Abstract

Objective

To assess trends in cardiovascular (CV) mortality in patients with incident rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in 2000–07 vs. the previous decades compared to non-RA subjects.

Methods

The study population comprised Olmsted County, Minnesota residents with incident RA (age ≥18 years, 1987 ACR criteria met in 1980–2007) and non-RA subjects from the same underlying population with similar age, sex and calendar year of index. All subjects were followed until death, migration, or 12/31/2014. Follow-up was truncated for comparability. Aalen-Johansen methods were used to estimate CV mortality rates adjusting for competing risk of other causes. Cox proportional hazards models were used to compare CV mortality by decade.

Results

The study included 813 patients with RA and 813 non-RA subjects (mean age 55.9 years; 68% female for both groups). Patients with incident RA in 2000–07 had markedly lower 10-year overall CV mortality (2.7%; 95% CI 0.6%–4.9%) and coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality (1.1%; 95% CI 0.0–2.7%) than patients diagnosed in 1990–99 (7.1%; 95% CI 3.9–10.1% and 4.5%; 95% CI 1.9%–7.1%, respectively); HR for overall CV death: 0.43; 95% CI 0.19–0.94; CHD death: HR 0.21; 95% CI 0.05–0.95). This improvement in CV mortality persisted after accounting for CV risk factors. Ten-year overall CV mortality and CHD mortality in 2000–07 RA incidence cohort was similar to non-RA subjects (p=0.95 and p=0.79, respectively).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest significantly improved overall CV mortality, particularly CHD mortality, in patients with RA in recent years. Further studies are needed to examine the reasons for this improvement.

Key Indexing Terms: Rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, mortality

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is associated with increased cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality compared to the general population [1–5]. CV death has been recognized as a leading cause of premature mortality in RA, accounting for approximately 40–50% of all deaths, and is an important contributor to a mortality gap between RA and the general population [6–8]. Recent meta-analyses estimated a 50–60%-increase in the risk of CV death in patients with RA vs. the general population, with lack of evidence for decrease in CV mortality up to the mid-2000s [1, 9]. More recently published studies, including cohorts from the United Kingdom and Netherlands, suggest a potentially improving trend in CV mortality in patients with RA onset in 2000s [10, 11]. No excess relative CV mortality in patients with recent onset RA vs. general population was reported in a nationwide study from Finland [12]. However, large longitudinal studies comparing CV mortality trends in successive incidence cohorts of patients with RA are lacking, and trends in the relative excess CV mortality in RA vs. general population in the era of advanced therapeutics and intensive treatment strategies are not fully understood.

In this study, we aimed to assess CV mortality following RA onset in patients with incident RA in 2000–07 vs. the previous decades compared to non-RA subjects.

Materials and Methods

The study comprised a population-based inception cohort of Olmsted County, Minnesota residents aged ≥18 years (1987 American College of Rheumatology [ACR] criteria for RA met between 1/1/1980 and 12/31/2007). Patient ascertainment was performed using the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP), a population-based medical records-linkage system with access to the complete (in-patient and out-patient) medical records from all medical providers in the community [13–16]. For each patient, RA incidence date was defined as the earliest date of fulfillment of ≥4 1987 ACR criteria for RA. Comparison cohort included Olmsted County residents without RA chosen by random selection of a subject of similar age, sex and calendar year of index for each patient with RA. Each non-RA subject was assigned an index date corresponding to the incidence date of a patient with RA.

All study subjects were followed through medical record review until death, migration, or 12/31/2014. Follow-up of each cohort was truncated to make the length of follow-up comparable (i.e., the 1980–89 cohorts were truncated at 12/31/1994 and the 1990–1999 cohorts were truncated at 12/31/2004) A review of medical records was performed by trained nurse-abstractors to record the following CV risk factors: age, smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia. Hypertension was defined according to the criteria of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation and treatment of High Blood Pressure as ≥2 ambulatory blood pressure readings ≥140 mmHg systolic and/or ≥90 mmHg diastolic during a 1-year period, physician diagnosis or documented use of antihypertensives [17]. Dyslipidemia was defined based on Adult Treatment Panel-III guidelines [18] as total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL, low-density cholesterol ≥160 mg/dL, triglycerides ≥200 mg/dL or high-density cholesterol <40 mg/dL, physician diagnosis or documented use of lipid-lowering medications. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dl, physician diagnosis or documented use of insulin and/or oral hypoglycemic agents based on the diagnostic criteria adopted by the American Diabetes Association [19, 20]. Data on RA disease characteristics such as rheumatoid factor (RF) positivity, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), joint erosions/destructive changes on radiographs, severe extraarticular manifestations of RA (ExRA) including pericarditis, pleuritis, Felty’s syndrome, glomerulonephritis, cutaneous vasculitis, peripheral neuropathy, scleritis, episcleritis or retinal vasculitis [21] were collected for all patients. Information on antirheumatic medication use, including systemic glucocorticoids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (i.e. methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, other DMARDs), and biologics (tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, anakinra, abatacept, rituximab), NSAIDs and Cox-2 inhibitors were also gathered during the first year of RA incidence and ever during the follow-up.

Underlying causes of death were obtained from state and local death certificates and the National Death Index Plus, and grouped according to International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification (ICD-CM). ICD-9 version was used for deaths in 1980–1998; ICD-10 version was used thereafter. All causes of CV death were classified according to the American Heart Association (AHA) classification, with mutually exclusive sets of codes for coronary heart disease (CHD), non-CHD and non-cardiac circulatory causes [22]. The following ICD codes were used for CHD causes including myocardial infarction, revascularization procedures, CV death, angina: ICD-9 410–414, ICD-10:I20-I25; non-CHD diseases of the heart, including acute rheumatic fever, chronic rheumatic heart disease, hypertensive heart disease, pulmonary circulatory disease, other forms of heart disease: ICD-9: 390–398, 402, 404, 405, 415–429 and ICD-10: I00-I09, I11, I13, I26-I51; and non-cardiac circulatory causes, including cerebrovascular diseases; other hypertensive diseases (not included elsewhere); diseases of arteries, arterioles, and capillaries; diseases of veins, lymphatic vessels, and lymph nodes; other and unspecified disorders of the circulatory system: ICD-9: 401, 403, 430–459 and ICD-10: I10, I12, I15, I52-I99. This study was approved by institutional review boards (IRB) of Mayo Clinic (IRB #675-99) and Olmsted Medical Center (IRB #018-omc-06).

Statistical Methods

Comparisons of characteristics between cohorts were made with Chi-square and rank sum tests. The Aalen-Johansen method was used to estimate CV mortality rates adjusted for the competing risk of death from other causes [23]. Cox proportional hazards models, adjusting for age and sex and other characteristics, were used to compare CV mortality by decade. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R 3.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

The study included 813 patients with RA (a total of 10560 person-years of follow-up), of whom 315 developed incident RA during 2000–07, 296 during 1990–99 and 202 during 1980–89. Table 1 shows characteristics of patients with RA overall and by decade of incidence. Patients with RA onset in different decades were similar with respect to demographics and RF-positivity. The percentage of current smokers, the highest ESR in the first year of RA and the use of other DMARDs declined, while obesity, hyperlipidemia and the use of lipid-lowering medications, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, biologics, glucocorticoids, and NSAIDs increased in patients with more recent RA onset compared to earlier decades (Table 1). The percentage of patients with erosions in different decades of RA onset remained unchanged (p=0.26). The delay between first documentation of RA symptoms (i.e. swollen joints) and fulfillment of RA classification criteria has not changed over time (p=0.54), but the time from fulfillment of criteria to initiation of the first DMARD has decreased in recent years (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects

| RA cohort | Non-RA cohort | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence/index | Overall (n=813) | 1980–1989 (n=202) | 1990–1999 (n=296) | 2000–2007 (n=315) | Overall (n=813) | 1980–1989 (n=202) | 1990–1999 (n=296) | 2000–2007 (n=315) |

| Variables | ||||||||

| Age, years | 55.9 (15.7) | 57.4 (15.8) | 56.1 (15.8) | 54.6 (15.4) | 55.9 (15.7) | 57.4 (15.8) | 56.2 (15.8) | 54.6 (15.4) |

| Female sex | 556 (68%) | 138 (68%) | 195 (66%) | 223 (71%) | 556 (68%) | 138 (68%) | 195 (66%) | 223 (71%) |

| Cigarette smoking, at RA incidence | ||||||||

| - Never smoking | 364 (45%) | 79 (39%) | 123 (42%) | 162 (51%) | 435 (54%) | 101 (50%) | 165 (56%) | 169 (54%) |

| - Current smoking | 178 (22%) | 68 (34%) | 59 (20%) | 51 (16%) | 144 (18%) | 52 (26%) | 39 (13%) | 52 (17%) |

| - Former smoking | 271 (33%) | 55 (27%) | 114 (38%) | 102 (32%) | 234 (29%) | 49 (24%) | 92 (31%) | 93 (30%) |

| Obesity (BMI≥30 kg/m2), at RA incidence | 244 (30%) | 34 (17%) | 83 (28%) | 127 (40%) | 229 (28%) | 30 (14%) | 70 (24%) | 129 (41%) |

| CV risk factors, at incidence/index | ||||||||

| - Hypertension | 313 (38%) | 78 (39%) | 103 (35%) | 132 (42%) | 278 (34%) | 66 (33%) | 87 (29%) | 125 (40%) |

| - Anti-hypertensive medication use | 226 (28%) | 51 (25%) | 73 (25%) | 102 (32%) | 210 (26%) | 52 (26%) | 60 (20%) | 98 (31%) |

| - Diabetes mellitus | 80 (10%) | 22 (11%) | 23 (8%) | 35 (11%) | 68 (8%) | 15 (7%) | 18 (6%) | 35 (11%) |

| - Hyperlipidemia | 445 (55%) | 83 (41%) | 170 (57%) | 192 (61%) | 394 (48%) | 63 (31%) | 145 (49%) | 186 (59%) |

| - Lipid-lowering medication use | 114 (14%) | 1 (1%) | 35 (12%) | 78 (25%) | 107 (13%) | 4 (2%) | 29 (10%) | 74 (24%) |

| Coronary heart disease, at RA incidence/index | 89 (11%) | 23 (11%) | 35 (12%) | 31 (10%) | 90 (11%) | 18 (9%) | 36 (12%) | 36 (11%) |

| RA disease characteristics | ||||||||

| - RF positivity, at incidence/index | 537 (66%) | 132 (65%) | 198 (67%) | 207 (66%) | ||||

| - ExRA, during the first year | 32 (4%) | 7 (4%) | 12 (4%) | 13 (4%) | ||||

| - Highest ESR, during the 1st year of RA incidence, mm/hr, mean (SD) | 32.7 (25.7) | 38.9 (27.5) | 31.6 (25.1) | 29.9 (24.6) | ||||

| - Erosions/destructive changes, during the 1st year of RA incidence | 219 (27%) | 51 (25%) | 73 (25%) | 95 (30%) | ||||

| - Time from RA incidence date to first DMARD, months, median, 25th and 75th percentiles | 0.8 (0.0, 5.3) | 4.5 (0.8, 23.3) | 0.9 (0.1, 5.3) | 0.5 (0.0, 1.6) | ||||

| Antirheumatic medication use, during the 1st year of RA incidence | ||||||||

| - Methotrexate | 261 (32%) | 4 (2%) | 83 (28%) | 174 (55%) | ||||

| - Hydroxychloroquine | 362 (44%) | 50 (25%) | 133 (45%) | 179 (57%) | ||||

| - Other DMARDs | 127 (16%) | 56 (28%) | 44 (15%) | 27 (9%) | ||||

| - Biologics | 36 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 35 (11%) | ||||

| - Glucocorticoids | 445 (55%) | 53 (26%) | 177 (60%) | 215 (68%) | ||||

| - NSAIDs | 698 (86%) | 159 (79%) | 276 (93%) | 263 (84%) | 104 (13%) | 11 (5%) | 44 (15%) | 49 (16%) |

| - Cox-2 Inhibitors | 198 (24%) | 0 (0%) | 32 (11%) | 166 (53%) | 32 (4%) | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (1%) | 28 (9%) |

| Antirheumatic medication use, ever during follow-up | ||||||||

| - Methotrexate | 495 (61%) | 86 (43%) | 188 (64%) | 221 (70%) | ||||

| - Hydroxychloroquine | 496 (61%) | 97 (48%) | 188 (64%) | 211 (67%) | ||||

| - Other DMARDs | 291 (36%) | 104 (52%) | 113 (38%) | 74 (24%) | ||||

| - Biologics | 175 (22%) | 20 (10%) | 68 (23%) | 87 (28%) | ||||

| - Glucocorticoids | 650 (80%) | 137 (68%) | 254 (86%) | 259 (82%) | ||||

| - NSAIDs | 738 (91%) | 182 (90%) | 273 (96%) | 273 (87%) | 196 (24%) | 38 (19%) | 91 (31%) | 67 (21%) |

| - Cox-2 Inhibitors | 393 (48%) | 66 (33%) | 158 (53%) | 169 (54%) | 94 (12%) | 21 (10%) | 40 (14%) | 33 (10%) |

RA = Rheumatoid Arthritis; BMI = body mass index; CV = cardiovascular; RF = rheumatoid factor; ExRA = extraarticular manifestations of RA; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; DMARDs = disease modifying antirheumatic drugs, NSAIDs= non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SD = standard deviation

Values in the table are mean (±SD) for continuous characteristics and N (%) for discrete characteristics.

Significant differences between the RA and non-RA cohorts overall included smoking status (p=0.002) and hyperlipidemia (p=0.01). Significant differences between decades among the RA included smoking status, obesity, hyperlipidemia, use of lipid-lowering medications, ESR, time from RA incidence to initiation of the first DMARD, use in the first year and ever use of methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, other DMARDs, biologics, glucocorticoids, NSAIDs and Cox-2 inhibitors (all p<0.001). Significant differences between decades among the non-RA included smoking status (p=0.008), obesity (p<0.001), hyperlipidemia (p<0.001), use of lipid-lowering medications (p<0.001), hypertension (p=0.024), use of antihypertensives (p=0.009) and NSAIDs (p=0.003).

A comparison population comprised 813 non-RA subjects (a total of 11,468 person years of follow-up), including 315 non-RA subjects with index date in 2000–07, 296 with index date in 1990–99 and 202 subjects with index date in 1980–89 (Table 1). Apart from higher rates of smoking and hyperlipidemia in RA subjects, there were no statistically significant differences in demographics and CV risk factors between RA and non-RA subjects overall or by decade of incidence/index. The use of NSAIDs and Cox-2 inhibitors during the first year of RA onset and at any point during the followup was higher in patients with RA vs non-RA subjects.

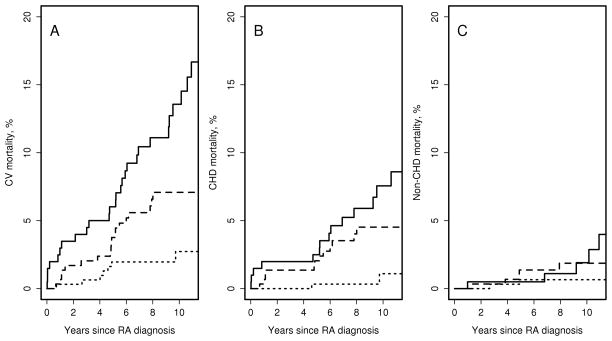

Figure 1 shows trends in CV mortality overall, CHD mortality and non-CHD mortality in patients with RA by decade of RA incidence. Mortality estimates for patients with RA by decade of incidence are shown in table 2. During the median follow-up of 9.0 years, 8 patients in the 2000–07 cohort died from CV disease, including 2 deaths from CHD (unadjusted 10-year overall CV mortality estimate 2.7%, 95%CI 0.6%–4.8%; CHD mortality 1.1%, 95%CI 0.0–2.7%), suggesting significant improvement in CV mortality after RA onset in 2000–2007 vs. those with RA onset in 1990–99. After adjustment for age and sex, results remained similar to unadjusted results (Table 2). Table 3 shows hazard ratios for CV mortality in patients with RA onset in different decades. Hazard ratio [HR] for overall CV death in 2000–07 cohort vs 1990–99 cohort was 0.42; 95%CI 0.18–0.95; CHD death: HR 0.17; 95%CI 0.04–0.75. Additional adjustment for smoking status, obesity, hypertension and hyperlipidemia did not alter these results (HR for CV death: 0.42; 95%CI 0.18–0.99; HR for CHD death: 0.14; 95%CI 0.03–0.67). In turn, patients in 1990–99 cohort showed a decrease in overall CV mortality and CHD mortality after RA onset vs. those in 1980–89 cohort (p=0.003 and p=0.09, respectively, Table 3). There was no evidence that time trends in overall CV mortality and CHD mortality after RA onset in any of the RA incidence cohorts differed by RF status (interaction p=0.30 and p=0.59, respectively) or by sex (interaction p=0.41 and p=0.77, respectively).

Figure 1.

Cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with incidence date in 1980–89 (solid line) 1990–99 (dashed line), 2000–07 (dotted line). Panel A: All-cause cardiovascular mortality; panel B: coronary heart disease mortality; panel C: non-coronary heart disease mortality

Table 2.

Cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and subjects without RA by decade of incidence/index

| Incidence/index year | 1980–1989 | 1990–1999 | 2000–2007 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| RA | Non-RA | RA | Non-RA | RA | Non-RA | |

| Number of patients | 202 | 202 | 296 | 296 | 315 | 315 |

| Median follow-up (IQR), years | 10.2 (7.8, 12.5) | 10.1 (7.4, 12.2) | 10.0 (7.4, 12.2) | 9.9 (7.0, 12.1) | 9.0 (7.3, 11.0) | 9.7 (7.9, 11.8) |

| CV deaths | 29 | 19 | 19 | 16 | 8 | 9 |

| - CHD deaths | 15 | 9 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 3 |

| - Non-CHD deaths | 5 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| Unadjusted 10-year mortality, % | ||||||

| - CV mortality | 13.6±2.6 | 10.2±2.4 | 7.1±1.6 | 5.7±1.4 | 2.7±1.1 | 3.1±1.1 |

| - CHD mortality | 7.6±2.1 | 4.4±1.3 | 4.5±1.3 | 2.4±0.9 | 1.1±0.8 | 1.2±0.7 |

| - non-CHD | 1.9±1.1 | 1.5±1.1 | 1.9±0.8 | 2.2±0.9 | 0.7±0.5 | 0.9±0.7 |

| Age and sex adjusted 10-year mortality, % | ||||||

| - CV mortality | 12.4±2.4 | 8.9±2.2 | 6.9±1.6 | 5.3±1.3 | 3.1±1.2 | 3.5±1.3 |

| - CHD mortality | 6.8±1.9 | 4.0±1.4 | 4.3±1.3 | 2.2±0.8 | 1.1±0.8 | 1.4±0.8 |

| - non-CHD | 1.8±1.0 | 1.2±0.9 | 2.0±0.9 | 2.1±0.9 | 0.9±0.6 | 1.0±0.7 |

Abbreviations: RA = rheumatoid arthritis; CV = cardiovascular; CHD = coronary heart disease; IQR= interquartile range

Table 3.

Relative declines in cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis by decade of incidence

| 1990–99 compared to 1980–89 | 2000–07 compared to 1990–99 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | |

| Age and sex adjusted mortality | ||||

| - CV mortality | 0.42 (0.23–0.75) | 0.003 | 0.42 (0.18–0.95) | 0.039 |

| - CHD mortality | 0.51 (0.24–1.10) | 0.086 | 0.17 (0.04–0.75) | 0.019 |

| - Non-CHD mortality | 0.40 (0.08–2.10) | 0.28 | 0.64 (0.18–2.23) | 0.48 |

| Age, sex and CV risk factor adjusted mortality | ||||

| - CV mortality | 0.33 (0.17–0.62) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.18–0.99) | 0.048 |

| - CHD mortality | 0.44 (0.19–1.03) | 0.058 | 0.14 (0.03–0.67) | 0.013 |

| - Non-CHD mortality | 0.51 (0.09–2.81) | 0.44 | 0.50 (0.13–1.97) | 0.32 |

CV=cardiovascular; CHD=coronary heart disease

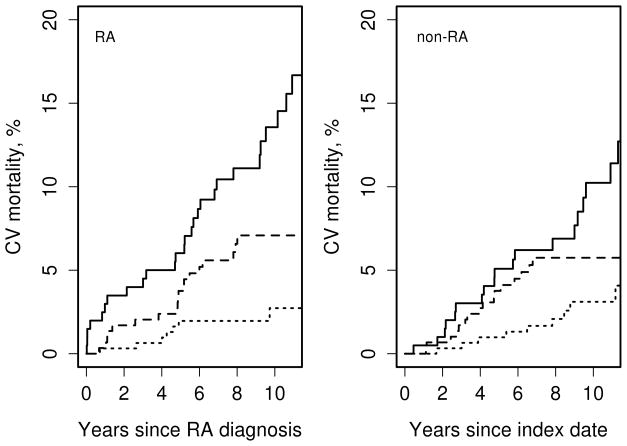

Figure 2 shows CV mortality in subjects with and without RA by decade of RA incidence/index, and Table 2 summarizes these data. There has been no statistically significant difference in overall CV mortality following RA incidence/index date in RA vs. non-RA subjects in 2000–07 cohort (p=0.95) and 1990–99 cohort (p=0.59); in 1980–89 cohort the difference in overall CV mortality in RA vs non-RA subjects was borderline significant (p=0.06). CHD mortality following RA incidence/index date was similar in RA and non-RA subjects in 2000–07 (p=0.79), 1990–99 (p=0.27) and 1980–89 cohort (p=0.13). After adjustment for age and sex, results remained similar to unadjusted results (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Cardiovascular mortality in subjects with and without rheumatoid arthritis (RA) by decade of RA incidence/index: 1980–89 (solid line) 1990–99 (dashed line), 2000–07 (dotted line)

There was no significant improvement in non-CHD deaths in patients with RA (p=0.22) (Figure 1, Table 2) or in the non-RA subjects (p=0.23, Table 2) with RA incidence/index date in different decades. Mortality from non-cardiac circulatory causes in RA improved in 1990–99 cohort compared to 1980–89 cohort (p=0.013), but was similar between 1990–99 and 2000–07 cohorts (p=0.43). Decline in mortality due to non-cardiac circulatory causes in non-RA subjects did not reach statistical significance (p=0.07). There was no evidence that the trend in mortality due to non-cardiac circulatory causes differed between those with and without RA (interaction p=0.20).

Discussion

The literature on increased CV morbidity and mortality in RA is mounting, but the recent trends in CV mortality following RA onset and the changes in relative mortality in RA vs. the general population are not well understood. This study is one of the first to show a marked decline in overall CV mortality and CHD mortality in patients who developed RA in the recent years vs. those with RA onset in the prior decades.

Only few studies thus far reported recent trends in CV mortality [10, 11, 24]. A declining trend in overall CV mortality has been suggested in patients with early inflammatory arthritis enrolled in the Norfolk Arthritis Register (NOAR) in 2000–04 vs. 1990–94 and censored after 7-year follow-up [10]. Mortality declined non-significantly from 8.78/1000 person-years in patients enrolled in 1990–94 to 7.07/1000 person-years in those enrolled in 2000–04 which was similar to the decline in CV mortality in the general population. Lower CV mortality rates in recent years were suggested in a prospective study from a Dutch population comparing CV mortality among patients with RA enrolled in 2009–2011 with CV mortality estimates reported in literature for various populations worldwide during the previous decades [11].

Extending these findings, our study has shown a statistically significant 58%-decline in CV mortality and a dramatic 83%-decline in CHD-related mortality in patients with RA onset in 2000–07 vs. 1990–99. Although the improvement was most apparent in the 2000–07 cohort, patients in 1990–99 cohort have also demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in CV mortality compared to the 1980–89 cohort. This improvement in CV mortality was observed in both men and women, regardless of RF-positivity, and persisted after accounting for age and traditional CV risk factors.

The reasons for this apparent improvement in CV mortality in RA are not clear. Biologics have been suggested as an important contributor to reduced CV event rates in prior studies and could be contributing to improved CV mortality in our 2000–07 cohort [25–27]. However, CV mortality improvement in 1990–99 cohort, i.e., before the widespread use of biologics, suggests alternative explanations for the improving mortality. These include increasing use of DMARDs as shown in our study, early initiation of antirheumatic treatments and associated improvement in inflammation control as suggested by a decline in highest ESR in the first year of RA onset in this study and decline in the rate of flares with concomitant increase in remission rates in RA over the past two decades as we recently showed in this cohort [28]. Delay in RA diagnosis has been associated with increased rate of CV events [29]. In this study, time from first documentation of swollen joints to fulfillment of RA classification criteria did not change over time, suggesting that other causes as presented in this discussion may have contributed to the changes in CV mortality in RA.

There is also growing evidence about the CV benefits of traditional DMARDs, primarily methotrexate [12, 30–35], with favorable implications for CV risk and life longevity with DMARD use and adherence to treat-to-target strategy [36, 37]. Increase in glucocorticoid use in 1990–99 and 2000–07 RA cohort vs. 1980–89 cohort in this study echoes dynamics in glucocorticoid use described in previous studies from our group [38] and others [39]. This increase in usage is thought to be due to changes in practice guidelines. The 2013 EULAR update on treatment recommendations of RA recommends addition of low-dose glucocorticoids as part of the initial treatment strategy for up to 6 months and tapering as soon as clinically feasible [40]. Positive dose-response association has been found between glucocorticoid use and CV mortality in RA [41]. However, our prior studies in this cohort showed that cumulative glucocorticoid dose, at least in the first year of RA diagnosis, has not changed significantly over time [36], suggesting no increase in adverse impact of glucocorticoid burden on CV mortality in more recent years vs. previously.

Our prior studies have suggested declining incidence of CV disease in patients with more recent onset RA, which may also contribute to lower CV mortality rates [42]. Increased awareness of CV disease in RA with advanced management strategies according to existing guidelines of CV management in RA [43, 44] could have improved CV mortality trends in RA. Improvement in CV health management in the population overall likely explains the improving trajectory of CV mortality in the general population, which may have provided a beneficial background for decreasing CV mortality in RA as well. In combination with improved inflammation control and CV disease management in RA, it could at least in part explain the somewhat more rapid improvement in CV mortality in RA than in the general population.

Indeed, our study suggests that CV mortality trends were largely similar in RA vs. non-RA cohort with RA incidence/index date in 1990–99 and 2000–07. However, subjects with RA incidence in 1980–89 had somewhat higher CV mortality rates than non-RA subjects. These findings echoed a study by Humphreys et al. in which CV mortality in patients with early inflammatory arthritis enrolled in the study after 1990 was similar to that in the general population [10]. Concordantly, Kerola et al. reported no excess CV mortality in patients with recent onset RA in 2000–07 vs the general population of Finland [12]. Likewise, Lacaille et al. have reported that 5-year CV mortality in patients with RA onset in 2001–2006 were similar to non-RA subjects [24]. Unlike improved CV mortality in incident RA cohorts, no improvement in CV mortality in patients with established RA was detected between 1997 and 2012 [45].

While there appears to be a general tendency towards improved CV outcomes in RA, some populations of patients with RA (including our RA cohort) appear to have had somewhat more pronounced improvements in CV mortality than others. Differences in data collection and case ascertainment as well as different healthcare practices in various populations worldwide may perhaps account for some of these differences. Ready access to healthcare among Olmsted County residents with only a few major healthcare providers and unified healthcare practices may have contributed to the somewhat more pronounced improvements in CV mortality in RA patients in our cohort. More studies are needed to understand whether there are other reasons for these heterogeneous trends in CV outcomes and to elucidate major determinants facilitating and precluding the improvement in CV morbidity and mortality in various populations of RA patients worldwide.

Our study has several important strengths. It is a large population-based study using a comprehensive medical record linkage system including all in-patient and out-patient care from all local providers. Standardized case ascertainment and inclusion of successive incidence cohorts strengthen the study. Our study also takes advantage of the long and complete follow-up of all subjects and the availability of a non-RA comparison cohort from the same underlying population. Use of uniform classification of CV deaths per AHA guidelines and standardized coding based on ICD-9 and ICD-10 also strengthens the study.

There are some potential limitations to the study. There is a potential for miscoding of the underlying causes of death. However, this would affect all subjects in the study and thus unlikely to significantly bias the comparisons. In addition, the coding of cause of death has changed from ICD-9 to ICD-10 in 1999 due to a change in the classification system. This change could influence comparisons of cause of death in the more recent cohorts (1990–99 cohort which is followed until 12/31/2004 and the 2000–07 cohort which is followed until 12/31/2014) vs. the earlier cohort. These system-based changes are impossible to account for in statistical analyses, however, the fact that the change affected both the 1990–99 and 2000–07 cohorts potentially minimized the shortcoming in respect to comparisons between the two cohorts.

The follow-up of the study was limited and the number of CV deaths, particularly deaths from CHD, was small which may limit statistical power. While we were able to show statistically significant differences in mortality despite the low numbers, examination of this issue in larger studies with longer followup and higher number of deaths is encouraged. Due to the availability of non-prescription over-the-counter medications, the data on NSAIDs/Cox-2 inhibitors provided in this study may underestimate the true use of these medications and should be interpreted with caution. Finally, during the period of investigation, the population of Olmsted County, Minnesota was predominantly white. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to nonwhite individuals.

In summary, our findings suggest a significant decline in overall CV mortality, particularly CHD mortality, among patients with incident RA in 2000–07 compared to patients with incident RA in the previous decades. This recent improvement in CV mortality in RA is perhaps somewhat more rapid than in the general population. While the reasons for the recent improvement in CV mortality in RA are uncertain, improving general population trends in CV health may be contributing, as may RA-disease specific factors including early effective antirheumatic treatment and increased awareness of the need for regular CV screening and management of patients with RA as a high CV risk group. Further studies are underway to understand the reasons for this recent improvement in CV mortality in RA, which may provide clues to improved CV management in both RA and the general population where benefits of inflammation control may also apply.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This work was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, NIAMS (R01 AR46849). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG034676. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Initial findings of this study were presented at the American College of Rheumatology meeting 2015 [46].

References

- 1.Avina-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, Etminan M, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1690–7. doi: 10.1002/art.24092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe F, Michaud K. The risk of myocardial infarction and pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic myocardial infarction predictors in rheumatoid arthritis: a cohort and nested case-control analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2612–21. doi: 10.1002/art.23811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis JM, 3rd, Roger VL, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. The presentation and outcome of heart failure in patients with rheumatoid arthritis differs from that in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2603–11. doi: 10.1002/art.23798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masuda H, Miyazaki T, Shimada K, Tamura N, Matsudaira R, Yoshihara T, et al. Disease duration and severity impacts on long-term cardiovascular events in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Cardiol. 2014;64:366–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparks JA, Chang SC, Liao KP, Lu B, Fine AR, Solomon DH, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and mortality among women during 36 years of prospective follow-up: Results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:753–62. doi: 10.1002/acr.22752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallberg-Jonsson S, Ohman ML, Dahlqvist SR. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis in Northern Sweden. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:445–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokka T, Abelson B, Pincus T. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: 2008 update. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:S35–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naz SM, Farragher TM, Bunn DK, Symmons DP, Bruce IN. The influence of age at symptom onset and length of followup on mortality in patients with recent-onset inflammatory polyarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:985–9. doi: 10.1002/art.23402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meune C, Touze E, Trinquart L, Allanore Y. Trends in cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis over 50 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1309–13. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphreys JH, Warner A, Chipping J, Marshall T, Lunt M, Symmons DP, et al. Mortality trends in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis over 20 years: results from the Norfolk Arthritis Register. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1296–1301. doi: 10.1002/acr.22296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meek IL, Vonkeman HE, van de Laar MA. Cardiovascular case fatality in rheumatoid arthritis is decreasing; first prospective analysis of a current low disease activity rheumatoid arthritis cohort and review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:142. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerola AM, Nieminen TVM, Virta LJ, Kautiainen H, Kerola T, Pohjolainen T, et al. No increased cardiovascular mortality among early rheumatoid arthritis patients: a nationwide register study in 2000–2008. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:391–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kremers HM, Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Savova G, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL. The Rochester Epidemiology Project: exploiting the capabilities for population-based research in rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:6–15. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE. Rochester Epidemiology Project: a unique resource for research in the rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2004;30:819–34. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955–2007. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1576–82. doi: 10.1002/art.27425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–52. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection E, Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in A. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Expert Committee on the D, Classification of Diabetes M. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(Suppl 1):S5–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Diabetes A. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(Suppl 1):S37, 42. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.suppl_1.s37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turesson C, Jacobsson L, Bergstrom U. Extra-articular rheumatoid arthritis: prevalence and mortality. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:668–74. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.7.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics. 2005 Update. Dallas, Tex: American Heart Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Statistics in Medicine. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacaille D, Avina-Zubieta JA, Sayre EC, Abrahamowicz M. Improvement in 5-year mortality in incident rheumatoid arthritis compared with the general population – closing the mortality gap. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Dec 28; doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209562. pii: annrheumdis-2016-209562. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnabe C, Martin BJ, Ghali WA. Systematic review and meta-analysis: anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy and cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:522–9. doi: 10.1002/acr.20371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenberg JD, Kremer JM, Curtis JR, Hochberg MC, Reed G, Tsao P, et al. Tumour necrosis factor antagonist use and associated risk reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:576–82. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.129916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ljung L, Askling J, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, Jacobsson L. The risk of acute coronary syndrome in rheumatoid arthritis in relation to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors and the risk in the general population: a national cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R127. doi: 10.1186/ar4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myasoedova E, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL, Davis JM, III, Crowson CS. Improved flare/remission pattern in rheumatoid arthritis over the recent decades [abstract] Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(Suppl 10) doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barra LJ, Pope JE, Hitchon C, Boire G, Schieir O, Lin D, et al. The effect of rheumatoid arthritis-associated autoantibodies on the incidence of cardiovascular events in a large inception cohort of early inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017 Jan 9; doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew474. pii: kew474. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Naranjo A, Sokka T, Descalzo MA, Calvo-Alen J, Horslev-Petersen K, Luukkainen RK, et al. Cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the QUEST-RA study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:R30. doi: 10.1186/ar2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suissa S, Bernatsky S, Hudson M. Antirheumatic drug use and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:531–6. doi: 10.1002/art.22094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hochberg MC, Johnston SS, John AK. The incidence and prevalence of extra-articular and systemic manifestations in a cohort of newly-diagnosed patients with rheumatoid arthritis between 1999 and 2006. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:469–80. doi: 10.1185/030079908x261177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prodanovich S, Ma F, Taylor JR, Pezon C, Fasihi T, Kirsner RS. Methotrexate reduces incidence of vascular diseases in veterans with psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:262–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernatsky S, Hudson M, Suissa S. Anti-rheumatic drug use and risk of hospitalization for congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:677–80. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi HK, Hernan MA, Seeger JD, Robins JM, Wolfe F. Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359:1173–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, Bykerk V, Dougados M, Emery P, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:3–15. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makol A, Davis JM, 3rd, Crowson CS, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL. Time trends in glucocorticoid use in rheumatoid arthritis: results from a population-based inception cohort, 1980–1994 versus 1995–2007. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1482–8. doi: 10.1002/acr.22365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedersen AB, Mor A, Mehnert F, Thomsen RW, Johnsen SP, Norgaard M. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Trends in Antirheumatic Drug Use, C-reactive Protein Levels, and Surgical Burden. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:2247–54. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC, Buch M, Burmester G, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:492–509. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Movahedi M, Costello R, Lunt M, Pye SR, Sergeant JC, Dixon WG. Oral glucocorticoid therapy and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:1045–55. doi: 10.1007/s10654-016-0167-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crowson C, Davis J, Major B, Matteson E, Therneau T, Gabriel S. Time trends in comorbidities among patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared to the general population [abstract] Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(Suppl 10) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agca R, Heslinga SC, Rollefstad S, Heslinga M, McInnes IB, Peters MJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory joint disorders: 2015/2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:17–28. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters MJ, Symmons DP, McCarey D, Dijkmans BA, Nicola P, Kvien TK, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:325–31. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.113696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van den Hoek J, Roorda LD, Boshuizen HC, Tijhuis GJ, Dekker J, van den Bos GA, et al. Trend in and predictors for cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis over a period of 15 years: a prospective cohort study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34:813–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Davis JM, III, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Decreased cardiovascular mortality in patients with incident rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in recent years: dawn of a new era in cardiovascualr disease in RA? [abstract] Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(Suppl 10) doi: 10.3899/jrheum.161154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]