Abstract

Background

Although data about the effect of posture on routine hematological testing were published 28 years ago, this pre-analytical issue has not been standardized so far. This study was planned to evaluate whether postural changes influence the results of hematology testing.

Methods

A complete blood count was performed in 19 healthy volunteers after 25 min in the supine position, 20 min in a sitting position and 20 min stationary standing in an upright position.

Results

The change from supine to sitting position caused clinically significant increases in the hemoglobin, hematocrit and red blood cell count. Furthermore, the change from supine to standing caused clinically significant increases in the hemoglobin, hematocrit, red blood cell, leukocyte, neutrophil, lymphocyte, basophil and platelet counts, and mean platelet volume, and that from sitting to standing caused clinically significant increases in hemoglobin, hematocrit, and red blood cell, leukocyte, neutrophil and lymphocyte counts.

Conclusion

The results of this investigation provide further support to the notion that effort should be made to achieve widespread standardization in the practice of phlebotomy, including patient posture.

Keywords: Pre-analytical variability, Posture, Plasma volume change, Hematology, Complete blood cell count

Introduction

The complete blood count (CBC) is one of the tests most frequently requested in the clinical practice, because it is a multi-tasking analysis that provides valuable information on a broad range of clinical conditions (i.e., anemia, hemostasis, inflammation, malignancies).1 The samples for CBC are hence routinely requested in virtually all healthcare environments, including emergency departments, and clinical and surgical wards.2 Moreover, both hematocrit and hemoglobin are useful for screening blood donors.

In general, drawing of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-anticoagulated specimens by venipuncture (i.e., those used for CBC testing) can be performed with patients in different postures including lying in bed, after walking through ambulatory services and sitting just before the test (i.e., less than 3 min) or sitting for a long time (i.e., after performing intravenous infusion therapy in day care facilities).

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) H03-A6 document, renamed the GP 41-A6 standard, currently recommends that blood specimens should be collected with the patient comfortably seated in an appropriate chair or lying down, but does not provide specifications about supine or standing positions and time of permanence in a certain position.3 Since the posture may influence the concentration of several blood constituents due to decreased plasma volume occurring on changing from lying to standing,4 it is conventionally assumed that remaining supine for a long time may be associated with consistent hemodilution. On the other hand, the standing posture may be a cause of blood concentration due to the effect of gravitational force and hydrostatic pressure, which cause ultrafiltration of plasma and small molecules in the interstitial space.5

It is a common experience that clinicians not only complain about unexpected variations in hemoglobin levels, especially when these approximate the transfusion threshold,6 but also frequently appraise virtually unexplainable changes in additional parameters of the CBC, such as platelets or the leukocyte count and differential. It is now clearly acknowledged that the vast majority of laboratory errors occur in the pre-analytical phase and are primarily attributable to a lack of standardized protocols during venous blood sampling.7, 8 The influence of posture on the CBC was investigated nearly 30 years ago by Leppanen and Grasbeck,9 who manually measured white blood cell (WBC) differential counts in 22 healthy women after 2 h fasting.9 These authors recommended that venous blood sampling should be standardized to a reference position, either sitting or supine. However, this experimental design – entailing 2 h of fasting10 and manual analysis11 – is barely reproducible according to the current practice and technology. Therefore, this study was planned to evaluate whether postural changes influence the results of the CBC, with special focus on platelets, leukocyte count and differential.

Methods

The study population consisted of 19 healthy subjects (mean age 44 ± 11 years; seven male and 12 female) recruited from the laboratory staff of the University Hospital of Verona (Italy). Venous blood was collected after overnight fasting (12 h) by the standard technique and without venous stasis.12, 13 In brief, three 5.9 mg of K2EDTA blood tubes (Venosafe, Terumo Europe N.V., Leuven, Belgium) were collected from each volunteer on the same day. The first tube was drawn after 25 min in the supine position, the second after 20 min in the sitting position and the last after 20 min in the standing position. Blood collections were serially performed in the order listed above, and the intervals were only those spent in each posture. The CBC was performed with the Advia 2120 hematological analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL). The delta plasma volume change (ΔPVC) was calculated with the reference formula of Dill and Costill as follows: ΔPV(%) = 100 × ((Hemoglobinpre/Hemoglobinpost) × (100 − Hematocritpost)/(100 − Hematocritpre) − 1), using hematocrit values as percentages and hemoglobin values in g/dL.14 Results are expressed as medians and interquartile range (IQR). The significance of differences was evaluated with Wilcoxon's signed rank test, using Analyse-it (Analyse-it Software Ltd., Leeds, UK). The percentage variation calculated from the different postural positions was also compared with the desirable quality specifications for bias derived from biological variations15 as provided by Ricos et al. Briefly, this is best achieved for measurands under strict homeostatic control in order to preserve their concentrations in the body fluid of interest, but it can also be applied to other measurands that are in a steady state in biological fluids. In this case, it is expected that the ‘noise’ produced by the measurement procedure will not significantly alter the signal provided by the concentration of the measurand.16 Each patient provided written consent before being enrolled in the study, which was performed in accord with the ethical standards established by the institution in which the experiments were performed and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Results

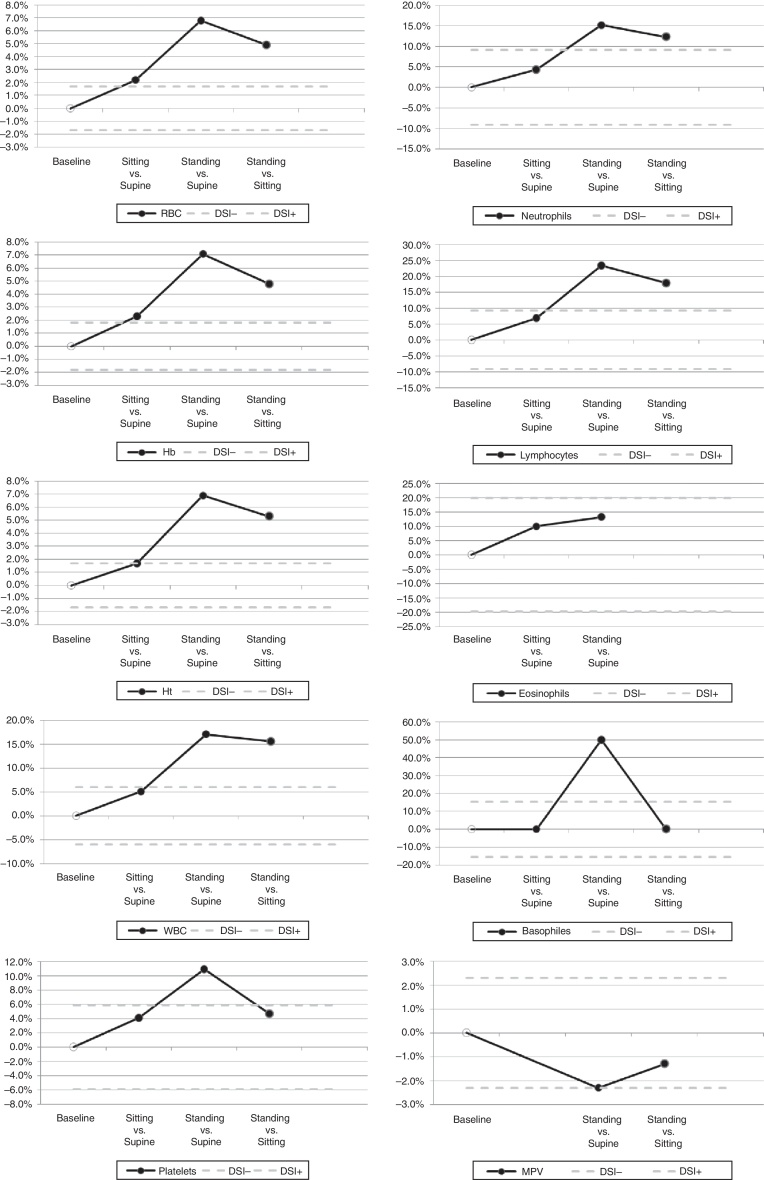

The results of this study are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. According to the formula of Dill and Costill, the ΔPVC was −3.4% from supine to sitting, −14.1% from supine to standing and −9.3% from sitting to standing. Statistically significant variations from supine to sitting were found for the red blood cell (RBC), WBC, neutrophil, lymphocyte, eosinophil, basophil and platelet counts, hemoglobin and hematocrit. When these variations were compared to the quality specifications for bias derived from biological variations, meaningful differences were only observed for the RBC count, hemoglobin and hematocrit. Statistically significant variations from supine to standing were recorded for the RBC, WBC, neutrophil, lymphocyte, eosinophil, basophil, and platelet counts, hemoglobin and hematocrit and mean corpuscular volume (MPV). When these variations were compared against the quality specifications, meaningful differences were found for the RBC count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and WBC, neutrophil, lymphocyte, basophil, and platelet counts and MPV. Furthermore, statistically significant variations from sitting to standing position were observed for the RBC count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, WBC, neutrophil, lymphocyte, basophil, and platelet counts and MPV. When these variations were compared to the quality specifications, meaningful bias was found for the RBC, WBC, neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, hemoglobin and hematocrit.

Table 1.

Variation of routine hematological parameters in different postural positions before and during venipuncture.

| Desirable bias | Supine | Sitting |

Standing |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | p-Value vs. supine | Bias (%) vs. supine | Value | p-Value vs. supine | Bias (%) vs. supine | p-Value vs. sitting | Bias (%) vs. sitting | |||

| PVC (% variation) | – | – | −3.4 (−1.5 to −4.3) | <0.001 | – | −14.1 (−9.1 to −15.7) | <0.001 | −9.3 (−11.1 to −6.6) | <0.001 | – |

| RBC count (×1012/L) | ±1.7% | 4.7 (4.4–5.2) | 4.8 (4.5–5.3) | <0.001 | 2.2 (1.8–2.8) | 5.0 (4.7–5.4) | <0.001 | 6.8 (5.1–9.0) | <0.001 | 4.9 (2.8–5.9) |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | ±1.8% | 131 (127–145) | 134 (129–150) | <0.001 | 2.3 (1.9–2.9) | 141 (134–154) | <0.001 | 7.1 (5.3–8.9) | <0.001 | 4.8 (3.9–6.0) |

| Hematocrit (%) | ±1.7% | 0.41 (0.40–0.44) | 0.42 (0.41–0.44) | 0.009 | 1.7 (1.3–2.5) | 0.44 (0.43–0.47) | <0.001 | 6.9 (5.0–8.9) | <0.001 | 5.3 (3.3–6.3) |

| MCV (fL) | ±1.3% | 89 (87–92) | 90 (87–92) | 0.057 | – | 90 (87–92) | 0.420 | – | 0.670 | – |

| MCH (pg) | ±1.3% | 29.2 (27.7–30.0) | 29.5 (28.0–30.3) | 0.145 | – | 29.2 (28.1–30.2) | 0.147 | – | 0.170 | – |

| RDW (%) | ±1.7% | 13.4 (12.9–13.9) | 13.4 (12.9–13.8) | 0.424 | – | 13.4 (12.9–14.1) | 0.176 | – | 0.178 | – |

| WBC count (×109/L) | ±6.0% | 5.4 (4.6–6.7) | 5.7 (4.9–6.1) | <0.001 | 5.1 (3.2–8.1) | 6.2 (5.3–6.7) | <0.001 | 17.1 (14.2–24.2) | <0.001 | 15.6 (8.2–18.8) |

| Neutrophils (×109/L) | ±9.2% | 3.2 (2.4–3.5) | 3.3 (2.5–3.7) | <0.001 | 4.3 (2.9–8.0) | 3.7 (3.0–4.1) | <0.001 | 15.2 (12.6–25.9) | <0.001 | 12.3 (7.7–16.8) |

| Lymphocytes (×109/L) | ±9.2% | 1.7 (1.2–2.0) | 1.8 (1.2–2.1) | <0.001 | 6.9 (4.5–7.8) | 1.9 (1.5–2.5) | <0.001 | 23.4 (14.1–34.9) | <0.001 | 17.9 (9.3–23.9) |

| Monocytes (×109/L) | ±13.2% | 0.28 (0.23–0.32) | 0.28 (0.22–0.32) | 0.325 | – | 0.28 (0.24–0.32) | 0.117 | – | 0.054 | – |

| Eosinophils (×109/L) | ±19.8% | 0.07 (0.06–0.11) | 0.08 (0.06–0.13) | 0.008 | 10.0 (0.0–17.1) | 0.09 (0.06–0.13) | 0.009 | 13.3 (0.0–34.3) | 0.284 | – |

| Basophils (×109/L) | ±15.4% | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) | 0.02 (0.02–0.03) | 0.008 | 0.0 (0.0–50.0) | 0.03 (0.02–0.04) | <0.001 | 50.0 (12.5–66.7) | 0.012 | 0.0 (0.0–50.0) |

| LUC (×109/L) | Not available | 0.13 (0.12–0.14) | 0.13 (0.10–0.14) | 0.145 | – | 0.13 (0.11–0.16) | 0.259 | – | 0.054 | – |

| Platelets (×109/L) | ±5.9% | 194 (181–233) | 200 (190–243) | <0.001 | 4.1 (2.1–6.3) | 210 (198–248) | <0.001 | 10.9 (4.6–14.8) | 0.002 | 4.7 (0.0–8.8) |

| MPV (fL) | ±2.3% | 8.9 (8.5–9.3) | 8.9 (8.3–9.3) | 0.122 | – | 8.8 (8.1–9.1) | 0.018 | −2.3 (−4.5 to −0.5) | 0.041 | −1.3 (−3.3 to 0.5) |

Results are expressed as medians and interquartile range, significant differences are in bold.

PVC: plasma volume change; WBC: white blood cell; LUC: large and unstained cells; RBC: red blood cell; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin; RDW: red blood cell distribution width; MPV: mean platelet volume.

Figure 1.

Interferograms related to patient posture during blood collection by venipuncture. Patient posture (x-axis) is plotted against bias values (y-axis). Solid line – bias. Dashed lines – acceptable criteria based on desirable specification for imprecision (DSI) derived from biologic variation.

Discussion

The results of this investigation confirm that the patient posture has an impact on the test results of a number of CBC parameters. This was evident for both the platelet count and MPV that were significantly biased when patients changed position from standing to the supine position (Table 1). MPV is an important parameter in the differential diagnosis of patients with thrombocytopenia,17 and for risk assessment of cardiovascular disorders.18 A clinically significant bias was also observed for leukocytes. Interestingly, increases in the WBC, neutrophil, lymphocyte, and basophil counts were on average 2- to 5-fold larger than expected according to the calculated ΔPVC (Table 1). This evidence suggests that an active release of leukocytes may occur from dynamic reservoirs, such as the spleen, when the patient changes from the supine position to standing.19

The CBC has a substantial diagnostic value in the daily clinical practice. When carefully interpreted according to the clinical history of signs and symptoms, this analysis provides useful information in the diagnosis and management of patients with a number of hematological disorders. The CBC is also helpful for longitudinal monitoring of RBCs, platelets and leukocytes in response to drug and/or surgical treatment. However, after the introduction of automated blood count analyzers, a complete panel of blood cell indices can now be generated with a much higher degree of analytical quality and accuracy,20 and thus much effort is required to standardize extra-analytical issues (i.e., patient posture during blood collection by venipuncture).21, 22, 23

The influence of patient posture on blood components has been investigated previously with special focus on larger molecules such as albumin, serum enzymes, bilirubin and lipoproteins.4, 6, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Mayer et al. first studied the influence of posture on hematocrit and demonstrated that a change of position from recumbent to sitting was sufficient to significantly increase the hematocrit, with standing producing an even greater increase.24 Maw et al. also investigated the underlying mechanisms of this modification by measuring body fluid rearrangement during postural variations, and concluded that intravascular fluid loss during standing was mainly due to filtration of plasma into the interstitium.29 More recently, Inagaki et al. demonstrated that the redistribution of water between the intra- and extra-vascular spaces following postural changes during hemodialysis was an important source of changes in blood components, thus underpinning the importance of postural effects for evaluating blood parameters during hemodialysis.30

The findings of this study have some potentially useful clinical implications. First, the evidence that several parameters of the CBC are significantly affected by different postural positions raises the crucial issue that patient posture should be accurately standardized during blood drawing, especially when defining reference ranges for many laboratory tests and assessing longitudinal variations of the same subject over time. A second important aspect is that physicians should not discount the fact that virtually inexplicable variations of RBC, platelets and leukocytes may be caused by the collection of venous blood in different postures rather than by disease (e.g., acute bleeding, platelet consumption as in the case of disseminated intravascular coagulation), or analytical errors. This is particularly crucial for parameters such as the WBC and lymphocyte counts, which increased by approximately 20% from supine to standing position (Table 1 and Figure 1). Finally, we also raise the issue that guidelines for venipuncture such as those of the CLSI3 should include a clear indication that standardizing patient posture is necessary to produce solid data and enable reliable comparisons over time.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this investigation provide further support to the notion that effort should be made to achieve a widespread standardization of the practice of phlebotomy. Clear indications should be given that patient posture during venous blood sampling must be standardized to a reference position, either sitting or supine. Irrespective of the chosen criterion, a recommendation should be given that a minimum period (i.e., 15 or 20 min) of resting in the reference position should be observed before collecting venous blood for CBC.

Authorship

GLO, GLS, GCG and GL conceived and designed the study, analyzed the data, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript; ED and MM reviewed the literature, acquired data, interpreted the results and critically revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lippi G., Salvagno G.L., Solero G.P., Franchini M., Guidi G.C. Stability of blood cell counts, hematologic parameters and reticulocytes indexes on the Advia A120 hematologic analyzer. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;146(6):333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daves M., Zagler E.M., Cemin R., Gnech F., Joos A., Platzgummer S. Sample stability for complete blood cell count using the Sysmex XN haematological analyser. Blood Transfus. 2015;13(4):576–582. doi: 10.2450/2015.0007-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute . 6th ed. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA: 2007. Procedures for the collection of diagnostic blood specimens by venipuncture. CLSI H3-A6 document. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson W.O., Thompson P.K., Dailey M.E. The effect of posture upon the composition and volume of the blood in man. J Clin Investig. 1928;5(4):573–604. doi: 10.1172/JCI100179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fawcett J.K., Wynn V. Effects of posture on plasma volume and some blood constituents. J Clin Pathol. 1960;13:304–310. doi: 10.1136/jcp.13.4.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon M., Paterson C.R. Posture and the composition of plasma. Clin Chem. 1978;24(5):824–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lima-Oliveira G., Lippi G., Salvagno G.L., Picheth G., Guidi G.C. Laboratory diagnostics and quality of blood collection. J Med Biochem. 2015;34(3):288–294. doi: 10.2478/jomb-2014-0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lima-Oliveira G., Volanski W., Lippi G., Picheth G., Guidi G.C. Pre-analytical phase management: a review of the procedures from patient preparation to laboratory analysis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2017;77(3):153–163. doi: 10.1080/00365513.2017.1295317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leppanen E.A., Grasbeck R. Experimental basis of standardized specimen collection: effect of posture on blood picture. Eur J Haematol. 1988;40(3):222–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1988.tb00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lippi G., Lima-Oliveira G., Salvagno G.L., Montagnana M., Gelati M., Picheth G. Influence of a light meal on routine haematological tests. Blood Transfus. 2010;8(2):94–99. doi: 10.2450/2009.0142-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Council for Standardization in Haematology WG. Briggs C., Culp N., Davis B., d’Onofrio G., Zini G., Machin S.J. ICSH guidelines for the evaluation of blood cell analysers including those used for differential leucocyte and reticulocyte counting. Int J Lab Hematol. 2014;36(6):613–627. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guidi G.C., Simundic A.M., Salvagno G.L., Aquino J.L., Lima-Oliveira G. To avoid fasting time, more risk than benefits. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015;53(10):e261–e264. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2014-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lima-Oliveira G., Lippi G., Salvagno G.L., Montagnana M., Picheth G., Guidi G.C. The effective reduction of tourniquet application time after minor modification of the CLSI H03-A6 blood collection procedure. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2013;23(3):308–315. doi: 10.11613/BM.2013.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dill D.B., Costill D.L. Calculation of percentage changes in volumes of blood, plasma, and red cells in dehydration. J Appl Physiol. 1974;37(2):247–248. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westgard J. 2010. Biological variation database specifications. Available from: http://www.westgard.com/biodatabase1.htm [cited 04.10.16] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ceriotti F., Fernandez-Calle P., Klee G.G., Nordin G., Sandberg S., Streichert T. Criteria for assigning laboratory measurands to models for analytical performance specifications defined in the 1st EFLM Strategic Conference. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017;55(2):189–194. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2016-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandra H., Chandra S., Rawat A., Verma S.K. Role of mean platelet volume as discriminating guide for bone marrow disease in patients with thrombocytopenia. Int J Lab Hematol. 2010;32(5):498–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2009.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lippi G., Mattiuzzi C., Comelli I., Cervellin G. Mean platelet volume in patients with ischemic heart disease: meta-analysis of diagnostic studies. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24(2):216–219. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32835b2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Summers C., Rankin S.M., Condliffe A.M., Singh N., Peters A.M., Chilvers E.R. Neutrophil kinetics in health and disease. Trends Immunol. 2010;31(8):318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buttarello M., Plebani M. Automated blood cell counts: state of the art. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130(1):104–116. doi: 10.1309/EK3C7CTDKNVPXVTN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lippi G., Salvagno G.L., Lima-Oliveira G., Brocco G., Danese E., Guidi G.C. Postural change during venous blood collection is a major source of bias in clinical chemistry testing. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;440:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lippi G., Salvagno G.L., Lima-Oliveira G., Danese E., Favaloro E.J., Guidi G.C. Influence of posture on routine hemostasis testing. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2015;26(6):716–719. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lippi G., Salvagno G.L., Lima-Oliveira G., Montagnana M., Danese E., Guidi G.C. Circulating cardiac troponin T is not influenced by postural changes during venous blood collection. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177(3):1076–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer G.A. Diurnal, postural and postprandial variations of hematocrit. Can Med Assoc J. 1965;93(19):1006–1008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Statland B.E., Bokelund H., Winkel P. Factors contributing to intra-individual variation of serum constituents: 4. Effects of posture and tourniquet application on variation of serum constituents in healthy subjects. Clin Chem. 1974;20(12):1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renoe B.W., McDonald J.M., Ladenson J.H. Influence of posture on free calcium and related variables. Clin Chem. 1979;25(10):1766–1769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Felding P., Tryding N., Hyltoft Petersen P., Horder M. Effects of posture on concentrations of blood constituents in healthy adults: practical application of blood specimen collection procedures recommended by the Scandinavian Committee on Reference Values. Scand J Clin Lab Investig. 1980;40(7):615–621. doi: 10.3109/00365518009091972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller M., Bachorik P.S., Cloey T.A. Normal variation of plasma lipoproteins: postural effects on plasma concentrations of lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins. Clin Chem. 1992;38(4):569–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maw G.J., Mackenzie I.L., Taylor N.A. Redistribution of body fluids during postural manipulations. Acta Physiol Scand. 1995;155(2):157–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1995.tb09960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inagaki H., Kuroda M., Watanabe S., Hamazaki T. Changes in major blood components after adopting the supine position during haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(4):798–802. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.4.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]