Abstract

Certain caspase-8 null cell lines demonstrate resistance to Fas-induced apoptosis, indicating that the Fas/FasL apoptotic pathway may be caspase-8-dependent. Some reports, however, have shown that Fas induces cell death independent of caspase-8. Here we provide evidence for an alternative, caspase-8-independent, Fas death domain-mediated apoptotic pathway. Murine 12B1-D1 cells express procaspase-3, -8, and -9, which were activated upon the dimerization of Fas death domain. Bid was cleaved and mitochondrial transmembrane potential was disrupted in this apoptotic process. All apoptotic events were completely blocked by the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK, but not by other peptide caspase inhibitors. Cyclosporin A (CsA), which inhibits mitochondrial transition pore permeability, blocked neither pore permeability disruption nor caspase activation. However, CsA plus caspase-8 inhibitor blocked all apoptotic events of 12B1-D1 induced by Fas death domain dimerization. Our data therefore suggest that there is a novel, caspase-8-independent, Z-VAD-FMK-inhibitable, apoptotic pathway in 12B1-D1 cells that targets mitochondria directly.

INTRODUCTION

Fas (CD95, APO-1), a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family, is a widely expressed cell death receptor that plays a critical role in the regulation of the immune system and tissue homeostasis [1, 2]. Fas or Fas ligand (FasL) mutations in humans and mice cause syndromes of massive lymphoproliferation and autoantibody production [1]. Fas-induced apoptosis is a major mechanism in cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-mediated cytolysis [3].

Fas death domain (FasDD) is an approximately 80 amino acid intracellular motif of Fas that is critical for signaling apoptosis [4]. The activation of Fas by FasL or by agonistic antibody leads to the trimerization of FasDD, which consequently recruits FADD (Fas-associated protein with death domain) or MORT1, and caspase-8, forming the so-called death-inducing signal complex (DISC) [5]. Formation of DISC leads to activation of caspase-8, an initiator of downstream apoptotic processes that include the activation of caspase-3, -6, and -7 and loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential (MTP) [6].

Caspase-8 plays a key role in Fas-induced apoptosis [7, 8, 9]. Certain transgenic mice or cell lines deficient in caspase-8 have been shown to be resistant to Fas-induced apoptosis [10, 11], suggesting that caspase-8 may be essential in Fas-mediated apoptosis. Reports suggest that there may be two alternative Fas signaling pathways [12]. In the Fas “type I” cells, relatively large amounts of caspase-8 are recruited to DISC upon receptor cross-linking, resulting in the activation of caspase-8. This initiates a rapid apoptotic signal by directly activating downstream effector caspases through proteolytic cleavage, as well as by triggering mitochondrial damage leading to a proteolytic cascade. In Fas “type II” cells, the relatively slowly activated caspase-8 mediates downstream apoptotic events mainly by inducing mitochondrial damage [12]. Recently, Yang et al showed that Fas could engage an apoptotic pathway independent of FADD and caspase-8 [13]. Fas activation induced Daxx to interact with apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1). ASK1’s activated kinase activity resulted in caspase-independent activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), leading to cell death [14, 15]. In addition, several reports have now shown that Fas signaling can trigger an alternative, caspase-8-independent necrotic cell death pathway [16, 17, 18]. Taken together, these results indicate that Fas-mediated cell death is much more complicated than originally thought.

In this study, using a BCR-ABL+ leukemia cell line 12B1-D1, we have demonstrated that a broad-spectrum peptide caspase inhibitor, Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase inhibitor), completely blocked FasDD-mediated cell death. Peptide caspase inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK (casp-8 inhibitor) or Z-DEVD-FMK (casp-3 inhibitor) blocked neither the disruption of MTP nor chromosomal DNA fragmentation after activation of FasDD. However, all apoptotic events were completely blocked when 12B1-D1 cells were pretreated with cyclosporin A (CsA) and casp-8 inhibitor followed by dimerization of FasDD. This suggests that FasDD triggers a novel caspase-8-independent apoptotic pathway in the 12B1-D1 leukemia cell line.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-caspase-3 (clone 46) and anti-caspase-7 (clone 10-1-62) antibodies were purchased from BD PharMingen (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Rabbit anti-caspase-8 polyclonal antibody was from StressGen Biotechnologies (Victoria, BC, Canada). Anti-caspase-9 antibody (clone 9CSP02) was from NeoMarkers (Fremont, Calif). Goat anti-human/mouse BID antibody and anti-caspase-10 antibody (clone Mch 2) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn). Cyclosporin A was from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo). Peptide caspase inhibitors, benzyloxycarbonyl Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethylketone (abbreviated Z-VAD-FMK) pan-caspase inhibitor, Z-WEHD-FMK caspase-1 inhibitor, Z-VDVAD-FMK caspase-2 inhibitor, Z-DEVD-FMK caspase-3 inhibitor, Z-YVAD-FMK caspase-4 inhibitor, Z-VEID-FMK caspase-6 inhibitor, Z-IETD-FMK caspase-8 inhibitor, Z-LEHD-FMK caspase-9 inhibitor, Z-AEVD-FMK caspase-10 inhibitor, Z-LEED-FMK caspase-13 inhibitor, and Z-FA-FMK control faux inhibitor, were all from R&D Systems. 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6[3]) was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Ore).

Determination of caspase activities

Caspase activities from cytosolic extracts were measured using a flurometric assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems). In brief, 12B1-D1 cells were collected by centrifugation (1000 ×g, 5 minutes, 4°C). Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and resuspended in chilled lysis buffer. After 10 minutes on ice, the supernatant was collected following centrifugation (10 000 ×g) and was assayed for protein content using the bicinchonic acid reagent (Pierce, Rockford, Ill). For caspase activity measurements, cell extract (50 μg) was incubated at 37°C in the kit’s reaction buffer containing the substrates Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-amino-4-trifluoromethyl courmarin (DEVD-AFC), Ile-Glu-Thr-Asp-amino-4-trifluoromethyl courmarin (IETD-AFC), or Leu-Glu-His-Asp-amino-4-trifluoromethyl courmarin (LEHD-AFC). After 1.5 to 2 hours incubation at 37°C, the fluorescence intensity (excitation at 390 nm, emission at 510 nm) was measured using a microplate fluorometer (Labsystems, Franklin, Mass).

Flow cytometry analysis

Annexin V-FITC/PI staining of apoptotic cells was previously described [19]. To evaluate MTP disruption, the cationic lipophilic fluorochrome DiOC6[3] was used [20]. Cells were incubated with 40 nM DiOC6[3] for 15 minutes at 37°C. Alternatively, MTP was measured using a DePsipher kit (R&D Systems) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

DNA fragmentation assay

Nucleosomal DNA fragmentation was analyzed as described previously [19].

Immunoblotting

The cleavage of Bid and several caspases were detected by western blotting as described previously [19]. Briefly, lysates containing 25 μg of protein were separated by electrophoresis through 15% SDS-PAGE gels and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Equal loading was confirmed by Ponceau S staining of the membranes. Caspase-3, -7, -9, -10, and Bid were detected using relevant primary antibodies and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Chemicon, Temecula, Calif) followed by color deposition of the substrates NBT/BCIP (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind).

RESULTS

Caspase activation and apoptosis induction of 12B1-D1 cells after dimerization of engineered FasDD

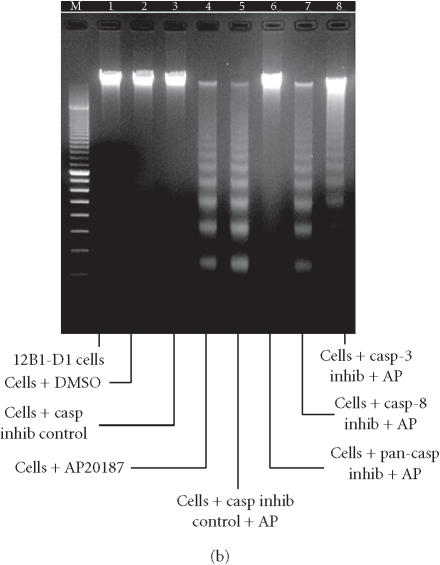

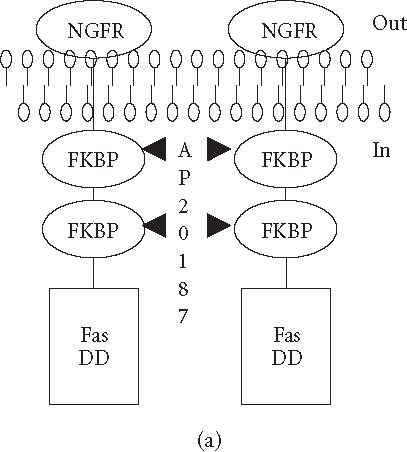

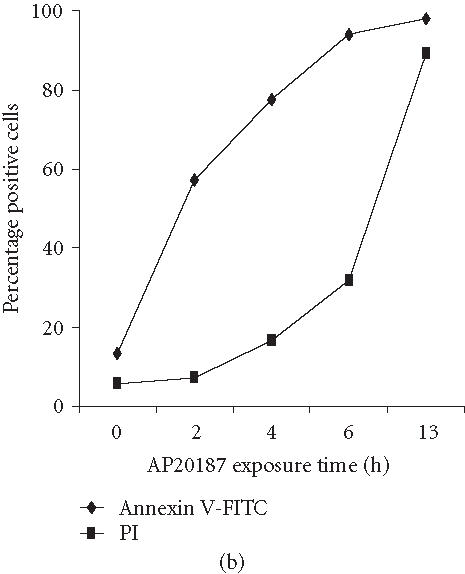

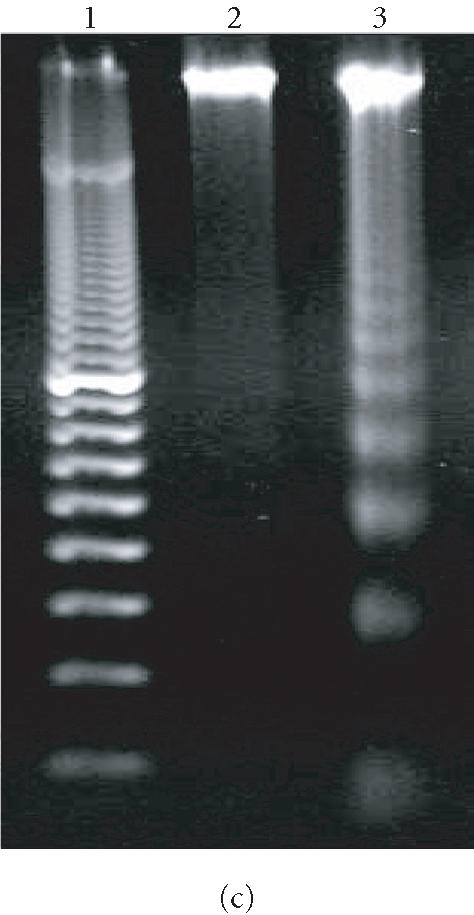

We have previously reported that the BCR-ABL+ cell line 12B1 does not express Fas protein on its surface and consequently fails to undergo apoptosis in response to anti-Fas antibody [19]. Therefore, we stably transfected 12B1 cells with plasmid DNA encoding a fusion protein that consists of the extracellular domain of the human low affinity nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR), two copies of mutant FK506 binding proteins (FKBP), and the FasDD (see [19] and Figure 1a). One clone, 12B1-D1, was further studied. Treatment of 12B1-D1 cells with the semisynthetic FK506 derivative AP20187 resulted in dimerization of FasDD and rapid induction of apoptosis [19]. More than 80% of the cells became annexin V-FITC positive within 4 to 6 hours of 40 nM AP20187 treatment (Figure 1b). In addition, the chromosomal DNA was cleaved into 200-bp fragments, a typical feature of apoptosis, after 6 hours AP20187 treatment (Figure 1c). The opening of mitochondrial pores is an early event of many types of apoptosis, leading to the depolarization of MTP. We used the potential-sensitive mitochondrial probe DiOC6[3] for the cytofluorometric determination of MTP during FasDD-induced apoptosis. Treatment of 12B1-D1 cells with AP20187 resulted in a marked decrease in the retention of DiOC6[3] within 3 hours and more than 70% of cells lost MTP within 5 hours (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

“Death construct” and apoptosis induction of 12B1-D1 cells by AP20187 treatment. (a) Transmembrane fusion protein consisting of a low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR) accessible on the cell surface, two mutant FK506-binding protein (FKBP) domains, and a Fas death domain (FasDD) intracellularly. AP20187 serves to dimerize FKBP domains, thus dimerizing FasDD. (b) 12B1-D1 cells were treated with 40 nM AP20187 for the indicated time, washed, and then stained with Annexin V and PI. (c) DNA fragmentation analysis. Lane 1, 100-bp ladder; lane 2, DNA extracted from 12B1-D1 cells; lane 3, DNA extracted from 12B1-D1 cells that have been treated with AP20187 for 6 hours. (d) 12B1-D1 cells were treated with AP20187 for the indicated time, washed, and then stained with mitochondrial probe DiOC6[3]. The fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry.

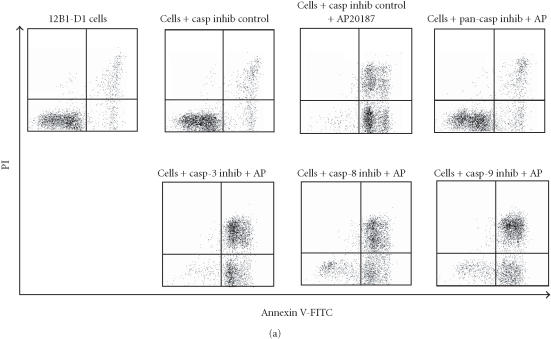

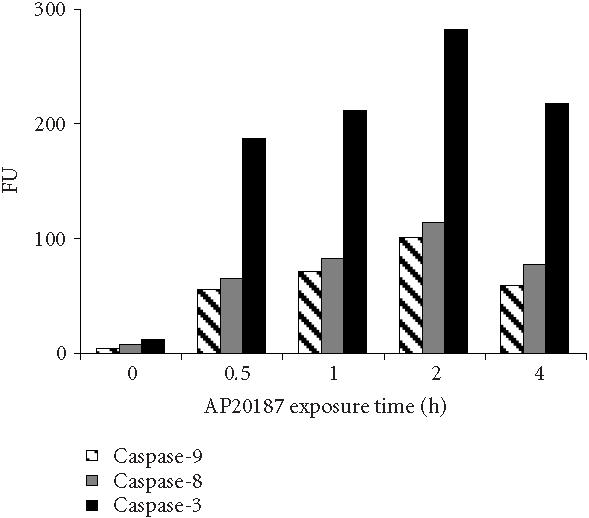

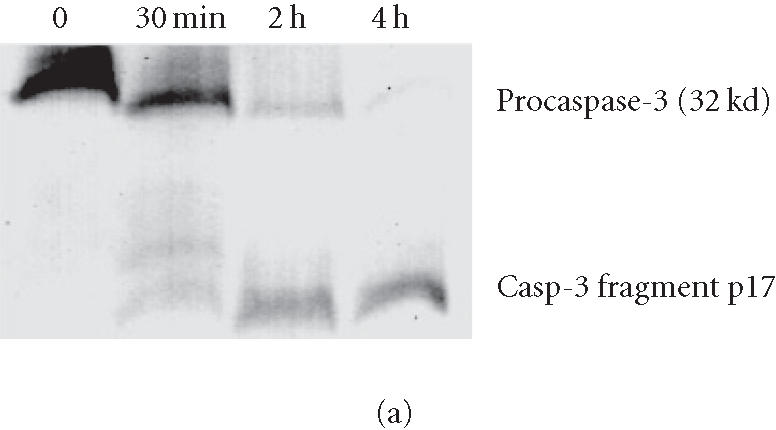

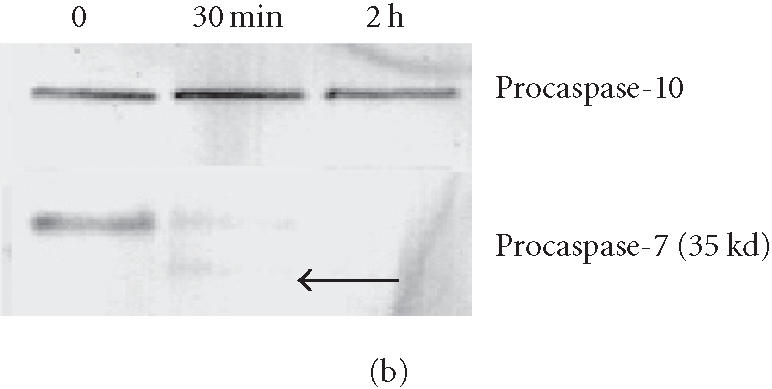

To analyze caspase activities after AP20187 treatment, we used fluorochrome-conjugated caspase specific peptide substrates, LEHD-AFC, IETD-AFC, or DEVD-AFC for caspase-9, -8, or -3, respectively. All three caspases were activated within 30 minutes of AP20187 treatment, and reached maximum activity after 2 hours as judged by increasing fluorescence intensity (Figure 2), following caspase cleavage of substrates and release of the fluorochrome AFC. We also analyzed caspase activation during AP20187-induced apoptosis by western blot (Figure 3). Procaspase-3, a main effector caspase, began to be cleaved within 30 minutes of AP20187 treatment (Figure 3a). Longer exposure of 12B1-D1 cells to AP20187 increased the intensity of a 17-kd fragment. Effector caspases procaspase-7 (35-kd protein, Figure 3b) and procaspase-9 (46–48-kd protein to 37-kd fragment, Figure 3c) were also cleaved within 30 minutes of AP20187 treatment. Consistent with another report [10], we found that although caspase-10 was expressed in 12B1-D1 cells, it was not proteolytically cleaved (Figure 3b).

Figure 2.

12B1-D1 caspase activities after AP20187 treatment. 12B1-D1 cells were treated with 40 nM AP20187 for the indicated time, then washed and lysed. Cell extracts were incubated at 37°C for 1.5 to 2 hours in a reaction buffer containing the substrates DEVD-AFC, IETD-AFC, or LEHD-AFC for caspase-3, -8, and -9, respectively. The activities of the listed caspases are shown as fluorescence units (FU) and measured using a microplate fluorometer.

Figure 3.

Procaspase cleavage after AP20187 treatment of 12B1-D1 cells. 12B1-D1 cells were treated with 40 nM AP20187 for the indicated time, then washed and lysed. Specific caspase cleavage was determined by western blotting using anti-caspase-3 (a), anti-caspase-7 and anti-caspase-10 (b) and anti-caspase-9 (c) antibodies.

The effect of oligopeptide caspase inhibitors on caspase activation and FasDD-mediated apoptosis

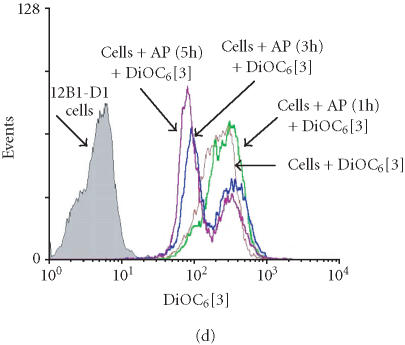

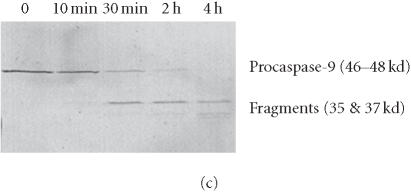

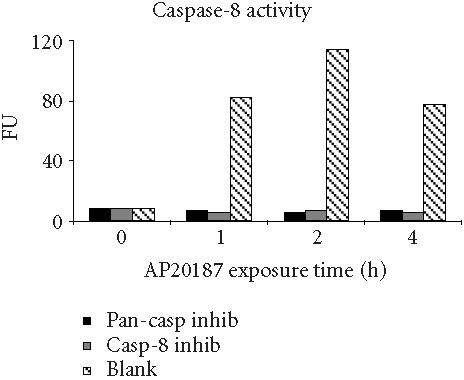

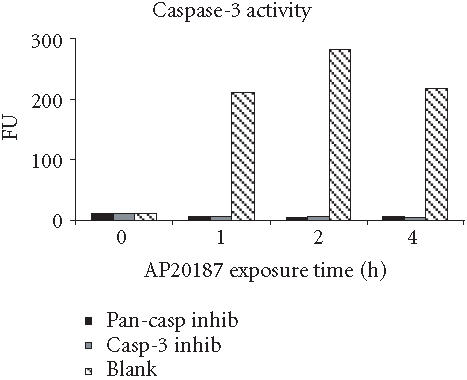

Irreversible oligopeptide caspase inhibitors have been used to study the role of different caspases in apoptosis. Z-IETD-FMK and Z-DEVD-FMK block caspase-8- and caspase-3-like proteases, respectively, whereas Z-VAD-FMK is a broad-range pan-caspase inhibitor [21, 22]. To test whether these potent and selective inhibitors could block FasDD-induced cell death in 12B1-D1 cells, cells were pretreated with 100 μM of pan-caspase inhibitor, casp-3 inhibitor, or casp-8 inhibitor followed by exposure to AP20187. As in other studies [23], the pan-caspase inhibitor completely prevented cells from undergoing apoptosis after activation of FasDD, as determined by the block of the phosphatidyl serine (PS) externalization (Figure 4a) and chromosomal DNA fragmentation (Figure 4b). Moreover, cells completely excluded the DNA dye propidium iodide (PI) even after 13 hours of AP20187 treatment (data not shown), suggesting that this pan-caspase inhibitor could completely block both FasDD-induced apoptosis and necrosis. Surprisingly, we found that the casp-8 or casp-3 inhibitors could not prevent all major apoptotic events induced by dimerization of FasDD, such as PS externalization (Figure 4a) and DNA fragmentation (Figure 4b). As expected, the cells eventually developed secondary necrosis (inability to exclude PI, data not shown). Apoptotic cell death occurred despite clear activity of the caspase inhibitors, as 12B1-D1 cells treated with the inhibitors showed no caspase-3- or 8-dependent-DEVD-AFC or -IETD-AFC cleaving activity in lysates (Figure 5). In addition, increasing concentrations of casp-8 inhibitor up to 200 μM did not alter its inability to block apoptosis, whereas pan-caspase inhibitor completely prevented apoptosis even at a substantial lower concentration (20 μM, data not shown). Other peptide caspase inhibitors for caspase-1, -2, -4, -6, -10, and -13 (see Materials and Methods for inhibitor details) also did not block the externalization of PS (data not shown), which occurs early during the apoptotic process [24].

Figure 4.

Apoptosis induction of 12B1-D1 cells in the presence of peptide caspase inhibitors. (a) 12B1-D1 cells were pretreated with the indicated peptide caspase inhibitors (100 μM) for 30 minutes followed by 6 hours of AP20187 exposure, then washed and stained with Annexin V and PI staining. The inhibitors used were caspase inhibitor control, Z-FA-FMK; pan-caspase inhibitor, Z-VAD-FMK; caspase-3 inhibitor, Z-DEVD-FMK; caspase-8 inhibitor, Z-IETD-FMK; and caspase-9 inhibitor, Z-LEHD-FMK. The x-axis on the flow diagrams is the fluorescence height of Annexin V-FITC, in units from 100 to 104; the y-axis is the fluorescence height of propidium iodide (PI) in the same scale. (b) DNA fragmentation analysis: M, 100-bp ladder; lane 1, DNA extracted from 12B1-D1 cells; lane 2, DNA from 12B1-D1 cells pretreated with DMSO, or (lane 3) control caspase inhibitor (inhibitors as listed in (a)); lane 4, DNA extracted from 12B1-D1 cells that have been treated with AP20187 for 6 hours; lane 5, DNA from cells pretreated with caspase inhibitor control, or (lane 6) with pan-caspase inhibitor, (lane 7) with casp-8 inhibitor, or (lane 8) with casp-3 inhibitor, each followed by 6 hours of AP20187 treatment.

Figure 5.

Caspase activities of 12B1-D1 cells in the presence of caspase inhibitors. 12B1-D1 cells, with or without pretreatment with the indicated caspase inhibitors (as listed in Figure 4a), were exposed to 40 nM AP20187 for the indicated time, then washed and lysed. Cell extracts were incubated at 37°C for 1.5 to 2 hours in a reaction buffer containing the substrates IETD-AFC (caspase-8 substrate, left), or DEVD-AFC (caspase-3 substrate, right). The fluorescence intensity (in fluorescence units, FU) was measured using a microplate fluorometer.

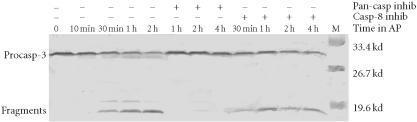

We examined the activation of caspase-3 after AP20187 treatment in the presence of pan-caspase inhibitor or casp-8 inhibitor (Figure 6) using western blotting to detect the altered migration of the activated form of caspase-3. Casp-8 inhibitor perhaps slightly delayed the cleavage of the proform of caspase-3 but did not appear to block it. In contrast, the pan-caspase inhibitor completely blocked caspase-3 cleavage.

Figure 6.

12B1-D1 caspase-3 cleavage in the presence of caspase inhibitors. 12B1-D1 cells, with or without pretreatment of indicated caspase inhibitors (as listed in Figure 4a), were treated with 40 nM AP20187 for the indicated time, then washed and lysed. Caspase-3 cleavage was determined by western blotting using anti-caspase-3 antibody. AP refers to the FKBP binding drug AP20187.

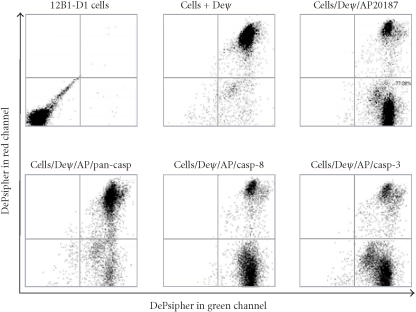

It has been reported that there are two types of cells in terms of Fas-mediated apoptosis [12], type I and type II cells. In type I cells, a significant amount of caspase-8 is rapidly activated after Fas/FasL ligation, resulting in a strong signal which can bypass mitochondria and directly target effector caspases, such as caspase-3. Total procaspase-8 expression (determined by western blotting) by 12B1-D1 cells is significant when compared to some other mouse tumor cell (data not shown). After dimerization of FasDD, the activity of caspase-8 increased dramatically within 30 minutes (Figure 2). Caspase-3 was also rapidly activated (Figures 2 and 3a). However, the majority of mitochondrial depolarization occurred relatively slowly (within 3 hours) (Figure 1d). These data indicate that 12B1-D1 cells are likely type I cells. We then assessed the MTP disruption after activation of FasDD in the presence of casp-8 or casp-3 inhibitor. We found that neither the casp-8 inhibitor nor the casp-3 inhibitor at 100 μM blocked the depolarization of MTP (Figure 7), even though caspase activity was completely blocked in the presence of the specific caspase inhibitor (Figure 5). Concentrations of caspase inhibitors up to 200 μM confirmed that they still could not block the depolarization of MTP (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Loss of MTP of 12B1-D1 cells after AP20187 treatment in the presence of casp-3 or -8 inhibitor. 12B1-D1 cells, with or without pretreatment of the indicated caspase inhibitors, were treated with 40 nM AP20187 for 4 hours, then washed and stained with DePsipher (Deψ). The cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. DePsipher aggregates in polarized membranes and is apparent in the red channel (y-axis in units from 100 to 104). Upon depolarization, DePsipher reverts to a monomeric form with fluorescence in the green channel (x-axis in units from 100 to 104). At equilibrium (normal resting state), DePsipher should fluoresce in both channels (cells + DePsipher).

Treatment of 12B1-D1 cells with casp-8 inhibitor and CsA reveals an alternative apoptotic death signaling pathway originating from Fas

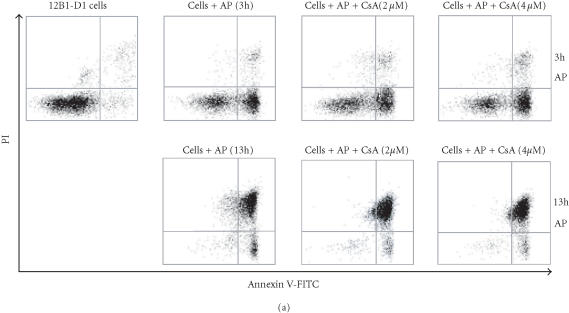

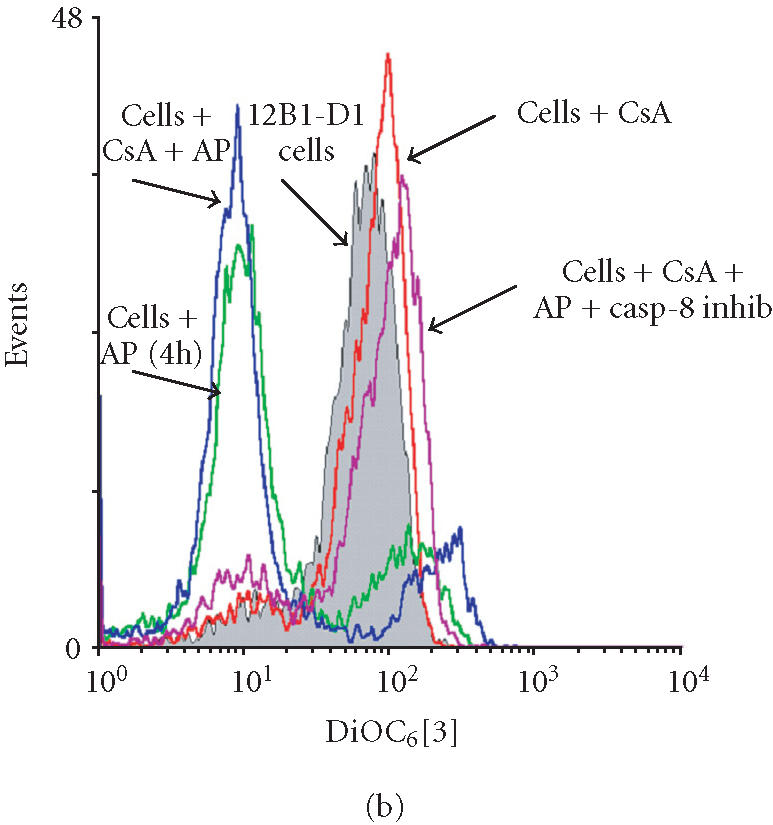

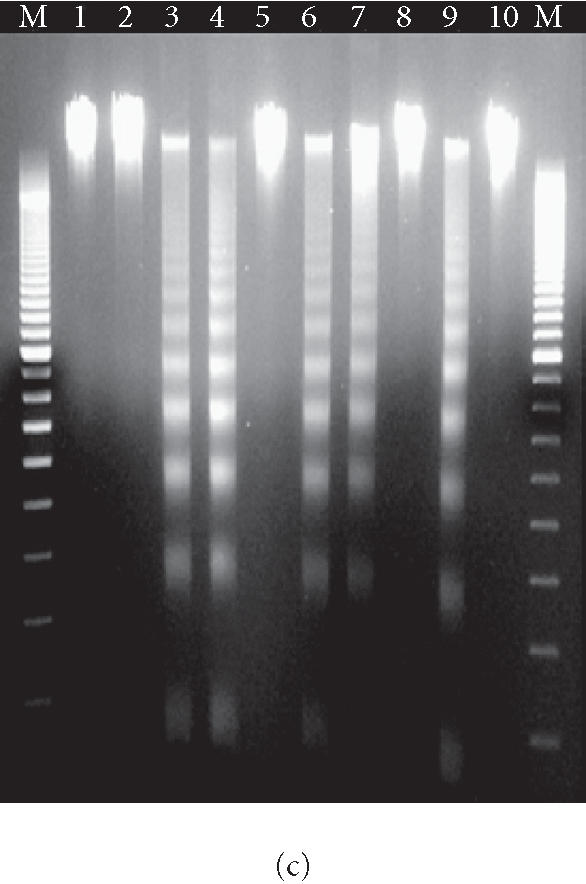

After oligomerization of FasDD, an adaptor protein FADD/MORT is recruited, which in turn recruits procaspase-8 resulting in the latter’s activation [4, 5]. Caspase-8 induces cells to undergo apoptosis by either activating downstream caspases through proteolytic cleavage [12] or triggering Bid cleavage to target mitochondria [23]. Our data documented that the dimerization of FasDD resulted in the depolarization of MTP even though caspase-8 activity was completely blocked (Figure 5), suggesting that there is a pan-caspase inhibitor-sensitive and casp-8 inhibitor-insensitive protease or proteases, activated by the dimerization of FasDD. This protease(s) may directly activate effector caspases or mitochondria, or both. It has been demonstrated that CsA can block the depolarization of MTP, which in turn prevents the release of cytochrome C and even prevents apoptotic cell death [25, 26, 27, 28]. We tested the ability of CsA to protect 12B1-D1 cells from apoptosis induced by AP20187 treatment. Treatment of 12B1-D1 cells with several different concentrations of CsA could not prevent the externalization of PS and cell death induced by AP20187 treatment (Figure 8a). In addition, treatment with CsA did not prevent the depolarization of MTP and DNA fragmentation (Figures 8b and 8c). Interestingly, when the 12B1-D1 cells were pretreated with CsA in combination with casp-8 inhibitor, followed by exposure to AP20187, the depolarization of MTP was completely blocked (Figure 8b), as evaluated by DiOC6[3] retention. Such pretreatment also blocked DNA fragmentation (Figure 8c). These data indicate that it is necessary to block both caspase-8 activity and mitochondrial damage in order to prevent apoptotic signaling initiated by FasDD oligomerization in 12B1-D1 cells.

Figure 8.

Apoptotic death of 12B1-D1 cells after AP20187 treatment in the presence of CsA and/or casp-8 inhibitor. (a) 12B1-D1 cells, with or without pretreatment of different concentrations of CsA, were treated with 40 nM AP20187 (AP) for the indicated time, then washed and stained with Annexin V and PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry. x- and y-axes are as in Figure 4a. (b) 12B1-D1 cells, with or without pretreatment with caspase inhibitors or CsA, were exposed to 40 nM AP20187 for 4 hours, then washed, stained with mitochondrial probe DiOC6[3], and analyzed by flow cytometry. (c) DNA was extracted from 12B1-D1 cells, treated as described below, for DNA fragmentation assay: M, 100-bp ladder; lane 1, DNA extracted from 12B1-D1 cells, or from 12B1-D1 cells that were pretreated with control caspase inhibitor Z-FA-FMK (lane 2); lane 3, DNA extracted from 12B1-D1 cells that have been treated with AP20187 for 6 hours; lane 4, DNA from cells that pretreated with Z-FA-FMK, or pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (lane 5), or casp-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK (lane 6), or casp-3 inhibitor Z-DEVD-FMK (lane 7), in each case pretreatment was followed by 6 hours of AP20187 treatment; lane 8, 12B1-D1 cells were treated with CsA, or CsA followed by AP20187 treatment (lane 9), or CsA together with casp-8 inhibitor followed by AP20187 treatment (lane 10).

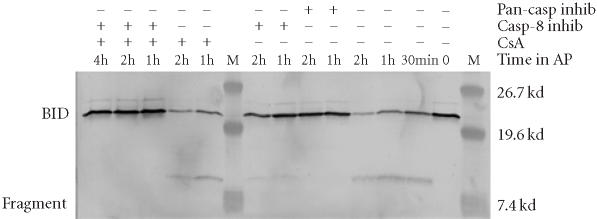

The finding that CsA in combination with casp-8 inhibitor completely blocks 12B1-D1 apoptosis after dimerization of FasDD suggests that the proposed novel protease(s) targets mitochondria directly. It has been shown that activated caspase-8 rapidly cleaves the Bcl family member Bid [23, 29, 30], resulting in a truncated form of the molecule (tBid). tBid is highly proapoptotic and targets mitochondria by inserting into their membrane, leading to disruption of transmembrane potential and release of cytochrome C [29]. To explore whether the proposed protease(s) could cleave Bid and consequently target mitochondria, we examined the Bid cleavage in 12B1-D1 cells. Consistent with previous reports [23, 31], Bid was cleaved following dimerization of FasDD (Figure 9). Bid cleavage started within 30 minutes of AP20187 treatment and a limited amount of Bid remained uncleaved after 2 hours (Figure 9). As expected, the pan-caspase inhibitor blocked the cleavage of Bid completely. In the presence of casp-8 inhibitor, Bid cleavage was significantly inhibited after 2 hours of AP20187 treatment, but not completely blocked (Figure 9). This result suggests that other protease(s) may play a role in the cleavage of Bid [23] in the presence of casp-8 inhibitor especially, since casp-8 inhibitor did not block FasDD-mediated apoptosis (Figure 4) and caspase-3 activation (Figure 6). Furthermore, CsA pretreatment exhibited no inhibitory effects on Bid cleavage (Figure 9). However, the combination of CsA with casp-8 inhibitor completely blocked the cleavage of Bid, suggesting that our proposed novel apoptotic pathway can bypass Bid and target the mitochondria directly (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Bid cleavage in 12B1-D1 cells in the presence of CsA or caspase inhibitors. 12B1-D1 cells, with or without pretreatment with CsA or the indicated caspase inhibitors, were exposed to 40 nM AP20187 for the indicated time, then washed and lysed. Bid cleavage was determined by western blotting using anti-Bid antibody.

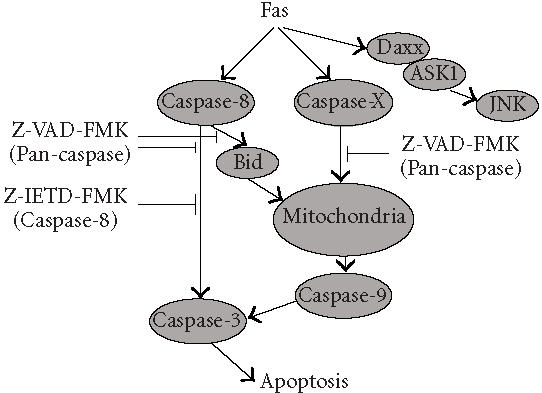

Figure 10.

Proposed caspase-8-independent pathway. Our findings indicate that FasDD oligomerization can trigger a novel caspase-8-independent apoptotic pathway. This pathway is activated by FasDD, but is independent of Bid and the proteolytic activity of caspase-8. It appears to target mitochondria directly by a Z-VAD-FMK-inhibitable mechanism.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that FasDD oligomerization can trigger a novel caspase-8-independent apoptotic pathway. This pathway is activated by FasDD, but is independent of Bid and the proteolytic activity of caspase-8. It appears to target mitochondria directly by a Z-VAD-FMK-inhibitable mechanism, suggesting the existence of a novel protease(s) that we are now attempting to identify.

The execution of most if not all apoptosis requires caspase activation [32]. Caspase-8 is one apical initial caspase and has been thought to be essential in Fas-mediated apoptosis [10, 11]. Ligand binding-induced trimerization of death receptors results in recruitment of the receptor-specific adapter protein FADD, which then recruits caspase-8. Activated caspase-8 is known to propagate the apoptotic signal either by directly cleaving and activating downstream caspases (so-called extrinsic pathway), or by cleaving the BH3-containing Bcl-2-interacting protein Bid, which leads to the release of cytochrome C from mitochondria, triggering the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway [29]. After triggering the oligomerization of FasDD in 12B1-D1 cells by AP20187, caspase-8 is activated rapidly. Other effector caspases, such as caspase-3 and -7, are also activated within 30 minutes of AP20187 exposure, which may result from direct cleavage and activation of caspase-3. While activated caspase-8 can propagate apoptotic signals and initiate the extrinsic death receptor pathway, it has also been shown that the mitochondria-mediated caspase-9 activation pathway (intrinsic pathway) amplifies Fas signaling through caspase-8-mediated cleavage of Bid and translocation into the mitochondria [23, 29]. In our study, we found that the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein Bid was cleaved, MTP was disrupted, and caspase-9 was activated after the activation of FasDD. This indicates that the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of caspase activation are extensively interconnected in 12B1-D1 cells.

Irreversible oligopeptide caspase inhibitors have been used extensively to study the role of caspases in apoptosis. Z-IETD-FMK and Z-DEVD-FMK block caspase-8- and caspase-3-like proteases, respectively, whereas Z-VAD-FMK is a broad-range caspase inhibitor [21, 22]. We observed that neither casp-8 inhibitor nor casp-3 inhibitor prevented FasDD-mediated apoptotic cell death in 12B1-D1, even at concentrations of 200 μM, whereas only 20 μM pan-caspase inhibitor completely blocked cell death. Both casp-3 and casp-8 inhibitors entered the cells effectively, as pretreatment of the cells with pan-caspase inhibitor, or either casp-3 or casp-8 inhibitor efficiently blocked cleavage of the fluorogenic substrate DEVD-AFC or IETD-AFC. A panel of other peptide caspase inhibitors (for caspase-1, -2, -4, -6, -9, -10, and -13) was also tested and did not block FasDD-induced apoptosis as determined by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining. Caspase-10 is a apical caspase [33] and can function independently of caspase-8 in initiating Fas- and TRAIL (tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) -mediated apoptosis [34]. Consistent with another report [10], we found that although caspase-10 is expressed in 12B1-D1 cells, it is not proteolytically cleaved and activated, even after 2 hours of AP20187 exposure, a time point when caspase-8 activity reached its maximum. In addition, the caspase-10 inhibitor Z-AEVD-FMK did not block 12B1-D1 cells from undergoing apoptosis as monitored by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining. Furthermore, the casp-8 inhibitor also has strong inhibitory activity for caspase-10 [22], since caspase-10 is highly homologous to caspase-8 [30, 35]. These findings indicate that caspase-10 is not involved in the novel apoptotic pathway that we are proposing.

Mitochondria play a critical role in mediating apoptotic signal transduction pathways [36]. Biochemical and structural changes of mitochondria in apoptosis include swelling, disruption of the outer membrane, depolarization, and the release of cytochrome C [36]. CsA is capable of blocking the depolarization of MTP, which in turn prevents cytochrome C release and even prevents apoptotic cell death [25, 26, 27, 28]. FasDD dimerization by AP20187 resulted in the disruption of mitochondrial outer membrane and loss of transmembrane potential as determined by both DiOC6[3] retention and DePsipher exclusion. This effect could not be blocked by pretreatment of 12B1-D1 cells with either casp-8 inhibitor or CsA. Growing evidence indicates that the extrinsic death receptor and intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathways are highly interconnected and Bid plays a major role in this connection [29]. Cytosolic Bid can be efficiently cleaved by activated caspase-8, and tBid then translocates from cytosol to the mitochondria membrane, resulting in disruption of its outer membrane [23]. We found that Bid was rapidly cleaved after the activation of FasDD, even when cells were pretreated with CsA. High levels of tBid may damage the mitochondrial outer membrane even if cells are pretreated with CsA. This may explain our finding that CsA pretreatment did not block the disruption of MTP. We noticed that pretreatment of 12B1-D1 cells with casp-8 inhibitor decreased the cleavage of Bid substantially but not completely after activation of FasDD. This finding raises the question again whether or not the casp-8 inhibitor completely blocked the proteolytic activity of caspase-8. Previous reports have shown that certain caspases other than caspase-8 have minor proteolytic activity towards Bid [23]. Our data demonstrated that caspases were activated and cells underwent apoptotic death after dimerization of FasDD by AP20187 when the cells were pretreated with casp-8 inhibitor. Pretreatment of cells with CsA and casp-8 inhibitor, however, completely blocked apoptotic cell death, as well as caspase activation and Bid cleavage, confirming that the proteolytic activity of caspase-8 was adequately inhibited by the inhibitor since CsA had no inhibitory effect on Bid cleavage. The fact that CsA in combination with casp-8 inhibitor completely blocked 12B1-D1 cells from undergoing apoptosis after dimerization of FasDD indicates that the protease/pathway that we proposed targets the mitochondria directly.

Although knockout data indicate that caspase-8 may be required for apoptosis induced by the death receptor Fas [10, 11] in certain cases, other reports have shown that Fas can induce cell death independent of caspase-8. Recently, Yang et al showed that Fas can engage an apoptotic pathway independent of FADD and caspase 8 [13]. They found that Fas activation induced Daxx interaction with apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1), leading to its activation and resulting in caspase-independent activation of JNK and cell death [14, 15]. This pathway, however, was not blocked by the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor, Z-VAD-FMK, distinguishing it from the pathway we are now proposing. More recently, several reports have shown that Fas signaling can trigger an alternative, caspase-8-independent necrotic cell death pathway. This pathway is not blocked by the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor, [16, 17] and that inhibitor even rendered the cells more sensitive to Fas-mediated cell death [18]. Our data show that the activation of FasDD resulted in the externalization of PS, disruption of MTP, and DNA fragmentation/laddering when caspase-8 proteolytic activity was completely blocked, suggesting that cells underwent a cell death with typical apoptotic features. In summary, our findings indicate that FasDD can trigger a novel caspase-8-independent apoptotic pathway. This pathway is activated by FasDD, is independent of Bid and the proteolytic activity of caspase-8, and targets mitochondria by a Z-VAD-FMK-inhibitable mechanism.

References

- 1.Rathmell J.C, Thompson C.B. The central effectors of cell death in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:781–828. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaux D.L, Korsmeyer S.J. Cell death in development. Cell. 1999;96(2):245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Parijs L, Abbas A.K. Role of Fas-mediated cell death in the regulation of immune responses. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8(3):355–361. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagata S. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis. Annu Rev Genet. 1999;33:29–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kischkel F.C, Hellbardt S, Behrmann I, et al. Cyto-toxicity-dependent APO-1 (Fas/CD95)-associated proteins form a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) with the receptor. EMBO J. 1995;14(22):5579–5588. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salvesen G.S, Dixit V.M. Caspases: intracellular signaling by proteolysis. Cell. 1997;91(4):443–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boldin M.P, Goncharov T.M, Goltsev Y.V, Wallach D. Involvement of MACH, a novel MORT1/FADD-interacting protease, in Fas/APO-1- and TNF receptor-induced cell death. Cell. 1996;85(6):803–815. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muzio M, Chinnaiyan A.M, Kischkel F.C, et al. FLICE, a novel FADD-homologous ICE/CED-3-like protease, is recruited to the CD95 (Fas/APO-1) death-inducing signaling complex. Cell. 1996;85(6):817–827. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cryns V, Yuan J. Proteases to die for. Genes Dev. 1998;12(11):1551–1570. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juo P, Kuo C.J, Yuan J, Blenis J. Essential requirement for caspase-8/FLICE in the initiation of the Fas-induced apoptotic cascade. Curr Biol. 1998;8(18):1001–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00420-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varfolomeev E.E, Schuchmann M, Luria V, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse Caspase 8 gene ablates cell death induction by the TNF receptors, Fas/Apo1, and DR3 and is lethal prenatally. Immunity. 1998;9(2):267–276. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80609-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scaffidi C, Fulda S, Srinivasan A, et al. Two CD95 (APO-1/Fas) signaling pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17(6):1675–1687. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang X, Khosravi-Far R, Chang H.Y, Baltimore D. Daxx, a novel Fas-binding protein that activates JNK and apoptosis. Cell. 1997;89(7):1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80294-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang H.Y, Nishitoh H, Yang X, Ichijo H, Baltimore D. Activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) by the adapter protein Daxx. Science. 1998;281(5384):1860–1863. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5384.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ko Y.G, Kang Y.S, Park H, et al. Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 controls the proapoptotic function of death-associated protein (Daxx) in the cytoplasm. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(42):39103–39106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105928200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holler N, Zaru R, Micheau O, et al. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat Immunol. 2000;1(6):489–495. doi: 10.1038/82732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumura H, Shimizu Y, Ohsawa Y, Kawahara A, Uchiyama Y, Nagata S. Necrotic death pathway in Fas receptor signaling. J Cell Biol. 2000;151(6):1247–1256. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vercammen D, Brouckaert G, Denecker G, et al. Dual signaling of the Fas receptor: initiation of both apoptotic and necrotic cell death pathways. J Exp Med. 1998;188(5):919–930. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng H, Zeng Y, Whitesell L, Katsanis E. Stressed apoptotic tumor cells express heat shock proteins and elicit tumor-specific immunity. Blood. 2001;97(11):3505–3512. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petit P.X, Lecoeur H, Zorn E, Dauguet C, Mignotte B, Gougeon M.L. Alterations in mitochondrial struc and function are early events of dexamethasone-induced thymocyte apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1995;130(1):157–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grutter M.G. Caspases: key players in programmed cell death. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10(6):649–655. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Calvo M, Peterson E.P, Leiting B, Ruel R, Nicholson D.W, Thornberry N.A. Inhibition of human caspases by peptide-based and macromolecular inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(49):32608–32613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Zhu H, Xu C.J, Yuan J. Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell. 1998;94(4):491–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin S.J, Reutelingsperger C.P, McGahon A.J, et al. Early redistribution of plasma membrane phosphatidylserine is a general feature of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus: inhibition by overexpression of Bcl-2 and Abl. J Exp Med. 1995;182(5):1545–1556. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narita M, Shimizu S, Ito T, et al. Bax interacts with the permeability transition pore to induce permeability transition and cytochrome c release in isolated mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(25):14681–14686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walter D.H, Haendeler J, Galle J, Zeiher A.M, Dimmeler S. Cyclosporin A inhibits apoptosis of human endothelial cells by preventing release of cytochrome C from mitochondria. Circulation. 1998;98(12):1153–1157. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.12.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradham C.A, Qian T, Streetz K, Trautwein C, Brenner D.A, Lemasters J.J. The mitochondrial permeability transition is required for tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated apoptosis and cytochrome c release. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(11):6353–6364. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugano N, Ito K, Murai S. Cyclosporin A inhibits H2O2-induced apoptosis of human fibroblasts. FEBS Lett. 1999;447(2-3):274–276. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin X.M. Signal transduction mediated by Bid, a pro-death Bcl-2 family proteins, connects the death receptor and mitochondria apoptosis pathways. Cell Res. 2000;10(3):161–167. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed J.C. Mechanisms of apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 2000;157(5):1415–1430. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64779-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng T.S, Hunot S, Kuida K, et al. Deficiency in caspase-9 or caspase-3 induces compensatory caspase activation. Nat Med. 2000;6(11):1241–1247. doi: 10.1038/81343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thornberry N.A. Caspases: key mediators of apoptosis. Chem Biol. 1998;5(5):97–103. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90615-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallach D, Varfolomeev E.E, Malinin N.L, Goltsev Y.V, Kovalenko A.V, Boldin M.P. Tumor necrosis factor receptor and Fas signaling mechanisms. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:331–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, Chun H.J, Wong W, Spencer D.M, Lenardo M.J. Caspase-10 is an initiator caspase in death receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(24):13884–13888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241358198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Earnshaw W.C, Martins L.M, Kaufmann S.H. Mammalian caspases: structure, activation, substrates, and functions during apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:383–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green D.R, Reed J.C. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 1998;281(5381):1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]