Abstract

For single-domain proteins, we examine the completeness of the structures in the current Protein Data Bank (PDB) library for use in full-length model construction of unknown sequences. To address this issue, we employ a comprehensive benchmark set of 1,489 medium-size proteins that cover the PDB at the level of 35% sequence identity and identify templates by structure alignment. With homologous proteins excluded, we can always find similar folds to native with an average rms deviation (RMSD) from native of 2.5 Å with ≈82% alignment coverage. These template structures often contain a significant number of insertions/deletions. The tasser algorithm was applied to build full-length models, where continuous fragments are excised from the top-scoring templates and reassembled under the guide of an optimized force field, which includes consensus restraints taken from the templates and knowledge-based statistical potentials. For almost all targets (except for 2/1,489), the resultant full-length models have an RMSD to native below 6 Å (97% of them below 4 Å). On average, the RMSD of full-length models is 2.25 Å, with aligned regions improved from 2.5 Å to 1.88 Å, comparable with the accuracy of low-resolution experimental structures. Furthermore, starting from state-of-the-art structural alignments, we demonstrate a methodology that can consistently bring template-based alignments closer to native. These results are highly suggestive that the protein-folding problem can in principle be solved based on the current PDB library by developing efficient fold recognition algorithms that can recover such initial alignments.

As of December 30, 2003, >23,000 solved protein structures have been deposited in the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank (PDB) (1). This number keeps increasing, with ≈300 new entries added each month. The size and completeness of the PDB is essential to the success of template-based approaches to protein structure prediction. These methods include comparative modeling (2, 3) and threading (4–7), which are designed to infer an unknown sequence's structure based on solved, similarly folded protein structures in the PDB. Because an accurate theory for the prediction of protein structure on the basis of physical principles does not yet exist, comparative modeling/threading approaches are the only reliable strategy for high-resolution tertiary structure prediction (8–10). On the other hand, the percentage of new folds in these new entries, the topology of which has never been seen in the current PDB library, keeps decreasing (e.g., the percentage of new folds was 27% in 1995 but 5% in 2001). The apparent saturation of new folds immediately raises an important question: At least for single-domain proteins, is the current structure library already complete enough to in principle solve the protein tertiary structure prediction problem at low-to-moderate resolutions?

By means of a variety of structure comparison tools (11–14), this issue has been partially addressed by many authors (15–20). It was demonstrated through systematic protein structure classification (15–17) that protein fold space is highly dense, and all solved PDB structures can be grouped into a very limited number of hierarchical families. Several authors (17–20) found that many proteins from different fold families share common substructures/motifs and the protein fold space tends to be continuous. Especially, Kihara and Skolnick (20) showed that (after excluding homologues) for >90% of single-domain proteins below 200 residues, there exists at least one structure (actually many) in the PDB having an rms deviation (RMSD) root to native below4Åwith ≈79% alignment coverage. This finding suggests that, at least at the level of structure alignments, the current PDB is almost a complete set of single-domain protein structures. However, the alignments identified from structure superposition usually contain numerous gaps. Starting from such alignments, it is still unknown in how many cases one could successfully build full-length models useful for biological annotation (21–23). It could be that such models, while bearing a structural resemblance to the native state, might be sufficiently distorted that they could not be used as starting templates to build physically reasonable structures. Then our prior conclusion about the completeness of the PDB would be of purely academic interest, without practical ramifications. If, however, biologically useful models could be built, then the observation of the completeness of the PDB would have immediate practical value, not the least being that the protein structure prediction problem could in principle be solved on the basis of the current PDB library, if a sufficiently powerful fold recognition algorithm could be developed to recover such alignments (21, 23, 25). It is the desire to explore this issue that provided the impetus of the work described here. Certainly, the requisite resolution required for different aspects of functional analysis (ligand docking, active site identification, etc.) may vary (21). Recent investigations show that the active sites of enzymes can be successfully identified in about one-third of decoy structures of 3- to 4-Å RMSD (24).

Another important issue faced by protein structure modelers is related to the template refinement process. Until recently, protein-modeling procedures usually drive the models farther from native, compared with initial template alignments (8–10, 26). It is a hard challenge to start from the structural (as opposed to threading-based) alignments and improve upon them. To date, there has been no systematic demonstration that this was possible. The exploration of this issue provides the second motivation for this work.

In this work, using a recently developed modeling algorithm, tasser (27), we examine both issues, by building full-length models from the templates identified by a state-of-the-art structure alignment algorithm (20), and by demonstrating that in many cases the initial alignments are improved. To assess the generality of the conclusion, the strategy will be applied to a comprehensive, large-scale PDB test set, with homologous proteins removed from the template library.

Methods

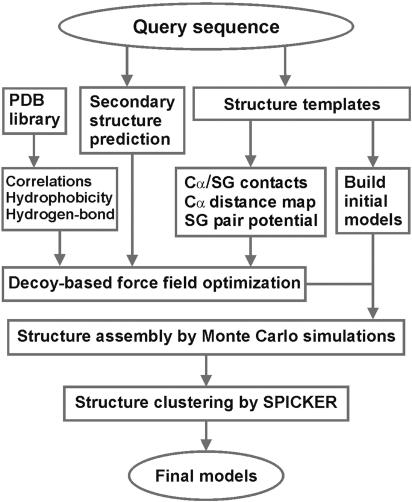

The protein structure modeling procedure used in this work consists of template identification, force field construction, fragment assembly, and model selection. A flowchart is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the tasser structure prediction methodology that consists of template identification (here by structure alignment), force field construction, structure assembly, and model selection.

Template Identification. Templates are identified from the solved structures in the PDB by structurally aligning the native of query proteins to templates by using our Structure Alignment (sal algorithm (20). The alignment is performed by a Needleman–Wunsch dynamic program (28) with the score matrix defined as (29) score(i, j) = 20/(1 + d3ij/5), where dij is the spatial distance between the ith and jth residues after an initial guessed superposition. A number of iterations are performed until the structure alignment converges. Various gap penalties are implemented, and the best alignment is selected on the basis of the Z-score of the relative RMSD of two aligned proteins (30).

Force Field Construction. The force field used in tasser includes four classes of terms: (i) Cα and side-chain group (SG) regularities/correlations from the statistics of the PDB, (ii) propensities for predicted secondary structure from psipred (31), (iii) tertiary consensus contact/distance restraints, and (iv) a protein-specific SG pair potential, both extracted from the identified multiple templates. The construction and implementation of the potentials in i and ii have been described (32, 33). The tertiary restraints in iii are constructed as done by our threading program prospector_3 (6); and the details of the new pair potential in iv are in the Appendix.

Having all of the energy terms, optimization for the combination weight factors was performed based on 100 training proteins (outside the benchmark test set used here), each with 60,000 structure decoys, where we maximize the correlation between the energy and RMSD from native to the decoys (32).

Structure Assembly. Full-length models are constructed by reassembling the continuous fragments excised from the templates under the guide of the optimized force field. These fragments are elemental building blocks with internal conformations kept invariant during modeling. Residues in gapped regions are generated from an ab initio lattice modeling approach (32). These regions also serve as linkage points for the rigid block movements. Conformational space is searched by using parallel hyperbolic Monte Carlo sampling (34), where the tertiary topology varies by continuous translations and rotations of the rigid blocks. The magnitude of the move is scaled by the size of the blocks. Forty to fifty replicas are used in the simulations depending on protein size, and the trajectories in the 14 lowest temperature replicas are submitted to spicker (35) for clustering. The final models are combined from members of the structure clusters, ranked on the basis of cluster structure density.

Results and Discussion

Benchmark of Targets and Templates. For test proteins, we develop a representative benchmark set of all single-domain structures in PDB with 41–200 aa. This target set contains 1,489 nonhomologous proteins having 448, 434, and 550 α-, β-, and αβ-proteins, respectively (the other 57 are Cα-only targets or have irregular secondary structures). The template library consists of 3,575 representative proteins from the PDB with a maximum 35% pairwise sequence identity to each other; all templates are taken from this library.

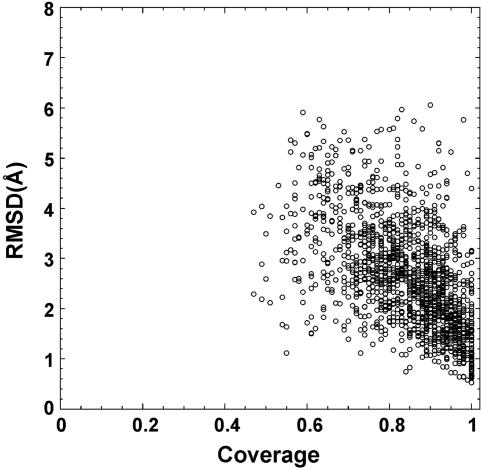

Fig. 2 shows a summary of the resulting templates that have the highest RMSD Z-score obtained from sal (20) for all 1,489 test proteins, where all templates with >25% sequence identity to the target protein are excluded. The majority of targets have >70% coverage and <4-Å RMSD to native, which shows the significant denseness of protein structure space. The average sequence identity between template and target is 13% in the aligned regions.

Fig. 2.

RMSD to native of the templates identified by the structure alignment program sal (20) versus the alignment coverage.

Summary of Folding Results. Table 1 presents a summary of the folding results, where, for each protein, the two templates with the highest RMSD Z-score are used in tasser. A detailed list of templates and final models, as well as the simulation trajectories, can be obtained by contacting J.S.

Table 1.

|

sal

|

tasser

|

modeller

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best* | Align† | Top five‡ | Top one§ | Align† | Top five‡ | Top one§ | |

| RMSD, Å | 2.510 | 1.877 | 2.246 | 2.352 | 2.708 | 3.740 | 4.318 |

| Coverage, % | 82 | 82 | 100 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 100 |

| NRMSD<6¶ | 1,489 | 1,489 | 1,487 | 1,481 | 1,462 | 1,326 | 1,202 |

| NRMSD<5 | 1,472 | 1,489 | 1,481 | 1,464 | 1,395 | 1,195 | 1,060 |

| NRMSD<4 | 1,369 | 1,488 | 1,447 | 1,423 | 1,255 | 984 | 841 |

| NRMSD<3 | 1,064 | 1,422 | 1,259 | 1,206 | 1,008 | 647 | 551 |

| NRMSD<2 | 498 | 922 | 623 | 582 | 520 | 300 | 244 |

| NRMSD<1 | 46 | 83 | 52 | 49 | 37 | 20 | 15 |

The template of the lowest RMSD to native.

The best model in top five by tasser and modeller with the RMSD calculated in the aligned region.

The best model in top five where the RMSD is calculated for the entire chain.

The first model where the RMSD is calculated for the entire chain.

No. of targets with RMSD below the specified threshold (Å).

In Table 1, the second column shows the best templates in the top two with the lowest RMSD to native in the aligned regions. On average, the RMSD to native is 2.51 Å with 82% coverage. The final models show improvement over the initial template alignments. Over the same aligned regions, the average RMSD to native is reduced to 1.88 Å. Many low-resolution templates have been shifted by tasser refinement to structures with an acceptable resolution for biochemical function annotation (24). For example, there are 358 targets shifted from >3-Å to <3-Å RMSD to native, and 424 targets shifted from above to below 2 Å.

For full-length models, almost all targets (except for 1a2kC and 1k5dB) have an RMSD to native below 6 Å for the best of the top five models, with an average rank of 1.7; 97% have an RMSD <4 Å. The average RMSD to native is 2.25 Å, comparable with the accuracy of a low-resolution NMR or x-ray structure (25, 36, 37). For the rank one cluster that has the highest structure density, the average RMSD to native is 2.35 Å.

As a reference, we also list in the right hand columns of Table 1 the results of refined models from the publicly available comparative modeling program modeller (2, 3), using the same templates from sal. The average RMSD of the best of top five models by modeller is 3.74 Å (average rank of 2.9; here, the rank of modeller models is decided by their objective function), with 2.71 Å in the aligned regions. In general, successful modeling in modeller has a stronger dependence on the template coverage than in tasser. For example, if we look at those targets with >90% coverage (437 in total), the average RMSDs of the full-length models by tasser and modeller are fairly close, i.e., 1.56 Å and 2.19 Å, respectively. However, for targets with initial alignment coverage <75% (386 in total), the average RMSDs from native to models using tasser and modeller are 2.92 Å and 6.05 Å, respectively, a significant difference. Overall, in 1,120 targets, tasser models have a lower RMSD to native, where the alignment coverage in those targets is on average 81%. For 102 targets, modeller does better, where the coverage is on average 92%. Nevertheless, both procedures lead to the conclusion that the structure alignments produced by sal can produce buildable models.

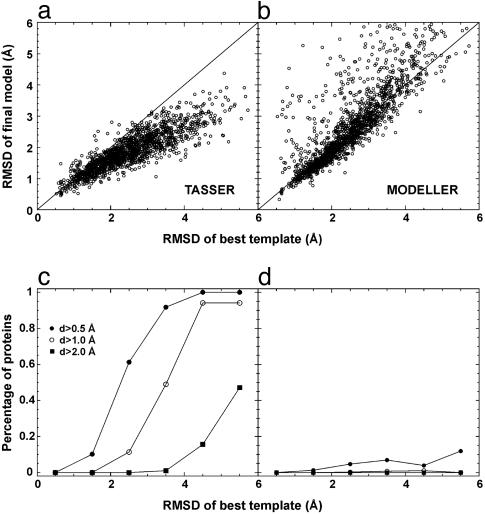

Improvements of Initial Alignment. In Fig. 3, we plot a detailed comparison of the final models with respect to the template in the aligned regions. In the majority of cases, tasser models show obvious improvement (see Fig. 3a). As shown in Fig. 3c, for targets having initial templates of aligned regions with an RMSD ranging from 2 to 3 Å, for ≈61% of these cases, the models have at least a 0.5-Å improvement; and for initial alignments with an initial RMSD from 3 to 4Å, in ≈49% of cases, the final models improve by at least 1.0 Å. This result is partly because the force field takes consensus information from multiple templates, which can have higher accuracy/confidence than that from individual templates. In tasser, the local fragments from individual templates are rearranged under the guide of the force field, and the global topology can therefore move closer to native. This consensus information is further reinforced during the final model combination procedure of spicker clustering (35). Another factor that contributes to the improvement is the protein-like energy terms, representing an optimal combination of statistical potentials, hydrogen bonds, and secondary structure predictions that lead to better side-chain and backbone structure packing than in the initial template-based alignments (27, 32).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of initial and final alignments to the target structure. (a) Scatter plot of RMSD from native of the final models built by tasser refinements versus RMSD from native of the initial template alignments identified by sal. The same aligned regions are used in both RMSD calculations. (b) Similar data as in a, but the models are from modeller refinements. (c) Fraction of targets with an RMSD improvement “d” by tasser greater than some threshold value. Here d = (RMSD of template) – (RMSD of final model), where both RMSDs are calculated over aligned regions. Each point in c is calculated with a bin width of 1 Å. (d) Similar data as in c, but the models are from modeller.

In Fig. 3 b and d, we also show the comparison between the models generated by modeller and the initial template alignments. In the majority of cases, modeller keeps the topology of models near the template, which is understandable because it was designed to optimally satisfy the spatial restraints from templates for homologous proteins (2, 3). However, in a few cases (≈10%), the modeller models can be >1 Å worse than the initial templates.

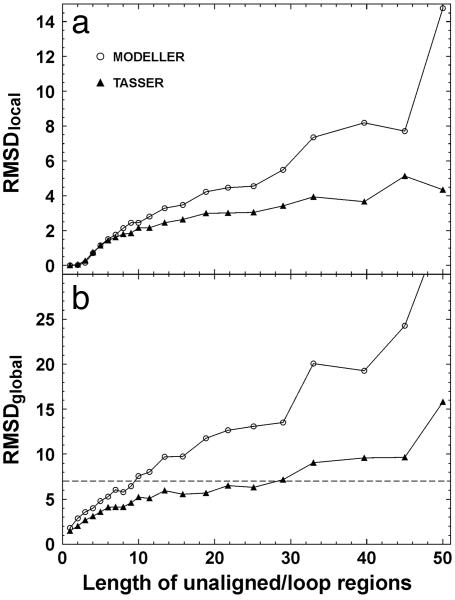

Modeling Unaligned/Loop Regions. Because there is no spatial information provided from the template alignments, modeling the unaligned or loop regions is a hard, unsolved problem (3, 38, 39). Here, we define an unaligned or loop region (including tails) as a piece of continuous sequence that has no coordinate assignment in the sal template alignments. For each piece of those sequences, two types of accuracy are calculated (3): RMSDlocal denotes the RMSD between native and the modeled loop with direct super-position of the unaligned region; RMSDglobal is the RMSD between native and modeled loop after superposition of up to five neighboring stem residues on each side of the loop (for tails, the supposition is done on the side including five stem residues). RMSDlocal measures the modeling accuracy of the local conformation, whereas RMSDglobal measures both the accuracy of the local conformation and the global orientation.

There are in total 11,380 unaligned/loop regions with size from 1–84 residues in the 1,489 targets. In Fig. 4, we show the average values of RMSDlocal and RMSDglobal of tasser and modeller models versus loop length L. In both cases, the accuracy of loop modeling decreases with increasing loop size. However, for all size ranges, the loops in tasser models have lower average RMSDlocal and RMSDglobal. If we make a cutoff of RMSDglobal <7 Å in Fig. 4b, modeller generates reasonable models for unaligned/loop regions of length up to 10 residues; tasser can have the same accuracy cutoff for the loops up to 28 residues. If using a lower RMSDglobal cutoff, the acceptable loop size in both approaches will decrease, and the difference between modeller and tasser becomes smaller.

Fig. 4.

RMSDlocal (a) and RMSDglobal (b) of unaligned/loop regions as a function of loop length (L). tasser and modeller models are denoted by triangles and circles, respectively. The lines connecting the points serve to guide the eye. The dashed line in b denotes an RMSDglobal cutoff of 7 Å.

Most unaligned regions/loops in sal alignments are of small size, which are relatively easier to model because of the limited configuration entropy. If we focus only on the unaligned loops of length greater than or equal to four residues, there are 1,675 cases with an average length of 8.8 residues. The distribution of modeling accuracy is summarized in Table 2. Consistent with Fig. 4a, the distribution of RMSDlocal is quite close using tasser and modeller. However, tasser shows an obviously better control of loop orientations. For example, in one-third (549/1,675) of the cases, including loops and tails, tasser generates models of RMSDglobal <3 Å, whereas the fraction of modeller models having RMSDglobal <3 Å is around one-seventh (244/1,675).

Table 2. Result of modeling of unaligned/loop regions (≥4 residues) by tasser and modeller.

|

tasser

|

modeller

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSDlocal* | RMSDglobal* | RMSDlocal* | RMSDglobal* | |

| NRMSD<6† | 1,670 | 1,386 | 1,633 | 1,011 |

| NRMSD<5 | 1,664 | 1,199 | 1,603 | 800 |

| NRMSD<4 | 1,631 | 924 | 1,528 | 507 |

| NRMSD<3 | 1,527 | 549 | 1,342 | 244 |

| NRMSD<2 | 1,173 | 193 | 1,009 | 64 |

| NRMSD<1 | 519 | 18 | 498 | 10 |

| RMSD, Å | 1.62 | 4.34 | 2.02 | 6.59 |

See text for definitions of RMSDlocal and RMSDglobal.

No. of targets with a RMSD below the specified threshold (Å).

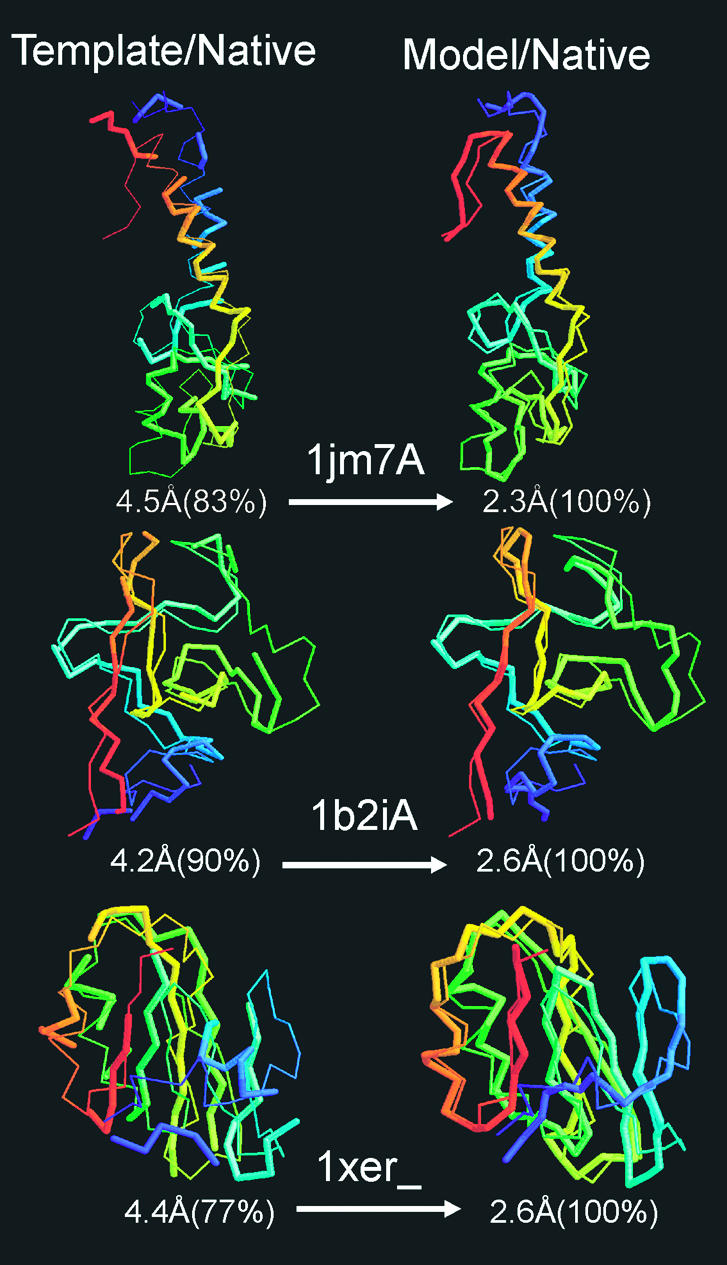

Representative Examples. In Fig. 5, three representative examples of tasser modeling results are provided: 1jm7A (an α-protein), 1b2iA (a β-protein), and 1xer (an αβ-protein). In all three, the template topologies in the core identified by sal are quite similar to native (<5 Å); however, the local packing of the fragments and sometimes the termini are misoriented. Rearrangement using the tasser force field results in a >2 Å improvement in the aligned region.

Fig. 5.

Representative examples showing the improvement of final models with respect to their initial template alignments. The left column is the superposition of the template alignments and native, and the right column is that for refined models and native. The thin lines are native structures; the thick lines signify templates or final models. Blue to red runs from N to C terminus. The numbers in parentheses are the coverage of the templates or models on which the denoted RMSD has been calculated.

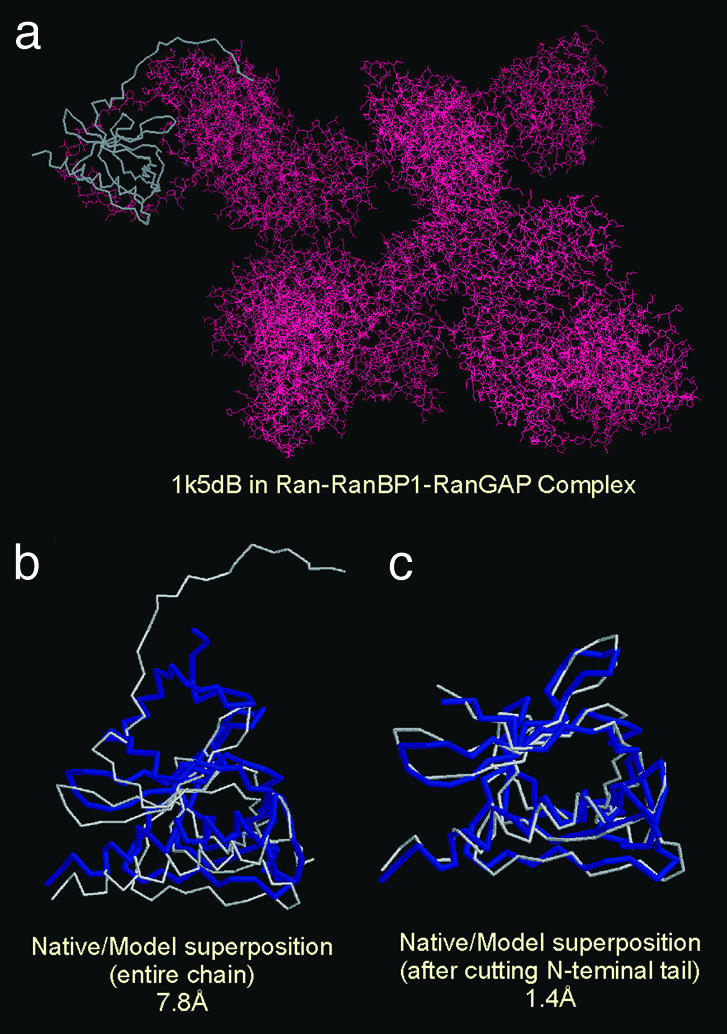

In Fig. 6, we show the predicted structure of 1k5dB, one of the two cases where tasser failed to generate models with an RMSD to native below 6 Å. This is a Ran-binding protein (Ran-BP1), i.e., chain B of the Ran-RanBP1–RanGAP protein complex (40), which has a long tail interacting with chain A (Ran). Because interactions with partner chains are not included, we failed to model the configuration of the tail; this case results in a full-length RMSD of 7.8 Å to native. If we cut the first 22 residues in the N terminus associated with intermolecular interactions, the core region of the first model has a 1.4-Å RMSD (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

A representative example of targets where the final model has an RMSD to native >6 Å. The native structure of 1k5dB is shown in white with thin backbones; the predicted model of the highest cluster density in blue with thick backbones. The red wire-frame in a denotes the partner chains in the Ran-RanBP1–RanGAP complex. (a) 1k5dB in the entire complex. (b) Native model superposition. (c) As in b but with the tail cut off.

New Fold Targets in CASP5. We revisit the new fold targets in the CASP5 folding experiment (10), because, by definition, those targets putatively adopt a novel tertiary topology (1). However, as shown in Table 3, there are still more or less similar folds found in PDB, although the sequence identity is very low (≈7% on average). The new entries in PDB released later than the CASP5 prediction season are not included in our template library. On average, these templates have shorter alignments (≈73% coverage) with higher RMSD (≈3.8 Å) than those identified for the benchmark proteins. Still, acceptable models can be built from the initial template alignments using tasser, with an average RMSD from native of 2.87 Å for the first predicted model.

Table 3. Folding results for the new fold targets in CASP5.

| PDB ID | CASP5 ID | Length | RTali, Å* (%) | RMali, ņ | R5, Ň | R1, ŧ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1h40_ | T0170 | 69 | 2.81 (83) | 1.57 | 1.70 (2) | 1.79 |

| 1iznC | T0162_3 | 168 | 5.82 (61) | 3.28 | 3.05 (2) | 3.31 |

| 1m6yB | T0172_2 | 101 | 3.31 (71) | 2.62 | 2.79 (1) | 2.79 |

| 1nyn_ | T0181 | 111 | 5.10 (74) | 3.88 | 3.94 (1) | 3.94 |

| 1o0uB | T0187_1 | 165 | 3.61 (56) | 3.10 | 3.56 (1) | 3.56 |

| 1o12C | T0186_3 | 36 | 2.16 (94) | 1.71 | 1.82 (1) | 1.82 |

| Average | 108.3 | 3.80 (73) | 2.69 | 2.81 (1.3) | 2.87 | |

ali, aligned.

RMSD to native of the best template (RT) and the alignment coverage.

RMSD from the final model (RM) to native over initial aligned regions.

RMSD to native for the best model in the top five. The number in parentheses is the rank of the best model.

RMSD to native for the rank-one model.

Concluding Remarks

In this article, we examined the issues of whether all single-domain proteins are foldable based on the set of solved structures currently deposited in PDB (1) and whether the templates can be further improved by rearranging the fragments. We used our structure alignment algorithm, sal (20), to identify the best possible target–template pairs, and then attempted to build and refine the full-length model using the template assembly/refinement algorithm tasser (27). This strategy was applied to a comprehensive PDB benchmark set of 1,489 medium-size, single-domain proteins. With homologous proteins excluded, similar folds can be found for all benchmark proteins, and the majority have a RMSD to native <4 Å over >70% of their sequence. On average, the RMSD between template and native is 2.51 Å with ≈82% alignment coverage. After tasser, the average RMSD in the aligned region improves to 1.88 Å. The average global RMSD of unaligned/loop/tail regions (≥4 residues) generated by tasser is 4.3 Å. Almost all targets have at least one full-length model in the top five with an RMSD to native below 6 Å (97% are below 4 Å). The average RMSD to native is 2.25 Å, comparable with the accuracy of low-to-moderate-resolution experimental structures. In this sense, the answer to the question of completeness of the current PDB library for model construction of single-domain proteins is quite positive. Not only can physically reasonable models be built, but, starting from structural alignments, there is a significant improvement in many models; 349/1,489 targets have a RMSD improvement of >1.0 Å in the aligned region. Thus, it is suggestive that the barrier to structure refinement noted in CASP5 (10) has been broken.

In contrast to previous approaches, there are several reasons that contribute to the improvement of model quality compared with initial templates. First, the force field includes multiple sources of knowledge-based potentials and consensus tertiary restraints from multiple templates. The consensus spatial information usually has higher accuracy/confidence than that of individual templates. Second, the combination of the different types of energy terms was optimized on the basis of a large-scale set of structure decoys (including 100 × 60,000 extrinsic targets/structures) to yield an optimized potential that can provide better packing of the side-chains and peptides. This improvement occurs because of a better correlation between model quality and energy (the correlation coefficient between RMSD and the combined potential for test cases is ≈0.7). Finally, templates usually contain unphysical alignments because chain connectivity was not considered in the initial alignments. The reassembly procedure of tasser that converts these unphysical alignments into physical models also contributes to the improvement in model quality relative to that of the initial template alignment. Unlike many other comparative modeling approaches, e.g., modeller (2), whose goal is to optimally satisfy the spatial restraints of an initial template, the relative orientation of template fragments, and therefore global topology in tasser models, can change. On the other hand, the local conformation of the continuous fragments is kept rigid during the modeling procedure, which helps the models retain the accuracy of well-aligned regions from native and reduces the conformational entropy.

For the more realistic situation where templates/alignments are identified by using our threading program prospector_3 (6), the success rate for the same benchmark set of targets proteins is about two-thirds (where a foldable case is defined if one of top five full-length models has an RMSD below 6.5 Å to native) (27). The results reported here highlight the urgent need to develop more efficient fold recognition algorithms that can provide acceptable templates for the remaining one-third of proteins, as well as better alignments to improve the overall quality of the predictions. In previous work (27), we also observed an improvement in the models relative to their initial template alignments, but because threading models tend to be of poorer quality than those obtained from structural alignments, it could be argued that the results are not that significant (i.e., the predicted models might be poorer than the best structural alignments). Here we have demonstrated that even when the best structural alignments are used, we can often improve the models. This demonstration represents significant progress in the field.

Because the average sequence identity between the target proteins and the best templates identified here is only ≈13%, much lower than the “twilight zone” of sequence identity, correctly aligning the sequence to these templates will be a major challenge. This result is certainly true for our threading program, prospector_3, where for ≈90% of targets, at least one correct fold can be identified in a large scale test; however, only around 62% were aligned correctly (6).

The results reported here provide a lower bound to the completeness and utility of the current PDB library. Certainly, the structure alignment program sal is not perfect. It is not guaranteed to find the best structural alignment because the final alignment in this algorithm is sensitive to the initial guessed superposition. In recent work (unpublished results), we found that using the alignment from other software [in particular, ce (14)] as the initial alignment in sal results in structure alignments of longer coverage and lower RMSD to native. Better structure alignment algorithms only serve to identify better templates from the PDB, which should result in better final models than reported here. Nevertheless, even now, it seems that the library of the solved protein structures is complete at the level of single-domain proteins. This structure completeness should have significant implications for both protein structure prediction and structural genomics (21, 23).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants GM-37408 and GM-48835.

Appendix: Multiple-Template-Based SG Pair Potential

The protein-specific pair potential in our force field (term iv in the potential) is calculated from the identified multiple templates by using

|

[1] |

where q(i, j) is the number of SG contacts between residues i and j in all of the templates; Q(i, j) is the number of templates that have both residue i and j aligned; and q0(i, j, N/L) is the expected probability of contacts between residues i and j for a random chain of size L having a given total contact number N. The average 〈...〉 is over all aligned pairs of (i, j); the shift sets the potential in gapped regions equal to the average magnitude of that in the aligned regions.

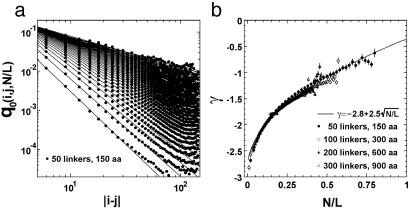

To calculate q0(i, j, N/L), we performed a Monte Carlo calculation of the freely jointed chain (FJC) model (41, 42) with excluded volume. Fig. 7a shows the result for q0(i, j, N/L) from a random chain of 50 linkers. The contact probability of the FJC follows a power-law over more than three orders of magnitude: q0(i, j, N/L) ≈ |i – j|γ(N/L). Similar results are also obtained from the chains with 100, 200, and 300 linkers (data not shown). In Fig. 7b, γ as a function of different scaled contact-numbers, (N/L), is presented. The data are well fit by:  .

.

Fig. 7.

Side-chain contact probability for random chains as a function of chain length. (a) Contact probability q0(i,j,N/L) for the ith and jth residues at given scaled contact-numbers, N/L, versus the distance |i – j| along the protein chain, from simulations of an FJC of 50 linkers with excluded volume. The Kuhn-length of the FJC is taken to be 11.4 Å, according to experimental single protein molecule stretching data (43). The definition of excluded volume is introduced on the basis of the minimal observed Cα distance in the PDB, i.e., no pair of linkers of the FJC could go closer than 4.5 Å. Contacts are defined based on a weighted average of Cα distances for contacting residues in the PDB, i.e., a contact occurs if two linkers are closer than 7.27 Å. The curves are the least square fits to the power-law at each given N/L.(b) The power γ versus the scaled contact-number N/L. Data are from the FJC of different lengths, i.e., 50-, 100-, 200-, and 300-residue linkers, which correspond to the protein lengths of 150, 300, 600, and 900 residues, respectively, because one Kuhn-length here corresponds approximately to three Cα–Cα backbone lengths. The error bars denote the power-law fitting errors of a. The curve denotes the least square fit equation: γ = –2.8 + 2.5√N/L.

Integration of the contact probability results in a power-law: P(i, j) ≡ ΣN/L q0(i, j, N/L) ∼ |i – j|–1.84, which coincides with the estimate from a Gaussian random chain with excluded volume that has a power of –9/5 (41).

Author contributions: J.S. designed research; Y.Z. and J.S. performed research; Y.Z. analyzed data; and Y.Z. and J.S. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: RMSD, rms deviation; SG, side-chain group; FJC, freely jointed chain.

References

- 1.Berman, H. M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T. N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I. N. & Bourne, P. E. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sali, A. & Blundell, T. L. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiser, A., Do, R. K. & Sali, A. (2000) Protein Sci. 9, 1753–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowie, J. U., Luthy, R. & Eisenberg, D. (1991) Science 253, 164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones, D. T. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 287, 797–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skolnick, J., Kihara, D. & Zhang, Y. (2004) Proteins 56, 502–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant, S. H. & Altschul, S. F. (1995) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 5, 236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moult, J., Hubbard, T., Fidelis, K. & Pedersen, J. T. (1999) Proteins 37, Suppl. 3, 2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moult, J., Fidelis, K., Zemla, A. & Hubbard, T. (2001) Proteins 45, Suppl. 5, 2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moult, J., Fidelis, K., Zemla, A. & Hubbard, T. (2003) Proteins 53, Suppl. 6, 334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor, W. R., Flores, T. P. & Orengo, C. A. (1994) Protein Sci. 3, 1858–1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holm, L. & Sander, C. (1995) Trends Biochem. Sci. 20, 478–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibrat, J. F., Madej, T. & Bryant, S. H. (1996) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6, 377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shindyalov, I. N. & Bourne, P. E. (1998) Protein Eng. 11, 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holm, L. & Sander, C. (1996) Science 273, 595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murzin, A. G., Brenner, S. E., Hubbard, T. & Chothia, C. (1995) J. Mol. Biol. 247, 536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orengo, C. A., Michie, A. D., Jones, S., Jones, D. T., Swindells, M. B. & Thornton, J. M. (1997) Structure 5, 1093–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang, A. S. & Honig, B. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 301, 665–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison, A., Pearl, F., Mott, R., Thornton, J. & Orengo, C. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 323, 909–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kihara, D. & Skolnick, J. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 334, 793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skolnick, J., Fetrow, J. S. & Kolinski, A. (2000) Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baxter, S. M. & Fetrow, J. S. (2001) Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 4, 291–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker, D. & Sali, A. (2001) Science 294, 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arakaki, A. K., Zhang, Y. & Skolnick, J. (2004) Bioinformatics 20, 1087–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marti-Renom, M. A., Stuart, A. C., Fiser, A., Sanchez, R., Melo, F. & Sali, A. (2000) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29, 291–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tramontano, A. & Morea, V. (2003) Proteins 53, Suppl. 6, 352–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang, Y. & Skolnick, J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 7594–7599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Needleman, S. B. & Wunsch, C. D. (1970) J. Mol. Biol. 48, 443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerstein, M. & Levitt, M. (1996) Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 4, 59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Betancourt, M. R. & Skolnick, J. (2001) J. Comp. Chem. 22, 339–353. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones, D. T. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 292, 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, Y., Kolinski, A. & Skolnick, J. (2003) Biophys. J. 85, 1145–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolinski, A. & Skolnick, J. (1998) Proteins 32, 475–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, Y., Kihara, D. & Skolnick, J. (2002) Proteins 48, 192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang, Y. & Skolnick, J. (2004) J. Comput. Chem. 25, 865–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glusker, J. P. (1994) Methods Biochem. Anal. 37, 1–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner, G., Hyberts, S. G. & Havel, T. F. (1992) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 21, 167–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosimann, S., Meleshko, R. & James, M. N. (1995) Proteins 23, 301–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin, A. C., MacArthur, M. W. & Thornton, J. M. (1997) Proteins 29, Suppl. 1, 14–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seewald, M. J., Korner, C., Wittinghofer, A. & Vetter, I. R. (2002) Nature 415, 662–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doi, M. & Edwards, S. F. (1986) The Theory of Polymer Dynamics (Clarendon Press, Oxford).

- 42.Zhang, Y., Zhou, H. J. & Ouyang, Z. C. (2001) Biophys. J. 81, 1133–1143.11463654 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rief, M., Fernandez, J. M. & Gaub, H. E. (1998) Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 4764–4767. [Google Scholar]