Abstract

Background

Identifying current major dietary sources of sodium can enhance strategies to reduce excess sodium intake, which occurs among 90% of US school-aged children.

Objective

To describe major food sources, places obtained, and eating occasions contributing to sodium intake among US school-aged children.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of data from the 2011–2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Participants/setting

A nationally representative sample of 2,142 US children aged 6 to 18 years who completed a 24-hour dietary recall.

Main outcome measures

Population proportions of sodium intake from major food categories, places, and eating occasions.

Statistical analyses performed

Statistical analyses accounted for the complex survey design and sampling. Wald F tests and t tests were used to examine differences between subgroups.

Results

Average daily sodium intake was highest among adolescents aged 14 to 18 years (3,565±120 mg), lowest among girls (2,919±74 mg). Little variation was seen in average intakes or the top five sodium contributors by sociodemographic characteristics or weight status. Ten food categories contributed to almost half (48%) of US school-aged children’s sodium intake, and included pizza, Mexican-mixed dishes, sandwiches, breads, cold cuts, soups, savory snacks, cheese, plain milk, and poultry. More than 80 food categories contributed to the other half of children’s sodium intake. Foods obtained from stores contributed 58% of sodium intake, fast-food/pizza restaurants contributed 16%, and school cafeterias contributed 10%. Thirty-nine percent of sodium intake was consumed at dinner, 31% at lunch, 16% from snacks, and 14% at breakfast.

Conclusions

With the exception of plain milk, which naturally contains sodium, the top 10 food categories contributing to US schoolchildren’s sodium intake during 2011–2012 comprised foods in which sodium is added during processing or preparation. Sodium is consumed throughout the day from multiple foods and locations, highlighting the importance of sodium reduction across the US food supply.

Keywords: Sodium, Salt, School, Child, Adolescent

About 90% of US children aged 6 to 18 years consume excess dietary sodium1 and one in nine children ages 8 to 17 years have blood pressure above the normal range for their age, sex, and height,2 which increases their risk of high blood pressure as adults.3,4 Reducing sodium intake can reduce blood pressure in children and adults.5,6 It is especially important to reduce sodium intake among children because taste preferences formed in childhood can influence food preferences as adults.7 The 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend Americans consume <2,300 mg sodium per day and suggest that specific subgroups further limit sodium intake.8 The Institute of Medicine’s Tolerable Upper Intake Level for sodium is 1,900 mg/day for children aged 4 to 8 years, 2,200 mg/day for children aged 9 to 13 years, and 2,300 mg/day for those aged 14 years and older.9 A variety of governmental and nongovernmental organizations encourage Americans to select nutrient-dense foods and to limit intakes of solid fats, added sugars, and sodium.8,10–12 Sodium reduction strategies such as industry efforts to reduce sodium in food products, as well as strategies implemented during the 2014–2015 school year as part of the Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act13 to gradually reduce sodium in school foods, complement a total diet approach for adherence to the Dietary Guidelines.8 Current data help establish a baseline for monitoring the influence of sodium reduction strategies.

Previously, data were unavailable for Asian Americans, a growing segment of the US population.14 Sources of sodium intake may differ between Asian Americans and other race/ ethnic groups. In the 2011–2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), non-Hispanic Asian participants were oversampled to allow separate estimates for this group.15 As in previous years,1 identifying major food categories, places obtained, and eating occasions (meals or snacks) contributing to sodium intake can help develop more effective strategies for sodium reduction and provide the most current data about specific race/ethnic groups, now including Asian-American children. Most of the sodium Americans eat is not naturally inherent in the food, or added by the consumer at the table, but from sodium added during commercial processing or preparation.16

Determining the food types, places, and times contributing most to sodium intake can help determine whether a targeted approach would be effective. In addition, examining the amount of sodium consumed per calorie (sodium density) can help researchers and policy makers understand whether differences in sodium intake between population race/ethnic groups, or other subgroups, or across places or eating occasions are due to differences in consumption of energy, a sodium-dense diet, or both.

The current analyses are also important given several recent changes made to the US Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) in 2011–2012, which is used to code dietary intake data in this analysis,17 and improvements to the categorization of foods. The addition of new codes for commercial and restaurant foods, enhanced and fortified foods, and changes in coding and categorization to reflect the current marketplace allow for an up-to-date representation of top food sources contributing to sodium intake. This analysis describes sodium intake, sodium density (milligrams of sodium per 1,000 kcal), and the food categories, places obtained, and eating occasions contributing to sodium intake among US children aged 6 to 18 years during 2011–2012, before the implementation of the sodium targets for school foods authorized under the Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act.13

METHODS

For these analyses we used data from the 2011–2012 NHANES, a nationally representative, ongoing survey of the US noninstitutionalized population. The National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board reviewed and approved all NHANES protocol and content, and written consent was obtained from all participants. Parental consent was obtained for all children younger than age 18 years, and child assent was also obtained for children aged 7 to 17 years. To select participants, a complex, multistage probability sampling design was used with oversampling of selected populations, including, for the first time in 2011–2012, non-Hispanic Asians.15 Of the 2,336 children aged 6 to 18 years selected for participation, 2,142 completed an initial, in-person, 24-hour dietary recall as part of What We Eat in America (WWEIA), the dietary intake portion of NHANES.18

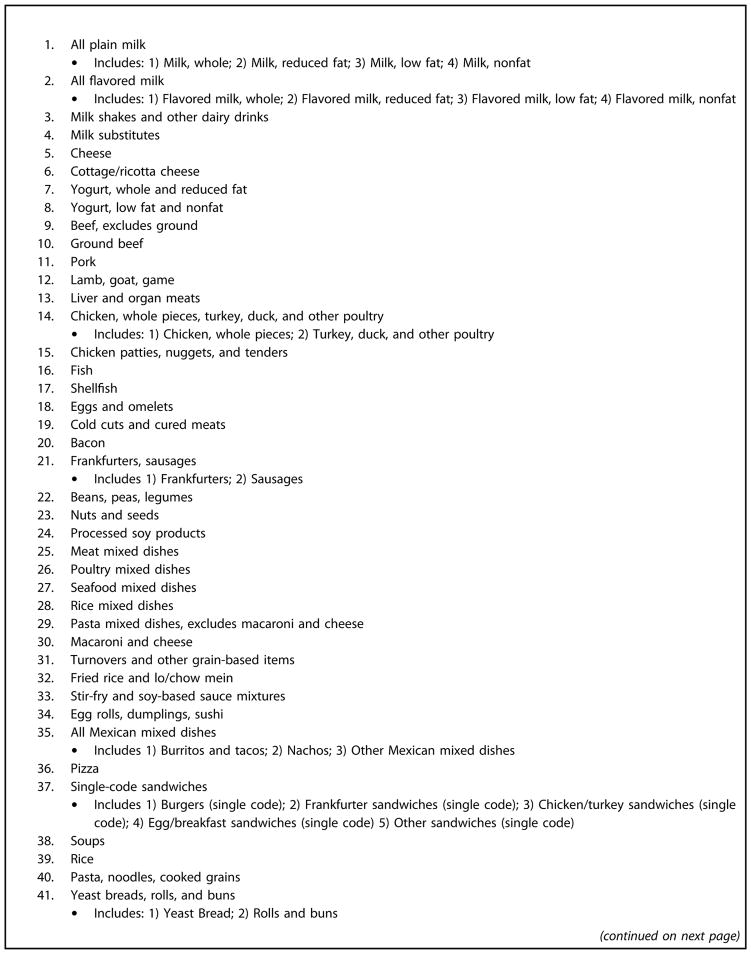

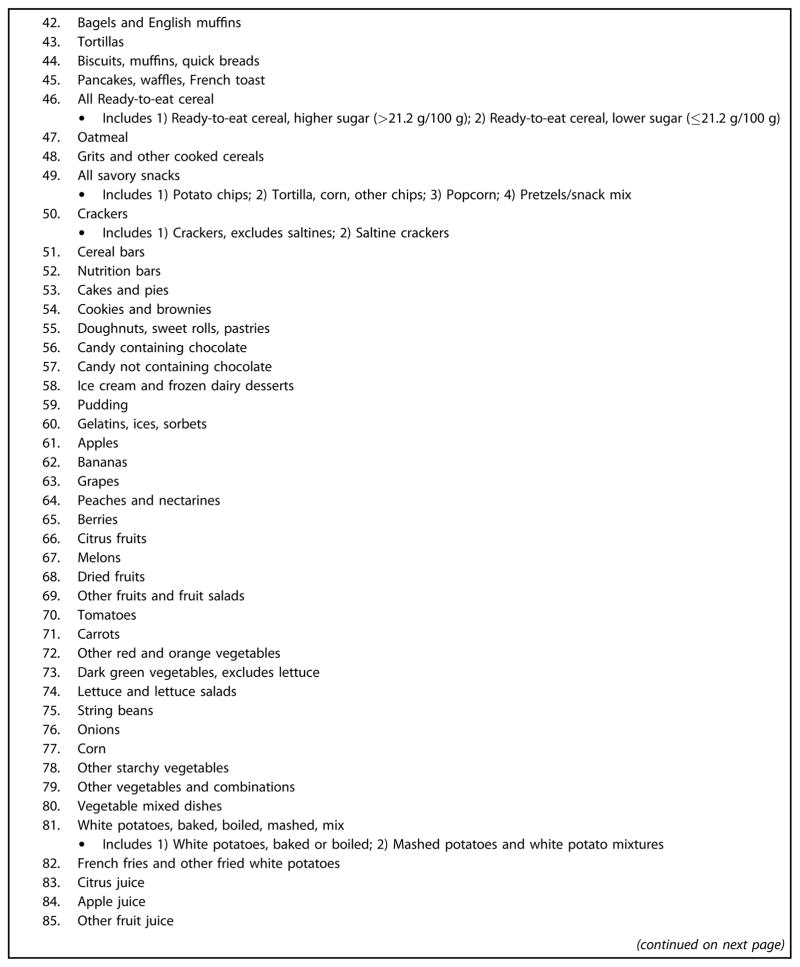

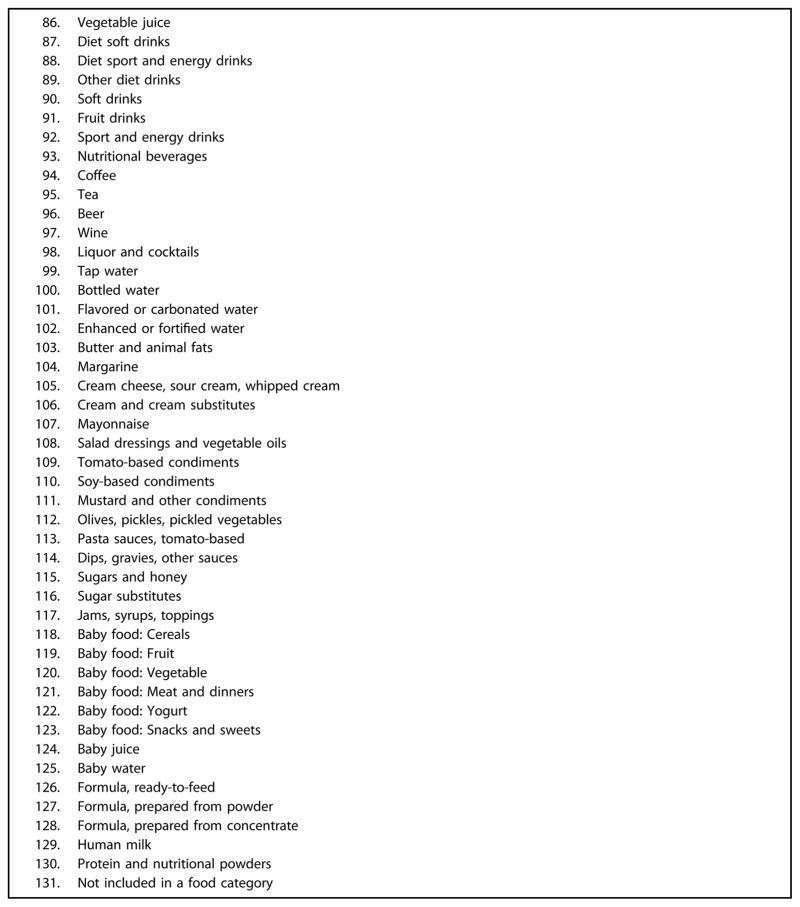

During the 24-hour dietary recall, information collected includes food descriptions, additions, amounts consumed, and any foods or beverages eaten in combination, for all foods and beverages consumed during the previous 24-hour period. Information is self-reported by the participant (aged 12 to 18 years) or the participant assisted by a proxy (aged 6 to 11 years), the person responsible for preparing the participant’s meals. Each food is assigned a food code from the FNDDS and the corresponding nutrient intake for each food and beverage is estimated from the reported amount consumed. Each FNDDS food code is placed in one of 152 independent WWEIA food categories by grouping similar foods and beverages together on the basis of use and nutrient content.19 Thirty-two food categories that were similar were consolidated into fewer groups (eg, whole, low-fat, reduced-fat, and nonfat plain milk combined into one category for plain milk), resulting in 131 categories for the present analysis (available in the Figure [available online at www.andjrnl.org]).

Figure.

Food categories used in the analysis (131 categories). Those that are composed of several What We Eat in America categories have the What We Eat in America categories listed below the main category.

The top 10 food categories that contribute the most to population sodium consumption were identified and ranked based on their percent contribution to the total sodium intake among US children aged 6 to 18 years (calculated as the sum of the sodium from foods consumed from a category, divided by the sum of sodium consumed from all foods from all children aged 6 to 18 years, and multiplied by 100), excluding salt added at the table.20 In addition, the top 10 food categories contributing the most to sodium intake among US children aged 6 to 18 years were examined by age groups, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, and weight status, and the population proportion of total sodium intake was examined by place obtained (ie, store, fast-food/pizza restaurant, restaurant with a waiter/waitress, school cafeteria, and other) and by eating occasion (ie, breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snack) overall and by age group. The code for “store” included, but was not limited to grocery stores, supermarkets, warehouse stores, farmers markets, and convenience-type stores. Restaurants were distinguished by service from a waiter or waitress (eg, coffee shops or food courts without a waiter/waitress are considered fast-food restaurants).

Additional calculations determined the population proportion of sodium consumed at lunch from each place obtained (proportion of sodium obtained from each source at lunch, divided by proportion from all sources at lunch, multiplied by 100).20 Average sodium intake (milligrams per day) and average sodium density were examined overall and by sociodemographic characteristics and weight status, by eating occasion, and by place obtained. Estimates of average sodium intake excluded sodium from salt added at the table due to the difficulty in quantifying the amount of salt added at the table. Average sodium density was defined as milligrams of sodium per 1,000 kcal consumed. Wald F tests were used to examine overall differences between subgroups. Univariate t tests were used to examine differences between all subgroups; for example, children aged 6 to 10 years were compared with children aged 11 to 13 years, and 14 to 18 years, and children aged 11 to 13 years were compared with children aged 14 to 18 years. The Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons and only significant differences are reported in the results (P<0.05). Analyses were conducted using sample weights for the initial, in-person 24-hour dietary recall and SUDAAN version 11 statistical software21 was used to account for the complex survey design.

RESULTS

Mean daily sodium intake for children aged 6 to 18 years was 3,256 mg, excluding salt added at the table, and 89% of children had daily sodium intakes >2,300 mg on the day of assessment. No differences in mean sodium intake were observed by race or ethnic group (including non-Hispanic Asians), household income, or child weight status (Table 1). Average sodium intake was highest among high school–aged children (aged 14 to 18 years) and significantly higher than intakes among elementary school–aged children (aged 6 to 10 years) (P<0.001). Girls had significantly lower daily sodium intake than boys (Table 1). Mean sodium density was 1,607 mg sodium/1,000 kcal overall and differed by age group (P=0.005) and obesity status (P=0.04), but not by sex, race/ ethnicity, or household income (Table 1). Middle school– aged children consumed, on average, significantly more sodium per calorie (ie, a more sodium-dense diet), compared with elementary school–aged children (P=0.03). Although high school–aged children also appeared to have a more sodium-dense diet than elementary school–aged children, the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.12), adjusting for multiple testing. Average energy consumption differed by age, sex, and race/ethnicity, and was significantly higher among children aged 14 to 18 years vs 11 to 13 years, boys vs girls, and Hispanics vs non-Hispanic Asians (P<0.05).

Table 1.

Mean daily sodium intake, energy intake, and sodium density by age group, sex, race/ethnicity, household income, and weight status: What We Eat in America, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, US children aged 6 to 18 years, 2011–2012

| Variable | na | Mean sodium consumed | Mean energy consumed | Sodium density |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg/d±standard error | kcal/d±standard error | mg/1,000 kcal±standard error | ||

| Total | 2,142b | 3,255.8±79.4 | 2,040.5±29.5 | 1,606.8±23.5 |

| Age group (y) | ||||

| 6–10 | 958 | 3,051.2±61.1 | 1,968.6±35.3 | 1,550.5±25.6 |

| 11–13 | 488 | 3,116.8±151.2 | 1,915.0±79.9 | 1,651.3c±31.5 |

| 14–18 | 696 | 3,564.7c±120.4 | 2,197.7d±56.4 | 1,639.4±30.8 |

| P valuef | 0.0001 | 0.003 | 0.005 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1,094 | 3,584.0±102.0 | 2,243.3±40.3 | 1,606.2±30.7 |

| Female | 1,048 | 2,919.3±74.0 | 1,832.6±29.5 | 1,607.5±27.1 |

| P valuef | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.97 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 500 | 3,231.4±110.9 | 2,053.7±42.2 | 1,585.2±34.2 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 623 | 3,106.1±67.0 | 1,973.3±63.9 | 1,598.5±24.3 |

| Hispanic | 646 | 3,342.3±113.9 | 2,104.5±58.2 | 1,589.1±20.8 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 259 | 3,138.3±139.3 | 1,857.0e±52.7 | 1,733.8±93.4 |

| P valuef | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.09 | |

| Household income relative to federal poverty level | ||||

| ≤130% | 909 | 3,141.6±72.2 | 1,990.0±29.5 | 1,583.6±22.0 |

| >130%–185% | 269 | 3,309.6±165.4 | 1,988.7±61.5 | 1,649.6±62.9 |

| >185% | 813 | 3,332.9±107.2 | 2,087.9±48.9 | 1,614.9±28.5 |

| P valuef | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.21 | |

| Weight statusg | ||||

| Normal | 1,295 | 3,289.5±11.2 | 2,084.6±43.5 | 1,588.1±29.4 |

| Overweight/obese | 771 | 3,239.3±91.8 | 1,981.0±42.4 | 1,644.7±27.7 |

| P valuef | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.04 | |

Unweighted number of participants.

Includes other race/ethnicities not shown separately.

Statistically significant difference compared with children aged 6 to 10 years, by t tests adjusted for multiple comparisons, P<0.05.

Statistically significant difference compared with children aged 11 to 13 years, by t tests adjusted for multiple comparisons, P<0.05.

Statistically significant difference compared with Hispanics, by t tests adjusted for multiple comparisons, P<0.05.

P value for overall differences across subgroups, determined by Wald F test. For subgroups with two categories, t tests also indicate significant differences.

Normal was defined as body mass index for age and sex between the fifth and 85th percentiles. Overweight/obese was defined as a body mass index for age and sex ≥85th percentile, based on specific reference values from the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. Difference in means compared with normal weight status.

The top 10 food categories contributing to sodium intake among US children and adolescents were pizza; Mexican mixed dishes (eg, burritos and tacos); single code sandwiches (eg, fast-food/restaurant burgers, chicken, egg, and frankfurter sandwiches); yeast bread, rolls, and buns; cold cuts and cured meats; soups; savory snacks (eg, potato chips and popcorn); cheese; plain milk; and chicken, whole pieces, turkey, duck, or other poultry (Table 2). These 10 food categories contributed 48% of the sodium consumed by US children aged 6 to 18 years, and the top five food categories contributing to sodium intake were among the top 10 food category contributors in each sociodemographic and weight status group examined (Table 2 and Table 3 [available online at www.adjrnl.org]). The remaining 52% of sodium intake came from 82 of the other 121 food categories.

Table 2.

Ranked population proportions of sodium consumeda by selected food categories, age groups, sex, and race/ethnicities: What We Eat in America, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, US children aged 6 to 18 years, 2011–2012

| Rankb | Food categoryc | 6–18 y overall | Age Group (y)

|

Sex

|

Race/Ethnicity

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–10 | 11–13 | 14–18 | Male | Female | Non- Hispanic white | Non- Hispanic black | Hispanic | Non- Hispanic Asian | |||

| ← %±standard error → | |||||||||||

| 1 | Pizza | 9.1±0.9 | 9.3±1.5 | 8.2±1.1 | 9.5±1.4 | 10.1±1.4 | 7.8±0.8 | 8.8±1.2 | 7.1±0.9 | 11.1±2.0 | 8.4±1.6 |

| 2 | All Mexican mixed dishesd | 6.7±1.0 | 7.0±1.1 | 5.6±1.3 | 7.0±1.4 | 6.8±1.4 | 6.5±1.1 | 5.7±1.0 | 3.9±0.8 | 10.0±1.5 | 4.5±1.7 |

| 3 | All single-code sandwichese | 5.9±0.4 | 6.2±0.9 | 5.2±1.0 | 6.0±0.5 | 6.4±0.8 | 5.3±0.6 | 6.0±0.7 | 7.9±0.7 | 5.7±0.9 | 2.7±0.7 |

| 4 | Yeast breads, rolls, and bunsf | 5.6±0.2 | 5.8±0.4 | 5.0±0.3 | 5.9±0.3 | 5.7±0.4 | 5.5±0.3 | 6.0±0.3 | 5.2±0.5 | 5.4±0.5 | 5.6±0.8 |

| 5 | Cold cuts and cured meats | 4.9±0.5 | 5.6±0.9 | 4.7±1.2 | 4.5±0.5 | 5.0±0.6 | 4.8±0.6 | 5.5±0.8 | 3.8±0.6 | 3.9±0.5 | 3.6±0.6 |

| 6 | Soups | 3.4±0.4 | 3.0±0.6 | 6.1±1.3 | 2.3±0.4 | 3.2±0.5 | 3.7±0.9 | 2.4±0.6 | 2.5±0.6 | 4.4±0.8 | 8.2±2.5 |

| 7 | All savory snacksg | 3.3±0.3 | 3.1±0.2 | 4.1±0.7 | 3.0±0.4 | 3.3±0.4 | 3.3±0.4 | 3.2±0.3 | 4.4±0.3 | 3.1±0.3 | 3.1±0.6 |

| 8 | Cheese | 3.2±0.3 | 3.4±0.4 | 2.9±0.6 | 3.2±0.7 | 2.8±0.2 | 3.7±0.7 | 3.5±0.6 | 3.2±0.4 | 3.1±0.5 | 1.8±0.3 |

| 9 | All plain milk | 2.9±0.2 | 3.1±0.2 | 3.2±0.4 | 2.6±0.2 | 3.0±0.2 | 2.8±0.3 | 3.1±0.3 | 1.8±0.1 | 2.8±0.3 | 3.3±0.3 |

| 10 | Chicken, whole pieces, turkey, duck, other poultryh | 2.9±0.3 | 2.5±0.3 | 3.2±0.7 | 3.0±0.4 | 2.5±0.4 | 3.3±0.4 | 2.2±0.5 | 5.5±0.8 | 3.0±0.5 | 3.8±0.5 |

The proportion (%) of sodium consumed is defined as the sum of the amount of sodium consumed from each specific food category for all participants divided by the sum of sodium consumed from all food categories for all participants multiplied by 100. All estimates use 24-hour dietary recall, take into account the complex sampling design, and use dietary Day 1 sample weights to account for nonresponse and weekend/weekday recalls.

Rank based on population proportions of sodium consumed for the overall US population aged 6 to 18 years. Columns for other groups are ordered by this ranking.

Additional information regarding What We Eat in America Food Categories is available at the Food Surveys Research Group website (http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=23429). Food categories contributing ≥3% to overall sodium consumption within specific sociodemographic groups but not listed among the top 10 contributors were: children aged 6 to 10 years, all ready-to-eat cereal (3.0%); children aged 11 to 13 years, tomato-based condiments (3.0%); children aged 14 to 18 years, meat mixed dishes (3.5%); male children, meat mixed dishes (3.1%); female children, pasta mixed dishes, excludes macaroni and cheese (3.0%); Hispanic children, eggs and omelets (3.2%), all ready-to-eat cereal (3.1%); non-Hispanic black children, chicken patties, nuggets, and tenders (3.3%), frankfurters, sausages (3.1%), pasta mixed dishes, excludes macaroni and cheese (3.0%); non-Hispanic Asian children, pasta mixed dishes, excludes macaroni and cheese (3.0%) and rice (6.7%).

Burritos and tacos/nachos/other Mexican mixed dishes.

Sandwiches as identified by a single What We Eat in America food code, burgers/frankfurter sandwiches/chicken or turkey sandwiches/egg/breakfast sandwiches/other sandwiches.

Excludes bagels and English muffins.

Potato chips/tortilla, corn, and other chips/popcorn/pretzels/snack mix.

Excludes chicken patties, nuggets, and tenders.

Table 3.

Ranked population proportions of sodium consumeda by selected food categories, household income, and weight status: What We Eat in America, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, US children aged 6 to 18 years, 2011–2012

| Rankb | Food categoryc | 6–18 y overall | Household Income Relative to Federal Poverty Level

|

Weight Statusd

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤130% | >130%–185% | >185% | Normal | Overweight/ obese | |||

| ← %±standard error → | |||||||

| 1 | Pizza | 9.1±0.9 | 9.3±1.5 | 8.2±1.1 | 9.5±1.4 | 10.1±1.4 | 7.8±0.8 |

| 2 | All Mexican mixed dishese | 6.7±1.0 | 7.0±1.1 | 5.6±1.3 | 7.0±1.4 | 6.8±1.4 | 6.5±1.1 |

| 3 | All single-code sandwichesf | 5.9±0.4 | 6.2±0.9 | 5.2±1.0 | 6.0±0.5 | 6.4±0.8 | 5.3±0.6 |

| 4 | Yeast breads, rolls, and bunsg | 5.6±0.2 | 5.8±0.4 | 5.0±0.3 | 5.9±0.3 | 5.7±0.4 | 5.5±0.3 |

| 5 | Cold cuts and cured meats | 4.9±0.5 | 5.6±0.9 | 4.7±1.2 | 4.5±0.5 | 5.0±0.6 | 4.8±0.6 |

| 6 | Soups | 3.4±0.4 | 3.0±0.6 | 6.1±1.3 | 2.3±0.4 | 3.2±0.5 | 3.7±0.9 |

| 7 | All savory snacksh | 3.3±0.3 | 3.1±0.2 | 4.1±0.7 | 3.0±0.4 | 3.3±0.4 | 3.3±0.4 |

| 8 | Cheese | 3.2±0.3 | 3.4±0.4 | 2.9±0.6 | 3.2±0.7 | 2.8±0.2 | 3.7±0.7 |

| 9 | All plain milk | 2.9±0.2 | 3.1±0.2 | 3.2±0.4 | 2.6±0.2 | 3.0±0.2 | 2.8±0.3 |

| 10 | Chicken, whole pieces, turkey, duck, other poultryi | 2.9±0.3 | 2.5±0.3 | 3.2±0.7 | 3.0±0.4 | 2.5±0.4 | 3.3±0.4 |

The proportion (%) of sodium consumed is defined as the sum of the amount of sodium consumed from each specific food category for all participants divided by the sum of sodium consumed from all food categories for all participants multiplied by 100. All estimates use 24-hour dietary recall, take into account the complex sampling design, and use dietary Day 1 sample weights to account for nonresponse and weekend/weekday recalls.

Rank based on population proportions of sodium consumed for the overall US population aged 6 to 18 years. Columns for other groups are ordered by this ranking.

Additional information regarding food categorization is available at the What We Eat in America website (http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=23429). Food categories contributing ≥3% to overall sodium consumption within specific sociodemographic groups but not listed among the top-10 contributors were as follows: children with family income ≤130% of the poverty level, pasta mixed dishes, excludes macaroni and cheese (3.4%), all ready-to-eat cereal (3.1%); family income >130% to 185% of the poverty level, pasta mixed dishes, excludes macaroni and cheese (4.4%), chicken patties, nuggets, and tenders (3.1%); family income >185% of the poverty level, meat mixed dishes (3.5%), tomato-based condiments (3.2%); normal weight children, meat mixed dishes (3.3%); overweight/obese children, tomato-based condiments (3.0%).

Normal was defined as body mass index for age and sex between the fifth and 85th percentiles. Overweight/obese was defined as a body mass index for age and sex ≥85th percentile, based on specific reference values from the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts.

Burritos and tacos/nachos/other Mexican mixed dishes.

Sandwiches as identified by a single What We Eat in America food code, burgers/frankfurter sandwiches/chicken or turkey sandwiches/egg/breakfast sandwiches/other sandwiches.

Excludes bagels and English muffins.

Potato chips/tortilla, corn, and other chips/popcorn/pretzels/snack mix.

Excludes chicken patties, nuggets, and tenders.

Despite similarities in contributions of the top food categories, the ranking for contribution to sodium intake differed for some food categories across population subgroups. For example, among middle school–aged children and non-Hispanic Asian children, soups were the second highest contributor, but fifth or higher in all other age and race or ethnic groups. Among non-Hispanic Asian children, rice (ie, white, brown, yellow, or wild rice with added salt and with or without fat added during cooking) was the third contributor, but it did not fall among the top 10 contributors for any other population subgroup examined (Table 2).

Across the year, including weekends, weekdays, and holidays, 58% of sodium intake was from foods from stores, 16% from foods obtained from fast-food/pizza restaurants, 7% from restaurants with a waiter/waitress, 10% from the school cafeteria, and 10% from other sources, such as gifts or food from vending machines (Table 4). Among all ages, the highest proportion of sodium intake came from foods obtained at the store. Among high school and middle school–aged children, this was followed by foods obtained from fast-food/pizza restaurants, and among elementary school–aged children, by school cafeteria foods. High school–aged children had the lowest proportion of sodium intake from school cafeterias. Among high school–aged children, sodium intake per calorie was highest among foods obtained from sit-down restaurants, followed by foods obtained from the school cafeteria (Table 4).

Table 4.

Population proportions of sodium consumeda and mean sodium, energy, and sodium density intakeb by place obtainedc and age group, What We Eat in America, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, US children aged 6 to 18 years, 2011–2012

| Participants/age groups (y) | Place Obtained

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stored | Restaurant with fast food/pizzad | Restaurant with wait staffd | School cafeteriae | Othere | |

| ← value±standard error → | |||||

| Proportion of sodium (%) | |||||

| 6–18 (N=2,142) | 58.3±1.4 | 15.7±1.3 | 6.7±0.8 | 9.8±1.2 | 9.5±1.0 |

| 6–10 (n=958) | 61.0±2.0 | 11.6±1.6 | 5.2±1.2* | 12.9±1.4 | 9.2±1.5 |

| 11–13 (n=488) | 61.7±2.4** | 14.2±2.0 | 4.9±1.0* | 9.0±1.6* | 10.2±1.3 |

| 14–18 (n=696) | 53.9±2.4 | 20.3±2.3 | 9.2±1.4 | 7.4±2.0* | 9.3±1.3 |

| Mean sodium (mg/d) | |||||

| 6–18 (N=2,142) | 1,897.5±48.5 | 510.5±50.1 | 219.2±24.7 | 320.2±42.3 | 308.3±33.9 |

| 6–10 (n=958) | 1,860.8±76.0 | 355.4±50.2 | 159.1±34.8** | 394.6±40.3 | 281.3±44.5 |

| 11–13 (n=488) | 1,923.2±104.1 | 441.1±72.9 | 151.4±32.3** | 281.7±56.3* | 319.3±37.0 |

| 14–18 (n=696) | 1,920.9±91.0 | 721.9±82.3 | 327.0±48.9 | 264.5±76.4 | 330.4±48.8 |

| Mean energy (kcal/d) | |||||

| 6–18 (N=2,142) | 1,253.1±26.1 | 276.9±22.9 | 116.7±11.8 | 185.7±20.6 | 208.0±20.8 |

| 6–10 (n=958) | 1,243.7±49.4 | 194.9±24.7*** | 87.9±19.3** | 242.4±25.7 | 199.8±22.4 |

| 11–13 (n=488) | 1,224.7±50.7 | 228.5±31.2*** | 84.1±14.9** | 171.7±29.6** | 206.0±26.7 |

| 14–18 (n=696) | 1,281.3±63.9 | 396.1±34.3 | 168.6±21.5 | 133.5±29.1** | 218.2±31.7 |

| Mean sodium density (mg/1,000 kcal) | |||||

| 6–18 (N=2,142) | 1,499.7±36.2 | 1,779.6±66.4 | 2,006.4±148.3 | 1,714.7±96.9 | 1,440.2±92.4 |

| 6–10 (n=958) | 1,457.6±27.3 | 1,755.3±85.7 | 1,891.8±103.9 | 1,645.4±53.4 | 1,201.8±86.4 |

| 11–13 (n=488) | 1,515.2±47.6 | 1,920.0±205.0 | 1,695.2±240.3 | 1,526.6±118.2d | 1,644.6±183.1* |

| 14–18 (n=696) | 1,536.0±83.8 | 1,729.1±100.2 | 2,253.8±312.2 | 2,028.7±222.0 | 1,588.4±143.9** |

The proportion (%) of sodium consumed is defined as the sum of the amount of sodium consumed from each specific food category for all participants divided by the sum of sodium consumed from all food categories for all participants multiplied by 100. All estimates use 24-hour dietary recall, take into account the complex sampling design, and use dietary Day 1 sample weights to account for nonresponse and weekend/weekday recalls.

A measure that accounts for differences in the amount of calories consumed from foods obtained from each source, defined as milligrams of sodium/1,000 kcal.

Place obtained was analyzed from responses to the questions, “Where did you get this (most of the ingredients for this) [food name]?” Sources other than those shown were combined under “other” and included “from someone else/gift,” and 19 other sources, including “missing,” “do not know,” and “other/specify.”

Difference compared with respondents aged 14 to 18 years.

Difference compared with children aged 6 to 10 years.

P<0.05.

P<0.01.

P<0.001.

By eating occasion, 39% of sodium intake occurred at dinner, 31% at lunch, 16% from snacks, and 14% at breakfast for US children aged 6 to 18 years (Table 5 [available online at www.andjrnl.org]). On average, across the year, weekends, weekdays, and holidays, 45% of the sodium consumed at lunch came from foods obtained at the store, 26% from school cafeteria foods, and 14% from fast-food/pizza restaurants. Among US children aged 6 to 10 years, 33% of sodium consumed at lunch came from school cafeteria foods and 7% from fast-food/pizza restaurants. In contrast, among children aged 14 to 18 years, 19% of sodium consumed at lunch came from school cafeteria foods and 19% from fast-food/pizza restaurant foods (data not shown).

Table 5.

Population proportiona of total sodium intake consumed from each eating occasionb and place obtainedc for all children aged 6 to 18 years and by age group: What We Eat in America, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, US children, 2011–2012

| Age group (y) | Place obtained | Eating Occasion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | Snack | ||

| ← %±standard error → | |||||

| 6–18 (N=2,142) | |||||

| All sources | 14.3±0.6 | 31.1±0.9 | 38.8±1.0 | 15.8±0.9 | |

| Store | 10.6±0.5 | 13.9±1.1 | 22.0±0.9 | 11.8±0.7 | |

| Restaurant fast food/pizza | 1.0±0.2 | 4.3±0.4 | 9.1±1.1 | 1.3±0.2 | |

| Restaurant waiter/waitress | —d | 2.2±0.4 | 4.2±0.7 | — | |

| School cafeteria | 1.5±0.3 | 8.2±1.1 | — | — | |

| Other | — | 2.6±0.5 | 3.6±0.4 | 2.4±0.3 | |

| 6–10 (n=958) | |||||

| All sources | 15.8±0.9 | 31.2±1.2 | 36.6±1.1 | 16.4±0.8 | |

| Store | 11.6±0.8 | 14.2±2.0 | 22.7±1.3 | 12.4±0.8 | |

| Restaurant fast food/pizza | 0.7±0.2 | 2.2±0.3 | 7.7±1.3 | — | |

| Restaurant waiter/waitress | — | 1.2±0.3 | 3.6±1.1 | — | |

| School cafeteria | 2.1±0.4 | 10.4±1.3 | — | — | |

| Other | — | — | 2.6±0.4 | 2.5±0.2 | |

| 11–13 (n=488) | |||||

| All sources | 12.5±1.1 | 30.8±1.7 | 39.6±1.6 | 17.1±1.3 | |

| Store | 10.2±1.0 | 15.1±2.1 | 23.5±2.0 | 12.9±1.0 | |

| Restaurant fast food/pizza | — | — | 8.3±1.5 | — | |

| Restaurant waiter/waitress | — | — | 3.7±1.0 | — | |

| School cafeteria | — | 7.9±1.4 | — | — | |

| Other | 0.8±0.2 | 2.4±0.7 | 4.1±0.9 | 3.0±0.6 | |

| 14–18 (n=696) | |||||

| All sources | 13.8±0.8 | 31.3±1.4 | 40.4±1.7 | 14.5±1.4 | |

| Store | 9.9±0.8 | 12.9±1.3 | 20.4±1.5 | 10.7±1.3 | |

| Restaurant fast food/pizza | 1.6±0.4 | 6.1±0.7 | 10.7±2.1 | 1.8±0.3 | |

| Restaurant waiter/waitress | — | 3.9±0.8 | 5.0±1.2 | — | |

| School cafeteria | — | 6.2±1.6 | — | — | |

| Other | — | 2.1±0.5 | 4.3±0.9 | 1.9±0.3 | |

The proportion (%) of sodium consumed is defined as the sum of the amount of sodium consumed from each specific food category for all participants divided by the sum of sodium consumed from all food categories for all participants multiplied by 100. All estimates use 24-hour dietary recall, take into account the complex sampling design, and use dietary Day 1 sample weights to account for nonresponse and weekend/weekday recalls.

Eating occasions were defined by the participant. Responses were categorized as follows: breakfast was defined as “breakfast,” “desayuno,” or “almuerzo”; lunch was defined as “brunch,” “lunch,” or “comida”; dinner was defined as “dinner,” “supper,” or “cena”; snack as “snack,” “drink,” “extended consumption (items that were consumed over a long period of time), “merienda,” “entre comidas,” “botana,” “bocadillo,” “tentempie,” or “bebida.”

Place obtained was analyzed from responses to the questions, “Where did you get this (most of the ingredients for this) [food name]?” Sources other than those shown were combined under “other” and included “from someone else/gift”, and 19 other sources, including “missing,” “do not know,” and “other/specify.”

Data are statistically unreliable, relative standard error ≥30%.

DISCUSSION

Average daily sodium intake among US school-aged children during 2011–2012 exceeded recommendations, regardless of demographic or body mass index subgroup, and was primarily related to consumption of a sodium-dense diet. On average school-aged children consumed 1.6 to 1.7 mg/kcal, much higher than the 1.0 mg/kcal proposed from food patterning analyses to achieve recommendations.22 Average sodium intake among US high school–aged children was about 400 to 500 mg higher than younger school-aged children and comparable to US adults (about 3,600 mg).23 Nearly half of sodium consumed was contributed by 10 types of foods, with the top contributors being pizza, followed by Mexican mixed dishes, but with variation in the ranking of the top 10 food contributors by race or ethnic group. Contributions from food sources to total sodium intake changed from 2009–2010, with less food obtained from stores (58% during 2011–2012 vs 65% during 2009–2010; t test P=0.002) and more from fast-food/pizza restaurants (20.3% during 2011–2012 vs 15.5% during 2009–2010; t test P=0.086) or restaurants with wait staff (9.2% during 2011–2012 vs 5.2% during 2009–2010; t test P=0.012).1 The increased consumption of restaurant foods may also explain the more sodium-dense diets consumed by older children as the intake of different types of foods and the amounts of sodium in the same type of food may vary by location.24 Because food preferences are shaped by early food experiences, sodium reduction strategies in young populations may have important implications for future sodium intake.7

For the first time, separate estimates were included for non-Hispanic Asian children.15 They consumed, on average, the most sodium per calorie of any race/ethnic group examined; however, they also consumed fewer calories on average and their overall sodium intake did not differ. A potential explanation for this difference is the higher consumption of lower calorie, sodium-dense foods like soup, which was the second highest contributor to sodium intake among this group, compared with the fifth or lower contributor among other race/ethnic groups. Our data support a previous study, which suggests that there are no differences in sodium intake between Korean Americans and non-Hispanic whites or non-Hispanic blacks.25 However, other studies indicate children in some Asian subgroups may consume more sodium, on average, than non-Hispanic whites and that the diets of Asian Americans may be composed of both traditional Asian foods and components of a Western diet.26,27 Recent data also suggest Asian subgroups may differ in their hypertension risks.28,29 South Asians in the United States are reported to have higher rates of hypertension, and individuals of Japanese descent more frequently carry salt-sensitive genes associated with hypertension.29,30 As the fastest growing race/ethnic group in the United States,14 monitoring foods contributing to sodium intake in this group will help determine whether different or additional foods, beyond those consumed by the general population, need to be targeted for reformulation.

Differences from 2009–2010 in the top food categories and places contributing to sodium intake among US school-aged children1 could be explained by changes in consumption of foods or major changes in food codes and categorization. Household food-away-from-home expenditures have increased over the past 3 decades, whereas time spent in food preparation at home has decreased, which may explain some of the decline in sodium intake from foods obtained from stores.31,32 Children’s energy intake from fast-food restaurants specializing in burgers, pizza, or chicken has been decreasing in comparison to energy intake from Mexican cuisine, and sales data show that Mexican restaurants are among the fastest growing segment of fast-casual restaurants and growing substantially more than other fast-food competitors, potentially explaining the high contribution of these foods to sodium intake.33,34 However, the high contribution of Mexican mixed dishes to children’s sodium intake also could be related to a greater proportion of these foods captured with new food codes. Between FNDDS 2009–2010 and 2011–2012, more than 1,100 new food codes were added to different food categories, allowing for easier coding and analysis of their contribution to intake; for example, Mexican mixed dishes that were previously separated into components such as beans, rice, and cheese.

Several potential limitations exist in our analysis. First, dietary recall data may be subject to reporting error (where misreporting of intake may be particularly prevalent among children and adolescents).35 The gold standard for assessing total sodium intake is 24-hour urine sodium excretion, which is not available for children in NHANES, but also does not inform us about the contribution of specific foods or food groups to total sodium intake. Studies among adults comparing total sodium intake assessed from 24-hour sodium excretion and dietary recall methods used in NHANES have been mixed.36,37 Second, for some, but not all foods, a single food code in WWEIA was used to estimate the sodium content of a specific food across a variety of venues, which may not capture reformulation of sodium content in specific foods by setting. For example, pizza has separate codes and corresponding sodium values for “school” (467 mg sodium/ 100 g) and “fast-food restaurant” (742 mg/100 g), but most other foods are not coded separately for school, stores, or fast-food restaurants, and therefore, may not reflect reformulation of foods (eg, in schools). In addition, rice with salt added in cooking was used for coding all rice intakes, although not all consumers or venues necessarily add salt during cooking. In previous studies, rice has not been shown to be a major contributor to sodium intake in Asian diets.38,39 Third, NHANES does not specify whether or not children were attending school on the recall day, which presents a challenge for interpreting data about foods and beverages from school cafeterias. In previous cycles, it was possible to identify leading sources of sodium among a subset of children who were likely consumers of school meals, but because this question was no longer included and school terms and holidays vary, this was not possible with the current data.1 Fourth, estimates of total sodium intake exclude salt added at the table, which is estimated to account for about 6% of sodium intake among adults.16,40

The data in this report underscore the importance of national sodium reduction efforts, including targets for school meals13 and competitive foods (ie, foods and beverages sold outside of the school meal programs) that were implemented during school year 2014–2015.41 In addition, sodium reduction efforts are underway in multiple sectors. The Kids Live-Well program requires participating restaurants to offer healthful meal items for children, including a focus on increasing consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and decreasing consumption of added sugars and sodium.42 Several companies have been making gradual reductions in the sodium content of their foods43 and recently, the Food and Drug Administration issued draft guidance with proposed voluntary sodium reduction targets for the food industry.44 The current analysis emphasizes the ubiquity of sodium in the US food supply, highlighting the influence the food industry can have on lowering the sodium density of US diets by participating in the sodium reduction initiatives proposed by the Food and Drug Administration and other bodies.

Despite some controversy regarding population sodium reduction efforts in the United States,45,46 groups such as the American Heart Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans reviewed the science and continue to support strategies to encourage a healthy diet, including lower sodium intake, among children and adolescents.8,10,47,48 Reducing the sodium content of commonly consumed commercially processed, store, school, and restaurant foods could result in substantial reductions in excess sodium intake among US children now and into their adult years. Sodium reduction is an important strategy to reduce high blood pressure and help prevent cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in the United States.49

CONCLUSIONS

Average sodium intake among US school-aged children during 2011–2012 remained high, was related to consumption of sodium-dense foods, and was not attributable to one type of food, source of food, or eating occasion. The results support the need to reduce sodium content across the US food supply rather than in a single type of food or venue. These data provide baseline information on sources of sodium intake among US school-aged children before implementation of key national sodium reduction strategies. In NHANES and national school-based surveys, such as the School Nutrition Dietary Assessment50 and the forthcoming School Nutrition and Meal Cost Study,51 up-to-date nutrient data based on current laboratory and/or label analysis will aid in understanding reformulations by location (eg, foods obtained from school cafeterias vs restaurants) and for accurate evaluation of the influence of national strategies for sodium reduction among US school-aged children. Along with up-to-date nutrient databases, examining the validity of 24-hour dietary recalls to assess sodium intake among children could improve monitoring and support sodium reduction efforts.

PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS.

What Is the Current Knowledge on this Topic?

Sodium intake in children and adolescents exceeds recommendations and comes from a variety of sources. What children eat at an early age can determine later dietary intake.

How Does this Research Add to Knowledge on this Topic?

This is the most current data on dietary sources of sodium among US children and adolescents and reports on new data for non-Hispanic Asian children. Sodium intake remains high and is related to consumption of sodium dense foods from multiple sources and occasions.

How Might this Knowledge Influence Current Dietetics Practice?

Knowledge of the major sources of sodium among children can help registered dietitian nutritionists counsel parents and caregivers about effective sodium reduction strategies, such as checking Nutrition Facts labels and choosing lower sodium foods.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING/SUPPORT

This project was supported by an appointment to the Research Participation Program for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an agreement between the Department of Energy and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Supplementary materials: The Figure, Table 3, and Table 5 are available at www.andjrnl.org. Podcast available at www.andjrnl.org/content/podcast.

STATEMENT OF POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the US Department of Agriculture.

References

- 1.Cogswell ME, Yuan K, Gunn JP, et al. Vital signs: Sodium intake among U.S. school-aged children, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(36):789–797. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kit BK, Kuklina E, Carroll MD, Ostchega Y, Freedman DS, Ogden CL. Prevalence of and trends in dyslipidemia and blood pressure among US children and adolescents, 1999–2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(3):272–279. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X, Wang Y. Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Circulation. 2008;117(25):3171–3180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toschke AM, Kohl L, Mansmann U, von Kries R. Meta-analysis of blood pressure tracking from childhood to adulthood and implications for the design of intervention trials. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99(1):24–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aburto NJ, Ziolkovska A, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP, Meerpohl JJ. Effect of lower sodium intake on health: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2013;346:f1346. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. [Accessed June 21, 2016];Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/. Published February 2015.

- 7.Mennella JA. Ontogeny of taste preferences: basic biology and implications for health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(suppl 3):704S–711S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.067694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Departments of Health and Human Services and Agriculture. [Accessed June 21, 2016];2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/. Published December 2015.

- 9.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeland-Graves JH, Nitzke S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Total diet approach to healthy eating. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(2):307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Council on School Health, Committee on Nutrition, American Academy of Pediatrics. Snacks, sweetened beverages, added sugars, and schools. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):575–583. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2960–2984. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. [Accessed June 21, 2016];Nutrition standards in the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Program: Final rule. 7 CFR Parts 210 and 220. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2012-01-26/pdf/2012-1010.pdf. Published January 26, 2012.

- 14.Hoeffel EMRS, Kim MO, Shahid H. [Accessed June 21, 2016];The Asian population. 2010 http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf?cssp=SERP. Published March 2012.

- 15.Johnson CL, Dohrmann SM, Burt VL, Mohadjer LK National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed June 21, 2016];National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Sample design, 2011–2014. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_162.pdf. Published March 2014. [PubMed]

- 16.Mattes RD, Donnelly D. Relative contributions of dietary sodium sources. J Am Coll Nutr. 1991;10(4):383–393. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1991.10718167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. [Accessed June 21, 2016];FNDDS documentation and databases. http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=12068. Updated August 20, 2015.

- 18.US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. [Accessed June 21, 2016];What We Eat in America. http://www.ars.usda.gov/News/docs.htm?docid=13793. Updated October 2, 2014.

- 19.US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. WWEIA food categories. [Accessed June 21, 2016];What We Eat in America dietary methods research. http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=23429. Updated May 15, 2015.

- 20.Krebs Smith SM, Kott PS, Guenther PM. Mean proportion and population proportion: Two answers to the same question? J Am Diet Assoc. 1989;89(5):671–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.SAS-callable SUDAAN Statistical Software, version 11. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guenther P, Lyon JMG, Appel L. Modeling dietary patterns to assess sodium recommendations for nutrient adequacy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(4):842–847. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.047779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Nutrient intakes: From food and beverages. [Accessed June 21, 2016];What We Eat in America data tables, 2011–2012. http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/80400530/pdf/1112/Table_1_NIN_GEN_11.pdf. Updated February 11, 2015.

- 24.Ahuja JKC, Wasswa-Kintu S, Haytowitz D, Daniel M, Thomas R, Showell B, et al. Sodium content of popular commercially processed and restaurant foods in the United States. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:962–967. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim MJ, Lee SJ, Ahn YH, Bowen P, Lee H. Nutrient profiles of Korean-Americans, non-Hispanic whites and blacks with and without hypertension in the United States. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2008;2(3):141–149. doi: 10.1016/S1976-1317(08)60037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diep CS, Foster MJ, McKyer EL, Goodson P, Guidry JJ, Liew J. What are Asian-American youth consuming? A systematic literature review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(2):591–604. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9905-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park SY, Paik HY, Skinner JD, Spindler AA, Park HR. Nutrient intake of Korean-American, Korean, and American adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(2):242–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nwankwo YS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2012. [Accessed June 21, 2016];NCHS data brief, no. 133. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db220.htm. Published October 2013. [PubMed]

- 29.Watson RE, Karnchanasorn R, Gossain VV. Hypertension in Asian/ Pacific Island Americans. J Clin Hypertens. 2009;11(3):148–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yi SS, Thorpe LE, Zanowiak JM, Trinh-Shevrin C, Islam NS. Clinical characteristics and lifestyle behaviors in a population-based sample of Chinese and South Asian Immigrants with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29(8):941–947. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpw014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Food-away-from-home. [Accessed June 21, 2016];Food consumption & demand. http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-choices-health/food-consumption-demand/food-away-from-home.aspx. Updated October 29, 2014.

- 32.Smith LP, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Trends in US home food preparation and consumption: Analysis of national nutrition surveys and time use studies from 1965–1966 to 2007–2008. Nutr J. 2013;12:e45. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rehm CD, Drewnowski A. Trends in energy intakes by type of fast food restaurant among US children from 2003 to 2010. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):502–504. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong V. [Accessed June 21, 2016];For American restaurant chains, the future is Mexican. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-10-28/for-american-restaurant-chains-the-future-is-mexican.

- 35.Murakami K, Livingstone MBE. Prevalence and characteristics of misreporting of energy intake in US children and adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2012. Br J Nutr. 2016;115(2):294–304. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515004304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mercado C, Cogswell M, Valderrama A, et al. Difference between 24-h diet recall and urine excretion for assessing population sodium and potassium intake in adults aged 18–39 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(2):376–386. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.081604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freedman L, Commins J, Moler J, et al. Pooled results from 5 validation studies of dietary self-report instruments using recovery biomarkers for potassium and sodium intake. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(7):473–487. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asakura K, Uechi K, Masayasu S, Sasaki S. Sodium sources in the Japanese diet: Difference between generations and sexes. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(11):2011–2023. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015003249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson CA, Appel LJ, Okuda N, et al. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: The INTERMAP study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(5):736–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Institute of Medicine. Sodium Intake in Populations: Assessment of Evidence. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. [Accessed June 21, 2016];National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program: Nutrition standards for all foods sold in school as required by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010; interim final rule. 7 CFR Parts 220 and 220. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-06-28/pdf/2013-15249.pdf. Published June 28, 2013.

- 42.National Restaurant Association. Kids LiveWell Program. [Accessed June 21, 2016];Food and healthy living. http://www.restaurant.org/Industry-Impact/Food-Healthy-Living/Kids-LiveWell-Program.

- 43.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. National Salt Reduction Initiative. [Accessed June 21, 2016];Sodium Initiative webpage. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/health-topics/national-salt-reduction-initiative.page.

- 44.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed June 21, 2016];Draft guidance for industry: Voluntary sodium reduction goals: Target mean and upper bound concentrations for sodium in commercially processed, packaged, and prepared foods. http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/ucm494732.htm. Updated June 10, 2016.

- 45.Anderson CAM, Johnson R, Kris Etherton P, Miller E. Commentary on making sense of the science of sodium. Nutr Today. 2015;50(2):66–71. doi: 10.1097/NT.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cogswell ME, Mugavero K, Bowman BA, Frieden TR. Dietary sodium and cardiovascular disease risk—Measurement matters. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(6):580–586. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1607161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LL, et al. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: A guide for practitioners. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):544–559. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogata BN, Hayes D. Position of The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Nutrition guidance for healthy children ages 2 to 11 years. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(1):1257–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–e322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. [Accessed June 21, 2016];School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study-IV. http://www.fns.usda.gov/school-nutrition-dietary-assessment-study-iv. Updated September 5, 2013.

- 51.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. [Accessed May 1, 2016];Food and Nutrition Service research and evaluation plan—Fiscal year. 2012 http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2012RandE_0.pdf. Published February 9, 2012.