Abstract

Background

Reductions in breast density with tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors may be an intermediate marker of treatment response. We compare changes in volumetric breast density among breast cancer cases using tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors (AI) to untreated women without breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Breast cancer cases with a digital mammogram prior to diagnosis and after initiation of tamoxifen (n=366) or AI (n=403), and a sample of controls (n=2170) were identified from the Mayo Clinic Mammography Practice and San Francisco Mammography Registry. Volumetric percent density (VPD) and dense breast volume (DV) were measured using Volpara™ (Matakina Technology) and Quantra™ (Hologic) software. Linear regression estimated the effect of treatment on annualized changes in density.

Results

Premenopausal women using tamoxifen experienced annualized declines in volumetric percent density of 1.17% to 1.70% compared with 0.30% to 0.56% for controls and declines in dense breast volume of 7.43 cm3 to 15.13 cm3 compared with 0.28 cm3 to 0.63 cm3 in controls, for Volpara and Quantra respectively. The greatest reductions were observed among women with ≥10% baseline density. Postmenopausal AI-users had greater declines in volumetric percent density than controls (Volpara p=0.02; Quantra p=0.03), and reductions were greatest among women with ≥10% baseline density. Declines in volumetric percent density among postmenopausal women using tamoxifen were only statistically greater than controls when measured with Quantra.

Conclusions

Automated software can detect volumetric breast density changes among women on tamoxifen and AI.

Impact

If declines in volumetric density predict breast cancer outcomes, these measures may be used as interim prognostic indicators.

Introduction

Tamoxifen is a well-established therapy for estrogen-receptor (ER) positive breast cancer, and is used primarily to treat premenopausal breast cancer.(1) Treatment with tamoxifen reduces breast density in approximately 30–60% of breast cancer cases,(2,3) with greater declines observed among premenopausal women and women with high breast density. Reductions in breast density of 10–20% with tamoxifen have been associated with a reduced risk of recurrence and mortality among both premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer cases, as well as reduced risk of breast cancer among high-risk women taking tamoxifen for primary prevention.(4–8)

Aromatase inhibitors (AI) decrease levels of circulating estrone and estradiol and are prescribed as adjuvant treatment for ER-positive breast cancer in postmenopausal women.(9,10) Research evaluating the effect of AI on breast density has been less consistent than tamoxifen. Though several studies have found reductions in breast density among postmenopausal breast cancer cases taking AI,(11,12) studies comparing changes to untreated women found no difference in density decline.(13,14) Changes in breast density among postmenopausal women taking AI as primary prevention have largely had null findings,(15–17) though one study found that women taking AI and postmenopausal hormone therapy experienced greater declines in breast density compared with women on postmenopausal hormones alone.(18) Similar to tamoxifen, reductions in breast density with AI may signal improved prognosis; a study by Kim et al.(7) found that women on AI who did not have a decline in density had a 7-fold increased risk of recurrence relative to women with a reduction of 5% or greater.

Prior literature assessing longitudinal changes in breast density has principally used operator-dependent techniques that measure the two-dimensional area of dense breast tissue on digitized mammography. Full-field digital mammography (FFDM) has advanced the development of automated software that measures volumetric breast density in three-dimensions, and early studies confirm that volumetric breast density is predictive of breast cancer risk.(19–21) Research has not assessed response to treatment with tamoxifen and AI using volumetric density measures on FFDM, though a few studies using MRI suggest volumetric measures may more accurately measure density changes.(22,23) If volumetric density measures from FFDM provide precise estimates of longitudinal change in breast density, they may be used clinically to provide important prognostic information.

We aim to assess the effect of tamoxifen and AI on changes in breast density by comparing annualized changes among breast cancer cases to women without breast cancer not using tamoxifen or AI to account for natural declines in breast density with age among cases. We use two volumetric breast density measures obtained from FFDM and currently used in clinical practice,(19) Volpara™(24) and Quantra™(25), to assess longitudinal changes with therapy.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Participants were sampled from two breast imaging cohorts: the San Francisco Mammography Registry (SFMR) and the Mayo Clinic Breast Screening Practice, described below, and in detail elsewhere.(19)

San Francisco Mammography Registry (SFMR)

The SFMR is a population-based mammography registry collecting demographic, risk factor, and mammographic information on women undergoing mammography at 22 facilities in the San Francisco Bay Area. We included four SFMR facilities that have obtained raw digital images from Selenia-Hologic mammography machines since 2006. The SFMR links to the California Cancer Registry (CCR), which includes data from Northern and Southern California Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Programs for information on cancer diagnoses. Passive permission to participate in research is obtained at each mammography visit.

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Breast Screening Practice

Patients within the Mayo Clinic Rochester Breast Screening practice residing in Minnesota, Iowa and Wisconsin were eligible for this study. Tri-state women presenting for screening mammography at Mayo comprise a regional cohort of women likely to return to Mayo for subsequent breast cancer diagnosis and treatment.(26) Patients consenting to Research Authorization allow medical records, images and cancer data to be used for research (93% response rate). Breast cancer cases are ascertained via linkage to the Mayo Clinic Tumor Registry.

Participants

Women diagnosed with invasive (n=674) or in situ (n=95) breast cancer with a mammogram within 48 months prior to diagnosis and a subsequent mammogram at least one year following initiation of tamoxifen or AI were eligible to be included if they were on treatment at the time of the exam. For the pre-treatment mammogram, the exam closest to date of diagnosis was selected (median months prior to diagnosis: 0.6, IQR: 0.2–2.1). The last available mammogram while the woman was still on treatment was selected as the subsequent mammogram (median months post-diagnosis: 31.5, IQR: 23.6–40.3). Women without breast cancer with two or more mammograms at least 6 months apart, over the same time period as the cases and not using tamoxifen, AI or postmenopausal hormones were selected as controls. 35 breast cancer cases and 37 controls were excluded due to unknown menopause status; sensitivity analyses including women of unknown menopause status did not alter results. 17 premenopausal women transitioned from tamoxifen to AI over the study period and 31 women took tamoxifen and AI’s concurrently; these women were included in the tamoxifen group. Sensitivity analyses excluding women taking both tamoxifen and AI did not alter results. There were a total of 366 breast cancer cases on tamoxifen, 403 breast cancer cases on AI, and 2170 controls included in the analysis.

Treatment and Covariate Data

Demographic, risk factor, and treatment data were ascertained from questionnaires at mammography visits for women in the SFMR. Treatment duration was estimated by length of time between examinations that both confirmed hormone therapy use. Treatment data for women diagnosed at the Mayo Clinic were ascertained through linkage with the Mayo Clinic Tumor Registry and medical record abstraction. Covariate data including age, body mass index (BMI), race/ethnicity, menopause status, parity, and first-degree family history of breast cancer were obtained from baseline questionnaire (SFMR) or electronic medical records (Mayo). Change in BMI was calculated between first and last mammograms.

Breast Density Measurement

Raw (“for processing”) mammograms were collected and stored, and automated breast density measures Volpara™ and Quantra™ were run on all contralateral images for cases and one randomly chosen side for controls.

Volpara and Quantra Software

Volpara™ (Version 1.5.0; Matakina Technology, New Zealand) and Quantra™ (Version 2.0; Hologic, Bedford, US) are fully automated software systems that use different proprietary algorithms to estimate volumetric breast density. Both software types have been described in detail elsewhere.(19,20,27,25) Briefly, Volpara and Quantra use measurements of breast thickness and x-ray attenuations to estimate the amount of dense and non-dense tissue at each pixel in the mammogram. Estimates of the overall dense breast volume (DV) are obtained by summing over the estimated dense tissue volume at each pixel. The dense breast volume is divided by the total breast volume and multiplied by 100 to obtain volumetric percent density (VPD). We measured breast density on the cranio-caudal (CC) and medio-lateral oblique (MLO) views for each woman. The final density value is estimated as the ratio of highest DV to total volume from either view for Quantra, and the average VPD of both views for Volpara.

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics of the study populations are summarized by median and quartiles or frequency and percentage. VPD and DV estimates at each mammogram were plotted against time to visually assess evidence of linearity of changes. Density change was found to be approximately linear with time, therefore annualized changes were estimated by fitting linear regression models for each density measure with time from initial mammogram. Assessing annualized changes in breast density allowed for variation in duration of treatment across groups. Multivariable linear regression models were used to estimate the effect of treatment type (tamoxifen or AI vs. control) on annualized change in breast density, adjusting for age, baseline BMI, change in BMI, natural logarithm of baseline volumetric density, and study site. Confounding by race/ethnicity, parity, and family history of breast cancer were evaluated and adjusted estimates were similar; thus, results shown are not adjusted for these variables. Separate models were fitted for software type and menopause status. F-test p-values compared the changes in treatment groups compared to controls separately for each endpoint (VPD and DV) and software type (Volpara and Quantra) by menopause status. In secondary analyses, models assessed the effect of treatment on relative change in VPD, where point estimates reflect the percent reduction in VPD relative to the baseline VPD, and inferences were consistent with models using absolute changes (eSupplement, Table 1). Further analyses were stratified by baseline VPD of <10% vs. ≥10% for consistency with prior literature.(7,8,28) To directly assess differences in software types, data for both Volpara and Quantra were entered into the same model with an interaction between software type and treatment. We used a repeated measures mixed model analysis to account for correlation between measurements taken on the same woman from the two software types; we did not impose a structure on the correlation but allowed the model to estimate the correlation from the data. Models for interaction were fit separately for premenopausal and postmenopausal women and for VPD and DV. All tests of statistical significance were two-sided and p-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4.

Results

Characteristics of the 366 women on tamoxifen, 403 women on AI, and 2170 controls are displayed in Table 1 (Table 1). Women treated with AI were exclusively postmenopausal, while tamoxifen-users were premenopausal or postmenopausal in roughly equal proportions. Premenopausal tamoxifen-users were similar in age and BMI to premenopausal controls, however among postmenopausal women, tamoxifen-users tended to be younger and have a lower BMI relative to AI-users and controls. The median time between earliest and latest mammogram was 3 years for breast cancer cases and 2 years for controls.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population by treatment type.

| Premenopausal | Postmenopausal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tamoxifen (N=180) |

Control (N=552) |

Tamoxifen (N=186) |

Aromatase Inhibitors (N=403) |

Control (N=1618) |

||

| median (Q1,Q3) | median (Q1,Q3) | median (Q1,Q3) | median (Q1,Q3) | median (Q1,Q3) | ||

| Age at index mammogram | 44 (40, 47) | 45 (42, 48) | 59 (53, 67) | 63 (58, 71) | 64 (57, 71) | |

| Age at diagnosis | 45 (42, 48) | 60 (54, 68) | 64 (59, 72) | |||

| Time between first and last mammogram |

3.0 (2.2, 4.0) | 2.1 (1.2, 2.8) | 3.0 (2.1, 3.5) | 3.0 (2.0, 3.9) | 2.0 (1.2, 2.8) | |

| Baseline BMI | 23.0 (20.8, 25.7) | 24.0 (21.5, 27.9) | 24.5 (22.3, 28.3) | 25.8 (22.7, 29.9) | 25.7 (22.7, 30.0) | |

| Change in BMI | 0.1 (−0.5, 1.0) | 0.0 (−0.5, 0.8) | 0.1 (−0.5, 1.2) | 0.0 (−1.0, 0.8) | 0.0 (−0.7, 0.8) | |

| Baseline volumetric density (%) |

||||||

| Volpara | 16.0 (10.4, 23.4) | 12.2 (7.2, 18.5) | 8.4 (5.3, 13.9) | 7.0 (4.9, 10.9) | 6.2 (4.4, 9.8) | |

| Quantra | 17.3 (12.9, 23.8) | 13.6 (9.5, 18.8) | 11.0 (7.4, 16.5) | 9.7 (7.0, 14.0) | 8.2 (5.9, 11.7) | |

| Baseline dense volume (cm3) | ||||||

| Volpara | 76.0 (50.0, 101.5) | 62.3 (41.9, 86.9) | 57.8 (40.5, 78.1) | 51.4 (38.4, 67.8) | 47.4 (36.1, 65.7) | |

| Quantra | 103.5 (62.0, 156.0) | 85.5 (53.0, 132.0) | 90.0 (53.0, 129.0) | 77.0 (48.0, 125.0) | 70.0 (43,0, 112.0) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Caucasian | 104 (58%) | 403 (73%) | 128 (69%) | 298 (74%) | 1339 (83%) | |

| African American | 3 (2%) | 6 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 12 (3%) | 22 (1%) | |

| Asian | 55 (31%) | 112 (20%) | 46 (25%) | 74 (18%) | 194 (12%) | |

| Other | 18 (10%) | 31 (6%) | 8 (4%) | 19 (5%) | 63 (4%) | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | ||||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 127 (71%) | 335 (61%) | 101 (54%) | 179 (44%) | 723 (45%) | |

| 25–29 kg/m2 | 35 (19%) | 115 (21%) | 53 (29%) | 125 (31%) | 488 (30%) | |

| 30–34 kg/m2 | 13 (7%) | 58 (10%) | 17 (9%) | 52 (13%) | 251 (15%) | |

| ≥ 35 kg/m2 | 5 (3%) | 44 (8%) | 15 (8%) | 43 (11%) | 156 (10%) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Postmenopausal hormone therapy |

||||||

| Not Current Users | 180 (100%) | 552 (100%) | 136 (73%) | 279 (69%) | 1618 (100%) | |

| Current User | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 37 (20%) | 74 (18%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (7%) | 50 (12%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Parity | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 75 (42%) | 158 (29%) | 73 (39%) | 116 (29%) | 318 (20%) | |

| Parous | 104 (58%) | 394 (71%) | 110 (59%) | 279 (69%) | 1300 (80%) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (2%) | 8 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Family history | ||||||

| No | 144 (80%) | 459 (83%) | 139 (75%) | 284 (70%) | 1274 (79%) | |

| Yes | 34 (19%) | 93 (17%) | 47 (25%) | 118 (29%) | 344 (21%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

Q1, 25th percentile

Q3, 75th percentile

Premenopausal Women

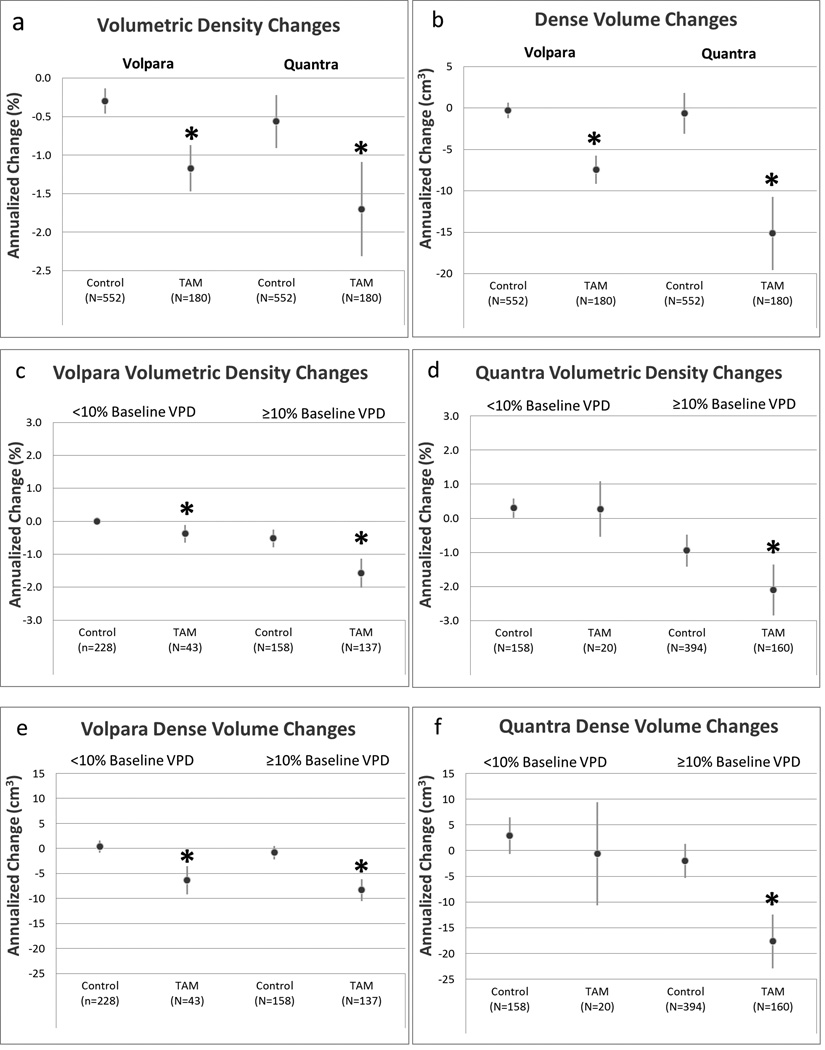

Annualized changes in VPD among premenopausal women on tamoxifen ranged from −10.4% to +5.1% for Volpara and −18.9% to +11.7% for Quantra. Premenopausal women on tamoxifen experienced greater declines in VPD relative to controls, with an adjusted annual declines of 1.17% and 1.70% compared to declines of 0.30% and 0.56% among control women for Volpara (p<0.001) and Quantra (p<0.001), respectively (Supplementary Table 2). Among women with a baseline VPD ≥10%, there were greater reductions in VPD among tamoxifen-users compared to controls for both Volpara (mean: −1.58%, p=<0.001) and Quantra (mean: − 2.11%, p=0.004). However, premenopausal women with Quantra baseline VPD <10% on average did not experience a decline in breast density, while those with Volpara baseline VPD<10% did show a significant decrease of 0.38% compared to controls (p=0.01, Figure 1c,d).

Figure 1.

Changes in Volpara and Quantra volumetric percent density (VPD) and dense breast volume (DV) with tamoxifen (TAM) therapy among premenopausal women.

Panel (a): annualized changes in VPD measured by Volpara and Quantra; panel (b): annualized changes in DV measured by Volpara and Quantra; panel (c): annualized changes in Volpara VPD stratified by baseline Volpara VPD; panel (d): annualized changes in Quantra VPD stratified by baseline Quantra VPD; panel (e): annualized changes in Volpara DV stratified by baseline Volpara VPD; panel (f): annualized changes in Quantra DV stratified by baseline Quantra VPD.

Circles represent estimated annualized changes in breast density; lines represent 95% confidence intervals. All analyses adjusted for age, baseline BMI, change in BMI, natural logarithm of baseline volumetric density, and study site.

TAM, tamoxifen

*p-value <0.05 for annualized change compared to controls

Among premenopausal women, estimates of the effect of treatment on DV overall and by baseline density were generally consistent with VPD. Annualized changes among tamoxifen-users ranged from −70.0 cm3 to +22.0 cm3 for Volpara and −156.9 cm3 to +53.0 cm3 for Quantra. Women on tamoxifen had greater reductions in DV relative to controls, with adjusted declines in Volpara DV of 7.43 cm3 and Quantra DV of 15.13 cm3 compared to reductions of 0.28 cm3 and 0.63 cm3 among controls (Volpara p<0.001; Quantra p<0.001). When stratifying by baseline Volpara VPD, tamoxifen-users with baseline VPD <10% and ≥10% both showed statistically greater declines in DV compared to controls. Women on tamoxifen with <10% baseline Quantra VPD did not experience a decline in DV (p=0.51; Figure 1f, Supplementary Table 3).

Postmenopausal Women

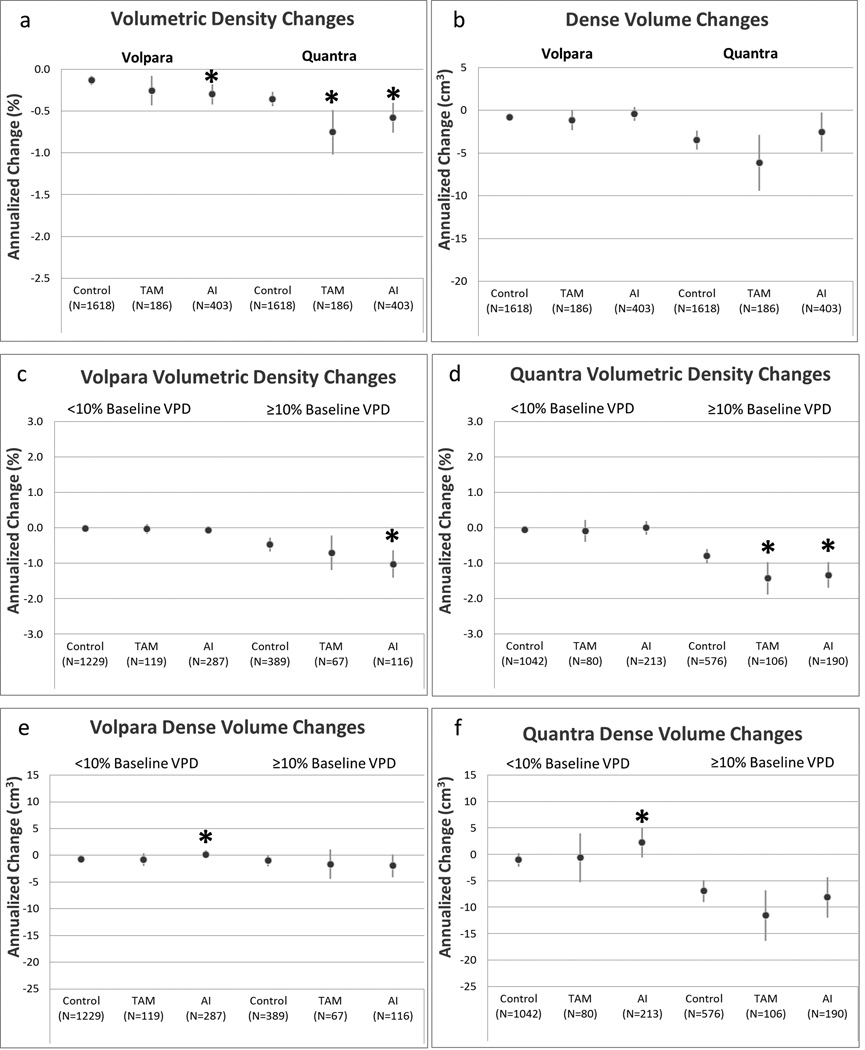

Annualized changes in VPD and DV were, on average, lower among postmenopausal compared with premenopausal cases and controls. Reductions in VPD with tamoxifen ranged from of −5.7% to +5.7% and −7.0% to +6.7%, compared with AI-users range of −7.4% to 3.9% and −7.6% to +11.9% for Volpara and Quantra, respectively. Adjusted annual reductions in VPD were greater for tamoxifen-users (Volpara: −0.26%, Quantra: −0.75%) and AI-users (Volpara: −0.30%, Quantra: −0.58%) relative to controls, though changes with tamoxifen compared with controls were only statistically significant with Quantra (p=0.005). Volpara did not detect differences in VPD with tamoxifen compared with control women in either strata of baseline density, but found greater reductions in VPD among AI-users with baseline VPD ≥10% (p=0.009). In contrast, Quantra found statistically greater declines in VPD for both tamoxifen and AI-users among women with baseline VPD ≥10% compared to controls (tamoxifen p=0.009; AI p=0.006, Figure 2c,d).

Figure 2.

Changes in Volpara and Quantra volumetric percent density (VPD) and dense breast volume (DV) with tamoxifen (TAM) and aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy among postmenopausal women.

Panel (a): annualized changes in VPD measured by Volpara and Quantra; panel (b): annualized changes in DV measured by Volpara and Quantra; panel (c): annualized changes in Volpara VPD stratified by baseline Volpara VPD; panel (d): annualized changes in Quantra VPD stratified by baseline Quantra VPD; panel (e): annualized changes in Volpara DV stratified by baseline Volpara VPD; panel (f): annualized changes in Quantra DV stratified by baseline Quantra VPD.

Circles represent estimated annualized changes in breast density; lines represent 95% confidence intervals. All analyses adjusted for age, baseline BMI, change in BMI, natural logarithm of baseline volumetric density, and study site.

TAM, tamoxifen

AI, aromatase inhibitors

*p-value <0.05 for annualized change compared to controls

Neither software type detected decreases in DV among postmenopausal tamoxifen or AI-users overall, though both Volpara and Quantra detected statistically significant increases in DV among AI-users compared with controls with baseline density <10%, with an increase of 0.14 cm3 and 2.22 cm3 for Volpara (p=0.05) and Quantra (p=0.04), respectively (Supplementary Table 4).

Volpara vs. Quantra

The effect of treatment differed by software type only for estimates of DV among premenopausal women, where Quantra estimated a larger effect of tamoxifen on DV relative to Volpara (p interaction=0.002, Figure 1e,f). The effect of treatment on annualized change of VPD, or DV among postmenopausal women did not differ by software type.

Discussion

Our results suggest that treatment with tamoxifen and AI were associated with decreases in VPD among premenopausal and postmenopausal women. On average, the magnitude of annual decline in VPD with either treatment was greater in premenopausal women and women with higher baseline VPD. Treatment was associated with decreases in DV among premenopausal women, though DV did not decline with tamoxifen or AI among postmenopausal women overall.

Our results using volumetric density measures support previous literature finding greater declines among tamoxifen-users relative to women not treated with tamoxifen. Meggiorini et al. (2008)(2) compared area percent density among breast cancer cases treated with tamoxifen and radiation compared with chemotherapy and radiation, and found a mean reduction of 20.6% in the tamoxifen-treated group compared to 7.5% among those treated without tamoxifen. Two other studies of adjuvant tamoxifen used qualitative parenchymal patterns and found that premenopausal and postmenopausal tamoxifen-users were more likely to decrease their breast density category relative to controls.(29,30) Studies of tamoxifen for primary prevention show similar findings;(31,32) notably, in the International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS), women randomized to tamoxifen reduced percent density by 7.9% after 18 months of treatment, relative to the 3.5% decline among those randomized to placebo, with larger declines observed among premenopausal women.(28) We found average annual declines of 1–2% among premenopausal women, and 0–1% among postmenopausal women. This magnitude of change was broadly consistent with the only other study to use volumetric breast density, measured on MRI, that found a median reduction of 5.8% percent density among premenopausal and postmenopausal women after a mean of 17.5 months.(30)

Our study is the first to find clear evidence of a decline in volumetric breast density among women on AI. Neither of the two prior studies of AI that include a reference comparison found evidence of a greater decline in breast density with AI compared to the natural decline among untreated women.(13,14) Previous studies have exclusively used two-dimensional operator-dependent breast density measures, therefore one explanation of our results may be increased precision in the fully-automated software. Also, prior studies did not exclusively use FFDM images.(13,14) Alternatively, differences in our findings may support the hypothesis that there are different aspects of breast density that are captured by two and three-dimensional measurements. This hypothesis is supported by recent work,(33,34) including Cheddad et al.(33) who found that while area and volumetric measurements were correlated, volumetric density was independently associated with a genetic variant indicative of breast density, after controlling for area density measures, suggesting volume may capture a slightly different underlying entity.

A growing literature suggests that declines in breast density with tamoxifen or AI may be important prognostic indicators of breast cancer outcomes. Changes in breast density with tamoxifen and AI may occur when the estrogen effect is successfully blocked at the tissue level, consistent with other exposures, including menopause, where reduced exposure to estrogen reduces breast density. Li et al.(6) recently found a reduced risk of breast cancer mortality among women on tamoxifen who experienced a ≥20% reduction in dense breast area, while Kim and colleagues(7) found that women on tamoxifen or AI who decreased their area percent density by >10% had a lower risk of recurrence. These results are supported by the IBIS-1 trial, which observed a similar threshold for reduced risk of breast cancer among women taking tamoxifen for primary prevention.(8) However, all of these studies used two-dimensional measurements of breast density; the magnitude of volumetric breast density change relevant for prognostic significance has yet to be examined and must be established to inform clinical decision-making.

Studies of longitudinal change in breast density have observed greater declines among women with higher baseline breast density.(4,8,12,22,28,35) We found that on average women with baseline density ≥10% experience a larger annual decline, though premenopausal women with baseline density <10% still experienced statistically significant reductions in breast density, using either volumetric density measure. It is unclear if the benefit of density reduction on breast cancer outcomes is limited to women with higher baseline density, or simply if women with higher baseline values experience larger reductions. A majority of the literature finding improved prognoses with density decline have been restricted to studies of women with higher baseline density,(4,6,8) though we found density declines even among women with low baseline values. Future research should examine whether these smaller changes are also clinically relevant.

While Volpara and Quantra software estimated similar directions of changes in breast density, the magnitude of the changes differed. Both software types estimate volumetric breast density using the same metric, cm3, but with distinct proprietary algorithms, though previous research shows the measures to be highly correlated.(19) Differences in these algorithms may explain why Quantra results were statistically significant for DV but Volpara estimates were not. The software types were most consistent among premenopausal women, suggesting that the estimates may be most robust among women with high baseline density. Although we found occasional differences in statistical significance between software types, the direction of changes and subsequent inferences were consistent, thus we conclude that both software types are capable of measuring longitudinal change..

Limitations of our study included the inability to determine the exact treatment duration for cases from the SFMR, though we expect that misclassification of treatment duration would be random and non-differential with respect to breast density change (e.g., the proportion of newly treated women will be similar to those who have been treated for the entirety of the prior year). Our analyses were stratified by menopause status at the initial mammogram, though controls that were premenopausal at baseline may have gone through menopause during the time between mammograms. Tamoxifen and AI can induce menopause, therefore we could not restrict to controls remaining premenopausal throughout treatment as they would not be comparable to cancer cases. To address this, we adjusted for age and other determinants of density decline, and expect that the control group approximates the average natural decline that would have been observed in the cases had they not been treated. Finally, we modeled annualized changes, which assumes linear change with treatment duration. Our results suggested a linear fit was appropriate, though prior studies have found nonlinear declines in density,(3,12,28) and our power to detect non-linear changes was limited by low average number of visits.

Our study is one of the largest to examine longitudinal changes in breast density among breast cancer cases on tamoxifen or AI, and the first to utilize automated, volumetric breast density measures on FFDM. Our study benefits from a large number of treated women with serial mammograms, and the comparison of annualized changes to declines among untreated women.

In summary, we found that automated volumetric breast density measures can be used to detect volumetric density changes among women on tamoxifen and AI, with greater declines in volumetric breast density among premenopausal women using tamoxifen, and postmenopausal women using AI, compared to control women. Future research should examine whether change in volumetric breast density, and what magnitude of change, is predictive of breast cancer outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.S. Author receives research funding from Hologic.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant (R01CA177150-03, PI’s: C.M. Vachon, K. Kerlikowske), as well as the Mayo Clinic Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Breast Cancer (P50 CA116201; PI’s: M. Goetz and J. Ingle), and the National Cancer Institute funded Program Project (P01CA154292; PI: K. Kerlikowske), which supported the collection of digital images.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The remaining authors have no relationships to disclose.

Prior Presentations: Preliminary results from this study were presented at the American Association of Cancer Research Annual Meeting in April 2016 in New Orleans, LA.

References

- 1.Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: Patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. Elsevier Ltd. 2011;378:771–784. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meggiorini ML, Labi L, Vestri AR, Porfiri LM, Savelli S, De Felice C. Tamoxifen in women with breast cancer and mammographic density. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2008;29:598–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nyante SJ, Sherman ME, Pfeiffer RM, de Gonzalez AB, Brinton LA, Bowles EJA, et al. Longitudinal Change in Mammographic Density among ER-Positive Breast Cancer Patients Using Tamoxifen. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:212–216. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nyante SJ, Sherman ME, Pfeiffer RM, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Brinton LA, Aiello Bowles EJ, et al. Prognostic Significance of Mammographic Density Change after Initiation of Tamoxifen for ER-Positive Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko K, Shin I, You J, Jung S-Y, Ro J, Lee ES. Adjuvant tamoxifen-induced mammographic breast density reduction as a predictor for recurrence in estrogen receptor-positive premenopausal breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;142:559–567. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, Humphreys K, Eriksson L, Edgren G, Czene K, Hall P. Mammographic density reduction is a prognostic marker of response to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2249–2256. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim J, Wonshik H, Hyeong-Gon M, Ahn SK, Shin H-C, You J-M, et al. Breast density change as a predictive surrogate for response to adjuvant endocrine therapy in hormone receptor positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14 doi: 10.1186/bcr3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuzick J, Warwick J, Pinney E, Duffy SW, Cawthorn S, Howell A, et al. Tamoxifen-induced reduction in mammographic density and breast cancer risk reduction: a nested case-control study. JNCI. 2011;103:744–752. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geisler J, Haynes B, Anker G, Dowsett M, Lønning PE. Influence of letrozole and anastrozole on total body aromatization and plasma estrogen levels in postmenopausal breast cancer patients evaluated in a randomized, cross-over study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:751–757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller WR, Dixon JM. Local endocrine effects of aromatase inhibitors within the breast. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;79:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prowell TM, Blackford A, Byrne C, Khouri NF, Dowsett M, Folkerd E, et al. Changes in breast density and circulating estrogens in postmenopausal women receiving adjuvant anastrozole. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:1993–2001. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry NL, Chan H, Dantzer J, Goswami CP, Li L, Skaar TC, et al. Aromatase inhibitor-induced modulation of breast density: clinical and genetic effects. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2331–2339. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vachon CM, Ingle J, Suman VJ, Scott CG, Gottardt H, Olson JE, et al. Pilot study of the impact of letrozole vs. placebo on breast density in women completing 5 years of tamoxifen. The Breast. 2007;16:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vachon CM, Suman VJ, Brandt KR, Kosel ML, Buzdar AU, Olson JE, et al. Mammographic breast density response to aromatase inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2144–2153. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabian CJ, Kimler B, Zalles CM, Khan QJ, Mayo MS, Phillips TA, et al. Reduction in proliferation with six months of letrozole in women on hormone replacement therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106:75–84. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cigler T, Tu D, Yaffe MJ, Findlay B, Verma S, Johnston D, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial (NCIC CTG MAP1) examining the effects of letrozole on mammographic breast density and other end organs in postmenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;120:427–435. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0662-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cigler T, Richardson H, Yaffe MJ, Fabian CJ, Johnston D, Ingle JN, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial (NCIC CTG MAP.2) examining the effects of exemestane on mammographic breast density, bone density, markers of bone metabolism and serum lipid levels in postmenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:453–461. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mousa N, Crystal P, Wolfman WL, Bedaiwy MA, Casper RF. Aromatase inhibitors and mammographic breast density in postmenopausal women receiving hormone therapy. Menopause. 2008;15:875–884. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31816956c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brandt KR, Scott CG, Ma L, Mahmoudzadeh AP, Jensen MR, Whaley DH, et al. Comparison of Clinical and Automated Breast Density Measurements: Implications for Risk Prediction and Supplemental Screening. Radiology. 2015;279:710–719. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eng A, Gallant Z, Shepherd J, McCormack V, Li J, Dowsett M, et al. Digital mammographic density and breast cancer risk: a case-control study of six alternative density assessment methods. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:439. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0439-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sovio U, Li J, Aitken Z, Humphreys K, Czene K, Moss S, et al. Comparison of fully and semi-automated area-based methods for measuring mammographic density and predicting breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2014:1–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen JH, Chang YC, Chang D, Wang YT, Nie K, Chang RF, et al. Magn Reson Imaging. Vol. 29. Elsevier Inc; 2011. Reduction of breast density following tamoxifen treatment evaluated by 3-D MRI: Preliminary study; pp. 91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, Cho N, Jeyanth J, Kim WH, Lee SH, Gweon HM, et al. Smaller reduction in 3D breast density associated with subsequent cancer recurrence in patients with breast cancer receiving adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:912–921. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VolparaSolutions. Volpara Breast Density Brochure [Internet] [cited 2016 Mar 21]; Available from: http://volparasolutions.com/Dejavu/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Volpara-Density-LETTER-Feb2015_single-page2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hologic. Understanding Quantra 2.0 User Manual - MAN-02004 Rev 002. Bedford, MA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olson JE, Sellers TA, Scott CG, Schueler BA, Brandt KR, Serie DJ, et al. The influence of mammogram acquisition on the mammographic density and breast cancer association in the Mayo Mammography Health Study cohort. Breast cancer Res. 2012;14:R147. doi: 10.1186/bcr3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Highnam R, Brady S, Yaffe M, Karssemeijer N, Harvey J. 5th Int Work Breast Densitom Breast Cancer Risk Assess. San Francisco, CA: 2011. Robust breast composition measurement - VolparaTM. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuzick J, Warwick J, Pinney E, Warren RML, Duffy SW. Tamoxifen and breast density in women at increased risk of breast cancer. JNCI. 2004;96:621–628. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atkinson C, Warren R, Bingham SA, Day N. Mammographic patterns as a predictive biomarker of breast cancer risk: effect of tamoxifen. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Son HJ, Oh KK. Significance of follow-up mammography in estimating the effect of tamoxifen in breast cancer patients who have undergone surgery. Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173 doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.4.10511146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chow CK, Venzon D, Jones EC, Premkumar A, O’Shaughnessy J, Zujewski J. Effect of tamoxifen on mammographic density. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;9:917–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brisson J, Brisson B, Cote G, Maunsell E, Berube S, Robert J. Tamoxifen and mammographic breast densities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:911–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheddad A, Czene K, Eriksson M, Li J, Easton D, Hall P, et al. Area and volumetric density estimation in processed full-field digital mammograms for risk assessment of breast cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brand JS, Czene K, Shepherd JA, Leifland K, Heddson B, Sundbom A, et al. Automated measurement of volumetric mammographic density: A tool for widespread breast cancer risk assessment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1764–1772. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maskarinec G, Pagano I, Lurie G, Kolonel LN. A longitudinal investigation of mammographic density: the multiethnic cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:732–739. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.