SYNOPSIS

Dental caries and gingival and periodontal diseases are commonly occurring, preventable chronic conditions in children, and may have lifelong impacts on overall health and quality of life. These diseases are more common in disadvantaged communities and marginalized populations than their wealthier counterparts. Thus, public health approaches that stress prevention are key to improving oral health equity. There is currently limited evidence on which community-based, population-level interventions are most effective and equitable in promoting children’s oral health, even as supervised toothbrushing with fluoridated toothpaste was generally found to be effective in reducing dental caries. More rigorous measurement and reporting of study findings are needed to improve the quality of available evidence. Clinicians would do well to leverage the caregivers of children to improve the oral health of their patients. Improved understanding of the multilevel influences of children’s oral health may lead to the design of more effective and equitable social interventions.

Keywords: children’s oral health, oral health equity, dental caries, periodontal disease, intergenerational interventions, parental interventions, social interventions, community-based interventions, population-based interventions

INTRODUCTION

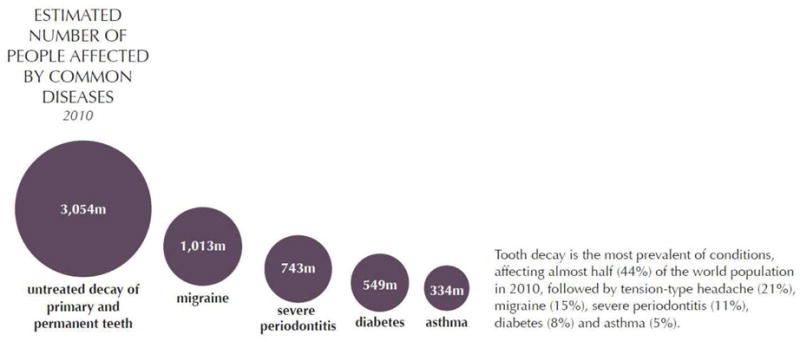

Dental caries and gingival and periodontal diseases are the most common preventable chronic oral diseases of childhood.1 Both dental caries and periodontal disease are progressive in nature and initiated early in the life course, yet both are also largely preventable.2 If left untreated, however, oral health problems in children not only cause pain and suffering and lead to oral health problems in later life, they also influence growth, development, and cognitive function.1,3 Figure 1 presents the estimated number of people affected by common diseases, with dental caries (tooth decay) affecting almost half (44%) and severe periodontitis (periodontal disease) affecting 11% of the world population in 2010.

Figure 1.

The estimated number of people affected by common diseases worldwide, with dental caries (tooth decay) affecting 3,054m people and periodontal disease (severe periodontitis) affecting 743m people.

From The Challenge of Oral Disease – A call for global action. The Oral Health Atlas. 2nd ed. Geneva: FDI World Dental Federation; 2015; with permission.

Widespread fluoridation of community drinking water in the United States has been credited in part with the decline in dental caries achieved during the second half of the twentieth century.4 Among the striking results of this community-level intervention is that tooth loss is no longer considered inevitable.4 Despite documented improvements for the US population as a whole, however, dental caries and gingival and periodontal disease disproportionately affect underprivileged, disadvantaged, and socially marginalized communities, leading to oral health inequities.5,6

Therefore, treating children solely in clinical settings and focusing entirely on those at high risk for oral disease is an ineffective strategy to reach the large numbers of children at risk for oral disease worldwide.6,7 Dental providers ought to be aware of interventions to prevent oral disease and promote oral health that begin with effective intergenerational and social interventions, which are the focus of this review.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS

Three conceptual frameworks with origins in public health scholarship are key to understanding how intergenerational and social interventions may potentially improve children’s health at the individual and population levels and promote health equity. Each of these frameworks is presented next in a stylized version with accompanying descriptions and their original sources.

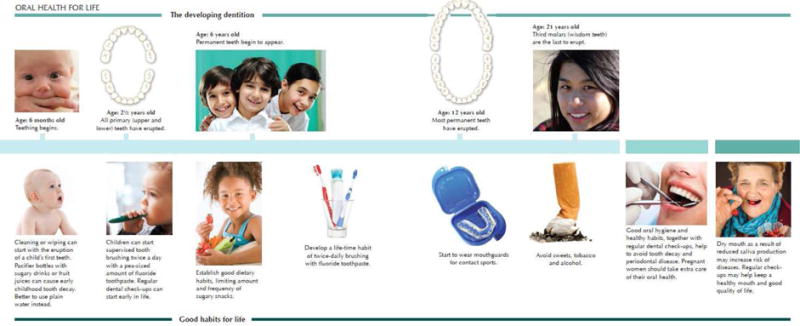

First, the life course approach is the study of long-term effects on chronic disease risk of physical and social exposures during gestation, childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, and later adult life.8 For instance, in disadvantaged populations and underserved communities, poor nutrition, lack of preventive oral health care, violence leading to face trauma, and excessive alcohol and tobacco use may affect teeth and their supporting structures, leading to dental caries (beginning in early childhood), periodontal disease (especially in adults) and eventually tooth loss (particularly in older adults).9 Figure 2 presents a simplified version of the developing dentition over the life course, along with health behaviors at critical periods that foster healthy teeth.

Figure 2.

A life course perspective on the developing dentition from infancy to later life, juxtaposed with health behaviors at critical periods that foster healthy teeth.

From The Challenge of Oral Disease – A call for global action. The Oral Health Atlas. 2nd ed. Geneva: FDI World Dental Federation; 2015; with permission.

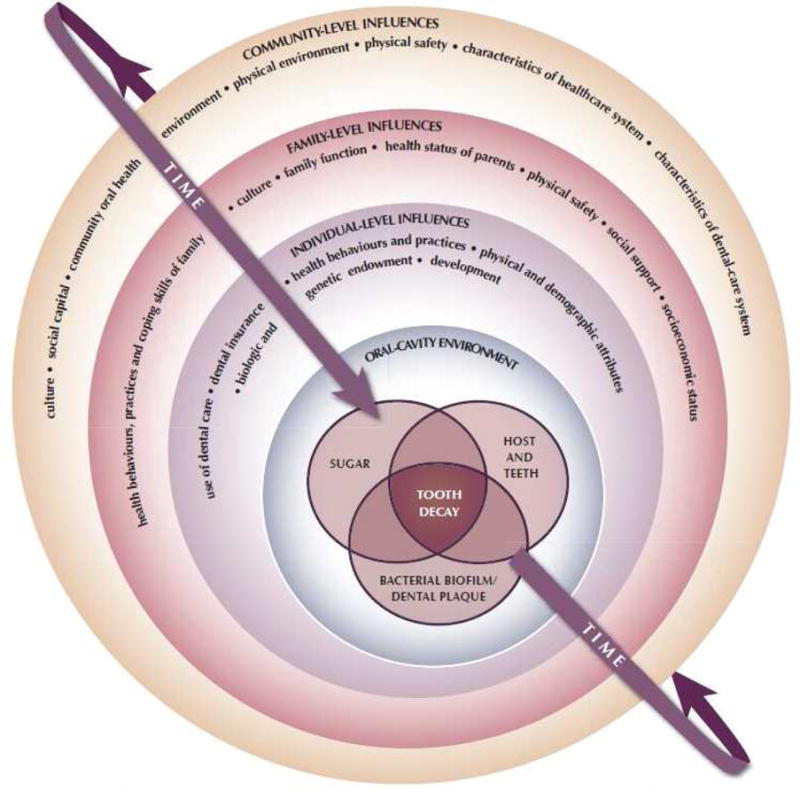

Second, socio-ecological approaches recognize the multidimensional and multilevel influences on children’s oral health. Adapting the concentric oval design from the report, Shaping a Health Statistics Vision for the 21st Century by the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics,10 Fisher-Owens and colleagues identified domains of determinants of oral health at three levels of influence: the child level, the family level, and the community level.11 A stylized version of this socio-ecological model which emphasizes that tooth decay (dental caries) is a multifactorial disease that develops over time is presented as Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A socio-ecological model of tooth decay (dental caries) as it develops over time, triggered by acid production resulting from the breakdown of sugar by bacteria, yet involving a wide range of other factors at the community, family, and individual levels.

From The Challenge of Oral Disease – A call for global action. The Oral Health Atlas. 2nd ed. Geneva: FDI World Dental Federation; 2015; with permission.

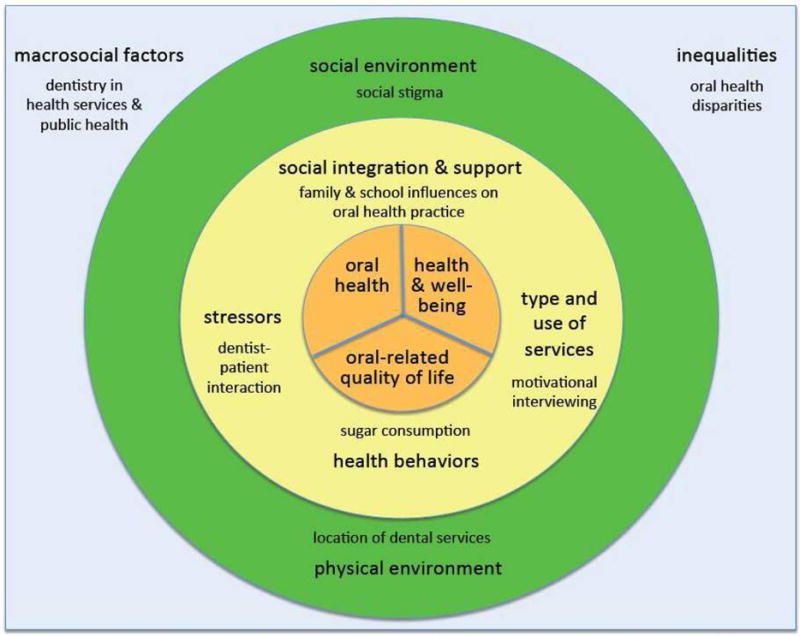

The third conceptual framework is derived in part from a health promotion model that considers dynamic social processes through which social and environmental inequalities—and associated health disparities—are produced, reproduced, and potentially transformed.12 Patrick and colleagues drew upon this model as well as the life course perspective to create an organizing framework for addressing oral health disparities.13 In Figure 4, health and well-being at the individual and population scales (notably oral health and oral-related quality of life) are shown at the center of the graphic, and particular influences at the individual scale (health behaviors, type and use of services) and interpersonal scale (stressors, social integration and support) that relate to family or social factors are depicted in the next concentric circle, followed by community scale influences (social environment, physical environment) in the subsequent concentric circle, and finally societal scale influences in the square that contains the full model (macrosocial factors, inequalities).

Figure 4.

A socio-ecological model of influences on oral health and health disparities, highlighting family and social factors.

Data from Schulz A, Northridge ME. Social determinants of health: implications for environmental health promotion. Health Educ Behav 2004;31(4):455–71; and Patrick DL, Lee RS, Nucci M, et al. Reducing oral health disparities: a focus on social and cultural determinants. BMC Oral Health 2006; 6 Suppl 1:S4.

INTERGENERATIONAL INFLUENCES

Broader ecological influences, including education, race/ethnicity, and income, and relationships with children’s oral health outcomes such as early childhood caries (ECC) have received recent empirical attention.14 Intergenerational influences, including caregivers’ attributes, attitudes, and knowledge, may be viewed as intermediary mechanisms through which societal and community influences affect children’s oral health.14 For instance, an oral health study was conducted among a random sample of 457 mother and child pairs in Tehran, Iran. Findings were that twice-daily toothbrushing behavior and sound dentition in 9-year-olds were associated with their mothers’ positive oral health-related attitudes.15 Further analysis revealed that having sound dentition was most strongly explained by the mothers’ active supervision of their children’s toothbrushing.16 Consequently, the authors argued that oral health professionals would do well to focus on the considerable potential of mothers in developing oral health promotion programs for children and adolescents.15,16

In a school-based randomized clinical trial of 423 low-income African American kindergarteners and their caregivers, results were that caregivers who completed high school were 1.78 times more likely to visit dentists compared with those who did not complete high school, which in turn was associated with 5.78 times greater odds of dental visits among their children.17 These findings confirm the role of caregiver education in child dental caries and indicate that caregiver behavioral factors are important mediators of this relationship.17

In contrast, maternal stress and anxiety can negatively affect child caretaking behaviors and child oral health. In an analysis of data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), findings were that children of mothers with an allostatic load (AL) index of at least 2, an indicator of chronic stress, were significantly more likely to have not been breastfed and to have dental caries than were children of mothers with a normal AL, before adjusting for socioeconomic status.18

A cross-sectional study with 608 mother-child dyads during the Children’s National Immunization Campaign in Pelotas, Brazil was performed.19 Findings were that children from anxious mothers were more likely to present with untreated caries even after covariate adjustment.19 Likewise, in a cross-sectional study among 187 mother-child pairs recruited from those seeking dental treatment in Udaipur, India, mothers of younger children and those with lower education and lower family income reported higher dental anxiety scores.20 Moreover, a strong positive relationship was found between maternal dental anxiety and children’s dental caries experience.20

In a systematic review of the literature on parental influence and the development of caries in children aged 0–6 years, the authors concluded that most research to date has focused on the association between caries and socio-demographic and feeding factors, with few studies exploring parents’ attributes, attitudes, knowledge and beliefs.14 Nonetheless, there is research that suggests collaboration between psychologists and dental professionals may accelerate the identification and understanding of mechanisms that underlie risk associated with children’s oral disease.14 For instance, a cross-sectional study consisting of 92 parent-child dyads (46 cases with childhood caries and 46 controls who were caries-free) was conducted in The Hague, the Netherlands among 5–6 year old children of Dutch, Moroccan, and Turkish origin presenting at a pediatric dental center.21 Findings were that parents’ internal belief of their ability to control their children’s dental health and observed positive parenting practices on the dimensions of positive involvement, encouragement, and problem-solving were important indicators of dental health in Dutch, Moroccan, and Turkish origin children, suggesting that interventions at the family level may reduce caries levels in children, especially those at high risk.21

VIEWS OF OLDER ADULTS

Older adults are important in advancing pediatric oral health, since they are both role models and caregivers of young children. As part of an ongoing study to understand factors at the individual, interpersonal, and community scales that serve as barriers and facilitators to oral health and health care among racial/ethnic minority older adults, 24 focus groups were conducted with 194 African American, Dominican, and Puerto Rican adults aged 50 years and older living in northern Manhattan, New York, NY. Older adults were approached and screened for potential participation in senior centers and other places where older adults gather in the communities of Central Harlem, East Harlem, and Washington Heights. Just over half (54%) of the focus group participants were women and just under half (49%) were predominantly Spanish speaking. Details of the recruitment and screening process are available elsewhere.22

Following standard focus group technique,23 separate groups were conducted based on gender, race/ethnicity, and history of dental care. Groups consisted of an average of 8 participants (SD = 2.4) and lasted an average of 1.3 hours (SD = 13 minutes). All groups were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. Groups were conducted using a series of semi-structured questions about the factors that serve as barriers and facilitators to oral health and health care. Among the topics explored in each group was the role of children and families, including if they “talk with their families about going to the dentist” and “anything that families do that discourages or encourages” them to go to the dentist. Although the goal was to solicit information on how older adults may receive assistance from their families, thematic content analysis24 of the transcribed focus groups revealed that:

older adults perceived generational differences between themselves and their children and grandchildren in the experiences with and the importance of oral health; and

older adults sought to encourage and assist their children and grandchildren in engaging in better oral health and health care practices more often than they received assistance from family members.

Quotes from the study participants detailing their views of generational changes and the attempts they made to influence the oral health of their children and grandchildren are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Focus group findings related to generational differences in oral health

| Sub-theme | Representative quotes |

|---|---|

| Braces |

These kids wear braces now. In my day, you didn’t wear braces. My son wore braces. Both my grandsons wear braces. I don’t know if this is the new thing. I even see adults with them. |

| Home remedies |

…Our grandparents, when you were sick, they would go to plants and make you teas…Then when you finally went to the dentist it was to justify that the tooth was no longer viable…If a tooth loosened up, they would use a string, tighten it around the tooth and pull…That’s not the way it is today, they’ve been able to improve that but that way of thinking has stayed in…you are coming out of a place where they just took out a tooth when they could have just corrected the problem. I know that my grandfather, when I was young, I was at school and one day a tooth bothered me, and then my grandfather said: open your mouth. He put in a string and pulled out the tooth…There were people who grabbed pliers and if the tooth was loose, they would just pull it… |

| Parental prioritization of oral health: then |

But people didn’t worry about it because I did not go to the dentist my mother never made the effort, not, not even (to) brush my teeth or anything like that, no. …Our parents did not concern themselves with these things…the majority of us are different with our children and grandchildren. Kids now go get their teeth cleaned every six months. Before that was not the case. It was bad—there was no guides around that issue…In other words. Things were done only when they were necessary but it was not customary to go every year, every six months, to the dentist. |

| Parental prioritization of oral health: now |

…I suppose that the new generation will not have the problems we have had. Because our generation, at for someone like me who has the teeth of an eighty-year old. And from when I was a kid, I was never taken to a dentist. I went as an adult and it hurt. But not now, look for example at my grandchildren. My daughter, since they were born here—for her the dentist is the most important…those kids are not afraid of checking their mouths or anything because they are used to go from when they are born, from the moment they come out, they start getting that stuff checked…our mothers were our dentists: they would pull out our teeth with a string… …I have a daughter who is 22. 23. And she pays a lot of attention to, “Mami, you should go to the dentist.” “Mami, you have to,” to her sister, who is younger. “We have to take her…” She pays a lot of attention to that…Because, to be honest, I don’t say too much to her. To be honest…She talks more with me. She is always paying attention. Paying attention to everything that has to do with oral hygiene. |

| Importance of oral health over time |

…We have children walking around at sixteen years old that they got no teeth in their mouth, apparently something is wrong with this age generation…I think is diet…Everything they eat has preservative in it they don’t eat natural, they don’t eat fresh…A lot of things that we eat have so many different chemicals, you know and things like that…My mother and my father have perfect teeth. I was the one with the cavities… I have noticed that with the time that is passing by, for me in the past people worried more about their teeth…There are so many more illnesses that people concentrate more on those and forget about their teeth, because that is not so important…because of diabetes I lost some teeth. But when I was younger, I did not think too much about my own teeth. I only began to do this when I got sick, that I realized that I was losing my teeth, then I made an effort that I said, this will be my priority. Teeth, first. |

| School-based dental care over time |

Now, I went to a school where we had a dental clinic…They don’t have that anymore. They don’t have a lot of stuff anymore that they had in schools. We need more oral education…when most of us here were school-age, you knew about the dentist…You knew about the dentist…You know today? Number one: they don’t have a dentist in school…That’s non-existent. We had that…We had that…If not and you came from a decent family, a family that could afford it, you went to the dentist. |

Table 2.

Focus group findings related to influences on children/grandchildren around oral health

| Sub-theme | Representative quotes |

|---|---|

| School-based influences |

…Two of my grand kids are in charter schools…You take your child to the dentist…They will send you a letter home, you know, to tell you about taking the child to the dentist. When I was volunteering in the system…I would show the children…I would show them my partial and I would say this is what happens if you don’t go to the dentist…And, I worked 25 years in two schools. I think I have affected enough people for the next coming generation. All I did was take out my teeth… |

| General advice to take care of mouths |

I tell my children: take care of your teeth, take care of your mouth… …My children are in Puerto Rico…when I call them on the phone I tell them that…to take care of their mouths. |

| Offer brushing and flossing advice |

I give advice to my grandchildren…that you should brush your teeth well…every day. I tell my grandson that he has to brush his teeth, take dental floss and how he brushes his mouth too. …Children in the morning should brush their teeth to avoid having to go to the dentist all of the time…And at night, before going to bed, they should brush too. After a meal in the afternoon as well. |

| Encourage dental visits |

I think it [fear] comes from childhood, because children don’t like to go to the dentist, and it’s a struggle. I talk to mine about making sure that they [children] go to the dentist so they’ll maintain a healthy mouth…You know, so I just have one of my kids that will not go to the dentist and he’s had a chipped tooth since he was a senior in high school and he will not go so that’s on him but all the rest of them have beautiful sets of teeth and make sure that they maintain them. So it’s only one of the bunch—that’s OK. |

| Inspect mouths and breath |

…I talk with them [grandchildren] because I am always paying attention that—I open their mouths and observe their teeth, their molars, everything. I always try to make them pick up their toothpaste and clean their mouths two or three times per day. And I do the most I can. You need to clean it as often as you eat. …I always think about a grandson I have. Very often, two or three times a day, I ask him, “Did you go brush?”…“Then go brush up if you haven’t brushed your teeth.”…And I say, “Come here. Breathe out in front of me. That’s OK,” after he brushes because if not, go back and brush again…one of the things that keep the most bacteria is our tongue. |

| Children encourage parents and parents encourage children |

Well, what she [daughter] does, though, is she goes—whenever she goes to a dentist…she’ll say to me: “When was the last time you get into a dentist?” “Well, sometime. I haven’t been there in a while, you know, but I’ll be going soon.” Next week, or in a couple of days, she’ll call me, “Daddy: did you go to the dentist?” You know. That’s one thing she does which is towards my health… I have a daughter that stays with me at home…And when we are going to bed, I go and brush my teeth. And then I see that she doesn’t move and I say, “[name], go to the bathroom. Go wash your mouth.” |

| Use own oral health as a lesson |

…I’ve explained to them [grandchildren] what happens to me so you need to take care of your teeth. Brush in the morning, if you can’t in the afternoon, before you go to bed…the experience that we have in our teeth in our mouth we don’t want them to go through the same thing you know that we are going through…We want prevent the next generation coming up our siblings, our grandchildren from going through what we are presently going through so if we educate in all aspects of life, we need to educate the upcoming generation as far as health teeth, you know, everything. …I tell my grandkids you don’t want to be like grandma. Keep, take care, brush your teeth, brush the tongue, the top of the mouth… Why do you have to fight with your children that don’t want to, they don’t even brush their teeth? And they’re big and you have to be there ‘brush your teeth so you don’t end up without teeth like me’… I got to tell my grandkids…They say, “Grandpa: I got more teeth than you do.” ‘Cause I smile and he smiles, and he’s got teeth that I don’t. Like when he asks me why I have no teeth and then I explain it to him. I talk a lot with my granddaughter and with my other grandkids. What I say to them: look, I lose my teeth because I did not wash them, let’s go to the dentist, you have to wash your mouth, brush your teeth, brush them after eating, before going to bed, you brush them to ensure that what happened to me doesn’t happen to you and they go do that…they say: mama, mama, look that I just ate and I am going to wash my mouth. They are trained to do that. |

| Institute oral hygiene habits |

It’s all [oral health] based on habit. Starting with school, that’s the first thing they tell you, mouthwash, brush your teeth three times per day. That’s the main thing…When my kids were little, that was the first thing I would tell them about…that’s a duty. I live with my two sons and the first thing my kids have to do—because I taught them from when they were little—with cleanliness has to do mainly with their mouths. |

These findings underscore the observation that good oral health is now accepted as a social norm in the United States,4 even in disadvantaged communities, and that clinicians may usefully leverage the care and devotion of older adults toward their children and grandchildren in promoting improved oral health and health care practices.

INTERGENERATIONAL INTERVENTIONS

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a patient-centered approach focusing on building intrinsic motivation for change.25 MI was originally used in treating addictive behaviors and has since been successfully used to influence the caries prevention behaviors of mothers on behalf of their children.26,27 One proposed mechanism of action is greater compliance with recommended fluoride varnish regimens in families who receive MI counseling as compared to families who receive traditional education.27

Recently, a health coaching approach has been developed based on: an interactive assessment; a non-judgmental exploration of patients’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs; a mapping of patient behaviors that may contribute to disease progression; gauging patient motivation; and tailoring health communication to encourage health-promoting behavior change.28 While there is not yet evidence on effectiveness, this may provide an approach to working with adolescents directly and family members who may in turn promote the oral health of their children. This is important since analysis of data from a prospective cohort study of 1037 children born at Queen Mary Hospital, Dunedin, New Zealand found that the children of mothers with poor oral health had themselves (on average) poorer oral health almost three decades later.29 Standard questions about maternal oral health ought to form part of dental professionals’ preliminary assessments of children’s future oral health risk.29

As part of the Baby Teeth Talk Study in a remote First Nations community in Manitoba, Canada, grandmothers who are considered local health knowledge keepers were recruited to participate in a total of 20 interviews and four focus groups.30 Three key findings pertaining specifically to culturally based childrearing practices and infant oral health were identified and explored (feeding infants country foods from an early age, use of traditional medicine to address oral health issues, and the role of swaddling in the development of healthy deciduous teeth) as a means of restoring skills and pride and a mechanism for building family and community relationships as well as intergenerational support.30 Clinicians ought to be open to discussing traditional and cultural approaches to childrearing with the caregivers of their patients.

SOCIAL INTERVENTIONS

The social determinants (social influences) of children’s oral health are covered in Drs. da Fonseca and Avenetti’s article on “Social Determinants of Pediatric Oral Health” in this issue, so this topic will not be reviewed here. Instead, the focus of this section is social interventions on children’s oral health. An important systematic review on community-based population-level interventions for promoting child oral health was recently published.32 Overall, the authors found evidence of low certainty that community-based oral health promotion interventions that combine oral health education with supervised toothbrushing or professional preventive oral care can reduce dental caries in children.32 While interventions that aim to promote access to fluoride in its various forms and reduce sugar consumption hold promise for preventing caries, additional studies are needed to determine their effectiveness in community settings.32

A systematic review of oral health interventions aimed at Alaska Native children aged 18 years and younger found that few were tested within Alaska Native communities.33 Nonetheless, community-centered multilevel interventions to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage intake among Alaska Native children were deemed promising.33 Another systematic review was conducted on the influence of family environment on children’s oral health.34 The authors concluded that since parents’ dental habits influence their children’s dental habits, special attention should be given to the entire family, not only to prevent oral disease, but to improve quality of life.34

In a study that compared changes in parent-reported pediatric oral health-related quality of life between children with ECC and children who were caries free, findings at baseline were that children with ECC were more likely to have fair or poor oral health and were rated as having more pain and trouble with physical, mental, and social functioning due to their teeth or mouth versus caries-free children.35 At 6 and 12 months following dental treatment for ECC, however, there were significant positive impacts on parental ratings of their children’s overall oral health and physical, mental, and social functioning.35

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence, etiology, and types of dental trauma in children and adolescents, even as the prevalence of dental trauma was variable based on geographic area, the overall prevalence was 17.5%, with a higher prevalence in boys.36 The major reason for dental trauma was falls, which occurred mainly at home and most commonly resulted in enamel fracture.36 Policies that may prevent and reduce the severity of oral trauma include:

Enforce regulations to increase road safety through the mandatory use of seat belts, child seats, motorcycle and bicycle helmets, and the prevalence of driving while under the influence of alcohol or other mind-altering drugs;

Implement appropriate strategies to reduce violence and bullying at school;

Enforce the mandatory use of helmets and mouthguards to improve safety for contact sports;

Strengthen the role of dentists in diagnosing trauma as a result of violence and child abuse; and

Ensure appropriate emergency care for improved post-trauma response.37

FUTURE POSSIBILITIES AND RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Dental caries are the most prevalent disease of childhood and are principally caused by sugar consumption. Thus, reducing sugar consumption as part of a healthy diet promotes better oral health and may reduce diabetes, obesity, and other unhealthy conditions. Policies for sugar reduction include:

Enforce higher taxation on sugar-rich foods and sugar-sweetened beverages;

Ensure transparent food labeling for informed consumer choices;

Strongly regulate sugar in baby foods and sugar-sweetened beverages;

Limit marketing and availability of sugar-rich foods and sugar-sweetened beverages to children and adolescents; and

Provide simplified nutrition guidelines, including sugar intake, to promote healthy eating and drinking.37

To further reduce dental caries in children, universal access to affordable and effective fluoride and universal access to primary oral health care are key strategies.37 There is little evidence in the literature that oral health education alone is effective in preventing dental caries, although select studies have reported improvements in gum health, oral hygiene behaviors, and oral cleanliness.32 On the other hand, oral health promotion interventions combined with supervised toothbrushing with fluoridated toothpaste were generally found to be effective in reducing childhood caries.32

Future possibilities include multi-component and multi-setting interventions that integrate oral health with general health promotion and care where children live, learn, and play, delivered by social service and health care teams. Dental providers need to recognize the multiple influences of broader determinants linked to clinical oral health outcomes, e.g., oral health knowledge, behaviors and practices, and health care systems, including psychosocial environments.32 In the future, there may be less reliance on dental professionals and researchers to deliver interventions and increased reliance on, e.g., community health workers, to create cost-effective and sustainable solutions for promoting children’s oral health.38 Interventions informed by theory, such as the health promoting school approach, community capacity building, and community engagement, in addition to the oral health promotion frameworks presented here, would reveal best practices.

Research is needed to overcome the limitations in the scientific literature to date on the effectiveness of intergenerational and social interventions to improve children’s oral health. In particular, it would be important to:

Conduct more studies in lower-middle-income and low-income countries;

Conduct more studies in regions of the world that are currently underrepresented in the evidence base, such as Africa and South America;

Include assessment of long-term follow-up post-intervention, including adverse effects and sustainability;

Include strategies to address diversity and disadvantage in the populations studied;

Engage community stakeholders in intervention development and implementation;

Target adolescents as an understudied group;

Collect and report economic and cost-effectiveness data, which is especially important to policy makers;

Strengthen the scientific approaches used, including implementation science39 and systems science40;

Undertake analysis that expands the understanding of determinants, moderators, and pathways involved in promoting oral health in children;

Explore relationships between and across multiple levels of influence; and

Apply scientific rigor and quality standards to the design, implementation, delivery, and reporting of future intervention studies.32

Finally, it is imperative that effective interventions are described in such a way that they may be replicated or assessed for suitability for use in other contexts, as per the constructs of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.41 Without losing effective components of the interventions, available information must enable adaptations to be performed to suit community needs.39,41

KEY POINTS.

Community context and the influence of the broader social determinants of health such as education, race/ethnicity, and income are important considerations in achieving oral health equity for children.

Intergenerational influences, including caregivers’ attributes, attitudes, and knowledge, may be viewed as intermediary mechanisms through which societal and community influences affect children’s oral health.

Promising social intervention approaches to improving children’s oral health include improving access to fluoride in its various forms and reducing sugar consumption.

Linking community-based dental services with settings where children live, learn, and play, such as day care centers and schools, is important for oral health promotion.

Integrating oral health education with supervised toothbrushing with fluoridated toothpaste or professional oral care practices may prevent dental caries in children.

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported in the research, analysis, and writing of this paper by the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research of the US National Institutes of Health for the project titled, Integrating Social and Systems Science Approaches to Promote Oral Health Equity (grant R01-DE023072). The authors thank Bianca A. Dearing, DDS, MPhil for early insights into the topic and interpretation of the focus group findings.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The Authors have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Mary E. Northridge, Associate Professor, Department of Epidemiology & Health Promotion, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY USA, Professor of Clinical Sociomedical Sciences (in Dental Medicine), Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, New York, NY USA.

Eric W. Schrimshaw, Associate Professor, Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, New York, NY USA.

Ivette Estrada, Project Coordinator, Section of Population Oral Health, Columbia University College of Dental Medicine, New York, NY USA.

Ariel P. Greenblatt, Project Director, Department of Epidemiology & Health Promotion, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY USA.

Sara S. Metcalf, Associate Professor, Department of Geography, The State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY USA.

Carol Kunzel, Associate Professor of Community Dentistry and Sociomedical Sciences at CUMC, Section of Population Oral Health, Columbia University College of Dental Medicine and Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, New York, NY USA.

References

- 1.Jürgensen N, Petersen PE. Promoting oral health of children through schools—results from a WHO global survey 2012. Community Dent Health. 2013;30(4):204–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Satur JG, Gussy MG, Morgan MV, et al. Review of the evidence for oral heath promotion effectiveness. Health Education Journal. 2010;69(3):257–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen PE. Sociobehavioral risk factors in dental caries—international perspectives. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(4):274–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Division of Oral Health. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: fluoridation of drinking water to prevent dental caries. MMWR. 1999;48:933–940. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin LJ, Armitage GC, Klinge B, et al. Global oral health inequalities: task group— periodontal disease. Adv Dent Res. 2011;23:221–6. doi: 10.1177/0022034511402080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watt RG. From victim blaming to upstream action: tackling the social determinants of oral health inequalities. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watt RG. Strategies and approaches in oral disease prevention and health promotion. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:711–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges, and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:285–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Northridge ME, Lamster IB. A life course approach to preventing and treating oral disease. Soz Praventivmed. 2004;49(5):299–300. doi: 10.1007/s00038-004-4040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics. Shaping a Health Statistics Vision for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services Data Council, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher-Owens SA, Gansky SA, Platt LJ, Weintraub JA, Soobader MJ, Bramlett MD, et al. Influences on children’s oral health: a conceptual model. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):e510–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulz A, Northridge ME. Social determinants of health: implications for environmental health promotion. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(4):455–71. doi: 10.1177/1090198104265598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patrick DL, Lee RS, Nucci M, Grembowski D, Jolles CZ, Milgrom P. Reducing oral health disparities: a focus on social and cultural determinants. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooley M, Skouteris H, Boganin C, Satur J, Kilpatrick N. Parental influence and the development of dental caries in children aged 0–6 years: a systematic review of the literature. J Dent. 2012;40(11):873–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saied-Moallemi Z, Virtanen JI, Ghofranipour F, et al. Influence of mothers’ oral health knowledge and attitudes on their children’s dental health. Eur Archives Paediatr Dent. 2008;9(2):79–83. doi: 10.1007/BF03262614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saied-Moallemi Z, Vehkalahti MM, Virtanen JI, et al. Mothers as facilitators of preadolescents’ oral self-care and oral health. Oral Health Prev Dentistry. 2008;6(4):271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heima M, Lee W, Milgrom P, et al. Caregiver’s education level and child’s dental caries in African Americans: a path analytic study. Caries Res. 2015;49(2):177–83. doi: 10.1159/000368560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masterson EE, Sabbah W. Maternal allostatic load, caretaking behaviors, and child dental caries experience: a cross-sectional evaluation of linked mother-child data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2306–11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goettems ML, Ardenghi TM, Romano AR, et al. Influence of maternal dental anxiety on the child’s dental caries experience. Caries Res. 2012;46(1):3–8. doi: 10.1159/000334645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khawja SG, Arora R, Shah AH, et al. Maternal dental anxiety and its effect on caries experience among children in Udaipur, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(6):ZC42–45. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/13647.6103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duijster D, de Jong-Lenters M, de Ruiter C, et al. Parental and family-related influences on dental caries in children of Dutch, Moroccan and Turkish origin. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015;43(2):152–62. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Northridge ME, Shedlin M, Schrimshaw EW, et al. Recruitment of racial/ethnic minority older adults through community sites for focus group discussions. BMC Public Health. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4482-6. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research (4th ed) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borrelli B, Tooley EM, Scott-Sheldon LA. Motivational interviewing for parent-child health interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37(3):254–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albino J, Tiwari T. Preventing childhood caries: a review of recent behavioral research. J Dent Res. 2016;95(1):35–42. doi: 10.1177/0022034515609034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein P, Harrison R, Benton T. Motivating mothers to prevent caries: confirming the beneficial effect of counseling. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(6):789–93. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vernon LT, Howard AR. Advancing health promotion in dentistry: articulating an integrative approach to coaching oral health behavior change in the dental setting. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2015;2(3):111–22. doi: 10.1007/s40496-015-0056-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shearer DM, Thomson WM, Broadbent JM, et al. Maternal oral health predicts their children’s caries experience in adulthood. J Dent Res. 2011;90:672–7. doi: 10.1177/0022034510393349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cidro J, Zahayko L, Lawrence H, et al. Traditional and cultural approaches to childrearing: preventing early childhood caries in Norway House Cree Nation, Manitoba. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(4):2968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Silva AM, Hegde S, Akudo Nwagbara B, et al. Community-based population-level interventions for promoting child oral health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Sep 15;9:CD009837. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009837.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chi DL. Reducing Alaska Native paediatric oral health disparities: a systematic review of oral health interventions and a case study on multilevel strategies to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage intake. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72:21066. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castilho AR, Mialhe FL, Barbosa TS, et al. Influence of family environment on children’s oral health: a systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2013;89(2):116–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunnion DT, Spiro A, 3rd, Jones JA, et al. Pediatric oral health-related quality of life improvement after treatment of early childhood caries: a prospective multisite study. J Dent Child (Chic) 2010;77(1):4–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azami-Aghdash S, Ebadifard Azar F, Pournaghi Azar F, et al. Prevalence, etiology, and types of dental trauma in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2015;29(4):234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benzian H, Williams D, editors. The challenge of oral disease: a call for global action. Brighton, UK: Myriad Editions; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Northridge ME, Kavathe R, Zanowiak J, Wyatt L, Singh H, Islam N. Implementation and dissemination of the Sikh American Families Oral Health Promotion Program. Transl Behav Med. doi: 10.1007/s13142-017-0466-4. re-review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lomas J. Diffusion, dissemination, and implementation: who should do what? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;703:226–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26351.x. discussion 235–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mabry PL, Olster DH, Morgan GD, Abrams DB. Interdisciplinarity and systems science to improve population health: a view from the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2S):S211–S224. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]