoenix, AZ, February 26-27, 2016.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Lauren M. Hamel, Susan Eggly, Robert Chapman, Terrance L. Albrecht

Financial support: Lauren M. Hamel, Terrance L. Albrecht

Collection and assembly of data: Lauren M. Hamel, Susan Eggly, Terrance L. Albrecht

Data analysis and interpretation: Lauren M. Hamel, Louis A. Penner, Susan Eggly, Justin F. Klamerus, Michael S. Simon, Sarah C.E. Stanton, Terrance L. Albrecht

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Do Patients and Oncologists Discuss the Cost of Cancer Treatment? An Observational Study of Clinical Interactions Between African American Patients and Their Oncologists

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jop/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Lauren M. Hamel

No relationship to disclose

Louis A. Penner

No relationship to disclose

Susan Eggly

No relationship to disclose

Robert Chapman

No relationship to disclose

Justin F. Klamerus

No relationship to disclose

Michael S. Simon

No relationship to disclose

Sarah C.E. Stanton

No relationship to disclose

Terrance L. Albrecht

Consulting or Advisory Role: Eli Lilly

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Eli Lilly

REFERENCES

- 1.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, et al. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: A prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:145–150. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:332–338. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner L, Lacey MD. The hidden costs of cancer care: An overview with implications and referral resources for oncology nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2004;8:279–287. doi: 10.1188/04.CJON.279-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure—out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1484–1486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1306826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins SR, Rasmussen PW, Doty MM, et al: Americans’ experiences with marketplace and Medicaid coverage. Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey, March-May 2015. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 16:1-17, 2015 [PubMed]

- 8.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation 2015 Employer health benefits survey. http://kff.org/health-costs/report/2015-employer-health-benefits-survey/2015

- 9.PwC Health Research Institute: Medical cost trend: Behind the numbers 2016. https://www.pwc.com/us/en/health-industries/behind-the-numbers/assets/pwc-hri-medical-cost-trend-chart-pack-2016.pdf

- 10.American Society of Clinical Oncology The state of cancer care in America, 2016: A report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:339–383. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.010462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jagsi R, Pottow JA, Griffith KA, et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: Experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1269–1276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1143–1152. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markman M, Luce R. Impact of the cost of cancer treatment: An Internet-based survey. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:69–73. doi: 10.1200/JOP.091074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:980–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, et al. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:162–167. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ubel PA: Doctor, first tell me what it costs. The New York Times, November 3, 2013:A25

- 17.Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement: A conceptual framework to assess the value of cancer treatment options. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2563–2577. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: The cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3868–3874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blum D: How physicians can explain value to patients. ASCO Daily News, May 29, 2015. https://am.asco.org/how-physicians-can-explain-value-patients

- 20.Bath C. Disclosing medical costs can help avoid ‘financial toxicity.’ The ASCO Post, December 15, 2013. http://www.ascopost.com/issues/december-15-2013/disclosing-medical-costs-can-help-avoid-financial-toxicity

- 21.Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. Updating the American Society of Clinical Oncology Value Framework: Revisions and reflections in response to comments received. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2925–2934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bullock AJ, Hofstatter EW, Yushak ML, et al. Understanding patients’ attitudes toward communication about the cost of cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:e50–e58. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altomare I, Irwin B, Zafar SY, et al. ReCAP: Physician experience and attitudes toward addressing the cost of cancer care J Oncol Pract 12:247-2482016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim P. Cost of cancer care: The patient perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:228–232. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schrag D, Hanger M. Medical oncologists’ views on communicating with patients about chemotherapy costs: A pilot survey. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:233–237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly RJ, Forde PM, Elnahal SM, et al. Patients and physicians can discuss costs of cancer treatment in the clinic. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:308–312. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.003780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ubel PA, Zhang CJ, Hesson A, et al. Study of physician and patient communication identifies missed opportunities to help reduce patients’ out-of-pocket spending. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:654–661. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Meltzer DO. Patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. JAMA. 2003;290:953–958. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helwick C. Discussions about the cost of cancer care are still uncommon. The ASCO Post, May 15, 2014. http://www.ascopost.com/Meetings/?m=19th+Annual+NCCN+Conference

- 30.DeNavas-Walt D, Proctor B. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pisu M, Kenzik KM, Oster RA, et al. Economic hardship of minority and non-minority cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: Another long-term effect of cancer? Cancer. 2015;121:1257–1264. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradley CJ, Wilk A. Racial differences in quality of life and employment outcomes in insured women with breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:49–59. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0316-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pisu M, Azuero A, Meneses K, et al. Out of pocket cost comparison between Caucasian and minority breast cancer survivors in the Breast Cancer Education Intervention (BCEI) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:521–529. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1225-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mosavel M, Sanders K. Needs of low-income African American cancer survivors: Multifaceted and practical. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:717–723. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darby K, Davis C, Likes W, et al. Exploring the financial impact of breast cancer for African American medically underserved women: A qualitative study. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20:721–728. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamel LM, Chapman R, Malloy M, et al. Critical shortage of African American medical oncologists in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3697–3700. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, et al. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907–915. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:979–987. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, et al. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2084–2090. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Penner LA, Eggly S, Griggs JJ, et al: Life-threatening disparities: The treatment of black and white cancer patients. J Soc Issues 68:328-357, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eggly S, Harper FW, Penner LA, et al. Variation in question asking during cancer clinical interactions: A potential source of disparities in access to information. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eggly S, Barton E, Winckles A, et al. A disparity of words: Racial differences in oncologist-patient communication about clinical trials. Health Expect. 2015;18:1316–1326. doi: 10.1111/hex.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siminoff LA, Graham GC, Gordon NH. Cancer communication patterns and the influence of patient characteristics: Disparities in information-giving and affective behaviors. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Psychological distress among black and white Americans: Differential effects of social support, negative interaction and personal control. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:390–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krause N. Exploring the stress-buffering effects of church-based and secular social support on self-rated health in late life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61:S35–S43. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, et al. A brief measure of social support - practical and theoretical implications. J Soc Pers Relat. 1987;4:497–510. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harper FW, Peterson AM, Albrecht TL, et al. Satisfaction with support versus size of network: Differential effects of social support on psychological distress in parents of pediatric cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2016;25:551–558. doi: 10.1002/pon.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eggly S, Tkatch R, Penner LA, et al. Development of a question prompt list as a communication intervention to reduce racial disparities in cancer treatment. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28:282–289. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0456-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Gonzalez R, et al. The effects of oncologist implicit racial bias in racially discordant oncology interactions. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2874–2880. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eggly S, Hamel LM, Albrecht TL, et al: Randomized trial of a question prompt list to increase patient active participation during racially discordant oncology interactions. Presented at Ninth AACR Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved, Fort Lauderdale, FL, September 25-28, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Albrecht TL, Eggly SS, Gleason ME, et al. Influence of clinical communication on patients’ decision making on participation in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2666–2673. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Albrecht TL, Ruckdeschel JC, Ray FL, III, et al. A portable, unobtrusive device for videorecording clinical interactions. Behav Res Methods. 2005;37:165–169. doi: 10.3758/bf03206411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Penner LA, Orom H, Albrecht TL, et al. Camera-related behaviors during video recorded medical interactions. J Nonverbal Behav. 2007;31:99–117. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Riddle DL, Albrecht TL, Coovert MD, et al. Differences in audiotaped versus videotaped physician-patient interactions. J Nonverbal Behav. 2002;26:219–239. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ziegler A, Blettner M, Kastner C, et al. Identifying influential families using regression diagnostics for generalized estimating equations. Genet Epidemiol. 1998;15:341–353. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1998)15:4<341::AID-GEPI2>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data-analysis using generalized linear-models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Young RC. Value-based cancer care. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2593–2595. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1508387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hagiwara N, Penner LA, Gonzalez R, et al. Racial attitudes, physician-patient talk time ratio, and adherence in racially discordant medical interactions. Soc Sci Med. 2013;87:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Hagiwara N, et al. An analysis of race-related attitudes and beliefs in black cancer patients: Implications for health care disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27:1503–1520. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sulmasy D, Moy B. Debating the oncologist’s role in defining the value of cancer care: Our duty is to our patients. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:4039–4041. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.8716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]