Abstract

Background

Cell-free protein synthesis provides a robust platform for co-translational incorporation of noncanonical amino acid (ncAA) into proteins to facilitate biological studies and biotechnological applications. Recently, eliminating the activity of release factor 1 has been shown to increase ncAA incorporation in response to amber codons. However, this approach could promote mis-incorporation of canonical amino acids by near cognate suppression.

Methods

We performed a facile protocol to remove near cognate tRNA isoacceptors of the amber codon from total tRNAs, and used the phosphoserine (Sep) incorporation system as validation. By manipulating codon usage of target genes and tRNA species introduced into the cell-free protein synthesis system, we increased the fidelity of Sep incorporation at a specific position.

Results

By removing three near cognate tRNA isoacceptors of the amber stop codon [tRNALys, tRNATyr, and tRNAGln(CUG)] from the total tRNA, the near cognate suppression decreased by 5-fold without impairing normal protein synthesis in the cell-free protein synthesis system. Mass spectrometry analyses indicated that the fidelity of ncAA incorporation was improved.

Conclusions

Removal of near cognate tRNA isoacceptors of the amber codon could increase ncAA incorporation fidelity towards the amber stop codon in release factor deficiency systems.

General significance

We provide a general strategy to improve fidelity of ncAA incorporation towards stop, quadruplet and sense codons in cell-free protein synthesis systems.

Keywords: noncanonical amino acid, genetic code expansion, cell-free protein synthesis, tRNA isoacceptor, phosphoserine, near cognate suppression

1. Background

Emerging as a key discipline in the field of synthetic biology, the incorporation of noncanonical amino acids (ncAAs) into proteins has attracted tremendous attentions during last decade. Two distinct approaches were developed for this purpose, residue-specific incorporation and site-specific incorporation. Residue-specific incorporation utilizes auxotrophic strains and analogs of canonical amino acids to globally replace canonical residues with their analogs in proteins [1]. On the other hand, site-specific incorporation, which is also known as the genetic code expansion strategy, uses an orthogonal pair of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS) and tRNA to introduce an ncAA in response to an assigned codon (commonly the amber stop codon UAG) at a designed position in the protein of interest [2]. To date, more than 150 ncAAs have been incorporated into proteins as biophysical probes, photo-crosslinkers, post-translational modifications and drug conjugates [3, 4], providing powerful tools for biological studies and medical applications [5, 6].

Cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) is gaining ground as a method for ncAA incorporation, offering several advantages [7, 8]. First, CFPS can benefit from the relatively slower synthesis and the greater distance between ribosomes for proper protein folding [9]. Second, components in CFPS systems can be quantitatively controlled. Third, the open environment of CFPS systems allows the incorporation of ncAAs with low solubility or poor cell-uptake [10]. Moreover, CFPS systems are not constrained by cell-viability, thus facilitating expression of toxic proteins or membrane proteins [11, 12]. Furthermore, the toxicity from overexpressing orthogonal translation components such as aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, tRNAs, and ribosomes can be circumvented in CFPS systems [13]. However, cell-lysis procedures are difficult to standardize, resulting in different extract performance which confines the applications of cell-lysate based CFPS [7]. To address this issue, the PURE (Protein synthesis Using purified Recombinant Elements) system was developed [14]. It lacks both nucleases and proteases, stabilizing DNA, mRNA, and synthesized proteins. Moreover, it allows precise removal and addition of translation components for protein synthesis for ncAA incorporation.

In Escherichia coli, release factor 1 (RF1) recognizes the stop codons UAA and UAG, and RF2 recognizes UAA and UGA [15]. The ncAA incorporation in response to amber codons is limited by the competition between introduced suppressor tRNAs and endogenous RF1. Consequently, several approaches were performed to eliminate RF1 activity [16-20]. Most notably, the first genomically recoded E. coli strain was developed, in which all 321 TAG codons were mutated to synonymous TAA codons, allowing the deletion of RF1 without observed growth defects [21]. A similar strategy was also applied in CFPS systems with significantly improved ncAA incorporation, especially for the incorporation of identical ncAAs at multiple positions in target proteins [22-25]. Nevertheless, it has been noticed that natural suppression of amber codon by near cognate tRNAs exists under the circumstance of RF1 deletion, which results in impurity of amino acid composition at designed positions with amber codons [17, 21, 26, 27]. Exploiting the advantages of the PURE system, here we demonstrated a facile strategy to increase the fidelity of ncAA incorporation by manipulating the codon usage of target genes and tRNA species loaded in the PURE systems.

2. Methods

2.1. Chemicals and materials

DNA, RNA oligos, and biotin-tagged antisense DNA oligos were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The sequences are: anti-tRNAGln(CUG): 5′-TCGGAATGCC-GGAATCAGA-Biotin; anti-tRNAGln(UUG): 5′-AGGGAATGCCGGTATCAAA-Biotin; anti-tRNATyr: 5′-TTCGAAGTCGATGACGGCAGA-Biotin; and anti-tRNALys: 5′-CCTGCGACCAATTGATTAAA-Biotin; tRNASep transzyme: 5′-GCTTTTAGATCTTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGACCGGCTGATGAGTCCGTGAGGACGAAACGGTACCCGGTACCGTCGCCGGGGTAGTCTAGGGGTTAGGCAGCGGACTCTAGATCCGCCTTACGTGGGTTCAAATCCCACCCCCGGCTCCAGGAAGCTTACATCCGTCGACAAAAGC; the RF1-specific RNA aptamer: 5′-GGACCGAGAAGUUACCCUGUAAUCUUAGGAUGAAUCGCAUGCUCUAGCGACCUUUUCGGCUUCGGCGUACG CACAUCGCAGCAAC. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The PURExpress® Kits and Q5® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits were ordered from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Total tRNAs of E. coli were purchased from Roche (Switzerland).

2.2. Protocol of tRNA isoacceptor removal

24 nmol biotin-tagged antisense DNA oligo was mixed with 400 μL Streptavidin agarose beads (Sigma) in filter tubes (Durapore, 0.22 μm), and washed with 400 μL 10mM Tris (pH 7.6) three times. The beads were re-suspended with 400 μL 10mM Tris (pH 7.6), incubated at room temperature (RT) for 30 min with gentle shaking, and washed with 400 μL 10mM Tris (pH 7.6) three times again. According to the abundance of target tRNA isoacceptors in total tRNAs [28] and the ratio of antisense DNA oligos over target tRNAs (starting ratio is 3:1, varied in experiments), certain amount of total tRNAs were diluted with 300 μL water, unfolded by heating at 85°C for 10 min. Take the tRNATyr as an example, 24 nmol antisense DNA oligo works for 72 nmol tRNATyr as the starting ratio 3:1 of tRNA over the antisense oligo. The abundance of tRNATyr in total tRNA is 3.13%, and 72 nmol tRNATyr corresponds to 72/3.13% = 230 nmol total tRNA, so 230 nmol total tRNA should be used in tRNATyr removal against 24 nmol antisense DNA oligo. The unfolded tRNAs were quickly mixed with pre-heated 300 μL fresh 20mM Tris (pH 7.6), 1.8M TMA (tetra-methyl ammonium chloride), 0.2mM EDTA, and mixed with the pre-treated beads. The mixture was incubated at 65°C for 15 min, cooled to RT slowly, and washed with 400 μL 10mM Tris (pH 7.6). The tRNAs in flow-through was collected, precipitated with 250 mM NaCl and 3 volumes of ethanol, washed with 75% ethanol, dried and dissolved in water for additional cycles or later experiments.

2.3. SepRS and EF-Sep purification

Expression vectors for SepRS and EF-Sep were from the lab library, and transformed freshly into BL21 DE3 cells. The SepRS and EF-Sep sequences were from the previous publication [29]. The genes of SepRS and EF-Sep were cloned into pET15a plasmid with ampicillin resistance. The expression strains were grown in 500 ml of LB media supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37°C to an absorbance of 0.6-0.8 at 600 nm. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cells were incubated at 30°C for an additional 4 h and harvested by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The cell pastes were suspended in 15 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole) and broken by sonication. The crude extracts were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The soluble fractions were loaded onto columns containing 1 ml of Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen) previously equilibrated with 20 ml of lysis buffer. The columns were washed with 20 ml of lysis buffer. The proteins bound to the columns were then eluted with 2 ml of 50 mM Tris pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 200 mM imidazole. The purified proteins were desalted by PD-10 column (GE Life Sciences) with 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, and 50 mM KCl for further studies.

2.4. PURE reaction conditions

PURE reactions were performed following the manufacturer protocols. Briefly, each reaction was 25 μL in volume. 300 ng of target gene templates generated by PCR with T7 promoter and terminator introduced by primers was loaded in each reaction. tRNAs without target tRNA isoacceptors were added in the same amount with the original totals tRNA supplied in the PURExpress kit. tRNASep (The sequence was from the previous publication [29]) was introduced in the form of transzyme containing T7 promoter and hammerhead ribozyme according to the previous study [30]. 100 ng of the PCR product was loaded in each reaction. 25 μg purified SepRS, 25 μg EF-Sep and 2 mM Sep were added into PURE reactions. The samples were incubated at 30°C for 20 hours. The reaction mixture was loaded into a 384-well plate and the fluorescent intensity was read by the micro-plate reader.

2.5. Mass spectroscopy analysis

The reaction mixture was loaded onto SDS-PAGE gel. The bands with the corresponding molecular weight of sfGFP were cut and sent for MS analysis. The primary sequence of sfGFP: MSKGEELFTGVVPILVELDGDVNGHKFSVRGEGEGDATNGKLTLKFICTTGKLPVPWPTLVTTLTYGVQCFSRYPDHMKRHDFFKSAMPEGYVQERTISFKDDGTYKTRAEVKFEGDTLVNRIELKGIDFKEDGNILGHKLEYNFNSHNVYITADKQKNGIKANFKIRHNVEDGSVQLADHYQQNTPIGDGPVLLPDNHYLSTQSVLSKDPNEKRDHMVLLEFVTAAGITHGMDELYKGS with the substitution position underlined. The proteins were trypsin digested by a standard in-gel digestion protocol, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS on an LTQ Orbitrap XL (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a nanoACQUITY UPLC system (Waters). A Symmetry C18 trap column (180 μm × 20 mm; Waters) and a nanoACQUITY UPLC column (1.7 μm, 100 μm × 250 mm, 35°C) were used for peptide separation. Trapping was done at 15 μL min-1, 99% buffer A (water with 0.1% formic acid) for 1 min. Peptide separation was performed at 300 nL min-1 with buffer A and buffer B (CH3CN containing 0.1% formic acid). The linear gradient was from 5% buffer B to 50% B at 50 min, to 85% B at 51 min. MS data were acquired in the Orbitrap with one microscan, and a maximum inject time of 900 ms followed by data-dependent MS/MS acquisitions in the ion trap (through collision induced dissociation, CID). The Mascot search algorithm was used to determine the amino acid composition at specific positions (Matrix Science, Boston, MA).

3. Results

3.1. Experimental design

Previous studies showed that the contamination of canonical amino acids at amber codons in CFPS systems is mainly from glutamine, as well as low level of tyrosine, glutamate, lysine, and glycine [22, 24], which is reasonable because codons for tyrosine (UAU and UAC), lysine (AAG), glutamine (CAG) and glutamate (GAG) have only one nucleotide difference from amber codon (UAG). In E. coli, there is only one species of tRNA isoacceptor for glutamate and lysine, respectively, while tyrosine and glutamine have two species of tRNA isoacceptors, individually [31]. The two species of tRNATyr isoacceptors have the same anticodon (GUA), decoding both tyrosine codons (UAU and UAC). The two species of tRNAGln isoacceptors are distinct: the one with anticodon UUG decodes for CAA codon, and the one with anticodon CUG decodes for CAG codon [28]. In this study, we chose the tRNALys isoacceptor, one tRNATyr isoacceptor, and two tRNAGln isoacceptors to remove from total tRNA. Our aim was to increase the ncAA incorporation fidelity by eliminating or decreasing the competition between introduced suppressor tRNAs and near cognate tRNA isoacceptors in the background of impaired RF1 activity. The sequences of specific antisense DNA oligos for those tRNA isoacceptors were based on previous reports [28], and were listed in the Methods section. We chose superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP) as a reporter, which was engineered to have improved tolerance of circular permutation, greater resistance to chemical denaturants, and enhanced folding kinetics, thus being widely used in the field of genetic code expansion [32, 33]. And we selected phosphoserine (Sep) incorporation system [29], which recently has been used in CFPS systems to make phosphoprotein but with the contamination from near-cognate suppression [22].

3.2. Near cognate suppression of stop codons

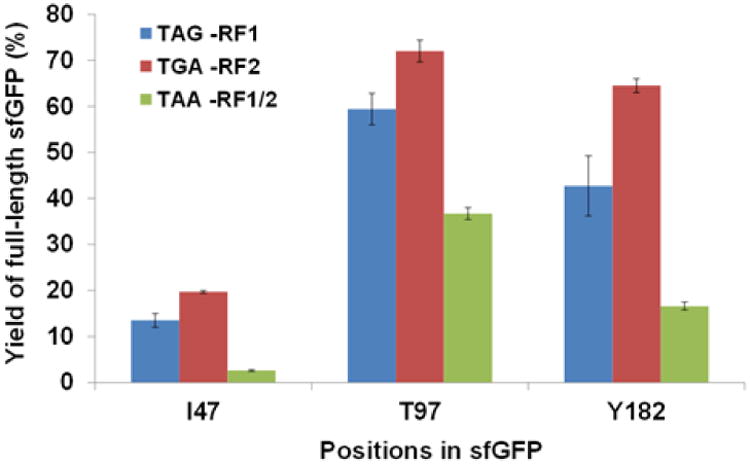

To determine the near cognate suppression for three stop codons, selected positions in sfGFP gene were mutated to TAG, TGA, and TAA, respectively. The sfGFP gene uses TAA as the stop codon. To demonstrate the effects of residue positions, we chose permissive positions 47, 97, and 182 which are in different regions of sfGFP. Here, we used PURExpress® ∆RF123 Kit in which RF1, RF2, and RF3 are provided separately. For amber codon (UAG) suppression, RF1 was not loaded into the PURE reaction. For opal codon (UGA) suppression, RF2 was not loaded. For ochre codon (UAA) suppression, both RF1 and RF2 were not loaded. Compared with the fluorescence intensity of wild-type sfGFP expressed in the same PURE reaction, the readings for expression of sfGFP genes with stop codons indicated the near cognate suppression efficiency in the absence of an orthogonal translation system (Fig.1). The suppression efficiency varied dramatically at different positions. The near cognate suppression for opal codon (UGA) was higher than that for amber codon (UAG) or ochre codon (UAA) in all the positions tested. Surprisingly, the near cognate suppression of amber codon could reach as high as 60% of the wild-type protein expression, raising the issue of ncAA incorporation fidelity in systems without the RF1 activity.

Fig.1. Near cognate suppression of stop codons.

The expression of wild-type sfGFP was set as 100%. The mean values and standard errors were calculated from three replicates. The original codons for I47, T97, and Y182 were mutated to TAG (Blue), TGA (Red), and TAA (Green), individually.

3.3. Eliminating RF1 activity with an RNA aptamer

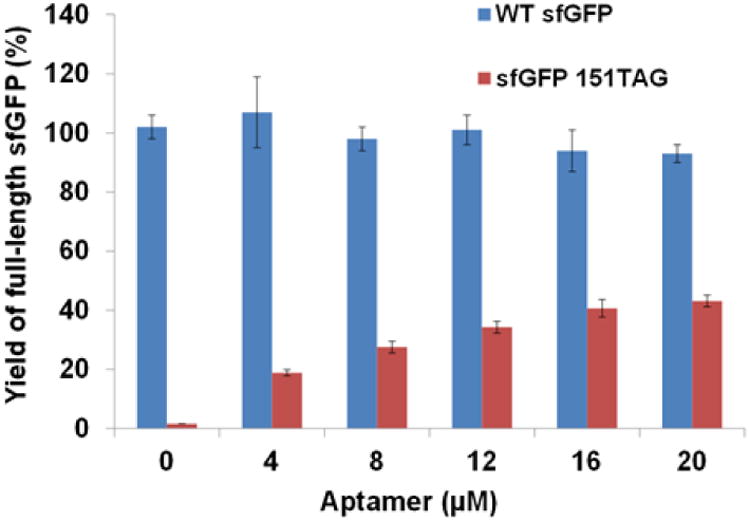

In later studies, we focused on amber suppression. And we chose ncAA incorporation position at 151 of sfGFP which was well studied before [33]. The near cognate suppression efficiency of the amber codon at position 151 in sfGFP was 47.5%, determined by the same method described above. Here, we used PURExpress® ∆(aa, tRNA) Kit in which amino acids and tRNAs were added separately. To eliminate the RF1 activity in PURE system, we used an RF1-specific RNA aptamer following a previously developed method [34]. The dose effect of the RNA aptamer in the absence of an orthogonal translation system was shown in Fig.2. Without impairing the wild-type sfGFP synthesis significantly, 20 μM RNA aptamer could inhibit RF1 activity sufficiently. The near cognate suppression with 20 μM RNA aptamer was similar to that of the PURE reaction without adding RF1. Thus, 20 μM RNA aptamer was used in later experiments.

Fig.2. Dose effect of the RF1-specific RNA aptamer.

The expression of wild-type sfGFP was set as 100%. The mean values and standard errors were calculated from three replicates.

3.4. Decreasing near cognate suppression

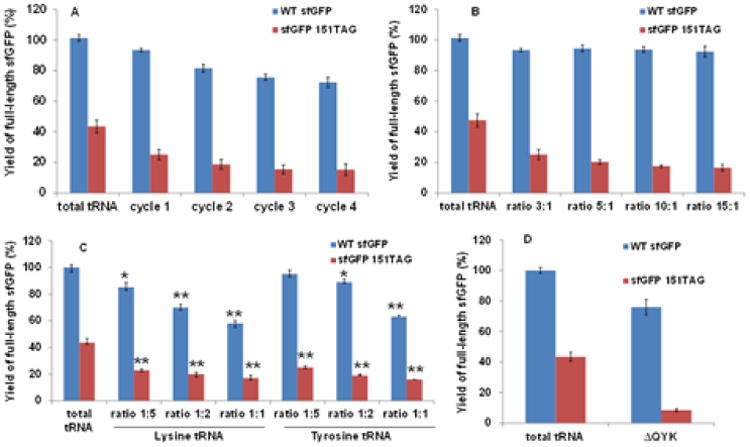

For tRNA isoacceptors for glutamine, we firstly removed tRNAGln(CUG) from total tRNAs of E. coli with several cycles of tRNA isoacceptor removal by biotin-tagged antisense DNA oligos, and loaded in the PURE reaction with impaired RF1 activity. Correspondingly, we changed all CAG codons in sfGFP gene to CAA codons to eliminate the effect of tRNAGln(CUG) isoacceptor removal on wild-type protein synthesis, and the expression of sfGFP gene with all glutamine residues assigned to CAA codon was similar with that of the original sfGFP gene. The effects of tRNAGln(CUG) removal on wild-type protein expression and near cognate suppression were listed in Fig.3A. We could see that the tRNA removal protocol decreased both near cognate suppression and wild-type protein synthesis. After two cycles of tRNA isoacceptor removal, the efficiency of wild-type protein expression decreased about 20%. This may be caused by the repeating tRNA unfolding and refolding processes. To solve this problem, we increased the ratio of antisense DNA oligos over target tRNA isoacceptor, and only performed tRNA isoacceptor removal once (Fig.3B). Using 10-fold amount of antisense DNA oligos removed 90% of the near cognate suppression from tRNAGln(CUG) with only one cycle of tRNA isoacceptor removal. Then, we applied the same strategy to another isoacceptor tRNAGln(UUG). However, there was no obvious effect (Fig.S1), which is reasonable that tRNAGln(CUG) has only one nucleotide difference with the amber anticodon (CUA) while tRNAGln(UUG) has two nucleotide difference with the amber anticodon (CUA). Thus, the mis-incorporation of glutamine at the amber stop codon is mostly caused by tRNAGln(CUG).

Fig.3. Effect of tRNA isoacceptor removal.

A. Effects of cycles of tRNAGln(CUG) removal. B. Effects of antisense DNA oligo amounts for tRNAGln(CUG). C. Effects of antisense DNA oligo amounts for tRNA isoacceptors for lysine and tyrosine. * indicates significant difference (p<0.01), and ** indicates highly significant difference (p<0.001). D. Effects of removal of tRNA isoacceptors for glutamine, lysine and tyrosine. The expression of wild-type sfGFP was set as 100%. The mean values and standard errors were calculated from three replicates.

In E. coli, there is only one species of tRNA isoacceptor for lysine, and two species of isoacceptors with the same anticodon for tyrosine. Thus, changing codon usage in target genes cannot overcome the effects of tRNA isoacceptor removal on wild-type protein synthesis. Here, we reduced the ratio of antisense DNA oligos over target tRNA isoacceptors. The results were shown in Fig.3C. As expected, removing these tRNA isoacceptors decreased the wild-type protein synthesis. However, the decrease of near cognate suppression was more significant. When the ratio of the antisense DNA oligo for tRNALys (anti-tRNALys) over tRNALys was 1:5, we could lower near cognate suppression to 50% with only 15% decrease of wild-type protein synthesis. The optimal ratio of anti-tRNATyr over tRNATyr is 1:2, with which we could lower near cognate suppression to 50% with only 10% decrease of wild-type protein synthesis.

Combining the above results together, we mixed the anti-tRNAGln(CUG) (10-fold amount of tRNAGln), the anti-tRNALys (one fifth amount of tRNALys), and the anti-tRNATyr (half amount of tRNATyr) with beads simultaneously, and performed the three tRNA isoacceptor removal process from total tRNAs only one cycle (∆QYK tRNAs) (Fig.3D). The near cognate suppression was reduced to 5% with only 20% decrease of wild-type protein synthesis.

3.5. Increasing Sep incorporation fidelity

To check the ncAA incorporation fidelity, we introduced the orthogonal translation system for Sep incorporation in PURE reactions. SepRS and EF-Sep were added as purified proteins. And tRNASep was added in the form of transzyme as previous studies [24, 30]. The full-length sfGFP proteins harboring an amber codon at position 151 were expressed in the PURE reactions with total or ∆QYK tRNAs, and analyzed by MS. The amino acid compositions were listed in Table 1 (MS spectra were listed in Fig.S2-S10). When the total tRNA was added, tyrosine, glutamine, lysine, and glycine were detected which is consistent with the previous report [22]. Additionally, we detected serine residue at position 151 in the PURE reaction which may result from the dephosphorylation of Sep. With ∆QYK tRNAs added, we did not detect tyrosine, glutamine, and lysine residues at position 151, and the MS quality was improved for Sep incorporation (Figure S7 and S8). Recently, a new approach was developed to purify phosphoserine-containing proteins away from mistranslated products with canonical amino acids incorporated towards the stop codon in the living cells of an RF1-deficient E. coli strain [35], which could be a nice complementary with our strategy to obtain phosphoproteins with high purity for further studies.

Table 1.

The amino acid compositions at sfGFP position 151 by MS analysis.

| Amino Acid | Peptide sequence | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Total tRNAs | ||

| glycine (G) | LEYNFNSHNVGITADK | 130 |

| serine (S) | LEYNFNSHNVSITADK | 104 |

| tyrosine (Y) | LEYNFNSHNVYITADK | 90 |

| lysine (K) | LEYNFNSHNVK | 66 |

| glutamine (Q) | LEYNFNSHNVQITADKQK | 60 |

| phosphoserine | GIDFKEDGNILGHKLEYNFNSHNVSPITADK | 43 |

|

| ||

| ∆QYK tRNAs | ||

| phosphoserine | EDGNILGHKLEYNFNSHNVSPITADK | 72 |

| serine (S) | LEYNFNSHNVSITADK | 67 |

| glycine (G) | LEYNFNSHNVGITADK | 63 |

4. Discussion

Suppression from near cognate tRNAs is affected by a variety of factors: (1) the concentration of aminoacylated tRNAs; (2) base-pairing strength; and (3) binding to elongation factors and ribosomes. For amber codon suppression in the systems without RF1 activity, the suppressor tRNA needs to outcompete near cognate tRNAs to generate pure ncAA incorporation, which depends on the efficiency of the introduced orthogonal pairs. However, poor efficiency of engineered orthogonal pairs is still the most critical problem in the field of genetic code expansion [3]. Thus, our method is particularly useful for orthogonal pairs with relative low efficiency.

Beyond amber codon suppression, some effort has been made to access additional codons for ncAA incorporation such as quadruplet codons [36, 37]. However, even the pair of wild-type pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase and tRNAPyl with UCCU anticodon (for AGGA quadruplet codon suppression), which efficiently generates aminoacylated tRNAs, cannot outcompete near cognate suppression from endogenous tRNAArg(CCU) which decodes AGG codon [25]. tRNAArg(CCU) is the only tRNA isoacceptor for AGG codon, so ncAA incorporation fidelity at AGGA quadruplet codon will be improved by using our strategy to remove tRNAArg(CCU) from total tRNA.

Currently, site-specific incorporation of one or two different kinds of ncAAs into proteins cannot meet the need of the rapid development of synthetic biology. More codons like sense codons which are naturally assigned for canonical amino acids should be open for ncAA incorporation. Rare codons are usually considered to be promising targets [38]. Moreover, combined with the Flexizyme system, even frequently used sense codons could be used for ncAA incorporation [39, 40]. Due to the flexibility of CFPS systems, gene templates can be controlled with codon usage for sense codon suppression [41]. In this case, our strategy is useful for removing both specific tRNA isoacceptors and near cognate tRNAs for the chosen sense codons, thus increasing ncAA incorporation at designed sense codons. In summary, we provide a general strategy to improve fidelity of ncAA incorporation towards stop codons, which could also be applicable to quadruplet and sense codons.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Near cognate suppression of amber, opal, and ochre stop codons were examined in the PURE system.

A facile protocol of inhibiting RF1 activity in PURE systems was performed.

A facile protocol of removing target tRNA isoacceptors from total tRNAs was performed.

The purity of phosphoserine incorporation was increased by manipulating codon usage of target genes and tRNA species introduced into the PURE system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Dieter Söll at Yale University for generous support. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI119813), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM22854), and start-up funds from University of Arkansas.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Johnson JA, Lu YY, Van Deventer JA, Tirrell DA. Residue-specific incorporation of non-canonical amino acids into proteins: recent developments and applications. Curr Opin ChemBiol. 2010;14:774–780. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu CC, Schultz PG. Adding new chemistries to the genetic code. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:413–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.105824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Donoghue P, Ling J, Wang YS, Soll D. Upgrading protein synthesis for synthetic biology. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:594–598. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoesl MG, Budisa N. Recent advances in genetic code engineering in Escherichia coli. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2012;23:751–757. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumann H. Rewiring translation - Genetic code expansion and its applications. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2057–2064. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis L, Chin JW. Designer proteins: applications of genetic code expansion in cell biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:168–182. doi: 10.1038/nrm3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong SH, Kwon YC, Jewett MC. Non-standard amino acid incorporation into proteins using Escherichia coli cell-free protein synthesis. Front Chem. 2014;2:34. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quast RB, Mrusek D, Hoffmeister C, Sonnabend A, Kubick S. Cotranslational incorporation of non-standard amino acids using cell-free protein synthesis. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:1703–1712. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenblum G, Cooperman BS. Engine out of the chassis: cell-free protein synthesis and its uses. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bundy BC, Swartz JR. Site-specific incorporation of p-propargyloxyphenylalanine in a cell-free environment for direct protein-protein click conjugation. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;21:255–263. doi: 10.1021/bc9002844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Worst EG, Exner MP, De Simone A, Schenkelberger M, Noireaux V, Budisa N, Ott A. Cell-free expression with the toxic amino acid canavanine. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25:3658–3660. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henrich E, Hein C, Dotsch V, Bernhard F. Membrane protein production in Escherichia coli cell-free lysates. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:1713–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nehring S, Budisa N, Wiltschi B. Performance analysis of orthogonal pairs designed for an expanded eukaryotic genetic code. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimizu Y, Inoue A, Tomari Y, Suzuki T, Yokogawa T, Nishikawa K, Ueda T. Cell-free translation reconstituted with purified components. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:751–755. doi: 10.1038/90802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scolnick E, Tompkins R, Caskey T, Nirenberg M. Release factors differing in specificity for terminator codons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1968;61:768–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.61.2.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson DB, Wang C, Xu J, Schultz MD, Schmitz RJ, Ecker JR, Wang L. Release factor one is nonessential in Escherichia coli. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:1337–1344. doi: 10.1021/cb300229q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson DB, Xu J, Shen Z, Takimoto JK, Schultz MD, Schmitz RJ, Xiang Z, Ecker JR, Briggs SP, Wang L. RF1 knockout allows ribosomal incorporation of unnatural amino acids at multiple sites. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:779–786. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukai T, Hayashi A, Iraha F, Sato A, Ohtake K, Yokoyama S, Sakamoto K. Codon reassignment in the Escherichia coli genetic code. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:8188–8195. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinemann IU, Rovner AJ, Aerni HR, Rogulina S, Cheng L, Olds W, Fischer JT, Soll D, Isaacs FJ, Rinehart J. Enhanced phosphoserine insertion during Escherichia coli protein synthesis via partial UAG codon reassignment and release factor 1 deletion. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:3716–3722. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang B, Yang Q, Chen J, Wu L, Yao T, Wu Y, Xu H, Zhang L, Xia Q, Zhou D. CRISPRi-Manipulation of Genetic Code Expansion via RF1 for Reassignment of Amber Codon in Bacteria. Scientific reports. 2016;6:20000. doi: 10.1038/srep20000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lajoie MJ, Rovner AJ, Goodman DB, Aerni HR, Haimovich AD, Kuznetsov G, Mercer JA, Wang HH, Carr PA, Mosberg JA, Rohland N, Schultz PG, Jacobson JM, Rinehart J, Church GM, Isaacs FJ. Genomically recoded organisms expand biological functions. Science. 2013;342:357–360. doi: 10.1126/science.1241459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oza JP, Aerni HR, Pirman NL, Barber KW, Ter Haar CM, Rogulina S, Amrofell MB, Isaacs FJ, Rinehart J, Jewett MC. Robust production of recombinant phosphoproteins using cell-free protein synthesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8168. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong SH, Kwon YC, Martin RW, Des Soye BJ, de Paz AM, Swonger KN, Ntai I, Kelleher NL, Jewett MC. Improving cell-free protein synthesis through genome engineering of Escherichia coli lacking release factor 1. Chembiochem. 2015;16:844–853. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong SH, Ntai I, Haimovich AD, Kelleher NL, Isaacs FJ, Jewett MC. Cell-free protein synthesis from a release factor 1 deficient Escherichia coli activates efficient and multiple site-specific nonstandard amino acid incorporation. ACS Synth Biol. 2014;3:398–409. doi: 10.1021/sb400140t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukai T, Yanagisawa T, Ohtake K, Wakamori M, Adachi J, Hino N, Sato A, Kobayashi T, Hayashi A, Shirouzu M, Umehara T, Yokoyama S, Sakamoto K. Genetic-code evolution for protein synthesis with non-natural amino acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;411:757–761. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aerni HR, Shifman MA, Rogulina S, O'Donoghue P, Rinehart J. Revealing the amino acid composition of proteins within an expanded genetic code. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Donoghue P, Prat L, Heinemann IU, Ling J, Odoi K, Liu WR, Soll D. Near-cognate suppression of amber, opal and quadruplet codons competes with aminoacyl-tRNAPyl for genetic code expansion. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:3931–3937. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong H, Nilsson L, Kurland CG. Co-variation of tRNA abundance and codon usage in Escherichia coli at different growth rates. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:649–663. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park HS, Hohn MJ, Umehara T, Guo LT, Osborne EM, Benner J, Noren CJ, Rinehart J, Soll D. Expanding the genetic code of Escherichia coli with phosphoserine. Science. 2011;333:1151–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.1207203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albayrak C, Swartz JR. Cell-free co-production of an orthogonal transfer RNA activates efficient site-specific non-natural amino acid incorporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:5949–5963. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan PP, Lowe TM. GtRNAdb: a database of transfer RNA genes detected in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D93–97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan C, Ho JM, Chirathivat N, Soll D, Wang YS. Exploring the substrate range of wild-type aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Chembiochem. 2014;15:1805–1809. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan C, Xiong H, Reynolds NM, Soll D. Rationally evolving tRNAPyl for efficient incorporation of noncanonical amino acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e156. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sando S, Ogawa A, Nishi T, Hayami M, Aoyama Y. In vitro selection of RNA aptamer against Escherichia coli release factor 1. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:1216–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.George S, Aguirre JD, Spratt DE, Bi Y, Jeffery M, Shaw GS, O'Donoghue P. Generation of phospho-ubiquitin variants by orthogonal translation reveals codon skipping. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:1530–1542. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson JC, Wu N, Santoro SW, Lakshman V, King DS, Schultz PG. An expanded genetic code with a functional quadruplet codon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7566–7571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401517101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neumann H, Wang K, Davis L, Garcia-Alai M, Chin JW. Encoding multiple unnatural amino acids via evolution of a quadruplet-decoding ribosome. Nature. 2010;464:441–444. doi: 10.1038/nature08817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krishnakumar R, Ling J. Experimental challenges of sense codon reassignment: an innovative approach to genetic code expansion. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramaswamy K, Saito H, Murakami H, Shiba K, Suga H. Designer ribozymes: programming the tRNA specificity into flexizyme. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:11454–11455. doi: 10.1021/ja046843y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohuchi M, Murakami H, Suga H. The flexizyme system: a highly flexible tRNA aminoacylation tool for the translation apparatus. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kanda T, Takai K, Hohsaka T, Sisido M, Takaku H. Sense codon-dependent introduction of unnatural amino acids into multiple sites of a protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:1136–1139. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.