Abstract

Summary

This systematic review summarizes the effect of combined exercise and nutrition intervention on muscle mass and muscle function. A total of 37 RCTs were identified. Results indicate that physical exercise has a positive impact on muscle mass and muscle function in subjects aged 65 years and older. However, any interactive effect of dietary supplementation appears to be limited.

Introduction

In 2013, Denison et al. conducted a systematic review including 17 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to explore the effect of combined exercise and nutrition intervention to improve muscle mass, muscle strength, or physical performance in older people. They concluded that further studies were needed to provide evidence upon which public health and clinical recommendations could be based. The purpose of the present work was to update the prior systematic review and include studies published up to October 2015.

Methods

Using the electronic databases MEDLINE and EMBASE, we identified RCTs which assessed the combined effect of exercise training and nutritional supplementation on muscle strength, muscle mass, or physical performance in subjects aged 60 years and over. Study selection and data extraction were performed by two independent reviewers.

Results

The search strategy identified 21 additional RCTs giving a total of 37 RCTs. Studies were heterogeneous in terms of protocols for physical exercise and dietary supplementation (proteins, essential amino acids, creatine, β-hydroxy-β-methylbuthyrate, vitamin D, multi-nutrients, or other). In 79% of the studies (27/34 RCTs), muscle mass increased with exercise but an additional effect of nutrition was only found in 8 RCTs (23.5%). Muscle strength increased in 82.8% of the studies (29/35 RCTs) following exercise intervention, and dietary supplementation showed additional benefits in only a small number of studies (8/35 RCTS, 22.8%). Finally, the majority of studies showed an increase of physical performance following exercise intervention (26/28 RCTs, 92.8%) but interaction with nutrition supplementation was only found in 14.3% of these studies (4/28 RCTs).

Conclusion

Physical exercise has a positive impact on muscle mass and muscle function in healthy subjects aged 60 years and older. The biggest effect of exercise intervention, of any type, has been seen on physical performance (gait speed, chair rising test, balance, SPPB test, etc.). We observed huge variations in regard to the dietary supplementation protocols. Based on the included studies, mainly performed on well-nourished subjects, the interactive effect of dietary supplementation on muscle function appears limited.

Keywords: Dietary, Intervention, Physical activity, Sarcopenia

Introduction

Sarcopenia has been defined by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People as a progressive and general loss of muscle mass and muscle function (defined either by a low muscle strength or a low physical performance) with advancing age [1]. Even though the loss of both is a natural part of the aging process, sarcopenia is defined when muscle mass and function falls below defined thresholds. Diagnosis of sarcopenia requires, therefore, the measurement of muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance [2]. Sarcopenia is recognized as a major public health problem [3, 4] due to significant clinical, economic, and social consequences. The implementation of preventive and therapeutic interventions has become a challenge due to the growing number of older persons affected by sarcopenia and its disabling complications.

Physical activity and nutritional supplementation have been investigated in several interventional studies. Recently, Cruz-Jentoft et al. [5] published a systematic review summarizing studies assessing the effect of physical activity and/or dietary supplementation on sarcopenia. Results indicated that most exercise trials showed an improvement of muscle strength and physical performance with physical activity, predominantly resistance training interventions. Results were consistent regarding the effect of dietary supplementation on muscle mass. Some studies have suggested a role of proteins, β-hydroxy β-methylbutyric acid, or amino acid on muscle function. However, the effects of these exercise and dietary interventions were assessed separately in this particular review; little is known about the combined effects of these two interventions. For this reason, Denison et al. [6] conducted a systematic review in 2013 to determine the effect of combined exercise and nutrition interventions on muscle mass, strength, and function in older people. That systematic review comprised 17 studies involving older (≥ 65 years) adults published up to April 2013. The authors concluded that further studies were required to provide adequate evidence on which to base public health and clinical recommendations. The purpose of the present work was to provide an update to that systematic review by including studies published up to October 2015, and to focus on whether additional benefits arose if dietary supplementation was combined with exercise training.

Methods

Literature search

The literature search was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement. Using MEDLINE/Ovid and EMBASE/Ovid, we identified randomized controlled studies (RCTs) which assessed the combined effect of exercise training and nutritional supplementation on muscle strength, muscle mass, or physical performance. We updated the paper by Denison et al. [6] which limited the search strategy to February 2013. Therefore, we searched for any additional studies published between April 2013 and October 2015. The search strategy and search terms that were used for this research are detailed in Table 1. Additional studies were identified by a manual search of bibliographic references of relevant articles and existing reviews. Conference abstracts were not included.

Table 1.

Search strategy (application to MEDLINE Ovid and EMBASE)

| 1. Sarcopenia/ |

| 2. Sarcopeni$.tw |

| 3. Muscle atrophy/ |

| 4. Muscle weakness/ |

| 5. Fat free mass.tw |

| 6. Lean body mass.tw |

| 7. Muscle mass.tw |

| 8. Exp hand strength/ |

| 9. Grip strength.tw |

| 10. Anthropometry/ |

| 11. Body composition/ |

| 12. Lean mass.tw |

| 13. Or/1-12 |

| 14. Exp exercise/ |

| 15. Exp Movement/ |

| 16. Muscle contraction/ |

| 17. Muscle Development/ |

| 18. Physical exertion/ |

| 19. Exp Physical endurance/ |

| 20. Exp muscle strength/ |

| 21. Physical fitness/ |

| 22. Exp Exercise test/ |

| 23. Exercise therapy.tw |

| 24. Exp Exercise movement techniques/ |

| 25. Exp Psychomotor performance/ |

| 26. Muscle contraction/ |

| 27. Resistance exercise.tw |

| 28. Aerobic exercice.tw |

| 29. Endurance.tw |

| 30. Physical exercise.tw |

| 31. Physical performance.tw |

| 32. Physical training.tw |

| 33. Exercise programme.tw |

| 34. Exercise technique.tw |

| 35. Muscle mass.tw |

| 36. Or/14-35 |

| 37. Nutrition.tw |

| 38. Exp nutrition therapy/ |

| 39. Exp Nutritional physiological phenomena/ |

| 40. Exp Diet/ |

| 41. Exp Diet therapy/ |

| 42. Exp Dietary fats/ |

| 43. Exp Dietary proteins/ |

| 44. Exp Food/ |

| 45. Exp Food, fortified/ |

| 46. Exp Micronutrients/ |

| 47. Exp Dietary supplements/ |

| 48. Energy intake/ |

| 49. Nutrition.tw |

| 50. Nutrition trial.tw |

| 51. Dietary lipids.tw |

| 52. Or/37-51 |

| 53. Randomized controlled trials/ |

| 54. Randomised controlled trial.tw |

| 55. Randomized controlled trial.tw |

| 56. Controlled clinical trial/ |

| 57. Controlled study.tw |

| 58. Random allocation/ |

| 59. Random$.tw |

| 60. Randomly allocated.tw |

| 61. Double blind method/ |

| 62. Single blind method/ |

| 63. Clinical trials.tw |

| 64. Clinical trial/ |

| 65. Trial$.tw |

| 66. Intervention studies/ |

| 67. Intervention study.tw |

| 68. Interventional study.tw |

| 69. Placebo.tw |

| 70. Placebo$.tw |

| 71. Or/53-70 |

| 72. And/36,52 |

| 73. And/13, 71, 72 |

| 74. (73 and humans/) or (73 not (humans/ or animals/)) |

| 75. Limit 74 to English language |

| 76. Limit 75 to yr. = “2013-Current” (344 results on PubMed (308 after deleting duplicates)– 859 with Embase (819 after remove duplicates)) – total 992 after remove duplicates between the 2 databases |

Study selection

In the initial screening stage, two investigators independently reviewed the title and abstract for each of these references to exclude articles irrelevant to the systematic review. Rigorous inclusion criteria were adhered to (Table 2). In the second step, the two investigators independently read full texts of the articles not excluded in the initial stage, then selected the studies meeting the inclusion criteria (Table 2). All differences of opinion regarding selection of articles were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Table 2.

Inclusion criteria

| Design | Randomized controlled trials |

| Participants | Human, men, and women aged 60 years and older |

| Exposure | Studies which include at least two groups of comparison: a control group with only exercise intervention and a treated group with combined exercise intervention and nutritional intervention. Exercise intervention can be resistance exercise, aerobic exercise, or other. Nutrition intervention involves the provision of nutrients supplied with either a supplement or food |

| Outcome | Outcomes on muscle mass, on muscle strength, or on physical performance |

| Language | English only |

| Date | Studies published between April 2013 and end of October 2015 |

In order to maintain consistency between this update and the previous systematic review, the same inclusion criteria were used [6]. No age restriction was included in the search strategy but this review focused only on subjects aged 60 years and older. Studies performed on children, adolescents, and young adults were therefore excluded. Studies in which the nutritional intervention was energy restriction to promote weight loss were also excluded. Finally, studies were also excluded if they included populations with a specific health condition (e.g., cirrhosis, cancer, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, etc.).

Data extraction

Data were extracted according to a standardized form to include authors, journal name, year of publication, country, objective of the study, length of intervention, type of population, gender ratio, mean age, age range, detailed groups with sample size, adherence to the treatment, % of participants who completed the study, adverse events, protocol of exercise intervention, protocol of nutritional intervention, muscle mass outcomes, muscle strength outcomes, and physical performance outcomes.

Methodology quality assessment

The quality of each study was independently assessed by two authors using the Jadad Score [7] system. The Jadad score ranges from 0 to 5 points. Studies were considered to be of excellent quality if the score was 5, good quality if the score was 3 or 4, and poor quality if otherwise.

Presentation of results

The findings were evaluated in a descriptive manner based on the information provided by each of the included studies. Because of the huge heterogeneity observed in the protocols of exercise and dietary supplementation, no meta-analysis was undertaken.

Results

Included studies

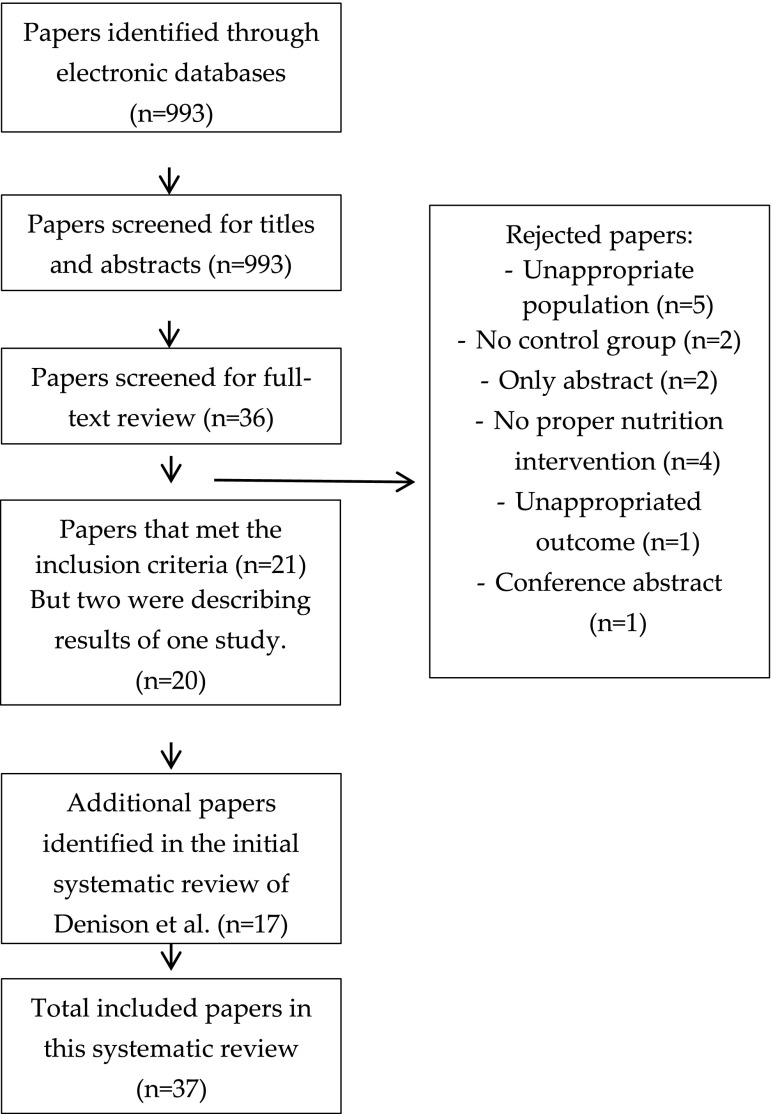

A total of 993 references were identified through the database search. A manual search of the bibliography of 10 relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses did not generate any further studies for inclusion. After reading all titles and abstracts, 36 RCTs were selected for full-text review, following which 21 were included in this systematic review update. These 21 studies, added to the previous 17 considered by Denison et al. [6], gave a total of 37 RCTs included in the current systematic review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of literature search

Characteristics of the studies are shown in Table 3. Twelve studies were performed in Europe, 11 in the USA/Canada, 7 in Asia, 4 in South America, and 3 in Australia. The number of participants ranged from 17 [35] to 222 [26] and study duration ranged from 4 weeks [27] to 18 months [42, 43]. The majority of studies included both male and female participants but 10 studies were confined to women only and 5 included only men. The mean age of participants varied from 59.5 ± 4.5 years [9, 10] to 87.1 ± 0.6 years [39, 40]. Twelve RCTs were graded on the Jadad Scale as having an excellent quality, 15 a good quality, and 10 a poor quality.

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies

| Reference | Settings, study participants, mean age ± SD | Study design | Exercise training intervention | Nutritional supplement | Outcome measures | Quality score (Jadad scale) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gryson et al. 2014 [8] | France. 35 healthy sedentary men 60.7 ± 0.4 years | 16-week intervention. Participants randomized in 5 groups: (i) no exercise + placebo, (ii) exercise + placebo, (iii) exercise + fortified milk, (iv) no exercise + fortified leucine, (v) exercise + fortified leucine. Treatments were administrated double blind | Resistance and aerobic exercises.3 sessions per week, non-consecutive days, 45–60 min for each session | Protein. Milk-based supplement drinks containing, proteins (total milk proteins 10 g/day or fast digested soluble milk proteins 10 g/day), carbohydrates, and fat. Placebo drinks contains 4 g of total milk protein | MM: appendicular muscle mass and fat-free mass in the dominant legMS: isometric strength of the knee extensors | 4 |

| Lebon et al. 2014, [9] Choquette et al. 2013 [10] | Canada. 34 postmenopausal women 59.5 ± 4.5 years | 6-month intervention. Participants randomized in two groups: (i) exercise and isoflavone, (ii) exercise and placebo. Treatments were administered double blind | Combined aerobic and resistance training, 3 sessions per week (1 h, 30 min of aerobic, 30 min of resistance) | Other (soy isoflavones). 4 capsules daily with either soy isoflavones or placebo. The 70-mg daily dose of isoflavones contained 44 mg of daidzein, 16 mg of glycitein, and 10 mg of genistein extracted from natural soy. Placebos contained cellulose | MM: waist and hip circumference, muscle mass indexMS: grip strength, 1RM (leg press, bench press, lat pulldown) PP: chair stand test | 5 |

| Gualano et al. 2014 [11] | Brazil. 60 vulnerable older women. Treated 67.1 ± 5.6 years/control 63.6 ± 3.6 years | 24-week intervention. Participants were randomized in four groups: (i) placebo, (ii) creatine, (iii) placebo + exercise, (iv) creatine + exercise. Treatments were administered double blind | Supervised resistance training. Two sessions per week | Creatine. Supplements packages 20 g/day of creatine monohydrate for 5 days divided into four equal doses, followed by single daily doses of 5 g for the next 23 weeks. Placebo was dextrose | MM: appendicular lean mass MS: leg press, bench pressPP: timed-stands tests., Timed up and go test | 4 |

| Villanueva et al. 2014 [12] | USA. 22 healthy men, recreationally active 68.1 ± 6.1 years | 12-week intervention. Participants were randomized in three groups: (i) exercise + creatine and protein supplementation, (ii) exercise only, (iii) control. Treatment administration was not double blinded | Resistance training. 3 sessions per week | Protein + creatine. Supplemented group (encapsulated powder) consumed 0.3 g/kg/day of creatine for 5 days followed by 0.07 g/kg/day until completion of the study. The supplemented group also consumed one 35-g liquid protein ready-to-drink daily | MM: lean body massMS: leg press, chest press, strength endurance. PP: stair climbing power, dynamic power, 400-m walk | 2 |

| Stout et al. 2013 [13] | USA. 48 ambulatory participants (22 men and 26 women) 73 ± 1 years | 24-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + placebo, (ii) exercise + HMB. Treatments were administered double blind | Supervised resistance training. Three sessions per week | β-hydroxy-β-methylbuthyrate.CaHMB (HMB, 1,5 g CaHMB + 4 g carbohydrate) twice daily. Placebo (200 mg calcium + 4 g carbohydrates) twice daily.Participants were asked to mix their product in non-alcoholic beverages and drink it | MM: total lean mass, reginal leg lean mass, regional arm lean massMS: handgrip strength, leg extension, bench press, leg press, leg extension strength. PP: Get up and Go | 5 |

| Okazaki et al. 2013 [14] | Japan. 35 healthy middle-aged and older women. Treated 60 ± 3 years/control 61 ± 3 years | 5-month intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise only, (ii) exercise + post-exercise macronutrient. Treatment administration was not double blinded | Home-based interval walking training. 4 or more days per week | Multi-nutrient (macrunutrient mixture). 215 g of a macronutrient mixture within 30 min after each training session (composition 200 kcal; 7,6 g protein ; 32,5 g CHO ; 4,4 g fat) | MM: total muscle tissue areaMS: isometric knee extension, isometric knee flexion, isokinetic knee extension, isokinetic knee flexion | 2 |

| Narotzki et al. 2013 [15] | Israel. 13 elderly men and 9 elderly women. 71.1 ± 1.2 years | 12-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + green tea and vitamin E, (ii) exercise + vitamin E only. Treatment administration was not double blinded | Fitness-guided exercises. 6 times a week. 30 min of daily walks | Other (green tea). Participants were asked to brew tea sachets 3 times a day in 240 ml of boiling water for 3 min. One vitamin E capsule composed of 400 IU of d-alpha-tocopherol a day. Placebo group did not drink tea and consumed a capsule of vitamin E placebo a day | MM: waist and hip circumference | 2 |

| Deutz et al. 2013 [16] | USA. 24 older adults confined to complete bed rest for 10 days. Treated 67.4 ± 1.4 years/control 67.1 ± 1.7 years | 8-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + HMB, (ii) exercise + placebo. Treatments were administered double blind. Tests were performed before bedrest, after bed rest, and after the 8 weeks of rehabilitation | Resistance exercise training rehabilitation. 3 days per week. Strength training during 1 h | β-hydroxy-β-methylbuthyrate. 2 sachets of Ca-HMB per day. Each sachet contained 1.5 g of Ca-HMB, 4 g maltodextrin, and 200 mg calcium. The composition of placebo was identical with the exclusion of Ca-HMB | MM: lean body massMS: knee extension, flexor force, leg press, standing plantar flexor force, and stair ascent and descent power. PP: SPPB test, Get up and Go test, 5-item SPPB | 5 |

| Chalé et al. 2013 [17] | USA. 80 mobility-limited women aged 70–85 years. Treated 78.0 ± 4.0 years/control 77.3 ± 3.9 years | 6-month intervention. Participants randomized in two groups: (i) exercise and proteins, (ii) exercise and isocaloric control. Treatments were administered double blind | Supervised progressive program. 3 times per week which entailed leg press, seated row, leg extension, chest press and leg curl | Protein (whey protein). Whey protein in powder form 40 g/day (one serving contains 20 g protein, 25 g maltodextrin, 1 g fat, 189 kcal) Isocaloric control in powder form (45 g maltodextrin, 1 g fat, 189 kcal) | MM: lean mass, total muscle CSAMS: Leg press, knee extension strength, peak power PP: Stair climbing, chair rise performance, SPPB test, 400 m walk time | 5 |

| Kim et al. 2013 [18] | Japan. 128 community-dwelling elderly sarcopenic women Treated 81.1 ± 3.7 years /control 79.6 ± 4.2 years | 3-month intervention. Participants were randomized in four groups: (i) exercise and tea catechin, (ii) exercise only, (iii) tea catechin only, (iv) health education, control. Treatments were administered double blind | Stretching, muscle strengthening, balance and gait training. Two sessions per week. Each session 60 mins | Other (tea catechin). One bottle per day containing 350 mL of tea fortified with 540 mg of catechin | MM: lean body mass, appendicular lean mass and leg muscle mass MS: grip strength, knee extension strength PP: usual and maximum walking speed, TUG, balance ability | 4 |

| Aguiar et al. 2013 [19] | Brazil. 18 healthy women 64.9 ± 5.0 years | 12-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + creatine, (ii) exercise + placebo. Treatments were administered double blind | Resistance training. Three sessions per week. The training volume was progressive throughout the training program | Creatine. One capsule (5.0 g/day). The placebo group ingested an identical-looking equivalent amount of placebo, maltodextrin | MM: appendicular muscle mass MS: bench press, knee extension, biceps curl strength PP: 30-s chair stand and arm curl test and a test of getting up from lying on the floor | 4 |

| Leenders et al. 2014 [20] | The Netherlands. 29 healthy elderly men and 24 healthy elderly women 70 ± 1 years | 24-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + placebo, (ii) exercise + protein. Treatments were administered double blind | Supervised resistance training. Three sessions per week | Protein. 250 ml beverages per day. Protein beverages contains 15 g of protein, 0.5 g fat, 7.13 g lactose, 0.42 g calcium. Placebo beverages contain no protein or fat, 7.13 g lactose, 0.42 g calcium | MM: total body lean mass, leg lean mass, quadriceps CSA MS: leg press, leg extension, handgrip testPP: sit-to-stand test | 3 |

| Veronese et al. 2014 [21] | Italy. 139 healthy elderly women. 71.5 ± 5.2 years | 12-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + magnesium oxide, (ii) exercise only. Treatment administration was not double blinded | Mild fitness program. Two sessions per week | Other (magnesium oxide)sachets. 900 mg/d of oral magnesium oxide corresponding to 300 mg bioavailable magnesium | MM: appendicular skeletal muscle mass indexMS: isometric knee extension, handgrip strength PP: SPPB test | 3 |

| Daly et al. 2014 [22] | Australia. 100 women residing in retirement villages. Treated 72.1 ± 6.4 years/control 73.6 ± 7.7 years | 4-month intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + meat, (ii) exercise only. Treatment administration was not double blinded | Supervised progressive resistance and balance-agility training program. 2 sessions per week | Protein (lean red meat). 220 g lean red meat to be consumed 6days/week = 160 g cooked meat/day (45 g protein). Control 75 g cooked rice and/or pasta/day (that provides 25–35 carbohydrates/day) | MM: lean tissue mass MS: leg extensionPP: 4-square step test, Timed Up and Go, 30-s sit-to-stand test | 5 |

| Cooke et al. 2014 [23] | Australia. 20 middle to older males Treated 61.4 ± 5.0 years/control 60.7 ± 5.4 years | 12-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + CHO, (ii) exercise only. Treatments were administered double blind | High-intensity resistance training program. 3 days per week | Creatine monohydrate-carbohydrates. Treated group 20 g of CrM combined with 5 g of glucose for 7 days followed by 0.1 g kg−1 (average dosage of ∼8.8 g) of CrM with 5 g of glucose on training days. Placebo 20 g of glucose only for 7 days followed by 5 g of glucose on training days | MM: fat-free mass MS: leg press, bench press | 4 |

| Oesen et al. 2015 [24] | Italy. 82 older adults living in retirement care facilities 82.8 ± 6.0 years | 6-month intervention. Participants were randomized in three groups: (i) exercise only, (ii) exercise + nutrient supplementation, (iii) cognitive training group. Treatment administration was not double blinded | Supervised resistance exercise with elastic band. Two sessions per weeks on non-consecutive days (separately min 48 h) | Protein and essential amino acids. Two nutrient supplement drink per day. Each drink had a caloric value of 150 kcal, 20.7 g protein (3 g leucine, >10 g essential amino acids), 9.3 g carbohydrates, 3 g fat, vitamins and minerals | MS: knee extensor peak torque, knee flexor peak torque, handgrip strengthPP: chair stand test, gait speed, six-minute walking test, functional reach test, arm lifting test | 2 |

| Zdzieblik et al. 2015 [25] | Germany. 53 elderly men with sarcopenia. 72.2 ± 4.68 | 12-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + collagen peptide, (ii) exercise + placebo. Treatments were administered double blind | Guided training program on fitness devices. Three sessions a week over a period of 60 min | Protein (collagen peptide).Treated group received 15 g of collagen peptides each day. Placebo group received silicon dioxide as placebo. Both were given in powder to dissolve in 250 ml of water. | MM: fat-free mass MS: isokinetic quadriceps strength of the right leg | 5 |

| Yamada et al. 2015 [26] | Japan. 222 community-dwelling older adults (142 women and 80 men). Treated 76.3 ± 5.9 years/control 75.8 ± 5.2 years | 6-month intervention. Participants were randomized in three groups: (i) walking and nutrition, (ii) walking only, (iii) control. Treatment administration was not double blinded | Walking program. Use of pedometer-based walking programs. Participants were instructed to increase the number of daily steps by 10% each month | Protein and vitamin D. Daily supplements composed of 200 kcal, 10.0 g of protein with branched chain amino acids 12.5 mg of vitamin D, and 300 mg of calcium | MM: skeletal muscle index | 2 |

| Trabal et al. 2015 [27] | Spain. 24 older adults in nursing homes and adult day care centers (16 women and 8 men). Treated 85 ± 8 years/control 84 ± 4 years | 4-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise and leucine, (ii) exercise only. Treatments were administered double blind | Resistance training. Three sessions of progressive resistance training adapted for older adults and one session of balance exercise per week | Essential amino acid (leucine). Leucine 10 g/day or the same amount of maltodextrin as placebo. Both supplements and placebo were accompanied with a lemon and lime flavor to disguise the characteristic taste of leucine | MM: calf circumference, waist circumference. MS: maximal isometric leg strength. PP: standing balance, 4 m walk, chair stands test and TUG test | 5 |

| Kim et al. 2015 [28] | Japan. 130 community-dwelling frail women. Treated 81.0 ± 2.6 years/control 81.1 ± 2.8 years | 3-month intervention. Participants were randomized in four groups: (i) exercise and milk fat globule membrane, (ii) exercise only, (iii) milk fat globule membrane only, (iv) health education, control. Treatments were administered double blind | Physical comprehensive training program of moderate intensity. Each class was 60 min, twice per week | Other (milk fat globule membrane). The composition was 21.5% protein, 44% fat, 26.5% carbohydrate, 33.3% phospholipids, 6.4% ash, and 1.6% moisture. Six pills (1 g of MFGM) ingested daily. The placebo consisted of pills of similar shape, taste, and texture and included milk powder instead of MFGM. Milk powder was composed of 26.3% protein, 25.2%fat, 39.5% carbohydrate, 0.286 phospholipids, 5.7% ash, and 3,3% moisture | MM: appendicular muscle mass, leg muscle mass MS: grip strength, knee extension PP: usual walking speed, timed up and go | 5 |

| Shahar et al. 2013 [29] | Malaysia. 65 elderlies with sarcopenia (18 women and 47 men). 67.1 ± 5.3 years | 12-week intervention. Participants were randomized in four groups: (i) control group, (ii) exercise group, (iii) protein supplementation, (iv) exercise + protein supplementation. Treatment administration was not double blinded | Moderately intensive, well-rounded activities in facilitated group sessions. During 60 min, two sessions per week | Protein (soy protein). 20 g/day and 40 g/day of high protein supplementation in a powder form to men and women, respectively. Control group did not received placebo but a relaxation exercise program to maintain interaction and increase motivation | MM: total muscle mass and fat-free mass MS: handgrip strength, arm curl test PP: chair stand test, chair sit and reach, back scratch, 8-ft and go, 6-min walk | 1 |

| Arnarson et al. 2013 [30] | Iceland. 161 healthy community-dwelling men and women. (94 women and 67 men) Treated 73.3 ± 6.0/control: 74.6 ± 5.5,8 | 12-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + whey protein supplement or (ii) exercise only. Treatment administration was not double blinded | Resistance exercise program. Participants exercised three times per week | Protein (whey protein). Drink (250 mL) providing 20 g protein, 20 g carbohydrate, 1 g fat (169 kcal) (intervention) or isocaloric drink containing 40 g carbohydrate, 1 g fat (control) consumed immediately after exercise | MM: lean body mass, appendicular lean mass MS: quadriceps muscle strength PP: timed up and go; 6-min walk for distance | 5 |

| Rosendahl et al. [31] 2006, Carlsson et al. 2011 [32] | Sweden. 191 older men and women in residential care. (139 women and 52 men) 84.7 ± 6.5 years | 3-month intervention. Participants randomized to four groups: (i) protein-enriched drink, control activity, (ii) exercise training + placebo drink, (iii) protein-enriched drink + exercise training, or (iv) neither (control activity, placebo drink). Treatment administration was not double blinded | High-intensity multicomponent exercise program, including resistance exercise training and balance exercises. Participants exercised five times per fortnight | Protein (milk-based protein-enriched drink). Drink (200 mL), providing 7.4 g protein, 15.7 g carbohydrate, 408 kJ per 100 g. Placebo drink (200 mL) contained 0.2 g protein, 10.8 g carbohydrate, 191 kJ per 100 g. Drinks offered within 5 min of exercise session | MM: total lean massMS: lower-limb muscle strength PP: balance (Berg Balance Scale), gait ability (2.4 m timed test) | 3 |

| Tieland et al. 2012 [33] | The Netherlands. 20 frail older men and 41 frail older women Treated 78 ± 9 years/control: 79 ± 6 years | 24-week intervention. Participants randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + protein supplementation or (ii) exercise + placebo drink. Treatments were administered double blind | Resistance-type exercise training. Participants exercised twice per week | Protein. Protein-supplemented drink (250 mL), (15 g protein, 7.1 g lactose, 0.4 g calcium) and placebo drink (no protein, 7.1 g lactose, 0.4 g calcium) consumed twice per day | MM: lean mass MS: leg press, leg extension, handgrip PP: SPPB test | 5 |

| Verdijk et al. 2009 [34] | The Netherlands. 28 healthy older men, living independently 72 ± 2 years | 12-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + protein or (ii) exercise + water. Treatments were administered double blind | Resistance-type exercise training. Participants exercised three times per week in the morning, at same time of day | Protein. Protein drink (10 g casein hydrolysate, 250 mL) or placebo drink (250 mL water) given immediately before and following exercise sessions | MM: lean mass, leg lean mass, cross-sectional area of quadriceps MS: leg press, leg extension | 3 |

| Godard et al. 2002 [35] | USA. 17 older men Treated 70.8 ± 1.5/control 72.1 ± 1.9 | 12-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + EAA or (ii) exercise with no dietary supplementation (control). Treatment administration was not double blinded | Progressive knee extensor resistance training program. Participants exercised three times per week | Essential amino acids. Amino acid-containing drink (400 mL) providing 12 g essential amino acids, 72 g fructose and dextrose; consumed immediately after training or at same time each day | MM: whole muscle cross-sectional area of right thigh MS: knee extension | 1 |

| Kim et al. 2012 [36] | Japan. 155 sarcopenic, community-dwelling older women Treated 79.5 ± 2.9 years/control 79,2 ± 2,8 | 3-month intervention. Participants randomized to four groups: (i) EAA, (ii) exercise training, (iii) supplementation + exercise or iv) health education (once per month). Treatment administration was not double blinded | Multicomponent exercise program including resistance exercise training. Participants exercised twice per week | Essential amino acids. Powdered amino acid supplements provided to be taken twice daily with water or milk, supplying 6 g essential amino acids per day | MM: total muscle mass MS: knee extension. PP: usual and maximum walking speed | 3 |

| Vukovich et al. 2001 [37] | USA. 15 healthy older men and16 healthy older women 70 ± 1 years | 8-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) HMB + exercise or (ii) a placebo supplement + exercise. Treatments were administered double-blind | Multicomponent exercise training including resistance exercises. Participants exercised 5 days per week (2 days strength training, 3 days walking and stretching) | β-hydroxy-β-methylbuthyrate. Supplement capsules contained 250 mg Ca-HMB; participants consumed four capsules, three times per day (3 g/day). Placebo capsules were identical in appearance, providing 3 g/day rice flour | MM: fat-free mass, muscle area. MS: upper and lower body strength | 4 |

| Bonnefoy et al. 2003 [38] | France. 57 frail resident in retirement homes (50 women and 7 men) 83 years | 9-month intervention. Participants randomized to four groups: (i) nutritional drink + control activity (memory), (ii) exercise training + placebo drink, (iii) nutritional drink + exercise training, or (iv) control activity + placebo drink. Treatment administration was not double blinded | Multicomponent exercise training including resistance exercises. Participants exercised three times per week. Three weekly memory sessions served as controls for exercise | Multi-nutrient. Nutritional drinks (200 mL) (providing 200 kcal, 15 g protein, vitamins and minerals) or placebo (providing no nutrients) given twice daily | MM: fat-free mass MS: explosive leg extension (power). PP: gait speed, six-step stair climb, chair rise, balance abnormalities | 3 |

| Fiatarone et al. 1994, [39] Fiatarone et al. 1993 [40] | USA. 100 frail nursing home residents, 37 men and 63 women 87.1 ± 0.6 years | 10-week intervention. Participants randomized to four groups: (i) multi-nutrient supplementation, (ii) exercise training, (iii) supplementation + exercise or iv) neither (control). Treatment administration was not double blinded | Progressive resistance exercise training of hip and knee extensors. Participants exercised 3 days per week. Other participants offered alternative recreational activities | Multi-nutrient. Nutritional supplement provided as a daily drink (240 mL), supplying 360 kcal, 15 g protein and vitamins and minerals. Participants who were not supplemented were given a minimally nutritive drink of equal volume (4 kcal) | MM: thigh muscle area, fat-free mass MS: grip strength, hip and knee extensors PP: gait speed, stair climb, balance | 2 |

| Miller et al.2006 [41] | Australia. 79 older women and 21 older men hospitalized following a fall-related lower-limb fracture 83.5 (82.3–84.7) years | 12-week intervention. Participants randomized to four groups: (i) nutritional supplementation, (ii) exercise training, (iii) supplementation + exercise or iv) attention control (home visits only, general nutrition and exercise advice). Treatment administration was not double blinded | Progressive resistance exercise training program. Participants exercised three times per week | Multi-nutrient. Complete oral nutritional supplement prescribed to provide 45% of individually estimated energy requirement, administered in four daily doses while hospitalized or two doses after discharge home | MS: quadriceps strength PP: gait speed | 3 |

| Bunout et al. 2001, [42] Bunout et al. 2004 [43] | Chile. 108 community-dwelling poor older people (42 men and 66 women). Treated 73.7 ± 3.0/control 74.4 ± 3.3 | 18-month intervention. Evaluation at 12 and 18 months. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + nutritional supplementation or (ii) exercise but no dietary supplementation. Treatment administration was not double blinded | Resistance exercise. Participants exercised twice per week | Multi-nutrient. Nutritional product (prepared as a soup or porridge, given as two daily snacks), to provide 400 kcal, 13 g protein, ∼25% daily requirements for micronutrients | MM: fat-free mass MS: handgrip, quadriceps, biceps strength PP: walking capacity (m) | 1 |

| Chin A Paw et al. 2001 [44], De Jong et al. 2000 [45] | The Netherlands. 217 frail community-dwelling older men and women (45 men and 172 women). Treated 78.9 ± 6.0/control 76.2 ± 4.5 | 17-week intervention. Participants randomized to four groups: (i) supplementation, (ii) exercise training, (iii) supplementation + exercise or iv) neither (control). The nutritional intervention was double-blinded | Multicomponent exercise training (gradually increasing intensity). Participants exercised twice per week | Other (vitamins and minerals). Supplemented group asked to consume one fruit and one dairy product enriched with vitamins and minerals per day. Other participants received same products that were not enriched | MM: lean body mass, waist circumference, hip circumference MS: handgrip, quadriceps strength PP: gait speed, chair rise, balance, flexibility | 4 |

| Binder et al. 1995 [46] | USA. 25 nursing home residents with dementia (16 men and 9 women). Treated 87 ± 4.4 years/control 88.7 ± 6.9 years | 8-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + calcium carbonate + vitamin D supplementation, or (ii) exercise + calcium carbonate only. Treatment administration was not double blinded | Multicomponent but mainly resistance-type exercise. Participants exercised three times per week | Vitamin D. Intervention group given bolus dose (orally) of 100,000 U vitamin D3 at start of study, then weekly supplements 50,000 U | MS: knee extensor, lower extremity PP: gait speed, balance | 2 |

| Bunout et al. 2006 [47] | Chile. 96 community-dwelling older men and women, with low vitamin D status (86 women, 10 men) 76 ± 4 years | 9-month intervention. Participants randomized to receive exercise training or no training, and further randomized to receive supplementation (double blind) with vitamin D/calcium or calcium alone. Treatments were administered double blind | Resistance exercise training; participants exercised twice per week | Vitamin D. Combined oral vitamin D/calcium supplement (400 IU/800 mg) or calcium-only supplement (800 mg) provided, to be taken in the evening | MM: lean mass MS: handgrip, quadriceps strength PP: TUG, SPPB | 5 |

| Brose et al. 2003 [48] | Canada. 30 healthy-community-dwelling older men and women (15 women and 15 men) 65+ years. | 14-week intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + creatine supplement or (ii) exercise + placebo. Treatments were administered double blind | Resistance exercise training. Participants exercised three times per week | Creatine. Daily creatine monohydrate supplement (5 g + 2 g dextrose) (intervention) or placebo (7 g dextrose) (control) | MM: fat-free mass MS: handgrip, ankle dorsiflexion, knee extension, dynamic 1RM PP: chair rise, stair climb, walking speed | 4 |

| Tarnopolsky et al. 2012 [49] | Canada. 39 community-dwelling older men and women (10 women, 19 men) 65+ years | 6-month intervention. Participants were randomized in two groups: (i) exercise + supplementation with creatine monohydrate and conjugated linoleic acid, (ii) exercise + placebo. Treatments were administered double blind |

Resistance exercise training program; participants exercised twice per week | Creatine. Daily supplementation with creatine monohydrate (5 g) + conjugated linoleic acid (6 g) + 2 g dextrose or placebo (7 g dextrose + 6 g safflower oil) | MM: fat-free mass MS: handgrip, ankle dorsiflexion, knee extension strength, endurance PP: chair rise, stair climb, walking speed, balance | 5 |

MM muscle mass, MS muscle strength, PP physical performance, 1-RM one repetition maximum test, IU international unit, HMB β-hydroxy-β-methylbuthyrate, SPPB short physical performance battery, TUG Timed Up and Go, CSA cross-sectional area, CHO carbohydrate

Twenty-two studies used a two-group comparison methodology: one group receiving exercise + nutrition and the other group receiving exercise only (with placebo or no intervention). Eleven other studies used a four-group comparison model with one control group with no intervention, one group with exercise only, one group with nutrition only and finally, one group with combined exercise and nutrition interventions. Three other studies chose to randomize their population into three groups comprising a control group with no intervention, a group with exercise only, and a group with exercise combined with nutrition. Finally, one study used a five-group comparison model that included two groups with exercise and nutrition interventions, but used a different nutritional supplement in each of these two groups. For this systematic review, we used only results from two groups, one receiving exercise + nutrition and one receiving exercise only. It has to be noted that only half of the studies were double blinded.

Regarding nutritional interventions, 10 of the 37 studies used proteins. One further study used protein combined with essential amino acids, a second used protein combined with vitamin D, and a third used protein combined with creatine. Three studies used essential amino acids alone, five studies used creatine alone, three studies used β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate alone, and two used vitamin D alone. Of the remaining 12 studies, five used multi-nutrient supplements and six used other products (vitamin and mineral-enhanced dairy and fruit products, green tea, magnesium oxide, milk fat globule membrane, soy isoflavones, and tea catechin). For exercise, the majority of studies used resistance training with the remainder using multicomponent training involving both resistance and additional exercises such as walking, fitness, aerobics, balance, etc.

Types of nutritional intervention

Results of the interventions are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

General summary of the systematic review

| Muscle mass | Muscle strength | Physical performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant increase with exercises | Significant added effect with nutrition | Significant increase with exercises | Significant added effect with nutrition | Significant increase with exercises | Significant added effect with nutrition | |

| Protein | 11/12 RCTs | 3/12 RCTs | 12/12 RCTs | 3/12 RCTs | 9/9 RCTs | 0/9 RCTs |

| EAA | 2/3 RCTs | 0/3 RCTs | 2/3 RCTs | 0/3 RCTs | 2/2 RCTs (only for SPPB and TUG) | 0/2 RCTs |

| HMB | 3/3 RCTs | 1/3 RCTs | 2/3 RCTs | 0/3 RCTs | 2/2 RCTs (only for TUG) | 0/2 RCTs |

| Multi-nutrient | 2/4 RCTs | 0/4 RCTs | 3/5 RCTs | 1/5 RCTs | 3/4 RCTs | 0/4 RCTs |

| Creatine | 5/5 RCTs | 4/5 RCTs | 5/5 RCTs | 4/5 RCTs (for some of muscle strength outcomes) | 3/4 RCTs | 1/4 RCTs |

| Vitamin D | 0/1 RCTs | 0/1 RCTs | 2/2 RCTs | 0/2 RCTs | 2/2 RCTs (for some of physical performance outcomes) | 1/2 RCTs (only for TUG) |

| Other | 4/6 RCTs | 0/6 RCTs | 3/5 RCTs | 0/5 RCTs | 4/5 RCTs | 2/5 RCTs |

RCTs randomized controlled trials, SPPB short physical performance battery, TUG timed up and go

Protein supplementation

Thirteen individual studies assessed the impact of a combined protein supplement and exercise intervention on the muscle function of elderly people. Most of these studies were of good quality but four were of poor quality [12, 24, 26, 29]. In three of the 13 studies, protein was combined with creatine [12], essential amino acids [24], or vitamin D [26]. Supplementation protocols were heterogeneous in terms of studied population, duration of study, and supplementation dose, which varied from 7.4 to 45 g of protein per day. Twelve studies assessed the effect of the interventions on muscle mass and/or muscle strength but only nine reported results on physical performance.

Muscle mass: Muscle mass increased significantly with exercise in 11 of the 12 included RCTs. An interactive effect of protein supplementation and exercise was reported in only three of these studies: one looked at frail individuals [33], a second has been performed in elderly sarcopenic men [25], and the third enrolled female retirement village residents whose protein supplementation was lean red meat [22]. One other study [8] reported an increase of fat-free mass and appendicular lean mass only in the group supplemented with protein and exercise but the difference between the groups was not described. Muscle strength: All studies showed a significant improvement of leg muscle strength with exercise. No additional effect of protein was seen in the majority of these studies with the exception of three studies, each one of excellent quality: Daly et al. [22] showed significant improvement in leg extension in the group receiving lean red meat (45 g of protein/day) and exercise compared to an exercise-only group and Chalé et al. [17], who showed greater improvement in knee extensor peak power after a supplementation of 40 g of protein/day and, finally, Zdzieblik et al. [25] reported that quadriceps strength of the right leg (effect on the left leg was not assessed) increased more in the group taking 15 g of collagen peptide as supplement/day. Improvement in handgrip strength was seen in one study [33] but was absent in three others [20, 24, 29]. Finally, one study [8] reported an increase of the 1 repetition maximum (1RM) knee extensors only in the group with protein combined with exercise; however, the difference between the two groups was not reported. Physical performance: All studies showed a significant improvement of at least one physical performance test with exercise. No studies showed a significant difference between the groups receiving exercise only compared to the group receiving exercise combined with protein.

Summary: Muscle mass increased with exercises in 11/12 RCTs but an additional effect of protein was found in only 3/12 RCTs; Muscle strength increased with exercises in 12/12 RCTs but an additional effect of protein was found in only 3/12 RCTs; Physical performance increased with exercise, for at least one outcome, in 9/9 RCTs with no additional effect of protein.

Essential amino acids supplementation

Three studies used essential amino acids (EAA) supplementation, 6 g/day for 3 months in sarcopenic community-dwelling older women [36], 10 g/day for 4 weeks in older adults recruited from nursing homes and adult day-care centers [27], and 12 g/day for 12 weeks in older men [35]. One study was of poor quality [35]. All three assessed the effect of intervention on muscle mass and muscle strength and two also measured the effect on physical performance [27, 36].

Muscle mass: Two studies reported an increase of muscle mass with exercise but did not report any difference between the group receiving EAA supplements and the group who did not [35, 36]. The third study did not report any increase of muscle mass, neither for subjects receiving exercises only, nor in the groups of subjects receiving a combination of exercise and EAA supplements [27]. Muscle strength: Knee extension increased with exercise in two studies but no interaction was found with EAA supplementation. In the third study, no effect on isometric leg strength was observed [27]. Physical performance: Walking speed [36] and timed up and go [27] tests improved with exercise with no additional effect of EAA supplements. Standing balance and chair-stand test did not improve with treatment [27].

Summary: Muscle mass and muscle strength increased with exercise in 2/3 RCTs with no additional effect of EAA; Physical performance (walking speed and SPPB test only) increased with exercise in 2/2 RCTs with no additional effect of EAA.

β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB) supplementation

Three studies of good quality used Ca-HMB [13, 16, 37] as a dietary supplement. In all studies, the treated group received 3 g of Ca-HMB per day. The study duration varied: 24 weeks [13], 12 weeks [37], and 8 weeks [16]. Participants were healthy ambulatory older adults in the first two studies [13, 37] and healthy adults confined to complete bed rest for 10 days for the latter [16]. All studies assessed the effect on muscle mass and muscle strength but only two assessed the effect of treatment on physical performance [13, 16].

Muscle mass: Effects of Ca-HMB supplementation on muscle mass were not consistent across the three studies. Fat-free mass significantly increased with exercise in one study but no difference was evident between the group with combined exercise + Ca-HMB and the group with exercise only [13]. Moreover, a significantly greater increase in fat-free mass was found in men from the placebo group. One study did not show any effect of the treatment on fat-free mass but did show an increase in thigh muscle area with exercise; no inter-group difference was seen [37]. Finally, the third study showed a significantly greater effect of exercise + Ca-HMB in preventing the decline of lean body mass over a period of bed rest compared to exercise only [16]. Muscle strength: Muscle strength increased in two studies with exercise but no additional effect of Ca-HMB was found. In the third study [37], no improvement in upper or lower body strength was found. Physical performance: The two studies showed an improvement in the performance of the Timed Up and Go test with exercise but did not show any added effect of nutritional supplementation and exercise. In a single study, no effect on the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) test was found [16].

Summary: Muscle mass increased with exercise in 3/3 RCTs and an interactive effect of HMB was found in 1/3 RCTs; Muscle strength increased with exercises in 2/3 RCTs with no additional effect of HMB; Physical performance increased with exercise (TUG only) in 2/2 RCTs with no additional effect of HMB.

Multi-nutrient intervention

Five studies reported results of treatment combining multi-nutrients and exercise on muscle strength; four of the five studies also looked at muscle mass and physical performance. Studies were performed on community-dwelling participants [14, 42, 43], frail retirement community residents [38], or nursing home residents [39, 40]. The majority of studies were of poor quality [14, 39, 40, 42, 43].

Muscle mass: Two out of four studies did not report any improvement in fat-free mass with exercise or with exercise combined with multi-nutrient supplementation [38, 42, 43]. Two studies reported an increase in muscle mass with exercise [14, 39, 40] but only in the cross-sectional area for the study of Fiatarone et al. [39, 40]. One of these failed to show any additional effect of nutritional supplementation [14] and the other did not describe the additional effect of multi-nutrient supplementation [39, 40]. Muscle strength: Results were heterogeneous for the five studies that assessed the combined effect of exercise and multi-nutrient supplementation on muscle strength. Two studies [14, 42] showed a significant improvement in muscle strength with exercise, one [42] did not report any additional effect of nutrition whereas the other study [14], reported greater improvement in isometric knee flexion in the group receiving combined exercise and multi-nutrient supplementation versus only exercise. Fiatarone et al. [39, 40] also reported an increase of muscle strength with exercise but did not describe the difference between the exercise only and combined multi-nutrient and exercise group. Finally, two other studies [38, 41] did not report any increase of muscle strength with treatment. Physical performance: Three studies described a significant improvement in physical performance with exercise. No additional effect of nutrition was seen in two studies [38, 42, 43]; one further study did not report whether there were any additional effect of nutrition [39, 40]. Finally, a fifth study did not show any effect of treatment on gait speed [41].

Summary: Muscle mass increased with exercises in 2/4 RCTs with no additional effect of multi-nutrient; Muscle strength increased with exercises in 3/5 RCTs and an additional effect of multi-nutrient was found in 1/5 RCTs; Physical performance increased with exercise in 3/4 RCTs with no additional effect of multi-nutrient.

Creatine supplementation

Five good-quality studies have reported results of the effects of creatine supplementation on muscle mass and muscle strength; four of these also reported effects on physical performance. The protocols of supplementation were heterogeneous with three studies using 5 g/day of creatine while the two other studies used a higher dose of creatine for the first week followed by 5 g/day in one of the study and 0.1 g/kg/day in the second study. The study duration varied from 12 weeks to 6 months.

Muscle mass: four out of the 5 studies showed greater improvement of muscle mass in the group treated with the combination of exercise and creatine compared to the control group with exercise only. The other study showed a significant increase in muscle mass with exercise but without any additional effect of creatine supplementation. Muscle strength: Muscle strength improved with exercise in all studies, with the exception of handgrip strength, which remained unchanged in one study [48]. Several studies found additional effects of creatine supplementation in addition to exercise on: bench press [11, 19, 23], knee extension [19, 48, 49], biceps curl performance [19], leg press [19], ankle dorsiflexion [48], isokinetic muscle strength [49], and, finally, endurance of knee extension [49]. Physical performance: Results were less consistent regarding physical performance. Two studies [48, 49] reported an improvement in physical performance with exercise but did not report any additional effects of creatine supplementation. One study reported no improvement in physical performance with either exercise or exercise plus creatine [11]. The final study found a greater improvement in the 30-s chair stand test and in an exercise where participants raised themselves from the floor, in the group receiving combined exercise and creatine [19].

Summary: Muscle mass increased with exercises in 5/5 RCTs and an additional effect of creatine was found in 4/5 RCTs; Muscle strength increased with exercises in 5/5 RCTs and an additive effect of creatine was found, for some of the muscle strength outcomes, in 4/5 RCTs; Physical performance increased with exercises in 3/4 RCTs and an interactive effect of creatine was found in 1/4 RCTs.

Vitamin D supplementation

Two studies [46, 47] reported effects of combined exercise and vitamin D3 supplementation on muscle strength and physical performance. One of those studies also reported effect on arm, waist and hip circumferences as well as lean mass [47]. The vitamin D3 dose was 400 IU/day for 9 months in the study of Bunout et al. [47] and 50,000 IU/week (after an initial injection of 100,000 IU at study entry) for 8 weeks for the study of Binder et al. [46]. This last study was graded as having a poor quality [46] whereas the study of Bunout et al. [47] was a good-quality study.

Muscle mass: Only one study reported results on muscle mass [47]. No effects of exercise alone or of exercise combined with vitamin D supplementation were observed. Indeed, no significant changes in weight, circumferences, or body composition measured by DXA were observed in any of the groups. Muscle strength: Both studies reported significant improvement in muscle strength with exercise but did not report any difference between the exercise-only group and the group with combined exercise and vitamin D supplementation. Physical performance: Binder et al. [46] reported improved balance with exercise in a population of elderly nursing home residents with dementia. No additional effect of vitamin D supplementation was found and no improvement in gait speed was evident in either group. Bunout et al. [47] reported a significant improvement in the Timed Up and Go test for the group with combined vitamin D and exercise but no difference for the SPPB test between groups.

Summary: Muscle mass did not improve with exercise and no additional effect of vitamin D was found; Muscle strength increased with exercise in 2/2 RCTs with no additional effect of vitamin D; Physical performance increased, for some of the physical performance outcomes, in 2/2 RCTs with no additional effect of vitamin D, except for TUG in 1/2 RCTs.

Other supplementation

Our systematic review identified six studies of good quality that used other types of nutritional supplements: green tea in elderly men and women [15], magnesium oxide in healthy elderly subjects [21], milk fat globule membrane in frail women [28], soy isoflavones in frail older women [9, 10], vitamin and mineral-enhanced dairy and fruit products in frail community-dwelling older people [44, 45] and finally, tea catechin in sarcopenic women [18]. Four studies were 12 weeks in length [15, 18, 21, 28], one was 6-months in length [9, 10], and the last one was 17 weeks in length [44, 45].

Muscle mass: A significant effect of exercise alone on muscle mass was seen in various studies: in waist and hip circumference in men in the green tea [15] study, hip circumference in the soy isoflavones [9, 10]study participants, lean mass in the vitamin and mineral-enhanced dairy and fruit products [44, 45]study, and leg lean mass in tea catechin [18]. No additional effects of nutritional supplements were observed across studies. Muscle strength: Exercise increased bench press and 1RM leg press without an additional effect of soy isoflavones [9, 10] and knee extension without additional effects of tea catechin [18]. A small increase of quadriceps strength was also shown in one study but the difference between groups was not described [44, 45]. No effect of treatment was found on knee extension and handgrip strength in the other studies [9, 10, 21, 28]. Physical performance: Exercise combined with magnesium oxide significantly improved performance in the SPPB test, the chair stand test, and in the 4-m walking speed in the study of Veronese et al. [21]. TUG, usual gait speed, and maximum walking speed significantly improved in the exercise + tea catechin group compared to exercise group only in another study of Kim et al. [18] Walking speed and TUG test performance also improved with exercise in the study of Kim et al. [28] but no additional effect of milk fat globule membrane was described. In the study by Chin A Paw et al., improvements in physical performance were described but the additional effect of vitamin- and mineral-enhanced dairy and fruit products was not described [44, 45]. Finally, the chair stand test did not improve with treatment in two other studies [9, 10, 18].

Summary: Muscle mass increased with exercise in 4/6 RCTs and no additional effect of nutrition was found; Muscle strength increased with exercise in 3/5 RCTs and no interactive effect of nutrition was found; Physical performance increased with exercise in 4/5 RCTs and an additional effect of nutrition was found in 2/5 RCTs.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to summarize results of RCTs assessing the effect of an intervention combining physical activity and dietary supplement on muscle mass and muscle function of subjects aged 60 years and older. Following a systematic review previously performed in 2013 by Denison et al. including 17 RCTs, we performed an update of this comprehensive systematic review and identified 21 RCTs published between April 2013 and October 2015. Thus, 37 RCTSs assessing the impact of a therapeutic intervention containing both physical activity and a nutritional supplement on muscle parameters were included in the present work. The study protocols were quite heterogeneous. Different types of physical activities have been studied in different populations that varied in sex, settings, and health status. Moreover, within each category of dietary supplements, the supplement dose and the length of study differed across RCTs.

Among the 37 RCTs included in the systematic review, 34 RCTs assessed the impact of intervention on muscle mass in elderly subjects. In almost 80% of the RCTs (27/34 RCTs), muscle mass increased with exercise training. In the majority of studies where no effect of exercise was observed, these were undertaken in frail subjects, residing in a nursing home, or, subjects with limited mobility. A hypothesis could be that the physical condition of these subjects did not allow them to perform the protocol for the physical activity intervention correctly. The majority of studies proposed three sessions per week. Fewer sessions may compromise efficacy of the physical activity intervention. An additional effect of nutritional intervention on muscle mass was only found in 8 RCTs (23.5%), which were all of high quality (4 or 5 points in the Jadad Scale), 4 using creatine, 3 using proteins, and 1 using HMB as dietary supplement. The majority (75%) of studies using creatine as a dietary supplement showed a higher effect on muscle mass once exercise intervention was combine with creatine. The combination of creatine supplementation and resistance training therefore seems to act synergistically. Only 3 of the 12 RCTs using protein as a dietary supplement reported an additional effect of protein when combined with physical activity. These three studies varied in type and dose of protein with no specific similarity between them that could explain their positive results as distinct from the other nine studies that did not report an effect on mass muscle with protein. Because of blunted response in muscle protein synthesis in older adults and reduced post-prandial inhibition of muscle protein breakdown, some authors recommended increasing protein intake to 1.2 g/kg body weight/day in older adults and even more in frail older adults or elderly with acute or chronic disease [50, 51]. Based on these recommendations, we hypothesized a beneficial effect of protein supplementation in muscle function in older people. However, it should be discussed that the baseline dietary intake of protein has not been reported in the different studies. Therefore, we do not know if the target of 1.2 g/kg/day has been reached or if differences could have been observed between populations who reached this target and those who did not. A meta-analysis published in 2012 [52] showed a positive effect of protein supplementation on muscle mass gains during prolonged resistance-type exercise training in older subjects. This probably means that the type of exercise training could have a non-negligible impact on results. Indeed, in this systematic review, inclusion criteria were not limited to one particular type of physical exercise. Finally, one out of the three studies using HMB as a dietary supplement also showed an intergroup difference between subjects undergoing exercise intervention and subjects undergoing a combination of exercise and dietary intervention. Of note, this study comprised subjects confined to bedrest. Subjects receiving a combination of exercise and HMB supplementation were more prevented for decline of lean body mass over bed rest compared to subjects undergoing exercises only. In this study, HMB supplementation did not increase muscle mass but prevented its decline.

Muscle strength increased in 82.8% of the studies (29/35 RCTs) following an exercise intervention and, once again, dietary supplementation showed additional benefits in only a small number of studies (8/35 RCTS, 22.8%) principally for creatine but only at specific muscle sites. In 4 out of the 5 RCTs using creatine as a dietary supplement (dose range 5–20 g/day), the group treated with the combination of exercise and dietary intervention showed greater improvement of muscle strength compared to exercise only. Three good-quality RCTs using protein as a dietary supplement also showed a greater effect on muscle strength when compared to the exercise group. These three studies were providing a high amount of protein with, respectively, 45, 40, and 15 g (collagen peptide) daily whereas the mean dose of supplementation in other studies was approximately 20 g/day. The dose of supplementation is likely to contribute to the inconsistent findings between studies. Handgrip strength, a component of sarcopenia definitions, was an outcome in 13 RCTs assessing the effect of a combined exercise and dietary intervention. Approximately half of the studies (6/13 RCTs) showed an improvement in grip strength with exercise. However, none of these RCTs showed an additional effect of dietary supplementation. Highlighted by these last results, it should be noted that, even if this systematic review revealed an increase of muscle strength following exercise in the majority of the studies, this seems particularly true for leg muscle strength.

A total of 29 RCTs also assessed the impact of combined physical activity and dietary supplementation on physical performance. We observed, in the majority of studies, an improvement in physical performance outcomes following an exercise intervention (26/28 RCTs, 92.8%). In the two studies that did not report an improvement on physical performance, one was performed on frail people and the other one on hospitalized people. Physical performance was assessed using a variety of measures in the reported studies. The most commonly used measures were gait speed (used in 17 RCTs), followed by chair stand test (used in 13 RCTs), Timed Up and Go test (used in 8 RCTs), and SPPB test (used in 6 RCTs). The heterogeneity of both the type of exercise intervention and physical performance outcomes impedes general statements of findings on the association between exercise training and improvements in physical performance. Interaction of exercise and nutrition was found in only 17.8% of these studies (5/28 RCTs): one study when a multi-nutrient was used as a dietary supplement, another with creatine, a third study with vitamin D, another with tea catechin, and finally, one with magnesium oxide.

This study is an update of an existing systematic review and it followed the same rigorous methodology as the previous one. We searched multiple electronic databases to identify as many studies as possible that would meet our inclusion criteria. Nevertheless, this review is limited by the disparity between the studies. The exercise interventions described in the RCTs varied in regards of the types of exercises, doses, intensity, and duration. Moreover, adherence to these protocols were not reported, which impacts the assessment of the real effect of exercise on muscle features. Supplementations provided also varied, not merely for the dosage, but also for the duration, the way, and the frequency of administration. It must also be noted that half of these studies were not double blinded. These parameters are likely to be key factors in modulating the outcomes of studies investigating the potential benefit of dietary supplementation to further augment gains in muscle mass and strength during exercise training. Moreover, the majority of individual RCTs did not take into account the baseline nutritional status of the population. It makes perfect sense that elders, close to undernutrition in some of the dietary supplements presented, failed to respond properly to exercise training meant to increase their muscle mass and strength. Even a reasonable dose of the supplement may be insufficient if participants are very sick, frail, and/or malnourished at baseline. In the same vein, even if exercise could have a positive effect, nutritional supplement may not be effective in very healthy, fit, and/or vigorous elderly. Nutrition supplementation is likely to be more efficient if malnutrition is present. The specific elderly subpopulation should be regarded when evaluating the need for nutritional support during exercise training. Finally, even if our purpose was to assess combined effects of exercise training and dietary supplementation on muscle outcomes in sarcopenic subjects, a very limited number of included studies have been performed specifically on subjects affected by sarcopenia. Because of the condition of sarcopenic patients, it is likely that the effects observed in this systematic review would have been lesser in solely sarcopenic patients. It was however difficult for this study to focus only on sarcopenic subjects. Indeed, there are no universally accepted criteria for the diagnosis of sarcopenia in an operational sense. Therefore, we chose to focus on elderly subjects in a broader sense instead of focusing on one or more restricted definitions of sarcopenia.

In conclusion, physical exercise has a beneficial impact on muscle mass, muscle strength, or physical performance in healthy subjects aged 60 years and older. However, the additional effect of dietary supplementation has only been reported in a limited number of studies. For the majority of studies included in this systematic review, the population was composed of healthy older subjects. Studies assessing the impact of a combined exercise intervention and dietary intervention are still lacking in frail and sarcopenic populations, populations suffering from nutritional deficiency, or populations at risk of malnutrition. Further well-designed and well-conducted studies performed on these types of populations should be implemented. It seems likely that nutritional interventions in populations who are presenting nutritional or physical deficiencies would be more beneficial than interventions in well-nourished and replete populations. There is a need of a rigorous documentation of subject’s baseline exercise level and nutritional status prior to implement intervention regimens in those future studies.

Appendix

the IOF-ESCEO Sarcopenia Working Group

G. Adib

M. L. Brandi

T. Chevalley

P. Clark

B. Dawson-Hughes

A. El Maghraoui

K. Engelke

R. Fielding

A. J. Foldes

G. Gugliemi

J. M. Kaufman

B. Larijani

W. Lems

L. J. C. van Loon

G. P. Lyritis

S. Maggi

L. Masi

E. McCloskey

O. D. Messina

A. Papaioannou

P. Szulc

N. Veronese

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

N Binkley received research support from Amgen, GE Healthcare, and Lilly, Merck and consultant/advisory board fees from Amgen, Astellas, Lilly, Merck, Nestle, and Radius. J-Y Reginster received consulting fees or paid advisory boards from Servier, Novartis, Negma, Lilly, Wyeth, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Merckle, Nycomed-Takeda, NPS, IBSA-Genevrier, Theramex, UCB, Asahi Kasei, Endocyte, and Radius Health; lecture fees from Merck Sharp and Dohme, Lilly, Rottapharm, IBSA, Genevrier, Novartis, Servier, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Merckle, Teijin, Teva, Analis, Theramex, Nycomed, NovoNordisk, Ebewee Pharma, Zodiac, Danone, Will Pharma, Amgen, and PharmEvo; and grant support from Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Rottapharm, Teva, Roche, Amgen, Lilly, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Servier, Pfizer, Theramex, Danone, Organon, Therabel, Boehringer, Chiltern, and Galapagos. ML Brandi is a consultant and grant recipient from Alexion, Abiogen, Amgen, Bruno Farmaceutici, Eli Lilly, MSD, NPS, Shire, SPA, and Servier. C Beaudart, A Dawson, S Shaw, N Harvey, JA Kanis, R Chapurlat, D Chan, O Bruyère, R Rizzoli, C Cooper, EM Dennison, G Adib, T Chevalley, P Clark, B Dawson-Hughes, A El Maghraoui, K Engelke, R Fielding, J Foldes, G Guglielmi, JM Kaufman, B Larijani, W Lems, L van Loon, G Lyritis, S Maggi, L Masi, E McCloskey, OD Messina, A Papaioannou, P Szulc, and N Veronese have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

This paper has been endorsed by the Committee of Scientific Advisors of the IOF.

Contributor Information

C. Cooper, Email: cc@mrc.soton.ac.uk

the IOF-ESCEO Sarcopenia Working Group:

G. Adib, M. L. Brandi, T. Chevalley, P. Clark, B. Dawson-Hughes, A. El Maghraoui, K. Engelke, R. Fielding, A. J. Foldes, G. Gugliemi, J. M. Kaufman, B. Larijani, W. Lems, L. J. C. van Loon, G. P. Lyritis, S. Maggi, L. Masi, E. McCloskey, O. D. Messina, A. Papaioannou, P. Szulc, and N. Veronese

References

- 1.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39:412–423. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper C, Fielding R, Visser M, et al. Tools in the assessment of sarcopenia. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;93:201–210. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9757-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaudart C, Rizzoli R, Bruyère O, et al. Sarcopenia: burden and challenges for public health. Arch Public Heal. 2014;72:45. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruyère O, Beaudart C, Locquet M, et al. Sarcopenia as a public health problem. Eur Geriatr Med. 2016;7:272–275. doi: 10.1016/j.eurger.2015.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Schneider SM, et al. (2014) Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: a systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Denison HJ, Cooper C, Sayer AA, Robinson SM. Prevention and optimal management of sarcopenia: a review of combined exercise and nutrition interventions to improve muscle outcomes in older people. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:859–869. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S55842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gryson C, Ratel S, Rance M, et al. Four-month course of soluble milk proteins interacts with exercise to improve muscle strength and delay fatigue in elderly participants. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(958):e1–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lebon J, Riesco E, Tessier D, Dionne IJ. Additive effects of isoflavones and exercise training on inflammatory cytokines and body composition in overweight and obese postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2014;21:869–875. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choquette S, Dion T, Brochu M, Dionne IJ. Soy isoflavones and exercise to improve physical capacity in postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2013;16:70–77. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2011.643515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gualano B, Macedo AR, Alves CRR, et al. Creatine supplementation and resistance training in vulnerable older women: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Exp Gerontol. 2014;53:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villanueva MG, He J, Schroeder ET. Periodized resistance training with and without supplementation improve body composition and performance in older men. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114:891–905. doi: 10.1007/s00421-014-2821-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stout JR, Smith-Ryan AE, Fukuda DH, et al. Effect of calcium β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (CaHMB) with and without resistance training in men and women 65 + yrs: a randomized, double-blind pilot trial. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okazaki K, Yazawa D, Goto M, et al. Effects of macronutrient intake on thigh muscle mass during home-based walking training in middle-aged and older women. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2013;23:e286–e292. doi: 10.1111/sms.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narotzki B, Reznick AZ, Navot-Mintzer D, et al. Green tea and vitamin E enhance exercise-induced benefits in body composition, glucose homeostasis, and antioxidant status in elderly men and women. J Am Coll Nutr. 2013;32:31–40. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2013.767661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deutz NEP, Pereira SL, Hays NP, et al. Effect of β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB) on lean body mass during 10 days of bed rest in older adults. Clin Nutr. 2013;32:704–712. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chalé A, Cloutier GJ, Hau C, et al. Efficacy of whey protein supplementation on resistance exercise-induced changes in lean mass, muscle strength, and physical function in mobility-limited older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:682–690. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H, Suzuki T, Saito K, et al. Effects of exercise and tea catechins on muscle mass, strength and walking ability in community-dwelling elderly Japanese sarcopenic women: a randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13:458–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aguiar AF, Januário RSB, Junior RP, et al. Long-term creatine supplementation improves muscular performance during resistance training in older women. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:987–996. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2514-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leenders M, Verdijk LB, Van der Hoeven L, et al. Protein supplementation during resistance-type exercise training in the elderly. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:542–552. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318272fcdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veronese N, Berton L, Carraro S, et al. Effect of oral magnesium supplementation on physical performance in healthy elderly women involved in a weekly exercise program: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:974–981. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.080168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daly RM, O’Connell SL, Mundell NL, et al. Protein-enriched diet, with the use of lean red meat, combined with progressive resistance training enhances lean tissue mass and muscle strength and reduces circulating IL-6 concentrations in elderly women: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:899–910. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.064154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]