Abstract

Background

Long-term safety of assisted reproductive techniques (ART) is of interest as use is increasing. Cancer risk is known to be affected by parity. This study examined risk of cancer after fertility treatment, stratified by women’s parity.

Methods

Data was obtained on all women (n=1 353 724) born in Norway between 1960–1996. Drug exposure data (2004–2014) was obtained from the Norwegian Prescription Database [drugs used in ART and clomiphene citrate (CC)]. The Medical Birth Registry of Norway provided parity status. Hazard ratios were calculated for all site cancer, breast, cervical, endometrial, ovarian, colorectal, central nervous system, thyroid cancer and malignant melanoma.

Results

In 12 354 392 person-years of follow-up, 20 128 women were diagnosed with cancer. All-site cancer risk was (1.14, 1.03–1.26) and (1.10, 0.98–1.23) following CC and ART exposure respectively. For ovarian cancer, a stronger association was observed for both exposures in nulliparous (HR 2.49, 1.30–4.78, and HR 1.62, 0.78–3.35) versus parous women (HR 1.37, 0.64–2.96, and HR 0.87, 0.33–2.27).

Elevated risk of endometrial cancers was observed for CC exposure in nulliparous women (4.59, 2.68–7.84 vs. 1.44, 0.63–3.31). Risk was elevated for breast cancer in parous women exposed to CC (1.26, 1.03–1.54) and among nulliparous women after ART treatment (2.19, 1.08–4.44).

Conclusion

CC appears associated with increased risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer. Elevations in risks of breast and thyroid cancer were less consistent across type of drug exposure and parity.

Impact

Continued monitoring of fertility treatments is warranted.

Keywords: Fertility drugs, pharmacoepidemiology, ART, IVF, cancer

Introduction

Pregnancy is known to protect against ovarian (1), breast(2) and endometrial(3) cancers, and nulliparity is consequently an established risk factor for these cancers. Furthermore, some studies have suggested that older ages at first birth may relate to increased risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM)(4) and increasing parity to an elevated risk of thyroid cancer (5).

A continuing expansion of the use of assisted reproductive techniques (ART) means that growing numbers of women are exposed to a variety of fertility drugs (6), and monitoring the safety of these relatively new drugs is of importance. Some studies have found associations between fertility drug use and risks of ovarian (7, 8) breast (9–11) and other cancers (12, 13), whilst others have not (14–17), including two meta-analyses (18, 19). With reproductive factors being modifiers of cancer risk at several sites, a question that remains is whether effects of fertility drugs are different among nulliparous and parous women. Only a limited number of studies have been able to perform analyses stratified by parity (8, 20, 21), and even fewer are able to look separately at risks in women who remain nulliparous after treatment (22).

We previously examined cancer risk associated with ART in parous women in Norway and found elevated risks of breast (11) and central nervous system cancers (23). We attempted in the present study to expand on our previous studies by examining risks in both parous and nulliparous women, and by analyzing exposure to both ART and clomiphene citrate. The novelty of this study is that we are able to present results for nulliparous women alone, to assess whether these women harbor an especially high risk of cancer that parous women.

The aim of the study was to compare cancer risk in nulliparous women exposed to fertility drugs to nulliparous women not treated with fertility drugs. By using data from four nationwide registries we were able to establish a nation-wide cohort of considerable size. For comparison, analyses on parous women were also included. The study assessed all-site cancer risk, and the risk of breast, cervical, endometrial, ovarian, colorectal (CRC), central nervous system (CNS) thyroid cancers and cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM).

Materials and Methods

Data sources and study population

This population-based study includes all women born in Norway between 1960 and 1996 registered in the National Registry. Additional nation-wide registries provided data on dispensed fertility drugs [the Norwegian Prescription Database], pregnancies and births [the Medical Birth Registry of Norway], and cancer diagnoses [the Cancer Registry of Norway]. Since 2004, the Norwegian Prescription Database has included data on all prescribed drugs dispensed to individuals in ambulatory care (24). Drugs are classified according to the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification (25). The Medical Birth Registry of Norway was established in 1967 and contains information on all births in Norway, and is based on compulsory notification of every birth, from 16 completed weeks of gestation onwards (26). The Cancer Registry of Norway was established in 1952, and contains information on all persons diagnosed with cancer since 1953 (27). A unique personal identity number (PID) is assigned to each resident at birth or immigration, enabling data linkage across the registries. Reporting to the registries is mandatory and regulated by national laws.

Ascertainment of exposure of fertility drugs

Exposure to ART: Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) is the process of using drugs to obtain several mature oocytes in a single menstrual cycle for use in in vitro fertilization (IVF). Hormone protocols used for COH in ART vary widely, but mostly the standard protocols include the following three medications: Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues (agonists or antagonists), gonadotropins (Follicle stimulating hormone or human menopausal gonadotropin) and finally human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (28). Study subjects were considered as exposed to an ART treatment either when they had been prescribed either a combination of all three medications, or only the first two (GnRH analogues and other gonadotropins) within a two-month time period. Number of cycles of ART were categorized: 1, 2 and 3 or more ART cycles.

Exposure to clomiphene citrate (CC)

Clomiphene citrate is a nonsteroidal ovarian stimulant used for ovulation induction since the 1960s. It binds to hypothalamic estrogen receptors and by negative feedback induces pulsatile GnRH secretion, increased gonadotrophin secretion and increased ovarian follicular activity (29). All women with at least one prescription of CC were considered as exposed to CC, all others were denoted non-CC women. Each treatment cycle consists of 50 mg for 5 consecutive days, and dose was categorized as ≤ 3 cycles, 3–6 cycles or < 6 cycles.

The drugs and ATC codes included in the analyses are displayed in Supplementary Table 1.

Cancer diagnoses

Cancers diagnosed were categorized according to the International Classification of Diseases version 10 (ICD-10), (C00–96, up to 12 per individual).

Analyses of all-site cancer risk considered the first cancer (at any site) and in site-specific analyses, the first case of the cancer of interest was used. Women diagnosed with a cancer before 2004 were excluded from the analyses.

Analyses were conducted for the same sites as in our previous studies on parous women, namely breast (C50), cervical (invasive cancers only) (C53), endometrial (C54–55), ovarian (C56), colorectal (C18–20) CNS (C70–72) thyroid cancers (C73) and CMM (C43). Separate analyses were made for ovarian cancer subgroups, and for borderline ovarian tumors (see supplementary file for histology codes).

Potential confounding factors

We adjusted for region of residence because there may be regional differences in both use of fertility treatment and cancer incidence. We adjusted for birth year to account for potential cohort effects on cancer incidence. In the analyses of all women, adjustment was made for parity by splitting the data at the date of each woman’s first birth. When assessing ART exposure, adjustments were made for CC exposure (ever/never), and vice versa.

Follow-up

Follow-up started on January 1 2004 for all women born between 1960 and 1985. Women who were born in 1986 or later, started follow-up on turning 18 years because receiving fertility treatment before this age was deemed unlikely. Women born before 1960 were not included as it was considered likely that they would be too old for fertility treatment during in the observational period 2004 to 2014. Follow-up ended upon diagnosis of the first cancer of interest, death, emigration or December 31 2014 (the latest update of the Cancer Registry of Norway).

Statistical analyses

We used Cox regression models to compute hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for cancer risk in exposed versus unexposed women. Separate analyses were made for ART and CC exposure, and for parous and nulliparous women. Age was used as the timescale (30). Parity was treated as a time-dependent variable, with women switching classification from nulliparous to parous at the time of the first birth.

Analyses were stratified by doses of ART and CC, with dose as a time-varying covariate.(31) Stratified analyses were also made on age at follow-up (below and above 30 years), and age at inclusion (below and above 40 years). Sensitivity analyses were made excluding those receiving other hormones (such as progesterone, or monotherapy with GnRH analogues). Risk of all-site cancer was made after omitting any cancer sites with elevated risks. Testing for heterogeneity was done using a likelihood-ratio test to test any observed differences between groups (p-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant). We attempted to analyze risk according to time since diagnosis to assess potential surveillance bias.

The proportional hazards assumption was tested using the Schoenfeld residuals (32). Analyses were made using the STATA software package, version 14.0, and the STROBE guidelines for reporting observational studies were adhered to (33).

Ethics

The Regional Ethics Committee of the South Eastern Health Region and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate approved the study.

Results

Cohort

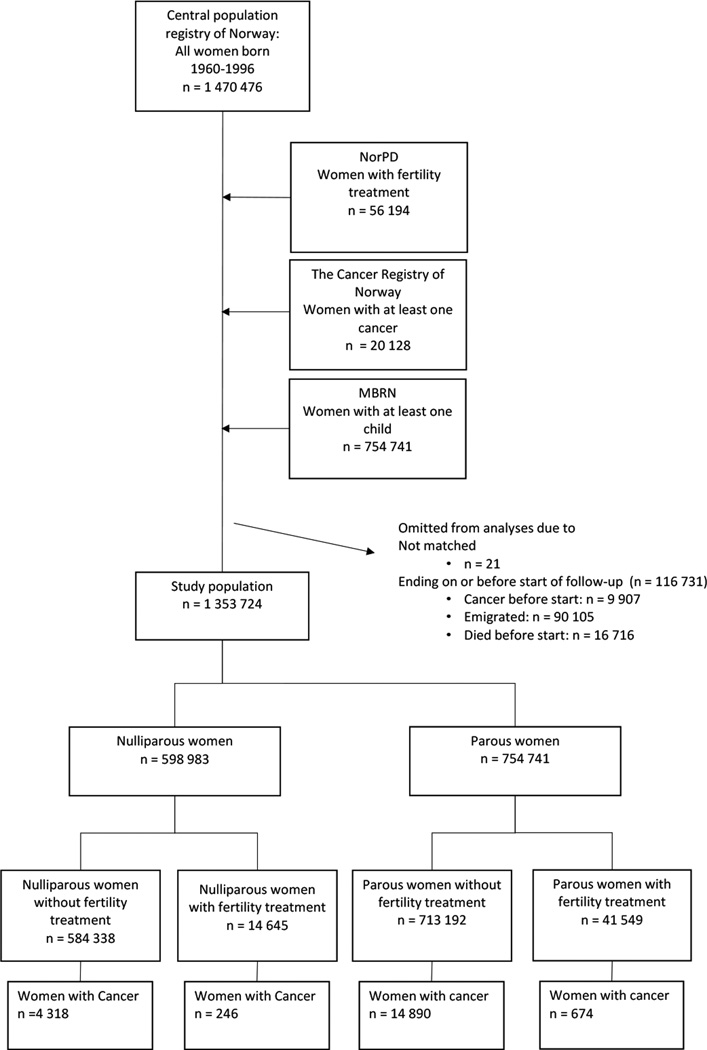

In the National Registry 1 470 476 women were registered as born between 1960 and 1996, of which 1 353 724 (92%) women were eligible for study (figure 1).

Figure 1. Establishment of the study cohort.

NR = National Registry, NorPD = Norwegian Prescription Database, MBRN = The Medical Birth Registry of Norway.

The total follow-up time was 12 354 392 person-years, median 11 years (table 1). Apart from region of residence (485 , <0.1% missing), no other variables had any missing values. A total of 598 983 (44%) women were classified as nulliparous, of which 14 645 (2.4%) had received fertility treatment. The corresponding number of parous women with fertility treatment was 41 549 (5.5%, figure 1). Of those receiving fertility drugs, 33 431 received treatment with ART and 38 927 with CC.

Table 1.

Demographic data of study subjects registered in the Norwegian Prescription Database as having been prescribed and dispensed any fertility drug between January 1 2004 and December 31 2014.

| Nulliparous women* | Parous women** | Total cohort | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No fertility treatment | Any fertility treatment | No fertility treatment | Any fertility treatment | |||||||

| Total number of persons | 584 338 | 14 645 | 713 192 | 41 549 | 1 353 724 | |||||

| Persons with cancer during follow-up (n) | 4 318 | 246 | 14 890 | 674 | 20 128 | |||||

| Age at entry, years(median, IQR) | 18 (18–24) | 27 (21–33) | 31(24–37) | 28(23–32) | 31(24–37) | |||||

| Age at exit, years (median, IQR) | 27(22–34) | 38(32–43) | 42(35–48) | 39(34–43) | 42(35–48) | |||||

| Age at IVF start (median, IQR) | - | 35(31–38) | - | 33(30–36) | - | |||||

| Age at CC start (median, IQR) | - | 33(28–38) | - | 31 (28–36) | - | |||||

| Age at cancer diagnosis (median, range) | 40 (18–55) | 37 (19–52) | 43 (18–55) | 38 (18–53) | 43 (18–55) | |||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Birth year | ||||||||||

| 1960–1969 | 65 591 | (11) | 2 757 | (19) | 278 876 | (39) | 6 214 | (15) | 353 438 | (26) |

| 1970–1979 | 83 287 | (14) | 6 508 | (44) | 255 396 | (36) | 23 498 | (57) | 368 689 | (27) |

| 1980–1989 | 209 148 | (36) | 4 927 | (34) | 160 399 | (22) | 11 548 | (28) | 386 022 | (29) |

| 1990–1996 | 226 312 | (39) | 453 | (3) | 18 521 | (3) | 289 | (1) | 245 575 | (18) |

| Total | 584 338 | (100) | 14645 | (100) | 713 192 | (100) | 41 549 | (100) | 1 353 724 | (100) |

| Region of present residence | ||||||||||

| South East | 185 935 | (32) | 5 368 | (37) | 279 331 | (39) | 15 825 | (38) | 486 459 | (36) |

| Oslo | 132 427 | (23) | 3 254 | (22) | 75 416 | (11) | 5 983 | (14) | 217 080 | (16) |

| South | 80 240 | (14) | 2 029 | (14) | 108 130 | (15) | 7 171 | (17) | 197 570 | (15) |

| West | 92 423 | (16) | 2 094 | (14) | 119 304 | (17) | 6 741 | (16) | 220 562 | (16) |

| Middle | 46 753 | (8) | 866 | (6) | 63 513 | (9) | 3 049 | (7) | 114 181 | (8) |

| North | 46 338 | (8) | 1 025 | (7) | 67 257 | (9) | 2 767 | (7) | 117 387 | (9) |

| Missing or unknown | 222 | (0) | 9 | (0) | 241 | (0) | 13 | (0) | 485 | (0) |

| Total | 584 338 | (100) | 14 645 | (100) | 713 192 | (100) | 41 549 | (100) | 1 353 724 | (100) |

| Number of children, at entry | ||||||||||

| None | - | - | 674 834 | (95) | 39 719 | (96) | 714 553 | (95) | ||

| One | - | - | 25 883 | (4) | 1 347 | (3) | 27 230 | (4) | ||

| Two | - | - | 7 728 | (1) | 320 | (1) | 8 048 | (1) | ||

| Three or more | - | - | 4 747 | (1) | 163 | (0) | 4 910 | (1) | ||

| Missing | - | - | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ||

| Age at start of follow-up | 713 192 | (100) | 41 549 | (100) | 754 741 | (100) | ||||

| Below 25 | 446 658 | (76) | 6 036 | (41) | 201 364 | (28) | 14 169 | (34) | 668 227 | (49) |

| 25–29 | 43 266 | (7) | 3 265 | (22) | 120 958 | (17) | 12 535 | (30) | 180 024 | (13) |

| 30–35 | 35 891 | (6) | 3 113 | (21) | 141 408 | (20) | 10 234 | (25) | 190 646 | (14) |

| More than 35 | 58 523 | (10) | 2 231 | (15) | 249 462 | (35) | 4 611 | (11) | 314 827 | (23) |

| Missing | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) |

| Total | 584 338 | (100) | 14 645 | (100) | 713 192 | (100) | 41 549 | (100) | 1 353 724 | (100) |

| Age at first cancer | ||||||||||

| Below 30 | 1 043 | (24) | 41 | (17) | 990 | (7) | 84 | (12) | 2 158 | (11) |

| 30–39 | 1 068 | (25) | 123 | (50) | 3 897 | (26) | 339 | (50) | 5 427 | (27) |

| 40–49 | 1 757 | (41) | 76 | (31) | 8 066 | (54) | 240 | (36) | 10 139 | (50) |

| More than 50 | 450 | (10) | 6 | (2) | 1 937 | (13) | 11 | (2) | 2 404 | (12) |

| Missing | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) |

| Total | 4 318 | (100) | 246 | (100) | 14 890 | (100) | 674 | (100) | 20 128 | (100) |

| Types of treatment | ||||||||||

| Any fertility drug | 14 645 | (92) | 41 549 | (90) | 56 194 | (90) | ||||

| Only ART | - | 5 032 | (31) | - | 12 235 | (26) | 17 267 | (28) | ||

| Only Clomiphene citrate | - | 6 012 | (38) | - | 18 507 | (40) | 24 519 | (39) | ||

| Both | - | 3 601 | (23) | - | 10 807 | (23) | 14 408 | (23) | ||

| Ever ART | - | 8 633 | (54) | - | 23 042 | (50) | 31 675 | (51) | ||

| Ever CC | - | 9 613 | (60) | - | 29 314 | (63) | 38 927 | (62) | ||

| Other medications*** | - | 1 347 | (8) | - | 4 848 | (10) | 6 195 | (10) | ||

| Any treatment in the NorPD | - | 15 992 | (100) | - | 46 397 | (100) | 62 389 | (100) | ||

| Number of cycles of ART | ||||||||||

| One | - | 3 372 | (39) | - | 9 716 | (42) | 13 088 | 41% | ||

| Two | - | 2 097 | (24) | - | 5 957 | (26) | 8 054 | 25% | ||

| Three | - | 1 600 | (19) | - | 3 634 | (16) | 5 234 | 17% | ||

| Four | - | 762 | (9) | - | 1 877 | (8) | 2 639 | 8% | ||

| Five | - | 418 | (5) | - | 911 | (4) | 1 329 | 4% | ||

| Six or more | - | 384 | (4) | - | 947 | (4) | 1 331 | 4% | ||

| Total | - | 8 633 | (100) | - | 23 042 | (100) | 31 675 | 100% | ||

| Dose of Clomiphene citrate | ||||||||||

| Up to 84 mg | - | 7 955 | (83) | - | 24 639 | (84) | 32 594 | (84) | ||

| 84 – 168 mg | - | 1 441 | (15) | - | 4 048 | (14) | 5 489 | (14) | ||

| Above 168 mg | - | 217 | (2) | - | 627 | (2) | 844 | (2) | ||

| Total | - | 9 613 | (100) | - | 29 314 | (100) | 38 927 | (100) | ||

This column includes all women who gave birth by the end of follow-up, that is women who remain childless throughout the study period. Some women may have been nulliparous, but have had children after some years of nulliparity, and therefore end up in the right column.

This column includes all women who gave birth by the end of follow-up, ie they may have been nulliparous at the start

Such as GnRH monotherapy or progesterone only.

Median age at entry was 27 years for nulliparous women with fertility treatment, and 18 years for nulliparous women without (table 1). Nulliparous women with cancer were younger at diagnosis (median 40 years and 37 years for those without and with fertility treatment respectively) compared to parous women (median 43 and 38 years).

Of the total cohort, 20 128 women were registered with at least one cancer diagnosis, with 920 (4.6%) of these occurring in exposed women (table 1).

Exposure to ART

The risk of all-site cancer in ART exposed compared to unexposed women was 1.10 (95% CI 0.98, 1.23). For nulliparous women the HR was 1.00 (95% CI 0.81, 1.24), compared to 1.14 (95% CI 1.00, 1.29) among parous women (table 2).

Table 2.

Hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of cancer in women receiving assisted reproductive technology (ART) as registered in the Norwegian Prescription Database compared with women not receiving ART.

| Cancer site | ICD 10 Code |

ART women |

Unexposed | HR* | 95% CI | p- value** |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Cases | ||||||

| All-site Cancer | C00–99 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 108 | 5 159 | 1.00 | 0.81 | 1.24 | ||

| Parous | 277 | 14 584 | 1.14 | 1.00 | 1.29 | ||

| All women*** | 385 | 19 743 | 1.10 | 0.98 | 1.23 | 0.5 | |

| Breast Cancer | C50 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 29 | 1 262 | 1.11 | 0.75 | 1.66 | ||

| Parous | 83 | 5 316 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 1.22 | ||

| Total | 112 | 6 578 | 1.00 | 0.81 | 1.22 | 0.6 | |

| Cervical Cancer | C53 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 8 | 466 | 0.78 | 0.37 | 1.67 | ||

| Parous | 24 | 1 331 | 0.95 | 0.62 | 1.46 | ||

| All women | 32 | 1 797 | 0.91 | 0.62 | 1.32 | 0.8 | |

| Endometrial Cancer | C54–55 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 5 | 224 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 1.03 | ||

| Parous | 7 | 341 | 1.62 | 0.70 | 3.85 | ||

| All women | 12 | 565 | 0.76 | 0.40 | 1.45 | 0.4 | |

| Ovarian Cancer | C56 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 11 | 222 | 1.62 | 0.78 | 3.35 | ||

| Parous | 5 | 393 | 0.87 | 0.33 | 2.27 | ||

| All women | 16 | 615 | 1.29 | 0.73 | 2.28 | 0.05 | |

| Borderline ovarian tumors | N/A | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 12 | 245 | 1.69 | 0.75 | 3.79 | ||

| Parous | 8 | 374 | 2.12 | 1.11 | 4.04 | ||

| All women | 20 | 619 | 1.95 | 1.18 | 3.23 | 0.9 | |

| Colorectal Cancer | C18–20 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 3 | 263 | 0.63 | 0.19 | 2.10 | ||

| Parous | 12 | 874 | 0.88 | 0.47 | 1.63 | ||

| All women | 15 | 1137 | 0.81 | 0.47 | 1.41 | 0.5 | |

| Central nervous system | C70–72 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 4 | 424 | 0.43 | 0.15 | 1.23 | ||

| Parous | 22 | 1072 | 1.25 | 0.79 | 2.00 | ||

| All women | 26 | 1 496 | 0.99 | 0.65 | 1.51 | 0.1 | |

| Thyroid cancer | C73 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 10 | 286 | 2.19 | 1.08 | 4.44 | ||

| Parous | 19 | 622 | 1.31 | 0.78 | 2.19 | ||

| All women | 29 | 908 | 1.53 | 1.01 | 2.31 | 0.6 | |

| Malignant Melanoma | C43 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 10 | 543 | 0.77 | 0.39 | 1.54 | ||

| Parous | 30 | 1 717 | 1.06 | 0.72 | 1.54 | ||

| All women | 42 | 2 260 | 0.97 | 0.70 | 1.36 | 0.8 | |

Adjusted for region of residence, birth cohort and concomitant exposure to clomiphene citrate.

Test for heterogeneity between parous and nulliparous women

Adjustments for parity are made in the analyses of all women together.

ART was not associated with an elevated risk of breast cancer, either in nulliparous (1.11 (95% CI 0.75, 1.66)) nor parous women (0.96 (95% CI 0.76, 1.22)).

ART-women (both parous and nulliparous) appeared to have a lower risk of cervical cancer although neither risk was statistically significant. Risk of endometrial cancer was slightly but not statistically significantly elevated in parous women exposed to ART (1.62 (95% CI 0.70, 3.85)). No elevation was observed among nulliparous women (0.39 (95% CI 0.15, 1.03)).

Women exposed to ART did not have a significantly elevated risk of ovarian cancer, (1.29,95% CI 0.73, 2.28) compared to unexposed. For nulliparous women risk was slightly higher, although not statistically significant, (1.62 (95% CI 0.78, 3.35)). For parous women alone, no risk elevation was observed (0.87 (95% CI 0.33, 2.27)). A p-value of 0.05 indicates a borderline-significant difference in risk between nulliparous and parous women for ART and ovarian cancer.

Risk of borderline ovarian tumors was elevated for all ART exposed women, (1.95 (95% CI 1.18, 3.23)). The stratified analyses on parity, showed that there was no significant difference in risk between nulliparous (1.69 (95% CI 0.75, 3.79)) and parous women (2.12 (95% CI 1.11, 4.04))(p= 0.9). No differences in risk were observed with increasing number of cycles of ART (supplementary table 2).

The risk of thyroid cancer was elevated for all women exposed to ART compared to non-ART women (1.53 (95% CI 1.01, 2.31)), with significant risks in nulliparous women (2.19 (95% CI 1.08, 4.44)) and non-significant risk in parous women (1.31 (95% CI 0.78, 2.19)).

ART treatment was not associated with elevated risk of CRC, CNS tumors or CMM in exposed women, regardless of parity and dose (supplementary table 2).

Exposure to Clomiphene Citrate

CC exposure was associated with an elevated risk of all-site cancer, (1.14 (95% CI 1.03, 1.26)), and the risk estimates were similar for parous and nulliparous women (table 3).

Table 3.

Hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of cancer in women receiving Clomiphene Citrate (CC), as registered in the Norwegian Prescription Database, compared with women not receiving CC.

| Cancer site | ICD 10 Code |

CC women | Unexposed | HR* | 95%CI | p- value** |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Cases | ||||||

| All-site cancer | C00–99 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 130 | 5 137 | 1.21 | 0.99 | 1.46 | ||

| Parous | 334 | 14 527 | 1.11 | 0.98 | 1.25 | ||

| All women*** | 464 | 19 664 | 1.14 | 1.03 | 1.26 | 0.09 | |

| Breast Cancer | C50 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 24 | 1 267 | 0.73 | 0.47 | 1.12 | ||

| Parous | 116 | 5 283 | 1.26 | 1.03 | 1.54 | ||

| All women | 140 | 6 550 | 1.12 | 0.93 | 1.35 | 0.02 | |

| Cervical Cancer | C53 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 11 | 463 | 1.12 | 0.59 | 2.14 | ||

| Parous | 26 | 1 329 | 0.74 | 0.49 | 1.13 | ||

| All women | 37 | 1 792 | 0.83 | 0.62 | 1.18 | 0.4 | |

| Endometrial Cancer | C54–55 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 18 | 211 | 4.49 | 2.66 | 7.60 | ||

| Parous | 8 | 340 | 1.52 | 0.67 | 3.42 | ||

| All women | 26 | 551 | 2.91 | 1.87 | 4.53 | 0.06 | |

| Ovarian Cancer | C56 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 14 | 219 | 2.49 | 1.30 | 4.78 | ||

| Parous | 8 | 390 | 1.37 | 0.64 | 2.96 | ||

| All women | 22 | 609 | 1.93 | 1.18 | 3.16 | 0.04 | |

| Borderline ovarian tumors | N/A | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 7 | 246 | 1.16 | 0.49 | 2.73 | ||

| Parous | 9 | 377 | 0.87 | 0.41 | 1.82 | ||

| All women | 16 | 623 | 0.97 | 0.56 | 1.70 | 0.6 | |

| Colorectal Cancer | C18–20 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 4 | 262 | 0.83 | 0.29 | 2.37 | ||

| Parous | 18 | 868 | 1.20 | 0.72 | 2.00 | ||

| All women | 22 | 1130 | 1.12 | 0.71 | 1.76 | 0.4 | |

| Central nervous system | C70–72 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 10 | 418 | 1.63 | 0.83 | 3.17 | ||

| Parous | 23 | 1 071 | 0.93 | 0.59 | 1.46 | ||

| All women | 33 | 1 489 | 1.10 | 0.75 | 1.60 | 0.5 | |

| Thyroid cancer | C73 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 6 | 290 | 0.68 | 0.28 | 1.68 | ||

| Parous | 25 | 616 | 1.47 | 0.93 | 2.31 | ||

| All women | 31 | 906 | 1.24 | 0.82 | 1.85 | 0.3 | |

| Malignant Melanoma | C43 | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 17 | 536 | 1.71 | 1.01 | 2.92 | ||

| Parous | 35 | 1 714 | 0.90 | 0.63 | 1.30 | ||

| All women | 53 | 2 250 | 1.06 | 0.79 | 1.43 | 0.1 | |

Adjusted for region of residence, birth cohort and concomitant exposure to clomiphene citrate.

Test for heterogeneity between parous and nulliparous women

Adjustments for parity are made in the analyses of all women together.

CC exposure was associated with increased risk of breast cancer, in parous women (1.26 (95% CI 1.03, 1.54)) (p = 0.02), but no dose response relationship for CC and breast cancer (supplementary table 3).

For CC exposed women the risk of cervical cancer was the same as in unexposed women, although slightly but not statistically significantly lower in the parous group (0.83 (95% CI 0.62, 1.18)).

The risk of endometrial cancer was elevated in women treated with CC, (2.91 (95% CI 1.87, 4.53) and risk was highest for nulliparous women (4.49 (95% CI 2.66, 7.60), (p = 0.04), table 3), and among parous women with more than 6 cycles, (4.68 (95% CI 1.74, 12.6)), p-value for trend analysis was 0.011.

CC exposed nulliparous women had increased risk of ovarian cancer (2.49 (95% CI 1.30, 4.78)), while risk was not increased in parous women (1.37 (95% CI 0.64, 2.96) (p = 0.04), table 3). The magnitude of the HRs appeared to increase with increasing doses of CC, 1.76 (95% CI 0.68, 4.58) at the lowest dose, vs 3.46 (95% CI 1.19, 10.0) with the highest dose, although a test for trend revealed a p-value of 0.269.

CC exposure was not associated with risk of borderline tumors, thyroid cancers, CRC, CNS tumors or CMM.

Secondary analyses

When stratifying on different histologic subtypes of ovarian cancer, CC exposure was associated with risk of endometrioid ovarian cancers (4.75 (95 % CI 1.95, 11.6); data not shown). No differences were seen for risk of neither serous nor mucinous tumors (data not shown). When stratifying on age above and below 30 and 40 years at start of follow-up, no differences were observed for ovarian, breast or endometrial cancer. When looking at time since diagnosis, no differences could be seen due to few cases of cancers in the exposed group (data not shown). When removing ovarian and thyroid cancers, from analyses of ART, the estimate for all site cancer was unchanged (1.08 95 % CI 0.96, 1.21)). Neither did removing ovarian and endometrial cancers, change estimates for CC exposure (1.12 (95 % CI 1.01, 1.25)) (data not shown).

Discussion

This population based registry study is one of the largest to date to assess risk of cancer in women receiving fertility treatments. We observed elevated risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer, and risk appeared to be highest among nulliparous women following exposure to CC. An enhanced risk of thyroid cancer was observed for nulliparous women exposed to ART. Further, a modest increase in risk of breast cancer was observed with CC treatment, of similar magnitude as in our previous study on breast cancer risk after ART among parous women (11).

Ovarian cancer

Results demonstrate elevated risk of ovarian cancer after CC exposure, and suggest that also ART exposure may be associated with elevated risk, albeit among nulliparous women. For CC the risk among nulliparous women increased with increasing drug dosage. Fathalla suggested in 1971 that repeated involvement of the ovarian surface epithelium during ovulation could be related to development of ovarian neoplasms, coining the term “incessant ovulation” (34). Subsequent research has suggested that ovulatory pauses such as oral contraceptives (OC), pregnancy and lactation could reduce ovarian cancer risk (35). Our results indicate that an additional risk pertains to nulliparous women treated with fertility drugs, due not only to the lack of ovulatory pause associated with pregnancy, but also possibly to exposure to COH.

One of the first studies looking at fertility drugs and ovarian cancer, also found that women who remained childless had a higher risk than women conceiving after fertility treatment (36). Later, two US based studies reported higher risks associated with CC in women remaining nulliparous (37, 38). An Australian study also found non-significantly elevated risk of ovarian cancer in nulliparous IVF women (21). Two further studies, one from Sweden (8), and another from the Netherlands, both detected elevated risk of ovarian cancers after treatment with ART (7), but none provided separate estimates for nulliparous women. In our previous study, we found higher risk of ovarian cancer in women with primary infertility and those conceiving only one child (23). On the other hand, several other studies observe no increase in risk of ovarian cancers (39–41), and/or no difference in risk between nulliparous and parous women with fertility treatment (20, 41).

Our results suggest highest risk of ovarian cancer among those with the highest doses of CC. Although one earlier study also found an association between ovarian cancer and 12 or more cycles of CC (42), most other investigators observe no dose-response relationships with CC (16) nor ART (7, 20) and ovarian cancer. Although our findings are noteworthy, it is important to keep in mind that women receiving multiple doses of fertility drugs may be a selected group of women. It may well be that women exposed to many treatment rounds suffer resistant infertility, for example, for women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), only 20% become pregnant with each cycle of CC on average (43, 44). These women require many cycles of CC, but may indeed have elevated risks of ovarian cancer due to their ovulation disorders, and not the treatment itself. Finally, it is important to mention that the dose response analyses are based on few cases, possibly representing a chance finding.

We found elevated risk of borderline ovarian tumors in women treated with ART, in line with two previous studies (7, 45), but in contrast to a further three (41, 46, 47). In our study, we could not observe difference in risk among nulliparous and parous women. This was in line with findings from an Australian study (45), but contrary to a Dutch study that found highest risk among nulliparous women (7). In Norway these non-malignant tumors are systematically registered in the Cancer Registry of Norway. Elevated risks of borderline tumors in women treated with fertility hormones have been suggested to reflect surveillance bias, and not a biological explanation, which may explain the absence of risk with increasing number of cycles of ART. In the current study we did not have sufficient data to evaluate potential surveillance bias in terms of time since diagnosis.

Endometrial cancer

We found elevated risk of endometrial cancers in women exposed to CC, highest among nulliparous women, and for those with more than 6 treatment cycles. In contrast to this, a recent meta-analysis consisting of six studies found no elevation in risk connected to neither fertility drugs nor ART (48). Notably, one of the studies in the meta-analysis (49) was unable to replicate their earlier findings (50) where they had demonstrated increased risk of endometrial cancer associated with CC for six or more cycles.

It is worth mentioning that BMI and anovulatory infertility (PCOS) have been shown associated with endometrial cancer (51), and may cause confounding of our results, as this information is unavailable.

Thyroid cancer

Our study suggests thyroid cancer to be associated with ART treatment, with risks highest in the nulliparous group. Two other studies made similar findings, one detecting elevated risks among nulliparous women with use of CC (22, 52), whereas another discovered increased risk among parous women (12).

Thyroid tumors are more frequent in women than in men (53), giving reason to believe that female sex hormones may be involved. Ovarian stimulation has been shown to cause elevated levels of TSH (54) which promotes cellular proliferation in the gland. Both the normal thyroid gland and thyroid tumors exhibit estrogen receptors (55), although the exact mechanisms by which tumor growth is promoted are unclear (56). Thyroid cancer incidence has increased in recent years, possibly due to incidental findings of tumors with increased use of ultrasound, CT and MRI, however, when correcting for this in our analyses, risk was still elevated among ART women.

Breast cancer

We found an increased risk of breast cancer associated with CC treatment, but not with ART. The risk increase associated with CC use was restricted to parous women, and the magnitude of the estimate similar to our previous study of parous women (11). Although Brinton and colleagues reported an elevated risk of breast cancer in women exposed to multiple cycles (>12) of CC (15), we did not observe any relation of risk according to number of CC cycles. A recent meta-analysis concluded that the association between infertility treatment (any hormonal treatment) and risk of breast cancer was weak, but underlined that extensive use of CC should be limited due to concerning findings relating to breast cancer (19).

Other cancers

No association was found between fertility treatment and risks of colorectal, CNS cancer nor CMM. Reassuringly, the elevated risk of CNS tumors found in our previous study on parous women (11) could not be replicated presently, possibly reflecting the shorter follow-up in the present study, with data from the Norwegian Prescription Databaseonly available from 2004. Two recent papers support our null-findings on fertility drugs and CMM (13, 57). Two other studies conclude no association between use of CC and CRC (22, 58).

We observed a non-significant decrease in risk of cervical cancer among fertility treated women, in line with others studies (16, 49, 59), possibly due to infertile women’s regular gynecological examinations, including cervical screening tests leading to reduced risk of invasive cervical cancer (60).

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is its size. By using population-based registry data all the way back to 1960, we are able to obtain a nationwide study cohort that may be the largest to date adressing fertility drugs and cancer risk. In this study, collection of information on drug exposure from the Norwegian Prescription Database minimized the risk of recall bias (61, 62). Further, the Prescription Database only records prescribed drugs which are dispensed and collected by patients, reducing the risk of primary non-compliance (24, 63) and subsequently risk of misclassification. Moreover, the registry-based collection of data on cancer from the Cancer Registry of Norway and childbirths from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway is advantageous as the mandatory reporting to both registries ensures high external validity and completeness (27). Another strength of the study is that we are able to look at both ART and CC as separate exposures. In contrast to several other studies data from Medical Birth Registry enabled us to separate nulliparous and parous women, accounting for the effects of childbearing on cancer risk.

The study is at risk of some misclassification of exposure, since the Norwegian Prescription Databaseonly includes data from 2004. Thus, some women may be misclassified as unexposed if they only received fertility drugs before 2004. However, stratifying on age at inclusion did not reveal any differences in risk between women who were older compared to those that were younger in 2004. Misclassification of exposure may also occur if women receive fertility treatment abroad not recorded in the Norwegian Prescription Database (64). Using Prescription Database information does not provide the opportunity to assess the degree of adherence; although a drug is dispensed, the patient might not actually have taken it. Although, infertile patients seeking to conceive are likely to have high drug adherence (65).

In the present study, comorbidity data are unavailable. Firstly, this is important as nulliparous women may be more likely to suffer from chronic diseases including cancer, which prevent them from having children. However, then risk elevations would likely be observed for several cancer sites, not just the specific ones we observed. Secondly, with respect to comorbidity, information on fertility diagnoses are unavailable to us in the present study. This is an issue, for example has endometriosis been suggested associated with elevated risk of ovarian cancer (21, 66–68). In our study we are unable to disentangle the effects of the fertility treatment from underlying causes of infertility themselves. It may be that some women harbor pathological changes in the ovary leaving them prone to both infertility and oarian neoplasms. Thus, confounding by indication may be driving some of the observed associations between fertility drugs and ovarian cancer. This may also be the case for thyroid cancer as, it has been demonstrated that thyroxin substitution treatment is used more frequently by ART pregnant women, than by those pregnant after natural conception (69). It may therefore be that the preexisting thyroid disease may be a common cause of both infertility and thyroid neoplasms.

Some factors associated with cancer and infertility were unavailable: BRCA mutations, socioeconomic factors, smoking and body mass index (BMI). BMI is an potential confounder associated with both infertility (70) and breast (71) and endometrial cancer (72), and may be the reason at least in part why we observe elevations in risk after CC exposure. Oral contraceptives (OC) are known to reduce risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers. If OC use is less in infertile than in fertile women, this factor may be mediating some of the observed effects of fertility drugs on ovarian cancer.

Women treated with fertility drugs may be subject to some degree of surveillance bias, which could be a possible explanation for our findings of elevated risk of thyroid and borderline tumors. This could have been clarified by examining stage and mortality of cancers in exposed women in future studies.

It is also important to note that this study includes women of relatively young ages, and as a consequence the follow-up time is short. Thus, the median ages at cancer diagnosis were below the ages where cancer is prevalent, (37 years for exposed nulliparous women and 38 years for exposed parous women), and for some site specific analyses, number of cases in the comparison groups are low. Another limitation is that correction for multiple analyses has not been performed. However, the need to do to may be subject for discussion, as there may be little correlation between breast cancer with for example malignant melanoma, both with respect to tumor biology but also differences in etiology.

Conclusion

In this nationwide registry-based study, we used data on parity, drug exposure and cancer outcomes, to compare cancer risks associated with fertility drug exposures among parous and nulliparous women. Findings were reassuring for most cancers, although fertility treatment, particularly with CC, appeared to increase the risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer especially in nulliparous women. For some sites, including breast, endometrium and thyroid, there were some elevations in risk, although less consistently according to treatment type and parity.

Although some risk elevations are observed, it must be kept in mind that the study population is young, and its absolute cancer risk low. Future research should continue to monitor women treated for infertility as they grow older. Assessing ovarian cancer risk in women remaining childless after treatment, and risks associated with cumulative doses of fertility drugs is of importance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the Medical Birth Registry of Norway and the Cancer Registry of Norway for supplying the data. The interpretation and reporting of the Medical Birth Registry of Norway data is the sole responsibility of the authors, and no endorsement by the Registry is intended nor should be inferred

Funding

No specific funding was sought for the study; departmental funds (Oslo University Hospital) were used to support the author Marte M Reigstad throughout the study period and manuscript preparation. All other authors received no specific funding for this study.

Abbreviations

- ART

Assisted reproductive technology

- ATC

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

- BMI

Body mass index

- CC

Clomiphene citrate

- CI

Confidence interval

- CMM

Cutaneous malignant melanoma

- CNS

Central nervous system

- COH

Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation

- CRC

Colorectal Cancer

- CT

Computer tomography

- hCG

human chorionic gonadotropin

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IVF

In Vitro fertilization

- OC

Oral contraceptives

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PCOS

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

- PID

Personal identification number

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Schuler S, Ponnath M, Engel J, Ortmann O. Ovarian epithelial tumors and reproductive factors: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287(6):1187–1204. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-2784-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narod SA. Modifiers of risk of hereditary breast cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25(43):5832–5836. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook LS, Kmet LM, Magliocco AM, Weiss NS. Endometrial cancer survival among U.S. black and white women by birth cohort. Epidemiology. 2006;17(4):469–472. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000221026.49643.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambe M, Thorn M, Sparen P, Bergstrom R, Adami HO. Malignant melanoma: reduced risk associated with early childbearing and multiparity. Melanoma Res. 1996;6(2):147–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao YJ, Wang ZY, Gu J, Hu FF, Qi YJ, Yin QQ, et al. Reproductive Factors but Not Hormonal Factors Associated with Thyroid Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/103515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishihara O, Adamson GD, Dyer S, de Mouzon J, Nygren KG, Sullivan EA, et al. International committee for monitoring assisted reproductive technologies: world report on assisted reproductive technologies, 2007. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(2):402–413. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.11.004. e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Leeuwen FE, Klip H, Mooij TM, de Swaluw AMGV, Lambalk CB, Kortman M, et al. Risk of borderline and invasive ovarian tumours after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization in a large Dutch cohort. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(12):3456–3465. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kallen B, Finnstrom O, Lindam A, Nilsson E, Nygren KG, Olausson PO. Malignancies among women who gave birth after in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(1):253–258. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinton LA, Scoccia B, Moghissi KS, Westhoff CL, Althuis MD, Mabie JE, et al. Breast cancer risk associated with ovulation-stimulating drugs. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(9):2005–2013. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh371. Epub 2004/06/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen A, Sharif H, Svare EI, Frederiksen K, Kjaer SK. Risk of breast cancer after exposure to fertility drugs: Results from a large Danish cohort study. Cancer Epidem Biomar. 2007;16(7):1400–1407. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reigstad MM, Larsen IK, Myklebust TA, Robsahm TE, Oldereid NB, Omland AK, et al. Risk of breast cancer following fertility treatment--a registry based cohort study of parous women in Norway. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2015;136(5):1140–1148. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannibal CG, Jensen A, Sharif H, Kjaer SK. Risk of thyroid cancer after exposure to fertility drugs: results from a large Danish cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(2):451–456. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart LM, Holman CD, Finn JC, Preen DB, Hart R. Association between in-vitro fertilization, birth and melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2013;23(6):489–495. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luke B, Brown MB, Spector LG, Missmer SA, Leach RE, Williams M, et al. Cancer in women after assisted reproductive technology. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(5):1218–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.07.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinton LA, Scoccia B, Moghissi KS, Westhoff CL, Niwa S, Ruggieri D, et al. Long-term relationship of ovulation-stimulating drugs to breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(4):584–593. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva Idos S, Wark PA, McCormack VA, Mayer D, Overton C, Little V, et al. Ovulation-stimulation drugs and cancer risks: a long-term follow-up of a British cohort. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(11):1824–1831. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yli-Kuha AN, Gissler M, Klemetti R, Luoto R, Hemminki E. Cancer morbidity in a cohort of 9175 Finnish women treated for infertility. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(4):1149–1155. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siristatidis C, Sergentanis TN, Kanavidis P, Trivella M, Sotiraki M, Mavromatis I, et al. Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for IVF: impact on ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(2):105–123. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gennari A, Costa M, Puntoni M, Paleari L, De Censi A, Sormani MP, et al. Breast cancer incidence after hormonal treatments for infertility: systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150(2):405–413. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen A, Sharif H, Frederiksen K, Kjaer SK. Use of fertility drugs and risk of ovarian cancer: Danish Population Based Cohort Study. BMJ. 2009;338:b249. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart LM, Holman CD, Aboagye-Sarfo P, Finn JC, Preen DB, Hart R. In vitro fertilization, endometriosis, nulliparity and ovarian cancer risk. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(2):260–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Althuis MD, Scoccia B, Lamb EJ, Moghissi KS, Westhoff CL, Mabie JE, et al. Melanoma, thyroid, cervical, and colon cancer risk after use of fertility drugs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3 Pt 1):668–674. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reigstad MM, Larsen IK, Myklebust TA, Robsahm TE, Oldereid NB, Omland AK, et al. Cancer risk among parous women following assisted reproductive technology. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(8):1952–1963. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev124. Epub 2015/06/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furu K, Wettermark B, Andersen M, Martikainen JE, Almarsdottir AB, Sorensen HT. The Nordic Countries as a Cohort for Pharmacoepidemiological Research. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;106(2):86–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. [[updated 25.03.2011; cited 2016 16.12]];Structure and principles [Internet]. Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Available from: http://www.whocc.no/atc/structure_and_principles/

- 26.Irgens LM. The Medical Birth Registry of Norway. Epidemiological research and surveillance throughout 30 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79(6):435–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsen I, Smastuen M, Johannesen T, Langmark F, Parkin D, Bray F, et al. Data quality at the Cancer Registry of Norway: An overview of comparability, completeness, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(7):1218–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farquhar C, Rishworth JR, Brown J, Nelen WLDM, Marjoribanks J. Assisted reproductive technology: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2015;(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010537.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Usadi RS, Merriam KS. On-label and off-label drug use in the treatment of female infertility. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(3):583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Commenges D, Letenneur L, Joly P, Alioum A, Dartigues JF. Modelling age-specific risk: Application to dementia. Stat Med. 1998;17(17):1973–1988. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980915)17:17<1973::aid-sim892>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levesque LE, Hanley JA, Kezouh A, Suissa S. Problem of immortal time bias in cohort studies: example using statins for preventing progression of diabetes. BMJ. 2010;340:b5087. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoenfeld D. Partial Residuals for the Proportional Hazards Regression-Model. Biometrika. 1982;69(1):239–241. [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–868. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fathalla MF. Incessant ovulation--a factor in ovarian neoplasia? Lancet. 1971;2(7716):163. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Havrilesky LJ, Moorman PG, Lowery WJ, Gierisch JM, Coeytaux RR, Urrutia RP, et al. Oral Contraceptive Pills as Primary Prevention for Ovarian Cancer A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(1):139–147. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318291c235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whittemore AS, Harris R, Itnyre J. Characteristics relating to ovarian cancer risk: collaborative analysis of 12 US case-control studies. IV. The pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Collaborative Ovarian Cancer Group. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136(10):1212–1220. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trabert B, Lamb EJ, Scoccia B, Moghissi KS, Westhoff CL, Niwa S, et al. Ovulation-inducing drugs and ovarian cancer risk: results from an extended follow-up of a large United States infertility cohort. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(6):1660–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brinton LA, Lamb EJ, Moghissi KS, Scoccia B, Althuis MD, Mabie JE, et al. Ovarian cancer risk after the use of ovulation-stimulating drugs. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(6):1194–11203. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000128139.92313.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venn A, Watson L, Bruinsma F, Giles G, Healy D. Risk of cancer after use of fertility drugs with in-vitro fertilisation. The Lancet. 1999;354(9190):1586–1590. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lerner-Geva L, Rabinovici J, Olmer L, Blumstein T, Mashiach S, Lunenfeld B. Are infertility treatments a potential risk factor for cancer development? Perspective of 30 years of follow-up. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28(10):809–814. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.671391. Epub 2012/04/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asante A, Leonard PH, Weaver AL, Goode EL, Jensen JR, Stewart EA, et al. Fertility drug use and the risk of ovarian tumors in infertile women: a case-control study. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(7):2031–2036. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rossing MA, Daling JR, Weiss NS, Moore DE, Self SG. Ovarian tumors in a cohort of infertile women. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(12):771–776. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409223311204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorlitsky GA, Kase NG, Speroff L. Ovulation and pregnancy rates with clomiphene citrate. Obstet Gynecol. 1978;51(3):265–269. doi: 10.1097/00006250-197803000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Imani B, Eijkemans MJ, te Velde ER, Habbema JD, Fauser BC. Predictors of chances to conceive in ovulatory patients during clomiphene citrate induction of ovulation in normogonadotropic oligoamenorrheic infertility. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(5):1617–1622. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.5.5705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart LM, Holman CDJ, Finn JC, Preen DB, Hart R. In vitro fertilization is associated with an increased risk of borderline ovarian tumours. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129(2):372–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cusido M, Fabregas R, Pere BS, Escayola C, Barri PN. Ovulation induction treatment and risk of borderline ovarian tumors. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23(7):373–376. doi: 10.1080/09513590701350341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mosgaard BJ, Lidegaard O, Kjaer SK, Schou G, Andersen AN. Ovarian stimulation and borderline ovarian tumors: a case-control study. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(6):1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saso S, Louis LS, Doctor F, Hamed AH, Chatterjee J, Yazbek J, et al. Does fertility treatment increase the risk of uterine cancer? A meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gyn R B. 2015;195:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brinton L, Trabert B, Shalev V, Lunenfeld E, Sella T, Chodick G. In vitro fertilization and risk of breast and gynecologic cancers: A retrospective cohort study within the Israeli Maccabi Healthcare Services. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1189–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Althuis MD, Moghissi KS, Westhoff CL, Scoccia B, Lamb EJ, Lubin JH, et al. Uterine cancer after use of clomiphene citrate to induce ovulation. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(7):607–615. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barry JA, Azizia MM, Hardiman PJ. Risk of endometrial, ovarian and breast cancer in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human reproduction update. 2014;20(5):748–758. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brinton LA, Moghissi KS, Scoccia B, Lamb EJ, Trabert B, Niwa S, et al. Effects of fertility drugs on cancers other than breast and gynecologic malignancies. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(4):980–988. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cancer Registry of Norway. [[cited 2016 Dec 17]];Cancer in Norway 2015 - Cancer incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in Norway [Internet] 2016 Oct; Available from: https://www.kreftregisteret.no/globalassets/cancer-in-norway/2015/cin_2015.pdf.

- 54.Mintziori G, Goulis DG, Toulis KA, Venetis CA, Kolibianakis EM, Tarlatzis BC. Thyroid function during ovarian stimulation: a systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(3):780–785. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaudhuri PK, Prinz R. Estrogen receptor in normal and neoplastic human thyroid tissue. Am J Otolaryngol. 1989;10(5):322–326. doi: 10.1016/0196-0709(89)90107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zane M, Catalano V, Scavo E, Bonanno M, Pelizzo MR, Todaro M, et al. Estrogens and stem cells in thyroid cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:124. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spaan M, van den Belt-Dusebout AW, Schaapveld M, Mooij TM, Burger CW, van Leeuwen FE, et al. Melanoma risk after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(5):1216–1228. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spaan M, van den Belt-Dusebout AW, Burger CW, van Leeuwen FE, group OM-p. Risk of Colorectal Cancer After Ovarian Stimulation for In Vitro Fertilization. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(5):729–737. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.018. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yli-Kuha AN, Gissler M, Klemetti R, Luoto R, Hemminki E. Cancer morbidity in a cohort of 9175 Finnish women treated for infertility. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(4):1149–1155. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lonnberg S, Hansen BT, Haldorsen T, Campbell S, Schee K, Nygard M. Cervical cancer prevented by screening: Long-term incidence trends by morphology in Norway. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(7):1758–1764. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.West SL, Strom BL, Freundlich B, Normand E, Koch G, Savitz DA. Completeness of prescription recording in outpatient medical records from a health maintenance organization. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(2):165–171. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.West SL, Savitz DA, Koch G, Strom BL, Guess HA, Hartzema A. Recall accuracy for prescription medications: self-report compared with database information. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(10):1103–1112. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beardon PH, McGilchrist MM, McKendrick AD, McDevitt DG, MacDonald TM. Primary non-compliance with prescribed medication in primary care. BMJ. 1993;307(6908):846–848. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6908.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Inhorn MC, Patrizio P. The global landscape of cross-border reproductive care: twenty key findings for the new millennium. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;24(3):158–163. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328352140a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McGovern PG, Carson SA, Barnhart HX, Myers ER, Legro RS, Diamond MP, et al. Medication adherence and treatment success in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development-Reproductive Medicine Network’s Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Trial. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(4):1283–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Leeuwen FE, Klip H, Mooij TM, van de Swaluw AM, Lambalk CB, Kortman M, et al. Risk of borderline and invasive ovarian tumours after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization in a large Dutch cohort. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(12):3456–3465. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brinton LA, Gridley G, Persson I, Baron J, Bergqvist A. Cancer risk after a hospital discharge diagnosis of endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(3):572–579. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Borgfeldt C, Andolf E. Cancer risk after hospital discharge diagnosis of benign ovarian cysts and endometriosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83(4):395–400. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Busnelli A, Vannucchi G, Paffoni A, Faulisi S, Fugazzola L, Fedele L, et al. Levothyroxine dose adjustment in hypothyroid women achieving pregnancy through IVF. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2015;173(4):417–424. doi: 10.1530/EJE-15-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rich-Edwards JW, Goldman MB, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, et al. Adolescent body mass index and infertility caused by ovulatory disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(1):171–177. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(94)90465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carmichael AR, Bates T. Obesity and breast cancer: a review of the literature. Breast. 2004;13(2):85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ. 2007;335(7630):1134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39367.495995.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.