INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common condition affecting both children and adults, with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 5% in children, and 10% to 30% in adults.1 It is characterized by recurrent obstruction in the upper airway during sleep, leading to arousals with fragmented sleep and intermittent hypoxemia, which can result in deleterious health effects, including neurocognitive problems and cardiovascular morbidity. Consequently, patients with untreated OSA present an increased use of health care resources, high socioeconomic costs, and increased overall mortality from all causes.2

In the past, the standard of care established by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) was to diagnose OSA with in-laboratory polysomnography (PSG). PSG is accurate with a low failure rate because the study is attended by technical staff; however, it is considered relatively expensive and technically complex. Furthermore, access to in-laboratory sleep testing is limited because the prevalence and awareness of sleep disorders has grown in the past few decades. In preselected individuals, portable testing (PT) has been used as an alternative diagnostic test for OSA based in part on the premise that it is theoretically less expensive and quicker to deploy compared with in-laboratory PSG.3 Portable sleep testing also alleviates the previously noted access issues by cutting back on the long wait times typically seen with in-laboratory testing.

CURRENT GUIDELINES FOR PORTABLE SLEEP TESTING

In 2007, the AASM appointed the Portable Monitoring Task Force to develop clinical guidelines for the use of PT in the diagnosis and management of OSA. The key features of the guidelines are as follows3:

-

PT may be used as an alternative to PSG for the diagnosis of OSA in patients

With a high pretest probability of moderate-to-severe OSA

For whom in-laboratory PSG is not possible due to immobility or critical illness.

-

PT is not appropriate for the diagnosis of OSA in patients

With significant comorbid medical conditions such as advanced cardiopulmonary disease that may degrade its accuracy

With evaluation showing suspected of having comorbid sleep disorders

With screening of belonging to an asymptomatic population.

At a minimum, PT must record air flow, respiratory effort, and pulse oximetry.

PT application, education, testing, scoring, and interpretation must be performed under an AASM-accredited comprehensive sleep medicine program.

A negative or technically inadequate PT in patients with a high pretest probability of moderate-to-severe OSA should prompt in-laboratory PSG

PORTABLE MONITORING CLASSIFICATION SCHEME

The first widely used classification system for describing sleep testing devices was published by the AASM in 1994.4 It placed available devices into 4 levels based on the number and type of leads used. Table 1 provides details about this classification. It is important to note that level 3 and level 4 devices do not record signals to determine sleep staging or disruption.

Table 1.

Portable studies for sleep apnea evaluation: classification scheme (6-hour overnight recording minimum)

| Level 1: Standard PSG | Level 2: Comprehensive Portable PSG | Level 3: Modified Portable Apnea Testing | Level 4: Continuous Single or Dual Parameter Recording | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Minimum of 7: EEG, EOG, chin EMG, ECG, airflow, respiratory effort, oximetry | Minimum of 7: EEG, EOG, chin EMG, ECG or HR, airflow, respiratory effort, oximetry | Minimum of 4: ventilation (respiratory movement and airflow) HR or ECG, oximetry | Minimum of 1 (typically oximetry or airflow) |

| Body position | Documented or objectively measured | Can be objectively measured | Can be objectively measured | Not measured |

| Leg movement | EMG or motion sensor (optional) | EMG or motion sensor (optional) | May be recorded | Not recorded |

| Personnel attendance | Constant | None | None | None |

| Interventions Possible | Yes | No | No | No |

Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; EEG, electroencephalogram; EMG, electromyogram; EOG, electrooculogram; HR, heart rate.

From Ferber R, Millman R, Coppola M, et al. Portable recording in the assessment of obstructive sleep apnea. ASDA standards of practice. Sleep 1994;17(4):378–92.

However, with continued technological advances, many PT devices did not fit into these categories. Clinicians needed guidance to help decide which out-of-center (OOC) testing devices are appropriate for diagnosing OSA. In 2011, a new categorization scheme was developed, allowing easy classification of OOC devices based on the types of sensors that they use to aid in the diagnosis of OSA, including sleep, cardiac, oximetry, position, effort, and respiratory measures (SCOPER).5 Table 2 provides details about the new classification system for PT.

Table 2.

Sleep, cardiac, oximetry, position, effort, and respiratory measures (SCOPER) categorization

| Sleep | Cardiovascular | Oximetry | Position | Effort | Respiratory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1: 3 EEG channels, EOG, and chin EMG | C1: >1 ECG lead, can derive events | O1: Finger or ear oximetry with recommended sampling | P1: Video or visual measurement | E1: 2 RIP belts | R1: Nasal pressure and thermal device |

| S2: <3 EEG channels or without EOG or chin EMG | C2: PAT | O2: Finger or ear oximetry, without sampling | P2: Nonvisual position measurement | E2: 1 RIP belt | R2: Nasal pressure |

| S3: sleep surrogate (actigraphy) | C3: 1 lead ECG | O3: Oximetry, alternative site | E3: Derived effort | R3: Thermal device | |

| S4: Other sleep measure | C4: Derived pulse (from oximetry) | O4: Other oximetry | E4: Other effort measure | R4: ETCO2 |

3 EEG channels defined as frontal, central, and occipital.

Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiography; EEG, electroencephalography; EMG, electromyography; EOG, electrooculog-raphy; ETCO2, end-tidal CO2; PAT, peripheral arterial tone; RIP, respiratory inductance plethysmography.

From Collop NA, Tracy SL, Kapur V, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea devices for out-of-center (OOC) testing: technology evaluation. J Clin Sleep Med 2011;7(5):531–48.

OUTPATIENT VALIDATION FOR PORTABLE TESTING

There have been several trials validating the outpatient use of portable sleep tests in patients with a high pretest probability of OSA. Summarizing the evidence that PT is a reasonable substitute for in-laboratory PSG, a 2014 Cochrane meta-analysis of comparative studies to evaluate the accuracy of level 3 versus level 1 sleep tests in adults with suspected OSA confirmed that level 3 portable devices showed good diagnostic performance compared with level 1 sleep tests in adult patients with a high pretest probability of moderate-to-severe OSA.6

Several studies have found home diagnosis and treatment algorithms for OSA to be noninferior to traditional, attended, in-laboratory PSG studies. The protocol entails undergoing PT followed by autotitrating continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment.

A prospective, noninferiority, randomized trial published in 20117 showed that the home testing pathway was noninferior to the in-laboratory pathway in terms of CPAP adherence at 3 months, functional outcomes of sleepiness, and sleep-related quality of life.

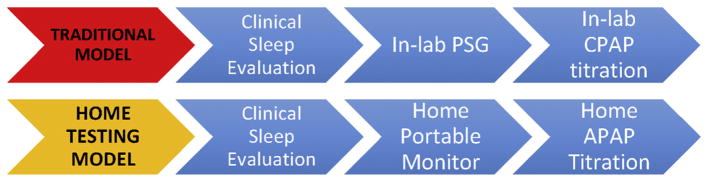

Two major studies comparing outpatient initiation and titration of autotitrating PAP (APAP) versus in-laboratory CPAP titration showed that APAP-treated patients have a similar adherence to treatment compared with in-laboratory CPAP titration.8,9 In the first study,8 results showed that a home-based strategy for diagnosis and treatment OSA compared with a traditional, in-laboratory PSG was noninferior in terms of acceptance, treatment adherence, and functional outcomes. Additionally, CPAP adherence was higher at 3 months in the home testing and home titration group. Fig. 1 provides contrasting information on the 2 models for sleep apnea diagnosis pathways.

Fig. 1.

Traditional in-laboratory and home PT pathways for the diagnosis of OSA, based on 90th percentile APAP pressure. (Adapted from Cooksey JA, Balachandran JS. Portable monitoring for thediagnosis of OSA. Chest 2016;149:1074–81.)

Another study published in 20129 found that APAP-treated patients (compared with in-laboratory CPAP titration) had higher satisfaction with therapy, with no difference in positive airway pressure (PAP) adherence, residual apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), or functional outcomes. It is, however, important to highlight that an important feature of these trials was the degree of early and close follow-up provided to subjects after PAP initiation. Early, close follow-up in the diagnosis and treatment of OSA has been established to improve adherence.10

LIMITATIONS OF PORTABLE TESTING

Despite that portable monitoring studies and in-laboratory PSG have equivalent functional outcomes, they are not suitable for certain patient populations. Because most trials validating home sleep testing for OSA diagnosis excluded patients with comorbidities, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and congestive heart failure, data regarding the use of home testing in patients with these medical comorbidities are limited.10 No clear guidelines exist on using PT in patients with class 3 obesity (body mass index > 40) or elderly patients.

Therefore, in patients with significant medical comorbidities in high-risk populations (those with severe cardiovascular, pulmonary, or neuromuscular disease), concomitant sleep disorders despite effective PAP therapy, and a high pretest probability of OSA but negative portable study, there is a continuing role for in-laboratory PSG within the home testing algorithms (Fig. 2).10

Fig. 2.

Suggested algorithm for PT and indications for in-laboratory PSG versus PT. PT can be considered in patients with a high pretest probability of OSA; however, a normal study or technical failure must prompt an in-laboratory PSG. Patients with a low pretest probability for OSA, suspicion for comorbid sleep disorders, and severe comorbidities are not good candidates for PT, and must undergo monitored, in-laboratory PSG for evaluation of OSA.

DIRECT AND INDIRECT COSTS OF UNTREATED OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA

Studies have shown that health care utilization and related costs are far higher for individuals with OSA compared with those without OSA. Although these costs are primarily due to OSA-related cardiovascular morbidities, this effect on cost may be independent of chronic disease burden. This is evidenced by the relationship between medical costs and OSA severity shifting from a linear relationship in mild-to-moderate OSA to a ceiling effect in severe OSA.11 A United States cross-sectional study from 1999 the found that untreated OSA may be responsible for up to $3.4 billion in additional medical costs (an average annual cost of $2720).12

Indirect costs pertain to losses in productivity and income as a consequence of disability related to the disease. In a Danish study comparing adults with OSA to healthy controls, untreated OSA was associated with higher direct and indirect costs, including significantly higher rates of health-related contact, medication use, and unemployment.13 Additionally, employed adults with OSA had earnings (on average) one-third lower than their non-OSA counterparts, even after adjusting for the socioeconomic status of both cohorts.11 This important study found a substantial association between OSA and socioeconomic costs and consequences for the individual patient and society.

THE TRANSITION FROM POLYSOMNOGRAPHY TO PORTABLE SLEEP TESTING

Given the socioeconomic impacts and costs of untreated OSA, an important challenge for the clinician is understanding both the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the available diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Although in-laboratory PSG is the gold standard for diagnosis, it is often expensive, time-consuming, and frequently of limited availability. PT is now a part of routine care and an attractive alternative to diagnosing OSA in selected individuals.11 Additionally, there are several socioeconomic advantages to PT, mainly related to its lower direct cost, increased accessibility, and convenience of testing for patients suspected to have OSA, resulting in an overall improvement of the diagnostic process. As the recognition and prevalence of OSA has increased, so has the demand for PT. In a recent 2013 survey of sleep centers, 64% of centers reported that they are offering PT for privately insured patients and 48% reported they were reducing their plans for expansion of laboratory beds as a result of home testing.14

Costs of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies

The direct costs associated with different diagnostic and management strategies for OSA were published by the New England Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council in 2013.15 Cost-effectiveness was evaluated in a hypothetical cohort of 1000 Medicaid patients older than 16 years with suspected OSA. The comparator for all strategies was in-laboratory PSG. Outcomes evaluated included total cost, number of individuals diagnosed with OSA, number of false-negative results, and number of averted in-laboratory PSGs. Three distinct strategies were compared with PSG alone and conducted in all 1000 subjects, including screening with a symptom questionnaire plus PSG; morphometric examination plus PSG; and PT, in which patients were diagnosed based on PT findings alone and did not receive confirmatory PSG. Results showed that PT was the most cost-saving of all strategies, mainly driven by lower test costs in comparison with PSG alone (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outcomes and costs of different diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for obstructive sleep apnea among 1000 hypothetical Medicaid patients referred for testing and treated for 1 year if positive

| Measure | Diagnostic Strategies | Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies Test-and-Treat | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSG (gold standard) | Type 3 monitor alone (PT) | PSG + fixed titration CPAP (gold standard) | Home monitor (PT) + autotitrating CPAP | Home monitor (PT): followed by split-night PSG, fixed titration CPAP if PT positive | |

| Total cost ($) | 652,830 | 200,700 | 1,244,905 | 811,129 | 1,112,731 |

| Cost difference of PT vs PSG alone ($) | N/A | 452,130 | — | — | — |

| Cost differences of PT + APAP vs sleep laboratory strategy ($) | — | — | N/A | 433,776 | 132,174 |

All numbers are for 1000 patients at high risk of OSA diagnosis. For the diagnostic testing, the cost-savings for the diagnosis of OSA using PTwas $452,130 compared with PSG. For the test-and-treat strategies, cost savings for PT followed by auto-PAP compared with in-laboratory split-night PSG followed by CPAP titration was $433,776.

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

From The New England Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council. Diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. 2013. Available at: https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Final-Report_January20132.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2016.

For the evaluation of the cost of diagnostic testing and CPAP titration, 3 test-and-treat strategies were analyzed, including (1) PT followed by autotitrating CPAP, (2) PT followed by split-night PSG for those who tested-positive with PT, and (3) these compared with the gold standard of in-laboratory PSG plus in-laboratory titration CPAP for all patients. Results showed that both PT plus autotitrating CPAP strategies were cost-saving relative to in-laboratory PSG plus CPAP titration, with the most substantial cost savings (more than $400,000) gained from the home testing plus autotitrating CPAP strategy (see Table 3).15

Cost-Effectiveness of Polysomnography Versus Other Diagnostic Strategies

Although a PT may individually be less resource intensive than PSG with lower direct costs, clinical guidelines recommend that a diagnostic PSG be performed in patients with a high pretest probability of OSA who have a negative result on PT. This is due to concerns that PT may have lower sensitivity for diagnosing mild-to-moderate OSA. Thus, the PT strategy as a whole may not be cost-effective.14

Although comparing direct costs is informative, assessing the cost-effectiveness of various management strategies may be more revealing. Cost-effectiveness is assessed by the ratio of the incremental cost and change in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) following the adoption of a treatment compared with no treatment.16 This takes into account both added years of life by therapy and improvement in quality of life. An incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of less than $50,000 per QALY is often quoted as the threshold of cost-effectiveness.17

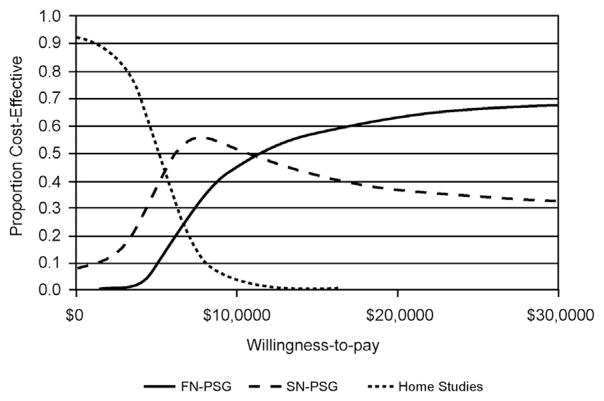

In 2006, one of the first analyses used 3 strategies: PT, split-night in-laboratory PSG (PSG followed by CPAP titration during the same night), and full-night in-laboratory PSG (a night of PSA followed by another night of CPAP titration) to compare their cost-effectiveness from a third-party payer perspective over a 5-year period.18 Cost analysis was performed from the perspective of third-party payers and only direct health care costs were included in the analysis. Effectiveness was measured as QALYs, and costs were adjusted for variable CPAP compliance and dropouts. The study showed that PT was the most cost-effective alternative to split-night PSG and to full-night PSG but only at the lowest amounts of third-party willingness-to-pay. On the other hand, split-night PSG or full-night PSG were most cost-effective at higher amounts of third-party willingness-to-pay (Fig. 3). Therefore, third-party willingness-to-pay is an important consideration in choosing the most cost-effective approach.

Fig. 3.

Cost-effectiveness as influenced by third-party willingness-to-pay in 3 diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for OSA. Acceptability curves show the 3 pathways when the cost-effectiveness ratios are transformed to net benefits. Each curve represents the proportion of evaluations that are cost-effective for each pathway over a range of willingness-to-pay thresholds. Home studies is the pathway most frequently cost-effective when willingness-to-pay is less than $6500, as is split-night PSG when willingness-to-pay is between $6500 and $11,500, and full-night PSG willingness-to-pay is greater than $11,500. FN-PSG, full-night PSG; SN-PSG, split-night PSG. (From Deutsch PA, Simmons MS, Wallace JM. Cost-effectiveness of split-night polysomnography and home studies in the evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med 2006;2(2):145–53.)

Another study, published in 2011, was conducted to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of PT, split-night PSG, and full-night PSG in conjunction with CPAP therapy in subjects with moderate-to-severe OSA.19 The study linked health-related quality of life to relevant outcomes observed in OSA by evaluating the impact of treatment on common negative outcomes associated with untreated OSA, including strokes, myocardial infarctions, and motor vehicle collisions (MVCs) due to excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS). Cost-effectiveness (assessed through incremental cost per QALY gained) of different diagnostic and therapeutic strategies were compared over a 10-year period and over the expected lifetime of a subjects, using a base-case of a 50-year-old man with a 50% pretest probability of OSA. Surprisingly, the results showed that full-night PSG was the preferred diagnostic strategy and the most cost-effective at any willingness-to-pay, owing to its superior diagnostic accuracy. In other words, PSG, although a more expensive test up front, ends up costing the health care system less over time by minimizing the number of patients with false-positive and negative tests, and results in more health benefits compared with PT. However, after closely examining the underlying assumptions of the model used in the study, a few things must be considered. The investigators’ assumption that OSA treatment would dramatically reduce the risk of cardiovascular events (from 56% to 39%) with CPAP was extrapolated from observational studies rather than randomized controlled trials. This increases the economic impact of false-negative results in subjects in the PT arm. Additionally, it was assumed that subjects incorrectly diagnosed with OSA versus PT would use CPAP long-term, magnifying the economic impact of false-positive PT. Lastly, it was assumed that 22% of subjects with a negative PT or technical failure would not return for a follow-up PSG, again increasing the economic impact of a false-negative test. As pointed out by the investigators, when it is assumed that all negative PTs will have a full PSG, and subjects with false-positive PTs who receive no benefit from CPAP are unlikely to use it long-term, PTs were more cost-effective compared with PSG.17

In contrast to this study, a more recent economic analysis of PT versus in-laboratory PSG for the diagnosis and management of OSA used data from the HomePAP study8 (a randomized controlled trial that compared PT vs in-laboratory PSG for the diagnosis and management of OSA), with results analyzed in the context of both payer and provider perspective.14 Results showed that, from the insurance-payer perspective, a home-based diagnostic pathway for OSA with adequate patient treatment was less costly, even after accounting for false-negative and technically inadequate PTs that prompted an in-laboratory PSG. For providers, there were no cost-savings for a PT approach and it even resulted in a negative operating margin.

Bottom Line: Is Polysomnography Cost-Effective?

Taken together, it can be concluded that in comparing direct costs associated with different diagnostic and management strategies for OSA, PT is the most cost-saving of all strategies, mainly driven by lower test costs in comparison with PSG. Additionally, a home testing plus autotitrating CPAP strategy has substantial cost savings compared with split-night PSG plus fixed CPAP titration and in-laboratory PSG with CPAP titration.

However, when taking into account cost-effectiveness of PT as defined by added years of life by therapy and improvement in quality of life (QALY), the economic models becomes more complex and a few things must be taken into consideration, including third-party willingness-to-pay, insurance-payer perspective, and provider perspective. PT seems to be the most cost-effective alternative at the lowest level of third-party willingness-to-pay, whereas split-night PSG or full-night PSG are most cost-effective at higher amounts of third-party willingness-to-pay. From the insurance-payer perspective, PT for the diagnosis of OSA is less costly; however, for providers this may result in a negative operating margin.

SOCIAL COSTS AND RISKS OF OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA

EDS is a common and concerning symptom of OSA with several deep-rooted consequences. EDS is characterized by sleepiness that occurs in situations in which an individual is normally expected to be awake and alert. Up to 87% of adults with OSA may have EDS.20

EDS can impair functioning at both personal and social levels, leading to poor work-place performance, time-management skills, and personal interactions, all of which can be improved with treatment of OSA with CPAP.21,22 A recent study found that individuals with OSA had an increased incidence of work-related absenteeism, lower work-related productivity, and a higher rate of psychological stress.23 Taken together, OSA and EDS secondary to OSA seem to significantly affect daytime functioning and there is growing evidence regarding the repercussions of untreated OSA in terms of work-related productivity and accidents.

MVCs are another potential risk of EDS and impaired concentration in untreated OSA. Two studies, including a systemic review and a meta-analysis, showed that both noncommercial and commercial drivers with untreated sleep apnea are at a statistically significant increased risk of involvement in MVCs.24,25 Notably, 1 of the investigators points out that the elevation in crash rate is comparable to drivers with moderate-to-severe dementia or with blood alcohol levels of 0.05 to 0.7 mg/dL. Successful treatment of sleep apnea improves driver performance with decreased MVC rates to a level comparable with the general population.24

Another recent study confirmed an increased risk of MVC among those with OSA compared with the general population and demonstrated that CPAP used 4 or more hours per night reduced MVC risk.26

Portable Sleep Testing in Commercial Motor Vehicle Operators

OSA has a high prevalence among commercial motor vehicle (CMV) operators and it is known to lead to fatigue and EDS, and to increase the risk of motor vehicle crashes. Unlike the typical setting in a sleep clinic where patients with undiagnosed OSA are actively seeking diagnosis and treatment of their symptoms, most CMV drivers are reluctant to carry a diagnosis of OSA because of its economic and occupational implications.27 Most of those who are identified as high risk for OSA according to Joint Task Force criteria often either do not complete a full in-laboratory PSG due to lack of insurance or they go doctor shopping to seek an alternate commercial driver medical examiner who is not familiar with formal OSA screening recommendations or does not screen for OSA using objective criteria. This can lead to fraudulent certification. Those who undergo PSG are often lost to follow-up and a PSG diagnosis does not necessarily result in adequate treatment in this population. For this reason, there has been a growing demand to identify and develop alternative methods for diagnosing OSA in this high-risk population, such as PT.27

However, given these unique behaviors, diagnosis with PT is likely to be more challenging in this population, producing lower yield than among the general population. Because most PTs do not measure sleep or wake stages, the potential for sabotaging or falsifying the results remain a likely possibility. Although PT studies in the general population maybe more cost-effective than in-laboratory PSGs, CMV operators tested with PT may be more likely to require a follow-up in-laboratory PSG due to data loss and low sensitivity. In addition, some of the strategies being marketed to trucking companies lack sleep specialist involvement, potentially leaving the interpretation of PTs up to primary care providers who may be unaware of the technology’s limitations. This decreases the likelihood that those drivers at high risk of OSA with negative PTs will be referred for a subsequent in-laboratory PSG.27

The only peer-reviewed, published study using PTs to diagnose OSA in the US CMV population used a type IV PT that measures airflow by a nasal cannula and estimates respiratory disturbance index.28 Of those CMV operators who met criteria for high risk of OSA, 68 were randomly selected to use the PT device for 1 night at a certified community sleep center under the supervision of sleep physicians and undergo a subsequent formal PSG in the laboratory. Of those, 16% of drivers using the PTs produced invalid data, 22% were lost to follow-up, and 49% were noncompliant with physician recommendations and, therefore, not able to complete the subsequent PSG. These results predict that incidents of data loss and alteration, as well as loss to follow-up, will likely be higher when they are used on CMV operators in unsupervised home settings or on the road. These factors make it imprudent to directly extrapolate PT efficiency and cost-effectiveness assumptions from the general population to the professional driver population. Further research conducted in the trucking industry is needed to determine the utility of PT in diagnosing OSA among CMV operators.27

Portable Sleep Testing in an Urban Population

The advantages of home-based PT make it an especially attractive health service option for underserved, uninsured urban and rural populations with suspected OSA and limited access to fully equipped sleep laboratories. It is important to study the feasibility of home PT in these populations because home PT has a lower sensitivity and specificity, and is associated with false-negative and positive results, as well as technical failure, and may require follow-up by in-laboratory PSG. This may have a negative impact on cost-effectiveness of PT as a whole and potentially increase the gap in availability of health services for OSA in the urban population. One study examined the feasibility of home PT compared with in-laboratory PSG prospectively in an urban, largely under-served African American population, to determine the accuracy of a validated PT device, compare technical failure rates of home PT in this population, and understand patient preferences with respect to home versus in-laboratory PSG.29 Approximately one-third did not have a high school diploma, more than half were unemployed, and 76% with annual household income less than $50,000. Technical failure rates were 5.3% for home versus 3.1% for in-laboratory PT. There was good agreement between AHI on PSG and AHI on home PT, and participants preferred home over in-laboratory testing. This study confirmed that home PT for diagnosis of OSA in a high-risk urban population is feasible, accurate, and preferred by patients. It is likely to improve access to care, and the cost-effectiveness of this diagnostic strategy for OSA should be examined in underserved urban and rural populations.

THE FUTURE FOR PORTABLE SLEEP TESTING

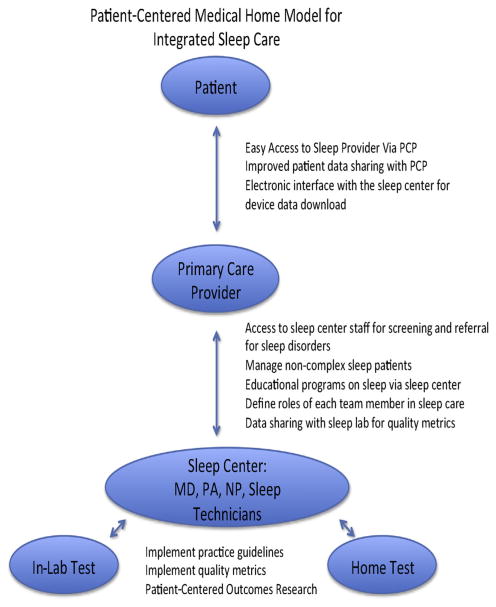

In the current health care delivery model, primary care providers are often not involved with subspecialists in a coordinated process, resulting in fragmented patient care, with increased health-delivery costs. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is gearing toward the patient-centered medical home model, in which primary care physicians (PCPs) are at the heart of health care delivery and provide comprehensive, coordinated care.30

In this rapidly changing health care delivery model, the impact on sleep medicine delivery is substantial. The field has confronted implementation of sizable cuts in reimbursement rates for in-laboratory PSG and, as a result, use of PT has rapidly increased. In response, to comply with insurance company requirements, PCPs often refer patients needing evaluation for OSA for PT via an independent PT company that does not have a comprehensive sleep program. These patients are then prescribed automated treatment devices without appropriate education or access to follow-up with experienced sleep providers, subsequently resulting in poor compliance to treatment, and fragmented care.31,32

For PT to be cost-effective and beneficial within the provisions of the ACA, an integrated and collaborative sleep-care model is essential for meaningful improvements in the quality of sleep disorders care, with early, close follow-up for patients undergoing PT with APAP titration to improve adherence.33 This can be executed via a PCP-based model, providing access to sleep providers and sleep testing, yet encouraging and educating the PCP to screen and treat noncomplex OSA in their own practices (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Algorithm for primary care model of integrated sleep care and portable sleep testing. MD, Medical Doctor; PA, Physician Assistant; NP, Nurse Practitioner.

SUMMARY

This article provides the current state of evidence on the socioeconomic impact of PT for sleep apnea. It seems that both models, the traditional in-laboratory and the newer home-based model for sleep apnea diagnosis, have a place in the current sleep medicine diagnostic algorithm. PT is an appropriate alternative to in-laboratory PSG, as long as the following criteria are carefully considered: (1) it needs to be targeted to the right patients (ie, those who have a high pretest probability of having sleep apnea and do not have coexisting sleep or cardiopulmonary disorders); (2) it needs to have an element of personalized medicine (ie, commercial drivers, urban population), and (3) it should be used as a part of an integrated and collaborative sleep-care delivery model to ensure appropriate follow-up and adherence to treatment. If these criteria are met, PT would be cost-effective in a selected group of patients.

KEY POINTS.

Portable testing (PT) is a reasonable alternative in patients with a high pretest probability of moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

PT should not be routinely ordered in those with coexisting sleep disorders, class 3 obesity, and severe cardiopulmonary disorders.

A negative portable test should prompt an in-laboratory polysomnography.

PT is cost-effective in a selected group of patients, mainly from the insurance-payer perspective, and cost-effectiveness can be enhanced when it is used in collaboration with a sleep center to ensure appropriate follow-up and adherence to treatment.

Further research is needed to determine the utility of PT in diagnosing OSA among commercial motor vehicle operators.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Franklin KA, Lindberg E. Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population—a review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(8):1311. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.06.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiner E, Andreu AL, Sancho-Chust JN, et al. The use of ambulatory strategies for the diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2013;7(3):259–73. doi: 10.1586/ers.13.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collop NA, Anderson WM, Boehlecke B, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(7):737–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferber R, Millman R, Coppola M, et al. Portable recording in the assessment of obstructive sleep apnea. ASDA standards of practice. Sleep. 1994;17(4):378–92. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collop NA, Tracy SL, Kapur V, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea devices for out-of-center (OOC) testing: technology evaluation. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(5):531–48. doi: 10.5664/JCSM.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Shayeb M, Topfer LA, Stafinski T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of level 3 portable sleep tests versus level 1 polysomnography for sleep-disordered breathing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2014;186(1):E25–51. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.130952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuna ST, Gurubhagavatula I, Maislin G, et al. Noninferiority of functional outcome in ambulatory management of obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(9):1238–44. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1770OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosen CL, Auckley D, Benca R, et al. A multisite randomized trial of portable sleep studies and positive airway pressure autotitration versus laboratory-based polysomnography for the diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: the HomePAP study. Sleep. 2012;35(6):757–67. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry RB, Sriram P. Auto-adjusting positive airway pressure treatment for sleep apnea diagnosed by home sleep testing. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(12):1269–75. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooksey JA, Balachandran JS. Portable monitoring for the diagnosis of OSA. Chest. 2016;149(4):1074–81. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehsan Z, Ingram DG. Economic and social costs of sleep apnea. Curr Pulmonol Rep. 2016;5:111–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapur V, Blough DK, Sandblom RE, et al. The medical cost of undiagnosed sleep apnea. Sleep. 1999;22(6):749–55. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jennum P, Kjellberg J. Health, social and economical consequences of sleep-disordered breathing: a controlled national study. Thorax. 2011;66(7):560–6. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.143958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim RD, Kapur VK, Redline-Bruch J, et al. An economic evaluation of home versus laboratory-based diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2015;38(7):1027–37. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The New England Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council. [Accessed August 22, 2016];Diagn Treat of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults. 2013 Available at: https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Final-Report_January20132.pdf.

- 16.Drummond M, Sculpher M, Torrance G, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayas NT, Pack A, Marra C. The demise of portable monitoring to diagnose OSA? Not so fast! Sleep. 2011;34(6):691–2. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deutsch PA, Simmons MS, Wallace JM. Cost-effectiveness of split-night polysomnography and home studies in the evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2(2):145–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pietzsch JB, Garner A, Cipriano LE, et al. An integrated health-economic analysis of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in the treatment of moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2011;34(6):695–709. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seneviratne U, Puvanendran K. Excessive daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea: prevalence, severity, and predictors. Sleep Med. 2004;5(4):339–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ulfberg J, Carter N, Talback M, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness at work and subjective work performance in the general population and among heavy snorers and patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1996;110(3):659–63. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.3.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulgrew AT, Ryan CF, Fleetham JA, et al. The impact of obstructive sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness on work limitation. Sleep Med. 2007;9(1):42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jurado-Gamez B, Guglielmi O, Gude F, et al. Work-place accidents, absenteeism and productivity in patients with sleep apnea. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51(5):213–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellen R, Marshall SC, Palayew M, et al. Systematic review of motor vehicle crash risk in persons with sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2(2):193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tregear S, Reston J, Schoelles K, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and risk of motor vehicle crash: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(6):573–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karimi M, Hedner J, Habel H, et al. Sleep apnea-related risk of motor vehicle accidents is reduced by continuous positive airway pressure: Swedish Traffic Accident Registry data. Sleep. 2015;38(3):341–9. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang C, Berger M, Malhotra A, et al. Portable diagnostic devices for identifying obstructive sleep apnea among commercial motor vehicle drivers: considerations and unanswered questions. Sleep. 2012;35(11):1481–9. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watkins MR, Talmage JB, Thiese MS, et al. Correlation between screening for obstructive sleep apnea using a portable device versus polysomnography testing in a commercial driving population. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(10):1145–50. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181b68d52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garg N, Rolle AJ, Lee TA, et al. Home-based diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in an urban population. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(8):879–85. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis K, Abrams M, Stremikis K. How the Affordable Care Act will strengthen the nation’s primary care foundation. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(10):1201–3. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pack AI. POINT: does laboratory polysomnography yield better outcomes than home sleep testing? Yes Chest. 2015;148(2):306–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kundel V, Shah N. Reforming the sleep apnea care delivery paradigm: sleep center and primary care integration. Chest Physician Newsletter. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edinger JD, Grubber J, Ulmer C, et al. A collaborative paradigm for improving management of sleep disorders in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. Sleep. 2016;39(1):237–47. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]