Abstract

Microtubule-based motors carry cargo back and forth between the synaptic region and the cell body. Defects in axonal transport result in peripheral neuropathies, some of which are caused by mutations in KIF5A, a gene encoding one of the heavy chain isoforms of conventional kinesin-1. Some mutations in KIF5A also cause severe central nervous system defects in humans. While transport dynamics in the peripheral nervous system have been well characterized experimentally, transport in the central nervous system is less experimentally accessible and until now not well described. Here we apply manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance (MEMRI) to study transport dynamics within the central nervous system, focusing on the hippocampal-forebrain circuit, and comparing kinesin-1 light chain 1 knock-out (KLC-KO) mice with age-matched wild-type littermates. We injected Mn2+ into CA3 of the posterior hippocampus and imaged axonal transport in vivo by capturing whole-brain 3D magnetic resonance images (MRI) in living mice at discrete time-points after injection. Precise placement of the injection site was monitored in both MR images and in histologic sections. Mn2+-induced intensity progressed along fiber tracts (fimbria and fornix) in both genotypes to the medial septal nuclei (MSN), correlating in location with the traditional histologic tract tracer, rhodamine dextran. Pairwise statistical parametric mapping (SPM) comparing intensities at successive time-points within genotype revealed Mn2+-enhanced MR signal as it proceeded from the injection site into the forebrain, the expected projection from CA3. By region of interest (ROI) analysis of the MSN, wide variation between individuals in each genotype was found. Despite this statistically significant intensity increases in the MSN at 6 hr post-injection was found in both genotypes, albeit less so in the KLC-KO. While the average accumulation at 6 hr was less in the KLC-KO, this difference did not reach significance. Projections of SPM T-maps for each genotype onto the same grayscale image revealed differences in the anatomical location of significant voxels. Although KLC-KO mice had smaller brains than wild-type, the gross anatomy was normal with no apparent loss of septal cholinergic neurons. Hence anatomy alone does not explain the differences in SPM maps. We conclude that kinesin-1 defects may have only a minor effect on the rate and distribution of transported Mn2+ within the living brain. This impairment is less than expected for this abundant microtubule-based motor, yet such defects could still be functionally significant, resulting in cognitive/emotional dysfunction due to decreased replenishments of synaptic vesicles or mitochondria during synaptic activity. This study demonstrates the power of MEMRI to observe and measure vesicular transport dynamics in the central nervous system that may result from or lead to brain pathology.

Keywords: Kinesin-1, kinesin light chain-1, axonal transport, manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI), hippocampal-forebrain circuit, statistical parametric mapping

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Within the brain, neurons extend processes across long distances to reach distal targets. The axonal transport system, which depends on microtubule-based motors, carries information and building blocks within these long processes to create and maintain distant synapses. Kinesins, a family of microtubule-based motor proteins, walk along microtubules carrying cargo towards pre-synaptic termini (Hirokawa et al., 2009; Vale et al., 1985; Yildiz et al., 2004). Kinesin-1, the most abundant of this motor family in brain, is a heterotetramer with two heavy chains and two light chains. The heavy chains encode the motor domain while light chains are involved in cargo binding. KIF5 genes (KIF5A, B and C) encode kinesin-1 heavy chains in mouse (Gudkov et al., 1994; Nakagawa et al., 1997; Niclas et al., 1994; Xia et al., 1998), and four other genes encode kinesin light chains (KLC1, KLC2, KLC3 and KLC4) (Chung et al., 2007; Ota et al., 2004; Rahman et al., 1998), all of which appear to interact with any KIF5. All three KIF5s are expressed in brain, as well as at least two of the light chains, KLC1 and KLC2 (Rahman et al., 1998). Kinesin-1 has been implicated in transport of synaptic vesicles (Sato-Yoshitake et al., 1992), amyloid precursor protein (Kamal et al., 2001; Kamal et al., 2000; Satpute-Krishnan et al., 2006; Seamster et al., 2012), neurofilaments (Li et al., 2012; Xia et al., 2003), post-synaptic neurochemical receptors (Hirokawa et al., 2010), endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi membranes (Lippincott-Schwartz et al., 1995), and mitochondria (Campbell et al., 2014). Defects in kinesin-1 have been implicated in accelerating Alzheimer’s disease (Stokin et al., 2005), activation of axonal stress kinase with enhanced phosphorylation of tau (Falzone et al., 2010) and abnormal proteasome transport and distribution (Otero et al., 2014). Human genetic defects in genes encoding transport motors, such as kinesin subunits, are rare and correlate with peripheral neuropathology (Djagaeva et al., 2012; Musumeci et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2001). In some cases, symptoms of central nervous system defects are also present in patients with KIF5A mutations, including pyramidal dysfunction (Liu et al., 2014), and cognitive impairment (Hamdan et al., 2011). While much is known about the molecular structure and motor activity of kinesin-1 both in vitro and ex vivo, its transport activity within the living brain has thus far only been inferred. Since other kinesin family members are also expressed in brain, it is of interest to learn what the contribution of kinesin-1 is to organelle/vesicular transport within the central nervous system.

Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI) provides an experimental approach to study organelle transport dynamics in the living brain (Bearer et al., 2007b; Bearer et al., 2009; Gallagher et al., 2013; Gallagher et al., 2012; Pautler et al., 2003; Pautler et al., 1998; Smith et al., 2007). Mn2+, a divalent paramagnetic ion, produces a hyper-intense signal by T1-weighted MRI and thus acts as a contrast agent for MR imaging. Mn2+ enters active neurons through the voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (Finley, 1998; Merritt et al., 1989; Takeda, 2003) and is secondarily taken up by intracellular organelles that are then transported along axons (Massaad and Pautler, 2011). We assume that transport of Mn2+ represents a general measure of vesicular transport in axons, involving a wide variety of organelle cargoes, each moving in association with a set of motors with various subunit composition. Our work in the optic tract demonstrated that KLC1-dependent transport represented only a third of the total Mn2+ transport (Bearer et al., 2007a). Thus, MEMRI can be used to study transport dynamics during progression or experimental treatment of neurodegenerative disease in pre-clinical animal models without particular organelle or specific motor bias, where particular focus has been on accumulation in the olfactory bulb after nasal delivery (Cross et al., 2008; Majid et al., 2014; Pautler et al., 1998; Smith et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012).

Previously we reported that disruption of the kinesin-1-based transport system influenced the rate of Mn2+ transport in the optic nerve (Bearer et al., 2007a). We and others have determined a dose and volume of Mn2+ that is non-toxic in either the eye or brain (Bearer et al., 2007a; Eschenko et al., 2012; Lindsey et al., 2013). To measure the rate of Mn2+ transport in a kinesin-1 defective mouse, we used a transgenic mouse whose gene for one of the kinesin-1 subunits, kinesin-1 light chain 1, had been knocked out (KLC-KO). KLC1 is the most abundant of the kinesin light chains expressed in brain, and this KLC-KO mouse displays defects in the behavior of the kinesin heavy chain (Rahman et al., 1999). KLC-KO are smaller than their littermates and display pronounced motor disabilities (Rahman et al., 1999). In the optic nerve KLC-KO mice displayed delayed transport of Mn2+ (Bearer et al., 2007a). No increased vulnerability to Mn2+ was observed in the KLC-KO in that study. Thus Mn2+ transport in the optic nerve is in part dependent on intact kinesin-1 function.

Here we selected the hippocampal-forebrain circuit to investigate the contribution of kinesin-1 to intracerebral transport. Neurons in CA3 of the hippocampus project to the septal nuclei via the hippocampal fimbria and the fornix in fiber bundles large enough to be imaged by MR in living mice with a 90µm isotropic voxel resolution (Bearer et al., 2007b; Gallagher et al., 2012). Indeed, Mn2+ transport dynamics are altered within hippocampal-forebrain projections in Down Syndrome (Bearer et al., 2007b) and in amyloid precursor protein (APP) knockout mice (Gallagher et al., 2012). Whether this transport depends on kinesin-1 or other kinesins is unknown.

After stereotaxic injection of Mn2+ together with the traditional histologic tracer, rhodamine dextran, into CA3 of the hippocampus we imaged cohorts of KLC-KO mice and their age-matched wild-type (WT) littermates by time-lapse, whole brain, high-field MRI and, after sacrifice, by fluorescence microscopy of the traditional tract-tracer. To obtain an unbiased comprehensive evaluation of Mn2+ transport, we aligned cohorts of MR brain images of individual KLC-KO and wild-type littermates, each captured at three time-points after injection, and performed statistical parametric mapping (SPM), which identifies all voxels displaying increased intensity values between time-points. To compare between genotypes, we measured Mn2+-induced intensity differences in the target area. We confirmed SPM results with region of interest analysis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mouse lines were obtained from Larry S. Goldstein at UC San Diego (Bearer et al., 2007a; Falzone et al., 2010; Falzone et al., 2009; Rahman et al., 1999). Mice were bred from heterozygotes, producing knockouts, heterozygotes and wild-type littermates and littermates imaged at 8-13 months of age. Equal numbers of male and female were included in each group. Genotyping was performed by PCR of the tail (Bearer et al., 2007a; Rahman et al., 1999). While the mice tolerated the Mn2+ injection without apparent distress, some did not survive in the vertical bore MR scanner under anesthesia for 102 min scans three times over a 25-hour period necessary to complete the time-lapse imaging sequence to detect transport. We imaged 19 individual mice and selected only those with consistent placement of the injection site who also survived the entire 2-week experimental sequence for analysis (n=10). Pairs of KLC-KO and wild-type were often from the same litter. All experimental procedures received prior approval by Caltech, Brown University, and UNM IACUCs.

Stereotaxic Injection

After collection of a pre-injection image, aqueous MnCl2 (3-5 nL of 200 mM) together with 0.5 mg/ml 3k rhodamine-dextran-amine (RDA) (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) were injected into the right hippocampus (coordinates × 3.2 mm (right of midline), y −4.1 mm (posterior to Bregma), z 3.4 mm (down from brain surface)) similar to the procedure described in Bearer et al., 2007 (Bearer et al., 2007b). We have previously reported that this volume (3-5 nL) and concentration (200-500 mM) does not produce detectible injury by histologic analysis (Bearer et al., 2007b; Gallagher et al., 2012), and did not observe any here. Coordinates were selected based on pre-injection image and mouse brain atlas (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). Since precise volumes of injectate in the nanoliter range are difficult to control, we calculated an amount of Mn2+ that would be non-toxic yet “saturate” the uptake system as determined by Mn2+-induced intensity remaining at the injection site throughout the experiment (Bearer et al., 2007a). Review of histologic sections of brains after injection with this volume and concentration of Mn2+ show no significant evidence of cellular toxicity (Bearer et al., 2007b; Bearer et al., 2009; Gallagher et al., 2013; Gallagher et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2010).

The actual placement of the injection site was calculated from aligned MR images as previously described (Bearer et al., 2007b; Bearer et al., 2009; Gallagher et al., 2013; Gallagher et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2010). Briefly, aligned images are projected onto the atlas and the point of hyper-intensity identified in atlas coordinates. The centroid was calculated in Excel as the common least distance between injection sites in a 3D matrix. Injection sites were projected onto the atlas in Amira to produce a 3D image. Since injection sites were projected onto the atlas, the coordinates refer to locations in the atlas for each genotype.

Manganese-enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging

An 11.7 T 89 mm vertical bore Bruker BioSpin Avance DRX500 scanner (Bruker BioSpin Inc, Billerica, MA) equipped with a Micro2.5 gradient system was used to acquire all mouse brain images with a 35 mm linear birdcage radio frequency (RF) coil. For in vivo imaging the animal’s head was secured in a Teflon stereotaxic unit within the RF coil to minimize movement and to aid in reproducible placement. Temperature and respiration were continuously monitored during data acquisition and remained within normal ranges (Zhang et al., 2010). We employed a 3D RARE imaging sequence (Hennig et al., 1986) with RARE factor of 4, 4 averages, TR/TEeff= 300 ms/11 ms; matrix size of 256×160×128 and FOV 23.04 mm ×14.4 mm × 11.52mm, yielding 90 µm3 anisotropic voxels for 102 min scan time. Image collection was performed before injection and then begun at three time-points after injection (0.5 hr, 6 hr, and 25 hr) (Bearer et al., 2007b). Time of imaging throughout the paper refers to the start of the imaging time after injection.

Registration and Statistical Parametric Mapping

To perform statistical comparisons across time-points and between genotypes, co-registration of the images is required. All alignments began by converting the Bruker Paravision format to Analyze 7.5 (.hdr/.img) (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) or to NIFTI (.nii) format (Modat). For within genotype analysis, pre-injection and post-injection whole head scans for both genotypes were skull-stripped to segment the brain tissue from the rest of the tissue in the head initially using the multitracer semi-automated tool, tracewalker, from the LONI website (http://www.loni.usc.edu) (Woods, 2003). This method required some manual correction of the output mask (Hayes et al., 2014), which was time consuming. Hence we developed our own automation program to accelerate brain extraction (Delora et al., 2015).

After skull stripping, “field inhomogeneities” were corrected using the N3 method (Sled et al., 1998), the mode of the intensity histogram of each images was scaled to that of the atlas with in-house generated software (Bearer et al., 2007b; Kovacevic et al., 2005). This atlas was created in three steps using the AIR 5.2.5 package through the LONI Pipeline environment (Woods et al., 1998a; Woods et al., 1998b). First, pre-injection scans were linearly co-registered to one randomly chosen scan using a full affine 12-parameter model. The cost function used was a least squares cost function with intensity scaling. The scaling parameter in the cost function accounted for any discrepancies in intensity range that the scans may have had. The transformations from the space of each scan to the space of the randomly chosen scan were averaged accordingly such that the bias towards the randomly chosen scan was eliminated. The final step consisted of non-linearly warping of all the pre-injection scans to the unbiased atlas obtained in the second step. The polynomial warp started with a 2nd order 30-parameter model and finished with a 5th order 168-parameter model. Once the pre-injection wild-type atlas was obtained, it was then used as a template to create an averaged image for each genotype to compare intensities between time-points by following the same steps as above.

Since there was a lot of variation in voxels that were part of the hyper- and hypo- intense region around the injection site, a second mask was created for the post-injection images to exclude such voxels from the computation of the cost function at each iteration (MacKenzie-Graham A et al., 2007). The Pipeline processing environment was used to undertake these tasks (http://www.loni.usc.edu) (Rex et al., 2003). A specialized workflow computed the registration parameters using a linear affine model followed by a non-linear high degree polynomial model. Images and corresponding injection-site masks were resampled using chirp-z and nearest neighbor interpolation, respectively (MacKenzie-Graham A et al., 2007). All images were processed in parallel with the same parameters in all respects, including N3 correction, modal scaling, and alignment. The data was difficult to scale and to align due to large differences in sizes between the wild-type and the KLC-KO littermates that required large scale warping, and to the hyperintense injection site which interfered with modal scaling.

For within group analysis, statistical parametric mapping was performed in SPM8 (Penny et al., 2006) by a paired T-test between time-points to detect statistically significant intensity increases between two time-points at each voxel. This produces a 3-dimensional map of intensity changes that was expected to overlay with the known projections from CA3 of the hippocampus where tracers were injected. Despite some degree of warp artifact visible in the striatum of some individuals, no signal was detected there. Hence although alignments were not perfect, warping did not introduce signal in unexpected regions for the expected hippocampal-forebrain circuit for within group analysis, probably because pair-wise analysis compares changes over time within each individual and the warp artifacts were consistent within all scans for each individual. Even without correction for false discovery rates (FDR) and with the warping issues, we did not detect extraneous voxels outside the expected circuitry. However these issues precluded SPM analysis between genotypes in unpaired t-tests and in flexible factorial ANOVAs by SPM. For between genotype analysis, a region of interest (ROI) analysis was performed. In addition, some concern has been raised about the validity of statistical mapping (Eklund et al., 2012; Eklund et al., 2015) which lead us to measure differences between genotypes ROI.

Region of interest analysis (ROI)

To compare differences between genotype and determine the degree of intensity change, we performed ROI analyses, selecting a target region of CA3 projections in the medial septal nuclei (MSN) on the same side as the injection site, as identified by the within-group statistical mapping. A control region was chosen for each image in an area not highlighted by the statistical map, in this case we chose a region in the cortex-striatum on the contralateral side to the injection site. To ensure measurements were made in the same anatomic location of all brains in the dataset, the ROIs (control and MSN) were selected in one image and propagated to all images throughout the dataset using FIJI’s ROI manager (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/docs/guide/146-30.html). Signal intensity was background-corrected by calculating the ratio between MSN and the control region. For box plots in Figure 5B, measurements of the KLC-KO were normalized to the median of the wild-type by finding the difference between the WT and the KO medians at 0.5 hour after injection and subtracting this value from all other values in the KLC-KO dataset. Line graphs were equalized by setting the average value at 0.5 hour to 1 within each dataset and proportionally adjusting other values. Graphs were generated in Microsoft Excel and GraphPad (http://www.graphpad.com/company/). Statistical analyses (ANOVA, T-test and Tukey post-hoc) were performed on background-corrected intensity values in Excel using XLStat Toolbox (https://www.xlstat.com/en/) and on equalized data by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures and Tukey’s post-hoc testing in GraphPad. Background-corrected equalized values were used for the line graphs in Figure 5C-E.

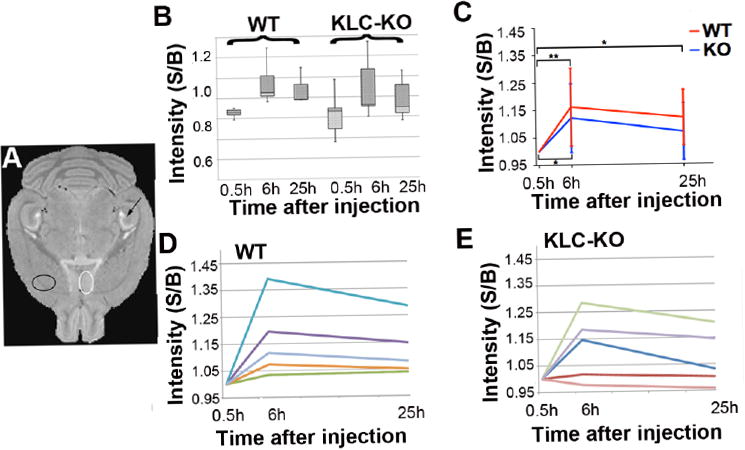

Figure 5. Region of interest analysis (ROI).

A. Locations selected for ROI analysis shown on a high-resolution template image for anatomy. White circle indicates the MSN, a location with increased intensity that differed between KLC-KO and their WT littermates as observed by visual inspection of the averaged images (Figure 3) and in T-maps of within-group between time-points (Figure 4). Black circle indicates the “control” region that had no signal by SPM and lies outside the CA3-septal circuit on the contralateral side from the injection. B. Box plot shows the distribution of background-corrected intensities in the MSN of WT and KLC-KO mice at each time-point. Data has been normalized. S/B = ratio of signal to background. C. Average intensities are shown for background-corrected, equalized data at each time-point in the WT (red) and in KLC-KO (blue). Intensity measurements were background-corrected and equalized by setting the 0.5 hour signal/background to 1.0. Error bars indicate standard deviation of the WT at 6 hours and 25 hours. Mixed model ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was used to determine significance within genotype between time-points on this corrected/equalized data. One asterisk indicates p<0.05; two asterisks indicate p<0.01. S/B = ratio of signal to background. D. and E. Line graphs showing intensity increases in background-corrected, equalized measurements over time for each animal. Each individual is represented by a different color. D, wild type (WT); and E, KLC-KO. S/B = ratio of signal to background.

Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI)

We selected two animals for DTI imaging, the two oldest in the KLC-KO and WT cohorts, as these would have the most significant differences, since age influences animal size (Rahman et al., 1999), transport rates in vitro and neurofilament aggregation (Falzone et al., 2009). Briefly, animals were sacrificed 7-8 days after imaging, and fixed by cardiac perfusion (see Histology section for fixation details). After decapitation, fixed brains in the skull were immersed in 5mM Prohance for 5 days. The two intact fixed heads were secured together in a Teflon® holder and submerged in a perfluoropolyether (Fomblin®,Solvay Solexis, Inc, Thorofare, NJ) inside a 50 ml tube and placed in the 11.7 scanner. Imaging was performed as previously described (Bearer et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010). Briefly thermostatically controlled airflow maintained the ambient bore temperature at 4 °C. Diffusion-weighted images were acquired using a conventional pulsed-gradient spin echo (PGSE) sequence (TR/ TE=300 ms/11.9 ms, 256 × 150 × 120 matrix, 25.6 mm ×15 mm × 12 mm FOV, 100 µm isotropic voxel size, 1 average, σ=3 ms, Δ=5.2 ms, Gd=1125 mT/m, nominal b-factor=3370 s/mm2). An optimized six-point icosahedral encoding scheme (Hasan et al., 2001) was used for diffusion-weighted acquisitions with a single unweighted reference image for a total imaging time of 14.5 h. The apparent diffusion tensor was calculated conventionally by inversion of the encoding b-matrix. The b-matrix for each diffusion encoding was determined by numerical simulation of the pulse sequence k-space trajectory in order to account for gradient cross-terms (Mattiello et al., 1997). Eigenvalues, eigenvectors, tensor trace and fractional anisotropy were calculated conventionally using built-in and custom MATLAB functions (The Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA). The six diffusion-weighted images were averaged to generate a high SNR isotropic diffusion-weighted image (iDWI) (Tyszka et al., 2006).

Diffusion tensor image eigenvalues (λi; trace Tr(D) and fractional anisotropy (FA) were calculated and used for a rigid body alignment (9-parameter). Registration was performed to bring these maps to the same coordinate space as the Pre-injection Atlas, using the AIR package (Woods et al., 1998a; Woods et al., 1998b). Since the FA, iDWI and TrD maps of each scan are scalar, a simple rigid body registration was performed. To create a color-coded representation of the principal eigenvector two steps were necessary: First the rigid body parameters that mapped the KO iDWI to the WT’s iDWI were used to rotate the principal eigenvectors at each voxel and afterwards to rotate the voxel grid itself. Visage Imaging's Amira (formerly Mercury's ResolveRT) software was used to perform this task (Stalling et al., 2005).

Using the FSLview tool of the FSL package (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk), the two vector fields were visualized having each x,y,z component mapped to an RGB triplet (red to left-right, green to anterior-posterior, blue to dorsal-ventral) (Aggarwal et al., 2010). The FA map was used to control the saturation of the colors. Voxels (100 µm isotropic) with null anisotropy would appear black and those with high anisotropy would appear brighter in the color indicating their maximum direction. For voxels with vector oblique to the orthogonal directions, the colors are weighted according to the components of the vector. No zero-filling was used.

Histology

All mice used in this study were prepared after live MR imaging by fixation for DTI and/or histology. Two animals were imaged by DTI first and then submitted for histology with the others. Thus we could correlate MR image results with histologic detail. Eight days after in vivo MR imaging, each mouse was anesthetized, sacrificed and fixed by transcardial perfusion, beginning with a 30 ml washout with warm heparinized phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 30 ml of room temperature 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS at a rate of 5 ml/min (Bearer et al., 2007b). After decapitation the head was rocked in 4% PFA in PBS overnight at 4°C. Then brains were dissected from the calvarium and sent to Neuroscience Associates (NSA, Knoxville, TN). The two brains selected for DTI were imaged within the skull first and then dissected and sent to NSA. All brains from this study were embedded in two groups into two gelatin blocs and serially sectioned in the coronal plane at 35 μm. Each 24th section was collected into the same cup, producing 24 cups, each containing serial sections of all brains embedded in the block across the complete brain from olfactory bulb to spinal cord at 840 µm intervals. Sets of serial sections in one cup or multiple cups were then selected for staining with Thionine/Nissl for anatomy, Campbell Switzer silver for amyloid plaques and phospho-tau (Switzer, 1993; Wang et al., 2011), anti-choline acetyl transferase (ChAT) immunohistochemistry (IHC) for cholinergic neurons (Bearer et al., 2007b; Gallagher et al., 2013; Gallagher et al., 2012), anti-AT8 IHC for phosphorylated tau, or mounted unstained in anti-quench (Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA) for imaging RDA fluorescence. The anti-quench contains Hoechst reagent that stains nuclear DNA and thus provides an anatomical reference. Since alternate sets of serial sections were used for different histology, no single region was sampled in its entirety with one staining procedure. For example we did not stain serial sections through the entire hippocampus or MSN with one stain. Sections were imaged on a Zeiss ZO1 Axioscope fluorescence microscope equipped with neofluor objectives (5, 10, 20, 40, 63 and 100×), and captured on an AxioCam MRM digital camera in the Bearer lab and Zeiss Axioplan II Imaging, Photomicroscope III, and SV11 dissecting scope at the Central Microscopy Facility at the Marine Biological Laboratory; on a Nikon Eclipse Ci brightfield clinical microscope with a DS L3 cooled digital camera; or on a Zeiss V8 zoom stereoscope with AxioCam for lower magnification of whole brain sections.

Brain volume

The volume of the brains was determined in two ways: 1) MR brain images after skull stripping and prior to alignment were measured in FSLstats as we previously described (Delora et al., 2015); and 2) the width was measured with a micrometer in 4 coronal histologic sections through Bregma 1.18mm, 0.22mm, -1.06mm and -2.6mm. In addition, brains stained for solochrome, which preferentially highlights white matter and fiber tracts, were imaged at higher magnification and the width of the corpus callosum measured with DS L3 imaging software. Results were analyzed in Excel for within-group and between-group size differences.

Results

Injection Location

All stereotaxic injection locations lie within CA3 of the right posterior hippocampus (Figure 1A). As shown, the average injection site (± standard deviation) was: x (lateral to midline) 3.3 ± 0.2 mm; y (anterior posterior with reference to Bregma) -4.3 ± 0.4 mm; z (dorsal ventral from the brain surface) -3.5 ± 0.5 mm, as we have previously reported (Bearer et al., 2007b; Gallagher et al., 2012). Injection sites lay at an average distance of 0.57 mm ± 0.35 of the centroid, as determined by image analysis of the post injection MR images begun 0.5 hr after injection, demonstrating a fairly consistent placement of tracer within all brains in the datasets (Figure 1B). Because of the smaller size of the KLC-KO brains, the actual distance between injection sites would be smaller than in wild-type littermates. Since this analysis was done on aligned images, the anatomic coordinates are the same between the two genotypes.

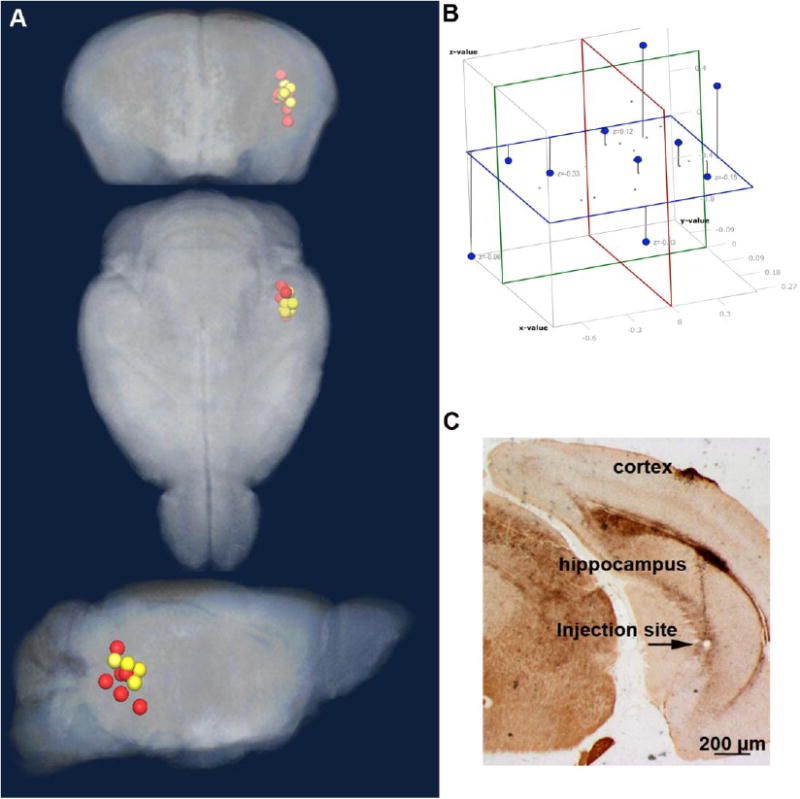

Figure 1. Injection site analysis.

A. The location of the injection site determined from analysis of the aligned MR images is shown as projected onto the pre-injection atlas three dimensional image. Wild-type (WT) littermates (yellow); KLC-KO (red). B. To measure the distance between all sites in the dataset, a 3D coordinate system was developed. The average position in the x,y,z axes of all injection sites shown as a Cartesian coordinate system, with x plane (blue), y plane (green), z plane (red). C. An example of histologic examination of brain sections from the same mice imaged by MR showing a tiny injection site in CA 3 of the posterior hippocampus with minimal damage, as detected in this Campbell-Switzer-stained section.

Further confirmation of consistent placement of the injection within CA3 of the hippocampus was obtained from histologic sections (Figure 1C). The injection site in CA3 of the right posterior hippocampus was clearly visible in histologic sections (Figure 1C). Histologic examination of both wild-type and KLC-KO in Nissl-, Campbell Switzer-, or AT8 (phospho-tau)-stained sections revealed similar features and little to no AT8 staining, suggesting similar low levels of tissue injury due to the injection in both genotypes.

Histologic analysis of traditional tracer

We co-injected the classical tract tracer, rhodamine-dextran-amine (RDA), with Mn2+. RDA allowed detection of the injection site and distal transport by fluorescence microscopy in histologic sections prepared from the same brains imaged by MR (Bearer et al., 2007b; Bearer et al., 2009). To determine that the injection sites were placed appropriately to introduce tracer into the CA3-septal forebrain circuit, we reviewed in histologic sections of all brains in the dataset by fluorescence, which detects the transport of the traditional tract-tracer, rhodamine dextran (RDA). RDA fluorescence was found as expected in the medial septal nucleus (MSN) of the wild-type (Figure 2A), a known target of CA3 neurons. In the KLC-KO mice, RDA fluorescence was qualitatively less bright in the MSN (Figure 2B), suggesting decreased transport, although the degree of decrease would be difficult to quantify from these fluorescent images. These results demonstrate that the injection site was placed correctly in CA3 for uptake and transport to expected distal projections into the basal forebrain.

Figure 2. Analysis of the medial septal nuclei by histology.

A and B. Shown are examples of fluorescent images of the co-injected RDA in histologic sections through the medial septal nucleus (MSN), a major projection from CA3 of the hippocampus. WT (A) and KLC-KO (B). Note that RDA signal appears qualitatively weaker in the MSN of the KLC-KO (B) than the WT (A), possibly due to decreased transport. C and D. Examples from serial sections adjacent to those in A-B also through the MSN that were stained for ChAT, a marker of cholinergic neurons. No obvious difference in numbers of these neurons is apparent in these examples. At higher magnification (not shown) no abnormal axonopathies (swellings or varicosities) were observed.

In the KLC knockout (KLC-/-) in a wild-type background, no obvious change in the numbers of cholinergic neurons in the MSN compared to wild-type littermates was found, nor were any differences in axonal morphology of cholinergic neurons apparent between the two genotypes (Figure 2C and D). Decreases in the numbers of these neurons could affect the amount of transport, and alterations in these neurons have been reported in KLC-KO+/- when also expressing mutant amyloid precursor protein (Stokin et al., 2008; Stokin et al., 2005) or mutant tau protein (Falzone et al., 2010). Since only one section through the MSN was available for ChAT staining, a statistical comparison to determine whether there were a minor yet significant difference not apparent by visual inspection was not performed here.

Time-lapse MEMRI suggests minor delays in transport from CA3 in the hippocampus into the basal forebrain in KLC-KO mice: Within genotype time-dependence observed by statistical parametric mapping

To image transport over time in living animals and quantify differences in genotypes, we used MEMRI followed by statistical parametric mapping (SPM). Paired t-tests between time-points with SPM provides an un-biased method to detect any voxel with statistically significant intensity changes between time-points within each group. After injection, we collected 3D whole brain T1-weighted MR images at successive time-points after co-injection of Mn2+ into CA3 of the posterior hippocampus (0.5 hr, 6 hr and 25 hr) (Figure 3). Aligned images display distinct anatomical features as is typically witnessed in T1-weighted mouse brain images and retained with our alignment strategy, as previously reported (Bearer et al., 2007b; Bearer et al., 2009). A precisely located injection site (a hypo-intense sphere) is readily observed in 0.5 hour averaged images for both genotypes, and the halo of hyperintensity around the injection site appears similar in averaged images from both genotypes. In the averaged 6 hours post injection images, the intensity qualitatively increases in the basal forebrain of the wild-type littermates but is not obvious in this area of the KLC-KO mice at this time-point, suggesting less Mn2+ has arrived in the MSN of the KLC-KO at this time-point. By 25 hours the signal has reached the MSN in both genotypes.

Figure 3. Aligned and averaged MR images across time-points within genotype.

Shown are axial slices from averaged images for the pre-injection atlas, and for each time-point within genotype. Note that anatomical features are preserved in these T1-weighted images, and the injection site appears distinct, placed in the same location, and similar in size in both genotypes (red arrow). Also note that increased intensity in the medial septal nuclei (MSN) (green arrows) is brighter in wild-type than in KLC-KO at 6 hours post injection.

For further analysis of differences in transport between time-points within each genotype (WT and KLC-KO) we first applied statistical parametric mapping using between time-point pair-wise Student’s t-tests (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) (Penny et al., 2006) (Figure 4). This unbiased comprehensive approach detects all voxels that display statistically significant intensity differences between datasets. At 6 hours after injection we found that, as for visual inspection of the averaged images shown in Figure 3, the statistical map of the wild-type littermates detected statistically significant increased intensity along the expected transport pathway from hippocampal injection site into the basal forebrain (Figure 4A), while fewer statistically significant voxels are detected at the same p-value in the KLC-KO (Figure 4B). At 25 hours, the KLC-KO appears to catch up to the location of the wild-type, with more voxels displaying statistically significant intensity changes progressing anteriorly to the basal forebrain.

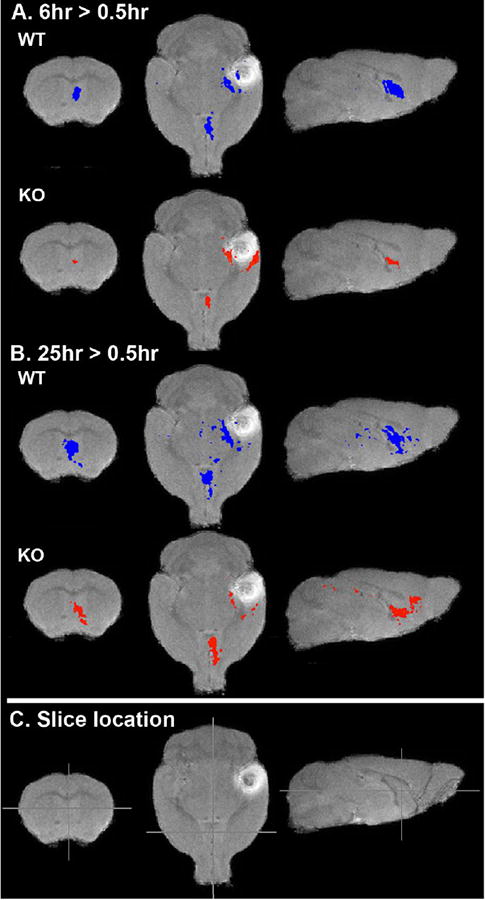

Figure 4.

Within genotype comparisons of transport from the injection site to the basal forebrain in KLC-KO and their wild-type littermates at 6 hour and 25 hour greater than 0.5 hour post-injection. Shown are slices from 3D-voxel-wise statistical parametric maps of paired T-tests (T-maps) comparing voxels with significant intensity increases between time-points for each genotype as indicated. Increases at 6 hours compared to 0.5 hour post-injection (6hr > 0.5hr), and for 25 hours greater that 0.5 hour (25hr >0.5hr) are overlaid on a grayscale image of the minimal deformation atlas for WT at 0.5 hour post-injection. A. The pattern of intensity increases at 6 hours compared with 0.5 hour for each genotype (blue, wild-type littermates; red KLC-KO) p=0.0001 (uncorr.). B. Voxels with increased intensity at 25 hours greater than 0.5 hour post-injection. p=0.0001 (uncorr.) (25hr > 0.5hr). C. Cross-hairs indicate the positions of slices shown in A and B. Note that at this p value, the forebrain appears to have more signal in wild-type than KLC-KO and that signal in the KLC-KO appears to have progressed further anteriorly at 25 hours post injection.

Region of interest analysis confirms differences in transport in KLC-KO compared to wild type

For quantitative analysis of differences between genotypes we performed a region of interest analysis (Figure 5). While the T-maps shown in Figure 4 identify the anatomical locations of intensity changes that reach statistical significance within each group, intensity values measured by ROI identify the degree of change in one location and permit quantitative comparison between genotypes. Measurements of intensities were performed in the medial septal nucleus (MSN) (Figure 5A), where differences were visually apparent in the averaged images and also detected in the SPM within-group between time-point t-tests.

Box plots show wide variation within each genotype (Figure 5B), with KLC-KO mice displaying greater variability than their wild-type littermates at every time-point. Both WT and KO had significantly increased accumulation of Mn2+, as detected by intensity values, at 6 hours compared to 0.5 hours (p = 0.006 and p = 0.04 respectively), albeit with less significance in the KLC-KO. The average intensity increase in the KO from 0.5 hour to 6 hours was only slightly less than WT with such large variation between individuals that this difference is not significant statistically (WT increase: 0.16 ± 0.14, versus KO increase: 0.12 ± 0.12). A 25% reduction in accumulation would compare well with our previous results in the optic nerve, where we found a similar delay in transport along an oriented, mono-directional axon bundle(Bearer et al., 2007a), and could not be confirmed here. At 25 hours, accumulation of Mn2+ in the MSN dropped off in the KO to the point where it was no longer significantly different from 0.5 hours post-injection (p = 0.30). This drop-off was not as drastic in the WT, which retained statistically significance increase compared to the 0.5 hr time-point (p = 0.04).

The change in intensity over time varied widely between individual mice (Figure D and E). When background-corrected intensity values were analyzed by a mixed model ANOVA with repeated measures, confirmed by a post-hoc Tukey’s test, the difference between genotypes was highly significant (p=0.0001) possibly due to high variability at 0.5 hours, particularly in the KLC-KO images. To eliminate variation at the 0.5 time-point and make graphs shown in Fig 5 C-E, we equalized the data by setting the 0.5 hour value to 1 and adjusting the 6 hour and 25 hour values accordingly (see Materials and Methods). When the equalized data as graphed were subjected to mixed model ANOVA analysis, no statistical significance was found (p=0.55).

Neither differences in injection site nor mouse age correlated with greater transport in either group. No neurofilament accumulation or p-tau was found in either group by histologic examination, although both of these were reported in KLC-KO mice, albeit at an older age (18 mo) than the mice studied here (Falzone et al., 2010; Falzone et al., 2009).

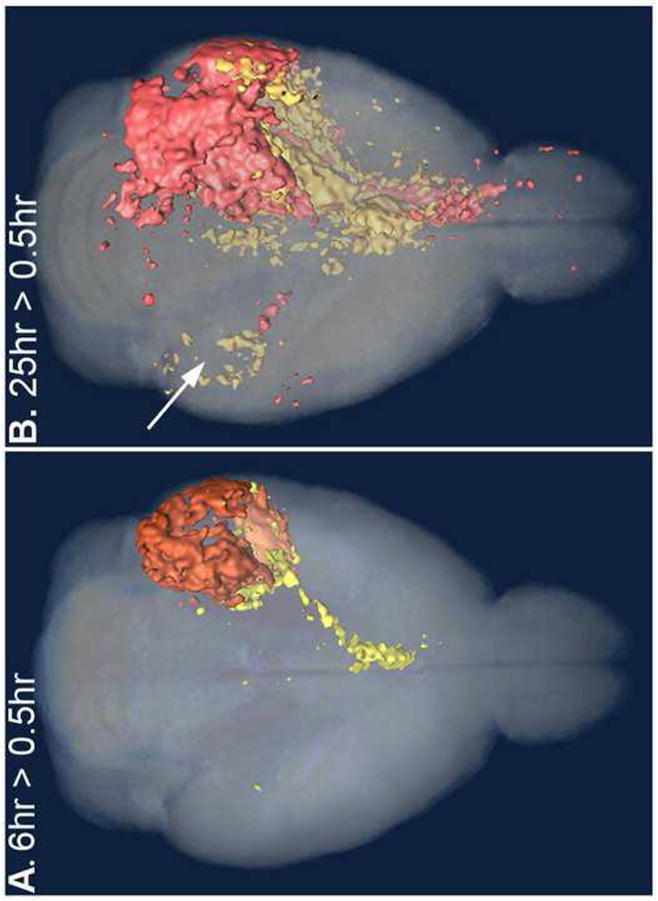

Overlays of T-Maps for visual comparisons of anatomy show differences in sites of accumulation between genotypes

The anatomical distribution of voxels with significantly increased signal in each genotype can be compared when the T-maps are displayed on the same 3D image. Three-dimensional renderings of SPM maps for each genotypes overlaid together onto the same grayscale image allows a comparison of time-dependent anatomical distribution of statistically significant intensity patterns for each genotype in terms of spread and accumulation of Mn2+ throughout the projections of CA3 to the forebrain (Figure 6, see Supplemental Videos 1 and S2 to view the rendering in three dimensions). In wild-type mice statistically significant voxels are found in the MSN at 6 hours after injection (Figure 6A). Similar to our previous findings (Gallagher et al., 2012), wild-type mice also displayed intensity increases in the contralateral hippocampus at 25 hours post-injection (Figure 6B). In contrast, in KLC-KO statistically significant voxels at this T-value in the MSN were fewer at 6 hours, and not evident in the contralateral hippocampus of the KLC-KO even at 25 hours.

Figure 6.

Anatomical comparison of statistical parametric maps from wild-type and knock-out at each time-point superimposed in 3D renderings. These are axial projections of 3D images, with all significant voxels within the full thickness of the brain displayed. Two different T-maps between time-points within each genotype are superimposed on the same 3D grayscale image to enable comparison of the anatomical position of the Mn2+ signal. T-Map of WT (yellow) and KLC-KO (orange). Color intensities are affected by their depth and overlap in the original 3D image used for these projections. See Supplemental Video S1 and S2 to view these images in 3D. A. At 6 hours greater than 0.5 hour (6hr > 0.5hr) after injection, the intensity from the Mn2+ in WT (yellow) has reached the basal forebrain while the KLC-KO (red) remains primarily at the injection site. B. By 25 hours after injection (25hr > 0.5hr), intensity in the KLC-KO occupies the forebrain also, while in WT the Mn2+ signal is also detected in the contralateral hippocampus (B, white arrow). Only sparse signal is detected in the fornix in this projection of the KLC-KO mice (orange), although signal can be seen in the video. Decreased volume in the fiber tract is likely due to its diminished size (see Figures 8 and 9). All four T-Maps at p < 0.005 (uncorr).

Transport is detected in fiber tracts within the brain by MEMRI

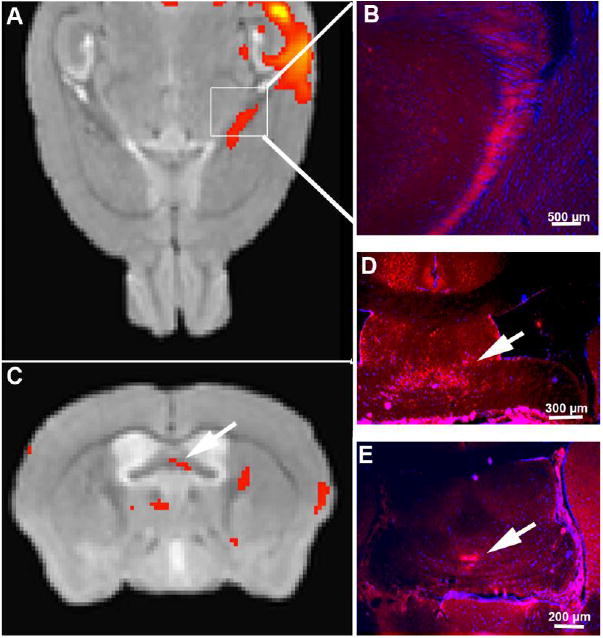

In addition to detecting Mn2+ accumulation in the MSN, we also detected Mn2+-induced intensity changes along the fiber tracts that connect CA3 to the forebrain in both datasets (Figure 7). We compared the anatomy of the F-Map for effect of condition in a flexible factorial analysis of both genotypes and saw statistically significant signal along the fimbria and fornix that compared anatomically with position of the rhodamine dextran co-injected into CA3 in histologic sections. Thus MEMRI tract tracing in the brain could detect not only accumulation at expected distal sites, but actual progress—i.e. transport—along large fiber tracts. To measure the rate of such transport, more frequent image capture than that performed here would be required.

Figure 7. MEMRI detects transport within the fimbria and fornix in the fiber tracts from hippocampus to forebrain.

A and C. Statistical map of the effect of condition (time) in an ANOVA across all 30 post-injection images for both genotypes (p<0.05, FDR corr) overlaid onto a gray-scale template image. Signal (red) appears along the fimbria emanating from the hippocampal injection site and not on the contralateral side. A. Axial slice in the MR corresponding to the anatomical position of the hippocampal fimbria (boxed area). Note the red signal from the SPM F-Map highlighting the injection site and emanating from the hippocampus along the fimbria. B, D and E show fluorescence microscopy of histologic sections from mice injected with RDA in similar anatomic locations as the Mn2+, CA3 of the hippocampus. B. Fluorescence microscopy of a coronal histologic section of the corresponding area shows RDA (red fluorescence), the traditional histologic tract-tracer in the hippocampal fimbria. C. In a coronal slice of the same datasets shown in A, statistically significant signal (red) is identified by voxel-wise ANOVA F-map in the fornix (arrow), which correlates anatomically with RDA signal detected by fluorescence microscopy (arrows in D and E), and with the anatomy of CA3 projections.

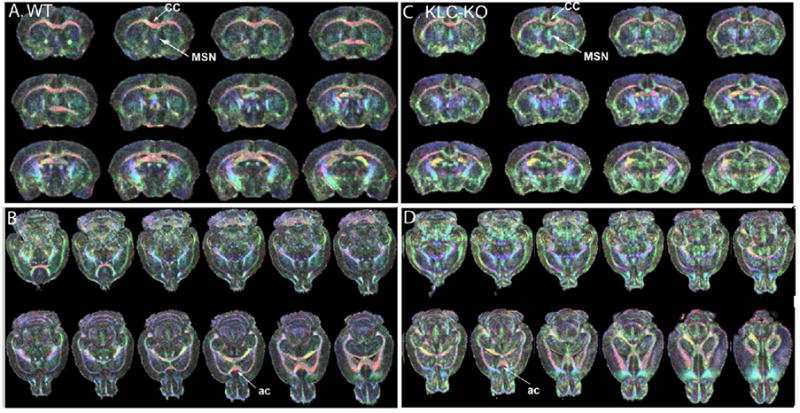

Anatomical effects of KLC-KO by diffusion tensor imaging and histology

To investigate the anatomy of the KLC-KO mice compared to wild-type, we performed diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) on two selected individuals, one from each genotype, and compared the orientations of anisotropy by color-coded computational image rendering (Aggarwal et al., 2010) (Figure 8, and Supplemental Videos 3 and 4). To avoid the introduction of non-linear alignment effects on volumes (van Eede et al., 2013), we limited alignments to rigid body rotations. Results of these DTI alignments demonstrated that the KLC-KO mouse brains were smaller than their wild-type littermates ( Supplemental Figure S1). Comparison of volumes of all KLC-KO T1-weighted MR brain images with wild-type found a 23.2% decrease in size (with KLC-KO/WT size = 0.77 ± 0.03, p = 0.00002).

Figure 8. Anatomy of age-matched KLC-KO and its littermate by diffusion tensor imaging (DTI).

Two of the most aged mice, one from each genotype, were selected for further investigation by DTI. Shown are DT images color-coded for directionality of FA vectors. Eigenvectors were color-coded with red, left-right; green, anterior-posterior; and blue, dorsal-ventral. When the eigenvector is exactly aligned with the coordinate, the color is bright and pure; when at an angle to the coordinate system, the color is mixed proportionally to the directions. 3D stacks of color-coded DTI images from a single WT and its littermate KLC-KO at 13 mo of age are shown, with coronal (A) and axial (B) slices from the WT, and analogous slices from the KLC-KO (C and D respectively). Because of slightly different sizes, the slices do not always pass through the same anatomical structures in the 3D image. Of note is more blended pastel colors in the KLC-KO, suggesting less linearity within the tracts. Also of note is that overall anatomy is not altered significantly in the knock-out compared to its own age-matched littermate. CC: Corpus callosum; AC: Anterior commissure; MSN, medial septal nucleus. Slices are tilted because of the orientation in the 3D dataset. See Supplemental videos S3 and S4 for animation of slices through the two DTI color-coded datasets. Also see Supplemental Figure S1 for size comparison of these two mice, and Figure S2 for higher magnification of the MSN.

Anisotropy was color-coded for the 3 coordinates, with red being left-right, green anterior-posterior, and blue dorsal-ventral. Color-coded DTI images of the KLC-KO revealed thinner corpus callosum, a major fiber bundle. In addition, the KLC-KO had less distinct fiber tracts throughout the brain, as detected by blending of the colors to pastels and concomitant decrease in primary colors in the color-coded DTI images. Despite these minor size differences, the KLC-KO had grossly normal anatomy, with no missing structures and all major brain regions in their normal relative positions, supporting the conclusion that large-scale structural abnormalities did not produce the observed delay in transport dynamics. However, at higher magnification some differences in the orientation of fiber tracts in the MSN was detected, with the KLC-KO having more signal in the blue, dorsal-ventral, direction ( Supplemental Figure S2). This altered orientation may account for the slightly different anatomy of the T-maps in the different genotypes, best appreciated in Figure 6.

The same mice imaged for DTI were also imaged post-mortem by microscopy. As in the DTI, histologic analysis found that the KLC-KO brains were smaller than wild-type littermates of the same age, as was originally described for the whole animal (Rahman et al., 1999) (Figure 9, A and B). Measurements of the brain width in coronal sections demonstrated an average 17 ± 5% decrease in width (range 10.5-23.3%, p = 0.02). As previously described (Falzone et al., 2009) the corpus callosum was proportionately smaller, 23.8% decreased in KLC-KO compared to wild-type (p= 0.003) (Figure 9, C and D). Hence the decrease in width of the corpus callosum was analogous to the overall decrease in volume of the brain. In a background of Alzheimer’s models expressing mutant amyloid precursor protein (Stokin et al., 2008; Stokin et al., 2005), or mutant tau protein (Falzone et al., 2010), KLC1 reduction enhances neuropathology with increased phospho-tau and amyloid, and varicosities in cholinergic axons (Falzone et al., 2010; Stokin et al., 2005). We stained serial sections across the whole brain of all animals in parallel in this study for plaque with a standard silver stain and for phosphorylated pathogenic tau with the AT8 antibody. Neither of these pathologic features was found in any of the brains, even of the oldest of our KLC-KO mice in a wild type background absent other mutations or transgenes.

Figure 9. Histologic analysis shows decreased size.

A and B. Examples of coronal sections through the MSN stained for Thionine/Nissl of WT (A) and KLC-KO (B). Other than decreased size (17±5% decrease in left-right width of coronal sections, p = 0.02), the KLC-KO appears anatomically normal. C and D. A comparison of the corpus callosum shows diminished width (on average 23% smaller in KLC-KO, p = 0.003).

Discussion

Here we show that conventional kinesin, otherwise known as kinesin-1, plays a role in axonal transport dynamics not only in the periphery, as has previously been described, but also within the central nervous system, as the cognitive deficits in humans with KIF5A and B mutations predict (Liu et al., 2014; Su et al., 2013). Our statistical parametric maps within group show differences in Mn2+ distribution in the KLC-KO, with apparently slower extension of the signal from the injection site into the forebrain, followed by further extension at later time-points. After reaching a peak at 6 hours the intensity decreases in the MSN of both genotypes at 25 hours. Statistical analysis of ROI measurements showed that differences in intensity in the MSN over time within each genotype were significant, but differences between genotypes were not. These two different analyses, statistical maps within genotype and ROI analysis between genotype, appear to conflict. However, SPM shows delayed progression of anatomical distribution of significant voxels, ROI shows differences in intensity values between genotypes. Anatomical differences such as smaller brain size could not account for the differences in SPM maps. Taken together, these results suggest that transport, as witnessed by MEMRI, is somewhat decreased in the CNS in the absence of the KLC1 subunit of the kinesin-1 motor, but is not as drastically affected by this subunit knock-out as might be expected, given the abundance of kinesin-1 in brain.

While kinesin-1 driven transport has been imaged in the optic nerve (Bearer et al., 2007a), in peripheral nerves, and in cultured cells, both neuronal and other cell types; this study is the first to image transport dynamics within the living intact mammalian brain in a KLC1 knockout mouse. Our results demonstrate that intact kinesin-1 together with the KLC1 light chain is not as necessary for transport within the living brain as in the optic nerve.

In mice, defective transport in the brain from a knock-out of the KLC1 gene was expected, since kinesin-1 is the most abundant of the kinesin motors in brain, and delays in proteasome transport are seen in hippocampal neurons in culture (Otero et al., 2014). In addition, enhanced pathological phenotypes occur in double transgenic mice heterozygous for KLC1 deletions and carrying familial Alzheimer’s disease-associated mutations in amyloid precursor protein (Stokin et al., 2008; Stokin et al., 2005). The impairment we observed is less than these reports would suggest.

Other kinesin light chains could be responsible for the residual transport in the brain observed in the KLC1-KO mice. In addition to KLC1, at least two and perhaps three kinesin light chains are also expressed in brain: KLC2 (Rahman et al., 1998), KLC3 (Chung et al., 2007) and possibly KLC4, sequenced from a brain cDNA library and predicted to interact with all three kinesin heavy chain isoforms (Ota et al., 2004). Thus viability and residual transport in the KLC-KO mice may be mediated by other light chains such that a knock-out of one light chain does not produce complete loss-of-function of the kinesin-1 holoenzyme (Rahman et al., 1999). We may have been able to detect an even greater impact on transport rates had the mice withstood imaging at earlier time-points after injection. Our study cannot rule-out an even more significant contribution by kinesin-1 on CNS axonal transport, since the other light chains may rescue the lack of KLC1, and since the phenotype of a knock-out of even one of the heavy chain genes, KIF5A, is embryonic lethal (Tanaka et al., 1998).

Continued but lower Mn2+ transport could also be accomplished in the KLC-KO by redundant or compensatory mechanisms due to other motors. Mn2+ may enter several different vesicular compartments, and thus be transported by more than one microtubule-based motor. In the giant axon of the squid, at least three other kinesins are expressed (DeGiorgis et al., 2011). Deletion of one of these, KIF1A, a gene encoding the heavy chain of kinesin-3, in mice results in perinatal death, with severe developmental defects in both motor and sensory systems and abnormal aggregation of synaptic vesicle precursors in neuronal cell bodies (Yonekawa et al., 1998). Other axonal kinesins include kinesin-2 (Noda et al., 1995). Thus some of the compartments occupied by Mn2+ are likely to be transported normally by other kinesin-family motors in the absence of KLC1. How these many different motors interact with various cargo is an area of vigorous investigation by cell biologists.

Transport in the KLC-KO mouse may be compromised by secondary effects of the deletion on other transported macromolecules. The variation in accumulation in the MSN between individuals occurred in both wild-type and the knock-outs and was not correlated with age or injection site, and thus is probably a normal fluctuation in transport within this circuit and not a consequence of secondary effects in the mutant. Neurofilaments are transported by kinesin-1 (Uchida et al., 2009), and form abnormal aggregates in aging KLC-KO (15-18 month old) mice when carrying a human tau transgene (Falzone et al., 2009; Li et al., 2012; Xia et al., 2003). Such aggregates could produce obstructions in the axonal highways. Our histology did not feature this pathology, nor did we detect phosphorylated tau in the younger mice (8-13 month old) studied here. It is also conceivable that other cellular processes compromised by KLC1 deletion underlie the delayed Mn2+ transport observed here. Decreased transport of synaptic vesicles could impair trans-synaptic signaling, upon which Mn2+ depends to cross synapses (Bearer et al., 2007a). For example, delayed transport of ion channels could delay uptake (Barry et al., 2014). However, the relatively normal behavior of these mice argues against a large deficit in ion channels required for neuronal function, although a minor contribution from decreased release or uptake could enhance the transport deficit reported here.

Consistent with our results suggesting a small but significant role for kinesin-1 in axonal transport are reports that mutations in human KIF5A, one of three genes in humans encoding kinesin-1 heavy chain, cause hereditary spastic paraplegia with early to mid-life onset (Hamdan et al., 2011; Klebe et al., 2012; Musumeci et al., 2011; Schule et al., 2008; Yonekawa et al., 1998). Very long peripheral nerves are even more vulnerable than the shorter axons in the CNS to transport defects. In the periphery, symptomatology of transport defects is more apparent than in more subtle CNS functions, such as cognition, memory and emotion. Genetic mutations in proteins that interact with kinesin-1 activity produce hereditary neurological and cognitive disorders symptomatically. For example, mutations in HSPB1 increase cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of neurofilaments, reducing their ability to bind kinesin-1, altering their intraneuronal structure, and producing a Charcot-Marie Tooth neuropathy (Holmgren et al., 2013); and beta-tubulin mutations that cause significant human developmental malformations, such as polymicrogyria, congenital fibrosis of extra-ocular muscle type 3 (CFEOM3) and malformation of cortical development (MCD) (Tischfield et al., 2011), also reduce kinesin-1 driven axonal transport (Niwa et al., 2013) and probably other microtubule-based motors as well. Among these mutations in the Class III tubulin gene, TUBB3, induce very severe neurological symptoms, including peripheral neuropathy and loss of axons in many kinds of brain neurons through their effect on microtubule-kinesin interactions (Tischfield et al., 2010). The alteration of fiber orientation in the KLC-KO detected by DTI in the MSN could have resulted in different anatomic position and would be expected to increase rather than decrease the rate of Mn2+ accumulation. However, although anatomic analysis by DTI and by histology did not reveal major structural differences, the possibility remains that such differences below the resolution of the techniques employed here may contribute to the altered distribution of Mn2+ intensity changes in the statistical parametric T-maps of KLC-KO.

The surprising extension of signal deep into the forebrain at 25 hours in the KLC-KO mice, exceeding that of the wild-type, suggests the existence of confounding effects in these experiments, such as secondary effects of the mutation on trans-synaptic Mn2+ transfer, variations in Mn2+ uptake, or even abnormal axonal connectivity. Since the signal in each 90-100µm3 voxel represents hundreds, or even thousands, of axons, we cannot rule-out small alterations in axonal pathways, even with histologic comparisons at much higher resolution than the MR studies allow. Visual comparison of DTI images for two mice, one for each genotype, suggested a difference in orientation of axons anterior/dorsal to the anterior commissure, correlating with the location of the altered MEMRI signal. This alteration explains the differences in location of the signal better than it might explain a delayed arrival in KLC-KO. We also considered alterations in numbers or axonal structure of cholinergic neurons in the MSN, which are affected in heterozygous KLC1 knockout mice at 18 months of age in a background of other Alzheimer’s-related transgenes (Stokin et al., 2008), and found neither decreased numbers nor axonal varicosities in the homozygous KLC-KO mice studied here. Decreased width of the corpus callosum (23% narrower than wild-type on average) was found in these homozygous KLC-KO mice, although this decrease was proportional to the overall decrease in brain size – KLC-KO brains were on average 23% smaller as determined by volume-based morphometry of skull-stripped MR brain images. While accumulation in the MSN via axonal transport would be affected by a diminished number of axons in the circuitry, this could be balanced by a similar decrease in the distance to be traveled.

A delay in arrival in the MSN in KLC-KO would be consistent with a constitutive transport process, like a conveyor belt, where vesicular movements are at steady state and accumulation is saturable. In this hypothetical scenario, accumulation would reach a maximum more slowly in KLC-KO due to fewer vesicles moving per unit time. Decreased transport is detected in our studies because the bolus of tracer is introduced in a specific location at a single time-point and we imaged at early enough time-points, before accumulation has reached maximal, to detect the small difference in arrival. At these early time-points, when the tracer, Mn2+, is first being picked up by the transport system, differences between KLC-KO and WT are revealed. As time goes on, accumulation reaches saturation in both WT and KLC-KO, and then loss of Mn2+ from the distal site exceeds accumulation and becomes detectable, as shown in the decreasing intensity between 6 hours and 25 hours in the ROI analyses. Should synaptic vesicle usage increase, as occurs during neuronal excitation, our results predict that those animals with decreased transport may experience functional deficits in central nervous system processing due to slower replenishment of synaptic vesicles, just as occurs in hereditary peripheral neuropathies. Such CNS processing defects would also be predicted in humans with kinesin-1 mutations.

Our results furthermore demonstrate the usefulness of time-lapse MEMRI as a tool for pre-clinical studies of transport dynamics and their contribution to progression of central nervous system pathology. Previously we reported that the KLC1 knockout reduced the rate of Mn2+ transport in the visual system by approximately one third (Bearer et al., 2007a). Here we show that this defect is minimized in brain. An APP knock-out produces Mn2+ transport defects in the CNS (Gallagher et al., 2012), demonstrating that such deficits can be detected by MEMRI. Thus knockout of KLC1 has less effect than APP knockout on transport of Mn2+, suggesting that other kinesin-1 lights chains or other motors may contribute to cargo transport in the CNS. Thus detection of Mn2+ transport in the CNS makes MEMRI an exciting tool for studying the role of transport in Alzheimer’s research.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Video S1: Three dimensional projections of two within-genotype T-maps comparing 6 hours greater than 30 min (yellow, KLC-KO, and red, WT) onto the Pre-injection Atlas, as shown in Figure 6A, and rendered in three dimensions in video format. By projecting both maps onto the same gray-scale image, the anatomy of the time-dependent intensity changes for each genotype can be directly compared. This dual projection is for anatomy and should not be mistaken for a statistical comparison of transport between the genotypes, which is better demonstrated by the ROI analysis shown in Figure 5.

Supplemental Video S2: Three dimensional projections of two T-maps comparing 25 hour greater than 30 min (25 hr > 30 min) for each genotype (yellow, KLC-KO, and red, WT) onto the Pre-injection Atlas (grayscale), as shown in Figure 6B. This projection is to enable comparison of the anatomical position of the signal and does not represent between-genotype statistics.

Supplemental Video S3: Coronal sections in a video stack of the rendered color-coded DTI for the wild-type mouse shown in Figure 8A and B, and in Supplemental Figure S2 A.

Supplemental Video S4: Coronal sections in a video stack of the rendered color-coded DTI for the KLC-KO mouse shown in Figure 8C and D, and in Supplemental Figure S2 B.

Highlights.

This is the first study to test the role of kinesin-1, the most abundant microtubulebased motor in brain, in axonal transport within the central nervous system.

In cultured cells, the optic nerve and the peripheral nervous system, deletion of kinesin-light-chain 1 (KLC1), one of the subunits of kinesin-1, impairs transport of a subset of vesicles. Here we show that in brain KLC1 deletion leads to a smaller than expected reduction of Mn2+ transport along the fimbria and fornix from CA3 to the septal nuclei.

Taken together with our previous report, that transport of Mn2+ in amyloidprecursor protein (APP) knock-out mice is depressed in this same circuit (Gallagher et al, 2012), these new results show that intracerebral Mn2+ transport detected by MRI provides a method to measure axonal transport in the living brain.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ivo Dinov and Joshi Anand in the Laboratory of NeuroImaging directed by Art Toga for assistance with the LONI Pipeline processing environment; Kevin Reagan, Paulette Ferland, Abdul Faheem Mohed and Kathleen Kilpatrick for technical assistance; and Brett Manifold-Wheeler for helpful discussions. We thank Russell E. Jacobs (California Institute of Technology and the Beckman Institute Small Animal Imaging Facility) for assistance with data collection, analysis and useful comments, and to Vince Calhoun, at UNM and Mind Research Network, for help with SPM analysis. We thank Louie Kerr and the Central Microscopy Facility at the Marine Biological Laboratory for access to their equipment, and to the MBL library where most of this MS was written. We are particularly grateful to Li Luo, our UNM CTSC statistician, for help with statistical analysis and its interpretation. This work is supported by NIH R01 MH096093, RO1 NS062184, P5O GM08273, UNM CTSC grant UL1 TR000041 and the Harvey Family Endowment.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aggarwal M, Mori S, Shimogori T, Blackshaw S, Zhang J. Three-dimensional diffusion tensor microimaging for anatomical characterization of the mouse brain. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:249–261. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry J, Gu Y, Jukkola P, O'Neill B, Gu H, Mohler PJ, Rajamani KT, Gu C. Ankyrin-G directly binds to kinesin-1 to transport voltage-gated Na+ channels into axons. Dev Cell. 2014;28:117–131. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearer EL, Falzone TL, Zhang X, Biris O, Rasin A, Jacobs RE. Role of neuronal activity and kinesin on tract tracing by manganese-enhanced MRI (MEMRI) Neuroimage. 2007a;37(1):S37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearer EL, Zhang X, Jacobs RE. Live imaging of neuronal connections by magnetic resonance: Robust transport in the hippocampal-septal memory circuit in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Neuroimage. 2007b;37:230–242. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearer EL, Zhang X, Janvelyan D, Boulat B, Jacobs RE. Reward circuitry is perturbed in the absence of the serotonin transporter. Neuroimage. 2009;46:1091–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell PD, Shen K, Sapio MR, Glenn TD, Talbot WS, Marlow FL. Unique function of Kinesin Kif5A in localization of mitochondria in axons. J Neurosci. 2014;34:14717–14732. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2770-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, Zhang Y, Van Der Hoorn F, Hawkes R. The anatomy of the cerebellar nuclei in the normal and scrambler mouse as revealed by the expression of the microtubule-associated protein kinesin light chain 3. Brain Res. 2007;1140:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross DJ, Flexman JA, Anzai Y, Maravilla KR, Minoshima S. Age-related decrease in axonal transport measured by MR imaging in vivo. Neuroimage. 2008;39:915–926. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGiorgis JA, Cavaliere KR, Burbach JP. Identification of molecular motors in the Woods Hole squid, Loligo pealei: an expressed sequence tag approach. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2011;68:566–577. doi: 10.1002/cm.20531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delora A, Gonzales A, Medina CS, Mitchell A, Mohed AF, Jacobs RE, Bearer EL. A simple rapid process for semi-automated brain extraction from magnetic resonance images of the whole mouse head. J Neurosci Methods. 2015;257:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djagaeva I, Rose DJ, Lim A, Venter CE, Brendza KM, Moua P, Saxton WM. Three routes to suppression of the neurodegenerative phenotypes caused by kinesin heavy chain mutations. Genetics. 2012;192:173–183. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.140798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund A, Andersson M, Josephson C, Johannesson M, Knutsson H. Does parametric fMRI analysis with SPM yield valid results? An empirical study of 1484 rest datasets. Neuroimage. 2012;61:565–578. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund A, Nichols T, Knuttson H. Can Paremtric statistical methods be trusted for FMRI group based studies. 2015 arXv:1511.01863v1 [stat.AP] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenko O, Evrard HC, Neves RM, Beyerlein M, Murayama Y, Logothetis NK. Tracing of noradrenergic projections using manganese-enhanced MRI. Neuroimage. 2012;59:3252–3265. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falzone TL, Gunawardena S, McCleary D, Reis GF, Goldstein LS. Kinesin-1 transport reductions enhance human tau hyperphosphorylation, aggregation and neurodegeneration in animal models of tauopathies. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4399–4408. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falzone TL, Stokin GB, Lillo C, Rodrigues EM, Westerman EL, Williams DS, Goldstein LS. Axonal stress kinase activation and tau misbehavior induced by kinesin-1 transport defects. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5758–5767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0780-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley JW. Manganese uptake and release by cultured human hepato-carcinoma (Hep-G2) cells. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1998;64:101–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher JJ, Zhang X, Hall FS, Uhl GR, Bearer EL, Jacobs RE. Altered reward circuitry in the norepinephrine transporter knockout mouse. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher JJ, Zhang XW, Ziomeck GJ, Jacobs RE, Bearer EL. Deficits in axonal transport in hippocampal-based circuitry and the visual pathway inAPPknock-out animals witnessed by manganese enhanced MRI. Neuroimage. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.132. in press (see Appendix in this grant proposal) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudkov AV, Kazarov AR, Thimmapaya R, Axenovich SA, Mazo IA, Roninson IB. Cloning mammalian genes by expression selection of genetic suppressor elements: association of kinesin with drug resistance and cell immortalization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3744–3748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan FF, Gauthier J, Araki Y, Lin DT, Yoshizawa Y, Higashi K, Park AR, Spiegelman D, Dobrzeniecka S, Piton A, Tomitori H, Daoud H, Massicotte C, Henrion E, Diallo O, Shekarabi M, Marineau C, Shevell M, Maranda B, Mitchell G, Nadeau A, D'Anjou G, Vanasse M, Srour M, Lafreniere RG, Drapeau P, Lacaille JC, Kim E, Lee JR, Igarashi K, Huganir RL, Rouleau GA, Michaud JL. Excess of de novo deleterious mutations in genes associated with glutamatergic systems in nonsyndromic intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan KM, Basser PJ, Parker DL, Alexander AL. Analytical computation of the eigenvalues and eigenvectors in DT-MRI. J Magn Reson. 2001;152:41–47. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes K, Buist R, Vincent TJ, Thiessen JD, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Wang J, Summers AR, Kong J, Li XM, Martin M. Comparison of manual and semi-automated segmentation methods to evaluate hippocampus volume in APP and PS1 transgenic mice obtained via in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci Methods. 2014;221:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig J, Nauerth A, Friedburg H. Rare imaging - a fast imaging method for clinical MR. Magn Reson Med. 1986;3:823–833. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910030602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa N, Niwa S, Tanaka Y. Molecular motors in neurons: transport mechanisms and roles in brain function, development, and disease. Neuron. 2010;68:610–638. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa N, Noda Y, Tanaka Y, Niwa S. Kinesin superfamily motor proteins and intracellular transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:682–696. doi: 10.1038/nrm2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren A, Bouhy D, De Winter V, Asselbergh B, Timmermans JP, Irobi J, Timmerman V. Charcot-Marie-Tooth causing HSPB1 mutations increase Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of neurofilaments. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:93–108. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1133-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A, Almenar-Queralt A, LeBlanc JF, Roberts EA, Goldstein LS. Kinesin-mediated axonal transport of a membrane compartment containing beta-secretase and presenilin-1 requires APP. Nature. 2001;414:643–648. doi: 10.1038/414643a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A, Stokin GB, Yang Z, Xia CH, Goldstein LS. Axonal transport of amyloid precursor protein is mediated by direct binding to the kinesin light chain subunit of kinesin-I. Neuron. 2000;28:449–459. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebe S, Lossos A, Azzedine H, Mundwiller E, Sheffer R, Gaussen M, Marelli C, Nawara M, Carpentier W, Meyer V, Rastetter A, Martin E, Bouteiller D, Orlando L, Gyapay G, El-Hachimi KH, Zimmerman B, Gamliel M, Misk A, Lerer I, Brice A, Durr A, Stevanin G. KIF1A missense mutations in SPG30, an autosomal recessive spastic paraplegia: distinct phenotypes according to the nature of the mutations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:645–649. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacevic N, Henderson JT, Chan E, Lifshitz N, Bishop J, Evans AC, Henkelman RM, Chen XJ. A Three-dimensional MRI Atlas of the Mouse Brain with Estimates of the Average and Variability. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:639–645. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Jung P, Brown A. Axonal transport of neurofilaments: a single population of intermittently moving polymers. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:746–758. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4926-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey JD, Grob SR, Scadeng M, Duong-Polk K, Weinreb RN. Ocular integrity following manganese labeling of the visual system for MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;31:865–874. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippincott-Schwartz J, Cole NB, Marotta A, Conrad PA, Bloom GS. Kinesin is the motor for microtubule-mediated Golgi-to-ER membrane traffic. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:293–306. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.3.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YT, Laura M, Hersheson J, Horga A, Jaunmuktane Z, Brandner S, Pittman A, Hughes D, Polke JM, Sweeney MG, Proukakis C, Janssen JC, Auer-Grumbach M, Zuchner S, Shields KG, Reilly MM, Houlden H. Extended phenotypic spectrum of KIF5A mutations: From spastic paraplegia to axonal neuropathy. Neurology. 2014;83:612–619. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie-Graham A, Boline J, W TA. NeuorInformatics. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2007. Brain Atlases and Neuroanatomic Imaging; pp. 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majid T, Ali YO, Venkitaramani DV, Jang MK, Lu HC, Pautler RG. In vivo axonal transport deficits in a mouse model of fronto-temporal dementia. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;4:711–717. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaad CA, Pautler RG. Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI) Methods Mol Biol. 2011;711:145–174. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-992-5_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiello J, Basser PJ, Le Bihan D. The b matrix in diffusion tensor echo-planar imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37:292–300. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt JE, Jacob R, Hallam TJ. Use of manganese to discriminate between calcium influx and mobilization from internal stores in stimulated human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1522–1527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modat M. NiftyReg (Aladin and F3D) [Google Scholar]

- Musumeci O, Bassi MT, Mazzeo A, Grandis M, Crimella C, Martinuzzi A, Toscano A. A novel mutation in KIF5A gene causing hereditary spastic paraplegia with axonal neuropathy. Neurol Sci. 2011;32:665–668. doi: 10.1007/s10072-010-0445-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Tanaka Y, Matsuoka E, Kondo S, Okada Y, Noda Y, Kanai Y, Hirokawa N. Identification and classification of 16 new kinesin superfamily (KIF) proteins in mouse genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9654–9659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niclas J, Navone F, Hom-Booher N, Vale RD. Cloning and localization of a conventional kinesin motor expressed exclusively in neurons. Neuron. 1994;12:1059–1072. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa S, Takahashi H, Hirokawa N. beta-Tubulin mutations that cause severe neuropathies disrupt axonal transport. EMBO J. 2013;32:1352–1364. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda Y, Sato-Yoshitake R, Kondo S, Nangaku M, Hirokawa N. KIF2 is a new microtubule-based anterograde motor that transports membranous organelles distinct from those carried by kinesin heavy chain or KIF3A/B. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:157–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]