Abstract

Purpose:

Genomic testing improves outcomes for many at-risk individuals and patients with cancer; however, little is known about how genomic testing for non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) is used in clinical practice.

Patients and Methods:

In 2012 to 2013, we surveyed medical oncologists who care for patients in diverse practice and health care settings across the United States about their use of guideline- and non–guideline-endorsed genetic tests. Multivariable regression models identified factors that are associated with greater test use.

Results:

Of oncologists, 337 completed the survey (participation rate, 53%). Oncologists reported higher use of guideline-endorsed tests (eg, KRAS for CRC; EGFR for NSCLC) than non–guideline-endorsed tests (eg, OncotypeDX Colon; ERCC1 for NSCLC). Many oncologists reported having no patients with CRC who had mismatch repair and/or microsatellite instability (24%) or germline Lynch syndrome (32%) testing, and no patients with NSCLC who had ALK testing (11%). Of oncologists, 32% reported that five or fewer patients had KRAS and EGFR testing for CRC and NSCLC, respectively. Oncologists, rather than pathologists or surgeons, ordered the vast majority of tests. In multivariable analyses, fewer patients in nonprofit integrated health care delivery systems underwent testing than did patients in hospital or office-based single-specialty group settings (all P < .05). High patient volume and patient requests (CRC only) were also associated with higher test use (all P < .05).

Conclusion:

Genomic test use for CRC and NSCLC varies by test and practice characteristics. Research in specific clinical contexts is needed to determine whether the observed variation reflects appropriate or inappropriate care. One potential way to reduce unwanted variation would be to offer widespread reflexive testing by pathology for guideline-endorsed predictive somatic tests.

INTRODUCTION

Advances in cancer genetics, targeted therapies, and risk reduction strategies have transformed the landscape of care for individuals who are at risk of developing cancer and for patients with cancer. This transformation has been particularly striking in non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and colorectal cancer (CRC). For example, genomic testing for Lynch syndrome (LS) is guideline endorsed for individuals with CRC or a family history of CRC.1 In addition, predictive somatic genomic testing (eg, EGFR or KRAS) is the standard of care for many patients with advanced NSCLC or CRC.2,3 Despite the fact that genomic testing can improve outcomes for specific patient subpopulations, relatively little is known about how genomic testing for NSCLC and CRC is used in practice.

Prior work has demonstrated that test use varies by test type and clinical context. Data suggest that only 30% to 60% of patients who meet testing criteria actually receive cancer susceptibility testing,4 and LS testing is underused compared with testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer.4 Multiple factors have been associated with germline test adoption, including patient requests, access to testing, providers’ specialty, and providers’ genomic confidence.5 Our work on CRC testing has shown that some oncologists fail to recommend LS testing when indicated, and others recommend inappropriate KRAS testing for early-stage disease.6 Studies of somatic test adoption have shown relatively low use of KRAS testing for patients with metastatic CRC (36% to 53% of patients), although use has increased over time.7,8 Prior work has also shown low use of EGFR testing in NSCLC and potential disparities in test ordering.9 Potential barriers to somatic testing include lack of guidelines, lack of insurance reimbursement, and providers’ low confidence in assessing whether testing is indicated.10,11

Given the potential benefit of widespread adoption of guideline-endorsed genomic testing and the relative paucity of data about test use in diverse patient populations, we investigated how medical oncologists use genomic testing for CRC and NSCLC in practice. Because we were interested in adoption of recommended and nonrecommended genomic technologies,12 we studied oncologists’ use of a range of somatic and germline tests—some of which, at the time of survey administration, were guideline endorsed, whereas others were not (Table 1). We hypothesized that oncologists would report higher use of tests with known clinical utility than tests supported by low levels of evidence; more frequent ordering of screening for LS by pathologists than medical oncologists; and propensity to refer patients to other providers for germline LS testing rather than ordering testing themselves.

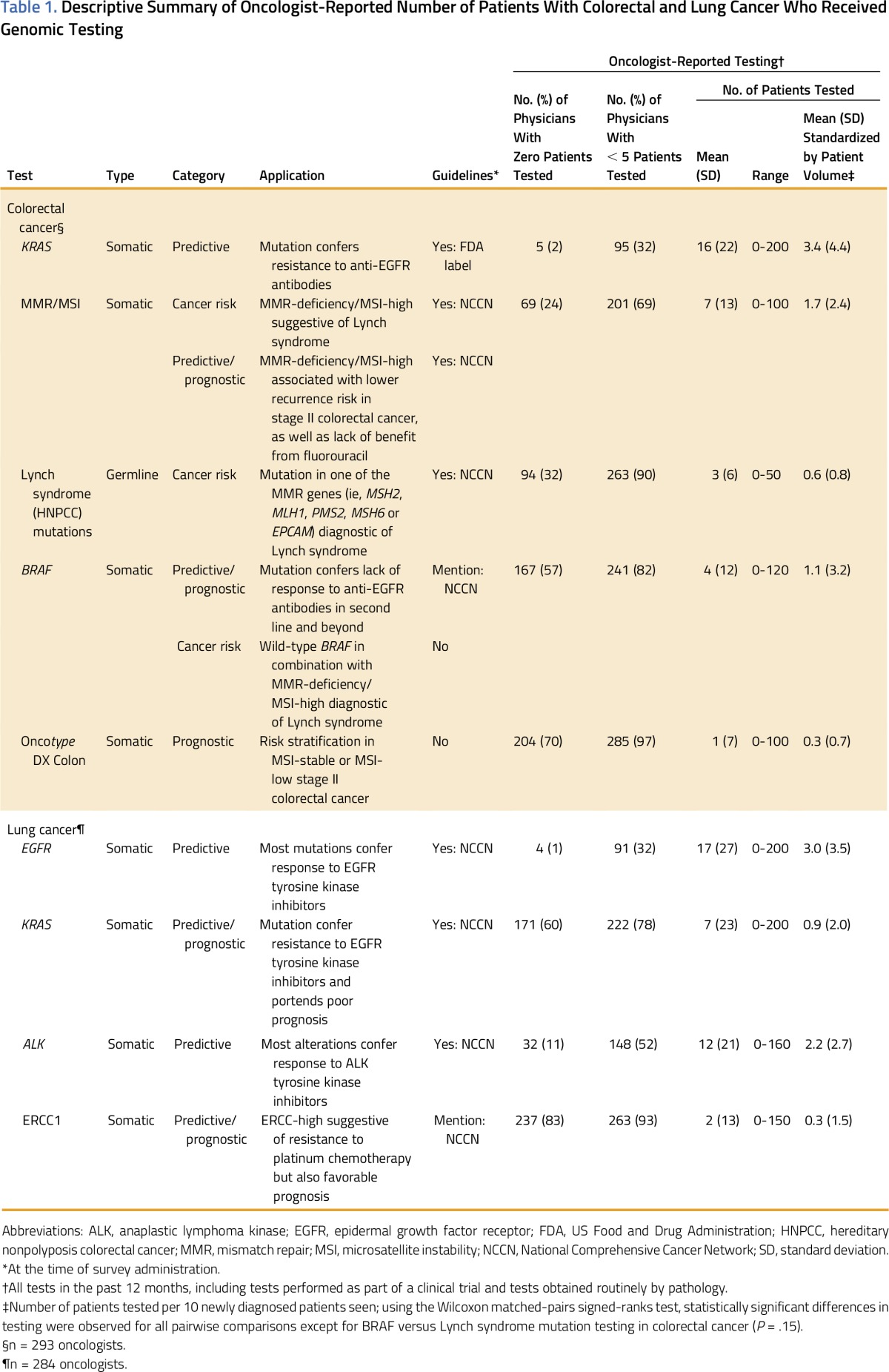

Table 1.

Descriptive Summary of Oncologist-Reported Number of Patients With Colorectal and Lung Cancer Who Received Genomic Testing

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Population

The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study enrolled a population- and health system–based cohort of individuals who were newly diagnosed with lung cancer or CRC in 2003 to 2005 (Appendix, online only).13 CanCORS participants are similar to patients with cancer in the United States as a whole.14 In 2006 to 2008, the study surveyed physicians who care for CanCORS patients who were identified through CanCORS patient surveys or medical record review. Medical oncologists who care for CanCORS patients at baseline as well as medical oncologists identified during a follow-up patient survey in 2011 were surveyed for this study.6,15 Physicians were ineligible if they were deceased or no longer in practice.

Survey Instrument

A primary objective of the survey was to understand oncologists’ use of genetic tests. Genetic testing was defined broadly as the analysis of DNA, RNA, genes, chromosomes, or proteins [that] may help to predict cancer risk, establish a cancer diagnosis or prognosis, and/or guide clinical management (survey Instrument is available at www.cancors.org/public). The primary outcome variables, adapted from our prior work,11 were defined on the basis of physicians’ responses to the question: “In the past 12 months, approximately how many of your colorectal [or lung] cancer patients have had the following tests? Please include tests performed as part of a clinical trial and tests done routinely by pathology.” The question was followed by a list of tests that were specific for each tumor type (eg, KRAS, BRAF for CRC or EGFR, ALK for lung). Other survey domains included the oncologist’s beliefs about the provider who usually requests/orders genetic testing in the practice (tumor specific and for each test); the factors that impact decisions to request somatic testing; whether costs are discussed with patients before ordering somatic testing; and the information sources about somatic testing.11 The survey also asked about provider and practice characteristics, number of newly diagnosed patients with CRC and NSCLC seen per month (new patient volume), and financial arrangements. Physicians were only queried about lung and/or CRC testing if they reported caring for patients with lung cancer or CRC.

Study Procedures

In June to August 2012, we mailed a self-administered questionnaire and a $50 incentive check to 679 medical oncologists.6,15 Physicians could respond by paper or via a secure Web site. Physicians who did not respond were sent up to three additional mailings and another $50 incentive check, and called by telephone, for a total of 10 contact attempts.

Statistical Analyses

Physician responses about test utilization were summarized as the absolute number of lung (CRC) cancer patients tested (1) in the last 12 months, and (2) in the last 12 months standardized by new lung (CRC) patient volume.

We used multivariable negative binomial regression models to evaluate the relationships between covariates and the number of patients with CRC or NSCLC tested in the last 12 months.16 Negative binomial regression models the count of an event and is appropriate when the variance of the count variable is greater than its mean. The effect estimate from negative binomial regression is the incidence rate ratio, which, for categorical predictor variables, represents the rate of testing over the past 12 months for a group of interest versus the reference group. Data were structured with repeated measures because physicians contributed multiple outcome measures for each of the five test responses for CRC testing and/or multiple outcome measures for each of the test responses for NSCLC (eg, number of patients with NSCLC tested for EGFR, number of patients with CRC tested for ALK; Table 1 lists the tests used). Separate models were fit for CRC and NSCLC testing; robust estimates of variance were used to correct for within-physician correlations within disease-specific models.

All explanatory variables of interest were included in the multivariable models regardless of statistical significance. All explanatory variables of interest were included in the multivariable models, regardless of statistical significance. Models included provider characteristics (ie, age, sex, involvement in teaching) and practice type (ie, nonprofit integrated health care delivery systems such as Kaiser Permanente and institutions participating in the National Cancer Institute [NCI] Cancer Research Network; Veterans Affairs or government-based; office-based solo, single-specialty, or multispecialty group practice; or hospital-based) as independent variables as well as patient requests/inquiries about testing, whether oncologists obtained information about tests from the manufacturer/pharmaceutical company representative or Web site.5 We also included financial incentives for testing, that is, whether physician income was likely to increase by ordering more genetic testing, as an independent variable because we hypothesized that incentives might influence test adoption. To account for variation in the outcome variable as a result of practice volume, we adjusted for new patient volume. We included genomic test type as an independent variable to assess the relative use of each test compared with a guideline-endorsed somatic predictive test (ie, KRAS for CRC and EGFR for NSCLC). To evaluate guideline-endorsed versus non–guideline-endorsed tests, we replaced the test type variable with a dichotomous variable in which all tests were guideline endorsed except BRAF and OncotypeDX Colon (Genomic Health, Redwood City, CA) for CRC and ERCC1 for NSCLC.

Multiply imputed data were used for independent variables in the multivariable models, but not for the outcome variables. Item nonresponse was < 3% for all covariates. To examine the influence of independent variables on specific genomic test use, we also developed a model for each genomic test. To confirm that differences in oncologists’ patient volumes did not account for the observed variation, we also conducted sensitivity analyses in which we modeled the relationships between our independent variables and outcomes standardized by new patient volume. Statistical analyses were conducted by using STATA 13.1 (STATA, College Station, TX; Computing Resource Center, Santa Monica, CA).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

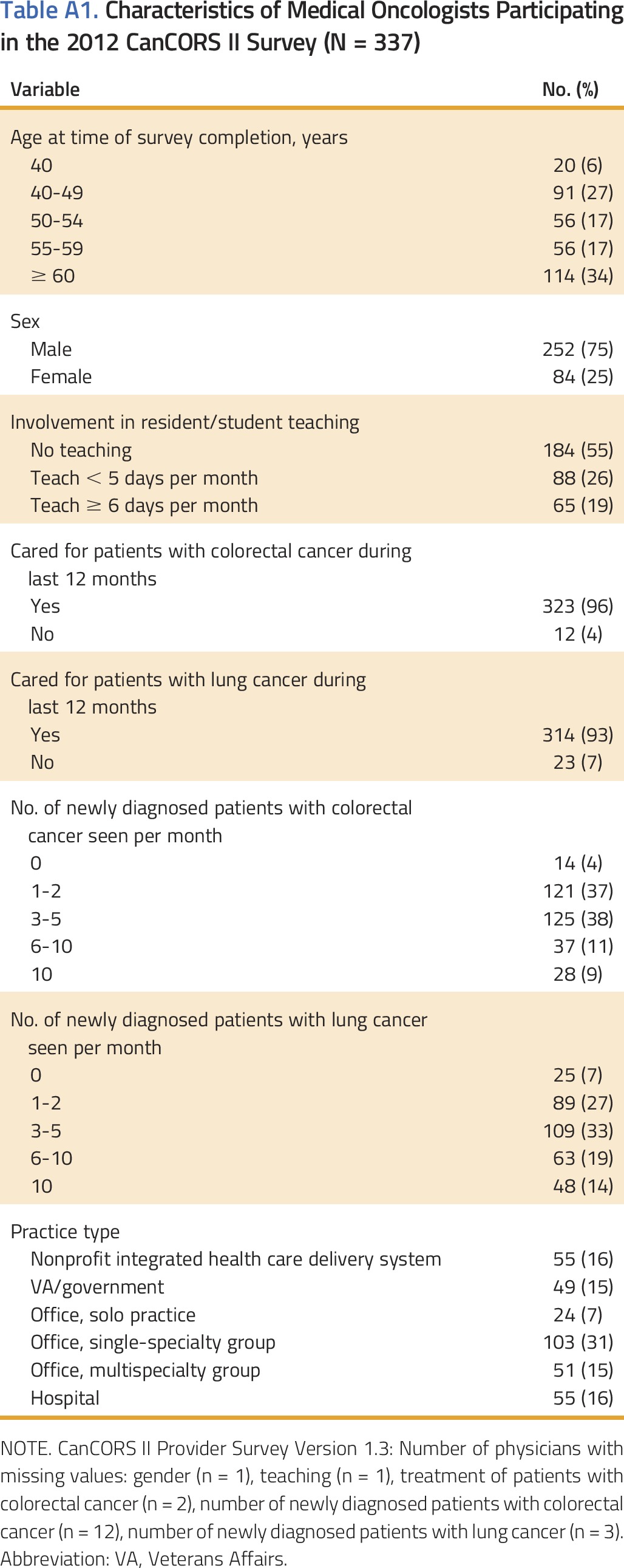

Of 679 physicians contacted, 337 completed the survey (absolute response rate,17 46%; participation rate, 53%).15 There were no significant differences between those who responded and those who did not (Appendix).15 Oncologists’ characteristics are reported in Appendix Table A1 (online only). A minority of oncologists specialized in the treatment of patients with NSCLC or CRC.

Number of Patients Who Received Genomic Testing

Two hundred ninety-three (86%) and 284 (84%) oncologists reported that they cared for patients with CRC or NSCLC, respectively, in the last 12 months and responded to the test use items. Oncologist-reported rates of testing for CRC patients were higher for KRAS than screening for LS (i.e., mismatch repair [MMR] proteins by immunohistochemistry/microsatellite instability [MSI] testing), somatic BRAF testing, germline LS testing, and OncotypeDX Colon (Table 1). Oncologists reported that more patients with NSCLC were tested for EGFR than ALK, KRAS, and ERCC1. We found similar test use patterns when we standardized by new patient volume. Many oncologists reported having no patients with CRC who had MMR/MSI (24%) or germline Lynch syndrome (32%) testing, and no patients with NSCLC who had ALK testing (11%). Of oncologists, 32% reported that five or fewer patients had KRAS and EGFR testing for CRC and NSCLC, respectively.

Genetic Testing Patterns and Influences

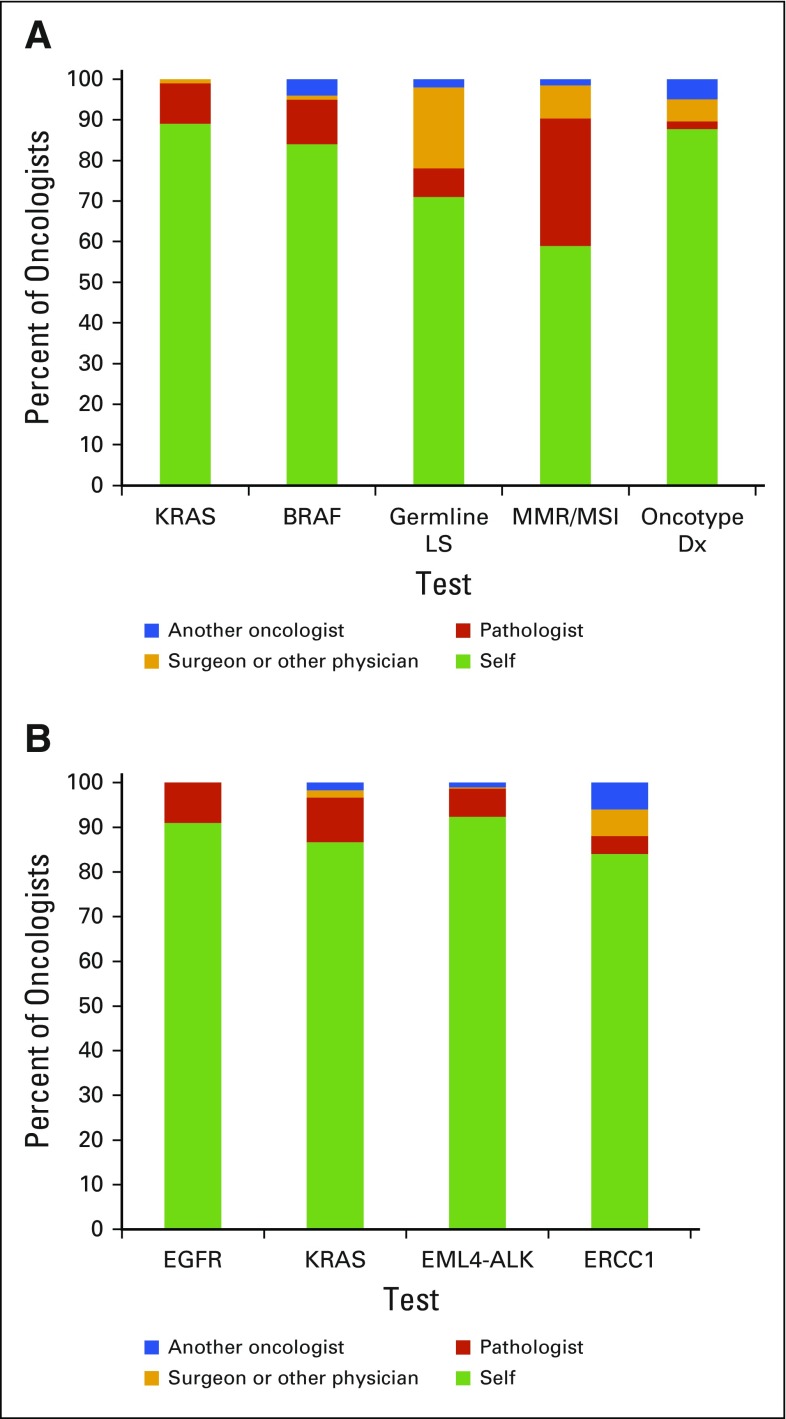

Oncologists reported ordering or requesting the vast majority of tests themselves (Fig 1). Sixteen percent of oncologists reported that patients’ requests had a high impact on their decisions to request somatic testing. Although 45% reported that they or their office staff often discuss the cost of testing with patients when requesting somatic testing, 31% rarely or never discuss cost.

FIG 1.

(A and B) Oncologists' reports of provider usually requesting or ordering genomic testing for (A) colorectal cancer and (B) lung cancer. Mismatch repair (MMR)/microsatellite instability (MSI) refers to MMR protein/MSI somatic testing. Germline Lynch syndrome (LS) testing refers to testing for mutations in LS genes.

Factors Associated With Test Use: Results From Unadjusted and Multivariable Analyses

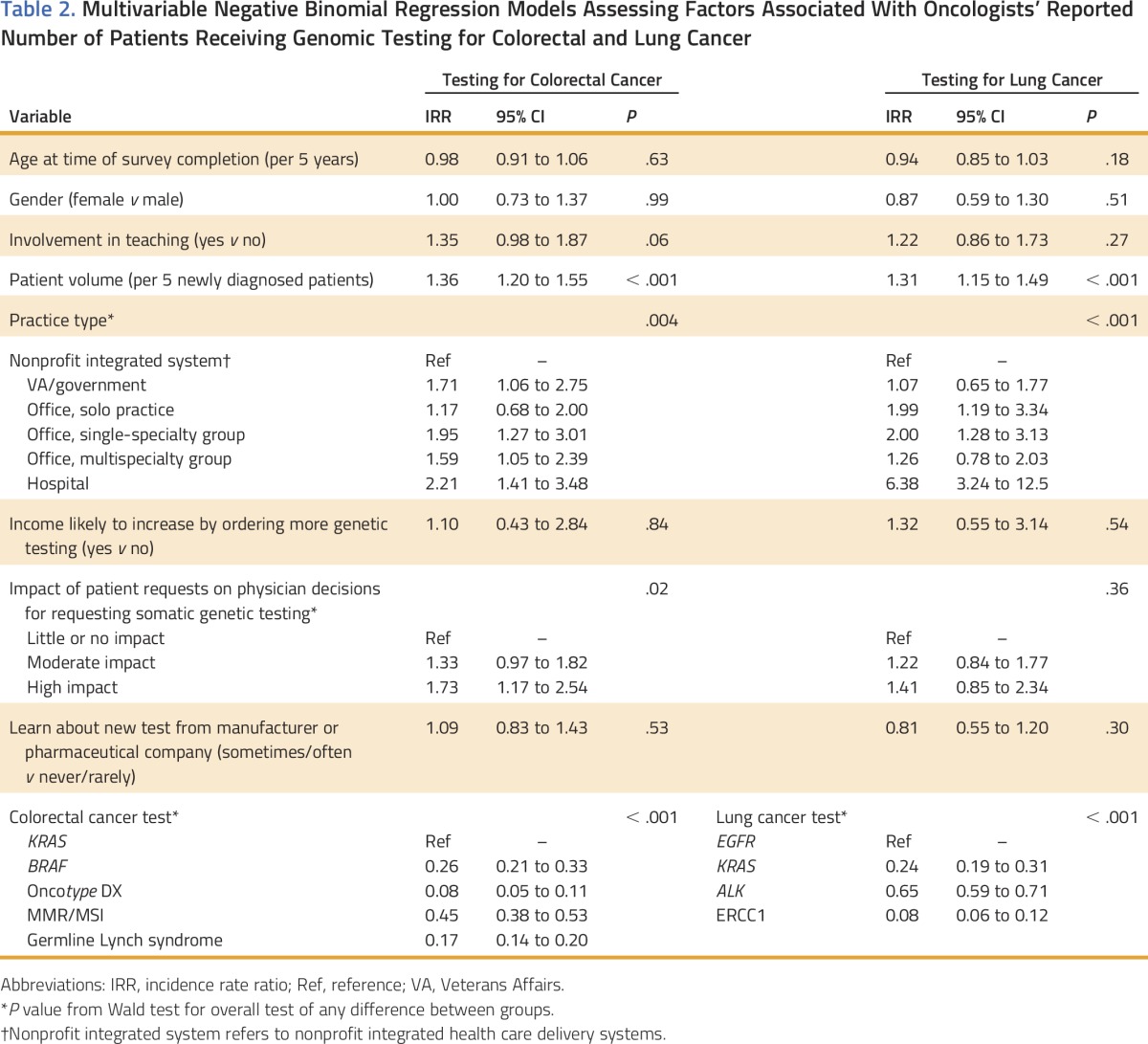

For both cancer types, in adjusted analyses, oncologists who practiced in nonprofit integrated systems reported having fewer patients who underwent genomic testing compared with hospital-based oncologists, those in single-specialty groups, as well as oncologists in multispecialty groups (CRC) or solo practice (NSCLC; Table 2). We observed additional variation in test use by practice type without clear patterns across the two cancers. Oncologists who reported that patient requests had a moderate or high impact on their decisions to order somatic testing also indicated that more of their patients received genomic tests for CRC compared with oncologists who reported that patient requests had little or no impact on their decisions. In addition, more patients of higher-volume oncologists were tested than of lower-volume oncologists. The most frequently ordered tests were KRAS for CRC and EGFR for NSCLC; rates were lower for other tests. Oncologists reported use of fewer non–guideline-endorsed tests than guideline-endorsed tests (AOR, 0.26 to 0.38 for CRC; AOR, 0.10 to 0.20 for NSCLC; P < .001).

Table 2.

Multivariable Negative Binomial Regression Models Assessing Factors Associated With Oncologists’ Reported Number of Patients Receiving Genomic Testing for Colorectal and Lung Cancer

In models that assessed each test separately, oncologists’ reports of learning about new tests from manufacturers’ and/or pharmaceutical companies’ Web sites or representatives were associated with more OncotypeDx Colon testing for CRC (not shown). Our sensitivity analyses, which modeled outcomes standardized by new patient volume, yielded similar results (not shown).

DISCUSSION

We conducted a survey of medical oncologists in diverse practice and geographic settings in the United States and found substantial variation in the use of genomic testing for NSCLC and CRC. Consistent with our hypothesis, oncologists reported higher use of evidence-based genomic tests than tests with less well-established clinical utility. Contrary to our hypothesis, medical oncologists, rather than pathologists or other providers, ordered the vast majority of tests. In addition, we found lower levels of reported genomic test use among oncologists working in nonprofit integrated systems than hospital-based oncologists or those in office-based single-specialty groups.

Although genomic testing is guideline endorsed for thousands of patients yearly, prior work has shown that there is variation in genomic care delivery. Despite oncologists’ higher reported use of guideline-endorsed genomic tests than tests that are not guideline endorsed, it is notable that a sizable minority of oncologists reported relatively low use of guideline-endorsed tests. This finding is in line with our prior work that suggested that some oncologists may fail to recommend genomic testing even when it is indicated.6

Similar to prior work,7 we found variation in test use across different practice settings. Oncologists who practice in nonprofit integrated health systems had lower rates of genomic test use compared with oncologists in hospital-based settings. Although this tendency toward lower test use may improve care if tests lack established clinical utility, our findings are striking because they also hold for guideline-endorsed tests. A large national study found that women who were enrolled in health maintenance organization systems were significantly less likely to receive BRCA testing than those in point-of-service insurance plans.18 Because we asked oncologists about general test use and cannot verify whether testing was appropriate, it is possible that the higher use rates reported by oncologists in hospital-based settings may reflect inappropriately high use rather than optimal rates. However, variation in cancer care by practice type is a well-described phenomenon, and some evidence suggests that hospitals or practices with a medical school or teaching affiliation and those that participate in NCI clinical research cooperative groups may provide guideline-concordant care more frequently than practices without those affiliations.9,19-22

Reasons for oncologists’ low reported genomic test use may include lack of test availability, unfamiliarity with testing benefits, a high proportion of patients who may not benefit from testing (eg, patients with early- or late-stage disease, depending on indication), inadequate tissue for testing, patient refusal, or lack of access to targeted clinical trials. However, a pressing question is whether there are system-level interventions that can improve genomic care delivery. One potential way to reduce unwanted variation may be to offer widespread reflexive testing, that is, testing automatically performed by pathology, for predictive somatic tests that are guideline endorsed. Reflexive testing in other settings, for example, HER2 amplification in breast cancer, has resulted in high utilization rates.23,24 Oncologists in our study reported that they usually requested or ordered most genomic tests. This finding was true for somatic tests, where reflexive testing might be most appropriate, as well as germline tests, which may be less well suited for reflexive testing because of the need for blood or saliva collection and an informed consent discussion. One context in which reflexive testing may be gaining ground is in MMR/MSI testing. MMR/MSI testing is one way to identify patients with CRC who should be considered for a familial cancer risk evaluation and germline testing, and it may be an emerging marker for immunotherapy response.25,26 Reflexive testing for other somatic alterations, such as EGFR testing in metastatic lung adenocarcinoma, could potentially increase the likelihood that all patients who have mutations are identified quickly. Rapid identification of actionable alterations is essential when treatment decisions are time sensitive. A Canadian study piloted reflexive testing of EGFR and ALK in lung adenocarcinoma and found that reflexive testing improved test completion rates (EGFR [86% to 96%]; ALK [83% to 97%]) and reduced EGFR testing turnaround times.27 A study by Schink et al28 found that reflexive testing for EGFR, ALK, and KRAS for NSCLC (all three at diagnosis [35%] or sequential [22%]) was more common in NCI Designated Centers than testing on the basis of oncologists’ orders (43%). Although such efforts are promising, there may be considerable barriers to broad implementation of reflexive testing. Pathologists may be unable to determine whether reflexive testing is indicated if essential clinical data are inconsistently entered into electronic health records or are unavailable at the time of testing. In addition, the rapidly changing reimbursement landscape may make some pathologists reluctant to institute reflexive testing without linked orders from the treating physician. An alternative approach may be implementation of oncologist-directed clinical decision support tools in the electronic health record to consider testing. Finally, there are differing beliefs about who should be responsible for choosing appropriate genomic tests. Miller et al10 found that 73% of physicians thought that referring clinicians should play a role in determining the choice of cancer genomic tests, whereas only 31% of laboratory professionals thought that referring clinicians should play that role.

Our study showed that oncologists are the providers who most frequently order germline LS testing. Our prior work has shown that some oncologists are more familiar with somatic testing than germline testing, and they face challenges when integrating germline testing into care.29 If oncologists are ordering the majority of germline tests, it is essential that they understand core concepts in germline genetics and have adequate support from genetics professionals when needed. Furthermore, as marketing of genomic tests to oncologists and patients has become a prevalent factor with the potential for shaping behavior for non–guideline-endorsed tests, for example, OncotypeDx testing for CRC,30,31 it is essential that oncologists have access to accurate empirical data and guidelines that define the optimal role of germline and somatic testing in care.

Study strengths include studying oncologists from diverse practice and geographic settings, a relatively high survey response rate, and the investigation of a range of genomic tests for 2 cancer types. Our study is limited by self-reported testing and the possibility of recall bias as well as a lack of information on the clinical context in which testing was performed, which limited our ability to determine the appropriateness of the reported testing. In addition, we did not assess the relationships between oncologists’ genomic confidence and test use. Although all survey research is subject to the possibility of social desirability bias, we questioned oncologists about both guideline- and non–guideline-endorsed technologies to minimize the likelihood that social desirability would play a role in their responses. Finally, cancer genomics is a rapidly evolving field and our findings may not reflect current practice.

In the era of precision medicine, cancer risk reduction and treatment decisions are increasingly made on the basis of genomic information. Understanding how genomic testing is used in practice is an essential first step in efforts to ensure that all individuals who can benefit from personalized cancer care receive the testing they need. Although oncologists’ discrimination between high-evidence and low-evidence tests is reassuring, we still found low use of some guideline-endorsed tests, particularly in nonprofit integrative systems. Further research in specific clinical contexts is needed to determine whether the observed variation is associated with higher- or lower-quality cancer care. Efforts to increase appropriate test use, such as reflexive testing for somatic alterations with known clinical utility, may help to optimize the delivery of precision cancer care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank all of the oncologists and patients who participated in the CanCORS study. Supported Grant No. 5U01-CA093344-08 from the National Cancer Institute to the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium Statistical Coordinating Center. S.W.G. was also supported by the American Cancer Society (120529-MRSG-11-006-01-CPPB) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (U01-HG006492). N.L.K. is also supported by Grant No. K24-CA181510 from the National Cancer Institute.

Appendix

Supplemental Methods

Population

The target population included medical oncologists who cared for patient participants in Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS). The CanCORS patient cohort is a population-based cohort of individuals who are diagnosed with lung or colorectal cancer in 2003 to 2005 at one of the participating sites (eight counties in Northern California, Los Angeles County, the state of Iowa, the state of Alabama, 22 counties in central/eastern North Carolina, five integrated delivery systems, and 10 Veterans Administration Medical Centers). CanCORS participants are similar to patients who were diagnosed with cancer in the United States as a whole.14 Providers were eligible if they were identified as providing chemotherapy in the CanCORS I (baseline) patient survey or CanCORS II (follow-up) advanced cancer survey (conducted in 2010 to 2011), physicians who self-identified as a medical oncologist in the CanCORS I physician survey, and medical oncologists who were identified in the CanCORS I or CanCORS II medical record abstractions. Physicians were ineligible if they were deceased, no longer in practice, did not care for patients with colorectal or lung cancer, or were not medical oncologists.

Study Procedures

In June to August 2012, physicians were mailed a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was accompanied by a cover letter cosigned by the Director of the National Cancer Institute and the Medical Director of the American Cancer Society. Surveys were mailed by first class mail with a stamped, preaddressed return envelope. Physicians were also given the option of responding to the survey via a secure Web site after logging in with a username and password. Each survey was coded with a unique identifier to be used to link providers with patients and for follow-up of those who did not respond. Each mailing also contained a $50 check incentive.

Three weeks after the initial mailing, another copy of the survey and cover letter was sent by first class mail to all who did not respond. Approximately two weeks later, a research assistant placed phone calls to the offices of physicians who did not respond to verify that the survey had been received, encourage physicians to complete and return it, and offer to mail or fax a replacement questionnaire. Research assistants also verified the specialty of nonresponding physicians. Up to four attempts were made to reach each nonresponding physician. In April to May 2013, a third mailing of the survey and cover letter was sent to physicians who did not respond with an additional $50 check.

For Web-based survey responses (10% of responses), data were entered directly into the Statistical Coordinating Center database from the Web survey instrument. For paper survey responses, surveys were reviewed for legibility before data entry, then data were entered by experienced staff at the Statistical Coordinating Center into a Web version of the instrument specifically designed for data entry.

Response Rates

There were no significant differences between those who did and did not respond in terms of gender, years since medical school graduation, whether they graduated from a US or Canadian medical school, or their participating CanCORS site.

Table A1.

Characteristics of Medical Oncologists Participating in the 2012 CanCORS II Survey (N = 337)

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Stacy W. Gray, Benjamin Kim, Katherine L. Kahn, David A. Haggstrom, Nancy L. Keating

Collection and assembly of data: Nancy L. Keating

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Medical Oncologists’ Experiences in Using Genomic Testing for Lung and Colorectal Cancer Care

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jop/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Stacy W. Gray

No relationship to disclose

Benjamin Kim

Employment: Genentech

Lynette Sholl

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Mirati Therapeutics

Angel Cronin

No relationship to disclose

Aparna R. Parikh

Employment: Genentech

Carrie N. Klabunde

No relationship to disclose

Katherine L. Kahn

No relationship to disclose

David A. Haggstrom

No relationship to disclose

Nancy L. Keating

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology–Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: Breast and ovarian. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_screening.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology–Non-small cell lung cancer. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology–Colon cancer. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0056. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Pujol P, Lyonnet DS, Frebourg T, et al. Lack of referral for genetic counseling and testing in BRCA1/2 and Lynch syndromes: A nationwide study based on 240,134 consultations and 134,652 genetic tests. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141:135–144. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2669-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wideroff L, Freedman AN, Olson L, et al. Physician use of genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: Results of a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:295–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parikh AR, Keating NL, Liu PH, et al: Oncologists’ selection of genetic and molecular testing in the evolving landscape of stage II colorectal cancer. J Oncol Pract 12:e308-e319, 259-260, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Webster J, Kauffman TL, Feigelson HS, et al. CERGEN study team KRAS testing and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor treatment for colorectal cancer in community settings. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:91–101. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter GC, Landsman-Blumberg PB, Johnson BH, et al. KRAS testing of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in a community-based oncology setting: A retrospective database analysis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34:29–36. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0146-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynch JA, Khoury MJ, Borzecki A, et al. Utilization of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) testing in the United States: A case study of T3 translational research. Genet Med. 2013;15:630–638. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller FA, Krueger P, Christensen RJ, et al. Postal survey of physicians and laboratories: practices and perceptions of molecular oncology testing. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:131–146. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray SW, Hicks-Courant K, Cronin A, et al. Physicians’ attitudes about multiplex tumor genomic testing. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1317–1323. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307:1801–1802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, et al. Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2992–2996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catalano PJ, Ayanian JZ, Weeks JC, et al. Cancer Care Outcomes Research Surveillance Consortium Representativeness of participants in the cancer care outcomes research and surveillance consortium relative to the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Med Care. 2013;51:e9–e15. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318222a711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kehl KL, Gray SW, Kim B, et al. Oncologists’ experiences with drug shortages. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e154–e162. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.000380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Regression Analysis of Count Data. (ed 2) Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Association for Public Opinion Research: Standard definitions: Final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. http://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf

- 18.Levy DE, Byfield SD, Comstock CB, et al. Underutilization of BRCA1/2 testing to guide breast cancer treatment: black and Hispanic women particularly at risk. Genet Med. 2011;13:349–355. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182091ba4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsons HM, Begun JW, McGovern PM, et al. Hospital characteristics associated with maintenance or improvement of guideline-recommended lymph node evaluation for colon cancer. Med Care. 2013;51:60–67. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318270ba0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlton ME, Hrabe JE, Wright KB, et al. Hospital characteristics associated with stage II/III rectal cancer guideline concordant care: Analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results-Medicare data. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1002–1011. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-3046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldsmith B, Dietrich J, Du Q, et al. Variability in access to hospital palliative care in the United States. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1094–1102. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch JA, Berse B, Petkov V, et al. Implementation of the 21-gene recurrence score test in the United States in 2011. Genet Med. 2016;18:982–990. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goddard KA, Bowles EJ, Feigelson HS, et al. Utilization of HER2 genetic testing in a multi-institutional observational study. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18:704–712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haas JS, Phillips KA, Liang S-Y, et al. Genomic testing and therapies for breast cancer in clinical practice. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:e1s–e7s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000299. (Suppl 3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 Blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao Y, Freeman GJ. The microsatellite instable subset of colorectal cancer is a particularly good candidate for checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:16–18. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menjak IB, Winterton-Perks Z, Raphael S, et al: Successful completion of EGFR/ALK testing in non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (non-sq NSCLC) with the implementation of reflex testing (RT) by pathologists. J Clin Oncol 34, 2016 (suppl 7S; abstr 93)

- 28.Schink JC, Trosman JR, Weldon CB, et al. Biomarker testing for breast, lung, and gastroesophageal cancers at NCI designated cancer centers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju256. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray SW, Park ER, Najita J, et al. Oncologists’ and cancer patients’ views on whole-exome sequencing and incidental findings: Results from the CanSeq study. Genet Med. 2016;18:1011–1019. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray SW, Abel GA. Update on direct-to-consumer marketing in oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:124–127. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray SW, Cronin A, Bair E, et al. Marketing of personalized cancer care on the web: An analysis of Internet websites. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv030. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]