Abstract

Objective

To determine the feasibility of conducting a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of corticosteroids in pediatric septic shock.

Design

Randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial.

Setting

Seven tertiary level, pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) in Canada.

Patients

Children aged newborn to 17 years inclusive with suspected septic shock.

Intervention

Administration of intravenous hydrocortisone versus placebo until hemodynamic stability is achieved or for a maximum of seven days.

Measurements and Main Results

174 patients were potentially eligible of whom 101 patients met eligibility criteria. Fifty-seven patients were randomized and 49 patients (23 and 26 patients in the hydrocortisone and placebo groups respectively) were included in the final analysis. The mean time from screening to randomization was 2.4 ± 2.1 hours and from screening to first dose of study drug was 3.8 ± 2.6 hours. Forty-two percent of potentially eligible patients (73/174) received corticosteroids prior to randomization: 38.5% (67/174) were already on corticosteroids for shock at time of screening and in 3.4% (6/174), the treating physician wished to administer corticosteroids. Six of 49 randomized patients (12.2%) received open-label steroids, three in each of the hydrocortisone and placebo groups. Time on vasopressors, days on mechanical ventilation, PICU and hospital length of stay and the rate of adverse events were not statistically different between the two groups.

Conclusions

This study suggests that a large RCT on early use of corticosteroids in pediatric septic shock is potentially feasible. However, the frequent use of empiric corticosteroids in otherwise eligible patients remains a significant challenge. Knowledge translation activities, targeted recruitment and alternative study designs are possible strategies to mitigate this challenge.

Keywords: pediatric septic shock, sepsis, corticosteroids, steroids, pilot trial, randomized controlled trial

Background

Septic shock accounts for 4–8 % of pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admissions (1–3), results in significant morbidity (4;5) and carries a 12 to 25% mortality rate (1–3;6) depending on the setting in which it occurs. While antibiotics, fluids and vasoactive agents are the mainstay of therapy, the high morbidity caused by this condition has led clinicians to consider adjunctive therapies such as corticosteroids when hemodynamic instability persists despite aggressive fluid and vasopressor administration. This approach is endorsed by the current Surviving Sepsis guidelines (7), however, there is no clear evidence to support this practice (8;9). Some pediatric studies have reported an improvement in hemodynamics with the use of corticosteroids in septic shock (4;10) while other studies have suggested an increase in secondary infections, hyperglycemia and repression of adaptive immunity (1;11;12). There is currently no consensus on the indications, target population or dose for the use of adjunctive corticosteroids in pediatric septic shock (13–15).

This lack of consensus is due to multiple factors, including conflicting evidence from adult trials (16;17), lack of adequately powered pediatric randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (8), varying target populations (4;5) and difficulties with conducting and completing pediatric critical care trials (18;19). Despite these challenges, intensivists still believe that the role of corticosteroids in septic shock needs to be clarified (8;15) and state that they would be willing to recruit patients into a randomized trial on this subject (14). However, more than 90% of pediatric intensivists also state that they would administer open label steroids to patients with septic shock who were receiving two or more vasoactive infusions thus suggesting a lack of equipoise on the issue (14). Further adding to the challenges of conducting trials on pediatric septic shock are difficulties in defining eligible patients, obtaining consent and recruiting patients within a narrow time window (20;21). Therefore, a pilot study is necessary prior to embarking on a larger trial.

The main goal of this pilot trial was to determine the feasibility of conducting a larger pragmatic RCT of corticosteroids in pediatric septic shock. Our primary objective was to determine the rate of patient accrual. Secondary outcomes included the concordance of our pragmatic definition of septic shock with previous definitions, rate of protocol adherence, frequency of, and reasons for, open-label steroid use, incidence of adverse events and determination of baseline estimates of clinically important outcomes such as time to discontinuation of inotropes, length of mechanical ventilation and PICU length of stay.

Methods

Experimental design

We conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial in seven centres in Canada between July 2014 and March 2016. The protocol was approved by the research ethics boards (REBs) in all centers. The REB at five centers approved a deferred consent model with a sixth center endorsing this model part way through the study. The remaining center required prospective informed consent prior to randomization. The study rationale, design, protocol and consent process have been previously published (22). Written, informed consent was obtained for all participants prior to completion of the study procedures.

Patients

Patients were included they if were aged newborn (>38 weeks corrected gestational age) to 17 years and had been receiving any dose of any vasoactive infusion for between one and six hours. Exclusion criteria included patients who were: known or suspected to have hypothalamic, pituitary or adrenal disease, currently receiving steroids for shock prior to randomization, expected to have care withdrawn, pregnant, post-operative from cardiac surgery, administered their first dose of a vasoactive infusion > 24 hours after PICU admission, not expected to be on a vasoactive infusion at the time of administration of the first dose of study drug, suspected or proven to have primary cardiogenic, spinal, hemorrhagic or hypovolemic shock, previously enrolled in the STRIPES study, started on a vasoactive agent for reasons not related to shock or if their attending physician refused participation. Patients were recruited from the Emergency Department, pediatric wards or PICU and PICU admissions were screened daily to determine if eligible patients had been missed.

Randomization

A randomization list was generated by the Methods Centre at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (OHRI). Patients were randomized 1:1 using variable block sizes (2–4 patients/block) stratified by site. The active drug and placebo (hydrocortisone and normal saline) were identical in appearance, volume and smell and all study personnel, members of the bedside health care team and patients/families were blinded to the study group assignment. The protocol required the patient be randomized and administered the first dose of study drug within 6 hours and 8 hours of meeting eligibility criteria respectively.

Intervention

Patients randomized to the hydrocortisone treatment arm received an initial intravenous (IV) bolus of 2 mg/kg hydrocortisone, followed by 1 mg/kg of hydrocortisone every six hours until the patient met stability criteria (defined as no increase in their vasoactive infusions and no administration of a fluid bolus) for at least 12 hours. We chose this dosing regimen as most physicians report using 5 mg/kg/day of hydrocortisone for shock (1;14) with some physicians also suggesting an initial bolus dose (14). Hydrocortisone dosing was then reduced to 1 mg/kg every 8 hours until all vasoactive infusions had been discontinued for at least 12 hours. We chose to wean the hydrocortisone to q8h rather than stop it as evidence has suggested that abrupt cessation of corticosteroids in a stable shock patient may lead to rebound hemodynamic instability and resurgence of inflammatory markers (23). If following the de-escalation or discontinuation of hydrocortisone, the patient required fluid boluses and/or an increase in their vasoactive infusion(s), their hydrocortisone was increased back to 1 mg/kg of hydrocortisone IV q6h until they met stability criteria again. Hydrocortisone was continued for a maximum of 7 days to prevent adrenal suppression.

Physicians were encouraged, but not mandated, to follow the Surviving Sepsis Guidelines (7) in the management of their patients. Management decisions with regard to endotracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation, sedation and analgesia, additional vasoactive agents, red cell transfusions, antibiotics and fluid boluses were left to the discretion of the treating physician.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was the patient accrual rate. Secondary outcomes included measurement of 1) agreement between clinical diagnosis of septic shock with either the International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference definition of septic shock (24) or ICD-10 diagnostic codes (25); 2) the number of eligible patients who were randomized within six hours from identification; 3) rate of protocol adherence (percentage of study drug doses correctly administered); 4) frequency of corticosteroid use outside of the protocol (pre-screening and post-randomization) and 5) differences between clinically important endpoints (PICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, time on vasopressors and duration of mechanical ventilation) between the two groups. Feasibility criteria were set a priori at ≥ 80% for outcomes 1, 2, 3 and at < 20% for outcome 4.

Sample size and statistical analysis

The ability of the pilot study to attain its objectives was predicated on achieving a convenience sample of a minimum of 60 patients over a period of one year. This equated to an anticipated recruitment rate of approximately 0.7 patients per site per month. This design tested the acceptability of the eligibility criteria, and open-label steroid use, at seven sites, and with exposure to up to 50 different clinicians. Due to the small sample size and short recruitment period, no interim analyses were planned.

Descriptive analyses were employed in assessing the feasibility objectives of this pilot RCT. Presented are point estimates of recruitment, feasibility events (including adherence to protocol) and open-label corticosteroid use, as proportions with 95% confidence intervals. Data is presented as means and standard deviations for normally distributed variables, or medians and inter-quartile ranges, when appropriate. An intention to treat analysis was performed for secondary outcomes for patients who were randomized, had informed consent provided and received at least one dose of study drug. A log rank test and Cox regression model censoring for death was employed to examine the association of hydrocortisone use and lengths of stay (adjusted for PRISM score, mechanical ventilation and presence of a pre-existing condition), time on vasopressors (adjusted for PRISM score, receipt of antibiotics in the Emergency Department, admission lactate and pre-enrollment fluid boluses) and duration of mechanical ventilation (adjusted for PRISM score). Comparison of multiple proportions was performed using Fisher’s exact test. Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios with their 95% confidence limits as well as P-values are presented.

Results

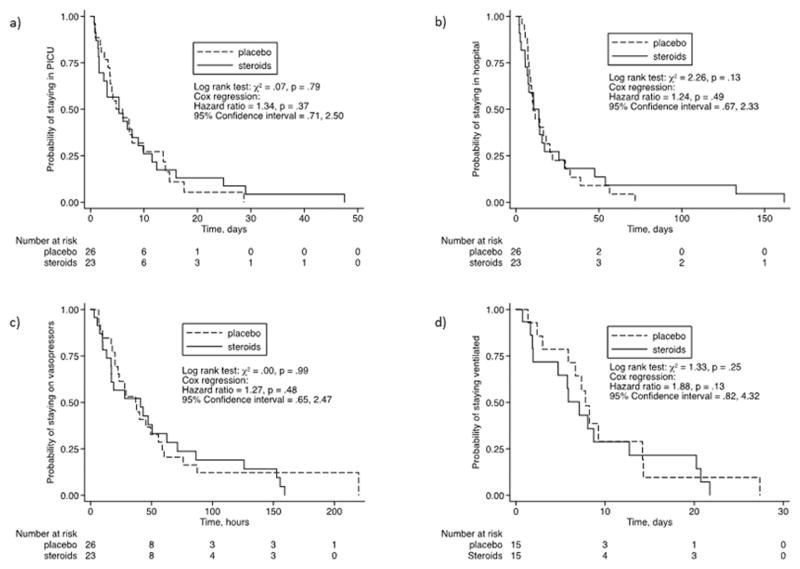

We screened patients for eligibility between July 28th, 2014 and March 31st, 2016 (see Figure 1). The total number of recruitment months was 90 across all study sites, with the site-specific recruitment period ranging from two to 20 months (median of 15, IQR: 8, 16). Of the 720 patients screened, 101 patients met eligibility criteria and 66 patients were approached for consent (including prospective informed consent and deferred consent). Fifty-seven patients were randomized (86.4%, 57/66). Of these, six patients (10.5%, 6/57) were excluded as their guardians did not consent to participation (deferred consent), one patient did not receive study drug as they were no longer eligible once the study drug was dispensed and in one patient the nurse declined participation due to a misunderstanding of the deferred consent process. Therefore, 49 patients were included in the final analysis representing 82% of the lower end of our target sample size range (we estimated 60 to 72 patients) with a mean accrual rate of 0.54 ± 0.29 (95% CI: 0.46, 0.62, range 0 to 1.47) patients per month per site. Twenty-six of these patients were randomized to the placebo group and 23 to the hydrocortisone group.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

The baseline characteristics of the two groups did not demonstrate any statistically significant differences (Table 1). There was no difference in the median PRISM score of eligible patients who were and were not enrolled (7, IQR: 5, 11 versus 7, IQR: 5, 13; P= 0.97). Reasons for non-enrollment of eligible patients are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included patientsa.

| Variable | Placebo (n = 26) |

Hydrocortisone (n = 23) |

|---|---|---|

| b Age – months - median – (IQR) | 108.0 (44.5,146.5) | 90.0 (14.3, 155.8) |

| Gender – male - % | 50.0 | 51.2 |

| Pre-existing medical condition - % | 57.7 | 52.2 |

| Admission PRISM score – median – (IQR) | 7 (5, 11) | 6 (4, 14) |

| Admission PELOD score - median – (IQR) | 6 (3, 9) | 6 (4, 9) |

| c Fluid requirements – mls/kg - median – (IQR) | 49 (36, 63) | 56 (30, 75) |

| d Day 1 inotrope score - median – (IQR) | 10.0 (6.5, 21.0) | 12.0 (6.9, 32.5) |

| Admission lactate – mmol/L - median – (IQR) | 2.5 (1.2, 3.6) | 1.7 (1.0, 3.1) |

| Mechanically ventilated - % | 61.5 | 65.2 |

| Admission hemoglobin – g/L - median – (IQR) | 100 (80, 118) | 103 (84, 111) |

There were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics between groups.

IQR = interquartile range

Total amount of fluid received in the 6 hours prior to enrollment.

Inotrope score = Dopamine dose (mcg/kg/min) + Dobutamine dose (mcg/kg/min) + 100 × Epinephrine dose (mcg/kg/min) + 10 × Milrinone dose (mcg/kg/min) + 10,000 × Vasopressin dose (units/kg/min) + 100 × Norepinephrine dose (mcg/kg/min)

Feasibility of Randomization

The time to randomization and other feasibility endpoints are shown in Table 2. One randomized patient received study drug more than eight hours post meeting eligibility criteria (received at 10 hours). Only five of 101patients who met eligibility criteria were excluded because of insufficient time to prepare the study package. Study drug was correctly administered (dosage, timing and frequency) in 97.6% of dosages. There were four documented protocol violations amongst the 49 included patients: patients included who met exclusion criteria (n = 2; no longer on vasoactive infusion, n = 1; on vasoactive infusion > 6 hours, n = 1), enrolment more than eight hours after meeting eligibility criteria (n = 1) and accidental unblinding of the study coordinator (n = 1).

Table 2.

Feasibility endpoints.

| Measurement | Value |

|---|---|

| Eligible patients not randomized due to time limit – no. (%) | 6/101 (5.9) |

| Time to randomization – hrs – mean ± s.d.a | 2.4 ± 2.1 |

| Consent rate - %b | 74.2 |

| Time to first dose of study drug – hrs - mean ± s.d. | 3.8 ± 2.6 |

| Open label steroids administered – no. (%) | 6 (12.2) |

| Protocol violations - no. (% of patients) | 4 (8.2) |

s.d. = standard deviation

Sixty-six eligible patients were approached for consent of whom 17 refused participation.

Definition of septic shock

For the purposes of this study, septic shock was defined as cardiovascular instability, requiring the administration at least one vasoactive medication, which in the opinion of the treating physician was not attributable to a hemorrhagic, hypovolemic, cardiogenic, or neurogenic/spinal pathology. Using this pragmatic definition, 49 study patients were identified as having septic shock at hospital admission. End of admission chart review demonstrated that 44 patients (89.8%) met the International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference definition of septic shock (24) and 48 patients (98%) met the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria (25) for septic shock. The five patients who were excluded using the Consensus Conference definition did not meet the age defined heart rate and/or blood pressure criteria but were still assessed by their treating physicians as having septic shock. One patient met the International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference definition of septic shock but not the ICD-10 criteria and had a final discharge diagnosis of myocardial necrosis secondary to crystal methamphetamine ingestion.

Non-study usage of corticosteroids

Seventy-three patients (42.0%, 73/174) were ineligible for the study because of physician directed steroid administration prior to randomization. Of the 38.5% (67/174) were excluded because corticosteroids has already been initiated for shock at the time of screening (in the ICU or ED), and 3.4% (6/174) because the treating physician refused to enroll the patient, citing their intent to administer corticosteroids. An additional six of the 49 randomized patients (12.2%) received open-label corticosteroids, three in the hydrocortisone and placebo groups respectively. All patients who were administered open-label corticosteroids were receiving a minimum of two vasoactive infusions and had received at least 50 ml/kg of resuscitation fluids (5/6 had received over 120 ml/kg of fluids). The treating physician stated “resistant shock” as the reason for open-label corticosteroid administration in all six cases. There was no statistically significant difference in the median PRISM score (12, IQR: 5, 20 versus 6, IQR: 5, 12; P = 0.48), inotropic score (21.5, IQR: 5, 65 versus 10.0, IQR: 5, 22; P = 0.14) or median total fluid received prior to enrolment (52 ml/kg, IQR: 37, 83 versus 48 ml/kg, IQR 26, 82; P = 0.85) between those who did and did not receive open label corticosteroids. The median total dose of corticosteroids received was significantly different in the placebo versus hydrocortisone groups (0, IQR: 0, 0 versus 10, IQR: 5, 20; P < 0.0001). The rate of corticosteroid use for shock (prior to screening and post-randomization) varied between centres (range 12% to 61%) and was statistically different (P = 0.003).

Clinical Endpoints

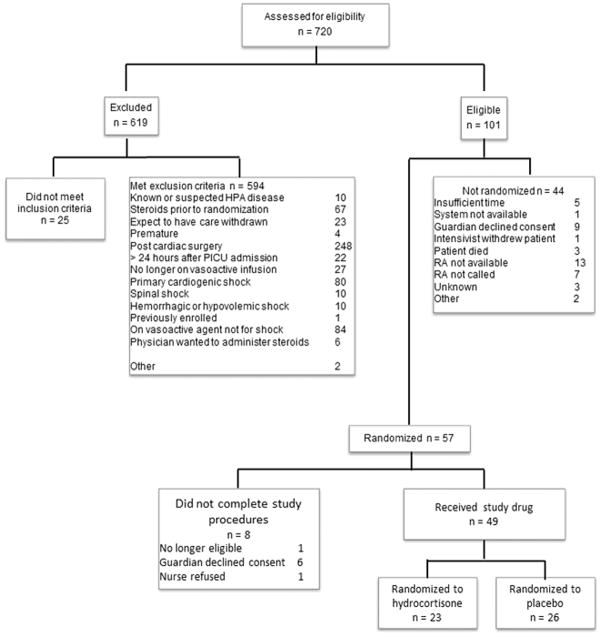

The median values for several clinically important endpoints in both groups are shown in Table 3. Time on vasopressors, days on mechanical ventilation and PICU length of stay were not statistically different between the two groups even after adjusting for confounders (see Figure 2). There was no difference in the rate of pre-defined adverse events between the two groups.

Table 3.

Clinically important endpoints

| Endpoint | Placebo (n = 26) | Hydrocortisone (n = 23) | P value | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) or OR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time on vasopressors – hrs - median (IQR) | 33.1 (19.4, 59.1) | 38.2 (13.2, 71.3) | 0.65 | 1.14 (0.63, 2.08) |

| Days on mechanical ventilation - median (IQR) | 7.4 (3.0, 9.3) | 5.8 (1.7, 11.7) | 0.37 | 1.27 (0.57, 2.82) |

| PICU length of stay – days - median (IQR) | 7.8 (4.0, 14.0) | 8.3 (3.7, 15.0) | 0.48 | 0.97 (0.53, 1.77) |

| PICU mortality – No. (%) | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 0.61 | 0.35 (0.034, 3.61) |

| Hospital length of stay – days - median (IQR) | 9.6 (7.1, 20.9) | 10.7 (5.4, 25.9) | 0.79 | 0.93 (0.51, 1.71) |

| a Fluid requirements – ml/kg - median (IQR) | 382 (197, 773) | 417 (219, 734) | 0.89 | n/a |

| Nitric oxide - No. (%) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (8.7) | 0.59 | 2.38 (0.20, 28.14) |

| ECMO – No. (%) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0.37 | n/a |

| CRRT – No. (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.04) | 0.47 | n/a |

| Number of patients transfused (%) | 11 (42.3) | 6 (26.1) | 0.24 | 0.48 (0.14, 1.62) |

| Adverse events | ||||

| GI bleeding – No. (%) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (8.7) | 1.0 | 1.14 (0.14, 8.84) |

| New infection – No. (%) | 5 (19.2) | 6 (12.2) | 0.73 | 1.48 (0.39, 5.71) |

| Insulin infusion – No. (%) | 1 (3.8) | 4 (17.5) | 0.17 | 5.26 (0.54, 51.20) |

During the PICU admission.

Odds ratio calculated for dichotomous variables and hazard ratio for continuous variables.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for corticosteroids vs placebo in septic shock.

a) Adjusted for PRISM, mechanical ventilation, pre-existing conditions.

b) Adjusted for PRISM, mechanical ventilation, pre-existing conditions.

c) Adjusted for PRISM, antibiotics, lactate, fluid resuscitation volume.

d) Adjusted for PRISM.

Discussion

We demonstrated that enrollment of patients into a trial of corticosteroids in pediatric septic shock was potentially feasible as evidenced by the concordance of physicians’ clinical suspicion of septic shock with accepted definitions (24;25), the ability to randomize eligible patients within six hours of their identification, the rate of protocol adherence and the acceptably low rate of open-label steroid use once patients were randomized. However, the lack of equipoise amongst critical care physicians as evidenced by the frequent overall use of corticosteroids remains the most significant impediment to the recruitment of otherwise eligible patients.

Although we did not quite achieve our predefined goal of a minimum of 60 randomized patients, we did come close. Fortunately, we identified several modifiable factors that could improve recruitment in a future trial. For the purposes of this pilot study, we aimed to demonstrate the feasibility of early administration of corticosteroids in patients who had not been ill for a prolonged period (i.e. in PICU for less than 24 hours) which resulted in the exclusion of 22 patients. This criterion could be modified in a future study to include all patients with septic shock regardless of their pre-existing time in hospital. Another 20 potentially eligible patients were missed due to the research assistant not being called (7/20) or not being available (13/20). Project related educational initiatives for healthcare teams as well as adequate funding to provide 24/7 research assistant coverage would further improve recruitment rates. In addition, the rate of corticosteroid use varied significantly between centres suggesting that inclusion of centres with lower rates of steroid usage would improve recruitment rates for a future trial. Finally, feasibility is also a function of the planned sample size and therefore a 400 patient phase III trial would be potentially feasible with the current recruitment rate by including 15 centers over 5 years.

We demonstrated that a pragmatic protocol, whereby physicians provided care according to their clinical judgement, resulted in two well-matched groups with regard to all clinically important baseline characteristics despite a small sample size. Our pragmatic approach to the definition of septic shock resulted in the inclusion of five patients who did not meet the International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference definition (24), however four of these five patients did fulfill the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for septic shock (25). The five patients who did not meet the Consensus definition missed inclusion due to heart rates/and or blood pressure values that were within 10% of the age defined criteria. This finding is consistent with several studies which have demonstrated that physicians define sepsis more broadly than consensus definitions do and that use of consensus definitions for research studies may result in significant limitations to the generalizability of their findings (26;27). It is possible that our pragmatic approach could result in the inclusion of patients with shock from conditions other than sepsis such as a drug overdose; however, it is likely that these patients would be limited in number and would be balanced between groups in a larger RCT. Finally, the lack of adrenal axis testing performed in children with suspected septic shock (1;14) suggests that physicians use clinical criteria rather than research criteria or guidelines to inform their decision to administer corticosteroids and therefore use of a clinical suspicion of septic shock for future trials may prove more valuable.

The most common reason, by far, for exclusion of potentially eligible patients was the desire of treating physicians to administer corticosteroids to children with septic shock. Not surprisingly, corticosteroid use varied significantly by center. Sixty-seven patients received corticosteroids for shock in community hospitals, emergency departments and on general pediatric wards prior to being screened by the research assistants. Physicians refused participation for another six patients because they wished to administer corticosteroids and another six patients received open label steroids post randomization. These findings are especially interesting given the lack of high level evidence in pediatrics supporting a benefit of corticosteroids in septic shock (8) and a recent adult trial showing no benefit and potential for increased harm with corticosteroid administration (16). However, corticosteroid administration to children with septic shock and absolute adrenal insufficiency is advocated in the widely publicised and promoted Surviving Sepsis Guidelines (7). Practitioners participating in this study were encouraged to model their care based on these guidelines. There may have therefore have been a reluctance among some practitioners to ignore these guidelines despite the lack of RCT evidence for its recommendation (8;28). In addition, our trial did not show a statistically significant benefit in mortality rate, PICU and hospital length of stay, time on vasopressors and length of mechanical ventilation with the use of corticosteroids. Although this was a pilot study and therefore not specifically powered to detect a difference in these outcomes, it is nevertheless the largest randomised controlled trial in pediatric septic shock to date.

Given the frequency of empiric corticosteroid use, strategies need to be developed to address this issue prior to conducting a larger trial. Possible options include knowledge translation activities, selection of centres with demonstrated equipoise, use of an adaptive design or 2:1 randomization scheme and delineation of a clear exit strategy.

There are several limitations to this study. The first limitation is that a significant number of potentially eligible patients could not be enrolled in the study since they were administered corticosteroids prior to randomization. This may have resulted in a selection bias for the patients ultimately included in this trial and has implications for the feasibility of a future trial. Possible options to overcome the high rate of empiric corticosteroid usage include knowledge translation activities, selection of centres with demonstrated equipoise, use of an adaptive design or 2:1 randomization scheme and delineation of a clear exit strategy. The other main limitation was the small sample size, which limits generalizability of results and the secondary analyses. However, the small sample size was selected based on the objectives of this pilot study, and our a priori defined objectives did not include being powered to detect a difference in clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

This pilot study suggests a large randomized controlled trial to evaluate early use of corticosteroids in pediatric septic shock is potentially feasible. A lack of equipoise amongst pediatric critical care physicians as evidenced by the frequent use of empiric corticosteroids in otherwise eligible patients remains a significant challenge to randomized controlled trials of corticosteroid efficacy in pediatric septic shock. Further knowledge translation activities, targeted recruitment and alternative study designs are possible strategies to mitigate this challenge.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Operating Grant, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Footnotes

The coordinating site was the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario and the work was performed at the British Columbia Women and Children’s Hospital, Alberta Children’s Hospital, Hamilton Health Sciences Center, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Montreal Children’s Hospital, St. Justine’s Hospital and Izaac Walton Killam Hospital for Children.

Trial Registration: Clinical Trials (NCT 02044159), http://www.clinicaltrials.gov

Copyright form disclosure: Dr. Menon’s institution received funding from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Dr. McNally disclosed: work was funded through a CIHR grant. Dr. Acharya received funding from Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO). Dr. Wong received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). His institution received funding from the NIH. Dr. Lawson’s institution received funding from CIHR. Dr. Gilfoyle’s institution received funding from CHEO Research Institute (original funder CIHR), Alberta Innovates Health Solutions, Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation, CIHR, Heart and Stroke Foundation, Alberta Health Services, and Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Ste Justine. Dr. Wensley disclosed: expenses for the study were covered by the CIHR grant (i.e. pharmacy and lab costs). He received support for article research from CIHR. Dr. Gottesman’s institution received funding from CIHR. He received support for article research from CIHR. Dr. Morrison’s institution received funding from CHEO. He disclosed off-label product use: Hydrocortisone use in children with septic shock. Dr. Choong’s institution received funding from CIHR to support research personnel in the enrollment and data collection, and from Academic Health Sciences Innovation Grant. She disclosed she is employed by McMaster University and Hamilton Health Sciences. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Menon K, McNally JD, Choong K, et al. A Cohort Study of Pediatric Shock: Frequency of Corticosteriod Use and Association with Clinical Outcomes. Shock. 2015;44:402–9. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kissoon N, Carcillo JA, Espinosa V, et al. World Federation of Pediatric Intensive Care and Critical Care Societies: Global Sepsis Initiative. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:494–503. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318207096c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlapbach LJ, Straney L, Alexander J, et al. Mortality related to invasive infections, sepsis, and septic shock in critically ill children in Australia and New Zealand, 2002–13: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:46–54. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valoor HT, Singhi S, Jayashree M. Low-dose hydrocortisone in pediatric septic shock: an exploratory study in a third world setting. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10:121–5. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181936ab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slusher T, Gbadero D, Howard C, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double blinded trial of dexamethasone in African children with sepsis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:579–83. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199607000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss SL, Fitzgerald JC, Pappachan J, et al. Global epidemiology of pediatric severe sepsis: the sepsis prevalence, outcomes, and therapies study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:1147–57. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2323OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:165–228. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menon K, McNally D, Choong K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of steroids in pediatric shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:474–80. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31828a8125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annane D, Bellissant E, Bollaert PE, et al. Corticosteroids in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults: a systematic review. JAMA. 2009;301:2362–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasidharan P. Role of corticosteroids in neonatal blood pressure homeostasis. Clin Perinatol. 1998;25:723–40. xi. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Markovitz BP, Goodman DM, Watson RS, et al. A retrospective cohort study of prognostic factors associated with outcome in pediatric severe sepsis: what is the role of steroids? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:270–4. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000160596.31238.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Allen GL, et al. Corticosteroids are associated with repression of adaptive immunity gene programs in pediatric septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:940–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201401-0171OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menon K, Lawson M. Identification of adrenal insufficiency in pediatric critical illness. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8:276–8. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000262796.38637.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menon K, McNally JD, Choong K, et al. A survey of stated physician practices and beliefs on the use of steroids in pediatric fluid and/or vasoactive infusion-dependent shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:462–6. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31828a7287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carmean A, Fortenberry JD, McCracken C, et al. A Survey of Attitudes and Practices Regarding the Use of Steroid Supplementation in Pediatric Sepsis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:694–8. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:111–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Annane D, Sebille V, Charpentier C, et al. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002;288:862–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.7.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffett M, Choong K, Hartling L, et al. Randomized controlled trials in pediatric critical care: a scoping review. Crit Care. 2013;17:R256. doi: 10.1186/cc13083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menon K, Wong HR. Corticosteroids in Pediatric Shock: A Call to Arms. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:e313–e317. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menon K, Ward RE, Gaboury I, et al. Factors affecting consent in pediatric critical care research. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:153–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duffett M, Choong K, Hartling L, et al. Pilot Randomized Trials in Pediatric Critical Care: A Systematic Review. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:e239–e244. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Hearn K, McNally D, Choong K, et al. Steroids in fluid and/or vasoactive infusion dependent pediatric shock: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:238. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1365-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keh D, Boehnke T, Weber-Cartens S, et al. Immunologic and hemodynamic effects of “low-dose” hydrocortisone in septic shock: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:512–20. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200205-446OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:2–8. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149131.72248.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Averill RF, Mullin RL, Steinbeck BA, et al. Development of the ICD-10 procedure coding system (ICD-10-PCS) Top Health Inf Manage. 2001;21:54–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss SL, Parker B, Bullock ME, et al. Defining pediatric sepsis by different criteria: discrepancies in populations and implications for clinical practice. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:e219–e226. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31823c98da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss SL, Fitzgerald JC, Maffei FA, et al. Discordant identification of pediatric severe sepsis by research and clinical definitions in the SPROUT international point prevalence study. Crit Care. 2015;19:325. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1055-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menon K. Use of hydrocortisone for refractory shock in children. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:e294–e295. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828cf478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]