Abstract

Sec1/Munc18 (SM) proteins are involved in various intracellular membrane trafficking steps. Many SM proteins bind to appropriate syntaxin homologues involved in these steps, suggesting that SM proteins function as syntaxin chaperones. Organisms with mutations in SM genes, however, exhibit defects in either early (docking) or late (fusion) stages of exocytosis, implying that SM proteins may have multiple functions. To gain insight into the role of SM proteins, we introduced mutations modeled on those identified in Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae into mammalian Munc18-1. As expected, several mutants exhibited reduced binding to syntaxin1A. However, three mutants displayed wild-type syntaxin binding affinities, indicating syntaxin-independent defects. Expression of these mutants in chromaffin cells either increased the rate and extent of exocytosis or altered the kinetics of individual release events. This latter effect was associated with a reduced Mint binding affinity in one mutant, implying a potential mechanism for the observed alteration in release kinetics. Furthermore, this phenotype persisted when the mutation was combined with a second mutation that greatly reduced syntaxin binding affinity. These results clarify the data on the function of SM proteins in mutant organisms and indicate that Munc18-1 controls multiple stages of exocytosis via both syntaxin-dependent and -independent protein interactions.

INTRODUCTION

Movement of transport vesicles and their fusion with target membranes occurs throughout the cell. Secretory vesicles must dock with the acceptor membrane and undergo a priming process before proceeding to fusion (Burgoyne and Morgan, 2003). The fusion process itself is thought to be mediated by the formation of a complex of proteins known as soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) (Sollner et al., 1993; Weber et al., 1998), which are required for membrane fusion throughout the secretory and endocytic pathways. Regulated exocytosis in neurons requires the SNARE proteins syntaxin1, synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa, and vesicle-associated membrane protein/synaptobrevin (Jahn and Sudhof, 1999), but although these proteins are sufficient for fusion in vitro (Weber et al., 1998), it is unlikely that they provide all of the specificity and control necessary to maintain cellular compartmentalization.

The Sec1/Munc18 (SM) proteins also operate throughout the secretory pathway and at the cell membrane in both regulated and constitutive exocytosis (Jahn, 2000). First identified in genetic screens for uncoordinated mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans (UNC-18) (Brenner, 1974) and secretion mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sec1) (Novick and Schekman, 1979), homologues have since been identified in many organisms. Indeed, genetic studies have established a general requirement for SM genes in membrane fusion in a variety of organisms, including yeast (SEC1, SLY1, VPS33, and VPS45), plants (KEULE), nematodes (unc-18), flies (ROP), and mice (Munc18-1) (Halachmi and Lev, 1996; Verhage et al., 2000; Assaad et al., 2001). Although most work has focused on exocytosis, the general role of SM proteins in membrane fusion is illustrated by their requirement for endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-Golgi transport (Sly1) and transport to the vacuole (Vps33 and Vps45) in yeast (Halachmi and Lev, 1996). SM proteins from a variety of organisms have been shown to interact with syntaxin homologues, suggesting that the conserved function of SM proteins in membrane fusion may be mediated via syntaxins (Jahn, 2000). Indeed, the yeast syntaxins Sso1 and Sso2 act as multicopy suppressors of sec1-1 mutants (Aalto et al., 1993), and the inhibition of neurotransmitter release in Drosophila caused by overexpression of ROP is relieved by cooverexpression of syntaxin (Wu et al., 1998), thus supporting this notion. Furthermore, mammalian Munc18-1 binds to syntaxin1A in the closed conformation with nanomolar affinity to form a complex that prevents syntaxin from entering the synaptic SNARE complex (Pevsner et al., 1994; Dulubova et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2000). These observations have led to the suggestion that Munc18-1 acts as a syntaxin chaperone, preventing SNARE complex assembly until signaled to release syntaxin (Jahn, 2000).

The idea that Munc18-1 functions simply as an inhibitor of SNARE complex formation and thus of exocytosis is, however, difficult to reconcile with the positive requirement for SM proteins found in many systems. For example, yeast sec1 mutants exhibit a temperature-sensitive block in exocytosis (Novick and Schekman, 1979; Novick et al., 1980), and a single amino acid substitution in another yeast SM protein, Sly1p, is equally lethal (Dascher et al., 1991). Similarly, neurotransmission is reduced in both C. elegans unc-18 (Hosono et al., 1992) and Drosophila rop (Harrison et al., 1994) mutants; and Munc18-1 knockout mice exhibit a complete abolition of both spontaneous and evoked neurotransmitter release (Verhage et al., 2000). Furthermore, the inability of constitutively open syntaxin mutants to rescue the neurotransmission defect in unc-18 mutants (Weimer et al., 2003) strongly argues that the function of SM proteins in exocytosis is not solely to regulate the conformational state of syntaxin. The notion that SM proteins may play more than one role in the vesicle transport process is supported by studies in diverse organisms. In yeast, for example, the genetic interaction between Sly1 and the Rab-like GTPase Ypt1 (Dascher et al., 1991; Ossig et al., 1991) suggests an involvement in the early event of vesicle recruitment; whereas Sec1 acts at a very late stage in membrane fusion, downstream of SNARE complex assembly (Carr et al., 1999; Grote et al., 2000). A role for SM proteins in docking is suggested by the reduced numbers of docked synaptic vesicles in C. elegans unc-18 mutant synapses (Weimer et al., 2003) and a similar reduction in docked dense-cored granules in chromaffin cells from Munc18-1 knockout mice (Voets et al., 2001). Strikingly, however, in the same knockout mice there is no effect on synaptic vesicle docking despite a complete block of neurotransmission (Verhage et al., 2000), suggesting an additional postdocking role for Munc18-1 in the late stages of membrane fusion. The alterations in exocytotic release kinetics induced by expression of Munc18-1 mutants in chromaffin cells are consistent with such a late-acting role, suggesting that Munc18-1 may regulate fusion pore expansion (Fisher et al., 2001; Barclay et al., 2003).

Clearly, the putative multiple roles of Munc18-1 in exocytosis may not be due to the interaction with syntaxin alone. Recently, attention has been drawn to other proteins implicated in exocytosis that bind to Munc18-1. Granuphilin, a protein identified in pancreatic β cells that associates with dense core granules, has been shown to bind Munc18-1, Rab3, and Rab27A (Coppola et al., 2002; Fukuda et al., 2002), providing a potential mechanism for the modulation of Munc18-1 function through Rab activity. Doc2 proteins, which copurify with synaptic vesicles, also bind to Munc18-1 in competition with syntaxin and have been suggested to act as adaptors to regulate the Munc18-1-syntaxin interaction during vesicle docking (Verhage et al., 1997). The proteins Mint 1 and Mint 2 were detected in brain in a complex with syntaxin and Munc18-1 (Okamoto and Sudhof, 1997) and may function in recruiting Munc18-1 to neurexin-containing regions of the plasma membrane via an association with the protein CASK (Biederer and Sudhof, 2000). Because granuphilin (Coppola et al., 2002; Fukuda et al., 2002), Doc2 (Orita et al., 1996), and Mints (Ho et al., 2003) have all been implicated in the regulation of exocytosis, it may be that some functions of Munc18-1 are dependent upon these interactions, although there is no direct evidence to support this at present.

One explanation for the contrasting exocytosis phenotypes exhibited by SM mutant organisms is that different mutations preferentially affect binding to individual binding proteins, leading to an effect at only one stage of exocytosis. We wished to test this hypothesis by analyzing the effects of various known missense mutations on the biochemical and functional properties of Munc18-1. Many of the mutations characterized in these organisms can be mapped on to conserved residues in Munc18-1, thus facilitating this approach (Table 1). We therefore created mutations in Munc18-1 based on those previously characterized in rop (Harrison et al., 1994; Wu et al., 1998) and unc-18 (Sassa et al., 1999) and also a mutation designed to mimic the sly1-20 allele (Dascher et al., 1991; Ossig et al., 1991). The binding of these mutants to syntaxin1A and to other Munc-18-1-binding proteins revealed striking differences, with several mutants retaining wild-type syntaxin-binding levels. Furthermore, the latter mutations produced distinct effects on the early and late stages of exocytosis, suggesting that the multiple roles of Munc18-1 in exocytosis are determined not only by syntaxin but also by nonsyntaxin protein interactions.

Table 1.

SM mutations and their equivalents in Munc18-1

The characteristics of various missense mutant alleles of SM genes are shown along with the mutations engineered in rat Munc18-1

| Organism and mutant allele | Phenotype in original organism | Mutated residue | Mutation in Munc18-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| D. melanogaster ropG11 | Reduced evoked and spontaneous neurotransmission | D45N | D34N |

| D. melanogaster ropG17 | Enhanced evoked neurotransmission | P253S | P242S |

| D. melanogaster ropA19 | Reduced evoked and spontaneous neurotransmission | H302Y | H293Y |

| C. elegans unc-18(b403) | Severe locomotion defect | E549K | E549K |

| C. elegans unc-18(md1401) | Mild locomotion defect | I133V | I133V |

| S. cerevisiae sly1-20 | By-passes requirement for Ypt1 in ER-to-Golgi transport | E532K | E466K |

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vector Construction and Protein Expression

Plasmids were constructed in pCDNA3.1(-) for expression in chromaffin cells and pGex6P-1 for the production of glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fusion proteins. Single mutations (D34N, I133V, P242S, H293Y, E466K, and E549K) were introduced into wild-type Munc18-1 by site-directed mutagenesis by using the four-primer polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method. The mutations R39C (Fisher et al., 2001) and double mutation S306E/S313E (dGLU) (Barclay et al., 2003) were introduced using the QuikChange system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The combined R39C/P242S double mutant was created by subcloning fragments from each single mutant. Bacterial expression of GST-fusion proteins was carried out as follows. A 1l culture of Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) containing a pGEX6P-1-based expression plasmid was grown at 30°C in Terrific broth containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 50 μg/ml chloramphenicol to an OD600 of 1 before adding 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside and allowing protein induction to proceed overnight at the same temperature. The cells were harvested; lysed by sonication in 40 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 1% Triton (TX)-100, 2 mM EDTA, and complete protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN); and the lysate was subjected to centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was mixed with 1 ml of glutathione-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences, Piscat-away, NJ) and incubated for 2 h before pouring into a column and washing with 20 ml of PBS, 0.1% TX-100 followed by 30 ml of PBS. The protein was eluted with 5 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, and 10 mM glutathione and dialyzed against PBS.

Protein Binding Assays

Wild-type and mutant Munc18-1 proteins, Mint 2 residues 185-271 (Mint 2 MBD), and granuphilin A were produced in radiolabeled form by in vitro transcription/translation with the TnT T7 quick for PCR DNA system (Promega, Madison, WI) by using PCR template amplified from plasmids encoding the relevant proteins. Proteins were tested for solubility after production by using this method by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min. Binding of Munc18-1 proteins to GST-syntaxin in the presence of unlabeled wild-type Munc18-1 was carried out as described previously (Barclay et al., 2003). Binding assays between radiolabeled Munc18-1 and GST-syntaxin were performed using glutathione-coated multiwell plates (Craig et al., 2004), and kinetic constants were calculated as described previously (Weiland and Molinoff, 1981). Binding of radiolabeled Munc18-1 to Gst-Mint 2 and GST-Mint 1 residues 226-314 (Mint 1 MBD), binding of GST-Munc18-1 to radiolabeled Mint 2 MBD, and binding of GST-Munc18-1 to radiolabeled granuphilin A was performed essentially as described previously (Craig et al., 2004), except that 20 μg of the GST-fusion proteins were used, and the binding reaction was carried out either in 10 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.25% TX-100, 3.5 mM CaCl2, and 3.5 mM MgCl2 for Mint proteins or in 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 5% glycerol, 0.05% Tween 20, and 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin for granuphilin A.

Expression of Plasmids in HeLa Cells

HeLa cells were transfected with 1 μg of pcDNA3.1 (control) or a Munc18-1 plasmid by using 3 μl of FuGENE transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics). After 72 h, the cells were lysed in 200 μl of SDS sample buffer.

Cell Culture and Transfection of Chromaffin Cells

Freshly isolated bovine adrenal chromaffin cells were plated onto nontissue culture-treated 10-cm Petri dishes and left overnight at 37°C. Nonattached cells were resuspended in fresh growth medium at a density of 1 × 107 cells/ml. Plasmid constructs encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) and either the appropriate Munc18-1 mutant or Mint1 were mixed and added to the chromaffin cell suspension at 20 μg/ml. Cells were electroporated using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), immediately diluted to 1 × 106 cells/ml, and maintained in culture for 3-5 d

Immunofluorescence

Chromaffin cells were transfected as described above and plated onto glass coverslips. After washing with PBS twice, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 30 min. Fixed cells were subsequently probed with a polyclonal antibody against Munc18-1 (Cambridge Biosciences, Cambridge, United Kingdom) at a concentration (1:100) that is suboptimal for the detection of endogenous levels of Munc18-1 in chromaffin cells. Staining was visualized using a Leica laser scanning confocal microscope by using 488-nm excitation and 500- to 550-nm light collection for EGFP and 543-nm excitation and 600- to 650-nm light collection for Texas Red. For quantification of fluorescence, the cell area was defined and the Texas Red signal quantified using the Leica confocal software for transfected and nontransfected cells in the same microscope field. At least 10 cells were imaged and quantified for each condition.

Sample Preparation for Western Blotting

Total bovine brain extract was prepared by homogenizing 20 g of bovine brain in buffer A (10 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 100 mg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) before adding Triton X-100 to a final concentration of 1% and mixing for 4 h at 4°C. The extract was cleared by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min, resuspended in SDS sample buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and boiled. Chromaffin cell and HeLa cell extracts were prepared by boiling cultured cells in SDS sample buffer. Samples were run on SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with appropriate antisera before visualization by enhanced chemiluminescence. Detection of proteins in transfected HeLa cells used monoclonal antibodies against Munc18-1 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and hsc70 (Sigma-Aldrich). Detection of Mint 1 in chromaffin cell and brain extracts was carried out using a commercial antibody to Mint 1 purchased from BD Biosciences.

Amperometric Recording

Electrophysiological recording conditions were as described previously (Graham et al., 2000; Barclay et al., 2003). Briefly, cells were incubated in bath buffer (139 mM potassium glutamate, 0.2 mM EGTA, 20 mM PIPES, 2 mM ATP, and 2 mM MgCl2, pH 6.5), and a 5-μm-diameter carbon fiber was positioned in contact with the target cell. Exocytosis was stimulated with a permeabilization/stimulation buffer (139 mM potassium glutamate, 20 mM PIPES, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM ATP, 2 mM MgCl2, 20 μM digitonin, and 10 μM free Ca2+, pH 6.5) pressure-ejected from a glass pipette on the opposite side of the cell. Amperometric responses were monitored with a VA-10 amplifier (NPI Electronic, Tamm, Germany) and saved to computer using Axoscope 8 (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Experiments were carried out in parallel on control (untransfected cells) and transfected cells from the same batch of cells in the same cell culture dishes. Transfected cells were identified by expression of EGFP. Previous studies have established that 95% of cells coexpress proteins from both plasmids in the transfection (Graham et al., 2000). Recordings of both control and transfected cells used the same carbon fibers to eliminate any potential effects of interfiber variability.

Data Analysis

Amperometric data were exported from Axoscope and analyzed using Origin (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Amperometric spikes were selected for analysis provided that the spike amplitude exceeded 40 pA, to remove any confounding effects of diffusion by selecting those fusion events not occurring directly beneath the carbon fiber end. Individual spikes were analyzed for total charge released (measured by the integral of the spike), amplitude (the height from baseline to peak), rise time (time from spike onset to peak), and fall time (time from spike peak to return to baseline). Spike frequency (spikes per cell) was calculated as the number of exocytotic events within the 210 s of recording time. Spike feet were defined from foot onset (the time at which the amperometric current rose 2.5× above noise level) to spike onset (the time at which the amperometric spike began, determined by the differentiation of the amperometric trace). All data presented are shown as mean ± SEM or as a boxplot of median values (feet parameters). Statistical differences were assessed with nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests.

RESULTS

Some Munc18-1 Mutations Do Not Affect Binding to GST-tagged Syntaxin

To shed light on the role(s) of Munc18-1 in exocytosis, missense mutations identified as functionally impaired in the D. melanogaster (ropG11, ropG17, and ropA19) and C. elegans [unc-18(b403)] SM genes were introduced in the homologous residues of rat Munc18-1 (Table 1). A further mutation, I133V, was created, which confers the same I-V substitution found in the C. elegans unc-18(md1401) mutant, but at an isoleucine located two amino acids from the homologous Munc18-1 residue. In addition, a mutation, E466K, which was considered to correspond to the sly1-20 mutation in S. cerevisiae also was created: this mutation was designed on the basis of the sequence and structure-based alignment of squid neuronal Sec1 and rat Munc18-1 reported by Bracher et al. (2000) in which E466 (rat) and E468 (squid) were aligned and were suggested to correspond to E532 of yeast Sly1. This Sly1 residue is mutated to K in the sly1-20 allele, which suppresses the requirement for the function of the Ypt1 Rab protein in yeast ER-Golgi traffic. However the subsequent publication of the three-dimensional structure of yeast Sly1 (Bracher and Weissenhorn, 2002) has revealed that the sly1-20 mutation lies within a Sly1 surface loop that has no equivalent in rat Munc18-1, corresponding to a highly variable region of SM proteins. Although E466K is therefore not a precise mimic of the sly1-20 mutation, it is nevertheless a residue that is conserved in SM proteins (including yeast Sec1p) and that lies in a surface loop on the surface of domain III in both squid Sec1 and rat Munc18-1. Furthermore, as pointed out by Bracher and Weissenhorn (2002), it also lies within the sequence of a peptide that was found to inhibit neurotransmitter release when injected into the presynaptic terminal of the squid giant synapse (Dresbach et al., 1998). The residue numbers in the original organisms and those mutated in Munc18-1 are listed in Table 1.

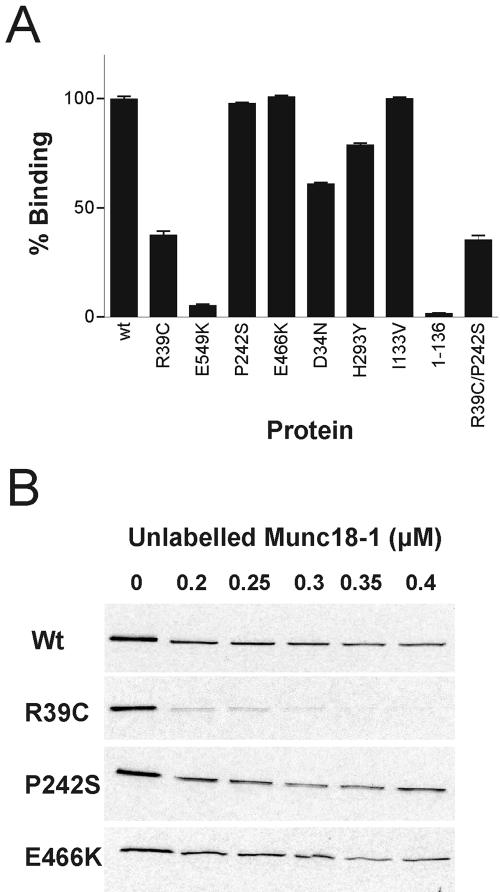

To gain insight into the biochemical defects in the various mutant proteins, their binding to known Munc18-1 binding proteins was investigated. Because the best characterized interaction of Munc18-1 is with syntaxin1A, the binding of radiolabeled wild-type and mutant Munc18-1 proteins to the cytoplasmic domain of syntaxin1A (GST-syntaxin) was measured and compared with wild-type Munc18-1, to a previously characterized mutation (R39C) known to have reduced syntaxin binding (Fisher et al., 2001) and to domain I of Munc18-1 alone, which has negligible binding affinity for syntaxin1A (Figure 1A). E549K showed drastically impaired binding to syntaxin similar to domain I alone. D34N and H293Y showed reduced binding to syntaxin, although they bound better than R39C. The reduced binding of these mutants to GST-syntaxin suggests that the functional defect detected in the original rop and unc-18 mutants is likely to be due to reduced binding between the SM protein and the corresponding syntaxin.

Figure 1.

Binding of mutant Munc18-1 proteins to GST-syntaxin1A. (A) Radiolabeled Munc18-1 wild-type and mutant proteins (including domain I residues 1-136) were bound to GST-syntaxin1A immobilized on a glutathione 96-well plate. The amount of each protein bound to GST-syntaxin was quantified by liquid scintillation. (B) Radiolabeled Munc18-1 wild-type and mutant proteins were bound to glutathione-agarose in the presence of increasing concentrations of unlabeled wild-type Munc18-1. Bound radiolabeled protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by exposure to 35S-sensitive film.

In contrast, binding of the P242S, I133V, and E466K mutant proteins to syntaxin1A was similar to wild-type Munc18-1 (Figure 1A). P242S and E466K were analyzed further by assaying binding to GST-syntaxin in the presence of additional competing wild-type His-tagged Munc18-1 (Figure 1B). In this competition assay, R39C, which binds GST-syntaxin1A poorly, is easily displaced from syntaxin in the presence of wild-type Munc18-1 at a concentration of 0.2 μM. In contrast, P242S and E466K are still found bound to syntaxin even in the presence of wild-type Munc18-1 at 0.4 μM, which is comparable with the behavior of wild-type Munc18-1 in this assay. As a further test of the syntaxin-binding behavior of these Munc18-1 proteins, preequilibrium binding to and dissociation from syntaxin were analyzed (Craig et al., 2004) and the constants k1, k-1, and Kd calculated from the binding measurements (Table 2). All the calculated constants were similar to wild type, again confirming that the Munc18-1 mutations P242S and E466K do not cause a major defect in binding to GST-syntaxin. In contrast, it was impossible to calculate such constants for R39C in these experiments because the mutant had such a fast off-rate.

Table 2.

Binding affinity constants for the interaction of Munc18-1 and GST-syntaxin1A

| Protein | k1 | k−1 | Kd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nM−1s−1 | nM | |||

| wt | 1.1×10−2 | 8.5×10−3 | 0.8 | |

| P242S | 6.3×10−3 | 1.2×10−2 | 1.9 | |

| E466K | 7.8×10−3 | 9.5×10−3 | 1.2 | |

Preequilibrium binding measurements were made for the binding between Munc18-1 wild-type (wt) and mutant proteins and GST-syntaxin1A by using a glutathione-coated 96-well plate assay. Kinetic and binding affinity constants were calculated from the time course of binding and dissociation measured.

Binding of Munc18-1 Mutants to Mint 1, Mint 2, Doc2, and Granuphilin

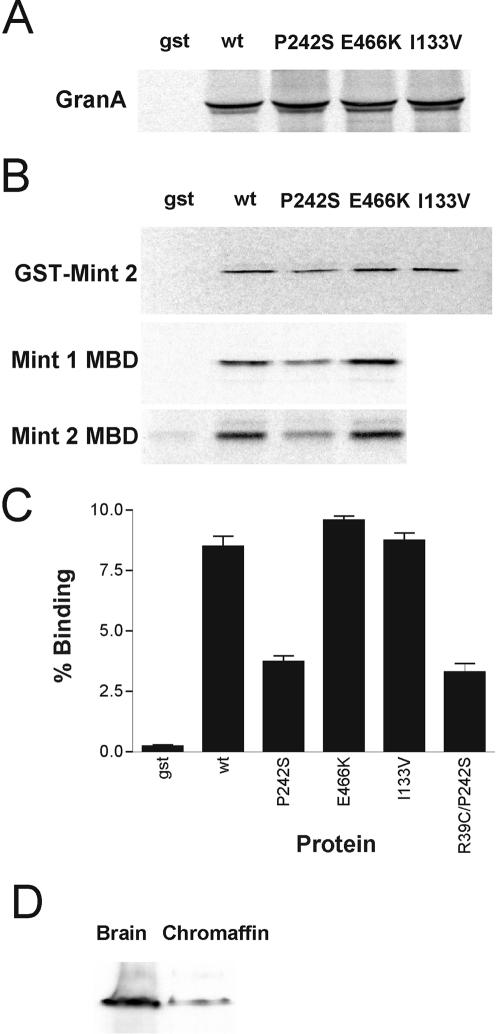

Munc18-1 has been shown to interact with the Mint1 and Mint2 proteins, as well as Doc2B and granuphilin A. The binding of I133V, P242S, and E466K to these was tested to ascertain whether these mutations confer a defect in any of these interactions. Unfortunately, despite using various approaches, including pull-down assays with total bovine brain extract and direct binding assays by using in vitro-translated proteins, we were unable to reproduce the reported binding of Munc18-1 to Doc2. In contrast, binding of GST-tagged Munc18-1 to radiolabeled granuphilin A was readily detected, whereas GST alone exhibited negligible binding (Figure 2A). However, all three mutant proteins showed a similar level of binding to wild-type Munc18-1, suggesting that the functional impairment of these mutants is unlikely to be due to a change in granuphilin binding. GST-tagged constructs encoding full-length Mint2 (GST-Mint2) and the Munc18-1 binding domains from both Mint1 and Mint2 (Mint1 MBD and Mint2 MBD) were used to test binding of radiolabeled Munc18-1 proteins. Munc18-1 wild-type and the I133V and E466K mutants bound all the Mint constructs to the same extent, but P242S showed reduced binding to both full-length GST-Mint2 and to the Mint1 MBD and Mint2 MBD (Figure 2B). The binding of the Munc18-1 proteins to GST-Mint2 was quantified using a 96-well plate-based assay (Craig et al., 2004), and P242S was shown to be reduced by >50% compared with wild type, whereas I133V and E466K exhibited wild-type levels of binding (Figure 2C). It is therefore a possibility that the phenotype observed in the original ropG17 mutation was due, at least in part, to a defect in the interaction between the SM and the Mint proteins, although it cannot be ruled out that the reduced binding to Mints is part of a more complex defect involving other proteins as well as Mints. However, pull-down assays from brain extracts by using wild-type or P242S GST-Munc18-1 revealed no obvious differences in the levels of various other bound proteins as detected by immunoblotting (our unpublished data). Because our functional tests of these mutations were to be carried out in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells and evidence of Mint proteins in this tissue was not available, we probed extracts of these cells with antibodies to both Mint proteins. Mint1 is clearly present in chromaffin cells although the levels are lower than in brain (Figure 2D). We were unable to detect Mint2 by blotting in chromaffin cells, but gene expression profiling of a variety of tissues from human and mouse (Su et al., 2002) indicates that Mint2 is expressed in adrenal gland at a similar order of magnitude to Mint1.

Figure 2.

Binding of Munc18-1 mutants to granuphilin A and Mints 1 and 2. (A) Radiolabeled granuphilin A was bound to GST-Munc18-1 wild-type and mutant proteins, immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose with GST alone as a negative control. (B) Radiolabeled Munc18-1 wild-type and mutant proteins were bound to GST, GST-Mint 2, and GST-Mint1 residues 226-314 immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose. Radiolabeled Mint2 residues 185-271 was bound to immobilized GST or GST-Munc18-1 proteins. (C) Radiolabeled Munc18-1 wild-type and mutant proteins were bound to GST or GST-Mint2 immobilized on a glutathione-coated 96-well plate. Bound material was eluted with glutathione and quantified with liquid scintillation counting. (D) Extracts of bovine brain and chromaffin cells were analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of Mint 1.

Munc18-1 Mutants That Do Not Affect Syntaxin Binding Are Overexpressed in Transfected Cells

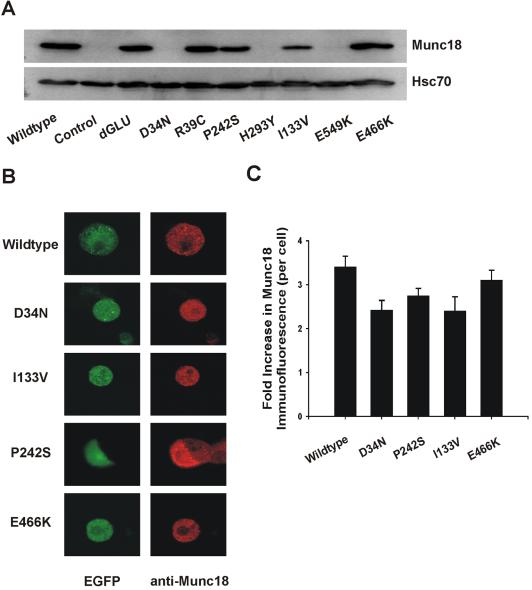

To ensure that the mutated Munc18-1 proteins would be expressed in mammalian cells, individual mutant Munc18-1 plasmids were transfected into HeLa cells and the extent of protein expression was assayed by Western blotting (Figure 3A). Protein levels were compared with expression of the wild-type protein, transfection of an empty plasmid (control), and two previously described Munc18-1 mutations (dGLU and R39C). D34N, H293Y, and E549K were not expressed at all, but P242S and E466K were expressed to a level comparable with the wild-type protein and the R39C and dGLU mutants. The I133V mutant protein was expressed, albeit at a lower level than wild-type protein. These variations were not due to gel-loading artifacts, because similar levels of hsc70 were present in all samples (Figure 3A). We also coexpressed these mutated proteins in adrenal chromaffin cells with GFP and determined coexpression by immunofluorescence (Figure 3B). As expected, the Munc18-1 mutants that were expressed in HeLa cells all showed overexpression of the Munc18-1 protein in chromaffin cells; although, surprisingly, D34N, which is not expressed in HeLa cells, also was expressed in chromaffin cells. Examination of confocal images of the various mutants revealed no obvious difference in localization arising as a result of the mutations (Figure 3B). To determine the relative extent of overexpression of each construct in chromaffin cells, quantitative confocal microscopy was used, because the transfection efficiency of chromaffin cells is too low to enable quantification via Western blotting. This analysis revealed very similar extents of overexpression of both wild-type and mutant constructs relative to endogenous Munc18-1 levels (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Expression of Munc18-1 mutants in mammalian cells. (A) Wild-type and mutant Munc18-1 constructs were transfected into HeLa cells and expression detected by Western blotting by using a monoclonal Munc18-1 antibody (top). The observed differences in expression were not due to loading differences, because the level of an endogenous protein standard, Hsc70, was similar in all cases (bottom). Control cells were transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3). (B) Mutant Munc18-1 constructs were cotransfected along with an EGFP reporter plasmid into bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Expression of Munc18-1 was detected by immunofluorescence by using a polyclonal Munc18-1 antibody, whereas EGFP expression was monitored by endogenous fluorescence. Confocal sections are shown to illustrate the similar localizations of the various recombinant proteins. (C) Relative extent of expression of wild-type and mutant Munc18-1 constructs was determined by quantifying the immunofluorescence intensity of Munc18-1 in transfected cells compared with that of endogenous Munc18-1 in nontransfected control cells.

Mutants P242S and I133V Alter Amperometric Spike Parameters in Chromaffin Cells

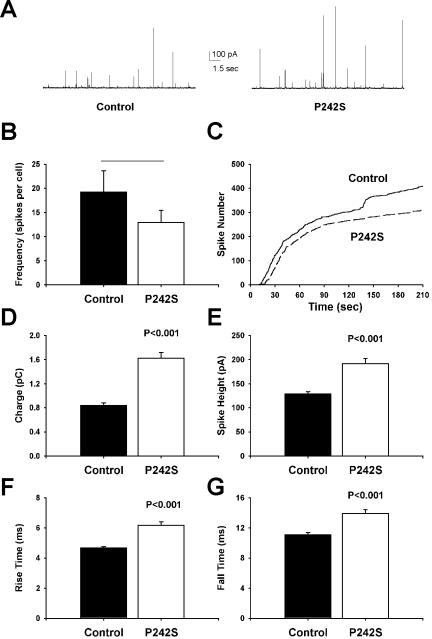

We expressed P242S and I133V in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells and assayed secretion by carbon fiber amperometry. After stimulation with digitonin and calcium, transient spikes of catecholamine oxidation were recorded, indicative of individual dense core granule fusion events (Figure 4A). P242S had no obvious effects on the early stages of exocytosis because the frequency (Figure 4B) and time course (Figure 4C) were not different in comparison with control (untransfected) cells in the same dishes. The P242S mutant, however, did affect the individual fusion events, causing a 93% increase in amperometric charge (Figure 4D), indicative of a larger quantal size. Similarly, the individual spike amplitudes were increased (Figure 4E). The kinetics of each release event also was significantly slowed. Amperometric spikes from P242S-transfected cells had both a longer rise time (Figure 4F) and fall time (Figure 4G) in comparison with control spikes. Similar effects, i.e., changes to the same amperometric kinetic parameters but no effect on the frequency of exocytotic events, also were observed upon ex-pression of I133V (Supplementary Data Figure 1). These effects were specific to these particular Munc18-1 mutations, because cells transfected with D34N, H293Y, or E549K showed no significant differences in amperometric spike parameters in comparison with controls (our unpublished data).

Figure 4.

Expression of the Munc18-1 P242S mutant in chromaffin cells increases quantal size and slows release kinetics. (A) Typical amperometric responses from untransfected cells (left) or cells transfected with the Munc18-1 P242S mutant (right) after addition of digitonin and Ca2+ to elicit exocytosis. (B and C) Analysis of the frequency of exocytotic fusion events (amperometric spikes, B) and the time course of exocytosis (C) reveals no significant difference between control and transfected cells. (D-G) Expression of Munc18-1 P242S increases quantal size (charge, D; spike height, E) and slows the kinetics of release by increasing both the rise time (F) and fall time (G) of individual amperometric spikes. Data were analyzed from 422 spikes from 22 cells (control) and 311 spikes from 24 cells (P242S).

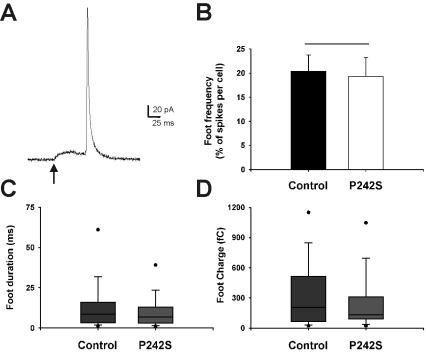

Before the amperometric spike itself, a prespike deflection termed an amperometric foot can be seen in a measurable population of fusion events. The foot is purported to represent the steady-stage flux of neurotransmitter through the transient fusion pore before full fusion. Amperometric feet could be identified before spikes from cells overexpressing P242S (see Figure 5A, for example) and from untransfected cells, although at a frequency of only ∼20% (Figure 5B). There was no effect of the P242S mutation on the numbers of spikes that have measurable preceding feet in comparison with controls. Further examination revealed that the mutation also did not affect the parameters of the foot. Both the duration (Figure 5C) and the total charge (Figure 5D) of the amperometric feet were statistically identical in untransfected and P242S spikes, indicating that initial neurotransmitter release through the fusion pore was unaffected by this mutation in Munc18-1.

Figure 5.

Expression of the Munc18-1 P242S mutant in chromaffin cells has no effect on amperometric foot parameters. (A) Typical example traces of amperometric spike feet. The foot (onset indicated by an arrow) is a small increase in measurable current preceding the full spike deflection, representing flux of catecholamine through the fusion pore. (B-D) There were no significant differences in foot frequency (the ratio of numbers of feet to numbers of exocytotic events per cell, B), foot duration (C), or foot charge (the amount of catecholamine released during the foot, D) between control and transfected cells. Feet were analyzed from the same spike data presented in Figure 4. The box plots shown illustrate the spread of the nonparametric data, where the middle line of the box represents the median, the top and bottom of the box represent the 25 and 75 percentiles, and the dots represent the 10 and 90 percentiles.

Because P242S showed reduced binding for Mint1 compared with wild-type, and because Mint1 is expressed in adrenal chromaffin cells, we investigated whether overexpression of the Mint1 protein would have an effect on individual fusion events assayed with carbon fiber amperometry. However, expression of the Mint1 protein had no significant effect on either the frequency of exocytotic events or on spike kinetics (our unpublished data). To ensure that this was not due to isoform differences, the Mint2 protein also was tested, and a similar lack of effect was found (our unpublished data).

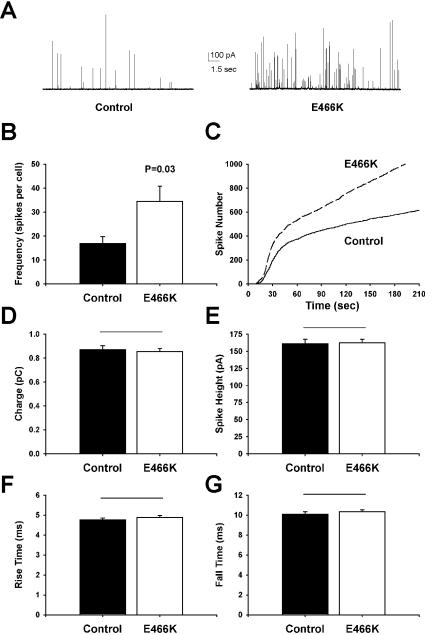

Mutant E466K Increases Amperometric Spike Frequency in Chromaffin Cells

The E466K mutant protein was expressed in chromaffin cells, and the resultant exocytotic events were again monitored by carbon fiber amperometry (Figure 6A). In pointed contrast to the phenotypes of P242S and I133V, E466K increased the frequency of fusion events (Figure 6B) and increased the rate of fusion events at later times (Figure 6C), pointing to a stimulatory effect on vesicle recruitment. There were no effects of the E466K mutation on any parameters of the late stages of vesicle release; amperometric charge (Figure 6D), spike height (Figure 6E), rise time (Figure 6F), and fall time (Figure 6G) were all statistically identical in comparison with untransfected controls. This increase in the rate and extent of exocytosis suggests that the E466K mutation acts at an early phase to increase the recruitment of granules for subsequent fusion.

Figure 6.

Expression of the Munc18-1 E466K mutant in chromaffin cells increases the rate and extent of exocytosis. (A) Typical amperometric responses from untransfected cells (left) or cells transfected with the Munc18-1 E466K mutant (right) after addition of digitonin and Ca2+ to elicit exocytosis. (B and C) Analysis of the frequency of exocytotic fusion events (amperometric spikes, B) and the time course of exocytosis (C) reveals that E466K expression induces an increased number of exocytotic events at all time points. (D-G) Expression of Munc18-1 E466K has no effect on either quantal size (charge, D; spike height, E) or the kinetics of release (rise time, F; fall time, G) of individual amperometric spikes. Data were analyzed from 625 spikes from 37 cells (control) and 1138 spikes from 33 cells (E466K).

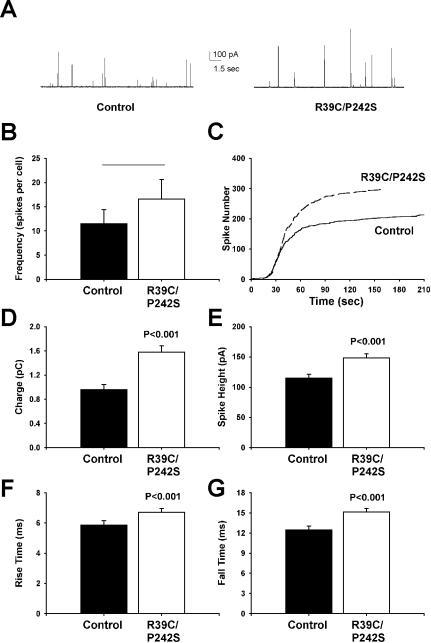

The Effect of P242S on Amperometric Spike Parameters Does Not Require Syntaxin Binding

Although the P242S mutant had no defect in syntaxin binding, it remained possible that its effect on the late stages of exocytosis was nevertheless dependent on this interaction. To address this issue, we introduced the R39C mutation, which reduces the affinity of Munc18-1 for syntaxin1A (Fisher et al., 2001), into the P242S construct to create a combined R39C/P242S double mutant. As expected, this double mutant closely mimicked the behavior of the single R39C mutant in having a similarly reduced affinity for syntaxin1A (Figure 1A). In addition, the double mutant displayed a very similar reduction in Mint binding to the single P242S mutant (Figure 2C). Therefore, the R39C/P242S mutant provided an ideal tool to test whether the effect of the single P242S mutation on exocytosis required high-affinity syntaxin binding. As shown in Figure 7, the effect of this double mutant in increasing quantal size and slowing release kinetics was virtually identical to that of the single p242S mutant (Figure 4). Because this effect persisted despite the reduced syntaxin binding affinity of the double mutant, this strongly suggests that Munc18-1 can affect the late stages of membrane fusion in a syntaxin-independent manner.

Figure 7.

Expression of a combined R39C/P242S Munc18-1 double mutant in chromaffin cells has the same effect as the single P242S mutant. (A) Typical amperometric responses from untransfected cells (left) or cells transfected with the Munc18-1 R39C/P242S mutant (right) after addition of digitonin and Ca2+ to elicit exocytosis. (B and C) Analysis of the frequency of exocytotic fusion events (amperometric spikes, B) and the time course of exocytosis (C) reveals no significant difference between control and transfected cells. (D-G) Expression of Munc18-1 R39C/P242S increases quantal size (charge, D; spike height, E) and slows the kinetics of release by increasing both the rise time (F) and fall time (G) of individual amperometric spikes. Data were analyzed from 218 spikes from 19 cells (control) and 298 spikes from 18 cells (R39C/P242S).

DISCUSSION

Syntaxin-dependent Functions of Munc18-1 in Exocytosis

A general feature of SM proteins is their binding to cognate syntaxins involved in the same membrane-trafficking process, although the actual mechanism of binding varies widely between family members (Gallwitz and Jahn, 2003). Consequently, it has become accepted that the putative conserved function of SM proteins, although presently unclear, is likely to be intimately connected to conformational changes in syntaxin (Jahn, 2000). Indeed, yeast Vps45 functions in a chaperone-like role to stabilize the syntaxin homologue Tlg2 and to facilitate its entry into the SNARE complex (Bryant and James, 2001). Further support comes from the observation that the yeast syntaxins Sso1 and Sso2 act as multicopy suppressors of sec1-1 mutants (Aalto et al., 1993) and that the inhibition of neurotransmitter release in Drosophila caused by overexpression of ROP is relieved by cooverexpression of syntaxin (Wu et al., 1998). We have previously characterized two mutations in Munc18-1, R39C and dGLU, that reduce the affinity of the mutant proteins for syntaxin1A (Fisher et al., 2001; Barclay et al., 2003). Expression of both mutants in chromaffin cells results in a smaller quantal size and faster exocytotic kinetics per individual fusion event. Reciprocal experiments where syntaxin1A mutants with reduced affinity for Munc18-1 are expressed in chromaffin cells show increased quantal size and slowed release kinetics (Graham et al., 2004). Together, these findings are consistent with an important role for Munc18-syntaxin interactions at a very late stage of the membrane fusion process. In this study, we have found that mutations identified in C. elegans [unc-18(b403)] and D. melanogaster (ropG11 and ropA19) also reduce the affinity for syntaxin1A when introduced into homologous residues in mammalian Munc18-1. It is likely that these mutations mimic the effects on the worm and fly proteins because it has been previously shown that the unc-18(b403) mutation abolishes the interaction of UNC-18 with syntaxin (UNC-64) by using recombinant C. elegans proteins (Sassa et al., 1999). It may be, therefore, that the phenotypes exhibited by these mutant organisms are a result of impaired syntaxin binding. It is noteworthy that two of these mutants were not detectably expressed in mammalian cells, raising the possibility that the phenotypes could result from a lack of expression or stability of the appropriate SM protein. However, all the characterized rop missense mutants exhibit normal levels of ROP protein (Wu et al., 1998), making this explanation unlikely, at least for the Drosophila mutants.

Munc18-1 Affects the Late Stages of Dense Core Granule Exocytosis Independent of Its Interaction with Syntaxin

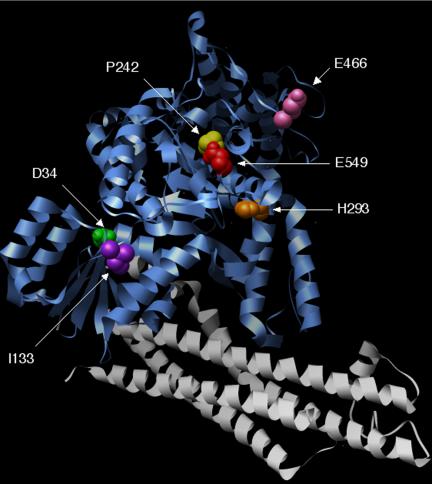

An important finding of this study is the identification of Munc18-1 mutant proteins that affect exocytosis in chromaffin cells despite having no detectable effect on the syntaxin-binding properties of Munc18-1. Distinct effects on early and late stages of exocytosis were observed with different mutants. The P242S mutation of Munc18-1 altered the late fusion parameters of exocytosis, increasing quantal size and slowing release kinetics. Drosophila larvae with the corresponding mutation (ropG17) show increased synaptic excitatory junctional potential (EJP) amplitude in comparison with wild types (Wu et al., 1998). The increased quantal size induced by Munc18-1 P242S, if mirrored in ropG17 synapses, would result in an increased level of released neurotransmitter, thus potentially explaining the observed increase in EJP amplitude. The I133V mutation of Munc18-1 affected individual spike parameters in chromaffin cells in a similar way to P242S. Although I133V is not precisely homologous to the C. elegans unc-18(md1401) mutation, it is interesting to note that the latter mutation also has no effect on the interaction of UNC-18 with syntaxin (UNC-64) by using recombinant C. elegans proteins (Sassa et al., 1999). In contrast, when the P242S mutation was introduced into mammalian Munc18-2, a reduction in syntaxin 3 binding was observed (Riento et al., 2000). It is not clear why mutation of this conserved residue causes different effects on syntaxin binding in these two Munc18 isoforms, but it may be that the mutation analyzed here is less conformationally damaging, because the mutant Munc18-1 protein retains the ability to bind both syntaxin and granuphilin. P242 is relatively inaccessible in the crystal structure of Munc18-1 (Figure 8) and so presumably does not form part of the Mint binding site. Rather, it is likely that the P242S mutation causes a change in the local conformation of the protein that in turn affects interaction of Mints with an unidentified domain(s) of Munc18-1. Nevertheless, because our data clearly show that neither the P242S nor the I133V mutations significantly alter binding of Munc18-1 to syntaxin, the phenotypic effect they have in the late stages of exocytosis cannot be due to a lack of syntaxin-binding activity. It is likely that the alterations in synaptic transmission in the original mutant organisms are also not due to a failure of the cognate SM protein to bind to the appropriate syntaxin, suggesting that nonsyntaxin protein interactions are also important for SM protein functions. Furthermore, because the effect of P242S on exocytotic release was unaltered when combined with a second mutation, R39C, that inhibits syntaxin binding, it seems reasonable to conclude that Munc18-1 can affect the late stages of membrane fusion in a syntaxin-independent manner.

Figure 8.

Location of mutated residues in Munc18-1. The position of the various mutations used in this study were highlighted in the crystal structure of Munc18-1 (blue) complexed with syntaxin1A (gray) by using Chimera software.

Which other proteins may be involved in such syntaxin-independent functions of Munc18-1? Although granuphilin is a potential candidate, none of the mutations examined affected binding of Munc18-1 to granuphilin, suggesting that alterations to this interaction do not underlie the observed phenotypes. In view of our inability to replicate Doc2 binding to Munc18-1, effects of the mutations on this interaction must formally remain a possibility. However, a search of the FlyBase and WormBase databases reveals no obvious Doc2 homologues in C. elegans or D. melanogaster, suggesting that this is an unlikely explanation for the observed synaptic effects in mutant organisms. Moreover, Doc2 proteins are not expressed in chromaffin cells (Duncan et al., 2000), and therefore the observed effects on quantal size and release kinetics in chromaffin cells cannot be mediated via effects on Doc2. One possible mechanistic explanation for the effect of P242S is the finding that it causes a reduced binding of Munc18-1 to Mint1 and Mint2. The Mint proteins have been suggested to function as adaptors that recruit Munc18-1 to specific sites of the presynaptic plasma membrane defined by neurexins (Biederer and Sudhof, 2000). As a putative Mint1/2 orthologue, dX11L, is expressed in D. melanogaster, an effect on this interaction could potentially underlie the ropG17 phenotype. It seems likely that Mints 1 and 2 do not function exclusively at the synapse, however, because Mint1 protein also is expressed in chromaffin cells (this study) and insulin-secreting cells (Zhang et al., 2004), implying a more general function in exocytosis. If this putative function involves interaction with an SM protein, however, it must be restricted to Munc18-1, because Munc18-2 and -3 do not bind to Mints (Okamoto and Sudhof, 1998). It may be speculated that Munc18-1 binding to Mints is involved in the fusion pore expansion/reclosure process. In this case, overexpression of the P242S mutant with a reduced Mint affinity may favor the formation of unstable P242S/Mint complexes, thus interfering with the function of endogenous wild-type Munc18-1 and resulting in the observed slowing of release kinetics. Alternatively, as similar effects on release kinetics also are observed in the I133V mutant that has no defect in Mint binding, it may be that the effects of both mutants on the late stages of exocytosis are instead due to altered interactions with as yet unidentified Munc18-1 binding partners.

Munc18-1 Affects the Early Stages of Dense Core Granule Recruitment Independent of Its Interaction with Syntaxin

As with the mutations discussed above, E466K had little effect on the syntaxin binding affinity of Munc18-1 in comparison with wild-type protein. This is consistent with previous studies of the analogous mutations (E467K) in Munc18-2 (Riento et al., 2000) and of the original sly1-20 mutation (E532K) in Sly1 (Grabowski and Gallwitz, 1997), where no defects were evident in binding to syntaxin 3 and Sed5, respectively. Overexpression of Munc18-1 E466K in chromaffin cells does, however, increase the rate and overall extent of exocytosis. This reveals a role for Munc18-1 in granule recruitment that is also independent of its interaction with syntaxin. Such a role fits with the reduced releasable pool size and reduced numbers of docked vesicles in synapses from C. elegans unc-18 null mutants (Weimer et al., 2003) and in immature chromaffin cells derived from Munc18-1 knockout mice (Voets et al., 2001). Furthermore, the observation that a constitutively open syntaxin mutant cannot rescue this predocking defect in unc-18 mutants (Weimer et al., 2003) strengthens the idea that this early stage of SM protein function does not require syntaxin. The E466 residue is conserved in exocytotic SM proteins (including yeast Sec1) and is located in a surface loop of domain III in both squid Sec1 and rat Munc18-1 (Bracher et al., 2000) that is distant from the region involved in syntaxin binding (Misura et al., 2000) (Figure 8). In addition, E466 lies within the sequence of a peptide that was found to inhibit neurotransmitter release when injected into the presynaptic terminal of the squid giant synapse (Dresbach et al., 1998). Coupled with this information, our findings suggest that this region of Munc18-1 is involved in interactions with other proteins during the early stages of exocytosis to maintain a controlled supply of secretory granules, analogous to a secretion “checkpoint.” The mutation from E to K may weaken or remove this point of control, allowing increased recruitment of granules to the surface membrane. Many SM proteins have already been implicated in the early events of exocytosis through genetic interactions with the genes encoding Rab-like proteins: SEC1 interacts genetically with the rab-like GTPase SEC4 (Finger and Novick, 2000), and a sec1 mutation is partially suppressed by extra copies of the SEC4 allele (Salminen and Novick, 1987). In addition, VPS45 interacts genetically with VPS21, which encodes a rab-like protein (Tall et al., 1999). Intriguingly, the sly1-20 allele (which E466K was modeled on) by-passes the requirement for the Ypt1 Rab GTPase in yeast ER-to-Golgi transport (Dascher et al., 1991; Ossig et al., 1991), suggesting that the mutation results in an altered conformation normally imposed by the Rab protein, thereby suppressing the requirement for Rab function. It is tempting to speculate that the Munc18-1 E466K mutation acts similarly to uncouple rab-dependent control of early events in vesicle recruitment. Unfortunately, pull down assays from brain extracts by using wild-type or E466K GST-Munc18-1 revealed no obvious differences in the levels of various bound proteins as detected by immunoblotting (our unpublished data). Further experiments are therefore necessary to ascertain the mechanistic basis of this effect and to determine the role of this surface loop region in domain III in Munc18-1 interactions.

Implications for SM Protein Function

The results of this study provide direct evidence that Munc18-1 performs multiple functions within a single membrane trafficking step. This may explain the apparently contradictory phenotypes exhibited by SM mutants in various organisms, because such disparate phenotypes may reflect a differential effect on either early (recruitment/docking) or late (fusion) functions. Furthermore, the demonstration here that mutations affecting both early and late stages of exocytosis do not affect syntaxin binding clearly demonstrates that interactions of Munc18-1 with other binding partners are important for at least two of its functions. The evolutionary conservation of SM proteins across phyla strongly suggests that such syntaxin-independent functions are also important for other family members. Indeed, the strikingly similar crystal structures of Munc18-1 and Sly1, despite relatively low primary sequence homology and radically different mechanisms of cognate syntaxin binding, indicates that this highly conserved tertiary structure has evolved to maintain some function(s) of SM proteins that is independent of syntaxin binding. Intriguingly, while this manuscript was under revision, it was reported that the essential in vivo function of Sly1 is unaffected by mutations that abolish the interaction between Sly1 and its cognate syntaxin Sed5 (Peng and Gallwitz, 2004). Future studies of SM proteins involved in other membrane traffic steps will be important to determine whether the syntaxin-independent functions reported recently are a general feature of SM proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The plasmid encoding GST-granuphilin A in pGEX-KG was a gift from Dr R. Regazzi (Lausanne, Switzerland). Plasmids encoding Mint 1 and Mint 2 in pCIneo were a gift from Drs. S. Groffen and D. McLoughlin (London, UK). We thank Dr. A. Boyd for discussions and comments on the manuscript. Special thanks go to Burcu Hasdemir for performing the confocal microscopy. This work was supported by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council research grant to A. M. and R.D.B.

Article published online ahead of print in MBC in Press on November 24, 2004 (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0685).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

References

- Aalto, M. K., Ronne, H., and Keranen, S. (1993). Yeast syntaxins Sso1p and Sso2p belong to a family of related membrane proteins that function in vesicular transport. EMBO J. 12, 4095-4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaad, F. F., Huet, Y., Mayer, U., and Jurgens, G. (2001). The cytokinesis gene KEULE encodes a Sec1 protein that binds the syntaxin KNOLLE. J. Cell Biol. 152, 531-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, J. W., Craig, T. J., Fisher, R. J., Ciufo, L. F., Evans, G.J.O., Morgan, A., and Burgoyne, R. D. (2003). Phosphorylation of Munc18 by protein kinase C regulates the kinetics of exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 10538-10545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederer, T., and Sudhof, T. C. (2000). Mints as adaptors. Direct binding to neurexins and recruitment of munc18. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39803-39806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher, A., Perrakis, A., Dresbach, T., Betz, H., and Weissenhorn, W. (2000). The X-ray crystal structure of neuronal Sec1 from squid sheds new light on the role of this protein in exocytosis. Structure 8, 685-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher, A., and Weissenhorn, W. (2002). Structural basis for the Golgi membrane recruitment of Sly1p by Sed5p. EMBO J. 21, 6114-6124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, S. (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, N. J., and James, D. E. (2001). Vps45p stabilizes the syntaxin homologue Tlg2p and positively regulates SNARE complex formation. EMBO J. 20, 3380-3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne, R. D., and Morgan, A. (2003). Secretory granule exocytosis. Physiol. Rev. 83, 581-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr, C. M., Grote, E., Munson, M., Hughson, F. M., and Novick, P. J. (1999). Sec1p binds to SNARE complexes and concentrates at sites of secretion. J. Cell Biol. 146, 333-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola, T., Frantz, C., Perret-Menoud, V., Gattesco, S., Hirling, H., and Regazzi, R. (2002). Pancreatic beta-cell protein granuphilin binds Rab3 and Munc-18 and controls exocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 1906-1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, T. J., Ciufo, L. F., and Morgan, A. (2004). A protein-protein binding assay using coated microtitre plates: increased throughput, reproducibility and speed compared to bead-based assays. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 60, 49-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascher, C., Ossig, R., Gallwitz, D., and Schmitt, H. D. (1991). Identification and structure of four yeast genes (SLY) that are able to suppress the functional loss of YPT1, a member of the ras superfamily. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 872-885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresbach, T., Burns, M. E., O'Conner, V., DeBello, W. M., Betz, H., and Augustine, G. J. (1998). A neuronal Sec1 homolog regulates neurotransmitter release at the squid giant synapse. J. Neurosci. 18, 2923-2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulubova, I., Sugita, S., Hill, S., Hosaka, M., Fernandez, I., Sudhof, T. C., and Rizo, J. (1999). A conformational switch in syntaxin during exocytosis: role of munc18. EMBO J. 18, 4372-4382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, R. R., Apps, D. K., Learmonth, M. P., Shipston, M. J., and Chow, R. H. (2000). Is double C2 protein (DOC2) expressed in bovine adrenal medulla? A commercial anti-DOC2 monoclonal antibody recognizes a major bovine mitochondrial antigen. Biochem. J. 351, 33-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger, F. P., and Novick, P. (2000). Synthetic interactions of the post-Golgi sec mutations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 156, 943-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R. J., Pevsner, J., and Burgoyne, R. D. (2001). Control of fusion pore dynamics during exocytosis by munc18. Science 291, 875-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, M., Kanno, E., Saegusa, C., Ogata, Y., and Kuroda, T. S. (2002). Slp4-a/granuphilin-a regulates dense-core vesicle exocytosis in PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 39673-39678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallwitz, D., and Jahn, R. (2003). The riddle of the Sec1/Munc-18 proteins - new twists added to their interactions with SNAREs. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 113-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski, R., and Gallwitz, D. (1997). High-affinity binding of the yeast cis-Golgi t-SNARE, Sed5p, to wild-type and mutant Sly1p, a modulator of transport vesicle docking. FEBS Lett. 411, 169-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, M. E., Barclay, J. W., and Burgoyne, R. D. (2004). Syntaxin/Munc18 interactions in the late events during vesicle fusion and release in exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 32751-32760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, M. E., Fisher, R. J., and Burgoyne, R. D. (2000). Measurement of exocytosis by amperometry in adrenal chromaffin cells: effects of clostridial neurotoxins and activation of protein kinase C on fusion pore kinetics. Biochimie 82, 469-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote, E., Carr, C. M., and Novick, P. J. (2000). Ordering the final events in yeast exocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 151, 439-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halachmi, N., and Lev, Z. (1996). The Sec1 family: a novel family of proteins involved in synaptic transmission and general secretion. J. Neurochem. 66, 889-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, S. D., Broadie, K., van de Goor, J., and Rubin, G. M. (1994). Mutations in the Drosophila Rop gene suggest a function in general secretion and synaptic transmission. Neuron 13, 555-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, A., Morishita, W., Hammer, R. E., Malenka, R. C., and Sudhof, T. C. (2003). A role for Mints in transmitter release: Mint 1 knockout mice exhibit impaired GABAergic synaptic transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1409-1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosono, R., Hekimi, S., Kamiya, Y., Sassa, T., Murakami, S., Nishiwaki, K., Miwa, J., Taketo, A., and Kodaira, K.-I. (1992). The unc-18 gene encodes a novel protein affecting the kinetics of acetylcholine metabolism in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurochem. 58, 1517-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, R. (2000). Sec1/Munc18 proteins: mediators of membrane fusion moving to center stage. Neuron 27, 201-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, R., and Sudhof, T. C. (1999). Membrane fusion and exocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 863-911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misura, K.M.S., Scheller, R. H., and Weis, W. I. (2000). Three-dimensional structure of the neuronal-Sec1-syntaxin1A complex. Nature 404, 355-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick, P., Field, C., and Schekman, R. W. (1980). Identification of 23 complementation groups required for post-translational events in the yeast secretory pathway. Cell 21, 205-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick, P., and Schekman, R. W. (1979). Secretion and cell-surface growth are blocked in a temperature-sensitive mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76, 1858-1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, M., and Sudhof, T. C. (1997). Mints, munc18-interacting proteins in synaptic vesicle exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 31459-31464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, M., and Sudhof, T. C. (1998). Mint 3, a ubiquitous mint isoform that does not bind to munc18-1 or -2. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 77, 161-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orita, S., Sasaki, T., Komuro, R., Sakaguchi, G., Maeda, M., Igarashi, H., and Takai, Y. (1996). Doc2 enhances Ca2+-dependent exocytosis from PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 7257-7260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossig, R., Dascher, C., Trepte, H. H., Schmitt, H. D., and Gallwitz, D. (1991). The yeast SLY gene products, suppressors of defects in the essential GTP-binding YPT1 protein, may act in endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 2980-2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, R., and Gallwitz, D. (2004). Multiple SNARE interactions of an SM protein: Sed5p/Sly1p binding is dispensable for transport. EMBO J. 23, 3939-3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pevsner, J., Shu-Chan, H., Braun, J. A., Calakos, N., Ting, T. E., Bennet, M. K., and Scheller, R. H. (1994). Specificity and regulation of a synaptic vesicle docking complex. Neuron 13, 353-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riento, K., Kauppi, M., Keranen, S., and Olkkonen, V. M. (2000). Munc18-2, a functional partner of syntaxin 3, controls apical membrane trafficking in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 13476-13483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen, A., and Novick, P. J. (1987). A ras-like protein is required for a post-Golgi event in yeast secretion. Cell 49, 527-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassa, T., Harada, S.-I., Ogawa, H., Rand, J. B., Maruyama, I. N., and Hosono, R. (1999). Regulation of the UNC-18-Caenorhabditis elegans syntaxin complex by UNC-13. J. Neurosci. 19, 4772-4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollner, T., Whiteheart, S. W., Brunner, M., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Geromanos, S., Tempst, P., and Rothman, J. E. (1993). SNAP receptors implicated in vesicle targeting and fusion. Nature 362, 318-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, A. I., et al. (2002). Large-scale analysis of the human and mouse transcriptomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 4465-4470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tall, G. G., Hama, H., DeWald, D. B., and Horazdovsky, B. F. (1999). The phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate binding protein Vac1p interacts with a Rab GTPase and a Sec1p homologue to facilitate vesicle-mediated vacuolar protein sorting. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 1873-1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhage, M., Jan de Vries, K., Røshol, H., Burbach, P. H., Gispen, W. H., and Südhof, T. C. (1997). DOC2 proteins in rat brain: complementary distribution and proposed function as vesicular adapter proteins in early stages of secretion. Neuron 18, 453-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhage, M., et al. (2000). Synaptic assembly of the brain in the absence of neurotransmitter secretion. Science 287, 864-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets, T., Toonen, R., Brian, E. C., de Wit, H., Moser, T., Rettig, J., Sudhof, T. C., Neher, E., and Verhage, M. (2001). Munc-18 promotes large dense-core vesicle docking. Neuron 31, 581-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber, T., Zemelman, B. V., McNew, J. A., Westermann, B., Gmachl, M., Parlati, F., Sollner, T. H., and Rothman, J. E. (1998). SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell 92, 759-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiland, G. A., and Molinoff, P. B. (1981). Quantitative analysis of drugreceptor interactions: I. Determination of kinetic and equilibrium properties. Life Sci. 29, 313-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimer, R. M., Richmond, J. E., Davis, W. S., Hadwiger, G., Nonet, M. L., and Jorgensen, E. M. (2003). Defects in synaptic vesicle docking in unc-18 mutants. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 1023-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M. N., Littleton, J. T., Bhat, M. A., Prokop, A., and Bellen, H. J. (1998). ROP, the Drosophila sec1 homolog, interacts with syntaxin and regulates neurotransmitter release in a dosage-dependent manner. EMBO J. 17, 127-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B., Steegmaier, M., Gonzalez, L. C., and Scheller, R. H. (2000). nSec1 binds a closed conformation of syntaxin1A. J. Cell Biol. 148, 247-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W., Lilja, L., Bark, C., Berggren, P. O., and Meister, B. (2004). Mint1, a Munc18-interacting protein, is expressed in insulin-secreting beta cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 320, 717-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.