Abstract

Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26 utilizes γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-HCH) as a sole source of carbon and energy. In our previous study, we cloned and characterized genes that are involved in the conversion of γ-HCH to maleylacetate (MA) via chlorohydroquinone (CHQ) in UT26. In this study, we identified and characterized an MA reductase gene, designated linF, that is essential for the utilization of γ-HCH in UT26. A gene named linEb, whose deduced product showed significant identity to LinE (53%), was located close to linF. LinE is a novel type of ring cleavage dioxygenase that catalyzes the conversion of CHQ to MA. LinEb expressed in Escherichia coli transformed CHQ and 2,6-dichlorohydroquinone to MA and 2-chloromaleylacetate, respectively. Our previous and present results indicate that UT26 (i) has two gene clusters for degradation of chlorinated aromatic compounds via hydroquinone-type intermediates and (ii) uses at least parts of both clusters for γ-HCH utilization.

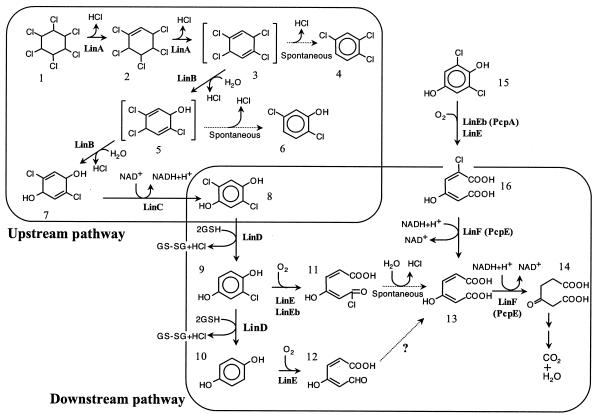

Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26 utilizes the halogenated organic insecticide γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-HCH; also called γ-BHC and lindane) as a sole source of carbon and energy under aerobic conditions (7). UT26 degrades γ-HCH through the pathway shown in Fig. 1 (25). γ-HCH is converted to 2,5-dichlorohydroquinone (2,5-DCHQ) by sequential reactions catalyzed by LinA (γ-HCH dehydrochlorinase) (8, 20, 26, 37), LinB (1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-1,4-cyclohexadiene chlorohydrolase) (21, 24), and LinC (2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-diol dehydrogenase) (22). 2,5-DCHQ is then dechlorinated to chlorohydroquinone (CHQ) by LinD (2,5-DCHQ dechlorinase) (17), and CHQ is further transformed to maleylacetate (MA) by LinE (CHQ 1,2-dioxygenase) (18). LinE is the first reported enzyme that prefers hydroquinone (HQ)-type compounds, i.e., aromatic compounds with two hydroxyl groups at the para position, as its substrate to catechol (18). The linA, linB, and linC genes for the upstream pathway are dispersed on the UT26 genome and are constitutively expressed (25). On the other hand, the linD and linE genes form an operon and their expression is induced by a LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR), LinR, in the presence of HQ-type compounds, such as CHQ, HQ, and 2,5-DCHQ (19).

FIG. 1.

Proposed pathways of γ-HCH and 2,6-DCHQ degradation by S. paucimobilis UT26. PcpA and PcpE are the enzymes involved in PCP degradation by S. chlorophenolicum ATCC 39723 (1). Compounds: 1, γ-HCH; 2, pentachlorocyclohexene; 3, 1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-1,4-cyclohexadiene; 4, 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene; 5, 2,4,5-trichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1-ol; 6, 2,5-dichlorophenol; 7, 2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-diol; 8, 2,5-DCHQ; 9, CHQ; 10, HQ; 11, acylchloride; 12, γ-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde; 13, MA; 14, β-ketoadipate; 15, 2,6-DCHQ; 16, 2-CMA. GSH, glutathione, (reduced form); GS-SG, glutathione (oxidized form).

By a series of reactions catalyzed by LinA to LinE, γ-HCH is converted to MA (Fig. 1). MA is known as one of the major intermediates in the degradation of aromatic compounds, and it is usually converted to β-ketoadipate by MA reductase. β-Ketoadipate is metabolized by the β-ketoadipate degradation pathway widely distributed in soil bacteria and fungi (5, 9, 13, 33, 34). In this study, we identified and characterized a gene, designated linF, encoding MA reductase, which was necessary for the assimilation of γ-HCH in UT26. We further characterized a gene encoding a LinE homologue that was located close to linF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli cells were grown at 37°C in Luria broth (LB) (15), and S. paucimobilis cells were grown at 30°C in 1/3 LB (3.3 g of Bacto Tryptone per liter, 1.7 g of yeast extract per liter, 5 g of sodium chloride per liter) or W minimal medium containing an appropriate carbon source (7). Ampicillin and kanamycin were used at a final concentration of 50 μg/ml, and tetracycline was used at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. paucimobilis | ||

| UT26 | HCH+a; Nalr | 7 |

| UT1023 | UT26 linF::TnMod-OKm; Kmr | This study |

| UT1023d | UT26 linF::TnMod-OKm; knockout mutant by use of p1023BamTc | This study |

| UT26orf3d | UT26 linEb disruptant via single crossover by use of pHSGorf3d; Kmr | This study |

| UT116 | UT26ΔlinRED | 23 |

| E. coli DH5α | F− φ80d lacZ ΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17 phoA supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | 29 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | pMB9 replicon; Apr | 38 |

| pUC1918 | pMB9 replicon; Apr | 32 |

| pHSG299 | pMB9 replicon; Kmr | 38 |

| pAQN | pMB9 replicon; lacIqaqnb Apr; tac promoter | 36 |

| pAQNM | pAQN derivative whose EcoRI-HindIII-flanked aqnb gene was replaced with the multiple cloning site from pHSG299 | This study |

| pTnMod-OKm | pMB1 replicon, Tn5 inverted repeat; Kmr | 2 |

| pKS13 | RK2 replicon; cos Mob+ Tcr | 11 |

| p1023Bam | TnMod-OKm-containing plasmid recovered by self-ligation of the BamHI-treated genome of UT1023; Kmr | This study |

| p1023Nco | TnMod-OKm-containing plasmid recovered by self-ligation of the NcoI-treated genome of UT1023; Kmr | This study |

| pKSF1 | pKS13 carrying linF, Pu promoterc | This study |

| pRE1 | pUC18 carrying linF | This study |

| pRE2 | pUC18 carrying linEb | This study |

| pMYLF1 | pAQNM carrying linF | This study |

| pRE3 | pAQNM carrying linEb | This study |

| pEX18Tc | TcrsacB oriT; suicide vector for gene replacement carrying the pUC18-derived multiple cloning sites | 6 |

| pTc1918 | pUC1918 carrying Tcr cassette amplified by PCR from pEX18Tc | This study |

| p1023BamTc | p1023Bam derivative with BamHI fragment containing Tcr gene from p1918Tc | This study |

| pHSGorf3d | pHSG299 derivative carrying the BamHI-PstI fragment of linEb that was amplified by PCR | This study |

HCH+, grown on γ-HCH.

aqn, aqualysin I gene of Thermus aquaticus.

Pu promoter, necessary for constitutive expression of the linA gene in S. paucimobilis UT26 (25).

DNA manipulation and DNA sequence analysis.

Established methods were used for the preparation of genomic and plasmid DNAs, digestion of DNA with restriction endonucleases, ligation, agarose gel electrophoresis, and transformation of E. coli cells (15). The nucleotide sequences were determined with an ABI PRISM 310 sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and an ABI Prism Big Dye Terminator kit (Applied Biosystems). Southern hybridization analysis was carried out by the conventional protocols (29) with a DIG system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Nucleotide sequences were analyzed with the Genetyx program, version 12 (SDC Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Homology searches were performed with BLAST programs available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

Transposon mutagenesis.

Random mutagenesis of S. paucimobilis UT26 was accomplished with pTnMod-OKm, which carries pMB1-based replication machinery in a Tn5-derived minitransposon (2). Transformation of UT26 cells by pTnMod-OKm was performed as described previously (12). Kmr transformants were streaked on W minimal medium agar containing 0.5 g of γ-HCH per liter, and mutants deficient in γ-HCH utilization were selected. The γ-HCH degradation activities of the mutants were also monitored by Shimadzu GC-17A gas chromatography (GC) with an electron capture detector (ECD) and an Rtx-1 capillary column (30 m by 0.25 mm by 0.25 μm; Restek, www.restekcorp.com) as described previously (21). The column temperature was increased from 100 to 260°C at a rate of 20°C/min, and the gas flow rate was 30 ml/min.

Characterization of transposon insertion sites.

Genomic DNA prepared from a mutant into which TnMod-OKm had been inserted was digested with BamHI or NcoI. The digested DNA was self-ligated, and the self-replicating Kmr plasmids were recovered by transformation of E. coli DH5α cells. The plasmids thus recovered were used to determine the sequences of flanking regions of the TnMod-OKm insertion sites with primers 5′-GCTGGCCTTTTGCTCAC-3′ and 5′-TTGAGACACAACGTGGC-3′, which anneal the regions close to both ends of TnMod-OKm.

Allelic-exchange mutagenesis.

A BamHI-flanked Tcr gene cassette derived from pEX18Tc (6) was inserted into the BamHI site of p1023Bam (Table 1). The resultant plasmid, p1023BamTc, was introduced into UT26 by electroporation, and Kmr but Tcs transformants were selected. The double-crossover-mediated homologous recombination of one of these transformants (UT1023d) was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. To disrupt linEb on the UT26 genome, we used PCR to amplify an internal fragment of linEb lacking both its 5′ and 3′ ends with primers orf3midFB1 (5′-CCGGATCCTGGAATGGTGGATCGGCC-3′) and orf3midRP1 (5′-GCCCTGCAGCGAGAAGTCGGTGAAGCCG-3′) and cloned it into Kmr-encoding vector pHSG299. The resultant plasmid, pHSGorf3d (Table 1), was introduced into UT26 to obtain Kmr transformants. Southern blot analysis indicated that one such mutant (UT26orf3d) was formed by homology-dependent single-crossover-mediated integration of the plasmid into linEb so that the two linEb-derived sequences on the genome were both truncated.

Construction of plasmids for analyses of the linF and linEb products.

The linF gene was amplified by PCR with the UT26 genome as the template and primers linFFB1 (5′-GCCGGATCCTCTGCCCCGGATATTC-3′) and linFRH1 (5′-GCCAAGCTTGGCTTATGCGGTGATCG-3′). The PCR-amplified fragment was inserted into pAQNM (Table 1) to obtain pMYLF1, in which the linF gene was under the control of the tac promoter. The primers used for amplification of linEb were orf3FB1 (5′-GCCGGATCCAAGAGGCGCGATTTTC-3′) and orf3RH1 (5′-GCCAAGCTTCCCAGGACTTCAAGGTTCC-3′). Insertion of the amplified fragment into pAQNM generated pRE3.

Assay of MA reductase activity.

E. coli DH5α(pMYLF1) cells were suspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 10% glycerol and disrupted by sonication. After centrifugation (17,000 × g) at 4°C for 10 min, the supernatant was used as a crude cell extract. MA reductase activity was measured spectrophotometrically by monitoring NADH oxidation at 340 nm (31). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount that consumes 1 μmol of NADH per min for MA reduction. MA was prepared on the day of its use by alkaline hydrolysis of cis-dienelactone (3).

GC-MS analysis.

E. coli cells expressing LinF and/or LinEb were suspended in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 10 μM substrates and then incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The mixtures were extracted with ethyl acetate after acidification by adding 10 μl of HCl and then analyzed by GC-mass spectrometry (MS) with a GP2010 spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and a DB-17 capillary column (30 m by 0.25 mm by 0.25 μm; J&W Scientific). The column temperature was increased from 100 to 260°C at a rate of 10°C/min and then held at 260°C. The carrier gas flow was 14.0 ml/min. To analyze trimethylsilylated samples, we increased the column temperature from 100 to 200°C at a rate of 40°C/min and then from 200 to 280°C at a rate of 15°C/min. The carrier gas flow was 23.7 ml/min.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence determined in this study has been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession number AB177985.

RESULTS

Isolation of a UT26 mutant deficient in γ-HCH utilization.

To analyze the γ-HCH degradation pathway of UT26 in greater detail, we carried out random transposon mutagenesis of UT26 with pTnMod-OKm and screened 1,600 Kmr transformants to find mutants able to grow on W minimal medium agar containing succinate but not on the same agar containing γ-HCH as the sole carbon source. One of these mutants, UT1023, had no detectable defects in the LinA-to-LinE activities assayed by GC with an ECD. A single copy of the TnMod-OKm insertion in the UT1023 genome was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (data not shown).

Identification of the linF gene involved in γ-HCH degradation.

The UT1023-derived DNA fragments containing the TnMod-OKm insertion site were recovered as plasmids by digestion of the genomic DNA with BamHI or NcoI, self-ligation, and transformation of E. coli. The plasmids obtained with BamHI and NcoI were named p1023Bam and p1023Nco, respectively. Sequencing analysis revealed that TnMod-OKm was inserted into a 1,056-bp open reading frame (ORF) encoding a protein homologous to MA reductases from Sphingobium chlorophenolicum ATCC 39723 (PcpE; 92% identity) and other bacterial strains (approximately 55% identity). Amino acid residues considered to be important for Fe(II) binding-type alcohol dehydrogenases (33) are conserved in the deduced amino acid sequence of the ORF (His237, His241, Gly244, Gly245, and His251), suggesting that this ORF encodes MA reductase. Since MA is produced from γ-HCH by a series of reactions catalyzed by LinA to LinE (Fig. 1), the product of this ORF was predicted to catalyze the next step. Therefore, we designated the ORF the linF gene. Southern blot analysis revealed that UT26 has one copy of linF (data not shown). To confirm the function of linF in UT26, we disrupted the wild-type linF gene by allelic-exchange mutagenesis as described in Materials and Methods. The resultant linF disruptant, UT1023d, lost the ability to grow on W minimal medium agar containing γ-HCH, and this growth defect was complemented by the introduction of pKSF1, in which linF is located downstream of the Pu promoter (25) so as to allow the constitutive expression of linF in UT26. These results clearly indicated that linF is directly involved in γ-HCH utilization by UT26.

Expression and characterization of the linF gene product.

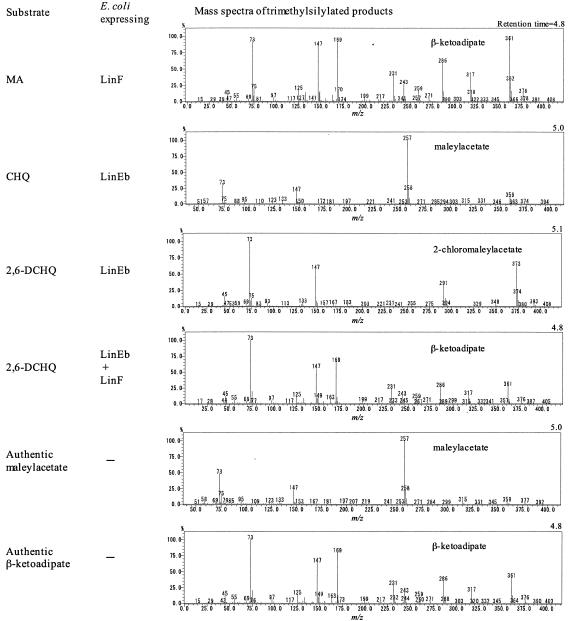

To express and characterize the linF gene product in E. coli, we constructed pMYLF1. E. coli DH5α(pMYLF1) cells were incubated with or without isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and their crude extracts were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. An approximately 38-kDa protein band was observed in the extract of the IPTG-treated cells. The molecular mass of this protein was close to that deduced from the nucleotide sequence of linF (36.3 kDa). The MA reductase activity of the cell extracts of DH5α(pMYLF1) were assayed spectrophotometrically by NADH consumption (31). The extract of the IPTG-treated cells showed a level of activity (4.9 × 102 U/mg of protein) 40-fold higher than that of IPTG-untreated cells (17 U/mg of protein). To identify a product of MA, we incubated an MA solution with E. coli cells expressing LinF and extracted the metabolites with ethyl acetate, trimethylsilylated them, and analyzed them by GC-MS. The mass spectrum of the peak that was specifically detected by incubation of MA with the LinF-expressing cells was equivalent to that of trimethylsilylated authentic β-ketoadipate (Fig. 2). These results demonstrated that the linF gene encodes MA reductase to produce β-ketoadipate from MA.

FIG. 2.

Mass spectra of the trimethylsilylated products of MA, CHQ, and 2,6-DCHQ incubated with E. coli-expressing LinF and/or LinEb. Mass spectra of the trimethylsilylated product of 2,6-DCHQ was identical with that of trimethylsilylated 2-CMA (27).

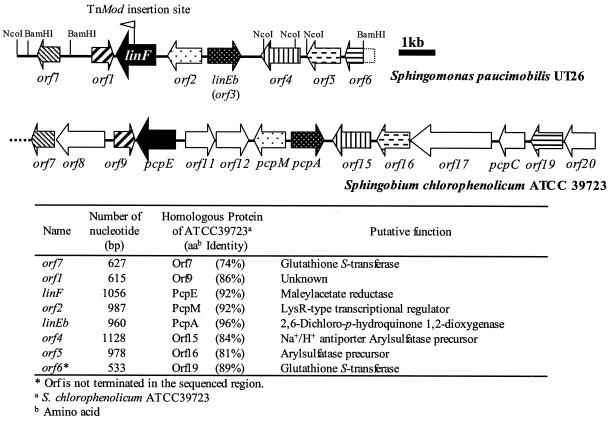

Organization of the linF-containing gene cluster.

We determined the nucleotide sequence of the 9,888-bp region containing the linF gene. This region contained, in addition to the linF gene, six complete ORFs and one partial ORF (Fig. 3). The putative gene products of all eight ORFs showed a relatively high degree of similarity to those of the corresponding ORFs in one of the gene clusters for pentachlorophenol (PCP) degradation by ATCC 39723 (Fig. 3). The enzymes for the PCP degradation pathway of ATCC 39723 are encoded by at least two gene clusters (1). One gene cluster contains the pcpB, pcpD, and pcpR genes encoding PCP hydrolase, tetrachlorobenzoquinone reductase, and a PCP-responsive LTTR, respectively. The other cluster contains the pcpE, pcpM, pcpA, and pcpC genes encoding MA reductase, LTTR, 2,6-dichloro-p-hydroquinone (2,6-DCHQ) 1,2-dioxygenase, and tetrachloro-p-hydroquinone reductive dehalogenase, respectively. The organization of the linF-containing region was similar to that of the latter gene cluster of ATCC 39723, although the latter one contains additional ORFs having no counterparts in the linF-containing region (Fig. 3). The upstream regions of linF (−343 to −328 from the start codon) and orf3 (−1471 to −134) had the consensus palindromic TN11A sequences for LTTR binding (30) (5′-ATTCGCCCCATGAAT-3′ and 5′-CTTCGCTTTTCGAAG-3′, respectively [the initial T and final A nucleotides are underlined]).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the linF-containing region in S. paucimobilis UT26 and the pcp gene cluster in S. chlorophenolicum ATCC 39723. Arrows indicate the sizes and orientations of the ORFs. Homologues are distinguished by filled patterns. A flag represents the TnMod-OKm insertion site. The leftward direction of the flag represents the orientation of the Kmr-encoding gene on TnMod-OKm.

Analyses of orf3 (linEb).

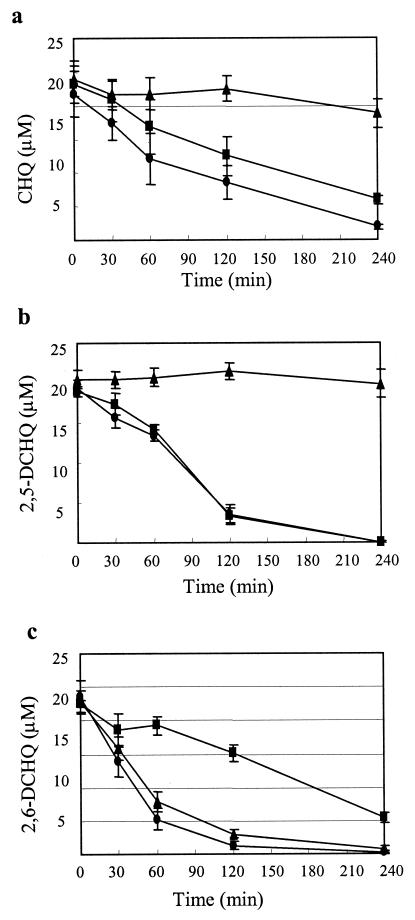

Because the putative orf3 gene product showed significant similarity to the novel type of ring cleavage dioxygenases, PcpA and LinE (96 and 53% amino acid identity, respectively), we renamed orf3 linEb. Substrates of PcpA and LinE are HQ-type compounds, i.e., aromatic compounds with two hydroxyl groups at the para position (18, 27, 40). This type of dioxygenase shows a low degree of similarity to meta cleavage dioxygenases, such as 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenases (BphC) (18). All of the residues proposed to be important for the Fe(II)-binding and enzyme activities of BphC (4, 35) are conserved in the deduced amino acid sequence of LinEb (His159, His227, and Glu276), suggesting that LinEb is functional. To characterize the function of LinEb, we expressed it in E. coli and analyzed the CHQ and 2,6-DCHQ transformation abilities by GC-MS. CHQ and 2,6-DCHQ were transformed by LinEb to MA and 2-chloromaleylacetate (2-CMA), respectively (Fig. 2). To characterize the function of linEb in UT26, we constructed a linEb disruptant of UT26 (UT26orf3d) as described in Materials and Methods. UT26orf3d was able to grow on W minimal medium agar containing γ-HCH, and it degraded 2,5-DCHQ and CHQ at a level comparable to that of UT26 (Fig. 4a and b). However, UT26orf3d degraded 2,6-DCHQ at a much lower rate than did UT26 (Fig. 4c). On the other hand, a spontaneous linRED deletion mutant, UT116, that is unable to utilize γ-HCH (23) showed an obvious defect in 2,5-DCHQ and CHQ degradation (Fig. 4a and b) but not in 2,6-DCHQ degradation (Fig. 4c). These results indicated that linEb has an important role in 2,6-DCHQ degradation but not in γ-HCH utilization by UT26. The 2,6-DCHQ degradation activity induced in UT26orf3d after 60 min of incubation (Fig. 4c) was considered to be derived from LinE because LinE showed degradation activity toward 2,6-DCHQ (K. Miyauchi et al., unpublished data).

FIG. 4.

Degradation of CHQ (a), 2,5-DCHQ (b), and 2,6-DCHQ (c) by S. paucimobilis UT26 (circles) and its mutants UTorf3d (squares) and UT116 (triangles). All of the cells were grown in 1/3 LB medium. The assay solution containing each substrate at 20 μM and 1 mM ascorbic acid in W medium was incubated with 10 mg of each cell type per ml at 30°C. The concentration of the remaining substrates was measured by GC with an ECD.

Substrate specificity of LinF.

Usually, MA reductases for degradation of chlorinated aromatic compounds convert not only MA but also CMA (1, 10, 39). The LinEb-expressing DH5α(pRE3) cells converted 2,6-DCHQ to 2-CMA as described above. When 2,6-DCHQ was incubated with LinEb-expressing DH5α(pRE3) and LinF-expressing DH5α(pMYLF1) cells, β-ketoadipate was detected as a product (Fig. 2). This result indicated that LinF converts 2-CMA to β-ketoadipate.

DISCUSSION

We have cloned genes for the conversion of γ-HCH to β-ketoadipate in UT26. β-Ketoadipate is usually metabolized by a chromosomally encoded convergent pathway for the degradation of aromatic compounds, and this pathway is widely distributed in soil bacteria and fungi (5). The presence of this pathway in UT26 is the most plausible, since the utilization of γ-HCH by UT26 requires LinF, which converts MA to β-ketoadipate. We believe that all of the specialized genes involved in γ-HCH degradation in UT26 have been identified. The three genes for the upstream pathway, linA, linB, and linC, exist separately from one another on the genome and are expressed constitutively (25). On the other hand, the genes for the downstream pathway, linD and linE, can be induced under the control of LinR. In this study, we demonstrated that the linF gene is a part of another gene cluster. The genes for γ-HCH degradation in UT26 are not sophisticated and look like a patchwork, suggesting that the pathway might have evolved recently.

It was suggested that the linF-containing gene cluster is functional for 2,6-DCHQ degradation by UT26. In our previous study, we demonstrated that the linRED operon for 2,5-DCHQ degradation is necessary for γ-HCH utilization by UT26. A spontaneous linRED deletion mutant, UT116, is unable to utilize γ-HCH (23), and it had defects in the degradation of 2,5-DCHQ and CHQ (Fig. 4a and b). These results suggested that UT26 uses LinE and LinEb for the utilization of γ-HCH (2,5-DCHQ) and 2,6-DCHQ, respectively. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that LinEb is also involved in γ-HCH utilization because (i) LinEb expressed in E. coli converted CHQ to MA (Fig. 2) and (ii) UT26orf3d degraded CHQ at a slightly lower rate than did UT26 (Fig. 4a). Both LinEb and LinE are dioxygenases that cleave aromatic rings with two hydroxyl groups at the para position. We designated the pathway that includes this type of ring cleavage step an HQ pathway (18, 19) although the number of reports describing this pathway is still limited. In this study, we demonstrated that UT26 has two gene clusters for the HQ pathway, one for 2,5-DCHQ degradation and the other for 2,6-DCHQ degradation. It is interesting that UT26 uses parts of the two HQ pathways for γ-HCH utilization. In other words, the downstream pathway for γ-HCH utilization by UT26 is formed by a combination of the two gene clusters.

Regulation of the expression of linF and linEb in UT26 is under investigation. Several LTTRs are involved in the degradation pathways for aromatic compounds such as catechol (28), naphthalene (41), and chlorocatechol (14, 16). The consensus sequence for the binding of LTTRs is known as a palindromic TN11A sequence (30). Such consensus sequences were found at the upstream regions of linF and linEb, as described above. A similar consensus sequence exists in the upstream region of the linE gene (19), and the expression of linE is upregulated by LinR, a member of the LTTR family, in the presence of 2,5-DCHQ, CHQ, or HQ in UT26 (19). It has also been reported that similar consensus sequences exist in the upstream regions of the pcpB, pcpA, and pcpE genes in ATCC 39723, and the expression of these genes is upregulated by an LTTR, PcpR, in the presence of PCP in ATCC 39723 (1). These results suggest that the expression of linF and linEb is also upregulated by a member of LTTRs in the presence of some chlorinated aromatic compounds.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (HC-04-2323-2), Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cai, M., and L. Xun. 2002. Organization and regulation of pentachlorophenol-degrading genes in Sphingobium chlorophenolicum ATCC 39723. J. Bacteriol. 184:4672-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dennis, J. J., and G. J. Zylstra. 1998. Plasposons: modular self-cloning minitransposon derivatives for rapid genetic analysis of gram-negative bacterial genomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2710-2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans, W. C., B. S. Smith, P. Moss, and H. N. Fernley. 1971. Bacterial metabolism of 4-chlorophenoxyacetate. Biochem. J. 122:509-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han, S., L. D. Eltis, K. N. Timmis, S. W. Muchmore, and J. T. Bolin. 1995. Crystal structure of the biphenyl-cleaving extradiol dioxygenase from a PCB-degrading pseudomonad. Science 270:976-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harwood, C. S., and R. E. Parales. 1996. The β-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:553-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoang, T. T., R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. J. Kutchma, and H. P. Schweizer. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imai, R., Y. Nagata, K. Senoo, H. Wada, M. Fukuda, M. Takagi, and K. Yano. 1989. Dehydrochlorination of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-BHC) by γ-BHC-assimilating Pseudomonas paucimobilis. Agric. Biol. Chem. 53:2015-2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imai, R., Y. Nagata, M. Fukuda, M. Takagi, and K. Yano. 1991. Molecular cloning of a Pseudomonas paucimobilis gene encoding a 17-kilodalton polypeptide that eliminates HCl molecules from gamma-hexachlorocyclohexane. J. Bacteriol. 173:6811-6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasberg, T., D. L. Daubaras, A. M. Chakrabarty, D. Kinzelt, and W. Reineke. 1995. Evidence that operons tcb, tfd, and clc encode maleylacetate reductase, the fourth enzyme of the modified ortho pathway. J. Bacteriol. 177:3885-3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaschabek, S. R., and W. Reineke. 1992. Maleylacetate reductase of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13: dechlorination of chloromaleylacetates, metabolites in the degradation of chloroaromatic compounds. Arch. Microbiol. 158:412-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimbara, K., T. Hashimoto, M. Fukuda, T. Koana, M. Takagi, M. Oishi, and K. Yano. 1989. Cloning and sequencing of two tandem genes involved in degradation of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl to benzoic acid in the polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading soil bacterium Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102. J. Bacteriol. 171:2740-2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komatsu, H., Y. Imura, A. Ohori, Y. Nagata, and M. Tsuda. 2003. Distribution and organization of auxotrophic genes on the multichromosomal genome of Burkholderia multivorans ATCC 17616. J. Bacteriol. 185:3333-3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laemmli, C. M., J. H. J. Leveau, A. J. B. Zehnder, and J. R. van der Meer. 2000. Characterization of a second tfd gene cluster for chlorophenol and chlorocatechol metabolism on plasmid pJP4 in Ralstonia eutropha JMP134(pJP4). J. Bacteriol. 182:4165-4172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leveau, J. H., and J. R. van der Meer. 1996. The tfdR gene product can successfully take over the role of the insertion element-inactivated TfdT protein as a transcriptional activator of the tfdCDEF gene cluster, which encodes chlorocatechol degradation in Ralstonia eutropha JMP134(pJP4). J. Bacteriol. 178:6824-6832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 16.McFall, S. M., S. A. Chugani, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1998. Transcriptional activation of the catechol and chlorocatechol operons: variations on a theme. Gene 223:257-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyauchi, K., S. K. Suh, Y. Nagata, and M. Takagi. 1998. Cloning and sequencing of a 2,5-dichlorohydroquinone reductive dehalogenase gene whose product is involved in degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane by Sphingomonas paucimobilis. J. Bacteriol. 180:1354-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyauchi, K., Y. Adachi, Y. Nagata, and M. Takagi. 1999. Cloning and sequencing of a novel meta cleavage dioxygenase gene whose product is involved in degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in Sphingomonas paucimobilis. J. Bacteriol. 181:6712-6719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyauchi, K., H. S. Lee, M. Fukuda, M. Takagi, and Y. Nagata. 2002. Cloning and characterization of linR, involved in regulation of the downstream pathway for γ-hexachlorocyclohexane degradation in Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1803-1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagata, Y., T. Hatta, R. Imai, K. Kimbara, M. Fukuda, K. Yano, and M. Takagi. 1993. Purification and characterization of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-HCH) dehydrochlorinase (LinA) from Pseudomonas paucimobilis. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 57:1582-1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagata, Y., T. Nariya, R. Ohtomo, M. Fukuda, K. Yano, and M. Takagi. 1993. Cloning and sequencing of a dehalogenase gene encoding an enzyme with hydrolase activity involved in the degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in Pseudomonas paucimobilis. J. Bacteriol. 175:6403-6410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagata, Y., R. Ohtomo, K. Miyauchi, M. Fukuda, K. Yano, and M. Takagi. 1994. Cloning and sequencing of a 2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-diol dehydrogenase gene involved in the degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in Pseudomonas paucimobilis. J. Bacteriol. 176:3117-3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagata, Y., K. Miyauchi, S.-K. Suh, A. Futamura, and M. Takagi. 1996. Isolation and characterization of Tn5-induced mutants of Sphingomonas paucimobilis defective in 2,5-dichlorohydroquinone degradation. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 60:689-691. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagata, Y., K. Miyauchi, J. Damborsky, K. Manova, A. Ansorgova, and M. Takagi. 1997. Purification and characterization of a haloalkane dehalogenase of a new substrate class from a gamma-hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading bacterium, Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3707-3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagata, Y., K. Miyauchi, and M. Takagi. 1999. Complete analysis of genes and enzymes for γ-hexachlorocyclohexane degradation in Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 23:380-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagata, Y., K. Mori, M. Takagi, A. G. Murzin, and J. Damborsky. 2001. Identification of protein fold and catalytic residues of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane dehydrochlorinase LinA. Proteins 45:471-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohtsubo, Y., K. Miyauchi, K. Kanda, T. Hatta, H. Kiyohara, T. Senda, Y. Nagata, Y. Mitsui, and M. Takagi. 1999. PcpA, which is involved in the degradation of pentachlorophenol in Sphingomonas chlorophenolica ATCC 39723, is a novel type of ring cleavage dioxygenase. FEBS Lett. 459:395-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothmel, R. K., T. L. Aldrich, J. E. Houghton, W. M. Coco, L. N. Ornston, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1990. Nucleotide sequencing and characterization of Pseudomonas putida catR: a positive regulator of the catBC operon is a member of the LysR family. J. Bacteriol. 172:922-931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 30.Schell, M. A. 1993. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:597-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlomann, M., E. Schmidt, and H. J. Knackmuss. 1990. Different types of dienelactone hydrolase in 4-fluorobenzoate-utilizing bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:5112-5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schweizer, H. D. 1993. Small broad-host-range gentamycin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. BioTechniques 15:831-834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seibert, V., E. M. Kourbatova, L. A. Golovleva, and M. Schlomann. 1998. Characterization of the maleylacetate reductase MacA of Rhodococcus opacus 1CP and evidence for the presence of an isofunctional enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 180:3503-3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seibert, V., M. Thiel, I. S. Hinner, and M. Schlomann. 2004. Characterization of a gene cluster encoding the maleylacetate reductase from Ralstonia eutropha 335T, an enzyme recruited for growth with 4-fluorobenzoate. Microbiology 150:463-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senda, T., K. Sugiyama, H. Narita, T. Yamamoto, K. Kimbara, M. Fukuda, M. Sato, K. Yano, and Y. Mitsui. 1996. Three-dimensional structures of free form and two substrate complexes of an extradiol ring cleavage type dioxygenase, the BphC enzyme from Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102. J. Mol. Biol. 255:735-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terada, I., S. T. Kwon, Y. Miyata, H. Matsuzawa, and T. Ohta. 1990. Unique precursor structure of an extracellular protease, aqualysin I, with NH2- and COOH-terminal pro-sequences and its processing in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 265:6576-6578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trantirek, L., K. Hynkova, Y. Nagata, A. Murzin, A. Ansorgova, V. Sklenar, and J. Damborsky. 2001. Reaction mechanism and stereochemistry of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane dehydrochlorinase LinA. J. Biol. Chem. 276:7734-7740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1987. Production of single-stranded plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 153:3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vollmer, M. D., K. Stadler-Fritzsche, and M. Schlomann. 1993. Conversion of 2-chloromaleylacetate in Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP 134. Arch. Microbiol. 159:182-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xun, L., J. Bohuslavek, and M. Cai. 1999. Characterization of 2,6-dichloro-p-hydroquinone 1,2-dioxygenase (PcpA) of Sphingomonas chlorophenolica ATCC 39723. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 266:322-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.You, I. S., D. Ghosal, and I. C. Gunsalus. 1988. Nucleotide sequence of plasmid NAH7 gene nahR and DNA binding of the nahR product. J. Bacteriol. 170:5409-5415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]