Abstract

High-grade gliomas are the most prevalent and lethal primary brain tumors. They display a hierarchical arrangement with a population of self-renewing and highly tumorigenic cells called cancer stem cells. These cells are thought to be responsible for tumor recurrence, which make them main candidates for targeted therapies. Unbridled cell cycle progression may explain the selective sensitivity of some cancer cells to treatments. The members of the Cip/Kip family p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 were initially considered as tumor suppressors based on their ability to block proliferation. However, they are currently looked at as proteins with dual roles in cancer: one as tumor suppressor and the other as oncogene. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the functions of these cell cycle inhibitors in five patient-derived glioma stem cell–enriched cell lines. We found that these proteins are functional in glioma stem cells. They negatively regulate cell cycle progression both in unstressed conditions and in response to genotoxic stress. In addition, p27Kip1 is upregulated in nutrient-restricted and differentiating cells, suggesting that this Cip/Kip is a mediator of antimitogenic signals in glioma cells. Importantly, the lack of these proteins impairs cell cycle halt in response to genotoxic agents, rendering cells more vulnerable to DNA damage. For these reasons, these proteins may operate both as tumor suppressors, limiting cell proliferation, and as oncogenes, conferring cell resistance to DNA damage. Thus, deepening our knowledge on the biological functions of these Cip/Kips may shed light on how some cancer cells develop drug resistance.

Abbreviations: CSC, cancer stem cell; DDR, DNA damage response; GSC-ECLs, glioma stem cell–enriched cell line; NR, nutrient restriction

Introduction

Gliomas are the most common type of primary brain neoplasms, accounting for approximately 30% of central nervous system tumors and 80% of all malignant brain tumors. Within this group, glioblastoma multiforme, a high-grade glioma (World Health Organization grade IV glioma) [1], [2], is characterized by elevated intratumoral heterogeneity, diffuse infiltration throughout the brain parenchyma, and resistance to traditional therapies, which inevitably leads to tumor recurrence and the demise of the patient [3]. The high rate of cancer relapse suggests that current therapies do not eradicate all malignant cells. In this regard, a subpopulation of tumor cells called cancer stem cells (CSCs) has been identified in gliomas and in many other cancers. These cells are characterized by their capacity of self-renewal and by their enriched tumorigenic potential [4], [5], [6]. Furthermore, CSCs are also known for their ability to differentiate into both rapidly proliferating progenitor-like tumor cells and more differentiated tumor cells that define the histological features of the tumor entity [7]. Importantly, CSCs appear to be more resistant towards radio- and chemotherapy than the highly proliferative progenitors that coexist within the tumor. To effectively eradicate CSCs and thus avoid cancer recurrence, it is critical to target their essential functions. Increased resistance of glioblastoma multiforme cells to radiotherapy was suggested to be due to the DNA damage response (DDR), which is preferentially activated in CSCs as compared to non-CSC counterparts [8], [9], [10].

The DDR is a network of signaling pathways that is able to sense and repair DNA lesions. The activation of DDR also modulates other cellular processes, including cell cycle checkpoint regulation and programmed cell death. DDR induces cell cycle arrest to allow repair of DNA lesions; however, if too much damage has been sustained, DDR triggers cell death to avoid the generation of deleterious mutations [11]. The progression along the cell cycle requires the activation of different cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). Tight CDK regulation involves CDK inhibitors (CKIs) which ensure the correct timing of CDK activation in different phases of the cell cycle. The CKIs include the INK4 family and the Cip/Kip family. In mammals, the Cip/Kip family consists of three proteins, p21Cip1, p27Kip1, and p57Kip2. As a critical negative regulator of the cell cycle, p21Cip1 binds to and inhibits both CDK/cyclin complexes and PCNA [12], [13]. Therefore, based on its capacity to block cell proliferation, p21Cip1 may act as a tumor suppressor [14], [15]. However, evidence has revealed novel functions of p21Cip1, such as the control of cell migration, regulation of apoptosis, and maintenance of stem cell pools, among others [13], [16], [17], [18]. In fact, p21Cip1 can acquire an antiapoptotic gain of function in the cytoplasm, pointing to a dual role for p21Cip1 as both a tumor suppressor and an oncogene [19], [20]. Also, p21Cip1 induction is essential for the onset of cell cycle arrest in DDR, giving cells time to repair critical damage [21]. Despite the absence of p21Cip1 in some cancer types, its overexpression or cytoplasmic localization correlates with poor prognosis in malignant tumors of the skin, pancreas, breast, prostate, ovary, cervix, and brain [18]. Similarly, p27Kip1 may act as a tumor suppressor through inactivation of cyclin/CDK complexes in the nucleus, but tumorigenic properties of p27Kip1 have also been proposed, especially when located in cytoplasm [20], [22]. Cytosolic p27Kip1 promotes cell proliferation via interaction with cyclin D/CDK4 [23] and cell migration via inhibition of RhoA/ROCK signaling [24]. In many cancers, p27Kip1 expression is reduced in the nucleus and exhibits different degrees of cytoplasmic localization [25]. High nuclear and low cytoplasmic expression of p27Kip1 has been associated with a better prognosis in high-grade astrocytoma [26]. Moreover, an inverse correlation between p27Kip1 immunoreactivity and the Ki-67 labeling index was observed in patients with malignant gliomas [27].

Although p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 were initially considered as tumor suppressors, it rapidly became clear that the situation was not so simple. It appears that the loss of the regulatory mechanisms governing Cip/Kip proteins may lead to the specific loss of its tumor suppressor function while maintaining the oncogenic ones, favoring cancer development. In this context, we wondered whether p21Cip1 and p27Kip1function as tumor suppressors or oncogenes in patient-derived glioma stem cell–enriched cell lines (GSC-ECLs) [28]. To address this issue, we investigated the role of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in the response of GSC-ECLs to camptothecin (CPT), a potent and specific inhibitor of eukaryotic DNA topoisomerase I that induces DNA double-strand breaks. Initially, we examined the expression pattern of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in five GSC-ECLs. After CPT exposure, we observed a marked increase in the expression levels of these Cip/Kips, which displayed a predominant nuclear localization. Finally, by small interfering RNA (siRNA)–mediated downregulation of both p21Cip1 and p27Kip1, we determined that these CKIs confer protection against CPT in a cell line–dependent manner. This protection may be due, at least in part, to the ability of these inhibitors to halt cell cycle progression. Therefore, the significance of cell cycle regulators in the pathobiology of these tumors is of interest, and the roles of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 need to be elucidated further.

Materials and Methods

Culture of Human Glioma–Derived Cells and Treatments

Brain tumor–derived cultures were isolated from biopsies and established as previously described [28]. GSC-ECLs were cultured in serum-free medium consisting of neurobasal medium supplemented with B27, N2, 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF), 2 mM L-glutamine, 2 mM nonessential amino acids, 50 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 20 μg/ml bovine pancreas insulin, and 75 μg/ml low-endotoxin bovine serum albumin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and plated onto Geltrex-coated plates (10 μg/ml) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were routinely grown to confluence, dissociated using Accutase, and then split 1:2 to 1:3. Medium was replaced every 2 to 3 days. To induce differentiation, cells were cultured for 14 days in the same medium without bFGF and EGF.

To induce genotoxic stress, cells were incubated in 1 μM CPT (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). To generate nutritional stress, cells were incubated in neurobasal medium without supplements.

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng of total RNA using MMLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI). Quantitative PCR studies were carried out using SYBR Green-ER™ qPCR SuperMix UDG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Primers used were the following: p21Cip1 forward 5′-ATGACAGATTTCTACCACTC-3′, reverse 5′-AAGACACACAAACTGAGAC-3′; p27Kip1 forward 5′-GGCTAACTCTGAGGACAC-3′, reverse 5′-TTCTTCTGTTCTGTTGGC-3′; and RPL7 forward 5′-AATGGCGAGGATGGCAAG-3′, reverse 5′-TGACGAAGGCGAAGAAGC-3′. All samples were analyzed using an ABI PRISM 7500 Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and were normalized to RPL7 gene expression.

Immunostaining and Fluorescence Microscopy

Cells were analyzed for in situ immunofluorescence. Briefly, cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in PBS with 4% formaldehyde for 25 minutes. After two washes with PBS with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (PBSA), cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBSA with 10% normal goat serum for 30 minutes, washed twice, and stained with the corresponding primary antibodies. Fluorescent secondary antibodies were used to localize the antigen/primary antibody complexes. Nuclei were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and examined under a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-S inverted microscope equipped with a 20× E-Plan objective and a super high-pressure mercury lamp. The images were acquired with a Nikon DXN1200F digital camera, which was controlled by the EclipseNet software (version 1.20.0 build 61). The following primary antibodies were used: α-p21Cip1 (Cat. 556430 clone SX118) (BD Pharmingen, Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA), α-p27Kip1(sc-528) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and α-MAP-2 (M1406) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Western Blotting

Cells were lysed in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer supplemented with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor mixture, and protein concentration was determined using Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equal amounts of protein were run on 12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF-FL membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membrane was blocked for 1 hour in Odyssey blocking buffer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) containing 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated overnight at 4°C in a solution containing Odyssey blocking buffer, 0.05% Tween 20, and the corresponding primary antibodies. The membrane was washed 4 × 5 minutes with Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TTBS); then incubated for 1 hour in a solution containing Odyssey blocking buffer, 0.2% Tween 20, and IR-Dye secondary antibodies (1:20,000, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE); and subsequently washed 4 × 5 minutes in TTBS and 1 × 5 minutes in TBS. Immunocomplexes were visualized using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR). The following primary antibodies were used: α-p21Cip1 (Cat. 556430 clone SX118) (BD Pharmingen, Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA), α-p27Kip1 (sc-528) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and α-actin (sc-1616) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Antigen/primary antibody complexes were detected with near-infrared fluorescence-labeled IR-Dye 800CW or IR-Dye 680RD secondary antibodies (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Cell Transfection and RNA Interference

Cells were transfected with the corresponding siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 2 × 105 cells/well (six-well plate) were transfected with Silencer Select Negative Control #2 (Ambion, cat. 4390846), Silencer Select Validated CDKN1A siRNA (Ambion, siRNA ID: s417), and Silencer Select Validated CDKN1B siRNA (Ambion, siRNA ID: s2838). The concentrations of siRNA used for cell transfections (2.5-5 nM) were selected based on dose-response studies.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Cell Viability Using Propidium Iodide (PI)

Single-cell suspensions were obtained by treatment with Accutase (37°C for 5-10 minutes), centrifuged at 200×g for 5 minutes, and resuspended in FACS buffer (2.5 mM CaCl2, 140 mM NaCl, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). Next, 100 μl of cellular suspension was incubated with 5 μl of PI (1 mg/ml) in PBS for 5 minutes in the dark. Cells were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Results were expressed as the percentage of cells that displayed PI fluorescence (nonviable) to the total number of cells processed. Fluorescence intensity was determined by flow cytometry on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using BD AccuriC6 software.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) Incorporation and Cell Cycle Distribution

To characterize the distribution of cell populations throughout the cell cycle and the fraction of cells capable of incorporating BrdU, the BrdU Flow Kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was used. After the corresponding treatments, cells were incubated with BrdU (10 μM) for 2 hours. Cultures were then processed following manufacturer's instructions. Fluorescence intensity was determined by flow cytometry on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using BD AccuriC6 software.

Assessment of DNA Fragmentation

Apoptosis was quantified by direct determination of nucleosomal DNA fragmentation with Cell Death Detection ELISAPlus kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). This assay uses specific monoclonal antibodies directed against histones and DNA, allowing the determination of mono- and oligonucleosomes in the cytoplasmic fraction of cell lysates. Briefly, 3 × 104 cells were plated on 96-well plates in 150 μl of culture medium. Forty-eight hours after CPT (1 μM) addition or nutrient restriction, cells were processed according to the manufacturer's manual. The mono- and oligonucleosomes were determined using an anti–histone-biotin antibody and an anti–DNA-peroxidase antibody. The resulting color development, which was proportional to the amount of nucleosomes captured in the antibody sandwich, was measured at 405-nm wavelength using a Benchmark microtiter plate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Results were expressed as fold change, calculated from the ratio of absorbance of treated samples to that of the untreated ones.

Results

GSC-ECLs Display Differential Degrees of Susceptibility to Stress Conditions

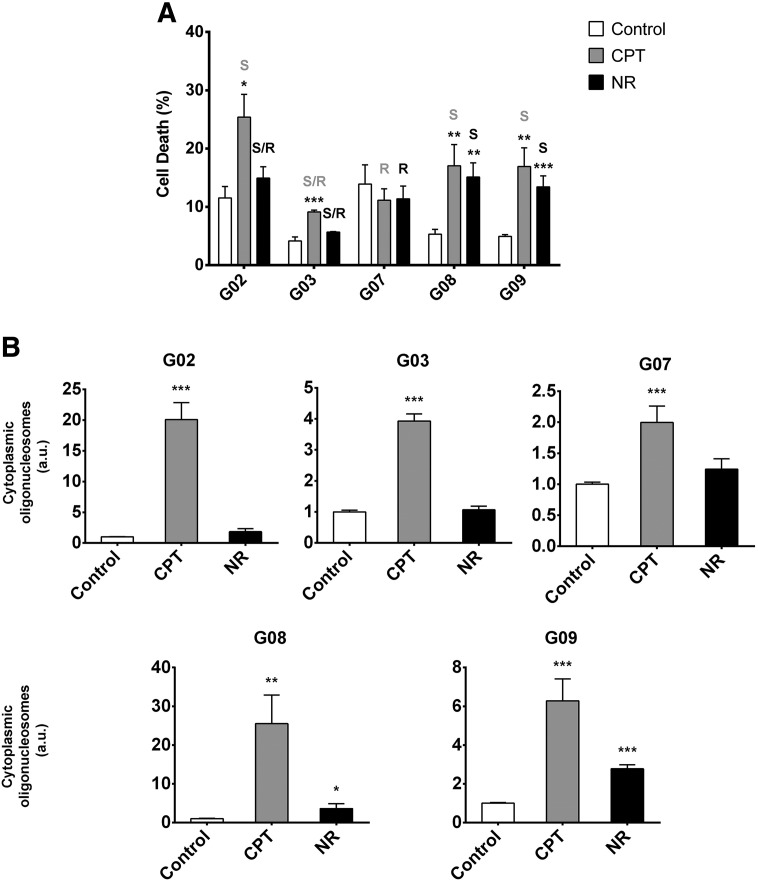

CSC resistance to chemo- and radiotherapy is clinically important as most current anticancer agents target the tumor bulk but not the CSC population. Thus, to gain insight into the responses achieved by GSC-ECLs upon DNA damage, we sought to compare how five GSC-ECLs (G02, G03, G07, G08, and G09) that were previously established and characterized in our laboratory [28] respond to CPT. To do so, we determined the percentage of cell death of GSC-ECLs after 48 hours of 1-μM CPT exposure by PI staining. As indicated in Figure 1, the tested cell lines responded differently to genotoxic stress. We found that CPT exposure led to a considerable increase in cell death in the G02 (16.5 ± 4%), G08 (14.07 ± 3.96%), and G09 (11.99 ± 3.19%) cell lines (Figure 1A, gray bars); however, for the G03 cell line, this increment was only slight (4.98 ± 0.62%). Notably, the G07 cell line was almost totally insensitive to this topoisomerase I inhibitor.

Figure 1.

GSC-ECLs exhibit differential susceptibilities in response to stress conditions. (A) Bar charts show the mean of PI-stained cells 48 hours after CPT or nutrient restriction exposure. Percentage of PI positive cells was determined by flow cytometric analysis. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. A one-way ANOVA was used to classify cell lines according to their susceptibility to stress conditions. R, resistant; S, sensitive. (B) Forty-eight hours after CPT exposure or nutrient restriction, cells were harvested, and cytoplasmatic DNA oligomers were quantified by immunoassay. Results are presented as DNA oligomers fold induction versus untreated control cells, arbitrarily set as 1. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Student's t test was used to compare CPT- or NR-treated samples to untreated controls (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001). a.u., arbitrary units; NR, nutrient restriction.

Tumor cells emerge as a result of genetic and epigenetic alterations of signal circuitries promoting cell growth and survival, whereas their expansion relies on nutrient supply. More specifically, cells possessing flexibility in nutrient utilization will be able to survive under nutrient stress. Keeping this in mind, we wondered whether these GSC-ECLs are susceptible to nutritional stress and, if so, if they will respond equally among them or in a cell line–specific manner as occurred with CPT treatment. To find the answer, we cultured these cell lines in basal medium (deprived of supplements) for 48 hours and assessed cell death. Similarly to what occurred under CPT exposure, nutrient limitation led to a significant decrease in the G08 and G09 cell line viability and a slight decrease in the G03 cell line. Again, no significant changes were observed in the G07 cell line. However, whereas the G02 cell line was very sensitive to CPT, no major changes in its viability were detected under nutritional stress (Figure 1A, black bars). After carrying out a one-way ANOVA to compare the responses to stress of the different cell lines, we were able to identify resistant cell lines (R), sensitive cell lines (S), and some that could not be classified as either (S/R) (Figure 1A).

The loss of cell viability was accompanied by morphological changes such as ballooning and cell detachment, which are suggestive of apoptotic processes (data not shown). Thus, to investigate whether the observed decrease in cell viability was due to the induction of apoptosis, we determined cell death levels of stressed and unstressed cells by quantifying cytoplasmatic DNA oligomers. Results indicate the presence of significantly higher levels of histone-bound oligonucleosomes in CPT-treated cells compared to nontreated counterparts, ranging from approximately 2- to 25-fold increase in the G07 and G08 cell lines, respectively. Interestingly, nutritional restriction led to an increase in the percentage of DNA oligomers only in some cell lines. Concordant with our previous data obtained by PI staining, the G08 and G09 cell lines were more susceptible to nutrient and growth factors deprivation, whereas the G02, G03, and G07 cell lines appeared to be relatively insensitive (Figure 1B).

Stress Conditions Promote Cell Cycle Arrest in GSC-ECLs

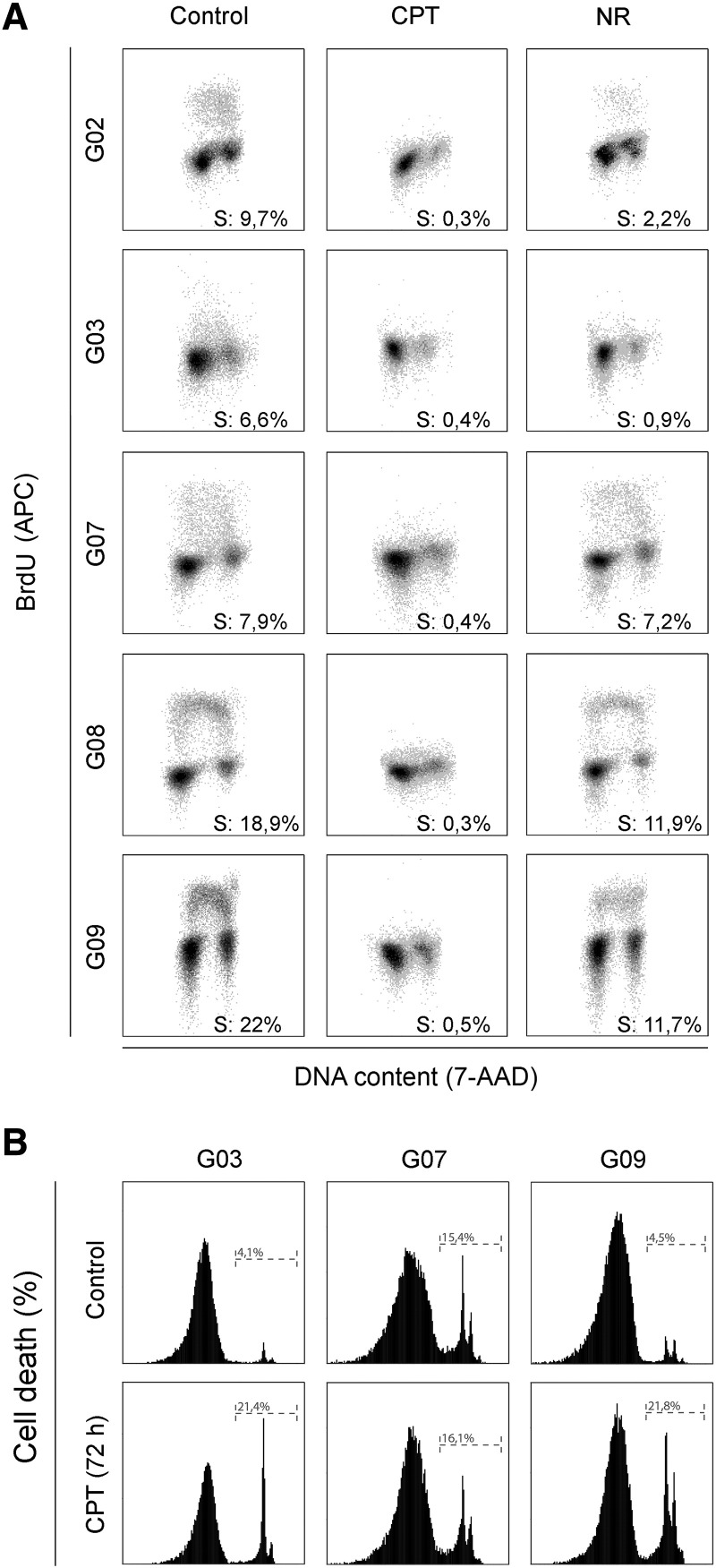

To further elucidate if the loss of cell viability after CPT exposure was accompanied by changes in cell proliferation, we measured BrdU incorporation by flow cytometry. As judged by BrdU labeling, CPT treatment led to an almost complete inhibition of DNA replication. In the case of nutrient restriction, all tested cell lines displayed a partial reduction in their BrdU incorporation (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Stress conditions reduce GSC-ECL proliferation. Cells were subjected to CPT or nutrient restriction (NR), or left untreated for 48 hours. Then, cells were pulse labeled with BrdU for 2 hours prior to harvesting and stained with BrdU-APC conjugate and with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) for determination of DNA synthesis and DNA content, respectively. A representative flow cytometry plot is shown for each experimental condition. Dot plots show incorporation of BrdU into DNA (y-axis) against DNA content (7-AAD staining; x-axis). The percentage of cells in S phase was determined by quantifying BrdU+ events. (B) Representative histograms of PI-stained CPT-treated (1 μM) GSC-ECLs over a 72-hour period or untreated cells. Percentage of PI positive cells was determined by flow cytometric analysis.

Importantly, we found that cells endowed with a higher proliferation rate when unstressed were the ones that were more sensitive to CPT-induced DNA damage (Figures 1 and 2A). This is in accordance with the fact that the cytotoxicity of CPT is highly S phase specific. Thus, we wondered whether the CPT-resistant phenotype exhibited by the G03 and G07 cell lines was associated with their low proliferating rates. It stands to reason that possibly during the time frame of CPT exposure, a great proportion of the G03 and G07 cell populations did not have enough time to enter S phase and thereby had not been affected by CPT toxicity. To solve this issue, we extended the time of CPT exposure for up to 72 hours and assessed cell death. Importantly, the G03 cell line, which displays an intermediate susceptibility (S/R) at 48 hours, finally was sensitive to CPT at 72 hours posttreatment. On the contrary, the G07 cell line maintained its resistance to genotoxic stress at this time point (Figure 2B).

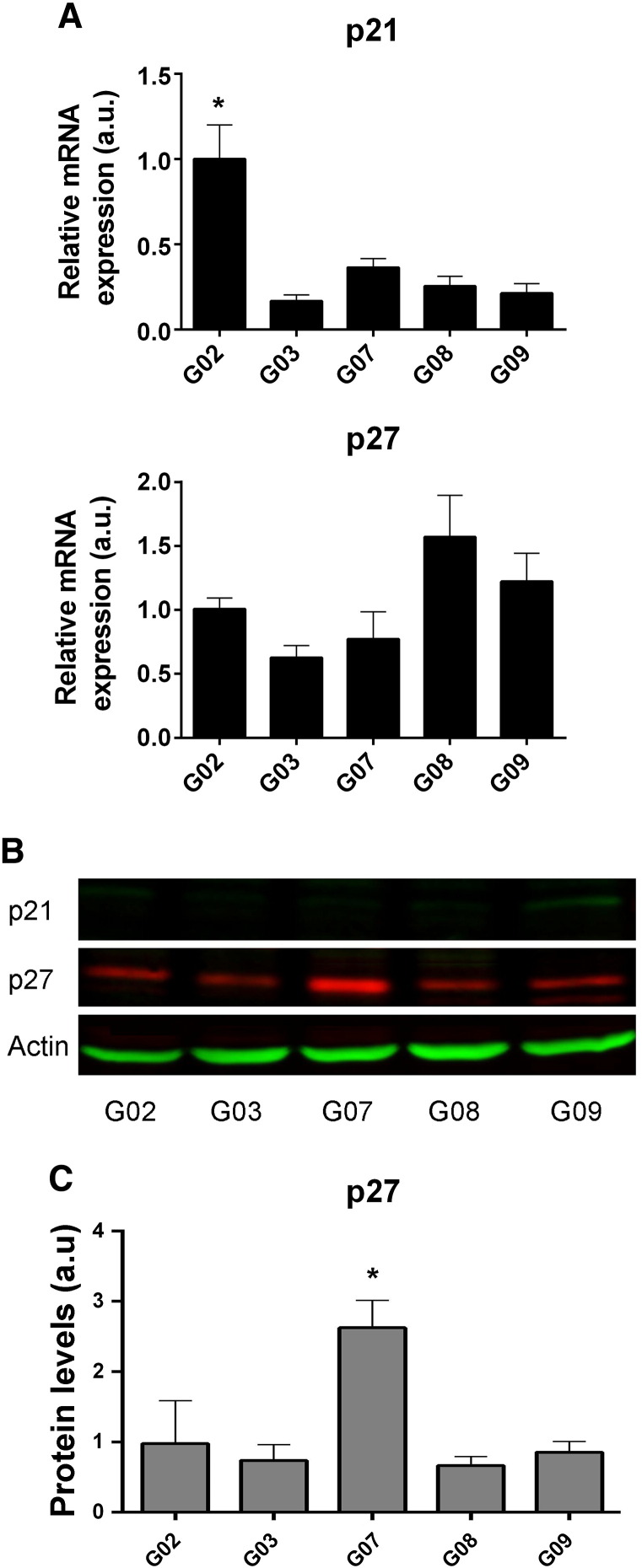

p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 Expression in GSC-ECLs

Initially, we examined the expression levels of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in GSC-ECLs. Real-time RT-PCR analysis showed that all tested cell lines express similar levels of p21Cip1 mRNA except for G02, which expresses higher levels of this transcript (Figure 3A). In parallel, we performed Western blots analysis and observed that p21Cip1 protein levels were practically below the detection threshold (Figure 3B). Similarly, p27Kip1 mRNA expression levels did not significantly differ among all studied cell lines (Figure 3A). However, we found that GSC-ECLs expressed easily detectable amounts of p27Kip1 protein, which was more abundant in the G07 cell line (Figure 3B). Interestingly, we determined that, within these cell lines, there was not a tight correlation between p27Kip1 mRNA levels and the corresponding protein product. These findings suggest that mechanisms controlling protein concentration (e.g., many steps in transcription and translation as well as degradation) may operate distinctively in each cell line.

Figure 3.

p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 expression in GSC-ECLs. (A) Analysis of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 mRNA expression levels by quantitative RT-PCR in GSC-ECLs. RPL7 expression was used as normalizer. Graphs show mRNA fold change relative to G02 cell line. Bars represent the mean ± S.E.M. of three different experiments performed in triplicate. (B) p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 protein levels were analyzed by Western blot. Actin was used as loading control. (C) The intensity of p27Kip1 and corresponding actin band was evaluated by densitometric analysis. Values were normalized to actin, and intensity is expressed as fold change relative to G02 line expression. A Newman-Keuls test was conducted to detect significant differences between cell lines (*P < .05).

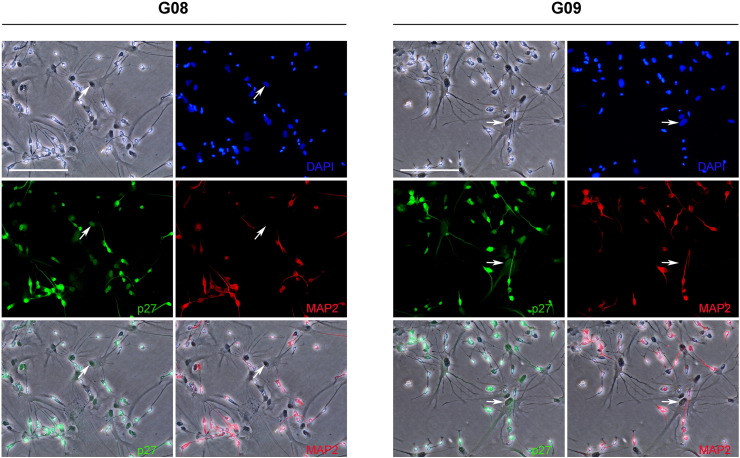

CSCs frequently give rise to a differentiated progeny that has lost the ability for self-renewal. Therefore, this would imply that remnant regulatory mechanisms that guide the differentiation process are still present in cancer cells. Therefore, to gain insight into the differentiation process of GSC-ECLs, we assessed by immunofluorescence staining the expression of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in G08 and G09 cell lines 14 days after differentiation onset. Similarly to what we observed in undifferentiated cells, p21Cip1 immunoreactivity was almost completely absent in differentiating cells (data not shown). On the other hand, we found that p27Kip1 was present in nearly all differentiated cells. Importantly, cells exhibiting protruding processes and expressing the neuronal marker MAP2 appeared intensely stained for p27Kip1 (Figure 4). However, astrocyte-like cells (MAP2−) showed lower p27Kip1 immunoreactivity which could only be detected in the nucleus (Figure 4, white arrows). GSC-ECLs significantly diminish their proliferation rates at day 14 of differentiation [28]. The fact that p27Kip1 but not p21Cip1 is present in the nucleus of differentiated cells suggests that this Cip/Kip may be involved in mechanisms that govern CSC transition to a postmitotic state.

Figure 4.

Differentiated glioma stem cells express high levels of nuclear p27Kip1. Representative phase contrast and immunofluorescent images of G08 and G09 cell lines after 14 days under differentiating conditions (bFGF and EGF withdrawal). Cells were stained with antibodies against MAP2 and p27Kip1. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Objective 20×; scale bar: 50 μm. White arrows point to less intensely labeled astrocyte-like cell nuclei.

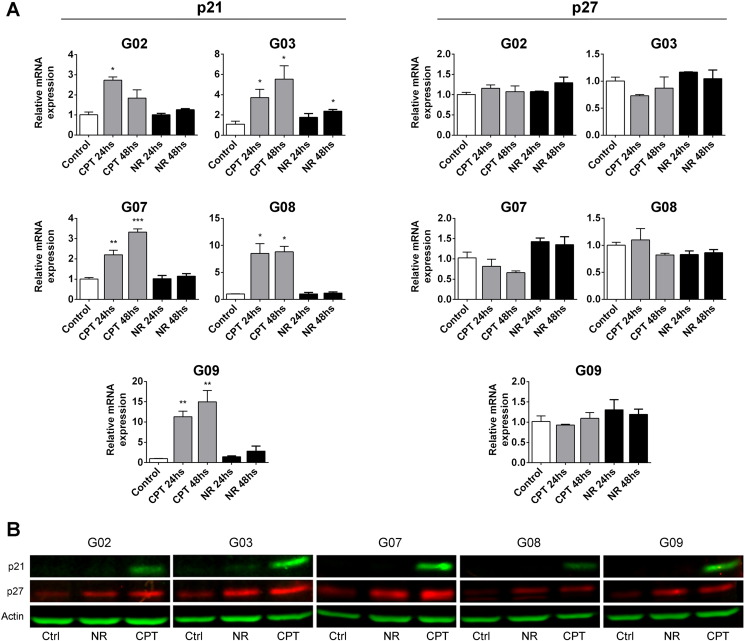

Stress Conditions Induce the Expression and the Relocalization of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in GSC-ECLs

A better understanding of the molecular mechanisms that impact CSC response and resistance to treatments may be helpful in predicting clinical outcome and developing more effective therapies for different subtypes of high-grade gliomas. In this sense, considerable evidence exists demonstrating the roles of cell cycle mediators in determining a cell's fate upon different forms of stress [16], [29], [30]. Thus, to investigate possible molecular mechanisms underlying the responses of GSC-ECLs to CPT and to nutrient restriction, we explored changes in the expression levels of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 under these stress conditions. Real-time RT-PCR analysis revealed that p21Cip1 mRNA expression levels robustly increased at both 24 and 48 hours after CPT addition in all cell lines. Contrarily, with the exception of G03 cell line, no significant changes in p21Cip1 mRNA expression levels were observed in cells exposed to nutrient restriction. On the other hand, p27Kip1 mRNA levels did not vary significantly upon treatments (Figure 5A). Next, we performed Western blot analysis to evaluate if there was a correlation between the mRNA expression and the corresponding protein levels. As indicated in Figure 5B, p21Cip1 expression was robustly induced only in CPT-treated cells. Conversely, a marked increase in the levels of p27Kip1 was observed 48 hours after genotoxic stress or nutrient restriction.

Figure 5.

p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 abundance after CPT exposure or nutrient restriction in GSC-ECLs. (A) Analysis of p21Cip1and p27Kip1 mRNA expression levels by real-time RT-PCR in GSC-ECLs after CPT treatment or nutrient restriction over a 24- or 48-hour period. RPL7 expression was used as normalizer. Graphs show mRNA fold change relative to untreated control cells, arbitrarily set as 1. Bars represent the mean ± S.E.M. of three different experiments performed in triplicate. Student's t test was used to compare CPT- or NR-treated to untreated samples (*P ˂ .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001). (B) Western blot analysis of GSC-ECLs under control conditions and after 48 hours of CPT exposure or nutrient restriction. Antibodies against p21Cip1, p27Kip1, and actin (loading control) were used.

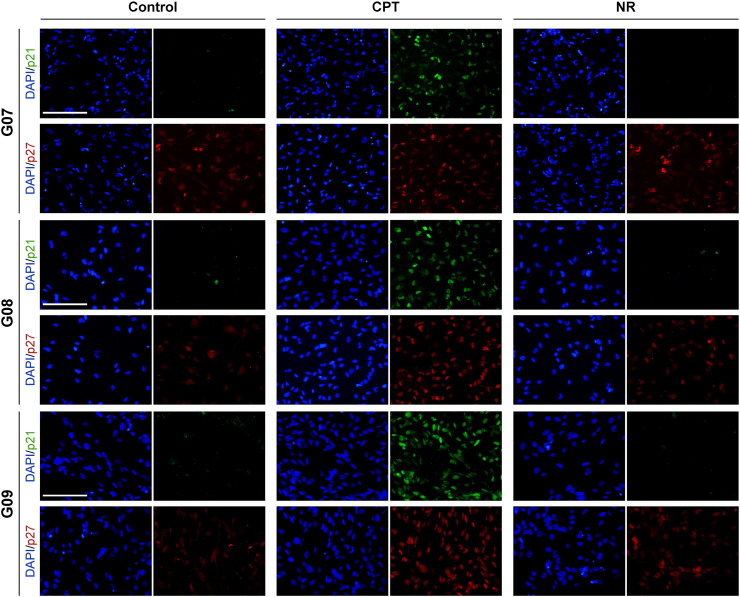

An important aspect of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 functions is associated with their cellular localization. Thus, to investigate whether CPT treatment or nutrient restriction modulates the subcellular localization of these Cip/Kips, we assessed p21Cip and p27Kip1 distribution by fluorescence microscopy. In accordance with Western blot results, immunofluorescence staining revealed a strong induction of p21Cip1 in CPT-treated cells. Importantly, p21Cip1 showed a marked nuclear localization. Again, the expression levels of p21Cip1 were undetectable in unperturbed or nutrient-restricted cells. With regard to p27Kip1, both experimental conditions led to an increase in the nuclear abundance of this Cip/Kip, which was more evident in CPT-treated cells (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 expression and localization in GSC-ECLs exposed to stress conditions. Immunofluorescence staining of CPT-treated (1 μM) or nutrient-restricted cells over a 24-hour period. The figure shows representative photomicrographs of G07, G08, and G09 cells stained with primary antibodies against p21Cip1 and p27Kip1. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Objective 20×; scale bar, 50 μm.

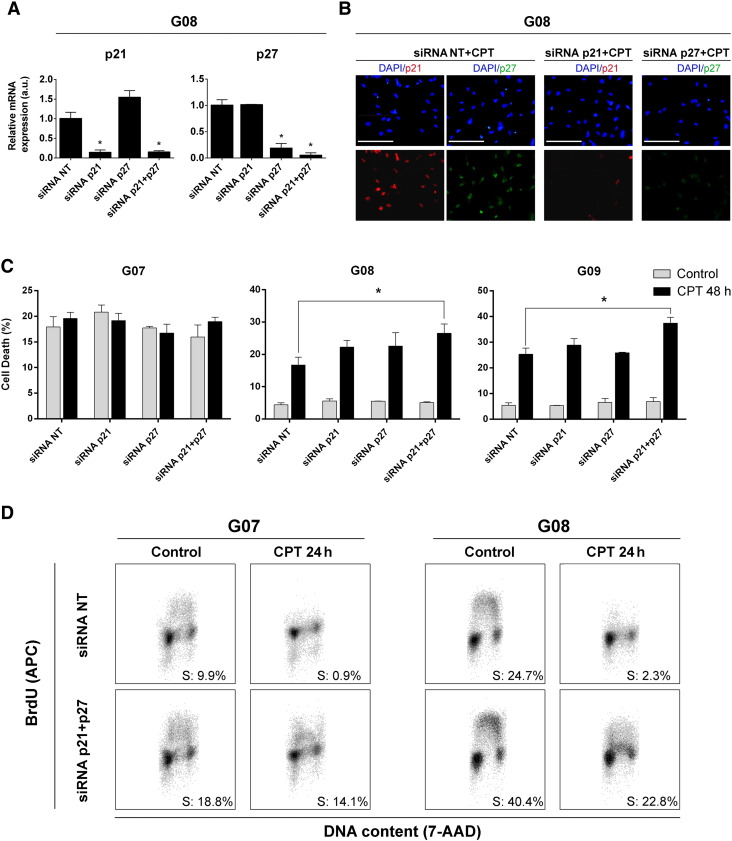

siRNA-Mediated Gene Silencing of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 Sensitizes GSC-ECLs to Genotoxic Stress

Because p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 are induced by genotoxic stress and high-grade gliomas display an elevated tumor recurrence after standard treatments, we wondered if these Cip/Kips may contribute to GSC-ECL chemoresistance. To address this issue, we examined the effect elicited by specific siRNAs targeting p21Cip1, p27Kip1, or both in the cellular response triggered by CPT. To do so, we first transfected G07, G08, and G09 cell lines with the specific siRNAs, and 48 hours posttransfection, we determined the expression levels of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 mRNAs by real-time RT-PCR. In all cases, we found that the levels of the target transcripts decreased significantly (Figure 7A). We also corroborated that the expression levels of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 were not affected when nontargeting (NT) siRNA was used as negative control. Additionally, 24 hours after CPT exposure, we performed immunofluorescence assays to determine the expression levels of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in siRNA-transfected cell populations. We observed that even in the presence of genotoxic stress, the expression of each Cip/Kip was markedly reduced with respect to that determined in the NT siRNA–transfected counterparts (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 downregulation affects proliferation and viability of GSC-ECLs. (A) mRNA expression levels of p21Cip1 and p27 Kip1 in NT-, p21Cip1-, p27Kip1-, or dual-siRNA–transfected G08 cells were analyzed 48 hours posttransfection by real-time RT-PCR. RPL7 expression was used as normalizer. Graph shows mRNA fold change relative to NT-siRNA transfectants, arbitrarily set as 1. (B) Representative immunofluorescent images of NT-, p21Cip1- or p27Kip1-siRNA transfectants exposed to CPT (1 μM, 24 hours) 24 hours posttransfection. Cells were stained with antibodies against p21Cip1 and p27Kip1. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. (C) G07, G08, and G09 cells were transfected with NT-, p21Cip1-, p27Kip1-, or dual-siRNA and exposed to CPT 24 hours posttransfection. Bar charts show the mean of PI-stained cells 48 hours after CPT addition. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. Student's t test was used to compare p21Cip1-, p27Kip1-, or dual- to NT-siRNA transfectants (*P < .05). (D) Twenty-four hours posttransfection with the corresponding siRNA, G08 and G09 cells were left untreated or subjected to CPT for 24 hours. A representative flow cytometry plot is shown for each experimental condition. Dot plots show incorporation of BrdU into DNA against DNA content. The percentage of cells in S phase was determined by quantifying BrdU+ events.

To establish if p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 are involved in mechanisms that confer resistance of GSC-ECLs to stress conditions, we measured cell death after silencing these Cip/Kips either individually or simultaneously under basal conditions or when subjected to genotoxic stress. When evaluating the effect of siRNA-mediated gene silencing in unstressed cells, no changes in the extent of cell death were observed. In contrast, when cells were exposed to CPT, we found that only the simultaneous silencing of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 led to a significant increase in cell death in the G08 and G09 cell lines. Strikingly, in the G07 cell line, no changes were observed under these conditions (Figure 7C).

siRNA-Mediated Gene Silencing of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 Increases Proliferation and Impairs the Cell Cycle Arrest After DNA Damage

The observed increase in p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 and their nuclear localization triggered by CPT suggest that these proteins are necessary to block cell cycle progression of GSC-ECLs exposed to genotoxic stress, thereby preventing cell death. To assess this, we first evaluated G08 cell line viability and cell cycle arrest along the first 24 hours post-CPT addition. We found that CPT led to an almost complete cell cycle halt without a significant increase in cell death (data not shown). Then, to gain insight into the role of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in cell cycle regulation, we used siRNA to target both Cip/Kips in G07 and G08 cell lines (a resistant and a sensitive cell line, respectively) and determined cell proliferation by BrdU incorporation before and 24 hours after genotoxic insult. Silencing of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in untreated cells led to a marked increment in the percentage of BrdU+ cells, which implies that these Cip/Kips negatively regulate cell cycle progression in unperturbed cells. Furthermore, in both G07 and G08 cell lines, simultaneous knockdown of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 significantly impaired cell cycle arrest upon CPT exposure (Figure 7D). This finding suggest that, in GSC-ECLs, the DDR induces p21Cip gene expression and stabilizes p27Kip1 protein product to mediate cell cycle arrest to give time to repair the damaged DNA and prevent excessive cell death.

Discussion

High-grade gliomas are extremely lethal infiltrative primary brain tumors that cannot be completely removed by surgery. Even with the current standard treatment, involving surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy with temozolamide, the median life expectancy of high-grade gliomas is 15 to 18 months [2]. The almost total recurrence of these tumors is due to an incomplete eradication of tumorigenic cells. To this end, the emergence of the CSC theory has brought consciousness to the fact that eradicating CSCs may be critical to overturn treatment resistance. CSCs resist treatments due to several mechanisms. One such mechanism involves the active transport of chemotherapeutic agents to the extracellular space via ABC-type transporters on the cell surface. Other mechanisms include the upregulation of antiapoptotic proteins; the DNA damage checkpoint; and the activation of distinct molecular networks including Notch, NF-κB, EZH2, and PARP signaling [10], [31], [32], [33], [34]. Besides, gliomas usually display altered cell cycle profiles such as deletions of CDKN2A and RB1 genes and overexpression/amplification of CDK4 and/or CDK6 [35], [36], [37]. These alterations result in cell cycle checkpoints’ failure. When checkpoint arrest control is compromised, initiation of S phase or mitosis may proceed despite cellular damage [30]. Thus, unraveling the role of cell cycle regulators in controlling glioma CSC radio- and chemoresistance is essential for the development of innovative targeted cancer therapies.

Cip/Kips promote cell cycle arrest in response to antiproliferative signals such as DNA damage or growth factor withdrawal [38]. However, these inhibitors also participate in numerous cell cycle–independent functions, such as apoptotic processes, cell migration, and DNA repair [29]. Given their multiple roles, the cellular and molecular context in which they are found will determine whether they function as tumor suppressors or as oncogenes. These considerations, together with the fact that all tested GSC-ECLs harbor homozygous deletion of CDKN2A/ARF, prompted us to explore the role of two Cip/Kip family members, p21Cip1 and p27Kip1, in the cellular response to stress conditions. In this scenario, we evaluated the susceptibility of different GSC-ECLs to genotoxic or nutritional stress. Our findings allowed us to classify the tested cell lines after genotoxic exposure or nutrient restriction into groups either sensitive or resistant. Consistent with the fact that the cytotoxicity of CPT is S phase specific, we found that lines displaying higher levels of BrdU incorporation were more sensitive to topoisomerase I inhibition. Also, under nutritional stress, these cell lines responded distinctively. Although the tested GSC-ECLs differ considerably in their resistance to stress conditions and proliferative capacity, they did not show considerable differences with respect to p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 expression levels. Moreover, in studied cell lines, these Cip/Kips underwent a similar regulation in response to differentiating conditions. Similarly to what occurs during neurogenesis, a marked increase in p27Kip1 expression levels was observed [39]. This finding suggests that the role of this Cip/Kip is preserved in glioma CSC differentiation. In this regard, it has been reported that high expression of p27Kip1 is associated with a better prognosis in malignant gliomas [40]. This correlation could be explained, at least in part, by considering that tumors harboring higher expression of this protein could correspond to more differentiated and therefore less aggressive tumors.

p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 are well-known inducers of cell cycle arrest in response to genotoxic and nutritional stress [38]. Thus, the study of how these Cip/Kips are regulated in response to stress conditions in patient-derived GSC-ECLs is relevant. To this end, we determined that p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 were induced upon CPT exposure in all tested cell lines. Contrarily, in nutrient-restricted cells, only p27Kip1 was upregulated. In all cases, a predominant nuclear localization of these Cip/Kips was observed upon stress. The response displayed by p21Cip1 was expected as this protein is a recognized key player in the DDR [16]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the role of p27Kip1 in the DDR of glioma CSCs was currently unclear.

Given the molecular complexity and the intertumor heterogeneity present in high-grade gliomas, patient-derived GSC-ECLs raise the possibility of studying the DDR in a cell line–specific manner, paving the way to the development of tailor-made therapies. Thus, by silencing p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in resistant and sensitive GSC-ECLs, we evaluated the role of these Cip/Kips in cell survival after DNA damage. siRNA-mediated downregulation allowed us to determine that, in two sensitive cell lines (G08 and G09), p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 appeared to be relevant to prevent cell death when facing genotoxic stress. Strikingly, in the aforementioned cell lines, only the simultaneous silencing of both Cip/Kips caused an increase in DNA damage–induced cell death. Furthermore, the dual silencing also impaired the ability of glioma stem cells to arrest cell cycle after CPT exposure, which could explain, at least in part, the observed increment in cell death. Therefore, the lack of these proteins may contribute to sensitize glioma CSCs to chemotherapeutic agents. On the other hand, no appreciable changes were detected when silencing p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in the resistant cell line (G07). Nevertheless, as occurred in a sensitive cell line, the simultaneous silencing of both Cip/Kips caused a defective cell cycle halt in DNA-damaged cells. The highly resistant phenotype of this cell line (even in the absence of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1) could be attributed to a disconnection between apoptosis, DDR, and cell cycle checkpoint regulation, rendering cells less vulnerable to genotoxic agents. These results, together with the fact that both Cip/Kips were upregulated and localized in the nucleus after CPT treatment, indicate that these proteins may have functional redundancy in the regulation of cell cycle progression in response to DNA damage in glioma stem cells.

The complex network regulating p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 functions warrants caution with regard to its application for cancer therapy. In this sense, our findings suggest that these proteins may be exerting antagonistic functions in glioma stem cells. Although p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 confer protection against DNA damage, they also negatively control proliferation of GSC-ECLs. Thus, the downregulation of these proteins may lead to uncontrolled tumor cell proliferation. The results presented herein highlight the importance of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in the cell cycle control and drug resistance of glioma stem cells, providing new insights into the field of glioma biology.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Funding

This research was supported by Fundación para la Lucha contra las Enfermedades Neurológicas de la Infancia (FLENI) and did not receive any specific grant from other funding agencies.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Andrés Cervio (Neurosurgery Department, FLENI), Dr. Horacio Martinetto (Neuropathology Department, FLENI), and Dr. Blanca Diez (Neurooncology Department, FLENI) for their cooperation. We also would like to thank María Cecilia Donato for her wise advices. V. A. F., M. S. R. V., and S. M. are Graduate Fellows and L. R. is Research Member of CONICET. G. A. V. R. is a postdoctoral Fellow of Instituto Nacional del Cáncer.

Contributor Information

Olivia Morris-Hanon, Email: oliviamorrishanon@gmail.com.

Verónica Alejandra Furmento, Email: alejandra_furmento@hotmail.com.

María Soledad Rodríguez-Varela, Email: sole.r.v@hotmail.com.

Sofía Mucci, Email: sofia_mucci@hotmail.com.

Damián Darío Fernandez-Espinosa, Email: dfernandez@fleni.org.ar.

Leonardo Romorini, Email: lromorini@fleni.org.ar.

Gustavo Emilio Sevlever, Email: gsevlever@fleni.org.ar.

María Elida Scassa, Email: mescassa@fleni.org.ar.

Guillermo Agustín Videla-Richardson, Email: willyvidelar@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Lathia JD, Mack SC, Mulkearns-Hubert EE, Valentim CL, Rich JN. Cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1203–1217. doi: 10.1101/gad.261982.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Allgeier A, Fisher B, Belanger K. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cloughesy TF, Cavenee WK, Mischel PS. Glioblastoma: from molecular pathology to targeted treatment. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bonn VE, Hawkins C, Squire J, Dirks PB. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:755–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollard SM, Yoshikawa K, Clarke ID, Danovi D, Stricker S, Russell R, Bayani J, Head R, Lee M, Bernstein M. Glioma stem cell lines expanded in adherent culture have tumor-specific phenotypes and are suitable for chemical and genetic screens. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:568–580. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eramo A, Ricci-Vitiani L, Zeuner A, Pallini R, Lotti F, Sette G, Pilozzi E, Larocca LM, Peschle C, De Maria R. Chemotherapy resistance of glioblastoma stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1238–1241. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altaner C. Glioblastoma and stem cells. Neoplasma. 2008;55:369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, Hao Y, Shi Q, Hjelmeland AB, Dewhirst MW, Bigner DD, Rich JN. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444:756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell. 2010;40:179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bloom J, Pagano M. To be or not to be ubiquitinated? Cell Cycle. 2004;3:138–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pei XH, Xiong Y. Biochemical and cellular mechanisms of mammalian CDK inhibitors: a few unresolved issues. Oncogene. 2005;24:2787–2795. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin-Caballero J, Flores JM, Garcia-Palencia P, Serrano M. Tumor susceptibility of p21(Waf1/Cip1)-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6234–6238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franklin DS, Godfrey VL, O'Brien DA, Deng C, Xiong Y. Functional collaboration between different cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors suppresses tumor growth with distinct tissue specificity. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6147–6158. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.16.6147-6158.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbas T, Dutta A. p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:400–414. doi: 10.1038/nrc2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coqueret O. New roles for p21 and p27 cell-cycle inhibitors: a function for each cell compartment? Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romanov VS, Pospelov VA, Pospelova TV. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21(Waf1): contemporary view on its role in senescence and oncogenesis. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2012;77:575–584. doi: 10.1134/S000629791206003X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreis NN, Sanhaji M, Rieger MA, Louwen F, Yuan J. p21Waf1/Cip1 deficiency causes multiple mitotic defects in tumor cells. Oncogene. 2014;33:5716–5728. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blagosklonny MV. Are p27 and p21 cytoplasmic oncoproteins? Cell Cycle. 2002;1:391–393. doi: 10.4161/cc.1.6.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gartel AL, Tyner AL. Transcriptional regulation of the p21((WAF1/CIP1)) gene. Exp Cell Res. 1999;246:280–289. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sicinski P, Zacharek S, Kim C. Duality of p27Kip1 function in tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1703–1706. doi: 10.1101/gad.1583207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larrea MD, Liang J, Da Silva T, Hong F, Shao SH, Han K, Dumont D, Slingerland JM. Phosphorylation of p27Kip1 regulates assembly and activation of cyclin D1-Cdk4. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6462–6472. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02300-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Besson A, Gurian-West M, Schmidt A, Hall A, Roberts JM. p27Kip1 modulates cell migration through the regulation of RhoA activation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:862–876. doi: 10.1101/gad.1185504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slingerland J, Pagano M. Regulation of the cdk inhibitor p27 and its deregulation in cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2000;183:10–17. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200004)183:1<10::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hidaka T, Hama S, Shrestha P, Saito T, Kajiwara Y, Yamasaki F, Sugiyama K, Kurisu K. The combination of low cytoplasmic and high nuclear expression of p27 predicts a better prognosis in high-grade astrocytoma. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirla RM, Haapasalo HK, Kalimo H, Salminen EK. Low expression of p27 indicates a poor prognosis in patients with high-grade astrocytomas. Cancer. 2003;97:644–648. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Videla Richardson GA, Garcia CP, Roisman A, Slavutsky I, Fernandez Espinosa DD, Romorini L, Miriuka SG, Arakaki N, Martinetto H, Scassa ME. Specific preferences in lineage choice and phenotypic plasticity of glioma stem cells under BMP4 and Noggin influence. Brain Pathol. 2016;26:43–61. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim S, Kaldis P. Cdks, cyclins and CKIs: roles beyond cell cycle regulation. Development. 2013;140:3079–3093. doi: 10.1242/dev.091744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:153–166. doi: 10.1038/nrc2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Wakeman TP, Lathia JD, Hjelmeland AB, Wang XF, White RR, Rich JN, Sullenger BA. Notch promotes radioresistance of glioma stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:17–28. doi: 10.1002/stem.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venere M, Hamerlik P, Wu Q, Rasmussen R, Song LA, Vasanji A, Tenley N, Flavahan WA, Hjelmeland AB, Bartek J. Therapeutic targeting of constitutive PARP activation compromises stem cell phenotype and survival of glioblastoma-initiating cells. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:258–269. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhat KP, Balasubramaniyan V, Vaillant B, Ezhilarasan R, Hummelink K, Hollingsworth F, Wani K, Heathcock L, James JD, Goodman LD. Mesenchymal differentiation mediated by NF-kappaB promotes radiation resistance in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:331–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chalmers AJ. Radioresistant glioma stem cells—therapeutic obstacle or promising target? DNA Repair. 2007;6:1391–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldhoff P, Clarke J, Smirnov I, Berger MS, Prados MD, James CD, Perry A, Phillips JJ. Clinical stratification of glioblastoma based on alterations in retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (RB1) and association with the proneural subtype. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:83–89. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31823fe8f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costello JF, Plass C, Arap W, Chapman VM, Held WA, Berger MS, Su Huang HJ, Cavenee WK. Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (CDK6) amplification in human gliomas identified using two-dimensional separation of genomic DNA. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1250–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He J, Olson JJ, James CD. Lack of p16INK4 or retinoblastoma protein (pRb), or amplification-associated overexpression of cdk4 is observed in distinct subsets of malignant glial tumors and cell lines. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4833–4836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abukhdeir AM, Park BH. P21 and p27: roles in carcinogenesis and drug resistance. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2008;10:e19. doi: 10.1017/S1462399408000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen L, Besson A, Heng JI, Schuurmans C, Teboul L, Parras C, Philpott A, Roberts JM, Guillemot F. p27kip1 independently promotes neuronal differentiation and migration in the cerebral cortex. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1511–1524. doi: 10.1101/gad.377106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alleyne CH, Jr., He J, Yang J, Hunter SB, Cotsonis G, James CD, Olson JJ. Analysis of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors in malignant astrocytomas. Int J Oncol. 1999;14:1111–1116. doi: 10.3892/ijo.14.6.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]