Abstract

In hybrid alkaline fly ash cements, a new generation of binders, hydration, is characterized by features found in both ordinary portland cement (OPC) hydration and the alkali activation of fly ash (AAFA). Hybrid alkaline fly ash cements typically have a high fly ash (70 wt % to 80 wt %) and low clinker (20 wt % to 30 wt %) content. The clinker component favors curing at ambient temperature. A hydration mechanism is proposed based on the authors’ research on these hybrid binders over the last five years. The mechanisms for OPC hydration and FA alkaline activation are summarized by way of reference. In hybrid systems, fly ash activity is visible at very early ages, when two types of gel are formed: C–S–H from the OPC and N–A–S–H from the fly ash. In their mutual presence, these gels tend to evolve, respectively, into C–A–S–H and (N,C)–A–S–H. The use of activators with different degrees of alkalinity has a direct impact on reaction kinetics but does not modify the main final products, a mixture of C–A–S–H and (N,C)–A–S–H gels. The proportion of each gel in the mix does, however, depend on the alkalinity generated in the medium.

Keywords: hybrid alkaline cement, alkaline activation, fly ash, geopolymer, descriptive hydration model, gel microstructure

1. Introduction

Modern construction is unthinkable without ordinary portland cement (OPC), the fundamental binder in concrete. According to CEMBUREAU data, some four billion tons of PC were manufactured worldwide in 2013 alone. With the use of fossil fuels to raise kiln sintering temperatures to around 1450 °C and the limestone decarbonation required to produce raw meal, the industry accounts for approximately 5%–8% of anthropogenic CO2 emissions [1].

Attempts to reduce its CO2 footprint by blending OPC with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), such as coal fly ash, metakaolin or blast furnace slag [2], have yielded pozzolanic cements with technical properties comparable to those of ordinary cement [3]. Nonetheless, such blended cements contain 70 wt % to 90 wt % OPC. On the opposite end of the spectrum are alkali-activated binders containing 0 wt % OPC. There the reactive solid is an aluminosilicate material prone to dissolution under highly alkaline conditions. Given the important role of aluminosilicate phases, generally speaking materials that hold promise as alkali-activated cements also exhibit pozzolanic activity in blended cements: i.e., coal fly ash [4,5] and metakaolin [6]. The hydration of these alkali-activated cements, also termed geopolymers, which has been studied in considerable detail over the last 10–15 years, has been shown to be governed by mechanisms that are different to OPC. The major difference between the two is that alkali activated cements are mixed not with water but highly alkaline chemicals [7,8,9]. In addition, in the case of fly ash, a moderately high curing temperature (60 °C to 90 °C) is required to ensure practical reaction kinetics [10].

Fly ash is the supplementary cementitious material most widely used, ton for ton. Taking OPC and alkali-activated fly ash (AAFA) as the two extremes on a spectrum, blended cements containing fly ash (pozzolanic cements) would represent the middle ground. The ceiling fly ash dry mass content in pozzolanic binders is usually set at 20% to 55% [11]. Because the pozzolanic reaction of fly ash is fairly slow, early age strength has been shown to be lower and setting times longer in cements with a high FA content than in other pozzolanic binders [12]. Attempts made to surmount these drawbacks include the use of quick-setting cement [13] or the addition of limestone to the mix [14,15].

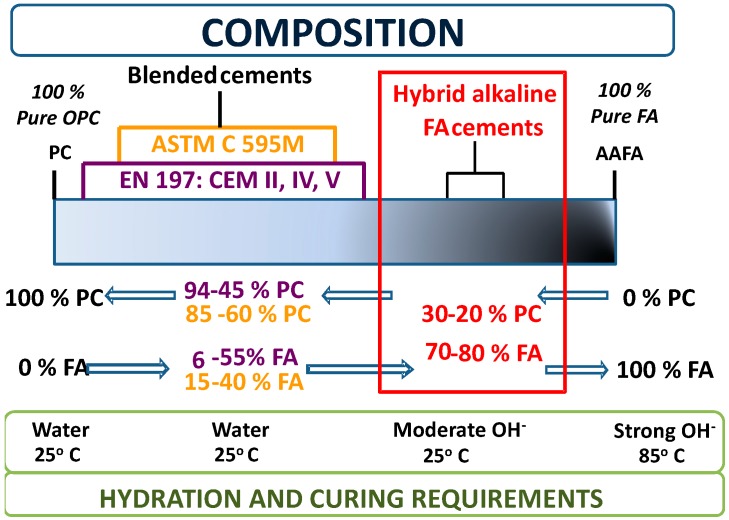

Alternatively, a suitable alkali may be used to enhance fly ash reactivity [16,17]. Research is underway at this time on what are known as ‘hybrid alkaline fly ash cements’ [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], typically binders with a low Portland cement and a fly ash content significantly higher than in blended pozzolanic cements. The source of the alkali may be a highly alkaline solution, used in lieu of mixing water, a solid or a dissolved Na/K compound. In all three cases, the hybrid alkaline cements react and can be cured at ambient temperature. These cements can also be regarded to lie in an intermediate position on the OPC/alkali activation of fly ash (AAFA) spectrum, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Position of hybrid alkaline fly ash cements on the pure Portland cement (PC)-pure alkali activation of fly ash (AAFA) spectrum, relative to pozzolanic fly ash cements.

While much research has been conducted on the mechanisms governing hydration in OPC [27,28,29], pozzolanic [30,31] and AAFA [32,33,34] cements, very little has been published on the hydration mechanisms in hybrid alkaline systems

This paper aims to describe the hydration mechanisms taking place in fly ash-high hybrid alkaline cements and define the main characteristics of the cementitious gel forming in those systems. Given the significant role of the nature of the alkaline admixture in such cements, it is also discussed hereunder.

2. Background

Inasmuch as hybrid alkaline cements may be regarded to lie somewhere between the two extremes defined by OPC and AAFA, a brief discussion of the hydration mechanisms present in the latter two systems is in order, applying the same methodology as subsequently used to describe the model proposed for hybrid cements.

2.1. Portland Cement (PC) Hydration

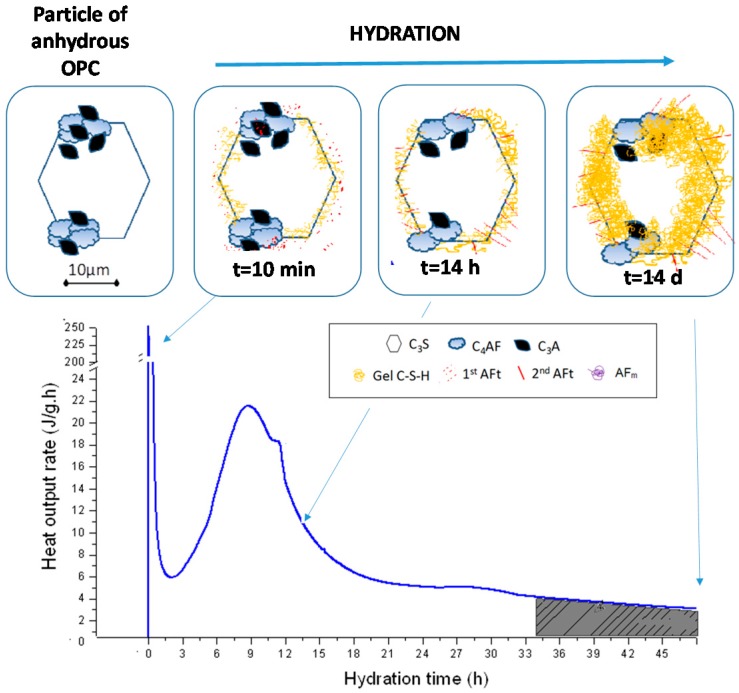

Portland cement clinker consists primarily in four reactive phases: Alite (C3S), belite (C2S), tricalcium aluminate (C3A) and ferrite (C4AF). The most reactive of these components are C3A [35,36] and C3S [37,38,39]. A single grain of cement may be divided into several regions containing different clinker phases. Figure 2 shows a widely accepted descriptive model [40] (first proposed by Scrivener in 1984) [41]. Figure 2, also reproduces a typical calorimetric analysis of OPC hydration for comparison.

Figure 2.

Descriptive model for poly-phase OPC grain hydration and a typical calorimetric curve for OPC hydration (grain drawings adapted from Scrivener as quoted in Taylor (1997) [27]).

Further to Figure 2, a very intense but short-lived exothermal peak generated by the rapid dissolution of the surfaces of C3S and C3A concurs with the initial wetting of cement grains. Clinker dissolution raises the liquid phase pH substantially, along with Ca2+, Al3+ and silicate ion concentrations. The sulfate present in the gypsum induces a decline in Al3+ concentration in the liquid phase due to the precipitation of tiny ettringite (AFt) prisms. C3A hydration is subsequently inhibited by the presence of sulfate ions. The reason advanced is that the AFt forms layers on the surface of the C3A grains, making it inaccessible to the liquid phase [40]. Early age precipitation of C–S–H or C–(A)–S–H gels on the surface of clinker grains also lowers effective clinker solubility and with it the rate of heat released to a characteristic minimum during the induction period.

While continuing at a much slower rate, clinker hydration does not stop altogether during the induction period. Ca and silicate ion concentration in the liquid phase gradually rises until large amounts of C–S–H gel precipitate, removing the Ca and silicate ions from the solution and favouring the resumption of C3S phase hydration [42,43]. That leads to the formation of large amounts of so-called ‘outer’ C–S–H gel, with the coalescence of cement particles to which cement paste setting is attributed [44]. This period of massive gel precipitation, termed the acceleration period, constitutes the predominant exothermal event in PC hydration after initial wetting.

As sulfate ion activity declines in the liquid phase, the C3A grain surfaces come into direct contact with the liquid and the reaction resumes, forming larger ‘secondary ettringite’ prisms. The resumption of C3A hydration is often visible in calorimetric data as a shoulder on the downward slope of the acceleration stage, although at times it is undistinguishable from the main acceleration/deceleration peak. ‘Inner’ C–S–H gel also gradually forms in this period.

As the amount of inner C–S–H gel rises, lowering sulfate availability, monosulfate (AFm) is favored over trisulfate (AFt) formation. Although the mechanism has yet to be accurately described, the larger AFt prisms appear to be unaffected, since as a rule the lower relative surface area renders larger crystals more stable than smaller ones [45,46]. The conversion of AFt to AFm or the reaction between C3A and AFt to form AFm is sometimes visible in the form of a low intensity, wide exothermal peak appearing between days 1 and 3. The fairly small amount of heat that continues to be generated even after three days can be attributed to the ongoing hydration of C3S grains, with the formation of more inner C–S–H gel. That process is related to the significant gains in compressive strength observed in PC pastes after the second day.

The nanostructure of the resulting C–S–H gel consists of a central layer of octahedrally orientated Ca–O units sandwiched by upper and lower layers of imperfect silicate tetrahedral chains. These chains are formed from units consisting of three tetrahedra in which two are linked by a third, the ‘bridging’ tetrahedron. The predominance of Q1 (end of chain) and Q2 (mid-chain) units in 29Si MAS NMR spectra confirms that the silicate chains in C–S–H gel are weakly polymerized [27,47,48].

2.2. Alkali-Activated Fly Ash Cement Hydration

As noted earlier, AAFA and OPC hydration are wholly different processes. Fly ash reactivity is based on the alkaline dissolution of disordered aluminosilicate networks. A large fraction of fly ash particles is characterized by a peculiar morphology: spheres that may or may not house other smaller spheres. The material consists of a vitreous phase with a few minority crystals such as quartz (5% to 13%), mullite (8% to 14%), hematite/magnetite (3% to 10%) and, on occasion, corundum or lime [49,50].

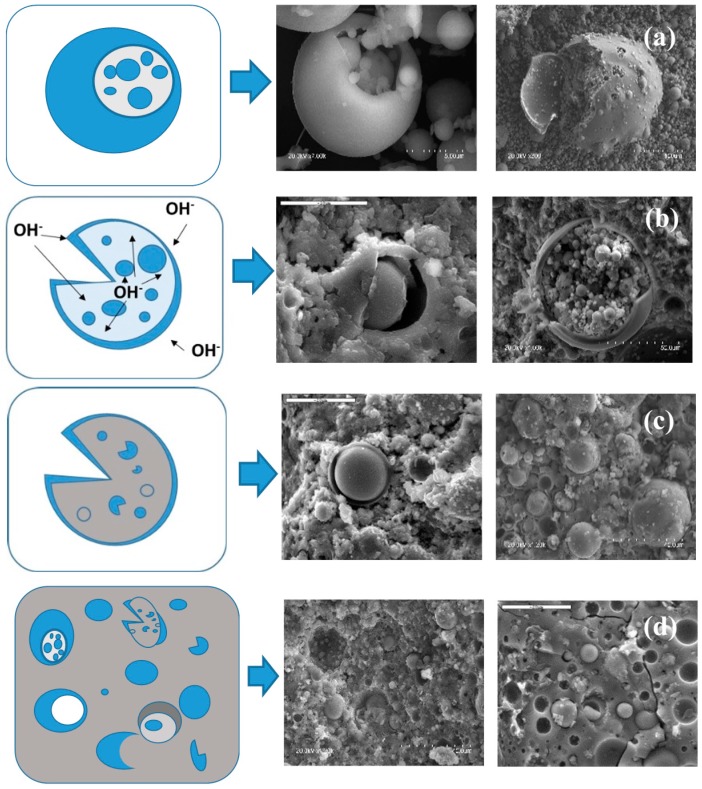

In 2005, Fernández and Palomo [7] proposed a conceptual model for the alkaline activation of fly ash (see Figure 3). The process would begin with a chemical attack on the ash surface, resulting in the formation of small cavities in the walls of the ash particles, exposing the tiny particles on the inside to the action of the alkalis. In this stage of the reaction the alkalis would attack from inside and outside the particles (Figure 3b). The ash would continue to dissolve and the reaction products generated inside and outside the ash crust would precipitate, covering the smaller unreacted spheres and hindering their contact with the alkaline solution (Figure 3c). Alkaline activation would ultimately continue slowly, for once the ash particles are covered by the reaction products, alkaline attack would take place via diffusion only. At the end of the process, a number of morphologies may co-exist in the same paste: Unreacted ash particles, particles under alkaline attack and reaction products (N–A–S–H gel or zeolites). This model is normally applied to the aforementioned ‘cenospheres’ (hollow particles or particles housing smaller spheres), which account for around 30% of the total. All the other particles, which are solid ‘plerospheres’ [51], exhibit greater or lesser reactivity depending on their size. The smallest particles (under one micrometre, approximately 10% of the total) dissolve rapidly in a highly alkaline medium. Despite these rather low percentages, the speedy setting and high early age strength attained with alkaline activation can be largely explained by the intense reactivity of cenospheres and small plerospheres.

Figure 3.

Conceptual model for AAFA cement hydration. (a) Starting material; (b) initial alkaline attack on the ashes and early N–A–S–H gel formation; (c) gel polymerisation and positioning on the inner and outer surfaces of the exposed fly ash; and (d) mature and heterogeneous AAFA cement paste microstructure (adapted from Fernández and Palomo [7]).

Glukhovsky [52] was the first to propose a general nano-scale mechanism for alkali activation reactions in aluminosilicate materials. His model is based essentially on dissolution-precipitation. The process begins when a series of silica and alumina monomers are released into the medium as a result of the rupture of Si–O–Si and Si–O–Al bonds attendant upon the dissolution of a source of aluminosilicate. The silica monomers inter-react to form dimers, which then react with other silica or alumina monomers to form trimers, and so on. As polymerization advances, a gel consisting in a complex aluminosilicate grid precipitates. The alkaline ion compensates the charge deficit stemming from the replacement of Si4+ with Al3+. In the very short term (minutes to hours), the gel formed has a fairly high Al content as a result of the high Al3+ ion concentration in the alkaline medium: reactive aluminum dissolves more quickly than reactive silicon because Al–O bonds are inherently weaker than Si–O bonds. As the reaction progresses, more Si–O groups dissolve, raising the silicon concentration in the reaction medium and enhancing its uptake in the gel. The N–A–S–H gel formed in hardened pastes is XRD amorphous and has been labeled as a zeolite precursor [7].

The structure of the N–A–S–H gel differs substantially from the C–S–H gel formed in OPC hydration. These N–A–S–H gels are characterized by a three-dimensional structure in which the Si is found in a variety of environments, with a predominance of Q4(3Al) and Q4(2Al) units. The silicate and aluminate groups are tetrahedrally coordinated and joined by oxygen bonds. The negative charge on tetrahedrally coordinated Al is offset by the presence of the alkaline cation provided by the activator used (typically Na+).

3. Hybrid Alkaline Cement Hydration

In recent studies, the authors have explored the potential for combining OPC and AAFA systems to form what might be called ‘hybrid alkaline cements’. In these systems, the starting solid comprises small percentages (20 wt % to 30 wt %) of OPC or OPC clinker and large proportions (70 wt % to 80 wt %) of fly ash. They also contain a separate source of alkali. The most significant differences between these systems and pozzolanic cements lie in the proportion of OPC, the prevalent solid component in the latter, and the alkaline addition in the former. The pozzolanic reaction involving fly ash particles is known to be slow in pozzolanic cements, while fly ash reactivity kinetics are much faster in hybrid alkaline cements (particularly as regards the cenospheres and the smallest plerospheres).

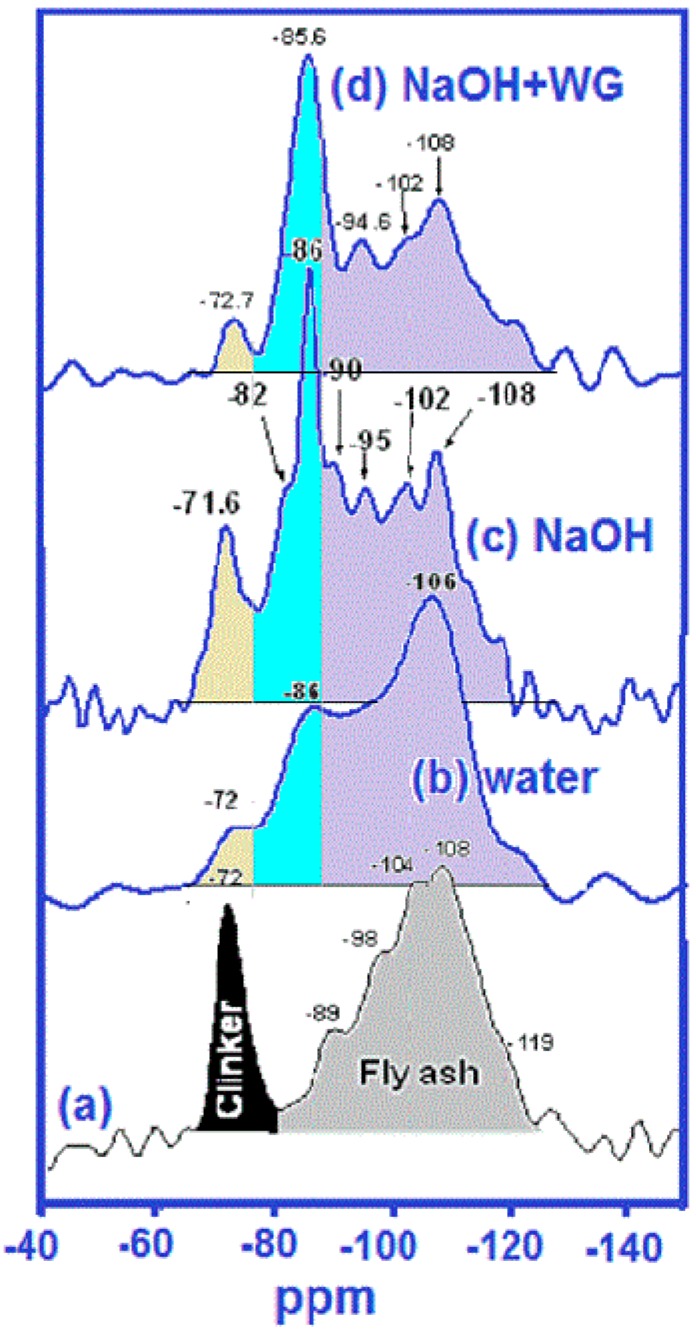

In 2007, Palomo et al. [18] showed that according to the 29Si NMR findings for alkaline fly ash cement pastes, hydration in an NaOH medium significantly inhibited the calcium silicate clinker phase hydration and hence portlandite formation in the first 28 days. That notwithstanding, their 28-day compressive strength was similar to blended cement strength. FTIR spectra for the NaOH-hydrated paste exhibited several new absorption bands in the 960 cm−1 to 1050 cm−1 region, attributed to a combination of N–A–S–H– and C–S–H gels. That was supported by a predominant, clearly defined peak at −86 ppm on the 29Si NMR spectra for NaOH-activated hybrid cements (see Figure 4). Signals in that region may be indicative of Q2(0Al) environments typical of C–S–H gel [47,53,54] as well as Q3(3Al) and Q4(4Al) environments typical of N–A–S–H gels [32,55]. The intensification of the −86 ppm signal in NaOH-hydrated pastes was attributed to the additional Q3 or Q4 environments, or both, induced by the alkaline activation of fly ash particles.

Figure 4.

29Si MAS NMR spectra: (a) initial raw mix (30% clinker + 70% fly ash); (b) 28-day water-hydrated material; (c) 28-day NaOH-hydrated material; (d) 28-day NaOH + WG (waterglass)-hydrated material (adapted from Palomo et al. [18]).

The co-existence of these gels must be borne in mind when studying hybrid alkaline cements. Both N–A–S–H– and C–S–H gels, whose morphologies differ, have been observed in alkali-activated metakaolin/slag mixes [56]. The Ca/Si ratio in the C–S–H regions was around 1.0, a value significantly lower than found in the C–S–H gels forming in OPC hydration. In a later study on metakaolin/ground granulated blast furnace slag (MK/GGBFS), the aforementioned authors concluded that C–S–H gel stability declined when the activator was overly alkaline (>7.5 M NaOH). As a result, larger amounts of the Ca-containing component (GGBFS) were needed for the C–S–H regions to be detected [57]. Those findings were generally consistent with the conclusions of an earlier study on MK and Ca(OH)2 mixes by Alonso et al., in which C–S–H hydration was favored to some extent in a 5 M NaOH, but not in a 12 M NaOH medium [58,59].

Studies using synthetic gel phases have provided much valuable information [60,61,62]. Garcia-Lodeiro et al. [60] showed that the Ca/Si ratio in C–S–H gels declined in high alkaline media. Those authors also observed that when C–S–H gel was exposed to both an alkali and soluble Al, it evolved into a more highly polymerized C–A–S–H gel [62]. In studies on mixes of synthetic C–S–H and N–A–S–H gels, the same group reported that at pH > 12 the system ultimately tended toward the most stable product, C–A–S–H gel [63]. That tendency was recently confirmed in actual hybrid alkaline fly ash cements hydrated for up to one year [20].

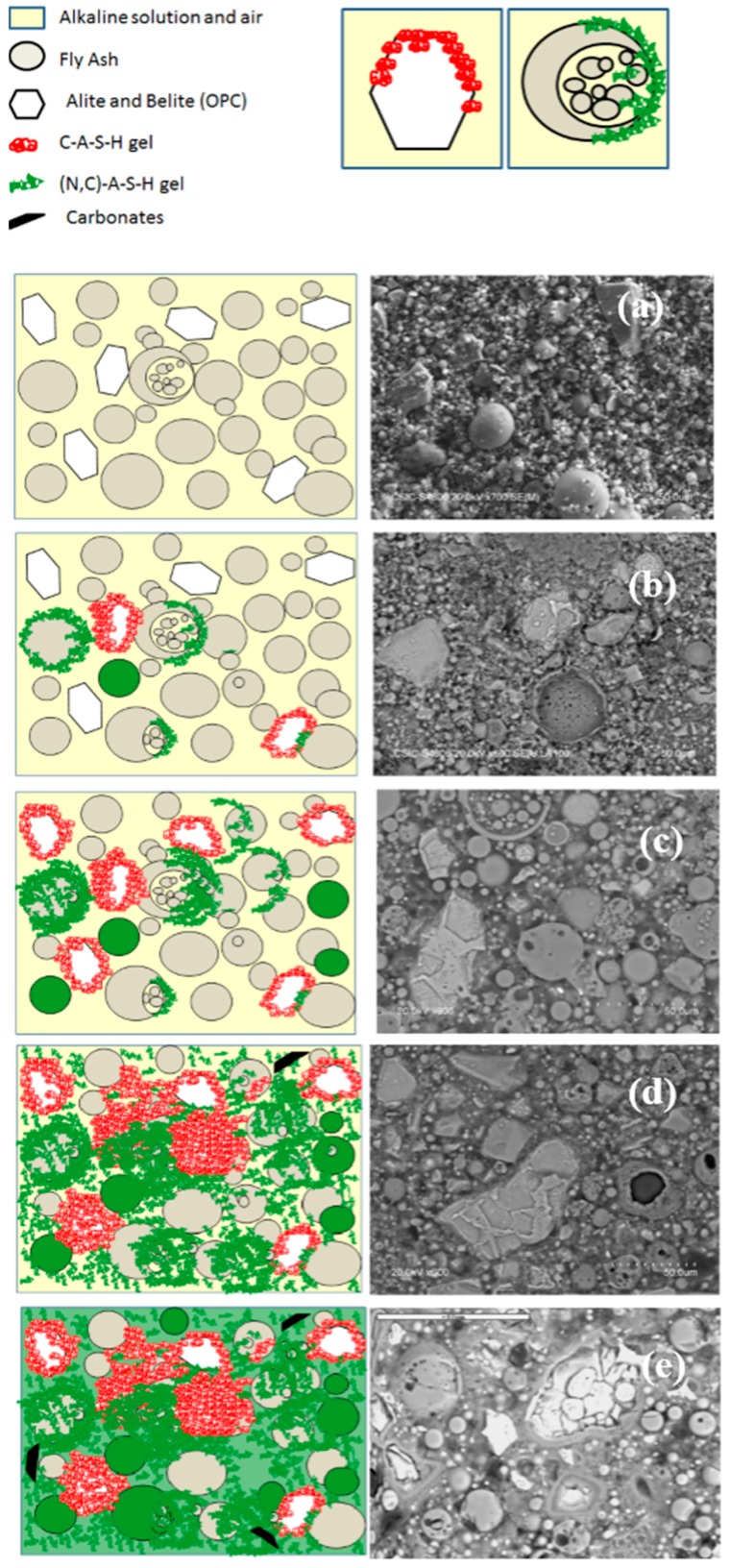

The BSEM (Backscattering electron microscopy) images of several hybrid alkaline cement samples [20,22,64,65,66,67] in Figure 5 illustrate this process. In the presence of the alkali (NaOH), substantial amounts of N–A–S–H gel, along with smaller quantities of C–S–H gel, would be expected to form at early ages. With the decline in liquid phase alkalinity as a result of both carbonation and the alkaline hydrolysis of vitreous fly ash phases, C–S–H gel stability rises. As significant amounts of soluble Al are released by the fly ash, however, C–A–S–H prevails over C–S–H formation. The generation of a pure N–A–S–H-like gel is unlikely in fly ash activation in hybrid alkaline cements, for the clinker present would release much more Ca than found in clinker-free pure AAFA cements. The outcome would be the partial replacement of the Na+ ions by Ca2+ ions as charge balancers, forming what might be labeled an (N,C)–A–S–H gel. Co-precipitation of the two types of gels has been confirmed in such systems [60,61,62,63].

Figure 5.

Changes in gel composition and microstructure of a hybrid alkaline cement with a very high fly ash content: (a) initial stage; (b) early age sample (min); (c) early age sample (h); (d) 7-day sample; (e) 28-day sample.

The use of activators with different degrees of alkalinity has a direct impact on reaction kinetics. The addition of highly alkaline activators favors ash [67] over clinker [68,69] dissolution, whereas in moderately alkaline media clinker hydration is favored and ash dissolution retarded. With time, however, the main reaction products detected are the ones most thermodynamically stable, irrespective of the type of activator used. In hybrid systems with high ash and low OPC contents the result is a mix of C–A–S–H + (N,C)–A–S–H gels [20,22,64,65,66].

Garcia-Lodeiro et al. [22] used isothermal conduction calorimetry in an initial study on early age (72 h) reaction kinetics in a 100% OPC systems, 100% FA systems and in hybrid cement consisting of 30% OPC and 70% fly ash. To that end, they used two activating solutions: Na2CO3 and a mix of NaOH + Na2SiO3. Further to the data from several analytical techniques (BSEM, FTIR, DTA/TG, etc.), they concluded several things; (i) the presence of high alkali content-induced delays in normal Portland cement hydration; (ii) the presence of alkalis induced some degree of fly ash dissolution, this process is very slow at ambient temperature; (iii) Alkaline activators must be present to stimulate hybrid cement hydration. The hydration kinetics were substantially modified by the type of alkaline activator, particularly with respect to the secondary phases generated. The main reaction products, however, a mix of C–A–S–H and (N,C)–A–S–H gels, were unaffected by the activator. While the type of alkaline activator impacted reaction kinetics and the formation of secondary reaction products (carbonates, AFm phases, etc.) significantly, it did not appear to have any material effect on the main cementitious gels formed ((N,C)–A–S–H/C–A–S–H).

The thermodynamically stable majority product was a mix of cementitious gels that formed irrespective of the activator used. The use of Na2CO3 as an alkaline activator retarded gel precipitation, favoring the formation of secondary phases such as gaylussite and AFm-type species. Nonetheless, a larger proportion of gel phase appeared to precipitate than in the system activated with the solution containing NaOH + WG. Similar conclusions have been obtained by different authors [64,65,70] for alkali activated hybrid cements, but using solid activators [71].

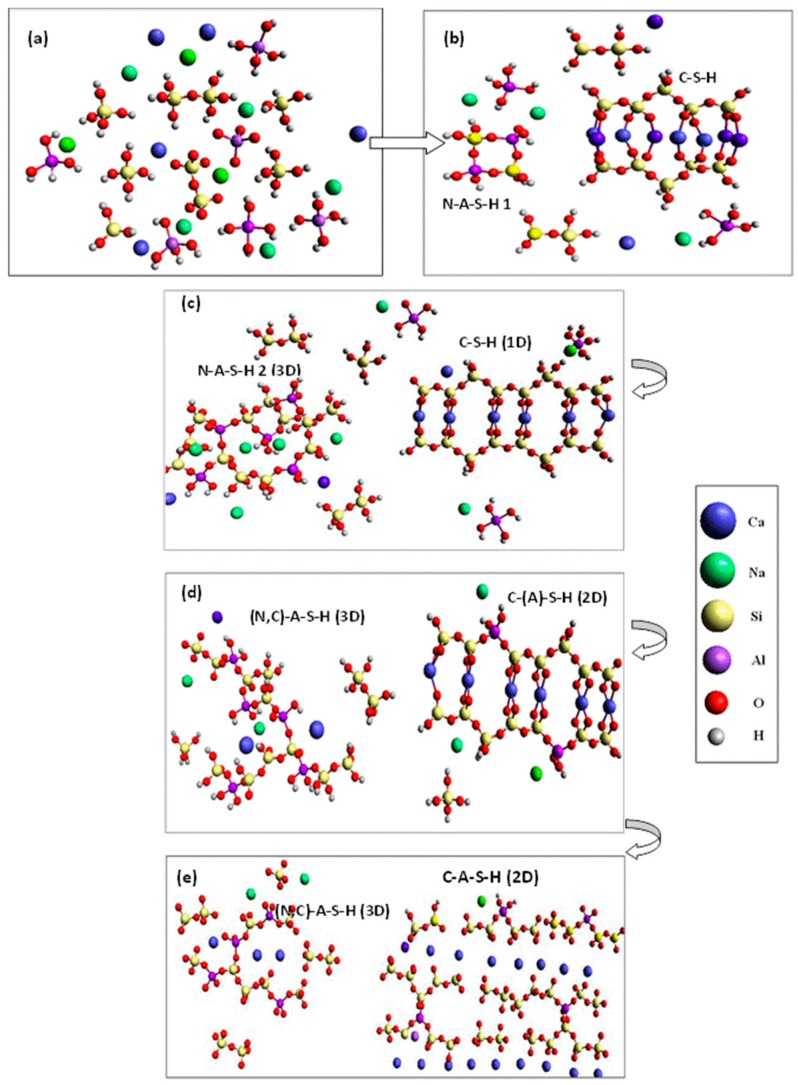

29Si and 27Al NMR, together with TEM/EDX studies of hybrid alkaline cements hydrated for up to 1 year have shown that both C–S–H and N–A–S–H gels evolve toward cross-linked C–A–S–H gels. The authors found that the lack of sufficient total Ca in the paste prevented conversion of all the N–A–S–H to C–A–S–H gel [20]. The expected nano-structural gel evolution (based on prior studies [20]) is illustrated in Figure 6. The process begins with the dissolution of the source of silicoaluminates and calcium silicates in the alkaline solution, with the concomitant release of a wide variety of dissolved species (Figure 6a). The medium becomes saturated with ions that are not uniformly distributed but rather exhibit local concentrations of the various species, depending on the nature of the nearest particle [20].

Figure 6.

Nano-structural mechanism for gel formation in hybrid alkaline cements; (a) dissolution of ionic species from the source of alumino-and calcium silicates; (b) precipitation of aluminum-high (type I) N–A–S–H gels and C–S–H gels; (c) silica uptake by both gels with an increase in C–S–H gel mean chain length and the generation of silica-high type 2 N–A–S–H gels; (d) diffusion of aluminum and calcium in the matrix and their uptake, respectively, in C–S–H and N–A–S–H gels to form (N,C)–A–S–H gels; (e) distortion of the (N,C)–A–S–H gel due to the polarizing effect of calcium, leading to its rupture, while the C–A–S–H gel continues to take up aluminum species in bridging positions, favoring chain cross-linking and hence a more polymerized structure (hydrogen bonds omitted in this final stage).

When these local concentrations reach saturation, C–S–H and N–A–S–H gels precipitate simultaneously (competitive reactions), although which of the two precipitates more rapidly has yet to be determined (Figure 6b). As the reaction progresses, more Si–O groups dissolve out of the initial aluminosilicate (fly ash) and the calcium silicate in the cement, raising the silicon concentration in the reaction medium and with it silicon uptake in both gels (Figure 6c).

At the same time, the Ca2+ and Al3+ ions present in the aqueous solution begin to diffuse through the hardened cementitious matrix. A small number of Ca2+ ions (not taken up in the C–S–H gel) interact with the N–A–S–H gel to form an (N,C)–A–S–H gel. Given the similar ionic radius and electronegative potential in Na+ and Ca2+, calcium replaces the sodium ions via ion exchange reminiscent of the mechanisms observed in clay and zeolites [61,72], maintaining the three-dimensional structure of the (N,C)–A–S–H gel [63]. Similarly, the C–S–H gel forming from the silicates in cement takes aluminum into its composition (preferably) in bridge positions [48,73,74], yielding C–(A)–S–H → C–A–S–H gels as the aluminum content rises (Figure 6d).

Where a sufficient store of the element is available, calcium continues to diffuse through the pores of the matrix and interact with the (N,C)–A–S–H gel. The polarizing effect of the Ca2+ (to form Si–O–Ca bonds) distorts the Si–O–Al bonds, inducing stress and ultimately rupture. At present, two hypothesis can explain the ion exchange mechanisms between the different gels produced in these type of cementitious systems: (a) the replacement of one Al3+ and one Na+ by two Ca2+ and (b) the replacement of two ions of Na+ by one Ca2+. As the N–A–S–H gel releases aluminum, less polymerized structures (C–A–S–H gels) will be formed. At the same time, that C–A–S–H gel formed in previous stages will incorporate more silicon and aluminum ions in bridging positions [75] (Figure 6e). However, we also have to consider that alkalis released to the pore solution might react with unreacted fly ash, then forming more N–A–S–H gel; and this last one can interact with C–S–H gel. In summary, an import part of the original alkalis can recycle and play an important role in the subsequent alkaline activation reactions. However, with time, these alkalis will become a part of the structure of the reaction products. It means that with time (with the reaction progress), the alkaline concentration will decrease until the equilibrium stage in pore solution is achieved. This process can be very slow in comparison with the very fast initial gel formation reactions. Currently authors are studying these systems by using different techniques (NMR, Electron Microscopy and Pores Solution Analysis) in order to confirm our hypothesis at long term (we are working with samples older than three years).

With time and under equilibrium conditions (attainable after longer reaction times), a (N)–C–A–S–H gel prevails. This is consistent with the behavior observed by the same authors in synthetic samples.

In these complex cementitious blends, the products formed and their proportions depend on reaction conditions, including: the chemical composition, shape, mineralogy and particle size distribution of the prime materials (fly ash reactivity rises with its vitreous content [49] and with declining particle size [76]), as well as the alkalinity (pH) generated by the activator [20,22,50,64].

4. Effect of Alkaline Activator in Hybrid Alkaline Cement Hydration

Garcia-Lodeiro et al. [22], analyzing hybrid cements activated with solutions of different alkalinity, found that, while the type of alkaline activator impacted reaction kinetics and the formation of secondary reaction products (carbonates, AFm phases…) significantly, it did not appear to have any material effect on the main cementitious gels formed ((N,C)–A–S–H/C–A–S–H). The thermodynamically stable majority product was a mix of cementitious gels that formed irrespective of the activator used. Nonetheless, the relative amount of each gel was observed to depend on the activator. Whilst the presence of strong alkalis favored the dissolution of fly ash and the precipitation of an (N,C)–A–S–H gel, the use of more moderately alkaline compounds favored the formation of C–A–S–H gels [22].

4.1. Intense Activation

The vast majority of hybrid cement hydration studies have been conducted with activators (primarily NaOH or mixes of NaOH + WG) that render the medium highly alkaline [20,22,26,50,64]. The high alkalinity of these solutions (with pH values of over 13) favors speedy ash dissolution. Moreover, at ambient temperature fly ash activation is accelerated by the presence of Portland cement clinker. The explanation for this beneficial effect lies in the heat released during cement hydration, which would favor the chemical reactions inducing ash dissolution, setting and hardening.

Highly alkaline activators, such as NaOH, prompt the hydrolysis of Si–O and Al–O bonds (the OH− ions act as catalysts), while the presence of soluble silica in the form of silicate ions enhances the polymerization rate of the ionic species present in the system [77,78]. Portland cement hydration, in turn, is affected by alkaline content (OH− concentration) and the presence of soluble silica [68,69,79].

A number of authors have analyzed early age (1 to 28 days) hybrid cement behavior (MK + Ca(OH)2, BFS + OPC, FA + OPC...) when the material is hydrated in the presence of different concentrations of strong activators. They consistently observed that high alkalinity favors the formation of N–A–S–H/(N,C)–A–S–H gels to the detriment of C–S–H gels and inhibits portlandite formation. C–S–H gel formation is favored by milder alkalinity [18,22,26,56,57,58,59].

That the type of activator and the alkalinity generated affect reaction kinetics and the nature of the gels initially formed has been ratified by studies on later age cements [20,22]. As hydration progresses, only the most thermodynamically stable products are identified. In systems containing large proportions of fly ash and low proportions of Portland clinker the outcome is a mix of C–A–S–H and (N,C)–A–S–H gels [20]. The proportion of each gel depends on the alkaline activator, however. When a mild activator is used, C–A–S–H gels are generated, with a minority presence of (C,N)–A–S–H gels.

Some of the arguments against the use of pure alkali–activated cements have centered on practical health and safety issues around the preparation and storage of highly alkaline solutions on construction factory sites. Given that alkali–activated cements are often touted as low-CO2 alternatives to PC, the associated CO2 footprint of the alkali activators has come under scrutiny [80]. The manufacture of NaOH and Na2SiO3 are fairly energy intensive processes. As a general rule of thumb, Duxson et al. [81] contended that the CO2 footprint of manufactured NaOH and Na2SiO3 stands at around 1 t CO2/t. Furthermore, in hybrid alkaline systems, highly alkaline activators appear to adversely affect C–S–H gel stability, the kinetics of clinker calcium silicate hydration or both. The result has been a growing interest in ‘just add water’ hybrid alkaline cement formulations, in which milder alkalis are used.

4.2. Mild Activation

The mildly alkaline activators commonly used to hydrate these hybrid cements include weak (sodium carbonate) and strong (sodium sulfate) acidic salts (see Table 1). Whilst NaOH solutions generate pH values ranging from 13 to 14, the media containing these milder activators exhibit values from 7 to 13.

Table 1.

Solubility (g of solute/100 g of water) and the Solubility Product Constants, Ksp of sodium and respective calcium salts and equilibrium calcium concentration (Equation (1)).

| A = Anión | Na Salts | Ca Salts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility g/100 g of Water Near to 25 °C | Ksp | Solubility g/100 g of Water Near to 25 °C | Ksp | (Ca2+) | |

| OH− | 100 | 110 | 0.160 | 5.5 × 10−6 | 11.1 |

| F− | 4.13 | – | 0.0016 | 5.3 × 10−9 | 1.1 |

| CO32− | 30.7 | 1.2 | 0.00066 | 2.8 × 10−9 | 0.053 |

| SO42− | 28.1 | 10.3 | 0.205 | 9.1 × 10−6 | 3.0 |

| PO42− | 14.5 | 2.24 | 0.00012 | 2.0 × 10−29 | 0.019 |

The effect of such soluble salts in raising the pH in the medium may possibly be attributed to their synergetic reaction with Ca(OH)2 [17,71,82], further to Equation (1):

| xCa(OH)2 + AxBy ↔ CaxB2(s) + 2xA(OH)(ac) | (1) |

where A is an alkaline cation, normally Na+ or K+, and B is the anion in the respective inorganic salt. Alkalinity is raised provided that the anion in the inorganic salt used forms an insoluble calcium compound (CaxB2), shifting equilibrium to the right in Equation (1).

The inorganic salts most widely used are listed in Table 1, along with their solubility products and the equilibrium calcium concentration. Lower calcium ion concentrations favor the precipitation of the inorganic calcium salt (CaxB2) generated, shifting equilibrium further to the right and rendering the activator more effective.

Another advantage of inorganic salts over highly alkaline activators (such as NaOH and WG) is that they have a lower impact on the hydration reaction of the clinker component in hybrid cements. In these systems, the clinker must first react with water to generate portlandite (pH ~ 12.5), which then reacts with the inorganic salt to generate the respective insoluble calcium salt and Na+(OH)−: i.e., alkalinity is generated in situ, as indicated in Equation (1) (pH > 13). For instance, depending on whether the activator is a carbonate or a sulfate, its reaction with Ca(OH)2 yields calcium carbonate or hydrated calcium sulfate (possibly gypsum), as shown in Equations (2) and (3), as well as Na+(OH)−(aq.), thereby raising medium alkalinity. In addition, the heat released during initial OPC hydration favors and expedites the dissolution of supplementary cementitious materials at high pH [17,71,82].

| Ca(OH)2 + Na2CO3 → CaCO3(s) + Na+OH−(aq.) | (2) |

| Ca(OH)2 + Na2SO4 → CaSO4·2H2O(s) + Na+OH−(aq.) | (3) |

Another intrinsic factor in the use of inorganic salts as mildly alkaline activators is the role of the constituent anion, particularly in connection with the secondary phases precipitating in these systems. The use of Na2CO3 as an activator, for instance, has been shown to favor the formation of gaylussite-like carbonates and calcite at very early reaction times (2 h) [22]. In that study, gaylussite was shown to be metastable during alkaline fly ash cement hydration. The authors hypothesized that the temporary uptake of Na in precipitating gaylussite delays the alkali activation of glassy fly ash phases.

When in a subsequent study Na2SO4 was used to activate cements, no ettringite was observed at any of the ages analyzed [64]. As the OPC used in these systems is normally blended with gypsum, it should theoretically have been able to form ettringite. Even in studies on pure OPC, however, the presence of alkalis has been shown to prevent ettringite formation [68,69], favoring instead other C3A hydration products such as phase U [83,84]. Monocarboaluminate (Ca4Al2CO3·11H2O) has been observed to be the prevalent in seven-day product. Systems with carbonate-containing activators exhibit the same behavior [22]: No ettringite is detected, although AFm (hemi and monocarboaluminate) forms in the seven-day materials.

Alahrache et al. [70] analyzed the effect of other, less conventional, mildly alkaline activators such as potassium citrate, sodium-potassium silicate and sodium oxalate on hydration kinetics and strength development in systems with high fly ash and low OPC contents. They found that the two latter activators were promising candidates for activation, for they shortened setting time and raised early age mechanical strength. The use of potassium citrate, however, retarded ash and clinker hydration, due either to the formation of complexes on the surfaces of these particles or to the hampering of C–A–S–H gel and AFm phase formation.

In a summary, the type of activator used has a direct impact on the secondary products precipitating and on reaction kinetics (essentially through the pH generated in the medium), accelerating or retarding the precipitation of the main reaction products. Irrespective of the type of activator used, however, the majority and most thermodynamically stable product in these non-equilibrium systems with limited amounts of calcium is a mix of cementitious gels. The proportion of each gel in the mix does, however, depend on the alkalinity generated in the medium.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents descriptive models for high fly ash-content hybrid alkaline cement hydration, a process that involves aspects typical of both PC and AAFA cement hydration. Hybrid binders arouse considerable interest given that their use would reduce CO2 emissions to much lower levels than traditional fly ash pozzolanic cements.

In hybrid cements activated directly with highly alkaline chemicals (NaOH), the prevalence of N–A–S–H gel interferes with the normal hydration of the calcium silicate phases present in the clinker, thereby hindering C–S–H gel formation. Both Al and Na have been shown to favor the conversion of C–S–H gel to C–A–S–H-like gel. Conversely, the presence of Ca attributable to clinker hydration has been shown to modify the structure of the N–A–S–H gel formed during fly ash hydration, with the appearance of an (N,C)–A–S–H structure.

In hybrid blends activated indirectly with moderately alkaline compounds (such as alkaline sulphates, carbonates or phosphates), both N–A–S–H and C–S–H gels are observed to form at early ages. The initial rapid hydration of the calcium silicate present in the clinker generates sufficient Ca and alkalinity to convert part of the soluble alkaline salts to NaOH, which then activates the glassy phases in the fly ash, inducing paste setting. The role of the anion in soluble alkaline salt activators should not be underestimated.

In hybrid alkaline cement systems, both N–A–S–H– and C–S–H gels have been proven to evolve toward C–A–S–H structures in older age specimens. Depending on the total amount of available Ca, a fraction of the N–A–S–H gel may remain in the system indefinitely.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a research grant (BIA2013-43293-R) awarded by the Spanish Ministry of the Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) to Ana Fernández. The participation of Post-graduate Studies Council post-doctoral grantees (2011) Shane Donatello and Ines Garcia-Lodeiro (JAE Doc 2011) was co-funded by MINECO and the European Social Fund.

Author Contributions

Ángel Palomo conceived and designed the experiments; Shane Donatello and Inés Garcia-Lodeiro performed the experiments; Inés Garcia-Lodeiro and Ana Fernández-Jiménez analyzed the data; all authors have contributed in the writing of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Sharp J.H., Gartner E.M., Macphee D.E. Novel cement systems (sustainability). Session 2 of the Fred Glasser Cement Science Symposium. Adv. Cem. Res. 2010;22:195–202. doi: 10.1680/adcr.2010.22.4.195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malhotra V.M., Mehta P.K. Advances in Concrete Technology. Taylor and Francis; Oxon, UK: 1996. Pozzolanic and Cementitious Materials. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massazza F. Pozzolanic Cements. Cem. Concr. Compos. 1993;15:185–214. doi: 10.1016/0958-9465(93)90023-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palomo A., Grutzeck M.W., Blanco M.T. Alkali-activated fly ashes. A cement for the future. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999;29:1323–1329. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8846(98)00243-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi C., Krivenko P.V., Roy D.M. Alkali-Activated Cements and Concretes. Taylor and Francis; New York, NY, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duxson P., Fernández-Jiménez A., Provis J.L., Lukey G.C., Palomo A., van Deventer J.S.J. Geopolymer technology: The current state of the art. J. Mater. Sci. 2007;42:2917–2933. doi: 10.1007/s10853-006-0637-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. Composition and microstructure of alkali activated fly ash binder: Effect of the activator. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005;35:1984–1992. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2005.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Criado M., Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. Alkali activation of fly ash: Effect of the SiO2/Na2O ratio. Part I: FTIR study. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2007;106:180–191. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2007.02.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duxson P., Mallicoat S.W., Lukey G.C., Kriven W.M., van Deventer J.S.J. The effect of alkali and Si/Al ratio on the development of mechanical properties of metakaolin-based geopolymers. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2007;292:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2006.05.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. Factors affecting early compressive strength of alkali activated fly ash (OPC-free) concrete. Mater. Constr. 2007;57:7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cement Composition. Europena Committee for Standardization; Brussels, Belgium: 2000. European standards EN 197-1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donatello S., Tyrer M., Cheeseman C.R. Comparison of test methods to assess pozzolanic activity. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010;32:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2009.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy M.J., Dhir R.K. Development of high volume fly ash cements for use in concrete construction. Fuel. 2005;84:1423–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2004.08.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Weerdt K., Kjellsen K.O., Sellevold E., Justnes H. Synergy between fly ash and limestone powder in ternary cements. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011;33:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2010.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bentz D.P., Sato T., de la Varga I., Jason Weiss W. Fine limestone additions to regulate setting in high volumen fly ash mixtures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012;34:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2011.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi C., Day R.L. Pozzolanic reaction in the presence of chemical activators Part II: Reaction products and mechanism. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000;30:607–613. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8846(00)00214-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y.M., Sun W., Yan H.D. Hydration of high-volume fly ash cement pastes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2000;22:445–452. doi: 10.1016/S0958-9465(00)00044-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palomo A., Fernández-Jiménez A., Kovalchuk G., Ordonez L.M., Naranjo M.C. OPC-fly ash cementitious systems: Study of gel binders produced during alkaline hydration. J. Mater. Sci. 2007;42:2958–2966. doi: 10.1007/s10853-006-0585-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi C., Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. New cements for 21st century: The Pursuit of an alternative to Portland Cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011;41:750–763. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2011.03.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Lodeiro I., Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. Variation in hybrid cements over time. Alkaline activation of fly ash-portland cement blends. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013;52:112–122. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernández-Jiménez A., Zibouche F., Boudissa N., García-Lodeiro I., Abadlia M.T., Palomo A. “Metakaolin-Slag-Clinker Blends.” The role of Na+ or K+ as alkaline activators of these ternary blends. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jace.12272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Lodeiro I., Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. Hydration kinetics in hybrid binders: Early reaction stages. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013;39:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2013.03.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gümeyisi E., Gesoglu M., Algin Z., Mermedas K. Optimization of concrete mixtures with hybrid belnds of metakaolin and fly ash using response Surface method. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014;60:707–715. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2014.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdonllahnejad Z., Hlvadek P., Miraldo S., Pacheco-Torgal F., Barroso de Aguiar J.L. Compressive Strenght, Microstructure and Hydration Products of Hybrid Alkaline Cements. Mater. Res. 2014;17:829–837. doi: 10.1590/S1516-14392014005000091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang X., Ge L., Kang G.-C., Mathews C. Laboratory investigation on the strength, stiffness, and thermal conductivity of fly ash and lime kiln dust stabilized clay subgrade materials. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2015;16:928–945. doi: 10.1080/14680629.2015.1028970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang X., Ge L., Liao W.C. Cement Hydration–Based Micromechanics Modelling of the Time-Dependent Small-Strain Stiffness of Fly Ash–Stabilized Soils. Int. J. Geomech. 2016;16:04015071. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)GM.1943-5622.0000552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor H.F.W. Cement Chemistry. 2nd ed. Thomas Telford; London, UK: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scrivener K.L., Nonat A. Hydration of cementitious materials, present and future. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011;41:651–665. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2011.03.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bullard J.W., Jennings H.M., Livingston R.A., Nonat A., Scherer G.W., Schweitzer J.S., Scrivener K.L., Thomas J.L. Mechanisms of cement hydration. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011;41:1208–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2010.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lothenbach B., Scrivener K., Hooton R.D. Supplementary cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011;41:1244–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2010.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deschner F., Winnefeld F., Lothenbach B., Seufert S., Schwesig P., Dittrich S., Goetz-Neunhoeffer F., Neubauer J. Hydration of Portland cement with high replacement by siliceous fly ash. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012;42:1389–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2012.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palomo A., Alonso S., Fernandez-Jimenez A., Sobrados I., Sanz J. Alkaline activation of fly ashes: NMR study of the reaction products. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2004;87:1141–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2004.01141.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernandez-Jimenez A., Palomo A., Criado M. Microstructure development of alkali-activated fly ash cement: A descriptive model. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005;35:1204–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Provis J.L. Geopolymers: Structure, Processing, Properties and Industrial Applications. CRC Press; Oxford, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collepardi M., Baldini G., Pauri M., Corradi M. Tricalcium aluminate hydration in the presence of lime, gypsum or sodium sulphate. Cem. Concr. Res. 1978;8:571–580. doi: 10.1016/0008-8846(78)90040-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meredith P., Donald A.M., Meller N., Hall C. Tricalcium aluminate hydration: Microstructural observations by in-situ electron microscopy. J. Mater. Sci. 2004;39:997–1005. doi: 10.1023/B:JMSC.0000012933.74548.36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bentur A. Effect of gypsum on the hydration and strength of C3S pastes. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1976;59:210–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1151-2916.1976.tb10935.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Odler I., Schuppstuhl J. Early hydration of tricalcium silicate III. Control of the induction period. Cem. Concr. Res. 1981;11:765–774. doi: 10.1016/0008-8846(81)90035-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quennoz A., Scrivener K.L. Interactions between alite and C3A-gypsum hydrations in model cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013;44:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2012.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juilliand P., Gallucci E., Flatt R., Scrivener K. Dissolution theory applied to the induction period in alite hydration. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010;40:831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2010.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scrivner K.L. Ph.D. Thesis. University of London; London, UK: 1984. The Development of the Microstructure during the Hydration of Portland Cement. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gartner E.M., Young J.F., Damidot D.A., Jawed I. Hydration of portland cement. In: Bensted J., Barnes P., editors. Structure and Performance of Cements. 2nd ed. Spon Press; New York, NY, USA: 2002. pp. 57–113. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garrault S., Nonat A. Experimental investigation of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) nucleation. J. Cryst. Growth. 1999;200:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0248(99)00051-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y., Odler I. On the origin of Portland cement setting. Cem. Concr. Res. 1992;22:1130–1140. doi: 10.1016/0008-8846(92)90042-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skalny J., Johansen V., Thaulow N., Palomo A. DEF: As a form of sulfate attack. Mater. Constr. 1996;46:5–29. doi: 10.3989/mc.1996.v46.i244.519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor H.F.W., Famy C., Scrivener K.L. Delayed ettringite formation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001;31:683–693. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00466-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cong X.D., Kirkpatrick R.J. 29NMR study of the structure of the calcium silicate hydrate. Adv. Cem. Bas. Mat. 1996;3:144–156. doi: 10.1016/S1065-7355(96)90046-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richardson I.G. Model Structures for C–(A)–S–H. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2014;70:903–923. doi: 10.1107/S2052520614021982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. Characterization of fly ashes. Potencial reactivity as alkaline cements. FUEL. 2003;82:2259–2265. doi: 10.1016/S0016-2361(03)00194-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garcia-Lodeiro I., Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. Crucial insights on the mix design of alkali-activated cement based systems. Handbook of Alkali-Activated Cements, Mortars and Concretes. [(accessed on October 2015)]. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1533/978-1-78242-288-4.1.49.

- 51.De Vargas A.S., Dal Molin D.C.C., Vilela A.C.F., Jalali S., Gomes J.P.C. Activacão Alcalina de Cinzas Volantes Utilizando Solucão Combinada de NaOH e Ca(OH)2. 61 Congresso Anual da ABM; Rio de Janeiro, Brasil: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glukhovsky V. Ancient, Modern and Future Concretes; Proceedings of the First International Conference Alkaline Cements and Concretes; Kiev, Ukraine. 11–14 October 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grutzeck M., Benesi A., Fanning B. Silicon 29 Magic Angle Spinning Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Study of Calcium Silicate Hydrates. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1989;72:665–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1151-2916.1989.tb06192.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia-Lodeiro I., Fernandez-Jimenez A., Sobrados I., Sanz J., Palomo A. C-S-H Gels: Interpretation of 29Si MAS-NMR Spectra. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2012;95:1440–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2012.05091.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Criado M., Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A., Sobrados I. Effect of the SiO2/Na2O ratio on the alkali-activation of fly ash. Part II: 29Si MAS-NMR survey. Micr. Mes. Mat. 2008;109:525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2007.05.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yip C.K., van Deventer J.S.J. Microanalysis of calcium silicate hydrate gel formed within a geopolymeric binder. J. Mater. Sci. 2003;38:3851–3860. doi: 10.1023/A:1025904905176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yip C.K., Lukey G.C., van Deventer J.S.J. The coexistence of geopolymeric gel and calcium silicate hydrate at the early stage of alkaline activation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005;35:1688–1697. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.10.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alonso S., Palomo A. Alkaline activation of metakaolin and calcium hydroxide mixtures: Influence of temperature, activator concentration and solids ratio. Mater. Lett. 2001;47:55–62. doi: 10.1016/S0167-577X(00)00212-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Granizo M.L., Alonso S., Blanco-Varela M.T., Palomo A. Alkaline activation of metakaolin: Effect of calcium hydroxide in the products of reaction. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2002;85:225–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1151-2916.2002.tb00070.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garcia-Lodeiro I., Macphee D.E., Palomo A., Fernández-Jiménez A. Effect of alkalis on fresh C–S–H gels: FTIR analysis. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009;39:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2009.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garcia-Lodeiro I., Fernandez-Jimenez A., Palomo A., Macphee D.E. Effect of calcium addtiton in N–A–S–H cementitious gels. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2010;93:1934–1940. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garcia-Lodeiro I., Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A., Macphee D.E. Effect on fresh C–S–H gels of the simultaneous addition of alkali and aluminium. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010;40:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2009.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garcia-Lodeiro I., Palomo A., Fernández-Jiménez A., Macphee D.E. Compatability studies between N–A–S–H and C–A–S–H gels. Study in the ternary diagram Na2O-CaO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011;41:923–931. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Donatello S., Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. Very high volumen fly ash cements: Early age hydration study using Na2SO4 as an activator. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2013;96:900–906. doi: 10.1111/jace.12178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Donatello S., Maltseva O., Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. The Early Age Hydration Reactions of a Hybrid Cement Containing a Very High Content of Coal Bottom Ash. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2014;97:929–937. doi: 10.1111/jace.12751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Donatello S., Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. Durability of very high volume fly ash cement pastes and mortars in aggressive solutions. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013;38:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2013.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shi C., Day R.L.D. Acceleration of the reactivity of Fly Ash by Chemical Activation. Cem. Concr. Res. 1995;25:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0008-8846(94)00107-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martinez-Ramirez S., Palomo A. Microstructure studies on Portland cement pastes obtained in highly alkaline enviroments. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001;31:1581–1585. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00603-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martinez-Ramirez S., Palomo A. OPC hydration with highly alkaline solutions. Ad. Cem. Res. 2001;13:123–129. doi: 10.1680/adcr.2001.13.3.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alahrache S., Winnefeld F., Champenois J.B., Hesselbarth F., Lothenbach B. Chemical activation of hybrid binders based on siliceous fly ash and Portland cement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016;66:10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2015.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fernández-Jiménez A., Sobrados I., Sanz J., Palomo A. Hybrid cements with very low OPC content Alkaline activation of metakaolin-slag-clinker blends; Proceedings of the 13th International Congress on the chemistry of Cement (XIII ICCC), “Cementing a Sustainable Future”; Madrid, Spain. 3–8 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Engelhardt G., Michell D. High-Resolution Solid-State RMN of Silicates and Zeolites. Wiley & Sons; New Delhi, India: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Richardson I.G., Brough A.R., Groves G.W., Dobson C.M. The characterization of hardened alkali-activated blast furnace slag pastes and the nature of the calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) phase. Cem. Concr. Res. 1994;24:813–829. doi: 10.1016/0008-8846(94)90002-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pardal X., Pochard I., Nonat A. Experimental study of Si-Al substitution in calcium-silicate-hydrate (C–S–H) prepared under equilibrium conditions. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009;39:637–664. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2009.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sun G.K., Young J.F., Kirkpatrick R.J. The role of Al in C-S-H: NMR, XRD, and compositional results for precipitated samples. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006;36:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2005.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bentz D.P., Hansen A.S., Guynn J.M. Optimization of cement and fly ash particle sizes to produce sustainable concretes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011;33:824–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2011.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Garcia-Lodeiro I., Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. Chemistry, Mix Designed and Manufacture of Alkali Activated Cement Based Concretes-Mixtures. Handbook of Alkali-Activated Cements, Mortars and Concretes. [(accessed on October 2015)]. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1533/978-1-78242-288-4.1.49.

- 78.Palomo A., Krivenko P., Garcia-Lodeiro I., Kavalerova E., Maltseva O., Fernandez-Jimenez A. A review on alkaline activation: New analytical perspectives. Mater. Constr. 2014;64 doi: 10.3989/mc.2014.00314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sant G., Kumar A., Patapy C., Le Saout G., Scrivener K. The influence of sodium and potassium hydroxide on volume changes in cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012;42:1447–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2012.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McLellan B.C., Williams R.P., Lay J., van Riessen A., Corder G.D. Costs and carbon emissions for geopolymer pastes in comparison to ordinary Portland cement. J. Clean. Prod. 2011;19:1080–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Duxson P., Provis J.L., Lukey G.C., van Deventer J.S.J. The role of inorganic polymer technology in the development of “green concrete”. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007;37:1590–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2007.08.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Justnes J.H., Østnor T.A. Designing Alternative Binders Utilizing Synergic Reactions; Proceedings of the NTCC2014: International Conference on Non-Traditional Cement and Concrete; Brno, Czech Republic. 16–19 June 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li G., Le Bescop P., Moranville M. The U phase formation in cement-based systems containing high amounts of Na2SO4. Cem. Concr. Res. 1996;26:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0008-8846(95)00189-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sanchez-Herrero M.J., Fernández-Jiménez A., Palomo A. Alkaline hydration of tricalcium aluminate. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2012;95:3317–3324. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2012.05348.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]