Abstract

Purpose

To assess risk factors for visual impairment in a high-risk population of people: those without medical insurance. Secondarily, we assessed risk factors for remaining uninsured after implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and evaluated whether the ACA changed demand for local safety net ophthalmology clinic services one year after its implementation.

Methods

In a retrospective cohort study of patients who attended a community-academic partnership free ophthalmology clinic in Southeastern, Michigan between September 2012 – March 2015, we assessed the prevalence of presenting with visual impairment, the most common causes of presenting with visual impairment and used logistic regression to assess socio-demographic risk factors for visual impairment. We assessed the initial impact of the ACA on clinic utilization. We also analyzed risk factors for remaining uninsured one year after implementation of the ACA private insurance marketplace and Medicaid expansion in the state of Michigan.

Results

Among 335 patients, one-fifth (22%) presented with visual impairment; refractive error was the leading cause for presenting with visual impairment. Unemployment was the single significant risk factor for presenting with visual impairment after adjusting for multiple confounding factors (OR = 3.05, 95% CI 1.19–7.87, p=0.01). There was no difference in proportion of visual impairment or type of vision-threatening disease between the insured and uninsured (p=0.26). Seventy six percent of patients remained uninsured one year after ACA implementation. Patients who were white, spoke English as a first language and were US Citizens were more likely to gain insurance coverage through the ACA in our population (p≤ 0.01). There was a non-significant decline in the mean number of patient treated per clinic (52 to 43) before and after ACA implementation (p=0.69).

Conclusion

Refractive error was a leading cause for presenting with visual impairment in this vulnerable population, and being unemployed significantly increased the risk for presenting with visual impairment. The ACA did not significantly reduce the need for our free ophthalmology services. It is critically important to continue to support safety net specialty care initiatives and policy change to provide care for those in need.

Keywords: Ophthalmology, safety net clinic, Charity care, Affordable Care Act, Uncorrected refractive error, Risk factors for visual impairment, Poverty

Introduction

Prior to full implementation of the ACA in early 2014, 49 million United States (US) residents were uninsured [1], with 1.1 million uninsured residing in Michigan [2]. While 11.7 million adults gained insurance through the ACA nationwide over its first two open enrollment periods in 2014 and 2015, 37.3 million remain uninsured in the US and approximately 0.3 million remained uninsured in Michigan [2,3]. Visually impaired adults in the US are more likely to lack insurance coverage than non-visually impaired adults, with an estimated 1.5 million visually impaired US adults without insurance coverage [4].

In US in 2015, a total of 1 million people were blind, and approximately 3.22 million people were visually impaired. An additional 8.2 million people had visual impairment due to uncorrected refractive error. As the population ages, these numbers are projected to double by 2050 with estimates of 2 million people blind, 7 million people with visual impairment and 16.4 million with visual impairment due to uncorrected refractive error [5,6]. Older adults and minorities are currently, and will continue to be, disparately affected by visual impairment [5,7]. A few global and national studies have identified various risk factors for visual impairment, including: older age [5,8–11], time since last eye exam [8], lower educational attainment [8,9,12], living in a rural area [9,11], being unemployed [9], and being of lower socioeconomic status [10–13].

In our academic-community-free clinic partnership to provide free ophthalmic care to the uninsured from two counties in Southeast Michigan, we had the opportunity to assess risk factors for visual impairment in a local high-risk population of people: those without medical insurance. We also assessed risk factors for remaining uninsured after ACA implementation and evaluated whether the ACA changed demand for the safety net clinic services.

Materials and Methods

Study population

The study population included all patients who were referred for ophthalmic care at the free clinic between September 2012 – March 2015. In 2011, the University of Michigan began a partnership with the Hope Clinic, a non-profit organization that provides free primary care, dental care and social services to uninsured, low-income individuals in Southeast Michigan. Hope Clinic has two sites, one in Ypsilanti, Washtenaw County, Michigan and one in Westland, Wayne County, Michigan. The collaboration provides ophthalmology referral services to patients seen through either Hope Clinic site. Providing specialty care at the Hope Clinic itself is not feasible as the clinic lacks necessary specialty equipment. Therefore, the University allowed its physicians to volunteer to see Hope patients in University clinics with full access to necessary equipment outside standard hours.

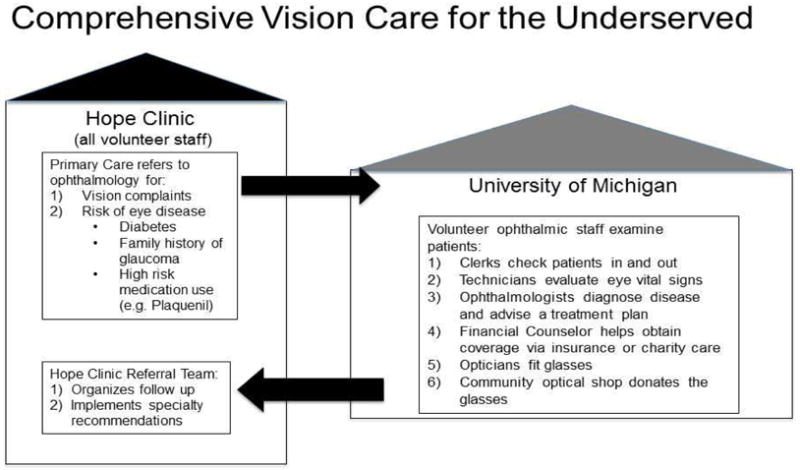

Hope primary care physicians refer patients to the ophthalmology clinic that occurs every two months on a Saturday. Referred patients include those who have vision complaints, are at high risk for eye disease including those with diabetes, a family history of glaucoma, or high risk medication use such as Plaquenil. Patient charts are brought from Hope Clinic for the University volunteer physicians, and then Hope Clinic facilitates the implementation of physician recommendations. Glasses are provided free of charge through a partnership established between a local optical shop (Stadium Opticians, Ann Arbor, MI) and the University. The frames are donated by the university, and the lenses are made by the optical shop. Any patients that require surgical intervention or complex medical care meet with a financial counselor during the clinic to sign up for charity care for the University if they are not eligible for insurance through the marketplace or through Medicaid (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

System for comprehensive vision care provided by a collaborative effort between the Hope Clinic and the University of Michigan, Department of Ophthalmology.

On January 1, 2014, people who had enrolled in private insurance plans through the first open enrollment period (10/1/2013 – 2/15/2014) of the ACA became insured. On April 1, 2014, additional patients gained coverage through Medicaid by Michigan’s Medicaid expansion program, Healthy Michigan [6]. Healthy Michigan expanded Medicaid coverage to those at or below 133% of the federal poverty level ($16,000 for a single person or $33,000 for a family of four) from 100% of the federal poverty level ($12,000 for a single person or $24,800 for a family of four) [14]. Government subsidies were available on the private insurance marketplace for those people earning up to 400% of the federal poverty level. The second open enrollment period for private insurance plans through the ACA was November 15, 2014 – February 15, 2015. We divided our Hope Clinic patient population into those who became insured and those who remained uninsured after two rounds of enrollment in the ACA and the initiation of Healthy Michigan.

Measurements

At each visit, clinical testing included: visual acuity, manifest refraction, pupillary response, extra ocular motility and alignment, confrontation visual fields, intraocular pressure (Goldmann applanation tonometry), slit lamp biomicroscopy and dilated fundus exam (DFE). Visual fields (Humphrey 24-2) were performed if deemed necessary by the ophthalmologist. Demographic data were abstracted from the medical record and included: gender, age, race/ethnicity, primary language, homelessness status, marital status, student status, and residency status. Financial information was abstracted from each subject’s financial questionnaire, a standard Hope Clinic intake form and included: employment status, occupation, medical coverage, monthly income, and number of dependents. Insurance status was abstracted from the Hope Clinic medical record at the time of the analysis.

Main outcome measures

The main outcomes were rates of visual impairment (presenting visual acuity < 20/40 in the better-seeing eye), prevalence of vision threatening eye disease and risk factors for presenting with visual impairment. Vision threatening eye disease was defined as any ocular disease that could lead to visual impairment or blindness if left untreated. Vision threatening diagnoses were grouped into 7 categories by an ophthalmologist (PANC). These included diabetes, glaucoma, retina, refractive error, anterior segment disease, cataract, and neuro-ophthalmology. The specific diagnoses included in the categories are detailed in Appendix 1 (available online). We separated the population into those who obtained insurance after the implementation of the ACA and Healthy Michigan and those who remained uninsured. Secondary outcomes included socio-demographic risk factors for remaining uninsured after healthcare expansion.

Data analysis

We summarized participant characteristics for the entire sample using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. We used Chi-square tests, Fisher exact tests and two-sample t-tests to assess the associations between demographic characteristics and visual impairment status. Logistic regression was used to predict the odds of visual impairment using imputed data sets to account for missing covariates. Odds ratios, confidence intervals, and p-values were calculated by combining point estimates and variances from the analysis on each imputed dataset. We plotted the number of patients seen and percentage of patients requiring new glasses over time from November 2011 to March 2015. Third order regression curves were fit to the line graphs. We used Fisher exact tests, Chi-square tests, and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test to evaluate the association between demographic characteristics and insurance status. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS institute, Cary, NC).

IRB approval was obtained from the University of Michigan and adheres to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

The study population included 335 participants, of whom 43% were male (n=144) and the mean age was 56 years (±12 years). The average no-show rate to the eye clinics was 18.4% (range 6.1%–33.9%). Of the 335 participants, 168 (50%) were white, 84(25%) were African/African-American, 38(11%) were Asian, 27(8%) were of other ethnicities, including Hispanic and Middle Eastern and 18(6%) had no recorded race/ethnicity. Ninety-one patients (27%) did not speak English as their first language and 231(69%) were unemployed (Table 1). Of these participants, 31 became insured before the ACA programs were implemented. Of the 304 remaining participants, only 71 became insured through the ACA programs, leaving 233(76%) uninsured more than one year after health insurance expansion. The majority of patients who obtained health insurance were approved for Medicaid (61%) while 39% became insured through the private marketplace.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics by visual impairment (visual acuity of 20/40 or worse in best-seeing eye), N (column %) or Mean (SD).

| Covariate | Value | Not Visually Impaired | Visually Impaired | Total | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 260 | 75 | 335 | ||

| Age | 55.2 (11.7) | 58.2 (12.3) | 55.9 (11.9) | 0.06 a | |

| Gender | Male | 107 (41.2) | 37 (49.3) | 144 (43.0) | 0.21 b |

| Female | 153 (58.8) | 38 (50.7) | 191 (57.0) | ||

| Homeless | No | 228 (87.7) | 65 (86.7) | 293 (87.5) | 0.77 c |

| Yes | 4 (1.5) | 2 (2.7) | 6 (1.8) | ||

| Missing | 28 (10.8) | 8 (10.7) | 36 (10.7) | ||

| Marital Status | Never Married | 47 (18.1) | 11 (14.7) | 58 (17.3) | 0.57 b |

| Married | 109 (41.9) | 33 (44.0) | 142 (42.4) | ||

| Divorced | 46 (17.7) | 12 (16.0) | 58 (17.3) | ||

| Separated | 5 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.5) | ||

| Widowed | 18 (6.9) | 9 (12.0) | 27 (8.1) | ||

| Missing | 35 (13.5) | 10 (13.3) | 45 (13.4) | ||

| Ethnicity | White | 130 (50.0) | 38 (50.7) | 168 (50.1) | 0.36 c |

| Black/African | 67 (25.8) | 17 (22.7) | 84 (25.1) | ||

| Hispanic Latino | 7 (2.7) | 3 (4.0) | 10 (3.0) | ||

| Asian | 31 (11.9) | 7 (9.3) | 38 (11.3) | ||

| Middle Eastern | 9 (3.5) | 1 (1.3) | 10 (3.0) | ||

| Other | 3 (1.2) | 4 (5.3) | 7 (2.1) | ||

| Missing | 13 (5.0) | 5 (6.7) | 18 (5.4) | ||

| First Language | English | 169 (65.0) | 42 (56.0) | 211 (63.0) | 0.07 b |

| Not English | 63 (24.2) | 28 (37.3) | 91 (27.2) | ||

| Missing | 28 (10.8) | 5 (6.7) | 33 (9.9) | ||

| Citizenship Status | US Citizen | 174 (66.9) | 40 (53.3) | 214 (63.9) | 0.20 b |

| Permanent Resident | 65 (25.0) | 27 (36.0) | 92 (27.5) | ||

| Visitor | 13 (5.0) | 5 (6.7) | 18 (5.4) | ||

| Missing | 8 (3.1) | 3 (4.0) | 11 (3.3) | ||

| Employed | No | 168 (64.6) | 63 (84.0) | 231 (69.0) | 0.002 b |

| Yes | 80 (30.8) | 8 (10.7) | 88 (26.3) | ||

| Missing | 12 (4.6) | 4 (5.3) | 16 (4.8) | ||

| Number of Dependents (Nmiss = 60) | 2.0 (1.5) | 1.9 (1.5) | 1.9 (1.5) | 0.65 a | |

| Monthly Income, $ (Nmiss = 59) | 1112.2 (914.0) | 973.2 (1415.6) | 1082.0 (1042.3) | 0.36 a | |

| Insurance | Before Private Plans Effective | 22 (8.5) | 9 (12.0) | 31 (9.3) | 0.35 b |

| After Private Plans Effective | 59 (22.7) | 12 (16.0) | 71 (21.2) | ||

| None | 179 (68.8) | 54 (72.0) | 233 (69.6) | ||

| Primary Diagnosis | Diabetes | 124 (47.7) | 18 (24.0) | 142 (42.4) | 0.007 b |

| Glaucoma | 24 (9.2) | 9 (12.0) | 33 (9.9) | ||

| Retina | 18 (6.9) | 4 (5.3) | 22 (6.6) | ||

| Anterior Segment | 6 (2.3) | 4 (5.3) | 10 (3.0) | ||

| Cataract | 27 (10.4) | 18 (24.0) | 45 (13.4) | ||

| Neurophthalmology | 11 (4.2) | 3 (4.0) | 14 (4.2) | ||

| Non-Vision-Threatening Eye Disease | 9 (3.5) | 3 (4.0) | 12 (3.6) | ||

| Refractive Error | 41 (15.8) | 16 (21.3) | 57 (17.0) |

Two-sample t-test;

Chi-square test;

Fisher exact test

Visual impairment

Of the patients who presented to the Hope Ophthalmology Clinic, 75 (22%) were visually impaired. The top four primary diagnoses of vision threatening eye disease were diabetes (142/335) (42.4%), refractive error (57/335) (17.0%), cataract (45/335) (13.4%) and glaucoma (33/335) (9.9%). Those with visual impairment were more likely to have a diagnosis of glaucoma, cataract, refractive error or anterior segment disease (p=.007). Though diabetics were the largest category of patients with potentially vision-threatening disease, they were not most likely to be visually impaired. Among the 142 patients with diabetes, 37 patients (26%) had diabetic retinopathy; the majority of the retinopathy did not cause visual impairment. Those who were visually impaired were more likely to be unemployed (84% vs. 65%, p=0.002). There was no significant difference in the likelihood of visual impairment by age, gender, homeless status, marital status, income, race/ethnicity, citizenship or insurance status (p >0.05 for all comparisons). Those who were unemployed had a 205% increased odds of being visually impaired compared to those who were employed after adjusting for multiple confounding factors in multivariable analysis [OR = 3.05, 95% CI 1.19–7.87, p=0.01] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression predicting odds of visual impairment using imputed datasetsa.

| Covariate | Value | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 0.62 (0.33, 1.17) | 0.10 |

| Male | REF | ||

| Homeless | Homeless | 1.71 (0.20, 14.40) | 0.58 |

| Not Homeless | REF | ||

| Marital Status | Never Married | 1.41 (0.53, 3.76) | 0.44 |

| Previously Married | 1.37 (0.60, 3.08) | 0.41 | |

| Currently Married | REF | ||

| Ethnicity | Not White | 0.68 (0.33, 1.37) | 0.23 |

| White | REF | ||

| First Language | Not English | 1.38 (0.49, 3.93) | 0.50 |

| English | REF | ||

| Citizenship Status | Permanent Resident | 0.61 (0.15, 2.57) | 0.46 |

| Visitor | 0.94 (0.23, 3.78) | 0.92 | |

| US Citizen | REF | ||

| Employed | Not Employed | 3.05 (1.19, 7.87) | 0.01 |

| Employed | REF | ||

| Insurance | Not Insured | 1.40 (0.61, 3.23) | 0.39 |

| Insured After Private Plans Effective | REF | ||

| Number of Dependents | 0.95 (0.74, 1.22) | 0.67 | |

| Age, Five-Year Increments | 1.03 (0.88, 1.20) | 0.69 | |

| Income, $100 Increments | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.50 |

REF: Reference category; OR: Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval; p-values< 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Odds ratios, confidence intervals, and p-values calculated by combining point estimates and variances from analyses on each imputed dataset using the formulae given in Rubin (1987b) and Li, Raghunathan, and Rubin (1991).

Insurance coverage

Though there was a trend demonstrating that fewer of those with visual impairment gained insurance coverage, with 23% of the uninsured population being visually impaired compared to 17% of the insured population, this was not statistically significant (p=0.26), (Table 1). Likewise, there was no significant difference among types of vision-threatening disease between those who did and did not become insured (p=0.16). However, there was an interesting trend among glaucoma patients where the prevalence of glaucoma was much lower (3%) among those who became insured compared to those who did not (11%) (Table 1). Among those who became insured, 69% were white, 16.9% were African-American, 2.8% were Latino and 1.4% were Asian compared to those who never became insured among whom 45.5% were white, 28% were African-American, 3.0% were Latino and 14% were Asian. White patients were significantly more likely to obtain insurance coverage through the ACA (p< 0.01). Patients who spoke English as a first language were more likely to gain insurance coverage through the ACA (p=0.01) (Table 1). US Citizens were more likely to gain insurance coverage through the ACA compared to Permanent Residents (p< 0.01), (Table 1). There was no difference in mean age, gender, homeless status, or marital status between those who did and did not gain insurance coverage (p >0.05), (Table 1).

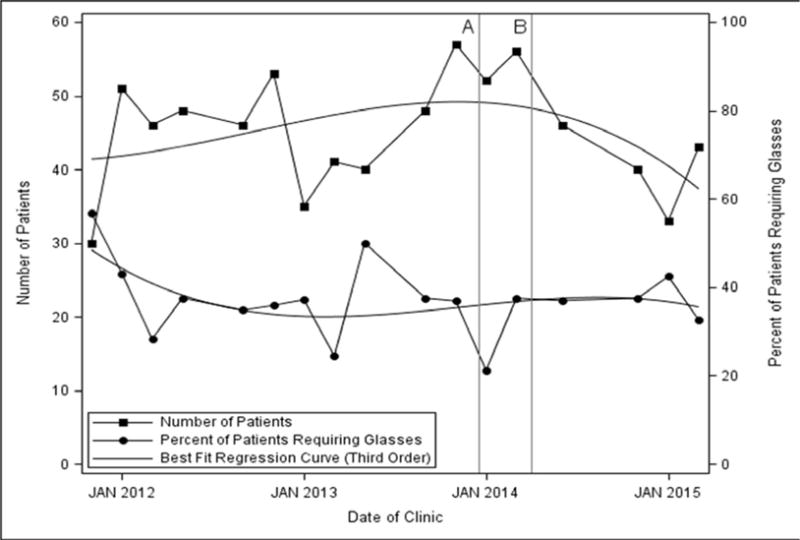

Demand for free clinic services

Though there was a decline in the mean number of patients treated per clinic (52 to 43) before and after health insurance coverage expansion, this was not statistically significant (p=0.69) (Figure 2). Additionally, the percent of patients in need of glasses at each visit remained constant over time. Approximately one-third of patients (38.4%) needed glasses prior to ACA implementation compared to 34.7% after (p=0.62) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of patients seen and percent of patients requiring glasses at the Hope-Kellogg Clinic from November 2011 through March 2015. Time points A and B represent the times at which ACA private insurance plans and Medicaid Expansion plans became effective, respectively.

Discussion

One-fifth (22%) of patients who presented to the Hope Ophthalmology clinic were visually impaired. Visual impairment was most likely due to uncorrected refractive error, cataract or glaucoma. Among this population at high risk for visual impairment due to their limited financial means and lack of health insurance, unemployment remained the single most important predictor of presenting with visual impairment. Those who were unemployed had more than double the odds of presenting with visual impairment compared to those who were employed. In a population-based study in Korea, Rim and colleagues also found a more than double the odds of visual impairment among those who were unemployed (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.0–10.9, p< 0.05) [9]. Employer sponsored health insurance currently comprises two thirds (66.7%) [15], of all insurance in the US, even after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Alongside having fewer financial resources to access insurance without being employed, the lack of employer sponsored health insurance may also be playing a role in making unemployment such a significant risk factor for lacking health insurance.

About one-fifth (23%) of patients seen in this free clinic gained insurance through the ACA. The majority (61%) of the patients who became insured obtained insurance through Healthy Michigan, the Michigan Medicaid expansion program, which is comparable to what was seen on a state-wide level where 69% of those who became insured during this time period did so through Medicaid expansion [3]. There was a non-significant trend demonstrating that fewer of those people presenting with visual impairment gained insurance coverage (23% of the uninsured population presented with visual impairment compared to 17% of the insured population). There was also a trend demonstrating that fewer of those patients with glaucoma gained insurance coverage (11% of the uninsured population had glaucoma compared to 3% of the insured population). Patients, who were white, spoke English as a first language and were US. citizens were much more likely to gain insurance coverage through the ACA compared to racial/ethnic minority patients, non-native English speaking patients, or patients who were permanent residents. These data demonstrate that among a population of lower socio-economic status, there were racial and ethnic disparities in access to health insurance even after the implementation of the ACA.

Implementation of the ACA did not significantly decrease demand for the free ophthalmology services over the study period. Demand for glasses remained steady, with refractive error remaining a leading cause of visual impairment both before and after ACA implementation. Our study findings demonstrate that there is a continued need for safety net clinic programs in our community, especially among traditionally underserved populations.

While the number of patient visits to our free eye clinic program began to trend downwards after the implementation of health care expansion, the percent of patients in need of glasses remained steady. Interestingly, we even had patients return for “glasses only” visits after becoming insured. While Healthy Michigan offers eye exams and new glasses every 24 months, private insurance only provides glasses coverage as a separate add-on plan for an additional fee. In Michigan during the 2013–2014 open enrollment periods, only 13% of those who purchased insurance through the private marketplace elected to purchase the separate vision care option [7]. Those with Medicaid coverage for glasses face other barriers to obtaining glasses, such as difficulty finding optical shops that accept Medicaid. Potential barriers to using covered vision services is an area that requires more in-depth research.

The issue of insurance coverage for spectacle correction is quite important. Refractive error is the leading cause of correctable visual impairment in the US, accounting for 80% of visual impairment among people ≥12 years old [16]. Those with visual impairment due to uncorrected refractive error report worse physical functioning, general health, social functioning, mental health [17], and quality of life [18,19]. Though these negative outcomes can be easily ameliorated by spectacle correction, financial barriers keep many people from this easy solution [20,21].

Providing an examination and glasses to every US citizen with refractive error over the age of 40 would cost an estimated $5.5 billion annually [16,22,23]. Uncorrected refractive error is estimated to lead to a net productivity loss of at least $6.5 billion per year [23]. If we attempt to add in the cost of unemployment compensation to the net productivity loss for only one-quarter of those with uncorrected refractive error, as we know that those people are much more likely to face unemployment, we uncover an even larger financial burden. Using the national average of $300/week × 26 weeks of unemployment compensation, we find an additional burden of $35.7 billion, leaving the system with $42.4 billion of unintended expenditures that could be mitigated with $5.5 billion to correct refractive error. Uncorrected refractive error is not only a burden to individuals, but also to society.

Therefore, in creating a program to attempt to address the vision health needs of our local community, it was important to be able to provide glasses for free or an affordable fee. The only way in which we were able to consistently provide glasses was through the unique public-private partnership we established between our university, a local free clinic and a local optical shop. Collecting used glasses and trying to re-dispense them was quite time consuming and led to suboptimal refraction for each patient. Local charities did not have the capacity to provide this volume of glasses. Our university optical shop identified a community partner who was willing to donate glasses for each patient, and Stadium Optical has now dispensed over 300 pairs of glasses free-of-charge in the last four years.

Similarly, we found it imperative to be able to get patients definitive treatment if needed. There was a higher prevalence of patients who had glaucoma among those who did not gain insurance coverage compared to those who did. Glaucoma is a chronic disease that requires long-term treatments to mitigate the risks of blindness. It is but one example of an ophthalmic disease that requires more intensive treatment than can be provided in a screening clinic setting. Therefore, we had patient financial counselors present who enrolled patients in charity care if needed.

This academic-free clinic partnership was unique in that it focused both on screening and helping patients obtain definitive care. This program framework could be a paradigm that could be replicated to provide vision care for other uninsured populations. In this study, we found that there was still a significant need for free ophthalmic services after the passage of health care reform. However, many safety net clinics have faced threats to their funding sources due to the perception that their services were no longer needed since ACA implementation, and some free clinics have even had to close their doors [24–26]. Continued funding for safety net clinic initiatives to help uninsured patient’s access definitive ophthalmic treatment is imperative in ameliorating needless visual impairment in the US.

This study had a number of limitations. Our population was limited to those uninsured people who receive primary care from the Hope Clinic, and is not representative of the entire uninsured community in our state. We could not track visual acuity or disease status outcomes in patients once they became insured as they generally no longer attended our clinic. This study only assessed outcomes one year after implementation of the ACA; outcomes may continue to change as people have more continuous access to health insurance and health care. We did not track the number of patients who came for follow-up after being referred for more intensive medical or surgical care; this is an area we plan to evaluate in the future.

Conclusion

Unemployment was a significant risk factor for living with visual impairment in a low-income population presenting to a free ophthalmology clinic. The most common reason to present with visual impairment was uncorrected refractive error. Uncorrected refractive error remains a serious challenge in the US. Uncorrected refractive error has a very simple solution, glasses, and yet for many people this simple solution remains out of reach. Policy change, insurance reform and free outreach programs must continue to work to ameliorate this needless cause of visual impairment.

Acknowledgments

National Eye Institute 1K23EY02532 (PANC), Research to Prevent Blindness (PANC), National Eye Institute K23EY023596 (MAW).

Appendix 1

Vision-Threatening Ophthalmic Diagnoses.

| Glaucoma |

|

| Retina |

|

| Diabetes |

|

| Anterior Segment |

|

| Cataract |

|

| Neuro-ophthalmology |

|

| Refractive Error |

|

References

- 1.ASPE Issue Brief Report. Health Insurance Marketplaces Open Enrollment Period: March Enrollment Report. Published 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Census Shows Decline in Number of Uninsured in Michigan. Michigan Primary Care Association; Published 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shigekawa E, Lausch K, Corneail L, Fangmeier J, Udow-Phillips M. The Impact of the Affordabe Care Act in Michigan. The Impact of the Affordable Care Act in Michigan. Published 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiang Y, Jayitt J, Metrick S. Health Insurance Coverage and Medical Care Utilization among Working-Age Americans with Visual Impairment. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1994;1:41–52. doi: 10.3109/09286589409071444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varma R, Vajaramant TS, Burkemper B, Wu Shuang, Torres mina, Hsu C, et al. Visual Impairment and Blindness in Adults in the United States: Demographic and Geographic Variations from 2015–2050. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:802–809. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health Reform. How Will the Uninsured in Michigan Fare Under the Affordable Care Act. Published 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Profiles of Affordable Care Act Coverage Expansion Enrollment for Medicaid/CHIP and the Health Unsurance Marketplace, 10-1-2013-3-31-2014. ASPE; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson BE, Feng Y, Fonn D, Woods CA, Gordon KD, Gold D. Risk Factors For Visual Impairment-Report From A Popuation-based Study (C.U.R.E.S.) Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2011;52:4217. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rim T, Nam J, Choi M, Lee S, Lee C. Prevalence and risk factors of visual impairment and blindness in Korea: the Fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2008–2010. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92:e317–e325. doi: 10.1111/aos.12355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher D, Shrager S, Shea SJ, Burke GL, Klein R, Wong TY, et al. Visual Impairment in White, Chinese, Black, and Hispanc Participants from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Cohort. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22:321–332. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1066395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park S, Lee J, Heo H, Suh YW, Kim SH, Lim KH, et al. A nationwide population-based study of low vision and blindness in South Korea. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2014;58:484–493. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou C, Beckles G, Zhang X, Saaddine J. Association of Socioeconomic Position With Sensory Impairment Among US Working-Aged Adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1262–1268. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whillans J, Nazroo J. Social Inequality and Visual Impairment in Older People. J Gerontol Ser B, Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv163. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Healthy Michigan.

- 15.Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitale S, Ellwein L, Cotch M, Ferris F, Sperduto R. Prevalence of refractive error in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1111–1119. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.8.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chia E, Wang J, Rochtchina E, Smith W, Cumming R, Mitchell P. Impact of bilateral visual impairment on health-related quality of life: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2004;45:71–76. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munoz B, West S, Rodriguez J, Sanchez R, Broman AT, Snyder R, et al. Blindness, visual impairment and the problem of uncorrected refractive error in a Mexican-American population: Proyecto VER. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2002;43:608–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broman A, Munoz B, Rodriguez J, Sanchez R, Quiqley HA, Klein R, et al. The impact of visual impairment and eye disease on vision-related quality of life in a Mexican-American population: Proyecto VER. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2002;43:3393–3398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider J, Leeder S, Gopinath B, Wang J, Mitchell P. Frequency, Course, and Impact of Correctable Visual Impairment (Uncorrected Refractive Error) Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55:539–560. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodges L, Berk M. Unmet need for eyeglasses: results from the 1994 Robert Wood Johnson Access to Care Survey. J Am Optom Assoc. 1999;70:261–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vitale S, Cotch M, Sperduto R, Ellwein L. Cost of refractive correction of distance vision impairment in the United States, 1999–2002. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2163–2170. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rein D, Zhang P, Wirth K, Lee PP, Hoerger TJ, Klein R, et al. The economic burden of major adult visual disorders in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1754–1760. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon E. National Public Radio. Health Care Law Puts Free Clinics At A Crossroads. Published 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galewitz P. Kaiser Health News. Obamacare Creates “Upheaval” At Free Clinics. Published 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armour S. The Wall Street Journal. Health Law Hurts Some Free Clinics. Published 2014. [Google Scholar]