Abstract

Objective

We hypothesize that three inflammation pathobiology phenotypes are associated with increased inflammation, proclivity to develop features of Macrophage Activation Syndrome (MAS), and Multiple Organ Failure (MOF) related death in pediatric severe sepsis.

Design

Prospective cohort study comparing children with severe sepsis and any of three phenotypes; 1) Immune paralysis Associated MOF (whole blood ex vivo TNF response to endotoxin < 200 pg/mL), 2) Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF (new onset thrombocytopenia with acute kidney injury and ADAMTS13 activity < 57%), and / or 3) Sequential MOF with Hepatobiliary Dysfunction (respiratory distress followed by liver dysfunction with sFASL > 200 pg/mL), to those without any of these phenotypes.

Setting

Tertiary children's hospital pediatric intensive care unit.

Patients

One hundred consecutive severe sepsis admissions.

Interventions

Clinical data was recorded daily and blood was collected twice weekly.

Measurements and Main Results

Seventy five cases developed MOF and 8 died. MOF cases with any of the three inflammation phenotype(s) (n = 37) had higher inflammation (C-reactive protein p=0.009 and ferritin p<0.001) than MOF cases without any of these phenotypes (n = 38) or cases with only single organ failure (n = 25). Development of features of MAS and death were more common among MOF cases with any of the phenotypes (MAS 10/37, 27%; death 8/37, 22%) compared to MOF cases without any phenotype (MAS 1/38, 3%, p=0.003, death 0/38, 0%, p=0.002).

Conclusion

Our approach to phenotype categorization remains hypothetical and the phenotypes identified need to be confirmed in multicenter studies of pediatric MODS.

Keywords: Pediatric Sepsis, Immunoparalysis, Thrombocytopenia Associated Multiple Organ Failure, Sequential Multiple Organ Failure, Macrophage Activation Syndrome

Introduction

Severe sepsis remains a leading cause of death among children worldwide. Most children dying from sepsis in the resource rich setting do so with multiple organ failure (MOF).1,2 Present-day treatment is directed to removing the infection source and supporting organ dysfunction without addressing inflammation pathobiology. Nevertheless, three inflammation phenotypes related to abnormal immune and coagulation responses have been reported to respond to pathobiology targeted therapies.3–18 These inflammation pathobiology based phenotypes include 1) Immune paralysis Associated MOF,3–8 2) Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF,9–13 and 3) Sequential MOF with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction.14–18

Children with Immune paralysis syndrome have lymphoid organ depletion, prolonged reduction in innate and adaptive immune function, and an inability to clear bacterial or fungal infections. These children can be identified by a decreased ex vivo whole blood tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) response to endotoxin, decreased monocyte HLA-DR expression, or lymphopenia for more than three days.3,4 Immune function can be restored with immune modulation or immune suppressant tapering.4,7,19–27 Hyper-inflammation in this phenotype has been related to persistent infection and a decreased monocyte TNF response to endotoxin accompanied by an increased systemic interleukin(IL)-6 and IL-10 response. Reversal of Immune paralysis with immune suppressant tapering or GM-CSF therapy restores the monocyte TNF response to endotoxin while decreasing systemic inflammation measured by IL-6 and IL-10 levels.4

Children with Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF have reduced ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13) activity that contributes to inability to resolve von Willebrand Factor: platelet clots and ensuing thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), which can be reversed with plasma exchange therapy.9,13,28 Hyper-inflammation in these children has been associated with complement over-activation in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (TTP/aHUS) as well as necrosis related to microvascular thrombosis in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Eculizumab (C5a antibody) is an FDA approved drug for aHUS that reverses hyper-complementemia driven inflammation.29

Children with Sequential MOF with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction (respiratory followed several days later by liver dysfunction) have a proclivity to Natural Killer / Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte dysfunction with an inability to induce death of viruses, cancer cells, or activated immune cells. Viral infections in these children cause lympho-proliferation with soluble Fas ligand (sFasL) release, hemophagocytosis, and sFasL-mediated liver injury which can respond to varied treatment strategies.14–19,30,31 Hyper-inflammation in these children can be related to their inability to clear viral infections or to induce apoptosis of activated immune cells. Rituximab (CD20 antibody) is FDA approved to reverse post transplantation Epstein Barr Virus related lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) and to kill the virus by removing its reservoir.

The final common pathway of uncontrolled inflammation manifests as the Macrophage Activation Syndrome (MAS). Ravelli and colleagues define MAS in children with uncontrolled systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis by the development of a unique ‘hyper-inflammation’ MOF organ failure pattern which includes new onset hepatobiliary dysfunction, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and hyper-ferritinemia.32 When recognized early, these children respond well to anti-inflammatory strategies including IL-1 receptor antagonist protein (IL-1ra; Anakinra). We recently applied these clinical criteria post-hoc to adults with severe sepsis who had been enrolled in an IL-1 receptor blockade trial.33 Overall, 5.6% of the adults in this severe sepsis trial had features of MAS. Among these subjects, Anakinra increased survival two-fold from 34.3% with placebo to 65.4% with IL-1 blockade; whereas Anakinra had no effect on outcome in severe sepsis subjects without these three combined features of MAS.33

Adult patients are being actively recruited to participate in nine ongoing clinical trials of specific therapies targeting these three inflammation pathobiology phenotypes, and both adult and pediatric patients are being recruited into two additional trials targeting uncontrolled inflammation and MAS (Supplementary Table, Appendix). Before garnering any enthusiasm for investigating these personalized inflammation pathobiology based therapeutic approaches to improve MOF outcomes in pediatric sepsis, it is necessary to first assess whether these inflammation pathobiology phenotypes are associated with adverse outcomes in children with severe sepsis. We test the hypothesis that children with one or more of these inflammation pathobiology based phenotypes have more inflammation (indirectly indicated by higher C-reactive protein (CRP) and ferritin levels), with a greater proclivity to development of features of MAS, and a greater risk of MOF related death.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh – Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and UPMC Institutional Review Board (IRB). Patients were recruited and enrolled after obtaining informed consent from parent(s) at the University of Pittsburgh - Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC – one site of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (NICHD-CPCCRN). The study was planned, performed and analyzed during the second NICHD – CPCCRN cycle between the years 2009–2014. Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of severe sepsis (sepsis with at least one organ failure), an existing indwelling central venous and / or arterial catheters for blood draws, age ≥ 44 weeks gestation and < 18 years, and commitment to aggressive care.

The first 2 mL blood sample was obtained on the second day of severe sepsis from an indwelling arterial or central venous catheter at that time, and then twice weekly as long as the catheter was in place, to a maximum of 28 days in the PICU (maximum 8 samples for batch analysis). LPS-induced TNFα production capacity was measured as previously described.4 The remaining whole blood was spun down and the plasma was separated into aliquots and frozen at −80 °C for later batch analysis. The TNFα and sFasL assays were performed using ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). ADAMTS13 activity was measured by a commercial assay kit (Immucor GTI Diagnostics/Lifecodes Inc, Waukesha WI, USA; Immucor.com). Ferritin and C - reactive protein were measured in the CHP-UPMC clinical laboratory using the same standard operating procedure used for clinical specimens in our hospitals. The peak Ferritin and CRP sample level from the total number of samples was used for data analysis.

Sepsis was defined by the presence of two or more of the following four criteria: 1) tachycardia (heart rate > 90th percentile for age in absence of stimulation), 2) tachypnea (respiratory rate > 90th percentile for age), 3) abnormal temperature (< 36°C or > 38.5°C) and 4) abnormal white blood cell count (> 12,000 mm3 or < 4,000 mm3 or > 10% immature neutrophils), plus suspicion of infection (www.mdcalc.com/pediatric-sirs-sepsis-criteria). Organ failure was defined using the Organ Failure Index (OFI) criteria established by Doughty et al14 (Cardiovascular - need for cardiovascular agent infusion support, Pulmonary- need for mechanical ventilation support with the ratio of the arterial partial pressure of oxygen and the fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) < 300 without this support, Hepatic – total bilirubin > 1.0 mg/dL and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) > 100 units/L, Renal – serum creatinine > 1.0 mg/dL and oliguria (urine output < 0.5 mL/kg/hr), Hematologic - thrombocytopenia < 100,000/mm3 and prothrombin time INR > 1.5 × normal, and Central Nervous System – Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) < 12 in absence of sedatives). Severe Sepsis was defined by the presence of sepsis and one or more organ failures. Multiple Organ Failure was defined by the development of two or more organ failures. Immune paralysis Associated MOF,4 Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF,9 Sequential MOF with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction,14 and Macrophage Activation Syndrome,32,33 were defined by criteria in Table 1. Mortality was defined by death in the PICU (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and biomarker criteria used to define inflammation phenotypes and macrophage activation syndrome

| Group | Clinical criteria | Confirmatory Biomarker |

|---|---|---|

|

Immune paralysis Associated MOF (Immune depression) |

1)Beyond third day of critical illness with MOF |

Whole blood ex vivo TNF response to LPS < 200 pg/mL |

|

Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF (Thrombotic Micro- angiopathy) |

1)New thrombocytopenia < 100 K, or if baseline platelet count < 100 K then 50% decrease from baseline 2)Elevated LDH > 250 u/L 3)Creatinine >1 mg/dL and oliguria |

ADAMTS 13 activity < 57% of control |

|

Sequential MOF with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction (Virus / lympho- proliferative disease disease) |

1) PaO2/FiO2 < 300 with need for mechanical ventilation 2) Followed days later by new onset hepatic dysfunction ALT > 100u/L + Bilirubin > 1 mg/dL |

sFasL > 200 pg/mL |

|

Macrophage Activation Syndrome (Hyperinflammation common end pathway) |

1)Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation with Platelet count < 100 K and INR > 1.5 2) New hepatic dysfunction ALT>100 u/L + Bilirubin > 1 mg/dL |

Ferritin > 500 ng/mL |

MOF = multiple organ failure; LPS = lipopolysaccharide; pg = picogram; mg = milligram; L = liter; mL = milliliter; dL = deciliter; u = unit; K = 1,000; ADAMTS 13 = a disintegrin an dmetalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; PaO2 = partial pressure of oxygen; FiO2 = fractional inspired oxygen; ALT = Alanine Amino transferase; sFasL = soluble FAS ligand; ng = nanogram; INR = international normalized ratio

Associations between each inflammation phenotype and admission epidemiology characteristics (age, gender, chronic illness, cancer status, transplantation status) and infection status (bacterial, viral, fungal, culture negative) were evaluated using Fisher’s exact test or two sided Wilcoxon rank-sum with normal approximation and continuity correction. The Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney rank-sum test with two-sided alternative was used to compare CRP and ferritin concentrations between groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the development of MAS and mortality between groups. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A secondary analysis was performed excluding the four patients who were admitted twice in the study.

Results

Ninety-six patients comprised 100 consecutive PICU severe sepsis cases. The average age of the children was 5.8 years (standard deviation (SD) = 5.7). There were 47 female and 53 male cases. Fifty-nine percent of cases had a chronic illness (14 cancer, 25 solid organ or hematopoietic transplant, 20 other) and 41% were previously healthy. Seventy-five of the cases were culture positive (57 bacterial, 23 viral, 9 fungal) and 25 were culture negative. The average PRISM score was 10.7 (SD = 8.7). The average number of maximum organ failures was 2.4 (SD = 1.3). The average number of blood sampling study days was 10.2 (SD = 7.9) with an average of three blood samples attained per case.

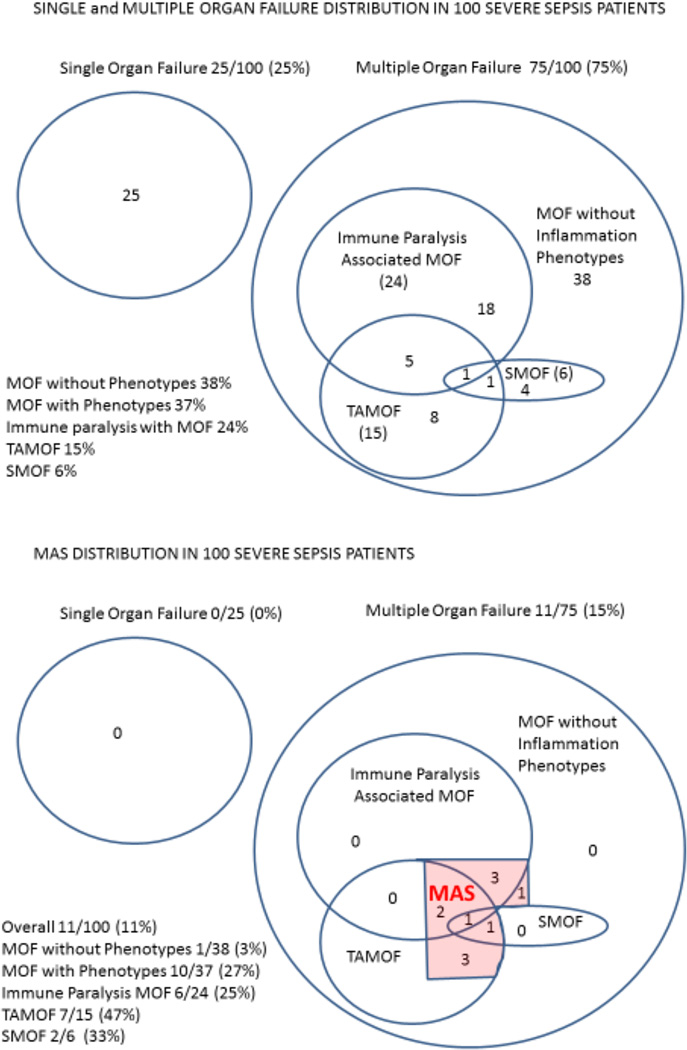

Among the 100 cases of severe sepsis, 25 had single organ failure, 38 developed MOF without any of the three inflammation phenotypes (mean OFI = 2.3, SD = 0.5) and 37 developed MOF with one or more inflammation phenotypes (mean OFI = 3.4, SD = 1.4). In the 37 cases with MOF and one or more inflammation phenotypes the distribution was 24/37 Immune paralysis associated MOF, 15/37 Thrombocytopenia associated MOF and 6/37 Sequential MOF (Figure 1, top panel). Thirty of these 37 had one distinct phenotype, 6/37 had two phenotypes overlapping, and 1/37 had three phenotypes overlapping.

Figure 1. Distribution of single organ failure, multiple organ failure with and without inflammation phenotypes, and macrophage activation syndrome in the severe sepsis population.

Nearly one half of MOF patients had one or more of the three inflammation phenotypes (Top panel). Macrophage Activation Syndrome (MAS) was more commonly found in MOF patients with the inflammation phenotypes (10/37) than MOF patients without any of the inflammation phenotypes (1/38); Fisher’s exact test p = 0.003 (Bottom Panel). Single organ failure (SOF); Multiple organ failure (MOF); Immune paralysis Associated MOF (IP MOF); Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF (TAMOF); Sequential MOF (SMOF); Macrophage Activation Syndrome (MAS)

In univariate analysis the only significant associations between any of the three inflammation phenotypes and age, gender, chronic illness, cancer, transplantation or infection type status was found in the Immune paralysis associated MOF phenotype (Table 2). Immune paralysis associated MOF was more likely to be observed in cases with increased age (7.8 years +/− 5.97 vs 5.2 years +/− 5.49 mean +/− SD; p < 0.05), chronic illness (20/59; 34% with chronic illness vs 4/41; 10% without; p < 0.05), or cancer (10/14; 71% with cancer vs 14/86; 16% without; p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of each inflammation phenotype

| Baseline Status |

IPMOF | TAMOF | SMOF/ Hepatobiliary Dysfunction |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| N = 76 | N=24 | N = 85 | N = 15 | N = 94 | N = 96 | |

| Age | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.2 (5.49) | 7.8 (5.97)a | 5.5 (5.66) | 7.7 (5.73) | 5.9 (5.82) | 4.2 (3.02) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 38 (50.0%) | 9 (38%) | 40 (47%) | 7 (47%) | 45 (48%) | 2 (33%) |

| Male | 38 (50.0%) | 15 (62%) | 45 (53%) | 8 (53%) | 49 (52%) | 4 (67%) |

| Bacteria | ||||||

| No | 34 (45%) | 9 (38%) | 38 (45%) | 5 (33%) | 40 (43%) | 3 (50%) |

| Yes | 42 (55%) | 15 (62%) | 57 (55%) | 10 (67%) | 54 (57%) | 3 (50%) |

| Virus | ||||||

| No | 58 (76%) | 19 (79%) | 65 (77%) | 12 (80%) | 72 (77%) | 5 (83%) |

| Yes | 18 (24%) | 5 (21%) | 20 (24%) | 3 (20%) | 22 (23%) | 1 (17%) |

| Fungus | ||||||

| No | 69(91%) | 22 (92%) | 76 (89%) | 15 (100%) | 86 (92%) | 5 (83%) |

| Yes | 7 (9%) | 2 (8%) | 9 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (8%) | 1 (17%) |

| Chronic Ill | ||||||

| No | 37(49%) | 4 (17%) | 37 (44%) | 4 (27%) | 39 (42%) | 2 (33%) |

| Yes | 39 (51%) | 20(83%)b | 48 (56%) | 11 (73%) | 55 (59%) | 4 (67%) |

| Cancer | ||||||

| No | 72 (95%) | 14 (58%) | 73 (86%) | 13 (87%) | 81 (86%) | 5 (83%) |

| Yes | 4 (5%) | 10 (42%)c | 12 (14%) | 2 (13%) | 13 (14%) | 1 (17%) |

| Transplant | ||||||

| No | 59 (78%) | 16 (67%) | 64 (75%) | 11 (73%) | 70 (75%) | 5 (83%) |

| Yes | 17 (22%) | 8 (33%) | 21 (25%) | 4 (27%) | 24 (26%) | 1 (17%) |

Two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum with normal approximation and continuity correlation

p-value = 0.044;

Fishers exact test

p-value = 0.008,

p-value < 0.001; p values based on comparing those in group to those not in the group.

IP - Immune Paralysis; MOF – multiple organ failure; TAMOF – Thrombocytopenia associated MOF; SMOF – Sequential MOF; Chronic Ill – chronic illness at admission.

Compared to Absolute Lymphocyte Count (ALC) < 1,000/ uL, a low ex vivo TNF production was associated with longer length of stay (Length of Stay - ALC < 1,000: Coefficient = −1.5211, Standard Error = 1.8112, t = −0.84, p value = 0.403, 95% Confidence Interval = −5.1160 – 2.07367; Low ex vivo TNF – Coefficient = 5.9973, Standard Error = 1.9814, t = 3.03, p value = 0.03, 95% Confidence Interval = 2.0646 – 9.9301) and a non-significant tendency towards increased mortality (Mortality – ALC < 1,000: Coefficient = .5888, Standard Error = .8841, z = 0.67, p value = 0.505, 95% Confidence interval = −1.1441 – 2.3218; Low ex vivo TNF – Coefficient = 1.5018, Standard Error = .8807, z = 1.71, p value = 0.088, 95% Confidence Interval = −.2244 – 3.2281).

Overall, cases with MOF and one or more inflammation phenotype had higher peak CRP (p = 0.009) and peak ferritin levels (p < 0.001) than cases of MOF without any phenotype, or cases with single organ failure (Table 3). Peak ferritin levels were higher in cases with Immune paralysis Associated MOF (p < 0.05), Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF (p < 0.05), or Sequential MOF with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction (p > 0.05) compared to cases of MOF without any of these inflammation phenotypes (Table 3). Peak CRP levels were higher in cases with Immune paralysis Associated MOF (p < 0.05) or Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF (p < 0.05), but not in cases with Sequential MOF compared to cases with MOF without any of the phenotypes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Peak ferritin and CRP levels for single organ failure, multiple organ failure with and without inflammation phenotypes, and each MOF inflammation phenotype.

| Organ Failure Status |

Statistic | Peak Ferritin ng/mL | Peak CRP mg/dL |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Single Organ Failure (n = 25) |

Min, Max | 40, 2470 | 0.2, 27.9 |

| Median | 200 | 3.0 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 120, 420 | 1.5, 6.0 | |

| Mean (SD) | 406 (537) | 5.6 (6.6) | |

|

MOF without Inflammation Phenotypes (n = 38) |

Min, Max | 30, 6100 | 0.2, 30.1 |

| Median | 185 | 5.1 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 100, 360 | 1.8, 11.2 | |

| Mean (SD) | 550 (1180) | 7.9 (8.0) | |

|

MOF with Inflammation Phenotypes (n = 37) |

Min, Max | 50, 48820 | 0.2, 51.8 |

| Median | 670 | 10.6 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 240, 2610 | 3.6, 21.7 | |

| Mean (SD) | 3655 (8654) | 13.6 (12.5) | |

| p-value | < 0.001 | 0.009 | |

| IP MOF (n = 24) | Min, Max | 50, 48820 | 0.3, 51.8 |

| Median | 885 | 13.4 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 285, 3205 | 3.0, 22.6 | |

| Mean (SD) | 4743 (10501) | 15.8 (14.1) | |

| p-value | < 0.001 | 0.015 | |

| TAMOF (n = 15) | Min, Max | 50, 48820 | 0.5, 51.8 |

| Median | 1100 | 15.0 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 390, 4770 | 4.1, 26.2 | |

| Mean (SD) | 5868 (12510) | 17.4 (15.3) | |

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.017 | |

|

SMOF with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction (n = 6) |

Min, Max | 130, 48,820 | 0.2, 11.9 |

| Median | 1025 | 4.7 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 150, 8930 | 3.6, 7.3 | |

| Mean (SD) | 10013 (19310) | 5.4 (3.9) | |

| p-value | 0.223 | 0.597 | |

ng = nanogram; mg = milligram; mL = milliliter; dL = deciliter; CRP = C-reactive protein; MOF = multiple organ failure; Min = minimum value; Max = maximum value; Q1, Q3 = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation; IP MOF = Immunoparalysis associated MOF; TAMOF = Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF; SMOF = Sequential MOF.

P-values are based on a Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test comparing those in the group to those that are not in the group

Macrophage Activation Syndrome occurred in 11 cases (11%) overall and was more common in the MOF population with one or more of the phenotypes (10/37 cases) compared to the MOF population without the phenotypes (1/38 cases) (p = 0.003). Of the 11 cases with MAS, 6 had Immune paralysis Associated MOF, 7 had Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF, and 2 had Sequential MOF (Figure 1, Bottom Panel). These 11 cases occurred in eleven different children.

There were eight deaths (8%). The presence of an Inflammation Phenotype was independently associated with outcome whereas PRISM III illness severity was not (PRISM: coefficient = .0026, Standard Error = .0033, t = 0.80, P value 0.423, 95% confidence interval = −.0039 – .0092; an Inflammation Phenotype: coefficient .1908, Standard Error = .0578, t = 3.30, p value = 0.001, 95% confidence interval = .0760 –.3056). As compared to PRISM III the presence of an Inflammation Phenotype was also associated with increased length of stay (Length of Stay - PRISM: Coefficient = .0260, Standard Error = .0942, t = −0.28, p value = 0.783, 95% Confidence Interval = −.2130 – .16105; an Inflammation Phenotype: Coefficient = 6.8936, Standard Error = 1.6487, t = 4.18, p < 0.001, 95% Confidence Interval = 3.6214 – 10.1659).

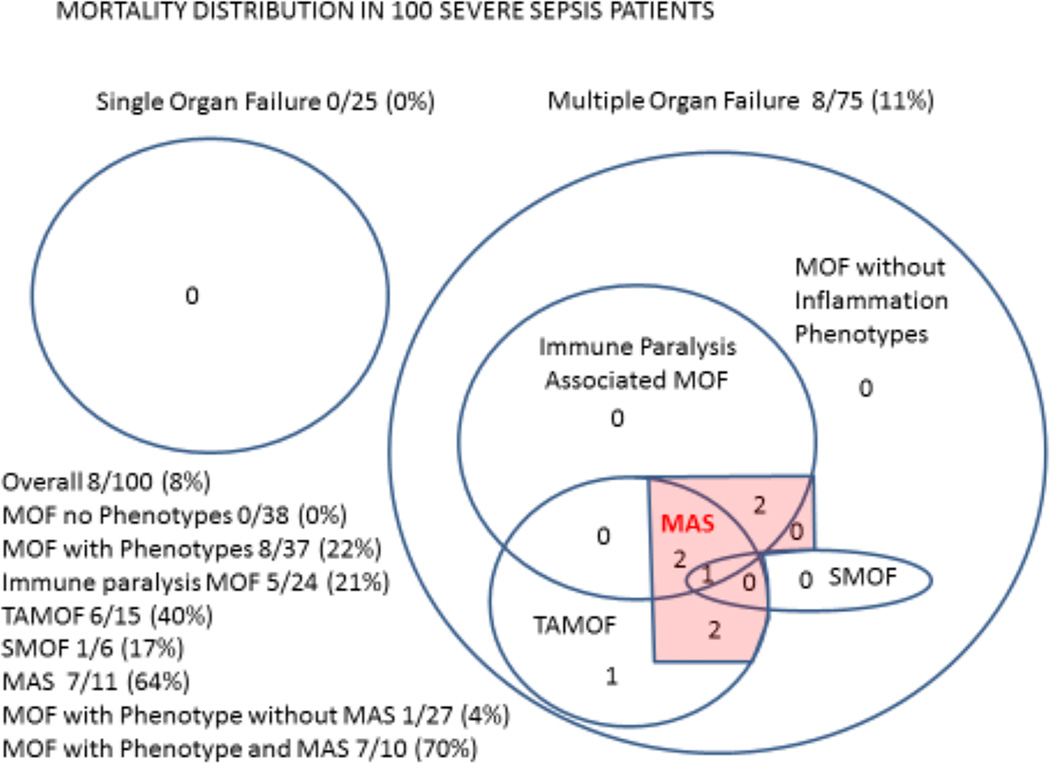

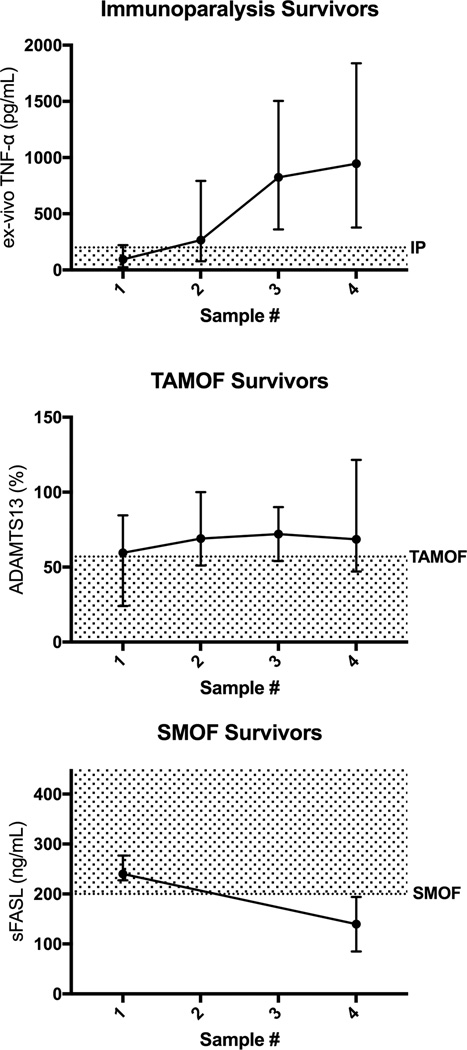

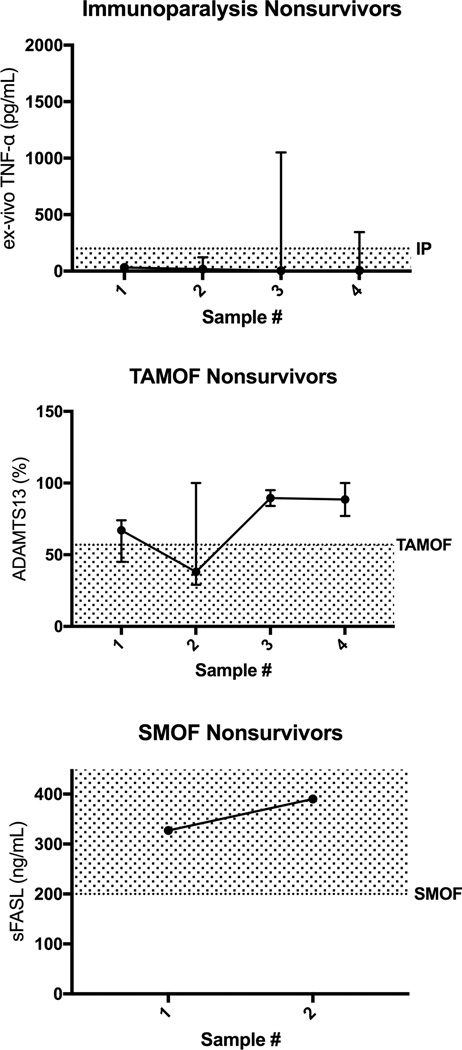

All the deaths occurred among cases who developed MOF with one or more of the phenotypes, with all but one death observed in the presence of unresolving MAS. Mortality rates were higher in cases with MOF and one or more inflammation phenotype compared to cases with MOF without any phenotype (8/37 vs 0/38; Figure 2, p = 0.002). In cases that developed MAS, mortality occurred in 64% (7/11) compared to 1% (1/89) of cases without MAS (Figure 2; p < 0.001). Among the cases of MOF with one or more inflammation phenotype and MAS mortality was 70% (7/10), compared to 4% (1/27) of MOF cases with one or more inflammation phenotype without MAS (Figure 2; p < 0.001). Figures 3 and 4 show the relationships between the confirmatory biomarkers in each pathobiology phenotype in survivors and non-survivors over the first 4 samplings. Figure 5 (supplementary) shows three representative patients who resolved their isolated inflammation pathobiology phenotype and did not succumb to MAS. Figure 6 (supplementary) shows two representative patients who experienced worsening of their inflammation pathobiology phenotype(s) and subsequently succumbed with MAS.

Figure 2. Mortality distribution in the severe sepsis population.

All mortality occurred among MOF cases with one or more of the inflammation phenotypes (Fisher’s exact test - MOF with phenotypes 8/37, 28% vs MOF without phenotypes 0/38, 0%; p = 0.002) and was highest among those who developed MAS (Fisher’s exact test - MOF with inflammation phenotypes and MAS 7/10, 70% vs MOF with inflammation phenotypes without MAS 1/27, 4%; p < 0.001). SOF= Single Organ Failure; MOF = Multiple Organ Failure TAMOF = Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF; SMOF = Sequential MOF; IP MOF = Immune paralysis Associated MOF; MAS = Macrophage Activation Syndrome

Figure 3. First four time point (Days 2 through 12) confirmatory biomarker levels for survivors with each inflammation pathobiology phenotype (ex vivo TNF response pg/mL, ADAMTS13 activity % of control, and sFASL pg/mL median with 5th and 95th percentile).

GM-CSF administration and withdrawal of immune suppressants occurred in 8 of 19 Immune Paralysis survivors. Plasma exchange was given to 6 of 9 TAMOF survivors. No patients received Anakinra, Eculizumab, Rituximab, or Etoposide.

Figure 4. First four time point (Days 2 through 12) confirmatory biomarker levels for non-survivors with the inflammation pathobiology phenotypes (ex vivo TNF response pg/mL, ADAMTS13 activity % of control, and sFASL pg/mL median with 5th and 95th percentile).

GM-CSF administration and withdrawal of immune suppressants occurred in 0 of 5 Immune Paralysis non-survivors. Plasma exchange was given to 4 of 6 TAMOF non-survivors. No patients received Anakinra, Eculizumab, Rituximab, or Etoposide.

Two previously healthy patients died in the study (2/41 cases = 5% case mortality rate). Patient 1 developed Pertussis and Streptococcus Pneumoniae pneumonia and died with unremitting TAMOF and MAS. Patient 2 developed Staphylococcus Aureus and Penicillium pneumonia and died with unremitting Immune paralysis, TAMOF, and MAS. Six chronically ill children also died (6/59 cases = 10% case mortality rate). Patient 3 had acute on chronic hemorrhagic pancreatitis and died with unremitting TAMOF without MAS. Patient 4 had pre B cell leukemia and neutropenia with Alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus and Candida septicemia and died with unremitting Immune paralysis and MAS. Patient 5 had AML and aplastic anemia with Enterococcus and Stenotrophomonas pneumonia and died with unremitting Immune paralysis, TAMOF, and MAS. Patient 6 had ALL and neutropenia with Escherichia coli septicemia and died with unremitting Immune paralysis and MAS. Patient 7 had an orthotopic liver transplant with Adenovirus, EBV, and VRE septicemia and died with unremitting Immune paralysis, SMOF, TAMOF, and MAS. Patient 8 had a small bowel transplant with graft versus host disease and MRSA and VRE septicemia and died with unremitting TAMOF, and MAS.

Discussion

In our population sample, one or more of the inflammation pathobiology phenotypes were observed in one out of three severe sepsis cases overall, and one of two cases of sepsis-induced MOF. The children with one or more of these phenotype(s) had more systemic inflammation, and an increased proclivity to develop features of MAS and death compared to those without any of the phenotypes.

Conditions such as severe sepsis can lead to release of DAMPS (damage associated molecular patterns) and PAMPS (pathogen associated molecular patterns) that contribute to exaggerated inflammation. This induces endotheliopathy with microvascular thrombosis, epithelial cell dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction with mitophagy and mitochondrial dysoxia, and apoptosis of lymphocytes with depression of monocyte / macrophage function, all of which result in Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome/MOF. In addition to providing immediate organ support therapies to keep the patient alive, the clinician must also remove the source of inflammation for MOF to resolve. This includes use of proper antimicrobials and surgical source control. In theory, removal of the source of inflammation facilitates improved organ function as microvascular thrombosis resolves and endothelium regenerates, lymphocyte apoptosis stops and innate immune function recovers, epithelial cells regenerate and lung and hepatobiliary function recovers, and mitogenesis restores metabolic homeostasis.

The tenet of our present investigation is that there are pathobiology driven subsets of patients with decreased ability to control inflammation and resolve MOF, who can be recognized by clinical phenotypes and confirmed by specific biomarkers, for whom therapies directed to respective inflammation pathobiology might facilitate control of inflammation and reversal of MOF. Before testing this unproven hypothesis in clinical trials, it is first necessary to determine whether pathobiology driven subsets are associated with adverse outcomes in septic children.

Immune paralysis, is defined by immune depression beyond three days, and was observed in 24% of our severe sepsis population sample with 21% mortality. Similar to adults, it was found in association with older age, chronic illness or cancer. Treatments including radiation, dexamethasone, chemotherapy, and other immune suppressants can induce this phenotype, leading some investigators to suggest tapering immune suppressants when Immune paralysis occurs.19–23 In a series of small studies, GM-CSF has been found to reverse Immune paralysis, improve seven day cure rates, and reduce secondary infections in adult patients with sepsis.4,24–27 The epidemiologic relevance of this sepsis phenotype in children has been corroborated by a multiple center study during the H1N1 influenza A epidemic which demonstrated that Staphylococcus aureus co-infection and death was associated with a low ex vivo TNFα response to LPS stimulation with a receiver operating characteristics area under the curve equal to 0.97.8 In addition to this functional biomarker,4 lymphopenia3 and decreased monocyte HLA-DR expression4 are also being used to define this phenotype in ongoing adult clinical trials (Supplementary Table, Appendix).

Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF occurs at any time in the PICU. It was observed in 15% of our severe sepsis cases with a mortality rate of 40%. Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation, aHUS / TMA, and TTP represent the full spectrum of this phenotype.9–13 Therapeutic plasma exchange restores ADAMTS13 levels, removes ultra large vWF multimers, reverses thrombotic microangiopathy, and improves outcomes in adult patients with DIC, aHUS/ TMA, and TTP.28,34,35. Multiple mutations in the inhibitory component of complement, particularly complement H, have been found to contribute to over activation of complement and coagulation in aHUS/TMA leading to use of the C5A monoclonal antibody (eculizumab) as well as plasma exchange therapy in clinical practice in adults and children.29 None of the TAMOF patients in our study received Eculizumab.

The Sequential MOF phenotype with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction was observed in 6% of our severe sepsis cases making it the least common inflammation pathobiology. Cases with this phenotype had a mortality of 17%. The Sequential MOF with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction phenotype is diagnosed when respiratory distress is followed several days later by the development of liver dysfunction, and is confirmed by circulating sFasL levels > 200 pg/mL.14 In vitro, sFasL induces liver cell apoptosis / necrosis at concentrations > 500 pg/mL.17,18 This phenotype has been associated with several disorders including virus associated hemophagocytosis and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease. Virus associated hemophagocytosis can be treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), methylprednisolone, and anti-viral therapies. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease can be treated with immune suppressant tapering, anti-viral medication and administration of rituximab (CD20 / B-cell antibody) to destroy the EBV reservoir, followed by IVIG for hypogammaglobulinemia.30,31 There was only child with PTLD in our study and she was not treated with Rituximab.

Features of Macrophage Activation Syndrome occurred in 11% of our severe sepsis patients in strong association with the presence of one or more of the three inflammation phenotypes. The 64% mortality rate observed in our pediatric MAS subset is similar to the 65.7% mortality we reported in a placebo treated adult severe sepsis subset with features of MAS.33 Mortality in this adult severe sepsis MAS subset was reduced to 34.6% with IL-1 receptor blockade treatment.33 The IL-1 receptor antagonist has also been reported to be effective in reversing MAS in a small non-randomized case series of critically ill children with MOF.36 Demirkol and colleagues reported that children with 5 and 6 organ failure MAS attained 100% survival when treated with daily plasma exchange and a regimen of IVIG and / or methylprednisolone compared to only 50% survival when treated with a more immune suppressive regimen that included dexamethasone, etoposide, or other chemotherapy.37 None of the children with MAS in our study received Anakinra or the IVIG / Methylprednisone therapeutic strategy.

There are several limitations in our study. First, our decision to enroll on the second day of severe sepsis enriched sampling of patients who developed MOF because patients who improve severe sepsis by day two rarely develop MOF. Second, the phenotypes and biomarkers tracked in our study must be considered in relation to others published in the literature. Using unbiased methodology Knox and colleagues defined four phenotypes in adult sepsis induced MODS38 including one phenotype with increased creatinine, and another phenotype with liver disease. It remains unknown whether these two phenotypes overlap in any way with the TAMOF and SMOF with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction phenotypes, respectively. Wong and colleagues described a pediatric septic shock subclass with depressed adaptive immune and glucocorticoid signaling gene expression.39 It also remains unknown whether this subclass overlaps in any way with the Immune paralysis phenotype. These same investigators recently used their unbiased PERSERVERE biomarkers to identify pediatric septic shock TAMOF patients with the highest mortality risk, and then developed a new predictive model to be used for patient stratification in future plasma exchange clinical trials in the TAMOF phenotype.40 Compared to the biomarkers used by Wong and colleagues, our biomarkers are very basic and generic. Third, our decision to enroll consecutive cases rather than exclude children who had previous hospitalizations for severe sepsis led to four children being analyzed in two separate hospital stays. The statistical results remained similar when eliminating the second admission, as to when including the second admission of these children. Fourth, it is important to emphasize that we do not hold that the presence of these ‘inflammation phenotypes’ in children with sepsis means that therapies being trialed for diseases/symptoms that have a primary inflammation etiology should be applied to patients with sepsis who have a similar inflammatory response to infection without appropriate evaluation in clinical sepsis trials. We do not claim that children with sepsis and features of PTLD will benefit from Rituximab, or that children with sepsis and features of aHUS will benefit from Eculizumab, or that children with sepsis and features of TTP will benefit from plasma exchange, or that children with sepsis and features of MAS will benefit from Anakinra. Instead we raise the question whether future multiple center trials might be considered to address these research possibilities.

Conclusion

In summary, we present proof of concept that during severe sepsis, children with one or more of three hypothetical inflammation pathobiology phenotypes have higher peak levels of very basic and generic biomarkers of systemic inflammation, with increased proclivity to develop features of MAS and death. Because our approach to phenotype categorization remains hypothetical, the phenotypes identified need to be confirmed in multicenter studies of pediatric MODS.

Supplementary Material

Top panel - 10 year old with typhilitis, lymphoma, and 5 organ failure recovered from MAS when immunoparalysis resolved with G/GM-CSF and immune suppressant tapering (TNF α response to LPS recovered to > 200 pg/mL). Middle panel - 4 year old multi-visceral transplant with gram negative sepsis and 3 organ failure who recovered without developing MAS when Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF resolved during plasma exchange (ADAMTS 13 increased above 57% of control). Bottom panel - 9 year old with 6 organ failure culture negative sepsis who recovered from MAS when Sequential MOF with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction resolved during plasma exchange (sFASL decreased to < 200 pg/mL).

Top panel - 7 year old with liver transplantation and adenovirus and gram negative sepsis with EBV post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease and 5 organ failure who did not resolve SMOF with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction (sFASL persistently > 200 pg/mL) or TAMOF (ADAMTS 13 persistently < 57%). Bottom panel - 3 year old with ALL and e.coli sepsis with 5 organ failure who did not resolve Immune paralysis (ex vivo TNF response persistently < 200 pg/mL).

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the contributions of Mr. Luther Springs and Ms. Jennifer Jones RN, BSN. Samples were collected, processed and analyzed with technical support provided by Mr. Luther Springs. Clinical data was collected by Ms. Jennifer Jones RN, BSN.

All funding was paid to the institution sand not to the investigators. The funding included the following. The study was supported, in part, by R01GM108618 (JAC) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The study was also funded in part by the following cooperative agreements from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services: U10HD049983, U10HD050096, U10HD049981, U10HD063108, U10HD063106, U10HD063114, U10HD050012 and U01HD049934. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network investigators Jeri Burr MS, RN-BC, CCRN; Allan Doctor, MD; Christopher JL Newth MD FRCPC; David L Wessel MD; Kathleen L Meert MD; J Michael Dean MD; Murray Pollack MD; Robert A Berg MD; Thomas Shanley MD; Rick Harrison MD; Richard Holubkov PhD; Tammara L Jenkins MSN RN, PCNS-BC, and Robert F Tamburro MD. University of Utah and Department of Pediatrics (Dr. Dean, Ms. Burr, Dr. Holubkov); St. Louis Children’s Hospital and Washington University Department of Pediatrics (Dr. Doctor); Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and University of Southern California Department of Pediatrics (Dr. Newth); Children’s National Medical Center and George Washington University Department of Pediatrics (Dr. Wessel); Children’s Hospital of Michigan and Wayne State University Department of Pediatrics (Dr. Meert); Phoenix Children’s Hospital (Dr. Pollack); Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and University of Pennsylvania Department of Anesthesiology (Dr. Berg); C. S. Mott Children’s Hospital and University of Michigan Department of Pediatrics (Dr. Shanley); Mattel Children’s Hospital and University of California Los Angeles Department of Pediatrics (Dr. Harrison); and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Dr. Tamburro and Ms. Jenkins).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Financial Support: There are no conflicts of interest declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Watson RS, Carcillo JA, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. The epidemiology of severe sepsis in children in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(5):695–701. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-682OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Typpo KV, Petersen NJ, Hallman DM, et al. Day 1 multiple organ dysfunction syndrome is associated with poor functional outcome and mortality in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10(5):562–570. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181a64be1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felmet KA, Hall MW, Clark RS, et al. Prolonged lymphopenia, lymphoid depletion, and hypoprolactinemia in children with nosocomial sepsis and multiple organ failure. J Immunol. 2005;174(6):3765–3772. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall MW, Knatz NL, Vetterly C, et al. Immunoparalysis and nosocomial infection in children with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(3):525–532. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2088-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volk HD, Reinke P, Döcke WD. Clinical aspects: from systemic inflammation to 'immunoparalysis'. Chem Immunol. 2000;74:162–177. doi: 10.1159/000058753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters M, Petros A, Dixon G, et al. Acquired immunoparalysis in paediatric intensive care: prospective observational study. BMJ. 1999;319(7210):609–610. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7210.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotchkiss RS, Opal S. Immunotherapy for sepsis--a new approach against an ancient foe. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):87–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1004371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall MW, Geyer SM, Guo CY, et al. Innate immune function and mortality in critically ill children with influenza: a multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):224–236. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318267633c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen TC, Han YY, Kiss JE, et al. Intensive plasma exchange increases a disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin motifs-13 activity and reverses organ dysfunction in children with thrombocytopenia-associated multiple organ failure. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(10):2878–2887. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e318186aa49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bongers TN, Emonts M, de Maat MP, et al. Reduced ADAMTS13 in children with severe meningococcal sepsis is associated with severity and outcome. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103(6):1181–1187. doi: 10.1160/TH09-06-0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen TC, Liu A, Liu L, et al. Acquired ADAMTS13 deficiency in pediatric patients with severe sepsis. Haematologica. 2007;92(1):121–124. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin K, Borgel D, Lerolle N, et al. Decreased ADAMTS13 (A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type 1 repeats) is associated with a poor prognosis in sepsis-induced organ failure. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(10):2375–2382. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000284508.05247.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darmon M, Azoulay E, Thiery G, et al. Time course of organ dysfunction in thrombotic microangiopathy patients receiving either plasma perfusion or plasma exchange. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(8):2127–2133. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000227659.14644.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doughty L, Clark RS, Kaplan SS, et al. sFas and sFas ligand and pediatric sepsis-induced multiple organ failure syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2002;52(6):922–927. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200212000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halstead ES, Carcillo JA, Schilling B, et al. Reduced frequency of CD56dim CD16pos natural killer (NK) cells in pediatric systemic inflammatory response syndrome / sepsis patients. Pediatr Res. 2013;74(4):427–432. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakae H, Narita K, Endo S. Soluble Fas and soluble Fas ligand levels in patients with acute hepatic failure. J Crit Care. 2001;16(2):59–63. doi: 10.1053/jcrc.2001.25470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasegawa D, Kojima S, Tatsumi E, et al. Elevation of the serum Fas ligand in patients with hemophagocytic syndrome and Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Blood. 1998;91(8):2793–2799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryo K, Kamogawa Y, Ikeda I, et al. Significance of Fas antigen-mediated apoptosis in human fulminant hepatic failure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(8):2047–2055. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurwitz M, Desai DM, Cox KL, et al. Complete immunosuppressive withdrawal as a uniform approach to post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease in pediatric liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2004;8(3):267–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2004.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurwitz CA, Silverman LB, Schorin MA, et al. Substituting dexamethasone for prednisone complicates remission induction in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2000;88(8):1964–1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potenza L, Barozzi P, Codeluppi M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus associated pneumonia in an adult patient with severe aplastic anaemia: resolution after the transient withdrawal of cyclosporine. Am J Hematol. 2007;82(10):944–946. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brennan DC, Agha I, Bohl DL, et al. Incidence of BK with tacrolimus versus cyclosporine and impact of preemptive immunosuppression reduction. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(3):582–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00742.x. Erratum in Am J Transplant. 2005; 5(4 Pt 1) 839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massarollo PC, Mies S, Abdala E, et al. Immunosuppression withdrawal for treatment of severe infections in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1998;30(4):1472–1474. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meisel C, Schefold JC, Pschowski R, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to reverse sepsis-associated immunosuppression: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(7):640–648. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0363OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson LA. Use of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to reverse anergy in otherwise immunologically healthy children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98(4):373–382. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60885-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orozco H, Arch J, Medina-Franco H, et al. Molgramostim (GM-CSF) associated with antibiotic treatment in nontraumatic abdominal sepsis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Surg. 2006;141(2):150–153. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.2.150. discussion 154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenbloom AJ, Linden PK, Dorrance A, et al. Effect of granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor therapy on leukocyte function and clearance of serious infection in nonneutropenic patients. Chest. 2005;127(6):2139–2150. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sevketoglu E, Yildizdas D, Horoz OO, et al. Use of therapeutic plasma exchange in children with thrombocytopenia-associated multiple organ failure in the Turkish thrombocytopenia-associated multiple organ failure network. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014 Oct;15(8):e354–e359. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, et al. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2169–2181. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Végső G, Hajdu M, Sebestyén A. Lymphoproliferative disorders after solid organ transplantation-classification, incidence, risk factors, early detection and treatment options. Pathol Oncol Res. 2011;17(3):443–454. doi: 10.1007/s12253-010-9329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartmann C, Schuchmann M, Zimmermann T. Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease in liver transplant patients. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2011;13(1):53–59. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minoia F1, Davì S, Horne A, et al. Clinical features, treatment, and outcome of macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a multinational, multicenter study of 362 patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Nov;66(11):3160–3169. doi: 10.1002/art.38802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shakoory B, Carcillo J, Zhao H, et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist improves mortality in severe sepsis subset with features of Macrophage Activation Syndrome syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2016 Feb;44(2):275–281. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA, et al. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Canadian Apheresis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991 Aug 8;325(6):393–397. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108083250604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Busund R, Koukline V, Utrobin U, et al. Plasmapheresis in severe sepsis and septic shock: a prospective, randomised, controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2002 Oct;28(10):1434–1439. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1410-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajasekaran S, Kruse K, Kovey K, et al. Therapeutic role of anakinra, an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, in the management of secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis / sepsis/multiple organ dysfunction/macrophage activating syndrome in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(5):401–408. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Demirkol D, Yildizdas D, Bayaracki B, et al. Hyperferritinemia in the critically ill child with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/sepsis/multiple organ dysfunction syndrome/macrophage activation syndrome: what is the treatment? Crit Care. 2012 Dec 12;16(2):R52. doi: 10.1186/cc11256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knox DB, Lanspa MJ, Kuttler KG, et al. Phenotypic clusters within sepsis-associated multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2015 May;41(5):814–822. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3764-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Allen GL, et al. Validation of a gene expression-based subclassification strategy for pediatric septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2011 Nov;39(11):2501–2507. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182257675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Anas N, et al. Pediatric Sepsis Biomarker Risk Model-II: Redefining the Pediatric Sepsis Biomarker Risk Model With Septic Shock Phenotype. Crit Care Med. 2016 Nov;44(11):2010–2017. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Top panel - 10 year old with typhilitis, lymphoma, and 5 organ failure recovered from MAS when immunoparalysis resolved with G/GM-CSF and immune suppressant tapering (TNF α response to LPS recovered to > 200 pg/mL). Middle panel - 4 year old multi-visceral transplant with gram negative sepsis and 3 organ failure who recovered without developing MAS when Thrombocytopenia Associated MOF resolved during plasma exchange (ADAMTS 13 increased above 57% of control). Bottom panel - 9 year old with 6 organ failure culture negative sepsis who recovered from MAS when Sequential MOF with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction resolved during plasma exchange (sFASL decreased to < 200 pg/mL).

Top panel - 7 year old with liver transplantation and adenovirus and gram negative sepsis with EBV post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease and 5 organ failure who did not resolve SMOF with new Hepatobiliary Dysfunction (sFASL persistently > 200 pg/mL) or TAMOF (ADAMTS 13 persistently < 57%). Bottom panel - 3 year old with ALL and e.coli sepsis with 5 organ failure who did not resolve Immune paralysis (ex vivo TNF response persistently < 200 pg/mL).